Abstract

Fluconazole (FLC) remains the antifungal drug of choice for non-life-threatening Candida infections, but drug-resistant strains have been isolated during long-term therapy with azoles. Drug efflux, mediated by plasma membrane transporters, is a major resistance mechanism, and clinically significant resistance in Candida albicans is accompanied by increased transcription of the genes CDR1 and CDR2, encoding plasma membrane ABC-type transporters Cdr1p and Cdr2p. The relative importance of each transporter protein for efflux-mediated resistance in C. albicans, however, is unknown; neither the relative amounts of each polypeptide in resistant isolates nor their contributions to efflux function have been determined. We have exploited the pump-specific properties of two antibody preparations, and specific pump inhibitors, to determine the relative expression and functions of Cdr1p and Cdr2p in 18 clinical C. albicans isolates. The antibodies and inhibitors were standardized using recombinant Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains that hyper-express either protein in a host strain with a reduced endogenous pump background. In all 18 C. albicans strains, including 13 strains with reduced FLC susceptibilities, Cdr1p was present in greater amounts (2- to 20-fold) than Cdr2p. Compounds that inhibited Cdr1p-mediated function, but had no effect on Cdr2p efflux activity, significantly decreased the resistance to FLC of seven representative C. albicans isolates, whereas three other compounds that inhibited both pumps did not cause increased chemosensitization of these strains to FLC. We conclude that Cdr1p expression makes a greater functional contribution than does Cdr2p to FLC resistance in C. albicans.

Factors identified as affecting the susceptibility of Candida albicans to azole antifungal drugs such as fluconazole (FLC) include overexpression or mutation of the drug target 14α lanosterol demethylase, mutations in other enzymes of the ergosterol pathway and increased expression of drug efflux pumps (reviewed in references 4, 40, and 53). Mediators of azole efflux from C. albicans include the major facilitator superfamily pumps Mdr1p (28) and Flu1p (1) and the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters Cdr1p and Cdr2p (4, 52). Although FLC resistance clearly can be multifactorial, high-level, clinically relevant resistance (MIC ≥ 64 μg ml−1) is most often associated with increased expression of mRNAs from the ABC genes CDR1 and CDR2 (3, 34, 37, 38). Analysis of resistance in clinical isolates has, to date, focused almost exclusively on measuring gene transcription, initially by Northern analysis (22, 41, 53), and more recently by transcript profiling and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (16, 34, 38, 55) and the use of reporter genes (24). However, the ability to compare the amounts of expressed Cdr polypeptides and, more importantly, the efflux activities of Cdr1p and Cdr2p, is crucial if the contribution of each pump protein to drug efflux function in clinical resistance is to be determined. Unfortunately, proteomic approaches using techniques such as two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (15, 17, 57) have been limited because Cdr1p and Cdr2p are high-molecular-weight membrane proteins, with very similar physiochemical properties, and are not readily resolved on two-dimensional gels.

A recently developed heterologous expression system (19) achieves consistent and equivalent hyperexpression of individual alleles of both C. albicans Cdr1p and Cdr2p in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (14, 19). The system is based on the integration of a cloning cassette, derived from plasmid pABC3 and containing the heterologous gene, into the S. cerevisiae genome at the PDR5 locus, under the control of the constitutively active PDR5 promoter (19). The heterologous gene is thus not subject to the variable expression that can occur in plasmid-based systems. The development of recombinant strains, in which the amount of pump protein produced is consistent and equivalent, allows the standardization of preparations of specific antibodies raised against each of the pumps. In addition, comparing the pump activities of the recombinant strains allows the identification of compounds that specifically inhibit Cdr1p or Cdr2p efflux activity. In the S. cerevisiae host strain seven endogenous efflux pump genes have been disrupted, and therefore the chemosensitizing effect of inhibitors on the phenotype of a recombinant strain reflects activity on the heterologous efflux pump.

A number of studies have described efflux pump inhibitors, often substrate-like molecules, which chemosensitize cells to toxic pump substrates. For example, the human ABC transporters ABCB1 (P-glycoprotein) and ABCG2 (BCRP) are inhibited by propafenone analogues (6). To reverse fungal FLC resistance, a putative chemosensitizer should be nontoxic in the absence of FLC but render a normally FLC-resistant strain more sensitive to FLC. Inhibitors of fungal ABC transporters include FK506 (30, 42), enniatin (13), milbemycins (20), unnarmicins (48), isonitrile (56), disulfiram (44), ibuprofen (36), and quinazolinone derivatives (51). Such inhibitors, or chemosensitizers, may act indirectly on aspects of metabolism that affect efflux. However, they also may act directly on the pump protein, for example, by acting as an inhibitory pseudosubstrate, as a competitive inhibitor of ATP binding, or as a noncompetitive inhibitor at sites remote from the substrate and ATP binding sites, thus affecting true substrate binding and transport. Known chemosensitizers include drugs already in therapeutic use for other conditions. FK506, for example, used in cancer chemotherapy as an immunosuppressant, may act both directly (since overexpression of Cdr1p significantly reduces susceptibility to FK506) (30, 42) and indirectly (by effects on the calcineurin pathway) (2, 12, 46, 47, 49) to reverse resistance to FLC in fungi. Ibuprofen is a potent anti-inflammatory and analgesic drug, which at low concentrations inhibits azole efflux from C. albicans, and has been proposed for combination treatment of fungal infections with FLC (36).

Thus, fungal efflux pump inhibitors may represent lead compounds for the development of drugs to abrogate resistance (42). In the present study, we have exploited the specificities of efflux pump inhibitors and antibodies to compare the relative activities and expression of Cdr1p and Cdr2p in FLC-resistant clinical isolates. Such knowledge will contribute to the development of targeted efflux inhibitors that may prevent or reverse antifungal resistance.

(This research was presented in part at the Second FEBS Advanced Lecture Course, Human Fungal Pathogens: Molecular Mechanisms of Host-Pathogen Interactions and Virulence, Nice, France, in May 2007.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains and culture conditions.

Yeast were grown on either yeast extract-peptone-dextrose medium containing 1% (wt/vol) yeast extract (Difco/Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD), 2% (wt/vol) Bacto peptone (Difco), 2% (wt/vol) d-glucose, and 2% (wt/vol) agar or complete supplement mixture (CSM) adjusted to pH 7.0, containing 0.67% (wt/vol) yeast nitrogen base (Difco), 0.077% (wt/vol) CSM supplement (Bio 101, Vista, CA), 2% (wt/vol) glucose, and 2% (wt/vol) agar or 0.6% (wt/vol) agarose (Gibco/Invitrogen Corp., Auckland, New Zealand). S. cerevisiae and C. albicans strains are described in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. C. albicans clinical isolates included azole-resistant strains and their sensitive parental strains and are identified in the text and figures by their Molecular Microbiology Laboratory (MML) strain collection number; the original strain names are given in Table 2. The collection included three pairs of isogenic strains isolated sequentially from three patients (strain MML605 and parent MML604; MML611 and parent MML610; and MML609 and parent MML607). Previous transcriptional analysis of the strains (T. C. White, unpublished data) had shown that the strains with decreased FLC susceptibilities possessed greater CDR1 and CDR2 mRNA than FLC-susceptible strains and that MDR1 mRNA was only detected in one strain (MML605). Five strains were classed as FLC sensitive according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) interpretive breakpoint criteria (FLC MIC ≤ 8 μg ml−1), and all other strains had FLC MICs between 16 and 128 μg ml−1.

TABLE 1.

S. cerevisiae strains

| Strain | Description | Genotype | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD1-8u− | MATα PDR1-3 ura3 his1Δ yor1::hisG Δsnq2::hisG Δpdr10::hisG Δpdr11::hisG Δycf1::hisG Δpdr3::hisG Δpdr15::hisG Δpdr5::hisG | 7 | |

| AD/pABC3 | AD1-8u− plus pABC3 empty cloning cassette (control) | MATα PDR1-3 ura3 his1Δ yor1::hisG Δsnq2::hisG Δpdr10::hisG Δpdr11::hisG Δycf1::hisG Δpdr3::hisG Δpdr15::hisG Δpdr5::URA3 | 19 |

| AD/CDR1 | AD1-8u− plus pABC3 cassette containing the C. albicans ATCC 10261 CDR1 ORF (A allele) | MATα PDR1-3 ura3 his1Δ yor1::hisG Δsnq2::hisG Δpdr10::hisG Δpdr11::hisG Δycf1::hisG Δpdr3::hisG Δpdr15::hisG Δpdr5::CaCDR1A-URA3 | 19 |

| AD/CDR2 | AD1-8u− plus pABC3 cassette containing the C. albicans ATCC 10261 CDR2 ORF (A allele) | MATα PDR1-3 ura3 his1Δ yor1::hisG Δsnq2::hisG Δpdr10::hisG Δpdr11::hisG Δycf1::hisG Δpdr3::hisG Δpdr15::hisG Δpdr5::CaCDR2A-URA3 | 19 |

| AD/MDR1 | AD1-8u− plus pABC3 cassette containing the C. albicans ATCC 10261 MDR1 ORF (A allele) | MATα PDR1-3 ura3 his1Δ yor1::hisG Δsnq2::hisG Δpdr10::hisG Δpdr11::hisG Δycf1::hisG Δpdr3::hisG Δpdr15::hisG Δpdr5::CaMDR1A-URA3 | 19 |

TABLE 2.

