Abstract

A persistent translation arrest (TA) correlates precisely with the selective vulnerability of post-ischemic neurons. Mechanisms of post-ischemic TA that have been assessed include ribosome biochemistry, the link between TA and stress responses, and the inactivation of translational components via sequestration in subcellular structures. Each of these approaches provides a perspective on post-ischemic TA. Here we develop the notion that mRNA regulation via RNA binding proteins, or ribonomics, also contributes to post-ischemic TA. We describe the ribonomic network, or structures involved in mRNA regulation, including nuclear foci, polysomes, stress granules, ELAV/Hu granules, processing bodies, exosomes and RNA granules. Transcriptional, ribonomic and ribosomal regulation together provide multiple layers mediating cell reprogramming. Stress gene induction via the heat shock response, immediate early genes, and endoplasmic reticulum stress represents significant reprogramming of post-ischemic neurons. We present a model of post-ischemic TA in ischemia-resistant neurons that incorporates ribonomic considerations. In this model, selective translation of stress-induced mRNAs contributes to translation recovery. This model provides a basis to study dysfunctional stress responses in vulnerable neurons, with a key focus on the inability of vulnerable neurons to selectively translate stress-induced mRNAs. We suggest a ribonomic approach will shed new light on the roles of mRNA regulation in persistent TA in vulnerable post-ischemic neurons.

1. Introduction

A persistent translation arrest (TA) correlates with the delayed neuronal death (DND) of vulnerable neurons following brain ischemia and reperfusion (I/R), but the mechanisms and significance are still not fully understood. We and others have proposed an intimate relationship between post-ischemic TA and I/R-induced intracellular stress responses (Paschen, 1996; Martin de la Vega et al., 2001; DeGracia et al., 2002; DeGracia and Hu, 2007). Translation recovery occurs with successful execution of stress responses in resistant neurons, while persistent TA is associated with stress response failure in vulnerable neurons. Advances in the understanding of mRNA regulation, or “ribonomics” (Tenenbaum et al., 2002), offer new avenues by which to understand the role of TA in post-ischemic stress responses. In this article we: (1) outline previous studies of post-ischemic TA, (2) summarize the current understanding of ribonomics, (3) introduce ribonomic considerations into issues of post-ischemic TA and stress responses, and (4) present a ribonomic model of the relationship between post-ischemic stress responses and TA, with the intent to stimulate further work in the area. We aim to illustrate that many different regulatory layers bear on the relationship between post-ischemic stress responses and translation, and hence, outcome.

2. Post-ischemic Translation Arrest

Following the initial characterization of post-ischemic TA, specific ideas have guided this area including: focus on ribosome biochemistry, the relationship between TA and stress responses, and the idea that ribosomes are sequestered in nonproductive complexes. Here we briefly summarize the main results stemming from each line of inquiry.

Initial investigations of post-ischemic TA resulted in three core observations (Hossmann, 1993): (1) TA occurred initially in all post-ischemic brain regions, and gradually recovered (e.g. was reversible) in resistant regions, but persistent TA correlated exactly with DND of vulnerable neurons, such as CA1 in global ischemia models, (2) polysomes disaggregated with the onset of reperfusion, implicating inhibition of translation initiation, and (3) persistent TA prevented translation of stress-induced transcripts, specifically immediate early genes (IEGs, also called early response genes or ERGs) and heat shock proteins (HSPs), in vulnerable brain regions (summarized in Nowak, 1990). This latter point provided the initial link between post-ischemic TA and stress responses. While it was known that heat shock caused a transient TA and selective translation of HSPs (Lindquist, 1986), the possibility of a causal connection between I/R-induced stress responses and TA had not been clearly deduced at this point. Instead, transcriptional and translational changes in post-ischemic brain were viewed as distinct processes, in which TA was a downstream barrier to upstream changes in gene programming.

A. Ribosome Biochemistry

The observation that polysomes disaggregate in reperfused neurons led to focus on the biochemistry of I/R-induced changes to translation initiation (detailed reviews are in DeGracia et al., 2002; DeGracia, 2004). This line of study established that: (1) phosphorylation of the alpha subunit of eIF2 [eIF2α; phospho-form, eIF2α(P); phospho-holoform eIF2(αP)], which inhibits translation initiation (Clemens, 2001), occurred rapidly with reperfusion, but also that eIF2α(P) dephosphorylated in all post-ischemic neurons well before DND. (2) eIF4G degraded as a function of ischemia duration. (3) Alterations were identified in other ribosome regulators such as phosphorylation changes of eIF4E, eIF4G, 4E-BPs, S6 kinase, and eEF2 (DeGracia, 2004). The most recent work in this area has demonstrated intriguing changes in binding partners with the eIF2α phosphatase PP1 suggesting inhibition of this protein by chaperones (García-Bonilla et al., 2007).

The consensus has emerged that TA in both vulnerable and resistant regions is not fully accounted for by eIF2α(P) (Martin del al Vega et al., 2001; Althausen et al., 2001; DeGracia, 2004). Perhaps the most striking demonstration of this point are recent observations in conditional PERK knockouts lacking PERK in the brain (Owen et al., 2005). In this study, levels of eIF2α(P) in reperfused knockout mice were only 25% of that in wild type nonischemic controls, but brain homogenates from the PERK knockouts still displayed decreases of 35% and 24% of in vitro translation and initiation, respectively. These results clearly point to mechanisms other than eIF2(αP) contributing to post-ischemic TA. However, the roles of biochemical changes in ribosome regulators to this day remain uncertain. It is possible that changes in classical biochemical pathways of translation regulation reflect other, as yet not fully appreciated, genetic reprogramming processes occurring in reperfused neurons, a point to which we return below.

B. TA and Stress Responses

A number of discoveries indicated that stress responses actively induce TA (Brostrom and Brostrom, 1998; Kaufman, 1999). The first application of this viewpoint to studies of brain I/R was the suggestion that post-ischemic TA was a marker of endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress (Paschen, 1996). However, while the post-ischemic heat shock response (HSR) and IEG transcriptional reprogramming have been repeatedly validated, subsequent work has failed to convincingly demonstrate expression of the classic ER stress response, the unfolded protein response (UPR, discussed in detail in DeGracia and Hu, 2007 and Roberts et al., 2007). Uncertainty exists about the degree of translation of downstream UPR effectors such as 55 kDa XBP-1 and CHOP (Roberts et al., 2007). A lack of significant increases in ER-stress induced proteins has been attributed to the persistent TA in vulnerable neurons (Paschen, 2003), similar to the earlier observations of lack of translation of HSPs and IEG protein products.

Following on the suggestions that eIF2α phosphorylation represented a “classical stress response” (Martin de la Vega et al., 2001), we developed the notion that post-ischemic TA was an integral subroutine in the post-ischemic stress responses (DeGracia and Hu, 2007). Here we divided TA into initiation, maintenance and termination phases. Initiation of TA involved ribosome regulation, maintenance of TA involved mRNA regulation, and termination of TA (e.g. translation recovery) was coupled to the selective translation of stress gene products. This model was a precursor to the one we present below, and contained the first intimation of applying ribonomic concepts to the problem.

C. Ribosomal Sequestration

Further work has indicated that, in addition to the classical mechanisms of ribosome inhibition, I/R injury results in sequestration of ribosomes in unproductive complexes, precluding translation (reviewed in DeGracia and Hu, 2007). This approach is rooted in earlier studies showing accumulation of cytoplasmic inclusion in vulnerable neurons at later reperfusion (Kirino and Sano, 1984; Deshpande et al., 1992). Two general classes of structures have so far been identified that involve sequestration of translational components: (1) structures containing ubiquinated proteins, (2) structures related to mRNA metabolism. Here we briefly review results with ubiquinated structures, and return studies of mRNA-related structures after introducing ribonomic concepts.

Two types of structures containing ubiquinated proteins have been detected in reperfused neurons: ubiquinated (ubi-) protein clusters, and protein aggregates (PAs) (Hu et al., 2000; reviewed in DeGracia and Hu, 2007). The former occur in all post-ischemic neurons, are relatively large (~2 microns) and are reversible. PAs occur only in vulnerable neurons, are small (~ 250 nm) and are irreversible. PAs have been proposed to sequester translational machinery. Called “cotranslation aggregation”, this model proposes that improper folding of nascent peptides leads to trapping of ribosomes in PAs (DeGracia and Hu, 2007). Ribosomal subunit proteins, initiation factors, and cotranslational chaperones were detected in the PA-containing, detergent insoluble fraction from cortical homogenates following a 20 min ischemic insult that produced DND in the cortex (Liu et al., 2005). At 24 h reperfusion, the amount of ribosomal subunit proteins sequestered represented a 15% decrease in ribosomes in the microsome fraction, and the decrease in ribosomes of the cytosolic fraction was not determined. HSC70 and HSP40 (Hdj1) decreased 40% and 85% in the cytosolic fraction at 24 h reperfusion, concurrent with a rise in the amount of these proteins in the PA fraction.

