Abstract

Viperin is identified as an antiviral protein induced by interferon (IFN), viral infections, and pathogen-associated molecules. In this study, we found that viperin is highly induced at the RNA level by Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV) and Sindbis virus (SIN) and that viperin protein is degraded in JEV-infected cells through a proteasome-dependent mechanism. Promoter analysis revealed that SIN induces viperin expression in an IFN-dependent manner but that JEV by itself activates the viperin promoter through IFN regulatory factor-3 and AP-1. The overexpression of viperin significantly decreased the production of SIN, but not of JEV, whereas the proteasome inhibitor MG132 sustained the protein level and antiviral effect of viperin in JEV-infected cells. Knockdown of viperin expression by RNA interference also enhanced the replication of SIN, but not that of JEV. Our results suggest that even though viperin gene expression is highly induced by JEV, it is negatively regulated at the protein level to counteract its antiviral effect. In contrast, SIN induces viperin through the action of IFN, and viperin exhibits potent antiviral activity against SIN.

Viperin, an interferon (IFN)-induced cellular antiviral protein, was identified originally as cig5 in human cytomegalovirus (HCMV)-infected human fibroblasts (53). A similar gene called vig-1 was identified subsequently in viral hemorrhagic septicemia virus-infected rainbow trout leukocytes (3) and in mouse dendritic cells infected with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and pseudorabies virus (4). Viperin was then found to be induced by both type I and type II IFN and to exhibit antiviral activity against HCMV (9). Furthermore, the results of several gene-profiling microarray studies showed that the viperin gene is one of those that is highly induced by a range of different viruses (20, 25, 38, 40, 42, 46) and microbial products, such as lipopolysaccharide (35, 42), the double-stranded RNA analog poly(I-C) (39), and double-stranded B-form DNA (22), in various cell types.

The human viperin gene encodes a protein of 361 amino acids with a predicted molecular mass of 42.2 kDa. Protein sequence analysis reveals a CX3CX2C motif, which is found in the superfamily of S-adenosyl methionine (SAM)-dependent radical enzymes (44) in residues 83 to 90 of human viperin. Thus, viperin is also called radical SAM domain-containing 2 (RSAD2). The radical SAM superfamily comprises more than 600 members (44, 47), and evidence suggests that the three conserved cysteine residues are part of an unusual iron-sulfur cluster that uses SAM as a cofactor to form a radical that is involved in catalysis (19, 27). Although the precise function of viperin remains to be elucidated, recent data have proven its cellular antiviral effects. The overexpression of viperin reduces productive HCMV infection in human fibroblasts by downregulating several structural proteins that are critical for viral assembly and maturation (9), inhibits influenza virus release by perturbing lipid rafts (48), decreases human hepatitis C virus replicon replication in Huh-7 cells (20) and HEK293-derived cells (24), and attenuates Sindbis virus (SIN)-induced virulence in mice (52). Viperin also participates in the poly(I-C)-induced inhibition of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in human astrocytes (39). However, the antiviral mechanisms of viperin are largely unknown.

The regulation of viperin gene expression appears to be complicated, and both IFN-dependent and -independent pathways have been reported (4, 39, 42). The induction of IFNs during viral infection is mediated by the coordinated activation of multiple cellular transcription factors, such as IFN regulatory factor-3 (IRF-3), NF-κB, and c-Jun/ATF-2 (2). IFN signaling is mediated by the Jak-Stat pathway, which triggers ISGF3 complex formation with phosphorylated Stat1, Stat2, and IRF-9. The nuclear translocation of ISGF3 results in binding to the IFN-stimulated responsive element (ISRE) and the consequent expression of IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs), including those encoding several antiviral proteins. However, it is also known that the ISRE sites on some of the ISG promoters are induced not only by ISGF3 but also IRF-3 (17, 34), and the activation of IRF-3 has been shown to be sufficient to induce viperin gene expression (17). Viruses seem to induce viperin expression either directly or through the induction of IFN. In a dendritic-cell line, VSV directly induces viperin expression because treatment with anti-IFN antibody has no effect on its viperin induction; however, anti-IFN antibody blocks viperin induction by pseudorabies virus (4). Viperin gene expression induced by Sendai virus is also dependent on IFN signaling, because viperin induction does not occur in bone marrow macrophages derived from alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) receptor-deficient mice (42). The results of promoter studies combined with DNA immunoprecipitation data show that Sendai virus-mediated viperin gene expression is tightly regulated by the ISGF3 complex and negatively regulated by BLIMP1 (42). Lipopolysaccharide and poly(I-C) also induce viperin expression through an IFN-mediated pathway (39, 42). Thus, it is likely that viruses and IFN induce viperin through different mechanisms, but the detailed molecular mechanisms are still unclear.

Several important issues regarding viperin remain unanswered, such as how viperin inhibits viral production and how viruses evade the antiviral effects of viperin. In this study, we explored the ability of viperin to function as an antiviral molecule against two viruses, Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), a flavivirus, and SIN, an alphavirus. We also studied the molecular mechanisms of viperin promoter activation by JEV and SIN, as well as the mechanism adapted by JEV to downregulate the antiviral activity of viperin.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and reagents.

A549 cells, an IFN-responsive human lung carcinoma cell line; Vero cells, a green monkey kidney cell line; BHK-21 cells, a baby hamster kidney cell line; and HTB-11, a human neuroblastoma cell line, were cultured as described previously (6). HeLa, a human cervical carcinoma cell line, was cultured in minimal essential medium (Gibco) with 10% fetal bovine serum and 2 mM l-glutamine. Puromycin, MG132, SP600125, tunicamycin, LY294002, (−)-epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), resveratrol, and IFN-αA/D were purchased from Sigma. zVAD-FMK, PD98059, and GF109203 were from Calbiochem. U0126 was from Promega. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against human IFN-α and IFN-β were from PBL Biomedical Laboratories. N-glycosidase F (PNGase-F) and endoglycosidase H (endo-H) were purchased from Roche.

Viruses and viral infection.

