Abstract

We report an 18-year-old woman with anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) encephalitis, who developed psychiatric symptoms, progressive unresponsiveness, dyskinesias, hypoventilation, hypersalivation and seizures. Early removal of an ovarian teratoma followed by plasma exchange and corticosteroids resulted in a prompt neurological response and eventual full recovery. Serial analysis of antibodies to NR1/NR2B heteromers of the NMDAR showed an early decrease of serum titres, although the cerebrospinal fluid titres correlated better with clinical outcome. The patients’ antibodies reacted with areas of the tumour that contained NMDAR-expressing tissue. Search for and removal of a teratoma should be promptly considered after the diagnosis of anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Paraneoplastic encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma has recently been related to the development of antibodies to the NR1/NR2B heteromers of the N-methyl-D-asparate receptor (NMDAR).1 The disorder, called anti-NMDAR encephalitis, results in a characteristic syndrome that presents with prominent psychiatric symptoms or, less frequently, memory deficits, followed by a rapid decline of the level of consciousness, central hypoventilation, seizures, involuntary movements and dysautonomia. Despite the severity of symptoms and prolonged clinical course, most patients recover if the disorder is recognised and treated.1 Immunotherapy, including corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin or plasma exchange, is often effective, and it has been suggested that prompt resection of the teratoma expedites recovery.1 In most previously reported cases of anti-NMDAR encephalitis, the ovarian teratoma was removed a few months (median: 9 weeks) after neurological symptom presentation, sometimes when symptoms had already partially responded to immunotherapy.1–5 We report the clinical outcome and follow-up of antibody titres in a Japanese woman whose ovarian tumour was removed early (20 days) after neurological symptom onset.

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old woman without a past medical history of interest developed headache and fever for a few days. She also complained of the sensation that the left half of her body was twisting. She was admitted to our hospital with progressive psychosis, and emotional and behavioural changes. Her temperature was 37.1°C; no meningeal signs were noted. Sustained involuntary movements were observed around her mouth, resembling orofacial dyskinesias. She was disorientated to place and person, and had schizophrenia-like symptoms, such as disorganized thinking and loss of self-awareness (fig 1). She constantly repeated “I’m in the world of Harry Potter!” and “I have no idea who I am!” and knocked her head against the wall. Intravenous administration of acyclovir (1500 mg/day) and dexamethasone (6 mg/day) resulted in no improvement and she became mute and unresponsive to verbal commands. The orofacial dyskinesias gradually worsened, showing sustained bizarre movements such as widely opening and tightly closing of the eyes and mouth, sticking out the tongue and grimacing (see video online).

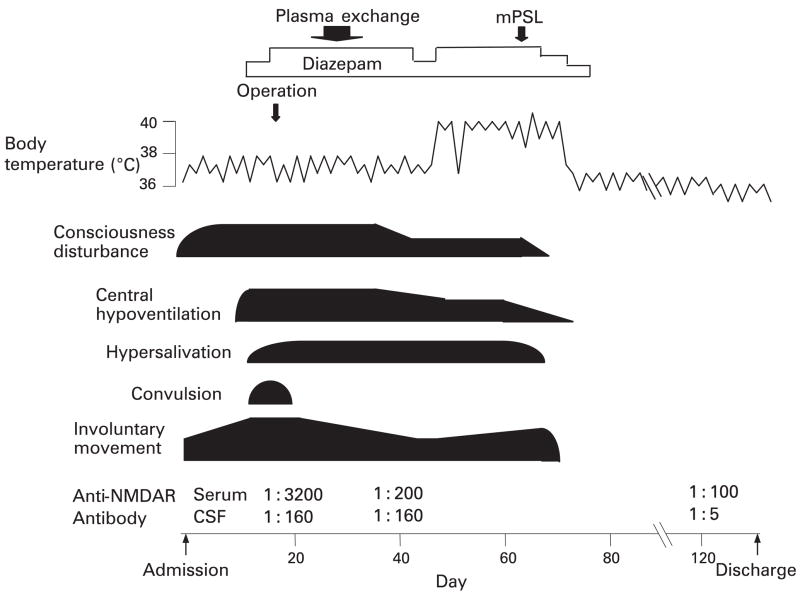

Figure 1.

Clinical course and serial analysis of anti-NMDAR antibodies. Serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were collected on days 18 (pre-treatment), 39 (post-treatment) and 120 (late post-treatment). The diluted values are indicated. mPSL = methylprednisolone; Operation = salpingo-oophorectomy.

Serological testing for antinuclear and VGKC antibodies, tumour markers, and paraneoplastic antibodies including Hu, Yo, CV2/CRMP5, amphiphysin and Ma2 were all negative. Lumbar puncture showed lymphocytic pleocytosis (87/mm3) with normal protein and glucose concentrations, and positive CSF oligoclonal bands. PCR was negative for HSV-1, HSV-2, CMV, HHV-6, VZV and EBV. Several brain MRIs showed only mild meningeal enhancement. SPECT studies showed slight hyperperfusion in the right temporal region. EEG demonstrated disorganised activity without epileptic discharges. On day 9 of hospitalisation, a pelvic CT revealed a 58 mm right ovarian mass. The patients’ symptoms gradually worsened, requiring mechanical ventilation on day 10 and a tracheostomy on day 13. She also suffered from tonic convulsions and dysautonomia, including diaphoresis, hypersalivation and hyperthermia.