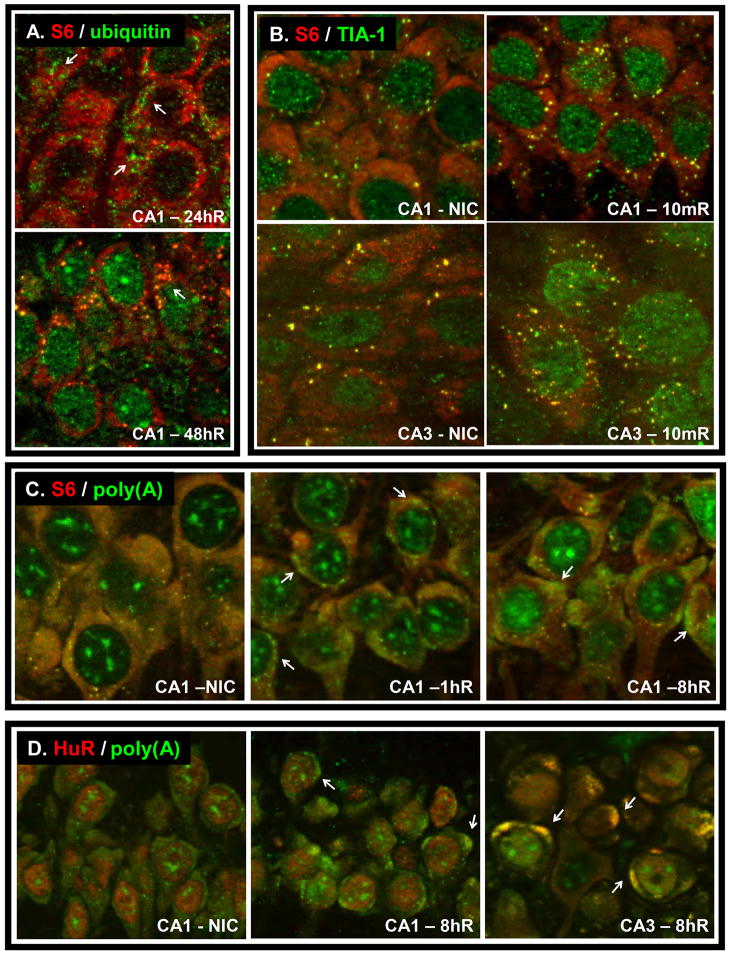

When we co-stained for ubiquitin and the 40S protein S6, the ubi-protein clusters (Figure 1A top panel) at earlier reperfusion did not substantially colocalize with S6 (red staining) (DeGracia et al., 2007). At later reperfusion, S6 and ubiquitin colocalized as punctate particles, and these also colocalized with the mRNA regulatory protein TIA-1. TIA-1 is a canonical component of mRNA-containing structures called stress granules (SGs, see below), suggesting that a hybrid particle of PAs and SGs forms late in reperfusion in vulnerable neurons (Figure 1A bottom panel). Recently, HDAC-6 has been shown to enter SGs along with ubiquinated proteins (Kwon et al., 2007) raising the possibility that the presence of ubiquitin we observed in reperfused CA1 SGs may be physiological and not nonspecific. As can be seen in Figure 1A, ubiquitin/S6 colocalizations represent only a fraction of total S6 cytoplasmic staining. Thus, present data indicates that some proportion of ribosomes deposit in PAs but there is not a wholesale, quantitative sequestration of ribosomal subunits in ubiquinated aggregates.

Figure 1.

“Particles” in reperfused neurons. (A) Costaining for ribosomal protein S6 and ubiquitin in CA1. Arrows point to ubi-protein clusters in 24 h reperfusion sample, and protein aggregates in 48 h reperfused sample. (B) Costaining for TIA-1 and S6 in nonischemic control (NIC) or 10 min reperfused (10mR) CA1 and CA3 showing the increase in the number of SGs (yellow cytoplasmic punctate colocalizations). (C) Costaining of polyadenylated mRNAs [poly(A)] and the 40S subunit protein S6 in CA1 of NIC and after 1 and 8 h reperfusion. Arrows point to mRNA granules, which do not colocalize with S6. (D) Poly(A) and HuR costaining in NIC CA1, and CA1 and CA3 after 8 h reperfusion. HuR colocalized to mRNA granules in CA3 but not CA1 (arrows). Staining and microscopy as described in Kayali et al. (2005), DeGracia et al. (2007), and Jamison et al. (2008). For all panels, pixel scaling in x, y and z is 0.10, 0.10, and 0.35 microns, respectively. All reperfused samples were acquired following 10 min 2VO/HT ischemia, and reperfusion times (R) as designated.

We have identified two subcellular structures in reperfused neurons that could serve to sequester translational components: SGs and aggregates that contain eIF4G, poly(A) binding protein and mRNAs. As both are intimate components of the ribonomic network, we first describe the ribonomic network, and then return to a discussion of these structures in post-ischemic neurons.

3. The Ribonomic Network

While it is widely known that mRNA is transcribed and processed in the nucleus then transported to the cytoplasm for translation on ribosomes, continuing research has demonstrated the intrinsic complexity of these processes. First we outline the general structure of mRNA, and then present a cell physiologic view of the ribonomic network. The ribonomic network is the set of subcellular structures involved in mRNA-related functions (Tenenbaum et al., 2002).

A. mRNA Structure

Variations in structural elements of matured eukaryotic mRNA allow for a large diversity of mRNA regulatory control. The 5′ 7-methylguanosine cap is the target of eIF4F, the translation initiation factor that positions the 40S subunit at the start codon (Gingras et al., 1999). Beyond its role in translation initiation, the cap binding protein eIF4E can mediate mRNA silencing, for example, via interactions with Cup and Bruno during Drosophila oogenesis (Nakamura et al., 2004), or with maskin during neuronal activity-dependent translation (Richter and Sonenberg, 2005).

The 5′ untranslated region (UTR) is a variable length, noncoding region that plays substantial roles in mRNA regulation (Pickering and Willis, 2005). While length and secondary structure are determinants of scanning efficiency (Pickering and Willis, 2005), cis-acting sequences in the 5′UTR determine nonclassical forms of initiation. Upstream open reading frames mediate bypass scanning/internal reinitiation (Hinnebusch, 1993). Internal ribosome entry sites (IRES) mediate a form of cap-independent initiation, internal ribosome entry (Pisarev et al., 2005). The presence of tripartite leaders allows for ribosome shunting (Chappell et al., 2006). 5′UTR sequences can also confer specificity in translation. For example, the 5′ terminal oligopyrimidine tract (5′TOP), present in mRNAs coding for translational machinery, confers translation in growing cells, but silences translation in quiescent cells (Hamilton et al., 2006).

Following the coding region and termination codon is a 3′UTR that, like the 5′UTR, is a variable length noncoding region that also can contain cis-acting sequences (Hesketh, 2004). A well studied example is the adenine and uridine rich element (ARE), which consists of 4 classes of functionally related sequences (Bakheet et al., 2001). AREs regulate mRNA stability, often conferring rapid degradation of the mRNA (Barreau et al., 2006). Examples of ARE-containing mRNAs are IEGs, cytokines, interferons and growth factors (Keene and Lager, 2005). It has been estimated that perhaps 5%-8% of all human mRNAs contain ARE sequences (Kahabar, 2005).

Most eukaryotic mRNAs possess a homopolymeric polyadenylated [poly(A)] tail. Through poly(A) binding protein (PABP) interactions with the eIF4G subunit of eIF4F, the poly(A) tail participates in circularization of mRNA in polysomes (Wells et al., 1998), enhancing initiation (reviewed in Mangus et al., 2003). The poly(A) tail also participates in mRNA regulation. For example, poly(A) tail shortening couples translation and degradation (Mangus et al., 2003).

The 5′ cap, the poly(A) tail and cis-acting sequences in the 5′ and 3′ UTRs, but not necessarily confined therein, can participate in specific trans interactions with protein binding partners or with micro-RNAs. Such binding interactions are the basis for mRNA participation in macromolecular complexes.

