Abstract

The biological functions of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) extend beyond extracellular matrix degradation. Non-proteolytic activities of MMPs are just beginning to be understood. Herein, we evaluated the role of proMMPs in cell migration. Employing a Transwell chamber migration assay, we demonstrated that transfection of COS-1 cells with various proMMP cDNAs resulted in enhancement of cell migration. Latent MMP-2 and MMP-9 enhanced cell migration to a greater extent than latent MMP-1, -3, -11 and -28. To examine if proteolytic activity is required for MMP-enhanced cell migration, three experimental approaches, including fluorogenic substrate degradation assay, transfection of cells with catalytically inactive mutant MMP cDNAs, and addition of hydroxamic acid-derived MMP inhibitors, were employed. We demonstrated that the proteolytic activities of MMPs are not required for MMP-induced cell migration. To explore the mechanism underlying MMP-enhanced cell migration, structure-function relationship of MMP-9 on cell migration was evaluated. By using a domain swapping approach, we demonstrated that the hemopexin domain of proMMP-9 plays an important role in cell migration when examined by a transwell chamber assay and by a phagokinetic migration assay. TIMP-1, which interacts with the hemopexin domain of proMMP-9, inhibited cell migration, whereas TIMP-2 had no effect. Employing small molecular inhibitors, MAPK and PI3K pathways were found to be involved in MMP-9-mediated cell migration. In conclusion, we demonstrated that MMPs utilize a non-proteolytic mechanism to enhance epithelial cell migration. We propose that hemopexin homodimer formation is required for the full cell migratory function of proMMP-9.

Keywords: Matrix Metalloproteinase, cell migration, MMP-9, hemopexin domain

Introduction

MMPs are zinc-dependent endopeptidases, which are widely recognized to play an important role in the homeostatic regulation of the extracellular environment (Nagase and Woessner, 1999). Following the seminal isolation of collagenase from the tadpole tail, MMPs were demonstrated to degrade and remodel numerous extracellular matrix (ECM) components, including collagens, laminin, fibronectin, elastin, hyaluronan, and proteoglycans (Gross and Lapiere, 1962; Nagase and Woessner, 1999; Ramos-DeSimone et al., 1999; Abecassis et al., 2003). Systems biological approaches have more recently resulted in expansion of potential biological substrates cleaved by MMPs (e.g. growth factor-precursors, binding proteins, cell adhesion molecules and chemokines). The role of MMPs in biology has been expanded to include the regulation of cellular functions, including apoptosis, proliferation, differentiation, angiogenesis, migration, invasion, metastasis, and host defense (Abecassis et al., 2003; Bjorklund and Koivunen, 2005; Lee et al., 2000; Di Girolamo et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2007). MMPs have been implicated in numerous pathological processes involving the heart, lung, liver, kidney, gastrointestinal, skin, retina, hematopoietic, and nervous systems. The relative importance placed on MMPs in human diseases is highlighted by the billion dollar investment by the pharmaceutical industry in testing MMP inhibitors in patients with arthritis, heart failure, and advanced cancer (Bjorklund and Koivunen, 2005; Massova et al., 1998; Zucker et al., 2000). However, based on the failure to date of broad spectrum MMP inhibitors in treating human diseases, the scientific community is in the process of reevaluating the biological function of MMPs (Lee et al., 2004; Zucker et al., 2000).

All MMPs contain a signal peptide, a propeptide, and a Zn2+ -containing catalytic domain of 160-170 amino acids in length. With the exception of MMP-7, -23 and -26, all MMPs also contain a proline-rich hinge region and a C-terminal hemopexin-like domain (PEX). Following cleavage distal to the highly conserved sequence (PRCGXPD) in the propeptide, latent MMPs (zymogen) become activated (Massova et al., 1998). The PEX domain of MMPs forms a propeller with four blades linked by a disulfide bonds between blade I and blade IV (Cha, 2002). Each individual blade is composed of one α-helix and four anti-parallel β-sheets. The PEX domain of MMPs regulates substrate binding (Sternlicht and Werb, 2001). In contrast to other MMPs, the hemopexin domain of proMMP-2 and proMMP-9 bind TIMP-2 and TIMP-1, respectively. MMP-2 and MMP-9 have a fibronectin domain as part as the catalytic domain which allow them to interact with various collagens and gelatins (Steffensen et al., 1995; Allan et al., 1995). MMP-9 is the only secreted MMP that forms a homodimer through its PEX domain. It also has the longest hinge region consisting of more than 50 amino acids (compared to ∼ 10 amino acids in other MMPs) and is the only MMP containing a cysteine residue in this domain (Steen et al., 2006).

Correlations have been made between the capacity of MMP-9 to degrade ECM collagens and laminin and its ability to regulate cell migration, increase angiogenesis, and affect tumor growth (Bjorklund and Koivunen, 2005; Sternlicht and Werb, 2001; Burg-Roderfeld et al., 2007; Egeblad and Werb, 2002; Sanceau et al., 2003; Opdenakker and Van Damme, 2002). Although cleavage of numerous MMP-9 substrates have been characterized in vitro (e.g. aggrecan, collagens IV, V, XI, XIV, decorin, elastin, fibrillin, gelatin I, laminin, link protein, myelin basic, osteonectin, vitronectin, α2-M, α1-PI, casein, C1q, fibrin, fibrinogen, IL1β, proTGFβ, proTNFα, plasminogen and substance P), it has been difficult to define the biological functions of these observations (Sternlicht and Werb, 2001). Bannikov et al. reported that proMMP-9 displays catalytic activity following binding to substrates (Bannikov et al., 2002). Of interest, the PEX domain of proMMP-9 has been shown to have higher affinity for binding gelatin, collagen type I, collagen type IV, elastin and fibrinogen than the PEX domain of active MMP-9 (Burg-Roderfeld et al., 2007).

