Abstract

A fundamental belief in the field of olfaction is that each olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) expresses only one odorant receptor (OR) type. Here we report that coexpression of multiple receptors in single neurons does occur at a low frequency. This was tested by double in situ hybridization in the septal organ in which greater than 90% of the sensory neurons express one of nine identified ORs. Notably, the coexpression frequency is nearly ten times higher in newborn than in young adult mice, suggesting a reduction of the sensory neurons with multiple ORs during postnatal development. In addition, such reduction is prevented by four-week sensory deprivation or impaired apoptosis. Furthermore, the high coexpression frequency is restored following four-week naris closure performed in young adult mice. The results indicate that activity induced by sensory inputs plays a role in ensuring the one cell-one receptor rule in a subset of olfactory sensory neurons.

Keywords: Odorant receptors, Naris closure, Septal organ, Olfactory epithelium, Sensory deprivation, Singular expression

Introduction

A key feature in the current models of smell perception is that a single olfactory sensory neuron (OSN) expresses only one odorant receptor (OR) type from a large family (>1000 in rodents). The underlying mechanism is under extensive investigation and likely involves several hierarchical steps from the initial OR selection to silencing other ORs (Fuss et al., 2007; Lomvardas et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2007). It has been reported that stabilizing an OR choice in individual neurons requires a negative feedback triggered by the receptor protein, especially encoded by a functional OR gene (Lewcock and Reed, 2004; Serizawa et al., 2003; Shykind et al., 2004). Here we hypothesize that the neuronal activity elicited by sensory stimulation plays a role in ensuring the one neuron-one receptor tenet. To test this hypothesis, we would need to reliably detect individual OSNs expressing multiple receptors with a measurable frequency. Such coexpression is rarely found in the main olfactory epithelium partly due to the vast number of odorant receptors expressed in any region (Mombaerts, 2004). In contrast, the mouse septal organ (a small patch of olfactory epithelium located at the ventral septum) expresses nine identified, intact OR genes in greater than 90% of the sensory neurons (Supplementary sFig. 1 and sTable 1) (Tian and Ma, 2008), thus providing a unique opportunity for detecting individual OSNs coexpressing multiple ORs.

Using double in situ hybridization based on various combinations of the nine receptor genes, we found that coexpression of odorant receptors in single neurons occurs at a low frequency. Interestingly, the chance for observing coexpression decreases nearly ten times from newborns to young adults. We then asked whether such decrement depends on sensory experience, because survival of individual OSNs depends on the neuronal activity (Watt et al., 2004; Yu et al., 2004; Zhao and Reed, 2001). We performed unilateral naris closure on the newborn mice, and the coexpression frequency observed four weeks later was significantly higher than the untreated mice at the same age. We next examined whether apoptosis (programmed cell death), which is essential in sculpting the olfactory epithelium during development (Cowan and Roskams, 2002), plays a role in the process of eliminating the OSNs with multiple ORs. In Bax (a proapoptotic protein) null mice, apoptosis is impaired in multiple tissues including the olfactory epithelium, in which the bulbectomy-induced apoptosis is prevented (Jourdan et al., 1998; Robinson et al., 2003). The chance of observing individual OSNs with multiple ORs stays high in adult Bax null mice. Furthermore, the sensory activity is also essential for maintaining the singular expression pattern in some OSNs, because a high coexpression frequency is restored following four-week naris closure performed in young adult mice. Taken together, the neuronal activity induced by sensory inputs plays a role in ensuring the singular expression pattern in the septal organ neurons.

Results

Coexpression of multiple ORs in single OSNs occurs at a low frequency

The mouse septal organ is a small patch of olfactory neuroepithelium, which predominantly expresses nine OR genes (MOR256-3, MOR244-3, MOR235-1, MOR0-2, MOR236-1, MOR256-17, MOR122-1, MOR160-5, and MOR267-16) in >90% of the sensory neurons (Supplementary sFig. 1 and sTable 1). These nine genes have intact, full-length coding sequences and are presumably functional (Zhang et al., 2004). Using mixed digoxigenin (DIG) and fluorescein (FLU)-labeled RNA probes in double in situ hybridization, we observed cotranscription of multiple OR genes in single septal organ neurons at a very low frequency (Fig. 1). Coexpression was initially identified by colocalization of red (from the DIG probes) and green (from the FLU probes) fluorescence in individual neurons from single optical planes (thickness=1 μm) of the confocal images (Fig. 1). Then a stack of z sections was obtained to confirm the colocalization in some cases (Supplementary sFig. 2).

