Abstract

The replacement therapy using recombinant human FVIII (rFVIII) is the first line of therapy for hemophilia A. Approximately 15-30% of the patients develop inhibitory antibodies. Recently, we reported that liposomes composed of phosphatidylserine (PS) could reduce the immunogenicity of rFVIII. However, PS containing liposomal-rFVIII is likely to reduce the systemic exposure and efficacy of FVIII due to rapid uptake of the PS containing liposomes by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). Here, we investigated whether phosphatidylserine (PS) liposomes containing polyethyleneglycol (PEG) (PEGylated), could reduce the immunogenicity of rFVIII and reverse the reduction in systemic exposure of rFVIII. Animals given PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII had lower total and inhibitory anti-rFVIII antibody titers, compared to animals treated with rFVIII alone. The mean stimulation index of CD4+ T-cells from animals given PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII also was lower than for animals that were given rFVIII alone. Pharmacokinetic studies following intravenous dosing indicated that the systemic exposure (area under the activity curve, AUAC0-24h) of PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII was ∼59 IU/mL×h and significantly higher than that of non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII (AUAC0-24h∼36 IU/mL×h). Based on these studies, we speculate that PEGylated PS-containing liposomal rFVIII may improve efficacy of rFVIII.

Keywords: hemophilia A, recombinant FVIII, immunogenicity, inhibitory antibodies, PEGylated-liposomes

INTRODUCTION

Hemophilia A is an inherited bleeding disorder characterized by the deficiency or dysfunction of factor VIII (FVIII) activity.1,2 FVIII serves as a critical cofactor in the intrinsic pathway of the coagulation cascade.3 Replacement therapy with recombinant human FVIII (rFVIII) or plasma-derived FVIII is the most common therapy employed in controlling bleeding episodes.4 However, the induction of neutralizing antibodies (or inhibitory antibodies) against the administered protein in approximately 15-30% of patients complicates therapy.4-6 Several treatment strategies are followed clinically to treat patients with inhibitors, which include administration of bypassing agents such as recombinant factor VIIa (rFVIIa)7 or high doses of FVIII (ITT, immune tolerance therapy).8 Nevertheless, inhibitory antibodies represent a significant challenge in the efficient management of the disease and alternate strategies are warranted.

FVIII is a large multi-domain glycoprotein consisting of domains A1, A2, B, A3, C1, and C2.9,10 Epitope mapping experiments have revealed that anti-FVIII antibodies mainly target defined regions in the A2 (heavy chain), A3 and C2 domains (light chain) of FVIII.11,12 The inhibitor epitope within the A2 domain has been mapped to residues Arg484-Ile-508.13,14 Antibodies targeting this region have been shown to inhibit the activated form of FVIII (FVIIIa) by blocking interaction of A2 domain with factor IXa (FIXa).15 The major epitope determinant within the A3 domain comprises of residues 1811-1818 and inhibitors against this region also prevent the interaction of FVIII with FIXa resulting in loss of cofactor activity.16 The epitope regions within the C2 domain, have been mapped to residues 2181-231217,18 which encompass the immunodominant, universal CD4+ epitopes; 2191-2210, 2241-2290, 2291-2330.19,20 Antibodies against the C2 domain interfere with the binding of FVIII to platelet membrane surface which is rich in phosphatidylserine (PS) that is essential for the amplification of the coagulation cascade.7

Previously we reported that subcutaneous administration of rFVIII in association with PS-containing liposomes, which interact specifically with the C2 domain of FVIII, resulted in reduced immunogenicity of the protein in a murine model for hemophilia A (Ramani et al., in press). Further, liposomal association also suggested the possibility of s.c. delivery for FVIII. However, intravenous (i.v.) administration of PS containing liposomal-rFVIII could reduce systemic exposure of the protein due to rapid clearance of the liposomes from circulation, by the cells of the reticuloendothelial system (RES).21 Thus, administration of rFVIII in association with PS containing liposomes could reduce the efficacy of the treatment. Incorporation of PEG has been shown to prolong the in vivo t1/2 and systemic exposure of liposomes by interfering with their uptake by RES.21 Therefore, in this manuscript, we evaluated the hypotheses that administration of rFVIII in association with PEGylated FVIII-PS complex containing liposomes could reduce the immunogenicity and improve the pharmacokinetic properties of exposure and apparent circulation half-life (t1/2) of the protein in vivo. The passive transfer of PEG was attempted to maintain the complexation between FVIII and liposomal bilayer structure and this configuration is distinctly different from noncovalent association of FVIII with PEGylated, liposomes composed of phosphatidylcholine.22 Baru et al.22 have utilized preformed PEG containing liposomes to form complex with FVIII and in this configuration, the protein is neither encapsulated in the lumen of liposomes nor interacted/intercalated with the bilayer. In this study, the protein is associated with liposomes with hydrophobic amino acids in the C2 domain intercalated in the lipid bilayer. The data indicate that administration of PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII reduces the immunogenicity of the protein. The systemic exposure (area under the activity curve, AUAC0-24h) of PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII (∼59 IU/mL×h) was significantly higher than that of non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII (AUAC0-24h∼36 IU/mL×h) and comparable to rFVIII (AUAC0-24h ∼57 IU/mL×h). The apparent t1/2 increased from 2.6 h for rFVIII to 3.5 h for PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Materials

rFVIII (Baxter HealthCare, Carlsbad, CA) was used as the antigen. Normal coagulation control plasma and FVIII deficient plasma for the activity assay was purchased from Trinity Biotech (Co Wicklow, Ireland). Brain phosphatidylserine (BPS), dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine (DMPC) and 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethyleneglycol)-2000] (DMPE-PEG2000) dissolved in chloroform were obtained from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL), stored at -70°C and used without further purification. Sterile, pyrogen free water was purchased from Henry Schein, Inc. (Melville, NY). Monoclonal antibody ESH 8 was obtained from American Diagnostica, Inc. (Greenwich, CT). IgG free bovine serum albumin (BSA), diethanolamine and acetone was obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (Ig, IgM + IgG + IgA, H + L) conjugated to alkaline phosphatase was from Southern Biotechnology Associates, Inc. (Birmingham, AL). p-Nitrophenyl phosphate disodium salt was purchased from Pierce (Rockford, IL). 1,6-diphenyl-1, 3,5-hexatriene (DPH) was purchased from Molecular Probes, Inc. (Eugene, OR). RPMI-1640 culture medium, penicillin, streptomycin, l-glutamine, 2-mercaptoethanol and Polymyxin B were all obtained from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). 3H-thymidine was obtained from Perkin-Elmer, Inc. (Boston, MA). All other buffer salts used in the study were obtained from Fisher Scientific (Fairlawn, NJ).