In this report, we have examined the mechanism of MMP-induced cell migration. Contrary to many reports which do not clearly distinguish between migration and invasion, we have examined cell locomotion in the absence of ECM. Here, we demonstrate that proMMP-induced cell migration does not depend on cleavage of ECM substrates as previously thought (Sternlicht and Werb, 2001). Based on interest in the function of the PEX domain of MMP-9, we have explored and identified novel functions of this domain in cell migration.

Material and Methods

Reagents

Oligo primers were purchased from Operon, AL. The pcDNA3.1-myc and pSG5 expression vectors were described previously (Cao et al., 1996). Recombinant proMMP-1, -2, -3, -9,-11/myc, -28/myc and TIMP-1 were produced by COS-1 cell transfected with corresponding proMMP and TIMP-1 cDNAs as previously described (Cao et al., 1996). Anti-human MMP-2 (hemopexin domain) monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Oncogene Research Products (Cambridge, MA). Anti-Myc antibodies were purchased from Roche (Indianapolis, IN). MMP-9 antibodies were described previously (Cao et al., 1996; Zucker et al., 1993). MMP-9 was purified from transfected cell condition media by gelatin-Sepharose chromatography. PD89059, LY294002, Y27632, H89, wortmannin, SP600125 were purchased from Sigma chemicals (St. Louis, MO).

Cell Culture and Transfection

COS-1 cell lines were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA) and were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (Invitrogen). Plasmids were transfected into cells using Transfectin™ reagent (Bio-Rad, CA). COS-1 and MCF-7 cells were transfected with corresponding cDNAs and incubated for 48 h at 37 °C in DMEM with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) medium (Invitrogen); after 24 h, the medium was changed.

Construction of Plasmids

MMP-9ΔPEX lacking the C-terminal hemopexin domain of MMP-9 was generated by introducing a stop codon after Asp513 based on a PCR strategy using the primer sets: forward primer, #1315: 5′-3′: CGGAATTCCGCCACCA TGAGCCTCTGGCAGCCCCT and reverse primer, #1342 AAAAAGCTTTTAG TCCAC CGGACTCAAAGGCAC. The primers were designed with an EcoRI site at the 5′ and a HindIII site at the 3′ end. The PCR products were digested with EcoRI and HindIII enzymes (Roche, IN). The PCR fragments were then ligated into pcDNA3.1(-)/Myc-His C vector (Invitrogen, CA). Correct sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

MMP-9/MMP-1PEX denotes a substitution mutation produced by replacing the PEX domain of MMP-9 with that of MMP-1. It was incorporated using a modified two-step PCR technique previously described (Cao et al., 1998). In brief, MMP-9 signal peptide/propeptide/ catalytic/hinge domains (fragment A) (primer sets: forward primer #1315 and #1316, 5′-3′: TAGCTTACTGTCACACGCTTTGTCCACCGGACTCA AAGGCAC), MMP-1 PEX domain (fragment B) (primer sets: forward primer #1317, 5′-3′: AAAGCAT GTGACAGTAAGCTA, and reverse primer #1318, 5′-3′: CCCAAGCTTATTTT TCCTGCAGTTGAACCA) were first amplified by PCR separately using similar conditions as described above for MMP-9ΔPEX. Using resultant PCR products as templates (fragment A and B), the signal/propeptide/catalytic/hinge region of MMP-9 were then fused together with MMP-1 PEX domain by PCR using forward primer #1315 and reverse primer #1318. The PCR fragments were then ligated into pcDNA3.1(-)/Myc-His C vector (Invitrogen, CA). Correct sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

MMP-9ΔOG refers to MMP-9 without the O-glycosylated site. PCR was performed using synthetic oligonucleotide primers (Operon, AL) complementary to the MMP-9 gene without including its OG domain. The construct was done using site directed mutagenesis. A pair of primers was designed based on product instructions. The primer sequences were primer sets: forward primer #1357: 5′-3′: ATCCGGCACCTCTA TGGTGATGCCTGCAACGTGAAC and reverse primer #1358, 5′-3′: ACCATAGA GGTGCCGGAT. The restriction enzymes used was DpnI, the PCR fragments were then ligated into pcDNA3.1(-)/Myc-His vector (Invitrogen, CA). Correct sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

MMP-9E230→A refers to a mutation of the glutamic acid at position 230 for an alanine in MMP-9 wild type. PCR was performed using synthetic oligonucleotide primers (Operon, AL) complementary to the MMP-9 gene. The construct was done using site directed mutagenesis. A pair of primers was designed based on product instructions. The primer sequences were primer sets: forward primer #2523: 5′-3′:GACGATGACGCGTTGTGGTCC and reverse primer #2524, 5′-3′:GGACCACAACGCGTCATCGTC. The restriction enzymes used was DpnI, the PCR fragments were then ligated into pcDNA3.1(-)/Myc-His vector (Invitrogen, CA). Correct sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

Phagokinetic Cell Migration Assay

The basic procedure was described earlier (Albrect-Buehler, 1997). In brief, coverslips treated with L-lysine (50 μg/ml) were coated with 0.5% BSA followed by airdrying. The coverslips, placed in 12 well plates, were incubated with freshly made colloidal gold particles for 1 h followed by washing with PBS. Cells (1 × 104/well) were replated onto colloidal gold particle-coated coverslips and incubated at 37°C for 6h followed by fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Migratory cells were observed and photographed under light microscopy (Nikon). Images were processed and measured using NIH image software (ImageJ). The percent of phagocytosis was analyzed by imageJ which calculated the area cleared of gold particles.

