Abstract

The ML protein of Thogoto virus, a tick-transmitted orthomyxovirus, is a splice variant of the viral matrix protein and antagonizes the induction of antiviral type I interferon (IFN). Here we identified the general RNA polymerase II transcription factor IIB (TFIIB) as an ML-interacting protein. Overexpression of TFIIB neutralized the inhibitory effect of ML on IRF3-mediated promoter activation. Moreover, a recombinant virus expressing a mutant ML protein unable to bind TFIIB was severely impaired in its ability to suppress IFN induction. We concluded that TFIIB binding is required for the IFN antagonist effect exerted by ML. We further demonstrate that the ML-TFIIB interaction has surprisingly little impact on gene expression in general, while a strong negative effect is observed for IRF3- and NF-κB-regulated promoters.

Recognition of virus-specific molecular patterns triggers the expression of type I interferon (IFN-α/β) and thereby induces production of antiviral proteins. In the case of orthomyxovirus infection, Mx proteins represent potent antiviral effector molecules induced by IFN. Mx proteins limit the replication of influenza viruses (12, 35) as well as the related Thogoto virus (THOV) (17, 27, 36). IRF3 plays a central role in activation of the IFN-β promoter. This transcription factor is constitutively expressed but must be phosphorylated to become active. Phosphorylation occurs when the kinases TBK-1 and IKKɛ are activated by signals coming from pattern recognition receptors, such as the cytoplasmic receptors for viral nucleic acids Mda5 and RIG-I (45). Phosphorylated IRF3 homodimerizes and translocates to the nucleus, where, together with NF-κB and AP-1, it forms a complex on the promoter. This so-called enhanceosome recruits RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) via the transcriptional coactivator CREB-binding protein (CBP) (2, 19, 42). Viruses have evolved various strategies to circumvent the type I IFN response (18, 38). Many carry proteins that interfere with virus recognition or IRF3 activation. Examples are NS1 of influenza A virus complexing with RIG-I (34) and rabies virus phosphoprotein suppressing IRF3 phosphorylation (9).

THOV belongs to the orthomyxovirus family and is structurally and genetically related to influenza viruses. It is a tick-borne virus and has the capacity to replicate in mammalian hosts (e.g., rodents and domestic animals in Africa and Southern Europe) as well as in the insect reservoir (8, 10, 16). The THOV genome consists of six single-stranded RNA segments of negative polarity. Besides coding for six essential proteins (three viral polymerase subunits, the nucleoprotein, the surface glycoprotein, and the matrix protein M), it contains genetic information for the nonessential protein ML. Both M and ML are encoded on segment 6. The M reading frame is terminated by a stop codon created by a splicing event (28). ML (304 amino acids [aa]) is translated from the full-length, unspliced transcript and thus represents an elongated variant of M (266 aa), with 38 additional amino acids at the C terminus. The protein is found mainly in the nucleus when it is expressed from a transfected plasmid (21). A natural ML-deficient isolate (SiAr126) and the recombinant THOVML− have a single nucleotide insertion in the intron of segment 6 (6× U instead of 5× U), abolishing ML expression (15). ML acts as an IFN antagonist in cell culture (15) and in vivo (36). We have previously shown that ML antagonizes IRF3-mediated IFN induction by inhibiting IRF3 dimerization and association with CBP, while still allowing nuclear translocation of IRF3 (21). The fact that ML also suppressed promoter activation by constitutively active IRF3(5D) indicated that it is able to interfere with a very late step of IFN induction. In order to understand the mechanism of action of this viral IFN antagonist, we set out to identify cellular interaction partners of ML.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

293T cells and A549 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. For infection studies, virus stocks were diluted in DMEM supplemented with 2% fetal calf serum and 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.3. Recombinant THOVs expressing ML (THOVML+) or lacking ML (THOVML−) were described previously (15, 40). In addition, they were newly generated in this study together with viruses bearing mutated ML proteins, i.e., THOVML(SW/AA) and THOVML(TE/AA). In this study, bidirectional pHW2000 rescue plasmids (20) were used. The pHW2000 vector was kindly provided by R. G. Webster, St. Jude Children's Research Hospital, Memphis, TN. Sendai virus (SeV) strain Cantell (6) was grown on 10-day-old embryonated chicken eggs, and allantoic fluid was used to infect cell cultures.

Plasmids.

pCAGGS expression plasmids for M and ML were described previously (15). pCDNA-M and -ML were obtained after transfer of the open reading frames into pCDNA3.1. pCDNA-ML(S283A/W284A) and pCDNA-ML(T270A/E271A) were generated from pCDNA-ML by site-directed mutagenesis. pCAGGS-TAP-ML encoding ML with an N-terminal tandem affinity purification (TAP) tag was constructed by inserting the ML open reading frame into a pMSCVpuroTAP-plasmid (33) and later transferring the TAP-ML sequence to pCAGGS. In order to obtain a fusion protein efficiently cleaved by the tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease, the sequence for the TEV cleavage site within the TAP tag was duplicated. Therefore, two PCR fragments were generated, with one encoding the N-terminal part and the second encoding the C-terminal part of the fusion protein and both including the TEV cleavage site. When the PCR fragments were ligated, the sequence of the tag was restored with a double TEV cleavage site.

pCAGGS-IRF3 was described previously (5). For the generation of pCAGGS-TFIIB, TFIIB-encoding cDNA from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells was inserted into pCAGGS. The plasmid encoding glutathione S-transferase-TFIIB (GST-TFIIB), pGEX-TFIIB(5-316), was a kind gift from R. Schneider, Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology, Freiburg, Germany. Reporter plasmids carrying the firefly luciferase gene under the control of either the IFN-β promoter (p125Luc) or an artificial promoter containing three IRF3 binding sites (p55C1BLuc) (46) were kindly provided by T. Fujita, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan. pIRF1-Luc containing firefly luciferase under the control of GAS elements from the IRF1 promoter (25) was a gift from S. Goodbourn, University of London, United Kingdom. The NF-κB-dependent firefly luciferase reporter plasmid pNFκB-Luc was purchased from Stratagene, and a reporter plasmid carrying the Renilla luciferase gene under the control of the constitutively active simian virus 40 (SV40) promoter was purchased from Promega.

Transfection.

