Summary

Background

Human skin emits a variety of volatile metabolites, many of them odorous. Much previous work has focused upon chemical structure and biogenesis of metabolites produced in the axillae (underarms), which are a primary source of human body odour. Nonaxillary skin also harbours volatile metabolites, possibly with different biological origins than axillary odorants.

Objectives

To take inventory of the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) from the upper back and forearm skin, and assess their relative quantitative variation across 25 healthy subjects.

Methods

Two complementary sampling techniques were used to obtain comprehensive VOC profiles, viz., solid-phase micro extraction and solvent extraction. Analyses were performed using both gas chromatography/mass spectrometry and gas chromatography with flame photometric detection.

Results

Nearly 100 compounds were identified, some of which varied with age. The VOC profiles of the upper back and forearm within a subject were, for the most part, similar, although there were notable differences.

Conclusions

The natural variation in nonaxillary skin odorants described in this study provides a baseline of compounds we have identified from both endogenous and exogenous sources. Although complex, the profiles of volatile constituents suggest that the two body locations share a considerable number of compounds, but both quantitative and qualitative differences are present. In addition, quantitative changes due to ageing are also present. These data may provide future investigators of skin VOCs with a baseline against which any abnormalities can be viewed in searching for biomarkers of skin diseases.

Keywords: biomarkers, gas chromatography/mass spectrometry, human skin odour, solid-phase microextraction, volatile organic compounds

Skin is the largest human organ, accounting for approximately 12-15% of body weight.1 Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emanating from skin contribute to a person’s body odour, and may convey important information about metabolic processes. VOCs from skin derive from eccrine, sebaceous and apocrine gland secretions and their interactions with resident skin bacteria.2,3 These glands are distributed differently across the body; hence different regions of the body have different VOC profiles, and thus different odours.

Eccrine glands are found throughout the skin, but are especially concentrated in palms of hands, soles of feet, and the forehead. Eccrine sweat is mostly water, but contains glycoproteins (notably interleukin 1), lactic acid, sugars, amino acids and electrolytes.4

Sebaceous glands are concentrated on the upper part of the body.3 The upper chest, back, scalp, face and forehead may have as many as 400-900 sebaceous glands cm-2. Sebaceous gland secretions are rich in lipid materials such as cholesterol, cholesterol esters, long-chain fatty acids, squalene and triglycerides.3 These lipids provide substrate for growth and metabolism of skin microorganisms.

Apocrine glands are concentrated in the axillae, pubic area and areolas.2,4 Apocrine secretions are the chief source of underarm odorants (commonly known as ‘body odour’) and play a role in chemical signalling (for a review see Wysocki and Preti.5) Many previous studies have focused on VOCs emanating from the axillae, which reflect some contribution from all skin glands located in the axillae.6-10

VOCs from nonaxillary skin secretions have been studied as potential mosquito attractants,11-13 indicators of seasonal changes14 and ageing,15 and moderators of fragrances.16-19 It was recently demonstrated that skin emanations could be collected via rolling a stir-bar coated with polydimethylsiloxane across the arm with subsequent desorption and analysis by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (GC/MS).20 Bernier et al.11-13 reported that hundreds of compounds canbe volatilized from skin secretions collected from the palms and backs of hands. Most of these compounds have been documented to be organic acids ranging in carbon size from C2 to C20. However, the most abundant (75-80%) organic acids found on skin are C16 and C18 saturated, monounsaturated and diunsaturated acids,12 which are not volatile at body temperatures.

In contrast, collection of skin VOCs using solid-phase microextraction (SPME) will collect low molecular weight compounds that are volatile at body temperature. SPME-GC/MS analyses of hand/wrist VOCs sampled in both winter and spring revealed 35 organic compounds.14 VOCs were reported to be more abundant in winter samples; however, the relative ratios of many (but not all) of the compounds did not vary between seasons. This observation led the authors to speculate that the moist spring air allowed the skin to harbour more bacteria that hydrolysed and decomposed some of the VOCs.

A study of male Japanese subjects used T-shirts worn for 3 days to collect skin odours. VOCs emanating from rectangular pieces cut from the backs of these T-shirts were studied.15 The authors suggested that skin secretions in men older than age 39 years contain larger amounts of unsaturated aldehydes than secretions from younger men. These compounds, particularly 2-nonenal, were reported to impart an unpleasant ‘ageing odour’ to older Japanese men.

Most acids, alcohols and aldehydes found in skin secretions apparently originate from the interactions between sebaceous gland secretions and cutaneous bacteria.12,21 Anaerobic bacteria living in the hair follicle/sebaceous gland duct use lipases to liberate long-chain acids from triglycerides, which are further metabolized by aerobic bacteria into longer, saturated and unsaturated acids and smaller volatile acids, aldehydes and alcohols.21

Other potential sources of skin volatiles are putative odorants carried by the apocrine secretion odour-binding protein (ASOB) 1.22 This protein might bind odorous acids that can be liberated by interaction with cutaneous bacteria. A previous study demonstrated that this protein does carry odorants in the underarm, and is present in sebaceous-rich perspiration from the forehead.22

Tracking dogs trained to recognize an individual’s scent on garments from a particular body part (e.g. chest, arm, leg) are not reliably able to generalize the individual’s odour to other body parts, suggesting that a different odorant milieu may characterize the back and forearm (for a review see Jenkins23). In this study, we performed a comprehensive analysis of VOCs from the upper back and forearm of 25 healthy subjects using two complementary sampling techniques, SPME and solvent extraction. Skin secretions from the back of each subject also were analysed for the presence of the potential VOC carrier ASOB1.

The goals of the study were: (i) to identify VOCs emanating from the upper back and forearm skin; (ii) to determine whether VOCs vary in a qualitative or quantitative manner; and (iii) to determine if VOCs vary in relative abundance with gender, age or locus, i.e. back and forearm. The upper back and forearm were chosen because they are easily accessible with minimal inconvenience to subjects. In addition, these body regions differ with respect to density of sebaceous glands (upper back > forearm) and skin bacteria, as well as exposure to sun, environment and consumer products.3,21

Materials and methods

Human subjects

All protocols were approved by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board (IRB) for Research Involving Human Subjects. Subjects were also asked to read and sign IRB-approved consent forms before starting the study protocol. Twenty-five adults - 13 men and 12 women - were recruited and financially compensated for their participation. Demographic characteristics are given in Table 1. The definition of ‘young’ or ‘old’ was as follows: young, 19-40 years; old, 41-79 years. Both our subject numbers and our definition of ‘young’ and ‘old’ correspond well with the research performed by Japanese investigators on skin odour.15

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of subjects

| Ethnic group, gender and age category | No. subjects | Ages (years) | Western blot lane no. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caucasian | |||

| M, old | 3 | 41, 79, 79 | 29 |

| M, young | 4 | 19, 23, 23, 27 | 26 |

| F, old | 6 | 44, 48, 48, 51, 53, 75 | 24 |

| F, young | 4 | 26, 27, 28, 34 | 22 |

| African American | |||

| M, old | 3 | 53, 53, 60 | 27 |

| M, young | 1 | 21 | 15 |

| F, old | 0 | - | - |

| F, young | 0 | - | - |

| Asian | |||

| M, old | 0 | - | - |

| M, young | 2 | 20, 35 | 12 |

| F, old | 0 | - | - |

| F, young | 1 | 40 | 25 |

| Hispanic | |||

| M, old | 0 | - | - |

| M, young | 0 | - | - |

| F, old | 0 | - | - |

| F, young | 1 | 39 | 23 |

Sample collection

Subjects were asked to fill out a confidential questionnaire that assessed their medical history, medications, vitamins, and types of foods normally consumed to help account for any unusual metabolites found in a given individual. For 7-10 days prior to collection, each subject bathed/showered with a fragrance-free liquid soap/shampoo (provided by Symrise, Inc., Teterboro, NJ, U.S.A.) to lessen the impact of exogenous sources of VOCs from consumer products. Subjects were instructed not to use underarm deodorants/antiperspirants and/or colognes and sprays during this time.

