Abstract

Parvovirus capsids are assembled from multiple forms of a single protein and are quite stable structurally. However, in order to infect cells, conformational plasticity of the capsid is required and this likely involves the exposure of structures that are buried within the structural models. The presence of functional asymmetry in the otherwise icosahedral capsid has also been proposed. Here we examined the protein composition of canine parvovirus capsids and evaluated their structural variation and permeability by protease sensitivity, spectrofluorometry, and negative staining electron microscopy. Additional protein forms identified included an apparent smaller variant of the virus protein 1 (VP1) and a small proportion of a cleaved form of VP2. Only a small percentage of the proteins in intact capsids were cleaved by any of the proteases tested. The capsid susceptibility to proteolysis varied with temperature but new cleavages were not revealed. No global change in the capsid structure was observed by analysis of Trp fluorescence when capsids were heated between 40°C and 60°C. However, increased polarity of empty capsids was indicated by bis-ANS binding, something not seen for DNA-containing capsids. Removal of calcium with EGTA or exposure to pHs as low as 5.0 had little effect on the structure, but at pH 4.0 changes were revealed by proteinase K digestion. Exposure of viral DNA to the external environment started above 50°C. Some negative stains showed increased permeability of empty capsids at higher temperatures, but no effects were seen after EGTA treatment.

The capsids of animal viruses are molecular machines that serve many functions in the viral life cycle. For parvoviruses, a small number of overlapping proteins make up the capsids and serve multiple intricate functions. These include protecting the genome from the environment, interacting with host receptors and antibodies, targeting the particle to the correct cells and tissues, controlling the process of cell uptake, trafficking the genome to the nucleus during cell infection, and releasing their single-stranded DNA at the correct cellular location for replication. The canine parvovirus (CPV) capsid has been considered to have a superficially simple structure which is assembled from 60 copies of a combination of two proteins, virus protein 1 (VP1) (84 kDa) and VP2 (67 kDa) (32, 53). About 90% of the protein in the capsid is VP2, and 10% is VP1, which contains the entire VP2 sequence and 143 additional residues at its N terminus (43). The five or six copies of the VP1 N-terminal sequence are sequestered from antibody binding and their distribution within the T=1 icosahedron is unknown (31). In full (DNA-containing) capsids, some VP2 proteins can be converted to the ∼63-kDa VP3 by proteolytic cleavage of approximately 19 amino acids from the N terminus (57). This cleavage is not seen in empty (non-DNA-containing) capsids. CPV is transmitted by the fecal-oral route, and the viruses are stable in the intestinal contents and feces of animals and may persist in the environment for days or weeks before infecting another host (14).

The parvoviruses related to CPV include three variants which have >99% sequence identity but which differ in host range, receptor binding, and antigenic structure (20, 49). The ancestral feline panleukopenia virus (FPV) of cats mutated to create the original strain of CPV, termed CPV type 2 (CPV-2), which spread around the world in 1978 (40). A variant strain called CPV-2a replaced CPV-2 worldwide during 1979 and 1980 and contained changes of VP2 residues 87, 101, 300, and 305 (35, 37, 41). The CPV-2a variant is antigenically different from CPV-2, has an altered host range for cats (52), and has a reduced binding to the feline transferrin receptor (TfR) (30). Since 1980, a variety of additional mutants have arisen in the CPV-2a background, including changes of VP2 residues 426 (Asn to Asp; then from Asp to Glu), and 297 (Ser to Ala) (4, 36).

The primary cell receptor for FPV and CPV is the host TfR (33). CPV and FPV capsids both bind the feline TfR, while CPV capsids also bind the canine TfR, and that binding is a primary determinant of canine host range (17, 19). Canine TfR binding is dictated by residues in at least three distinct positions on the capsid surface, including VP2 residues 93, 299, and 323 (20, 34). Structural studies of the feline TfR bound to the CPV-2 capsid defined the receptor footprint and also indicated that the receptor occupied only a few of the 60 potential binding sites on the T=1 capsid (16). Possible reasons for the low occupancy of receptor binding might include inherent asymmetry of the capsid, where only a limited number of binding sites are displayed, or structural changes in the capsid induced upon receptor binding which prevent further receptors from attaching. Also, receptors initially bound to the capsid might sterically hinder the binding of additional TfRs, but models predict that 20 to 24 receptors should still be able to bind to a capsid.

VP1 and VP2 contain a common core β-barrel structure, where the capsid surface is formed by large loops inserted between some of the β-strands. Prominent surface features include distinct depressions at the twofold axes of icosahedral symmetry and surrounding the fivefold axes and a raised region around the threefold axes containing the binding sites for canine or feline TfR as well as antibodies (16, 49, 58). Pores of ∼10-Å diameter at the fivefold axes of symmetry are each surrounded by a cylinder made up of five β-ribbons. The pores are hypothesized to allow exposure of the 5′ end of the viral DNA outside the capsid after DNA packaging (10) and also seem to promote the exposure of the VP2 N termini in full (i.e., DNA-containing) particles (8, 57).

The dynamic properties, flexibility, and alternative structures of viral proteins are important for their various functions. Some type of activation has been shown to be required by many viruses for them to become infectious. Triggers that control infectivity may include receptor binding, proteolysis of viral proteins, exposure to low pH, removal of ions bound within the capsid structure, or specific rearrangement of capsid bonds (such as disulfide bonds) (21, 48). These triggers and the resulting changes in capsid structure can control virus uptake into the cell, allow membrane penetration or fusion, control correct trafficking within the endosomal system, and/or determine the success of cytoplasmic trafficking or nuclear delivery (27, 47).

Structural comparisons of CPV, FPV, and host range variants of those viruses revealed that many of the host range-determining differences were due to altered configurations of hydrogen bonds, with only subtle changes in the overall capsid protein structures (1, 23). However, those changes clearly affect canine TfR binding and in some cases also modify the binding of specific antibodies (15, 30). Their significant functional effects might therefore be the result of alterations in the flexibility of key capsid structures that control receptor or antibody binding (1, 15, 49).

Crystallography studies have shown some flexibility or altered structures of the CPV and FPV capsid proteins when exposed to low pH or after removal of bound Ca2+ ions (45). In CPV-2 capsids, two Ca2+ ions are coordinated by clusters of Asp and His residues, and a third Ca2+ binding site is present in FPV and probably CPV-2a (45). Those ions are located at the interfaces between the protein subunits and stabilize certain capsid loops (45). Equivalent ion binding sites are not seen in the same positions of capsids of related parvoviruses, such as the minute virus of mice (MVM) (2, 24). At pHs of 6.2 and 5.5, the capsids exhibit only relatively minor structural changes, with the greatest effect being an increased flexibility of a surface loop between VP2 residues 359 and 372, in part due to the release of the Ca2+ (45).

In many parvoviruses, the VP1 unique sequence contains a phospholipase A2 enzyme domain that is required for successful infection. This domain is sequestered in the capsid but becomes exposed during cellular uptake and infection or after heating to temperatures above 45°C in vitro (9, 56, 61). The phospholipase A2 likely modifies the endosomal membrane to facilitate particle release during infection (12, 50). The VP1 N-terminal sequences also contain basic sequences that resemble classical importin-dependent nuclear localization sequences which would also need to be exposed in the cytoplasm (55).

Here we used a variety of methods to examine the structural variability of CPV and related virus capsids, analyzing both wild-type capsids and those of specific mutants that affect antibody or TfR binding. The capsids were in general very stable, but low levels of structural variability were detected under certain conditions by a broad-activity proteinase and by probes for protein polarity. At increased temperatures, negative stains showed increased penetration of empty capsids and viral DNA became exposed under conditions where the capsids otherwise remained intact. Minor amounts of previously unrecognized capsid protein forms were also identified within the viral capsids.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Viruses, cells, and proteins.

Viruses include the prototype isolates of CPV-2 (CPV-d), FPV (FPV-b), and CPV-2b (CPV-39) (19, 35) as well as mutations with VP2 residue 297 changed from Ser to Ala (FPV S297A, CPV-2 S297A, or CPV-2b S297A) or CPV-2 with VP2 residue 299 changed from Gly to Glu (CPV-2 G299E) or residue 300 changed from Ala to Asp (CPV-2 A300D). Viruses were isolated from infectious plasmid clones and grown in feline NLFK cells in a 1:1 mixture of McCoy's 5A and Liebovitz L15 media with 5% fetal bovine serum (35).