Transwell Cell Migration Assay

Polycarbonate membranes of 13 mm diameter with 8 μm pore size (Neuro Probe, MD) were inserted into the Blind-Well Chemotactic chambers (Neuro Probe, MD). Prior to seeding into the transwell inserts, COS-1 cells were released from plates with trypsin-EDTA followed by the addition of DMEM with 10 % FCS media. The lower chemotactic chamber was filled with DMEM containing 10% FCS (200 μL). Cells were counted using a hemacytometer (Hausser Scientific, PA). The upper chamber was filled with 18,000 cells suspended in DMEM plus 10 % FCS to a final volume of 200 μL. Chambers were incubated for 6 h and 18 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified tissue culture incubator. The cells on the upper surface were then removed from the filter with a cotton swab and washed three times with PBS. The cells remaining on the lower surface were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS solution overnight in a 4 °C refrigerator. Cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet for 20 min and examined under a microscope. The number of cells in 10 areas of the filters was counted (20× objective) to obtain the number of migrating cells. For the inhibition experiments, cells were mixed with inhibitors 30 minutes prior to 6h and 18h migrations.

Gelatin Zymography

Zymography was performed in 10% polyacrylamide gels that had been cast in the presence of 0.1% gelatin as described previously (Zucker et al., 1995). After electrophoresis, SDS was removed by Triton X-100 followed by incubation in a Tris-based buffer for 24 h. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue, and gelatinolytic activity was detected as a clear band in the background of uniform staining.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblotting was performed using monoclonal antibodies to MMP-1, -2, -3, -9 and Myc. Transient transfected COS-1 cell-conditioned medium was precipitated with 10% trichloroacetic acid, and the precipitated proteins were dissolved in SDS sample buffer. Cells were lysed by 2 X SDS gel-loading buffer. The samples were resolved by 10% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and probed with antibodies. After extensive washing with TBS-T ((20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.6, 137 mM NaCl, 0.1% Tween), the membrane was probed with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG for corresponding MMP and Myc primary antibodies. Molecular weight was determined using prestained protein standards.

Cell Attachment Assay

Cells (5×104) suspended in DMEM containing 10% fetal calf serum were dispensed into 6-well culture plates and incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 °C for 1h and 3h. After the incubation period, cells were gently washed 3 times with PBS. Cells attached to the membrane were stained with 0.1% crystal violet and counted under the microscope.

Fluorogenic Assay of Enzyme Activity

MCA Fluorogenic peptide substrate (50 μM) was added to MMP-2 and MMP-9 conditioned media and incubation buffer (Knight et al., 1992). As a positive control, MMP-2 and MMP-9 conditioned media were activated with 1 mM APMA (4-aminophenyl mercuric acetate). Samples were incubated in the dark for 1 h at 25 °C before detection. Fluorescence was measured with excitation at 328 nm and emission at 393 nm, in a fluorescent plate reader (SpectraMAx M5, Molecular Devices, Union City, CA).

Statistical Analysis

Data is expressed as the mean ± standard error of triplicates. Each experiment was repeated as least 3 times. Student’s t-test and analysis of variants (ANOVA) were used to assess differences with p < 0.05 and p < 0.01 considered to be significant.

Results

Enhanced cell migration by over-expression of full-length MMPs in COS-1 cells

Substrate degradation and cell migration are key factors contributing to cancer invasion (Bjorklund and Koivunen, 2005). MMPs function in these pathological processes by digesting basement membrane/extracellular matrix (ECM) and enhancing cell migration (Sternlicht and Werb, 2001). Given the evidence that enhanced cell migration is often accompanied by secretion of activated MMPs, it has been hypothesized that the enzymatic activity of MMPs is required for the enhanced cell migration (Sternlicht and Werb, 2001). However, direct evidence for this hypothesis is limited.

To clarify the role of proteolytic activity in MMP-enhanced cell migration, wild-type MMP cDNAs encoding full-length secretory MMP-1, -2, -3, -9, -11 and -28 were expressed in COS-1 cells, a monkey kidney epithelial cell line which produces negligible quantities of MMPs (Cao et al., 2005). Following transient transfections, cell migration was assessed in a Transwell chamber migration assay employing 8 μm pore size non-coated polycarbonate membranes. In comparison to non-transfected or Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP)-cDNA transfected cells, COS-1 cells transfected with each individual MMP cDNA displayed significantly enhanced cell migration (Fig. 1A, B). Migration by MMP-2 and MMP-9 transfected cells was significantly enhanced as compared to MMP-1, -3, -11, and -28. The enhancement of cell migration was not due to the expression level of MMPs in COS-1 cells as assessed by Western blotting (ratios between specific MMPs and a house-keeping gene product, tubulin; Fig. 1C, D). Of note, the molecular weight of individual MMP bands revealed no cleavage products consistent with activated enzyme. Similar results were obtained using minimally invasive human MCF-7 cells transfected with MMP cDNAs (data not shown). These results indicate that expression of full-length MMPs leads to enhanced cell migration.

Figure 1.

Effect of MMPs expressed in COS-1 cells on random cell migration.

A, B) Expression of MMPs in COS-1 cells enhances cell migration. COS-1 cells transfected with corresponding cDNAs as indicated were examined by a Transwell chamber migration assay. Migrated cells were microscopically examined (A) and counted (B). *Significant difference; p < 0.05, as compared to COS-1 cells.

C, D) Comparable expression of MMPs in transfected COS-1 cells examined by Western blotting. COS-1 cells transfected with various cDNAs were lysed and immunoblot analysis was performed using the corresponding antibodies as indicated (C). Densitometric analyses of expression levels of MMPs and tubulin, respectively, in COS-1 cells were performed. Relative expression levels of MMPs in COS-1 cells were determined based on ratios between levels of specific MMPs and the corresponding respective levels of tubulin (D).

MMP proteolytic activity is not required for enhanced cell migration

To specifically address the issue of a requirement of MMP activation for cell migration, we first examined if activated MMPs are presented in the conditioned medium of transfected COS-1 cells. A highly sensitive fluorogenic peptide degradation assay was employed (Knight et al., 1992). MMP-2 and MMP-9 were selected as examples of MMPs which are extremely effective in enhancing cell migration. Conditioned medium of COS-1 cells transfected with MMP-2 and -9 was collected and proteolytic activity was compared to APMA-treated cell conditioned medium containing activated MMP-2 and MMP-9; conditioned medium from vector transfected cells was utilized as a negative control. In contrast to APMA-treated conditioned media from cells transfected with MMP-2 and MMP-9 cDNA, non-APMA-treated conditioned media displayed negligible activity (Fig. 2A). This data confirms the absence of measureable quantities of activated MMPs in cell conditioned media.