For transfection of 293T cells, Metafectene (Biontex, Martinsried, Germany) or Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) was preincubated with plasmid DNA in Optimem (Gibco BRL) following the manufacturer's instructions. Transfection complexes were administered to cells in normal culture medium, and the medium was changed at 6 h posttransfection.

Purification of TAP-ML and mass spectrometric analysis.

Approximately 5 × 106 293T cells (in a 9.6-cm culture dish) were transfected with 15 μg pCAGGS-TAP-ML. At 24 h posttransfection, the cells were lysed and purification of the TAP-tagged protein and associated proteins was performed as described by Fodor and Smith (14), until the TEV elution step. One-tenth of the TEV-eluted fractions was separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and silver stained, and 1/10 was equally separated but stained with Cypro Ruby (Invitrogen). From this gel, visible protein bands were excised, digested with trypsin, and further analyzed by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry as described previously in detail (26).

GST pull-down assay.

M and ML were synthesized in vitro in the presence of [35S]methionine by use of the TNT quick coupled transcription/translation system (Promega). Escherichia coli BL21 cells were transformed with pGEX-4T-2 or pGEX-2T-TFIIB(5-316). Cultures were grown at 28°C, and expression of GST or GST-TFIIB fusion protein, respectively, was induced at an optical density at 600 nm of approximately 0.4 by the addition of 0.1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). Six hours after the addition of IPTG, the cells were harvested, washed once in PBS, and frozen at −20°C. To prepare lysates, bacteria from 50 ml of culture were resuspended in 5 ml PBS and sonicated on ice. After the addition of 1% Triton X-100, the lysates were incubated on ice for 15 min and centrifuged at 20,000 × g (4°C) for 25 min. Cleared lysates were mixed with 250 μl glutathione agarose (50% in H2O; Sigma) and rotated at 4°C for 2 h. After binding of the recombinant proteins, the agarose was washed three times with PBS. To visualize the recombinant proteins bound to the glutathione agarose, aliquots of the beads were heated in sample buffer and proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie blue. For the pull-down experiments, equivalent amounts of immobilized GST and GST-TFIIB were incubated overnight with 1 μl [35S]methionine-labeled M or ML protein in PBS containing protease inhibitors (Complete; Roche) and blocking reagent (Roti-Block; Roth). After being washed with PBS, precipitates were separated by SDS-PAGE, and M or ML was detected by autoradiography.

Coimmunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

293T cells were lysed on ice in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and 1% NP-40, vortexed briefly, and centrifuged at 10,000 × g (4°C) for 10 min. Cleared lysates were incubated with mouse anti-TFIIB (TFIIB8; Covance) diluted 1:100, mouse anti-hemagglutinin (anti-HA) clone 12CA5 (Roche) diluted 1:100, or rabbit anti-CBP (A-22; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 6 h or overnight at 4°C. Antigen-antibody complexes were precipitated with protein A Sepharose (Amersham) for 1 h at 4°C (with rotation). Sepharose beads were washed three times in lysis buffer, and bound proteins were subjected to Western blot analysis with the anti-TFIIB antibody diluted 1:1,000, a polyclonal rabbit serum directed against THOV M and ML, a polyclonal rabbit serum directed against THOV NP, rabbit anti-HA (Sigma) diluted 1:1,000, or monoclonal anti-IRF3 (SL12; BD Pharmingen) diluted 1:500. Horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies were purchased from Amersham.

Analysis of protein synthesis in infected cells.

Vero cells seeded in six-well plates were infected and metabolically labeled at different time points postinfection. Therefore, cells were incubated for 90 min in 500 μl DMEM containing 100 μCi/ml [35S]methionine-cysteine (Promix; Amersham). Directly after being labeled, the cells were washed twice in PBS and lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 8, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 0.25% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS) containing protease inhibitors (Complete; Roche). Cleared lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE. Gels were fixed in 40% ethanol-10% acetic acid for 30 min, incubated for 1 h in distilled H2O, and dried under a vacuum. Biomax MR films (Kodak) were exposed overnight.

Reporter gene assays.

293T cells in six-well plates were transfected with 0.5 μg of the indicated firefly luciferase reporter plasmids and 0.05 μg pRLSV40. Eventually, expression plasmids were cotransfected (1 μg or as indicated). In some cases, the cells were infected at 6 h posttransfection or stimulated through replacement of the medium by medium supplemented with cytokines (IFN-γ from Roche and tumor necrosis factor alpha [TNF-α] from Promega). Firefly and Renilla luciferase expression was quantified at 24 h posttransfection, using a dual-luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega).

Reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR).

RNA was extracted with the help of PeqGold TriFast (Peqlab) and reverse transcribed using RevertAid H Minus Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Fermentas) and random hexanucleotide primers (Gibco BRL). With the cDNA, PCR (30 amplification cycles) was performed using the following primers (5′-3′): GACGCCGCATTGACCATCTA (forward) and CCTTAGGATTTCCACTCTGACT (reverse) for human IFN-β, GCCGGTCGCAATGGAAGAAGA (forward) and CATGGCCGGGGTGTTGAAGGTC (reverse) for human γ-actin, CTGACATGCCGCCTGGAGAAAC (forward) and CCGGCATCGAAGGTGGAAGAGT (reverse) for human glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH), GCCTGCCGCCGCCTCTT (forward) and GAAATCTGTCATGCTGGTCTGC (reverse) for human p21, CGGCTGCGTGTATTTTGGGACTC (forward) and TCTTCGGGGGCAGGCTCACC (reverse) for human A20, CCCCAGGAGAAGATTCCA (forward) and AAAGCTGCGCAGAATGAGAT (reverse) for human interleukin-6 (IL-6), and GATCTACGCCAACGGTCACG (forward) and GGAAACAAAAATCAACCGAAC (reverse) for THOV NP.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

THOV ML interacts with TFIIB.

