Abstract

We previously reported that thyroid hormone stimulates renin synthesis in vivo and in vitro. Here, we analyzed the 5′-flanking sequence of the human renin gene for promoter activity responsive to thyroid hormone using Calu-6 cells, which secrete renin endogenously and express thyroid hormone receptor-β. The luciferase reporter gene was cloned together with 5′-flanking portions of the human renin gene of various lengths into the pGL3-Basic vector. Luciferase activity assays were performed using the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System. 3,3′,5-Triiodo-l-thyronine stimulated the promoter activity of pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 and pGL3-Basic−1298/+12 by 2.3±0.1- and 1.7±0.1-fold, respectively. Shorter constructs (pGL3-Basic−144/+12, pGL3-Basic−226/+12, pGL3-Basic−452/+12, and pGL3-Basic−953/+12) were not stimulated by thyroid hormone. These results suggest that there is a possible thyroid hormone response element (5′-AGG TCA GGT CAc aat GTT CCT-3′) between nucleotides −1111 and −953. In 3 constructs with site-directed mutations in this sequence, basal promoter activities were significantly increased, whereas promoter activation by thyroid hormone was abolished. Electrophoretic mobility shift assays showed that the −1111/−953 DNA fragment of the intact human renin gene was bound to nuclear proteins of Calu-6 cells; however, none of the 3 mutant probes were bound to any nuclear proteins. These results suggest that thyroid hormone stimulates the promoter activity of the human renin gene through thyroid hormone response element–dependent mechanisms in Calu-6 cells.

Keywords: human; renin; gene expression; hormones, thyroid; response elements

The renin-angiotensin system plays a pivotal role in the long-term regulation of blood pressure and electrolyte homeostasis.1 Although elevated blood pressure should suppress renin release from renal juxtaglomerular cells, high levels of plasma renin are often found in hypertensive patients.2 Increased plasma renin levels are related to the incidences of stroke, myocardial infarction, and other vascular injuries.3 Understanding the mechanism that regulates renin gene expression may provide better approaches to the treatment of hypertension.

Renin and renin mRNA are expressed in many cell types, such as in the placental, ovarian, testicular,4 adrenal,5 and pituitary6,7 cells of a number of species. The expression of renin is particularly high in juxtaglomerular cells.8 Juxtaglomerular cells are difficult to isolate and culture, and they lose their ability to produce renin after a single passage.9 Thus, because of the lack of any established renin-producing cell lines, very little is known about the mechanisms that control human renin gene expression.

Recently, Lang et al10 showed that the cell line Calu-6, derived from human lung cancer, endogenously produces human renin and renin mRNA. Successive studies have demonstrated that renin synthesis in Calu-6 cells, like juxtaglomerular cells, is activated by cAMP11 and inhibited by mechanical stretch.12 Therefore, the Calu-6 cell line is a potentially useful model for studying transcriptional regulation of the human renin gene.

We recently reported that thyroid hormone directly stimulates renin mRNA in vivo13 and in vitro.14 In the present study, we examined 2 hypotheses: (1) that thyroid hormone increases renin mRNA in Calu-6 cells and (2) that thyroid hormone stimulates the promoter activity of the human renin gene in Calu-6 cells.

Methods

Cell Cultures

The Calu-6 cell line was obtained from American Type Culture Collection. Cells were grown in minimum essential medium with Earle's salt (GIBCO BRL) supplemented with nonessential amino acids (GIBCO BRL), sodium pyruvate (GIBCO BRL), and 10% fetal bovine serum (GIBCO BRL) as according to the supplier's protocol. Cells were incubated at 37°C in 95% air-5% CO2 to 90% confluence. The cells were passaged; 48 hours later, they were inspected for attachment to the culture dishes. The culture medium was changed, and Calu-6 cells were treated with or without 10−7 mol/L 3,3′,5-triiodo-l-thyronine (T3; Aldrich) for 24 hours, because this concentration and incubation time induced the maximum stimulation of renin synthesis in a preliminary study.

Expression of Human Thyroid Hormone Receptor-β

Calu-6 cells were rinsed 3 times with PBS, collected by scraping, resuspended in 500 μL guanidine isothiocyanate, and homogenized with a Polytron homogenizer (Kinematica) for 30 seconds at 4°C. Total RNA from cultured Calu-6 cells was extracted using a total RNA extraction kit (Clontech) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

RT-PCR was performed with the GeneAmp RNA PCR core kit (Perkin–Elmer Cetus). Sense (5′-GAG GAG AAG AAA TGT AAA GG-3′) and antisense (5′-TGT TGC CAT GCC AAC ATA GAT GC-3′) primers for PCR amplification of human thyroid hormone receptor-β (hTR-β) cDNA corresponded to hTR-β gene nucleotides +250 through +269 and +491 through +513, respectively.15 PCR was performed for 30 cycles with a 30-second denaturation step at 94°C, a 60-second annealing step at 50°C, and a 75-second extension step at 72°C. The PCR product was sequenced to confirm that it was hTR-β cDNA through dideoxy sequencing with the ABI PRISM cycle sequencing kit (Perkin–Elmer Cetus). The sequences obtained were identical to those previously reported.15