On the day of collection, subjects were sampled in a single session. Upper back and forearm collections were made for each subject in the same session, allowing for within-subject comparisons of VOCs from these two regions. Subjects were asked to wear a loose-fitting T-shirt or ‘tank-top’ to provide easy access to the back and forearms. After the subject had completed 5 min of mild exercise (walking up and down the stairs), a glass funnel (internal diameter 10 cm for the back and 7·5 cm for the forearm) was placed over the area of skin from which collections were made (upper back or dorsal side of forearm). The funnel narrows sufficiently to hold in-place a SPME fibre holder in a closed environment.

Solid-phase microextraction to collect skin volatile organic compounds

The fibres used for collection of skin metabolites were 2 cm, 50/30 μm divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane ‘Stableflex’ fibres (Supelco Corp., Bellefonte, PA, U.S.A.). The fibre was exposed above the skin for 30 min through the glass funnel (described above) while the subject sat in a comfortable position. After collecting the volatiles, the SPME fibre was inserted into the hot injector of the GC/MS apparatus (held at 230 °C) and exposed for 1 min to desorb volatiles collected on the fibre. Duplicate SPME samples were collected from opposite sides of the upper back (at or about the level of the axillae), while a third collection was obtained from the subject’s forearm (dorsal side).

Concomitantly, SPME was used to sample the room air (30 min) on each day of collection to determine whether any of the VOCs observed were present in the air surrounding the subject. Volatiles that might arise from the liquid soap also were examined. Two millilitres of the unfragranced soap was placed into a 1-L I-Chem bottle (Nalge Nunc International, New Castle, DE, U.S.A.) and the headspace was sampled via SPME for 30 min.

Solvent extraction of skin secretions

After completing collection of skin VOCs by SPME, a 2-mL portion of a 50/50 mixture of double-distilled ethanol (190 proof; Pharmco, Brookfield, CT, U.S.A.)/single-distilled hexanes (Optima grade; Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, U.S.A.) was applied to each side of the subject’s upper back (at or about the level of the axillae) and 2 mL of double-distilled ethanol was applied to each subject’s forearm to dissolve skin lipids and organic acids found on the skin surface. Only ethanol was applied to the forearm (dorsal side) to prevent possible irritation found to be caused by hexanes. A 15·2 × 3·8 cm (external diameter) glass cylinder was pressed against the skin and the solvent mixture was pipetted into the cylinder, agitated for 30 s and removed. Each extract was stored cold (12 °C) until analysis. On the day of analysis, the extract was concentrated to approximately 50 μL on a rotary evaporator; 5 μL of each sample was then injected into both the GC/MS and the gas chromatography with flame photometric detection (GC/FPD) systems.

Solvent extracts were analysed as composite samples, pooled by age and gender. Back extracts were divided into four categories: young male (≤ 40 years), older male (> 40 years), young female (≤ 40 years) and older female (> 40 years). One hundred microlitres of each subject’s back extract was placed into the appropriate pool and vortexed; 5 lL of each pooled sample was then injected into the GC/MS and GC/FPD systems. Forearm extracts were similarly divided into pooled samples. By pooling the samples in this manner, the average concentrations of the VOCs in each subcategory were examined as a whole to determine any obvious differences attributed to age and gender. These suspected differences were then tested statistically in the individual samples.

Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry

A Thermoquest/Finnigan Voyager GC/MS system with Xcalibur software (ThermoElectron Corp., San Jose, CA, U.S.A.) was used for all analyses. A Stabilwax column, 30 m × 0·32 mm with 1·0 μm coating (Restek Corp., Bellefonte, PA, U.S.A.), was used for separation and analysis of the volatiles extracted from the samples. The separation of volatile components used the following protocol: 60 °C hold for 4 min, followed by an increasing temperature ramp of 6 °C min-1 to 230 °C with a 40-min hold at this final temperature. The injection port was set at 230 °C. Helium carrier gas was used at a constant column flow rate of 2·5 mL min-1 throughout the analysis.

Data acquisition and operating parameters for the mass spectrometer were set as follows: scan rate 2 s-1; scan range m/z 40 to m/z 400; ion source temperature 200 °C; ionizing energy 70 eV. Identification of structures/compounds was performed using both the National Institute of Standards and Technology ‘02 library, as well as a visual comparison of unknown mass spectra with known compounds reported in the literature and comparisons of the mass spectra of commercially available standards with the unknowns. In addition, the retention times (RTs) of unknowns and standard compounds were measured relative to a series of ethyl esters.24 Standard chemicals for structure and RT confirmation were generally obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.).

Gas chromatography with flame photometric detection

A Finnigan 9001 gas chromatograph fitted with FPD was used for these analyses to detect sulphur compounds that might fall below the GC/MS detection limit. The FPD filter was set for 394 nm to detect only sulphur emissions. Injections of standard solutions of dimethyldisulphide and dimethylsulphone demonstrated detection levels of ≤ 0·001 ng. A Stabilwax column (30 m × 0·53 mm with 1·0 μm coating; Restek Corp.) was employed for separation. The injection was performed at an initial temperature of 60 °C; after a 4-min hold, the column was heated at a rate of 6 °C min-1 to a final temperature of 220 °C and kept there for 30 min.

Apocrine secretion odour-binding protein 1 and 2 analysis

Skin secretions were collected from the ‘sweaty’ backs of all subjects using cleaned, glass capillaries to scrap the skin surface gently. The filled capillary from each subject was placed in a 0·5-mL plastic microcentrifuge tube and stored cold (12 °C) until analysis. Skin proteins were washed from individual capillaries with ∼50 μL of buffer [containing 4% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 20% glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol and 0·125 mol L-1 Tris-HCl]. The samples collected belonged to four different ethnic groups (Caucasian, African American, Asian and Hispanic) and were pooled, based on gender and two age groups (young and old). This pooling was done to provide sufficient proteins for analyses. Age groups were arbitrarily constructed based on availability, with ‘young’ being age 19-40 years and ‘old’ being 41 years and older. Although four ethnic groups broken down by gender and age groups results in 16 cells, we were able to collect data to complete only nine of the cells. The characteristics of the nine pooled samples are shown in Table 1. Protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay25 on a BioMate 3 spectrophotometer (Thermo Electron Corporation, Madison, WI, U.S.A.).