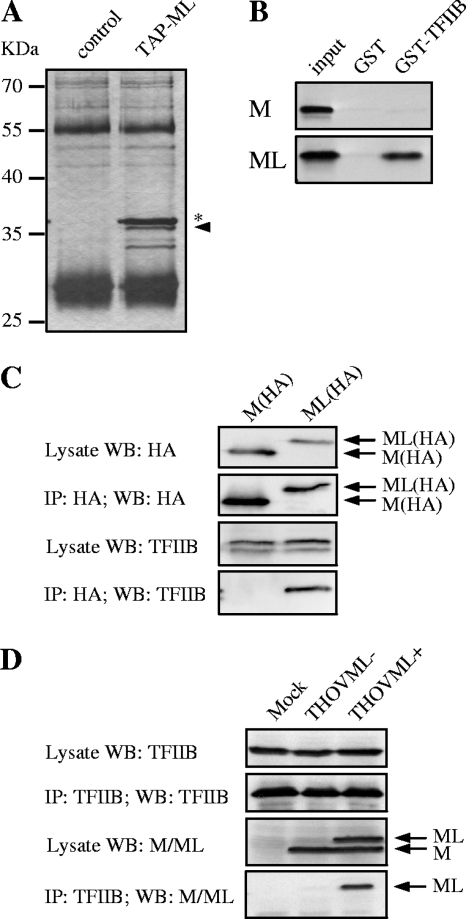

In order to purify ML-containing protein complexes, we constructed the expression plasmid pCAGGS-TAP-ML, encoding ML with a TAP tag (33, 37) fused to its N terminus. Note that all ML expression plasmids used in this work are based on pCAGGS-MLΔSA, expressing only ML, not M, due to mutational inactivation of the splice acceptor site (15). Approximately 5 × 106 293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-TAP-ML or left untreated (control) and then were lysed at 24 h posttransfection. ML-containing protein complexes were allowed to bind to immunoglobulin G (IgG) Sepharose and, after being washed, were released by TEV protease cleaving behind the protein A part of the TAP tag. One-tenth of the eluted fraction was then separated by SDS-PAGE and silver stained. A protein with a molecular mass of about 36 kDa (Fig. 1A) appeared in two independent purifications and was identified by mass spectrometry as the general RNAPII transcription factor TFIIB. Additional bands seen in the TAP-ML lane of Fig. 1A did not appear in a second purification and were therefore not further analyzed. To assess ML-TFIIB interaction in a second system, we performed in vitro binding experiments. In vitro-translated and radioactively labeled ML was incubated with GST/GST-TFIIB immobilized on glutathione agarose. In vitro-translated M protein was used as a specificity control. Precipitated M and ML were detected by autoradiography following SDS-PAGE, and as shown in Fig. 1B, ML but not M interacted with GST-TFIIB. Next, HA-tagged ML was expressed in 293T cells and precipitated with an HA-specific antibody. TFIIB could be detected only in the ML precipitates, not in the M precipitates used as a control (Fig. 1C). To further demonstrate the interaction of virus-encoded ML with TFIIB, endogenous TFIIB was immunoprecipitated from 293T cells infected with THOVML− and THOVML+. Lysates and precipitates were stained with the TFIIB-specific antibody as well as with a serum directed against M and ML. Figure 1D shows that virus-expressed ML but not M precipitated with endogenous TFIIB, indicating a specific TFIIB-ML interaction in infected cells.

FIG. 1.

(A) Purification of THOV ML-containing protein complexes. Lysates of transiently TAP-ML-expressing and nontransfected (control) 293T cells were incubated with IgG Sepharose. After being washed, protein complexes were eluted by incubation with TEV protease. Eluted fractions are shown on a silver-stained SDS gel. The eluted ML is marked with an asterisk; the arrowhead indicates copurified TFIIB. The two other bands visible only in the TAP-ML lane did not appear in a second purification and were not analyzed. Bands at approximately 25 and 55 kDa and also appearing in the control lane represent IgG. (B) In vitro binding of ML to TFIIB. Radioactively labeled in vitro-translated M and ML were assessed for binding to bacterially expressed GST-TFIIB. Autoradiography of input protein (1 μl of M or ML) and glutathione agarose precipitates separated by SDS-PAGE is shown. (C) Coimmunoprecipitation of TFIIB with HA-tagged ML. 293T cells were transfected with pCAGGS-M(HA) or pCAGGS-ML(HA). Anti-HA antibody was used for precipitation, and lysates and precipitates were stained for HA and TFIIB in Western blots. (D) Coimmunoprecipitation of virus-encoded ML with TFIIB. 293T cells were infected for 20 h at an MOI of 1. Endogenous TFIIB was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and lysates and precipitates were probed with the TFIIB-specific antibody and an M/ML-specific serum in Western blots.

TFIIB overexpression abolishes ML-mediated suppression of IRF3-dependent promoter activation.

We speculated that a negative influence of ML on the activity of TFIIB could be involved in ML-mediated suppression of IFN induction. In this case, an excess of TFIIB might abrogate the IFN antagonism of ML. Therefore, we tested the effect of transfected ML on IRF3-dependent promoter activity in the presence and absence of overexpressed TFIIB with the help of a reporter gene expression assay. This reporter assay employed p55B1CLuc, which encodes firefly luciferase under the control of an artificial promoter containing three IRF3-binding sites (46). p55B1CLuc was transfected into 293T cells together with an expression plasmid for IRF3, and luciferase activity induced by IRF3 was measured 24 h later (Fig. 2). In different combinations, pCAGGS expression plasmids for M, ML, and TFIIB were transfected in addition to reporter and IRF3 expression plasmids. pRLSV40, which constitutively expresses Renilla luciferase, was used as a control reporter plasmid and cotransfected as well. As shown in Fig. 2, IRF3 transfection stimulated the activity of the IRF3-responsive promoter 188-fold compared to the IRF3-negative control. A THOV M expression plasmid that has been shown to have no inhibitory effect on IRF3-mediated IFN-β promoter induction (21) was used as a control. Transfected ML had a strong suppressive effect on IRF3-dependent promoter activation (14-fold reduction), while it decreased the activity of the control promoter only 1.4-fold compared to the M control. The ML-reduced activity of the IRF3-dependent promoter was rescued, however, by overexpression of TFIIB. Also, control promoter activity was restored in the presence of excess TFIIB. TFIIB overexpression alone had a 1.5- to 2-fold activating effect on the expression of both the unstimulated IRF3-responsive promoter and the control promoter (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

Effect of TFIIB overexpression on ML-mediated suppression of IRF3-dependent promoter activation. 293T cells were transfected with luciferase reporter plasmids and expression plasmids for IRF3 (0.5 μg), M or ML (0.1 μg), and TFIIB (0.5 μg). At 24 h posttransfection, cells were lysed and reporter activity was measured. The activity of firefly luciferase under the control of the IRF3-responsive promoter is indicated by black bars, and white bars represent the activity of Renilla luciferase under the control of the constitutively active SV40 promoter. Results of four independent experiments are shown. Expression of IRF3, M, ML, and TFIIB was confirmed by Western blot analysis (data not shown).

