Abstract

Appendage regeneration is a complex and fascinating biological process exhibited in vertebrates by urodele amphibians and teleost fish. A current focus in the field is to identify new molecules that control formation and function of the regeneration blastema, a mass of proliferative mesenchyme that emerges after limb or fin amputation and serves as progenitor tissue for lost structures. Two studies published recently have illuminated new molecular regulators of blastemal proliferation. After amputation of a newt limb, the nerve sheath releases nAG, a blastemal mitogen that facilitates regeneration. In amputated zebrafish fins, regeneration is optimized through depletion of the microRNA miR-133, a mechanism that requires Fgf signaling. These discoveries establish research avenues that may impact the regenerative capacity of mammalian tissues.

Introduction

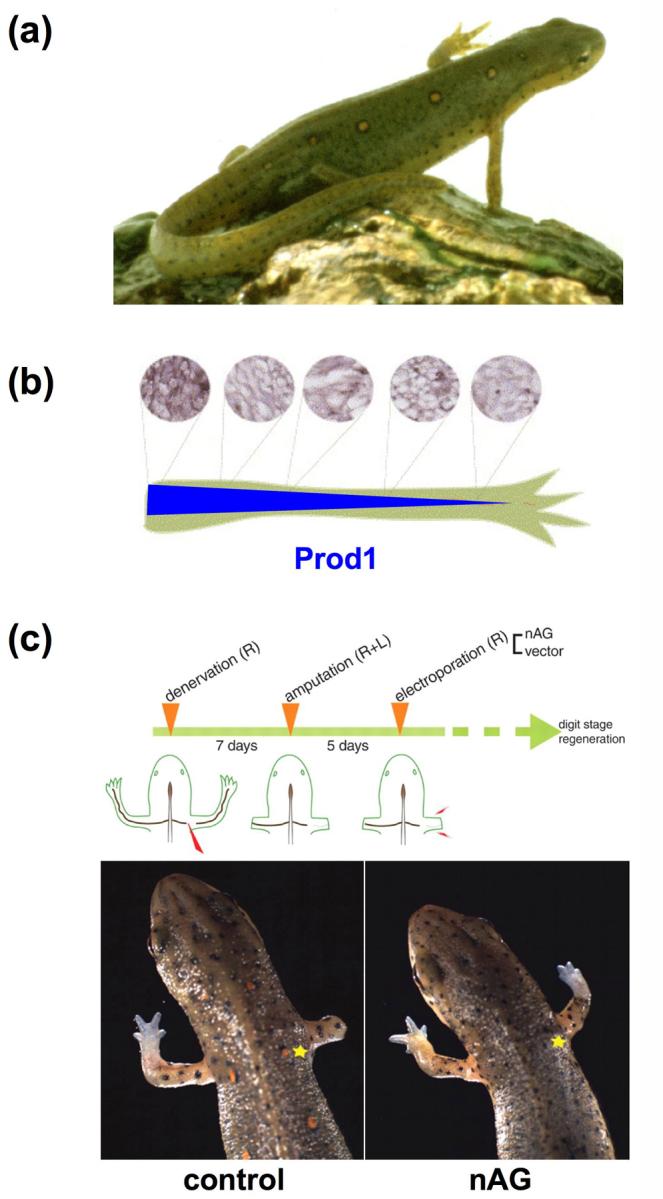

It has been known for centuries that certain non-mammalian vertebrates like urodele amphibians and teleost fish regenerate complex tissues much more effectively than mammals. Salamanders have long been the central characters employed in vertebrate regeneration studies, due to their unparalleled abilities to regenerate many complex organs, including limbs, tail, eye parts like retina and lens, spinal cord, portions of intestines, and jaws (Figure 1a) [1,2]. These animals are also particularly amenable to cell and tissue grafts — the lion’s share of techniques applied in regeneration research until the end of the previous century. More recently, the zebrafish has joined newts and axolotls as a popular and informative model system for regeneration (Figure 2a). Like urodeles, zebrafish and other teolosts exhibit an enhanced capacity to regenerate many adult tissues [3-6]. While grafting and cell transplantation are not yet easily accomplished in adult zebrafish, their bonus is the array of tools available for gene discovery and molecular characterization - mutagenesis screens, transgenesis, microarrays, antibodies, and so on.

