Abstract

Most studies that examine the ontogeny of lymphoid organ development in teleostean fishes use species of interest to aquaculture or genetic research, and to date have focused on strictly marine or strictly freshwater species. The mummichog, Fundulus heteroclitus, also known as the estuarine killifish, is a unique model for studies on developmental immunobiology because it is euryhaline, has a high degree of thermal tolerance, and has a unique reproductive strategy. Embryonic and larval mummichogs were examined for the ontogeny of lymphoid tissue development. The first lymphoid organ to appear was the head kidney at 1 dph, followed by the spleen at 1 wph, and then the thymus at 3 wph. Rag-1 was partially cloned and sequenced and shown to be highly conserved among other vertebrate Rag-1 genes. Using QT-PCR to monitor the temporal expression of Rag-1 it was shown to reach a maximum intensity at 3- and 4-wph, and to then drop to pre-2 wph levels. Overall, this study suggests that juvenile mummichogs do not possess the ability to mount T- or B-cell responses until some time after 5-wph. Even though the estuarine killifish tolerates a wide range of salinities, the developmental patterns of lymphoid tissues are similar to what has been reported for strictly marine (stenohaline) teleosts. Thus, the mummichog should be a convenient model for understanding the developmental immunobiology of most marine teleosts.

Keywords: estuarine killifish, mummichog, Fundulus heteroclitus, Rag-1, lymphoid ontogeny, eco-immunity

Most studies that examine the ontogeny of lymphoid organ development in teleostean fishes use species of interest to aquaculture or genetic research, and to date have focused on strictly marine or strictly freshwater species (Willett et al., 1997; Chantanachookhin et al., 1991; Petrie-Hanson and Ainsworth, 2001; Falk-Petersen, 2005). The mummichog, Fundulus heteroclitus, also known as the estuarine killifish, is a unique model for studies on developmental immunobiology because it is euryhaline, has a high degree of thermal tolerance, and has a unique reproductive strategy (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1953; Burnett et al., 2007). Mummichogs inhabit the high-marshes of east coast North American estuaries, which are subjected to rapid changes in daily, lunar, and seasonal salinity and temperature.

Because the mumichog prefers high marsh habitats, it has a small home-range throughout it's life cycle (Kneib, 1986). Moreover, the mummichog is the most abundant species of fish in high marsh habitats and comprises a large percentage of the total secondary production of salt marshes (Meredith and Lotrich, 1979; Kneib, 1986). As an adaptation to their environment, mummichogs reproduce on the lunar cycle throughout the warmer months of the year (Hsiao et al., 1994). Adult mummichogs deposit fertilized eggs in the high marsh at each spring high tide, which then desiccate until the subsequent spring high tide on the next lunar cycle. Re-hydration upon the next high tide initiates development of the embryos that then wash out to the marsh on the outgoing tide. Rapid changes in environmental conditions are known to negatively impact immunity in many teleostean fishes (Rice and Arkoosh, 2002), but most of the species examined to date live in fairly stable environments in terms of temperature and salinity. Whether or not the unique life strategy of mummichogs, and if living in such a dynamic environment affects the developmental sequence of lymphoid organs differently than what is seen in freshwater or stenohaline species has not been examined until this study.

While several components of innate immunity of fishes are present at hatching, the ability to mount antigen-specific responses develops after hatching, and at different rates in different species of fish (Zapata et al., 2006). Antigen specific immune responses in vertebrates are mediated through lymphocytes bearing either T-cell receptor (TCR) or the B-cell receptor (BCR), and these responses to can be generated against a wide variety of antigens through the generation of diversity in antigen receptors. The generation of diversity in TCRs and BCRs of vertebrate lymphocytes is the result of coordinated events in the maturation of lymphoid precursors, the most important of which is rearrangement of immunoglobulin (Ig) genes in B-cells, and TCR genes of T-cells. Successful rearrangement of Ig and TCR genes then serves as control steps for further maturation steps (Reichman-Fried et al., 1990; Spanopoulou et al., 1994; Young et al., 1994; Huang and Kanagawa, 2004).

Recombination of TCRs and BCRs is dependent on recombinases and DNA-repair enzymes, but two recombinase genes are absolute requirements; recombination activation gene-1 (Rag-1) and recombination activation gene-2 (Rag-2). The amino acid sequence of Rag-1 and -2, and especially of Rag-1, are highly conserved among vertebrates (Oettinger et al., 1990; Greenhalgh et al., 1993; Hansen and Kaattari, 1995, 1996; Willett et al., 1997a), with the highest degree of homology in the core region (Sadofsky et al., 1993; Willett et al., 1997a). An absence of either Rag gene results in a lack of mature B and T cells, which subsequently causes severe immune disorders such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) (Mombaerts et al., 1992; Sobacchi et al., 2006). Thus, Rag genes are essential for proper development of lymphoid organs, and the expression of Rag-1 and -2 can be used to identify the time of appearance of lymphoid cells and organs during development of the immune system.

The study described herein demonstrates that during development the head kidney of mumichogs is the first organ to become lymphoid, followed by the spleen, and then the thymus. The thymus was not fully lymphoid until 3-wph. The expression of whole-body Rag-1 in developing fish was low until rapidly reaching peak levels at 3-wph, but soon thereafter fell to pre-hatching levels. Overall, the developmental patterns of lymphoid tissues in the mummichog mirrored those previously described in strictly marine (stenohaline) fish. This study supports the continued use of mummichogs as a model for testing the effects of various environmental stressors; such as salinity, temperature, and pollutants on the developing immune system of marine fish as sentinels for environmental health assessment and to understand the basic biology of developmental immunology in marine fish.