B. Subcellular Structures Involved in mRNA Regulation

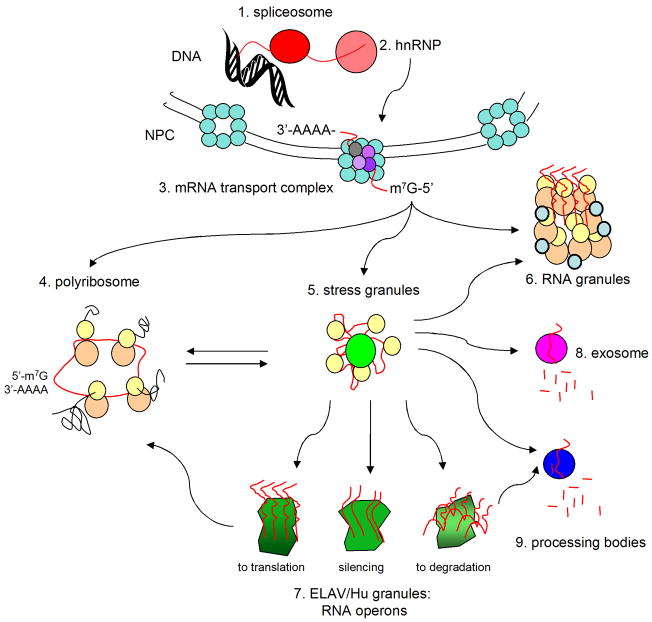

From birth to death an mRNA molecules assumes a variety of different protein “wardrobes” (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006), generating messenger ribonucleoprotein particles (mRNPs). The mRNPs can form relatively large foci in cells, often visible by light microscopy. To date, close to a dozen such foci have been identified. Figure 2 shows nine of these foci, portraying their integrated functioning in the flow of mRNA (or mRNA flux) from biogenesis to degradation. Clearly, we cannot comprehensively review each of these here, and the reader is referred to the cited literature for more detailed information. Here, we present a cell physiologic view in which all of these structures together constitute the ribonomic network, or set of structures through which mRNA flux occurs (Keene, 2001; Keene and Lager, 2005; Keene, 2007). Major functions of the ribonomic network include mRNA biogenesis (e.g. transcription and processing), routing (or transport), silencing (or storage), translation, and degradation. Each network structure provides layers of regulation that can affect cell programming via expression, or lack thereof, of specific proteins.

Figure 2.

The ribonomic network. Processing of mRNA transcripts (red lines) occurs at spliceosomes and at hnRNPs that cap and add the poly(A) tail. Transport complexes move mature mRNA through the nuclear pore complex (NPC) to the cytoplasm. In polysomes, mRNAs are translated (40S, yellow; 60S orange circles). Stress granules route mRNAs to other mRNPs. In exosomes and P-bodies, mRNAs are degraded. RNA granules route mRNA and ribosomes to synapses. In ELAV/Hu granules, mRNAs are sequestered together into structural and functional groups of RNA operons that are coordinately silenced, translated or degraded.

a. Nuclear mRNA Handling

mRNA biogenesis, as is well appreciated, results from nuclear DNA transcription and is the end product of many possible upstream signaling pathways. Dedicated mRNPs are involved at each stage of nuclear mRNA handling. Spliceosomes remove introns and ligate exons of newly transcribed mRNA (Valadkhan, 2007). Heavy nuclear ribonucleoprotein complexes (hnRNPs) contribute to polyadenylation, capping, and nuclear to cytoplasmic transport (Carpenter et al., 2006). While general mRNA transport complexes route mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Steward, 2007), some mRNAs, notably heat shock-induced mRNAs (Bond, 2006), may export via specific transport complexes.

b. Polysomes

Polysomes, of course, convert the mRNA genetic information to protein. In the context of the ribonomic network, polysomes are increasingly being viewed as one mRNP amongst many that form or un-form on the basis of cell needs (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006). Translation or lack thereof depends on cell context. Sometimes the silencing of mRNA is critical to cell programming, for example, in mRNA packaging during oogenesis (King et al., 2005) or, as elaborated below, during cell stress.

Regulation of translation can occur at both the ribosomes and at the mRNA. Ribosomal regulation occurs mainly via control of initiation, but elongation or termination control also occur (Mathews et al., 2000). Ribosome regulation results in quantitative control over protein production rates (Mathews et al., 2000). Regulation of mRNA occurs through regulation of the ribonomic foci, creating a multilayered system that determines mRNA access to the ribosomal machinery. Regulation of mRNA is qualitative in the sense that access of specific mRNAs to the ribosomes sets the phenotype of the cell by determining the proteome.

c. Stress Granules

Stress granules (SGs) occur in a large variety of metazoan cell types, elicited by a large variety of stressors. They contain a variant 48S preinitiation complex, mRNAs, and a growing list of proteins involved in mRNA binding, self-assembly, and signal transduction (reviewed in Anderson and Kedersha, 2008). SGs are in equilibrium with polysomes (Kedersha et al., 2000), and form rapidly when translation initiation is inhibited (Kedersha et al., 1999; Dang et al., 2006). SGs are highly dynamic entities that play a central role in the routing of mRNA amongst the ribonomic foci, e.g. “mRNA triage” (Kedersha et al., 2005). While SGs were initially identified in the context of cell stress, it is now thought that the visible SGs formed following stress represent an extreme case of particles that are constitutive to unstressed cells, and function to mediate mRNA flux (Anderson and Kedersha, 2008).

d. ELAV/Hu Granules

Major changes in cell physiology, such as differentiation or cell stress can elicit the formation of another mRNA-containing structure, the embryonic lethal abnormal vision (ELAV)/Hu granules (Antic and Keene, 1998). Hu proteins, the mammalian homologs of Drosophila ELAV, are important components of these structures. HuR (also called HuA) is ubiquitously expressed whereas HuB, HuC and HuD are neuron specific (Burry and Smith, 2006). Hu proteins bind and stabilize ARE-containing mRNAs (Brennan and Steitz, 2001).

Via participation in ELAV/Hu granules, Hu proteins play a role in partitioning functionally or structurally related classes of mRNA into a cohort, providing for their coordinated handling (Keene, 2007). Analogous to the combinatorial model of transcription factors, specific combinations of mRNA binding proteins are thought to partition functional and/or structurally related mRNAs (Keene and Lager, 2005; Keene, 2007). Partitioning of mRNA cohorts has been termed an “RNA operon”, by analogy to prokaryotic operons that allow for simultaneous expression of a functionally related set of proteins (Keene and Lager, 2005; Keene, 2007). The composition of ELAV/Hu granules has been less well characterized compared to SGs, but they contain eIF4G, eIF4E, PABP, and Hu proteins as well as mRNA (Tenenbaum et al., 2002).

Figure 2 depicts ELAV/Hu granules downstream from the routing function of SGs. SGs may serve to route mRNAs into functionally distinct ELAV/Hu granules, each containing a different RNA operon. The ELAV/Hu granules serve to coordinate the activity of mRNA cohorts, in terms of targeting them for simultaneous translation, silencing, or degradation (Figure 2). By this means, control of different mRNA cohorts contributes to the execution of complex cell physiologic programs such as stress responses, differentiation, or cell cycle regulation. RNA operons offer a speed and flexibility in genetic reprogramming that cannot be achieved at the level of transcriptional regulation (Keene, 2007).

e. Processing Bodies and Exosomes

Both of these foci play roles in mRNA degradation. Neither structure contains ribosomal subunits, but may contain initiation factors (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006). Processing bodies (P-bodies) contain 5′-3′ exonucleolytic activity and some of the RNA silencing machinery (Stoecklin and Anderson, 2007). P-bodies can serve both as sites of mRNA silencing or decay (Brengues et al., 2005; Teixeira and Parker, 2007). The exosome contains the 3′-5′ exonuclease machinery that degrades uncapped and deadeneylated mRNAs (Schwartz and Parker, 2000). Degradation of mRNA as a means of translation regulation is well documented (Laroia et al., 1999). Examples include IEGs c-fos and c-myc, (Barreau et al., 2005) or the hsp70 mRNA (Lindquist, 1986), which are destabilized by cis-acting elements in their 3′UTRs that link translation to degradation (Grosset et al., 2000), and provide the basis for the regulated half life of these transcripts.

f. RNA Granules

RNA granules contain translationally inactive mRNAs and ribosomes, and a growing list of other proteins, including the mRNA silencing proteins staufen (Villacé et al., 2006) and fragile X mental retardation protein (Ferrari et al., 2007). RNA granules transport mRNAs and ribosomes from the cytoplasm to distal processes, allowing for activity-dependent translation at individual synapses (Krichevsky and Kosik, 2001). Similar translationally inactive mRNA storage granules are present in maternal germ cells (Anderson and Kedersha, 2006). In the scope of the present article it is obviously necessarily to consider RNA granules as intimate components of the neuronal ribonomic network. However, their role in post-ischemic translation control is all but unknown at present.