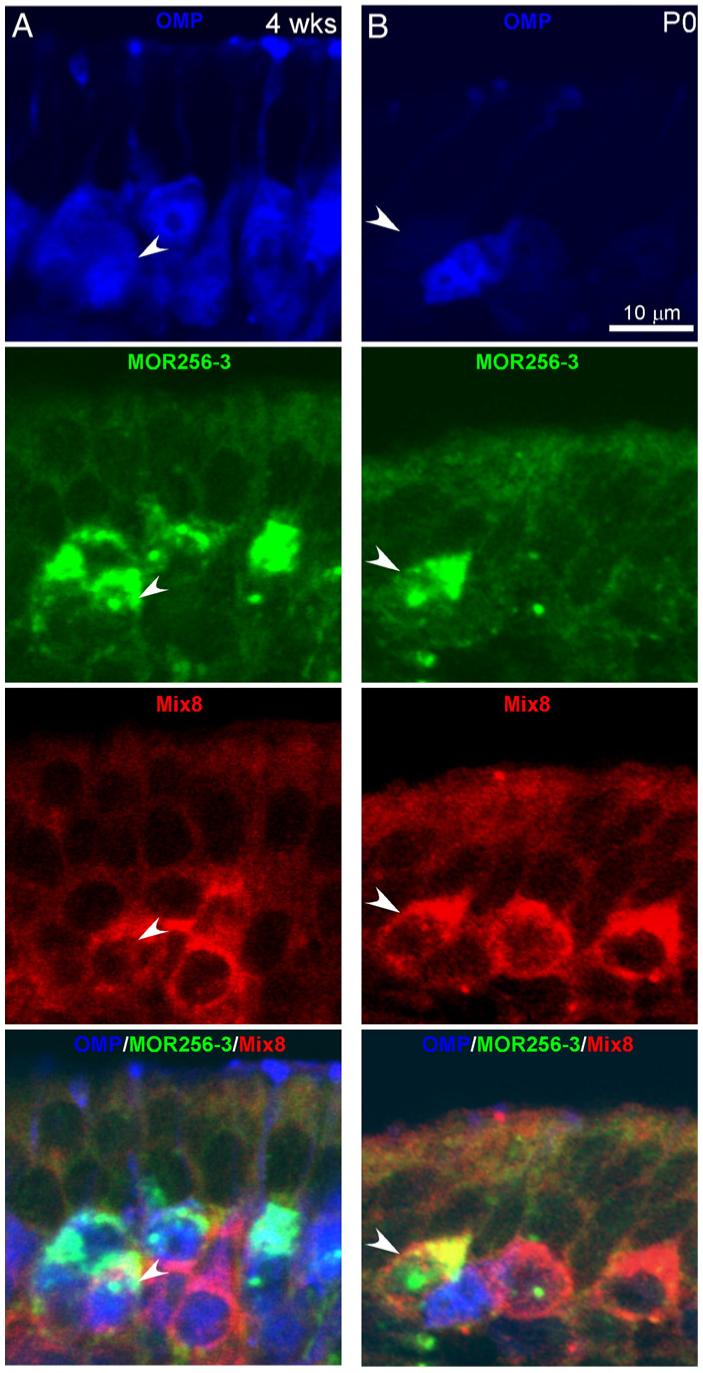

Fig. 1.

Coexpression of multiple odorant receptors in single neurons occurs at different frequencies in different stages. Coexpression of multiple odorant receptors in single neurons was detected by double in situ hybridization at four weeks (A) and P0 (B). The mature neurons were immunostained by the OMP antibody (blue). FLU-labeled MOR256-3 probe and DIG-labeled Mix8 probes (a mixture of eight OR probes: MOR244-3, 235-1, 0-2, 236-1, 256-17, 122-1, 160-5, and 267-16) generated green and red fluorescence, respectively. The arrowheads mark double-labeled single neurons. The confocal images are shown at a single optical plane with a thickness of 1 μm. A stack of images from (B) are displayed in Supplementary sFig. 2.