Figure 1.

Newt limb regeneration and nerve/nAG dependence. (a) Adult newts faithfully regenerate extremities, including limbs and tail. (b) Prod1 is a cell surface receptor that binds newt Anterior gradient protein (nAG) and is expressed in a proximodistal gradient in newt limbs (top = antibody stains for Prod1; bottom = gradient of Prod1 expression along the nerve sheath) [48]. (c) (Top) Experimental procedure for electroporation of nAG into amputated forelimbs. (Bottom) Introduction of nAG cDNA under conditions of denervation rescues tissue outgrowth and approximate proximodistal pattern [20]. (Asterisk = site of plasmid introduction.)

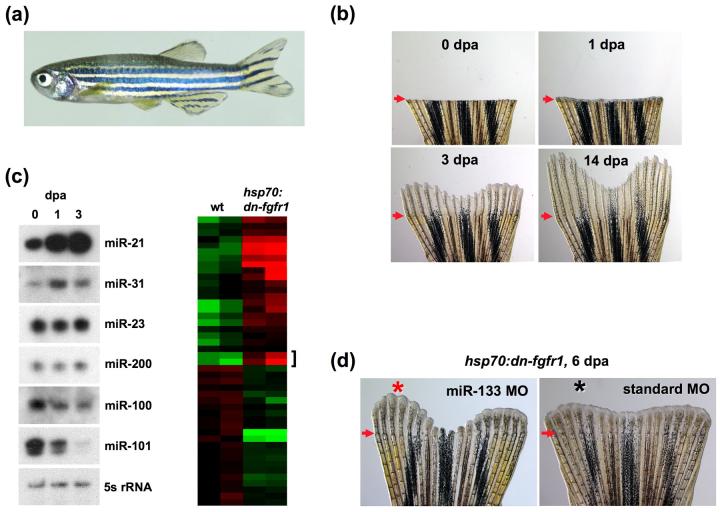

Figure 2.

Zebrafish fin regeneration and the impact of miRNAs. (a) An adult zebrafish is able to regenerate all fin types, with the caudal fin typically studied. (b) An amputated caudal fin undergoes rapid regeneration following amputation (0 day post amputation; dpa), completing most of the process by 14 dpa. (c) (Left) miRNAs are dynamically regulated in response to amputation, as validated by Northern blot hybridizations. (Right) A subset of miRNAs are regulated by Fgfs during regenerative outgrowth, indicated by a heat map from microarray experiments (green = lower expression, red = higher expression; hsp70:dn-fgfr1 = transgenic strain that permits inducible inhibition of Fgf receptors). (d) Morpholino-mediated antagonism of miR-133 (red asterisk) accelerated regeneration under conditions of Fgf receptor inhibition [44]. (arrows = amputation plane; bracket = miR-133; asterisk = lobe in which morpholino was introduced)

Major appendages - limbs, tail, and fins - are the most studied regenerative model organs in urodeles and telosts. This is based on the accessibility of the organs, as well as the efficiency and near perfection of restoration of a complex three-dimensional tissue. A historic aim of the field is to understand formation and persistence of the blastema, a mass of proliferative mesenchyme that arises at the stump and is patterned into the structures lost by amputation. The majority of past research on appendage regeneration utilized transplants, dissections, and irradiation, identifying many of the principles that define regenerative biology. By contrast, today’s research centers on identifying and functionally defining “regeneration genes” that underlie these principles. Many studies have implicated or demonstrated functions during appendage regeneration for several ubiquitous signaling pathways important for embryonic patterning and organogenesis (e.g. Wnts, Fgfs, Bmps, Notch, retinoic acid, etc.), work that is reviewed in detail elsewhere [7]. Here, we highlight two very recent discoveries utilizing newts and zebrafish that revealed new molecular perspective on how a blastema is made and maintained.

nAG directs newt limb regeneration from the nerve

Amphibian limb regeneration is arguably nature’s most remarkable regenerative event. Adult anurans (frogs and toads) have limited capacity to regenerate amputated limbs; a spike formed from cartilage and connective tissue is the most that can be expected [8]. By contrast, urodele amphibians like salamanders restore these tissues as well as skeletal muscle and bone, in correctly patterned amounts. Following amputation of a newt limb, an epidermis forms over the wound that will interact with underlying mesenchymal tissue for the duration of the regenerative process. Stimulated by this interaction, the mesenchyme disorganizes and proliferates to establish the blastema. Current evidence indicates that the salamander limb blastema is derived from multiple sources. These include contributions by skeletal muscle satellite cells and possibly other tissue-specific progenitor cells, as well as mononucleated progeny from the dedifferentiation and fragmentation of skeletal myotubes [9,10]. The blastema is a transient stage; a new limb bud extends from this structure and patterned digits become visible within several weeks.