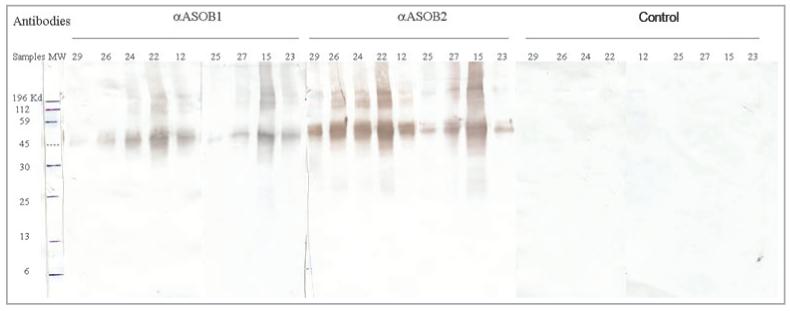

Skin proteins were separated using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.26 Four micrograms of protein were loaded into each well of 12% Tris-HCl precast polyacrylamide gels (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, U.S.A.). The electrophoresis system was the Mini-PROTEAN 3 system (Bio-Rad). Proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane in the Mini-PROTEAN II cell system (Bio-Rad). Western blots were developed using antibodies αASOB1 and αASOB2 at 1 : 1000 dilution and the Vectastain ABC kit guinea pig IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, U.S.A.) according to the described procedures.27,28 Blots were scanned and analysed using Adobe Photoshop (Adobe Systems Incorporated, San Jose, CA, U.S.A.). The Western blot is shown in Figure 1.

Fig 1.

Immunoreactivity to apocrine secretion odour-binding protein (ASOB) 1 and ASOB2 from human sweat secretion containing 4 μg each of protein collected from the back of each subject. Pooled samples belonging to nine different ethnic/age group categories were separated by 12% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and Western blotted. Proteins were developed using either immunopurified antibodies to ASOB1, ASOB2 or control (normal guinea pig antibody). Samples were coded as 29 (old Caucasian males), 26 (young Caucasian males), 24 (old Caucasian females), 22 (young Caucasian females), 12 (young Asian males), 25 (young Asian female), 27 (old African American males), 15 (young African American male) and 23 (young Hispanic female). The definition of ‘young’ or ‘old’ was as follows: young, 19-40 years; old, 41-79 years. Not all age and ethnic categories were available for testing.

Data analysis

Compounds found in each total ion chromatogram (TIC) were separately normalized in the following manner: the mass spectra of all peaks ∼1% above baseline were examined to eliminate, as best as possible, all components arising from siloxanes, room air, liquid soap, solvents, e.g. traces of chloroform, column and septa, as well as solvents commonly employed in cosmetic products and room air products, e.g. 2-butoxy ethanol. The intensities of all remaining components were normalized by dividing each of their intensities by the sum of all intensities for remaining compounds. This transformation is comparable with other normalization methods used in GC/MS data analysis, which generally normalize to the total intensity, e.g. by dividing extracted peak intensity values by the sum of intensity values for the chromatogram.29,30 However, although more tedious, our method is far less prone to the influence of outlier values from large exogenous components, as all obvious exogenous materials from unwanted sources are eliminated.

For each TIC, the relative percentages of selected compounds were calculated. The following compounds were examined for differences related to age, gender and emanation site: dimethylsulphone, benzothiazole, C8-C10 aldehydes, hexyl salicylate, α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde, isopropyl palmitate and methoxy acetic acid dodecyl ester. The primary reason these compounds were selected was the observation, via visual inspection of all TICs, that these compounds appeared to vary in many chromatograms. In addition, dimethylsulphone and benzothiazole were the two major sulphur compounds identified via GC/FPD. Further to this point, dimethylsulphone is a well-known metabolite in human body fluids and, in certain concentrations, this compound may be suggestive of abnormal methionine production.31 Analysis of the pooled extract samples (see Results) also suggested differences in the amounts of benzothiazole, methoxy acetic acid dodecyl ester and isopropyl palmitate attributed to age or emanation site. The exogenous compounds methoxy acetic acid dodecyl ester, isopropyl palmitate, hexyl salicylate and α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde were also of interest because of recent reports of similar compounds being noted as gender biomarkers.8,32,33 Finally, we were interested in the amounts of C8-C10 aldehydes because it has been suggested that they increase in concentration in the skin of older men.15

The relative amounts of each compound of interest were compared using repeated measures analysis of variance (anova) for each compound independently. Locus (back vs. forearm) was the repeated measures fixed factor; sex of the subject was a between-groups fixed factor, and age was a covariate. Subsequent to each overall anova, main effects of fixed factors and interactions were evaluated by calculating a Bonferroni adjusted P-value (P = 0·01). We report both univariate and Bonferroni significance. All analyses were performed using SPSS 11.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.).

Results

Room air/soap volatiles

Table 2 shows the compounds routinely seen in room air collections taken concomitantly with each subject. Table 3 lists the compounds found in the headspace above the soap being used in this study. Compounds in room air and soap were not included in Table 4, which lists volatiles from subjects.

Table 2.

Typical volatile organic compounds found in room air

| RT (min) | Compound assignment |

|---|---|

| 11·43 | 1-methyl-4-prop-1-en-2-yl-cyclohexene (limonene) |

| 13·75 | Trimethyl benzene |

| 16·43 | 2-butoxy ethanol |

| 17·76 | Dichlorobenzene |

| 18·15 | Silicon impurity |

| 21·13 | 2-(2-ethoxyethoxy) ethanol |

| 21·80 | Dihydrofuran-2(3H)-one (butyrolactone) |

| 24·61 | 2-(2-butoxyethoxy) ethanol |

| 26·18 | Unknown ester |

| 26·86 | Butylated hydroxytoluene |

| 29·43 | 3-phenoxy-1-propanol |

| 31·12 | 2-phenoxy-ethanol |

| 31·43 | Ethyl hexyl benzoate |

| 34·20 | Diethyl phthalate |

RT, retention time.

Table 3.

Typical volatile organic compounds found in the headspace of unfragranced soap

| RT (min) | Compound assignment |

|---|---|

| 10·38 | Unknown alkane |

| 12·03 | 3-dodecene |

| 15·35 | Unknown alkane |

| 19·21 | Methyl 4,6-decadienyl ether |

| 19·81 | Unknown alkane |

| 27·33 | 1-dodecanol |

RT, retention time.

Table 4.

Volatile organic compounds emanating from human skin via solid-phase microextraction (SPME) and solvent extract analysisa

| RT (min) | Characteristic ions | Compound assignmentb | SPME | Solvent extraction | EERIf |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4·82 | 43, 58 | 2-propanone (acetone)c | X | ||

| 10·80 | 41, 56 | 1-butanol | X | ||

| 11·49 | 42, 57, 100 | 4-ethyl-morpholinec,d | X | 5·25 | |

| 11·60 | 52, 79 | Pyridinec | X | X | 5·50 |

| 11·63 | 55, 59, 73 | 3-hexanolc | X | 5·57 | |

| 11·79 | 42, 55, 69, 98 | 2-methyl-cyclopentanonec | X | 5·63 | |

| 12·19 | 45, 69 | 2-hexanolc | X | 5·82 | |

| 12·37 | 42, 55, 69, 98 | 3-methyl-cyclopentanonec | X | 5·86 | |

| 12·58 | 43, 58, 71 | 1-methyl-cyclopentanolc | X | 5·93 | |

| 13·43 | 91, 119, 134 | p-cymene c | X | 6·42 | |

| 13·79 | 43, 56, 69, 84 | Octanalc | X | 6·60 | |

| 14·42 | 57, 67, 82 | 2-methyl-cyclopentanol | X | ||

| 14·72 | 45 | Lactic acid, methyl esterc | X | ||

| 14·81 | 43, 71 | 1,6-heptadien-4-olc | X | 6·99 | |

| 14·94 | 57, 71 | 3-methyl-cyclopentanolc | X | 7·06 | |

| 14·95 | 43, 108, 111 | 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-onec,e | X | X | 7·07 |

