Abstract

SopB is a virulence factor of Salmonella encoded by SPI-5. Salmonella sopB deletion mutants are impaired in their ability to cause local inflammatory responses and fluid secretion into the intestinal lumen and also can enhance the immunogenicity of a vectored antigen. In this study, we evaluated the effects on immunogenicity and the efficacy of a sopB deletion mutation on two Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine strains with different attenuating mutations expressing a highly antigenic α-helical region of the Streptococcus pneumoniae surface protein PspA from an Asd+-balanced lethal plasmid. After oral administration to mice, the two pairs of strains induced high levels of serum antibodies specific for PspA as well as to Salmonella antigens. The levels of antigen-specific serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) and mucosal IgA were higher in mice immunized with sopB mutants. Enzyme-linked immunospot assay results indicated that the spleen cells from mice immunized with a sopB mutant showed higher interleukin-4 and gamma interferon secretion levels than did the mice immunized with the isogenic sopB+ strain. The sopB mutants also induced higher numbers of CD4+ CD44hi CD62Lhi and CD8+ CD44hi CD62Lhi central memory T cells. Eight weeks after primary oral immunization, mice were challenged with 100 50% lethal doses of virulent S. pneumoniae WU2. Immunization with either of the sopB mutant strains led to increased levels of protection compared to that with the isogenic sopB+ parent. Together, these results demonstrate that the deletion of sopB leads to an overall enhancement of the immunogenicity and efficacy of recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccine strains.

Recombinant attenuated Salmonella vaccines (RASVs) have been used to induce mucosal and systemic immunity either against itself or to a vectored heterologous antigen (30, 31). It is clear from previous studies that the mode of attenuation (10), antigen burden (12), and the expression system (11, 19, 21) can have a profound effect on the immune response to a vectored antigen. Many attenuating mutations were found to reduce Salmonella survival due to host-induced stresses and/or reduce colonization of lymphoid effector tissues leading to less than ideal immunogenicity (16, 48). An ideal Salmonella vaccine strain should exhibit wild-type abilities to withstand all stresses (enzymatic, acid, osmotic, ionic, etc.) and host defenses (bile, antibacterial peptides, etc.) encountered following oral or intranasal immunization and should exhibit wild-type abilities to colonize and invade host lymphoid tissues while remaining avirulent. Achieving maximal immune responses to a foreign antigen is directly correlated with the amount of the antigen produced, and thus, it is important that the immunizing strain produce adequate levels of antigen. However, for RASVs, this need must be weighed against the fact that high-level antigen production can be a drain on the energy resources of the cell, leading to reduced growth rates and a compromised ability to colonize and stimulate effector lymphoid tissues (55). We have addressed these problems by exporting the antigen outside of the attenuated Salmonella (19), by delaying expression of the attenuated phenotype (6; unpublished results), and by heterologous antigen synthesis (53) until the vaccine strain has colonized host lymphoid tissues. In addition, we have developed the Asd+-balanced lethal system for plasmid maintenance, obviating the need for antibiotic resistance markers (32).

The SopB protein in Salmonella, encoded by SPI-5, is secreted and translocated into the cytosol through the SPI-1-encoded type III secretion system (60). SopB has an inositol phosphate phosphatase activity which affects cytoskeletal rearrangement, host-cell invasion and chloride homeostasis (34). sopB mutants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium are attenuated in their ability to cause gastroenteritis in calves (59), but not for invasion of host tissues (39). In addition, sopB mutants of both Salmonella enterica serovars Typhimurium and Dublin are similarly attenuated in their ability to induce inflammatory responses and fluid secretion in bovine ileal loops (13, 42). In the context of a vaccine, these features may be beneficial in reducing or eliminating reactogenicity and diarrhea sometimes observed in clinical trial volunteers receiving live attenuated bacterial vaccines (17, 47, 49-51). The SopB protein can also protect infected cells from apoptosis by sustained activation of Akt, which may be helpful for Salmonella survival in host tissues but will necessarily affect host immune responses (22). A recent study showed that introduction of a sopB mutation into several different attenuated Salmonella strains led to enhanced immune responses in mice to a vectored test antigen, β-galactosidase (27). Based on these observations, we evaluated the effects of a sopB deletion mutation on the performance of our Salmonella vaccine strains.

Streptococcus pneumoniae is the principle cause of bacterial pneumonia in children and adults and is also a major cause of otitis media, bacterial meningitis, and septicemia (2). Developing an inexpensive, safe, and effective vaccine against this pathogen is still in urgent demand. Pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA) is an important virulence factor found on the surface of all pneumococci (29). It is a protective antigen in animal models and is immunogenic in humans (2, 58). Our previous work has demonstrated that mice immunized with an RASV expressing PspA are protected against challenge with virulent S. pneumoniae WU2 (20).

In this work, we evaluated the effects of a sopB mutation on two different RASV strains with different modes of attenuation on their ability to deliver PspA. We analyzed humoral, mucosal, and cellular immune responses against both the bacterial vector and PspA and protective immunity against challenge with S. pneumoniae WU2 in immunized mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice.

Female BALB/c mice, 6 to 7 weeks old, were obtained from the Charles River Laboratories. All animal procedures were approved by the Arizona State University Animal Care and Use Committees. Mice were acclimated for 7 days after arrival before starting the experiments.

Bacterial strains, plasmids, media, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. Serovar Typhimurium vaccine strains were derived from the highly virulent parent strain UK-1 (5). Bacteriophage P22HTint was used for generalized transduction (41, 43). Serovar Typhimurium cultures were grown at 37°C in LB broth or on LB agar with or without 0.05% arabinose (1). Diaminopimelic acid (DAP) was added (50 μg/ml) for the growth of Δasd strains (32). LB agar without NaCl and containing 5% sucrose was used for sacB gene-based counterselection in allelic exchange experiments. S. pneumoniae WU2 was cultured on brain heart infusion agar containing 5% sheep blood or in Todd-Hewitt broth plus 0.5% yeast extract (2). Growth on MOPS (morpholinepropanesulfonic acid) minimal medium with and without 10 μg/ml p-aminobenzoic acid was used to confirm the phenotype of pabA pabB mutants.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Genotype or relevant characteristics | Source or reference |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| S. enterica serovar Typhimurium UK-1 | ||

| χ9241 | ΔpabA1516 ΔpabB232 ΔasdA16 ΔaraBAD23 ΔrelA198::araC PBADlacI TT | 53 |

| χ9277 | χ9241 ΔsopB1925 | This study |

| χ9373 | Δpmi-2426 Δ(gmd-fcl)-26 ΔPfur81::TT araC PBADfur ΔPcrp527::TT araC PBADcrp ΔasdA21::TT araC PBADc2 ΔaraE25 ΔaraBAD23 ΔrelA198::araC PBADlacI TT | Lab collection |

| χ9402 | χ9373 ΔsopB1925 | This study |

| S. pneumoniae WU2 | Wild-type virulent, encapsulated type 3 | 2 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pMEG-375 | sacRB mobRP4 oriR6K; Cmr Apr | 8 |

| pYA3733 | pMEG-375 with ΔsopB1925 mutation | This study |

| pYA3493 | Plasmid Asd+; pBRori β-lactamase signal sequence-based periplasmic secretion plasmid | 20 |

| pYA3634 | 0.7-kb DNA encoding the α-helical region of PspA from amino acid 3 to amino acid 257 in pYA3493 | 4 |

| pYA4088 | 852-bp DNA encoding the α-helical region of PspA from amino acid 3 to amino acid 285 in pYA3493 | 54 |

Strain construction and characterization.

