Abstract

Relapse to drug use is a core feature of addiction. Previous studies demonstrate that γ-vinyl GABA (GVG), an irreversible GABA transaminase inhibitor, attenuates the acute rewarding effects of cocaine and other addictive drugs. We here report that systemic administration of GVG (25–300 mg/kg) dose-dependently inhibits cocaine- or sucrose-induced reinstatement of reward-seeking behavior in rats. In vivo microdialysis data indicated that the same doses of GVG dose-dependently elevate extracellular GABA levels in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). However, GVG, when administered systemically or locally into the NAc, failed to inhibit either basal or cocaine-priming enhanced NAc dopamine in either naïve rats or cocaine extinction rats. These data suggest that: (1) GVG significantly inhibits cocaine- or sucrose-triggered reinstatement of reward-seeking behavior; and (2) a GABAergic-, but not dopaminergic-, dependent mechanism may underlie the antagonism by GVG of cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior, at least with respect to GVG's action on the NAc.

Keywords: Cocaine, Dopamine, GABA, Gamma-vinyl GABA, Reinstatement, Relapse

1. Introduction

Relapse to drug use is one of the core features of addiction, and to date, no broadly effective medications exist. One strategy for developing effective pharmacotherapies for drug abuse and drug dependence is to understand the neurobiological mechanisms underlying drug craving and relapse, and to pharmacotherapeutically target those mechanisms (O'Brien and Gardner, 2005; Kalivas and Volkow, 2005). Substantial evidence indicates that increased dopamine (DA) transmission in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) appears to be critically involved in drug reward and relapse (Wise, 1998). For example, cocaine priming significantly elevates extracellular NAc DA (Neisewander et al., 1996; McFarland et al., 2003; Xi et al., 2006). Also, systemic or intra-NAc administration of direct or indirect DA receptor agonists elicit, while DA receptor antagonists block, cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (Self et al., 1996; De Vries et al., 2002; Vorel et al., 2002). In addition, repeated cocaine administration produces enduring alterations in basal DA transmission, DA response to cocaine priming and/or expression of DA receptors in reward-related brain regions (Kuhar and Pilotte, 1996; Lu et al., 2003; Staley and Mash, 1996). These data suggest that DA-related mechanisms play an important role in drug craving and relapse (Shalev et al., 2002; Anderson and Pierce, 2005). In addition to DA, growing evidence indicates that glutamate-related mechanisms are also critically involved in cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (see review by Kalivas, 2004).

γ-Aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain and exerts inhibitory control over DA and glutamate release in the NAc (Xi et al., 2003). γ-Vinyl GABA (GVG) is an anticonvulsant that elevates brain GABA levels by irreversibly inhibiting GABA transaminase, the enzyme responsible for GABA's metabolic degradation (Cubells et al., 1986). Systemic administration of GVG in rats has been reported to significantly inhibit cocaine self-administration (Kushner et al., 1999), cocaine-induced conditioned place preference (Dewey et al., 1998), cocaine-induced enhancement of electrical brain stimulation reward (Kushner et al., 1997), and cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA (Dewey et al., 1997; Morgan and Dewey, 1998; Schiffer et al., 2000). However, the effect of GVG on cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior has remained unexplored. In the present study, we examined the effects of GVG on cocaine- or sucrose-induced reinstatement of reward-seeking behavior in male Long-Evans rats. Further, we examined the effects of GVG pretreatment on basal and cocaine-induced changes in extracellular GABA and DA in the NAc using in vivo brain microdialysis.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Male Long-Evans rats (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC, n = 130) weighing 250–300 g were used for all experiments. They were housed individually in a climate-controlled animal colony room on a reversed light-dark cycle (lights on at 7:00 p.m., lights off at 7:00 a.m.) with free access to food and water. The animals were maintained in a facility fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC International). All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC: National Academy Press, 1996) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

2.2. Drugs and chemicals

Cocaine HCl (Sigma/RBI, Saint Louis, MO) was dissolved in physiological saline. GVG (vigabatrin, Sabril®) in racemic crystalline form was obtained from Aventis Pharma Inc. (Laval, QC, Canada). GVG was dissolved in 25% (w/v) 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma/RBI, Saint Louis, MO) for i.p. injections. For local intra-NAc perfusion, GVG was dissolved in the dialysis buffer described below.

2.3. Cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior

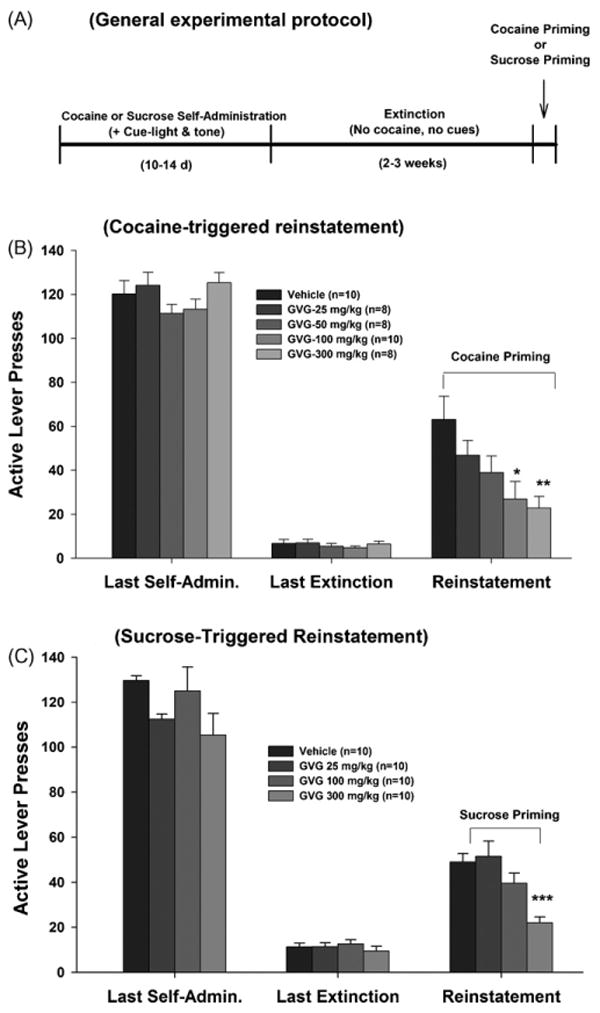

The cocaine self-administration and reinstatement experiments were carried out as we have previously described (e.g., Xi et al., 2006). Fig. 1A depicts the general experimental protocol followed.

Fig. 1.

General experimental protocol and effects of GVG on cocaine- or sucrose-triggered reinstatement of reward-seeking behavior. Panel A: general experiment protocol showing sequential experimental phases. Panel B: mean numbers of active lever presses during last session of cocaine self-administration, last session of extinction, and cocaine-primed reinstatement in presence of vehicle or various GVG doses. Panel C: mean numbers of active lever presses during last session of sucrose self-administration, last session of extinction, and sucrose-induced reinstatement in presence of vehicle or various GVG doses. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared to vehicle treatment group.