Capsids were in most cases prepared and purified as reported previously (1). In short, virus was precipitated with polyethylene glycol 8000 (PEG 8000), and full and empty capsids were purified by banding on 10 to 40% sucrose gradients. Capsids were passed through a Sepharose CL-4B column in 50 mM piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid) (PIPES)-NaOH (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl to remove contaminating proteins and loosely associated peptides. In an alternative method, capsids were purified from infected cells by banding in step gradients of iodixanol (Optiprep; Axis Shield, Oslo, Norway) (11). For the iodixanol method, cells were infected and incubated for 2 days and then scraped into 0.15 M NaCl, 50 mM Tris HCl (pH 7.5) after the initial medium had been removed. After three freeze-thaw cycles, the addition of 50 U/ml of benzonase, and pelleting of debris for 20 min at 30,000 × g, capsids in the supernatant were then banded in step gradients of 15, 30, 45, and 60% iodixanol at 110,000 × g for 6.5 h at 25°C. The virus-containing band was passed through a G100 column and then separated into full and empty capsid fractions by a linear gradient of 10% to 30% glycerol at 83,000 × g for 4.5 h at 25°C. Particles were passed through Sephadex G100 and Sepharose CL-4B columns in 50 mM PIPES-NaOH (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, and virus concentration was determined by the micro-bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce, Rockford, IL).

The relative infectivities of the purified full capsid preparations were calculated from the number of viral genomes per capsid, compared to what was seen for the infectious titers, and the effects of purification determined by comparing virus in tissue culture medium with the purified full capsids. DNA genome copy numbers were determined by quantitative PCR (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primers were designed to bind to a conserved region in the viral genome between nucleotides 1039 and 1114 of the viral genome (encoding NS1). Absolute copy numbers were inferred from standard curves of linearized plasmids containing the CPV sequence and analyzed using a StepOne machine (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Infectious titers were determined by 50% tissue culture infective dose (TCID50) analysis (60).

The ectodomains of the feline and canine TfRs were purified after baculovirus expression as described previously (18, 30). The isolation and purification of monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) F and 15 have been described previously (28, 38, 39).

Proteolytic analysis of CPV capsids.

Proteases tested included trypsin, thermolysin, proteinase K, subtilisin, bromelin, and papain (all from Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Proteases were kept at −80°C in their respective storage buffers and diluted in reaction buffer immediately before each experiment (Table 1). Protease activities under various buffer, temperature, pH, or EGTA conditions were calibrated with the Quanticleave assay with fluorescein isothiocyanate-labeled casein (Pierce, Rockford, IL) by use of a fluorescence plate reader (Tecan Safire, Durham, NC). Most assays were conducted using proteinase K, and the multiples of amounts required to give equivalent activities were as follows: for 21°C, ×1.51; for 37°C, ×1; for 45°C, ×0.87; for 55°C, ×0.81; for pH 7.6, ×1; for pH 6.0, ×1.92; for pH 5.0, ×3.65; and for pH 4.0, ×7.7. Proteinase K activity was not affected by the addition of EGTA over the time of the experiment.

TABLE 1.

| Protease | Specificity | Storage buffer | Dilution buffer | Inhibitor used |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proteinase K | Hydrophobic aliphatics and aromatics | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mM CaCl2 | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mM CaCl2 | PMSF |

| Papain | Broad specificity, hydrophobics (P2), not valine (P1) | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) | Sigma protease inhibitor |

| Trypsin | Lys, Arg | 1 mM HCl | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) | PMSF |

| Thermolysin | Bulky hydrophobics | 20 mM CaCl2 | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8), 5 mM CaCl2 | EDTA |

| Subtisilin | Most | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) | PMSF |

| Bromelain | Nonspecific | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) | 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8) | TPCK |

PMSF, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride; TPCK, N-p-tosyl-l-phenylalanine chloromethyl ketone; sigma protease inhibitor contains AEBSF, pepstatinA, E-64, bestatin, leupeptin, and aprotinin.

Analysis of proteins, cleavage sites, and comparison of different viruses.

Capsid sensitivity to proteinase K was tested in the presence of 0 to 50 mM EGTA, at 21, 37, 45, or 55°C, or at pHs 7.6, 6.0, 5.0, or 4.0. After incubation with proteinase K, Laemmli sample buffer with an excess of specific protease inhibitor was added and samples were placed in a boiling water bath for 5 min. Samples were analyzed in 10% acrylamide gels, stained with Coomassie blue G-250 (Pierce, Rockford, IL), and imaged (Syngene, Frederick, MD). To determine the effects of specific ligands bound to the capsids on the capsid proteolysis patterns, purified feline or canine TfR ectodomains or Fabs of MAbs F and 15 were incubated with the capsids for 1 h at 37°C, and then the mixtures treated with proteases at 37°C and analyzed as described above.

To determine VP3 N-terminal sequences after proteinase digestions, proteins were transferred to 0.22-μm polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Immobilon Psq, Millipore, Billerica, MA), and N terminally sequenced (Alphalyse, Palo Alto, CA). Antibodies used for Western blotting included mouse antisera raised against peptides containing VP2 residues 222 to 238, 292 to 310, 387 to 398, or 508 to 522, which had been conjugated to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. The N-terminal region of VP1 was detected with MAb S2D3, recognizing VP1 residues 2 to 11 (56).

Identification of proteolytic products in solution or from sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) bands was conducted using both electrospray and matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization to minimize detection bias and increase coverage in mapping experiments. Electrospray instrumentation included an Agilent XCT Plus (Agilent Technologies; Santa Clara, CA), a Bruker micrOTOF liquid chromatograph (Bruker Daltonik GmbH; Bremen, Germany), and a Waters QToF Premier (Waters Corp.; Milford, MA), all interfaced with reverse-phase high-pressure liquid chromatography (C18 column; Phenomenex Inc., Torrance, CA). Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization analysis was performed with a variety of sample/matrix ratios and both sinapinic acid and α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid by use of a Bruker BiFlex III. Identification of protein bands involved in-gel protease digestion followed by mass analysis as described above. A detailed protocol for in-gel proteolysis has been previously described (25).

Spectrofluorometric analysis of capsid stability and conformation.

Empty or full capsids were concentrated to 0.5 μM in Millipore Amicon Ultra 100-kDa cutoff filters (Millipore, Billerica, MA) in 50 mM PIPES-NaOH (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl. Assays were carried out using a Cary Eclipse spectrofluorometer (Varian, Palo Alto, CA) with a 1-cm path length. To analyze Trp fluorescence, samples were excited at 295 nm and emissions scanned from 310 to 400 nm or kept fixed at 331 nm (Ex/Em bandwidth, 5 nm). Capsids were monitored at temperatures between 20 and 77°C. Capsids were also monitored by incubating with 3 μM bis-1-anilino-8-naphthalene sulfonate (bis-ANS) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) under various conditions. Samples were excited at 395 nm (bandwidth, 5 nm) and the emissions read at 500 nm (bandwidth, 10 nm), and bis-ANS with no added protein was used as a background. The effect of low pH on virus capsids was examined by titrating the sample pH with 0.1 N HCl. The effects of ligand binding on capsid structure were determined using purified feline or canine TfR (at a molar ratio of 30 TfR dimers per capsid) or antibody Fabs (at a molar ratio of 60 molecules per capsid). Capsids or purified TfRs and Fabs were also assayed for bis-ANS binding individually.

Exposure of viral DNA.

Accessibility of capsid DNA was assayed using the dye TOTO-1 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Capsids (8.4 μg/ml) in buffers of various pHs were heated at temperatures of up to 95°C for 10 min and cooled to room temperature, and then TOTO-1 was added and the samples were excited at 515 nm (5-nm bandwidth) and read at 532 nm (10-nm bandwidth). To verify DNA exposure, capsids heated to the indicated temperatures were cooled and then digested with 84 units of micrococcal nuclease for 30 min at 37°C and stained for DNA as described above.