ML(S283A/W284A) is unable to bind TFIIB and lacks the capacity to suppress IFN induction.

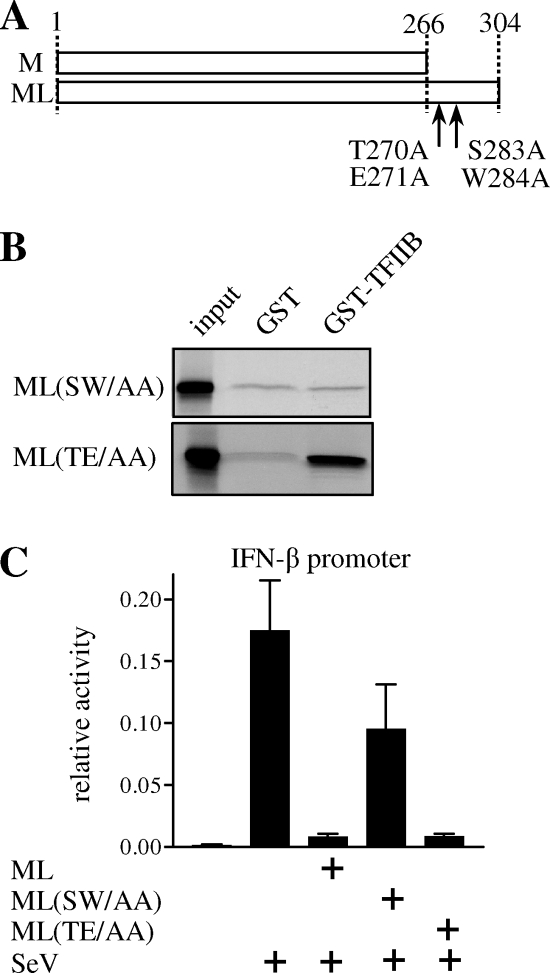

We wished to create an ML mutant deficient in TFIIB interaction. First, by testing ML fragments for interaction with GST-TFIIB, the TFIIB-binding site on ML was confined to aa 257 to 294 (data not shown). We then exchanged several amino acids in this region with alanine and identified ML(S283A/W284A) (Fig. 3A), designated ML(SW/AA), as being completely devoid of TFIIB binding in the GST-TFIIB pull-down assay (Fig. 3B). ML(T270A/E271A), designated ML(TE/AA), was chosen as a control mutant, with two neighboring amino acids being exchanged but TFIIB binding being unaffected. Note that all mutations are in the C-terminal part unique to ML, i.e., outside the M open reading frame (Fig. 3A). To assess the IFN antagonist capacity of ML(SW/AA), we performed luciferase assays with an IFN-β promoter plasmid (46). ML plasmids were cotransfected with the reporter constructs, and the IFN-β promoter was activated 6 h later by infection with SeV. Figure 3C shows that ML(SW/AA) was much less able to suppress IFN-β promoter activation than wild-type ML or ML(TE/AA) was. Although a twofold reduction in promoter activity was still observed with ML(SW/AA), this TFIIB binding-deficient ML construct was thus severely impaired in the ability to suppress IFN induction.

FIG. 3.

Analysis of mutant ML proteins. (A) Schematic representation of THOV M and ML. Numbers indicate amino acid positions. Amino acid changes of ML(SW/AA), at positions 283 and 284, and ML(TE/AA), at positions 270 and 271, are indicated. (B) In vitro binding assay of ML(SW/AA) and ML(TE/AA). Radioactively labeled in vitro-translated ML mutants were assessed for binding to bacterially expressed GST-TFIIB. Autoradiography of input protein and glutathione agarose precipitates separated by SDS-PAGE is shown. (C) IFN antagonist properties of ML(SW/AA) and ML(TE/AA). A reporter plasmid carrying firefly luciferase under the control of the IFN-β promoter was transfected into 293T cells. ML plasmids were cotransfected, and cells were infected with SeV at 6 h posttransfection. Cells were lysed 18 h later, and luciferase activity was measured. Values were normalized to Renilla luciferase expression from cotransfected pRLSV40. Results of three independent experiments are shown.

Recombinant THOVML(S283A/W284A) is unable to antagonize IFN induction.