The ΔsopB1925 mutation deletes the ribosome binding site and the first 549 out of a total of 562 codons of sopB. It was introduced into serovar Typhimurium χ9241 by allelic exchange using the suicide vector pYA3733 to generate χ9277. The presence of the 1,665-bp deletion was confirmed by PCR with a primer set flanking sopB (5′-ACATGCATGCGGCATACACACACCTGTATAACA and 5′-TTCCCCCGGGGCAGTATTGTCTGCGTCAGCG). The presence of both the ΔpabA1516 and ΔpabB232 mutations in Salmonella was verified by the inability of the strains to grow in MOPS minimal medium without p-aminobenzoate. Chrome azurol S (432) plates were used to confirm the constitutive synthesis of siderophores characteristic of fur mutants. The presence of the ΔasdA16 mutation was confirmed by the inability of strains to grow in LB media without DAP (32). The ΔaraBAD23 mutation was verified by a white colony phenotype on MacConkey agar supplemented with 1% arabinose. The mannose-dependent, reversibly rough lipopolysaccharide (LPS) phenotype of pmi mutants was confirmed by growth in nutrient broth with and without mannose. LPS profiles were then examined as previously described (15).

Determination of plasmid stability.

Plasmid stability was determined as previously described (24). Three milliliters of LB broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml DAP was inoculated with 3 μl (1:1,000) of the overnight culture of RASV strains harboring pYA3493, pYA4088, or pYA3634. Inoculated cultures were grown standing for 14 h (approximately 10 generations); afterwards, 3 μl was taken and inoculated into 3 ml of LB broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml DAP (1:1,000). Newly inoculated cultures were grown standing for 14 h. This process was repeated for five consecutive days (approximately 50 generations). To determine the proportions of cells retaining the Asd+ plasmids, from each culture (for five consecutive days) after 14 h of growth, dilutions of 10−5 and 10−6 were plated onto LB agar plates supplemented with 50 μg/ml DAP and grown overnight. The following morning, 100 colonies from each vaccine construct were picked and patched onto LB agar plates that were either left unsupplemented or supplemented with 50 μg/ml DAP. Colonies that grew on LB agar only or on LB agar supplemented with 50 μg/ml DAP were counted, and the percentage of clones retaining the plasmids was determined. At the same time, 10 clones from each day's plating were picked, and the bacteria were grown on LB media to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8 for sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and immunoblot analysis to confirm the expression of the correct size and amount of PspA by each clone.

SDS-PAGE and immunoblot analyses.

Protein samples were boiled for 5 min and then separated by SDS-PAGE. For immunoblotting, proteins separated by SDS-PAGE were transferred electrophoretically to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 3% skim milk in 10 mM Tris-0.9% NaCl (pH 7.4) and incubated with rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for PspA (University of Alabama at Birmingham) or anti-GroEL (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) antibodies and then with an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) (Sigma). Immunoreactive bands were detected by the addition of BCIP (5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolylphosphate)-nitroblue tetrazolium solution (Sigma). The reaction was stopped after 2 min by washing with large volumes of deionized water several times.

Immunization of mice.

RASV strains were grown statically overnight in LB broth with 0.05% arabinose at 37°C. The following day, 1 ml of the overnight culture was inoculated into 100 ml of LB broth with 0.05% arabinose and grown with aeration at 37°C to an optical density at 600 nm of 0.8 to 0.9. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at room temperature (6,000 × g for 15 min), and the pellet resuspended in 1 ml of buffered saline with gelatin (BSG). To determine titer, serial dilutions of the RASV strains were plated onto MacConkey agar supplemented with 1% lactose. Mice were orally inoculated with 20 μl of BSG containing 1 × 109 CFU of the RASV strain to be tested or were mock vaccinated with BSG. At days 7, 14, and 21 after oral immunization, spleen, Peyer's patch, mesenteric lymph node, and liver samples were collected, and each sample was homogenized to a total volume of 1 ml in BSG. Tissue samples were serially diluted in BSG, and 0.1 ml of the dilutions was plated onto MacConkey agar to determine the numbers of viable bacteria. An aliquot of each tissue sample was enriched in selenite cysteine broth by incubating for 14 h at 37°C at 200 rpm. Samples that were negative by direct plating and positive by enrichment were recorded as <10 CFU/g. Samples that were negative by both direct plating and enrichment were recorded as 0 CFU. Blood samples were obtained by mandibular vein puncture at biweekly intervals. Following centrifugation, the serum was removed from the whole-blood samples and stored at −20°C. Vaginal-wash samples were collected at biweekly intervals and stored at −20°C.

Antigen preparation.

rPspA protein and serovar Typhimurium outer membrane proteins (SOMPs) were purified as described previously (20). Serovar Typhimurium LPS was obtained from Sigma. The rPspA clone was a kind gift from Susan Hollingshead at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

ELISA.

An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used to assay antibodies in serum to serovar Typhimurium LPS, SOMPs, and rPspA and in vaginal washes to rPspA. Polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom microtiter plates (Dynatech Laboratories Inc., Chantilly, VA) were coated with 100 ng/well of LPS, SOMPs, or purified rPspA. Antigens suspended in sodium carbonate-bicarbonate coating buffer (pH 9.6) were applied with 100-μl volumes in each well. The coated plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Free binding sites were blocked with a blocking buffer (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS; pH 7.4], 0.1% Tween 20, and 1% bovine serum albumin). A 100-μl volume of serially diluted sample was added to individual wells in triplicate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Plates were treated with biotinylated goat anti-mouse IgG, IgG1, IgG2a, or IgA (Southern Biotechnology Inc., Birmingham, AL). Wells were developed with a streptavidin-alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Southern Biotechnology, Inc.), followed by p-nitrophenylphosphate substrate (Sigma) in diethanolamine buffer (pH 9.8). Color development (absorbance) was recorded at 405 nm using an automated ELISA plate (model EL311SX; Biotek, Winooski, VT). Absorbance readings that were 0.1 higher than PBS control values were considered positive.

IL-4 and IFN-γ ELISPOT assays.

