Abstract

We have previously reported an important role of increased tyrosine phosphorylation activity by Src in the modulation of hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated (HCN) channels. Here we provide evidence showing a novel mechanism of decreased tyrosine phosphorylation on HCN channel properties. We found that the receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase-α (RPTPα) significantly inhibited or eliminated HCN2 channel expression in HEK293 cells. Biochemical evidence showed that the surface expression of HCN2 was remarkably reduced by RPTPα, which was in parallel to the decreased tyrosine phosphorylation of the channel protein. Confocal imaging confirmed that the membrane surface distribution of the HCN2 channel was inhibited by RPTPα. Moreover, we detected the presence of RPTPα proteins in cardiac ventricles with expression levels changed during development. Inhibition of tyrosine phosphatase activity by phenylarsine oxide or sodium orthovanadate shifted ventricular hyperpolarization-activated current (If, generated by HCN channels) activation from nonphysiological voltages into physiological voltages associated with accelerated activation kinetics. In conclusion, we showed a critical role RPTPα plays in HCN channel function via tyrosine dephosphorylation. These findings are also important to neurons where HCN and RPTPα are richly expressed.

Activated by membrane hyperpolarization, the HCN22 channels are important to rhythmic activity in neurons and myocytes (1, 2). Accumulating evidence has also suggested an important role of tyrosine phosphorylation in modulating HCN channels (3, 4). We have recently shown that increased tyrosine phosphorylation state of HCN4 by activated Src tyrosine kinase can enhance the gating of HCN4 channels (5). Given that the efficacy of tyrosine phosphorylation is determined by the dynamic balance of tyrosine kinases and tyrosine phosphatases, reduced tyrosine phosphatase activity is speculated to increase HCN channel activity. Receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatases (RPTPs) are transmembrane phosphatases critical in cell growth and cell adhesion (6). One member of RPTPs, RPTPα, has been proposed to be a positive regulator of Src tyrosine kinases (7, 8). As a protein-tyrosine phosphatase, RPTPα should also be able to dephosphorylate phosphotyrosines of channel proteins. This work was designed to investigate whether RPTPα can inhibit the HCN channel activity by decreasing the tyrosine phosphorylation state of HCN channel proteins.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Plasmids—Mouse HCN2 cDNA in an oocyte expression vector, pGH, was initially obtained from Drs. Bina Santoro/Steve Siegelbaum (Columbia University). We subcloned it into the EcoRI/XbaI sites of pcDNA3.1 mammalian expression vector (Invitrogen) for functional expression in mammalian cells. Mouse HCN2 with hemagglutinin (HA) tag containing sequence 284GISAYGITYPYDVPDYAI285 inserted in the extracellular loop between S3 and S4 was obtained from Dr. Michael Sanguinetti (University of Utah) (9). We subcloned it into the HindIII/XbaI sites of pcDNA3.1 vector for surface expression study. RPRPα inserted in pRK5 vector was kindly provided by Dr. Jan Sap (University of Copenhagen, Denmark). Src529 was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology, Inc./Millipore.

Cell Culture and Plasmid Transfections—HEK293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 100 g/liter streptomycin. Cells with 50–70% confluence in 6-well plate were used for HCN2, Src529, and RPTPα plasmid transfections using Lipofectamine2000 (Invitrogen).

Cell Lysis, Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blot Analysis—Total protein extracts were prepared from transfected cells after 24–48 h of incubation with CytoBuster protein extraction reagent kit (Novagen) that contains 0.1% SDS. For membrane fraction preparations (e.g. HCN2 Western blotting analysis in Fig. 3), we used a membrane protein extraction kit (Pierce). The protein concentration of the lysate was determined using the Bradford or BCA assay. Equal amounts of total protein (0.5–1 mg) were incubated with a specific antibody for 1 h at 4 °C, and protein A/G PLUS-agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was then added and incubated overnight with gentle rocking. The beads were washed extensively with cold PBS buffer and resuspended in 2× sample buffer. The immune complexes were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blot using the specific antibody of interest. Total protein of 5–20 μg per sample was subjected to SDS-PAGE using 4–12% gradient gels (Invitrogen), then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences), and incubated with proper antibodies (e.g. HCN2 from Alomone; α-actin and β-actin from Abcam). After washing and incubating with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody, immunoreactive proteins were visualized with the SuperSignal® West Pico kit (Pierce). All protein experiments were repeated at least three times, if not mentioned in the text. Quantification of immunoblots was performed using ImageQuant software (version 5.1, GE Healthcare).

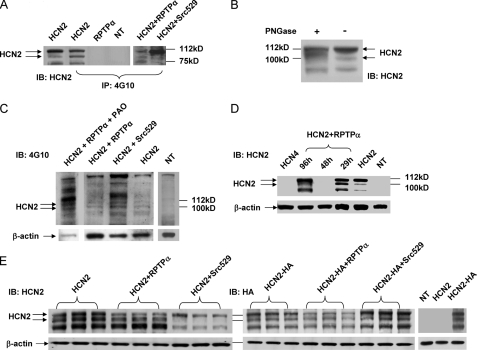

FIGURE 3.

RPTPα induced tyrosine dephosphorylation and surface expression of HCN2 channels. A, HEK293 cells were nontransfected (NT), transfected with either HCN2 or RPTPα alone. Membrane fractions of the samples were immunoprecipitated (IP) using 4G10 followed by HCN2 signal detection using an anti-HCN2 antibody. The 1st left lane shows HCN2 immunoblots (IB). HCN2 was also co-transfected with Src529 and RPTPα, respectively, for comparison of tyrosine phosphorylation levels. B, Western blotting analysis for deglycosylation of HCN2 channel by PNGase. HCN2 signals were detected using the HCN2 antibody for PNGase-treated and untreated samples. C, 4G10 immunoblots in HEK293 cells transfected with HCN2, HCN2+Src529, HCN2+RPTPα, and HCN2+RPTPα-treated with PAO for 40 min, respectively. A separate blot in nontransfected sample served as a negative control. Actin signals were used as loading controls. D, time-dependent inhibition of HCN2 channel surface expression by RPTPα as follows: immunoblots of HCN2 alone, co-transfected with RPTPα for 29, 48, and 96 h, respectively. NT indicates a nontransfected sample serving as a negative control. The HCN4-transfected sample was also used for another control. E, immunoblots of HCN2 (left panel) or HCN2-HA (right panel) in HEK293 cells transfected with HCN2 (or HCN2-HA) alone, co-transfected with RPTPα or Src529. An anti-HCN2 antibody (left panel) or an anti-HA tag antibody (upper panel) was used. Nontransfected (NT) and nontagged HCN2 transfected cells were used as negative controls for HA antibody.