| 15·13 | 45, 56, 84 | 1-methoxy-hexane | X | ||

| 15·17 | 45, 75 | Ethyl (-)-lactatec | X | 7·12 | |

| 16·24 | 57, 70, 98 | Nonanalc | X | X | 7·64 |

| 16·96 | 57 | 1-octen-3-olc,e | X | X | 8·14 |

| 17·65 | 43, 60 | Acetic acidc,d,e | X | X | 8·28 |

| 18·03 | 59 | 2,6-dimethyl-7-octen-2-ol (dihydromyrcenol) c | X | 8·31 | |

| 18·15 | 57, 112 | 2-ethyl hexanolc,d | X | X | 8·55 |

| 18·64 | 43, 112 | Decanalc | X | X | 8·68 |

| 18·99 | 43, 99 | 2,5-hexanedionec | X | 8·78 | |

| 19·24 | 59 | 1-(2-methoxypropoxy)-2-propanol | X | X | |

| 19·42 | 81, 95 | 1,7,7-trimethylbicyclo[2·2·1]heptan-2-one (camphor) c | X | 8·92 | |

| 19·52 | 77, 106 | Benzaldehydec,d | X | 9·04 | |

| 19·56 | 71 | 3,7-dimethyl-1,6-octadien-3-ol (linalool) c | X | 9·11 | |

| 19·66 | 43, 87, 98 | 1-methyl hexyl acetate | X | ||

| 19·81 | 57, 73, 74 | Propanoic acidc | X | 9·14 | |

| 20·64 | 43, 55, 98 | 6-hydroxy-hexan-2-one | X | ||

| 20·68 | 54, 79, 107 | 4-cyanocyclohexenec,d | X | 9·45 | |

| 21·20 | 82, 138 | 3,5,5-trimethylcyclohex-2-en-1-one (isophoron) c | X | 9·70 | |

| 21·41 | 60, 73 | Butanoic acidc | X | 10·04 | |

| 21·67 | 71, 81, 95 | 2-(2-propyl)-5-methyl-1-cyclohexanol (menthol) c | X | 10·06 | |

| 22·23 | 97, 98 | Furfuryl alcohol c | X | 10·26 | |

| 22·28 | 77, 105 | 1-phenyl-ethanone (acetophenone)c | X | 10·30 | |

| 22·30 | 60, 87 | Isovaleric acidc | X | 10·44 | |

| 22·31 | 44, 62 | Ethyl carbamate (urethane) c | X | 10·46 | |

| 22·68 | 57, 67, 82 | 4-tert-butylcyclohexyl acetate (vertenex) c | X | 10·49 | |

| 22·98 | 59, 93, 121, 136 | p-menth-1-en-8-ol (alpha-terpineol) c | X | 10·64 | |

| 23·05 | 69, 82 | Dodecanalc | X | ||

| 23·06 | 104, 122 | 1-phenylethylester acetic acid | X | ||

| 23·50 | 69, 98 | 2(5H)-furanone, 3-methyl c | X | 10·94 | |

| 23·66 | 57, 70, 112, 127 | 2-ethylhexyl 2-ethylhexanoate | X | ||

| 24·26 | 67, 69 | 3,7-dimethyl-6-octen-1-ol (citronellol) c | X | 11·26 | |

| 25·40 | 45, 59, 89 | 1,1′-oxybis-2-propanolc,d | X | 11·92 | |

| 25·67 | 43, 55, 83, 98 | 3-hexene-2,5-diol | X | ||

| 25·68 | 69 | 3,7-dimethyl-2,6-octadien-l-ol (geraniol) c | X | 12·07 | |

| 25·77 | 60, 73, 87 | Hexanoic acidc | X | 12·20 | |

| 25·91 | 43, 69 | Geranylacetone 3 | X | X | 12·20 |

| 26·80 | 247 | 2,4,6-tri-tert-butyl-phenol | X | 12·49 | |

| 26·87 | 117, 124, 132 | Unknown | X | ||

| 27·02 | 233, 247 | 2,6-bis(1,1-dimethylethyl)-4-(1-oxopropyl)phenol | X | ||

| 27·06 | 91, 122 | Phenyl ethyl alcoholc,d | X | 12·79 | |

| 27·12 | 79, 94 | Dimethylsulphonec | X | 12·79 | |

| 27·57 | 73, 88 | 2-ethyl-hexanoic acid c | X | 13·16 | |

| 28·09 | 117, 132, 138 | Unknown | X | ||

| 28·44 | 108, 135 | Benzothiazolec | X | 13·32 | |

| 28·64 | 66, 94 | Phenolc,d | X | 13·70 | |

| 28·66 | 102, 228 | Tetradecanoic acid, 1-methylethyl ester (isopropyl myristate) c | X | X | 13·85 |

| 29·00 | 147, 175, 190 | 2-(4-tert-butylphenyl)propanal (p-tert-butyl dihydrocinnamaldehyde) | X | ||

| 29·51 | 60, 73 | Octanonic acidc | X | ||

| 29·56 | 189 | α-methyl-β-(p-tert-butylphenyl)propanal (lilial) | X | ||

| 29·62 | 103, 145 | 1,3-diacetyloxypropan-2-yl acetate (triacetin) | X | 14·29 | |

| 29·92 | 107, 108 | p-cresolc | X | 14·43 | |

| 30·60 | 95, 150, 151 | Cedrol c | X | 14·92 | |

| 31·47 | 45 | Lactic acidc | X | ||

| 32·12 | 102, 256 | Hexadecanoic acid, 1-methylethyl ester (isopropyl palmitate) c | X | X | |

| 32·29 | 120, 138 | 2-hydroxy, hexyl ester benzoic acid (hexyl salicylate) c | X | 15·77 | |

| 32·48 | 88, 101 | Palmitic acid, ethyl ester c | X | 16·00 | |

| 33·12 | 83, 153, 156 | Methyl 2-pentyl-3-oxo-1-cyclopentyl acetate (methyl dihydrojasmonate or hedione) | X | ||

| 33·71 | 243, 258 | 1,3,4,6,7,8-hexahydro-4,6,6,7,8,8-hexamethyl-cyclopenta-gamma-2-benzopyran (galaxolide) | X | ||

| 33·77 | 120, 138 | 2-ethylhexylsalicylate c | X | X | 16·60 |

| 33·90 | 43, 61 | Propane-1,2,3-triol (glycerin) c | X | 16·73 | |

| 33·91 | 45, 57 | Methoxy acetic acid, dodecyl ester | X | X | |

| 34·81 | 129, 216 | α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde c | X | X | 17·19 |

| 35·56 | 105, 122 | Benzoic acidc | X | 18·41 | |

| 36·19 | 60, 200 | Dodecanoic acidc | X | 18·41 | |

| 36·28 | 97, 126 | 5-(hydroxymethyl)-2-furaldehyde c | X | 18·65 | |

| 37·18 | 60, 109, 138 | Homomethylsalicylate | X | X | |

| 37·61 | 94 | 4-vinyl imidizole | X | ||

| 39·01 | 57, 71 | Methoxy acetic acid, tetradecyl ester | X | ||

| 39·79 | 60, 73, 214 | Tridecanoic acid | X | ||

| 42-43 | 129, 228 | Tetradecanoic acid | X | ||

| 48·61 | 129, 242 | Pentadecanoic acid | X | ||

| 55·33 | 129, 256 | Hexadecanoic acid | X | ||

| 58·00 | 55, 69, 83 | 9-hexadecanoic acid | X | ||

| 63·67 | 129, 279 | Heptadecanoic acid | X | ||

| 64·30 | 69, 81 | 2,6,10,15,19,23-hexamethyl-2,6,10,14,18,22-tetracosahexaene (squalene) | X | ||

| 64·76 | 104, 239, 300 | Hexadecanoic acid, 2-hydroxyethylester | X |

These compounds are seen in several subjects, but not all subjects.