The limb blastema requires innervation to proliferate and replace structures, a dependence that was first identified in 1823. If nerves are severed at the base of the limb prior to amputation, a stunted blastema forms and regeneration is blocked. By contrast, if denervation is carried out at developmental stages after blastema formation, proliferation is inhibited although the regenerate continues to lengthen and differentiate [11-13]. These observations suggest that release of a neurotrophic factor(s) is required for blastemal proliferation and maintenance of regenerative outgrowth. This phenomenon has been demonstrated for a variety of species and organs; for example, fin regeneration in the teleost Fundulus also requires a nerve supply [14]. Furthermore, surgical supplementation of nervous system tissue has been reported to facilitate ectopic limb outgrowth from uninjured limbs of adult salamanders [15], and even to support regenerative events in amputated hindlimbs of the neonatal opossum [16]. Through the years, candidate neurotrophic factors have included Fgfs, neuregulin, transferrin, and other molecules, but none of these have fulfilled all relevant properties, including: 1) presence in limb nervous tissue; 2) activity as a blastemal mitogen; and 3) ability to rescue regeneration of a denervated and amputated limb [17-19].

Recently, a strong candidate for a nerve-derived blastemal mitogen emerged, identified as newt Anterior gradient, or nAG [20]. nAG is related by sequence to the Xenopus protein XAG2, expressed in the cement gland of Xenopus embryos and able to induce an additional cement gland when introduced ectopically [21]. Using a yeast two-hybrid screen, nAG appeared as a binding partner for Prod1, a GPI-linked cell surface protein previously implicated as a graded determinant of proximodistal identity (Figure 1b) [22]. nAG shows minimal expression in the uninjured limb, but is induced in Schwann cells that surround regenerating axons by 5 days post-amputation (dpa), fulfilling one aspect of the nerve-derived factor. Later, nAG becomes localized to glandular tissues within the regeneration epidermis, where it is maintained through at least 12 dpa. Recombinant nAG increased cell cycle entry in cultured blastemal cells, fulfilling a second aspect of the nerve-derived factor. Finally, electroporation of nAG cDNA into early blastemas of amputated limbs under conditions of denervation was sufficient to induce expression in epidermal glands. Moreover, this treatment supported regeneration of new structures of the approximate size and scale of fully innervated contralateral control limbs (Figure 1c). Interestingly, the new limb structures were not without some defects; they lacked nervous tissue (and thus did not simply induce neurogenesis) and were deficient in skeletal muscle.

The discovery of blastemal control by nAG appears to be a major turning point in understanding how nerves direct limb regeneration. That nAG could rescue limbs so well is striking, especially given an inexact method of delivery by electroporation (Figure 1c). This finding suggests that nerve-derived nAG is permissive rather than instructive for regeneration, perhaps initiating dialogue that establishes stable nAG synthesis in glands of the wound epidermis. It would be interesting to determine if a nAG/Prod1 system functions in other species and regenerative organs, and if genetic lesions in the system prevent regeneration. Moreover, will introducing this mechanism permit regeneration in regeneration-incompetent systems in addition to the denervated newt limb? Studies here might begin with partially competent frog limbs. Further mechanistic work into the regulation, the targets, and the signal transduction started by nAG could open up many new avenues for understanding and altering regenerative capacity.