De-glycosylation was carried out by following the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, the membrane protein fraction sample was denatured in 0.5% SDS and 40 mm dithiothreitol at 100 °C for 10 min and transferred to a solution composed of 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, and 1% Nonidet P-40. Peptide: N-glycosidase F (PNGase, New England Biolabs, 500–1000 units for up to 20 μg of glycoprotein) was then added, and the reaction was incubated for 3 h at 37°C. Samples were then cleaned and concentrated using the PAGEprep™ protein clean up kit (Pierce).

Surface expression detection was carried out by using a HCN2-HA plasmid. An anti-HA tag antibody (Millipore) that recognizes YPYDVPDYA was used in Western blotting analysis of HCN2 surface expression in HEK293 cells.

Confocal Fluorescent Imaging of HEK293 Cells—HEK293 cells transfected with HCN2-EGFP or HCN2-HA were incubated on coverslips, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 15 min, and then washed with PBS (10 mm phosphate buffer, 150 mm NaCl, pH 7.4) for 5 min three times, followed by blocking in 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS, pH 7.4, for 60 min. For immunofluorescence confocal imaging of HCN2-HA, cells were then incubated with an anti-HA tag (fluorescein isothiocyanate) antibody (2 μg/ml, Abcam) in 1% bovine serum albumin/PBS, pH 7.4, for 60 min. After washing six times in PBS, coverslips were mounted on slide glasses using Fluoromount G (Southern Biotechnology). Cells were imaged by LSM510 confocal microscopy using a Plan-Neofluar 40×/0.75 objective or a Plan-Apochromat 63×/1.4 Oil DIC M27 objective. Excitation wavelength and filters for EGFP and fluorescein isothiocyanate are 488 nm and argon laser/emission BP505–530 nm.

Cardiac Tissue and Myocyte Preparation—Adult rats (300–350 g) were euthanized by intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols. The heart was excised, and ventricles were cut out and prepared for protein chemistry experiments. The ventricular myocytes were prepared using a collagenase dissociation protocol as described previously (5, 10). Briefly, the aorta was cannulated, and the heart was retrogradely perfused with oxygenated Ca2+-free Tyrode solution at 37 °C for 5 min, followed by oxygenated Ca2+-free Tyrode solution containing 0.6 mg/ml collagenase II (Worthington) for 20–30 min. The ventricles were minced into small pieces in KB solution, dispersed, and filtrated through a 200-μm mesh. The isolated myocytes were stored in KB solution at room temperature for 1 h before patch clamp experiments.

Whole-cell Patch Clamp Recordings of HCN2 Currents and If—For recording IHCN2, day 1 (24–30 h) up to day 4 (90–98 h) post-transfection, HEK293 cells with green fluorescence were selected for patch clamp studies. The HEK293 cells were placed in a Lucite bath in which the temperature was maintained at 25 ± 1 °C by a temperature controller (Cell MicroControls, Virginia Beach, VA). For recording If, the freshly isolated adult rat ventricular myocytes were placed in a Lucite bath in which the temperature was maintained at 35 ± 1 °C by a temperature controller (Cell MicroControls).

IHCN2 currents were recorded using the whole-cell patch clamp technique with an Axopatch-200B amplifier. The pipettes had a resistance of 2–4 megohms when filled with internal solution (mm) as follows: NaCl 6, potassium aspartate 130, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 5, EGTA 11, and HEPES 10; pH adjusted to 7.2 by KOH. The external solution contained (mm) the following: NaCl 120, MgCl2 1, HEPES 5, KCl 30, CaCl2 1.8, and pH was adjusted to 7.4 by NaOH. The Ito blocker, 4-aminopyridine (2 mm), was added to the external solution to inhibit the endogenous transient potassium current, which can overlap with and obscure IHCN2 tail currents recorded at 20 mV. Data were acquired by CLAMPEX and analyzed by CLAMPFIT (pClamp 8, Axon Instruments).

If currents were recorded using the whole-cell patch clamp technique with an Axopatch-700B amplifier. The external solution contained (mm) the following: NaCl 140, KCl 5.4, CaCl2 1.8, MgCl2 1, and glucose 10, NiCl2 0.1, BaCl2, 5, 4-aminopyridine 2, tetrodotoxin 0.03, pH 7.4. The pipettes had a resistance of 2–4 megohms when filled with internal solution composed of (mm) the following: NaCl 6, potassium aspartate 130, MgCl2 2, CaCl2 1, Na2-ATP 2, Na-GTP 0.1, HEPES 10, pH 7.2. Sodium (INa) and potassium (Ito) current blockers, tetrodotoxin and 4-aminopyridine, were added to the external solution to inhibit the sodium and transient potassium currents. During If recording, BaCl2 was added to the external solution to block IK1 background potassium current, which can mask If current.

Data are shown as mean ± S.E. The threshold activation of If is defined as the first hyperpolarizing voltage at which the time-dependent inward current can be observed. Student's t test was used for statistical analysis with p < 0.05 being considered as statistically significant. Time constants were obtained by using Boltzmann best fit with one exponential function on current traces that reach steady state (e.g. in the presence of phenylarsine oxide) or on current trace that can be fit to steady state (e.g. in the absence of phenylarsine oxide, at -150 mV).