We observed cotranscription of multiple OR genes in single neurons in all probe combinations tested, including MOR 256-3 vs Mix8 (a mixture of the rest eight OR probes), MOR256-3 vs MOR236-1, MOR256-3 vs MOR244-3, Mix3 (MOR244-3, MOR235-1, and MOR0-2) vs Mix5 (MOR236-1, MOR256-17, MOR122-1, MOR160-5, and MOR267-16), and MOR244-3 vs MOR236-1. To facilitate quantification and comparison with the following experiments, we primarily focused on the probe combination of MOR256-3 vs Mix8, which labeled 51.9% and 48.3% of the total stained neurons in young adult animals, respectively (“4 and 8 wks, Untreated” in Table 1). We randomized the DIG and FLU probes in the experiments (FLU MOR256-3 vs DIG Mix8 and DIG MOR256-3 vs FLU Mix8) to reduce the potential bias generated by the labeling method. With this combination, cotranscription of MOR256-3 and at least another OR gene from Mix8 was found in 0.2% of the septal organ neurons in young adult mice (Table 1; more examples of colocalization are shown in Supplementary sFig. 3). Two time points (four and eight weeks) were chosen so that the data could be compared with those obtained after four-week naris closure (see below). In triple-labeling experiments combined with the OMP antibody, all double-labeled OSNs from adult tissues were mature neurons (Fig. 1A). The results indicate that coexpression of multiple receptors in single neurons does occur in adult olfactory epithelium, although at a low frequency.

Table 1.

Summary of the coexpression frequency (MOR256-3 vs Mix8) under different conditions

| Condition | Total cell number (percentage) | MOR256-3-labeled (percentage) | Mix8-labeled (percentage) | Double-labeled | Coexpression frequency | Section (animal) number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 and 8 wks, untreated | 10460 (100%) | 5435 (51.9%) | 5047 (48.3%) | 22 | 0.2%* | 90 (15) |

| P0, untreated | 1444 (100%) | 562 (38.9%) | 912 (63.1%) | 30 | 2.0% | 162 (27) |

| Sensory deprived (closed from P0 to 4 wks) | 2976 (100%) | 1507 (50.6%) | 1514 (50.9%) | 45 | 1.5% | 48 (8) |

| Sensory deprived (closed from 4 to 8 wks) | 2884 (100%) | 1212 (42.0%) | 1732 (60.0%) | 60 | 2.0% | 48 (8) |

| Bax-/-, 4 wks | 3404 (100%) | 1809 (53.1%) | 1649 (48.4%) | 54 | 1.6% | 17 (2) |

The “Coexpression Frequency” is the faction of the cells double-labeled by MOR256-3 and Mix8 probes in the total cells. The data from four and eight-week old mice are very similar and thus grouped together. The coexpression frequency in 4 and 8 weeks, untreated animals is significantly lower than the other four conditions (Chi-square test, p<0.0001, marked by*).

If the sensory activity indeed plays a role in ensuring the singular expression pattern in some OSNs as we proposed, we would expect that coexpression occurs at a higher frequency in early developmental stages when the OSNs have little olfactory experience and a higher chance of switching the receptor selection (Shykind et al., 2004). We examined the coexpression frequency in the septal organ from newborn mice (at postnatal day 0). At this stage, all nine receptors are expressed in the septal organ, but with relative contributions different than in adulthood due to asynchronous onsets and differential growth rates of OSNs expressing different ORs (Table 1 and Supplementary sTable 1). The OR positive neurons at P0 contained both mature (OMP-positive) and immature OSNs (OMP-negative) (Fig. 1B). Using the same probe combination (MOR256-3 vs Mix8), we observed that 2.0% of the OSNs (both mature and immature) expressing more than one receptor, a chance ten times higher than that in adulthood (Table 1). The results suggest that there is a reduction of the sensory neurons expressing multiple ORs during postnatal development.

Sensory deprivation maintains a high coexpression frequency in adult mice

To reveal the potential role that activity plays in ensuring the one cell-one receptor rule, we tested whether the MOR256-3/Mix8 coexpression frequency stays high in adult mice under the condition of sensory deprivation. We performed unilateral naris closure in newborn mice, a procedure that provides a complete sensory (both chemical and mechanical) deprivation in the closed nostril. When examined at the age of four weeks, the treatment led to a thinner olfactory epithelium in most regions primarily due to the reduction of immature OSNs (Figs. 2A-E), consistent with previous reports (Brunjes, 1994). This was revealed by double immunostaining with the OMP and the neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) antibodies. The mature OSNs were labeled by both OMP and NCAM, while the immature OSNs were labeled by NCAM only.