Determination of Critical Micelle Concentration (CMC) of DMPE-PEG2000

CMC of DMPE-PEG2000 was determined using the fluorescence probe DPH as described previously.23 Briefly, DPH solution (2 μL, [DPH] 30 μM in acetone) was added to various concentrations of 1 mL DMPE-PEG2000 followed by incubation at 37°C for 2 h. The fluorescence intensity of the dispersions was measured using a PTI fluorometer (Photon Technology International, Lawrenceville, NJ) equipped with a xenon arc lamp. The excitation wavelength (Ex) of the probe was set at 360 nm and emission (Em) was monitored at 430 nm. The concentration of the dispersion where the fluorescence intensity increased abruptly was defined as the CMC and was found to be ∼100 μM.

Preparation of Polyethylene Glycol Coated (PEGylated) PS Liposomes

The required amounts of DMPC (Tc∼23°C) and BPS (Tc∼6-8°C) were dissolved in chloroform and the solvent was evaporated using a rotary evaporator (Buchi-R200, Fisher Scientific) to form a thin film on the walls of a round-bottomed flask. Liposomes were formed by rehydrating the thin lipid film in Tris buffer (TB, 300 or 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2·2H2O, pH 7.0, prepared in sterile, pyrogen-free water) at 37°C. The molar ratios of the lipids used in the present study were DMPC: BPS (70: 30 mol%) and the protein to lipid ratio was maintained at 1:10,000 for all the experiments. The liposomes were extruded through triple-stacked 200 nm polycarbonate membrane 8-10 times using a high-pressure extruder (Mico, Inc., Middleton, WI) at a pressure of ∼200-250 psi. Following sterilization of liposomes by passing through a 0.22 μm millex™-GP filter unit (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, MA), the lipid recovery was estimated by determination of phosphorous content by the method of Bartlett.24 The size distribution of the liposomes was determined using a Nicomp Model CW 380 particle size analyzer (Particle Sizing Systems, Santa Barbara, CA) as described previously.25 The sized liposomes were associated with appropriate amount of rFVIII by incubating at 37°C with gentle swirling for 30 min.

PEGylation of the protein-liposome mixture was achieved by passive transfer. The protein-liposome mixture was added to a dry film of DMPE-PEG2000 and incubated at 25°C for 1 h to facilitate the transfer of PEGylated lipid to liposomes. It was ensured that the volume of protein-liposome mixture added to the dry PEG film did not result in the formation of PEG micelles (CMC of DMPE-PEG2000 was ∼100μM) as micelle formation may contribute towards inefficient incorporation of PEG in liposomes. The final expected mol% of PEG in the preparation was 4 mol% of the total lipid and the incorporation of PEG was qualitatively confirmed by MALDI-TOF (data not shown). To estimate the amount of protein associated with PEGylated liposomes, free protein was separated from PEGylated liposome associated protein using a discontinuous dextran density gradient centrifugation technique as described previously.26 The percent of active protein associated was determined by the one-stage APTT assay.27 The percent association was estimated to be ∼27.6±9.6% (±SEM, n=5). Samples were used immediately after preparation.

Theoretical Considerations for the Incorporation of Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) in Liposomes

PEG was incorporated into the liposomes after associating the protein to the liposomes and not during the preparation of the lipid film. This method of PEG incorporation was chosen to circumvent the possibility of PEG interfering with protein binding to PS containing liposomes due to steric hindrance. While it is possible that the efficiency of PEG insertion might decrease due to presence of protein on the surface of the liposomes, theoretical considerations based on electron crystallography and molecular modeling studies suggest that sufficient PEG molecules can be incorporated and is discussed below.

The mean diameter of the liposomes used in the study was 200 nm. Under the assumption that the bilayer thickness is 40 Å and the area occupied by one phospholipid molecule is 70 Å2, the number of vesicles/μmol of phospholipid was estimated to be ∼1.8×1012 vesicles. For immunization studies, 2 μg of protein was administered per animal and based on the molar excess of protein to lipid used (1:10,000), each animal received ∼71.4 nmol of lipid. If all of the protein molecules (in 2 μg) associated with the liposomes, that is, the efficiency of association of the protein to the liposomes was 100%, the theoretical maximum of protein molecule/vesicle was estimated to be ∼33. Three-dimensional structure of membrane bound FVIII derived by electron crystallography revealed that FVIII domains have a compact arrangement in which the C2 domain of the protein interacts with the phospholipids.28 Based on the unit cell dimension for the two-dimensional map of FVIII (a=8.1nm, b=7 nm and γ=113°) and the total surface area of the 200 nm liposomes, we estimated that the maximum number of FVIII molecules that could be packed on the surface of the liposomes is ∼2400. However, given that the utmost number of protein molecules/vesicle was projected to be ∼33 based on the protein to lipid ratio employed in our studies, the above theoretical assessment suggest that the majority of the surface of the liposomes is still unoccupied and would be available for coating by PEG.

In Vivo Studies

Animals

Equal numbers of adult male and female hemophilic mice (with a target deletion in exon-16 of the FVIII gene), aged 8-12 weeks were used for the immunization studies and male mice were used for pharmacokinetic studies.