JEV strain RP-9 (8) was propagated in C6/36 cells. SIN stock was produced by DNA transfection of BHK-21 cells with RSV-dsTE12Q plasmid (29) by using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). For viral infection, cells were adsorbed with virus at the indicated multiplicity of infection (MOI) for 1 to 2 h at 37°C. Virus titers (in PFU/ml) were determined by a plaque-forming assay using BHK-21 cells as described previously (49).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

RNA was extracted with an RNeasy kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was synthesized, and quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis was performed by using a LightCycler and FastStart DNA master plus Sybr green I (Roche). Relative quantification was performed by using standard curve analysis. The data are presented as ratios relative to the results for actin. The primer pairs used are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in this study

| Purpose and protein or region amplified | Forward or single primer | Reverse primer | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning of human Viperin cDNA | |||

| Viperin | 5′-CACAATGTGGGTGCTTACAC-3′ | 5′-GCTCTAGA*CCAATCCAGCTTCAGATCAGCCTT-3′ | *, XbaI recognition site created for cloning purposes |

| RT-PCR | |||

| Viperin | 5′-TGCCACAATGTGGGTGCTTACAC-3′ | 5′-CTCAAGGGGCAGCACAAAGGAT-3′ | Anneals to nt 130 to 152 and 425 to 446 of viperin mRNA |

| Actin | 5′-TCCTGTGGCATCCACGAAACT-3′ | 5′-GAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACGAT-3′ | Anneals to nt 884 to 904 and 1178 to 1198 of beta-actin mRNA |

| Viperin promoter regions cloned in pGL3 | |||

| −1597 | 5′-GTGATGTTTGTGCTGTTGCTGCC-3′ | 5′-TGTGGCAGATGCCTGGAGCA-3′ | Reverse primer anneals |

| −1398 | 5′-TGCCACCCTACAAGTCTTGATCCTC-3′ | to +136 to +117 of the viperin promoter | |

| −838 | 5′-CGCCTGAGATACGTTGCTTTGCT-3′ | region; the numbers | |

| −346 | 5′-CATCCTCCACCAGCCAATCAGTC-3′ | are given relative to | |

| −243 | 5′-AATGCAACAAGTACAAAGCGTGCTG-3′ | the transcription initiation site | |

| −119 | 5′-ATACAAGTGGACTGAGGCAGCCG-3′ | (GenBank accession no. NM_080657; 18 December 2007 version) | |

| −84 | 5′-CGGGGTACC*CCAGGAATGCTCGCCCCG-3′ | *, KpnI recognition site created for cloning purposes | |

| −64 | 5′-CGGGGTACC*CTCTAGTCTTCAGTCTTGGCCCTGTTT-3′ | *, KpnI recognition site created for cloning purposes | |

| −54 | 5′-CGGGGTACC*CAGTCTTGGCCCTGTTTCAACTTTC-3′ | *, KpnI recognition site created for cloning purposes | |

| −36 | 5′-AACTTTCAGTTTCACATGTGGAAAAATC-3′ | ||

| −21 | 5′-ATGTGGAAAAATCGAAACTCTAACTCAGC-3′ | ||

| Single primers for site-directed mutation of viperin promoter constructs | |||

| mAP-1 | 5′-CTAGTCTTCAGTCTTGGCCCTGAAAGAACTTTCAGTTTCACATGTGGAAAA-3′ | The mutated nucleotides are underlined and presented as italic letters | |

| mISRE-5′ | 5′-CAGTCTTGGCCCTGTTTCAACAAACAGTTTCACATGTGGAAAAATCG-3′ | The mutated nucleotides are underlined and presented as italic letters | |

| mISRE-3′ | 5′-TGGCCCTGTTTCAACTTTCAGAAAGACATGTGGAAAAATCGAAACTCTAA-3′ | The mutated nucleotides are underlined and presented as italic letters | |

| ISRE del | 5′-TCAGTCTTGGCCCTGTTTCA ------------CATGTGGAAAAATCGAAACTCTAAC-3′ | The deleted nucleotides are marked by dashes |

Western blotting.

Cells were lysed and subjected to Western blotting as described previously (6). The primary antibodies included M2 anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich), antiactin (Chemicon), anti-JEV NS3 (7), and antiviperin (generated by immunizing rabbits with the C-terminal peptide [346RGGKYIWSKADLKLDW361] coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin as described previously [9]). For the glycosidase assay, Flag-tagged JEV NS1 and viperin were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag M2 affinity gel (Sigma) and then digested with PNGase-F as previously described (30). For endo-H digestion, proteins were boiled in endo-H boiling buffer (50 mM Tris-Cl [pH 6.8], 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 2 mM EDTA) and reacted with endo-H in endo-H incubation buffer (0.15 M sodium citrate [pH 5.3]). After enzymatic reaction at 37°C for 16 h, samples were analyzed by anti-Flag immunoblotting.

Plasmid constructs.

The human viperin gene was cloned from IFN-treated A549 cells by RT-PCR using the primers shown in Table 1. Flag-tagged viperin was generated by subcloning to pFlag/pCR3.1. Various regions of the human viperin promoter were amplified from A549 genomic DNA by PCR using the primers listed in Table 1. PCR products were cloned to the luciferase reporter vector pGL3-Basic (Promega). The first nucleotide of the viperin mRNA (GenBank accession number NM_080657; 18 December 2007 version) is positioned as +1, which differs from the transcription initiation site in a previous report (42). Site-directed mutants of the viperin promoter constructs were generated from the −346 promoter construct by single-primer mutagenesis (31) using the primers listed in Table 1.

LV vector preparation.

Recombinant lentivirus (LV) overexpressing Flag-tagged viperin was generated by the cotransfection of pTY-EF-viperin-Flag plus three helper plasmids, pHP-dl-N/A, pHEF-VSV-G, and pCEP4-tat (5, 13, 23) using GeneJammer transfection reagent (Stratagene). The LV vector pLK0.1-puro carrying the small hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting viperin (nucleotides [nt] 1060 to 1080 of viperin mRNA, 5′-GCGCTTTCTGAACTGTAGAAA-3′) was cotransfected to 293T cells with pMD.G and pCMVRΔ89.1 (obtained from the National RNAi Core Facility, Taiwan) by using Lipofectamine 2000 reagent. The culture supernatants were harvested and used to knock down the endogenous viperin expression in A549 cells by transduction and puromycin selection (10 μg/ml).

Reporter assays.

Vero cells were transfected with 0.5 μg luciferase reporter constructs, 0.05 μg pRL-TK (Promega), and the indicated plasmids by using Lipofectamine reagent. After stimulation, the cell lysates were harvested for the dual-luciferase assays (Promega). The data were normalized for transfection efficiency with the results for Renilla luciferase.

RESULTS

Viperin expression is regulated by viruses at both the RNA and protein levels.

