Abstract

Citrobacter rodentium is an attaching and effacing pathogen which causes transmissible colonic hyperplasia in mice. Infection with C. rodentium serves as a model for infection of humans with enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. To identify novel colonization factors of C. rodentium, we screened a signature-tagged mutant library of C. rodentium in mice. One noncolonizing mutant had a single transposon insertion in an open reading frame (ORF) which we designated regA because of its homology to genes encoding members of the AraC family of transcriptional regulators. Deletion of regA in C. rodentium resulted in markedly reduced colonization of the mouse intestine. Examination of lacZ transcriptional fusions using promoter regions of known and putative virulence-associated genes of C. rodentium revealed that RegA strongly stimulated transcription of two newly identified genes located close to regA, which we designated adcA and kfcC. The cloned adcA gene conferred autoaggregation and adherence to mammalian cells to E. coli strain DH5α, and a kfc mutation led to a reduction in the duration of intestinal colonization, but the kfc mutant was far less attenuated than the regA mutant. These results indicated that other genes of C. rodentium whose expression required activation by RegA were required for colonization. Microarray analysis revealed a number of RegA-regulated ORFs encoding proteins homologous to known colonization factors. Transcription of these putative virulence determinants was activated by RegA only in the presence of sodium bicarbonate. Taken together, these results show that RegA is a global regulator of virulence in C. rodentium which activates factors that are required for intestinal colonization.

Citrobacter rodentium is the causative agent of transmissible colonic hyperplasia of mice (2, 40) and a member of a family of bacterial pathogens that cause attaching and effacing (A/E) lesions in the intestines of their affected hosts. The histopathological hallmarks of these lesions include intimate bacterial attachment to host intestinal epithelial cells and localized damage to brush border microvilli as a consequence of cytoskeletal rearrangement within the host cell (13). Prominent members of the A/E family of pathogens responsible for human disease include enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC). EPEC is an important causative agent of infantile diarrhea, whereas EHEC causes diarrhea, hemorrhagic colitis, and the hemolytic-uremic syndrome (31). Because it is a natural pathogen of mice, C. rodentium has emerged as a valuable model for studying the pathogenesis of A/E bacteria, as it induces A/E lesions that are morphologically indistinguishable from those caused by EPEC and EHEC (40).

The capacity to evoke A/E lesions requires a pathogenicity island termed the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE). Among the LEE-encoded factors responsible for this phenotype are regulators of LEE gene expression (Ler and GrlR/GrlA), the eae-encoded outer membrane adhesin (intimin) and its translocated receptor (Tir), a type III secretion system, and several secreted effector proteins (10, 11, 38). The LEE pathogenicity island of C. rodentium shares a high degree of similarity with those of EPEC and EHEC (10).

Adherence to and colonization of host tissues are key events in bacterial pathogenesis. The type IV bundle-forming pilus of EPEC is an essential virulence determinant that is required for attachment of EPEC to host epithelial cells (6, 16, 25, 48). In C. rodentium, a type IV pilus colonization factor, designated Cfc, is also required for virulence (30). Cfc was identified by use of signature-tagged mutagenesis (STM), a high-throughput system which has facilitated the identification of a large number and variety of genes required for the virulence and survival of many different bacterial pathogens (1, 42). Here, we describe a previously unrecognized transcriptional regulator of C. rodentium, which was detected in an STM screen and is required for colonization of the mouse intestine by C. rodentium.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth conditions.

The bacterial strains, plasmids, and PCR primers used in this study are listed in Tables 1 and 2. Bacteria were grown at 37°C on solid Luria-Bertani (LB) medium or in liquid LB medium unless otherwise specified. Where appropriate, media were supplemented with antibiotics at the following concentrations: ampicillin, 100 μg/ml; chloramphenicol, 10 μg/ml; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml; nalidixic acid, 50 μg/ml; and trimethoprim, 40 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference(s) or source |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| DH5α | Nonpathogenic E. coli K-12 laboratory strain | 39 |

| ICC169 | Spontaneous Nalr derivative of wild-type C. rodentium biotype 4280 (Nalr) | 30, 52 |

| P1A2 | Random transposon mutant of ICC169 (Kanr) | 21, 30 |

| EMH1 | C. rodentium regA::aphA-2 (Nalr Kanr) | This study |

| EMH2 | C. rodentium adcA::aphA-2 (Nalr Kanr) | This study |

| EMH3 | C. rodentium kfc::cat (Nalr Cmr) | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pACYC184 | Medium-copy-number cloning vector (Cmr Tetr) | Fermentas, Burlington, Ontario, Canada |

| pAT153 | Medium-copy-number cloning vector (Ampr) | 49 |

| pBAC1 | pBluescript II carrying the cat gene from pACYC184 (Ampr Cmr) | Praszkiera |

| pEH4 | Derivative of pAT153 carrying regA (Ampr) | This study |

| pEH6 | Derivative of pACYC184 carrying regA (Cmr) | This study |

| pEH32 | Derivative of pAT153 carrying adcA (Ampr) | This study |

| pGEM-T Easy | High-copy-number cloning vector (Ampr) | Promega, Madison, WI |

| pKD46 | Red recombinase system expression plasmid (Ampr) | 9 |

| pMU2385 | Low-copy-number transcriptional fusion vector derived from pMU575 (Tmpr) | 37 |

| pTOPO-TA | Medium-copy-number cloning vector (Ampr Kanr) | Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA |

| pUC4-KIXX | pUC4K derivative containing aphA-2 gene (kanamycin resistance cassette) from Tn5 (Kanr Bler) | Pfizer Ltd., West Ryde, NSW, Australia |

J. Praszkier, Department of Microbiology and Immunology, The University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

TABLE 2.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence (5′-3′) | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| aidAF | CGGGATCCTAATGTCGGAGACGTCCAGG | adcA promoter region |

| aidAR | CCAAGCTTTTGTGCGAAATCGCGATAGG | adcA promoter region |

| em31 | TCTGCATGACCATATGGGATGGAGCAAGCG | regA |

| em32 | GGAATACTAAGCTTATTTCCATTAGTAGCTCCGG | regA |

| em33 | ATGGAAATAAGCTTAGTATTCCTTGAGGCCTCGG | regA |

| em34 | TTCACGAAATTCATTAGATTCATATGGCCG | regA |

| em41 | GGGGTACCTAACTTTACACCACGGACGG | regA |

| em42 | GCTGTAGAAACGCTATTTAATCCTCCGG | regA |

| em52 | TCAAGCTGATAGTTGCTGGG | adcA |

| em53 | ATCGGTTAAAGCTTAACTAAAATCAGCCATGGG | adcA |

| em54 | TTTTAGTTAAGCTTTAACCGATTTGCCTGGCAG | adcA |

| em55 | AATATCGTAATGACCGAAGG | adcA |

| em64 | CGGGATCCTGTTACCTACATCTGAGGCG | kfcC promoter region |

| em65 | CCAAGCTTTTCCTAAGTCAACACTGGCG | kfcC promoter region |

| em66 | CGAGCTCTGATAGATTACAGGTCGCAG | adcA |

| em67 | GCTCTAGATCTGATCTGTAAGCAAGCG | adcA |

| em69 | AATTGTGGCAGTCTTGGGTG | kfcC |

| em70 | CGGGATCCAATAGCCTTATCCGTCTCGG | kfcC |

| em76 | CGGGATCCAATGCCAAGTTAATAACGGG | kfcH |

| em77 | TAAATGTCACCGGCAAGCTG | kfcH |

Construction of C. rodentium nonpolar deletion mutants.