2.3.1. Surgery

Intravenous (i.v.) jugular catheterization was carried out using standard aseptic surgical technique. The i.v. catheters were constructed of microrenathane (Braintree Scientific Inc., Braintree, MA). Rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (65 mg/kg i.p.) and then the skin over the right external jugular was incised, the jugular vein exposed by blunt dissection and incised, and the catheter inserted into the vein and sutured into place. The portion of catheter outside the jugular was then passed subcutaneously to the top of the skull, where it exited into a connector (a modified 22 gauge cannula; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) mounted to the skull with stainless steel skull screws (Small Parts Inc., Miami Lakes, FL) and cranioplastic acrylic (Codman and Shurtleff, Raynham, MA). During experimental sessions, the catheter was connected to the infusion pump via tubing encased in a protective metal spring from the head-mounted connector to the top of the experimental chamber. To help prevent clogging, catheters were flushed daily with a gentamicin–heparin–saline solution (30 IU/ml heparin; ICN Biochemicals, Cleveland, OH).

2.3.2. Apparatus

The i.v. cocaine self-administration experiments were conducted in standard operant test chambers (32 cm × 25 cm × 33 cm) (Med Associates Inc., Saint Albans, VT). Each test chamber had two levers, located 6.5 cm above the floor. Depression of one lever activated an infusion pump; depression of another lever was counted but had no consequence. A cue light and speaker were located 12 cm above the active lever. A house light was turned on at the start of each 3 h test session. When an animal pressed a lever that resulted in a drug infusion, 2 drug-paired conditioned cues (cue light and cue sound/tone) were automatically activated and remained on for the duration of the infusion. Scheduling of experimental events and data collection was accomplished using Med Associates software (Med-PC IV).

2.3.3. Cocaine self-administration under a fixed-ratio 2 (FR2) schedule of reinforcement

After 5–7 days of recovery from surgery, each rat was placed into a test chamber and allowed to lever-press for i.v. cocaine (1 mg/kg/injection) delivered in 0.08 ml over 4.6 s, on a FR1 schedule of reinforcement. During the 4.6 s necessary for infusion, responses on the active lever were recorded but did not lead to additional infusions. Each session lasted 3 h. Subjects responded under the FR1 schedule for 3–5 days until stable cocaine self-administration was established. Then, the subjects were transferred to cocaine self-administration (0.5 mg/kg/injection) under a FR2 reinforcement schedule until the following criteria for stable cocaine-maintained responding were met: less than 10% variability in inter-response interval and less than 10% variability in number of active lever-presses for at least 3 consecutive days. The unit cocaine dose was lowered from 1.0 mg/kg/infusion to 0.5 mg/kg/infusion in order to increase the work demand (i.e., lever presses) on the animals for the same amount of drug intake, which in our experience significantly increases the sensitivity of measuring changes in drug-taking or drug-seeking behavior. To avoid cocaine-induced seizures, each animal was limited to 50 cocaine infusions per session.

2.3.4. Extinction and testing for reinstatement

After stable cocaine self-administration was established, animals were exposed to extinction conditions, during which cocaine was replaced by saline, and the cocaine-associated cue light and tone were turned off. Daily 3 h extinction sessions for each rat continued until that rat lever-pressed less than 10 times per 3 h session for at least 3 consecutive days. After meeting extinction criteria, animals were divided into 5 groups (8–10 rats per group) for reinstatement testing. On the reinstatement test day, each rat received either vehicle (25% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin) or 1 dose of GVG (25, 50, 100, and 300 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 h before the reinstatement test. All rats were then given a priming injection of cocaine (10 mg/kg i.p.) immediately before the initiation of reinstatement testing. During reinstatement testing, conditions were identical to those in extinction sessions. Cocaine-induced lever presses (reinstatement) were recorded, although these responses did not lead to either cocaine infusions or presentation of the conditioned cues. Reinstatement test sessions lasted 3 h.

2.3.5. Sucrose-triggered reinstatement of sucrose-seeking behavior

The procedures for oral sucrose self-administration, extinction, and reinstatement testing were identical to the procedures for cocaine self-administration, extinction, and reinstatement testing except for the following: (1) no surgery was performed on the animals in the sucrose experiment; (2) active lever presses led to delivery of 0.1 ml of 5% sucrose solution into a liquid food tray on the operant chamber wall; and (3) reinstatement was triggered initially by 2 “free” sucrose deliveries, and subsequent lever presses did not lead to either sucrose infusion or the presentation of the conditioned cue-light and tone.

2.4. In vivo microdialysis

2.4.1. Surgery and microdialysis probes

There were two groups of animals, i.e. drug naïve and cocaine-treated animals, used for in vivo microdialysis studies. The cocaine-treated animals had the same cocaine self-administration and extinction training as described above, and then the microdialysis experiment was performed during the reinstatement test. For those rats, both i.v. catheterization and intracranial guide cannula (20 gauge, 14 mm length; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) implantation were performed at time of surgery, while for the drug naïve rats, only intracranial guide cannula implantation was performed. Anesthesia was as described above. The target implant coordinates for the NAc guide cannulae were +1.6 mm anterior to Bregma, ±1.6 mm mediolateral, and −4.7 mm ventral to the skull surface, according to the rat brain atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1998), using a surgical approach of 6° from vertical. The guide cannulae were fixed to the skull with 4 stainless steel skull screws (Small Parts Inc., Miami Lakes, FL) and cranioplastic acrylic (Codman and Shurtleff, Raynham, MA). Microdialysis probes were constructed as previously described (Xi et al., 2003). The active operational length of the semipermeable microdialysis membrane was 1.0–1.5 mm, and probe diameter was approximately 100 μm. After animals had recovered from surgery for 5–7 days, we then examined the effect of GVG pretreatment on basal levels of, and cocaine-induced changes in, extracellular NAc DA and GABA.

2.4.2. Microdialysis procedure

Microdialysis probes were inserted into the NAc at least 12 h before onset of experimentation to minimize the effects of damage-induced neurochemical release during the experiment. Then, microdialysis buffer (5 mM glucose, 2.5 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 0.15% phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4) was perfused via syringe pump (Bioanalytical Systems, Inc., West Lafayette, IN) through the probes at 2.0 μl/min for at least 2 h prior to sample collection. Microdialysis samples were collected every 20 min into 10 μl 0.5 M perchloric acid to prevent degradation of the collected chemicals. After 1 h of baseline sample collection, 1 of 3 doses of GVG (25, 100, and 300 mg/kg, i.p.) or vehicle (1 ml 25% 2-hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin) was administered systemically, or different concentrations of GVG (1, 10, 100, and 1000 μM) were locally infused into the NAc by reverse microdialysis. To evaluate the effects of GVG pretreatment on cocaine-induced changes in NAc DA, cocaine (10 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 1, 3 or 6 h after systemic GVG administration. After collection, all samples were frozen at −80 °C until analyzed.