At week 8, spleen cells were harvested from three mice from each group. Enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assays were performed as previously described (44). Briefly, polyvinylidene difluoride membrane plates (Millipore, Bedford, MA) were prewetted with ethanol, washed with sterile H2O, and coated with 100 μl containing anti-interleukin-4 (IL-4) or anti-gamma interferon (IFN-γ) monoclonal antibodies (MAb) (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) at 5 μg/ml in PBS overnight at 4°C. The wells were washed with PBS and blocked with RPMI medium with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Next, 50 μl of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 1% HEPES, with or without rPspA at 5 μg/ml and 50 μl of cells (1,000,000 per well) in cell medium were added per well and incubated in the plates overnight in 5% CO2 at 37°C. Concanavalin A at 2 μg/ml was used as a positive control. The next day, the cell suspensions were discarded and the plates washed with PBS. Biotinylated anti-IL-4 or anti-IFN-γ MAb (BD Pharmingen) at 0.5 μg/ml in PBS with 1% FCS was added and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. After washing with PBS, 100 μl/well of avidin peroxidase diluted 1:1,000 (vol/vol) in PBS-Tween 20 containing 1% FCS was added and followed by incubation for 1 h at room temperature. 3-Amino-9-ethylcarbazole substrate (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) was prepared according to manufacturer's specifications, and 100 μl of substrate was added per well. Spots were developed for 15 min at room temperature. Plates were dried and analyzed by using an automated CTL ELISPOT reader system (Cellular Technology LTD, Cleveland, OH).

Cell preparations and fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS).

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from spleens, washed twice, and filtered through a fine Nitex membrane. The samples were then cultured in cell medium (RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, 2 mM l-glutamine, 100 IU/ml penicillin and streptomycin, and 1% HEPES) for 12 h with rPspA antigen (5 μg/ml). The following reagents were used for flow cytometric analysis: unconjugated anti-CD16/32, anti-CD4 phycoerythrin (PE)-cy7, anti-CD44 fluorescein isothiocyanate, and anti-CD62L PE-cy5. Anti-CD8 PE was purchased from BD Pharmingen and the other antibodies were purchased from eBioscience, San Diego, CA. Staining was performed in PBS-1% calf serum in the presence of purified anti-CD16/32 at saturation to block nonspecific staining via FcRII/III. All analyses were done on a FACS500 (BD Biosciences) using CXP software for data analysis.

Measurement of cytokine concentrations.

Cytokine concentrations were determined using the Bio-Plex protein array system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Cytokine-specific antibody-coated beads (Bio-Rad) were used for these experiments. The assay quantifies cytokines over a broad range (2 to 32,000 pg/ml) and eliminates multiple dilutions of high-concentration samples. The samples were prepared and incubated with antibody-coupled beads for 1 h with continuous shaking. The beads were washed three times with wash buffer to remove unbound protein and then incubated with biotinylated detection cytokine-specific antibody for 1 h with continuous shaking. The beads were washed once more and were then incubated with streptavidin-phycoerythrin for 10 min. After incubation, the beads were washed and resuspended in assay buffer, and the constituents of each well were drawn up into the flow-based Bio-Plex suspension array system, which identifies each different color bead as a population of protein and quantifies each protein target based on secondary antibody fluorescence. Cytokine concentrations were automatically calculated by Bio-Plex Manager software using a standard curve derived from a recombinant cytokine standard. Many readings were made on each bead set, further validating the results.

Pneumococcal challenge.

At week 8, mice were challenged by intraperitoneal injection with 2 × 104 CFU of S. pneumoniae WU2 in 200 μl of BSG (33). The 50% lethal dose (LD50) of S. pneumoniae WU2 in BALB/c mice was 2 × 102 CFU (data not shown). Challenged mice were monitored daily for 30 days.

Statistical analysis.

Data were expressed as means ± standard errors. The means were evaluated with one-way analysis of variance and least-significant-difference test for multiple comparisons among groups. FACS results were evaluated using the Pearson chi-square test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Construction of the ΔsopB RASV strain χ9277.

To evaluate the effect of sopB in RASV, we developed a set of isogenic strains that are attenuated by deletions in the pabA and pabB genes (57) and carry an asdA deletion to facilitate use of the Asd+-balanced lethal plasmid encoding our test antigen. The ΔsopB1925 deletion mutation was introduced into the ΔpabA ΔpabB ΔasdA strain χ9241 to yield strain χ9277. The presence of the sopB deletion was confirmed by PCR (data not shown).

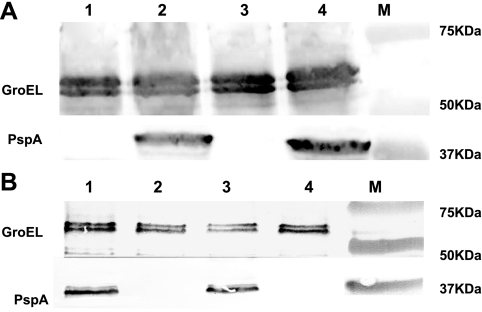

Expression of rPspA in Salmonella.

Recombinant plasmids pYA3493 and pYA3634 (Table 1) were introduced into RASV strains χ9241 and χ9277 by electroporation. The resulting strains were evaluated for plasmid stability, and the plasmids were maintained after 50 generations of growth in the presence of DAP. LPS profiles were compared before and after introduction of the plasmids, and no differences were observed (data not shown). The RASV strains χ9241(pYA3634) and χ9277(pYA3634) expressed a 37-kDa protein that reacted to specifically a rabbit anti-rPspA (Rx1) antibody, as expected (Fig. 1A). PspA expression levels were similar in both strains.

FIG. 1.

Western blot showing expression of PspA (Rx1) by different S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains. Cell lysates of S. enterica serovar Typhimurium strains expressing PspA (Rx1) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the proteins transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, which was subsequently probed with polyclonal antibody specific for PspA or GroEL. (A) Lane 1, χ9241(pYA3493); lane 2, χ9241(pYA3634); lane 3, χ9277(pYA3493); lane 4, χ9277(pYA3634); M, molecular-mass markers are labeled. (B) Lane 1, χ9373(pYA4088); lane 2, χ9373(pYA3493); lane 3, χ9402(pYA4088); lane 4, χ9402(pYA3493); M, molecular-mass markers are labeled.

Colonization of mouse tissues and immune responses in mice after oral immunization with RASV expressing PspA.

BALB/c mice were orally immunized with a single dose of strain χ9241(pYA3634) (1.2 × 109 CFU), χ9277(pYA3634) (1.1 × 109 CFU), χ9241(pYA3493) (1.3 × 109 CFU), or χ9277(pYA3493) (1.1 × 109 CFU). All immunized mice survived, and no signs of disease were observed in the immunized mice during the entire experimental period. We evaluated χ9241(pYA3634) and χ9277(pYA3634) for colonization of mouse tissues on days 7, 14, and 21 postimmunization and found no difference between the strains in their abilities to colonize Peyer's patches, mesenteric lymph nodes, liver, and spleen (data not shown).