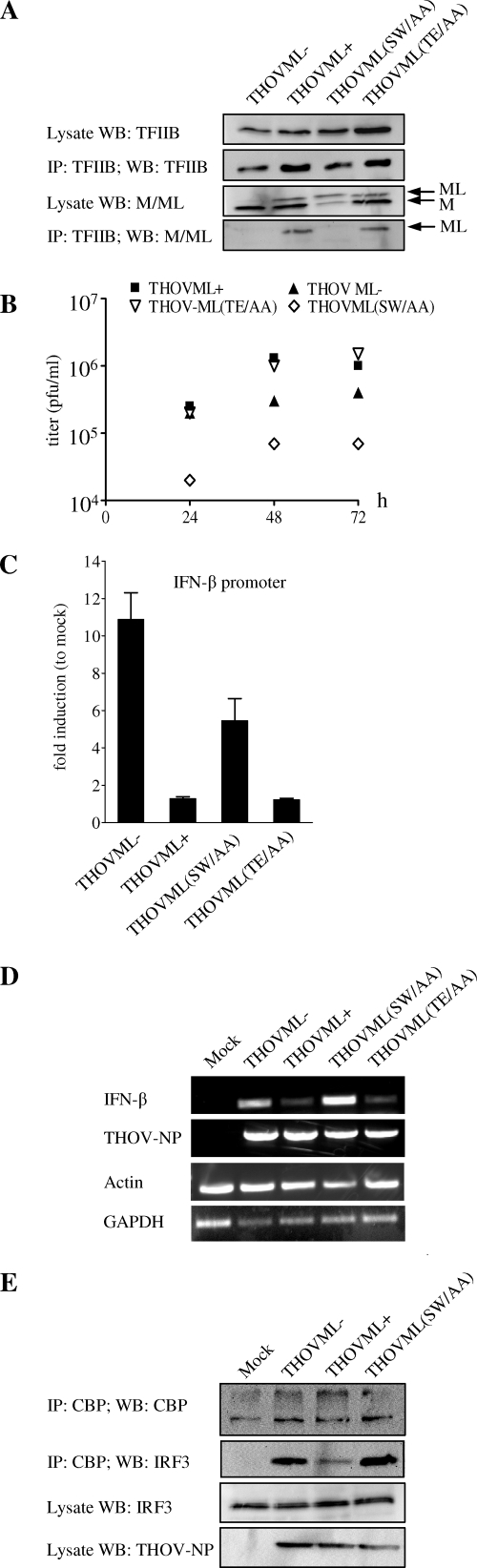

Using a six-plasmid reverse genetic system as described in Materials and Methods, we generated the following recombinant viruses expressing the mutant ML proteins: THOVML(S283A/W284A), called THOVML(SW/AA), and THOVML(T270A/E271A), called THOVML(TE/AA). Also, THOVML− and THOVML+ were newly generated here with the help of the same reverse genetic system. When 293T cells were infected with the recombinant viruses and TFIIB was immunoprecipitated, ML of THOVML(TE/AA), but not that of THOVML(SW/AA), was coprecipitated (Fig. 4A), confirming the in vitro data with mutated ML proteins. We constantly observed reduced M expression in cells infected with several independently generated recombinant THOVML(SW/AA) viruses (Fig. 4A). The reason for M being less abundant in THOVML(SW/AA)-infected cells could be that transcripts of segment 6 of this virus are less efficiently spliced, although the mutations do not affect sites known to be directly involved in M segment mRNA processing (28). When we compared growth of the recombinant viruses in IFN-competent A549 human alveolar epithelial cells (Fig. 4B), THOVML− replicated less efficiently than THOVML+ bearing the functional IFN antagonist. THOVML− showed titers of 3 × 105 PFU/ml after 48 h and 4 × 105 PFU/ml after 72 h, compared to 1.3 × 106 and 106 PFU/ml, respectively, for THOVML+. While THOVML(TE/AA) behaved like THOVML+, THOVML(SW/AA) was more attenuated than THOVML−. Surprisingly, this was not observed when virus stocks were grown in BHK cells, which are known to possess defects in the IFN system (32).

FIG. 4.

Analysis of recombinant viruses encoding mutated ML proteins. (A) Coimmunoprecipitation of ML mutants with TFIIB. Endogenous TFIIB was immunoprecipitated from lysates of infected 293T cells by use of a monoclonal anti-TFIIB antibody and protein A Sepharose. Lysates and precipitates were probed with the TFIIB-specific antibody and M/ML-specific serum in Western blots. (B) Growth kinetics of recombinant viruses. A549 cells were infected with 0.01 PFU/cell, and aliquots of the supernatants were harvested at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. Virus titers in the supernatants were determined by plaque assay. One representative result from three independent experiments is shown. (C) IFN-β promoter stimulation by recombinant viruses expressing mutated ML proteins. A reporter plasmid carrying firefly luciferase under the control of the IFN-β promoter was transfected into 293T cells. The cells were infected with the indicated recombinant viruses at 6 h posttransfection, and luciferase activity was measured 18 h later. Values were normalized to Renilla luciferase expression from cotransfected pRLSV40. Results of four independent experiments are shown. (D) IFN-β induction by recombinant viruses expressing mutated ML proteins. A549 cells were infected with the indicated viruses at an MOI of 1, and IFN-β, γ-actin, GAPDH, and THOV NP transcripts were detected by RT-PCR at 16 h postinfection. (E) CBP-IRF3 interaction in THOV-infected cells. A549 cells were infected for 18 h with the indicated viruses (MOI of 1), and CBP was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates. The precipitates were probed with the anti-CBP antibody and with anti-IRF3 in Western blots. The lysates were stained for IRF3 and THOV NP as controls.

To assess IFN induction by viruses with mutated ML, luciferase assays with the IFN-β reporter were carried out with infected 293T cells. Figure 4C shows that THOVML− and THOVML(SW/AA), but not THOVML+ and THOVML(TE/AA), stimulated the IFN-β promoter, indicating that ML(SW/AA) had lost most of its IFN antagonist function in the virus context. The reduced capacity of THOVML(SW/AA) compared to that of THOVML− to stimulate the IFN-β promoter parallels the finding with transfected ML and SeV-activated IFN-β promoter (Fig. 3C). Finally, to detect endogenous IFN-β induced by the recombinant viruses, A549 cells were infected and IFN-β transcripts were detected by RT-PCR at 16 h postinfection. As shown in Fig. 4D, THOVML(TE/AA) still antagonized IFN induction, whereas THOV-ML(SW/AA) did not. The expression of the viral NP gene confirmed comparable levels of infection. Taken together, Fig. 4C and D clearly demonstrate the necessity of ML-TFIIB interaction for IFN antagonism of THOV. The reduced levels of IFN-β promoter activation in the reporter experiments [ML(SW/AA) transfection compared to no-ML transfection in Fig. 3C and THOVML(SW/AA) infection compared to THOVML− infection in Fig. 4C] suggest, however, an additional TFIIB-independent component of the IFN antagonist action of ML.

We had previously found the interaction of IRF3 with CBP to be disturbed by ML in infected cells (21). Therefore, in order to further characterize ML(SW/AA) with regard to the capacity to impair IRF3 function, we analyzed the interaction of IRF3 with CBP in 293T cells infected with THOVML(SW/AA). CBP was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates, and coprecipitated IRF3 was detected by Western blotting. As controls, noninfected cells and cells infected with THOVML− and THOVML+ were used. Figure 4E shows that virus infection triggered IRF3-CBP association, and only virus-encoded wild-type ML, not ML(SW/AA), was able to counteract this association. This experiment implies that ML also requires TFIIB binding for its impact on IRF3-CBP interaction.

The interaction of ML with TFIIB does not lead to generalized suppression of host gene expression.