TEM.

Accessibilities of different metal salts to the interiors of full and empty capsids were examined before and after heating to various temperatures of up to 75°C or after EGTA treatment at up to 50 mM. For most experiments, capsids were absorbed to carbon-coated transmission electron microscopy (TEM) grids (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for 5 min. After excess sample had been removed, stains were added for 5 min and then blotted off. Stains used were 2% (wt/vol) methyl amine tungstate (NanoW) in water (pH 6.8) and 1% (wt/vol) NiSO4 in water (pH 7.0). In most cases, 0.1% bacitracin was added to give an even distribution on the grids. Samples were visualized at a magnification of ×60,000 in an FEI Tecnai 12 Biotwin microscope. Ten randomly selected fields were photographed (>400 particles each treatment), and the percentages of capsids penetrated by the stains determined.

RESULTS

Protein composition and infectivity of purified capsids.

Infectivity per genome was compared for viruses purified by standard PEG 8000 precipitation and sucrose gradient centrifugation or by iodixanol and glycerol gradients or viruses in freshly prepared cell culture supernatants. The infectivity of fresh capsids (1:1.3 × 10−5 TCID50/genome copy) was similar to those of capsids purified using either PEG 8000 and sucrose (1:1.6 × 10−5 TCID50/genome copy) or iodixanol and glycerol (1:1 × 10−5 TCID50/genome copy). This demonstrates that although the viruses all had low infectivities in these cells, those were not altered during the purification methods used.

SDS-PAGE electrophoresis of all purified capsids examined showed the expected composition of VP1 and VP2 (and VP3 in full capsids), as well as small amounts of previously unrecognized 70-kDa, 36.5-kDa, and 33-kDa proteins (Fig. 1 and 2). The latter proteins were each present at ∼2 to 3% of the VP2 protein concentration but were incorporated into the capsids, as they were not susceptible to proteolysis until significant VP2 degradation had occurred (Fig. 1 and 2A). Western blotting and mass spectrometry indicated that these protein fragments were related to VP1 and VP2 (Fig. 2B and C) and also showed that the 37-kDa peptide (labeled B) contained the C-terminal portion of VP2, while the 33-kDa peptide (labeled C) contained the VP2 N-terminal sequence (Fig. 2). The two peptides represent a VP2 molecule incorporated into the capsid that has been hydrolyzed at one position and is between residues 270 and 292. Residue 270 is exposed on the interior wall of the capsid, and most of the residues between that position and residue 292 are buried within the capsid, while residue 292 is exposed on the capsid surface. No additional cleavages at similar positions appeared to be made by any of the proteases tested. In full capsids, this new N-terminal fragment was split into 50% of a 33-kDa form and 50% of a 29-kDa form, indicating an N-terminal cleavage similar to that of VP3, even though those capsid preparations otherwise contained little VP3 (data not shown). The 70-kDa polypeptide has not yet been completely characterized but may be a truncated form of VP1, as it reacted with antibodies binding VP2 (Fig. 2C).

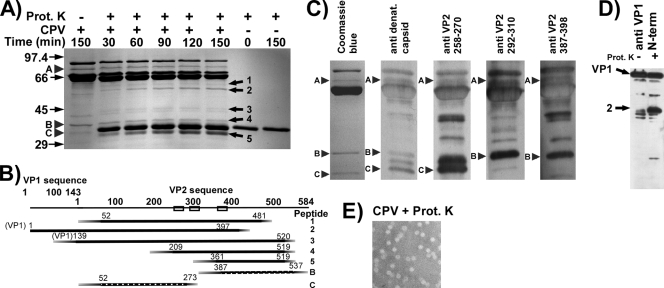

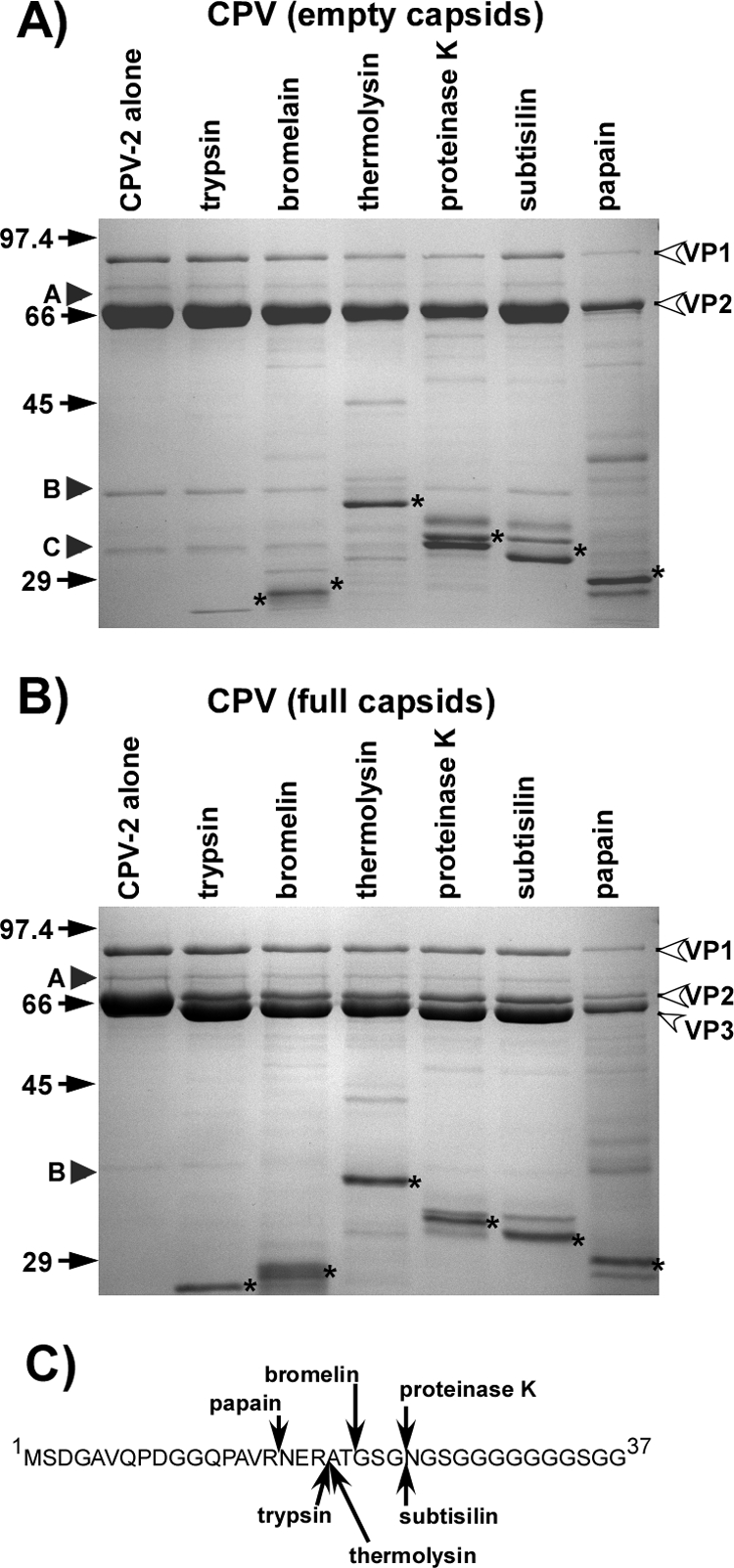

FIG. 1.

(A) Sensitivity of the CPV-2 empty capsids to digestion with the proteases listed. Capsids and protease were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. Size standards are in kDa. VP1, VP2, and VP3 are labeled. Protease bands are indicated by stars. Arrowheads labeled A, B, and C indicate the preexisting submolar bands detected in the purified capsids. (B) Full capsids were treated as for panel A. (C) Cleavage sites in VP2 by the different proteases in the VP2-to-VP3 conversion. Cleavage sites were determined by N-terminal sequencing or mass spectrometry of the resulting VP3. For thermolysin, the major site detected is shown; another unidentified site was also present in lower amounts.