RESULTS

RPTPα Inhibition of HCN2 Currents in HEK293 Cells—Our recent discovery showed that increased tyrosine phosphorylation of HCN4 channel by activated Src tyrosine kinase can enhance the channel gating properties in HEK293 cells (5, 11). We wondered whether increased tyrosine dephosphorylation by RPTPα may inhibit the gating properties of HCN channels expressed in HEK293 cells.

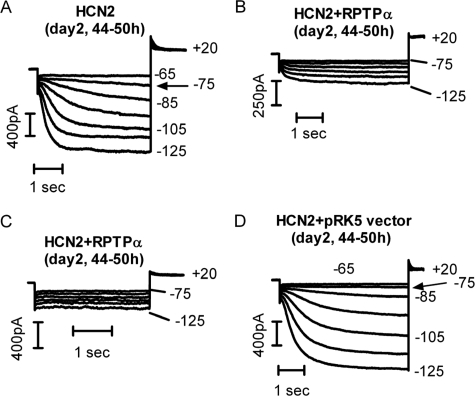

Functional expressions of HCN2 after 2 days (44–50 h) of transfection are shown in Fig. 1. HCN2 currents were elicited by hyperpolarizing pulses detailed in the figure legends. Typical biophysical properties of the expressed channels such as the threshold activation, activation kinetics, and current densities are comparable with those reported previously (5, 11, 12). Co-transfection with RPTPα, however, resulted in a dramatic inhibition (Fig. 1B) or a surprising loss of HCN2 currents (Fig. 1C). Similar results were reproduced in 10 additional cells for each HCN2 channel co-expressed with RPTPα. As part of control experiments, the empty pRK5 vector did not affect HCN2 expression from 1 to 4 days post-transfection. Fig. 1D shows the HCN2 recordings in a HEK293 cell co-transfected with HCN2 and pRK5 vector after 2 days. Similar results were obtained in an additional five cells.

FIGURE 1.

RPTPα inhibition of HCN2 current expression. HCN2 currents were recorded 2 days after cell transfection. A, HCN2 currents in a HEK293 cell expressing HCN2 alone. Hyperpolarizing pulses (4 s) from -65 to -125 mV were applied. B, hyperpolarization-activated currents in a HEK293 cell co-transfected with HCN2 and RPTPα. Hyperpolarizing pulses (5 s) from -75 to -125 mV were applied. C, hyperpolarization-activated currents in a HEK293 cell co-transfected with HCN2 and RPTPα. Hyperpolarizing pulses (3 s) from -75 to -125 mV were applied. D, HCN2 currents in a HEK293 cell co-transfected with HCN2 and the empty pRK5 vector. Hyperpolarizing pulses (5 s) from -65 to -125 mV were applied. The tail currents were recorded at +20 mV. The holding potential was -10 mV. Arrows in A and D indicate the threshold activation of HCN2 currents.

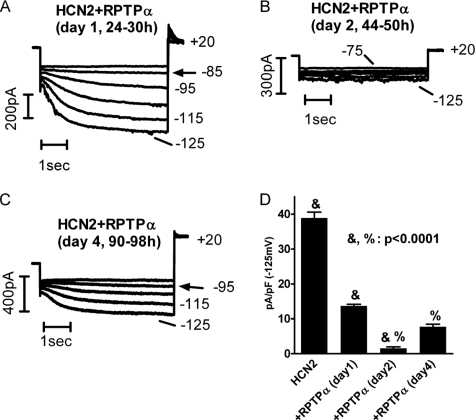

Interestingly, we found the degree by which RPTPα inhibited HCN2 current expression changed with time. Fig. 2 shows HCN2 current expression recorded in HEK293 cells co-transfected with RPTPα after 1 day (24–30 h) (A), 2 days (44–50 h) (B), and 4 days (C) post-transfection. Compared with HCN2 alone (Fig. 1A), co-transfection with RPTPα reduced HCN2 current density (pA/pF) measured at -125 mV by 64% after day 1 (HCN2 = 38.9 ± 1.7, n = 11; RPTPα = 1.37 ± 0.5, n = 10), by 96% after day 2 (RPTPα = 1.5 ± 0.5, n = 10), and by 80% after day 4 (RPTPα = 7.7 ± 0.7, n = 10) (Fig. 2D). The time-dependent inhibition is not only significant as compared with the control, but also significant among groups (e.g. day 1 and day 2; day 2 and day 4). To understand the cellular mechanisms that mediate the dramatic inhibition of RPTPα on HCN2 channel function, we carried out protein biochemical studies on HCN2 channels.

FIGURE 2.

RPTPα induced time-dependent inhibition of HCN2 current expression. Hyperpolarizing pulses of 5 s ranging from -75 to -125 mV (A and B) or from 85 to -125 mV (C) in 10-mV increments were applied to elicit HCN2 currents in HEK293 cells co-transfected HCN2 with RPTPα after day 1 (A), day 2 (B), and day 4 (C). D, averaged HCN2 current density at -125 mV for the corresponding time periods.

RPTPα Dephosphorylation of HCN2 Channels—We have previously shown that increased tyrosine phosphorylation of HCN4 channels by a constitutively active form of Src, Src529, increased channel conductance near diastolic potentials associated with accelerated activation kinetics (5, 11). Inhibition of HCN2 current expression by RPTPα led us to examine whether the tyrosine phosphorylation state of HCN2 channels might be decreased by RPTPα.