Materials And Methods

Animals

Adult mummichogs, Fundulus heteroclitus, were collected with baited minnow traps from North Inlet-Winyah Bay at Belle W. Baruch, Georgetown, SC USA. Eggs and milt were collected manually according to previously published methods (Armstrong and Child, 1965) and fertilized eggs were transported to laboratories at Clemson University. After fertilization, developing mummichog embryos were maintained in Petri dishes with enough artificial seawater (Instant Ocean) at 18 g/L to cover the eggs. Each day the embryos were observed and moribund animals were removed and water was exchanged. Upon hatching, larvae mummichogs were transferred to 1L aquaria in an aerated recirculating flow through system (Aquaneering Zebra fish System, San Diego, CA USA) that held mulitple1L tanks. Water flowed out of the tanks into a biological filter bed, pumped thru a UV light source, and returned to the tanks. Newly hatched fry were maintained in well-aerated re-circulating aquaria for the duration of their development. In our hands, mummichog embryos typically hatch 12-14 days post-fertilization under a 12:14 light:dark photoperiod at 22°C. Fish were fed Artemia salina nauplii (Brine Shrimp Direct) until 4 weeks post-hatch (wph) and thereafter with commercial feed (Tetra).

Embryonic and larval mummichogs were sampled at the following stages of development: 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 7-days post-fertilization (dpf), 1 day post-hatch (dph), 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5- weeks post-hatch (wph). For RNA and protein analysis, 3 replicates of pooled individuals of each age group were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. For histological analysis, 3 individuals from 4- and 7-dpf, 1-dph, and 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-wph were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde in Hanks balanced salt solution (166 mM NaCl, 6.5 mM KCL, 6.8 mM glucose, 0.05 mM KH2HPO4, 0.07 mM Na2HPO4H2O in 1L Di H2O), hereafter referred to as HBSS. Samples for histology and protein/RNA were maintained at 4°C and -80°C, respectively, until further analysis.

Preparation of tissues for immunohistochemistry and light microscopy

Larvae and embryos were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in HBSS and maintained at 4°C until further processing. After fixation, the tissues were dehydrated through graded solutions of ethanol (25, 50, 75, 100, 100 %) for 30 min each at room temperature, cleared in xylene for 30 min at room temperature, and returned to 100% ETOH for 30 min at room temperature. The samples were then infiltrated with Immunobed (Polysciences, Inc.) embedding media with graded solutions of ethanol and catalyzed resin (50 ETOH: 50 resin at 4°C overnight, 100% resin 6 hr at 4°C, and 100% resin overnight at 4°C) per manufacturer's protocol. After overnight incubation in 100% catalyzed resin, the samples were embedded according to manufacturer's specifications (0.4 ml of accelerator B/10 ml catalyzed resin). Sagital and oblique sections (1.5 μM) were cut on a microtome (Leica RM 2165), floated in a water bath, placed on colorfrost® slides (Fisher Scientific), and fixed to the slide on a hot plate.

All tissue sections were imaged on a Nikon E-600 light microscope with either a 4X, 10X, 20X, 40X, or 60X objective. Photomicrographs were taken using a Qimaging Micropublishing digital camera. The criteria for describing lymphoid organs and relative degree of lymphoid cell populations was as previously described (Chantanachookhin et al., 1991; Petrie-Hanson and Ainsworth, 2001, Liu et al., 2004)

Cloning mummichog Rag-1 for monitoring whole-body expression

A portion of mummichog Rag-1 was obtained from polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification of mummichog genomic DNA using degenerate primers (Table 1) according to previously published methods (Greenhalgh et al., 1993). For genomic DNA extraction, the liver was removed from one euthanized (MS-222, 1 g/L) adult animal and the DNA isolated using the Wizard® genomic DNA purification kit according to manufacturer's protocol (Promega). A 50 μl PCR reaction was performed with the Accuprime Taq polymerase system (Invitrogen) under conditions outlined in Table 1. The expected fragment size of ∼600 bp was visualized on a 1% agarose gel and the product cloned into the pCR®2.1 vector using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen). Positive clones were selected through PCR screening and the plasmid DNA digested with EcoRI (Promega) for further validation and then sequenced at the University of Maine Sequencing Facility (Orono, ME USA).

Table 1.

Summary of lymphoid organ histogenesis during mummichog development

| Age | Kidney | Spleen | Thymus |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 dpf | --- | --- | --- |

| 7 dpf | --- | --- | --- |

| 1 dph | + | --- | --- |

| 1 wph | + | + | --- |

| 2 wph | + | + | --- |

| 3 wph | + | + | + |

| 4 wph | + | + | + |

| 5 wph | + | + | + |

Three individuals were examined per age group, dpf =days post-fertilization, dph=days post-hatch, wph=weeks post-hatch. +/- indicates presence or absence of organ in individuals.

After sequencing to confirm identity, new Rag-1 specific gene primers (GSP) with Sac I and Hind III restriction sites were designed and synthesized by Sigma-Genosys (Sigma) (Table 2). The Rag-1 forward primer contained the Sac I restriction site while the reverse primer contained the Hind III restriction site. To aid restriction enzyme binding to the restriction site sequence, four extra nucleotides were included at the end of each restriction site sequence.

Table 2.

Oligonucletide primer sequences for cloning mummichog Rag-1

| Primer name | Sequences (5′-3′) | Tm C° | Product size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Degenerate Rag-1 Forwarda | CAYTGYGAYATHGGIAAYGC | 55.3 | 638bp |

| Degenerate Rag-1 Reversea | TTRTGIGCRTTCATRAAYTTYTG | 59.6 | 638bp |

| GSP Rag-1 Forwardb | AACCAGTGATGAGGATG | 53.5 | 379bp |

| GSP Rag-1 Reverseb | ACTGTTCAGGCGGTTCAG | 61.5 | 379bp |

| Rag-1 Forwardc | GTACGAGCTCAACCAGTGATGAGGATG | 71.3 | 385bp |

| Rag-1 Reversec | ATCGAAGCTTCTGAACCGCCTGAACAGT | 75.0 | 385bp |

Degenerate sequence obtained from Greenhalgh et al. (Greenhalgh et al., 1993). (Y is C or T, R is A or G, H is A, C, or T)

Gene specific primers (GSP) for cDNA construct.