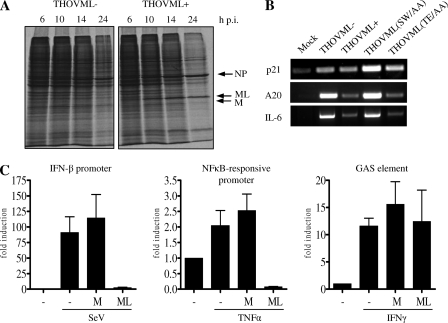

TFIIB is a general transcription factor that recruits RNAPII to the promoter. It is essential for formation of the preinitiation complex (PIC) on the promoters of all protein-encoding genes (11). For a viral IFN antagonist targeting TFIIB, one would therefore expect a strong general effect on host RNAPII transcription. THOV-ML, however, hardly affects constitutively activated promoters, as shown in Fig. 2 for the SV40 promoter. To further study a possible effect of ML on general host gene expression, we infected Vero cells with high multiplicities of infection (MOIs) of THOVML− and THOVML+ and visualized newly made proteins at different times postinfection by incubating the cultures with radioactively labeled amino acids for a period of 90 min. Figure 5A shows that in cells infected with THOVML+, synthesis of cellular proteins declined slightly more rapidly than that in cells infected with THOVML−. However, also in the case of infection with THOVML+, the cells continued to generate cellular proteins longer than would be expected if all TFIIB function was abolished. We concluded that expression of the TFIIB-binding ML protein does not lead to a pronounced host cell shutdown in THOV-infected cells. In agreement with this, in cells infected with THOVML+, expression of the γ-actin or GAPDH gene monitored by RT-PCR was not reduced compared to that in cells infected with THOVML− (Fig. 4D).

FIG. 5.

Promoter specificity of ML action. (A) Protein synthesis in THOV-infected cells. Vero cells were infected with THOVML− or THOVML+ (MOI of 5). At different times postinfection, the cells were radioactively labeled with [35S]methionine for 90 min and lysed directly afterwards. Autoradiographs of lysates separated by SDS-PAGE are shown. Clearly visible bands belonging to viral proteins are marked. (B) Gene expression in THOV-infected cells. The cDNA samples used for Fig. 4D were PCR amplified using p21-, A20-, and IL-6-specific primers. (C) Activation of different promoters in the presence of ML. 293T cells were transfected with firefly luciferase-expressing reporter constructs p125luc (IFN-β promoter), pNFκB-Luc (NF-κB-responsive promoter), and pIRF1-Luc (IFN-γ-activated sequence element). Expression plasmids for M and ML were cotransfected, and the cells were stimulated at 6 h posttransfection with SeV, 0.2 ng/ml TNF-α, and 10 U/ml IFN-γ, respectively. Luciferase activity was determined 18 h later, and values shown are normalized to Renilla luciferase expression from cotransfected pRLSV40. Results of three independent experiments are shown.

Since all inducible promoters we had analyzed so far were activated by IRF3, we wished to test the effect of ML on other, IRF3-independent inducible promoters. Therefore, we assessed the expression of several virus-induced endogenous genes in cells infected with the recombinant THOVs by RT-PCR. An experiment employing cDNA samples from Fig. 4D is shown in Fig. 5B. We found that the expression of the cell cycle-regulating protein p21, which is induced by the transcription factor p53, was not affected by ML. On the other hand, NF-κB-induced A20 (TNFAIP3) and IL-6 genes were much more stimulated by THOVML− or THOVML(SW/AA) than by THOVML+ or THOVML(TE/AA). To assess ML inhibition of NF-κB-induced promoter activation more quantitatively, we performed reporter gene assays with an NF-κB-responsive promoter construct (pNFκB-Luc). In addition, pIRF1-Luc, containing IFN-γ-activated sequence elements from the IRF1 promoter, was used. Upon stimulation with IFN-γ, this promoter is activated by phosphorylated Stat1 molecules. Reporter assays with the IFN-β reporter construct (p125Luc) activated by SeV were performed in parallel in order to demonstrate the activity of transfected ML. Figure 5C shows a strong suppressive effect of ML in these control assays with the IFN-β promoter. Reporter gene expression from the NF-κB-dependent promoter stimulated by TNF-α was negatively affected by ML as well. The fact that ML was able to decrease promoter activation below the level of the non-TNF-α-treated control implies that NF-κB was activated in this assay even without the addition of TNF-α, probably through the transfection procedure. IFN-γ-stimulated luciferase expression from pIRF1-Luc, in contrast, was undisturbed in the presence of transfected ML. Taken together, the experiments characterize ML as a suppressor of IRF3- and NF-κB-dependent promoter activation (IFN-β, A20, and IL-6 genes, p55C1BLuc, p125Luc, and pNFκB-Luc) but not of promoter induction by p53 (p21 gene) or Stat1 (pIRF1-Luc).

It is remarkable that ML, although targeting the general transcription factor TFIIB, inhibits some, but not all, promoters. Antagonists from other viruses that interact with general transcription factors interfere with gene expression in a much more general way. For example, in cells infected with Rift Valley fever virus, host RNA and protein synthesis is decreased dramatically due to interaction of NSs with TFIIH components (7, 30). Similarly, vesicular stomatitis virus provokes a pronounced shutoff in infected cells, with one reason being its matrix protein targeting TFIID (3, 47, 48). Such a strong general effect of ML on host RNAPII transcription would be deleterious for THOV replication. Like influenza viruses, THOV uses the 5′-Cap structures of newly synthesized cellular mRNAs as primers for initiation of the viral transcription by a mechanism called Cap snatching (4, 39, 43). Therefore, in contrast to bunyaviruses, which replicate in the cytoplasm, or vesicular stomatitis virus, which generates the Cap structure by an enzymatic activity of the viral polymerase, THOV has to employ a mechanism to suppress antiviral host defense without affecting the ongoing supply of RNAPII transcripts.