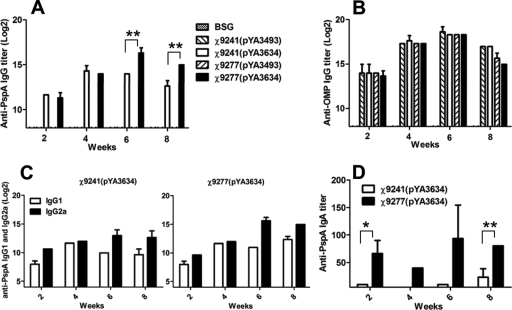

There were no significant differences in the PspA-specific serum IgG responses elicited by immunization by either PspA-expressing strain over the first 4 weeks (Fig. 2A). However, by week 6, mice immunized with the sopB deletion strain χ9277(pYA3634) developed significantly higher IgG titers against PspA than did the isogenic sopB+ strain χ9241(pYA3634) (P < 0.01). Serum IgG responses to Salmonella LPS (not shown) and SOMPs (Fig. 2B) were not significantly different between strains over the course of the experiment. IgA antibody titers in vaginal washes to rPspA were significantly higher in χ9277(pYA3634)-immunized mice than in χ9241(pYA3634)-immunized mice at 2 weeks (P < 0.05) and 8 weeks (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2D). No anti-PspA antibody was detected in sera or vaginal washes from mice immunized with the control strains or with BSG.

FIG. 2.

Serum IgG responses to rPspA (A) and to SOMPs (B) as determined by ELISA. The data represent IgG antibody levels induced in mice orally immunized with χ9241(pYA3634), χ9241(pYA3493), χ9277(pYA3634), or χ9277(pYA3493) at the indicated weeks after immunization. (C) Serum IgG1 and IgG2a responses to rPspA. The data represent ELISA results determining IgG1 and IgG2a subclass antibody levels to rPspA in sera of BALB/c mice at the indicated weeks after immunization. (D) Vaginal-wash IgA responses to rPspA. The data represent ELISA results determining IgA antibody levels to rPspA in vaginal washes of BALB/c mice orally immunized with χ9241(pYA3634) (expressing rPspA) or χ9277(pYA3634) (expressing rPspA) at the indicated weeks after immunization. *, compared to χ9241(pYA3634)-immunized mice, the P value was <0.05; **, compared to χ9241(pYA3634)-immunized mice, the P value was <0.01.

IgG isotype analyses.

The serum immune responses to rPspA were further examined by measuring the levels of IgG isotype subclasses IgG1 and IgG2a. The Th1 cells direct cell-mediated immunity and promote class switching to IgG2a, and Th2 cells provide potent help for B-cell antibody production and promote class switching to IgG1 (7, 14). Th1-type dominant immune responses are frequently observed after immunization with attenuated Salmonella strains (35-37). Although the IgG1 levels were almost the same as IgG2a levels in the early phase, the level of anti-rPspA IgG2a isotype antibodies gradually increased after 6 weeks (Fig. 2C). At 8 weeks postimmunization, the ratio of IgG2a to IgG1 was 8:1 for χ9241(pYA3634)-immunized mice and 6.4:1 for χ9277(pYA3634)-immunized mice, indicating that a Th1 response was induced by both strains.

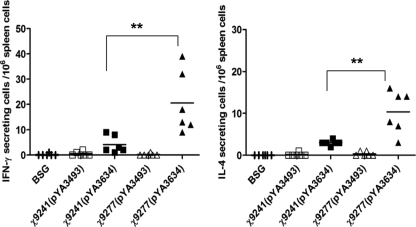

Antigen-specific stimulation of IL-4 or IFN-γ production.

The ELISPOT system was used to compare rPspA antigen stimulations of IL-4 and IFN-γ production by splenic lymphocytes isolated from immunized and control mice. Mice immunized with strain χ9277(pYA3634) showed a significant increase in both IFN-γ and IL-4 production compared to mice immunized with χ9241(pYA3634) (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Antigen-specific stimulation of IL-4 or IFN-γ production. Splenectomies were performed on BALB/c mice sacrificed at 8 weeks following vaccination; BSG controls were also included. Splenocytes were harvested from three mice per group, pooled, and plated onto a precoated antimouse IL-4 or IFN-γ MAb 96-well format at dilutions of 1 × 106 (in triplicate) in RPMI medium containing IL-2 and PspA antigen as shown. Unstimulated (mock) splenocytes were also plated for each group. After 12 h at 37°C, ELISPOT analysis was performed (described in Materials and Methods). The results are presented as ELISPOTs per million splenocytes minus background ELISPOTs from unpulsed mock controls. The P value was <0.01 when comparing χ9241(pYA3634) with χ9277(pYA3634) for secretion levels of both IL-4 and IFN-γ. **, P < 0.01.

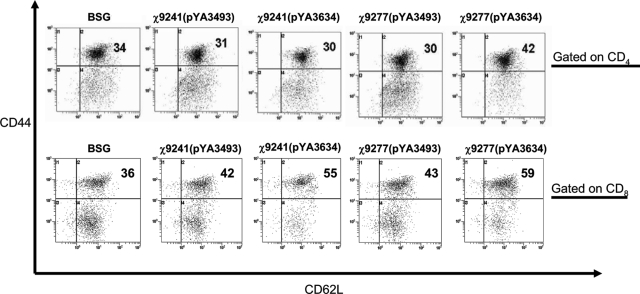

Evaluation of CD4+ CD44hi CD62Lhi and CD8+ CD44hi CD62Lhi central memory T cells.

The long-term protective efficacy of vaccines depends primarily on the induction of memory responses. It has been suggested that the CD4+ CD44hi CD62Lhi and CD8+ CD44hi CD62Lhi central memory T cells play a central role in the recall response (25). Therefore, we evaluated the effect of ΔsopB on the stimulation of a memory T-cell response.

Eight weeks after immunization, we isolated spleen samples from each group of mice. Splenic cells were stimulated with rPspA and then examined by FACS analysis for T-cell markers indicative of memory cells. We observed a significant increase in the percentages of both CD4+ CD44hi CD62Lhi and CD8+ CD44hi CD62Lhi cells in mice immunized with χ9277(pYA3634), compared to the percentages of those in mice in the other three groups (P < 0.01) (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Flow cytometric analysis of polyclonal central memory T cells. Single-cell suspensions were prepared from pooled spleens derived from three mice per group and then stimulated for 12 h with rPspA antigen (5 μg/ml). Splenic T cells were gated on CD4 and CD8 markers separately and analyzed for the expression of the activation markers CD44 and CD62L. Data were derived from 100,000 events acquired from each sample. Representative results are shown from two experiments. Numbers are percentages of CD4+ CD44hi CD62Lhi and CD8+ CD44hi CD62Lhi cells.

Status of systemic cytokine environment.

Six weeks after immunization, sera from each group of mice were subjected to Bio-Plex analysis. The secretion profiles were compared (data not shown). With the exception of IFN-γ, sera from all immunized mice showed increased levels of cytokine concentration compared to the mock immunized group (P < 0.05). The concentrations of both Th1 cytokines (IL-2, IL-12, TNF-α) and Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-5, IL-10) have increased in the χ9277(pYA3634) group, compared to the χ9241(pYA3634) group, especially for IL-4 and IL-12 (P < 0.05), indicating that inclusion of sopB mutation did stimulate cytokine secretion.