miR-133 modulates zebrafish fin regeneration

Zebrafish fins are relatively simple, nearly symmetric tissues composed of concave, facing hemirays that surround connective tissue, including fibroblasts and osteoblasts, as well as nerves and blood vessels [23]. Fin regeneration is completed through three sequential events: (1) wound healing; that is, covering of the wound by an epidermis; (2) blastema formation within 1-2 dpa by rapid disorganization, migration, and proliferation of underlying connective tissue; and (3) regenerative outgrowth, involving coordinated proliferation, patterning, and differentiation events. Each fin ray has its own blastema, which is then maintained as a zone of highly proliferative mesenchyme at the distal fin tip until regeneration is completed about two weeks later [24]. A vascular plexus forms to support blastemal tissue, events that are essential for normal regeneration [25,26]. The regenerate attains pigmentation pattern from two contributing populations: new differentiation from undifferentiated melanocyte progenitor cells, and distal migration by existing, differentiated melanocytes [27]. While zebrafish can regenerate lost structures after major amputations of the caudal fin (up to ∼95% loss), other teleosts can even regenerate the tail proper. For instance the electric fish Sternopygus macrurus will regenerate skeletal muscle, vertebrae, spinal cord, and electric organ tissues after tail amputation [28].

During fin regeneration as well as other examples of complex tissue regeneration, differentiated adult tissue is rapidly transformed to proliferating, actively patterned tissue (Figure 2b). This sharp anatomical change is accompanied by massive changes in genetic programs [29,30], mediated in part by the activity of secreted ligands like Fgfs, Wnts, and Activin(s) that are induced after amputation [31-35]. Additional modes of regulation are also likely to work in concert with these signaling pathways to achieve the major developmental change necessary for regeneration. Within the last 5 years, there has been an explosion of studies detailing posttranscriptional regulation of genetic programs by microRNAs (miRNAs), known overseers of developmental change in multiple systems [36-38]. These small, noncoding RNAs bind to complementary sites on the 3′ UTR of dozens of target mRNAs to perturb their expression. In vertebrates, this is most often achieved through inhibition of protein translation, regulating events like cellular proliferation and differentiation, organogenesis, and progenitor cell maintenance [39-41]. Recently, miRNA-profiling studies identified numerous miRNAs in zebrafish appendages that show different expression levels in regenerating fins compared to uninjured tissues. Interestingly, the levels of several of these miRNAs were dependent on Fgf signaling, a pathway essential for blastemal formation and maintenance (Figure 2c) [33]. miR-133, previously identified as a regulator of skeletal and cardiac muscle cell differentiation [42,43], was depleted during fin regeneration. This depletion was reversed upon brief inhibition of Fgf receptors (Fgfrs) [44].

One might expect that miRNAs with higher levels in uninjured fins act like brakes in the process. Indeed, gain-of-function studies to increase levels of miR-133 through electroporation slowed regeneration. More remarkably, and akin to rescues by nAG in newt limbs, morpholino-mediated antagonism of miR-133 function increased blastemal proliferation and the lengths of regenerates by 20-40%. The latter experiments were performed during transgenic blockade of Fgfr activity, conditions that normally block regeneration and increase miR-133 levels (Figure 2D). Such a rescue phenotype suggested that a significant function of Fgf signaling during regeneration is to maintain low miR-133 levels. Critical for interpretation of miRNA roles is its mRNA target population. Interestingly, one miR-133 target validated in this study was the kinase Mps1, previously identified through mutagenesis screens as a positive regulator of blastemal proliferation [45]. Taken together, this study indicates a circuit promoting regeneration in which a single miRNA family or family member is depleted through the activity of Fgfs, removing repressive effects of that miRNA on target genes like mps1.

As with nAG, there is much to learn about how miR-133 and other miRNAs impact regeneration. First, that miR-133 is highest in uninjured fins suggests that its presence is most important in the absence of injury. Here, it is possible that miR-133 maintains organ homeostasis by subduing undesired growth mechanisms. Future studies to address this must include removal of miR-133 activity in uninjured fins, possibly through the use of transgenic “sponge” constructs [46]. Second, the signal transduction by which Fgfr activity impacts levels of miR-133 and other miRNAs during regeneration is unknown. Third, miR-133 is one of many miRNAs that are differentially regulated during fin regeneration, and there are likely to be additional miRNA brakes for the process. Conversely, some miRNAs were identified with greater amounts during regeneration than in uninjured fins, and thus may have the function of accelerating the regenerative process. Fourth, miRNAs may participate in multiple aspects of regeneration not addressed in this study, including patterning and size control. A final thought is that miRNAs show high sequence conservation across the animal kingdom, regardless of regenerative potential. It will be important to test if miRNAs and their target populations prosecute regeneration in other vertebrate organs/animals, and to test whether experimental manipulation of individual miRNAs can improve regeneration in systems with low regenerative capacity.