What mechanism could lie behind the promoter specificity of THOV ML? TFIIB not only binds RNAPII, TATA-binding protein (TBP), and core promoter sequences in the PIC but also makes contacts to many promoter-specific activator proteins, including NF-κB and CBP/p300 (1, 13, 29, 41, 44). It therefore seems possible that ML restricts its interference to a special class of promoters (i.e., IRF3/NF-κB-dependent promoters) by targeting TFIIB-activator interactions rather than directly targeting IRF3 or NF-κB functions. This mechanistic model is supported by our experimental data, as follows: (i) overexpression of TFIIB outcompetes the inhibitory effect of ML on IRF3 action (Fig. 2); (ii) in contrast to ML-TFIIB interaction, an interaction of ML with IRF3 could not be detected by coimmunoprecipitation or TAP-ML purification (21; our unpublished data); and (iii) it is fairly unlikely that ML possesses at least three independent activities, i.e., a suppressive effect on IRF3 as well as on NF-κB-dependent promoter activation in addition to its capacity to interact with TFIIB, that are all lost by point mutation (S283A/W284A) of ML. Therefore, we favor a mechanistic model of ML action with an association of ML to TFIIB that specifically affects a selected class of transcription factors, namely, IRF3 and NF-κB. For the IFN-β promoter, in vitro reconstitution experiments have indeed shown that cooperative interactions between enhanceosome components and TFIIB are necessary for efficient PIC formation (23, 24). The fact that ML(SW/AA) was unable to counteract IRF3-CBP association in infected cells (Fig. 4E) raises the possibility that ML uses TFIIB as a scaffold in order to disturb IRF3-CBP interaction. The possibility that interference with IRF3-CBP interaction can be sufficient to abolish IFN induction is demonstrated by adenovirus E1A protein and vIRF1, encoded by human herpesvirus 8, both of which are IFN antagonists that target this interaction (22, 31). Alternatively, one could imagine that ML has a general negative effect on RNAPII function that is particularly apparent at IRF3- and NF-κB-regulated promoters because these promoters for some reason depend more on TFIIB than others do. Yet, to our knowledge, no differences in TFIIB requirement have been described between promoters.

A detailed analysis of transcription factor recruitment to promoters in the presence of ML could characterize the outcome of ML action at the molecular level, while a broad gene expression analysis of THOVML−- versus THOVML+-infected cells would be suited to further define the promoter specificity of ML. Our future studies will aim at the mechanism that this exceptional antagonist employs to counteract IFN induction.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (KO1579/3-7) to G.K.

We thank R. Schneider for providing pGEX-2T-TFIIB(5-316), E. Hoffmann and R. G. Webster for pHW2000, and S. Goodbourn for pIRF1-Luc. We are grateful to Otto Haller and Peter Staeheli for helpful comments on the manuscript.