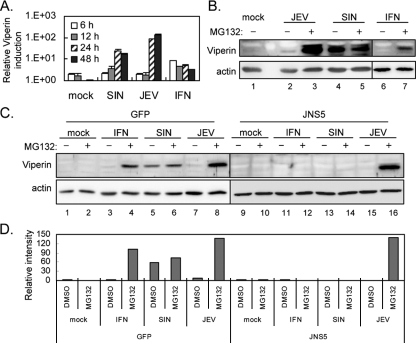

To test whether viperin is induced by JEV and SIN infection, we used real-time RT-PCR to detect viperin expression in human epithelial A549 cells. As expected, the RNA levels of viperin increased in A549 cells upon stimulation with IFN-α, SIN, or JEV (Fig. 1A). However, the protein level of viperin detected by an antiviperin antibody showed conflicting results: viperin protein was detected in SIN-infected cells but was barely present in JEV-infected cells (Fig. 1B). Treatment with a proteasome inhibitor, MG132, readily rescued the viperin protein level in JEV-infected cells, suggesting that viperin protein is degraded by the proteosome pathway in the JEV-infected cells. To test whether IFN-induced Jak-Stat signaling is involved in viperin induction by JEV and SIN as reported for other viruses (9, 39, 42), we used the JEV NS5-overexpressing A549 cell line, in which the IFN-induced Jak-Stat signaling is blocked by the potent IFN antagonist JEV NS5 (29). A549 cells transduced with an LV vector overexpressing JEV NS5 or green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a control were stimulated with either IFN or viruses, and viperin protein expression was detected. GFP control cells (Fig. 1C) behaved like the parental A549 cells, and, as expected, IFN-triggered viperin induction was blocked in NS5-expressing cells (Fig. 1C). SIN failed to induce viperin expression in NS5-expressing cells, indicating that SIN depends on IFN to trigger viperin induction. However, JEV still induced viperin in the NS5-expressing cells treated with MG132, suggesting the existence of an IFN-independent pathway for viperin induction in the JEV-infected cells. These results suggest that SIN and JEV regulate viperin through different mechanisms at both the RNA and protein levels.

FIG. 1.

Viperin is induced at the RNA level but degraded at the protein level in JEV-infected A549 cells. (A) Results of real-time RT-PCR of viperin. Cellular RNA from A549 cells treated with mock infection, SIN (MOI = 5), JEV (MOI = 5), or IFN-α (1,000 IU) was analyzed by real-time RT-PCR. The levels of viperin expression were normalized relative to those of actin. The data shown here are the averages and standard deviations of the results for two independent samples. (B and C) A549 cells (B) and A549-LV-GFP and A549-LV-JNS5 cells (expressing GFP or JEV NS5) (C) were mock infected, infected with JEV or SIN at an MOI of 5, or treated with IFN-α (1,000 IU) in the absence (DMSO solvent control) or presence of MG132 (5 μM) for 24 h. The cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against viperin and actin, respectively. The immunoblots are representative of the results of three independent experiments. (D) The protein band intensities were quantified by using MetaMorph (Universal Imaging Corp.), and the ratios of viperin to actin are shown. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; +, present; −, absent.

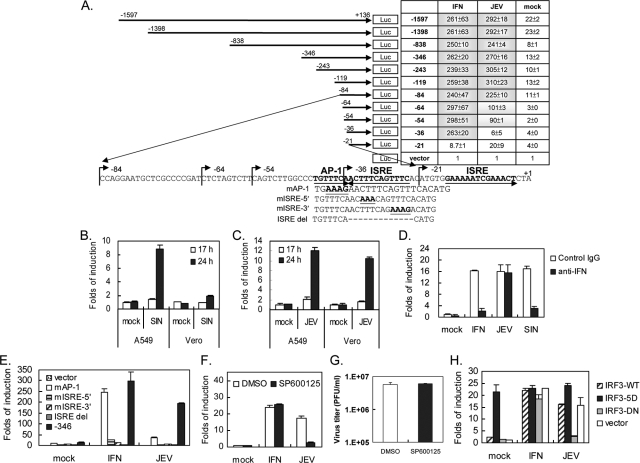

Full induction of the viperin promoter by IFN and JEV requires different regions of the promoter.

To identify the promoter region required for viperin activation by IFN and JEV, we constructed a series of reporter plasmids comprising different lengths of the viperin promoter (between positions −1597 and +136) upstream of a luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 2A). These plasmids were transfected into IFN-nonproducing Vero cells to rule out the influence of IFN, and the luciferase activity was detected after IFN-α or JEV stimulation. Serial deletion of the promoter region from −1597 to −36 did not hamper its response to IFN; however, further deletion to −21 abolished its induction by IFN (Fig. 2A). In contrast, JEV seemed to require a longer promoter region for full induction because deletion from −1597 to −84 conferred full induction (around 270-fold), deletion to −54 resulted in partial induction (around 95-fold), and further deletion to −36 greatly reduced responsiveness to JEV infection. Our results indicate that the regions for full IFN and JEV activation are located within −36 to −21 and −84 to −21 of the viperin promoter, respectively.

FIG. 2.

JEV regulates viperin gene expression through a mechanism that differs from that of IFN. (A) The positions and sequences of the human viperin promoter regions and motifs are given as the nucleotide numbers relative to the transcription initiation site (GenBank accession number NM_080657; 18 December 2007 version). The relative change in induction for each construct is shown in a table to the right. Vero cells transfected with various luciferase (Luc) reporter plasmids for 24 h were stimulated with IFN-α (1,000 IU) or JEV (MOI = 5) for 24 h and then harvested for dual-luciferase assay. The firefly luciferase activity was normalized relative to that of Renilla luciferase, and the change in induction relative to that of the vector control was determined. (B and C) A549 and Vero cells were transfected with the −346 viperin promoter construct for 24 h, and then the cells were infected with SIN (B) or JEV (C) (MOI = 5) for 17 h and 24 h. (D) A549 cells transfected with the −346 viperin promoter construct for 24 h were stimulated with IFN (100 IU) or virus infection (MOI = 5) in the presence of 1,000 neutralization units of anti-IFN-α/β antibodies or an equal amount of control immunoglobulin G (IgG) for another 24 h before harvest for luciferase assay. (E) Vero cells were transfected with the luciferase reporter plasmid containing the wild-type (−346) or mutated viperin promoter. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with IFN-α (1,000 IU) or JEV (MOI = 5) for 24 h and harvested. (F) Vero cells transfected with the −346 reporter plasmid for 24 h were stimulated with IFN-α (1,000 IU) or JEV (MOI = 5) in the absence or presence of SP600125 (40 μM) for 24 h and then harvested for luciferase assay. (G) JEV titers in the culture supernatants from the experiment described for panel F were determined by plaque assay. (H) Vero cells were cotransfected with the −346 reporter plasmid plus the wild-type (IRF-3-WT) or mutated IRF-3-expressing plasmids. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were stimulated with IFN-α (1,000 IU) or JEV (MOI = 5) for 24 h. The changes in induction relative to that of the vector, mock infection, or solvent control are shown as the averages and standard deviations of two independent samples. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; WT, wild type; 5D, S396D/S398D/S402D/T404D/S405D constitutively active; DN, dominant negative.