Nonpolar mutants with mutations in the regA, adcA, and kfcC-kfcH genes were constructed using the λ Red recombinase system (9). Target genes were deleted and replaced with the kanamycin resistance gene cassette (aphA-2) from plasmid pUC4-KIXX or the chloramphenicol resistance gene (cat) from plasmid pBAC1. Overlapping PCR was used to generate ∼700-bp fragments containing the 5′ and 3′ ends of the genes of interest flanking a HindIII restriction site from genomic DNA of C. rodentium strain ICC169. Primers em31, em32, em33, and em34 were used to generate fragments specific for regA; primers em52, em53, em54, and em55 were used to generate fragments specific for adcA; and primers em69, em70, em76, and em77 were used to generate fragments specific for kfcC and kfcH. The PCR fragments generated were cloned into the multiple-cloning site of plasmid pGEM-T Easy (Promega Corp., Madison, WI.), and the resultant plasmids were subsequently digested with HindIII and ligated to the HindIII-digested kanamycin or chloramphenicol resistance genes. Fragments containing the resistance gene flanked by regions of homology to the genes of interest were electroporated into C. rodentium strain ICC169 expressing λ Red recombinase (encoded by plasmid pKD46), and mutants were selected on LB agar supplemented with kanamycin or chloramphenicol. All mutations were confirmed by PCR amplification using primers external to the disrupted gene(s) (data not shown).

Construction of plasmids carrying regA.

The low- to medium-copy-number plasmid pAT153 was used in complementation studies (49). A wild-type copy of the regA gene was amplified from genomic DNA of C. rodentium strain ICC169 using PCR primers em41 and em42. A 1.5-kb fragment encompassing regA and its ∼300-bp flanking sequences was cloned into the KpnI and XbaI sites of pAT153 behind the lac promoter to generate plasmid pEH4. The latter plasmid was then electroporated into a regA mutant, EMH1, to generate the complemented regA mutant EMH1(pEH4). The same regA fragment was also cloned into BamHI/SalI-digested pACYC184 (a 13-copy vector) to generate pEH6 in order to analyze RegA-mediated transcriptional regulation in C. rodentium.

Construction of promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions.

Various lacZ transcriptional fusions were constructed by PCR amplification of DNA fragments containing the predicted promoter sequences of ler, sepZ, orf12, sepL, cfcA, regA, adcA, kfcC, or the efa1 homolog using genomic DNA of C. rodentium strain ICC169 as the template. The primers used to amplify the promoter regions of adcA and kfcC are shown in Table 2. Each of the PCR fragments was cloned into plasmid pTOPO-TA (Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) and sequenced with an ABI Prism 377 DNA sequencer using ABI Prism BigDye Terminators (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The fragments were then excised from the pTOPO-TA derivatives and cloned into the appropriate sites of the single-copy plasmid pMU2385 to create lacZ transcriptional fusions (37). The resulting plasmids were electroporated into E. coli DH5α and C. rodentium strains ICC169 and EMH1.

β-Galactosidase assay.

β-Galactosidase activity was assayed as described by Miller (29), and the specific activity was expressed in Miller units. The data presented below are the results of at least three independent assays in which samples were processed in duplicate.

Cloning of adcA, the aidA homolog of C. rodentium.

A wild-type copy of adcA, an aidA gene homolog, was amplified from genomic DNA of C. rodentium strain ICC169 using PCR primers em66 and em67. The 4.6-kb fragment containing adcA and its flanking regions (Fig. 1) was cloned into the SacI and XbaI sites of pAT153 behind the lac promoter to generate plasmid pEH32, which was then electroporated into E. coli strain DH5α.

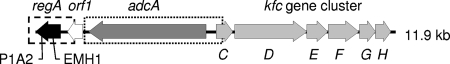

FIG. 1.

Genetic location of regA: schematic diagram of regA and surrounding ORFs. P1A2 and EMH1 indicate the sites of insertion of the Tn5 transposon and kanamycin resistance gene, respectively. The amplified region containing regA is indicated by a dashed rectangle, and the amplified region containing adcA is indicated by a dotted rectangle.

Suspension and autoaggregation assays.

An autoaggregation assay was performed as described previously (50). Briefly, overnight cultures of test strains were washed and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at the same optical density at 600 nm (OD600). Five milliliters of each suspension was mixed vigorously for 30 s. The cultures were then left undisturbed, and at selected time points 100-μl samples were taken from each tube approximately 0.5 cm from the top for measurement of the OD600. The data were expressed as a mean absorbance percentage by determining the absorbance at the time examined relative to the mean absorbance at time zero. The degree of autoaggregation was inversely proportional to the turbidity. To visualize cell clumping, overnight cultures of test strains were resuspended in an equal volume of 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.4). Ten-microliter portions of the bacterial suspensions were spotted onto glass slides and observed at a magnification of ×1,000 using phase-contrast microscopy.

Assay for bacterial adhesion to HEp-2 cells.

The assay used to determine the extent and pattern of bacterial adherence to HEp-2 epithelial cells was based on the CVD method reported previously (51). Bacteria were grown in Penassay broth without shaking at 37°C overnight. HEp-2 cells were passaged at 37°C in air containing 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum and 2 mM glutamine. HEp-2 monolayers that were ∼70% confluent on 12-mm-diameter glass coverslips were incubated with 10 μl of a washed bacterial suspension for 3 h. The coverslips were then washed three times with PBS, and the cells were fixed with Giemsa buffer (Sørensen buffer, 34 mM KH2PO4, 33 mM Na2PO4, 0.005% sodium azide [pH 6.8]) and 100% methanol and stained with 10% Giemsa stain. The patterns of bacterial adherence to HEp-2 cells were defined as described elsewhere (51). Adherence was quantified by determining the number of bacteria adhering to 50 HEp-2 cells.

Infection of mice.

Four- to five-week-old male, specific-pathogen-free C57BL/6 mice were housed in groups of five in cages with filter tops, and they had free access to food and water. The cages were kept in ventilator cabinets, and mice were handled in a class II biohazard cabinet. Screening of the STM library of C. rodentium in C57BL/6 mice has been described previously (21).

Unanesthetized mice were given 200 μl of a bacterial suspension containing 2 × 109 CFU in PBS by gavage using a feeding needle (Cole-Palmer, Vernon Hills, IL). The viable count of each inoculum was determined by plating on LB agar. At specified time points after inoculation, three to five fecal pellets were collected aseptically from each mouse and emulsified in PBS to obtain a final concentration of 100 mg/ml. The number of viable bacteria per gram of feces was determined by plating serial dilutions of the samples onto media containing appropriate antibiotics. The limit of detection was 1 × 102 CFU/g.