Blood Sampling

Blood samples obtained by cardiac puncture were added at a 10:1(v/v) ratio to acid citrate dextrose (ACD, containing 85 mM sodium citrate, 110 mM d-glucose and 71 mM citric acid). Plasma was separated by centrifugation and samples were stored at -80°C until analysis. All studies were performed in accordance with the guidelines of Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University at Buffalo.

Immunization Protocol

Immunization of FVIII knockout mice (at least n=12 per treatment group with total n≥36) consisted of four subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of rFVIII or PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII (2 μg corresponding to 10 IU based on activity) at weekly intervals. Blood samples were only obtained at the end of 6 weeks.

Antibody Measurements

Detection of Total Anti-rFVIII Antibodies

Total anti-rFVIII antibody titers were determined by ELISA as described previously.29 Briefly, Nunc-Maxisorb 96-well plates were coated with 50 μL of 2.5 μg/mL of rFVIII in carbonate buffer (0.2 M, pH 9.4) and incubated at 4°C overnight. The plates were then washed six times with 100 μl of phosphate buffer (PB; 10 mM Na2HPO4, 1.8 mM KH2PO4, 14 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, pH 7.4) containing 0.05% Tween-20 (PBT). Non-specific protein binding sites were blocked by incubation with 200 μL of PB buffer containing 1% bovine serum albumin (PBA) for 2 h at room temperature. The plates were then washed six times with PBT and 50 μL of serial dilutions of mouse plasma samples or standard solutions were added and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Standards consisted of 25-150 μg/mL of ESH8, a monoclonal murine anti-human FVIII IgG that binds to the C2 domain of FVIII. The plates were washed six times with PBT and incubated at room temperature for 1 h with 50 μL of a 1:1000 dilution of alkaline phosphatase/goat anti-mouse Ig conjugate in PBA. The plates were washed six times with PBT and 100 μL of 1 mg/mL p-nitrophenyl phosphate solution in diethanolamine buffer (consisting of 1 M diethanolamine, 0.5 mM MgCl2) was added. The plates were incubated at room temperature for 30 min and the reaction was quenched by the addition of 100 μL of 3 N NaOH. The alkaline phosphatase reaction product was determined by absorbance at 405 nm using a Spectramax plate reader (Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA). Antibody titers were expressed as follows: linear regression was performed on the absorbance values obtained with ESH8. Half the difference between the maximum and minimum predicted absorbance was calculated as the plate specific factor (PSF), that is, PSF=1/2 (Maximum-Minimum) predicted absorbance value. A linear regression of the plot of absorbance values versus log dilution (over the range of 1:100 to 1:40,000) was used to calculate the dilution that gave an optical density equal to the PSF. The dilution so obtained was considered the antibody titer of the sample.

Detection of Inhibitory Anti-rFVIII Antibodies

Inhibitory (neutralizing) anti-rFVIII antibodies were detected using the Nijmegen modification of the Bethesda assay. Residual rFVIII activity was measured using the one stage APTT assay. Each dilution (1:2 to 1:32,000) was tested in duplicate. One Bethesda Unit (BU) is the inhibitory activity that produces 50% inhibition of rFVIII activity. The point of 50% inhibition was determined by linear regression of those data points falling within the range of approx. 20-80% inhibition.

T-Cell Proliferation Studies and Cytokine Analysis

Female hemophilic mice, aged 8-12 weeks were immunized using two subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of rFVIII or rFVIII-liposomes (2 μg protein per injection) at weekly intervals. Control mice received no rFVIII. Animals were sacrificed 3 days after the second injection and the spleen was harvested as a source of T-cells. Spleen cells were depleted of CD8+ cells using magnetic beads coated with a rat anti-mouse monoclonal antibody for the Lyt 2 membrane antigen (Dynal Biotech, Oslo, Norway) expressed on CD8 cells, using the manufacturer’s protocol. The remaining cells (2×105cells/200 μL) were cultured in a 96-well flat-bottom plates with rFVIII (100 ng/well or 1000 ng/well) in complete RPMI-1640 culture medium containing 10,000 U/mL penicillin, 10 mg/mL streptomycin, 2.5 mM sodium pyruvate, 4 mM l-glutamine, 0.05 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 2 mg/mL Polymyxin B and 0.5% heat inactivated hemophilic mouse serum. One microcurie per well of 3H-thymidine (6.7 Ci/mmol) was added after 72 h of culture at 37°C. At the end of 16 h, the cells were harvested using a Micromate Harvester (Packard, Meriden, CT) and 3H-thymidine incorporation was measured using a TopCount™ microplate scintillation and luminescence counter (Packard Instrument Company). Treatment groups consisted of three replicate animals and cells from each individual mouse were tested in quadruplicate for antigen-dependent proliferation. The data was reported as a stimulation index (SI), which is the ratio of the average 3H-thymidine incorporation in the presence of the antigen to the average incorporation in the absence of the antigen. This approach normalized the data of each experiment and allows for comparison of experiments carried out at different times.

Cytokine Analysis

After 72 h of incubation, the supernatants of antigen-stimulated T-cells were collected and stored at -70°C until further analysis. The supernatant was analyzed by antibody capture ELISA (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). IFN-γ was measured as a representative Th1 cytokine and IL-10 was measured as a representative Th2 cytokine.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) Studies

Male hemophilic mice (20-26 g, 8-12 weeks old) received 10 IU/animal or 400 IU/Kg of rFVIII, non-PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII or PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII (in TB: 150 mM NaCl, 25 mM Tris, 5 mM CaCl2·2H2O, pH 7.0) as a single intravenous (i.v.) bolus injection via the penile vein. Blood samples were collected at 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 16, 24, 36 and 48 h post dose by cardiac puncture (n=2-3 mice/time point) and added to ACD. Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 5000g for 5 min at 4°C and stored at -70°C until analysis. Plasma samples were analyzed for the activity of the protein by the chromogenic assay (Coamatic FVIII, DiaPharma Group, West Chester, OH). The average values of activities of rFVIII at each time point were then utilized to estimate the pharmacokinetic parameters (exposure/area under the activity curve; AUAC0-t, apparent circulation half-life; t1/2) by noncompartmental analysis (NCA) using WinNonlin (Pharsight Corporation, Mountainview, CA).