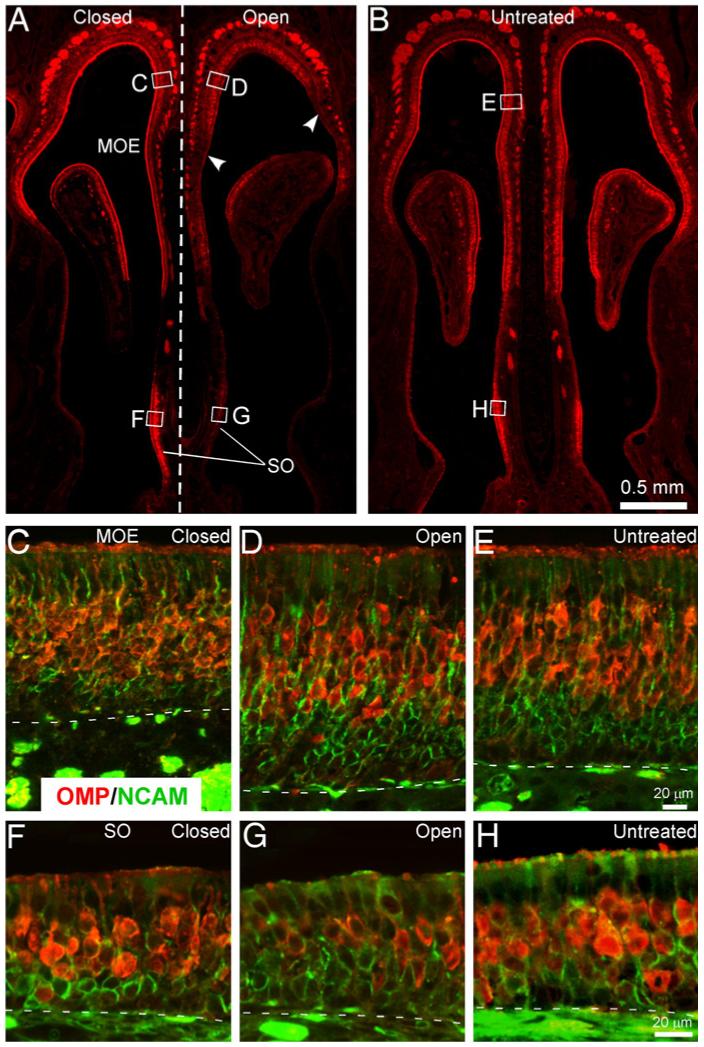

Fig. 2.

Neonatal naris closure causes morphological changes in the olfactory epithelium. (A, B) Unilateral naris closure was performed at P1 and a complete closure was confirmed four weeks later (Supplementary sFig. 2). The tissue sections were immunostained by OMP (red) and NCAM (green) antibodies. Coronal sections from operated (A) and untreated (B) animals are shown. Note thinner main olfactory epithelium (MOE) and stronger OMP staining in the closed side compared to the open side (A). The arrowheads in the open side mark patches of olfactory epithelium that lost the mature sensory neurons. The rectangles and corresponding letters (C-H) indicate the approximate locations where the following images were taken. (C-E) The MOE in the closed (C) and open (D) side of the operated mice was compared with the untreated animals (E). Note fewer layers of immature OSNs (in green) in the closed side (C). (F-H) The septal organ (SO) in the closed (F) and open (G) side of the operated mice was compared with the untreated animals (H). Note fewer OMP-positive neurons in G. The dotted lines mark the boundary between the olfactory epithelium and the lamina propria.

Notably, the olfactory epithelium in the open side also displayed significant alterations compared to the untreated control. In most areas of the main olfactory epithelium, there were more layers of immature OSNs in the open side reflecting the increased cell death and regeneration (Fig. 2D) (Cummings and Brunjes, 1994; Farbman et al., 1988). Another obvious change was the loss of OSNs in patches of the olfactory epithelium, especially in the anterior portion of the nostril (arrowheads in Fig. 2A). Theseptal organ was among the areas that lost most of the OMP-positive neurons, which resulted in a smaller and thinner section in the open side compared to either the closed side (8 out of 8 animals) or the untreated control (Figs. 2A, F-H). Due to the dramatic changes in the open side (see Discussion for potential causes), we used the untreated animals instead of the open side as the control for the closed side in our analysis. Double labeling by the same probe combination (MOR256-3 vs Mix8) revealed 1.5% of the neurons expressing multiple OR genes in the deprived side (Table 1). This percentage was significantly higher than that observed in the untreated, young adult mice, supporting a role of the sensory experience in ensuring that one neuron expresses only one receptor in some cells.