Primers for expression construct. Restriction site portion of primer sequences are underlined

cDNA construct

Total RNA was isolated from developing mummichogs for production of cDNA. In early development it is not possible to isolate specific organs, therefore whole animals were homogenized. Total RNA was isolated from developing mummichog embryos at 1 week post-fertilization using a micro-bead homogenizer (Biospec Products, Inc.) with 2 mm zirconia beads and TriReagent® (100 μl per mg tissue) as suggested by the manufacturers. Total RNA was primed and reverse-transcribed with SuperScript™ (Invitrogen), as prescribed by the manufacturer. All cDNA samples were stored at -20°C until further analysis.

Rag-1 was amplified from cDNA with 5 μM of each GSP (Table 2) using Accuprime system (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's protocol. The PCR product was cloned into the pCR®2.1 vector using the TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) and positive clones were selected through PCR screening. Positive clones were digested with EcoRI (Promega) for further validation and then sequenced at the University of Maine Sequencing Facility (Orono, ME USA). The deduced amino acid sequence from cDNA was then compared to zebrafish, mouse, human, rainbow trout, and Xenopus Rag-1 sequences using the alignment software ClustalW (Chenna et al., 2003).

Isolation of total RNA and first strand synthesis from embryos and whole fish

For each age group, three groups of 12-15 individuals were pooled for RNA analysis. Total RNA from embryos and whole fish was isolated in TriReagent® at a concentration of 100 mg tissue/ml of TriReagent® per manufacturer's protocol (Molecular Research Center, Inc.). Embryos were homogenized in a micro-bead homogenizer (Biospec Products, Inc.) with 2 mm zirconia beads while hatched fry were homogenized with a liquid nitrogen-cooled mortar and pestle. Tissues were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and then added to TriReagent®. Total RNA (1μg) was primed and reverse-transcribed with SuperScript™ (Invitrogen), as described by the manufacturer. cDNA samples were stored at -20°C until real time quantitative PCR analysis.

Real-time quantitative-PCR of Rag-1 expression during development

For real time quantitative-polymerase chain reaction of Rag-1, 100 ng of cDNA was added to 2× iQ SYBR Green supermix (BioRad) with 0.2 μM of forward and reverse primers, and water for a total volume of 15 μl. Quantitative PCR was run on a iCycler thermocycler (BioRad) with the following reaction conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C, 40 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s and annealing at 65°C for 30 s, followed by a final extension at 55°C for 1 min. Melt curve analysis was performed with continuous fluorescence from 65 to 95°C at a temperature transition rate of 0.01°C/s to determine amplification specificity. β-actin was used as the housekeeping gene and Rag-1 as the gene of interest.

The olignonucleotide primer sequence for each gene are listed in Table 2, along with their respective annealing temperature. To minimize variability due to reverse transcription efficiency and quality between samples, the data were normalized by dividing ng of Rag-1 by ng of β-actin. Quantitative results are reported as relative levels of Rag-1 normalized to β-actin. Each sample was run in quadruplicate together with the appropriate non-template controls and known dilutions of plasmid cDNA, carrying a fragment of the respective target gene, ranging from 0.001 to 0.0000001ng. For each run, a standard curve was generated for β-actin and Rag-1 using known concentrations of respective plasmid cDNA carrying a fragment of the respective target gene. The concentration of β-actin and Rag-1 in unknown samples was determined from the β-actin and Rag-1 standard curve, respectively. Rag-1 was normalized to β-actin by dividing ng of Rag-1 by ng of β-actin, previously generated from the standard curves. Quantitative results are represented as relative levels of Rag-1 normalized to β-actin. In all quantitative real-time PCR runs, melt curve analyses were performed and single peaks were observed indicating amplification specificity, and that non-template controls were negative (data not shown).

Statistical analysis

Statistical differences in RAG-1 expression among the age groups were tested with Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) followed by Neman Keul post hoc test. An α value of p ≤ 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

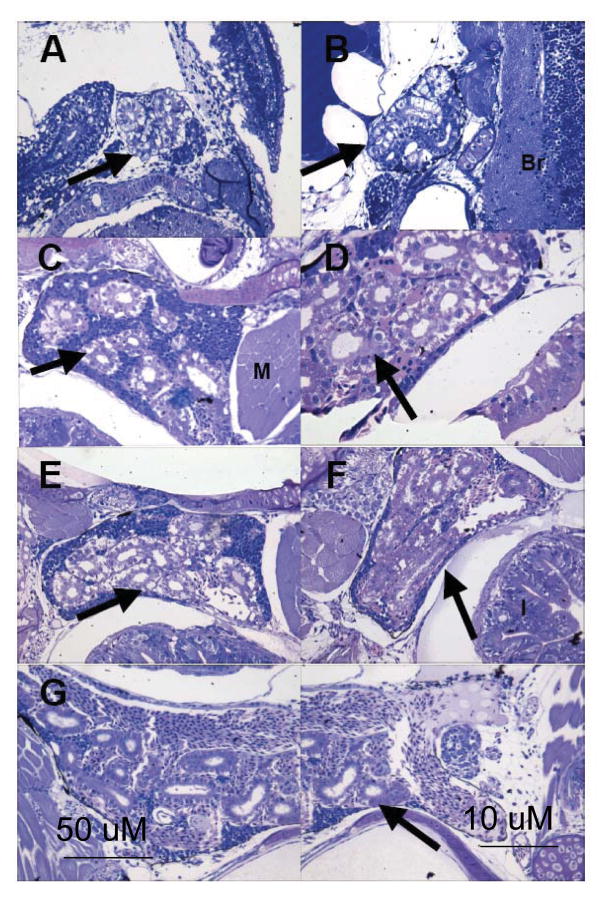

Clusters of renal tubules were first observed in the head kidney of developing mummichogs at 7-dpf prior to the appearance of hematopoietic tissues (Fig. 1 (a)). The head kidney was always found as a paired organ on either side of the head, anterior to the intestines, and dorsal to the yolk sac. At hatching (1-dph), there was a slight increase in renal tubules, and the first few hematopoietic cells appeared as scattered cells next to the renal tubules (Fig. 1 (b)). Morphologically, the hematopoietic cells appeared round, had dark basophilic staining, and some had a large nucleus to cytoplasm ratio. As fish aged, there was an increase in both the number of renal tubules and hematopoietic cells in the head kidney. From 2- to 4-wph, there was a transition in cell types of the head kidney from predominantly basophilic staining to acidophilic staining (Fig. 1 (d-f)). This shift in cell types occurred predominantly in cells that directly surrounded the renal tubules. However, by 5-wph acidophilic staining cells were found homogenously scattered throughout the head kidney parenchyma (Fig. 1 (g)).