Figure 2.

ProMMPs enhance cell migration of COS-1 cells.

A) No enzymatic activity is detected in the conditioned medium of COS-1 cells transfected with MMP-2 and -9 cDNAs. Fluorogenic substrate peptide was incubated with APMA- or non-APMA-treated conditioned medium, as indicated, followed by measurement of the degradation products using a fluorescent plate reader.

B) No effect of TIMP-1 and -2 on MMP-2, -11, and -28-enhanced cell migration. COS-1 cells transfected with a combination of MMPs and TIMP, as indicated, were examined by a Transwell chamber migration assay. Migrated cells were stained and microscopically counted.

C) Addition of synthetic MMP inhibitor in MMP-transfected COS-1 cells does not interfere with MMP-9-enhanced cell migration. Synthetic MMP inhibitor CT1746 at different doses was incubated with cells transfected with MMP-9 cDNA, and Transwell migration assay was subsequently performed. Migrated cells were stained and microscopically counted.

D, Constitutively inactive MMP-9 and -28 enhance cell migration as well as wild type enzymes. COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type, mutant MMP-9, or -28 were examined by the Transwell migration assay. Migrated cells were stained and microscopically counted.

To further explore the role of proteolytic activity of MMPs in cell migration, MMP inhibitors (TIMP-1 and -2) at effective concentrations (Nagase and Woessner, 1999) were employed. MMP-2, -11 and -28 were transiently co-expressed in COS-1 cells along with either TIMP-1 or TIMP-2; cell migration was subsequently assessed. TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 displayed no effect on MMP-2, -11, and -28-mediated cell migration (Fig. 2B). When broad spectrum hydroxamic acid-derived inhibitors of MMPs CT1746 (Fig. 2C) and BB3103 (data not shown) were incubated with COS-1 cells in the Transwell chambers, no effect of these MMP inhibitors was observed on MMP-9-induced cell migration. In addition, we generated enzymatically inactive mutants of MMP-9 and MMP-28 by converting glutamine in the active center of each MMP to alanine using a site-direct mutagenesis approach (MMP-9 E230 and MMP-28E241). The enhanced COS-1 cell migration observed in the enzymatically inactive mutants of MMP-9 and -28 was comparable to wild types (Fig. 2D). These results indicate that cell synthesis of MMPs leads to enhanced cell migration without a requirement for enzyme activation.

Requirement of the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 in cell migration

Based on the prominent implication of MMP-9 in various disease processes and its’ profound effect on cell migration (Bjorklund and Koivunen, 2005), this MMP was selected for more detailed analysis. There has been considerable recent interest in the unique function of the hemopexin and hinge (OG domain) domains of MMP-9 (Steen et al., 2006). The hemopexin and hinge domains of MMP-9 were individually deleted using a two-step PCR approach (Fig. 3A) (Cao et al., 1998). The engineered MMP-9 deletion mutants were transiently transfected into COS-1 cells and immunoblotting of cell lysates and conditioned media was performed (Fig. 3B). Both wild type MMP-9 and MMP-9ΔPEX (i.e. deletion of PEX domain) were detected as high molecular weight glycosylated forms in the conditioned medium and low molecular weight non-glycosylated forms in the cell lysates (Fig. 3B) (Olson et al., 2000). As described by Steen et al. (Steen et al., 2006), no molecular weight shift of MMP-9ΔOG (deletion of hinge domain) was noted between conditioned medium and cell lysates, confirming the highly O-glycosylated region of hinge domain (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

The hemopexin domain of MMP-9 is required for MMP-9-enhanced cell migration.

A) Schematic diagram of wild-type and mutant MMP-9.

B) Expression of wild-type and mutant MMP-9 in COS-1 cells. The conditioned medium (CM) and lysates (CL) of COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type or mutant MMP-9 cDNAs were examined by Western blotting under denaturing conditions using anti-MMP-9 monoclonal antibodies.

C, D, E) Decreased cell migration in COS-1 cells transfected with MMP-9 PEX domain mutation. Migratory ability of COS-1 cells transfected with cDNAs as indicated was examined by a Transwell chamber migration assay (C, p-values reflect comparison with MMP-9 transfected cells: * p < 0.01) or phagokinetic assay (D). Cleared migratory tracks as depicted by the absence of gold particles in phagokinetic assay were measured by ImageJ NIH imaging software (E). p-values were calculated in comparison with MMP-9 transfected cells: * p < 0.01.

To determine the role of the hinge and hemopexin domains of MMP-9 in cell migration, COS-1 cells transfected with deletion mutants were compared to wild type MMP-9 cDNA in the Transwell chamber migration assay. Cells transfected with MMP-9ΔOG cDNA exhibited enhanced cell migration as compared to MMP-9ΔPEX; deletion of either the hinge region or hemopexin domain resulted in significantly reduced MMP-9-enhanced cell migration (p<0.01) (Fig. 3C). However, deletion of the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 resulted in decreased protein secretion into the conditioned media (Fig. 3B), but no apparent effect on mutant MMP-9 protein expression (i.e. cell lysates) was noted, suggesting that deletion of this relative large domain interferes with protein trafficking. To circumvent this problem, a substituted mutation was generated. Because the PEX domain of MMP-1 does not form homodimers, a chimera between MMP-9 and MMP-1 was engineered by replacing the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 with that of MMP-1 to generate MMP-9/MMP-1PEX chimera and its biological properties were investigated. Both glycoslated (i.e. in conditioned medium) and non-glycoslated (i.e. in cell lysate) MMP-9/MMP-1PEX were readily detected in cDNA-transfected COS-1 cells (Fig. 3B). Substitution of the PEX domain of MMP-9 with that of MMP-1 (i.e. MMP-9/MMP-1PEX) resulted in decreased cell migration as compared to wild type MMP-9, but comparable to cells transfected with MMP-1 cDNA (Fig. 3C). These data support an important role for the MMP-9 PEX domain in cell migration and presumably its role in homodimer formation.