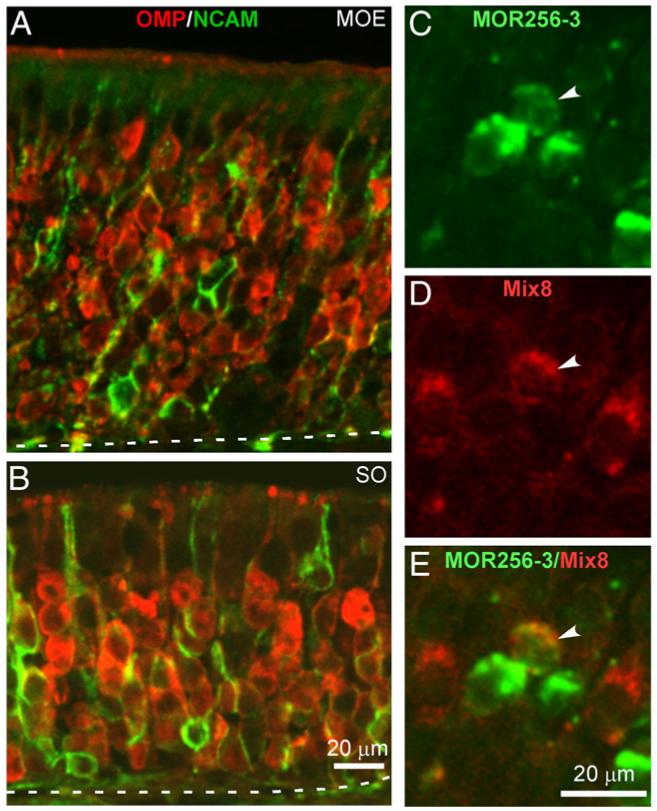

Several mechanisms may underlie the activity-dependent elimination of the sensory neurons with multiple ORs, and one possibility is that these neurons may undergo apoptosis during postnatal development. To directly test this possibility, we examined the coexpression frequency in Bax null mice with impaired apoptosis in multiple tissues including the olfactory epithelium. In both the main olfactory epithelium and the septal organ, double immunostaining with OMP and NCAM antibodies revealed more layers of mature OSNs, but a dramatic reduction of immature OSNs in Bax-/- mice, reflecting decreased cell death and regeneration (Figs. 3A,B). At the age of four weeks, the coexpression rate of MOR256-3vs Mix8 was 1.6% (Table 1), which was significantly higher than 0.2% in adult wild-type animals, supporting a role of apoptosis in eliminating the OSNs with multiple ORs.

Fig. 3.

The coexpression frequency stays high in Bax null mice at four weeks. (A, B) The olfactory epithelium in Bax null mice had more mature sensory neurons (OMP and NCAM positive, red) but fewer immature neurons (NCAM positive, green) in both the main olfactory epithelium (MOE) and the septal organ (SO) (c.f. the wild-type in Figs. 2E, H). The dotted lines mark the boundary between the olfactory epithelium and the lamina propria. (C-E) A single cell coexpressing MOR356-3 and at least another receptor from Mix8 was revealed by double in situ hybridization. The green signal was from FLU-labeled MOR256-3 probe and the red signal from DIG-labeled Mix8 probes. The arrows mark a double-labeled single neuron.

Maintenance of the one neuron-one receptor tenet could also require sensory inputs because OSNs undergo continuous regeneration (Graziadei and Monti Graziadei,1978). We next performed unilateral naris closure on four-week old mice, which had a low (0.2%) coexpression rate of MOR256-3 vs Mix8 (Table 1). After four-week naris closure, the colocalization frequency examined at the age of eight weeks using the same probe combination (MOR256-3 vs Mix8) increased nearly ten times to 2.0% (Table 1). We then used triple-labeling with the OMP antibody to confirm that the coexpressed OSNs were OMP-positive, mature neurons (12 out of 12 in 10 sections). These results support an essential role of the neuronal activity in stabilizing the receptor choice in a subset of septal organ neurons in adulthood.

Discussion

Using double in situ hybridization based on nine odorant receptors covering 90% of the sensory neurons, we have reexamined the one neuron-one receptor rule in the mouse septal organ. The results generally confirm this fundamental belief in the field, but also demonstrate that coexpression of multiple OR genes in single neurons can occur at a low frequency. The MOR256-3/Mix8 coexpression frequency is almost ten times higher in newborns or following four-week olfactory deprivation, revealing that the neuronal activity induced by sensory inputs plays a role in ensuring the one neuron-one receptor rule in some OSNs.