In HEK293 cells transfected with HCN2, 29 h after transfection the cell lysates were first immunoprecipitated by a phosphotyrosine-specific antibody, 4G10, followed by detection of HCN2 signals using an anti-HCN2 antibody. Fig. 3A shows that HCN2 channels were tyrosine-phosphorylated (2nd left lane). Immunoblot of HCN2 in Fig. 3A, 1st left lane, served as a positive control. The nontransfected cells and cells transfected with RPTPα alone were used as negative controls. The band close to 112 kDa is the glycosylated (mature) form expressing on the membrane surface, and the band near 100 kDa is the unglycosylated (immature) form that is not expressed on the membrane surface (13). We also confirmed the glycosylated signal by using PNGase, which can remove the N-glycosylation of HCN2 (Fig. 3B). In comparison with the untreated sample, PNGase treatment significantly decreased the upper band (N-glycosylated signal) and increased the lower band (un-N-glycosylated signal). The ratio of glycosylated over unglycosylated signals is decreased in the PNGase-treated sample. Nature of the third band is unknown. Tyrosine phosphorylation levels of HCN2 are much lower in cells co-expressing HCN2 and RPTPα than in cells co-transfected with HCN2 and Src529 (right panel of Fig. 3A). It is noted that the glycosylated HCN2 signal was significantly enhanced by Src529, whereas the unglycosylated signal was barely detectable.

To seek direct evidence for RPTPα-induced dephosphorylation on HCN2 channel, we examined immunoblots using 4G10 in cells expressing HCN2 alone, with Src529, with RPTPα, and with RPTPα in the presence of 1 μm phenylarsine oxide (PAO) (a nonspecific tyrosine phosphatase inhibitor) for 40 min, respectively. Shown in Fig. 3C, location of predicated HCN2 signal is marked by arrows. Background tyrosine phosphorylation of HCN2 is low but noticeable, which was significantly increased by Src529 and decreased by RPTPα, respectively. However, inhibited tyrosine phosphorylation of HCN2 by RPTPα can be reversed by treating cells with PAO. Signals were normalized to β-actins. In comparison with HCN2, Src529 increased HCN2 phosphorylation by about 4-fold (3.7 ± 0.8, n = 3), whereas RPTPα decreased it by more than 2-fold (2.2 ± 0.6, n = 4). Compared with HCN2 + RPTPα (Fig. 3C, 2nd left lane), cells treated with PAO (1st left lane) increased HCN2 phosphorylation by about 18-fold (17.7 ± 1.5, n = 3). Nontransfected cells were used as a negative control (1st right lane of Fig. 2C). Combined with 4G10 immunoprecipitation results in Fig. 3A, these results strongly suggest that RPTPα can dephosphorylate HCN2 channel proteins expressed in HEK293 cells.

RPTPα Inhibition of HCN2 Cell Surface Expression—To seek additional evidence for contribution of RPTPα-induced tyrosine dephosphorylation to the inhibition of HCN2 surface expression, we first utilized the time-dependent phosphatase activity of RPTPα. It was reported using SF9 cells that RPTPα activity changed with time as follows: significantly increased after 24 h, reached maximum after 48 h, and declined at 96 h (14). Although no reports have shown similar time-dependent changes in RPTPα activity in HEK293 cells, we observed a time-dependent inhibition of HCN2 currents by RPTPα (Fig. 2) that implied a possible time-dependent RPTPα activity in HEK293. We examined HCN2 expression co-transfected with RPTPα after day 1 (29 h), day 2 (48 h), and day 4 (96 h), respectively (Fig. 3D). Compared with HCN2 alone, which served as a positive control, HCN2 co-transfected with RPTPα for 29 h began to increase the unglycosylated signal. HCN2 signals were barely detected after 48 h of transfection but readily detected after 96 h of transfection. Cells with nontransfection served as a negative control. Cells transfected with HCN4 were used as additional control for HCN2 antibody specificity. Similar results were obtained from an additional three experiments. These results provided a biochemical explanation for RPTPα-induced time-dependent inhibition of HCN2 currents (Fig. 2), which favored a mechanism that tyrosine dephosphorylation may be involved in retaining HCN2 in the cytoplasm by RPTPα in a time-dependent manner.

We then compared the effects of RPTPα on surface expression of either the HCN2 or the HA-tagged HCN2 channel proteins. As shown in Fig. 3E, after 24–30 h of transfection HCN2 (left panel) or HCN2-HA (right panel) channels expressed alone in HEK293 cells gave rise to three bands (one near 112 kDa, one near 100 kDa, and the nature of the third band unknown). Co-transfection of Src529 significantly increased the glycosylated form of HCN2 or HCN2-HA, whereas co-transfection with RPTPα decreased the glycosylated form of HCN2 or HCN2-HA. The specificity of the HA antibody was tested in nontransfected and nontagged HCN2-transfected cells (rightmost panel of Fig. 3E). β-Actins were used as loading controls. Taken together, these data strongly supported the notion that the surface expression of the HCN2 channel is associated with HCN2 channel tyrosine phosphorylation levels.

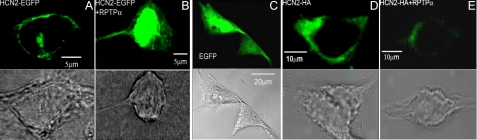

RPTPα Inhibition of Surface Fluorescence of HCN2 Channels—We next employed confocal laser scanning microscopy to study the surface expression of a HCN2-EGFP fusion protein and an HCN2-HA construct in HEK293 cells. As shown in Fig. 4A, HCN2 channels were normally expressed mostly on the membrane surface and some in the cytoplasm. Co-transfection with RPTPα retained most of the HCN2 in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4B). The empty EGFP vector, which served as a negative control, was expressed homogeneously in the cell (Fig. 4C). In addition, we used an anti-HA tag antibody to study the immunofluorescent imaging of the HCN2-HA channels. After 2 days (44–50 h) of transfection in HEK293 cells, HCN2 channels can be readily detected on the plasma membrane (Fig. 4D). Under the identical optical settings, co-transfection of HCN2-HA with RPTPα dramatically reduced the fluorescent signals (Fig. 4E). Similar results were obtained in the additional 8–10 cells for each experiment. Comparing the results of HCN2-EGFP with those of HCN2-HA clearly showed retention of HCN2 by RPTPα in the cytoplasm, which is consistent with the biochemical evidence shown in Fig. 3.

FIGURE 4.