In infection experiments with two bacterial strains, mice received 2 × 109 CFU of the test strain and an approximately equal number of wild-type C. rodentium CFU in 200 μl PBS via oral gavage. At selected times after inoculation, mice were killed using inhaled CO2, after which the colon of each mouse was removed and incised so that the fecal pellets could be removed. Colonic tissue was homogenized in PBS to obtain a final concentration of 100 mg/ml. To determine the ratio of mutant bacteria to wild-type bacteria, dilutions of the original inoculum and samples from the colon were plated on LB agar containing nalidixic acid to select for C. rodentium and on LB agar containing nalidixic acid and kanamycin to select for the C. rodentium mutant. The ability of each mutant to compete with the wild-type strain was analyzed by using at least five animals, and a competitive index (CI) was calculated by determining the ratio of mutant to wild-type bacteria recovered from animals compared to the ratio of these bacteria in the inoculum (14). Mutants with a CI of <0.5 were considered attenuated.

Histology and crypt length measurement.

Full-thickness colonic samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. Sections (4 μm) were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. Photomicrographs were taken using a Leica DM-LB HC microscope and Leica DC200 digital camera (Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany). Crypt lengths were measured by using micrometry, and 10 measurements were obtained for the distal colon of each mouse. Only well-oriented crypts were measured.

Antisense C. rodentium microarrays.

We designed custom antisense oligonucleotide microarrays using the Agilent eArray platform (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). The arrays contained 4,307 open reading frames (ORFs) representing all gene predictions for C. rodentium strain ICC168 available at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute website (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_rodentium/). Each ORF was represented by at least three different oligonucleotides.

RNA isolation and labeling.

Overnight cultures of C. rodentium strains EMH1 (RegA−) and EMH1(pEH6) (RegA+) were inoculated into LB medium or LB medium containing NaHCO3 (45 mM) to obtain an OD600 of 0.1 and grown until the OD600 was 0.88. Ten milliliters of a culture was incubated with 20 ml of an RNAprotect solution (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) at room temperature for 15 min. Cells were pelleted, and RNA was purified using a FastRNA Pro Blue kit (Qbiogene Inc., Carlsbad, CA). The RNA samples were then treated with DNase I using an RNase-free DNase set (Qiagen) before they were purified further using an RNeasy MiniElute kit (Qiagen). For direct labeling of RNA with Cy5- and Cy3-ULS, 5 μg of total RNA was labeled as described in the Kreatech ULS labeling procedure (Kreatech Diagnostics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). The RNA quality and concentration and the degree of labeling were determined with an Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer and an ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Rockland, DE).

Fragmentation, microarray hybridization, scanning, and analysis.

Fragmentation and hybridization were performed at the Australian Genome Research Facility Ltd. (AGRF, Melbourne, Australia) as described in the Agilent two-color microarray-based gene expression analysis manual (version 5.7). Following hybridization, all microarrays were washed as described in the manual and scanned using an Agilent microarray scanner and Feature Extraction software (Agilent). Normalization and data analysis were performed using the limma package in bioconductor (45-47). Genes were considered differentially expressed if they showed an average change of ≥2-fold with an adjusted P value of ≤0.05.

Accession numbers.

The GenBank accession number for the regA sequence reported in this paper is FJ222237. The supporting microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, series accession number GSE12876.

RESULTS

Characterization of RegA.

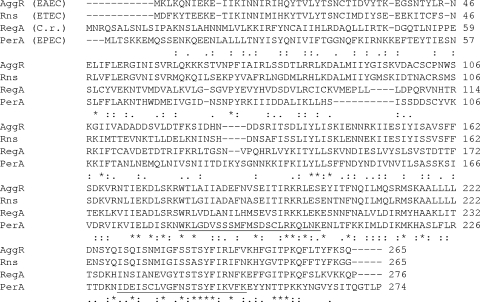

In a study reported previously (21), signature-tagged mutants of C. rodentium strain ICC169 (30) were tested to determine their abilities to colonize 4- to 5-week-old male C57BL/6 mice. Pools of 12 mutants were used to infect mice, and fecal and colon samples were collected 5 and 7 days after inoculation, respectively. Mutants that were missing from the output pools were retested in mixed-infection experiments with wild-type C. rodentium, and the mutants with a CI less than 0.1 were considered highly attenuated. One mutant of particular interest, P1A2, carried a transposon insertion in a gene encoding a putative regulator with similarity to the AraC family of transcriptional regulators (21). The predicted 31.6-kDa gene product, which we designated RegA for regulation factor A, showed homology to regulators of virulence genes, including Rns of enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) (7), AggR of enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) (32), and PerA of EPEC (17, 36) (Fig. 2). A comparison of the sequences of RegA and related members of the AraC family of DNA-binding proteins showed that the homology was most pronounced toward the C-terminal end, where two predicted helix-turn-helix motifs occur. The second helix-turn-helix motif is highly conserved among members of this family and is thought to contain all the domains necessary for the proteins to interact with target DNA sequences and RNA polymerase, thus activating transcription from target promoters (15).

FIG. 2.

Comparison of the predicted amino acid sequences of the regulatory proteins AggR, Rns, and PerA with the amino acid sequence of RegA. Sequences were aligned by using the ClustalW program. The amino acids in the putative helix-turn-helix regions are underlined. Identical amino acid residues are indicated by asterisks, conserved residues are indicated by a colons, and semiconserved residues are indicated by periods. C. r., C. rodentium.

To confirm that the reduced colonizing ability of the signature-tagged mutant P1A2 was directly attributable to regA, a targeted regA deletion mutant was constructed using the λ Red recombinase system (9). The regA deletion mutant obtained in this way, EMH1, was then complemented in trans with a wild-type copy of the regA gene using plasmid pEH4. The regA deletion mutant and the complemented mutant were then tested in single- and mixed-infection experiments with C57BL/6 mice. In a mixed infection with wild-type C. rodentium, mutant EMH1 was markedly attenuated, with a CI on day 7 of <10−5. In contrast, the CI of the complemented mutant was >1, indicating that this strain was not outcompeted by wild-type C. rodentium.

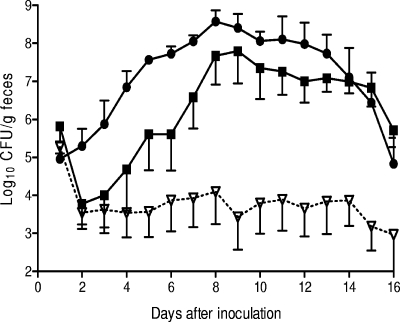

In single-infection studies, the mean maximum number of CFU of regA mutant EMH1 in feces was 1.2 × 104 CFU/g, which was 0.02% of the level of the wild type (6.2 × 107 CFU/g; P = 0.005, two-tailed Student's t test) (Fig. 3). The extent of attenuation of EMH1 was similar to that of the STM mutant P1A2 (data not shown). EMH1 carrying pAT153, the vector used to construct the trans-complementing plasmid pEH4, showed colonizing ability similar to that of EMH1 (data not shown). However, when an intact copy of the disrupted regA gene was supplied in trans, wild-type levels of colonization were restored, and for the complemented mutant, EMH1(pEH4), the mean maximum count was 3.8 × 108 CFU/g feces, compared to 6.2 × 107 CFU/g for the wild-type strain (P = 0.5, two-tailed Student's t test) (Fig. 3). In addition, the mice infected with the regA mutant (EMH1) or the signature-tagged mutant (P1A2) showed less severe intestinal pathology than the mice infected with wild-type C. rodentium, exhibiting significantly reduced crypt lengths 6 and 14 days after inoculation (Table 3). These results established that C. rodentium requires regA for normal intestinal colonization of mice.