Evaluation of protective immunity.

To evaluate the effect of sopB on the ability of the RASV expressing PspA to induce protective immunity, mice were challenged by the intraperitoneal route with 2 × 104 CFU (100 LD50s) with S. pneumoniae WU2 8 weeks after receiving a single vaccine dose. Immunization with χ9277(pYA3634) induced greater protective immunity than did immunization with χ9241(pYA3634) (Table 2). We do not achieve statistical significance between the SopB+ and SopB− strains, although in the case of χ9277(pYA3634) versus χ9241(pYA3634), the results approach statistical significance (P = 0.06). All of the mock-immunized mice and mice immunized with control strains χ9241(pYA3493) and χ9277(pYA3493) succumbed to S. pneumoniae infection.

TABLE 2.

Oral immunization with PspA-expressing Salmonella strains protects BALB/c mice against intraperitoneal challenge with capsular type 3 S. pneumoniae WU2

| Vaccine straina | PspA expressionb | No. of challenged mice | No. of days to death (no. of mice)c | Protection rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSG | NA | 10 | 2 (9), 3 (1) | 0 |

| χ9241(pYA3493) | − | 13 | 2 (10), 3 (3) | 0 |

| χ9277(pYA3493) | − | 13 | 2 (11), 3 (2) | 0 |

| χ9241(pYA3634) | + | 13 | 2 (6), 3 (1), 4 (3), >15 (3) | 23 |

| χ9277(pYA3634) | + | 13 | 2 (3), 3 (1), 4 (2), 5 (1), >15 (6) | 46d |

Mice were orally immunized with a single dose of the indicated vaccine strains.

+, PspA expressed; −, PspA not expressed; NA, not applicable.

Eight weeks after the primary oral immunization, mice were challenged in two experiments with approximately 2 × 104 CFU of S. pneumoniae WU2. Both experiments gave similar results, and the data have been pooled for presentation and analysis. The LD50 of WU2 in nonimmunized BALB/c mice is 2 × 102 (data not shown).

Compared with χ9241(pYA3634)-immunized mice, the P value was 0.06; compared with χ9277(PYA3493)-immunized mice, the P value was <0.01.

Evaluation of the sopB mutation in another attenuated RASV strain.

To address the broader applicability of a ΔsopB mutation, we constructed another set of isogenic strains, differing only at sopB. The other set of strains is derived from χ9373, which is attenuated by deletion of the pmi gene, in addition to a unique delayed attenuation phenotype in which the fur gene is under the control of the arabinose-regulated PBAD promoter (4). The strains have also been modified such that expression of the crp gene, a global regulator of virulence and carbon metabolism (3), is also controlled by the PBAD promoter. In this system, the crp and fur genes are expressed when grown in LB broth containing arabinose, resulting in a wild-type phenotype at the time of host immunization. Once the strain invades host tissues where arabinose is limiting, expression of these genes is shut off, resulting in an attenuated phenotype. The attenuating pmi mutation works in a similar fashion. The pmi gene encodes 6-phosphomannose isomerase that interconverts fructose-6-P and mannose-6-P (45). Because mannose is required for O antigen synthesis, Δpmi mutants grown in the presence of mannose synthesize complete O antigen. Synthesis of O antigen ceases upon infection of a mammalian host due to the fact that no free nonphosphorylated mannose exists in host tissues (4). This leads to a rough phenotype increasing sensitivity to complement mediated cytotoxicity and facilitates uptake and killing by macrophages. The strains were further modified by deleting the araBAD and araE genes to avoid arabinose depletion during growth of the vaccine strains to high cell density and to prevent acid production from arabinose, as this may interfere with bacterial physiology (23). Finally, an asd deletion was introduced to facilitate use of the Asd+-balanced lethal plasmid encoding our test antigen.

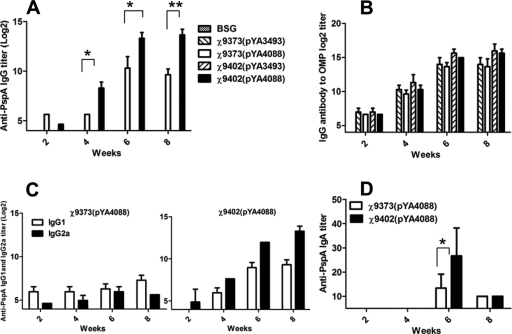

For these studies, we used plasmid pYA4088, which is similar to pYA3634 but encodes a longer fragment of PspA (54). Plasmid pYA4088 was introduced into strain χ9373 and its sopB derivative χ9402, and the resulting strains with a similar expression of PspA (Fig. 1B) were used to orally immunize mice. Serum IgG titers to PspA were significantly higher in mice immunized with χ9402(pYA4088) than in mice immunized with χ9373(pYA4088) at 4, 6, and 8 weeks postimmunization (Fig. 5A), as were anti-PspA IgA titers in vaginal secretions (Fig. 5D), indicating that inclusion of the sopB mutation enhanced immunity to the vectored antigen. No differences were observed in the anti-SOMP serum IgG titers between strains. When the immunized mice were challenged with 100 LD50s of S. pneumoniae WU, 47% of the mice immunized with χ9402(pYA4088) were protected, while only 33% of the mice immunized with χ9373(pYA4088) were protected (Table 3). Although this difference was not statistically significant, taken together, these results confirm that inclusion of a sopB deletion mutation into an RASV strain can enhance the immune response induced by a vectored antigen.

FIG. 5.

(A) Serum IgG responses to rPspA. (B) Serum IgG responses to SOMPs. The data represent IgG antibody levels induced in mice orally immunized with χ9373(pYA4088) (expressing rPspA), χ9373(pYA3493), χ9402(pYA4088) (expressing rPspA), and χ9402(pYA3493) at the indicated weeks after immunization. (C) Serum IgG1 and IgG2a responses to rPspA. The data represent ELISA results determining IgG1 and IgG2a subclass antibody levels to rPspA in sera of BALB/c mice orally immunized with χ9373(pYA4088) (expressing rPspA) and χ9402(pYA4088) (expressing rPspA) at the indicated weeks after immunization. (D) Vaginal-wash IgA responses to rPspA. The data represent ELISA results determining IgA antibody levels to rPspA in vaginal washes of BALB/c mice orally immunized with χ9373(pYA4088) (expressing rPspA) and χ9402(pYA4088) (expressing rPspA) at the indicated weeks after immunization. *, compared to χ9373(pYA4088)-immunized mice, the P value was <0.05; **, compared to χ9373(pYA4088)-immunized mice, the P value was <0.01.

TABLE 3.

Oral immunization of BALB/c mice with PspA-expressing Salmonella strains confers protection against S. pneumoniae challenge

| Vaccine straina | PspA expressionb | No. of challenged mice | No. of days to death (no. of mice)c | Protection rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSG | NA | 10 | 2 (8), 3 (2) | 0 |

| χ9373(pYA3493) | − | 7 | 2 (7) | 0 |

| χ9402(pYA3493) | − | 7 | 2 (5), 3 (2) | 0 |

| χ9373(pYA4088) | + | 15 | 2 (7), 3 (1), 4 (2), >15 (5) | 33 |

| χ9402(pYA4088) | + | 15 | 2 (6), 3 (2), >15 (7) | 47d |

Mice were orally immunized with a single dose of the indicated vaccine strains.