C. albicans clinical isolatesa

| Strain no. | Strain nameb | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| MML019 | TIMM3163 | 23 |

| MML610 | TL1 (parent of TL3) | 26 |

| MML611 | TL3 | 26 |

| MML604 | 2-76* (parent of 12-99) | 52 |

| MML605 | 12-99* | 52 |

| MML607 | FH1 (parent of FH8) | 26 |

| MML609 | FH8 | 26 |

| MML596 | TW 00302 | 53 |

| MML597 | TW 00305 | 53 |

| MML599 | TW 00307 | 53 |

| MML600 | TW 00313 | 53 |

| MML601 | TW 00314 | 53 |

| MML602 | TW 00315 | 53 |

| MML603 | TW 00318 | 53 |

| MML606 | TW 01801 | 39 |

| MML612 | TW 08008 | 39 |

| MML613 | TW 08047 | 39 |

| MML614 | TW 08048 | 39 |

| MML615 | TW 08053 | 39 |

All strains except TIMM3163 (Teikyo University, Tokyo, Japan) were kindly provided by T. C. White (Seattle Biomedical Research Institute, WA).

*, originally isolated by S. W. Redding, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio.

Chemicals and antifungal agents.

The chemicals and antifungal agents used in the present study were obtained from the following sources: FLC (Diflucan; Pfizer Laboratories, Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand); phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Roche Diagnostics NZ, Ltd., Auckland, New Zealand); dimethyl sulfoxide (BDH, Poole, United Kingdom); HEPES, FK506, disulfiram, rhodamine 6G (R6G) itraconazole, miconazole, and enniatin (Sigma/Penrose, Auckland, New Zealand); and ketoconazole (Janssen-Kyowa, Tokyo, Japan). The milbemycins were a gift from Sankyo Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan. Peptide RC21 was obtained by screening a library of synthetic d-octapeptides for efflux pump inhibitors (K. Niimi et al., unpublished results). R6G was prepared as a stock solution dissolved in ethanol or water; inhibitors were prepared as stock solutions dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Plasma membrane and whole-cell extract preparation.

Partially purified yeast plasma membranes were prepared as described previously (29). Cell extracts from C. albicans strains were prepared by alkaline lysis and trichloroacetic acid precipitation (5). Briefly, yeast cells, equivalent to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 5.0 in 1.0 ml from a mid-exponential-phase culture, were pelleted and then lysed by treatment for 10 min on ice with 1.85 M NaOH and 7.5% 2-mercaptoethanol (250 μl), followed by precipitation with 250 μl of 50% (wt/vol) trichloroacetic acid for 10 min on ice. For sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) separation and immunoblot analysis, the precipitate was resuspended in sample buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 8 M urea, 5% SDS, 0.1 mM EDTA, bromophenol blue [0.1 g liter−1], 1% 2-mercaptoethanol, and 10% 1 M Tris base). Protein concentrations were determined by a micro-Bradford assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with bovine gamma globulin as the standard.

SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and immunodetection.

SDS-PAGE was performed according to the Laemmli method (18) with 8% (wt/vol) acrylamide separating gels. Separated polypeptides were visualized by using Coomassie blue R250 or electroblotted (100 V, 1.5 h, 4°C) onto nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-ECL; GE Healthcare UK, Ltd., Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Immunodetection of Cdr1p or Cdr2p was performed as described previously (14). Anti-Cdr1p antibodies were kindly provided by D. Sanglard, University Hospital Lausanne, Institute of Microbiology, Lausanne, Switzerland, and anti-Cdr2p antibodies were kindly provided by M. Raymond, Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada. Immunoreactivity was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (58); images were developed on ECL Hyperfilm (GE Healthcare). In some cases, in order to confirm equivalent protein loading on Western blot membranes, after immunoblotting and chemiluminescence analysis, blots were treated with “stripping” buffer (62.5 mM Tris [pH 6.7], 2% SDS, 100 mM 2-mercaptothanol) and, after extensive washing in phosphate-buffered saline, stained with Ponceau S (0.1% [wt/vol] in 1% [vol/vol] acetic acid for 10 min; destained with water). In order to control for interblot variation, each gel and blot included control preparations of S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 and S. cerevisiae AD/CDR2 plasma membranes so that the antibody reactivities could be monitored by image analysis and confirmed as giving equivalent signal strengths for equivalent amounts of Cdr1p and Cdr2p polypeptides.

Drug susceptibility assays. (i) Liquid microdilution MIC and checkerboard chemosensitization assays.

The MICs of compounds for C. albicans strains were determined in accordance with the CLSI microdilution reference method (CLSI guidelines document M27-A2). For S. cerevisiae strains, the method was modified by using a CSM-based medium (29), because S. cerevisiae AD1-8u−, and its derivative strains, do not grow in the RPMI medium used in the CLSI method. The MICs for azoles were the minimum concentrations giving >80% growth inhibition compared to the no-drug control. The microtiter plate assay was adapted in checkerboard assays of the chemosensitization of yeast strains to FLC by various inhibitor compounds as described previously (30).

(ii) Agarose disk diffusion assays and chemosensitization disk diffusion assays.

The susceptibilities of yeast strains to different compounds were compared by using disk diffusion assays. CSM agarose (0.6% [wt/vol]; 20 ml; pH 7.0) was solidified in petri dishes, which were then overlaid with CSM agarose (0.6% [wt/vol]; 5 ml; pH 7.0) seeded with 5 ×105 yeast cells. Drugs (5 to 20 μl) at the concentrations indicated in the text were applied to sterile BBL paper disks (Becton Dickinson Co., Sparks, MD), which were then placed on the overlays (four disks per plate). Cell growth was assessed after incubation at 30°C for 48 h. For chemosensitization disk diffusion assays, FLC (at a concentration of one-quarter of the MIC of the yeast strain to be assayed) was added to both the base and the overlay agarose. Disks, to which inhibitors at the amounts indicated had been applied, were placed on the overlay plates and incubated as described above. Control plates with FLC-free agarose were also prepared to confirm that the inhibitors did not affect cell growth in the absence of FLC.

Efflux of R6G.

The effect of inhibitors on the efflux of R6G from yeast cells was determined as described previously (30, 48). Log-phase cell cultures (100 ml, OD600 = 1.3 to 1.7) grown in CSM medium were rapidly cooled on ice and stored on ice for 16 h. Cells were preloaded with R6G under energy-depleted conditions as follows. The cells were washed twice with distilled water, resuspended in HEPES buffer (100 ml, OD600 = 1.0, 50 mM HEPES-NaOH [pH 7.0]), and incubated with shaking (200 rpm, 30°C) in the presence of 5 mM 2-deoxyglucose for 30 min before the addition of R6G to 15 μM, followed by incubation for a further 30 min. Cells were washed twice and resuspended in HEPES buffer at an OD600 of 10 to 15. Cell samples (50 μl) were added to the wells of a microtiter plate that was preincubated at 30°C with inhibitors (or a buffer only control) for 5 min before the addition of the glucose (final concentration, 0.4%) to replicate wells. After incubation at 30°C for 6 min, cell suspensions were transferred to the wells of a glass-fiber filter microtiter plate (Pall Corp., East Hills, NY), and the supernatants containing effluxed R6G were collected by vacuum (−50 kPa) into the wells of 96-well black flat-bottom microtiter plates (BMG Labtechnologies GmbH, Offenburg, Germany). The fluorescence of R6G in the samples was measured by comparison to R6G standards prepared in assay buffer using a POLARstar Optima plate reader (BMG Labtechnologies) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 485 and 520 nm, respectively.

Image analysis.