FIG. 3.

Colonization of C57BL/6 mice by derivatives of C. rodentium. The data are the means and standard errors of the mean for feces from at least five individual mice at selected time points after inoculation. Mice received (via oral gavage) 2 × 109 CFU of C. rodentium wild-type strain ICC169 (▪), regA deletion mutant EMH1 (▿), or trans-complemented regA mutant EMH1(pEH4) (•).

TABLE 3.

Colon crypt length in C57BL/6 mice infected with derivatives of C. rodentium ICC169

| Strain of C. rodentiuma | Crypt length (μm) onb:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Day 6 | Day 10 | Day 14 | |

| None | 141 ± 12 | 136 ± 18 | 124 ± 18 |

| P1A2 | 151 ± 25 | 160 ± 11 | 145 ± 16 |

| EMH1 | 189 ± 21 | 214 ± 18 | 190 ± 19 |

| ICC169 | 208 ± 18c,d | 221 ± 27c | 292 ± 27c,d |

C57BL/6 mice were orally inoculated with approximately 2 × 109 CFU C. rodentium wild-type strain ICC169 or regA mutant P1A2 or EMH1.

The values are the means ± standard errors of the means for three to five individual animals.

The value is significantly higher than the value for mice infected with strain P1A2 at the same time (P < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t test).

The value is significantly higher than the value for mice infected with strain EMH1 at the same time (P < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t test).

Targets for regulation by RegA in C. rodentium.

Regulatory factors can function as virulence genes by controlling the expression of genes more directly involved in pathogenesis. The role of RegA in the regulation of LEE genes was initially investigated by performing fluorescence actin staining (FAS), which showed that wild-type strain ICC169 and regA deletion mutant EMH1 exhibited equivalent FAS activities (data not shown). However, any possible downregulation of LEE promoters due to the absence of RegA in mutant EMH1 was unclear due to the qualitative nature of the FAS assay and the weak adherence phenotype of both the wild-type and mutant strains. Accordingly, we performed a quantitative analysis of the regulation of known and putative virulence determinants of C. rodentium by RegA. The potential targets selected for this investigation included LEE genes (ler, sepZ, orf12, and sepL); cfcA, which encodes the fimbrial subunit of Cfc (30); and a gene encoding a homolog of the EHEC adhesin, efa1. All of these genes play a proven or putative role in colonization (33). PCR fragments that were ∼700 bp long and contained the promoters of interest were directionally cloned into pMU2385 to create promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions. pMU2385 is a single-copy vector which carries a promoterless lacZ structural gene with its own translational signals (37). Each of the pMU2385 derivatives was transformed into RegA− and RegA+ E. coli and C. rodentium strains. β-Galactosidase activity was assessed for each of the transformants grown in LB broth and DMEM at 37°C. Regardless of the host strain or culture medium, RegA did not affect the β-galactosidase activity of any of the promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions investigated (data not shown), indicating that RegA does not directly regulate the expression of any of these genes.

Bioinformatic analysis of the C. rodentium genome revealed a large ORF upstream of regA encoding a protein with homology to an autotransporter involved in diffuse adherence (AIDA) (83% identity at the amino acid level), as well as a predicted operon with homology to the K99 fimbrial cluster of ETEC (24 to 48% identity) (Fig. 1). Promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions were constructed using the two predicted promoter regions from these ORFs, and β-galactosidase activity was assayed as described above.

Wild-type C. rodentium (RegA+) carrying the aidA homolog promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusion showed no increase in β-galactosidase expression when it was grown in LB medium, but the expression was 10.5-fold greater than that of the RegA− strain, EMH1 carrying the control vector pACYC184, when both strains were grown in DMEM (Table 4). Complementation of EMH1 carrying pACYC184 encoding regA (pEH6) resulted in a 1.6-fold increase in β-galactosidase expression when bacteria were grown in LB medium and a 97.4-fold increase when they were cultured in DMEM (Table 4). For C. rodentium strains carrying the K99 homolog transcriptional fusion, the expression of β-galactosidase in the presence of RegA did not increase significantly in LB medium, but it increased 4.0-fold in DMEM in the wild-type background and increased 38.1-fold in DMEM in EMH1 carrying pACYC184 containing regA (pEH6). These results indicated that transcription of both the aidA and K99 homologs was strongly stimulated by RegA and that this increase was more pronounced in DMEM.

TABLE 4.

Promoter activity of adcA and kfcC transcriptional fusions in C. rodentium host strains EMH1 and ICC169 cultured in LB broth and DMEM, showing the effects of RegA on levels of expression

| Transcriptional fusion | β-Galactosidase sp act (Miller units) of C. rodentium strains grown ina:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LB broth

|

DMEM

|

|||||

| EMH1 (pACYC184) (RegA−) | ICC169 (RegA+) | EMH1(pEH6) (RegA+) | EMH1 (pACYC184) (RegA−) | ICC169 (RegA+) | EMH1(pEH6) (RegA+) | |

| adcA-lacZ (aidA homolog) | 20 | 24 (1.2) | 31 (1.6) | 3.9 | 41 (10.5) | 380 (97.4) |

| kfcC-lacZ (K99 homolog) | 41 | 43 (1.0) | 44 (1.1) | 40 | 161 (4.0) | 1,525 (38.1) |

The β-galactosidase activities are the averages for three independent assays in which samples were tested in duplicate, and the standard deviations were less than 15%. The numbers in parentheses indicate the level of activation (fold), which is the ratio of the specific activity of β-galactosidase of the RegA+ strain to the specific activity of β-galactosidase of the corresponding RegA− strain.

Role of the AIDA homolog of C. rodentium in adhesion and intestinal colonization.