Expression Analysis

Total RNA from cultured Calu-6 cells was extracted as described earlier. Quantitative RT-PCR was performed precisely as previously described.16-18 Sense (5′-AAT GAA GGG GGT GTC TGT GG-3′) and antisense (5′-CAC GAC ATA ATC AAA CAG CC-3′) primers for PCR amplification of human renin cDNA corresponded to human renin gene nucleotides +812 through +831 and +952 through +971, respectively.19 Sense (5′-CGG ATT TGG TCG TAT TGG GC-3′) and antisense (5′-AAA TGA GCC CCA GCC TTC TCC-3′) primers for PCR amplification of human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate-dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA corresponded to human GAPDH gene nucleotides +87 through +106 and +375 through +395, respectively.20 PCR was performed for 30 cycles with a 30-second denaturation step at 94°C, a 60-second annealing step at 57°C, and a 75-second extension step at 72°C. After coamplification of total RNA with each sense and antisense primer, gel electrophoresis exhibited 2 clear bands at 160 and 309 bp that represent the human renin and GAPDH genes, respectively. GAPDH mRNA was used as an internal standard, because thyroid hormone treatment did not alter the quantity of this mRNA in Calu-6 cells. Human renin mRNA expression was determined as the ratio of the human renin to GAPDH band density. The PCR products were sequenced to confirm that they were human renin and human GAPDH cDNA with the ABI PRISM cycle sequencing kit. The sequences obtained were identical to those previously reported.19,20

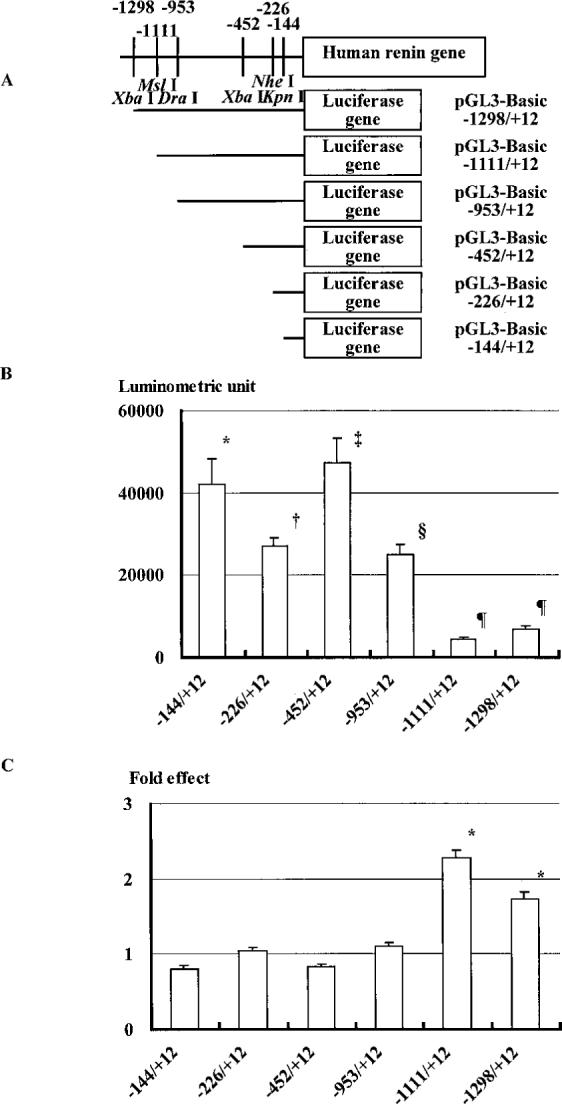

Constructs

Human genomic DNA was isolated with a GenTLE kit (Takara) from peripheral blood of a healthy volunteer. With this genomic DNA used as a template, overlapping 5′-flanking intervals of the human renin gene were isolated by PCR with an LA PCR kit version 2 (Takara). Sense (5′-GCC AAG CAT TCA TTA ACC C-3′) and antisense (5′-GCT GAT CGT AAG GAC TGA ATG AC-3′) primers for PCR amplification of human renin 5′-flanking area corresponded to human renin gene nucleotides −2754 through −2736 (relative to the start site of human gene transcription) and +226 through +248, respectively.19 Each PCR cycle consisted of a 30-second denaturation step at 94°C, a 60-second annealing step at 54°C, and a 75-second extension step at 72°C, for a total of 30 cycles. The PCR product was cloned into the pT7Blue(R) T-Vector (Novagen) to generate the construct pT7Blue(R)+248/−2754. Fusions between the 5′-flanking overlapping intervals and the luciferase reporter gene were made with the pGL3-Basic vector (Promega). The plasmids pGL3-Basic−1298/+12, pGL3-Basic−1111/+12, pGL3-Basic−953/+12, pGL3-Basic−452/+12, pGL3-Basic−226/+12, and pGL3-Basic−144/+12 have a common 3′ end at +12 and promoters of varying lengths and were cloned as shown in Figure 1A. Sequences of all constructs were confirmed through dideoxy sequencing with an ABI PRISM cycle sequencing kit.