To further confirm the role of the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 in cell migration, wild-type and mutant MMP-9-transfected cells were subjected to phagokinetic migration analysis which permits quantification by clearance of colloidal gold particles within the cell migratory path (Fig. 3D and 3E). In agreement with the data from the Transwell chamber migration assay (Fig. 3C), cells transfected with wild-type MMP-9 cDNA displayed enhanced migration (i.e. 4.7% particle phagocytosed) as compared to GFP-transfected cells (i.e. 1.2% phagocytosed). The stimulatory effect of MMP-9 on cell migration was decreased in cells transfected with MMP-9 mutations (MMP-9ΔPEX: 2.1%; MMP-9/MMP-1PEX: 3.3%; MMP-9ΔOG: 3.6%, Fig.3D-a,b,c,d,e).

Differential effect of MMP inhibitors on MMP-9-enhanced cell migration

X-ray crystallographic analysis of MMP-9 suggests that the hemopexin domain is involved in homodimer formation (Cha, 2002). Using non-denaturing conditions in Western blotting, we confirmed that MMP-9 forms a homodimer in the conditioned medium of transfected COS-1 cells. Replacement of the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 with that of MMP-1 (MMP-9/MMP-1PEX) failed to result in homodimer formation (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Interference of MMP-9-induced cell migration by TIMP-1, but not TIMP-2.

A) Detection of MMP-9 dimer in the conditioned medium of transfected COS-1 cells. The conditioned media from COS-1 cells transfected with MMP-9 or MMP-9/MMP-1PEX cDNAs were examined by Western blotting under non-denaturing conditions using anti-MMP-9 antibodies. The homodimer was identified in COS-1 cells expressing wild-type MMP-9, but not in the MMP-9/MMP-1PEX.

B) Expression of TIMP-1, but not TIMP-2 in cells interferes with MMP-9-mediated cell migration. COS-1 cells were co-transfected with MMP-9 or MMP-9/MMP-1PEX along with TIMP-1 or TIMP-2 cDNAs and cell migration was assessed by a Transwell chamber migration assay. * p < 0.01

C) Exogenous of TIMP-1, but not TIMP-2 inhibits MMP-9-induced cell migration. COS-1 cells transfected with MMP-9 cDNAs were incubated with exogenous TIMP-1 (50 nM) or TIMP-2 (50 nM) followed by the Tranwell chamber migration assay. * p < 0.01

It has been demonstrated that the C-terminus of TIMP-1, but not TIMP-2, binds to the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 (Goldberg et al., 1992), whereas the N-terminus of both TIMP-1 and -2 binds to the catalytic center of active MMP-9. To explore if binding of TIMP-1 to the C-terminus of proMMP-9 interferes with enhanced cell migration, COS-1 cells co-transfected with MMP-9, along with TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 cDNAs, were examined in the Transwell migration assay (Fig. 4B). Significant decrease of MMP-9-enhanced cell migration was observed in cells expressing both MMP-9 and TIMP-1, but not MMP-9 and TIMP-2. This data suggests that TIMP-1 interference with MMP-9 homodimer formation results in diminished cell migration. As expected, TIMP-1 had no effect on MMP-9/MMP-1PEX -induced cell migration, which is consistent with the lack of binding between the hemopexin domain of MMP-1 and TIMP-1 (Goldberg et al. 1992; Olson et al., 2000). Addition of exogenous TIMP-1 inhibited cell migration but TIMP-2 did not (Fig. 4C).

To further determine if extracellular MMP-9 enhances cell migration, conditioned media from COS-1 cells transfected with wild-type MMP-9 cDNA (i.e. unprocessed and gelatin Sepharose purified proMMP-9) was added to MMP-9ΔPEX transfected and to native COS-1 cells followed by the Transwell migration assay. We found that exogenous MMP-9 was ineffective at enhancing the migration of native or MMP-9ΔPEX transfected cells (data not shown).

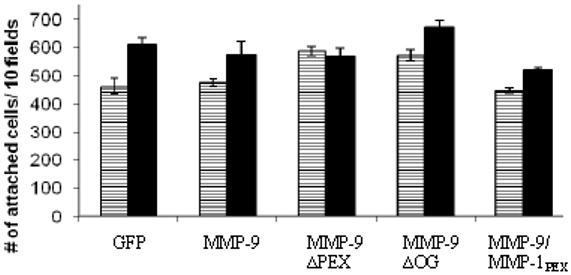

Lack of effect of MMP-9 on cell attachment

To determine whether the decreased cell migration in COS-1 cells transfected with MMP-9 mutants, as compared to wild-type MMP-9, was due to an effect on cell adhesion, a cell attachment assay was utilized. Cell attachment to culture plates after incubation for one and three hours was unaffected by wild-type and MMP-9 mutants (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

MMP-9 expression in transfected COS-1 cells has no effect on cell attachment. COS-1 cells transfected with GFP, MMP-9 and MMP-9 mutant cDNAs were incubated in polycarbonate wells and cell attachment was measured after 1 hour (white) and 3 hours (black). No significant differences in cell attachment were noted at either time point.