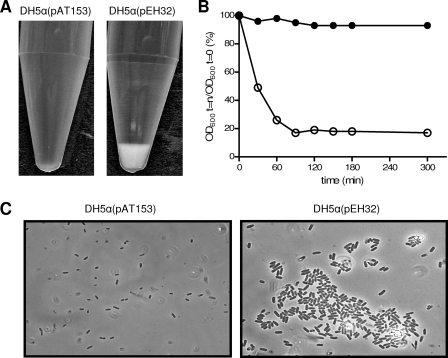

The afimbrial adhesin AIDA is associated with the adherence of strains of E. coli to a wide range of human and nonhuman cell types in vitro (3, 23, 41), as well as enhancement of biofilm formation and mediation of autoaggregation of E. coli cells (44). To determine if the AIDA homolog of C. rodentium functions as an adhesin, the putative aidA gene homolog of C. rodentium was cloned into pAT153 to generate plasmid pEH32, which was electroporated into E. coli DH5α. When overnight broth cultures of E. coli DH5α(pEH32) containing the cloned aidA gene homolog were left to stand, the cells readily aggregated and settled (Fig. 4). In contrast, cells in broth cultures of DH5α containing the pAT153 vector alone remained in suspension under the same conditions. To explore the autoaggregation phenotype further, we studied the kinetics of AIDA homolog-mediated aggregation. As shown in Fig. 4, a suspension of DH5α(pEH32) cells had almost entirely settled 90 min after it was left to stand, whereas cells of strain DH5α with the pAT153 vector control remained in suspension throughout the observation period. Microscopic analysis of DH5α(pEH32) showed that bacterial aggregates formed, while DH5α cells containing the vector alone showed no aggregation (Fig. 4). Together, these results indicated that the product of the aidA homolog mediates bacterium-bacterium interactions. A similar analysis of wild-type C. rodentium wild-type strain ICC169 and an aidA-homolog deletion mutant showed that neither strain was capable of forming bacterial aggregates, suggesting that insufficient amounts of the gene product were synthesized by C. rodentium in vitro or that other molecules on the surface of C. rodentium may interfere with autoaggregation.

FIG. 4.

Effect of adcA from C. rodentium on cell-cell adherence in E. coli DH5α. (A) Settling of bacterial cells after 90 min, (B) quantitative autoaggregation, and (C) the microscopic appearance of bacteria were investigated using static liquid suspensions of strains DH5α(pAT153) (vector control) (•) and DH5α(pEH32) (adcA cloned from strain ICC169) (○). The data are the means of two independent assays. The aggregation phenotype in panel C was visualized by phase-contrast microscopy (original magnification, ×1,000).

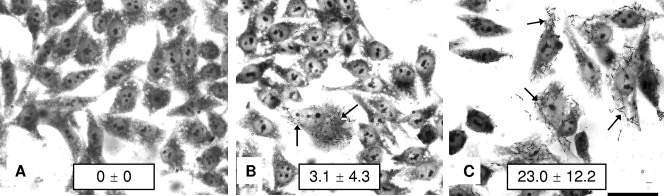

In addition to mediating bacterial aggregation, the AIDA protein of E. coli is known to confer a diffuse pattern of adherence to HeLa cells (4). When incubated with HEp-2 cell monolayers for 3 h, cells of E. coli DH5α(pEH32) expressing the aidA homolog adhered to HEp-2 cells in a diffuse pattern (Fig. 5B), an effect which was greatly enhanced when regA was also present (Fig. 5C). In contrast, cells of strain DH5α and strain DH5α with the pAT153 vector control showed no evidence of adherence (Fig. 5A), even when regA was present (data not shown). These results (i) demonstrated that the aidA homolog of C. rodentium, which we designated adcA (adhesin involved in diffuse Citrobacter adhesion), encodes an adhesin that mediates binding of bacteria to tissue culture cells and (ii) provided a clear link between regA and the expression of adcA.

FIG. 5.

Adherence of E. coli DH5α strains to HEp-2 cells. (A) DH5α(pAT153) (nonadherent vector control). (B) DH5α(pEH32) expressing adcA of C. rodentium showing a diffuse pattern of adherence. (C) DH5α(pEH6, pEH32) expressing both adcA and regA of C. rodentium showing an enhanced diffuse adherence pattern. Bar = 50 μm. The arrows indicate adherent bacteria. The preparations were stained with Giemsa stain. The mean ± standard deviation number of adherent bacteria per HEp-2 cell is shown for each strain.

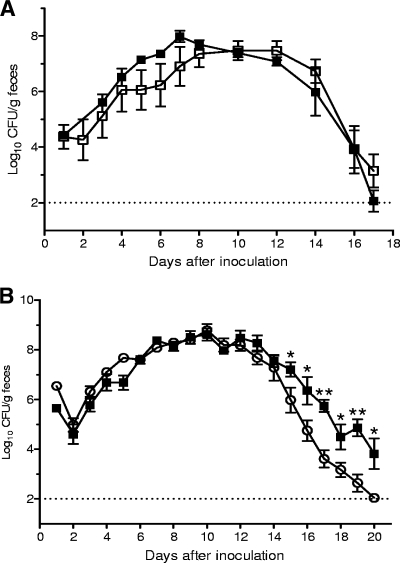

To determine if adcA contributes to the ability of C. rodentium to colonize the mouse intestine, mice were given 2 × 109 CFU of the C. rodentium wild-type strain or its isogenic adcA mutant, EMH2, in a single-infection experiment. Enumeration of bacteria in feces showed that there was no significant difference in the abilities of the two strains to colonize mice (Fig. 6) and that the maximum mean concentrations of bacteria in feces were 3 × 107 and 9 × 107 CFU/g, respectively (P = 0.2, two-tailed Student's t test). In addition, in mixed-infection experiments, mutant EMH2 was not outcompeted by wild-type C. rodentium on day 7 after inoculation (CI, >1), indicating that adcA on its own does not make a significant contribution to the colonization of mice by C. rodentium.

FIG. 6.

Colonization of C57BL/6 mice with derivatives of C. rodentium. The data are the means and standard errors of the means for feces from at least five individual mice at selected time points after inoculation. Mice received (via oral gavage) 2 × 109 CFU of (A) C. rodentium wild-type strain ICC169 (▪) or adcA deletion mutant EMH2 (□) or (B) wild-type strain ICC169 (▪) or kfc deletion mutant EMH3 (○). The limit of detection is indicated by a dotted line. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.005 (two-tailed Student's t test).

Role of the K99 homolog of C. rodentium in colonization of mice.

K99 is a fimbrial adhesin of certain ETEC strains that mediates bacterial attachment to the small intestines of neonatal calves, lambs, and piglets and is an essential virulence determinant of these bacteria (19, 20). The detection of ORFs in C. rodentium that are homologous to the genes encoding K99 suggested that C. rodentium may produce a K99-like adhesin that is required for virulence. This suggestion was reinforced by the observation that the K99 homolog was regulated by RegA and by the observation that in regA mutants there was a pronounced reduction in colonizing ability. To determine if C. rodentium requires the K99 homolog to colonize the mouse intestine, we constructed a K99 homolog mutant, EMH3, and examined its ability to infect mice. In single-infection experiments, the mean concentration of EMH3 10 days after inoculation was 6 × 108 CFU/g feces, which was similar to the concentration of the wild-type strain (4 × 108 CFU/g) at the same time (Fig. 6). Although the timing and extent of maximal fecal excretion for EMH3 did not differ from the timing and extent of maximal fecal excretion for the wild-type strain, EMH3 was cleared somewhat more effectively than the wild-type strain, and the number of CFU of EMH3 recovered from the feces 15 to 20 days after inoculation was significantly lower than the number of CFU of the wild-type strain recovered (P < 0.05, two-tailed Student's t test) (Fig. 6). Although modest, the differences in colonization during the later stages of infection were reproducible in independent experiments. Given its apparent role in virulence, we designated the operon encoding the K99 fimbrial homolog kfc (K99-like factor involved in Citrobacter colonization). Importantly, however, the attenuation of kfc mutant EMH3 was not nearly as pronounced as that of regA mutant EMH1, and in mixed-infection studies, EMH3 was not outcompeted by strain ICC169 (CI, >0.5).