2.4.3. Quantification of GABA

Concentrations of GABA in the microdialysis samples were determined using HPLC with flourometric detection. The mobile phase consisted of 18% acetylnitrile (v/v), 100 mM Na2HPO4, and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 6.04. A VeloSep RP-18, 10 cm × 3 μm ODS reversed phase column (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Inc., Wellesley, MA) was used to separate the amino acids, and precolumn derivatization of amino acids with o-phthalaldehyde was performed using an ESA Biosciences model 542 autosampler. GABA was detected by an ESA Biosciences Linear Fluor LC 305 fluorescence spectrophotometer. Excitation (Exλ) and emission (Emλ) wavelengths were 336 nm and 420 nm, respectively. The area under the curve (AUC) of the GABA peak was measured using the EZChrom Elite™ chromatography data analysis system (ESA Biosciences, Inc., Chelmsford, MA). GABA values were quantified with an external standard curve. The limit of detection for GABA was 0.1–1 pM.

2.4.4. Quantification of DA

Microdialysate DA was measured using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with electrochemical detection (ESA Biosciences Inc.). The DA mobile phase contained 4.76 mM citric acid, 150 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM EDTA, 10% methanol, and 15% acetylnitrile, pH 5.6. DA was separated using an ESA Biosciences MD-150 × 3.2 mm reversed phase column, and was oxidized/reduced using an ESA Biosciences Coulochem® III electrochemical detector. Three electrodes were used: a preinjection port guard cell (+0.25 V) to oxidize the mobile phase, an oxidation analytical electrode (E1, −0.1 V), and a reduction analytical electrode (E2, 0.2 V). The AUC of the DA peak was measured using the EZChrom Elite™ chromatography data analysis system (ESA Biosciences, Inc.). DA values were quantified with an external standard curve (1–1000 fM).

2.4.5. Neuroanatomical verification of microdialysis probe sites

Following the microdialysis experiments, rats were given an overdose of pentobarbital (>100 mg/kg i.p.) and transcardially perfused with 0.9% saline followed by 10% formalin solution. Brains were removed and placed in 10% formalin for at least 1 week to ensure thorough fixation. The tissue was blocked around the NAc and coronal sections (100 μm thick) were made by vibratome through the area of microdialysis probe implantation. The brain sections were then stained with cresyl violet. Anatomical placement was verified by visual microscopic examination.

2.5. Data analyses

All data are presented as means ± S.E.M. AUC measurement was used for comparison of overall effects of GVG treatment on basal levels of, or cocaine-induced changes in, extracellular DA or GABA. The AUC% was calculated for each animal by subtracting 100 from the percent of baseline value for each data point, and subsequently summing all data points collected after drug administration. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyze the effects of GVG on cocaine-induced reinstatement (Fig. 1B and C). Two-way (treatment × time) ANOVA with repeated measures on 1 factor (time) was used to analyze the data reflecting the time courses of neurochemical changes after different doses of GVG and/or cocaine (Figs. 2–4). Post-ANOVA individual pre-planned group comparisons were carried out using the Bonferroni statistical procedure.

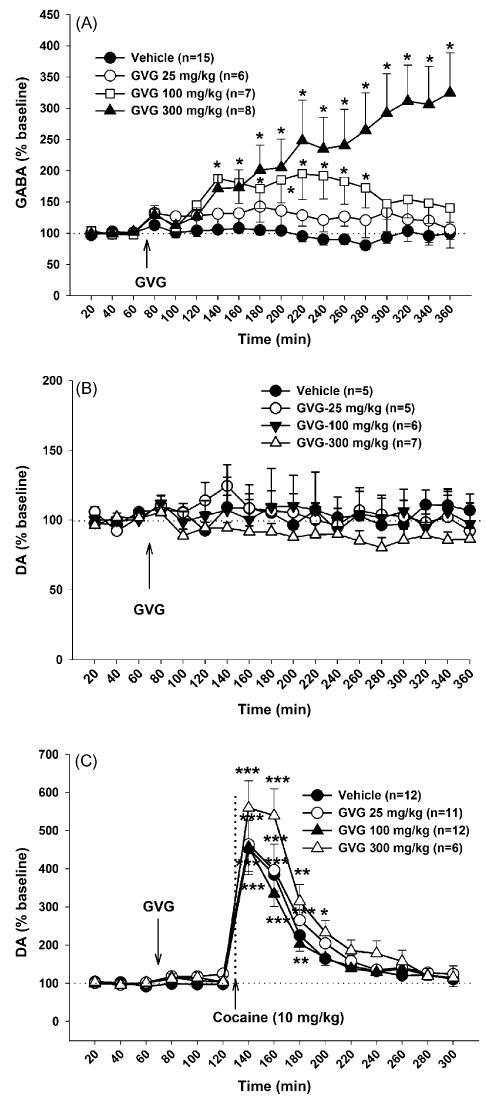

Fig. 2.

Effects of systemic administration of GVG on extracellular GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA in the NAc in cocaine extinction rats during reinstatement testing. Panel A: effects of GVG (25–300 mg/kg, i.p.) on NAc extracellular GABA. Panel B: effects of GVG on NAc extracellular DA. Panel C: effects of GVG pretreatment (25–300 mg/kg, i.p., 1 h prior to cocaine priming) on cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared to baseline before GVG administration in each GVG dose group.

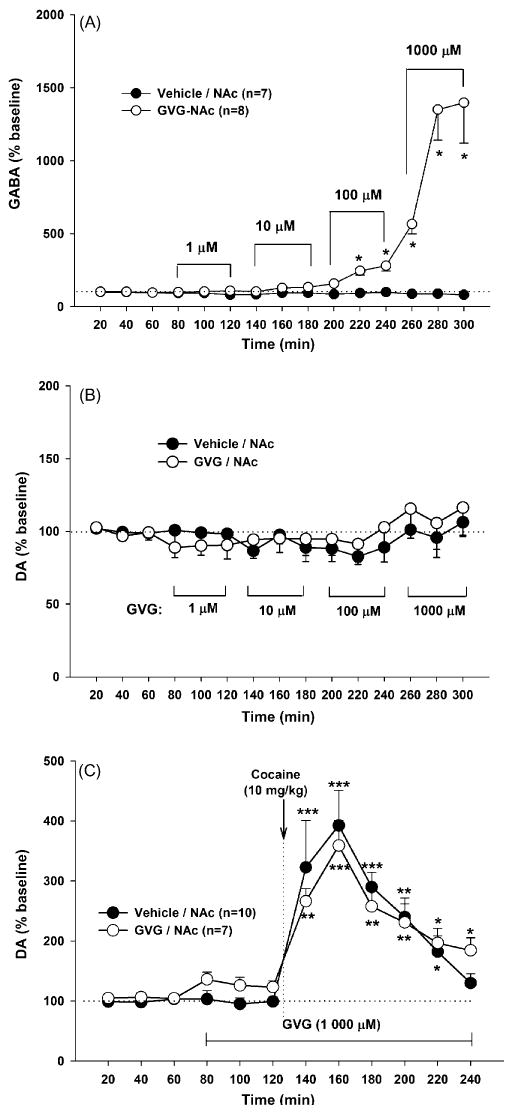

Fig. 4.