We then used this reporter system to verify our finding that JEV and SIN induce viperin through different mechanisms. Using the −346 promoter construct, we found that SIN induced luciferase activity in IFN-producing A549 cells, but not in Vero cells (Fig. 2B), whereas JEV induced this promoter activation in both A549 and Vero cells (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, IFN-α/β-neutralizing antibodies blocked the luciferase activity triggered by IFN and SIN, but not that triggered by JEV (Fig. 2D). The results of this luciferase reporter system support our finding that JEV by itself can induce viperin, whereas SIN depends on virus-induced IFN to activate viperin gene expression.

One ISRE site (repeats of GAAANN), which can bind IRFs and the ISGF3 complex, and one AP-1 site (TGTTTCA) were identified in the promoter region −84 to −21 by using the transcription element search system (Fig. 2A). We generated mutations and deletions affecting the AP-1 or ISRE sites on the −346 promoter construct (Fig. 2A). The constructs with the mutation or deletion of the ISRE site, mISRE-5′, mISRE-3′, and ISRE del, lost their responsiveness to IFN and JEV induction (Fig. 2E). However, mutation of the AP-1 site, mAP-1, hampered JEV-induced, but not IFN-induced, viperin promoter activation (Fig. 2E). The involvement of AP-1 in viperin induction was further tested by treatment with SP600125, an inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase (1). At a dose that does not affect JEV production (Fig. 2G), JEV-induced, but not IFN-induced, viperin promoter activity was blocked by SP600125 (Fig. 2F). A dominant-negative form of IRF-3 (IRF-3-DN) (6) decreased viperin induction by JEV, but not that by IFN, verifying the requirement for IRF-3 in JEV-triggered, but not in IFN-triggered, viperin induction (Fig. 2H). Collectively, these data demonstrate that IFN activates viperin through the ISGF3 complex, as reported previously (42), whereas JEV-induced viperin expression is regulated by IRF-3 and AP-1.

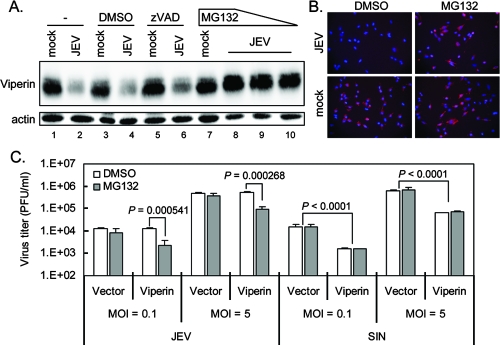

Proteasome inhibitor rescues the protein expression and antiviral effect of viperin against JEV.

To study the antiviral effect of viperin against JEV and SIN infection, we ectopically overexpressed an LV-delivered Flag-tagged viperin in A549 cells (A549-LV-viperin). MG132, but not zVAD-FMK (N-benzyloxycarbonyl-Val-Ala-Asp-fluoromethyl ketone), restored the viperin protein levels, as detected by immunoblotting (Fig. 3A) and immunofluorescence assay (Fig. 3B). These results show that the overexpressed viperin was targeted for protein degradation in JEV-infected, but not in SIN-infected, cells (data not shown) through a proteosome-dependent, but not a caspase-dependent, pathway. To investigate whether the degradation of viperin affects its antiviral activity, A549-LV-viperin or A549-LV-vector control cells were infected with JEV or SIN in the presence or absence of MG132. As shown in Fig. 3C, viperin overexpression had no effect on JEV production, because the viperin was degraded, but viperin overexpression reduced SIN production by ∼10-fold at both high and low MOIs. However, in the presence of MG132, the viral production of JEV decreased by about 90%, while MG132 had no effect on the vector control cells. This indicated that viperin was protected from protein degradation by MG132 and executed its antiviral activity against JEV. Thus, even though viperin is induced, JEV counteracts its antiviral activity by proteasome-mediated protein degradation.

FIG. 3.

The proteasome inhibitor MG132 sustains the protein level and antiviral effect of viperin in JEV-infected cells. (A) A549-LV-viperin cells (−) were infected with JEV (MOI = 5) in the presence of a solvent control (DMSO), zVAD-FMK (150 μM), or MG132 (1, 2.5, or 5 μM) as indicated. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were harvested for immunoblotting with anti-Flag and antiactin antibodies. The immunoblot is representative of the results of two independent experiments. (B) A549-LV-viperin cells were mock infected or infected with JEV (MOI = 5) in the presence of DMSO or MG132 (5 μM) for 24 h and fixed for immunofluorescence assay with anti-Flag antibody. (C) A549-LV-viperin and A549-LV-vector cells were infected with JEV or SIN at an MOI of 0.1 or 5 in the absence (DMSO) or presence of MG132 (5 μM). Eight hours after infection, the supernatants were collected and the virus titer was measured by plaque assay. The data shown here are the averages and standard deviations of the results for three independent samples. Two-tailed Student's t tests were performed. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

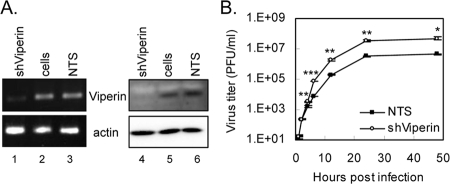

Reduced viperin expression enhances SIN production.

To further verify the involvement of viperin in cellular antiviral defense, we used an RNA interference technique to decrease viperin expression. A549 cells were transduced with a recombinant LV containing an shRNA that targeted viperin mRNA or with a control virus encoding the sequence against the luciferase gene (used as a nontargeting sequence [NTS]). At both the RNA and protein levels, IFN-stimulated viperin expression was decreased substantially by viperin-targeting shRNA in comparison with the level in the control cells (Fig. 4A). Consistent with the overexpression data, the knockdown of viperin expression increased the production of SIN (Fig. 4B) but had no effect on JEV production (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Reduced viperin expression level increases the production of SIN. (A) Knockdown of viperin expression in A549 cells by shRNA-targeting viperin (shViperin). A549 cells were transduced with shRNA-containing LVs and selected by using puromycin (10 μg/ml). The shRNA-targeting luciferase was used as the NTS control. The RNA and protein were harvested and subjected to RT-PCR with viperin-specific primers (left) and immunoblotting with antiviperin antibody (right). The results shown here are representative of the results of two independent experiments. (B) A549 cells from the viperin knockdown or NTS control were infected with SIN (MOI = 5); the supernatants were collected at 1, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after infection; and the virus titers were measured by plaque assay. The data shown here are the averages and standard deviations of the results for three independent samples. The titers at the same time points were compared by two-tailed Student's t tests, and the results are shown as follows: *, P < 0.005; **, P < 0.001; and ***, P < 0.0001.