Figure 1.

A, Restriction enzyme sites in 5′-flanking region of the human renin gene and schema of the construction of luciferase reporter plasmid. B, Effect of various construct lengths on the promoter activity of the human renin gene. Values are presented as mean±SEM. *P<0.02 vs pGL3-Basic (1155±219 luminometric units). †P<0.05 vs pGL3-Basic−144/+12. ‡P<0.04 vs pGL3-Basic−226/+12. §P<0.02 vs pGL3-Basic−452/+12. ¶P<0.02 vs pGL3-Basic−953/+12. n=6. C, Effect of thyroid hormone on the promoter activity of the human renin gene. Data are expressed as fold change in comparison to that without T3. Values shown are mean±SEM. *P<0.01 between with and without T3. n=6.

Transfection Studies

Plasmid DNAs were purified with a commercial kit (Qiagen). Transient DNA transfection was performed with Tfx-20 Reagent (Promega). The culture medium was replaced with serum-free medium shortly before the transfection. Each luciferase reporter plasmid (0.5 μg) was cotransfected with 0.5 μg of the pRL-TK vector (Promega). When needed, T3 (10−7 mol/L) was added immediately. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the cells were lysed by the addition of 100 μL passive lysis buffer (Promega). Luciferase activity assays were performed with the Dual Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega) and were read in a TD-20/20 automatic luminometer (Turner Designs). The pRL-TK luciferase activity was used to correct for transfection efficiency, sample loss, and other factors that could affect the results. Experiments in which pRL-TK luciferase activity varied by >2-fold were discarded. Consequently, when luciferase activities of pRL-TK were evaluated as the transfection efficiency, the efficiency varied within 1.9-fold (maximum 59 840, minimum 32 070, and average 45 694±1915 luminometric units). In a preliminary study, we examined the relation between transfection time and luciferase activity by using pGL-Basic−144/+12 without T3. When cells were harvested 12 hours after transfection, luciferase activity was 25 008±1124 luminometric units (n=6). Luciferase activity significantly increased at 24 and 36 hours (47 308±3121 and 42 206±3065 luminometric units, respectively) and then notably decreased at 48 hours to 26 990±1039 luminometric units. Therefore, as noted above, we harvested cells 24 hours after transfection in the following protocols.

Mutant Study

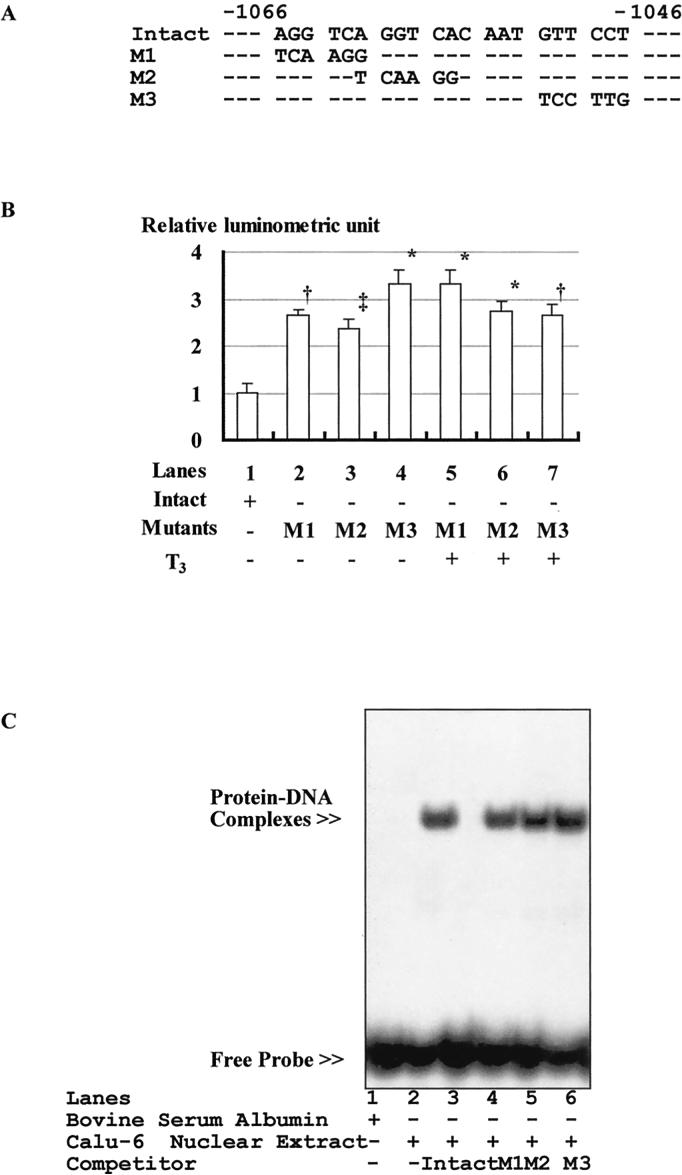

Domain mutants were generated from pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 plasmid with a QuickChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Mutants-1, -2, and -3 (M1, M2, and M3) were changed from 5′-AGG TCA-3′ (−1066 to −1061) to 5′-TCA AGG-3′, from 5′-AGG TCA-3′ (−1061 to −1056) to 5′-TCA AGG-3′, and from 5′-GTT CCT-3′ (−1051 to −1046) to 5′-TCC TTG-3′, respectively (Figure 2A). The transfection study was performed as described earlier.