FIG. 2.

(A) Protein composition of CPV-2 full capsids after incubation with 76 μg/ml of proteinase K at 37°C for up to 2 h. Controls included full capsids incubated alone and proteinase K immediately after thawing or incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Arrowheads labeled A, B, and C indicate the preexisting submolar fragments detected in the purified capsids. New peptides generated by the protease treatment are indicated by solid arrows and are numbered. (B) Approximate mapping of the preexisting peptides A, B, and C as well as those released by proteinase K treatment (numbers refer to bands marked in panel A). Peptides were identified by Western blotting with antipeptide sera or by mass spectrometry after trypsin digestion of the recovered protein band. Precise cleavage sites have not yet been determined. Boxes indicate the specific sequences recognized by antipeptide antisera. (C) Peptide analysis of preexisting submolar peptides of full capsids of CPV-2. One lane of untreated full capsids was Coomassie blue stained. Capsid proteins were transferred and probed with anticapsid or antipeptide serum as indicated. Antipeptide antisera were made against peptides containing the VP-2 residues indicated. (D) Western blotting for the VP-1 N-terminal peptide (residues 2 to 13) in full capsids either before or after incubation with proteinase K for 2 h at 37°C. The arrow labeled 2 indicates the submolar fragment that is identified as fragment 2 in panel B. (E) Capsids that were treated for 2 h with proteinase K examined in the electron microscope after staining with NanoW.

Screening of capsid stability by proteolytic cleavage.

All proteolytic enzymes tested converted most VP2 in full (but not empty) capsids into VP3 forms (57) (Fig. 1B). The exact site of cleavage was slightly different for each of the proteases, and these were partially mapped using N-terminal sequencing of the newly generated VP3 fragment (Fig. 1C). Although proteases were present in large amounts (Fig. 1 and 2), there was generally little degradation of the capsids during 2 h of incubation at 37°C (Fig. 1), and the proteolytic fragments generated represented only a small percentage of the total capsid protein. Proteinase K was selected for more-detailed studies due to its broad specificity and activity under the experimental conditions used. Incubating CPV-2 virions for various times with proteinase K at 37°C in a pH of 7.6 gave a limited number of digestion products (Fig. 2A). Examining digested capsids by negative staining EM indicated that they were largely intact and that the full particles excluded the NanoW stain (Fig. 2E). After size exclusion chromatography, the cleaved fragments remained incorporated in the capsid (results not shown). Western blotting using specific peptide antibodies and mass spectrometric analysis of trypsin-digested protein bands allowed some of the proteolytic fragments to be positioned within the VP1 or VP2 sequences (Fig. 2B to D).

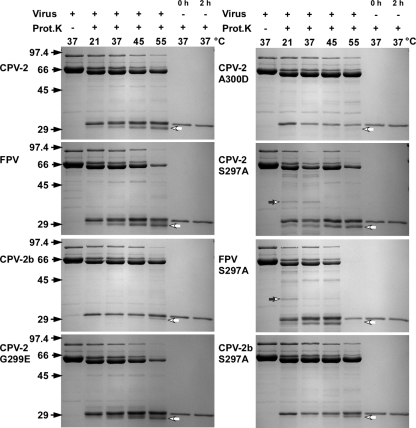

Effects of temperature on capsid structure.

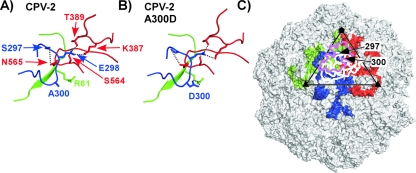

Proteinase K treatment of the various capsids at higher temperatures demonstrated an increase in the total amount of digestion products but in most cases no additional peptide fragments (Fig. 3). FPV and CPV-2b capsids were more sensitive than CPV-2 capsids to digestion at 45 and 55°C (Fig. 3). CPV-2 and FPV capsids with VP2 residue 297 changed from Ser to Ala showed an additional peptide of 40 kDa, which was not seen in the wild-type forms of those virus capsids or when the mutation was in the CPV-2b background (Fig. 3). Changing CPV-2 VP2 residue 299 (Gly to Glu) or 300 (Ala to Asp) alters the canine TfR binding, canine host range, and antigenic structure of the capsid (17, 19, 23, 34), and the 300 Asp variant of CPV-2 showed a loss of a peptide of 23 kDa that fell just below the proteinase K band (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Susceptibilities of full capsids of CPV-2, FPV, and CPV-2a or mutants of those viruses to proteinase K for 2 h at the temperatures indicated. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue. Size standards are in kDa. Controls include virus incubated without proteinase, fresh proteinase K, or enzyme incubated for 2 h or 37°C. Additional bands seen in the CPV-2 S297A and FPV S297A samples, or those that differ between CPV-2 and CPV-2 A300D, are indicated by open arrows.

All of the viruses examined here contain 14 Trp residues in VP2 which are sequestered mostly within the capsid structure (29, 59). Tryptophan fluorescence spectra of full and empty CPV-2 particles under physiological conditions were indistinguishable at 22°C (Fig. 4A and B). As the temperature was increased, the emission intensity decreased linearly, as expected from the thermal quenching of fluorescence (3). At 68 to 70°C, there was an increase and change in the emission maximum wavelengths for both empty and full capsid particles, indicating that Trp residues were exposed during particle disintegration (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Trp fluorescence spectra of CPV-2 empty (A) and full (B) capsids at various temperatures, excited at 295 nm with emission scanned between 310 and 400 nm. (C) Trp fluorescence of full and empty CPV-2 particles as temperatures were raised at 0.5°C/min, monitoring emission fluorescence at 331 nm. Data are means of three independent experiments ± 1 standard deviation (SD). (D) Fluorescence of bis-ANS incubated with CPV-2 full or empty capsids at various temperatures. Samples were excited at 395 and the emission was read at 500 nm as temperatures were raised at 0.5°C/min. Data are means of three independent experiments ± 1 SD. a.u., arbitrary units.

For CPV-2 capsids incubated with bis-ANS, empty capsids displayed a slight increase in binding between 25 and 35°C and then a significant decrease between 35 and 55°C. These changes were not observed for full capsids. Above 68°C there was a dramatic increase of bin-ANS binding to both full and empty capsids as they disintegrated (Fig. 4D). The observed change between 20 and 55°C for empty capsids was attributed to capsid structural changes, as no change of bis-ANS binding to the bovine serum albumin (BSA) control occurred over that temperature range (data not shown).