Statistical Analysis

For immunogenicity studies, the lowest titer value in the control group was defined as the ‘minimum response value’ and this arbitrary value was usedto differentiate between the responders and nonresponders. Animals showing titer values greater than this defined value were considered as responders whereas, animals with titer values below this value were considered as nonresponders. Data was analyzed by ANOVA using Analyst Application of SAS (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC) or Minitab (Minitab, Inc., State College, PA). Dunnette’s posthoc multiple comparison test was used to detect significant differences (p<0.05). For PK studies, differences in systemic exposure between the two treatments were compared using the Bailer-Satterthwaite method.30

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Effect of PEGylated PS Containing Liposomes on Antibody Formation

Considering that FVIII interacts with PS rich platelet membrane surface via the C2 domain28,31 and that this domain consists of several immunodominant epitopes that have been implicated in the stimulation of the immune response,19 we hypothesized that administration of rFVIII in association with PEGylated-PS containing liposomes could potentially reduce the immunogenicity of rFVIII in a murine model for hemophilia A.

The murine model for hemophilia A has contributed significantly towards our understanding of the mechanism of immune response to exogenously administered rFVIII.31-33 The antibody response against rFVIII, detected in the hemophilic mouse strain has been shown to be very similar to that observed in patients. Further, as animal models are valuable in comparing immunogenicity of protein preparations,33 the relative immunogenicity of rFVIII in the absence and presence of PEGylated-PS containing liposomes was investigated in the murine hemophilic model. Total titers measured for animals given FVIII by i.v. administration was found to be lower and highly variable (3649±1799, SEM n=10) compared to s.c. route (13167±2042, SEM n=15) of administration. As the s.c. route of administration elicits higher antibody response compared to intravenous administration, this route of administration was used to amplify the immune response to establish statistical significance. Nonetheless, IgG sub type levels and mechanism of immune response against FVIII has been shown to be identical between these two routes of administration.32

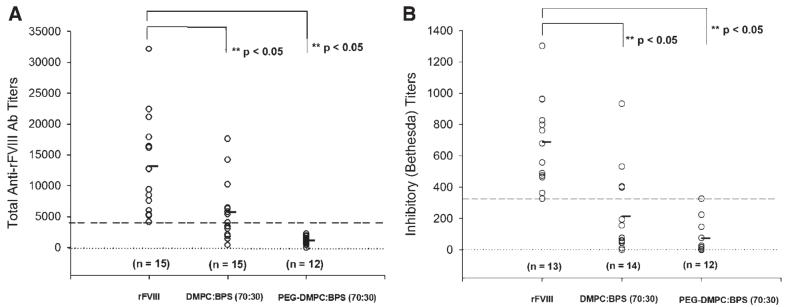

Upon administration of exogenous rFVIII, hemophilic patients develop an adaptive response as the rFVIII is seen as foreign or nonself protein.34 In order to investigate the effect of PEGylation on the development of antibodies, we measured the total anti-rFVIII antibody titers for animals given PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII. Animals treated with free rFVIII were used as a control. The lowest titer value amongst the control group was 4125. This value was used to distinguish between responders and nonresponders. The data is represented in Figure 1A. For comparison, the total antibody titers following administration of non-PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII (adapted from Ramani et al., in press) are also shown. Animals treated with PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII displayed significantly lower antibody titer (1123±190, ±SEM, n=12, p-value <0.05) in comparison to animals treated with rFVIII (13167±2042, ±SEM, n=15). These results indicate that antibody formation is reduced by ∼57% and ∼84% in the absence and presence of PEGylated liposomes respectively. Although, a statistically significant difference could not be established between the PEGylated and non-PEGylated liposomes, ∼47% of animals treated with non-PEGylated liposomal rFVIII responded to the formulation whereas, all the animals treated with PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII were nonresponders.

Figure 1.

(A) Total anti-FVIII antibody titers and (B) Inhibitory anti-rFVIII antibodies in hemophilic mice following administration of rFVIII in the absence and presence of PEGylated-liposomes comprised of DMPC: BPS (70:30) at the end of 6 weeks. Each point represents values from individual mouse that received treatment and the horizontal bar depicts the mean of the total antibody or inhibitory titers. For comparison purposes, data obtained following administration of rFVIII in the presence of non-PEGylated DMPC: BPS liposome is also displayed. Blood samples were obtained 2 weeks after the 4th injection. The total anti-FVIII antibody titers were determined by ELISA and inhibitory titers were determined by Bethesda Assay. Data was analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnette’s posthoc multiple comparison test to detect significant differences (p<0.05).

Inhibitory antibodies which interfere with the activity of the protein were detected using the Bethesda assay. Figure 1B shows the inhibitory antibody titers, expressed in Bethesda Units (BU) following rFVIII and PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII treatments at the end of 6 weeks. Animals treated with only rFVIII were used as a control. The data indicated that the inhibitory antibodies were significantly lower in the presence of PEGylated liposomes (74±31 BU/mL, ±SEM, n=12, p-value <0.05) in comparison to rFVIII alone (690±78 BU/mL, ±SEM, n=13). lowest value amongst control the group was 326. This value was used to distinguish between responders and nonresponders. These results indicated that PEGylated liposomes lowered the titers of antibodies that inactivate the protein. For comparison, the inhibitory titers following administration of non-PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII (adapted from Ramani et al., in press) are also shown. The data indicated that the mean inhibitory titers in the absence and presence of PEGylated liposomes were lowered by ∼69% and ∼89% respectively. The differences however, were not statistically different (p>0.05). Although, a statistically significant difference could not be established between the PEGylated and non-PEGylated liposomes, ∼29% of animals treated with non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII responded to the formulation. In comparison, all the animals treated with PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII were nonresponders. We also measured the inhibitory titers in animals following iv administration of PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII. The inhibitory titers for PEGylated liposomes displayed lower median titers, 491 (±SEM, n=10) compared to rFVIII 591 (±SEM, n=10), but statistical significance could not be established.