Figure 2.

A, Schema of 3 mutants of the human renin gene. B, Effects of mutations in the putative THRE motifs. Data are expressed as the ratio to the average luminometric units of pGL3-Basic−1111/+12. Values are presented as mean±SEM. *P<0.0001, †P<0.01, ‡P<0.03 vs pGL3-Basic−1111/+12. n=6. C, Electrophoretic mobility shift assay of the radioactive labeled −1111/−953 DNA fragment of the intact human renin gene with bovine serum albumin (lane 1) or the nuclear extract from Calu-6 cells (lanes 2 to 6). No slow migrating band was observed when the labeled DNA was incubated with bovine serum albumin (lane 1); however, a single specific band appeared with retarded mobility when the labeled DNA was incubated with nuclear extract from Calu-6 cells (lane 2). Furthermore, the binding of labeled putative THRE to the nuclear proteins was displaced by the excessive unlabeled DNA fragment of the intact human renin gene (lane 3) but not by the excessive unlabeled DNA fragments of the 3 mutants of the human renin gene (lanes 4 to 6). Similar observations were obtained from 2 other experiments.

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assays

Nuclear extracts were prepared from 108 confluent Calu-6 cells according to the Hennighausen method.21 The −1111/−953 DNA fragment of the intact human renin gene was 5′-end labeled with γ-32P-ATP (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech) with T4 polynucleotide kinase (Takara). Ten micrograms of nuclear protein from Calu-6 cells or bovine serum albumin was incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature in the presence of 0.3 U of poly(dI/dC) in 20 mmol/L Tris-glycine (pH 7.6) and 1 mmol/L EDTA. The 5′-labeled probe (0.1 pmol) was added, and the preparation was further incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature. After chilling on ice, the mixture was run on an 8% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel and exposed for autoradiography. In competition assays, a 200-fold excess of unlabeled −1111/−953 DNA fragment of the intact human renin gene or the 3 human renin gene mutants was added to the reaction mixture and incubated for 30 minutes at room temperature before incubation with the labeled probe.

RNase Protection Assays

The levels of hTR-β, renin, and GAPDH mRNA were also measured by RNase protection of specific oligonucleotide probes using the Multi-NPA Kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer's protocol. For hTR-β mRNA detection, a 53-mer oligonucleotide antisense to the hTR-β mRNA with 10 nucleotides mismatched at its 3′-end was used. The sequence of this oligomer is 5′-CGT GAT ACA GCG GTA GTG ATA CCC GGT GGC TTT GTC ACC ACA Ctc tgt gta gt-3′, complementary to nucleotides +312 through +354 of the hTR-β gene.15 To detect renin mRNA, a 51-mer oligonucleotide complementary to the human renin mRNA with 9 nucleotides mismatched at its 3′-ends was used. The sequence of this oligomer (5′-GGA GCT GGT AGA ACC TGA GAT GTA GGA TGC ACC GGT GTC TAC gtg gca ttg-3′) is complementary to nucleotides +873 through +914 of the human renin gene.19 The lowercase letters of both oligomers represent the mismatched bases. The levels of human GAPDH mRNA were measured in these studies with a commercially available 44-mer (Ambion) that gives a 36-mer nuclease-protected fragment. These probes were 5′-end labeled as described earlier. The radiolabeled probe (300 pg ≈ 4×104 cpm) was hybridized to 10 μg of sample total RNA and subjected to nuclease treatment. The nuclease-protected oligomers were analyzed by 15% polyacrylamide, 7 mol/L urea gel (Novex) electrophoresis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with an unpaired t test or 1-way ANOVA with the post hoc Schéffe F test. All data are presented as mean±SEM. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

