Abstract

Tissue-specific knockouts generated through Cre-loxP recombination have become an important tool to manipulate the mouse genome. Normally, two successive rounds of breeding are performed to generate mice carrying two floxed target-gene alleles and a transgene expressing Cre-recombinase tissue-specifically. We show herein that two promoters commonly used to generate endothelium-specific (Tie2) and smooth muscle-specific [smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (Smmhc)] knockout mice exhibit activity in the female and male germ lines, respectively. This can result in the inheritance of a null allele in the second generation that is not tissue specific. Careful experimental design is required therefore to ensure that tissue-specific knockouts are indeed tissue specific and that appropriate controls are used to compare strains.

Keywords: Cre-loxP, knockout, conditional, vascular, endothelium, smooth muscle myosin heavy chain

tissue- or cell type-specific promoters have been used extensively to drive expression of Cre-recombinase, thereby allowing selective knockout of a “floxed” target gene (reviewed in Ref. 16). This strategy allows one to examine the consequences of cell-selective loss-of-function while preserving the function of the target gene in other cells and tissues. To target the vasculature, the murine endothelial receptor tyrosine kinase (Tie2) (15) and rat smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (Smmhc) (11) regulatory sequences have been extensively employed, and many examples of endothelium- and smooth muscle-specific deletion have been reported (see as examples Refs.: 1–3, 7, 8, 10, 13). The tissue specificity of these regulatory sequences has been extensively studied, suggesting they can be used to effectively generate endothelium- and smooth muscle-specific knockout models (4, 6, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17). In our effort to generate mice lacking peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (Pparg) specifically in endothelial and vascular muscle cells we determined that both the Tie2 and Smmhc regulatory sequences are able to drive expression of Cre-recombinase in the female and male germ line, respectively. This causes the conversion of the floxed allele to a null allele in the germ line, which is transmitted to offspring, which can result in global deletion irrespective of their Cre-recombinase genotype.

RESULTS

Endothelial Cell-Targeted Mice

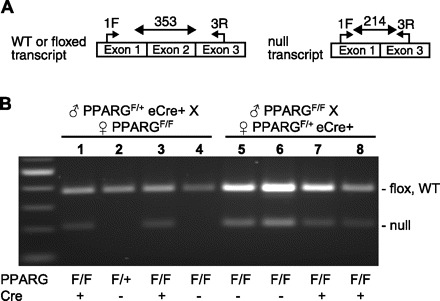

Tie2-Cre, herein termed eCre+ [Jackson Laboratory no. 004128, B6.Cg-Tg(Tek-cre)12Flv/J], males were crossed to homozygous PPARGF/F (13) females to generate 162 F1 offspring, all of which were heterozygous for the floxed allele, and nearly 50% were eCre+ (PPARGF/+eCre+).1 Even in F1 mice, a PCR product with lesser intensity than either the floxed or wild-type alleles and confirmed as the null allele by DNA sequencing was evident (Fig. 1B, lanes 1 and 2). The null allele was detected in genomic DNA of 76% of the mice, all of which were eCre+. In the second generation, PPARGF/+ eCre+ mice were backcrossed to PPARGF/F mice, generating 172 offspring. The PPARG null allele was detected in genomic DNA from 42% of the offspring, 31% of which were eCre−. The intensity of the null allele was low in eCre+ mice inheriting the transgene from the male, consistent with eCre activity in endothelial cells in the tail sample (Fig. 1B, lanes 3, 5, 6, and 11). On the contrary, the intensity of the null allele was equal to the floxed allele when it was transmitted through the female even in eCre− mice (Fig. 1B, lane 15), indicating a 1:1 ratio of floxed and null alleles.

Fig. 1.

Genotyping of Tie2-cre and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARG) mice. A: schematic showing the 3 alleles of Pparg. The positions of PCR primers, location of loxP sites (filled triangles), and the expected PCR product sizes are indicated. Genotyping of the Pparg floxed allele and the eCre or sCre transgenes was performed as previously described (13, 17). WT, wild type. B: PCR genotyping for Pparg and Tie2-Cre is shown. Lanes 1–2 are offspring of a 1st cross (♂eCre+ × ♀PPARGF/F); lanes 3–11 are offspring of a 2nd cross where eCre was passed through the male (♂PPARGF/+ eCre+ × ♀PPARGF/F); lanes 12–15 are offspring of a 2nd cross where eCre was passed through the female (♂PPARGF/F × ♀PPARGF/+ eCre+). C: table shows the number of mice distributed by genotype. The expected number of animals is indicated in brackets. F2male−cre and F2female−cre represent the eCre transgene transmitted to F2 generation through the male and female germ line, respectively.