C. The Central Dogma in 3D

DNA giving rise to mRNA giving rise to proteins has conjured up a linear, sequential concept of these processes. However, it is now well accepted that the ribonome, or set of mRNAs in a cell, does not correlate with the proteonome, or set of proteins in a cell (Nie et al., 2007). In part, this is because mRNA must flow through the ribonomic network before gaining access to the ribosomes. Thus, mRNA is not simply a passive middle-man between DNA and proteins. The ribonomic network results in a complex, highly regulated flux of mRNA through the three dimensional structures discussed above. While regulation of transcription and ribosomes are both widely appreciated, the role of mRNA regulation in cell programming is becoming increasingly apparent. It may turn out that active regulation of mRNA via ribonomic structures is of equal or greater complexity, given the heterogeneity of mRNA molecules and the diversity of mRNPs (Keene, 2007).

Therefore, genetic programming of cell phenotype includes three broad layers: (1) transcriptional regulation, (2) ribosomal regulation, and (3) regulation of mRNA within the ribonomic network. These ideas are quite general in terms of normal cell physiology: gamete formation and fertilization (King et al., 2005), development (de Moor and Richter, 2001), differentiation (Gao and Keene, 1996), and T cell activation (Atasoy et al., 1998), all involve active mRNA regulation. Regulation of ribonomic foci also occurs during intracellular stress responses in pathophysiological circumstances. We now return to a discussion of post-ischemic TA integrating ribonomic concepts.

4. Ribonomics and Post-Ischemic TA

Our recent work suggests that regulation of mRNA occurs in post-ischemic neurons and plays an important role in post-ischemic TA. In this section we discuss our work with SGs and ELAV/Hu granules, in which key themes have emerged. First, there appears to be a model dependence on how these structures act, which we tie back to the intensity of the ischemic insult. Second, a temporal sequence of events appears to relate changes in mRNA regulation to both post-ischemic TA and to the expression of post-ischemic stress responses.

A. Stress Granules

We initially investigated SGs as a possible mechanism of 40S sequestration in vulnerable reperfused neurons. This appeared to be the case when we observed a loss of cytoplasmic S6 from all but SGs in CA1 pyramidal neurons following cardiac arrest and resuscitation (CA/R)-induced brain I/R (Kayali et al., 2005). However, this study suffered the following limitations. (1) In Kayali et al. (2005), resistant brain regions, but not CA1, showed a rapid and transient increase in the number of SGs that paralleled eIF2α phosphorylation. If a significant fraction of 40S subunits were trapped in CA1 SGs, one would expect an increase in either the number or size of CA1 SGs, but neither of these occurred. This suggests the loss of S6 staining in CA1 was independent of SGs. (2) We could not recapitulate this result using bilateral carotid artery occlusion plus hypotension ischemia (2VO/HT) (DeGracia et al., 2007), a model which causes prolonged TA (Jamison et al., 2008) and DND in CA1 neurons (Smith et al., 1984). With 2VO/HT, a transient increase in the number of SGs occurred in all post-ischemic brain regions, including CA1, at 10 min reperfusion, as illustrated in Figure 1B. Further, in the 2VO/HT model, there was no loss of S6 either by immunostaining or Western blot (DeGracia et al., 2007). In fact, S6 staining does not substantially diminish in CA1 following 2VO/HT even at 24 h and 48 h reperfusion as can be seen in Figure 1A.

Thus CA/R and 2VO/HT show major differences with respect to S6 immunostaining. The differences between the two models may reflect ischemic intensity. The 2VO/HT and CA/R models showed peak hippocampal eIF2α(P) of 5-fold and 12-fold controls, respectively, at 10 min reperfusion after 10 min ischemia (Kumar et al., 2003; Roberts et al., 2007). As eIF2α(P) is a marker of cell stress (Clemens, 2001), its higher peak level after CA/R suggests that CA/R is a stronger insult than 2VO/HT. The increased insult intensity of CA/R may have induced S6 proteolysis, and/or some event that altered the antigenicity of S6. We note S6 showed a similar loss of staining in penumbral neurons following focal ischemia (Zhang et al., 2006). However, since 2VO/HT ischemia results in selective CA1 cell death, the loss of S6 signal from all but SGs in the CA/R model (Kayali et al., 2005) is clearly not required for cell death. Loss of S6 appears to be a phenomenon distinct from changes in SGs, and may represent an additional damage mechanism beyond that required for cell death. Zhang et al. (2006) suggested loss of S6 staining was due to sequestration in PAs. However, sequestration of 40S subunits in PAs accounts for only a fraction of total 40S subunits (Figure 1A and Zhang et al. (2006); DeGracia et al., 2007) so that there must also be an additional mechanism involved in altered S6 antigenicity.

We have now studied SGs out to 72 h reperfusion in the 2VO/HT model and documented changes in SG composition. SGs colocalized with PAs at 48 h reperfusion in vulnerable neurons (DeGracia et al., 2007). A transient colocalization of SGs with the mRNA destabilizing protein tristetraprolin (TTP) occurred at 16 h reperfusion in all reperfused neurons (Jamison et al., 2008).

Based on the above considerations, we feel we have falsified the hypothesis that SGs sequester a large percentage of 40S subunits in post-ischemic CA1 neurons. However, this does not rule out a role for SGs in other types of translation regulation after ischemia, as discussed below.

B. Redistribution of mRNA in Reperfused Neurons

We immunomapped eIF4G following CA/R and identified eIF4G aggregates that were more pronounced in CA1 compared to CA3 (DeGracia et al., 2006). We have detected similar eIF4G aggregates following 2VO/HT ischemia (Jamison et al., 2008). However, the main focus of Jamison et al. (2008) was to visualize polyadenylated [poly(A)] mRNAs in reperfused neurons using fluorescent in situ histochemistry (FISH). We observed a redistribution of cytoplasmic poly(A) mRNAs from a smooth homogeneous staining pattern seen in controls, to condensed, granular structures seen in all post-ischemic neurons (Figure 1C). We termed these structures “mRNA granules”, and these were present at 1 h reperfusion, the earliest time investigated. The mRNA granules were reversible in CA3, abating after 16 h reperfusion, when translation was recovering in CA3. In CA1 neurons, mRNA granules persisted to 48 h reperfusion, the latest time point studied, and CA1 continued to show TA to this time point. Thus, the presence of the mRNA granules correlated precisely with post-ischemic TA in both vulnerable and resistant neurons.

Colocalization via immunofluorescence histochemistry (IF) and FISH showed that the mRNA granules colocalized with identical granular structures of eIF4G and PABP, but did not colocalize with S6 (Figure 1C), TTP (a marker of P-bodies), or TIA-1 (a SG marker). The lack of colocalization of mRNA granules and S6 explained the correlation with TA; the mRNA granules appeared to sequester mRNA away from 40S subunits. That they did not colocalize with TTP or TIA-1 indicated that these structures were neither P-bodies nor SGs.

We also observed that HuR colocalized with mRNA granules in resistant CA3, but not with the mRNA granules in CA1 until 36 h reperfusion (Figure 1D). Cells that showed colocalization of HuR with the mRNA granules also showed translation of HSP70 protein. This correlation held for all but the 1h reperfusion time point, which is before significant accumulation of hsp70 mRNA occurs in reperfused neurons (Nowak, 1990). The colocalization of HuR with the mRNA granules led us to conclude that these structures were a form of ELAV/Hu granule.

These data suggest that the mRNA granules may not be homogeneous structures but may be playing at least a dual role. First, they may serve as sites that harbor the translationally silenced, constitutive mRNAs. This interpretation is consistent with the lack of colocalization with 40S subunits. Second, they may serve the function attributed to ELAV/Hu granules of partitioning stress-induced mRNAs into an RNA operon, functionally coordinating stress-induced mRNA translation. This would explain the correlation with HSP70 translation. Substantial further investigation will clearly be required to support these ideas.

One study, however, lends support to the idea of RNA operon-like functionality in post-ischemic brain. MacManus et al. (2004) performed translation-state analysis of polysomes at 20 h reperfusion after 1 h focal ischemia in mouse. Of the 1161 transcripts observed to increase in the stroked hemisphere, only 36% were polysome-associated. Using bioinformatics, polysome-associated transcripts clustered into the functional categories of heat shock, metallothioneins, other cell stress proteins, anti-inflammatory proteins, and cell survival proteins, suggesting coordinated transcript regulation (e.g. RNA operons). Although several TOP-containing mRNAs were polysome-associated, none contained IRES nor did they tend to have a 5′UTR longer than unbound transcripts (average ~200 nt). The latter point refutes our previous suggestion that degradation of eIF4G may enhance IRES initiation (DeGracia et al., 2002), and indicates that IRES initiation does not dominate post-ischemic translation. However, this study, in combination with our discovery of putative ELAV/Hu granules in post-ischemic neurons indicates that other modes of transcript regulation require further investigation.