Fig. 1.

Appearance of lymphoid tissues in head kidney of the mummichog. Sagital and oblique sections of 7 dpf (a), 1 dph (b), 1-, 2-, 3-, 4-wph (c-f, respectively), and 5- wph (g) were stained with azure II and basic fuchsin. Note, photomicrograph (g) includes two micrographs of the same 5-wph head kidney. Br: brain, I: intestine, and M: muscle. Black arrows indicate renal tubules. Size bars are the same (50 μM) for all three sections on the left, and the same (10 μM) for all three sections on the right.

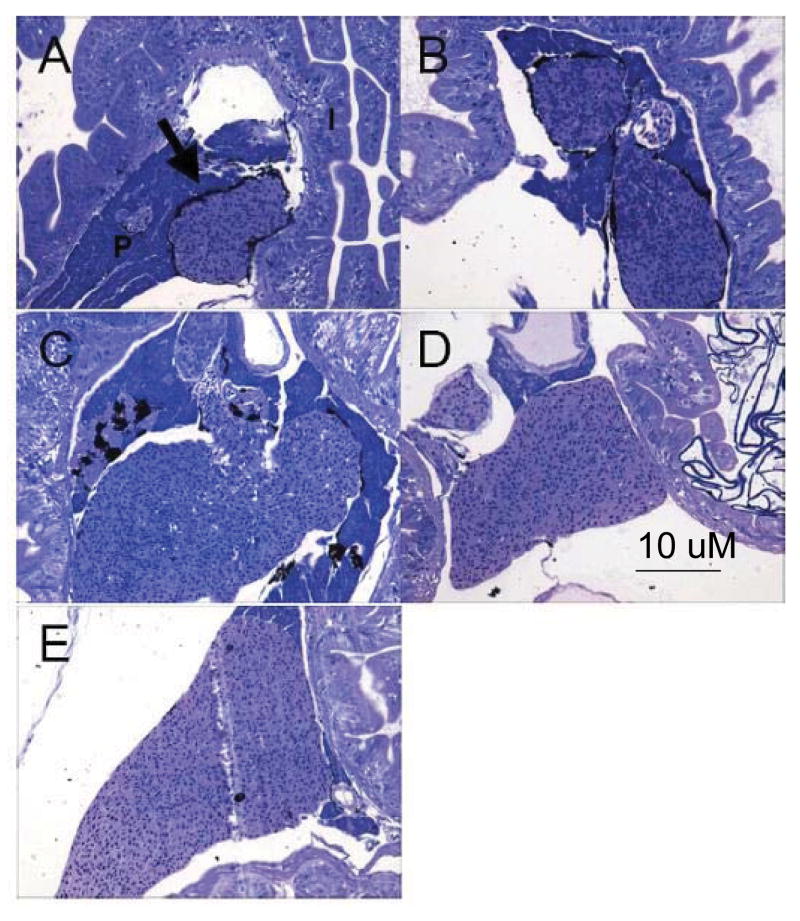

The spleen of developing mummichogs was first observed at 1-wph located between the intestine and liver, closely associated with pancreatic tissue. As fish aged, the spleen became elongated, became less associated with pancreatic tissue, and increased in cellularity (Fig. 2 (a-e)). At 2- and 3- wph, a thin layer of pigmented mesentery surrounded a portion of the spleen (Fig. 2 (b-c)). Pigmented mesentery was not observed at 4- or 5-wph (Fig. 2 (d-e)). In all stages studied, the parenchyma appeared homogenous and was comprised of mostly erythrocytes, which appeared pink when stained, indicating a high amount of acidophilic residues. There were no definite divisions of white and red pulp, nor were melanomacrophage centers (MMCs) observed.

Fig. 2.

Appearance of lymphoid tissues in the spleen of the mummichog. Sagital and oblique sections of 1-, 2-, 3-, 4, and 5- wph (a-e, respectively) juvenile mummichog were stained with azure II and basic fuchshin. The spleen is adjacent to the liver and intestinal epithelium, closely associated with pancreatic tissue. I: intestine, P: pancreatic tissue. Black arrows indicate the spleen. The size bar is the same for all 5 sections.