To investigate this “eCre-independent” gene deletion further, F2 offspring were retrospectively separated into two groups based on the sex of the eCre+ transmitting parent (Fig. 1C). The null allele was never detected in genomic DNA from eCre− F2 offspring when it was transmitted through the male germ line (Fig. 1B, lanes 4, 7–10), indicating that the Tie2 promoter is not active in the male germ line. However, when the eCre+ allele was transmitted through the female germ line, the null allele was detected in genomic DNA from 100% of PPARGF/F (Fig. 1B, lane 15) and 40.0% of PPARGF/+ F2 offspring even if they genotyped as eCre−.

We next designed an RT-PCR assay to distinguish between the full-length Pparg transcript (originating from either the wild-type or floxed allele) and the null transcript (originating from conversion of a Pparg floxed allele to a null allele) (Fig. 2A). Aortic RNA from F2 mice in which the eCre transgene was transmitted through the male or female germ line were assayed by RT-PCR (Fig. 2B). A null transcript was not detected in Cre− offspring if the male parent was eCre+ (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 4). However, the null transcript was detected in aorta even if the mice were eCre−, but only if the female parent was eCre+ transgene (compare lanes 2 and 4 with 5 and 6 in Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

RT-PCR assay. A: schematic of the mRNA species generated from the 3 alleles shown in Fig. 1A. The primers used for RT-PCR are shown along with their expected size. B. aortic RT-PCR products generated from F2 endothelial-null offspring. Lanes 1–4 are RT-PCR products generated from samples where eCre was passed through the male; lanes 5–8 are RT-PCR products generated from samples where eCre was passed through the female. The animal genotype as assessed by tail genomic DNA is indicated below the figure. Total RNA was isolated from thoracic aorta using TriReagent (Molecular Research Center), DNase I treated and repurified using RNeasy spin columns (Qiagen). cDNA was generated by reverse transcription PCR using Superscript III (Invitrogen); 10 ng of reverse transcribed RNA was PCR amplified using primers 1-forward (F): AGACCACTCGCATTCCTTTGACAT and 3-reverse (R): TCCGGCAGTTAAGATCACACC.

Smooth Muscle Cell-Targeted Mice

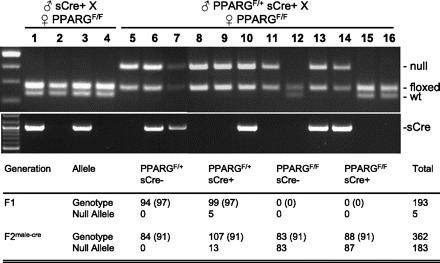

We employed a similar strategy for the generation of PPARGF/F Smmhc-Cre+ (sCre+). As it was known that the Smmhc promoter is activated in the female germ line (M. Kotlikoff, personal communication) we set up crosses only where the sCre+ allele was transmitted through the male germ line. All 193 F1 offspring were heterozygous for the floxed allele (PPARGF/+) and ∼50% were sCre+ (Fig. 3). A breeding of PPARGF/+ sCre+ F1 males with PPARGF/F females produced 362 F2 offspring with a near equal distribution among the expected genotypes. Strikingly, the null allele was detected in genomic DNA from all but one PPARGF/F mouse, irrespective of sCre genotype (Fig. 3, lanes 5, 8, and 9 vs. 6, 7, and 10). The null allele was not detected in any animals with a genotype of PPARGF/+ sCre− because they inherited the wild-type allele from the male sCre+ parent (Fig. 3, lanes 12, 15, and 16). The expression of the null allele was subsequently confirmed by RT-PCR in aorta from PPARGF/F mice irrespective of their sCre genotype (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Genotyping of smooth muscle myosin heavy chain (SMMHC)-cre and PPARG mice. PCR genotyping for Pparg and SMMHC-cre is shown. Lanes 1–4 are offspring of a 1st cross (♂sCre+ × ♀PPARGF/F); lanes 5–16 are offspring of a 2nd cross where sCre was passed through the male (♂PPARGF/+ sCre+ × ♀PPARGF/F). The table shows the number of mice distributed by genotype. The expected number of animals is indicated in brackets. F2male−cre represent the eCre transgene transmitted to F2 generation through the male germ line.