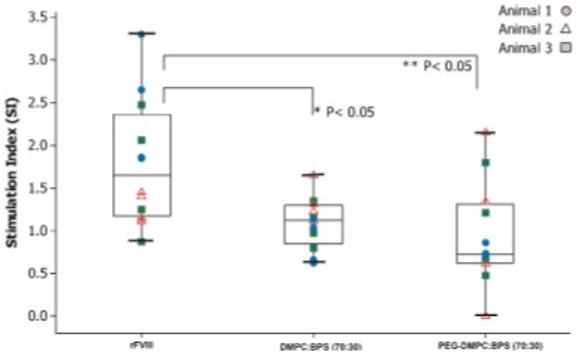

Stimulation of T-cells in vivo following immunization with PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII was evaluated by measuring the T-cell proliferation response to rFVIII challenge in vitro. The mean stimulation index of CD4+ T-cells isolated from animals receiving PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII treatment was lower relative to animals receiving rFVIII treatment alone (Fig. 2) and comparable to the observation in animals given non-PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII. The data suggests the possibility of differences in the T-cell clones that were stimulated for expansion depending upon whether animals were exposed to rFVIII in the presence and absence of PEGylated PS-containing liposomes.

Figure 2.

CD4+ T-cell proliferation response of hemophilic mice, represented as the stimulation index, to intact rFVIII (100 ng/well) carrying multiple immunodominant epitopes, following two subcutaneous doses of 2 μg rFVIII or PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII. For comparison purposes, data obtained following administration of rFVIII in the presence of non-PEGylated DMPC: BPS liposome is also displayed. Calculation of the stimulation index is described in Experimental Procedure Section. The data was generated using three animals per treatment group and samples in quadruplet per animal were analyzed for FVIII challenge. Inter-animal variability was found to be not significant (p>0.05) for all the treatment groups. Hence, all the data points in each treatment group were combined for further statistical analysis. Data was analyzed using one-way ANOVA (p<0.05). Con A was used as positive control.

Th1 and Th2 cells modulate immune response against protein antigens by secretion of cytokines that are mutually antagonistic in nature. While Th1 cytokines such as interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) primarily participate in cell-mediated immune response, Th2 cytokines such as interleukin-10 (IL-10) stimulate proliferation and differentiation of B-cells and are involved in class switching of Ig.5 Most anti-FVIII antibodies in hemophilic mice are IgG1 (equivalent to IgG4 in humans) and are induced by Th2 cells.5,31,32 Also, Th2 driven responses have been found to correlate with higher total antibody and inhibitory titers in hemophilic patients. Cytokine profiling has revealed that IL-10, secreted by Th2 cells, may play an important role in the production of antibodies against exogenously administered rFVIII.35

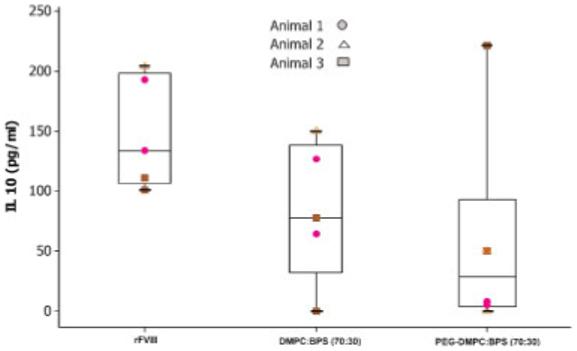

To determine whether reduced IL-10 secretion was responsible for reducing the antibody response against PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII, cytokine analysis of antigen-stimulated T-cells was carried out following immunization of animals with free- or PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII. As shown in Figure 3, the mean levels of IL-10 secreted by T-cells of animals given rFVIII associated with PEGylated liposomes was lower than for those animals given rFVIII alone. IL-10 level secreted by T-cells of animals receiving non-PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII is also shown. The data suggested that the mean IL-10 level was lower for the PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII treatment, though the differences were not statistically significant (p>0.05). Furthermore, it was notable that while all three animals receiving free rFVIII or non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII responded by secreting IL-10 above 50 pg/mL, only one of the three animals given PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII responded with cytokine secretion higher than 50 pg/mL. Negligible levels of IFN-γ were detected in the culture medium for all the treatment groups. Overall, the data suggest that the reduction in immunogenicity of rFVIII administered in the presence of PEGylated PS-containing liposomes may be mediated, to some extent, by reduced IL-10 production. Furthermore, the data indicate that the PEGylated liposomes do not appear to reduce the immunogenicity of rFVIII by altering the balance between the Th1/Th2 responses as reduction in IL-10 levels was not concomitant with increased production of IFN-γ.

Figure 3.

IL-10 secretion by antigen-challenged CD4+ T-cells from three animals administered two subcutaneous doses of 2 μg free rFVIII or PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII. CD4+ enriched T-cells were challenged with rFVIII (1000 ng/well). For comparison purposes, data obtained following administration of rFVIII in the presence of non-PEGylated DMPC: BPS liposome is also displayed. The data set was generated using duplicate samples per animal. Inter-animal variability was found to be not significant (p>0.05) for all the treatment groups. Hence, all the data points in each treatment group were combined for further statistical analysis. Data was analyzed using one-way ANOVA (p>0.05).