Confocal images of HCN2 surface expression in HEK293 cells. Fluorescent images of the HCN2-EGFP fusion protein are shown in the absence (A) and presence (B) of RPTPα. Immunofluorescent images of the HCN2-HA channels are shown in the absence (D) and presence (E) of RPTPα. EGFP vector is shown in C. Bright field images provided shapes of cells where the transverse scanning imaging was performed (A–E).

RPTPα Expression and Interaction with HCN2 Channels in Cardiac Myocytes—RPTPα has been previously detected at mRNA levels in whole heart preparation (14), but its protein expression in heart has not been reported. To extend our findings to a relatively physiological context, we examined the protein expression of RPTPα in adult rat ventricles. As shown in Fig. 5A, RPTPα protein signals were indeed detected in adult rat ventricles by Western blot analysis using an anti-RPTPα antibody. A mouse version of RPTPα expressed in HEK293 cells was used as a positive size control which showed both a weak band at 100 kDa (p100) and a strong band at 130 kDa (p130). Both p100 and p130 bands are glycosylated forms of RPTPα (15). To increase the sensitivity, we immunoprecipitated the samples followed by Western blot using the same antibody. Using this method, the p130 band was also detected (middle lane in Fig. 5C) but at much lower levels compared with p100 in adult rat ventricles. The 66-kDa (p66) band in Fig. 5C is the truncated form of RPTPα that contains the phosphatase catalytic domains (16). It loses phosphatase activity after truncation. The nontransfected sample was used as a negative control. β-Actin and cardiac α-actin were used as loading controls for HEK293 cells and cardiac tissues, respectively. Six additional repeats of the same experiment confirmed the protein expression of RPTPα in cardiac ventricles.

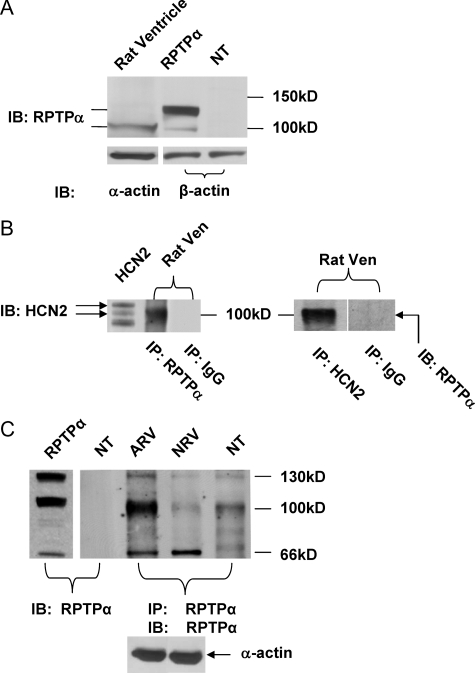

FIGURE 5.

RPTPα expression in rat ventricles. A, RPTPα protein detection in adult rat ventricles using an anti-RPTPα antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). HEK293 cells transfected with mouse RPTPα (RPTPα) or nontransfected (NT) were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. IB, immunoblot. Actins (α-actin in cardiac tissues and β-actin in HEK293 cells) were used as loading controls. B, co-immunoprecipitation of RPTPα with HCN2 in adult rat ventricle. Left panel, the adult rat ventricular (Ven) samples were immunoprecipitated (IP) using an RPTPα antibody followed by HCN2 signal detection using an HCN2 antibody. Immunoblot of HCN2 expressed in HEK293 cells served as a positive control. Right panel, the adult rat ventricular samples immunoprecipitated using an HCN2 antibody followed by RPTPα signal detection using an RPTPα antibody. Sample immunoprecipitated with IgG followed by RPTPα signal detection was used as a negative control. C, samples from adult (43 days) and neonatal (1 day) rat ventricles (ARV and NRV, respectively) were immunoprecipitated and detected for RPTPα using the same RPTPα antibody. HEK293 cells with nontransfection (NT) were used as negative controls. HEK293 cells transfected with RPTPα alone was adult and neonatal rat ventricles.

The fact that HCN2 and HCN4 are the only two HCN isoforms present in cardiac ventricles with HCN2 being the prevalent one (17) and that RPTPα can dephosphorylate HCN2 channels in HEK293 cells led us to hypothesize that RPTPα may associate with HCN2 in cardiac ventricles. Using co-immunoprecipitation assay, Fig. 5B showed that HCN2 signals can be detected with an HCN2 antibody in the cell lysates immunoprecipitated using an RPTPα antibody (left panel of Fig. 5B). Immunoblot of HCN2 in HEK293 cells was used as a positive control. It needs to be pointed out that in the figure the HCN2 signals in HEK293 cells represents the glycosylated (112kD) and un-glycosylated (100 kDa) forms, whereas the strong band near 100 kDa in rat ventricle after RPTPα immunoprecipitation is the unglycosylated HCN2 (the glycosylated HCN2 signal was too weak to be detected). This is consistent with the inhibition of HCN2 surface expression by RPTPα. Sample immunoprecipitated with IgG served as a negative control. On the other hand, the band of RPTPα can be detected with an RPTPα antibody in the sample immunoprecipitated using an HCN2 antibody (right panel of Fig. 5B). All experiments were repeated at least three times. These data collectively suggested that RPTPα is indeed present and can interact with HCN2 channels in adult rat ventricles.

Altered RPTPα Expression during Development—Our early studies showed that the voltage-dependent activation of If is shifted to more negative potentials during development (10, 18). Given the suppression of HCN channel expression by RPTPα, we hypothesized that RPTPα protein expression may be lower in newborn than in adult rat ventricles. Fig. 5C demonstrated that although the major form of RPTPα (p100) can be readily detected in adult ventricles, it is barely detectable in neonatal (day 1) rat ventricles. p100 RPTPα protein levels were 7.3 ± 0.8 (n = 3) times higher in adult than in neonatal ventricles. Levels of p130 RPTPα were also higher, whereas the expression levels of p66 RPTPα were lower (but insignificantly) in adult ventricles (0.8 ± 0.3, n = 3). The total RPTPα protein expression was higher in adult than in neonatal ventricles (3.9 ± 0.6, n = 3). HEK293 cells without transfection were used as a negative control, and cells were transfected with RPTPα as a positive control. Using immunoprecipitation of the sample and Western blotting with the same RPTPα antibody, we showed that the endogenous RPTPα exists in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5C, rightmost lane), which cannot be visualized by immunoblot without prior immunoprecipitation (2nd left lane). Similar results were obtained in three additional experiments.