JEV-induced viperin degradation also requires functional N-linked glycosylation.

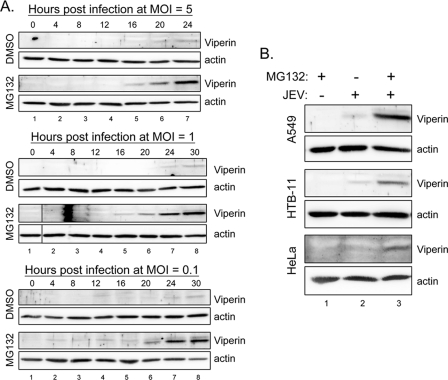

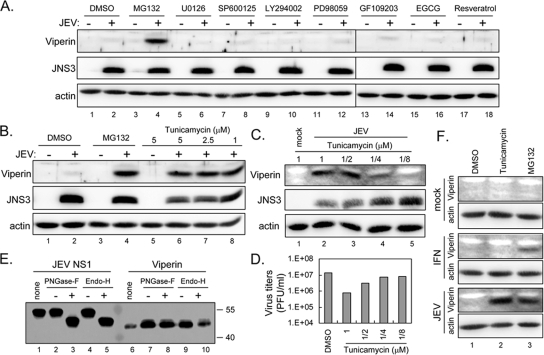

To understand how viperin is degraded in JEV-infected cells, we determined the kinetics of viperin degradation in A549 cells infected with different MOIs of JEV (Fig. 5A). Viperin protein started to be detected in the MG132-treated cells at around 16, 16 to 20, and 20 h postinfection with an MOI of 5, 1, and 0.1, respectively, indicating that with a higher virus inoculation, viperin is induced at an earlier time point. Without MG132, none of the cell lysates had a detectable amount of viperin protein, suggesting that viperin protein is degraded throughout the entire course of the JEV life cycle. To address whether viperin degradation occurs in more than one cell type, another two cell lines besides A549 were tested. As shown in Fig. 5B, viperin was also induced and degraded in HTB-11, a human neuroblastoma cell line, and HeLa, a human cervical carcinoma cell line. It is of interest to further reveal the cellular factors involved in the JEV-induced viperin degradation, and thus, we tested several inhibitors for their effect on viperin protein levels, using doses which have been shown to be effective and noncytotoxic by the manufacturers and the results of our or others' previous studies (15, 21, 28, 50, 51). It appears that viperin degradation cannot be rescued by MEK inhibitors U0126 and PD98059, Jun N-terminal kinase inhibitor SP600125, PI3K inhibitor LY294002, protein kinase C inhibitor GF109203, or antioxidants EGCG and resveratrol (Fig. 6A). However, an N-linked glycosylation inhibitor, tunicamycin, readily restored the viperin protein level (Fig. 6B and C) and resulted in a reduction of virus production in JEV-infected cells (Fig. 6D) in a dose-dependent manner. As two N-linked glycosylation sites are predicted at residues 121 to 124 and 157 to 160 of viperin, we further tested whether viperin is glycosylated. Different from the glycoprotein JEV NS1, whose gel mobility was reduced by PNGase-F or endo-H, viperin was not affected by either of the glycosidases (Fig. 6E), suggesting that viperin is not glycosylated in A549 cells. To further test the role of tunicamycin in viperin degradation, we treated IFN-α- and JEV-stimulated A549 cells with tunicamycin, and it appears that tunicamycin only restores JEV-induced, but not IFN-induced, viperin protein levels (Fig. 6F), indicating that tunicamycin might act specifically on JEV, but not through a general effect on proteasome-dependent degradation machinery. Thus, the antiviral protein viperin is probably targeted for protein degradation in JEV-infected cells through a proteasome-mediated pathway which also depends on a functional N-linked glycosylation system.

FIG. 5.

Viperin degradation by different MOIs of JEV and in different cell types. (A) A549 cells were infected with JEV at an MOI of 5, 1, or 0.1 in the absence (solvent control DMSO) or presence of MG132 (5 μM) for various time points as indicated above the gels. (B) A549, HTB-11, and HeLa cells were mock infected or infected with JEV (MOI = 10) for 24 h with (+) or without (−) treatment with MG132 (5 μM). The cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against viperin and actin, respectively. The immunoblots shown are representative of the results of two independent experiments. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide.

FIG. 6.

Viperin degradation by JEV could be blocked by a glycosylation inhibitor, tunicamycin. (A and B) A549 cells were mock infected (−) or infected (+) with JEV (MOI = 5) for 24 h without (solvent control DMSO) or with treatment with MG132 (5 μM), U0126 (10 μM), SP600125 (40 μM), LY294002 (10 μM), PD98059 (20 μM), GF109203 (10 μM), EGCG (50 μM), resveratrol (50 μM) (A), or tunicamycin (5, 2.5, and 1 μM) (B) as indicated above the gels. The cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against viperin, JEV NS3, and actin, respectively. (C and D) A549 cells were mock infected or infected with JEV (MOI = 5) for 24 h with treatment with tunicamycin (1 to 1/8 μM). The cell lysates were harvested for immunoblotting (C), and the culture supernatants were collected for plaque assays (D). (E) A549 cells transfected with Flag-tagged JEV NS1 or transduced with LV expressing Flag-tagged viperin were harvested and immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag affinity gels before digestion with PNGase-F or endo-H. The samples were then analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-Flag antibody. none, immunoprecipitation only, no incubation; +, incubation with enzyme; −, incubation with buffer only. Molecular masses (in kilodaltons) of protein standards are shown to the right of the gel. (F) A549 cells were treated with IFN-α (1,000 IU), JEV (MOI = 5), or mock infection in the presence of DMSO, tunicamycin (5 μM), or MG132 (5 μM) for 24 h. The cell lysates were collected and subjected to immunoblotting using antibodies against viperin and actin as indicated on the left. The immunoblots shown are representative of the results of two independent experiments. DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; JNS3, JEV NS3.