To measure possible differences in colonization that may have occurred at times other than the standard sampling time (7 days), the mixed-infection studies were repeated, and bacterial colonization of the colon was measured at 3-day intervals up to 18 days after inoculation. At no time point did the numbers of CFU of the kfc mutant and wild-type bacteria recovered differ significantly, indicating that the two strains colonized equally well in a competitive environment. This weak contribution to virulence was confirmed by examination of a adcA kfc double-deletion mutant, whose colonization phenotype did not differ significantly from that of EMH3, which had a mutation only in kfc (data not shown).

Microarray analysis of the RegA regulon.

Although our results indicated that expression of both adcA and kfc was strongly stimulated by RegA, deletion of adcA and kfc from C. rodentium did not lead to the same degree of attenuation of the regA mutant, suggesting that there are additional factors that are regulated by RegA and contribute to the ability of C. rodentium to colonize mice.

To identify more target gene candidates for RegA, we compared the genome-wide transcription profiles of strains expressing and lacking RegA by using oligonucleotide microarrays. Yang et al. (53) previously reported that bicarbonate acts as an environmental stimulus for RegA-mediated activation; therefore, the transcription profiles of regA deletion mutant EMH1 were compared to those of RegA-expressing strain EMH1(pEH6) in the presence and absence of bicarbonate. Altogether, two comparisons were performed, resulting in eight microarray data sets.

Fifty-five of the ORFs showed a >2-fold increase in expression under both culture conditions, and Table 5 shows 17 ORFs that exhibited a >5-fold increase. The finding that transcription of kfc and adcA was strongly upregulated in the presence of bicarbonate was in agreement with the results of the β-galactosidase assays using promoter fusions performed in DMEM, which contains bicarbonate (44 mM). The results of the microarray analysis were also in complete agreement for the promoters that were negative in the β-galactosidase assay (namely, ler, sepZ, orf12, sepL, cfcA, and efa1). Interestingly, the expression of two ORFs, ROD3421 and ROD16201, which encode homologs of putative colonization factors, Aap and SfaA, was also dramatically increased. These results indicate that RegA is a global regulator that activates multiple genes involved in colonization and virulence.

TABLE 5.

Genes strongly activated by RegA identified by microarray analysis

| ORF(s)a | Increase (fold)b

|

Product | |

|---|---|---|---|

| LB medium | LB medium + bicarbonate | ||

| ROD3421 | 9 | 126 | Homolog of Aap (dispersin) of EAEC and virulence factor CexE of ETEC (accession no. 2JVU_A and ABM92275) |

| ROD3431, ROD3451, ROD3461, ROD3471, ROD3481 | 2 | 12 | Homolog of the Aat ABC transporter of EAEC (accession no. AY351860) |

| ROD15971 | 1 | 5 | 65% identity and 83% similarity to unknown protein of E. coli O157:H7 (accession no. NP_287725) |

| ROD16181 | 1 | 11 | 69% identity and 80% similarity to unknown protein encoded by prophage CP-933K E. coli O157:H7 (accession no. AAG55113) |

| ROD16201 | 5 | 23 | Homolog of porin protein SfpA of Y. enterocolitica (accession no. ABF0643) |

| ROD41031, ROD41041, ROD41051 | 1 | 8 | Gene cluster encoding an unknown protein and homologs of the HlyD and HlyB secretion proteins of Shewanella woodyi (accession no. ACA88067 and ACA88066) |

| ROD41241, ROD41261, ROD41271, ROD41291 | 1 | 16 | Kfcc |

| ROD41301 | 1 | 20 | AdcAc |

| ROD41311 | 13 | 56 | Unknown ORF located immediately upstream of regA |

| ROR50001 | 1 | 5 | Homolog of a putative virulence-related PagC-like membrane protein of E. coli O157:H7 (accession no. NP_289546) |

ORF designations were obtained from http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Projects/C_rodentium/C_rod_genome_CDS.tab.

The increases were derived from the average log2 ratio of the transcript levels for RegA+ strain EMH1(pEH6) to the transcript levels for the RegA− strain in the absence or presence of 45 mM bicarbonate (a value of 1 indicates no change).

Determined in this study.

DISCUSSION

The AraC family of regulators includes more than 100 proteins, the majority of which are positive transcriptional activators, which typically regulate carbon metabolism, stress responses, or virulence (15). Members of this family which regulate the synthesis of virulence factors are found mainly in bacteria that colonize mucosal surfaces, where they act by stimulating the synthesis of proteins involved in adhesion, invasion, capsule synthesis, or iron uptake (12). The AraC-like regulators which show homology to RegA include the Rns protein of ETEC, which activates synthesis of the CS1, CS2, CS3, and CS4 pili (8), and PerA of EPEC. The latter is a global regulator which stimulates the production of bundle-forming pili (17), mediates activation of its own promoter (26), and functions as part of a regulatory cascade by activating ler expression in the LEE1 operon (27). Based on sequence similarity, we hypothesized that RegA may function in a similar fashion to activate expression of virulence determinants, specifically fimbriae and LEE-encoded factors. However, investigation of promoter-lacZ transcriptional fusions constructed using known virulence determinants of C. rodentium showed that RegA did not directly activate any of these genes. By contrast, RegA did strongly stimulate the transcription of the following two adjacent gene loci encoding putative colonization factors: adcA, a homolog of aidA which encodes the autotransporter involved in diffuse adherence of diarrhea-associated E. coli, and the kfc operon, a putative operon homologous to the operon for the K99 fimbriae of ETEC (24).

Members of the autotransporter family of exported proteins in gram-negative bacteria have multiple roles in bacterial pathogenesis (22). The subfamily of autotransporters named for the adhesin involved in diffuse adherence, AIDA (3, 4), contains some of the best-characterized autotransporter proteins (18). In addition to specialized roles, such as adhesion to mammalian cells (4, 23), members of this subfamily are capable of mediating bacterial aggregation via self-association and are highly efficient initiators of bacterial biofilm formation (22, 44). Bacterial aggregation helps bacteria survive during passage through the stomach and enhances the infectivity of Vibrio cholerae (54), while AIDA-expressing E. coli biofilms are resistant to detergents and hydrodynamic shear forces (44), suggesting that these traits are closely associated with bacterial virulence and persistence.

In vitro characterization of AdcA of C. rodentium showed that this putative autotransporter can function as an adhesin by mediating autoaggregation and adherence to mammalian cells when it is expressed by a laboratory strain of E. coli. However, deletion of adcA from C. rodentium caused no significant reduction in the ability of C. rodentium to colonize the mouse intestine, indicating that, on its own, AdcA does not play a major role in colonization.

In this study, we also identified a cluster of genes (kfc) homologous to the genes encoding the K99 fimbriae of ETEC, whose transcription was strongly stimulated by RegA. Although it seemed likely that this operon may play a role in colonization, infection of mice with a kfc deletion mutant showed only that the mutant was cleared only slightly more efficiently than the wild type. Importantly, the kfc mutant was far less attenuated in terms of its colonizing ability than the regA mutant. This observation and the finding that a adcA kfc double-deletion mutant was no more attenuated than the kfc single mutant suggested that RegA regulates additional factors which are essential for normal colonization of mice by C. rodentium.