Concluding remarks

Appendage regeneration is a historic field of experimental biology, dating back to Thevenot’s work on lizard tail regeneration in 1686 [47]. Regeneration research was initially slow to access tools of the molecular era that emerged last century, yet new approaches and model systems have been identified and regeneration is now impacting other fields and systems. Indeed, molecular regulators discovered through studies of appendage regeneration in salamanders and fish represent excellent candidates for guiding the regenerative activity of mammalian stem cells in vitro or in vivo. Within the last year, the discoveries of new regulators reviewed here have opened new avenues for investigation into mechanisms of regeneration. The biology of nAG embodies crosstalk between proximodistal position, nerves, blastema, and wound epidermis, promising fascinating mechanistic information. miRNAs like miR-133 have great potential to control a large population of target genes rapidly, and represent an attractive mode by which to regulate regenerative capacity. The next several years should reveal exciting new insights into the cellular and molecular interplay that inspires the theater of appendage regeneration.

Acknowledgments

We thank Airon Wills for helpful comments on the manuscript. V.P.Y. was supported by NIH training grant 2 T-32 HL007101-29 and is a postdoctoral fellow of the American Heart Association. Our laboratory’s work on zebrafish fin regeneration is supported by grants to K.D.P. from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1 R01 GM074057), Pew Charitable Trusts, and Whitehead Foundation.

References and recommended reading

Papers of particular interest, published within the annual period of review, have been highlighted as:

• of special interest

•• of outstanding interest

- 1.Brockes JP, Kumar A. Appendage regeneration in adult vertebrates and implications for regenerative medicine. Science. 2005;310:1919–1923. doi: 10.1126/science.1115200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tanaka EM. Regeneration: if they can do it, why can’t we? Cell. 2003;113:559–562. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00395-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Becker T, Wullimann MF, Becker CG, Bernhardt RR, Schachner M. Axonal regrowth after spinal cord transection in adult zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 1997;377:577–595. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970127)377:4<577::aid-cne8>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson SL, Weston JA. Temperature-sensitive mutations that cause stage-specific defects in Zebrafish fin regeneration. Genetics. 1995;141:1583–1595. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.4.1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science. 2002;298:2188–2190. doi: 10.1126/science.1077857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vihtelic TS, Hyde DR. Light-induced rod and cone cell death and regeneration in the adult albino zebrafish (Danio rerio) retina. J Neurobiol. 2000;44:289–307. doi: 10.1002/1097-4695(20000905)44:3<289::aid-neu1>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stoick-Cooper CL, Moon RT, Weidinger G. Advances in signaling in vertebrate regeneration as a prelude to regenerative medicine. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1292–1315. doi: 10.1101/gad.1540507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scadding SR. Phylogenic distribution of limb regeneration capacity in adult Amphibia. J Exp Zool. 1977;202:57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lo DC, Allen F, Brockes JP. Reversal of muscle differentiation during urodele limb regeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7230–7234. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.15.7230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10•.Morrison JI, Loof S, He P, Simon A. Salamander limb regeneration involves the activation of a multipotent skeletal muscle satellite cell population. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:433–440. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The authors show that Pax7+ cells contribute to blastemal tissue in amputated salamander limbs. This study indicates that there are likely to be multiple sources of progenitor cells in the blastema, including skeletal muscle satellite cells in addition to any natural contributions of cellular dedifferentiation.