DISCUSSION

The results of several studies have shown that viperin is highly induced at the RNA level by various stimuli, but few studies have investigated viperin protein expression. We found that JEV counteracts the antiviral activity of viperin through a newly described downregulatory mechanism involving protein degradation. Viperin protein was detectable only in JEV-infected cells after treatment with MG132 (Fig. 1), and viperin decreased JEV production only when MG132 was present (Fig. 3). A similar example showing that a virus adapts protein degradation to downregulate the host's antiviral defense is that human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virion infectivity factor targets the antiviral protein APOBEC3G for degradation to protect the viral DNA from G-to-A hypermutation (43). Virion infectivity factor targets APOBEC3G for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation by forming an SCF-like E3-ubiquitin ligase complex (26, 32, 43). We attempted to reveal the molecular mechanism underlying the JEV mediation of viperin degradation by determining the JEV protein that targets viperin for degradation. Transfection with any of the individual JEV proteins failed to cause viperin degradation, suggesting that a combined effect of viral proteins or viral RNA replication is required for viperin degradation. Because viperin protein levels were also rescued by MG132 in IFN-stimulated cells (Fig. 1B and C), we thought that IFN-induced protein degradation machinery might be responsible for viperin degradation. However, viperin protein was still degraded by JEV in a cell line whose IFN-induced Jak-Stat signaling was blocked by a potent IFN antagonist, JEV NS5 (29) (Fig. 1C), suggesting that IFN signaling does not participate in JEV-triggered viperin degradation.

Protein degradation is as essential to the cell as protein synthesis, and regulated protein degradation by proteasome is the main mechanism for controlling intracellular protein levels (11). The degradation of a protein via the proteasome pathway involves two steps: the covalent conjugation of the polyubiquitin chain to the target proteins and the degradation of the ubiquitinated proteins by the cytoplasmic 26S proteasome (10, 16). MG132, a potent, membrane-permeable proteasome inhibitor (36, 45), effectively restores the viperin protein level in JEV-infected cells, suggesting that viperin is degraded in a proteasome-mediated pathway. A screening with various inhibitors revealed an unexpected finding that tunicamycin also rescues the viperin protein level in JEV-infected cells (Fig. 6). Tunicamycin blocks the first step in the lipid-linked saccharide pathway and thus prevents protein glycosylation (14). Two N-linked glycosylation sites are predicted in viperin, but viperin may not be glycosylated, as PNGase-F and endo-H did not reduce its protein mobility in sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Fig. 6E). Tunicamycin is a known endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress inducer that triggers the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER (41). The proteins that fail the ER quality control are transported back to the cytosol, where they are degraded by the proteasome system in a process known as ER-associated degradation (37). It has also been found that ER stress has an inhibitory effect on the functionality of the proteasome system (33). The finding that tunicamycin rescues the JEV-induced viperin protein degradation might be due to the impairing effect of tunicamycin on proteasome activity or, possibly, to other independent mechanisms, such as the blocking of JEV glycoprotein processing. Thus, the exact mechanism responsible for JEV-induced viperin degradation awaits further investigation.

Viperin can be induced by various stimuli through IFN-dependent and -independent mechanisms. IFN activates viperin through ISGF3 binding to the ISRE site, which is also counterregulated by BLIMP1 (42). JEV by itself is a potent viperin inducer through an IFN-independent mechanism (Fig. 2), and it provides a tool to reveal the molecular mechanism responsible for IFN-independent viperin induction. Our findings indicate that AP-1 and IRF-3 are two key players involved in JEV-mediated, but not in IFN-mediated, viperin induction (Fig. 2). The viperin gene is upregulated by IRF-3 (17), whereas our data implicate AP-1 in the regulation of viperin gene expression for the first time. The sequences upstream of the AP-1 site might also contain certain elements for JEV-induced viperin expression, because a full induction was noted in the −84 promoter construct but a partial induction was noted in the −64 construct (Fig. 2A). An M-CAT binding factor (MCBF; also known as transcriptional enhancer factor 1) consensus sequence (CATTCCT) is found in position −76 to −82 of the viperin promoter. MCBF has been implicated in the regulation of several cardiac and skeletal muscle genes (18) and recently also in an IFN-inducible transmembrane protein (12). Whether MCBF also plays a role in viperin induction remains to be studied.

Two ISRE sites are found in the viperin promoter (42), and the positions of these sites in this study (−35 to −24 and −16 to −3) differ from those in a previous report because of a different transcription initiation site in the new version of the nucleotide sequence under GenBank accession no. NM_080657. The distal ISRE (−35 to −24) appears to play a more important role than the proximal one (−16 to −3), because the promoter construct containing only the proximal ISRE and constructs with mutation or deletion of the distal ISRE site failed to be activated by IFN and JEV (Fig. 2). The ISRE is known to be activated by the IFN-stimulated ISGF3 complex; however, the ISRE in some of the ISGs could also be induced by IRF-3 (17, 34). Viperin appears to be induced by both IFN and IRF-3 (17). The IFN-induced viperin gene induction is blocked by anti-IFN antibodies (Fig. 2D) and the Jak-Stat signaling blocker JEV NS5 (Fig. 1C), but not by an IRF-3 dominant negative construct (Fig. 2H), suggesting that IFN triggers viperin promoter activation through the ISGF3 complex. In JEV-infected cells, viperin gene expression is dependent on IRF-3, as an IRF-3 dominant negative construct hampers its induction (Fig. 2H), but not on IFN signaling, as JEV NS5 (Fig. 1C) and anti-IFN antibodies (Fig. 2D) did not block its induction. Thus, the distal ISRE site on the viperin promoter responds to both ISGF3 and IRF-3, which are activated by IFN and JEV (6), respectively.

In conclusion, we found that viperin transcription was greatly induced by JEV; however, viperin protein was degraded by the proteosome pathway in JEV-infected cells. SIN could induce viperin only in an IFN-dependent manner and did not trigger viperin protein degradation. The discrepancy between these two viruses results in different antiviral effects in responding to the overexpression or depletion of viperin in the cells. In addition to the previously identified ISGF3 complex, which binds to the ISRE site triggered by IFN (42), an AP-1- and IRF-3-dependent mechanism was found to be responsible for JEV stimulation. Our findings demonstrate a balanced regulation of the antiviral protein viperin at the RNA and protein levels in different viral infection systems.

Acknowledgments

We thank TRC (The RNAi Consortium) for the viperin-targeted shRNA constructs and L. J. Chang for the pTY-EF1α LV system.