Reduced Tyrosine Phosphatase Activity Increased If Activity in Adult Rat Ventricular Myocytes—To seek physiological implication on the inhibition of HCN channel function by increased tyrosine phosphorylation activity, we studied the pacemaker current in adult rat ventricular myocytes. The pacemaker current, If, is a time- and voltage-dependent inward current, which is an important contributor to cardiac pacemaker activity in response to β-adrenergic and muscarinic acetylcholine receptor stimulation (19). In normal conditions, If activates at nonphysiological voltages (10, 20, 21). In response to enhanced tyrosine kinase activity, If activation in rat ventricle was shifted to depolarizing voltages associated with accelerated activation kinetics (4). Given that RPTPα expression is high in adult ventricular myocytes and phenylarsine oxide can inhibit RPTPα-induced tyrosine dephosphorylation (Fig. 3C), applying phenylarsine oxide was hypothesized to increase If activity in adult ventricular myocytes.

Fig. 6A shows a typical If recording from an adult rat ventricular myocyte. Holding the membrane at -50 mV, hyperpolarizing pulses for 4.5 s were applied from -70 to -150 mV in 10-mV increments and stepped further to -150 mV for recording tail currents (pulse protocol shown in Fig. 6D). In another myocyte incubated with 1 μm PAO for 10–15 min, the same pulse protocol was applied. The threshold activation of If in the absence of phenylarsine oxide was around -120 mV in this myocyte (arrow in Fig. 6A), similar to our previous results (4, 10, 18). The threshold activation of If in the presence of PAO, however, was surprisingly shifted to a much more depolarized potential around -80 mV (arrow in Fig. 6B). Averaging over six myocytes, the threshold activation of If in the presence of PAO was -78 ± 7 mV and -113 ± 4 mV in the absence of PAO (p < 0.01). This is a nearly 40-mV positive shift of If threshold activation in response to the acute effect of reduced tyrosine phosphatase activity.

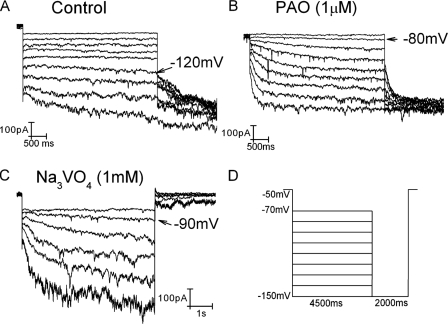

FIGURE 6.

Reduced tyrosine phosphatase activity on If in adult rat ventricular myocytes. If was recorded in adult rat ventricular myocytes in the absence (A) and presence of 1 μm phenylarsine oxide (B) and 1 mm sodium orthovanadate (C). The pulse protocol used for A and B was shown in D. C, If was elicited by 6-s hyperpolarizing pulses ranging from -80 to -135 mV in 10-mV increments. The holding potential was -50 mV. Arrows indicate the threshold activation of If.

Because of extremely negative activation of If in adult ventricular myocytes, the same pulse protocol was able to make If to the steady states in the presence, but not in the absence, of PAO, indicating that PAO can induce much faster If activation. At -150 mV (at which Boltzmann best fit with one exponential function could be readily performed on the current trace in the absence of PAO), activation kinetics were 2123 ± 607 ms in the absence of PAO (n = 6) and 741 ± 192 ms in the presence of PAO (n = 7) (p < 0.05). These results are in agreement with the increased If channel activities induced by increasing tyrosine kinase activity in our previous studies (4).

To verify that the enhanced If activity (depolarized threshold activation associated with faster activation kinetics) by PAO was indeed because of the reduced tyrosine phosphatase activity, we used another inhibitor, sodium orthovanadate, which is structurally different from PAO. Shown in Fig. 6C, in myocytes incubated with 1 mm sodium orthovanadate for 30–40 min, If was elicited by 6 s of hyperpolarizing pulses from -80 to -130 mV in 10-mV increments. The threshold activation of If was -90 mV in this myocyte (arrow in Fig. 6C). The averaged If threshold activation was -93 ± 6 mV(n = 3), which is significantly shifted to more positive potentials as compared with control (p < 0.05). These data are consistent with those obtained from PAO-treated myocytes.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we provided evidence showing dramatic inhibitory effects of tyrosine dephosphorylation by RPTPα on HCN2 channels. Two mechanisms are likely involved as follows: tyrosine dephosphorylation and membrane trafficking of HCN channels. Both are mediated by RPTPα.

In HEK293 cells co-expressing HCN2 channels with RPTPα for 2 days yielded surprising inhibition or even elimination of the current expression. There are two plausible explanations as follows: the channels were retained in the cytoplasm leading to little or no expression of functional channels on plasma membrane, or gating properties of the channels on the plasma membrane were inhibited. We performed Western blot analysis on the membrane fraction of cells and revealed two known HCN2 signals. One around 100 kDa is the unmodified form with the predicted molecular weight, and the other near 112 kDa is the glycosylated form of HCN2. The constitutively active Src, which increases the tyrosine phosphorylation level of the channels, increased the surface expression of the channels. On the other hand, RPTPα, which decreases the tyrosine phosphorylation level of the channels, retained most channels in the cytoplasm. This is also evidenced by the association of HCN2 with RPTPα in which stronger unglycosylated HCN2 bands were detected in samples immunoprecipitated by RPTPα antibody (Fig. 5B).