+, PspA expressed; −, PspA not expressed; NA, not applicable.

Eight weeks after the primary oral immunization, mice were challenged in two experiments with approximately 2 × 104 CFU of S. pneumoniae WU2. Both experiments gave similar results, and the data have been pooled for presentation and analysis.

Compared with χ9402(pYA3493)-immunized mice, the P value was <0.05.

DISCUSSION

The efficacy of a live vaccine carrier relies on an optimized balance between minimal damage to vaccinated hosts and maximal immunogenicity. Strain development has always been an important issue where a balance between attenuation level and effectiveness must be attained (26). In this study, we compared the abilities of pabA pabB or pabA pabB sopB attenuated serovar Typhimurium strains to act efficaciously as vectors for vaccine delivery. This was assessed by the ability of these strains expressing PspA to elicit immune responses against the vectored antigen. Interestingly, the incorporation of the sopB mutation led to the elicitation of significantly stronger humoral and cellular immune responses and memory T-cell responses, which led to the higher protection effect against virulent S. pneumoniae challenge. Similar results were also found when the sopB mutation was introduced into RASV strains with mutations in the pmi, fur, and crp genes. The results of our experiments using strains derived from the serovar Typhimurium parent strain, UK-1, expand on previous results by Link and associates, who showed that inclusion of a sopB mutation enhanced the immunogenicity of antigens delivered by serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 derivatives attenuated by sseC, aroA, or phoP deletions (27), indicating that the observed effect is not restricted to a particular parental strain or a specific type of attenuated background.

In addition to humoral responses, it has been reported that antibody-independent, T-cell-dependent responses also play a role in protection against virulent S. pneumoniae challenge (28, 52). CD4+ and CD8+ T cells have been classified into effector (CD44hi CD62Llo) and central (CD44hi CD62Lhi) memory (TCM) cells (40, 46). TCM cells home to lymph nodes and spleen and possess self-renewal functions that could allow rapid expansion into effectors upon encounter with antigen. TCM cells are most beneficial for conferring long-term protective memory (40). Our data showed that the ΔsopB strain χ9277(pYA3634) induced the highest frequency of CD4+ TCM cells in the spleen (Fig. 4), which in turn may provide the benefit of long-term protection against S. pneumoniae challenge.

Cytokines are key regulators of the immune system. They are essential to shape innate and adaptive immune responses, as well as for the establishment and maintenance of immunological memory (18). In this study, both the nonspecific cytokine environment and specific rPspA-stimulated lymphocyte-secreted cytokine levels were evaluated. Immunization with any of our vaccine strains led to increased systemic levels of both Th1- and Th2-type cytokine responses. For rPspA-specific cytokine responses, the sopB mutant strain, χ9277(pYA3634), elicited higher levels of both IFN-γ and IL-4 than its isogenic sopB+ counterpart. A number of studies have demonstrated that different parental backgrounds and attenuating mutations can affect the response to guest antigens in recombinant serovar Typhimurium (10), including dendritic cell function (9). In our case, deletion of the sopB gene affected the immune response to rPspA in such a way that both antibody production and T-cell immunity have been upregulated (Fig. 2, 3, and 5). Dendritic cells, which play an important role in adaptive immune response, may have played a role in these results (27). The SopB protein protects Salmonella-infected cells from apoptosis by sustained activation of Akt (22). Salmonella-induced apoptosis of infected macrophages is important for the presentation of bacterially encoded antigens after uptake by bystander dendritic cells (56). Therefore, in ΔsopB mutants, apoptosis is no longer inhibited, leading to efficient antigen uptake by dendritic cells and presentation to the immune system. A previous study reported that dendritic cells infected with attenuated sopB Salmonella strains exhibited higher expression levels of the major histocompatibility complex and the CD80, CD86, and CD54 molecules and showed a stronger capacity to process and present an I-Ed-restricted epitope from the influenza hemagglutinin (HA) to CD4+ cells from T-cell receptor-HA transgenic mice in vitro than did sopB+ strains, which led to higher T-cell proliferation activity against influenza HA (27). Our results are consistent with these observations. In contrast, previous studies showed that inclusion of sopB mutation shifted the immune response from primarily a Th1 response, typical for Salmonella (10, 20, 35, 36), to a Th2 response (27). In our strains, we observed a strong Th1 response, based on the IgG2a/IgG1 ratio (Fig. 2 and 5). The reason for the difference could be due to differences in dosing; we administered a single dose, while they immunized the mice three times. It could also be related to the difference in mode of attenuation. Their strain carried a deletion in the SPI-2 gene sseC, while our strain carried multiple mutations in non-SPI loci. More research is needed to explain the underlying mechanism.

In response to challenge, our data showed that a single oral dose of recombinant Salmonella was sufficient to protect mice from the fatal effects of challenge with 100 LD50s of virulent S. pneumoniae. Although only about half the mice were protected by the sopB mutant strains, these results represent an improvement over the results obtained in a previous study in which mice receiving two doses of a serovar Typhimurium vaccine (SopB+) expressing pspA were challenged with 50 LD50s of S. pneumoniae (20). A vaccine based on a single immunizing dose would be more attractive than an immunization protocol that requires boosting. Our aim is to develop single-dose RASV vectors that will provide 100% protection, and our results here demonstrate that inclusion of a sopB mutation represents an incremental step toward that goal.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI24533, R01 AI057885, R01 AI056289) and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (no. 37863).

We thank Susan Hollingshead (University of Alabama at Birmingham) for providing the WU2 strain, PspA protein, and PspA polyclonal antibody. Y.L. thanks the Zhujiang Hospital and Chinese NSFC (30500607) for their support.

Editor: A. Camilli

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bertani, G. 1951. Studies on lysogenesis. I. The mode of phage liberation by lysogenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 62293-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Briles, D. E., J. D. King, M. A. Gray, L. S. McDaniel, E. Swiatlo, and K. A. Benton. 1996. PspA, a protection-eliciting pneumococcal protein: immunogenicity of isolated native PspA in mice. Vaccine 14858-867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Curtiss, R., III, and S. M. Kelly. 1987. Salmonella typhimurium deletion mutants lacking adenylate cyclase and cyclic AMP receptor protein are avirulent and immunogenic. Infect. Immun. 553035-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Curtiss, R., III, X. Zhang, S.-Y. Wanda, H. Y. Kang, V. Konjufca, Y. Li, B. Gunn, S. Wang, G. Scarpellini, and I. S. Lee. 2007. Induction of host immune responses using Salmonella-vectored vaccines, p. 297-313. In K. A. Brogden, F. C. Minion, N. Cornick, T. B. Stanton, Q. Zhang, L. K. Nolan, and M. J. Wannemuehler (ed.), Virulence mechanisms of bacterial pathogens, 4th ed. ASM Press, Washington DC.