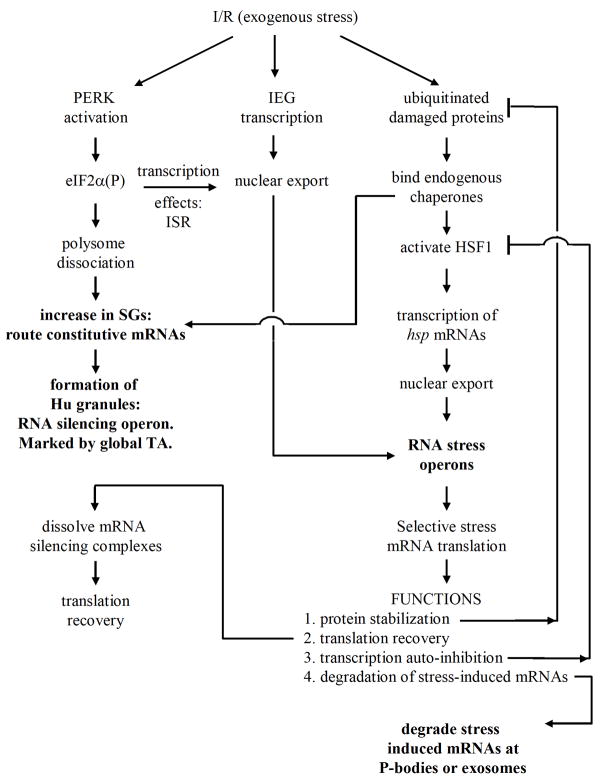

5. A Model of Post-Ischemic Translation Arrest

The colocalization of eIF4G, PABP and HuR with mRNA granules in post-ischemic neurons suggests the need to consider the role of ribonomic processes occurring after I/R. In this final section, we offer a model integrating ribonomic concepts with our current knowledge of post-ischemic TA. This model is intended as a hypothesis to guide further work. It is a hypothesis of what occurs in resistant neurons, where TA is reversible, and I/R-induced stress responses are completed effectively. Having a clear understanding of what occurs in resistant neurons provides a basis to investigate differences between vulnerable and resistant neurons. Further, resistant neurons survive the insult, so it is instructive to understand how they do so for the purpose of developing therapeutic interventions.

A. Stress Responses and Acute, Reversible Translation Arrest in Resistant Neurons

The starting point of the model (Figure 3) posits that some subset of I/R-induced cell damage mechanisms (such as ATP depletion during ischemia, reactive oxygen species, and Ca2+ overload during reperfusion, etc.), converge to a common end product: ubiquinated aggregates of damaged proteins (Bukau et al., 2006), which manifest as ubi-protein clusters in all reperfused neurons (Hu et al., 2000). Accumulation of damaged proteins is expected to directly activate the HSR transcription via HSF1 activation (Voellmy, 2004). IEG induction has been linked to ischemia-induced depolarization (Hossmann, 1993). IEG mRNAs contain ARE sequences (e.g. c-fos), implying that RNA operons regulating stress-induced mRNAs occur in post-ischemic neurons. Activation of PERK (Kumar et al., 2001) causes phosphorylation of eIF2α, which has transcriptional consequences known as the integrated stress response or IRS (Lu et al., 2004), which can account for ER stress-induced transcription in post-ischemic neurons (Roberts et al., 2007).

Figure 3.

A model of the role of translation regulation in stress responses induced in resistant post-ischemic neurons. Transcriptional reprogramming of post-ischemic neurons involves elements of endoplasmic reticulum stress (e.g. PERK activation and the integrated stress response, ISR), immediate early gene (IEG) induction and the heat shock response (rightmost column). Stress responses lead to silencing of constitutive mRNAs and selectively translation of stress-induced mRNAs via RNA operons. Stress proteins abate cell damage, inhibit stress-induced transcription and facilitate stress mRNA degradation and translational recovery. Abbreviations as used in the text. Steps in bold text are those involving cytoplasmic ribonomic foci hypothesized to be involved in post-ischemic translation arrest.

The immediate consequence of eIF2α phosphorylation will be to cause dissaggregation of polysomes. This in turn is expected to shift the polysome/SG equilibrium towards SG formation, increasing the number of SGs. Importantly, it has recently been proposed that constitutive chaperones modulate SG assembly (Anderson and Kedersha, 2008). Those SG components that self-assemble, such as TIA-1, may be prevented from self-aggregating by binding of constitutive chaperones (Gilks et al., 2004). Thus, accumulation of constitutive chaperones on damaged proteins may, in addition to activating HSF1, facilitate SG formation. This provides a mechanism whereby SG formation, and the downstream consequences, could occur in the absence of eIF2α phosphorylation, and may, in part, account for why translation inhibition was observed in the PERK conditional knockouts (Owen et al., 2005).

With SG formation, ribonomic considerations become central to the model. Polysomes dissaggregation not only produces free ribosomal subunits, but frees previously translated mRNAs. The question of the fate of previously translated mRNAs has not received adequate attention in the field. The transient increase in SGs seen at 10 min reperfusion (Figure 1B and Kayali et al., 2005) may reflect routing of constitutive mRNAs into ELAV/Hu granules marked by the mRNA granules we identified (Jamison et al., 2008). The increase in SG number precedes the formation of the mRNA granules (D.J.D, unpublished observation). The mRNA granules, as stated above, may serve in part to mediate mRNA silencing. This conclusion is consistent with one of the few studies of total mRNA in post-ischemic brain, that of Matsumoto et al. (1990). who showed altered mRNAs subcellular distribution in reperfused neurons. Additionally, in the first several hours of reperfusion, stress-induced transcription is transforming the ribonome. A second class of mRNA granules may serve as sites where stress-induced transcripts accumulate. The presence of HuR in such mRNA granules may not only be a marker of stress-RNA operons, but contribute functionally to the selective translation of the stress induced mRNAs (Antic and Keene, 1998).

Here lies the critical aspect that distinguishes the acute TA of resistant neurons from the persistent TA of vulnerable neurons (DeGracia, 2004). In acute TA, there is silencing of constitutive mRNAs for a period while stress-induced mRNAs are being transcribed. During this period, there should be almost no translation at all. As stress mRNAs accumulate in the cytoplasm, these should undergo selective translation, while constitutive mRNAs are still silenced. At this stage, there will be some recovery of translation as measured by amino acid incorporation, but the translation products will exclusively be stress proteins, and constitutive mRNAs will still be silenced. Indeed, this has been measured in post-ischemic brain (Dienel et al., 1986; Kiessling et al., 1986).

Successful translation of stress-induced mRNAs is the climax of genetic reprogramming and will have many consequences for cell function, but we depict only specific roles for HSP70 in Figure 3. Accumulation of HSP70 will contribute to the eventual clearance of the ubi-protein clusters (Figure 3, protein stabilization) (Bukau et al., 2006). This in turn will decrease the stimulus for HSF1 activation and lead to decreased transcription of HSP genes (Figure 3, transcription autoinhibition). HSP70 has been shown to contribute to the dissolution of SGs (Gilks et al., 2004), and thus may also participate in the dissolution of the mRNA granules, releasing constitutive mRNAs, allowing for a gradual recovery of general translation. Finally, some mechanism must exist to degrade stress-induced mRNAs. We observed a redistribution of TTP out of the nucleus and into TIA-1 containing SGs in both CA1 and CA3 neurons by 16 h reperfusion (Jamison et al., 2008). Redistribution of TTP, a known mRNA destabilizing protein (Blackshear, 2002), may mark processes involved in stress-induced mRNA degradation at P bodies and/or exosomes.

Thus, Figure 3 depicts a hypothesis of the net stress response occurring in resistant neurons. Stress-induced transcription and ribosome regulation co-occur with mRNA regulatory events, the latter of which simultaneously silence constitutive mRNAs, and contribute to selective translation of stress-induced mRNAs. The stress proteins function to abate cell damage, recover general translation, and terminate the stress response via transcription autoinhibitory mechanisms and degradation of stress-induced mRNAs. Although not depicted in Figure 3, clearance of damaged proteins, and the eventual degradation of the stress proteins must also occur.

B. Persistent Translation Arrest in Vulnerable Neurons

Nowak (1990) observed: “The lasting depression of protein synthesis and sustained expression of hsp70 mRNA in vulnerable hippocampal CA1 neurons appear to be mechanistically related and may constitute markers for cellular pathophysiology leading to neuronal cell loss.” We feel this was a prescient remark and an apropos introduction to a discussion of the relevance of ribonomics to irreversible TA in vulnerable reperfused neurons.