It is surprising that the HCN2 channel expression was largely blocked by RPTPα after 2 days of transfection and reappeared after 4 days of transfection (Fig. 2B and Fig. 3D). It offers a likely explanation to no measurable or much smaller time-dependent inward currents in HEK293 cells co-transfected by HCN2 with RPTPα for the same time periods (Fig. 1, B and C). It is worth noting that whole-cell patch clamp technique applied to individual cells is more sensitive than Western blotting, which obtains the average result from batch of cells. Therefore, after transfection for 2 days we were able to detect small current expression in some cells, but not in protein expression.

Protein-tyrosine phosphatases, like protein-tyrosine kinases, play a critical role in the regulation of physiological events (7, 8). RPTPα has a short extracellular domain (about 123–150 amino acids long) that contains eight potential N-glycosylation sites (15, 22). Following a transmembrane region, there are two tandem domains having phosphatase catalytic activity. RPTPα is expressed in two isoforms differing by nine residues (22) that are highly glycosylated, p100 and p130 on SDS-PAGE (15). The p100 form contains only N-linked glycosylation, whereas p130 contains both N-linked and O-linked glycosylation (15). Both forms have the similar enzymatic activities (15).

We found that RPTPα expression is cell-specific. In HEK293 cells, a strong signal at 130 kDa is detected, which is the predominant signal that has been frequently observed in previous studies (15). In adult rat ventricles, however, we found that the prevalent form of RPTPα is p100 (a precursor of p130 (15)). We also detected a p66 form of RPTPα in cardiac ventricles after increasing the blotting sensitivity by immunoprecipitating the samples followed by signal detection using the same antibody (Fig. 5C). Previous study reported that p66 is the N-terminal region truncated form of RPTPα that is catalyzed by calpain (a calcium-dependent proteolytic enzyme) and loses the phosphatase enzymatic activity (16). It may not be coincident that calpain-1 expression levels in heart are decreased during development (23), which leaves more active isoforms (100 and 130 kDa) of RPTPα in adult ventricle. The physiological relevance of p66 RPTPα is currently unknown.

To investigate the physiological implications of RPTPα suppression on HCN2 channels with regard to modulation of cardiac pacemaker activity, we examined the levels of RPTPα protein expression in neonatal (which exhibit spontaneous pacemaker activity) and adult rat ventricles (which do not have spontaneous pacemaker activity under physiological conditions). We found higher RPTPα levels in adult than in neonatal ventricles, which is in parallel to the physiological activation of neonatal ventricular If and nonphysiological activation of adult ventricular If.

Ample evidence has already recognized a close association between the voltage-dependent activation of If and the pacemaker activities in different heart regions (3, 19–21, 24). The threshold activation of If is tissue-specific across the heart regions as follows: from around -50 mV in the sinoatrial node to -110/-120 mV in ventricles (3, 18, 20, 21). Voltage-dependent activation of If also changes with development and pathologic conditions. In neonatal rat ventricles, If activates around -70 mV and shifts to more negative potentials beyond the physiological voltage range in adult ventricle (-113 mV) (18). Hypertrophied or failing heart increases If current density and shifts its activation to physiological voltages (25, 26). The enhanced If under pathological conditions has been implicated in atrial and ventricular arrhythmias (25, 26). It is currently unknown how developmental and pathological conditions cause the shift of If voltage-dependent activation.

PAO is a phosphotyrosine phosphatase inhibitor that cross-links vicinal

thiol (-SH/-OH and -SH/-CO2H) groups, thereby inactivating

phosphatases possessing X-Cys-X-X-Cys-X motifs, and

it does not affect tyrosine kinases

(27). On the other hand, the

vanadate ( ) ion binds irreversibly

to the active sites of tyrosine phosphatases, likely acting as a phosphate

analogue (28). Therefore,

Na3VO4 is a competitive inhibitor. In adult rat

ventricular myocytes perfused with either phenylarsine oxide for 10–15

min or sodium vanadate for 30–40 min, we recorded an

If within physiological voltages associated with faster

activation kinetics, which is comparable with neonatal ventricular

If. Because PAO and Na3VO4 inhibit

tyrosine phosphatase activity by different mechanisms, the significantly

enhanced If activity favored a reduced tyrosine

phosphatase activity. Both inhibitors, however, are not selective to

RPTPα, and we cannot exclude the potential contribution of tyrosine

phosphatases other than RPTPα to the altered If.

Because the effects occurred less than an hour, increased membrane trafficking

of HCN channels may not be the main mechanism. Rather, the enhanced HCN2

channel activity because of increased tyrosine phosphorylation is the

favorable underlying mechanism.

) ion binds irreversibly

to the active sites of tyrosine phosphatases, likely acting as a phosphate

analogue (28). Therefore,

Na3VO4 is a competitive inhibitor. In adult rat

ventricular myocytes perfused with either phenylarsine oxide for 10–15

min or sodium vanadate for 30–40 min, we recorded an

If within physiological voltages associated with faster

activation kinetics, which is comparable with neonatal ventricular

If. Because PAO and Na3VO4 inhibit

tyrosine phosphatase activity by different mechanisms, the significantly

enhanced If activity favored a reduced tyrosine

phosphatase activity. Both inhibitors, however, are not selective to

RPTPα, and we cannot exclude the potential contribution of tyrosine

phosphatases other than RPTPα to the altered If.

Because the effects occurred less than an hour, increased membrane trafficking

of HCN channels may not be the main mechanism. Rather, the enhanced HCN2

channel activity because of increased tyrosine phosphorylation is the

favorable underlying mechanism.

Our data have shown a critical role that RPTPα plays in the tyrosine dephosphorylation of HCN2 channels. The short-term effect (10–40 min), which likely involves the tyrosine dephosphorylation, is the reduced If activity in cardiac myocytes. Since the discovery of If in adult mammalian ventricular myocytes 15 years ago (20), it is the first time that we are able to shift the ventricular If activation from nonphysiological voltages to physiological potentials by acutely inhibiting the endogenous tyrosine phosphatase activity.