All images were taken with a digital camera and processed by using Adobe Photoshop 4.0. If necessary, the contrast and brightness were adjusted by using Photoshop tools applied equally to all parts of the image, including internal blot controls. Immunoreactivities on Western blots were evaluated by using NIH Image J (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/), a publicly available computer program. In order to compare Cdr protein band intensities on different blots, the intensity values were standardized by adjusting them relative to the band intensity of the recombinant plasma membrane control on the same blot.

RESULTS

Standardization of anti-Cdr1p and anti-Cdr2p antibody preparations using recombinant S. cerevisiae strains hyperexpressing either Cdr1p or Cdr2p.

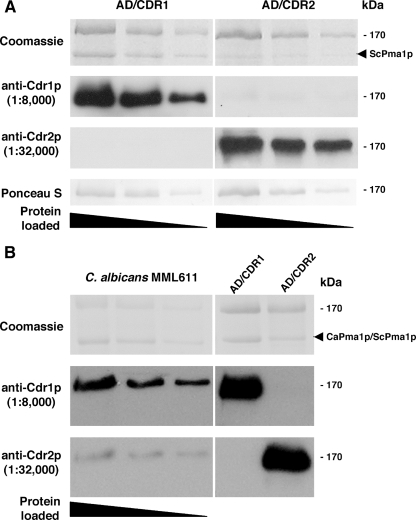

Antibody preparations were highly specific to either Cdr1p or Cdr2p (14). Recombinant S. cerevisiae strains that hyperexpressed consistent amounts of either Cdr1p or Cdr2p (19) were used as antigen sources to standardize the immunoreactivities of both antibody preparations in Western blots. We have previously shown that C. albicans CDR1 and CDR2 genes contain polymorphisms (14). The recombinant Cdr proteins used to calibrate the antibodies and Cdr proteins from clinical isolates examined, however, had conserved protein sequences in the N-terminal peptide regions to which the antibodies were raised (Holmes et al., unpublished data). Therefore, antibody reactivities were unlikely to be affected by gene polymorphisms. Plasma membranes were partially purified, as described in Materials and Methods, from a Cdr1p-expressing strain (AD/CDR1) or a Cdr2p-expressing strain (AD/CDR2), PAGE separated, and Western blotted. No significant cross-reactivity of anti-Cdr1p antibodies with the Cdr2p-expressing strain, or vice versa, was observed (Fig. 1). In initial antibody titration experiments we determined optimal dilutions of each antibody preparation (1:8,000 for anti-Cdr1p and 1:32,000 for anti-Cdr2p) giving equivalent signals with Western blots of equivalent amounts of recombinant Cdr polypeptide. These antibody dilutions were used with blots of doubling dilutions of plasma membrane preparations from either AD/CDR1 or AD/CDR2 (Fig. 1A). Equivalent protein loadings were confirmed by Coomassie blue staining of the PAGE-separated preparations and also by staining the blots with Ponceau S following the Western analysis as described in Materials and Methods. A consistent observation for plasma membrane preparations from the AD/CDR2 strain was that the amount of the polypeptide considered to be Pma1p was reduced relative to the amount detected in the AD/CDR1 strain (Fig. 1). This was an intriguing result that has been observed previously (14) but did not affect the use of the blots to calibrate the anti-Cdr1p and anti-Cdr2p antibodies. Gels were loaded such that equivalent amounts of each Cdr protein were present in the replicate gels to be blotted and incubated with each antibody. Signal strengths for the blots incubated with either of the anti-Cdr antibodies, measured using NIH Image J, were proportional to the amount of Cdr1p or Cdr2p present and gave equivalent signals for equivalent amounts of the relevant Cdr protein in the titrations (Fig. 1A). Blots shown are of representative antigen titrations. The mean Cdr1p/Cdr2p band intensity ratio, across a range of antigen dilutions on replicate blots probed with each antibody, was close to unity (1.07 ± 0.13) as determined by Image J analysis. For all subsequent experiments to determine relative Cdr protein expression in individual C. albicans strains, each gel and blot included control preparations of AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 plasma membranes. We used the standardized diluted antibody preparations to analyze replicate blots of a titrated plasma membrane preparation from MML611, an FLC-resistant C. albicans strain (Fig. 1B). Cdr1p was present in significantly greater amounts than Cdr2p. Control lanes containing plasma membrane preparations from the recombinant AD/CDR1 or AD/CDR2 strains confirmed equivalent signal strengths from the two antibody preparations. Similar results (Cdr1p expression greater than Cdr2p expression) were obtained for titrations of membrane preparations from two other FLC-resistant clinical isolates of C. albicans (MML609 and MML019; data not shown).

FIG. 1.

Expression of C. albicans ATCC 10261 Cdr1p or Cdr2p in recombinant S. cerevisiae strains AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 and in C. albicans MML611. (A) SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of plasma membrane preparations from S. cerevisiae strains serially diluted twofold. PAGE gels were stained with Coomassie blue; replicate blots were incubated with either anti-Cdr1p antibodies or anti-Cdr2p antibodies or stained with Ponceau S. Immunoreactive protein bands were detected by using chemiluminescence as described in Materials and Methods. The position of the major S. cerevisiae plasma membrane protein Pma1p is indicated on the Coomassie blue-stained gel. (B) SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis of plasma membrane preparations from C. albicans MML611 serially diluted twofold. S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 control preparations are also shown. Replicate blots were incubated with either anti-Cdr1p antibodies or anti-Cdr2p antibodies. Immunoreactive protein bands were detected by using chemiluminescence as described in Materials and Methods. The positions of the major S. cerevisiae and C. albicans plasma membrane proteins ScPma1p and CaPma1p are indicated on the Coomassie blue-stained gel.

Determination of efflux pump inhibitor specificities using S. cerevisiae strains hyperexpressing either Cdr1p or Cdr2p.