Compounds in bold denote exogenous compounds; common names for some of the chemicals are italicized and in parentheses.

Retention time (RT) and mass spectrum were confirmed by injecting a standard solution of that compound into the gas chromatography/mass spectrometry system.

Occasionally observed in room air, but prevalent in a few of the subjects.

Exogenous and endogenous compounds (compounds used in flavour and/or fragrance industry, but also can be found occurring naturally in the body).

EERI, ethyl ester retention indices.

Qualitative analysis

Of the 92 compounds identified in the skin emanations (see Table 4), 58 were found in SPME samples and 49 were found in solvent extracts. Only 15 compounds were seen using both SPME and solvent extract analysis. Thus, the two sampling approaches are complementary, and both are important in obtaining a comprehensive profile of volatile, gas chromatographable metabolites. Qualitatively, the types of metabolites that could be collected were similar across individuals. As noted in Table 4, many of the compounds we identified can be attributed to exogenous sources.

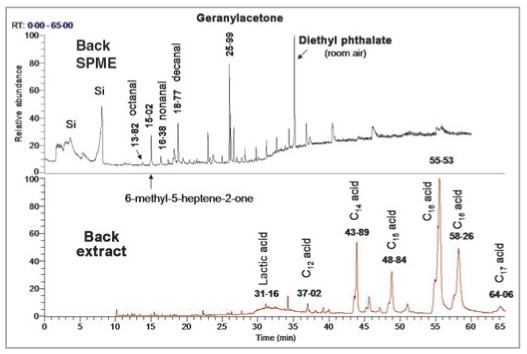

The C8-C12 aldehydes (odd and even carbon numbers) were present in the SPME analyses for almost every subject (Table 4, Fig. 2). Volatile acids in the C2-C6 ranges were seldom observed; only acetic acid was seen consistently. The presence of the ketones, 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one and geranylacetone, also was consistently observed across subjects.

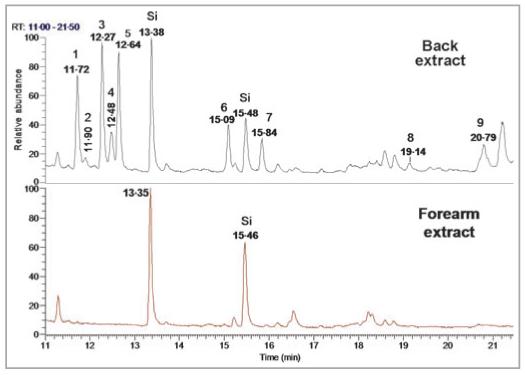

Fig 2.

Total ion chromatograms (TICs) from back solid-phase microextraction (SPME) (top) and solvent extract analysis (bottom) for a 19-year-old Caucasian male. Compounds in bold represent exogenous volatiles. Compounds labelled Si represent silicon containments (from SPME fibres or septa). The SPME-collected volatiles elute earlier in the chromatogram, whereas the compounds collected via solvent extraction are less volatile and elute later. Overlapping compounds are seen in the area between 15 and 37 min, but are not readily visible in the normalized TIC.

Solvent extraction primarily revealed the presence of large amounts of C12-C18 acids, and the C30 hydrocarbon, squalene (Table 4, Fig. 2). Also prominent was lactic acid, which appeared as a broad hump centred at about 30 min. The ketones, 6-methyl-5-heptene-2-one and geranylacetone, as well as the aldehydes, nonanal and decanal, also were found in the solvent extracts. Several low molecular weight alcohols and ketones in the C4-C8 range also were observed. Skin extracts appear to be better for securing higher molecular weight volatiles in the C8-C18 range.

Analysis of the solvent extracts by GC/FPD showed the presence of a few sulphur compounds, all in low concentrations. Two sulphur compounds, dimethylsulphone and benzothiazole, were identified and observed in several of the skin volatiles. The few other observable sulphur-containing compounds were not identifiable via GC/MS because of their low concentration (≤ 0·001 ng injected).

Protein analysis

Specific immunoreactivity to an ASOB1-like protein was observed at around 45 kDa when skin proteins were tested with antibodies to both ASOB1 and ASOB2, due to a cross reactivity which we have reported previously.22 Immunoreactivity to ASOB2, which should appear at around 20 kDa, was not observed (Fig. 1). No qualitative differences in pattern were observed between gender and age groups, but because all lanes were loaded with equal amounts of total protein there is the suggestion that one or more of the groups, such as lanes 25 and 29 for anti-ASOB1 and lanes 23 and 25 for anti-ASOB2, may display less immunoreactive ASOB1-like protein than others, regardless of age. Also present were higher molecular weight immunoreactive proteins (> 60-100 kDa), which may be dimers or trimers of the ASOB1-like protein.

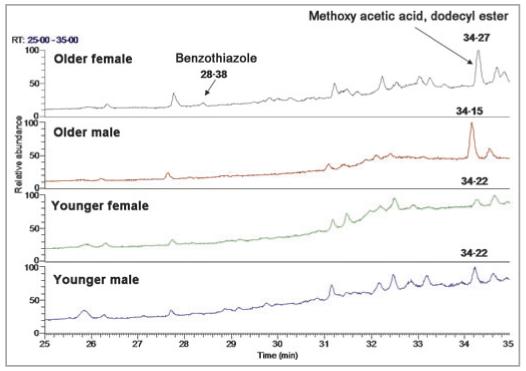

Pooled extract samples

Visual inspection of the TICs from the GC/MS analysis from pooled solvent extracts suggested several differences related to age and gender. The sulphur compound, benzothiazole (RT 28·44 min, GC/MS), was observed only in the pooled extract from the backs of older females (Fig. 3). The compound methoxy acetic acid dodecyl ester (RT 34·30 min) also was observed in this pooled extract (Fig. 3). This ester, which appears to be present in greater quantity in the pooled samples of older men and women, is most likely of exogenous origin and was observed in the younger subjects, albeit at a lower relative amount. Comparison of the male and female forearm extracts also suggested a quantitative difference in the exogenous compound isopropyl palmitate (RT 32·30 min): the pooled sample from females was estimated to contain about five times more than the pooled sample from males based upon the relative peak areas in the TICs of pooled samples.

Fig 3.

Comparison of total ion chromatograms from pooled back extracts. The portion of the chromatograms that is shown (25-35 min) highlights the area where the major differences were observed in the pooled samples.