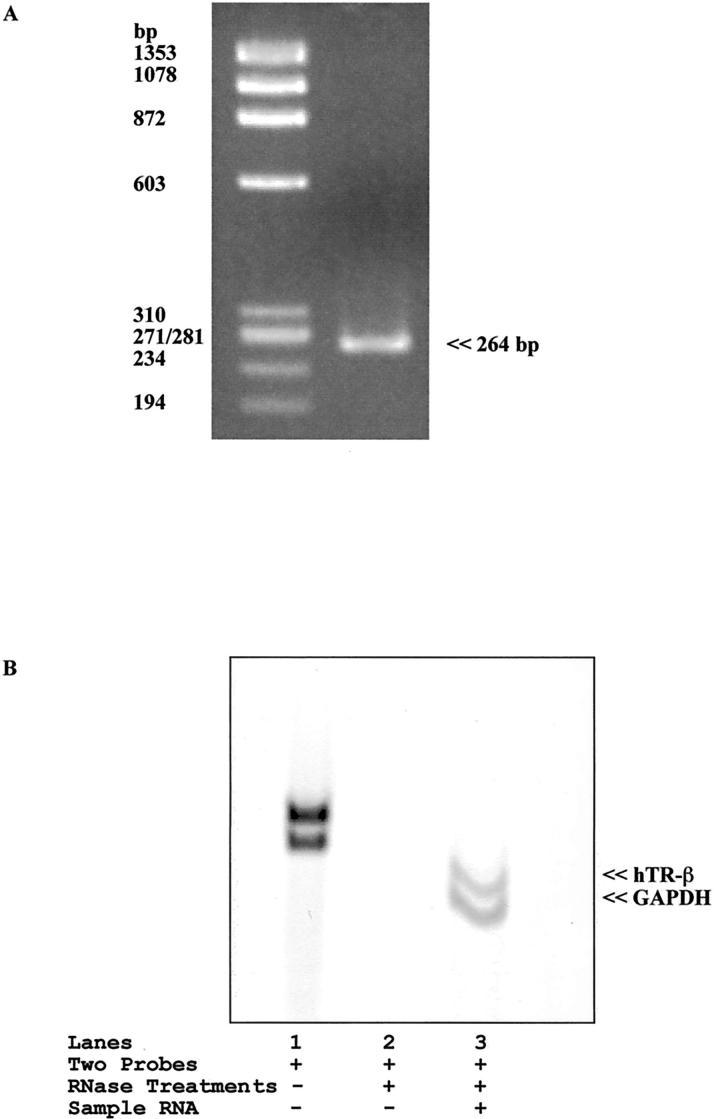

After RT-PCR with total RNA from Calu-6 cells with hTR-β–specific primers, gel electrophoresis exhibited 1 clear band at 264 bp that represents the hTR-β gene (Figure 3A) and confirmed the expression of hTR-β in Calu-6 cells. The expression of hTR-β was also confirmed with RNase protection assay (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

A, Determination of hTR-β expression in Calu-6 cells by RT-PCR. The PCR product was sequenced and confirmed to be identical to hTR-β cDNA. B, The expression of hTR-β in Calu-6 cells was also confirmed with RNase protection assay. When sample RNA and RNase treatments were omitted, 2 bands for full-length probes were shown (lane 1). When sample RNA was excluded, no band was seen, because RNase treatment digested both probes (lane 2). When RNase protection assay was performed with 2 kinds of probe and sample RNA including RNase treatments, 2 shorter fragments that were protected from RNase treatment were confirmed (lane 3).

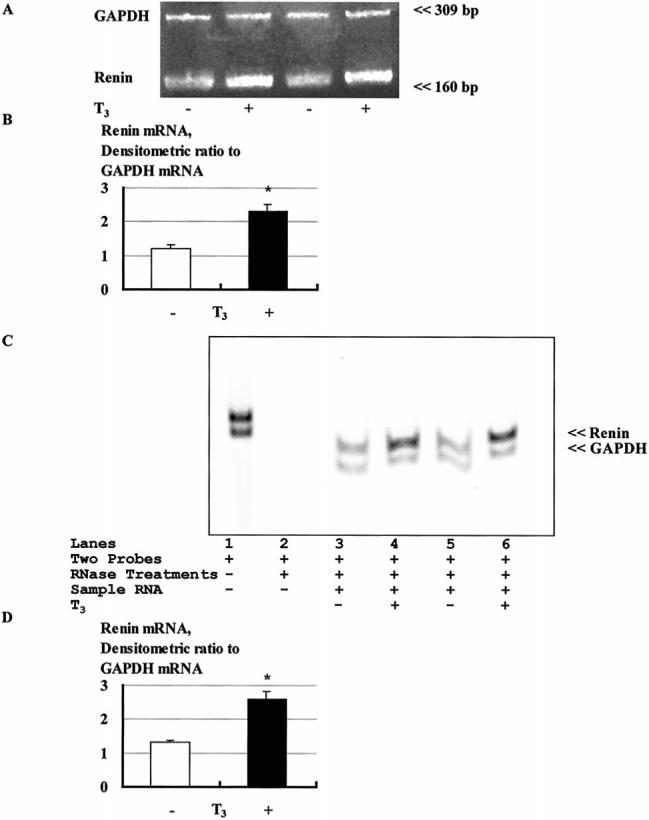

The effect of thyroid hormone on the expression of renin mRNA is depicted in Figure 4A. According to quantitative RT-PCR, thyroid hormone significantly increased human renin mRNA levels by 92% (2.30±0.20 versus 1.20±0.10, densitometric ratio to GAPDH, Figure 4B). The enhancement of the expression of the human renin gene by thyroid hormone treatment was also confirmed with RNase protection assay (Figure 4C). Densitometric analysis showed that thyroid hormone significantly increased human renin mRNA levels by 98% (2.58±0.21 versus 1.30±0.02, densitometric ratio to GAPDH, Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Effect of thyroid hormone on renin mRNA expression. A, Representative blots of renin and GAPDH mRNA levels in Calu-6 cells by RT-PCR. The PCR products were sequenced and were confirmed to be human renin and human GAPDH cDNA. B, Densitometric analysis of the bands shows that thyroid hormone increases renin mRNA expression by 92%. C, Representative blots of renin and GAPDH mRNA levels in Calu-6 cells by RNase protection assay. When RNase protection assay was performed with 2 kinds of probe and sample RNA including RNase treatments, 2 shorter fragments that were protected from RNase treatment were confirmed (lanes 3 to 6). D, Densitometric analysis of the bands shows that thyroid hormone increases renin mRNA expression by 98%. Values shown are mean6SEM. *P<0.01 vs without T3. n=12.