DISCUSSION

We generated two models in which we attempted to selectively ablate the Pparg gene in the endothelium and vascular muscle, respectively. Our data suggests that the Smmhc promoter drives Cre-recombinase expression in the male germ line prior to the second meiotic division, resulting in the global deletion of the paternally inherited floxed allele, even in sCre− offspring. This hypothesis is supported by data showing that SMMHC protein is present in primary spermatocytes at the zygotene to early diplotene stage (5). On the contrary, there was no evidence of male germ line expression of the eCre+ transgene. The eCre+ transgene, however, was apparently expressed in the female germ line. It is interesting to note that in many instances (40%), the null allele was detected at an intensity similar to that of the wild-type allele in F2 mice genotyped as PPARGF/+eCre− when eCre+ (and the Pparg wild-type allele) was transmitted by the female. This efficient conversion of the paternal floxed allele suggests that there may be retention of Cre-recombinase activity in the early embryo after fertilization.

Our data regarding activation of Cre-recombinase expression by the Tie2 and Smmhc in the germ line are in agreement with other studies using other floxed genes (7, 9), strongly suggesting our observations are not an aberration caused by Pparg locus. Our data raise some concerns regarding study design and control selection that must be considered when interpreting the results of experiments where either the breeding scheme was not detailed or the sex of the Cre-transmitting parent considered. Unfortunately, it is difficult to assess if this has adversely affected published studies as often the details of the intercross between floxed and Cre mice are not very thorough and the amount of genotyping information provided is minimal. Consequently, can this problem be avoided? In terms of the Tie2-Cre model and other Cre-recombinase models with similar problems, complications arising from germ line Cre-recombinase activity can be avoided by transmitting the transgene through the male germ line. Recall that none of the Cre− offspring from mice bred in this manner had the null allele and there was no expression of the null allele at the mRNA if the mice were Cre−. The situation is more complicated for the smooth muscle-specific promoter and other Cre-recombinase transgenes found to be expressed in both the male and female germ lines. In this case, mice expected to be GeneF/F Cre+ or − in the F2 generation are effectively GeneF/null Cre+ or −. This would still allow the generation of a cell-specific null as long as the F2 mice are not continuously intercrossed. Further intercrossing could potentially generate mice that are Genenull/null. Furthermore, care should be taken that only GeneF/null Cre− littermates are selected as controls.

In conclusion, we have shown that activation of Cre expression by the Tie2 and Smmhc promoters occurs in the female and male germ lines, respectively. We believe that both these promoters can be used successfully to develop vascular-specific knockout mice providing that germ line expression of Cre is taken into account in design of the study. If investigators are uncertain whether their favorite Cre-recombinase transgene is expressed in germ cells, they should make an effort to ensure that their genotyping assay can detect and distinguish between the wild-type, floxed, and null allele and to keep accurate records of the genotypes of the offspring. Designing an RT-PCR assay that also detects an expressed null allele can also provide an important diagnostic tool to determine if faithful cell-specific knockout is occurring. If these issues are kept in mind, the only factor that should influence the success of a cell-specific knockout project is the effectiveness of the promoter for driving Cre-recombinase in an appropriate spatial and temporal manner.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michael Kotlikoff (Cornell University) for the gift of Smmhc-Cre mice and for many discussions during the writing of this manuscript. We thank Dr. Frank Gonzalez (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health) for the gift of the PPARGF/F mice.

Footnotes

Address for reprint requests and other correspondence: C. D. Sigmund, Depts. of Internal Medicine and Physiology & Biophysics, 3181B Medical Education and Biomedical Research Facility, Roy J. and Lucille A. Carver Collage of Medicine, Univ. of Iowa, Iowa City, IA 52242 (e-mail: curt-sigmund@uiowa.edu).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Care of the mice used in the experiments met the standards set forth by the National Institutes of Health in its guidelines for the care and use of experimental animals, and all procedures were approved by the University Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Iowa.