- 11.Singer M. The influence of the nerve in regeneration of the amphibian extremity. Quart Rev Biol. 1952;27:169–200. doi: 10.1086/398873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todd TJ. On the process of reproduction of the members of the aquatic salamander. Quarterly Journal of Science, Literature and the Arts. 1823;16:84–96. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singer M, Craven L. The growth and morphogenesis of the regenerating forelimb of adult Triturus following denervation at various stages of development. J Exp Zool. 1948:279–308. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401080207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geraudie J, Singer M. Necessity of an adequate nerve supply for regeneration of the amputated pectoral fin in the teleost Fundulus. J Exp Zool. 1985;234:367–374. doi: 10.1002/jez.1402340306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Locatelli P. Der einfluss des nervensystems aud die regeneration. Arch Entw Mech Org. 1929;114:686–770. doi: 10.1007/BF02078924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizell M. Limb Regeneration: Induction in the newborn possum. Science. 1968;161:283–286. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3838.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brockes JP, Kintner CR. Glial growth factor and nerve-dependent proliferation in the regeneration blastema of Urodele amphibians. Cell. 1986;45:301–306. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90394-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mullen LM, Bryant SV, Torok MA, Blumberg B, Gardiner DM. Nerve dependency of regeneration: the role of Distal-less and FGF signaling in amphibian limb regeneration. Development. 1996;122:3487–3497. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.11.3487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Munaim SI, Mescher AL. Transferrin and the trophic effect of neural tissue on amphibian limb regeneration blastemas. Dev Biol. 1986;116:138–142. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(86)90050-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20••.Kumar A, Godwin JW, Gates PB, Garza-Garcia AA, Brockes JP. Molecular basis for the nerve dependence of limb regeneration in an adult vertebrate. Science. 2007;318:772–777. doi: 10.1126/science.1147710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The authors identify nAG as a binding partner for Prod1, expressed in the nerve sheath and epidermal tissues of the amputated and regenerating limb. nAG acts as a blastemal mitogen in vitro. Moreover, electroporation of nAG cDNA rescues defects in blastema proliferation and regenerative outgrowth in denervated limbs. Thus, nAG is an especially strong candidate for the long sought after nerve-derived blastemal mitogen.

- 21.Aberger F, Weidinger G, Grunz H, Richter K. Anterior specification of embryonic ectoderm: the role of the Xenopus cement gland-specific gene XAG-2. Mech Dev. 1998;72:115–130. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.da Silva SM, Gates PB, Brockes JP. The newt ortholog of CD59 is implicated in proximodistal identity during amphibian limb regeneration. Dev Cell. 2002;3:547–555. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00288-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Becerra J, Montes GS, Bexiga SR, Junqueira LC. Structure of the tail fin in teleosts. Cell Tissue Res. 1983;230:127–137. doi: 10.1007/BF00216033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Poss KD, Keating MT, Nechiporuk A. Tales of regeneration in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2003;226:202–210. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bayliss PE, Bellavance KL, Whitehead GG, Abrams JM, Aegerter S, Robbins HS, Cowan DB, Keating MT, O’Reilly T, Wood JM, et al. Chemical modulation of receptor signaling inhibits regenerative angiogenesis in adult zebrafish. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:265–273. doi: 10.1038/nchembio778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang CC, Lawson ND, Weinstein BM, Johnson SL. reg6 is required for branching morphogenesis during blood vessel regeneration in zebrafish caudal fins. Dev Biol. 2003;264:263–274. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rawls JF, Johnson SL. Zebrafish kit mutation reveals primary and secondary regulation of melanocyte development during fin stripe regeneration. Development. 2000;127:3715–3724. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.17.3715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zakon HH, Unguez GA. Development and regeneration of the electric organ. J Exp Biol. 1999;202:1427–1434. doi: 10.1242/jeb.202.10.1427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lien CL, Schebesta M, Makino S, Weber GJ, Keating MT. Gene expression analysis of zebrafish heart regeneration. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e260. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schebesta M, Lien CL, Engel FB, Keating MT. Transcriptional profiling of caudal fin regeneration in zebrafish. ScientificWorldJournal. 2006;6(Suppl 1):38–54. doi: 10.1100/tsw.2006.326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Jazwinska A, Badakov R, Keating MT. Activin-betaA signaling is required for zebrafish fin regeneration. Curr Biol. 2007;17:1390–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- This study used expression studies, pharmacological inhibitors, and antisense morpholinos to assign a role for Activin-betaA in zebrafish fin regeneration. The authors show that ActivinbetaA is induced within 6 hours of amputation, and required both early and late in the process for normal cell migration and blastemal proliferation.