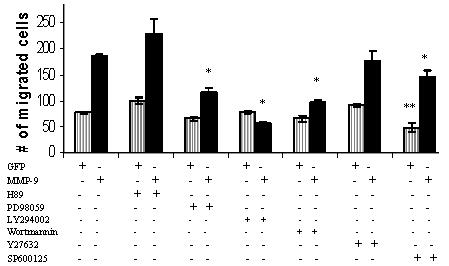

Effect of inhibitors of signal transduction pathways on MMP-9 induced cell migration

Inhibitors of signal transduction pathways were tested to investigate intracellular pathways involved in MMP-induced cell migration. We found that MAPK inhibitor (PD98059) (Dudley et al., 1995) and PI3K inhibitors (LY-294002 and wortmannin) (Vlahos et al., 1994) inhibited MMP-9-induced cell migration (Fig. 6). SP600125 inhibited baseline (GFP cDNA transfected) cell migration by 38%; MMP-9 induced cell migration was inhibited to a lesser extent (22%). These latter results link the JNK pathway primarily to the basal level of cell migration (Bennett et al., 2001). Y-27632 and H89 exhibited no effect on either GFP or MMP-9 transfected cells, thus suggesting that protein kinase A and ROCK pathways are not involved in MMP-9 enhancement of COS-1 cell migration (Chitaley et al., 2001; Chijiwa et al., 1990).

Figure 6.

Differential effect of small molecular inhibitors on MMP-9-meidated cell migration. COS-1 cells transfected with GFP control and MMP-9 cDNAs were incubated with PD89059 (10 μM), LY294002 (10 μM), Y27632 (1 μM), H89 (10 μM), wortmannin (10 μM) or SP600125 (10 μM) for 6 hours in the Transwell chamber cell migration assay. * p < 0.05 compared to MMP-9 and ** p < 0.05 compared to GFP.

Discussion

Cell migration and invasion are complex processes that have a key role in numerous biological and pathological conditions including embryonic development, wound healing, immune response, atherosclerosis, and cancer (Ridley et al., 2003). Among the multiple proteases orchestrating cell migration, MMPs have been the most widely studied.

MMPs and other proteases have been shown to induce cell invasion by degrading the ECM, thereby facilitating migration through tissues. It is generally assumed that activation of proMMPs is required for this cell locomotion effect. Our experimental results run contrary to this expectation. Following transfection of MMP cDNA into monkey kidney (COS-1) and human breast cancer (MCF-7) cells, we demonstrated that several proMMPs enhanced cell migration. By employing MMP inhibitors or expressing constitutively inactive MMPs in COS-1 cells, we demonstrated for the first time that enzymatic activity of MMPs is not a prerequisite for MMP-mediated cell migration.

Since proMMP-9 exerts a potent effect on cell migration, displays unique structural properties (e.g. long hinge domain, PEX homodimer formation), and is implicated in numerous pathological processes, such as inflammation and cancer, we chose to mutate the domains of MMP-9 cDNA to better understand their role in cell migration. Using MMP-9 as a model, we demonstrated that the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 is required for MMP-9-mediated cell migration, suggesting a novel role for the PEX domain of MMPs in enhancement of migration. Substitution of the hemopexin domain of MMP-9 with that of MMP-1 decreased MMP-9-enhanced cell migration, but the level of cell migration was still above the basal control level of GFP-transfected cells (Fig.3C). However, we also demonstrated that the hinge region (O-glycosylation domain) of MMP-9 contributes to MMP-9-mediated cell migration (Fig.3C). It has been proposed that the hinge region of MMP-9 correctly orients the PEX domain in order to facilitate binding to various molecules (Steen et al., 2006; Rosenblum et al., 2007). In terms of examination of other MMPs without a PEX domain, we have evaluated MMP-7 transfected cells and noted that migration was approximately equivalent to MMP-9 without PEX domain transfected cells (see supplemental figure). It needs to be noted, however, that MMP-7 contains an abbreviated hinge region which complicates analysis of the function of the PEX versus hinge domain.

Although the hemopexin domain of different MMPs displays distinct features, e.g. binding to different TIMPs, forming homo- and heterodimer, etc.(Nagase et al., 2006), the PEX domain of MMPs exhibit similar 3-dimensional structures composed of a disc-like shape, with the chain folded into a β-propeller structure that has pseudo four-fold symmetry (Iyer et al., 2006). Each propeller contains a sheet of four antiparallel strands with peptide loops linking one sheet to the next. Only strands 1-3 within each blade are topologically conserved and can be superimposed. The outer strand 4 of each blade deviates considerably between different MMP PEX domains (Cha et al., 2002). . This suggests that the inner three strands constitute the shared common structural framework making up the β-propeller architecture, while the outer strand of each blade mediates contacts with other specific protein components and provide unique functions to the PEX domain, i.e. capacity for cell migration. We hypothesize that there are structural amino acids in the hemopexin domain of MMPs required for enhanced cell migration. Our observation that different MMPs displayed distinct capability for enhanced cell migration (Fig. 1) support the structural difference of the hemopexin domain of MMPs.

Although MMP-9, like MMP-2, is a secreted protein and has been studied for its capacities to degrade the ECM, others have suggested that it may have additional roles either in the cytoplasm of the cell (Schulz et al., 2007) and/or the cell membrane (Hu and Ivashkiv, 2006). The PEX domain of MMP-9 is known to bind to several cell surface molecules including LRP-1, LRP-2, CD44, RECK, Ku, and type IV collagen (Steen et al., 2006; Sternlicht and Werb, 2001; Monferran et al., 2004), but the precise roles of these interactions remains speculative. To examine the role of secreted MMP-9 on cell migration, we examined the effect of adding MMP-9 (isolated from transfected cell condition medium) to cells (data not shown). Exogenous MMP-9 did not enhance migration of non-transfected COS-1 cells. This negative data suggests that enhancement of cell migration by proMMP-9 may reflect an unidentified intracellular event.

In addition to binding to the catalytic domain of MMP-9, TIMP-1 forms a complex with the PEX domain of proMMP-9 (Zucker et al., 1999). In our migration assay using either exogenous TIMP or TIMP cDNA transfected cells, TIMP-1 inhibited migration of proMMP-9 expressing cells, whereas TIMP-2 did not. Since both TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 inhibit activated MMP-9, these data suggest an inhibitory effect related to TIMP-1 binding to the PEX domain of proMMP-9. Whereas comprehensive studies by Olson et al. concluded that TIMP-1 binds to either monomeric or dimeric forms of proMMP-9 (Olson et al., 2000), an earlier publication reported that the proMMP-9:TIMP-1 complex interfered with MMP-9 homodimer formation (Goldberg et al., 1992).