The model of resistant neurons described above provides a basis to ascertain steps or processes where regulatory dysfunction may occur in vulnerable neurons. The key to this exercise is the observation that hsp70 mRNA continues to accumulate in CA1 neurons, but there is no synthesis of HSP70 protein and TA persists (Nowak, 1990; Hossmann, 1993; Roberts et al., 2007). As can be seen in Figure 3, these events indeed are related by one common factor: HSP70. HSP70 inhibits its own transcription and contributes to translation recovery, focusing our attention on one key point: the selective translation of hsp mRNAs does not occur in CA1. While focus in the field has been almost exclusively on ribosome regulation, our model indicates that a defect occurs in the selective access of hsp70 mRNA to the ribosomes in vulnerable neurons, pointing instead to mRNA regulation. Therefore, we now discuss what is known about selective translation of hsp mRNAs.

C. Regulation of Translation During Heat Shock

Shortly after heat shock, TA occurs, followed by HSP gene transcription, robust translation of the HSPs while constitutive mRNAs are silenced, followed by a gradual recovery of constitutive translation (reviewed in Lindquist, 1986). Both translation recovery and termination of the HSR depend on HSP synthesis. Preventing synthesis of the HSPs also prevents translational recovery (Widelitz et al., 1987) and leads to super-induction of hsp70 mRNA (DiDomenico et al., 1982), a situation strikingly similar to that which occurs in vulnerable reperfused neurons.

However, the mechanisms of ribosome regulation following the HSR are not stereotyped (reviewed in Schneider, 2000). Phosphorylation of eIF2α may (Scorsone et al., 1987) or may not occur (Duncan and Hershey, 1984; Duncan et al., 1995), and levels of eIF2α(P) do not correlate with the degree of TA (Duncan et al., 1995). Changes in eIF4F better correlate with HSR-induced TA. These include dephosphorylation of eIF4E (Duncan and Hershey, 1984; Duncan et al., 1995), decreased eIF4F (Lamphear and Panniers, 1991), hypophosphorylation of 4E-BPs (Feigenblum and Schneider, 1996), and packaging of eIF4G in HSP27 granules (Cuesta et al., 2000).

In terms of mRNA regulation, sequences in the 5′UTR are important for selective hsp mRNA translation (Lindquist and Peterson, 1990), but the specific mechanisms vary. The grp78 mRNA contains a 5′UTR IRES (Macejak and Sarnow, 1991), but is not induced by heat shock (Munro and Pelham, 1986). Human and Drosophila inducible hsp70 mRNAs lack IRES and human hsp70 mRNA is translated via ribosome shunting (Schneider, 2000). The packaging of eIF4G in granules was suggested to enhance nonclassical initiation of hsp mRNAs, in part by preventing eIF4G-dependant scanning of constitutive mRNAs (Cuesta et al., 2000). Another aspect of the selective translation of hsp mRNAs is the silencing of constitutive mRNAs by packaging them into heat shock granules (Nover et al., 1983), now recognized to be plant analogs of SGs.

Thus, specific mechanisms of HSP selective translation are complex, vary from cell type to cell type, and involve multiple forms of regulation at both the ribosomes and mRNA. With respect to post-ischemic TA, our data support that selective HSP translation in post-ischemic brain has a reduced dependence on eIF4G since the mRNA granules sequestered a large proportion of eIF4G (Jamison et al., 2008). Additionally, Martin de la Vega et al. (2001) showed decreases in soluble eIF4G and eIF4F in both vulnerable and resistant areas prior to HSP translation in resistant areas. Our observations of mRNA granules that contain HuR suggest that both constitutive mRNA silencing and selective translation of stress-induced mRNAs via RNA operon mechanisms occurs in post-ischemic neurons.

D. Pinpointing the Defect That Prevents HSP Synthesis in Vulnerable Neurons

We suggest that the issues of both prolonged TA and delayed HSP translation shift to the ribonomic issue of possible roles of HuR and the mRNA granules in selective HSP translation.

The delay in HuR entering the mRNA granules of CA1 neurons (Jamison et al., 2008) is likely a marker of the defect that prevents selective translation of hsp mRNAs. HuR is known to export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm to effect formation of ELAV/Hu granules (Atasoy et al., 1998). Thus, CA1 neurons may have a defect in HuR nuclear export. Alternatively, there may be successful nuclear export, but a post-translational modification of HuR may occur in CA1 that precludes it entering mRNA granules. Furthermore, HuR has been shown to transport hsp70 mRNA from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Gallouzi et al., 2000) in complexes with the HuR ligands APRIL and pp32 (Gallouzi et al., 2001). This would suggest that hsp70 mRNA accumulates in the nuclei of CA1 neurons, which would also preclude its translation. All of these possibilities are experimentally testable hypotheses.

What is the consequence of lack of HuR in CA1 mRNA granules? One possibility is that, assuming they enter the cytoplasm, this may subject stress-induced mRNAs to the same fate as the constitutive mRNAs; which is to say, they are silenced. The mRNA stabilizing function of HuR suggests the logical possibility that lack of HuR in the mRNA granules causes a rapid turnover of stress-induced mRNAs. However the continued accumulation of hsp70 mRNA in post-ischemic CA1 (Nowak, 1990; Roberts et al., 2007) suggests rapid turnover does not occur. A direct avenue to investigate these various possibilities is to perform ribonomic analyses of stress-induced transcripts such as c-fos or hsp70 mRNA in both vulnerable and resistant regions. The prediction is that stress-induced mRNAs will have some combination of: (1) different subcellular localizations, (2) different protein binding partners and/or (3) different turnover rates, between vulnerable and resistant neuron populations.

6. Conclusions

While the ideas presented here derive from existent evidence, further investigations are clearly necessary. The model presented in Figure 3 serves three functions. First, it serves as a hypothesis to guide further work. Second, it deepens the relationship between post-ischemic TA and stress responses. Third, it introduces defects in mRNA regulation and ribonomic structures as candidate mechanisms underlying the defective stress response in vulnerable neurons. The defect in the stress response in vulnerable neurons is not TA per se, but impeded access of stress-induced mRNAs to the ribosomes, thereby shifting emphasis from ribosomes to mRNA.

Thus, regulation of transcription, ribosomes, and mRNA constitute the layers of players involved in post-ischemic TA, stress responses and cell fate. If the general framework presented here is on the right track, then the same mechanism(s) underlie both prolonged TA and defective expression of stress responses in vulnerable neurons. Identification of these mechanisms will open them to therapeutic intervention. Effective pharmacologic intervention would allow successful expression of stress responses in vulnerable neurons, from which translation recovery should mechanistically follow. While theoretical at the moment, such a therapy may prevent the demise of vulnerable neurons in the post-ischemic period.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the important work of many individuals and laboratories around the world who have contributed to the understanding of post-ischemic translation arrest. We would like to acknowledge the innovative insights of Paul Anderson, Nancy Kedersha and Jack Keene which formed core ideas in the present work. This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NS-057167, DJD).

Abbreviations

- 2VO/HT

bilateral carotid artery occlusion plus hypotension ischemia

- 40S

small ribosomal subunit

- 48S

preinitiation complex

- 4E-BP

eIF4E binding proteins

- 5′TOP

5′ terminal oligopyrimidine tract

- APRIL

acidic protein rich in lysine

- ARE

adenine and uridine rich element

- ATF

activating transcription factor

- CA/R

cardiac arrest and resuscitation

- CA

cornu ammonis

- CHOP

cyclic AMP response element binding protein homology protein

- DND

delayed neuronal death

- eEF2

eukaryotic elongation factor 2

- eIF

eukaryotic initiation factor

- ELAV

embryonic lethal abnormal vision

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- FISH

fluorescent in situ hybridization

- grp78

glucose regulated protein 78 kDa

- hnRNP

heavy nuclear ribonucleoprotein complex

- HDAC-6

histone deacetylase 6

- HSC70

constitutive 70 kDa heat shock protein

- HSF1

heat shock factor 1

- HSP

heath shock protein

- HSR

heat shock response

- HuR

mammalian homolog of ELAV

- I/R

ischemia and reperfusion

- IEG

immediate early gene

- IF

immunofluorescence histochemistry

- IRE1

inositol requiring

- IRES

internal ribosome entry site

- ISR

integrated stress response

- mRNP

messenger ribonucleoprotein particle

- PA

protein aggregate

- PABP

polyA binding protein

- P-body

processing body

- PERK

RNA-dependent protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum eIF2α kinase