The effect of varying lengths of the 5′-flanking sequence on the promoter activity of the human renin gene is shown in Figure 1B. Under basal conditions, pGL3-Basic−144/+12 showed more reporter activity than the parent pGL3-Basic plasmid (1155±219 luminometric units). Less reporter activity was observed from extracts of cells transfected with pGL3-Basic−266/+12 than from those transfected with pGL3-Basic−144/+12. pGL3-Basic−452/+12 showed more activity than pGL3-Basic−226/+12. pGL3-Basic−953/+12 demonstrated less activity than pGL3-Basic−452/+12. pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 and pGL3-Basic−1298/+12 exhibited less activity than pGL3-Basic−953/+12.

The effect of thyroid hormone on the promoter activity of the human renin gene is shown in Figure 1C. In comparison with basal activity, thyroid hormone stimulated the promoter activity of pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 and pGL3-Basic−1298/+12 by 2.3±0.1- and 1.7±0.1-fold, respectively. Other shorter constructs did not exhibit stimulation by thyroid hormone.

The effects of mutations in the putative thyroid hormone (THRE) motifs are shown in Figure 2B. Basal promoter activities were significantly increased in M1, M2, and M3 compared with pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 (lanes 2 to 4), whereas thyroid hormone did not stimulate promoter activities in mutated constructs (lanes 5 to 7).

The interaction of the putative human renin gene THRE with the nuclear proteins of Calu-6 cells was examined with electrophoretic mobility shift assay. Figure 2C shows the binding of Calu-6 cell nuclear extract with the labeled putative THRE. A single specific band appeared with retarded mobility (lane 2). No specific band was observed when the labeled DNA was incubated with bovine serum albumin alone (lane 1). Furthermore, the binding of labeled putative THRE to the nuclear proteins was displaced by the excessive unlabeled DNA fragment of the intact human renin gene (lane 3). The excessive unlabeled DNA fragments of the 3 mutants of the human renin gene did not show any obvious changes in electrophoretic mobility (lanes 4 to 6).

Discussion

Expression of renin mRNA in Calu-6 cells was increased by thyroid hormone in the same manner as in primary cultured juxtaglomerular cells, suggesting that Calu-6 cells may provide a good model to study the effect of thyroid hormone on transcriptional changes in the renin gene. The 5′-flanking DNA sequence −144/+12 appears to contain the human renin gene promoter. The same region (−149/+13,10 −148/+11,22 and −148/+18,23 and −137/+1624 ) was also identified as the human renin gene promoter using Calu-6, GC rat lactotrope precursor, and JEG-3 human choriocarcinoma cell lines. These consistent findings among different cell lines support the notion that this 150- to 160-nucleotide stretch in the 5′ area of the human renin gene does contain the promoter.

Our results also suggested that the 5′-flanking DNA sequences, −226/−144, −953/−452, and −1111/−953, contain a negative regulatory element (Figure 1B), which is consistent with the findings of Lang et al ,10 Sun et al,22,23 and Borensztein et al.24 The 5′-flanking DNA sequence −452/−226 appears to contain a positive regulatory element (Figure 1B), which is also consistent with the findings of Sun et al.22 However, pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 and pGL3-Basic−1298/+12 repressed promoter activity (Figure 1B).

The sequences −1111/+12 and −1298/+12 had significantly increased promoter activity with thyroid hormone treatment; constructs with sequences −144/+12, −226/+12, −452/+12, and −953/+12 did not show any significant changes. These stimulatory effects of T3 on luciferase activity with constructs pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 and −1298/+12 suggest that hTR-β bound to THRE and activated basal promoter activity in the presence of thyroid hormone. Because the shorter construct did not show any response to T3, the sequence between −1111 and −953 may contain a THRE.

We found 3 candidate THRE motifs (5′-AGG TCA-3′) in sequence −1111/−953: (1) 5′-AGG TCA-3′ (−1066 to −1061), (2) 5′-AGG TCA-3′ (−1061 to −1056), and (3) 5′-GTT CCT-3′ (−1051 to −1046). The most common motifs of THRE are an inverted palindrome without spaces (AGG TCA TGA CCT)25 and a direct repeat with 4 spaces (AGG TCA (n)4 AGG TCA).26 However, other patterns have been recently reported to be THREs.27,28 When variation in the THRE motif is taken into account, it is possible that the perfect direct repeat without space (5′-AGG TCA GGT CA-3′, −1066 to −1056) and the nearly perfect inverted palindrome spaced by 4 bp (5′-AGG TCA caa tGT TCC T-3′, −1061 to −1046) are putative THREs.