Using microarray analysis, we identified over 50 new targets whose expression was activated by RegA. The majority of these targets appear to have been horizontally acquired as they were flanked by insertion sequences and transposases. None of the transcriptional units which were upregulated more than fivefold encoded housekeeping proteins; instead, they encoded surface proteins, secreted factors, and their transporters. Consistent with our previous observation that bicarbonate, which is abundant in the intestinal tract, is an environmental signal for RegA-mediated activation of adcA and kfc (53), we found that bicarbonate also stimulated the transcription of all of the RegA-regulated genes identified by our microarray analysis.

The gene target most highly upregulated by RegA in C. rodentium was ROD3421 (Table 5). Transcription of this ORF was activated 9- and 126-fold by RegA alone and by RegA plus bicarbonate, respectively. ROD3421 codes for a putative 122-amino-acid protein which is a homolog of the Aap dispersin of EAEC and the CexE virulence factor of ETEC (35, 43). Aap and CexE appear to be involved in colonization and virulence of EAEC and ETEC and are upregulated by the AraC-like regulators AggR and Rns, respectively (35, 43).

Immediately adjacent to the ROD3421 locus is a gene cluster which includes ORFs ROD3431, ROD3451, ROD3461, ROD3471, and ROD3481. Expression of this transcriptional unit is weakly activated by RegA alone (2-fold) and strongly stimulated by RegA and bicarbonate (12-fold) (Table 5). The products of this gene cluster exhibit extensive homology to the Aat ABC transporter complex of EAEC, which is responsible for export of the Aap dispersin onto the cell surface. (34). Like the aap gene, the aat gene cluster is positively regulated by the AggR activator (34).

The ROD16201 locus was upregulated 23-fold by RegA and bicarbonate (Table 5). This locus encodes a protein homologous to the SfpA protein (systemic factor protein A) of Yersinia enterocolitica. SfpA is a membrane porin protein and is required for sustained colonization of Y. enterocolitica in mice (28).

The gene cluster consisting of ROD41031, ROD41041, and ROD41051 encodes an unknown protein, as well as homologs of HlyD and HlyB, which are key components of the type I protein secretion pathway (5). This secretion pathway is responsible for the export of HlyA toxin (hemolysin). Whereas hlyA and hlyC (encoding a protein involved in the posttranslational modification of HlyA) together with hlyB and hlyD form a single operon in uropathogenic E. coli (5), the hlyA and hlyC genes form a separate transcriptional unit in C. rodentium. Transcription of hlyB-hlyD and hlyA-hlyC were activated eight- and twofold, respectively, by RegA, and the upregulation of both operons was bicarbonate dependent (Table 5 and results not shown).

ROD41311 is located immediately upstream of the regA gene. Transcription of this locus was strongly upregulated by RegA both in the absence and in the presence of bicarbonate (Table 5). Part of this ORF codes for a polypeptide which is homologous to the region 4 segment of the sigma 70 subunit of E. coli RNA polymerase. Our preliminary data showed that the promoter of this gene is responsible for the expression and regulation of the regA gene (A. Tan and J. Yang, unpublished results).

In summary, we showed that the RegA regulatory protein is an essential virulence determinant of C. rodentium. Although RegA strongly activated expression of two adjacent operons, adcA and kfc, which code for a putative autotransporter and K99-like fimbriae, respectively, these factors did not play an important role in colonization. Microarray analysis identified more than 50 additional unlinked gene targets whose expression was upregulated by RegA in the presence of bicarbonate. These newly identified ORFs encode homologs of known colonization and virulence factors and proteins with unknown functions. Experiments are currently under way to elucidate the contribution of each of the putative virulence operons to the pathogenesis of C. rodentium infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rosanna Mundy (Imperial College, London, United Kingdom) for constructing the STM library of C. rodentium, Judyta Praszkier (The University of Melbourne) for the gift of plasmids used in this study, Sau Fung Lee (University of Melbourne) for FAS data, and Danijela Krmek for assisting with mouse experiments.

This work was supported by grants from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the Australian Research Council. E. Hart was the recipient of a Melbourne Research Scholarship. M. Tauschek was supported by a Peter Doherty Fellowship of the Australian National Health and Medical Council.