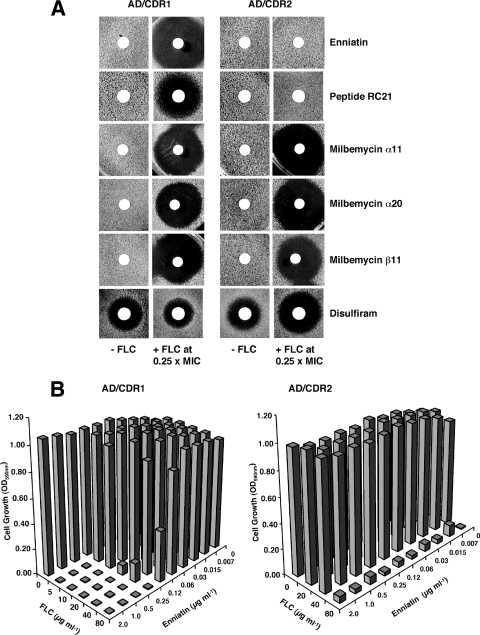

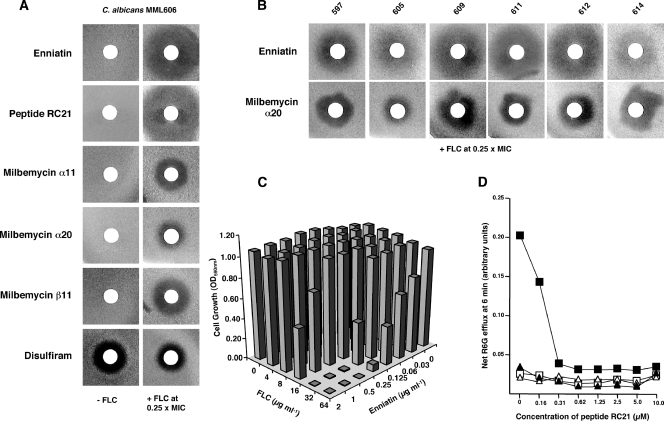

The specificities of six putative ABC-pump inhibitors for Cdr1p or Cdr2p, were investigated by determining their abilities to chemosensitize S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 to FLC in assays of yeast growth. For selected inhibitors, confirmation of a direct effect on pump activity was obtained by measuring inhibition of R6G efflux from the recombinant strains. The putative inhibitors enniatin and the milbemycins α11, α20, and β11 were shown previously to have different pump specificities (19). A peptide from a synthetic d-octapeptide compound library (27, 30) denoted RC21 has recently been identified as a specific Cdr1p inhibitor (K. Niimi and B. C. Monk, unpublished results), and disulfiram has reported activity against Cdr1p (44). The frequently studied inhibitor FK506 was not included because analysis would be complicated by its known interaction with the calcineurin stress response pathway in yeast (2, 12, 46). At the concentrations used, no compounds, except disulfiram, inhibited growth in the absence of FLC (Fig. 2A). Enniatin and peptide RC21 enhanced the growth-inhibitory effect of FLC against AD/CDR1 but not against AD/CDR2 (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the milbemycins α20, α11, and β11 were equivalently effective in chemosensitizing AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 to FLC. Disulfiram showed antifungal activity but also a slight chemosensitization of only the AD/CDR2 strain (Fig. 2A). The specificity of enniatin in inhibiting Cdr1p-mediated FLC resistance, and its failure to affect the FLC resistance of the Cdr2p-expressing S. cerevisiae AD/CDR2, was confirmed by checkerboard chemosensitization assays in liquid media (Fig. 2B). In the presence of enniatin, the FLC MIC for AD/CDR1 was significantly decreased (from 200 to <5 μg ml−1 with enniatin concentrations of ≥0.25 μg ml−1), whereas the MIC for AD/CDR2 remained unchanged at 80 μg ml−1 in the presence of up to 2 μg of enniatin ml−1. Enniatin also chemosensitized AD/CDR1, but not AD/CDR2, to R6G, a fluorescent compound that is also a substrate for a number of efflux pumps including Cdr1p and Cdr2p, and checkerboard analysis confirmed that milbemycin α11 chemosensitized both AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 to both FLC and R6G (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of putative pump inhibitors on the growth of recombinant S. cerevisiae strains in the absence or presence of FLC. (A) The growth of S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 was analyzed by agarose diffusion chemosensitization assays using CSM medium (pH 7.0) containing either no added FLC (left-hand columns) or FLC (right-hand columns) at 0.25× MIC (40 μg ml−1 for AD/CDR1; 20 μg ml−1 for AD/CDR2) as described in Materials and Methods. Paper disks containing inhibitors (2 μg of enniatin; 6 nmol of peptide RC21; 5 μg of milbemycin α11, α20, or β11; or 1.2 μg of disulfiram) were placed on the surface of agarose plates seeded with yeast. Plates were incubated at 30°C for 24 h. (B) Checkerboard chemosensitization of S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 to FLC by enniatin. Yeast cells were grown in CSM medium (pH 7.0) containing the indicated concentrations of FLC and enniatin for 24 h. Growth was measured spectophotometrically as described in Materials and Methods.

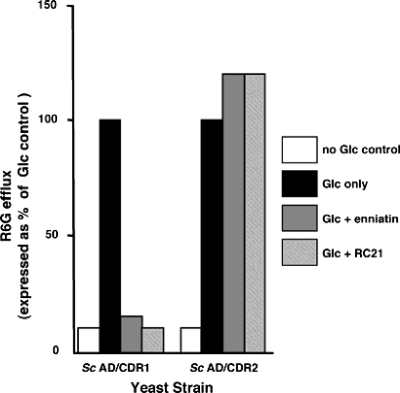

Assays of growth inhibition, such as the agarose diffusion and liquid MIC assays described above, cannot reveal whether an inhibitor has a direct or indirect effect on the efflux function of a pump protein. We therefore measured the effect of the two Cdr1p-specific inhibitors on efflux of the fluorescent substrate R6G from glucose-starved yeast cells preloaded with R6G. Glucose-dependent efflux of R6G directly reflects pump function because under these conditions negligible efflux was detected from the control parental S. cerevisiae strain AD1-8u− or from a derivative strain containing an empty pABC3 cassette (14) (data not shown). Inhibitors used at concentrations (2 μg of enniatin ml−1; 1.25 μM RC21) previously shown to chemosensitize AD/CDR1 to FLC completely inhibited the glucose-dependent efflux of R6G from AD/CDR1 cells preloaded with R6G, but not from AD/CDR2 cells (Fig. 3). In contrast, a slight stimulation of efflux was observed for AD/CDR2 in the presence of either inhibitor.

FIG. 3.

Effects of Cdr1p-specific inhibitors enniatin and peptide RC21 on R6G efflux from S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 yeast cells. The efflux of R6G from preloaded cells in the presence or absence of 0.4% glucose was measured at 6 min after glucose addition in the presence of either enniatin (2 μg ml−1) or RC21 (1.25 μM) as described in Materials and Methods. Glucose-dependent efflux is expressed relative to the amount of R6G effluxed from controls with no added inhibitor (100% values). These values were 0.40 nmol 107 cells−1 (AD/CDR1) and 0.36 nmol 107 cells−1 (AD/CDR2). Each data point represents the mean of triplicate determinations in a representative experiment repeated once. Variation from the mean did not exceed 15%.

Cdr1p and Cdr2p expression in a collection of 18 C. albicans clinical isolates.

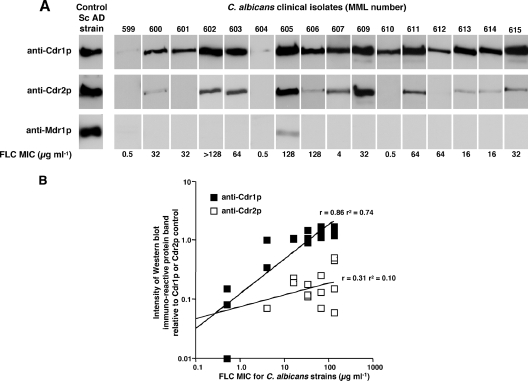

Having demonstrated that antibodies could be used to determine relative amounts of Cdr1p and Cdr2p, a simple alkaline lysis method (5) was used to prepare whole-cell extracts of C. albicans yeast cells for PAGE separation and electroblotting. This enabled the analysis of Cdrp expression in a collection of 18 clinical isolates (Table 2) kindly provided by T. C. White (Seattle, WA). Replicate PAGE gels were loaded with equivalent amounts of the whole-cell extracts from the C. albicans strains, together with AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 plasma membrane antigen controls on each set of gels. Replicate blots were incubated with either of the Cdr-specific antibody preparations at the optimal dilutions determined as described above. Cdr1p was expressed in all strains (Fig. 4A), whereas Cdr2p could not be detected in the FLC-sensitive strains MML596 (results not shown), MML599, MML604, and MML610 nor in two strains (MML601 and MML612) which had MICs of 32 and 64 μg ml−1, respectively. Replicate blots were also incubated with antibodies specific to C. albicans Mdr1p, and a signal could only be detected for strain MML605 (Fig. 4A). For all strains, the Cdr1p signal was greater than the signal obtained on the replicate blot incubated with anti-Cdr2p antibodies. Band intensities on the replicate blots were measured by using image analysis as described in Materials and Methods, where each band density value was calculated relative to an AD/CDR1 or AD/CDR2 membrane preparation control, as applicable, on the same blot. For blots incubated with anti-Cdr1p antibodies a positive relationship (r = 0.86; r2 = 0.74) with FLC MIC was obtained (Fig. 4B). In contrast, for blots reacted with anti-Cdr2p, no relationship was observed (r = 0.31; r2 = 0.10). This nonsignificant, slightly positive relationship was also present when strains without detectable Cdr2p were omitted from the calculations (r = 0.31; r2 = 0.10; data not shown). Power relationship analyses were performed by using CA-Cricket Graph III software (Computer Associates International, Inc., New York).

FIG. 4.

Relative expression of Cdr1p and Cdr2p in replicate Western blots of PAGE-separated whole-cell extracts from C. albicans clinical isolates. (A) Cell extracts were prepared as described in Materials and Methods and separated by PAGE. Each lane was loaded with an equivalent amount of total protein. Replicate blots were incubated with anti-Cdr1p antibodies (upper row) anti-Cdr2p antibodies (center row) or anti-Mdr1p (lower row) at dilutions that gave equivalent band intensities with control recombinant Cdr1p, Cdr2p or Mdr1p plasma membrane preparations run on the same gels. The control bands shown are of representative blots of AD/CDR1 (upper band) AD/CDR2 (center band) or AD/MDR1 (lower band). FLC MICs for each strain are indicated. (B) Relationships between FLC MICs for 18 C. albicans strains and Western blot band intensities obtained with either anti-Cdr1p or anti-Cdr2p antibodies. Cdrp band intensities on the blots of cell extracts, incubated with either anti-Cdr1p antibodies or anti-Cdr2p antibodies, were measured by image analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Band intensity values plotted have been corrected using the appropriate recombinant control band intensity measured on the same blot.

FLC resistance in seven C. albicans clinical isolates was decreased by inhibitors of Cdr1p-mediated FLC resistance.