Qualitative analysis of the immune response studies suggest that (with respect to both the total antibody and inhibitory titers) incorporation of PEG in liposomal-rFVIII preparations appeared to further improve the potential of PS liposomes in reducing the antibody response against rFVIII. We speculate that there are mechanistic differences in the ability of PEGylated liposomes in reducing the immunogenicity of rFVIII relative to non-PEGylated liposomes. In addition to immunomodulation by PS, we anticipate that the PEG coating on the surface of the liposomes might impede antigen uptake by antigen presenting cells (APC) due to steric hindrance. In such a scenario, processing and subsequent downstream events such as presentation of immunodominant epitopes to the cells of the immune system would be inefficient, which in turn could interfere with the ability of the immune system to mount a strong antibody response against rFVIII. It has been shown previously that PS containing liposomes lowered the antibody response and this reduction was highest compared to other negatively charged phospholipid containing liposomes. We speculate that the reduction in the antibody formation with PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII could be due to several reasons which include reduced uptake by Antigen presenting cells, immunomodulating effect of PS and also possibly due to the particulate nature of the liposomes. Additional studies however, are required to gain insight on the antigen uptake and subsequent processing by the immune system.

Besides reduced immunogenicity of rFVIII, association of rFVIII with liposomes may also extend the circulation time of rFVIII in vivo. An increase in t1/2 would be beneficial by reducing the frequency of administration of the protein required to control bleeding episodes and improving the quality of a hemophilic patient’s life. Furthermore, the immune response against rFVIII could also be potentially minimized by prolonging the circulation time of the protein as frequent dosing or chronic administration of a protein therapeutic is likely to be associated with antibody formation.36,37

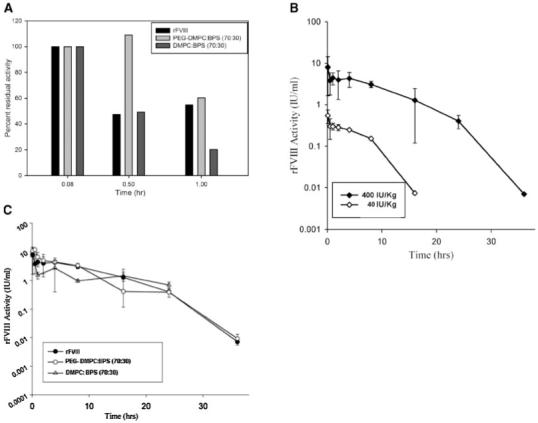

Pharmacokinetic (PK) studies were carried out following i.v. administration of rFVIII or non-PEGylated PS containing liposomal-rFVIII in hemophilic mice to determine the impact of liposomes on the disposition of rFVIII. The PK profiles obtained for the two different doses appeared to be complex and displayed region of convexity. The profiles clearly resemble classical patterns of Michaelis-Menten pharmacokinetics. Further, the total clearance of rFVIII reduces with increasing dose suggesting a nonlinear PK with saturable elimination of human recombinant protein in this animal model, consistent with possible saturation of LRP mediated endocytosis38,39 (Fig. 4 (B)). However, several factors could contribute to the observed nonlinearity and further detailed PK analysis is certainly necessary. Nevertheless, as the dose (10 IU/animal or 400 IU/Kg) used in the PK study may fall in the nonlinear range (Fig. 4(B)), an attempt was made to compare only systemic exposure or AUAC0-t, and apparent t1/2.

Figure 4.

(A) Bar graph of Percent residual rFVIII activity during initial time normalized to the initial observed activity following iv administration of rFVIII, PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII and Liposomal-rFVIII. (B) Pharmacokinetic profiles of rFVIII at dose levels of 40 IU/Kg and 400 IU/Kg suggesting nonlinear saturable elimination of the protein. Error bars represent SD. (C) Plasma rFVIII activity versus time profiles following administration of rFVIII, liposomal-rFVIII and PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII in hemophilic mice.

Analysis revealed a significant reduction in systemic exposure of non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII (Tab. 1A). This was consistent with rapid clearance of PS containing liposomes from the circulation due to avid uptake by the RES.21 With non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII, the apparent t1/2 could not be estimated as the terminal phase of the activity versus time data could not be ascertained adequately due to lack of detectable activity beyond 24 h. The AUAC0-24 in animals given non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII was significantly lower (∼36 IU/mL×h, p<0.05, Fig. 4(C) and Tab. 1A) relative to the AUAC0-24h for animals receiving rFVIII (∼57 IU/mL×h).

Table 1.

Summary of Parameters Obtained Following Noncompartmental Analysis

| Treatment | AUAC0-24 (IU/mL×h) |

|---|---|

| (A) | |

| rFVIII | ∼57 |

| Non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII | ∼36* |

| PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII | ∼59 |

| Treatment | AUAC0-36 (IU/mL×h) | Apparent t1/2 (h) |

|---|---|---|

| (B) | ||

| rFVIII | ∼59 | 2.6 |

| PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII | ∼61 | 3.5 |

Exposure (AUAC) between treatments were compared by the Bailer-Satterthwaithe method to detect significant differences (p<0.05).

PK studies in animals receiving PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII showed that the AUAC0-24h increased significantly (relative to AUAC0-24 in animals given non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII) to ∼59 IU/mL×h (p<0.05, Fig. 4(C) and Tab. 1A). Inclusion of PEG has been shown to enhance the stability of liposomes in vivo by possibly increasing the hydrophilicity of the liposome surface and minimizing nonspecific interaction with RES.40 The AUAC0-24h between rFVIII and PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII treatments however, was comparable (p>0.05, Fig. 4(C) and Tab. 1A). To represent the effect of PEGylation during the early stages after injection, rFVIII activity at the initial time-point (0.08 h) for all the treatment groups was normalized to 100% (Fig. 4A). Even though, degradation of the protein will happen from time 0 h to time 0.08 h, this was not considered while normalizing the activities. The increased activity in case of PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII at time 0.5 and 1 h indicated the protective role of PEG for liposomal-rFVIII activity in the initial 1 h following injection. Non-PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII activity was reduced by ∼80% during the same time period.