- poly(A)

polyadenylated

- S6

small ribosomal subunit protein 6

- SG

stress granule

- TA

translation arrest

- TIA-1

T cell internal antigen 1

- TTP

tristetraprolin

- ubi-protein cluster

ubiquitin protein complex

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- UTR

untranslated region

- XBP-1

x-box binding protein 1

References

- Althausen S, Mengesdorf T, Mies G, Oláh L, Nairn AC, Proud CG, Paschen W. Changes in the phosphorylation of initiation factor eIF-2alpha, elongation factor eEF-2 and p70 S6 kinase after transient focal cerebral ischaemia in mice. J Neurochem. 2001;78:779–787. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00462.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. RNA granules. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:803–808. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P, Kedersha N. Stress granules: the Tao of RNA triage. Trends Biochem Sci. 2008;33:141–150. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2007.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antic D, Keene JD. Messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes containing human ELAV proteins: interactions with cytoskeleton and translational apparatus. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:183–197. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.2.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atasoy U, Watson J, Patel D, Keene JD. ELAV protein HuA (HuR) can redistribute between nucleus and cytoplasm and is upregulated during serum stimulation and T cell activation. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:3145–31456. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.21.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakheet T, Frevel M, Williams BR, Greer W, Khabar KS. ARED: human AU-rich element-containing mRNA database reveals an unexpectedly diverse functional repertoire of encoded proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:246–254. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreau C, Paillard L, Osborne HB. AU-rich elements and associated factors: are there unifying principles? Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;33:7138–71350. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackshear PJ. Tristetraprolin and other CCCH tandem zinc-finger proteins in the regulation of mRNA turnover. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30:945–952. doi: 10.1042/bst0300945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond U. Stressed out! Effects of environmental stress on mRNA metabolism. FEMS Yeast Res. 2006;6:160–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2006.00032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brengues M, Teixeira D, Parker R. Movement of eukaryotic mRNAs between polysomes and cytoplasmic processing bodies. Science. 2005;310:486–489. doi: 10.1126/science.1115791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:266–277. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brostrom CO, Brostrom MA. Regulation of translational initiation during cellular responses to stress. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol. 1998;58:79–125. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6603(08)60034-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukau B, Weissman J, Horwich A. Molecular chaperones and protein quality control. Cell. 2006;125:443–451. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burry RW, Smith CL. HuD distribution changes in response to heat shock but not neurotrophic stimulation. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1129–1138. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A6979.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter B, MacKay C, Alnabulsi A, MacKay M, Telfer C, Melvin WT, Murray GI. The roles of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins in tumour development and progression. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1765:85–100. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell SA, Dresios J, Edelman GM, Mauro VP. Ribosomal shunting mediated by a translational enhancer element that base pairs to 18S rRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:9488–9493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603597103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens MJ. Initiation factor eIF2 alpha phosphorylation in stress responses and apoptosis. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 2001;27:57–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-662-09889-9_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuesta R, Laroia G, Schneider RJ. Chaperone hsp27 inhibits translation during heat shock by binding eIF4G and facilitating dissociation of cap-initiation complexes. Genes Dev. 2000;14:1460–1470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dang Y, Kedersha N, Low WK, Romo D, Gorospe M, Kaufman R, Anderson P, Liu JO. Eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha-independent pathway of stress granule induction by the natural product pateamine A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:32870–32878. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Moor CH, Richter JD. Translational control in vertebrate development. Int Rev Cytol. 2001;203:567–608. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(01)03017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGracia DJ. Acute and persistent protein synthesis inhibition following cerebral reperfusion. J Neurosci Res. 2004;77:771–776. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGracia DJ, Hu BR. Irreversible translation arrest in the reperfused brain. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:875–893. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGracia DJ, Kumar R, Owen CR, Krause GS, White BC. Molecular pathways of protein synthesis inhibition during brain reperfusion: implications for neuronal survival or death. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2002;2:127–141. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200202000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGracia DJ, Rafols JA, Morley SJ, Kayali F. Immunohistochemical mapping of total and phosphorylated eukaryotic initiation factor 4G in rat hippocampus following global brain ischemia and reperfusion. Neuroscience. 2006;139:1235–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGracia DJ, Rudolph J, Roberts GG, Rafols JA, Wang J. Convergence of stress granules and protein aggregates in hippocampal cornu ammonis 1 at later reperfusion following global brain ischemia. Neuroscience. 2007;146:562–572. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande J, Bergstedt K, Lindén T, Kalimo H, Wieloch T. Ultrastructural changes in the hippocampal CA1 region following transient cerebral ischemia: evidence against programmed cell death. Exp Brain Res. 1992;88:91–105. doi: 10.1007/BF02259131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiDomenico BJ, Bugaisky GE, Lindquist S. The heat shock response is self-regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels. Cell. 1982;31:593–603. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90315-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dienel GA, Kiessling M, Jacewicz M, Pulsinelli WA. Synthesis of heat shock proteins in rat brain cortex after transient ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1986;6:505–510. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1986.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R, Hershey JW. Heat shock-induced translational alterations in HeLa cells. Initiation factor modifications and the inhibition of translation. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:11882–11889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RF, Cavener DR, Qu S. Heat shock effects on phosphorylation of protein synthesis initiation factor proteins eIF-4E and eIF-2 alpha in Drosophila. Biochemistry. 1995;34:2985–2997. doi: 10.1021/bi00009a030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feigenblum D, Schneider RJ. Cap-binding protein (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E) and 4E-inactivating protein BP-1 independently regulate cap-dependent translation. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5450–5457. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.10.5450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari F, Mercaldo V, Piccoli G, Sala C, Cannata S, Achsel T, Bagni C. The fragile X mental retardation protein-RNP granules show an mGluR-dependent localization in the post-synaptic spines. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2007;34:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2006.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallouzi IE, Brennan CM, Steitz JA. Protein ligands mediate the CRM1-dependent export of HuR in response to heat shock. RNA. 2001;7:1348–1361. doi: 10.1017/s1355838201016089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallouzi IE, Brennan CM, Stenberg MG, Swanson MS, Eversole A, Maizels N, Steitz JA. HuR binding to cytoplasmic mRNA is perturbed by heat shock. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3073–3078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.7.3073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- García-Bonilla L, Cid C, Alcázar A, Burda J, Ayuso I, Salinas M. Regulatory proteins of eukaryotic initiation factor 2-alpha subunit (eIF2 alpha) phosphatase, under ischemic reperfusion and tolerance. J Neurochem. 2007;103:1368–1380. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04844.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao FB, Keene JD. Hel-N1/Hel-N2 proteins are bound to poly(A)+ mRNA in granular RNP structures and are implicated in neuronal differentiation. J Cell Sci. 1996;109:579–589. doi: 10.1242/jcs.109.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilks N, Kedersha N, Ayodele M, Shen L, Stoecklin G, Dember LM, Anderson P. Stress granule assembly is mediated by prion-like aggregation of TIA-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:5383–5398. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-08-0715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosset C, Chen CY, Xu N, Sonenberg N, Jacquemin-Sablon H, Shyu AB. A mechanism for translationally coupled mRNA turnover: interaction between the poly(A) tail and a c-fos RNA coding determinant via a protein complex. Cell. 2000;103:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton TL, Stoneley M, Spriggs KA, Bushell M. TOPs and their regulation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:12–16. doi: 10.1042/BST20060012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesketh J. 3′-Untranslated regions are important in mRNA localization and translation: lessons from selenium and metallothionein. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:990–993. doi: 10.1042/BST0320990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinnebusch AG. Gene-specific translational control of the yeast GCN4 gene by phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2. Mol Microbiol. 1993;10:215–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01947.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossmann KA. Disturbances of cerebral protein synthesis and ischemic cell death. Prog Brain Res. 1993;96:161–177. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6123(08)63265-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu BR, Martone ME, Jones YZ, Liu CL. Protein aggregation after transient cerebral ischemia. J Neurosci. 2000;20:3191–3199. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-09-03191.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamison JT, Kayali F, Rudolph J, Marshall MK, Kimball SR, DeGracia DJ. Persistent Redistribution of Poly-Adenylated mRNAs Correlates with Translation Arrest and Cell Death Following Global Brain Ischemia and Reperfusion. Neuroscience. 2008;154:504–520. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1211–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayali F, Montie HL, Rafols JA, DeGracia DJ. Prolonged translation arrest in reperfused hippocampal cornu Ammonis 1 is mediated by stress granules. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1223–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Cho MR, Li W, Yacono PW, Chen S, Gilks N, Golan DE, Anderson P. Dynamic shuttling of TIA-1 accompanies the recruitment of mRNA to mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 2000;151:1257–1268. doi: 10.1083/jcb.151.6.1257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha N, Stoecklin G, Ayodele M, Yacono P, Lykke-Andersen J, Fritzler MJ, Scheuner D, Kaufman RJ, Golan DE, Anderson P. Stress granules and processing bodies are dynamically linked sites of mRNP remodeling. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:871–884. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200502088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedersha NL, Gupta M, Li W, Miller I, Anderson P. RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and TIAR link the phosphorylation of eIF-2 alpha to the assembly of mammalian stress granules. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1431–1442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.7.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD, Lager PJ. Post-transcriptional operons and regulons co-ordinating gene expression. Chromosome Res. 2005;13:327–337. doi: 10.1007/s10577-005-0848-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD. Ribonucleoprotein infrastructure regulating the flow of genetic information between the genome and the proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7018–7024. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111145598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keene JD. RNA regulons: coordination of post-transcriptional events. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:533–543. doi: 10.1038/nrg2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khabar KA. The AU-Rich Transcriptome: More Than Interferons and Cytokines, and Its Role in Disease. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 2005;25:1–10. doi: 10.1089/jir.2005.25.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiessling M, Dienel GA, Jacewicz M, Pulsinelli WA. Protein synthesis in postischemic rat brain: a two-dimensional electrophoretic analysis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1986;6 :642–649. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1986.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King ML, Messitt TJ, Mowry KL. Putting RNAs in the right place at the right time: RNA localization in the frog oocyte. Biol Cell. 2005;97:19–33. doi: 10.1042/BC20040067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirino T, Sano K. Fine structural nature of delayed neuronal death following ischemia in the gerbil hippocampus. Acta Neuropathol. 1984;62:209–218. doi: 10.1007/BF00691854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krichevsky AM, Kosik KS. Neuronal RNA granules: a link between RNA localization and stimulation-dependent translation. Neuron. 2001;32:683–696. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00508-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Azam S, Sullivan JM, et al. Brain ischemia and reperfusion activates the eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha kinase, PERK. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1418–1421. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Krause GS, Yoshida H, Mori K, DeGracia DJ. Dysfunction of the unfolded protein response during global brain ischemia and reperfusion. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:462–471. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000056064.25434.CA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon S, Zhang Y, Matthias P. The deacetylase HDAC6 is a novel critical component of stress granules involved in the stress response. Genes Dev. 2007;21:3381–3394. doi: 10.1101/gad.461107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamphear BJ, Panniers R. Heat shock impairs the interaction of cap-binding protein complex with 5′ mRNA cap. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2789–2794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laroia G, Cuesta R, Brewer G, Schneider RJ. Control of mRNA decay by heat shock-ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. Science. 1999;284:499–502. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5413.499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S, Petersen R. Selective translation and degradation of heat-shock messenger RNAs in Drosophila. Enzyme. 1990;44:147–166. doi: 10.1159/000468754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist S. The heat-shock response. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1151–1191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CL, Ge P, Zhang F, Hu BR. Co-translational protein aggregation after transient cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2005;134:1273–1284. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu PD, Harding HP, Ron D. Translation reinitiation at alternative open reading frames regulates gene expression in an integrated stress response. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:27–33. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macejak DG, Sarnow P. Internal initiation of translation mediated by the 5′ leader of a cellular mRNA. Nature. 1991;353:90–94. doi: 10.1038/353090a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacManus JP, Graber T, Luebbert C, Preston E, Rasquinha I, Smith B, Webster J. Translation-state analysis of gene expression in mouse brain after focal ischemia. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2004;24:657–667. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000123141.67811.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangus DA, Evans MC, Jacobson A. Poly(A)-binding proteins: multifunctional scaffolds for the post-transcriptional control of gene expression. Genome Biol. 2003;4:223–237. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-7-223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín de la Vega C, Burda J, Nemethova M, Quevedo C, Alcázar A, Martín ME, Danielisova V, Fando JL, Salinas M. Possible mechanisms involved in the down-regulation of translation during transient global ischaemia in the rat brain. Biochem J. 2001;357:819–826. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews MB, Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB. Origins and principles of translational control. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB, editors. Translational Control of Gene Expresion. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2000. pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto K, Yamada K, Hayakawa T, Sakaguchi T, Mogami H. RNA synthesis and processing in the gerbil brain after transient hindbrain ischaemia. Neurol Res. 1990;12:45–48. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1990.11739912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro S, Pelham HR. An Hsp70-like protein in the ER: identity with the 78 kd glucose-regulated protein and immunoglobulin heavy chain binding protein. Cell. 1986;46:291–300. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Sato K, Hanyu-Nakamura K. Drosophila cup is an eIF4E binding protein that associates with Bruno and regulates oskar mRNA translation in oogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;6:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie L, Wu G, Culley DE, Scholten JC, Zhang W. Integrative analysis of transcriptomic and proteomic data: challenges, solutions and applications. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2007;27:63–75. doi: 10.1080/07388550701334212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nover L, Scharf KD, Neumann D. Formation of cytoplasmic heat shock granules in tomato cell cultures and leaves. Mol Cell Biol. 1983;3:1648–1655. doi: 10.1128/mcb.3.9.1648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowak TS., Jr Protein synthesis and the heart shock/stress response after ischemia. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev. 1990;2:345–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen CR, Kumar R, Zhang P, McGrath BC, Cavener DR, Krause GS. PERK is responsible for the increased phosphorylation of eIF2alpha and the severe inhibition of protein synthesis after transient global brain ischemia. J Neurochem. 2005;94:1235–1242. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W. Disturbances of calcium homeostasis within the endoplasmic reticulum may contribute to the development of ischemic-cell damage. Med Hypotheses. 1996;47:283–288. doi: 10.1016/s0306-9877(96)90068-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W. Shutdown of translation: lethal or protective? Unfolded protein response versus apoptosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2003;23:773–779. doi: 10.1097/01.WCB.0000075009.47474.F9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering BM, Willis AE. The implications of structured 5′ untranslated regions on translation and disease. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2005;16:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2004.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pisarev AV, Shirokikh NE, Hellen CU. Translation initiation by factor-independent binding of eukaryotic ribosomes to internal ribosomal entry sites. C R Biol. 2005;328:589–605. doi: 10.1016/j.crvi.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter JD, Sonenberg N. Regulation of cap-dependent translation by eIF4E inhibitory proteins. Nature. 2005;433:477–480. doi: 10.1038/nature03205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts GG, Di Loreto MJ, Marshall M, Wang J, DeGracia DJ. Hippocampal cellular stress responses after global brain ischemia and reperfusion. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9:2265–2275. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider RJ. Translational control during heat shock. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB, editors. Translational Control of Gene Expresion. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2000. pp. 581–593. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz DC, Parker R. Interaction of mRNA translation and mRNA degradation in saccharomyces cerevisiae. In: Sonenberg N, Hershey JWB, Mathews MB, editors. Translational Control of Gene Expresion. Cold Spring Harbor Press; Cold Spring Harbor, New York: 2000. pp. 807–826. [Google Scholar]