This work was supported by grants awarded to Y.-L.L. from the National Science Council (NSC-95-2320-B-001-031-MY3 and NSC 96-3112-B-001-021) and Academia Sinica, Taiwan.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bennett, B. L., D. T. Sasaki, B. W. Murray, E. C. O'Leary, S. T. Sakata, W. Xu, J. C. Leisten, A. Motiwala, S. Pierce, Y. Satoh, S. S. Bhagwat, A. M. Manning, and D. W. Anderson. 2001. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9813681-13686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borden, E. C., G. C. Sen, G. Uze, R. H. Silverman, R. M. Ransohoff, G. R. Foster, and G. R. Stark. 2007. Interferons at age 50: past, current and future impact on biomedicine. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 6975-990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boudinot, P., P. Massin, M. Blanco, S. Riffault, and A. Benmansour. 1999. vig-1, a new fish gene induced by the rhabdovirus glycoprotein, has a virus-induced homologue in humans and shares conserved motifs with the MoaA family. J. Virol. 731846-1852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudinot, P., S. Riffault, S. Salhi, C. Carrat, C. Sedlik, N. Mahmoudi, B. Charley, and A. Benmansour. 2000. Vesicular stomatitis virus and pseudorabies virus induce a vig1/cig5 homologue in mouse dendritic cells via different pathways. J. Gen. Virol. 812675-2682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang, L. J., V. Urlacher, T. Iwakuma, Y. Cui, and J. Zucali. 1999. Efficacy and safety analyses of a recombinant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 derived vector system. Gene Ther. 6715-728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, T. H., C. L. Liao, and Y. L. Lin. 2006. Flavivirus induces interferon-beta gene expression through a pathway involving RIG-I-dependent IRF-3 and PI3K-dependent NF-kappaB activation. Microbes Infect. 8157-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen, L. K., C. L. Liao, C. G. Lin, S. C. Lai, C. I. Liu, S. H. Ma, Y. Y. Huang, and Y. L. Lin. 1996. Persistence of Japanese encephalitis virus is associated with abnormal expression of the nonstructural protein NS1 in host cells. Virology 217220-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen, L. K., Y. L. Lin, C. L. Liao, C. G. Lin, Y. L. Huang, C. T. Yeh, S. C. Lai, J. T. Jan, and C. Chin. 1996. Generation and characterization of organ-tropism mutants of Japanese encephalitis virus in vivo and in vitro. Virology 22379-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin, K. C., and P. Cresswell. 2001. Viperin (cig5), an IFN-inducible antiviral protein directly induced by human cytomegalovirus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9815125-15130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ciechanover, A. 2005. Proteolysis: from the lysosome to ubiquitin and the proteasome. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 679-87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ciechanover, A., and A. L. Schwartz. 2002. Ubiquitin-mediated degradation of cellular proteins in health and disease. Hepatology 353-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuddapah, S., K. Cui, and K. Zhao. 2008. Transcriptional enhancer factor 1 (TEF-1/TEAD1) mediates activation of IFITM3 gene by BRGl. FEBS Lett. 582391-397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cui, Y., T. Iwakuma, and L.-J. Chang. 1999. Contributions of viral splice sites and cis-regulatory elements to lentivirus vector function. J. Virol. 736171-6176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elbein, A. D. 1987. Inhibitors of the biosynthesis and processing of N-linked oligosaccharide chains. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 56497-534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fimia, G. M., C. Evangelisti, T. Alonzi, M. Romani, F. Fratini, G. Paonessa, G. Ippolito, M. Tripodi, and M. Piacentini. 2004. Conventional protein kinase C inhibition prevents alpha interferon-mediated hepatitis C virus replicon clearance by impairing STAT activation. J. Virol. 7812809-12816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glickman, M. H., and A. Ciechanover. 2002. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol. Rev. 82373-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grandvaux, N., M. J. Servant, B. tenOever, G. C. Sen, S. Balachandran, G. N. Barber, R. Lin, and J. Hiscott. 2002. Transcriptional profiling of interferon regulatory factor 3 target genes: direct involvement in the regulation of interferon-stimulated genes. J. Virol. 765532-5539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta, M. P., C. S. Amin, M. Gupta, N. Hay, and R. Zak. 1997. Transcription enhancer factor 1 interacts with a basic helix-loop-helix zipper protein, Max, for positive regulation of cardiac alpha-myosin heavy-chain gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 173924-3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanzelmann, P., H. L. Hernandez, C. Menzel, R. Garcia-Serres, B. H. Huynh, M. K. Johnson, R. R. Mendel, and H. Schindelin. 2004. Characterization of MOCS1A, an oxygen-sensitive iron-sulfur protein involved in human molybdenum cofactor biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 27934721-34732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Helbig, K. J., D. T. Lau, L. Semendric, H. A. Harley, and M. R. Beard. 2005. Analysis of ISG expression in chronic hepatitis C identifies viperin as a potential antiviral effector. Hepatology 42702-710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Huang, Y., X. C. Chen, M. Konduri, N. Fomina, J. Lu, L. Jin, A. Kolykhalov, and S. L. Tan. 2006. Mechanistic link between the anti-HCV effect of interferon gamma and control of viral replication by a Ras-MAPK signaling cascade. Hepatology 4381-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ishii, K. J., C. Coban, H. Kato, K. Takahashi, Y. Torii, F. Takeshita, H. Ludwig, G. Sutter, K. Suzuki, H. Hemmi, S. Sato, M. Yamamoto, S. Uematsu, T. Kawai, O. Takeuchi, and S. Akira. 2006. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat. Immunol. 740-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwakuma, T., Y. Cui, and L. J. Chang. 1999. Self-inactivating lentiviral vectors with U3 and U5 modifications. Virology 261120-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jiang, D., H. Guo, C. Xu, J. Chang, B. Gu, L. Wang, T. M. Block, and J. T. Guo. 2008. Identification of three interferon-inducible cellular enzymes that inhibit the replication of hepatitis C virus. J. Virol. 821665-1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khaiboullina, S. F., A. A. Rizvanov, M. R. Holbrook, and S. St. Jeor. 2005. Yellow fever virus strains Asibi and 17D-204 infect human umbilical cord endothelial cells and induce novel changes in gene expression. Virology 342167-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kobayashi, M., A. Takaori-Kondo, Y. Miyauchi, K. Iwai, and T. Uchiyama. 2005. Ubiquitination of APOBEC3G by an HIV-1 Vif-Cullin5-Elongin B-Elongin C complex is essential for Vif function. J. Biol. Chem. 28018573-18578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Layer, G., K. Verfurth, E. Mahlitz, and D. Jahn. 2002. Oxygen-independent coproporphyrinogen-III oxidase HemN from Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 27734136-34142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee, C. J., C. L. Liao, and Y. L. Lin. 2005. Flavivirus activates phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling to block caspase-dependent apoptotic cell death at the early stage of virus infection. J. Virol. 