PK studies also revealed that the activity of the protein could be monitored up to 36 h following administration of rFVIII and PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII and the terminal phase of the protein activity versus time data could be captured adequately for the two treatments. NCA of the data indicated that the apparent t1/2 of rFVIII was 2.6 h. In the presence of PEGylated liposomes, the apparent t1/2 appeared to increase slightly to 3.5 h, a 40% increase in the half-life of the protein. However, Bailer-Satterthwaite analysis30 suggested that the systemic exposure AUAC0-36h between the two treatments was comparable (Tab. 1B) and thus it was not possible to conclusively establish that the increase in apparent t1/2 was significant. It is appropriate to mention here that the FVIII activity for initial time points was higher for animals given PEGylated liposomes compared to animals given rFVIII (Fig. 4(A)), clearly suggesting that PEGy-lation delays the elimination of FVIII. The exposure and t1/2 could be further significantly improved by increasing the PEG content and/or by inclusion of nonexchangeable lipid lipids such as 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethyleneglycol)-2000] (DSPE-PEG2000)41,42 in the prototype PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII preparations. The high mol% of PS in the liposome composition probably interferes with the ability of PEG to provide adequate stealth properties. Presence of PE has been shown to increase the affinity of PS containing liposomal membranes to FVIII thereby negating the requirement of high percentage of PS43 in these preparations and this could lead to substituting PE at the expense of PS. We believe that the PK studies coupled with a reliable pharmacodynamic response/end point will further aid in evaluating the efficacy of PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII. Nevertheless, the observation that the immunogenicity of PEGylated liposomal-rFVIII is much lower than rFVIII represents a significant progress towards the development of formulations that are less immunogenic and has potential to improve efficacy of replacement therapy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NHLBI, National Institute of Health grant (#R01 HL-70227) to SVB. We are grateful to Dr. Kazazian and Dr. Sarkar of University of Pennsylvania, PA for providing the FVIII knockout mice. We thank Nancy Pyszczynski (Dr. Jusko’s laboratory) for providing technical help with the T-cell proliferation assay. We thank Dr. Donald Mager, Anasuya Hazra and Amit Garg for valuable discussions on the pharmacokinetic studies.

Abbreviations used

- ACD

acid citrate dextrose

- AUAC0-t

area under the activity curve from time 0-to-t/systemic exposure

- APTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- BPS

brain phosphatidylserine

- BSA

bovine serum albumin

- t1/2

circulation half-life

- DMPC

dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine

- DMPE-PEG2000

1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethyleneglycol)-2000]

- DSPE-PEG2000

1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy (polyethyleneglycol)-2000]