This work was conducted by C. Vogt in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Ph.D. degree from the Faculty of Biology of the University of Freiburg, Germany.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 3 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abraham, S. E., S. Lobo, P. Yaciuk, H. G. Wang, and E. Moran. 1993. p300, and p300-associated proteins, are components of TATA-binding protein (TBP) complexes. Oncogene 81639-1647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agalioti, T., S. Lomvardas, B. Parekh, J. Yie, T. Maniatis, and D. Thanos. 2000. Ordered recruitment of chromatin modifying and general transcription factors to the IFN-beta promoter. Cell 103667-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahmed, M., and D. S. Lyles. 1998. Effect of vesicular stomatitis virus matrix protein on transcription directed by host RNA polymerases I, II, and III. J. Virol. 728413-8419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albo, C., J. Martin, and A. Portela. 1996. The 5′ ends of Thogoto virus (Orthomyxoviridae) mRNAs are homogeneous in both length and sequence. J. Virol. 709013-9017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Basler, C. F., A. Mikulasova, L. Martinez-Sobrido, J. Paragas, E. Muhlberger, M. Bray, H. D. Klenk, P. Palese, and A. Garcia-Sastre. 2003. The Ebola virus VP35 protein inhibits activation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 777945-7956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Basler, C. F., X. Wang, E. Muhlberger, V. Volchkov, J. Paragas, H. D. Klenk, A. Garcia-Sastre, and P. Palese. 2000. The Ebola virus VP35 protein functions as a type I IFN antagonist. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9712289-12294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Billecocq, A., M. Spiegel, P. Vialat, A. Kohl, F. Weber, M. Bouloy, and O. Haller. 2004. NSs protein of Rift Valley fever virus blocks interferon production by inhibiting host gene transcription. J. Virol. 789798-9806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Booth, T. F., C. R. Davies, L. D. Jones, D. Staunton, and P. A. Nuttall. 1989. Anatomical basis of Thogoto virus infection in BHK cell culture and in the ixodid tick vector, Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. J. Gen. Virol. 701093-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brzozka, K., S. Finke, and K. K. Conzelmann. 2005. Identification of the rabies virus alpha/beta interferon antagonist: phosphoprotein P interferes with phosphorylation of interferon regulatory factor 3. J. Virol. 797673-7681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davies, C. R., L. D. Jones, and P. A. Nuttall. 1986. Experimental studies on the transmission cycle of Thogoto virus, a candidate orthomyxovirus, in Rhipicephalus appendiculatus. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 351256-1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng, W., and S. G. Roberts. 2007. TFIIB and the regulation of transcription by RNA polymerase II. Chromosoma 116417-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dittmann, J., S. Stertz, D. Grimm, J. Steel, A. Garcia-Sastre, O. Haller, and G. Kochs. 2008. Influenza A virus strains differ in sensitivity to the antiviral action of the Mx-GTPase. J. Virol. 823624-3631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felzien, L. K., S. Farrell, J. C. Betts, R. Mosavin, and G. J. Nabel. 1999. Specificity of cyclin E-Cdk2, TFIIB, and E1A interactions with a common domain of the p300 coactivator. Mol. Cell. Biol. 194241-4246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fodor, E., and M. Smith. 2004. The PA subunit is required for efficient nuclear accumulation of the PB1 subunit of the influenza A virus RNA polymerase complex. J. Virol. 789144-9153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hagmaier, K., S. Jennings, J. Buse, F. Weber, and G. Kochs. 2003. Novel gene product of Thogoto virus segment 6 codes for an interferon antagonist. J. Virol. 772747-2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haig, D. A., J. P. Woodall, and D. Danskin. 1965. Thogoto virus: a hitherto undescribed agent isolated from ticks in Kenya. J. Gen. Microbiol. 38389-394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haller, O., M. Frese, D. Rost, P. A. Nuttall, and G. Kochs. 1995. Tick-borne Thogoto virus infection in mice is inhibited by the orthomyxovirus resistance gene product Mx1. J. Virol. 692596-2601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haller, O., G. Kochs, and F. Weber. 2006. The interferon response circuit: induction and suppression by pathogenic viruses. Virology 344119-130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hiscott, J. 2007. Triggering the innate antiviral response through IRF-3 activation. J. Biol. Chem. 28215325-15329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoffmann, E., G. Neumann, Y. Kawaoka, G. Hobom, and R. G. Webster. 2000. A DNA transfection system for generation of influenza A virus from eight plasmids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976108-6113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennings, S., L. Martinez-Sobrido, A. Garcia-Sastre, F. Weber, and G. Kochs. 2005. Thogoto virus ML protein suppresses IRF3 function. Virology 33163-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Juang, Y. T., W. Lowther, M. Kellum, W. C. Au, R. Lin, J. Hiscott, and P. M. Pitha. 1998. Primary activation of interferon A and interferon B gene transcription by interferon regulatory factor 3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 959837-9842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, T. K., T. H. Kim, and T. Maniatis. 1998. Efficient recruitment of TFIIB and CBP-RNA polymerase II holoenzyme by an interferon-beta enhanceosome in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9512191-12196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim, T. K., and T. Maniatis. 1997. The mechanism of transcriptional synergy of an in vitro assembled interferon-beta enhanceosome. Mol. Cell 1119-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King, P., and S. Goodbourn. 1998. STAT1 is inactivated by a caspase. J. Biol. Chem. 2738699-8704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kleffmann, T., D. Russenberger, A. von Zychlinski, W. Christopher, K. Sjolander, W. Gruissem, and S. Baginsky. 2004. The Arabidopsis thaliana chloroplast proteome reveals pathway abundance and novel protein functions. Curr. Biol. 14354-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kochs, G., and O. Haller. 1999. Interferon-induced human MxA GTPase blocks nuclear import of Thogoto virus nucleocapsids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 962082-2086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kochs, G., F. Weber, S. Gruber, A. Delvendahl, C. Leitz, and O. Haller. 2000. Thogoto virus matrix protein is encoded by a spliced mRNA. J. Virol. 7410785-10789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwok, R. P., J. R. Lundblad, J. C. Chrivia, J. P. Richards, H. P. Bachinger, R. G. Brennan, S. G. Roberts, M. R. Green, and R. H. Goodman. 1994. Nuclear protein CBP is a coactivator for the transcription factor CREB. Nature 370223-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le May, N., S. Dubaele, L. Proietti De Santis, A. Billecocq, M. Bouloy, and J. M. Egly. 2004. TFIIH transcription factor, a target for the Rift Valley hemorrhagic fever virus. Cell 116541-550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lin, R., P. Genin, Y. Mamane, M. Sgarbanti, A. Battistini, W. J. Harrington, Jr., G. N. Barber, and J. Hiscott. 2001. HHV-8 encoded vIRF-1 represses the interferon antiviral response by blocking IRF-3 recruitment of the CBP/p300 coactivators. Oncogene 20800-811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacDonald, M. R., E. S. Machlin, O. R. Albin, and D. E. Levy. 2007. The zinc finger antiviral protein acts synergistically with an interferon-induced factor for maximal activity against alphaviruses. J. Virol. 8113509-13518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayer, D., S. Baginsky, and M. Schwemmle. 2005. Isolation of viral ribonucleoprotein complexes from infected cells by tandem affinity purification. Proteomics 54483-4487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mibayashi, M., L. Martinez-Sobrido, Y. M. Loo, W. B. Cardenas, M. Gale, Jr., and A. Garcia-Sastre. 2007. Inhibition of retinoic acid-inducible gene I-mediated induction of beta interferon by the NS1 protein of influenza A virus. J. Virol. 81514-524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavlovic, J., O. Haller, and P. Staeheli. 1992. Human and mouse Mx proteins inhibit different steps of the influenza virus multiplication cycle. J. Virol. 662564-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pichlmair, A., J. Buse, S. Jennings, O. Haller, G. Kochs, and P. Staeheli. 2004. Thogoto virus lacking interferon-antagonistic protein ML is strongly attenuated in newborn Mx1-positive but not Mx1-negative mice. J. Virol. 7811422-11424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puig, O., F. Caspary, G. Rigaut, B. Rutz, E. Bouveret, E. Bragado-Nilsson, M. Wilm, and B. Seraphin. 2001. The tandem affinity purification (TAP) method: a general procedure of protein complex purification. Methods 24218-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Randall, R. E., and S. Goodbourn. 2008. Interferons and viruses: an interplay between induction, signalling, antiviral responses and virus countermeasures. J. Gen. Virol. 891-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Siebler, J., O. Haller, and G. Kochs. 1996. Thogoto and Dhori virus replication is blocked by inhibitors of cellular polymerase II activity but does not cause shutoff of host cell protein synthesis. Arch. Virol. 1411587-1594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wagner, E., O. G. Engelhardt, S. Gruber, O. Haller, and G. Kochs. 2001. Rescue of recombinant Thogoto virus from cloned cDNA. J. Virol. 759282-9286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang, I. M., J. C. Blanco, S. Y. Tsai, M. J. Tsai, and K. Ozato. 1996. Interferon regulatory factors and TFIIB cooperatively regulate interferon-responsive promoter activity in vivo and in vitro. Mol. Cell. Biol. 166313-6324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wathelet, M. G., C. H. Lin, B. S. Parekh, L. V. Ronco, P. M. Howley, and T. Maniatis. 1998. Virus infection induces the assembly of coordinately activated transcription factors on the IFN-beta enhancer in vivo. Mol. Cell 1507-518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weber, F., O. Haller, and G. Kochs. 1996. Nucleoprotein viral RNA and mRNA of Thogoto virus: a novel “cap-stealing” mechanism in tick-borne orthomyxoviruses? J. Virol. 708361-8367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia, C., S. Watton, S. Nagl, J. Samuel, J. Lovegrove, J. Cheshire, and P. Woo. 2004. Novel sites in the p65 subunit of NF-kappaB interact with TFIIB to facilitate NF-kappaB induced transcription. FEBS Lett. 561217-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yoneyama, M., and T. Fujita. 2007. RIG-I family RNA helicases: cytoplasmic sensor for antiviral innate immunity. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 18545-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yoneyama, M., W. Suhara, Y. Fukuhara, M. Fukuda, E. Nishida, and T. Fujita. 1998. Direct triggering of the type I interferon system by virus infection: activation of a transcription factor complex containing IRF-3 and CBP/p300. EMBO J. 171087-1095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yuan, H., S. Puckett, and D. S. Lyles. 2001. Inhibition of host transcription by vesicular stomatitis virus involves a novel mechanism that is independent of phosphorylation of TATA-binding protein (TBP) or association of TBP with TBP-associated factor subunits. J. Virol. 754453-4458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yuan, H., B. K. Yoza, and D. S. Lyles. 1998. Inhibition of host RNA polymerase II-dependent transcription by vesicular stomatitis virus results from inactivation of TFIID. Virology 251383-392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]