In the current study, we primarily quantified the coexpression frequency based on a single probe combination (MOR256-3 vs Mix8), which may lead to an underestimation for the following reasons. First, coexpression is not restricted to this combination. We observed colocalization from all probe combinations tested, suggesting that coexpression occurs randomly among these receptors. This is distinct from the previous reports in rat (Rawson et al., 2000), zebrafish (Sato et al., 2007), and Drosophila (Goldman et al., 2005), in which certain receptors are coexpressed in a subset of OSNs all the time or with a high tendency. Second, there are additional ORs (identified or unidentified) expressed in the septal organ (Kaluza et al., 2004; Tian and Ma, 2004). Third, detection of coexpression is essentially limited by the sensitivity of in situ hybridization, and individual RNA probes in a mixture may have different labeling efficiencies leading to an underestimation of colocalization. Therefore, the coexpression frequency reported here represents a conservative measurement.

Coexpression of multiple ORs in single neurons is likely to occur in the main olfactory epithelium as well since all the predominant septal organ receptors are also expressed in the most ventral zone (Tian and Ma, 2004). However, individual OSNs with multiple receptors are difficult to detect in the main epithelium using the same approach, because it requires many more receptor types to cover a significant portion of the sensory neurons. If the same coexpression frequency applies to the main olfactory epithelium, one may predict to observe one double-labeled cell out of ∼5000 neurons (adult tissues) when using combined probes that cover 10% of the neurons in any region (given the chance of 0.2% in the septal organ when covering 90% of the neurons). This may explain why coexpression is rarely detected in the main olfactory epithelium.

Based on the same probe combination, the chance for detecting coexpression is ten times higher in newborn mice. This may result from the higher frequency of receptor gene switching at early developmental stages (Shykind et al., 2004). Alternatively, this may represent expression “errors” occurring randomly (Mombaerts, 2004), which can be corrected during postnatal development. In either scenario, the postnatal reduction of the OSNs with multiple ORs appears to depend on the sensory experience, because sensory deprivation maintains a high coexpression rate until adulthood (Table 1). However, we cannot completely rule out that some activity-independent processes account for the instability of the double-labeled cells over time, and the frequency of observing these double-labeled cells decreases due to age-related reduction in proliferation (Weiler and Farbman, 1997).

One interesting finding in the naris-closure experiments is that the septal organ in the open side becomes much smaller with many fewer OMP-positive neurons than the untreated animals or the closed side. The loss of OSNs in the main olfactory epithelium especially in the anterior part is also evident (Fig. 2). This may be due to the fact that the open side now serves as the obligatory nasal breather, which has probably doubled the air flow (compared to the normal condition) and is deprived of the resting periods from physiological switching of the dominant breathing sides. This may cause additional traumas to the open side, which likely lead to an accelerated rate of cell death and a net loss of OSNs in areas with a limited capacity for regeneration, such as the septal organ (Weiler and Farbman, 2003). Recent studies on the transduction cascade and odor-induced responses also support a dramatic change in the open nostril compared to the untreated control as well as the closed side (Coppola et al., 2006; Waggener and Coppola, 2007). Consequently, we have compared the coexpression frequency in the deprived side to the untreated control in this study.

There are several complementary activity-dependent mechanisms that could eliminate the OSNs with multiple ORs. The first possibility is that single neurons with multiple functional receptors send different signals to the olfactory bulb than those with a single receptor, which may fail to stabilize their synapses and cause these neurons to die. Indeed, the olfactory epithelium in Bax null mice with impaired apoptotic pathways maintains a relatively high coexpression rate in adulthood (Fig. 3 and Table 1). Similar to the deprived side in the naris-closed animals, there is a significant reduction of the immature OSNs in Bax-/- mice, presumably due to a slower turnover rate when cell death is prevented. Knocking out Bax only partially blocks apoptosis in the olfactory epithelium by interrupting one of several pathways; therefore, we may have underestimated the role apoptosis plays in this process.

The second possibility is that one of the coexpressed odorant receptors, favorably stimulated by the olfactory cues, becomes dominant in that neuron by suppressing the others via a negative feedback mechanism (Lewcock and Reed, 2004; Serizawa et al., 2003; Shykind et al., 2004). The third possibility is that the OSNs maintain the capability to switch their receptor selection even in adulthood, and the switching only stops when the neuron is functionally activated and one selection is thus stabilized. Interestingly, sensory deprivation in young adult mice for four weeks restores the OSNs with multiple receptors in the olfactory epithelium to the same high level as in newborns. Because these neurons are mature OMP-positive neurons, it is unlikely that they are newly generated neurons following the naris closure. This result lends support to the second and/or third possibility, but further experiments will be required to distinguish them. In addition to the mechanisms proposed in OR gene selection and stabilization (Fuss et al., 2007; Lewcock and Reed, 2004; Lomvardas et al., 2006; Nguyen et al., 2007; Serizawa et al., 2003; Shykind et al., 2004), the current study reveals an activity-dependent mechanism in ensuring and maintaining that one cell expresses only receptor in a subset of sensory neurons.