Inhibitors of cell signaling were employed in order to illuminate pathways involved in MMP-9 induced cell migration. We demonstrated that the MAPK and PI3K pathways, but not the protein kinase A and ROCK pathways are linked to MMP-9 induced cell migration. Inhibition of the JNK pathway affected basal cell migration to a greater extent than MMP-9 induced cell migration. In accordance with our results, Tian et al. reported that interference with the ERK1/2 pathway affected epithelial cell migration (Tian et al., 2007). However, they also reported that activated MMP-9 participated in epidermal growth factor/transforming growth factor-β1 induced cell migration (Tian et al., 2007). In our hands, we found that the dose of MMP-2/-9 inhibitor required to interfere with cell migration by Tian et al., (Tian et al., 2007) also decreased cell secretion of MMP-9, thereby implying cell toxicity (Dufour et al. unpublished observations).

Of relevance to our observations, Hu and Ivashkiv (Hu and Ivashkiv, 2006) recently reported that MMP-9 is a key player in migration of dendritic cells through uncoated filters in a transwell chamber assay. In contrast to the epithelial cells (COS-1 and MCF-7) employed in our experiments, dendritic cells secrete active MMP-9 which becomes membrane-bound to αMβ2 integrin and CD44, leading to modulation of CCL5 and activation of JNK signaling. Both the JNK inhibitor (SP600125) and a synthetic inhibitor of MMPs, abrogated dendritic cell migration. These data suggest that dendritic cell migration is dependent on activated MMP-9 and JNK signaling, whereas epithelial cell migration is independent of activated MMP-9, but dependent on the MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways (Fig. 6).

In summary, we have demonstrated that MMPs enhance epithelial cell migration, independent of proteolytic activity. The PEX domain of proMMP-9 is a prerequisite for enhancement of cell migration, possibly due to homodimer formation. Additional studies are needed to better understand the detailed dynamics of MMP-induced cell migration with the recognition that the underlying mechanism may differ depending on cell type. We propose that development of selective inhibitors of the PEX domain of MMP-9 may provide an attractive option for treatment of diseases in which MMP-9 plays a pathologic role.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by NYSTAR FDP C040076 (NS), NIH grant RO1CA11355301A1, the Walk-for-Beauty Foundation (JC), a Research Enhancement Award Program (REAP) grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, a Merit Review grant from the Department of Veterans Affairs, and an Idea Award from Department of Defense (SZ).