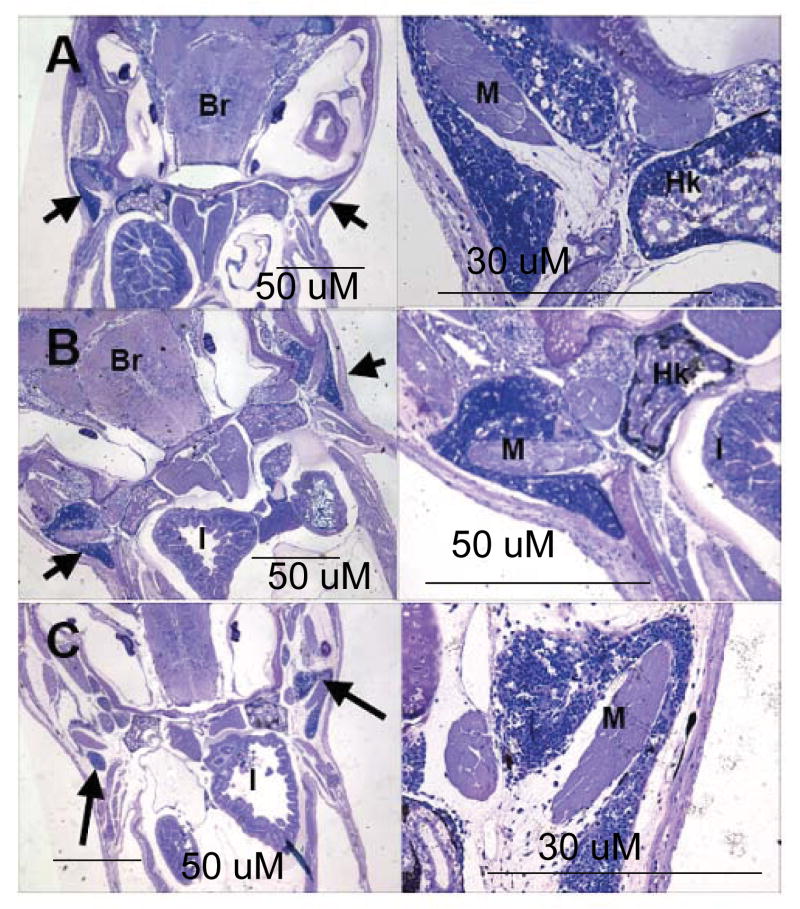

The thymus of developing mummichogs was closely associated with the pharyngeal epithelium and in close proximity to the head kidney. Thus, it was possible to observe the thymus while observing the head kidney. Thymic tissues appeared lymphoid at 3-wph in oblique and sagital sections of juvenile mummichog (Fig. 3 (a)). In all sections from 3-wph to 5-wph, the thymus appeared as a paired dorsal organ located posterior to the gill cavity in close proximity to the head kidney, and each organ wrapped around a muscle bundle (Fig. 3). The thymus and the head kidney were separated by sparse connective tissue and cartilage. At 3-wph, the thymic parenchyma consisted of a dense meshwork of small round basophilic staining cells. Due to their large nucleus to cytoplasm ratio the cells were probably immature thymocytes or lymphoblasts. From 3- to 5-wph, the thymus did not appear to change in size or cellularity. A clear demarcation between the thymic cortex and medulla could not be distinguished in any of the sections.

Fig. 3.

Appearance of lymphoid tissues in the thymus of the mummichog. Oblique sections (1.5 μM) of 3-wph (a), 4-wph (b), and 5-wph (c) whole mummichog. For each age, low magnification is on the left while high magnification is on the right. Thymic lobes are indicated by black arrows. Hk: head kidney, M: muscle, Br: brain, I: intestine. Size bars for each section are shown.

The first appearance of lymphoid organs was as follows: renal tubules in the head kidney at 7-dpf, hematopoietic tissue in the head kidney at 1-dph, appearance of spleen at 1-wph, and the appearance of lymphocytes in the thymus 3-wph (Table 1). It should be noted that whilst the appearance of tissues was noted, the tissues were not considered “lymphoid” until cells of the lymphoid lineage had infiltrated the tissue. For example, the head kidney structures had begun to appear as early as 7-dpf, but substantial lymphopoietic cells were not observed until 1-wph (Fig. 1 a,b; Table 1).

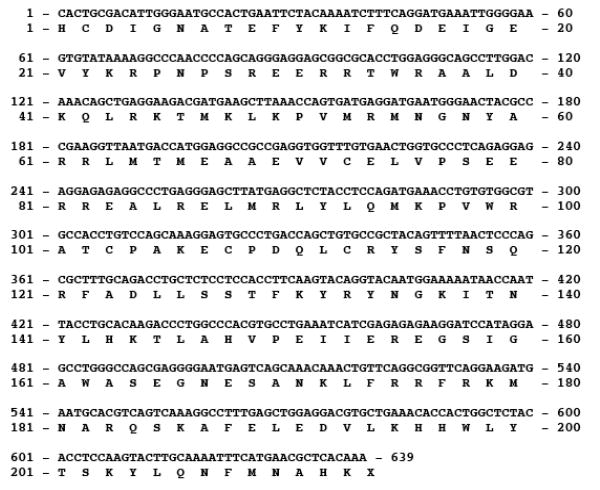

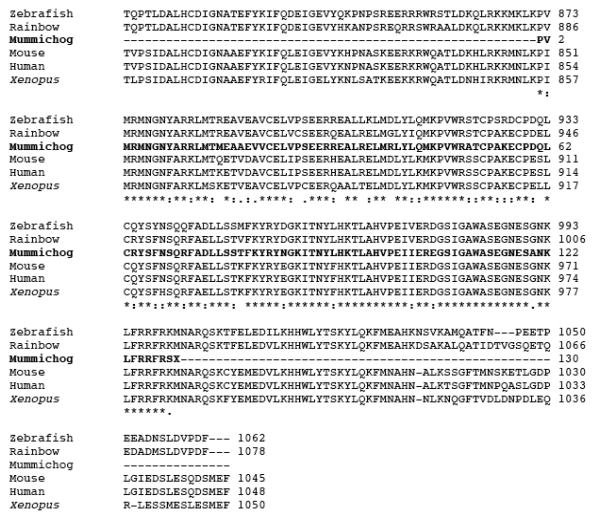

Using degenerate primers, a 639 nucleotide portion of mummichog Rag-1 was cloned from the genomic DNA and sequenced (Fig. 4). The mummichog Rag-1 genomic DNA sequence has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number DQ250438. Using specific primers, the cDNA sequence was obtained and sequenced, which encodes a protein of ∼15 kDa in size. The deduced amino acid sequence for mummichog Rag-1 cDNA was aligned with known Rag-1 sequences from zebrafish, rainbow trout, mouse, human, and Xenopus (Fig. 5), and shown to be 86% identical to rainbow trout, 85% to zebrafish, 81% to human, 81% to mouse, and 78% African clawed frog, with the highest homology in the “core” region.

Fig. 4.

Partial nucleotide and deduced amino acid sequences of Fundulus heteroclitus genomic Rag-1. The mummichog Rag-1 sequence has been deposited in the GenBank database under accession number DQ250438.

Fig. 5.

Amino acid sequence of Mumichog Rag-1 cDNA compared with that of of zebrafish, rainbow trout, mouse, human, and Xenopus Rag-1 using ClustalW. (*) indicates identity with the mummichog sequence; (-) indicates gap in sequence; (:) indicates residues that are approximately the same size and the hydropathy; (.) indicates where size or hydropathy has been conserved. The mummichog sequence is highlighted in bold.