REFERENCES

- 1.BagnallAJ, Kelland NF, Gulliver-Sloan F, Davenport AP, Gray GA, Yanagisawa M, Webb DJ, Kotelevtsev YV. Deletion of endothelial cell endothelin B receptors does not affect blood pressure or sensitivity to salt. Hypertension 48: 286–293, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.BrarenR, Hu H, Kim YH, Beggs HE, Reichardt LF, Wang R. Endothelial FAK is essential for vascular network stability, cell survival, and lamellipodial formation. J Cell Biol 172: 151–162, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.CattelinoA, Liebner S, Gallini R, Zanetti A, Balconi G, Corsi A, Bianco P, Wolburg H, Moore R, Oreda B, Kemler R, Dejana E. The conditional inactivation of the beta-catenin gene in endothelial cells causes a defective vascular pattern and increased vascular fragility. J Cell Biol 162: 1111–1122, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ConstienR, Forde A, Liliensiek B, Grone HJ, Nawroth P, Hammerling G, Arnold B. Characterization of a novel EGFP reporter mouse to monitor Cre recombination as demonstrated by a Tie2 Cre mouse line. Genesis 30: 36–44, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De MartinoC, Capanna E, Nicotra MR, Natali PG. Immunochemical localization of contractile proteins in mammalian meiotic chromosomes. Cell Tissue Res 213: 159–178, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.FordeA, Constien R, Grone HJ, Hammerling G, Arnold B. Temporal Cre-mediated recombination exclusively in endothelial cells using Tie2 regulatory elements. Genesis 33: 191–197, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.FrutkinAD, Shi H, Otsuka G, Leveen P, Karlsson S, Dichek DA. A critical developmental role for tgfbr2 in myogenic cell lineages is revealed in mice expressing SM22-Cre, not SMMHC-Cre. J Mol Cell Cardiol 41: 724–731, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.GitlerAD, Kong Y, Choi JK, Zhu Y, Pear WS, Epstein JA. Tie2-Cre-induced inactivation of a conditional mutant Nf1 allele in mouse results in a myeloproliferative disorder that models juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatr Res 55: 581–584, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.KoniPA, Joshi SK, Temann UA, Olson D, Burkly L, Flavell RA. Conditional vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 deletion in mice: impaired lymphocyte migration to bone marrow. J Exp Med 193: 741–754, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LiaoY, Regan CP, Manabe I, Owens GK, Day KH, Damon DN, Duling BR. Smooth muscle-targeted knockout of connexin43 enhances neointimal formation in response to vascular injury. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1037–1042, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MadsenCS, Regan CP, Hungerford JE, White SL, Manabe I, Owens GK. Smooth muscle-specific expression of the smooth muscle myosin heavy chain gene in transgenic mice requires 5′-flanking and first intronic DNA sequence. Circ Res 82: 908–917, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ManabeI, Owens GK. The smooth muscle myosin heavy chain gene exhibits smooth muscle subtype-selective modular regulation in vivo. J Biol Chem 276: 39076–39087, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.NicolCJ, Adachi M, Akiyama TE, Gonzalez FJ. PPARgamma in endothelial cells influences high fat diet-induced hypertension. Am J Hypertens 18: 549–556, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ReganCP, Manabe I, Owens GK. Development of a smooth muscle-targeted cre recombinase mouse reveals novel insights regarding smooth muscle myosin heavy chain promoter regulation. Circ Res 87: 363–369, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.SchlaegerTM, Bartunkova S, Lawitts JA, Teichmann G, Risau W, Deutsch U, Sato TN. Uniform vascular-endothelial-cell-specific gene expression in both embryonic and adult transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 3058–3063, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WamhoffBR, Sinha S, Owens GK. Conditional mouse models to study developmental and pathophysiological gene function in muscle. Handb Exp Pharmacol 441–468, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.XinHB, Deng KY, Rishniw M, Ji G, Kotlikoff MI. Smooth muscle expression of Cre recombinase and eGFP in transgenic mice. Physiol Genomics 10: 211–215, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]