Six inhibitors which had been analyzed for C. albicans Cdr pump specificity using the recombinant S. cerevisiae strains AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 (Fig. 2) were examined for chemosensitization of a representative FLC-resistant C. albicans strain (MML606; FLC MIC of 128 μg ml−1) to FLC (Fig. 5A). The chemosensitizers were used at the same concentrations used with the S. cerevisiae recombinants (Fig. 2). None of the compounds, apart from disulfiram, inhibited the growth of C. albicans in the absence of FLC (Fig. 5A, left column). The Cdr1p-specific inhibitors enniatin and RC21 strongly chemosensitized MML606 to FLC. MML606 was also chemosensitized to FLC by milbemycins α11, α20, and β11, but zones of inhibition were smaller than for enniatin or RC21 (Fig. 5A, right column). Similar results for the panel of inhibitors were obtained with strain MML611 (data not shown), which showed higher expression of Cdr2p than did strain MML606 (Fig. 4A). C. albicans strains MML606 and MML611 were also chemosensitized to itraconazole by the Cdr1p-specific inhibitor enniatin (data not shown). Disulfiram showed an antifungal effect against C. albicans MML606 but no evidence of chemosensitization to FLC (Fig. 5A, right column); similar results were observed for two other C. albicans strains, MML597 and MML611 (data not shown). Six other C. albicans strains (MML597, MML605, MML609, MML611, MML612, and MML614) for which the FLC MICs were 128, 128, 32, 64, 64, and 16 μg ml−1, respectively, selected to be representative of the full range of FLC MICs in the nonsensitive strains in the collection, were also examined in disk chemosensitization assays (Fig. 5B). The patterns of inhibition were similar to those for strain MML606; enniatin was more effective as a chemosensitizer than milbemycin α20, as demonstrated by inhibitory zone diameters. In general, the inhibitory zones for C. albicans chemosensitization (Fig. 5) were smaller than those observed for S. cerevisiae strains for the same inhibitor (Fig. 2). Since the MICs for the recombinant S. cerevisiae strains were greater than the MICs for even the most resistant C. albicans strain (Table 3), the effects of inhibitors may have been more pronounced in the S. cerevisiae strains. The Cdr1p-specific inhibitor RC21 also strongly sensitized all strains to FLC, whereas disulfiram was ineffective as a chemosensitizer, showing only antifungal activity against several C. albicans strains (data not shown), as demonstrated for MML606 (Fig. 5A).

FIG. 5.

Effect of pump inhibitors on the growth of C. albicans strains with decreased FLC susceptibilities in the absence and presence of FLC. (A) Inhibition of C. albicans MML606 growth in the absence (left column) or the presence (right column) of FLC (0.25× MIC) by the indicated compounds (amount per disk in parentheses)—enniatin (2 μg); peptide RC21 (6 nmol); milbemycin α20 (5 μg), α11 (5 μg), or β11 (5 μg); and disulfiram (1.2 μg)—as demonstrated by agarose disk chemosensitization assays using CSM medium (pH 7.0). (B) Chemosensitization of C. albicans strains to FLC (0.25× MIC) by enniatin (2 μg per disk) and milbemycin α20 (5 μg per disk) as demonstrated by agarose disk chemosensitization assays using CSM medium (pH 7.0). (C) Checkerboard chemosensitization of C. albicans MML606 to FLC by enniatin. Yeast cells were grown for 24 h in CSM medium pH 7.0 containing the indicated concentrations of FLC and enniatin. Growth was measured spectophotometrically as described in Materials and Methods. Each data point represents the mean of triplicate determinations from a representative experiment repeated once. Variation from the mean did not exceed 10%. (D) Inhibition by peptide RC21 of R6G efflux from C. albicans FLC-resistant strain MML611, but not from FLC-sensitive parental strain MML610. Suspensions of yeast cells of MML611 (squares) or MML610 (triangles), preloaded with R6G under glucose-deprived conditions as described in Materials and Methods, were preincubated with RC21 for 5 min at the concentrations indicated, before addition of glucose (0.4% [wt/vol] final concentration; filled symbols) or a buffer control solution (empty symbols). Each data point represents the mean of triplicate determinations in a representative experiment repeated once. Variation from the mean did not exceed 15%.

TABLE 3.

FLC chemosensitizing specificities of pump inhibitors as demonstrated by the FICIa

| Inhibitor | Yeast strain | FLC MIC (μg ml−1)

|

Inhibitor MIC (μg ml−1)

|

FICIb | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alone | Combined | FIC | Alone | Combined | FIC | |||

| Enniatin | S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 | 200 | <5 (0.5) | ≤0.02 | 8 | 0.25 (80) | 0.03 | <0.05* |

| S. cerevisiae AD/CDR2 | 80 | 80 (2) | 1.00 | 8 | 8 (20) | 1.00 | 2.00 | |

| C. albicans MML606 | 128 | 32 (0.5) | 0.25 | 16 | 0.25 (32) | 0.01 | 0.26* | |

| Milbemycin α11 | S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 | 200 | <5 (2) | 0.02 | 4 | 1.0 (80) | 0.25 | 0.27* |

| S. cerevisiae AD/CDR2 | 80 | <5 (2) | 0.06 | 4 | 0.5 (20) | 0.12 | 0.18* | |

| C. albicans MML606 | 128 | 32 (2) | 0.25 | >2 | 2 (32) | ≤0.50 | ≤0.75 | |

| Milbemycin β11 | S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1 | 200 | <5 (2) | ≤0.02 | 80 | 2 (80) | 0.02 | ≤0.04* |

| S. cerevisiae AD/CDR2 | 80 | 20 (2) | 0.25 | 80 | 2 (20) | 0.03 | 0.28* | |

| C. albicans MML606 | 128 | 32 (2) | 0.25 | >2 | 2 (32) | ≤0.50 | ≤0.75 | |

Cells for MIC determinations were incubated at 30°C for 24 h in CSM medium (pH 7.0). “Combined” refers to the combined MIC measured with the other compound (either inhibitor or FLC) at the concentration (in μg ml−1) indicated in parentheses.

*, Synergistic combination (33).

The decrease in resistance to FLC of strain MML606 (FLC MIC of 128 μg ml−1) caused by enniatin and milbemycins α11, α20, and β11 was confirmed by checkerboard chemosensitization assays, and the results of a representative assay for enniatin are shown in Fig. 5C. Similar results were obtained for strains MML611 and MML597, for which FLC MICs in the presence of enniatin (2 μg ml−1) were ≤4 and 16 μg ml−1 respectively, decreased from 64 and 128 μg ml−1, respectively, for FLC alone. All checkerboard results for C. albicans MML606 and for AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 are summarized in Table 3 in terms of the fractional inhibitory concentration (FIC) and FIC index (FICI). FICs were calculated by the following formula: (MIC of drug A, tested in combination with another drug B)/(MIC of drug A alone) (25). The FICI was defined as the FIC of drug A plus the FIC of drug B. In accordance with published guidelines (33), an FICI of ≤0.5 was considered to indicate synergism. The lowest FICIs were observed with the inhibition of the growth of AD/CDR1 by a combination of enniatin or milbemycin β11 with FLC (≤0.05 or ≤0.04, respectively). Enniatin was the only chemosensitizer tested that showed synergy with FLC for the FLC-resistant clinical isolate C. albicans MML606 (FICI = 0.26). Enniatin was nonsynergistic with FLC for AD/CDR2 (FICI = 2.0).

A direct role for Cdr1p in drug efflux from FLC-resistant C. albicans cells was shown by measuring the effect of Cdr1p-specific inhibitor RC21 on glucose-dependent efflux of the efflux pump substrate R6G from the FLC-resistant C. albicans strain MML611 and its FLC-sensitive parental strain MML610, which showed a much lower rate of R6G efflux than MML611, as described previously (14). RC21 inhibited R6G efflux from MML611 over a range of concentrations (0.15 to 10 μM) (Fig. 5D). RC21 at concentrations >0.31 μM inhibited R6G efflux by >80%. Negligible efflux, at the 6-min time point of the assay, was detected from the FLC-sensitive parental strain MML610, with or without added glucose, or from MML611 in the absence of glucose. Similar degrees of RC21-mediated inhibition of glucose-dependent R6G efflux from two other C. albicans FLC-resistant strains (MML 606 and MML609) were observed (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Multiple mechanisms may contribute to both experimental and clinical resistance to FLC in C. albicans (3, 4, 53). Elevated expression of CDR1 and CDR2 mRNAs, however, is observed in most strains with FLC MICs of ≥64 μg ml−1 (3, 34, 37, 38), and there are several lines of clinical and experimental evidence indicating a major role for the ABC transporters Cdr1p and/or Cdr2p in reduced susceptibility to FLC. For example, compounds that inhibit ABC transporters can markedly reverse FLC resistance; in 24 FLC-resistant C. albicans clinical isolates, significant reversion to FLC susceptibility in the presence of known inhibitors of efflux pumps was observed for 22 of the strains (36). In another study of FLC-resistant isolates from 12 human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis (35), the most frequent molecular mechanism of azole resistance was the upregulation of the ABC efflux pumps. Further experimental evidence for the importance of Cdr1p and Cdr2p in FLC resistance was provided by controlled overexpression of Cdr1p in a C. albicans CDR1-null mutant, which conferred resistance to FLC and other xenobiotics (32). In addition, disruption of the CDR1 gene of C. albicans resulted in hypersensitivity to azoles, and subsequent disruption of CDR2 in a CDR1 disruptant further increased susceptibility to azoles (41). When heterologously cloned in S. cerevisiae, CDR1 or CDR2 expression conferred resistance to a number of azole antifungals and to a variety of other chemicals (10, 14, 29, 41). Although at least 28 putative ABC transporter genes have been identified in the C. albicans genome (9), there is strong collective clinical and experimental evidence for the importance of CDR1 and CDR2 as major mediators of C. albicans FLC resistance (reviewed by Sipos and Kuchler [45]).