Experimental methods

Animals

Wide-type C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the Charles River Laboratories and homozygous Bax-/- (B6.129X1-Baxtm1Sjk/J, stock number 002994) mice from the Jackson Laboratory. For unilateral naris closure, a brief cauterization (<1 s) using a cauterizer (Fine Science Tools) was performed on one nostril at postnatal day 1 (P1) or four weeks and the olfactory tissues were examined four weeks later. Only animals with a complete closure on the operated side were used for analysis. Mice were deeply anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine HCl and xylazine (300 mg/kg and 20 mg/kg body weight respectively) and decapitated. The heads were immediately put into 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma) overnight at 4 °C, and the adult tissues were subject to decalcification in 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) for two days. The nose was cut into 20 μm coronal sections on a cryostat. The procedures of animal handling and tissue harvesting were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee of the University of Pennsylvania.

Double in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry

Digoxigenin (DIG)- and fluorescein (FLU)-labeled RNA probes of the olfactory receptor genes were generated using DIG and FLU RNA Labeling Kit (SP6/T7) (Roche #11175025910 and #11685619910, Indianapolis, IN) as described previously (Ishii et al., 2004; Tian and Ma, 2004, 2008). The nine specific probes used here (the sequences are listed in Supplementary sTable 2) presumably only detect their target OR genes, because seven of them share less than 40% of nucleotide homology with any other OR in the genome, and the other two (MOR235-1 and MOR236-1 sharing 75% homology with each other) label different subsets of cells in double in situ hybridization (Tian and Ma, 2004). The tissue sections were hybridized with mixed FLU- and DIG-labeled probes overnight at 65 °C in the hybridization solution (50% deionized formamide, 10 mM Tris-Cl (pH 8.0), 10% dextran sulfate, 1X Denhardt’s solution, 200 μg/ml tRNA, 0.6 M NaCl, 0.25% SDS and 1 mM EDTA), followed by high-stringency washing steps sequentially in 2x, 0.2x and 0.1x SSC at 65 °C. The sections were then reacted with horse-radish peroxidase-conjugated anti-fluorescein (1:100, Roche #11426346910) and AP-anti-DIG (1:1000, Roche #11093274910) antibodies (1 1 h at RT) followed by incubation in Tyramide-biotin (1:50, 10 min at RT) (#NEL700A, New England Nuclear, PerkinElmer, Boston, MA) to amplify the peroxidase signal. The signals were visualized by Streptavidine-Alexa 488 (#S11223, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) (1:300, 30 min in the dark at RT) and Fast Red (2-Hydroxy-3-naphthoic acid-2′-phenyl-anilide phosphate (HNPP) Fluorescent Detection Set, Roche #11758888001) (1:100, 30 min in the dark at RT), respectively. In some experiments, two-color in situ hybridization was combined with immunohistochemistry to simultaneously detect the olfactory marker protein (OMP) by adding the goat anti-OMP antibody (1:500) (kindly provided by Dr. Frank Margolis, University of Maryland). The signal was visualized via Alexa Fluor 633 donkey anti-goat IgG (Invitrogen # A21082) (1:500, 30 min in the dark). More detailed procedures are described by Ishii et al. (2004). Additional antibodies used in immunohistochemistry included mouse anti-NCAM (1:200; Sigma), donkey-anti-mouse-488, and donkey-anti-goat-568 (both at 1:150, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by NIDCD/NIH (R01 DC006213) and Institute on Aging at the University of Pennsylvania (a pilot grant).