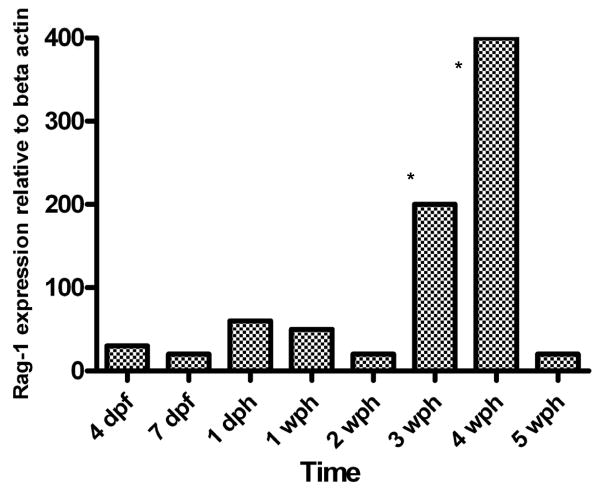

Expression of Rag-1 was quantified using real time PCR and normalized to the expression of the housekeeping gene β-actin. A melt curve analysis was performed for each quantitative real-time PCR run and a single specific melting peak was observed indicating amplification specificity (data not shown). During mummichog development, Rag-1 expression increased at 2-wph and reached a maximum intensity at 3-wph. After 3-wph, Rag-1 expression dropped precipitously to pre-2 wph levels, where upon expression levels remained constant throughout the study period (Fig. 6). These data were reported as levels of Rag-1 expression relative to expression of β-actin.

Fig. 6.

Quantitative expression of whole embryo or whole body Rag-1 expression from mummichogs, aged 4- and 7-days post-fertilization, 1-day post-hatch, and 1-, 2-, 3- 4-, and 5-weeks post-hatch. Bar heights represent the mean of Rag-1 expression relative to that of β-actin. * denotes p ≤ 0.01 when comparing means to those of 4-dpf.

Discussion

The kidney was the first organ of the mummichog immune system to contain putative cells of the lymphocyte lineage. Though renal tubules were present at 7-dpf, cells with hematopoietic morphological features were not observed in the head kidney until 1-wph. This is similar to what has been found in the gilthead seabream, where renal tubules appeared in 2 day old fish, but hematopoietic cells were not present until 4 days later (Mulero et al., 2006). As the juvenile mummichog aged in this study, both the number of renal tubules and the proportion of hematopoietic tissue increased. This has also been reported in Atlantic cod (Schroder et al., 1998) and turbot (Padrós and Crespo, 1996). The mummichog spleen contained mainly erythrocytes, but cells of the lymphocyte lineage were not observed in the spleen during this 5-week study. Thus, the spleen at 5-wph was still relatively immature in appearance and lacked elements of maturity such as MMCs, which have been found in adult gulf killifish spleens (Marsh, 2007), a close relative of the mummichog. Similarly, a lack of spleen lymphoid maturity has been reported in the flounder, Platichthys flesus, in which the spleen did not have mature attributes until well into the adult stage (Pulsford et al., 1994).

The thymus appeared lymphoid by containing lymphoid cells at 3-wph in developing mummichogs, and was located posterior to the gill cavity and continuous with the pharyngeal epithelium. Continuity between the thymus and the pharyngeal epithelium is characteristic of teleosts (Iwama and Nakanishi, 1996; Zapata et al., 2006). In this study, thymic cortex and medulla were not distinguishable, which is attributed to the lack of specific markers for thymocytes, due to age, or perhaps because corticomedullary regionalization does not occur in this teleost. In carp, the structure of the cortex and medulla were not well defined histologically until a specific marker was utilized with immunohistochemistry (Romano et al., 1999). From 3- to 5-wph, the mummichog thymus was mainly composed of basophilic staining cells, which had large nucleus to cytoplasm ratios. These cells were presumably lymphoblasts or immature thymocytes. Similar cell types have been described in the turbot at 15-25 dph (Padrós and Crespo, 1996).

The thymus rapidly appeared lymphoid in mummichog larvae from 3- to 5- wph. Such developmental patterns and rate of development is similar to what has been described in marine teleosts. The teleostean thymus typically undergoes thymic involution with age, although the details and progression of involution are not well understood (Iwama and Nakanishi, 1996; Zapata et al., 2006). In these studies, thymus involution was not observed at 5 wph, which is probably too early for involution to occur. Thus, the age at which thymus involution occurs in mummichog is yet to be determined.

Native Rag-1 protein is approximately 121 kDa in zebrafish (NP571464) and rainbow trout (AAA80281), and approximately 119 kDa in mice (NP033045) and humans (NP000439). Such a high degree of homology among vertebrates substantiates the theory that a key factor in the evolution of specific immunity (BCR and TCR) was the appearance of Rag-genes in early vertebrate lineages (Du Pasquier, 2004). The highest homology between the amino acid sequence of mummichog Rag-1 and that of rainbow trout, zebrafish, mouse, human, and Xenopus is primarily concentrated in the carboxyl-terminal two-thirds of the protein. The highly conserved carboxyl-terminal segment comprises the Rag-1 “core” region (Willett et al., 1997a). Notably, the core region is considered to be essential for recombination of artificial constructs in vitro, which is responsible for nuclear targeting and DNA binding. The core region corresponds to amino acid residues 1-130 of the mummichog Rag-1 amino acid sequence.

Quantitative real-time PCR showed an elevation in Rag-1 expression at 2-wph, followed by an increase to a maximum intensity at 3-4-wph, after which expression declined to pre 2-wph levels for the duration of the study period. The observed peak in Rag-1 expression at 3-4-wph may be due to the appearance of putative lymphocytes in the thymus at 3-4-wph and/or the expansion of lymphopoietic cells in the head kidney. In fish, in situ hybridization has been the primary technique for analyzing tissue localization of Rag-1 expression. In zebrafish, Rag-1 expression is detected in the pancreas by 4-dpf (Danilova and Steiner, 2002), thymus at 4-dpf (Willett et al., 1997b), and head kidney at 2-4 wpf (Lam et al., 2004). Lam et al., (2004) reported that in zebrafish the rapid increase in Rag-1 expression levels between 1- and 3- wpf is contributed to an expansion in the thymocyte population as well as lymphocytes in the head kidney between 2- and 4- wpf. In carp, the appearance of the thymus coincided with a rapid increase in Rag-1 expression at 4-dpf and presumably the rearrangement of TCR (Huttenhuis et al., 2005). However, Huttenhuis et al. noted that the appearance of Rag-1 expression does not indicate the formation of functional T cells at that particular time. Perhaps future studies using antibodies against recombinant mummichog Rag-1 protein will allow IHC-localization in fixed tissues.