- 5.Curtiss, R., III, S. B. Porter, M. Munson, S. A. Tinge, J. O. Hassan, C. Gentry-Weeks, and S. M. Kelly. 1991. Nonrecombinant and recombinant avirulent Salmonella live vaccines for poultry, p. 169-198. In L. C. Blankenship (ed.), Colonization control of human bacterial enteropathogens in poultry. Academic Press, Inc., San Diego, CA.

- 6.Curtiss, R., III, S.-Y. Wanda, X. Zhang, and B. Gunn. 2007. Salmonella vaccine vectors displaying regulated delayed in vivo attenuation to enhance immunogenicity, abstr. E-061, p. 278. Abstr. 107th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 7.DeKruyff, R. H., L. V. Rizzo, and D. T. Umetsu. 1993. Induction of immunoglobulin synthesis by CD4+ T cell clones. Semin. Immunol. 5421-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dozois, C. M., M. Dho-Moulin, A. Bree, J. M. Fairbrother, C. Desautels, and R. Curtiss III. 2000. Relationship between the Tsh autotransporter and pathogenicity of avian Escherichia coli and localization and analysis of the tsh genetic region. Infect. Immun. 684145-4154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dreher, D., M. Kok, L. Cochand, S. G. Kiama, P. Gehr, J. C. Pechere, and L. P. Nicod. 2001. Genetic background of attenuated Salmonella typhimurium has profound influence on infection and cytokine patterns in human dendritic cells. J. Leukoc. Biol. 69583-589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunstan, S. J., C. P. Simmons, and R. A. Strugnell. 1998. Comparison of the abilities of different attenuated Salmonella typhimurium strains to elicit humoral immune responses against a heterologous antigen. Infect. Immun. 66732-740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunstan, S. J., C. P. Simmons, and R. A. Strugnell. 1999. Use of in vivo-regulated promoters to deliver antigens from attenuated Salmonella enterica var. Typhimurium. Infect. Immun. 675133-5141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galen, J. E., and M. M. Levine. 2001. Can a ‘flawless’ live vector vaccine strain be engineered? Trends Microbiol. 9372-376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Galyov, E. E., M. W. Wood, R. Rosqvist, P. B. Mullan, P. R. Watson, S. Hedges, and T. S. Wallis. 1997. A secreted effector protein of Salmonella dublin is translocated into eukaryotic cells and mediates inflammation and fluid secretion in infected ileal mucosa. Mol. Microbiol. 25903-912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gor, D. O., N. R. Rose, and N. S. Greenspan. 2003. Th1-Th2: a procrustean paradigm. Nat. Immunol. 4503-505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hitchcock, P. J., and T. M. Brown. 1983. Morphological heterogeneity among Salmonella lipopolysaccharide chemotypes in silver-stained polyacrylamide gels. J. Bacteriol. 154269-277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hohmann, E. L., C. A. Oletta, and S. I. Miller. 1996. Evaluation of a phoP/phoQ-deleted, aroA-deleted live oral Salmonella typhi vaccine strain in human volunteers. Vaccine 1419-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hone, D. M., C. O. Tacket, A. M. Harris, B. Kay, G. Losonsky, and M. M. Levine. 1992. Evaluation in volunteers of a candidate live oral attenuated Salmonella typhi vector vaccine. J. Clin. Investig. 90412-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jose, A. C., B. Adriana, R. Analia, and G. Sofia. 2007. The relevance of cytokines for development of protective immunity and rational design of vaccines. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 18195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kang, H. Y., and R. Curtiss III. 2003. Immune responses dependent on antigen location in recombinant attenuated Salmonella typhimurium vaccines following oral immunization. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 3799-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang, H. Y., J. Srinivasan, and R. Curtiss III. 2002. Immune responses to recombinant pneumococcal PspA antigen delivered by live attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine. Infect. Immun. 701739-1749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaufmann, S. H., J. Fensterle, and J. Hess. 1999. The need for a novel generation of vaccines. Immunobiology 201272-282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knodler, L. A., B. B. Finlay, and O. Steele-Mortimer. 2005. The Salmonella effector protein SopB protects epithelial cells from apoptosis by sustained activation of Akt. J. Biol. Chem. 2809058-9064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong, W., S. Y. Wanda, X. Zhang, W. Bollen, S. A. Tinge, K. L. Roland, and R. Curtiss III. 2008. Regulated programmed lysis of recombinant Salmonella in host tissues to release protective antigens and confer biological containment. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1059361-9366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Konjufca, V., S.-Y. Wanda, M. C. Jenkins, and R. Curtiss III. 2006. A recombinant attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine encoding Eimeria acervulina antigen offers protection against E. acervulina challenge. Infect. Immun. 746785-6796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Krishnan, L., K. Gurnani, C. J. Dicaire, H. van Faassen, A. Zafer, C. J. Kirschning, S. Sad, and G. D. Sprott. 2007. Rapid clonal expansion and prolonged maintenance of memory CD8+ T Cells of the effector (CD44highCD62Llow) and central (CD44highCD62Lhigh) phenotype by an archaeosome adjuvant independent of TLR2. J. Immunol. 1782396-2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kwon, Y. M., M. M. Cox, and L. N. Calhoun. 2007. Salmonella-based vaccines for infectious diseases. Expert Rev. Vaccines 6147-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Link, C., T. Ebensen, L. Standner, M. Dejosez, E. Reinhard, F. Rharbaoui, and C. A. Guzman. 2006. An SopB-mediated immune escape mechanism of Salmonella enterica can be subverted to optimize the performance of live attenuated vaccine carrier strains. Microbes Infect. 82262-2269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Malley, R., K. Trzcinski, A. Srivastava, C. M. Thompson, P. W. Anderson, and M. Lipsitch. 2005. CD4+ T cells mediate antibody-independent acquired immunity to pneumococcal colonization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1024848-4853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDaniel, L. S., J. Yother, M. Vijayakumar, L. McGarry, W. R. Guild, and D. E. Briles. 1987. Use of insertional inactivation to facilitate studies of biological properties of pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA). J. Exp. Med. 165381-394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McSorley, S. J., S. Asch, M. Costalonga, R. L. Reinhardt, and M. K. Jenkins. 2002. Tracking Salmonella-specific CD4 T cells in vivo reveals a local mucosal response to a disseminated infection. Immunity 16365-377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mittrucker, H.-W., B. Raupach, A. Kohler, and S. H. E. Kaufmann. 2000. Cutting edge: role of B lymphocytes in protective immunity against Salmonella typhimurium infection. J. Immunol. 1641648-1652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakayama, K., S. M. Kelly, and R. Curtiss III. 1988. Construction of an Asd+ expression-cloning vector: stable maintenance and high level expression of cloned genes in a Salmonella vaccine strain. Nat. Biotechnol. 6693-697. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nayak, A. R., S. A. Tinge, R. C. Tart, L. S. McDaniel, D. E. Briles, and R. Curtiss III. 1998. A live recombinant avirulent oral Salmonella vaccine expressing pneumococcal surface protein A induces protective responses against Streptococcus pneumoniae. Infect. Immun. 663744-3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Norris, F. A., M. P. Wilson, T. S. Wallis, E. E. Galyov, and P. W. Majerus. 1998. SopB, a protein required for virulence of Salmonella dublin, is an inositol phosphate phosphatase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9514057-14059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pascual, D. W., D. M. Hone, S. Hall, F. W. van Ginkel, M. Yamamoto, N. Walters, K. Fujihashi, R. J. Powell, S. Wu, J. L. Vancott, H. Kiyono, and J. R. McGhee. 1999. Expression of recombinant enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli colonization factor antigen I by Salmonella typhimurium elicits a biphasic T helper cell response. Infect. Immun. 676249-6256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pashine, A., B. John, S. Rath, A. George, and V. Bal. 1999. Th1 dominance in the immune response to live Salmonella typhimurium requires bacterial invasiveness but not persistence. Int. Immunol. 11481-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ramarathinam, L., D. W. Niesel, and G. R. Klimpel. 1993. Salmonella typhimurium induces IFN-γ production in murine splenocytes. Role of natural killer cells and macrophages. J. Immunol. 1503973-3981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reference deleted.