Putative biomarkers of age and gender

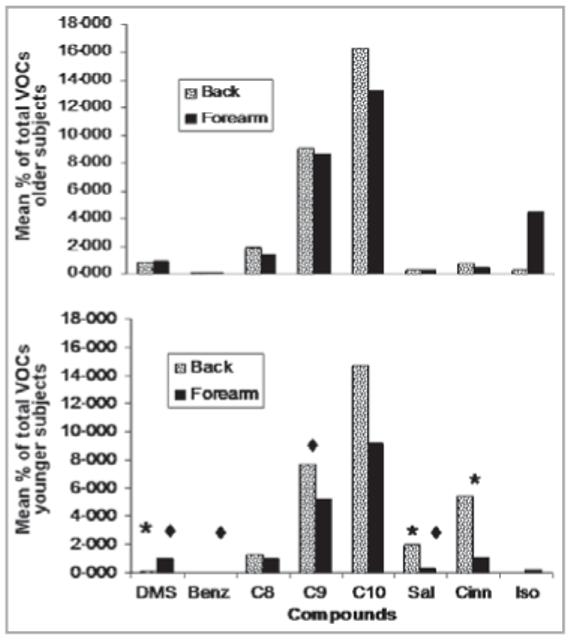

Relative amounts of the selected compounds, viz., dimethyl-sulphone, benzothiazole, C8-C10 aldehydes, hexyl salicylate, α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde, isopropyl palmitate and methoxy acetic acid dodecyl ester, were examined for any significant differences related to age, gender and emanation site (rationale for selection of compounds is explained in Materials and methods). No significant differences relating to gender were observed for any of the compounds present in either extract or SPME samples. Analyses of extracts also revealed no significant differences related to age; however, significant differences related to age were noted for five of the compounds examined via SPME-GC/MS.

Results of the statistical analyses for the compounds of interest via SPME-GC/MS can be found in Table 5 and Figure 4. Dimethylsulphone was observed in emanations from the backs and forearms of 13 of 25 and 18 of 25 subjects, respectively. Dimethylsulphone was more abundant in older subjects’ samples from the back, as compared with back samples from younger donors (Fig. 4, univariate P = 0·041 for locus; univariate P = 0·031 for age). Another sulphur compound, benzothiazole, was observed in emanations from the backs and forearms of 11 of 25 and seven of 25 subjects, respectively (mostly from older individuals: 14 of 18 benzothiazole-containing emanations), and was more concentrated in older subjects (Fig. 4, univariate P = 0·001). The aldehyde, nonanal, also was more abundant in older subjects (Fig. 4, univariate P = 0·042) and was found in both back and forearm samples of 25 of 25 and 21 of 25 subjects, respectively.

Table 5.

Statistical analysis of volatile organic compounds collected via solid-phase microextraction (SPME)-gas chromatography/mass spectrometry in which at least one component was significant or approached significance

| Compound (via SPME) | F(1,17) | P-valuec | Significant after correctiond | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimethylsulphone | Locusa | 4·908 | 0·041 | N |

| Age | 5·502 | 0·031 | ||

| Benzothiazole | Age | 15·619 | 0·001 | |

| Hexyl salicylate | Locus | 9·694 | 0·006 | Y |

| Age | 4·953 | 0·040 | ||

| Locus × ageb | 5·268 | 0·035 | N | |

| α-Hexyl cinnamaldehyde | Locus | 4·326 | 0·053 | N |

| Age | 3·528 | 0·078 | ||

| Nonanal | Age | 4·848 | 0·042 |

Locus denotes back vs. forearm.

Locus × age denotes locus interaction with age.

P ≤ 0·05 is significant.

Univariate P-values adjusted using the conservative Bonferroni correction.

Fig 4.

Mean percentages of selected compounds present in the back and forearm samples of younger (bottom graph) and older (top graph) subjects collected by solid-phase microextraction. The compounds in the top graph are the same as those listed along the x-axis of the bottom graph: DMS, dimethylsulphone; Benz, benzothiazole; C8, octanal; C9, nonanal; C10, decanal; Sal, hexyl salicylate; Cinn, α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde; Iso, isopropyl palmitate. *, compound in which locus was significant; ◆, compound for which age was significant.

No significant differences related to age or locus were found for octanal and decanal. Based only on viewing the mean concentration percentages (Fig. 4), it appeared as though there would be a significant difference in concentration related to locus for the exogenous compound isopropyl palmitate; however, no significant differences were observed. Upon inspection of the individual data, it was determined that one particular older individual had a very large quantity of isopropyl palmitate emanating from her forearm, skewing the overall mean percentage.

Two exogenous compounds, hexyl salicylate and α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde, however, were determined to be significantly or almost significantly greater in abundance in younger subjects via SPME-GC/MS. Hexyl salicylate was observed in 19 of 25 back samples and nine of 25 forearm samples; there was a significant (univariate P = 0·035, see Fig. 4) locus × age interaction. Older subjects had about the same amount of hexyl salicylate in their backs and forearms, whereas the percentage of this compound was greatly increased in the back samples of younger subjects. As a main effect, age also proved to be a significant covariant (univariate P = 0·040); overall, younger subjects had a higher amount of hexyl salicylate. α-Hexyl cinnamaldehyde was found in 19 of 25 back samples and nine of 25 forearm samples, and we noted a trend suggesting that younger subjects emit more hexyl salicylate than older subjects (Fig. 4, univariate P =0·078).

Comparison of back and forearm volatile organic compounds

Although many of the same volatile compounds were observed in both the back and forearm samples, statistical analyses of compounds in the SPME and extract collections revealed notable significant differences related to the site of emanation. In the SPME collections, we observed significant differences in the amount of three compounds related to emanation site: dimethylsulphone, hexyl salicylate and α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde. The latter two compounds are exogenous. In the SPME-GC/MS analysis, dimethylsulphone was more concentrated in the samples from the forearm (Fig. 4, univariate P = 0·041). Hexyl salicylate and α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde, however, were more abundant in the samples from the back, particularly from younger subjects (hexyl salicylate: Fig. 4, univariate P = 0·006; α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde: Fig. 4, univariate P = 0·053).

In the solvent extracts, there were nine compounds that were found only in the samples obtained from the back and were not observed in any individual’s extracts from the forearm. These VOCs are 3-hexanol, 2-methyl-cyclopentanone, 2-hexanol, 3-methyl-cyclopentanone, 1-methyl-cyclopentanol, 3-methyl-cyclopentanol, 1,6-heptadien-4-ol, 2,5-hexanedione and 6-hydroxy-hexan-2-one. These compounds were found in every extract from the backs of donors (25 of 25 subjects); an example is shown in Figure 5.

Fig 5.

Comparison of total ion chromatograms from back (top) and forearm (bottom) solvent extracts from a 40-year-old Asian woman. The portion of the chromatograms that is shown (11-21 min) highlights the area where the major differences were observed in the samples. The compounds are coded as follows: 1, 3-hexanol; 2, 2-methyl-cyclopentanone; 3, 2-hexanol; 4, 3-methyl-cyclopentanone; 5, 1-methyl-cyclopentanol; 6, 3-methyl-cyclopentanol; 7, 1,6-heptadien-4-ol; 8, 2,5-hexanedione; 9, 6-hydroxy-hexan-2-one. Compounds labelled Si represent silicon containments (from solid-phase microextraction fibres or septa).