In general, many marine species hatch with a relatively large yolk sac and under-developed organs (Falk-Petersen, 2005). Once hatched, mummichogs develop slowly and go thru several morphological changes before they are considered adults. Slow growth might not be critical for the mummichog, which is an opportunistic omnivore in an energy rich environment (Radtke and Dean, 1979). Yolk sac absorption occurs at stage 39 in mummichogs (Armstrong and Child, 1965), which is approximately 2 wph, a period when many teleosts undergo a transition from the yolk sac stage to a free feeding larval stage. In larval mummichogs, this stage results in a decrease in feeding, which may indicate a shift in metabolism (Radtke and Dean, 1979). Such decreases in feeding may be one reason why mummichogs do not develop humoral immune capabilities at this stage. The relatively slow pace of lymphoid organ development and maturation in mummichog has been also demonstrated in a number of other marine teleosts whose larvae hatch at a less advanced stage of development and undergo a relatively long period of metamorphis (Chantanachookhin et al., 1991).

There is a general agreement within the literature that the head kidney of marine fish develops prior to the thymus, but that the thymus is the first to become lymphoid. Needless to say, postulating defined developmental steps for lymphoid ontogeny in teleostean fishes should be approached with caution. Reports in the literature are sometimes inconsistent when defining milestones in organ development. In particular, some report the appearance of small lymphocytes in the thymus as the first checkpoint (Solomom, 1978) while others consider the appearance of the alymphoid thymic analge as the first milestone (Boehm et al., 2003). Furthermore, discrepancy also occurs in the age that organs are reported to appear. Overall, it may be that sequence of development is more important than the exact age that an organ develops. Age may not be a good indicator of developmental status in fish due to differences in genetic plasticity, temperature, salinity, and early life history strategies.

In this study, cells of the lymphoid lineage were present in the head kidney prior to the appearance of lymphopoietic cells in the thymus, and the thymus was the last to appear lymphoid. Furthermore, the thymus was always found in close proximity to the head kidney, which may enable lymphoietic cells from the head kidney to “seed” the thymus. It has been hypothesized by others that hematopoietic cells from the head kidney colonize the rudiment thymus, possibly thru cell bridges between the thymus and kidney (Padrós and Crespo, 1996; Liu et al., 2004). However, it should be noted that this is purely speculative at this time and needs further attention. Overall, the presence of hematopoietic cells in the head kidney, prior to the appearance of a “lymphoid” thymus, reiterates the notion that the head kidney is the primary hematopoietic organ in teleosts.

The mechanics of lymphoid organ development are similar among teleosts, but there are differences with respect to the timing and sequence of events. These differences may be attributed to variability in early life history strategy, genetic plasticity, or environmental factors. Unlike higher vertebrates, many fish hatch at the embryonic stage of life and must undergo substantial changes before being considered adult. Furthermore, juvenile fish have little immunocompetence at hatching, in that the lymphoid system is still developing and not all the structures and functions are present, and most likely rely on innate immunity for immune defense, which is likely the case for mummichogs. Though mummichogs are euryhaline and thermally-tolerant, they appeared to follow a similar pattern and pace to stenohaline marine teleost lymphoid organ development. To the author's knowledge, this is the first report that the lymphoid organs of high marsh estuarine fish develop in a similar sequence and pattern of strictly marine fish.

Table 3.

Oligonucletide primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR

| Primer name | Sequences (5′-3′) | Tm C° | Product size |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rag-1 Forwarda | GGAACTACGCCCGAAGGTTAAT | 56.7 | 131bp |

| Rag-1 Reversea | ACGCCACACAGGTTTCATCT | 56.7 | 131bp |

| β-actin Forwardb | TATGCAGAAGGAGATCACTGCC | 56.3 | 135bp |

| β-actin Reverseb | ATCCACATCTGCTGGAAGGT | 55.8 | 135bp |

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Dr. Marlee Marsh and Dr. Lee Ann Frederick for their valuable assistance with fish collection and maintenance. A sincere appreciation is extended to Dr. Steven Ellis's laboratory for valuable assistance with tissue preparations and histology.

Grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health (R15-ES10556-01) and by Clemson University Public Service Activity funds.

Abbreviations

- Rag-1

Recombination activation gene-1

- dpf

day post-fertilization

- wph

week post-hatch

- dph

day post-hatch

Literature Cited

- Armstrong PB, Child JS. Stages in the normal development of Fundulus heteroclitus. Biological Bulletin. 1965;128:143–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow HB, Schroeder WC. Fisheries Bulletin. Vol. 53. U.S.: 1953. Fishes of the Gulf of Maine; pp. 1–577. [Google Scholar]