Nucleotides 5′-AGG TCA GGT CAc aat GTT CCT-3′ (−1066 to −1046) inhibited renin gene promoter activity. It has been reported that hTR-β constitutively binds to THRE and represses basal promoter activity in the absence of thyroid hormone. It is possible that hTR-β could not bind the mutated THRE motif sequences in the present study and therefore could not repress basal promoter activity. In addition, the stimulatory effect of thyroid hormone was abolished by each mutation, indicating that thyroid hormone and hTR-β cannot form a complex on the mutated THRE.

The electrophoretic mobility shift assay data (Figure 2C) further confirmed that the intact putative THRE is important for binding with Calu-6 cell nuclear extract and that all 3 putative motifs are essential for the interaction of the putative THRE of the human renin gene with Calu-6 cell nuclear proteins. This result is consistent with the luciferase assay studies shown in Figure 2B. In Figure 2B, each mutated construct lost all thyroid hormone responsiveness, whereas each construct had intact 2 putative motifs. It is, however, still not clear why the remaining 2 motifs in each mutant DNA fragment of the human renin gene, M1, M2, and M3, did not compete with intact DNA probe. It is possible that the binding ability of DNA with 3 intact motifs is so potent that the remaining 2 motifs in mutated DNA cannot replace the binding between wild-type DNA and the nuclear proteins. Previous reports showed that 3 motifs worked as 1 THRE in the α-myosin heavy chain,29 growth hormone,30 and malic enzyme31 genes. Sugawara et al32 examined the role of 3 THRE motifs in the growth hormone gene and, consistent with our present data, found that the interaction of THRE and hTR-β was lost when 1 of 3 putative motifs was mutated, suggesting that all 3 half-sites are necessary.

In conclusion, we present the following findings. (1) Thyroid hormone stimulated renin mRNA expression in Calu-6 cells. (2) Thyroid hormone stimulated the promoter activity of the pGL3-Basic−1111/+12 and the pGL3-Basic−1298/+12 by 2.3±0.1- and 1.7±0.1-fold over basal levels, respectively; however, other shorter constructs (pGL3-Basic−144/+12, pGL3-Basic−226/+12, pGL3-Basic−452/+12, and pGL3-Basic−953/+12) were not stimulated by thyroid hormone. (3) In sequence −1111/−953, there is a 5′-AGG TCA GGT CAc aat GTT CCT-3′ sequence that may be a THRE. Mutant studies indicated that hTR-β could not repress the basal promoter activity in the absence of thyroid hormone. (4) The intact motif of the putative THRE is important for binding to Calu-6 cell nuclear proteins. These results suggest that thyroid hormone stimulates the promoter activity of the human renin gene through a THRE-dependent mechanism in Calu-6 cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the Japanese Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture; Grant-in-Aid for Encouragement of Young Scientists 08770511 (1996) and 09770500 (1997−1998); a Young Investigator Prize for Encouragement from Keio University (1996 and 1998); a grant-in-aid from Keio University for the Promotion of Science (1997); research fellowships of the Yokoyama Clinical Pharmacology Foundation (1998); and the Uehara Memorial Foundation (1999).

Footnotes

Presented in part in abstract form at the 31st Annual Meeting of the American Society of Nephrology (J Am Soc Nephrol. 1998;9:309A), the 53rd Annual Fall Conference and Scientific Sessions of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research (Hypertension. 1999;34:364), and the 32nd Annual Meeting of the American Society of Nephrology (J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:348A).