Based on the pooled extract data, it seemed as though there might be significant differences in the extract data related to age or locus for the compounds benzothiazole, methoxy acetic acid dodecyl ester and isopropyl palmitate. Analysis of the relative peak areas, however, revealed no significant differences. Most extract samples contained little or no benzothiazole (as some of it was probably lost when the samples were concentrated), making statistical analysis difficult. A few individuals had an unusually high amount of the exogenous compounds methoxy acetic acid dodecyl ester and isopropyl palmitate, skewing the mean concentration percentage.

Discussion

Our study employed a comprehensive approach to the examination of the gas chromatographable components of two areas of human skin. Although we found significant differences across age and site of collection for certain compounds, no significant differences in the relative amounts of the compounds were seen between men and women.

Despite our protocol requiring subjects to use a fragrance-free soap/shampoo for 7-10 days prior to sampling, we still encountered considerable exogenous, consumer/product derived VOCs. This result is consistent with previous studies of human odours from our laboratory,34-36 as well as others8,14,33 and demonstrates a ubiquitous presence of exogenous VOCs. The copious use of fragranced consumer products results in numerous exogenous volatiles that are hard to reduce to undetectable levels using modern, sensitive instrumentation; our protocol may help diminish, but does not eliminate, these compounds. Some exogenous fragrance chemicals that were seen here differ significantly with age and locus of collection, suggesting either a storage or accumulation effect (such as in subcutaneous fat) or greater distribution due to how the product is used. Two recent studies8,33 have suggested that individuals can be characterized using apparent exogenous compounds, a weak supposition given the fact that individuals can and may frequently change their personal care products.

In this study, we used both visual inspection of our data (e.g. TICs from pooled samples and individual collections using SPME), as well as the rationale described in Materials and methods, to pick a group of potential biomarkers for gender, age and site of emanation. Statistical testing of these compounds showed some, but not all, of the compounds, to be indicative of age and/or body location. Remarkably, none of the compounds we chose differed significantly between men and women in our sample population (n = 25, 13 men and 12 women).

Our analysis of the skin VOCs identified a number of exogenous compounds from cosmetic products (see Table 4), and two of these compounds, hexyl salicylate and α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde, are found in numerous types of fragrances, soaps, shampoos and sunscreens.37 Both compounds were found to be significantly more concentrated in younger subjects, which may reflect greater product usage in younger populations.

Analyses of skin extracts revealed the presence of methylcyclopentanols, as well as 2- and 3-methylcyclopentanone. Although methylcyclopentanols have been reported in human urine and blood samples during studies of environmental pollutants and toxins affecting humans (Human Toxome Project),38 none of the other studies which examined human skin VOCs12-16 has reported these compounds. According to the Toxome project, these compounds are indoor pollutants (note: we did not see these chemicals in our room air samples) and are found in paint, lacquer removers and other industrial products. Cyclopentanone and substituted cyclopentanones are used as starting materials for many fragrances and pharmaceuticals.39 Jasmine-derived fragrances also contain substituted cyclopentenones, albeit with more complex sidechains (e.g. jasmone is 2-{(Z)-but-2-enyl}-3-methylcyclopenten-2-one). A possible alternative source for the cyclopentanones is the metal catalysed cyclization of amino adipic acid derivatives. The latter compounds may be formed via the oxidative degradation of terminal lysine from type I collagen.40 In addition, the body produces complex cyclopentenone prostaglandin structures.41 However, we have no direct evidence that any of these pathways lead to the methylcyclopentanones that we found on the skin.

Three compounds found to be biomarkers of increased age are dimethylsulphone, benzothiazole and nonanal. All three compounds were found to be significantly more abundant in older subjects. For all subjects, no method of analysis revealed the presence of the unsaturated C9 aldehyde, 2-nonenal, claimed to be the ‘odour of old age’ by Japanese investigators.15 It seems likely that the findings of the Japanese study might be a diet-linked, cultural phenomenon, which may not generalize to non-Japanese populations. The large consumption of fish and marine-based foods in the Japanese diet may lead to a build-up of unsaturated fatty acids and lipid peroxides with ageing. It is likely that 2-nonenal is generated by the oxidative degradation of ω7 unsaturated fatty acids.15 The ‘older’ subjects in the study by Haze et al.15 were > 39 years in age, similar to the ‘older’ subjects we sampled. As most western subjects in our subject pool will not have had a life-long history of consumption of marine products, we would not expect to see large amounts of unsaturated aldehydes, although saturated aldehydes were seen in all subjects. We did, however, see significantly greater amounts of nonanal (but not octanal or decanal) in older subjects (regardless of gender). The presumed pathway for production of this compound may be via lipid peroxidation from higher molecular weight unsaturated acids42 and may be upregulated in older individuals.43

Our data also strengthen the argument that different body areas can produce a qualitative and quantitative array of different compounds (for a review see Jenkins23). Solvent extracts revealed nine compounds that were observed only in the samples taken from the backs of donors. In the SPME samples, the different collection sites (back vs. forearm) contained significantly different amounts of dimethylsulphone and two exogenous compounds, hexyl salicylate and α-hexyl cinnamaldehyde. Dimethylsulphone was found to be greater in abundance in the forearm, while hexyl salicylate and a-hexyl cinnamaldehyde were found by SPME to be significantly more concentrated in samples from the back. These differences may reflect where/how consumer products are applied to the body. For example, compounds found in shampoo and conditioner will most likely be more abundant on the back than the forearm. The differences may also be attributed to the number/type of glands on different body areas, as well as the abundance of different bacteria on different body areas. Both the upper back and the forearm contain sebaceous glands, but these glands are much more concentrated on the upper back3 than the forearm; consequently, the back may have more sebum and may retain greater amounts of the lipophilic salicylate and cinnamaldehyde.

Protein analysis revealed no differences in pattern or immunoreactivity to ASOB1 based on gender or age. No immunoreactivity was seen for ASOB2. In a previous study, we found that an ASOB 1-like protein was present in several body fluids, as well as apocrine secretions.22 Consequently, the results presented here confirm the presence of an ASOB1-like protein in sweat from the back, perhaps facilitated by the presence of a serum-borne ASOB1-like protein which may carry odorants with it as proposed in earlier research.22