- ELISA

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FVIIIa

activated FVIII

- FIXa

factor IXa

- Ig

immunoglobulin

- NCA

noncompartmental analysis

- PB

phosphate buffer

- PBA

phosphate buffer containing albumin

- PBT

phosphate buffer containing tween

- PC

phosphatidylcholine

- PE

phosphatidylethanolamine

- PS

phosphatidylserine

- rFVIIa

recombinant factor VIIa

- rFVIII

recombinant human factor VIII

- RES

reticuloendothelial system

- TB

Tris buffer

REFERENCES

- 1.Tuddenham EGD, Schwaab R, Seehafer J, Millar DS, Gitschier J, Higuchi M, Bidichandani S, Connor JM, Hoyer LW, Yoshioka A, Peake IR, Olek K, Kazazian HH, Lavergne JM, Giannelli F, Antonarakis SE, Coopar DN. Haemophilia A: Database of nucleotide substitutions, deletions, insertions and rearrangements of the factor VIII gene, second edition. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4851–4868. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larner AJ. The molecular pathology of haemophilia. Q J Med. 1987;63:473–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenting PJ, van Mourik JA, Mertens K. The life cycle of coagulation factor VIII in view of its structure and function. Blood. 1998;92:3983–3996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klinge J, Ananyeva NM, Hauser CA, Saenko EL. Hemophilia A—From basic science to clinical practice. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2002;28:309–322. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-32667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fijnvandraat K, Bril WS, Voorberg J. Immunobiology of inhibitor development in hemophilia A. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2003;29:61–68. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-37940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lollar P. Molecular characterization of the immune response to factor VIII. Vox Sang. 2002;83:403–408. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2002.tb05342.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ananyeva NM, Lacroix-Desmazes S, Hauser CA, Shima M, Ovanesov MV, Khrenov AV, Saenko EL. Inhibitors in hemophilia A: Mechanisms of inhibition, management and perspectives. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2004;15:109–124. doi: 10.1097/00001721-200403000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho AY, Height SE, Smith MP. Immune tolerance therapy for haemophilia. Drugs. 2000;60:547–554. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Foster PA, Zimmerman TS. Factor VIII structure and function. Blood Rev. 1989;3:180–191. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(89)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fay PJ. Factor VIII structure and function. Thromb Haemost. 1993;70:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scandella D, Mattingly M, de Graaf S, Fulcher CA. Localization of epitopes for human factor VIII inhibitor antibodies by immunoblotting and antibody neutralization. Blood. 1989;74:1618–1626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lollar P. Analysis of factor VIII inhibitors using hybrid human/porcine factor VIII. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:647–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Healey JF, Lubin IM, Nakai H, Saenko EL, Hoyer LW, Scandella D, Lollar P. Residues 484-508 contain a major determinant of the inhibitory epitope in the A2 domain of human factor VIII. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14505–14509. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.24.14505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lubin IM, Healey JF, Barrow RT, Scandella D, Lollar P. Analysis of the human factor VIII A2 inhibitor epitope by alanine scanning mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30191–30195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fay PJ, Scandella D. Human inhibitor antibodies specific for the factor VIII A2 domain disrupt the interaction between the subunit and factor IXa. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:29826–29830. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.42.29826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong D, Saenko EL, Shima M, Felch M, Scandella D. Some human inhibitor antibodies interfere with factor VIII binding to factor IX. Blood. 1998;92:136–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Healey JF, Barrow RT, Tamim HM, Lubin IM, Shima M, Scandella D, Lollar P. Residues Glu2181-Val2243 contain a major determinant of the inhibitory epitope in the C2 domain of human factor VIII. Blood. 1998;92:3701–3709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scandella D, Gilbert GE, Shima M, Nakai H, Eagleson C, Felch M, Prescott R, Rajalakshmi KJ, Hoyer LW, Saenko E. Some factor VIII inhibitor antibodies recognize a common epitope corresponding to C2 domain amino acids 2248 through 2312, which overlap a phospholipid-binding site. Blood. 1995;86:1811–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reding MT, Okita DK, Diethelm-Okita BM, Anderson TA, Conti-Fine BM. Human CD4+ T-cell epitope repertoire on the C2 domain of coagulation factor VIII. J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1777–1784. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pratt KP, Qian J, Ellaban E, Okita DK, Diethelm-Okita BM, Conti-Fine B, Scott DW. Immunodominant T-cell epitopes in the factor VIII C2 domain are located within an inhibitory antibody binding site. Thromb Haemost. 2004;92:522–528. doi: 10.1160/TH03-12-0755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemann C, Yau-Young A. Liposomes containing synthetic lipid derivatives of poly(ethylene glycol) show prolonged circulation half-lives in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1066:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baru M, Leo CG, Barenholz Y, Dayan I, Ostropolets S, Slepoy I, Gvirtzer N, Fukson V, Spira J. Factor VIII efficient and specific non-covalent binding to PEGylated liposomes enables prolongation of its circulation time and haemostatic efficacy. Thromb Haemost. 2005;93:1061–1068. doi: 10.1160/TH04-08-0485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sou K, Endo T, Takeoka S, Tsuchida E. Poly (ethylene glycol)-modification of the phospholipid vesicles by using the spontaneous incorporation of poly(ethylene glycol)-lipid into the vesicles. Bioconjug Chem. 2000;11:372–379. doi: 10.1021/bc990135y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bartlett GR. Phosphorus assay in column chromatography. J Biol Chem. 1959;234:466–468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purohit VS, Ramani K, Kashi RS, Durrani MJ, Kreiger TJ, Balasubramanian SV. Topology of factor VIII bound to phosphatidylserine-containing model membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1617:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heath TD, Macher BA, Papahadjopoulos D. Covalent attachment of immunoglobulins to liposomes via glycosphingolipids. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1981;640:66–81. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(81)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Over J. Methodology of the one-stage assay of Factor VIII (VIII:C) Scand J Haematol Suppl. 1984;41:13–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1984.tb02764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stoilova-McPhie S, Villoutreix BO, Mertens K, Kemball-Cook G, Holzenburg A. 3-Dimensional structure of membrane-bound coagulation factor VIII: Modeling of the factor VIII heterodimer within a 3-dimensional density map derived by electron crystallography. Blood. 2002;99:1215–1223. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purohit VS, Ramani K, Sarkar R, Kazazian HH, Balasubramanian SV. Lower inhibitor development in Hemophilia A mice following administration of recombinant Factor VIII-O- Phospho-L-serine complex. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:17593–17600. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500163200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nedelman JR, Gibiansky E, Lau DT. Applying Bailer’s method for AUC confidence intervals to sparse sampling. Pharm Res. 1995;12:124–128. doi: 10.1023/a:1016255124336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pratt KP, Shen BW, Takeshima K, Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Stoddard BL. Structure of the C2 domain of human factor VIII at 1.5 A resolution. Nature. 1999;402:439–442. doi: 10.1038/46601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reipert BM, Ahmad RU, Turecek PL, Schwarz HP. Characterization of antibodies induced by human factor VIII in a murine knockout model of hemophilia A. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:826–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu H, Reding M, Qian J, Okita DK, Parker E, Lollar P, Hoyer LW, Conti-Fine BM. Mechanism of the immune response to human factor VIII in murine hemophilia A. Thromb Haemost. 2001;85:125–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.White GC, II, Kempton CL, Grimsley A, Nielsen B, Roberts HR. Cellular immune responses in hemophilia: Why do inhibitors develop in some, but not all hemophiliacs? J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1676–1681. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reding MT, Lei S, Lei H, Green D, Gill J, Conti-Fine BM. Distribution of Th1- and Th2-induced anti-factor VIII IgG subclasses in congenital and acquired hemophilia patients. Thromb Haemost. 2002;88:568–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schellekens H. Immunogenicity of therapeutic proteins: Clinical implications and future prospects. Clin Ther. 2002;24:1720–1740. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(02)80075-3. discussion 1719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schellekens H. Bioequivalence and the immunogenicity of biopharmaceuticals. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:457–462. doi: 10.1038/nrd818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lenting PJ, Neels JG, van den Berg BM, Clijsters PP, Meijerman DW, Pannekoek H, van Mourik JA, Mertens K, van Zonneveld AJ. The light chain of factor VIII comprises a binding site for low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23734–23739. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.34.23734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saenko EL, Yakhyaev AV, Mikhailenko I, Strickland DK, Sarafanov AG. Role of the low density lipoprotein-related protein receptor in mediation of factor VIII catabolism. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37685–37692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.53.37685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klibanov AL, Maruyama K, Torchilin VP, Huang L. Amphipathic polyethyleneglycols effectively prolong the circulation time of liposomes. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:235–237. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chiu GN, Bally MB, Mayer LD. Selective protein interactions with phosphatidylserine containing liposomes alter the steric stabilization properties of poly(ethylene glycol) Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1510:56–69. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(00)00335-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li WM, Mayer LD, Bally MB. Prevention of antibody-mediated elimination of ligand-targeted liposomes by using poly(ethylene glycol)-modified lipids. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;300:976–983. doi: 10.1124/jpet.300.3.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert GE, Arena AA. Phosphatidylethanolamine induces high affinity binding sites for factor VIII on membranes containing phosphatidyl-L-serine. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18500–18505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]