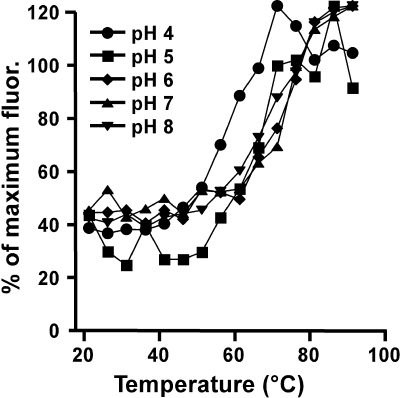

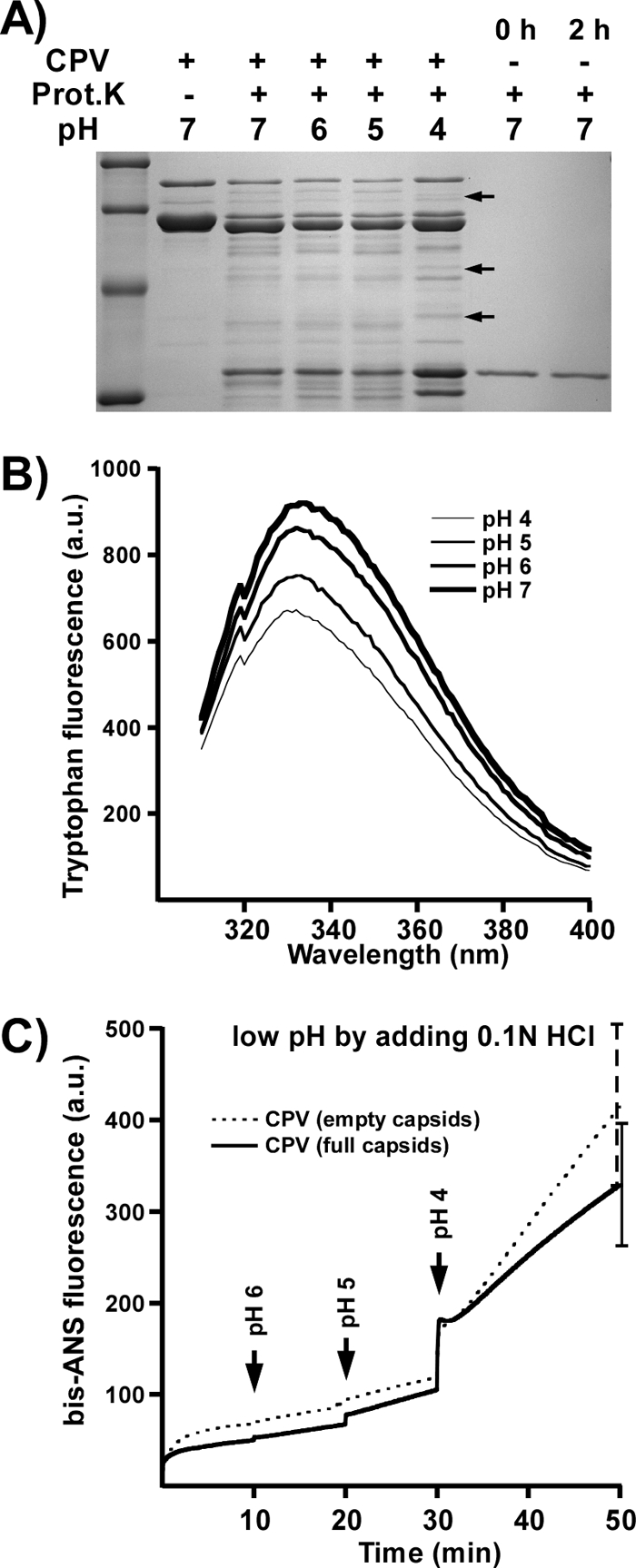

Effects of pH or EGTA treatment on virus structure.

CPV-2 capsids were incubated with proteinase K at 37°C for 2 h in pH 7, 6, 5, and 4 buffers. No significant differences in either protease susceptibility or proteolytic peptide patterns were seen between pHs 7.5 and 5.0; however, some alternative cleavages occurred at pH 4 (Fig. 5A). Trp fluorescence spectroscopy showed no changes in the spectra at any of the pHs tested (Fig. 5B), although the intensity progressively decreased over the pH range. This indicates that there is no major change in the structure but that minor changes, such as a relaxation of the capsid structure, likely occurred. Binding of bis-ANS increased at pH 4.0 (Fig. 5C). The protein binding properties of bis-ANS itself is generally believed to be pH insensitive (13, 46), although increased binding to positively charged groups can occur at lower pH (22). The bis-ANS binding to BSA increased slightly at lower pH (data not shown), but the effect was considerably less than seen for CPV capsids, indicating that the increased fluorescence from bis-ANS at lower pH resulted from structural changes to the virus.

FIG. 5.

(A) Protein composition of CPV-2 capsids incubated with proteinase K for 2 h in the pH buffers indicated. Controls include proteinase K (Prot.K) incubated alone for 0 or 2 h and capsids incubated without proteinase K. Arrows indicate new peptides at pH 4.0. (B) Trp fluorescence of CPV-2 full capsids at the pHs indicated. (C) bis-ANS fluorescence of full or empty capsids at various pHs. The dye was added to capsids in the cuvette and the pH adjusted by the addition of 0.1 N HCl. Data are means of three independent experiments ± 1 SD. a.u., arbitrary units.

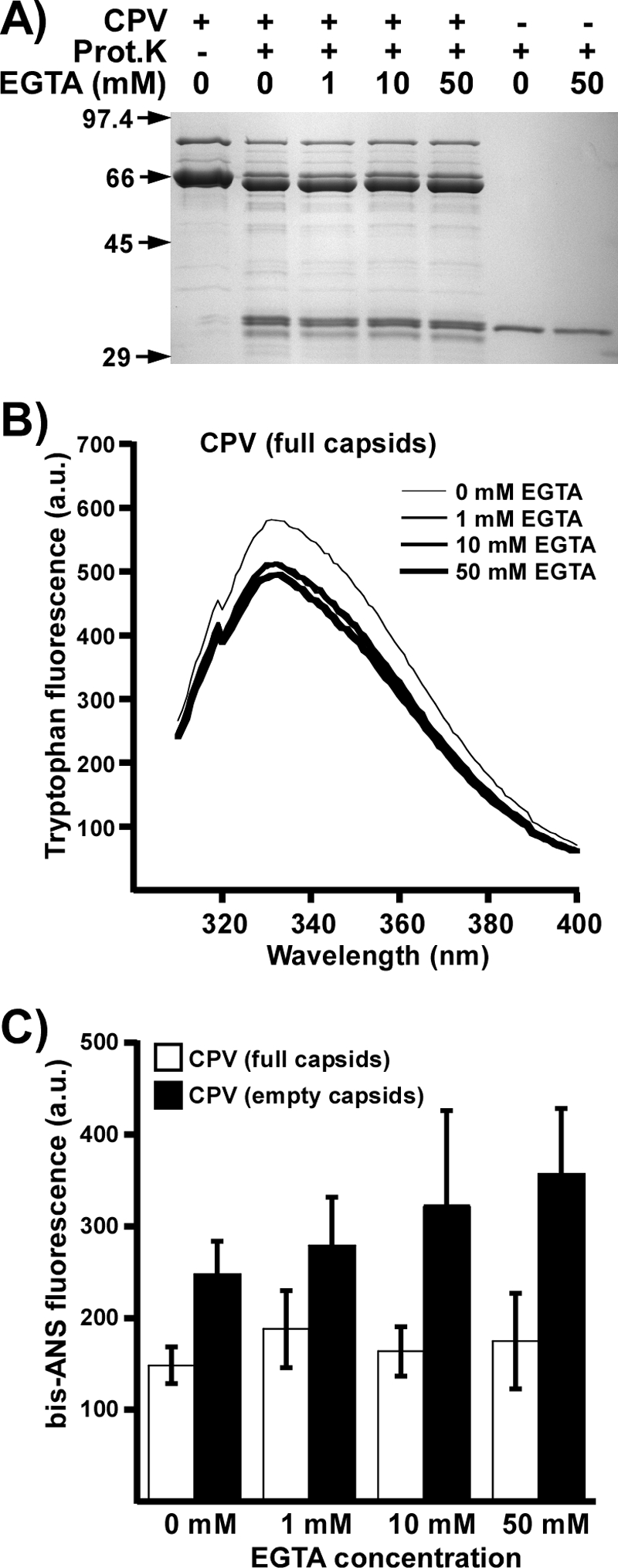

Proteinase K treatment of CPV-2 capsids incubated with 0, 1, 10, or 50 mM EGTA showed no changes in the digestion levels or peptide patterns (Fig. 6A) or in the emission wavelength of the Trp fluorescence spectra (Fig. 6B). Trp fluorescence intensity decreased slightly after initial EGTA treatment, indicating small changes in the local environment of some Trp residues. Binding of bis-ANS to empty capsids gave an increase in intensity at higher concentrations of EGTA that was not seen for full capsids (Fig. 6C). Control binding to BSA did not change under those conditions (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

(A) CPV-2 full capsids incubated with proteinase K in the presence of various concentrations of EGTA. Controls include capsids incubated with neither protease or EGTA or protease incubated with 0 or 50 mM of EGTA. Prot.K, proteinase K. (B) Trp fluorescence of full capsids in the presence of various amounts of EGTA. (C) Relative bis-ANS fluorescences of CPV full and empty capsids incubated with various amounts of EGTA ± 1 SD. a.u., arbitrary units.