- 39.Reis, B. P., S. Zhang, R. M. Tsolis, A. J. Bäumler, L. G. Adams, and R. L. Santos. 2003. The attenuated sopB mutant of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium has the same tissue distribution and host chemokine response as the wild type in bovine Peyer's patches. Vet. Microbiol. 97269-277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rocha, B., and C. Tanchot. 2004. CD8 T cell memory. Semin. Immunol. 16305-314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Santander, J., S.-Y. Wanda, C. A. Nickerson, and R. Curtiss III. 2007. Role of RpoS in fine-tuning the synthesis of Vi capsular polysaccharide in Salmonella enterica serotype Typhi. Infect. Immun. 751382-1392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Santos, R. L., R. M. Tsolis, S. Zhang, T. A. Ficht, A. J. Bäumler, and L. G. Adams. 2001. Salmonella-induced cell death is not required for enteritis in calves. Infect. Immun. 694610-4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schmieger, H., and H. Backhaus. 1976. Altered cotransduction frequencies exhibited by HT-mutants of Salmonella-phage P22. Mol. Gen. Genet. 143307-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43a.Schwyn, B., and J. B. Neilands. 1987. Universal chemical assay for the detection and determination of siderophores. Anal. Biochem. 16047-56. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Sedgwick, J. D., and P. G. Holt. 1983. A solid-phase immunoenzymatic technique for the enumeration of specific antibody-secreting cells. J. Immunol. Methods 57301-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stocker, B. A., R. G. Wilkinson, and P. H. Mäkelä. 1966. Genetic aspects of biosynthesis and structure of Salmonella somatic polysaccharide. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 133334-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stockinger, B., G. Kassiotis, and C. Bourgeois. 2004. CD4 T-cell memory. Semin. Immunol. 16295-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tacket, C. O., D. M. Hone, R. Curtiss III, S. M. Kelly, G. Losonsky, L. Guers, A. M. Harris, R. Edelman, and M. M. Levine. 1992. Comparison of the safety and immunogenicity of ΔaroC ΔaroD and Δcya Δcrp Salmonella typhi strains in adult volunteers. Infect. Immun. 60536-541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tacket, C. O., S. M. Kelly, F. Schödel, G. Losonsky, J. P. Nataro, R. Edelman, M. M. Levine, and R. Curtiss III. 1997. Safety and immunogenicity in humans of an attenuated Salmonella typhi vaccine vector strain expressing plasmid-encoded hepatitis B antigens stabilized by the Asd-balanced lethal vector system. Infect. Immun. 653381-3385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tacket, C. O., G. Losonsky, J. P. Nataro, S. J. Cryz, R. Edelman, A. Fasano, J. Michalski, J. B. Kaper, and M. M. Levine. 1993. Safety and immunogenicity of live oral cholera vaccine candidate CVD 110, a ΔctxA Δzot Δace derivative of El Tor Ogawa Vibrio cholerae. J. Infect. Dis. 1681536-1540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tacket, C. O., M. B. Sztein, G. A. Losonsky, S. S. Wasserman, J. P. Nataro, R. Edelman, D. Pickard, G. Dougan, S. N. Chatfield, and M. M. Levine. 1997. Safety of live oral Salmonella typhi vaccine strains with deletions in htrA and aroC aroD and immune response in humans. Infect. Immun. 65452-456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Turner, A. K., T. D. Terry, D. A. Sack, P. Londono-Arcila, and M. J. Darsley. 2001. Construction and characterization of genetically defined aro omp mutants of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli and preliminary studies of safety and immunogenicity in humans. Infect. Immun. 694969-4979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Van Rossum, A. M., E. S. Lysenko, and J. N. Weiser. 2005. Host and bacterial factors contributing to the clearance of colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 737718-7726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, S., Y. Li, G. Scarpellini, W. Kong, and R. Curtiss III. 2007. Salmonella vaccine vectors displaying regulated delayed antigen expression in vivo to enhance immunogenicity, abstr. E-064, p. 278. Abstr. 107th Gen. Meet. Am. Soc. Microbiol. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 54.Xin, W., S. Y. Wanda, Y. Li, S. Wang, H. Mo, and R. Curtiss III. 2008. Analysis of type II secretion of recombinant pneumococcal PspA and PspC in a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium vaccine with regulated delayed antigen synthesis. Infect. Immun. 763241-3254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yan, Z. X., and T. F. Meyer. 1996. Mixed population approach for vaccination with live recombinant Salmonella strains. J. Biotechnol. 44197-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yrlid, U., and M. J. Wick. 2000. Salmonella-induced apoptosis of infected macrophages results in presentation of a bacteria-encoded antigen after uptake by bystander dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 191613-624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zekarias, B., H. Mo, and R. Curtiss III. 2008. Recombinant attenuated Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium expressing the carboxy-terminal domain of alpha toxin from Clostridium perfringens induces protective responses against necrotic enteritis in chickens. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 15805-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang, Q., J. Bernatoniene, L. Bagrade, A. J. Pollard, T. J. Mitchell, J. C. Paton, and A. Finn. 2006. Serum and mucosal antibody responses to pneumococcal protein antigens in children: relationships with carriage status. Eur. J. Immunol. 3646-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhang, S., R. L. Santos, R. M. Tsolis, S. Stender, W. D. Hardt, A. J. Bäumler, and L. G. Adams. 2002. The Salmonella enterica serotype Typhimurium effector proteins SipA, SopA, SopB, SopD, and SopE2 act in concert to induce diarrhea in calves. Infect. Immun. 703843-3855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhou, D., and J. Galan. 2001. Salmonella entry into host cells: the work in concert of type III secreted effector proteins. Microbes Infect. 31293-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]