There is also an indication that of these two major ABC transporters, Cdr1p may be the most important contributor to FLC efflux and resistance. In a recent study, a library of >2,000 heterozygous mutants of C. albicans was screened for chemically induced haploinsufficiency using antifungal compounds, including FLC; CDR1 was identified as one of only five genes that were significantly responsive to FLC (54). CDR2 and MDR1 were characterized as unresponsive in that study. However, since the strain used was FLC sensitive, this may not reflect the situation in FLC-insensitive strains. In 32 clinical isolates of C. albicans with MICs of ≥64 μg ml−1, CDR1 expression, as determined by quantitative reverse transcription-PCR, was closely correlated with resistance (P = 0.005) (34). Although transcriptional regulators that control expression of both efflux genes (as well as a number of other stress-linked genes) have been identified, for example, Tac1p (5, 21) and Fcr1p (43), coordinate expression of CDR1 and CDR2 mRNAs in clinical isolates is not always observed (3, 34). Other factors may contribute to efflux pump gene transcription and translation; gene duplication may have a role (4), as may differential mRNA or protein stability or localization. A recent report has demonstrated that both increased CDR1 transcription and enhanced CDR1 mRNA stability contribute to the overexpression of CDR1 in two azole-resistant C. albicans strains (24). Furthermore, different Cdr proteins may have different specificities for FLC as a pump substrate, irrespective of expression levels or stability. When cloned and expressed at equivalent concentrations in the plasma membranes of recombinant S. cerevisiae strains, individual Cdr1p alleles conferred a greater resistance to FLC, and an increased rate of R6G efflux, than Cdr2p alleles (14). There has been no study, however, of the separate Cdr1p and Cdr2p functions in FLC-resistant C. albicans clinical isolates.

Our aim was to provide evidence, at the protein expression and functional level, rather than just at the transcriptional level, of the apparent dominance of Cdr1p in efflux-mediated C. albicans resistance to FLC. We made use of recombinant S. cerevisiae strains stably expressing either Cdr1p or Cdr2p to standardize antibodies specific to either Cdr1p or Cdr2p and to identify pump inhibitors that were specific for Cdr1p or that inhibited both pump proteins.

A good correlation between Western blot chemiluminescent signal strength and antigen concentration has been reported in other studies (8, 50). Specific anti-Cdr1p and anti-Cdr2p antibodies were therefore calibrated in Western blots using recombinant strains expressing each protein (Fig. 1). When tested against either purified membrane preparations from a C. albicans strain (Fig. 1B) or whole-cell extracts from 18 strains (Fig. 4A), Cdr1p was detected in all strains and consistently in greater amounts than Cdr2p. Moreover, the amount of Cdr1p detected correlated with the FLC MIC of the strains (Fig. 4B), but for the strains where Cdr2p was detectable, there was only a slight positive relationship between the Cdr2p signal strength and FLC MIC. As noted above, coordinate expression of CDR1 and CDR2 mRNAs is not always observed in clinical isolates (3, 34), which may reflect either increased CDR1 transcription and/or enhanced CDR1 mRNA stability relative to CDR2. Differential mRNA translation may result in decreased Cdr2p protein synthesis compared to Cdr1p. Alternatively, or in addition to this mechanism, the Cdr1p and Cdr2p polypeptides could possess different stabilities, such as different susceptibilities to proteolysis.

Our results indicate that under in vitro growth conditions, via a mechanism yet to be elucidated, Cdr1p is present in greater amounts than Cdr2p in both FLC-sensitive and FLC-resistant clinical isolates. Therefore, it is also important to assess the relative contributions of the two proteins to FLC efflux in C. albicans. Recombinant S. cerevisiae strains AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2, which expressed equivalent amounts of Cdr1p and Cdr2p, respectively, were used to assess the pump inhibitory activities of six putative efflux pump inhibitors by disk diffusion and liquid chemosensitization assays (Fig. 2 and Table 3). Enniatin and peptide RC21 chemosensitized AD/CDR1 to FLC but had no effect on the Cdr2p-mediated FLC resistance of AD/CDR2. RC21 also potentiated the effect of itraconazole, ketoconazole, and miconazole on AD/CDR1 but not AD/CDR2 (K. Niimi, unpublished data). Both Cdr1p-specific inhibitors appeared to act directly on efflux pump function since exposure (5 min) of yeast cells to inhibitor significantly inhibited glucose-dependent efflux of the fluorescent pump substrate R6G from the Cdr1p-expressing strain but did not inhibit efflux from the Cdr2p-expressing strain (Fig. 3). We were unable to identify a Cdr2p-specific inhibitor in the present study, and we had insufficient anti-Cdr2p antibody to test its effect as a possible pump inhibitor as demonstrated for human P-glycoprotein (11). However, three milbemycin compounds chemosensitized both AD/CDR1 and AD/CDR2 to FLC (Fig. 2A) to a similar degree, indicating that they were equivalently effective in inhibiting the activities of either Cdr1p or Cdr2p. Interestingly, disulfiram, previously shown to be a modulator of Cdr1p activity (44), showed antifungal activity but no chemosensitization of AD/CDR1 and a slight chemosensitization of AD/CDR2 to FLC (Fig. 2A). Although inhibition of the in vitro activity of purified Cdr1p by disulfiram was clearly demonstrated by Shukla et al. (44), in that study growth effects were assessed by agar dilution assays, which can accentuate minor growth-inhibitory effects (31).

Having identified enniatin and RC21 as Cdr1p-specific inhibitors, and milbemycins as inhibiting both Cdr1p and Cdr2p, we compared the abilities of these compounds to reduce the FLC resistance of a representative FLC-resistant C. albicans strain (MML606; FLC MIC of 128 μg ml−1) at concentrations shown to have equivalent inhibitory effects (for the non-Cdr1p-specific inhibitors) on heterologously expressed Cdr1p and Cdr2p (Fig. 2A). Enniatin and RC21 were the most effective chemosensitizers (Fig. 4A and Table 3). When assessed for synergy with FLC against MML606, the Cdr1p-specific inhibitor enniatin, but not milbemycins α11 and β11, which acted equally against both Cdr1p and Cdr2p, demonstrated significant synergy with FLC (FICI ≤ 0.5). It was also of note that although dilsulfiram chemosensitized AD/CDR2 to FLC, it had no chemosensitizing activity against C. albicans. We interpret these results as indicating that Cdr1p is the most active pump in MML606 under these growth conditions. The inhibitors enniatin and milbemycin α20 were compared in agarose disk chemosensitization assays with seven other C. albicans strains with reduced susceptibilities to FLC (Fig. 5A). Both enniatin and α20 chemosensitized all of the strains to FLC, but in six of seven strains enniatin was the more effective chemosensitizer, as demonstrated by the inhibitory zone diameters. This was confirmed by checkerboard chemosensitization assays (shown for enniatin in Fig. 5C). Enniatin was also shown to chemosensitize C. albicans to itraconazole (data not shown). These results, and those shown in Fig. 2A, suggest a negligible role for Cdr2p in azole efflux from the C. albicans strains. However, access of inhibitors to the target pump protein may vary between S. cerevisiae and C. albicans cells and, in the absence of Cdr2p-specific inhibitors, we cannot confirm this conclusion.