Effects of local perfusion of GVG into the NAc on NAc extracellular GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA in drug naïve rats. Panel A: effects of GVG (1–1000 μM) on extracellular GABA. Panel B: effects of the same concentrations of GVG on NAc extracellular DA. Panel C: effects of local perfusion of GVG (1000 μM) into the NAc on cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared to baseline before GVG administration in each group.

3. Results

3.1. Effects of GVG on cocaine- or sucrose-triggered reinstatement of reward seeking

3.1.1. Cocaine self-administration

Fig. 1B shows the mean numbers of active lever presses during the last session of cocaine self-administration, last session of extinction, and reinstatement testing in the presence of vehicle or 1 of the 4 GVG doses. Rats in all 5 groups exhibited stable responding on the active lever during the last 5–7 self-administration days with a within-subject variability of <10% in daily cocaine infusions. There were no significant differences in the mean numbers of cocaine infusions or active lever presses among different groups of rats during the last 3 sessions of cocaine self-administration (data not shown). Responding on the inactive lever was minimal in all groups of rats. There were no significant differences in responding on the inactive lever during self-administration among different groups (data not shown).

3.1.2. Extinction

As noted above, cocaine and cocaine-associated cues were unavailable during the extinction phase. As extinction progressed (2–3 weeks), the number of drug-seeking responses gradually decreased until the extinction criterion (<10 lever presses per 3 h) was met. There were no differences in the number of extinction responses among the different groups on the last extinction session, 24 h prior to reinstatement testing (F4,39 = 0.44, p > 0.05).

3.1.3. Reinstatement

Reinstatement testing began 24 h after the last extinction session, under extinction conditions (i.e., lever presses did not produce either cocaine infusions or the presentation of the cocaine-associated cues). As indicated in Fig. 1B, a single noncontingent cocaine injection (10 mg/kg i.p.) produced robust reinstatement of extinguished operant behavior previously reinforced by i.v. cocaine self-administration. Pretreatment with GVG (25, 50, 100 and 300 mg/kg i.p., 1 h prior to reinstatement testing) dose-dependently inhibited cocaine-induced reinstatement by 26, 44, 57, and 64%, respectively (Fig. 1B, right panel: F4,39 = 4.35, p < 0.01). Individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed a statistically significant decrease in cocaine-induced responding after 100 mg/kg (t = 3.39, p < 0.05) and 300 mg/kg (t = 3.55, p < 0.01), but not after 25 mg/kg (t = 1.43, p > 0.05) or 50 mg/kg (t = 2.46, p > 0.05) GVG.

Fig. 1C shows that GVG, at 300 mg/kg, but not at other doses tested, significantly inhibited the reinstatement of responding previously reinforced by sucrose. One-way ANOVA for the data shown in Fig. 1C showed a statistically significant effect of GVG on sucrose-triggered reinstatement of sucrose-seeking behavior (F3,27 = 10.38, p < 0.001). Individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed a statistically significant inhibition of sucrose seeking only after 300 mg/kg (t = 4.6, p < 0.001), but not 100 mg/kg (t = 1.6, p > 0.05) or 25 mg/kg (t = 0.43, p > 0.05) of GVG administration.

3.2. Effects of systemic administration of GVG on NAc GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA in cocaine extinction rats during reinstatement testing

3.2.1. Effects of GVG on GABA

To determine whether the antagonism by GVG of cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug seeking is correlated with GVG-induced alterations in NAc GABA or DA levels, we further observed the effects of GVG alone or pretreatment on extracellular GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA in rats during the reinstatement test. Fig. 2A shows that GVG dose-dependently elevated NAc extracellular GABA levels. A two-way ANOVA for repeated measures over time for the data shown in Fig. 2A revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F3,31 = 10.09, p < 0.001), time main effect (F17,527 = 8.46, p < 0.001), and treatment × time interaction (F51,527 = 5.71, p < 0.001). Individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed a statistically significant increase in extracellular GABA levels after 100 mg/kg (t = 2.65, p < 0.05) and 300 mg/kg GVG (t = 5.06, p < 0.001), but not after 25 mg/kg GVG (t = 1.18, p > 0.05).

3.2.2. Effects of GVG on NAc DA

Fig. 2B shows the effects of GVG alone on NAc DA in rats during reinstatement testing. Surprisingly, the same doses of GVG that altered NAc GABA failed to alter NAc extracellular DA. Two-way ANOVA for repeated measures over time for the data shown in Fig. 2B revealed a non-significant treatment main effect (F3,36 = 1.17, p > 0.05), time main effect (F17,388 = 0.65, p > 0.05), and treatment × time interaction (F36,422 = 1.19, p > 0.05).

3.2.3. Effects of GVG on cocaine-enhanced DA

Fig. 2C shows the effects of GVG on cocaine-enhanced DA in rats during reinstatement test. Pretreatment with the same doses of GVG that altered NAc GABA (25, 100, 300 mg/kg, i.p., 1 h prior to cocaine priming) did not inhibit cocaine priming-induced increases in DA (Fig. 2C). A two-way ANOVA for repeated measures over time revealed a statistically significant time main effect (F14,518 = 106.35, p < 0.001), but no significant treatment main effect (F3,37 = 1.68, p > 0.05) nor treatment × time interaction (F42,518 = 1.10, p > 0.05).

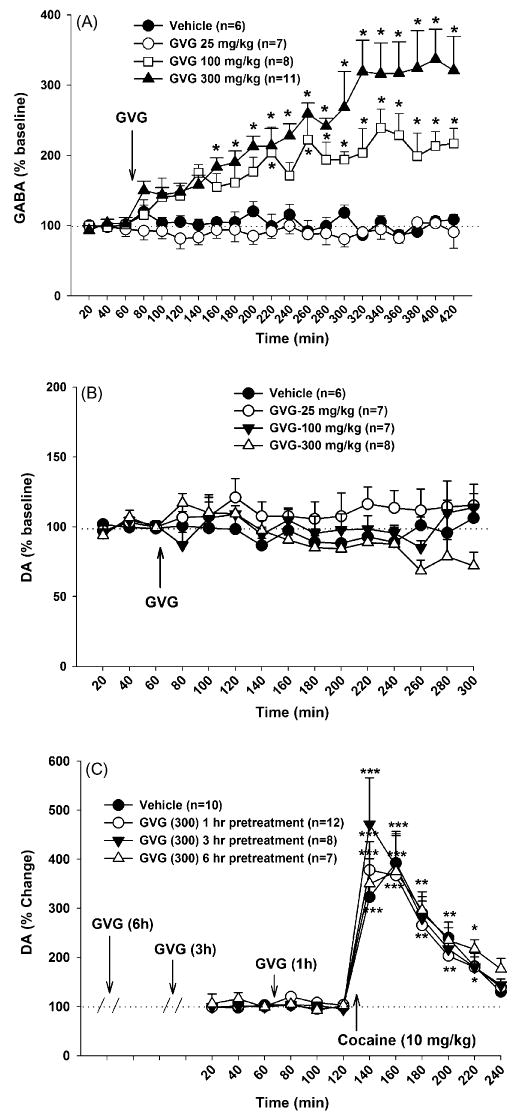

3.3. Effects of systemic administration of GVG on NAc GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA in drug naïve rats

The above lack of significant effect of GVG on cocaine-enhanced NAc DA levels appears to conflict with previous reports of GVG's effects in drug naïve rats (Dewey et al., 1997; Morgan and Dewey, 1998; Schiffer et al., 2000). Therefore, we further observed the effects of GVG (25–300 mg/kg, i.p., 1, 3 or 6 h prior to cocaine administration) on cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA in drug-naïve rats.