- 32.Kawakami Y, Rodriguez Esteban C, Raya M, Kawakami H, Marti M, Dubova I, Izpisua Belmonte JC. Wnt/beta-catenin signaling regulates vertebrate limb regeneration. Genes Dev. 2006 doi: 10.1101/gad.1475106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee Y, Grill S, Sanchez A, Murphy-Ryan M, Poss KD. Fgf signaling instructs position-dependent growth rate during zebrafish fin regeneration. Development. 2005;132:5173–5183. doi: 10.1242/dev.02101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34•.Stoick-Cooper CL, Weidinger G, Riehle KJ, Hubbert C, Major MB, Fausto N, Moon RT. Distinct Wnt signaling pathways have opposing roles in appendage regeneration. Development. 2007;134:479–489. doi: 10.1242/dev.001123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- This study examines the functions of Wnt signaling during zebrafish fin regeneration using several transgenic and mutant strains. The authors implicate roles canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling in promoting regeneration, tempered by non-canonical Wnt signaling.

- 35•.Whitehead GG, Makino S, Lien CL, Keating MT. fgf20 is essential for initiating zebrafish fin regeneration. Science. 2005;310:1957–1960. doi: 10.1126/science.1117637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The authors use a forward genetic approach to identify a new Fgf ligand required for zebrafish fin regeneration. fgf20a expression is induced within hours of amputation, and a mutation in fgf20a blocks fin regeneration by preventing normal blastema formation. This study suggests that Fgf20a has a specific or predominant role during adult fin regeneration, with little or no embryonic requirement.

- 36.Giraldez AJ, Mishima Y, Rihel J, Grocock RJ, Van Dongen S, Inoue K, Enright AJ, Schier AF. Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science. 2006;312:75–79. doi: 10.1126/science.1122689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee RC, Feinbaum RL, Ambros V. The C. elegans heterochronic gene lin-4 encodes small RNAs with antisense complementarity to lin-14. Cell. 1993;75:843–854. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90529-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2000;403:901–906. doi: 10.1038/35002607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giraldez AJ, Cinalli RM, Glasner ME, Enright AJ, Thomson JM, Baskerville S, Hammond SM, Bartel DP, Schier AF. MicroRNAs regulate brain morphogenesis in zebrafish. Science. 2005;308:833–838. doi: 10.1126/science.1109020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science. 2004;303:83–86. doi: 10.1126/science.1091903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kloosterman WP, Plasterk RH. The diverse functions of microRNAs in animal development and disease. Dev Cell. 2006;11:441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Care A, Catalucci D, Felicetti F, Bonci D, Addario A, Gallo P, Bang ML, Segnalini P, Gu Y, Dalton ND, et al. MicroRNA-133 controls cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2007;13:613–618. doi: 10.1038/nm1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen JF, Mandel EM, Thomson JM, Wu Q, Callis TE, Hammond SM, Conlon FL, Wang DZ. The role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133 in skeletal muscle proliferation and differentiation. Nat Genet. 2006;38:228–233. doi: 10.1038/ng1725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44••.Yin VP, Thomson JM, Thummel R, Hyde DR, Hammond SM, Poss KD. Fgf-dependent depletion of microRNA-133 promotes appendage regeneration in zebrafish. Genes Dev. 2008;22:728–733. doi: 10.1101/gad.1641808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- This study is the first to explore the impact of miRNAs during appendage regeneration. The authors identify several miRNAs with different levels of expression in regenerating versus uninjured fins. miR-133 is identified as a miRNA that is normally depleted during regeneration, and by electroporation experiments has the properties of a regenerate brake. The study indicates a regulatory pathway in which Fgf signaling maintains low levels of miR-133 during regeneration, facilitating optimal blastemal proliferation through derepression of targets like the kinase Mps1.

- 45.Poss KD, Nechiporuk A, Hillam AM, Johnson SL, Keating MT. Mps1 defines a proximal blastemal proliferative compartment essential for zebrafish fin regeneration. Development. 2002;129:5141–5149. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.22.5141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ebert MS, Neilson JR, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: competitive inhibitors of small RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat Methods. 2007;4:721–726. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dinsmore C. A history of regeneration research. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumar A, Gates PB, Brockes JP. Positional identity of adult stem cells in salamander limb regeneration. C R Biol. 2007;330:485–490. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]