Direct inhibition of efflux activity from FLC-resistant C. albicans was confirmed for the Cdr1p-specific inhibitor, RC21, by assays of R6G efflux (Fig. 5D). At concentrations that abrogated R6G efflux from S. cerevisiae AD/CDR1, RC21 inhibited glucose-dependent efflux from MML611 by >80%. Similar results were also observed for two other C. albicans strains (MML606 and MML609), but data are shown for strain MML611 in order to compare directly a FLC-sensitive parental strain (MML610) and a derivative strain with reduced FLC susceptibility (MML611). A small amount of glucose-dependent R6G efflux was detected in RC21-exposed MML611 cells which was consistently slightly greater than that from the controls (Fig. 5D). This residual efflux may represent a low level of Cdr2p activity in C. albicans MML611 since we have demonstrated that Cdr2p is not inhibited by RC21.

Collectively, our results indicate that in C. albicans Cdr1p efflux activity makes a greater contribution than Cdr2p to resistance to FLC. Another experimental approach that would strengthen such a conclusion would be to examine the effects of deleting either CDR1 or CDR2 on the resistance to FLC of a clinical isolate(s). Such experiments were beyond the scope of the present study. The development of chemosensitizers, including pump inhibitors, as synergists with well-tolerated antifungals such as FLC is considered to be a feasible strategy to overcome clinical antifungal resistance (42). Currently available antifungal drugs are few, and the threat of resistance is always present. In the development of novel FLC chemosensitizers as potential synergists, it is important to target the principal mechanism of resistance. In the case of efflux pump inhibitors, determining which of the major efflux pumps of C. albicans is contributing to efflux activity would aid the design of new chemosensitizers with the required specificity. We present here direct evidence that Cdr1p activity is the major contributor to FLC efflux in C. albicans strains, including clinical isolates with reduced susceptibilities to FLC.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institutes of Health (R21DE015075-RDC; R01DE016885-01-RDC), a Health and Labor Sciences Research Grant for Research on Emerging and Re-emerging Infectious Diseases (Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare of Japan), and the New Zealand Lottery Grants Board.

We thank Ted White, Seattle Biomedical Research Institute and University of Washington School of Public Health and Community Medicine, Seattle, for kindly supplying C. albicans strains, and Dominique Sanglard, University Hospital Lausanne, Institute of Microbiology, Lausanne, Switzerland, and Martine Raymond, Institute for Research in Immunology and Cancer, University of Montreal, Montreal, Quebec, Canada, for kindly providing antibodies. The milbemycins were a gift from Sankyo Pharmaceuticals, Tokyo, Japan, to M.N. We are grateful for the free availability of the Candida Genome Database (CGD; http://www.candidagenome.org/).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 18 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Calabrese, D., J. Bille, and D. Sanglard. 2000. A novel multidrug efflux transporter gene of the major facilitator superfamily from Candida albicans (FLU1) conferring resistance to fluconazole. Microbiology 146:2743-2754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cannon, R. D., E. Lamping, A. R. Holmes, K. Niimi, K. Tanabe, M. Niimi, and B. C. Monk. 2007. Candida albicans drug resistance another way to cope with stress. Microbiology 153:3211-3217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chau, A. S., C. A. Mendrick, F. J. Sabatelli, D. Loebenberg, and P. M. McNicholas. 2004. Application of real-time quantitative PCR to molecular analysis of Candida albicans strains exhibiting reduced susceptibility to azoles. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2124-2131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coste, A., A. Selmecki, A. Forche, D. Diogo, M. E. Bougnoux, C. d'Enfert, J. Berman, and D. Sanglard. 2007. Genotypic evolution of azole resistance mechanisms in sequential Candida albicans isolates. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1889-1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coste, A. T., M. Karababa, F. Ischer, J. Bille, and D. Sanglard. 2004. TAC1, transcriptional activator of CDR genes, is a new transcription factor involved in the regulation of Candida albicans ABC transporters CDR1 and CDR2. Eukaryot. Cell 3:1639-1652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cramer, J., S. Kopp, S. E. Bates, P. Chiba, and G. F. Ecker. 2007. Multispecificity of drug transporters: probing inhibitor selectivity for the human drug efflux transporters ABCB1 and ABCG2. Chem. Med. Chem. 2:1783-1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decottignies, A., M. Kolaczkowski, E. Balzi, and A. Goffeau. 1994. Solubilization and characterization of the overexpressed PDR5 multidrug resistance nucleotide triphosphatase of yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 269:12797-12803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frederiksen, P. D., S. Thiel, L. Jensen, A. G. Hansen, F. Matthiesen, and J. C. Jensenius. 2006. Quantification of mannan-binding lectin. J. Immunol. Methods 315:49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaur, M., D. Choudhury, and R. Prasad. 2005. Complete inventory of ABC proteins in human pathogenic yeast, Candida albicans. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 9:3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gauthier, C., S. Weber, A. M. Alarco, O. Alqawi, R. Daoud, E. Georges, and M. Raymond. 2003. Functional similarities and differences between Candida albicans Cdr1p and Cdr2p transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1543-1554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goda, K., F. Fenyvesi, Z. Bacso, H. Nagy, T. Marian, A. Megyeri, Z. Krasznai, I. Juhasz, M. Vecsernyes, and G. Szabo, Jr. 2007. Complete inhibition of P-glycoprotein by simultaneous treatment with a distinct class of modulators and the UIC2 monoclonal antibody. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 320:81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heitman, J. 2005. Cell biology: a fungal Achilles' heel. Science 309:2175-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hiraga, K., S. Yamamoto, H. Fukuda, N. Hamanaka, and K. Oda. 2005. Enniatin has a new function as an inhibitor of Pdr5p, one of the ABC transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 328:1119-1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holmes, A. R., S. Tsao, S. W. Ong, E. Lamping, K. Niimi, B. C. Monk, M. Niimi, A. Kaneko, B. R. Holland, J. Schmid, and R. D. Cannon. 2006. Heterozygosity and functional allelic variation in the Candida albicans efflux pump genes CDR1 and CDR2. Mol. Microbiol. 62:170-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooshdaran, M. Z., K. S. Barker, G. M. Hilliard, H. Kusch, J. Morschhauser, and P. D. Rogers. 2004. Proteomic analysis of azole resistance in Candida albicans clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:2733-2735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karababa, M., A. T. Coste, B. Rognon, J. Bille, and D. Sanglard. 2004. Comparison of gene expression profiles of Candida albicans azole-resistant clinical isolates and laboratory strains exposed to drugs inducing multidrug transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:3064-3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kusch, H., K. Biswas, S. Schwanfelder, S. Engelmann, P. D. Rogers, M. Hecker, and J. Morschhauser. 2004. A proteomic approach to understanding the development of multidrug-resistant Candida albicans strains. Mol. Genet. Genomics 271:554-565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laemmli, U. K., and S. F. Quittner. 1974. Maturation of the head of bacteriophage T4. IV. The proteins of the core of the tubular polyheads and in vitro cleavage of the head proteins. Virology 62:483-499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamping, E., B. C. Monk, K. Niimi, A. R. Holmes, S. Tsao, K. Tanabe, M. Niimi, Y. Uehara, and R. D. Cannon. 2007. Characterization of three classes of membrane proteins involved in fungal azole resistance by functional hyperexpression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell 6:1150-1165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee, M. D., J. L. Galazzo, A. L. Staley, J. C. Lee, W. Warren, H. Fuernkranz, S. Chamberland, O. Lomovskaya, and G. H. Miller. 2001. Microbial fermentation-derived inhibitors of efflux-pump-mediated drug resistance. Il Farmaco. 56:81-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, T. T., S. Znaidi, K. S. Barker, L. Xu, R. Homayouni, S. Saidane, J. Morschhauser, A. Nantel, M. Raymond, and P. D. Rogers. 2007. Genome-wide expression and location analyses of the Candida albicans Tac1p regulon. Eukaryot. Cell 6:2122-2138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lopez-Ribot, J. L., R. K. McAtee, L. N. Lee, W. R. Kirkpatrick, T. C. White, D. Sanglard, and T. F. Patterson. 1998. Distinct patterns of gene expression associated with development of fluconazole resistance in serial Candida albicans isolates from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with oropharyngeal candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 42:2932-2937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maebashi, K., M. Niimi, M. Kudoh, F. J. Fischer, K. Makimura, K. Niimi, R. J. Piper, K. Uchida, M. Arisawa, R. D. Cannon, and H. Yamaguchi. 2001. Mechanisms of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans isolates from Japanese AIDS patients. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 47:527-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Manoharlal, R., N. A. Gaur, S. L. Panwar, J. Morschhauser, and R. Prasad. 2008. Transcriptional activation and increased mRNA stability contribute to overexpression of CDR1 in azole-resistant Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1481-1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchetti, O., P. Moreillon, M. P. Glauser, J. Bille, and D. Sanglard. 2000. Potent synergism of the combination of fluconazole and cyclosporine in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 44:2373-2381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marr, K. A., C. N. Lyons, K. Ha, T. R. Rustad, and T. C. White. 2001. Inducible azole resistance associated with a heterogeneous phenotype in Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:52-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monk, B. C., K. Niimi, S. Lin, A. Knight, T. B. Kardos, R. D. Cannon, A. King, D. Lun, and D. R. K. Harding. 2005. Surface-active fungicidal d-peptide inhibitors of the plasma membrane proton pump that block azole resistance. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:57-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morschhauser, J., K. S. Barker, T. T. Liu, J. Blass-Warmuth, R. Homayouni, and P. D. Rogers. 2007. The transcription factor Mrr1p controls expression of the MDR1 efflux pump and mediates multidrug resistance in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 3:e164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nakamura, K., M. Niimi, K. Niimi, A. R. Holmes, J. E. Yates, A. Decottignies, B. C. Monk, A. Goffeau, and R. D. Cannon. 2001. Functional expression of Candida albicans drug efflux pump Cdr1p in a Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain deficient in membrane transporters. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:3366-3374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niimi, K., D. R. Harding, R. Parshot, A. King, D. J. Lun, A. Decottignies, M. Niimi, S. Lin, R. D. Cannon, A. Goffeau, and B. C. Monk. 2004. Chemosensitization of fluconazole resistance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and pathogenic fungi by a d-octapeptide derivative. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 48:1256-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Niimi, K., K. Maki, F. Ikeda, A. R. Holmes, E. Lamping, M. Niimi, B. C. Monk, and R. D. Cannon. 2006. Overexpression of Candida albicans CDR1, CDR2, or MDR1 does not produce significant changes in echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:1148-1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niimi, M., K. Niimi, Y. Takano, A. R. Holmes, F. J. Fischer, Y. Uehara, and R. D. Cannon. 2004. Regulated overexpression of CDR1 in Candida albicans confers multidrug resistance. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 54:999-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Odds, F. C. 2003. Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52:1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Park, S., and D. S. Perlin. 2005. Establishing surrogate markers for fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans. Microb. Drug Resist. 11:232-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perea, S., J. L. Lopez-Ribot, W. R. Kirkpatrick, R. K. McAtee, R. A. Santillan, M. Martinez, D. Calabrese, D. Sanglard, and T. F. Patterson. 2001. Prevalence of molecular mechanisms of resistance to azole antifungal agents in Candida albicans strains displaying high-level fluconazole resistance isolated from human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2676-2684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pina-Vaz, C., A. G. Rodrigues, S. Costa-de-Oliveira, E. Ricardo, and P. A. Mardh. 2005. Potent synergic effect between ibuprofen and azoles on Candida resulting from blockade of efflux pumps as determined by FUN-1 staining and flow cytometry. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:678-685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro, M. A., C. R. Paula, R. John, J. R. Perfect, and G. M. Cox. 2005. Phenotypic and genotypic evaluation of fluconazole resistance in vaginal Candida strains isolated from HIV-infected women from Brazil. Med. Mycol. 43:647-650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers, P. D., and K. S. Barker. 2003. Genome-wide expression profile analysis reveals coordinately regulated genes associated with stepwise acquisition of azole resistance in Candida albicans clinical isolates. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:1220-1227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rustad, T. R., D. A. Stevens, M. A. Pfaller, and T. C. White. 2002. Homozygosity at the Candida albicans MTL locus associated with azole resistance. Microbiology 148:1061-1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sanglard, D., and J. Bille. 2002. Current understanding of the modes of action of and resistance mechanisms to conventional and emerging antifungal agents for treatment of Candida infections, p. 349-383. In R. Calderone (ed.), Candida and candidiasis. ASM Press, Washington, DC.