- Boehm T, Bleul CC, Schorpp M. Genetic dissection of thymus development in mouse and zebrafish. Immunol Rev. 2003;195:15–27. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2003.00070.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnett KG, twenty six co-authors Fundulus as the primier teleost model in environmental biology: Opportunities for new insights using genomics. Comp Biochem Physiol Part D Genomics Proteomics. 2007;2:257–286. doi: 10.1016/j.cbd.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chantanachookhin C, Seikai T, Tanaka M. Comparative study of the ontogeny of the lymphoid organs in three species of marine fish. Aquaculture. 1991;99:143–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chenna R, Sugawara H, Koike T, Lopez R, Gibson TJ, Higgins DG, Thompson JD. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3497–3500. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danilova N, Steiner LA. B cells develop in the zebrafish pancreas. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13711–13716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212515999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Pasquier L. Speculations on the origin of the vertebrate immune system. Immunological Letters. 2004;92:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk-Petersen IB. Comparative organ differentiation during early life stages of marine fish. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 2005;19:397–412. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2005.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhalgh P, Olesen CE, Steiner LA. Characterization and expression of recombination activating genes (RAG-1 and RAG-2) in Xenopus laevis. J Immunol. 1993;151:3100–3110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JD, Kaattari SL. The recombination activation gene 1 (RAG1) of rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss): cloning, expression, and phylogenetic analysis. Immunogenetics. 1995;42:188–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00191224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen JD, Kaattari SL. The recombination activating gene 2 (RAG2) of the rainbow trout Oncorhynchus mykiss. Immunogenetics. 1996;44:203–211. doi: 10.1007/BF02602586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao S, Greeley MS, Wallace RA. Reproductive cycling in female Fundulus heteroclitus. Biological Bulletin. 1994;186:271–284. doi: 10.2307/1542273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang CY, Kanagawa O. Impact of early expression of TCR alpha chain on thymocyte development. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:1532–1541. doi: 10.1002/eji.200424870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttenhuis HBT, Huising MO, van der Meulen T, van Oosterhoud CN, Sanchez NA, Taverne-Thiele AJ, Stroband HWJ, Rombout JHWM. Rag expression identifies B and T cell lymphopoietic tissues during the development of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) Developmental & Comparative Immunology. 2005;29:1033–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwama G, Nakanishi T. The fish immune system: organism, pathogen, and environment. San Diego: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Kneib RT. The role of Fundulus heteroclitus in salt march trophic dynamics. American Zoologist. 1986;26:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Lam SH, Chua HL, Gong Z, Lam TJ, Sin YM. Development and maturation of the immune system in zebrafish, Danio rerio: a gene expression profiling, in situ hybridization and immunological study. Dev Comp Immunol. 2004;28:9–28. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(03)00103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Zhang S, Jiang G, Yang D, Lian J, Yang Y. The development of the lymphoid organs of flounder, Paralichthys olivaceus, from hatching to 13 months. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2004;16:621–632. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh MA. Dissertation. Clemson University; May, 2007. Histological examination of host parasite interactions in the gulf killifish Fundulus grandis. [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P, Iacomini J, Johnson RS, Herrup K, Tonegawa S, Papaioannou VE. RAG-1-deficient mice have no mature B and T lymphocytes. Cell. 1992;68:869–877. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90030-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulero I, Chaves-Pozo E, Garcia-Alcazar A, Meseguer J, Mulero V, Garcia Ayala A. Distribution of the professional phagocytic granulocytes of the bony fish gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata L.) during the ontogeny of lymphomyeloid organs andpathogen entry sites. Dev Comp Immunol. 2006;31(10):1024–33. doi: 10.1016/j.dci.2006.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oettinger MA, Schatz DG, Gorka C, Baltimore D. RAG-1 and RAG-2, adjacent genes that synergistically activate V(D)J recombination. Science. 1990;248:1517. doi: 10.1126/science.2360047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padrós F, Crespo S. Ontogeny of the lymphoid organs in the turbot Scophthalmus maximus: a light and electron microscope study. Aquaculture. 1996;144:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Petrie-Hanson L, Ainsworth AJ. Ontogeny of channel catfish lymphoid organs. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2001;81:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2427(01)00331-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsford A, Tomlinson MG, Lemaire-Gony S, Glynn PJ. Development and immunocompetence of juvenile flounders, Platichthys flesus L. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 1994;4:63–78. [Google Scholar]

- Radtke RL, Dean JM. Feeding, conversion efficiencies, and growth of larval mummichogs, Fundulus heteroclitus. Marine Biology. 1979;55:231–237. [Google Scholar]

- Reichman-Fried M, Hardy RR, Bosma MJ. Development of B-lineage cells in the bone marrow of scid/scid mice following the introduction of functionally rearranged immunoglobulin transgenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:2730–2734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano N, Taverne-Thiele AJ, Fanelli M, Baldassini MR, Abelli L, Mastrolia L, Van Muiswinkel WB, Rombout JH. Ontogeny of the thymus in a teleost fish, Cyprinus carpio L.: developing thymocytes in the epithelial microenvironment. Dev Comp Immunol. 1999;23:123–137. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(98)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadofsky MJ, Hesse JE, McBlane JF, Gellert M. Expression and V(D)J recombination activity of mutated RAG-1 proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:5644–5650. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.24.5644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder MB, Villena AJ, Jorgensen TO. Ontogeny of lymphoid organs and immunoglobulin producing cells in Atlantic cod (Gadus morhua L.) Dev Comp Immunol. 1998;22:507–517. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(98)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobacchi C, Marrella V, Rucci F, Vezzoni P, Villa A. RAG-dependent primary immunodeficiencies. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1174–1184. doi: 10.1002/humu.20408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomom JB. Immunological milestones in ontogeny. Dev Comp Immunol. 1978;2:409–424. doi: 10.1016/s0145-305x(78)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanopoulou E, Roman CA, Corcoran LM, Schlissel MS, Silver DP, Nemazee D, Nussenzweig MC, Shinton SA, Hardy RR, Baltimore D. Functional immunoglobulin transgenes guide ordered B-cell differentiation in Rag-1-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1030–1042. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett CE, Cherry JJ, Steiner LA. Characterization and expression of the recombination activating genes (rag1 and rag2) of zebrafish. Immunogenetics. 1997;45:394–404. doi: 10.1007/s002510050221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willett CE, Zapata AG, Hopkins N, Steiner LA. Expression of zebrafish rag genes during early development identifies the thymus. Dev Biol. 1997;182:331–341. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.8446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young F, Ardman B, Shinkai Y, Lansford R, Blackwell TK, Mendelsohn M, Rolink A, Melchers F, Alt FW. Influence of immunoglobulin heavy- and light-chain expression on B-cell differentiation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1043–1057. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zapata A, Diez B, Cejalvo T, Gutierrez-de Frias C, Cortes A. Ontogeny of the immune system of fish. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 2006;20:126–136. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]