We conclude that the comprehensive approach used in this study is a successful means to examine the complete profile of gas chromatographable components of nonaxillary human skin. It was found that there are only small differences in skin VOCs related to age in healthy subjects. The greatest difference in the volatile skin profile stems from the site of emanation. The comprehensive research reported here could be valuable to people in the fragrance industry, as well as dog trainers.23 It is anticipated that our research will lead to the creation of a biomarker database for both healthy and malignant skin volatile components.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH (training grant T 32 DC00014-26). The authors thank the volunteers who participated in this study, as well as Mr Jason Eades and Mr Jefferson Plegaria for technical assistance. We also thank Mrs Kathleen Matt and Mr Keith McDermott of Symrise, Inc. for providing the liquid fragrance-free soap/shampoo. Finally, we are grateful to Drs Alan R. Willse and John Labows for reading earlier versions of this manuscript and their helpful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Farabee MJ. The integumentary system. In: Farabee MJ, editor. The On-Line Biology Book. 9th edn. Estrella Mountain Community College; Avondale, AZ: 2007. pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labows JN, McGinley KJ, Kligman AM. Perspectives on axillary odor. J Soc Cosmet Chem. 1982;34:193–202. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicolaides N. Skin lipids: their biochemical uniqueness. Science. 1974;186:19–26. doi: 10.1126/science.186.4158.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sato K, Kane N, Soos G, Sato F. The eccrine sweat gland; basic science and disorder of eccrine sweating. In: Moshell AN, editor. Progress in Dermatology. Dermatology Foundation; Evanston, IL: 1995. pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wysocki CJ, Preti G. Facts, fallacies, fears, and frustrations with human pheromones. Anat Rec. 2004;281A:1201–11. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.20125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Troccaz M, Starkenmann C, Niclass Y, et al. 3-Methyl-3-sulfanylhexan-1-ol as a major descriptor for the human axilla-sweat odour profile. Chem Biodivers. 2004;1:1022–35. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200490077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa Y, Yabuki M, Matsukane M. Identification of new odoriferous compounds in human axillary sweat. Chem Biodivers. 2004;1:2042–50. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200490157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Curran AM, Rabin SI, Prada PA, Furton KG. Comparison of the volatile organic compounds present in human odor using SPME-GC/MS. J Chem Ecol. 2005;31:1607–19. doi: 10.1007/s10886-005-5801-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zeng XN, Leyden JJ, Lawley HJ, et al. Analysis of characteristic odors from human male axillae. J Chem Ecol. 1991;17:1469–92. doi: 10.1007/BF00983777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zeng XN, Leyden JJ, Spielman AI, Preti G. Analysis of the characteristic human female axillary odors: qualitative comparison to males. J Chem Ecol. 1996;22:237–57. doi: 10.1007/BF02055096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bernier UR, Booth MM, Yost RA. Analysis of human skin emanations by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. 1. Thermal desorption of attractants for the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) from handled glass beads. Anal Chem. 1999;71:1–7. doi: 10.1021/ac980990v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernier UR, Kline DL, Barnard DR, et al. Analysis of human skin emanations by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. 2. Identification of volatile compounds that are candidate attractants for the yellow fever mosquito (Aedes aegypti) Anal Chem. 2000;72:747–56. doi: 10.1021/ac990963k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernier UR, Kline DL, Schreck CE, et al. Chemical analysis of human skin emanations: comparison of volatiles from humans that differ in attraction of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2002;18:186–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang ZM, Cai JJ, Ruan GH, Li GK. The study of fingerprint characteristics of the emanations from human arm skin using the original sampling by SPME-GC/MS. J Chromatogr B. 2005;822:244–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haze S, Gozu Y, Nakamura S, et al. 2-Nonenal newly found in human body odor tends to increase with aging. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:520–4. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ostrovskaya A, Landa PA, Sokolinsky M, et al. Study and identification of volatile compounds from human skin. J Cosmet Sci. 2002;53:147–8. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baydar A, Charles A, Decazes JM, et al. Behavior of fragrances on skin. Cosmet Toiletries. 1996;111:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Behan JM, MacMaster AP, Perring KD, Tuck KM. Insight into how skin changes perfume. Int J Cosmet Sci. 1996;18:237–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2494.1996.tb00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mookherjee BD, Patel SM, Trenkle RW, Wilson RA. A novel technology to study the emission of fragrance from the skin. Perfum Flavor. 1998;23:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soini HA, Bruce KE, Klouckova I, et al. In situ surface sampling of biological objects and preconcentration of their volatiles for chromatographic analysis. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7161–8. doi: 10.1021/ac0606204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyden JJ, Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ. Cutaneous microbiology. In: Goldsmith LA, editor. Physiology, Biochemistry, and Molecular Biology of the Skin. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 1991. pp. 1403–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spielman AI, Zeng XN, Leyden JJ, Preti G. Proteinaceous precursors of human axillary odor: isolation of two novel odor binding proteins. Experientia. 1995;51:40–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins SH. Can police dogs identify criminal suspects by smell? Using experiments to test hypotheses about animal behavior. In: Jenkins SH, editor. How Science Works: Evaluating Evidence in Biology and Medicine. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 36–51. [Google Scholar]

- 24.van den Dool H, Kratz H. A generalization of the retention index system including linear programmed gas liquid partition chromatography. J Chromatogr. 1963;11:463–71. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(01)80947-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of proteindye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci U.S.A. 1979;76:4350–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.9.4350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spielman AI, Sunavala G, Harmony JAK, et al. Identification and immunohistochemical localization of protein precursors to human axillary odors in apocrine glands and secretions. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:813–18. doi: 10.1001/archderm.134.7.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alltech Associates, Inc. [last accessed 12 May 2008];Area Percent Method. 1998 Available at: http://www.discoverysciences.com/productinfo/Technical/edu/edu399p10-11.pdf.

- 30.Palmer PT. Gas chromatography/mass spectrometry. In: Meyers RA, editor. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry: Applications, Theory, and Instrumentation. John Wiley & Sons; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 11737–8. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Engelke UFH, Tangerman A, Willemsen MAAP, et al. Dimethyl sulfone in human cerebrospinal fluid and blood plasma confirmed by one-dimensional 1H and two-dimensional 1H-13C NMR. NMR Biomed. 2005;18:331–6. doi: 10.1002/nbm.966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curran AM, Ramirez CF, Schoon AA, Furton KG. The frequency of occurrence and discriminatory power of compounds found in human scent across a population determined by SPME-GC/MS. J Chromatogr B. 2008;846:86–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Penn DJ, Oberzaucher E, Grammer K, et al. Individual and gender fingerprints in human body odour. J R Soc Interface. 2007;4:331–40. doi: 10.1098/rsif.2006.0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Labows J, Preti G, Hoelzle E, et al. Analysis of human axillary volatiles: compounds of exogenous origin. J Chromatogr. 1979;163:294–9. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)81417-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kostelc JG, Preti G, Zelson PR, et al. Volatiles of exogenous origin from the human oral cavity. J Chromatogr. 1981;226:315–23. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)86065-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Preti G, Labows JN, Kostelc JG, et al. Analysis of lung air from patients with bronchogenic carcinoma and controls using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr. 1988;432:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(00)80627-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.International Flavors and Fragrances Inc. [last accessed 12 May 2008];Fragrance Ingredients. 2008 Available at: http://www.iff.com/Ingredients.nsf/FragIngredients!OpenForm.

- 38.Environmental Working Group [last accessed 12 May 2008];Human Toxome Project. 2008 Available at: http://www.bodyburden.org/

- 39.Renz M, Corma A. Ketonic decarboxylation catalysed by weak bases and its application to an optically pure substrate. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:2036–9. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sell DR, Strauch CM, Shen W, Monnier VM. 2-Aminoadipic acid is a marker of protein carbonyl oxidation in the aging human skin: effects of diabetes, renal failure and sepsis. Biochem J. 2007;404:269–77. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Musiek ES, Breeding RS, Milne GL, et al. Cyclopentenone isoprostanes are novel bioactive products of lipid oxidation which enhance neurodegeneration. J Neurochem. 2006;97:1301–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Orhan H, van Holland B, Krab B, et al. Evaluation of a multi-parameter biomarker set for oxidative damage in man: increased urinary excretion of lipid, protein and DNA oxidation products after one hour of exercise. Free Radical Res. 2004;38:1269–79. doi: 10.1080/10715760400013763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spiteller G. Lipid peroxidation in aging and age-dependent diseases. Exp Gerontol. 2001;36:1425–57. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(01)00131-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]