On day 19, she underwent unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, which revealed a grade 2 immature teratoma. Antiepileptic drugs, including phenytoin, phenobarbital and sodium valproate, controlled the convulsions, but not the involuntary movements that responded to diazepam (30 mg/day), which was administered via a nasogastric tube. Subsequently, four consecutive plasma exchanges were performed from day 26 to day 34. On day 42, she started to inconsistently follow simple commands, but the involuntary movements and central hypoventilation persisted. Because of this and the development of hyperthermia (⩾ 40°C), methylprednisolone (1000 mg/day for 3 days) was started on day 61. Four days later, the level of consciousness and involuntary movements improved, and she was weaned from the mechanical ventilator on day 70. During the course of the disease, she developed thrombosis of the left femoral vein that required anticoagulation. Eventually, all neurological symptoms resolved. She achieved 29/30 on her Minimal Mental State Examination on day 120, and was discharged home with minimal disability for calculations on day 129.

DETERMINATION OF ANTI-NMDAR ANTIBODIES

The presence of antibodies to NR1/NR2B heteromers of the NMDAR was determined as previously reported.1 Samples of serum and CSF were obtained on days 18 (pre-treatment), 39 (post-treatment) and 120 (late post-treatment). All six samples were positive for anti-NMDAR antibodies and the titres were determined using serial dilutions of serum and CSF. These studies showed a substantial decrease of antibodies after treatment; this decrease was noted earlier in the serum than in the CSF, as indicated in figure 1.