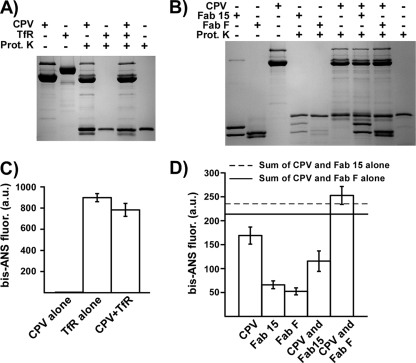

Effects of ligand binding on capsid structure.

Incubating full CPV-2 capsids with Fab F or 15 or purified feline TfR ectodomain did not change the virus susceptibility to proteinase K (Fig. 7A and B). TfR itself bound very high levels of bis-ANS compared to the binding level seen for capsids, and adding bis-ANS to mixtures of CPV-2 capsids and TfR resulted in a slight decrease in bis-ANS fluorescence (Fig. 7C). Fab 15 and Fab F bound levels of bis-ANS similar to those seen for CPV, and adding the dye to preincubated Fab 15 and CPV resulted in a decrease in bis-ANS fluorescence compared to what was seen for CPV and Fab 15 alone (Fig. 7D). Binding of bis-ANS to CPV and Fab F gave a slight increase in fluorescence compared to the binding to CPV or Fab F individually, suggesting a small change in the structure of one of the components upon ligand binding (Fig. 7D).

FIG. 7.

The effects of the feline TfR ectodomain or antibody Fabs on the CPV-2 full virus capsid structure. (A) CPV-2 full capsids incubated with the purified feline TfR ectodomain, with or without proteinase K (Prot.K) treatment. The SDS-PAGE gel was stained with Coomassie blue. (B) Same as for panel A, but capsids were incubated with Fabs of MAb 15 or 8. (C) Binding of bis-ANS to full CPV-2 capsids alone, to the feline TfR alone, or to a mixture of the two. Results are means from three separate experiments ± 1 SD. (D) Binding of bis-ANS to full CPV-2 capsids alone, to Fab F or Fab 15 alone, or to capsid-Fab mixtures. The fluorescent results for panels C and D cannot be compared directly, as the TfR ectodomain bound the dye to much higher levels than the Fabs, so that the photomultiplier was at different settings for each experiment. a.u., arbitrary units.

Exposure of viral DNA upon heating.

The viral DNA in full CPV-2 capsids became accessible to TOTO-1 dye starting at ∼50°C, and exposure increased up to 65°C and showed a large increase around 70°C (Fig. 8). No significant effect of low pH was seen on DNA exposure in that assay. Digestion of heated particles with micrococcal nuclease reduced the DNA signal, indicating the occurrence of DNA externalization, as opposed to the entrance of dye into the capsids (data not shown).

FIG. 8.

Staining of the DNA of CPV-2 full capsids with TOTO-1 after heating at various pHs. Capsids were heated for 10 min and cooled to 21°C, dye was added, and the fluorescence (fluor.) was determined. There was no statistically significant difference between the exposures of the DNA at any of the pHs tested.

TEM and stain penetration.

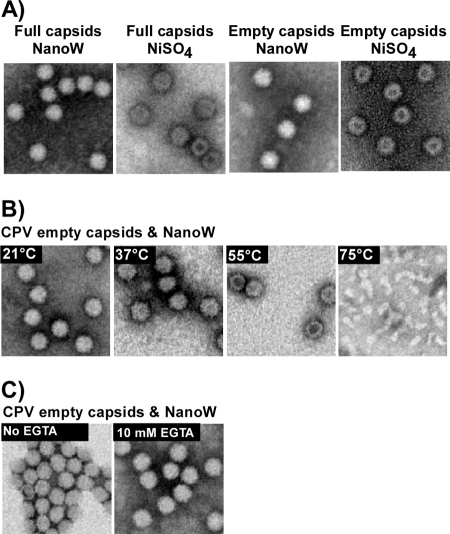

The permeability of the capsids was examined using NanoW and NiSO4. At 21°C NiSO4 readily entered empty capsids, while NanoW was largely excluded (Fig. 9). When NanoW was incubated with heat-treated empty CPV capsids, penetration increased from 12% at 21°C to 39% at 37°C and to 79% at 55°C, while at 75°C the particles disassembled. EGTA treatment did not change the staining of empty capsids by NanoW (Fig. 9C).

FIG. 9.

(A) Negative staining of CPV-2 full or empty capsids (as indicated) with NiSO4 or NanoW. (B) Negative staining of CPV-2 empty capsids with NanoW after heating to various temperatures for 10 min. (C) Negative staining of CPV-2 empty capsids with NanoW in the presence or absence of 10 mM EGTA.

DISCUSSION

This study confirmed that the CPV capsid is very stable and showed that subtle changes occur in overall capsid structure, dynamics, and permeability. Some changes appeared to be localized with respect to capsid architecture and may involve only a subset of capsid subunits. The capsid responses to increased temperatures provided evidence of coordinated changes in the capsid, in particular by higher DNA exposure of full capsids and by reduced bis-ANS binding and increased NanoW penetration of empty capsids. However, proteinase K treatments showed only small increases in overall capsid sensitivity, although a higher proportion of VP2 was cleaved to VP3 in full capsids, likely due to more ready transport of the VP2 N termini to the outside of the capsid through the fivefold pore.

The full and empty capsid stabilities appeared to be indistinguishable by Trp fluorescence, despite the known interactions of the DNA with the interior of the full capsid (59). The 14 Trp residues in the VP1/VP2 common region are mostly buried within the structure and therefore would report changes that were predominantly to the overall capsid conformation (29). Studies of VP2-only MVM virus-like particles showed changes in Trp emission intensity when heated between 40 and 55°C (7), but those could not be detected in our studies. This could therefore reflect structural differences between the capsids of MVM and CPV or between the VP2-only capsids examined in that study and the VP1/VP2 CPV particles examined here. bis-ANS binds to exposed hydrophobic regions of the capsid and can indicate structural changes (46). Our results show a clear difference in bis-ANS binding between the empty and full capsids, and those could reflect the differences in stability reported for full and empty MVM capsids (6) or the fact that the stain may have entered the empty but not full capsids. The full and empty capsids did, however, disintegrate at the same temperature.

VP2 cleavage to VP3, as well as low-pH treatment, has been reported to alter exposure of the VP1 N terminus in MVM (11, 26, 44). Here we saw little effect of lower pH on the CPV structure, with the main change in proteinase K cleavages only at pH 4.0, while viral DNA exposure to TOTO-1 was not affected by low pH. It was previously shown using X-ray crystallography that at pH 6.2 or 5.5 there was reduced Ca2+ bound and small changes in the arrangements of surface loops of the capsids (45).

Triggers activating capsids or envelope proteins of other viruses for infection include exposure to low pH, removal of bound ions, and/or protease digestion (27, 47). In studies of adeno-associated virus capsids or those of other viruses, uniform cleavages of the capsid protein(s) were seen after trypsin treatment (54). The CPV-related viruses replicate in the lymphoid tissues and in the small intestinal epithelial cells, and viruses are shed in the feces of infected animals. Thus, the virus must resist digestive proteases and proteolytic enzymes produced by the intestinal flora. For CPV and FPV, even broad-specificity proteases cleaved only a small proportion of the capsid subunits at select positions. The structures of CPV-2 and FPV differ in the inter- or intrachain bonds of VP2 residues 93 and 323 (15) and in the numbers of bound Ca2+ ions (120 or 180, depending on the virus) (45). The CPV-2a/b capsids also vary from CPV-2 at VP2 residues 87, 101, 300, and 305 but showed no differences in the peptides generated after proteinase K digestion.

The Ser-to-Ala change of VP2 residue 297 which emerged in the CPV-2a/b-derived virus background after 1990 (36) gave an additional submolar fragment when present in CPV-2 and FPV capsids but not when present in CPV-2b (Fig. 3 and 10). Several capsid protein changes near residue 297 affect binding to the canine TfR and to some antibodies. The changes involved include Gly300, which likely increases the flexibility of the loop, and Asp300 (in CPV-2a), which would reduce its flexibility through the formation of new hydrogen bonds in the structure (Fig. 10A and B). These differences in the loop and surrounding structures were likely reflected in the loss of the 23-kDa peptide in the 300 Asp mutant (19, 23, 34). A consequence of this cleavage of the surface loop of the capsid would be that the particles would now contain a small number of positions with a different surface structure and charge. That cleavage is within the footprint of many antibody binding sites and closely adjacent to the TfR binding site on the capsid (Fig. 10C).