The long-term effects (days) include the inhibition of HCN channel surface expression and possibly channel biosynthesis. Recently, HCN4 mutants have been linked to the bradycardia and long-QT arrhythmias (29–32). The common cellular mechanism was retaining membrane trafficking caused by the truncated HCN4 protein lacking cyclic nucleotide binding domain (31), D553N in the C-linker between S6 and cyclic nucleotide binding domain (32), and G480R in the channel pore region (29). The evidence we presented in this work provided a novel mechanism that may be used to enhance the surface expression of mutant HCN channels for effecting normal cardiac pacemaker activity.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Dr. Jan Sap (University of Copenhagen, Denmark) who generously provided the human and mouse RPTPα plasmids, RPTPα antibody, and for reading the manuscript with insightful comments. We are grateful for plasmids as the generous gifts from Drs. Bina Santoro (HCN2-EGFP) and Michael Sanguinetti (HCN2-HA). We thank Jing He for excellent technical assistance. We also thank Dr. Karen Martin for technical help with confocal laser scanning imaging.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant HL075023 (NHLBI). This work was also supported by the Office of Research and Graduate Programs/HSC at West Virginia University (to H. G. Y.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: HCN, hyperpolarization-activated cyclic nucleotide-gated; RPTPα, receptor-like protein-tyrosine phosphatase-α; EGFP, enhanced green fluorescent protein; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; HA, hemagglutinin; PNGase, peptide:N-glycosidase; PAO, phenylarsine oxide.

References

- 1.Santoro, B., and Baram, T. Z. (2003) Trends Neurosci. 26 550-554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Robinson, R. B., and Siegelbaum, S. A. (2003) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 65 453-480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu, J. Y., Yu, H., and Cohen, I. S. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1463 15-19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu, H. G., Lu, Z., Pan, Z., and Cohen, I. S. (2004) Pfluegers Arch. 447 392-400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arinsburg, S. S., Cohen, I. S., and Yu, H. G. (2006) J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 47 578-586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stoker, A. W. (2005) J. Endocrinol. 185 19-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Su, J., Muranjan, M., and Sap, J. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9 505-511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ponniah, S., Wang, D. Z., Lim, K. L., and Pallen, C. J. (1999) Curr. Biol. 9 535-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen, J., Mitcheson, J. S., Lin, M., and Sanguinetti, M. C. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 36465-36471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu, X., Chen, X. W., Zhou, P., Yao, L., Liu, T., Zhang, B., Li, Y., Zheng, H., Zheng, L. H., Zhang, C. X., Bruce, I., Ge, J. B., Wang, S. Q., Hu, Z. A., Yu, H. G., and Zhou, Z. (2007) Am. J. Physiol. 292 C1147-C1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, C. H., Zhang, Q., Teng, B., Mustafa, S. J., Huang, J. Y., and Yu, H. G. (2008) Am. J. Physiol. 294 C355-C362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zong, X., Eckert, C., Yuan, H., Wahl-Schott, C., Abicht, H., Fang, L., Li, R., Mistrik, P., Gerstner, A., Much, B., Baumann, L., Michalakis, S., Zeng, R., Chen, Z., and Biel, M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 34224-34232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Much, B., Wahl-Schott, C., Zong, X., Schneider, A., Baumann, L., Moosmang, S., Ludwig, A., and Biel, M. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 43781-43786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daum, G., Zander, N. F., Morse, B., Hurwitz, D., Schlessinger, J., and Fischer, E. H. (1991) J. Biol. Chem. 266 12211-12215 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Daum, G., Regenass, S., Sap, J., Schlessinger, J., and Fischer, E. H. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269 10524-10528 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gil-Henn, H., Volohonsky, G., and Elson, A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 31772-31779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi, W., Wymore, R., Yu, H., Wu, J., Wymore, R. T., Pan, Z., Robinson, R. B., Dixon, J. E., McKinnon, D., and Cohen, I. S. (1999) Circ. Res. 85 e1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson, R. B., Yu, H., Chang, F., and Cohen, I. S. (1997) Pfluegers Arch. 433 533-535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bartuti, A., and DiFrancesco, D. (2008) Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1123 213-223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yu, H., Chang, F., and Cohen, I. S. (1993) Circ. Res. 72 232-236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu, H., Chang, F., and Cohen, I. S. (1995) J. Physiol. (Lond.) 485 469-483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaplan, R., Morse, B., Huebner, K., Croce, C., Howk, R., Ravera, M., Ricca, G., Jaye, M., and Schlessinger, J. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87 7000-7004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahuja, P., Perriard, E., Pedrazzini, T., Satoh, S., Perriard, J. C., and Ehler, E. (2007) Exp. Cell Res. 313 1270-1283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu, H., Chang, F., and Cohen, I. S. (1993) Pfluegers Arch. 422 614-616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cerbai, E., Barbieri, M., and Mugelli, A. (1996) Circulation 94 1674-1681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoppe, U. C., and Beuckelmann, D. J. (1998) Cardiovasc. Res. 38 788-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garcia-Morales, P., Minami, Y., Luong, E., Klausner, R. D., and Samelson, L. E. (1990) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 87 9255-9259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seargeant, L. E., and Stinson, R. A. (1979) Biochem. J. 181 247-250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nof, E., Luria, D., Brass, D., Marek, D., Lahat, H., Reznik-Wolf, H., Pras, E., Dascal, N., Eldar, M., and Glikson, M. (2007) Circulation 116 463-470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Milanesi, R., Baruscotti, M., Gnecchi-Ruscone, T., and DiFrancesco, D. (2006) N. Engl. J. Med. 354 151-157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schulze-Bahr, E., Neu, A., Friederich, P., Kaupp, U. B., Breithardt, G., Pongs, O., and Isbrandt, D. (2003) J. Clin. Investig. 111 1537-1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ueda, K., Nakamura, K., Hayashi, T., Inagaki, N., Takahashi, M., Arimura, T., Morita, H., Higashiuesato, Y., Hirano, Y., Yasunami, M., Takishita, S., Yamashina, A., Ohe, T., Sunamori, M., Hiraoka, M., and Kimura, A. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 27194-27198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]