3.3.1. Effects of GVG on NAc GABA

Fig. 3A shows that systemic administration of GVG alone (25, 100, and 300 mg/kg i.p.) dose-dependently elevated extracellular NAc GABA levels in drug naïve rats. A two-way ANOVA for repeated measures over time for the data shown in Fig. 3A revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F3,28 = 18.22, p < 0.001), time main effect (F20,560 = 9.24, p < 0.001), and treatment × time interaction (F60,560 = 4.81, p < 0.001). Individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed a statistically significant increase in NAc GABA after 100 mg/kg (t = 3.17, p < 0.05) and 300 mg/kg GVG (t = 5.59, p < 0.001), but not after 25 mg/kg GVG (t = 0.49, p > 0.05).

Fig. 3.

Effects of systemic administration of GVG on extracellular GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA in the NAc of drug naïve rats. Panel A: effects of GVG (25–300 mg/kg, i.p.) on NAc extracellular GABA. Panel B: effects of GVG on NAc extracellular DA. Panel C: effects of GVG pretreatment (300 mg/kg, i.p., 1, 3 or 6 h prior to cocaine priming) on cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, compared to baseline before GVG administration in each GVG dose group.

3.3.2. Effects of GVG on NAc DA

To determine whether such an increase in NAc GABA by GVG inhibits NAc DA release in naïve rats, we measured DA levels in the same microdialysis samples. As in the cocaine-experienced rats, GVG (25–300 mg/kg) alone did not alter basal levels of extracellular DA in the NAc (Fig. 3B). Although two-way ANOVA for the data shown in Fig. 2B revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F2,24 = 3.29, p < 0.05), individual group comparisons did not reveal a statistically significant difference in extracellular DA levels between the vehicle and any dose of GVG tested, except for a statistically significant difference between the 25 and 300 mg/kg GVG treatment groups (t = 3.37, p < 0.05).

3.3.3. Effects of GVG on cocaine-enhanced DA

Fig. 3C shows that cocaine priming (10 mg/kg i.p.) produced a significant increase (∼400% of baseline) in NAc extracellular DA. Pretreatment with GVG (300 mg/kg, i.p. administered 1, 3 or 6 h prior to cocaine priming) had no effect on such cocaine priming-induced increases in DA (Fig. 3C). A two-way ANOVA for repeated measures over time revealed a statistically significant time main effect (F11,363 = 49.63, p < 0.001), but no significant treatment main effect (F3,33 = 0.08, p > 0.05) nor treatment × time interaction (F33,363 = 0.51, p > 0.05).

3.4. Effects of local perfusion of GVG into the NAc on extracellular GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA in drug naïve rats

To determine whether such lack of effect of GVG on cocaine-enhanced NAc DA was due to an interaction of both a direct action in the NAc and an indirect action in other brain regions, or difficulty of GVG penetrating to the NAc, we further observed the effects of local perfusion of GVG into the NAc on NAc GABA, DA and cocaine-enhanced DA. Fig. 4A shows that local perfusion of GVG (1 μM–1 mM) into the NAc significantly elevated extracellular GABA levels in a concentration-dependent manner. A two-way ANOVA for repeated measures over time revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F1,17 = 15.20, p < 0.001), time main effect (F14,238 = 12.97, p < 0.001), and treatment × time interaction (F14,238 = 12.65, p < 0.001). Consistent with the findings reported above after systemic GVG administration, local infusion of GVG (1 μM to 1 mM) into the NAc failed to alter basal levels of extracellular NAc DA (F1,18 = 0.05, p > 0.05) (Fig. 4B). Further, local continuous perfusion of GVG (1 mM) into the NAc also failed to inhibit cocaine-induced increases in extracellular NAc DA (F1,12 = 0.10, p > 0.05) (Fig. 4C).

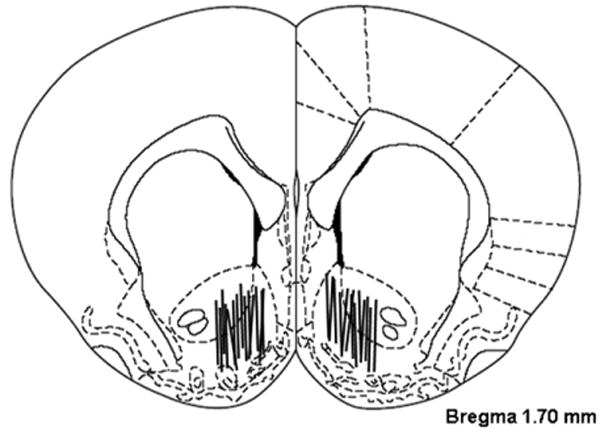

3.5. Histology

The locations of the microdialysis probes in the NAc are shown in Fig. 5. The active semi-permeable membranes of the microdialysis probes were located within both the NAc core and shell. There were no obvious differences in placement of microdialysis probes across the different experimental groups of rats.

Fig. 5.

Microdialysis probe placements within the NAc. The extent of each active semipermeable microdialysis membrane is depicted.

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrates that systemic administration of GVG (25–300 mg/kg) dose-dependently inhibited cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. In addition, the highest dose (300 mg/kg) of GVG also inhibited reinstatement of responding previously reinforced by sucrose. This finding is consistent with but extends previous findings that GVG inhibits cocaine's acute rewarding effects as assessed by electrical brain-stimulation reward, conditioned place preference, and drug self-administration (e.g., Kushner et al., 1997, 1999; Dewey et al., 1998). Further, the present in vivo microdialysis studies demonstrate that systemic administration of GVG dose-dependently elevated extracellular GABA levels, and had no effect on either basal or cocaine-enhanced DA in the NAc in drug naïve or cocaine-experienced rats. Finally, local perfusion of GVG into the NAc also dose-dependently elevated NAc extracellular GABA levels, but had no effect on either basal levels of DA or cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA. These data suggest that a GABA-, but not a DA-, dependent mechanism may underlie the antagonism by GVG of cocaine-primed reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior.