References

- Brunjes PC. Unilateral naris closure and olfactory system development. Brain Res. 1994;19:146–160. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(94)90007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coppola DM, Waguespack AM, Reems MR, Butman ML, Cherry JA. Naris occlusion alters transductory protein immunoreactivity in olfactory epithelium. Histol. Histopathol. 2006;21:487–501. doi: 10.14670/HH-21.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan CM, Roskams AJ. Apoptosis in the mature and developing olfactory neuroepithelium. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2002;58:204–215. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings DM, Brunjes PC. Changes in cell proliferation in the developing olfactory epithelium following neonatal unilateral naris occlusion. Exp. Neurol. 1994;128:124–128. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1994.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farbman AI, Brunjes PC, Rentfro L, Michas J, Ritz S. The effect of unilateral naris occlusion on cell dynamics in the developing rat olfactory epithelium. J. Neurosci. 1988;8:3290–3295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-09-03290.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuss SH, Omura M, Mombaerts P. Local and cis effects of the H element on expression of odorant receptor genes in mouse. Cell. 2007;130:373–384. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman AL, Van der Goes van Naters W, Lessing D, Warr CG, Carlson JR. Coexpression of two functional odor receptors in one neuron. Neuron. 2005;45:661–666. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graziadei PPC, Monti Graziadei GA. Continuous nerve cell renewal in the olfactory system. In: Jacobson M, editor. Development of sensory systems. Springer-Verlag; New York: 1978. pp. 55–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ishii T, Omura M, Mombaerts P. Protocols for two- and three-color fluorescent RNA in situ hybridization of the main and accessory olfactory epithelia in mouse. J. Neurocytol. 2004;33:657–669. doi: 10.1007/s11068-005-3334-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jourdan F, Moyse E, De Bilbao F, Dubois-Dauphin M. Olfactory neurons are protected from apoptosis in adult transgenic mice over-expressing the bcl-2 gene. NeuroReport. 1998;9:921–926. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199803300-00029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaluza JF, Gussing F, Bohm S, Breer H, Strotmann J. Olfactory receptors in the mouse septal organ. J. Neurosci. Res. 2004;76:442–452. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewcock JW, Reed RR. A feedback mechanism regulates monoallelic odorant receptor expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2004;101:1069–1074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307986100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomvardas S, Barnea G, Pisapia DJ, Mendelsohn M, Kirkland J, Axel R. Interchromosomal interactions and olfactory receptor choice. Cell. 2006;126:403–413. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P. Odorant receptor gene choice in olfactory sensory neurons: the one receptor-one neuron hypothesis revisited. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2004;14:31–36. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2004.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen MQ, Zhou Z, Marks CA, Ryba NJ, Belluscio L. Prominent roles for odorant receptor coding sequences in allelic exclusion. Cell. 2007;131:1009–1017. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.10.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rawson NE, Eberwine J, Dotson R, Jackson J, Ulrich P, Restrepo D. Expression of mRNAs encoding for two different olfactory receptors in a subset of olfactory receptor neurons. J. Neurochem. 2000;75:185–195. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson AM, Conley DB, Kern RC. Olfactory neurons in bax knockout mice are protected from bulbectomy-induced apoptosis. NeuroReport. 2003;14:1891–1894. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200310270-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Miyasaka N, Yoshihara Y. Hierarchical regulation of odorant receptor gene choice and subsequent axonal projection of olfactory sensory neurons in zebrafish. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:1606–1615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4218-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serizawa S, Miyamichi K, Nakatani H, Suzuki M, Saito M, Yoshihara Y, Sakano H. Negative feedback regulation ensures the one receptor-one olfactory neuron rule in mouse. Science. 2003;30:2088–2094. doi: 10.1126/science.1089122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shykind BM, Rohani SC, O’Donnell S, Nemes A, Mendelsohn M, Sun Y, Axel R, Barnea G. Gene switching and the stability of odorant receptor gene choice. Cell. 2004;117:801–815. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Ma M. Molecular organization of the olfactory septal organ. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:8383–8390. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2222-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian H, Ma M. Differential development of odorant receptor expression patterns in the olfactory epithelium: a quantitative analysis in the mouse septal organ. Dev. Neurobiol. 2008;68:476–486. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waggener CT, Coppola DM. Naris occlusion alters the electro-olfactogram: evidence for compensatory plasticity in the olfactory system. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;427:112–116. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watt WC, Sakano H, Lee ZY, Reusch JE, Trinh K, Storm DR. Odorant stimulation enhances survival of olfactory sensory neurons via MAPK and CREB. Neuron. 2004;41:955–967. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00075-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler E, Farbman AI. Proliferation in the rat olfactory epithelium: age-dependent changes. J. Neurosci. 1997;17:3610–3622. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03610.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiler E, Farbman AI. The septal organ of the rat during postnatal development. Chem. Senses. 2003;28:581–593. doi: 10.1093/chemse/bjg047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu CR, Power J, Barnea G, O’Donnell S, Brown HE, Osborne J, Axel R, Gogos JA. Spontaneous neural activity is required for the establishment and maintenance of the olfactory sensory map. Neuron. 2004;42:553–566. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Rodriguez I, Mombaerts P, Firestein S. Odorant and vomeronasal receptor genes in two mouse genome assemblies. Genomics. 2004;83:802–811. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2003.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H, Reed RR. X inactivation of the OCNC1 channel gene reveals a role for activity-dependent competition in the olfactory system. Cell. 2001;104:651–660. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00262-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.