- 41.Sanglard, D., F. Ischer, M. Monod, and J. Bille. 1997. Cloning of Candida albicans genes conferring resistance to azole antifungal agents: characterization of CDR2, a new multidrug ABC transporter gene. Microbiology 143:405-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuetzer-Muehlbauer, M., B. Willinger, R. Egner, G. Ecker, and K. Kuchler. 2003. Reversal of antifungal resistance mediated by ABC efflux pumps from Candida albicans functionally expressed in yeast. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 22:291-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shen, H., M. M. An, J. Wang de, Z. Xu, J. D. Zhang, P. H. Gao, Y. Y. Cao, Y. B. Cao, and Y. Y. Jiang. 2007. Fcr1p inhibits development of fluconazole resistance in Candida albicans by abolishing CDR1 induction. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 30:68-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shukla, S., Z. E. Sauna, R. Prasad, and S. V. Ambudkar. 2004. Disulfiram is a potent modulator of multidrug transporter Cdr1p of Candida albicans. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 322:520-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sipos, G., and K. Kuchler. 2006. Fungal ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in drug resistance and detoxification. Curr. Drug Targets 7:471-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Steinbach, W. J., J. L. Reedy, R. A. Cramer, Jr., J. R. Perfect, and J. Heitman. 2007. Harnessing calcineurin as a novel anti-infective agent against invasive fungal infections. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 5:418-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun, S., Y. Li, Q. Guo, C. Shi, J. Yu, and L. Ma. 2008. In vitro interactions between tacrolimus and azoles against Candida albicans determined by different methods. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:409-417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tanabe, K., E. Lamping, K. Adachi, Y. Takano, K. Kawabata, Y. Shizuri, M. Niimi, and Y. Uehara. 2007. Inhibition of fungal ABC transporters by unnarmicin A and unnarmicin C, novel cyclic peptides from marine bacterium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 364:990-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Uppuluri, P., J. Nett, J. Heitman, and D. Andes. 2008. Synergistic effect of calcineurin inhibitors and fluconazole against Candida albicans biofilms. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:1127-1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Warren, C. A., L. Mok, S. Gordon, A. F. Fouad, and M. S. Gold. 2008. Quantification of neural protein in extirpated tooth pulp. J. Endod. 34:7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Watkins, W. J., L. Chong, A. Cho, R. Hilgenkamp, M. Ludwikow, N. Garizi, N. Iqbal, J. Barnard, R. Singh, D. Madsen, K. Lolans, O. Lomovskaya, U. Oza, P. Kumaraswamy, A. Blecken, S. Bai, D. J. Loury, D. C. Griffith, and M. N. Dudley. 2007. Quinazolinone fungal efflux pump inhibitors. Part 3. (N-Methyl)piperazine variants and pharmacokinetic optimization. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 17:2802-2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.White, T. C. 1997. Increased mRNA levels of ERG16, CDR, and MDR1 correlate with increases in azole resistance in Candida albicans isolates from a patient infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 41:1482-1487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White, T. C., S. Holleman, F. Dy, L. F. Mirels, and D. A. Stevens. 2002. Resistance mechanisms in clinical isolates of Candida albicans. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1704-1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Xu, D., B. Jiang, T. Ketela, S. Lemieux, K. Veillette, N. Martel, J. Davison, S. Sillaots, S. Trosok, C. Bachewich, H. Bussey, P. Youngman, and T. Roemer. 2007. Genome-wide fitness test and mechanism-of-action studies of inhibitory compounds in Candida albicans. PLoS Pathog. 3:e92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu, Z., L. X. Zhang, J. D. Zhang, Y. B. Cao, Y. Y. Yu, D. J. Wang, K. Ying, W. S. Chen, and Y. Y. Jiang. 2006. cDNA microarray analysis of differential gene expression and regulation in clinically drug-resistant isolates of Candida albicans from bone marrow transplanted patients. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296:421-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yamamoto, S., K. Hiraga, A. Abiko, N. Hamanaka, and K. Oda. 2005. A new function of isonitrile as an inhibitor of the Pdr5p multidrug ABC transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 330:622-628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan, L., J. D. Zhang, Y. B. Cao, P. H. Gao, and Y. Y. Jiang. 2007. Proteomic analysis reveals a metabolism shift in a laboratory fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans strain. J. Proteome. Res. 6:2248-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yasar, U., G. Tybring, M. Hidestrand, M. Oscarson, M. Ingelman-Sundberg, M. L. Dahl, and E. Eliasson. 2001. Role of CYP2C9 polymorphism in losartan oxidation. Drug Metab. Dispos. 29:1051-1056. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]