FIG. 10.

The position of one of the protease cleavage sites in the structure of the capsid and the protein or capsid relationships to the known antibody and receptor binding sites. (A and B) Comparison of the structures of 300Ala (A), found in CPV-2, and the 300Asp variant (B), showing the differences in the bonding and the likely flexibility of the loops involved. Residue 297 is shown as a Ser, and when this is changed to an Ala in FPV or CPV-2 an additional submolar cleavage can occur (Fig. 3). The four loops shown are those that make up the region of the capsid surface around VP2 residue 300. The three colors indicate the three different VP2 molecules involved, and numbers indicate the VP2 residues involved in hydrogen bonding in this region. The submolar cleavage of the loop around residue 300 is controlled by the presence of Ala300 in CPV-2, which allows cleavage, while 300Asp is not cleaved. (C) The location of the VP2 residues 297 and 300 on the capsid surface relative to known TfR and antibody binding sites. The three VP2 molecules that surround the cleavage site are colored. The triangle indicates one asymmetric unit of the viral capsid. The binding footprints of three different antibodies (white lines) or of the feline TfR (magenta) on the capsid surface are shown to indicate the relationship of the cleaved loop to the binding sites of those ligands.

We have shown that feline TfR bound to only a small number of sites on the CPV-2 capsid (16). Possible explanations include the intrinsic asymmetry of capsid sites controlling TfR binding and changes in capsid morphology induced after TfR binding that prevent the attachment of additional TfRs. In these studies, no changes were seen in the capsid structure after TfR binding. Sources of preexisting asymmetry in full capsids could include the exposed 5′ end of the viral DNA, various numbers of exposed VP2 or VP3 N termini, and the five or six copies of VP1. Here we show that purified full and empty capsids also incorporate about one to three copies per virion of a 70-kDa capsid protein variant, likely a shorter form of VP1, and a VP2 cleaved at a single site. The 70-kDa protein may represent a minor capsid protein form, perhaps similar to the VP2 protein of the adeno-associated viruses or to the intermediately sized minor capsid proteins of bovine parvovirus and minute virus of canines (42, 51). Another source of asymmetry would also be the introduction of cleavages of loops within the capsid surface through specific protease cleavage, and in many cases those could interfere with the binding of either receptor or antibodies, or of both ligands (Fig. 10).

These results show that the capsid of the parvoviruses undergoes subtle changes upon heating which are associated with the permeability of the capsids but which do not dramatically alter the structure, and this was particularly true for the infectious DNA-containing capsids. More physiological treatments such as low pH, removal of Ca2+, or binding of receptors or antibodies showed few changes in our assays, suggesting that those may act as triggers but that dramatic changes are not likely to be present. This emphasizes the likely role of changes in permeability that release internal components such as the viral DNA and the N terminus of VP1. The presence of such exposed components and also of the very-low-copy-number protein forms also suggests new sources of asymmetry which may be involved in the functions of the capsids, and we will examine these effects in our future studies.

Acknowledgments

We thank Virginia Scarpino and Wendy S. Weichert for excellent technical assistance.