4.1. GVG inhibits cocaine- and sucrose-triggered reinstatement

The present experiments found that GVG significantly inhibited cocaine-triggered reinstatement at 100–300 mg/kg GVG, and also inhibited sucrose-triggered reinstatement at the highest dose of GVG (300 mg/kg), suggesting that GVG has a relatively selective action on cocaine's action at lower doses. This is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that the lowest effective doses (300–320 mg/kg) for inhibiting operant responding reinforced by food are higher than the lowest effective doses (180–200 mg/kg) for inhibiting cocaine self-administration (Kushner et al., 1999; Barrett et al., 2005). It was reported that GVG alone (180–320 mg/kg) appears to dose-dependently lower operant responding rates in the drug discrimination paradigm (Barrett et al., 2005). However, the same doses of GVG did not alter the discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine (Barrett et al., 2005), and an even higher GVG dose (400 mg/kg) failed to alter operant responding for food under progressive-ratio reinforcement (Kushner et al., 1999). These data suggest that a reduction in responding for cocaine/food or in reinstatement of cocaine/food-seeking behaviors is likely due to a specific action on reward and/or reinstatement mechanisms, rather than a nonspecific inhibition of locomotion or a deficit in motoric ability. This conclusion is further supported by evidence that GVG has no effect on locomotor activity at the doses (75–150 mg/kg) that produced a significant reduction in cocaine-triggered reinstatement in the present study (Gardner et al., 2002).

4.2. Non-DA mechanisms underlying GVG-induced inhibition of drug-seeking behavior

The present findings also suggest that the antagonism by GVG of cocaine-triggered reinstatement appears to be NAc DA-independent. It is well documented that NAc GABAergic neurons receive both DA input from the VTA and glutamatergic input from the frontal cortex (Sesack and Pickel, 1992). Given the important role of NAc DA (and glutamate) in cocaine-triggered relapse to drug-seeking behavior (Shalev et al., 2002; Anderson and Pierce, 2005; Kalivas, 2004), we initially hypothesized that GVG-induced increases in extracellular GABA levels might inhibit cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA (and glutamate), thereby inhibiting cocaine-induced reinstatement. However, the present data do not support that hypothesis: (1) a wide dose range of GVG, whether administered systemically (25–300 mg/kg, 1, 3 or 6 h prior to cocaine) or locally (1, 10, 100 and 1000 μM) into the NAc, altered neither basal levels of extracellular DA nor cocaine-induced increases in NAc extracellular DA in either cocaine-treated rats (during reinstatement testing) or in drug naïve rats; and (2) the same doses of GVG dose-dependently increased, rather than decreased, NAc extracellular glutamate levels (Xi et al., unpublished data). Clearly, these findings conflict with previous reports that GVG inhibits cocaine- and other addictive drug-induced increases in NAc DA (Dewey et al., 1997; Morgan and Dewey, 1998; Schiffer et al., 2000). The precise reasons for this discrepancy are unclear. First, the present ineffectiveness of GVG on NAc DA is unlikely to have been due to the doses being too low, because such doses (25–300 mg/kg) dose-dependently inhibited cocaine- or sucrose-triggered reinstatement (present study) and increase extracellular glutamate levels (Xi et al., unpublished data); and these are the effective doses used in other experiments with drug self-administration, conditioned place preference, locomotor sensitization and intracranial brain stimulation reward (Kushner et al., 1997, 1999; Dewey et al., 1997, 1998; Barrett et al., 2005; Gardner et al., 2002). Second, the present ineffectiveness is also unlikely to have been due to inappropriate GVG pretreatment time, because GVG, when administered either 1, 3 or 6 h prior to cocaine priming, still failed to alter either basal or cocaine-enhanced NAc DA (the present study), but inhibited cocaine self-administration, cocaine-induced place preference and brain stimulation reward (Kushner et al., 1997, 1999; Dewey et al., 1997, 1998; Barrett et al., 2005). Third, the present ineffectiveness would appear to be unrelated to animals' cocaine experience, because the same ineffectiveness was observed in both cocaine-treated rats and drug naïve rats. We, therefore, are drawn to speculate that differences in rat strains (Long-Evans vs. Sprague–Dawley) and/or brain regions of microdialysis sampling (medial NAc core/shell in the present study vs. unspecified anatomic domains or sub-domains in other studies) likely contributed to the different results observed in the present study and previous reports. Whatever the reasons, the present study, by simultaneously measuring extracellular GABA and DA levels in the same microdialysis samples, appears to clearly demonstrate that GVG, when administered systemically (1–6 h prior to cocaine), or locally into the NAc, dose-dependently elevates (100–600%) extracellular GABA, but fails to inhibit NAc DA. Given that GVG-induced increases in extracellular GABA and glutamate are derived predominantly from non-neuronal (glial) sources (Xi et al., unpublished data), we suggest that enhanced extrasynaptic GABA may not diffuse sufficiently into synaptic clefts to inhibit DA release. This is consistent with previous findings that local NAc perfusion of GABAA or GABAB receptor agonists, but not GABA itself, inhibits NAc DA and glutamate (Xi and Stein, 1998, 1999; Xi et al., 2003), and similarly drug (cocaine or heroin) self-administration and reinstatement of drug-seeking behaviors (Xi and Stein, 1999; McFarland et al., 2003; Roberts and Brebner, 2000). In other words, synaptic GABA may modulate DA or glutamate release as shown previously (Xi et al., 2003), while extra-synaptic GABA may not necessarily modulate presynaptic DA or glutamate release, depending upon extra-synaptic GABA levels and the density of extra-synaptic GABA transporters that may protect synaptic GABA transmission by removing extracellular GABA before it reaches the synaptic cleft. GVG's ineffectiveness on NAc DA suggests that DA independent mechanisms may underlie GVG-induced inhibition of drug-seeking behavior.