References

- Abecassis I, Olofsson B, Schmid M, Zalcman G, Karniguian A. RhoA induces MMP-9 expression at CD44 lamellipodial focal complexes and promotes HMEC-1 cell invasion. Exp. Cell. Res. 2003;291:363–376. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrect-Buehler G. The phagokinetic tracks of 3T3 cells. Cell. 1997;11:395–404. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allan JA, Docherty AJP, Barker PJ, Huskisson NS, Reynolds JJ, Murphy G. Binding of gelatinases A and B to type-1 collagen and other matrix components. Biochem. J. 1995;309:299–306. doi: 10.1042/bj3090299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannikov GA, Karelina TV, Collier IE, Marmer BL, Goldberg GI. Substrate binding of gelatinase B induces its enzymatic activity in the presence of intact propeptide. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:16022–16027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110931200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BL, Sasaki DT, Murray BW, O’Leary EC, Sakata ST, Xu W, Leisten JC, Motiwala A, Pierce S, Satoh Y, Bhagwat SS, Manning AM, Anderson DW. SP600125, an anthrapyrazolone inhibitor of Jun N-terminal kinase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2001;98(24):13681–13686. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251194298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorklund M, Koivunen E. Gelatinase-mediated migration and invasion of cancer cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2005;1755:37–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burg-Roderfeld M, Roderfeld M, Wagner S, Henkel C, Grotzinger J, Roeb E. MMP-9-hemopexin domain harpens adhesion and migration of colorectal cancer cells. Int. J. of Onc. 2007;30:985–992. doi: 10.3892/ijo.30.4.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Rehemtulla A, Bahou WF, Zucker S. Membrane type matrix metalloproteinase 1 activates pro-gelatinase A without furin cleavage of the N-terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:30174–30180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.30174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Drews M, Lee HM, Conner C, Bahou WF, Zuckers S. The propeptide domain of membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase is required for binding of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases and for activation of pro-gelatinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:34745–34752. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.52.34745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao J, Rehemtulla A, Pavlaki M, Kozarekar P, Chiarelli C. Furin Directly Cleaves proMMP-2 in the trans-Golgi Network Resulting in a Nonfunctioning Proteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:10974–10980. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412370200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha H, Kopetzki E, Huber R, Lanzendorfer M, Brandstetter H. Structural basis of adaptive molecular recognition by MMP-9. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;320:1065–1079. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00558-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chijiwa T, Mishima A, Hagiwara M, Sano M, Hayashi K, Inoue T, Naito K, Toshioka T, Hidaka H. Inhibition of forskolin-induced neurite outgrowth and protein phosphorylation by a newly synthesized selective inhibitor of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, N-[2-(p-bromocinnamylamino)ethyl]-5-isoquinolinesulfonamide (H-89), of PC12D pheochromocytoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265(9):5267–5272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chitaley K, Wingard C, Webb R, Branam H, Stopper V, Lewis R, Mills T. Antagonism of Rho-kinase stimulate rat penile erection via a nitric oxide-independent pathway. Nat. Med. 2001;7:119–122. doi: 10.1038/83258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Girolamo N, Indoh I, Jackson N, Wakefield D, McNeil HP, Yan W, Geczy C, Arm JP, Tedla N. Human mast cell-derived gelatinase B (matrix metalloproteinase-9) is regulated by inflammatory cytokines: role in cell migration. J. Immun. 2006;177(4):2638–2650. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.4.2638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley DT, Pang L, Decker SJ, Bridges AJ, Saltiel AR. A synthetic inhibitor of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. Proc. Natl.Acad. Sci USA. 1995;92(17):7686–7689. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.17.7686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg G, Strongin A, Collier IE, Genrich T, Marmer B. Interaction of 92-kDa type IV collagenase with the tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases prevents dimerization, complex formation with interstitial collagenase, and activation of the proenzyme with stromelysin. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:4583–4591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross J, Lapiere C. Collagenolytic activity in amphibian tissues: a tissue culture assay. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1962;48:1014–1022. doi: 10.1073/pnas.48.6.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J, Van den Steen P, Sang Q-X, Opdenakker G. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors as therapy for inflammatory and vascular diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2007;6(6):480–498. doi: 10.1038/nrd2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y, Ivashkiv L. Costimulation of chemokine receptor signaling by matrix metalloproteinase-9 mediates enhanced migration of IFN-α dendritic cells. J. of Immunol. 2006;176:6022–6033. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.10.6022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer S, Visse R, Nagase H, Acharya KR. Crystal structure of an active form of human MMP-1. J Mol Biol. 2006 Sep 8;362(1):78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.079. 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jozic D, Bourenkov G, Lim N, Visse R, Nagase H, Bode W, Maskos K. X-ray structure of human proMMP-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:9578–9585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411084200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight C, Willenbrock F, Murphy G. A novel coumarin-labelled peptide for sensitive continuous assays of the matrix metalloproteinases. FEBS letter. 1992;296:263–266. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M, Fridman R, Mobahery S. Extracellular proteases as targets for treatment of cancer metastases. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2004;33:401–409. doi: 10.1039/b209224g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PPH, Hwang JJ, Murphy G, Ip MM. Functional significance of MMP-9 in tumour necrosis factor-induced proliferation and branching morphogenesis of mammary epithelial cells. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3764–3773. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.10.7697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massova I, Kotra L, Fridman R, Mobashery S. Matrix metalloproteinases: structures, evolution, and diversification. FASEB journal. 1998;12:1075–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monferran S, Paupert J, Dauvillier S, Salles B, Muller C. The membrane form of the DNA repair protein Ku interacts at the cell surface with metalloproteinase 9. EMBO J. 2004;23:3758–3768. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Woessner JF. Matrix Metalloproteinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:21491–21494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H, Visse R, Murphy G. Structure and function of matrix metalloproteinases and TIMPs. Cardiovasc Res. 2006 Feb 15;69(3):562–73. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.12.002. 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson M, Bernardo M, Pietila M, Gervasi D, Toth M, Kotra L, Massova I, Mobashery S, Fridman R. Characterization of the monomeric and dimeric forms of latent and active Matrix Metalloproteinase-9. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:2661–2668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opdenakker G, Van Damme J. Chemokines and proteinases in autoimmune diseases and cancer. Verh. K. Acad.Geneeskd. Belg. 2002;64:105–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos-DeSimone N, Hahn-Dantona E, Sipley J, Nagase H, French D, Quigley J. Activation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) via a converging plasmin/stromelysin-1 cascade enhances tumor cell invasion. J. Biol. Chem. 1999;274:13066–13076. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.19.13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridley A, Schwartz M, Burridge K, Firtel R, Ginsberg M, Borisy G, Parsons J, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblum G, Van den Steen P, Cohen S, Grossmann G, Frenkel J, Sertchook R, Slack N, Strange R, Opdenakker G, Sagi I. Insights into the Structure and Domain Flexibility of Full-Length Pro-Matrix Metalloproteinase-9/Gelatinase B. Structure. 2007;15:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanceau J, Truchet S, Bauvois B. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 silencing by RNA interference triggers the migratory-adhesive switch in Ewing’s sarcoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:36537–36546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304300200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz R. Intracellular targets of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in cardiac disease: rationale and therapeutic approches. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007;47:211–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steffensen B, Wallon UM, Overall CM. Extracellular matrix binding properties of recombinant fibronectin type II-like modules of human 72-kDa gelatinase/type IV collagenase. High affinity binding to native type I collagen but not native type IV collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:11555–11566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.19.11555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sternlicht M, Werb Z. How matrix metalloproteinases regulate cell behavior. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2001;17:463–516. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.17.1.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y, Chen Y, Chang C, Hung C, Wu M, Phillips A, Yang C. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor-beta1 enhance HK-2 cell migration through a synergistic increase of matrix metalloproteinase and sustained activation of ERK signaling pathway. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313(11):2367–2377. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Steen P, Van Aelst I, Hvidberg V, Piccard H, Fiten P, Jacobsen C, Moestrup S, Fry S, Royle L, Wormald M, Wallis R, Rudd P, Dwek R, Opdenakker G. The hemopexin and O-glycosylated domains tune gelatinase/MMP-9 bioavailibility via inhibition and binding to cargo receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:18626–18637. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512308200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahos CJ, Matter WF, Hui KY, Brown RF. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:5241–5148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker S, Lysik R, Zarrabi M, Moll U. Mr 92,000 Type IV collagenase is increased in plasma of atients with colon cancer and breast cancer. Canc. Res. 1993;53:140–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker S, Conner C, DiMassimo BI, Ende H, Drews M. Seiki, M. Bahou WF. Thrombin induces the activation of progelatinase A in vascular endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:23730–23738. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.40.23730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker S, Hymowitz M, Conner C, Zarrabi H, Hurewitz A, Matrisian L, Boyd D, Nicolson G, Montana S. Measurement of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in blood and tissues: clinical and experimental applications. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1999;878:212–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07687.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker S, Cao J, Chen WT. Critical appraisal of the use of matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors in cancer treatment. Oncogene. 2000;19:6642–6650. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.