- Scorsone KA, Panniers R, Rowlands AG, Henshaw EC. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 during physiological stresses which affect protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:14538–14543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ML, Bendek G, Dahlgren N, Rosén I, Wieloch T, Siesjö BK. Models for studying long-term recovery following forebrain ischemia in the rat. 2. A 2-vessel occlusion model. Acta Neurol Scand. 1984;69:385–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.1984.tb07822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart M. Ratcheting mRNA out of the nucleus. Mol Cell. 2007 Feb 9;25(3):327–30. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoecklin G, Anderson P. In a tight spot: ARE-mRNAs at processing bodies. Genes Dev. 2007;21:627–631. doi: 10.1101/gad.1538807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira D, Parker R. Analysis of P-body assembly in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2274–2287. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tenenbaum SA, Lager PJ, Carson CC, Keene JD. Ribonomics: identifying mRNA subsets in mRNP complexes using antibodies to RNA-binding proteins and genomic arrays. Methods. 2002;26:191–198. doi: 10.1016/S1046-2023(02)00022-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadkhan S. The spliceosome: caught in a web of shifting interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2007;17:310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villacé P, Marión RM, Ortín J. The composition of Staufen-containing RNA granules from human cells indicates their role in the regulated transport and translation of messenger RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:2411–2420. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voellmy R. On mechanisms that control heat shock transcription factor activity in metazoan cells. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2004;9:122–133. doi: 10.1379/CSC-14R.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells SE, Hillner PE, Vale RD, Sachs AB. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widelitz RB, Duffy JJ, Gerner EW. Accumulation of heat shock protein 70 RNA and its relationship to protein synthesis after heat shock in mammalian cells. Exp Cell Res. 1987;168:539–545. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(87)90026-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Liu CL, Hu BR. Irreversible aggregation of protein synthesis machinery after focal brain ischemia. J Neurochem. 2006;98:102–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03838.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]