References

- 1.Sealey JE, Laragh JH. The renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system for normal regulation of blood pressure and sodium and potassium homeostasis. In: Laragh JH, Brenner BM, editors. Hypertension: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis and Management. Raven Press; New York, NY: 1990. pp. 1287–1317. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sealey JE, Quimby FW, Itskoviz J, Rbattu S. The ovarian renin-angiotensin system. Front Neuroendocrinol. 1990;11:213–237. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alderman MH, Madhavan S, Ooi WL, Cohen H, Sealey JE, Laragh JH. Association of the renin-sodium profile with the risk of myocardial infarction in patients with hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1991;324:1098–1104. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104183241605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sealey JE, Glorioso N, Itskovitz J, Laragh JH. Prorenin as a reproductive hormone: new form of the renin system. Am J Med. 1986;81:1041–1046. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(86)90402-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sigmund CD, Gross KW. Structure, expression, and regulation of the murine renin genes. Hypertension. 1991;18:446–457. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.18.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naruse K, Takii Y, Iagami T. Immunohistochemical localization of renin in luteinizing hormone-producing cells of rat pituitary. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:7579–7583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deschepper CF, Mellon SH, Cumin F, Baxter JD, Ganong WF. Analysis by immunocytochemistry and in situ hybridization of renin and its mRNA in kidney, testis, adrenal, and pituitary of the rat. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:7552–7556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.19.7552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hackenthal E, Paul M, Ganten D, Tugner R. Morphology, physiology, and molecular biology of renin secretion. Physiol Rev. 1990;70:1067–1116. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galen FX, Devaux C, Houot AM, Menard J, Corvol P, Corvol MT, Gubler MC, Mounier F, Camilleri JP. Renin biosynthesis by human tumoral juxtaglomerular cells: evidence for a renin precursor. J Clin Invest. 1984;73:1144–1155. doi: 10.1172/JCI111300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lang JA, Ying LH, Morris BJ, Sigmund CD. Transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms regulate human renin gene expression in Calu-6 cells. Am J Physiol. 1996;271:F94–F100. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1996.271.1.F94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ying L, Morris BJ, Sigmund CD. Transactivation of the human renin promoter by the cyclic AMP/protein kinase A pathway is mediated by both cAMP-responsive element binding protein-1 (CREB)-dependent and CREB-independent mechanisms in Calu-6 cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:2412–2420. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carey RM, McGrath HE, Pentz ES, Gomez RA, Barrett PQ. Biomechanical coupling in renin-releasing cells. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1566–1574. doi: 10.1172/JCI119680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobori H, Ichihara A, Suzuki H, Miyashita Y, Hayashi M, Sruta T. Thyroid hormone stimulates renin synthesis in rats without involving the sympathetic nervous system. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:E227–E232. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.272.2.E227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ichihara A, Kobori H, Miyashita Y, Hayashi M, Sruta T. Differential effects of thyroid hormone on renin secretion, content, and mRNA in juxtaglomerular cells. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E224–E231. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.2.e224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinberger C, Thompson CC, Ong ES, Lebo R, Gruol DJ, Evans RM. The c-erb-A gene encodes a thyroid hormone receptor. Nature. 1986;324:641–646. doi: 10.1038/324641a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kobori H, Ichihara A, Suzuki H, Takenaka T, Miyashita Y, Hayashi M, Sruta T. Role of the renin-angiotensin system in cardiac hypertrophy induced in rats by hyperthyroidism. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:H593–H599. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.273.2.H593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kobori H, Ichihara A, Miyashita Y, Hayashi M, Sruta T. Mechanism of hyperthyroidism-induced renal hypertrophy in rats. J Endocrinol. 1998;159:9–14. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1590009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobori H, Ichihara A, Miyashita Y, Hayashi M, Sruta T. Local renin-angiotensin system contributes to hyperthyroidism-induced cardiac hypertrophy. J Endocrinol. 1999;160:43–47. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1600043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardman JA, Hort YJ, Catanzaro DF, Tellam JT, Baxter JD, Morris BJ, Sine J. Primary structure of the human renin gene. DNA. 1984;3:457–468. doi: 10.1089/dna.1.1984.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ercolani L, Florence B, Denaro M, Aexander M. Isolation and complete sequence of a functional human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:15335–15341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hennighausen L, Lbon H. Interaction of protein with DNA in vitro. Methods Enzymol. 1987;4:429–435. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)52076-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sun J, Oddoux C, Lazarus A, Gilbert MT, Catanzaro DF. Promoter activity of human renin 5′-flanking DNA sequences is activated by the pituitary-specific transcription factor Pit-1. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1505–1508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun J, Oddoux C, Gilbert MT, Yan Y, Lazarus A, Campbell WG, Jr, Catanzaro DF. Pituitary-specific transcription factor (Pit-1) binding site in the human renin gene 5′-flanking DNA stimulates promoter activity in placental cell primary cultures and pituitary lactosomatotropic cell lines. Circ Res. 1994;75:624–629. doi: 10.1161/01.res.75.4.624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borensztein P, Germain S, Fuchs S, Philippe J, Corvol P, Pnet F. cis-Regulatory elements and trans-acting factors directing basal and cAMP-stimulated human renin gene expression in chorionic cells. Circ Res. 1994;74:764–773. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.5.764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glass CK, Holloway JM, Devary OV, Rosenfeld MG. The thyroid hormone receptor binds with opposite transcriptional effects to a common sequence motif in thyroid hormone and estrogen response elements. Cell. 1988;54:313–323. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90194-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Umesono K, Murakami KK, Thompson CC, Evans RM. Direct repeats as selective response elements for the thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, and vitamin D3 receptors. Cell. 1991;65:1255–1266. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90020-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xiong S, Chirala SS, Hsu MH, Wakil SJ. Identification of thyroid hormone response elements in the human fatty acid synthase promoter. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:12260–12265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.21.12260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang CY, Kim S, Harney JW, Larsen PR. Further characterization of thyroid hormone response elements in the human type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase gene. Endocrinology. 1998;139:1156–1163. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.3.5849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Izumo S, Mhdavi V. Thyroid hormone receptor alpha isoforms generated by alternative splicing differentially activate myosin HC gene transcription. Nature. 1988;334:539–542. doi: 10.1038/334539a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Norman MF, Lavin TN, Baxter JD, West BL. The rat growth hormone gene contains multiple thyroid response elements. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:12063–12073. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Petty KJ, Desvergne B, Mitsuhashi T, Nikodem VM. Identification of a thyroid hormone response element in the malic enzyme gene. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:7395–7400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sugawara A, Yen PM, Chin WW. 9-cis Retinoic acid regulation of rat growth hormone gene expression: potential roles of multiple nuclear hormone receptors. Endocrinology. 1994;135:1956–1962. doi: 10.1210/endo.135.5.7956917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]