This work was supported by grant AI33468 from the National Institutes of Health to C.R.P.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 13 August 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agbandje, M., R. McKenna, M. G. Rossmann, M. L. Strassheim, and C. R. Parrish. 1993. Structure determination of feline panleukopenia virus empty particles. Proteins 16155-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agbandje-McKenna, M., A. L. Llamas-Saiz, F. Wang, P. Tattersall, and M. G. Rossmann. 1998. Functional implications of the structure of the murine parvovirus, minute virus of mice. Structure 61369-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albani, J. R. 2004. Structure and dynamics of macromolecules: absorption and fluorescence studies. Elsevier, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- 4.Buonavoglia, C., V. Martella, A. Pratelli, M. Tempesta, A. Cavalli, D. Buonavoglia, G. Bozzo, G. Elia, N. Decaro, and L. Carmichael. 2001. Evidence for evolution of canine parvovirus type 2 in Italy. J. Gen. Virol. 823021-3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carey, J. 2000. A systematic and general proteolytic method for defining structural and functional domains of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 328499-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carrasco, C., A. Carreira, I. A. Schaap, P. A. Serena, J. Gomez-Herrero, M. G. Mateu, and P. J. de Pablo. 2006. DNA-mediated anisotropic mechanical reinforcement of a virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10313706-13711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carreira, A., M. Menendez, J. Reguera, J. M. Almendral, and M. G. Mateu. 2004. In vitro disassembly of a parvovirus capsid and effect on capsid stability of heterologous peptide insertions in surface loops. J. Biol. Chem. 2796517-6525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chapman, M. S., and M. G. Rossmann. 1995. Single-stranded DNA-protein interactions in canine parvovirus. Structure 3151-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cotmore, S. F., A. M. D'Abramo, Jr., C. M. Ticknor, and P. Tattersall. 1999. Controlled conformational transitions in the MVM virion expose the VP1 N-terminus and viral genome without particle disassembly. Virology 254169-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotmore, S. F., and P. Tattersall. 1989. A genome-linked copy of the NS-1 polypeptide is located on the outside of infectious parvovirus particles. J. Virol. 633902-3911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Farr, G. A., S. F. Cotmore, and P. Tattersall. 2006. VP2 cleavage and the leucine ring at the base of the fivefold cylinder control pH-dependent externalization of both the VP1 N terminus and the genome of minute virus of mice. J. Virol. 80161-171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farr, G. A., L. G. Zhang, and P. Tattersall. 2005. Parvoviral virions deploy a capsid-tethered lipolytic enzyme to breach the endosomal membrane during cell entry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10217148-17153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flanagan, M. T., and S. Ainsworth. 1968. The binding of aromatic sulphonic acids to bovine serum albumin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 16816-26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gordon, J. C., and E. J. Angrick. 1986. Canine parvovirus: environmental effects on infectivity. Am. J. Vet. Res. 471464-1467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Govindasamy, L., K. Hueffer, C. R. Parrish, and M. Agbandje-McKenna. 2003. Structures of host range-controlling regions of the capsids of canine and feline parvoviruses and mutants. J. Virol. 7712211-12221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafenstein, S., L. M. Palermo, V. A. Kostyuchenko, C. Xiao, M. C. Morais, C. D. Nelson, V. D. Bowman, A. J. Battisti, P. R. Chipman, C. R. Parrish, and M. G. Rossmann. 2007. Asymmetric binding of transferrin receptor to parvovirus capsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1046585-6589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hueffer, K., L. Govindasamy, M. Agbandje-McKenna, and C. R. Parrish. 2003. Combinations of two capsid regions controlling canine host range determine canine transferrin receptor binding by canine and feline parvoviruses. J. Virol. 7710099-10105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hueffer, K., L. M. Palermo, and C. R. Parrish. 2004. Parvovirus infection of cells by using variants of the feline transferrin receptor altering clathrin-mediated endocytosis, membrane domain localization, and capsid-binding domains. J. Virol. 785601-5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hueffer, K., J. S. Parker, W. S. Weichert, R. E. Geisel, J. Y. Sgro, and C. R. Parrish. 2003. The natural host range shift and subsequent evolution of canine parvovirus resulted from virus-specific binding to the canine transferrin receptor. J. Virol. 771718-1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hueffer, K., and C. R. Parrish. 2003. Parvovirus host range, cell tropism and evolution. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 6392-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson, J. E. 2003. Virus particle dynamics. Adv. Protein Chem. 64197-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Korte, T., and A. Herrmann. 1994. pH-dependent binding of the fluorophore bis-ANS to influenza virus reflects the conformational change of hemagglutinin. Eur. Biophys. J. 23105-113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Llamas-Saiz, A. L., M. Agbandje-McKenna, J. S. L. Parker, A. T. M. Wahid, C. R. Parrish, and M. G. Rossmann. 1996. Structural analysis of a mutation in canine parvovirus which controls antigenicity and host range. Virology 22565-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Llamas-Saiz, A. L., M. Agbandje-McKenna, W. R. Wikoff, J. Bratton, P. Tattersall, and M. G. Rossman. 1997. Structure determination of minute virus of mice. Acta Crystallogr. D 5393-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maaty, W. S., A. C. Ortmann, M. Dlakic, K. Schulstad, J. K. Hilmer, L. Liepold, B. Weidenheft, R. Khayat, T. Douglas, M. J. Young, and B. Bothner. 2006. Characterization of the archaeal thermophile Sulfolobus turreted icosahedral virus validates an evolutionary link among double-stranded DNA viruses from all domains of life. J. Virol. 807625-7635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mani, B., C. Baltzer, N. Valle, J. M. Almendral, C. Kempf, and C. Ros. 2006. Low pH-dependent endosomal processing of the incoming parvovirus minute virus of mice virion leads to externalization of the VP1 N-terminal sequence (N-VP1), N-VP2 cleavage, and uncoating of the full-length genome. J. Virol. 801015-1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Marsh, M., and A. Helenius. 2006. Virus entry: open sesame. Cell 124729-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson, C. D., L. M. Palermo, S. L. Hafenstein, and C. R. Parrish. 2007. Different mechanisms of antibody-mediated neutralization of parvoviruses revealed using the Fab fragments of monoclonal antibodies. Virology 361283-293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pakkanen, K., J. Karttunen, S. Virtanen, and M. Vuento. 2008. Sphingomyelin induces structural alteration in canine parvovirus capsid. Virus Res. 132187-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Palermo, L. M., S. L. Hafenstein, and C. R. Parrish. 2006. Purified feline and canine transferrin receptors reveal complex interactions with the capsids of canine and feline parvoviruses that correspond to their host ranges. J. Virol. 808482-8492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paradiso, P. R. 1983. Analysis of the protein-protein interactions in the parvovirus H-1 capsid. J. Virol. 4694-102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paradiso, P. R., S. L. I. Rhode, and I. I. Singer. 1982. Canine parvovirus: a biochemical and ultrastructural characterization. J. Gen. Virol. 62113-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parker, J. S. L., W. J. Murphy, D. Wang, S. J. O'Brien, and C. R. Parrish. 2001. Canine and feline parvoviruses can use human or feline transferrin receptors to bind, enter, and infect cells. J. Virol. 753896-3902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Parker, J. S. L., and C. R. Parrish. 1997. Canine parvovirus host range is determined by the specific conformation of an additional region of the capsid. J. Virol. 719214-9222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parrish, C. R. 1991. Mapping specific functions in the capsid structure of canine parvovirus and feline panleukopenia virus using infectious plasmid clones. Virology 183195-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parrish, C. R., C. Aquadro, M. L. Strassheim, J. F. Evermann, J.-Y. Sgro, and H. Mohammed. 1991. Rapid antigenic-type replacement and DNA sequence evolution of canine parvovirus. J. Virol. 656544-6552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parrish, C. R., C. F. Aquadro, and L. E. Carmichael. 1988. Canine host range and a specific epitope map along with variant sequences in the capsid protein gene of canine parvovirus and related feline, mink and raccoon parvoviruses. Virology 166293-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Parrish, C. R., and L. E. Carmichael. 1983. Antigenic structure and variation of canine parvovirus type-2, feline panleukopenia virus, and mink enteritis virus. Virology 129401-414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Parrish, C. R., L. E. Carmichael, and D. F. Antczak. 1982. Antigenic relationships between canine parvovirus type-2, feline panleukopenia virus and mink enteritis virus using conventional antisera and monoclonal antibodies. Arch. Virol. 72267-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parrish, C. R., and Y. Kawaoka. 2005. The origins of new pandemic viruses: the acquisition of new host ranges by canine parvovirus and influenza A viruses. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 59553-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parrish, C. R., P. H. O'Connell, J. F. Evermann, and L. E. Carmichael. 1985. Natural variation of canine parvovirus. Science 2301046-1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qiu, J., F. Cheng, F. B. Johnson, and D. Pintel. 2007. The transcription profile of the bocavirus bovine parvovirus is unlike those of previously characterized parvoviruses. J. Virol. 8112080-12085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rhode, S. L., III. 1985. Nucleotide sequence of the coat protein gene of canine parvovirus. J. Virol. 54630-633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ros, C., C. Baltzer, B. Mani, and C. Kempf. 2006. Parvovirus uncoating in vitro reveals a mechanism of DNA release without capsid disassembly and striking differences in encapsidated DNA stability. Virology 345137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Simpson, A. A., V. Chandrasekar, B. Hebert, G. M. Sullivan, M. G. Rossmann, and C. R. Parrish. 2000. Host range and variability of calcium binding by surface loops in the capsids of canine and feline parvoviruses. J. Mol. Biol. 300597-610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Slavik, J. 1982. Anilinonaphthalene sulfonate as a probe of membrane composition and function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 6941-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith, A. E., and A. Helenius. 2004. How viruses enter animal cells. Science 304237-242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Steven, A. C., J. B. Heymann, N. Cheng, B. L. Trus, and J. F. Conway. 2005. Virus maturation: dynamics and mechanism of a stabilizing structural transition that leads to infectivity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 15227-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strassheim, L. S., A. Gruenberg, P. Veijalainen, J.-Y. Sgro, and C. R. Parrish. 1994. Two dominant neutralizing antigenic determinants of canine parvovirus are found on the threefold spike of the virus capsid. Virology 198175-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Suikkanen, S., M. Antila, A. Jaatinen, M. Vihinen-Ranta, and M. Vuento. 2003. Release of canine parvovirus from endocytic vesicles. Virology 316267-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trempe, J. P., and B. J. Carter. 1988. Alternate RNA splicing is required for synthesis of adeno-associated virus VP1 capsid protein. J. Virol. 623356-3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Truyen, U., J. F. Evermann, E. Vieler, and C. R. Parrish. 1996. Evolution of canine parvovirus involved loss and gain of feline host range. Virology 215186-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsao, J., M. S. Chapman, M. Agbandje, W. Keller, K. Smith, H. Wu, M. Luo, T. J. Smith, M. G. Rossmann, R. W. Compans, and C. R. Parrish. 1991. The three-dimensional structure of canine parvovirus and its functional implications. Science 2511456-1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Vliet, K., V. Blouin, M. Agbandje-McKenna, and R. O. Snyder. 2006. Proteolytic mapping of the adeno-associated virus capsid. Mol. Ther. 14809-821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vihinen-Ranta, M., L. Kakkola, A. Kalela, P. Vilja, and M. Vuento. 1997. Characterization of a nuclear localization signal of canine parvovirus capsid proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 250389-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vihinen-Ranta, M., D. Wang, W. S. Weichert, and C. R. Parrish. 2002. The VP1 N-terminal sequence of canine parvovirus affects nuclear transport of capsids and efficient cell infection. J. Virol. 761884-1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weichert, W. S., J. S. Parker, A. T. Wahid, S. F. Chang, E. Meier, and C. R. Parrish. 1998. Assaying for structural variation in the parvovirus capsid and its role in infection. Virology 250106-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wikoff, W. R., G. Wang, C. R. Parrish, R. H. Cheng, M. L. Strassheim, T. S. Baker, and M. G. Rossmann. 1994. The structure of a neutralized virus: canine parvovirus complexed with neutralizing antibody fragment. Structure 2595-607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xie, Q., and M. S. Chapman. 1996. Canine parvovirus capsid structure, analyzed at 2.9 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 264497-520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yuan, W., and C. R. Parrish. 2000. Comparison of two single-chain antibodies that neutralize canine parvovirus: analysis of an antibody-combining site and mechanisms of neutralization. Virology 269471-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zadori, Z., J. Szelei, M.-C. Lacoste, P. Raymond, M. Allaire, I. R. Nabi, and P. Tijssen. 2001. A viral phospholipase A2 is required for parvovirus infectivity. Dev. Cell 1291-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]