4.3. GABAergic mediation of GVG's inhibition of drug-seeking behavior

The present findings also indicate that GVG (25–300 mg/kg) produces a slow-onset (1 h) and long-acting (at least 6 h) dose-orderly increase in NAc GABA levels. Such a long duration of GVG on brain GABA levels is consistent with GVG's irreversible action (Cubells et al., 1986) and the low turnover rate of GABA transaminase (Kang et al., 2001). Although it has been long believed that GVG's antagonism of drug-taking behavior in animals is mediated by elevation of brain GABA levels, which in turn inhibits drug-induced increases in NAc DA (Dewey et al., 1997, 1998; Kushner et al., 1997, 1999), no study has previously directly measured GVG-induced changes in extracellular GABA levels or GABA and DA levels in the brain reward system during drug self-administration. In the present study, we found that systemic or intra-NAc GVG dose-dependently elevated extracellular GABA, which lasted for at least 5–6 h. Given that GVG did not inhibit cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA, we believe that GVG-induced increases in GABA may play a more direct role in inhibiting cocaine-triggered reinstatement than we had previously surmised. It is well documented that GABAergic neurons in the brain's reward circuitry play an important role in opiate or psychostimulant reward (Koob and Bloom, 1988; Self and Nestler, 1995; Wise, 1998; Xi and Stein, 2002), and that cocaine, opiates and DA produce an inhibitory effect on GABAergic neurons or GABA release in their projection areas (Uchimura and North, 1990; Qiao et al., 1990; White et al., 1993; Cameron and Williams, 1994; Nicola and Malenka, 1997; Xi and Stein, 2002; Centonze et al., 2002). Based on this, we believe that GVG-elevated GABA levels in brain reward circuitry might directly counteract the actions of cocaine, opiates or DA on GABAergic neurons, thereby antagonizing cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. The role of an increase in extracellular GABA levels in the NAc remains to be determined. One possibility is that an increase in NAc GABA levels may hyperpolarize NAc medium spiny (GABAergic) neurons, and therefore desensitize NAc neuronal responses to cocaine-induced increases in NAc DA and inhibit cocaine-triggered reinstatement. However, this is unlikely because our previous studies have shown that selective elevation of NAc GABA levels by microinjection of GVG into the NAc failed to inhibit heroin self-administration (Xi and Stein, 2000), while microinjections of GVG into the ventral tegmental area (VTA) or the ventral palladium (VP), the primary NAc GABAergic projection area (Smith and Bolam, 1990; Bennett and Bolam, 1994), almost completely inhibit heroin self-administration (Xi and Stein, 2000). These data suggest that GVG-induced increases in extracellular GABA in the VTA or VP, but not in the NAc, may play a critical role in attenuating heroin's rewarding effects. Based on this, we believe that GVG-induced increases in extracellular GABA in the VTA and the VP may play a similarly important role in attenuating cocaine-triggered reinstatement by counteracting cocaine-induced reductions in extracellular GABA levels as shown previously (Tang et al., 2005). Although we did not measure extracellular GABA levels in the VTA or VP in the present study, we believe that a similar increase in extracellular GABA after GVG can be expected based upon the wide distribution of GABA transaminase in rat brain (Reijnierse et al., 1975; Chan-Palay et al., 1979) and the antagonism by intra-VTA or intra-VP GVG of heroin self-administration (Xi and Stein, 2000). Further experiments will be required to shed light upon this hypothesis.

In conclusion, the present data – and their preliminary presentations in abstract form (Peng et al., 2004, 2006) – show, for the first time, that systemic administration of GVG dose-dependently inhibits cocaine-induced relapse to drug-seeking behavior, an effect correlated with an increase in NAc GABA. NAc DA does not appear to be involved in GVG's inhibition of cocaine-primed relapse. Given that acute cocaine or DA produces an inhibitory effect on GABAergic transmission, GVG-induced increases in GABA may functionally antagonize such a reduction in GABAergic transmission, thereby antagonizing cocaine-primed relapse. By whatever mechanism, the present data add further support to the preclinical animal model evidence suggesting a potential anti-addiction pharmacotherapeutic utility for GVG.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding source: Funding for this study was provided by funds from the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Public Health Service (PHS), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). Preliminary planning of these experiments was supported by research grants from the Aaron Diamond Foundation of New York City and from the Old Stones Foundation of Greenwich, Connecticut, and by funds from the Medical and Chemistry Departments of the Brookhaven National Laboratory, Upton, New York.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: Authors Brodie, Dewey, and Ashby are the holders of a patent for the use of GVG as an antiaddiction pharmacotherapeutic agent for humans. All rights to said patent have been assigned to Brookhaven National Laboratory, under terms whereby authors Brodie, Dewey, and Ashby do not now and will not in the future receive any royalties that may be earned from the use of GVG as an anti-addiction agent in humans. Authors Brodie and Dewey serve on the Scientific Advisory Board of Catalyst Pharmaceutical Partners, which holds a license from Brookhaven National Laboratory for the development of GVG as an anti-addiction therapeutic agent in humans. Authors Brodie and Dewey have no fiduciary responsibilities with respect to Catalyst Pharmaceutical Partners, and are not significant stockholders therein. Authors Brodie, Dewey, and Gardner have received de minimus honoraria for scholarly presentations (e.g., at universities and medical schools) regarding GVG's possible anti-addiction utility. The remaining authors declare no financial activities or financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a conflict of interest.

Contributors: Authors Peng, Ashby, Brodie, Dewey, Gardner, and Xi designed the study. Authors Peng, Ashby, Gardner, and Xi carried out the literature searches and summaries of previous work. Authors Peng, Li, Gilbert, and Pak carried out surgery on the experimental animals. Authors Peng, Li, and Xi ran animals in the behavioral paradigms, carried out the in vivo microdialysis experiments, and collected the data. Authors Peng, Gardner, and Xi carried out the statistical analyses of the collected data. Author Peng wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and authors Peng, Gardner, and Xi contributed to correcting, revising, re-writing, and proof-reading the manuscript. Authors Peng, Gardner, and Xi contributed to the drafting, revising, and finalizing of the graphs and figures. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