IMMUNOHISTOCHEMISTRY

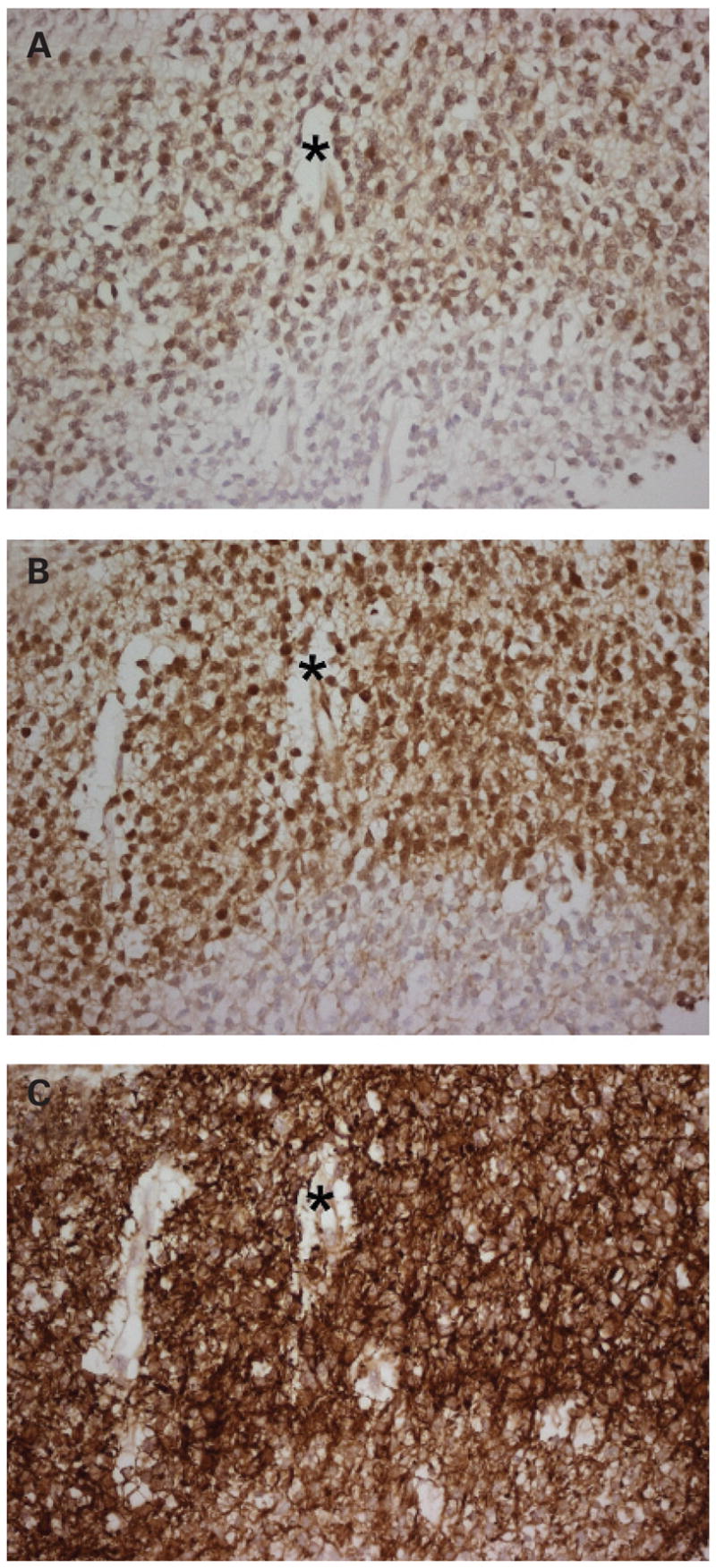

Immunohistochemical studies of consecutive paraffin-embedded sections (3 μm-thick) of the tumour using the patients’ biotinylated IgG (0.2 mg/ml), polyclonal rabbit anti-NR1 antibody (1:50; Chemicon International, Temecula, CA) and chicken anti-MAP2 antibody (1:10,000; Covance, Princeton, NJ) were performed as previously reported.1 The reactivity was demonstrated using the appropriate secondary antibodies and the avidin-biotin-peroxidase method. As shown in figure 2, the patients’ antibodies reacted with areas of the tumour that contained NMDAR-expressing nervous tissue, indicated by the reactivity of the anti-NR1 antibody (an obligatory subunit of the NMDAR) and the anti-MAP2 antibody (a marker of neurons and dendritic processes).

Figure 2.

Reactivity of patients’ antibodies with the tumour.

Consecutive sections of the patients’ teratoma incubated with patient’s antibodies (A), anti-NR1 antibody (B) and MAP2 antibody (C). Note that the patients’ antibodies immunolabel the areas of the nervous system expressing NR1 (an obligatory subunit of the NMDAR). Stars are placed in the same region of the three consecutive sections. All sections were mildly counterstained with hematoxylin; original magnification ×400.

DISCUSSION

Early clinical features of anti-NMDAR encephalitis usually include a prodromic episode of fever, headache or malaise, followed a few days later by mood and behavioural changes, and severe psychiatric symptoms suggestive of schizophrenia or catatonia.1 2 The development of these manifestations in a young woman should raise the suspicion of the disorder and prompt the search of an ovarian teratoma.6 In our case, the ovarian teratoma was detected 10 days after the onset of the psychiatric symptoms, and was removed 10 days later. We believe that early tumour resection is the most important factor enabling prompt and full recovery from anti-NMDAR encephalitis. Early treatment can shorten the duration of ventilatory support and dyskinesias compared with that of patients without tumour resection.2 In our patient, it is likely that immunotherapy contributed to her recovery. Although the involuntary movements and facial dyskinesias have been previously reported as refractory to many treatments,2 a high dose of diazepam (30 mg/day) via stomach tube appeared to be effective in our patient.

Serial anti-NMDAR antibody testing showed a decrease of titres that occurred earlier in serum than in CSF. This was probably due to the faster effects of plasma exchange on removing circulating serum antibodies. The slower decrease of CSF antibody titres probably represents the effects of all treatments (tumour removal and immunotherapy), and these titres correlated better with symptom improvement than with serum titres.

Immunohistological studies revealed that patients’ antibodies reacted with areas of the tumour that contained nervous tissue and had NMDAR expression. This supports the concept that the ectopic expression of nervous tissue contributes to the triggering of the immune response. Interestingly, this immune disorder seems to occur more frequently in Japanese individuals than in Caucasians.2–5 A number of patients with similar symptoms have previously been reported as suffering from “acute juvenile female non-herpetic encephalitis”, a descriptive term used for a disorder of unclear aetiology.7 We postulate that many of these patients had anti-NMDAR encephalitis.2 Taken together, these observations suggest that the Japanese may have a genetic predisposition to the development of anti-NMDAR encephalitis. We are currently studying the association of this disease with the immunogenetic background of patients with anti-NMDAR encephalitis.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported in part by grants RO1CA89054 and RO1CA1071892 (to JD).

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Dalmau J, Tüzün E, Wu HY, et al. Paraneoplastic anti-N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:25–36. doi: 10.1002/ana.21050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iizuka T, Sakai F, Ide T, et al. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis in Japan: Long-term outcome without tumor removal. Neurology. 2007 Sep 26; doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000278388.90370.c3. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koide R, Shimizu T, Koike K, et al. EFA6A-like antibodies in paraneoplastic encephalitis associated with immature ovarian teratoma: a case report. J Neurooncol. 2007;81:71–4. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9200-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimazaki H, Ando Y, Nakano I, et al. Reversible limbic encephalitis with antibodies against the membranes of neurons of the hippocampus. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:324–5. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.104513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tonomura Y, Kataoka H, Hara Y, et al. Clinical analysis of paraneoplastic encephalitis associated with ovarian teratoma. J Neurooncol. 2007;84:287–92. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9372-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sansing LH, Tüzün E, Ko MW, et al. A patient with encephalitis associated with NMDA receptor antibodies. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3:291–6. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamei S. Acute juvenile female non-herpetic encephalitis: AJFNHE (in Japanese) Adv Neurol Sciences. 2004;48:827–36. doi: 10.5692/clinicalneurol.48.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]