Editor: S. R. Blanke

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 September 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Autret, N., and A. Charbit. 2005. Lessons from signature-tagged mutagenesis on the infectious mechanisms of pathogenic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 29703-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barthold, S. W. 1980. The microbiology of transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Lab. Anim. Sci. 30167-173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benz, I., and M. A. Schmidt. 1989. Cloning and expression of an adhesin (AIDA-I) involved in diffuse adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 571506-1511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Benz, I., and M. A. Schmidt. 1990. Diffuse adherence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strains. Res. Microbiol. 141785-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhakdi, S., N. Mackman, G. Menestrina, L. Gray, F. Hugo, W. Seeger, and I. B. Holland. 1988. The hemolysin of Escherichia coli. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 4135-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bieber, D., S. W. Ramer, C. Y. Wu, W. J. Murray, T. Tobe, R. Fernandez, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1998. Type IV pili, transient bacterial aggregates, and virulence of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 2802114-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caron, J., L. M. Coffield, and J. R. Scott. 1989. A plasmid-encoded regulatory gene, rns, required for expression of the CS1 and CS2 adhesins of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86963-967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caron, J., and J. R. Scott. 1990. A rns-like regulatory gene for colonization factor antigen I (CFA/I) that controls expression of CFA/I pilin. Infect. Immun. 58874-878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Datsenko, K. A., and B. L. Wanner. 2000. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 976640-6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deng, W., Y. Li, B. A. Vallance, and B. B. Finlay. 2001. Locus of enterocyte effacement from Citrobacter rodentium: sequence analysis and evidence for horizontal transfer among attaching and effacing pathogens. Infect. Immun. 696323-6335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elliott, S. J., L. A. Wainwright, T. K. McDaniel, K. G. Jarvis, Y. K. Deng, L. C. Lai, B. P. McNamara, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1998. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli E2348/69. Mol. Microbiol. 281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finlay, B. B., and S. Falkow. 1997. Common themes in microbial pathogenicity revisited. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61136-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frankel, G., A. D. Phillips, I. Rosenshine, G. Dougan, J. B. Kaper, and S. Knutton. 1998. Enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli: more subversive elements. Mol. Microbiol. 30911-921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freter, R., P. C. O'Brien, and M. S. Macsai. 1981. Role of chemotaxis in the association of motile bacteria with intestinal mucosa: in vivo studies. Infect. Immun. 34234-240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gallegos, M. T., R. Schleif, A. Bairoch, K. Hofmann, and J. L. Ramos. 1997. Arac/XylS family of transcriptional regulators. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 61393-410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Giron, J. A., A. S. Ho, and G. K. Schoolnik. 1991. An inducible bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Science 254710-713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gomez-Duarte, O. G., and J. B. Kaper. 1995. A plasmid-encoded regulatory region activates chromosomal eaeA expression in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Infect. Immun. 631767-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Henderson, I. R., F. Navarro-Garcia, M. Desvaux, R. C. Fernandez, and D. Ala'Aldeen. 2004. Type V protein secretion pathway: the autotransporter story. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68692-744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Isaacson, R. E., B. Nagy, and H. W. Moon. 1977. Colonization of porcine small intestine by Escherichia coli: colonization and adhesion factors of pig enteropathogens that lack K88. J. Infect. Dis. 135531-539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones, G. W., and R. E. Isaacson. 1983. Proteinaceous bacterial adhesins and their receptors. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 10229-260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kelly, M., E. Hart, R. Mundy, O. Marches, S. Wiles, L. Badea, S. Luck, M. Tauschek, G. Frankel, R. M. Robins-Browne, and E. L. Hartland. 2006. Essential role of the type III secretion system effector NleB in colonization of mice by Citrobacter rodentium. Infect. Immun. 742328-2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klemm, P., R. M. Vejborg, and O. Sherlock. 2006. Self-associating autotransporters, SAATs: functional and structural similarities. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 296187-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Laarmann, S., and M. A. Schmidt. 2003. The Escherichia coli AIDA autotransporter adhesin recognizes an integral membrane glycoprotein as receptor. Microbiology 1491871-1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee, J. H., and R. E. Isaacson. 1995. Expression of the gene cluster associated with the Escherichia coli pilus adhesin K99. Infect. Immun. 634143-4149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levine, M. M., J. P. Nataro, H. Karch, M. M. Baldini, J. B. Kaper, R. E. Black, M. L. Clements, and A. D. O'Brien. 1985. The diarrheal response of humans to some classic serotypes of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is dependent on a plasmid encoding an enteroadhesiveness factor. J. Infect. Dis. 152550-559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martinez-Laguna, Y., E. Calva, and J. L. Puente. 1999. Autoactivation and environmental regulation of bfpT expression, the gene coding for the transcriptional activator of bfpA in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 33153-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mellies, J. L., S. J. Elliott, V. Sperandio, M. S. Donnenberg, and J. B. Kaper. 1999. The Per regulon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a regulatory cascade and a novel transcriptional activator, the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler). Mol. Microbiol. 33296-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mildiner-Earley, S., and V. L. Miller. 2006. Characterization of a novel porin involved in systemic Yersinia enterocolitica infection. Infect. Immun. 744361-4365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller, J. H. 1974. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 30.Mundy, R., D. Pickard, R. K. Wilson, C. P. Simmons, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 2003. Identification of a novel type IV pilus gene cluster required for gastrointestinal colonization of Citrobacter rodentium Mol. Microbiol. 48795-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nataro, J. P., and J. B. Kaper. 1998. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11142-201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nataro, J. P., D. Yikang, D. Yingkang, and K. Walker. 1994. AggR, a transcriptional activator of aggregative adherence fimbria I expression in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1764691-4699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nicholls, L., T. H. Grant, and R. M. Robins-Browne. 2000. Identification of a novel genetic locus that is required for in vitro adhesion of a clinical isolate of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 35275-288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nishi, J., J. Sheikh, K. Mizuguchi, B. Luisi, V. Burland, A. Boutin, D. J. Rose, F. R. Blattner, and J. P. Nataro. 2003. The export of coat protein from enteroaggregative Escherichia coli by a specific ATP-binding cassette transporter system. J. Biol. Chem. 27845680-45689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pilonieta, M. C., M. D. Bodero, and G. P. Munson. 2007. CfaD-dependent expression of a novel extracytoplasmic protein from enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1895060-5067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Porter, M. E., P. Mitchell, A. J. Roe, A. Free, D. G. Smith, and D. L. Gally. 2004. Direct and indirect transcriptional activation of virulence genes by an AraC-like protein, PerA from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol. Microbiol. 541117-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Praszkier, J., I. W. Wilson, and A. J. Pittard. 1992. Mutations affecting translational coupling between the rep genes of an IncB miniplasmid. J. Bacteriol. 1742376-2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell, R. M., F. C. Sharp, D. A. Rasko, and V. Sperandio. 2007. QseA and GrlR/GrlA regulation of the locus of enterocyte effacement genes in enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1895387-5392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 40.Schauer, D. B., and S. Falkow. 1993. Attaching and effacing locus of a Citrobacter freundii biotype that causes transmissible murine colonic hyperplasia. Infect. Immun. 612486-2492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schembri, M. A., D. Dalsgaard, and P. Klemm. 2004. Capsule shields the function of short bacterial adhesins. J. Bacteriol. 1861249-1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shea, J. E., J. D. Santangelo, and R. G. Feldman. 2000. Signature-tagged mutagenesis in the identification of virulence genes in pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 3451-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sheikh, J., J. R. Czeczulin, S. Harrington, S. Hicks, I. R. Henderson, C. Le Bouguenec, P. Gounon, A. Phillips, and J. P. Nataro. 2002. A novel dispersin protein in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J. Clin. Investig. 1101329-1337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sherlock, O., M. A. Schembri, A. Reisner, and P. Klemm. 2004. Novel roles for the AIDA adhesin from diarrheagenic Escherichia coli: cell aggregation and biofilm formation. J. Bacteriol. 1868058-8065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smyth, G. K. 2005. Limma: linear models for microarray data, p. 397-420. In R. Gentleman, V. Carey, S. Dudoit, R. Irizarry, and W. Huber (ed.), Bioinformatics and computational biology solutions using R and Bioconductor. Springer, New York, NY.

- 46.Smyth, G. K. 2004. Linear models and empirical Bayes methods for assessing differential expression in microarray experiments. Stat. Appl. Genet. Mol. Biol. 3article 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smyth, G. K., and T. Speed. 2003. Normalization of cDNA microarray data. Methods 31265-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tobe, T., and C. Sasakawa. 2001. Role of bundle-forming pilus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli in host cell adherence and in microcolony development. Cell. Microbiol. 3579-585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Twigg, A. J., and D. Sherratt. 1980. Trans-complementable copy-number mutants of plasmid ColE1. Nature 283216-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulett, G. C., R. I. Webb, and M. A. Schembri. 2006. Antigen-43-mediated autoaggregation impairs motility in Escherichia coli. Microbiology 1522101-2110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vial, P. A., J. J. Mathewson, H. L. DuPont, L. Guers, and M. M. Levine. 1990. Comparison of two assay methods for patterns of adherence to HEp-2 cells of Escherichia coli from patients with diarrhea. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28882-885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wiles, S., S. Clare, J. Harker, A. Huett, D. Young, G. Dougan, and G. Frankel. 2005. Corrigendum: organ specificity, colonization and clearance dynamics in vivo following oral challenge with the murine pathogen Citrobacter rodentium. Cell. Microbiol. 7459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yang, J., E. Hart, M. Tauschek, G. D. Price, E. L. Hartland, R. A. Strugnell, and R. Robins-Browne. 2008. Bicarbonate-mediated transcriptional activation of divergent operons by the virulence regulatory protein, RegA, from Citrobacter rodentium Mol. Microbiol. 68314-327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhu, J., and J. J. Mekalanos. 2003. Quorum sensing-dependent biofilms enhance colonization in Vibrio cholerae. Dev. Cell 5647-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]