798388-8399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, R. J., B. L. Chang, H. P. Yu, C. L. Liao, and Y. L. Lin. 2006. Blocking of interferon-induced Jak-Stat signaling by Japanese encephalitis virus NS5 through a protein tyrosine phosphatase-mediated mechanism. J. Virol. 805908-5918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin, Y. L., L. K. Chen, C. L. Liao, C. T. Yeh, S. H. Ma, J. L. Chen, Y. L. Huang, S. S. Chen, and H. Y. Chiang. 1998. DNA immunization with Japanese encephalitis virus nonstructural protein NS1 elicits protective immunity in mice. J. Virol. 72191-200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Makarova, O., E. Kamberov, and B. Margolis. 2000. Generation of deletion and point mutations with one primer in a single cloning step. BioTechniques 29970-972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mehle, A., B. Strack, P. Ancuta, C. Zhang, M. McPike, and D. Gabuzda. 2004. Vif overcomes the innate antiviral activity of APOBEC3G by promoting its degradation in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2797792-7798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Menendez-Benito, V., L. G. Verhoef, M. G. Masucci, and N. P. Dantuma. 2005. Endoplasmic reticulum stress compromises the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Hum. Mol. Genet. 142787-2799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nakaya, T., M. Sato, N. Hata, M. Asagiri, H. Suemori, S. Noguchi, N. Tanaka, and T. Taniguchi. 2001. Gene induction pathways mediated by distinct IRFs during viral infection. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 2831150-1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Olofsson, P. S., K. Jatta, D. Wagsater, S. Gredmark, U. Hedin, G. Paulsson-Berne, C. Soderberg-Naucler, G. K. Hansson, and A. Sirsjo. 2005. The antiviral cytomegalovirus inducible gene 5/viperin is expressed in atherosclerosis and regulated by proinflammatory agents. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 25e113-e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Palombella, V. J., O. J. Rando, A. L. Goldberg, and T. Maniatis. 1994. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway is required for processing the NF-kappa B1 precursor protein and the activation of NF-kappa B. Cell 78773-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Plemper, R. K., and D. H. Wolf. 1999. Retrograde protein translocation: ERADication of secretory proteins in health and disease. Trends Biochem. Sci. 24266-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rempel, J. D., L. A. Quina, P. K. Blakely-Gonzales, M. J. Buchmeier, and D. L. Gruol. 2005. Viral induction of central nervous system innate immune responses. J. Virol. 794369-4381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rivieccio, M. A., H. S. Suh, Y. Zhao, M. L. Zhao, K. C. Chin, S. C. Lee, and C. F. Brosnan. 2006. TLR3 ligation activates an antiviral response in human fetal astrocytes: a role for viperin/cig5. J. Immunol. 1774735-4741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sariol, C. A., J. L. Munoz-Jordan, K. Abel, L. C. Rosado, P. Pantoja, L. Giavedoni, I. V. Rodriguez, L. J. White, M. Martinez, T. Arana, and E. N. Kraiselburd. 2007. Transcriptional activation of interferon-stimulated genes but not of cytokine genes after primary infection of rhesus macaques with dengue virus type 1. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14756-766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schroder, M. 2008. Endoplasmic reticulum stress responses. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65862-894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Severa, M., E. M. Coccia, and K. A. Fitzgerald. 2006. Toll-like receptor-dependent and -independent viperin gene expression and counter-regulation by PRDI-binding factor-1/BLIMP1. J. Biol. Chem. 28126188-26195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheehy, A. M., N. C. Gaddis, and M. H. Malim. 2003. The antiretroviral enzyme APOBEC3G is degraded by the proteasome in response to HIV-1 Vif. Nat. Med. 91404-1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sofia, H. J., G. Chen, B. G. Hetzler, J. F. Reyes-Spindola, and N. E. Miller. 2001. Radical SAM, a novel protein superfamily linking unresolved steps in familiar biosynthetic pathways with radical mechanisms: functional characterization using new analysis and information visualization methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 291097-1106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tsubuki, S., H. Kawasaki, Y. Saito, N. Miyashita, M. Inomata, and S. Kawashima. 1993. Purification and characterization of a Z-Leu-Leu-Leu-MCA degrading protease expected to regulate neurite formation: a novel catalytic activity in proteasome. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1961195-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verma, S., K. Ziegler, P. Ananthula, J. K. Co, R. J. Frisque, R. Yanagihara, and V. R. Nerurkar. 2006. JC virus induces altered patterns of cellular gene expression: interferon-inducible genes as major transcriptional targets. Virology 345457-467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang, S. C., and P. A. Frey. 2007. S-adenosylmethionine as an oxidant: the radical SAM superfamily. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32101-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang, X., E. R. Hinson, and P. Cresswell. 2007. The interferon-inducible protein viperin inhibits influenza virus release by perturbing lipid rafts. Cell Host Microbe 296-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu, S. F., C. J. Lee, C. L. Liao, R. A. Dwek, N. Zitzmann, and Y. L. Lin. 2002. Antiviral effects of an iminosugar derivative on flavivirus infections. J. Virol. 763596-3604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Youn, H. S., J. Y. Lee, K. A. Fitzgerald, H. A. Young, S. Akira, and D. H. Hwang. 2005. Specific inhibition of MyD88-independent signaling pathways of TLR3 and TLR4 by resveratrol: molecular targets are TBK1 and RIP1 in TRIF complex. J. Immunol. 1753339-3346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yu, C. Y., Y. W. Hsu, C. L. Liao, and Y. L. Lin. 2006. Flavivirus infection activates the XBP1 pathway of the unfolded protein response to cope with endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Virol. 8011868-11880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang, Y., C. W. Burke, K. D. Ryman, and W. B. Klimstra. 2007. Identification and characterization of interferon-induced proteins that inhibit alphavirus replication. J. Virol. 8111246-11255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu, H., J. P. Cong, and T. Shenk. 1997. Use of differential display analysis to assess the effect of human cytomegalovirus infection on the accumulation of cellular RNAs: induction of interferon-responsive RNAs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9413985-13990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]