References

- Anderson SM, Pierce RC. Cocaine-induced alterations in dopamine receptor signaling: implications for reinforcement and reinstatement. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;106:389–403. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett AC, Negus SS, Mello NK, Caine SB. Effect of GABA agonists andGABA-A receptor modulators on cocaine- and food-maintained responding and cocaine discrimination in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;315:858–871. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.086033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett BD, Bolam JP. Synaptic input and output of parvalbumin-immunoreactive neurons in the neostriatum of the rat. Neuroscience. 1994;62:707–719. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron DL, Williams JT. Cocaine inhibits GABA release in the VTA through endogenous 5-HT. J Neurosci. 1994;14:6763–6767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-11-06763.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze D, Picconi B, Baunez C, Borrelli E, Pisani A, Bernardi G, Calabresi P. Cocaine and amphetamine depress striatal GABAergic synaptic transmission through D2 dopamine receptors. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:164–175. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan-Palay V, Wu JY, Palay SL. Immunocytochemical localization of gamma-aminobutyric acid transaminase at cellular and ultrastructural levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:2067–2071. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.4.2067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cubells JF, Blanchard JS, Smith DM, Makman MH. In vivo action of enzyme-activated irreversible inhibitors of glutamic acid decarboxylase and γ-aminobutyric acid transaminase in retina vs. brain. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1986;238:508–514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer ANM, Binnekade R, Raasø H, Vanderschuren LJMJ. Relapse to cocaine- and heroin-seeking behavior mediated by dopamine D2 receptors is time-dependent and associated with behavioral sensitization. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:18–26. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Chaurasia CS, Chen CE, Volkow ND, Clarkson FA, Porter SP, Straughter-Moore RM, Alexoff DL, Tedeschi D, Russo NB, Fowler JS, Brodie JD. GABAergic attenuation of cocaine-induced dopamine release and locomotor activity. Synapse. 1997;25:393–398. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199704)25:4<393::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey SL, Morgan AE, Ashby CR, Jr, Horan B, Kushner SA, Logan J, Volkow ND, Fowler JS, Gardner EL, Brodie JD. A novel strategy for the treatment of cocaine addiction. Synapse. 1998;30:119–129. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199810)30:2<119::AID-SYN1>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner EL, Schiffer WK, Horan BA, Highfield D, Dewey SL, Brodie JD, Ashby CR., Jr Gamma-vinyl GABA, an irreversible inhibitor of GABA transaminase, alters the acquisition and expression of cocaine-induced sensitization in male rats. Synapse. 2002;46:240–250. doi: 10.1002/syn.10138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW. Glutamate systems in cocaine addiction. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW, Volkow ND. The neural basis of addiction: a pathology of motivation and choice. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1403–1413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang TC, Park SK, Bahn JH, Chang JS, Cho SW, Choi SY, Won MH. Comparative studies on the GABA-transaminase immunoreactivity in rat and gerbil brains. Mol Cells. 2001;11:321–325. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koob GF, Bloom FE. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of drug dependence. Science. 1988;242:715–723. doi: 10.1126/science.2903550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhar MJ, Pilotte NS. Neurochemical changes in cocaine withdrawal. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1996;17:260–264. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(96)10024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SA, Dewey SL, Kornestsky C. The irreversible γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transaminase inhibitor γ-vinyl-GABA blocks cocaine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:797–802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner SA, Dewey SL, Kornetsky C. Gamma-vinyl GABA attenuates cocaine-induced lowering of brain stimulation reward thresholds. Psychopharmacology. 1997;133:383–388. doi: 10.1007/s002130050418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L, Grimm JW, Shaham Y, Hope BT. Molecular neuroadaptations in the accumbens and ventral tegmental area during the first 90 days of forced abstinence from cocaine self-administration in rats. J Neurochem. 2003;85:1604–1613. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.01824.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarland K, Lapish CC, Kalivas PW. Prefrontal glutamate release into the core of the nucleus accumbens mediates cocaine-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3531–3537. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03531.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan AE, Dewey SL. Effects of pharmacologic increases in brain GABA levels on cocaine-induced changes in extracellular dopamine. Synapse. 1998;28:60–65. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199801)28:1<60::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neisewander JL, O'Dell LE, Tran-Nguyen LTL, Castañeda E, Fuchs RA. Dopamine overflow in the nucleus accumbens during extinction and reinstatement of cocaine self-administration behavior. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1996;15:506–514. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(96)00097-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicola SM, Malenka RC. Dopamine depresses excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission by distinct mechanisms in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 1997;17:5697–5710. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-15-05697.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien CP, Gardner EL. Critical assessment of how to study addiction and its treatment: human and non-human animal models. Pharmacol Ther. 2005;108:18–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. fourth. Academic Press; San Diego: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Peng XQ, Li X, Gilbert J, Pak A, Ashby C, Xi ZX, Gardner EL. Gamma-vinyl GABA inhibits cocaine-primed relapse by a DA-independent mechanism. Abstracts of the 68th Annual Scientific Meeting of the College on Problems of Drug Dependence; 2006; Phoenix, Arizona. 2006. Abstract # 616. [Google Scholar]

- Peng XQ, Xi ZX, Gilbert J, Campos A, Dewey SL, Schiffer WK, Brodie JD, Ashby CR, Gardner EL. Gamma-vinyl GABA, but not gabapentin, inhibits cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in the rat. Abstracts of the 34th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; 2004; San Diego, CA. 2004. Abstract # 691.8. [Google Scholar]

- Qiao JT, Dougherty PM, Wiggins RC, Dafny N. Effects of microiontophoretic application of cocaine, alone and with receptor antagonists, upon the neurons of the medial prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens and caudate nucleus of rats. Neuropharmacology. 1990;29:379–385. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(90)90098-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijnierse GL, Veldstra H, Van den Berg CJ. Subcellular localization of γ-aminobutyrate transaminase and glutamate dehydrogenase in adult rat brain. Evidence for at least two small glutamate compartments in brain. Biochem J. 1975;152:469–475. doi: 10.1042/bj1520469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts DCS, Brebner K. GABA modulation of cocaine self-administration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;909:145–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06680.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer WK, Gerasimov MR, Bermel RA, Brodie JD, Dewey SL. Stereoselective inhibition of dopaminergic activity by gamma vinyl-GABA following a nicotine or cocaine challenge: a PET/microdialysis study. Life Sci. 2000;66:PL169–PL173. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00432-x. Pharmacol. Lett. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Barnhart WJ, Lehman DA, Nestler EJ. Opposite modulation of cocaine-seeking behavior by D1- and D2-like dopamine receptor agonists. Science. 1996;271:1586–1589. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5255.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self DW, Nestler EJ. Molecular mechanisms of drug reinforcement and addiction. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1995;18:463–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.18.030195.002335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sesack SR, Pickel VM. Prefrontal cortical efferents in the rat synapse on unlabeled neuronal targets of catecholamine terminals in the nucleus accumbens septi and on dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area. J Comp Neurol. 1992;320:145–160. doi: 10.1002/cne.903200202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shalev U, Grimm JW, Shaham Y. Neurobiology of relapse to heroin and cocaine seeking: a review. Pharmacol Rev. 2002;54:1–42. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AD, Bolam JP. The neural network of the basal ganglia as revealed by the study of synaptic connections of identified neurones. Trends Neurosci. 1990;13:259–265. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(90)90106-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staley JK, Mash DC. Adaptive increase in D3 dopamine receptors in the brain reward circuits of human cocaine fatalities. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6100–6106. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06100.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang XC, McFarland K, Cagle S, Kalivas PW. Cocaine-induced reinstatement requires endogenous stimulation of μ-opioid receptors in the ventral pallidum. J Neurosci. 2005;25:4512–4520. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0685-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchimura N, North RA. Actions of cocaine on rat nucleus accumbens neurones in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1990;99:736–740. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1990.tb12999.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorel SR, Ashby CR, Jr, Paul M, Liu X, Hayes R, Hagan JJ, Middlemiss DN, Stemp G, Gardner EL. Dopamine D3 receptor antagonism inhibits cocaine-seeking and cocaine-enhanced brain reward in rats. J Neurosci. 2002;22:9595–9603. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-21-09595.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White FJ, Hu XT, Henry DJ. Electrophysiological effects of cocaine in the rat nucleus accumbens: microiontophoretic studies. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;266:1075–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Drug-activation of brain reward pathways. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1998;51:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(98)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Gilbert JG, Peng XQ, Pak AC, Li X, Gardner EL. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 inhibits cocaine-primed relapse in rats: role of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8531–8636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0726-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Ramamoorthy S, Shen H, Lake R, Samuvel DJ, Kalivas PW. GABA transmission in the nucleus accumbens is altered after withdrawal from repeated cocaine. J Neurosci. 2003;23:3498–3505. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-08-03498.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Stein EA. Nucleus accumbens dopamine release modulation by mesolimbic GABAA receptors—an in vivo electrochemical study. Brain Res. 1998;798:156–165. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Stein EA. Baclofen inhibits heroin self-administration behavior and mesolimbic dopamine release. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:1369–1374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Stein EA. Increased mesolimbic GABA concentration blocks heroin self-administration in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi ZX, Stein EA. GABAergic mechanisms of opiate reinforcement. Alcohol Alcohol. 2002;37:485–494. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/37.5.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]