Abstract

The epithelial cells lining intrahepatic bile ducts (i.e., cholangiocytes), like many cell types in the body, have primary cilia extending from the apical plasma membrane into the bile ductal lumen. Cholangiocyte cilia express proteins such as polycystin-1, polycystin-2, fibrocystin, TRPV4, P2Y12, AC6 that account for ciliary mechano-, osmo-, and chemosensory functions; when these processes are disturbed by mutations in genes encoding ciliary-associated proteins, liver diseases (i.e., cholangiociliopathies) result. The cholangiociliopathies include but are not limited to cystic and fibrotic liver diseases associated with mutations in genes encoding polycystin-1, polycystin-2, fibrocystin. In this review, we discuss the functions of cholangiocyte primary cilia, their role in the cholangiociliopathies, and potential therapeutic approaches.

Keywords: liver, cholangiocytes, primary cilia, mechanosensors, osmosensors, chemosensors, cholangiociliopathies

INTRODUCTION

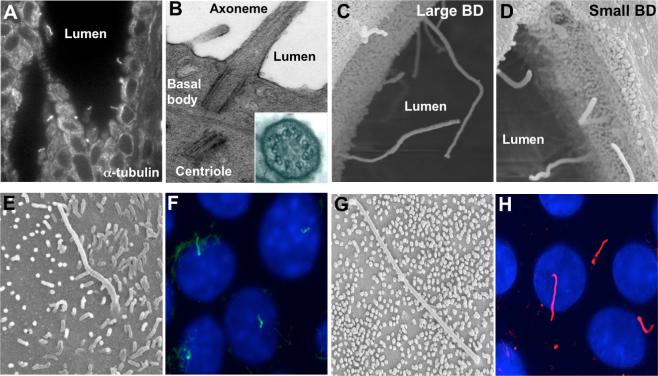

Cholangiocytes, the epithelial cells lining the lumen of intrahepatic bile ducts, are ciliated cells, i.e., each cholangiocyte has a primary cilium consisting of: (i) the microtubule-based axoneme that has a 9+0 pattern (i.e., nine peripheral microtubule doublets arranged around a central core that does not contain two central microtubules), and (ii) the basal body, a centriole-derived, microtubule-organizing center, from which the axoneme emerges (Figure 1). Primary cilia in cholangiocytes were described in the 1960s and 1970s [for references see (Huang et al., 2006; Masyuk et al., 2006a)], but their physiologic significance remained unclear until recently.

Figure 1. Cholangiocyte primary cilia.

Light transmission (A) and transmission electron microscopy (B) micrographs of primary cilia extending from the cholangiocyte apical plasma membrane into the ductal lumen. The insert in B shows a 9+0 pattern of the ciliary axoneme. In A, cilia were stained with an antibody to the ciliary marker, acetylated α-tubulin. Scanning electron microscopy images of primary cilia in large (C) and small (D) bile ducts in the rat liver. In the large bile ducts (C), cilia are approximately 2 times longer than in the small bile ducts (D). Scanning electron microscopy (E and G) and immuno-fluorescence confocal microscopy (F and H) images of primary cilia in normal mouse (E and F) and rat cholangiocyte cell lines grown on a collagen gel for 10−14 days after confluence. In F and H, cilia were stained with acetylated α-tubulin (green and red, respectively), nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Images A-D are reproduced from (Hunag et al., 2006) with permission. Image G is reproduced from (Muff et al., 2006) with permission.

Cholangiocyte cilia extending from the apical plasma membrane into the bile duct lumen are ideally positioned to detect changes in bile flow, composition and osmolality, i.e., to be sensory organelles that may control cholangiocyte functions such as ductal bile formation. Bile is an aqueous solution of organic and inorganic compounds initially secreted by hepatocytes (primary bile) and subsequently modified by cholangiocytes (ductal bile) through secretory and absorptive processes. Cholangiocytes modify the fluidity and alkalinity of primary bile by secreting ions, primarily Cl− and HCO3−, and by absorbing bile salts, glucose and amino acids followed by passive movement of water into or out of the bile duct lumen depending on osmotic gradients. Cholangiocytes are also the target of both acquired and inherited liver diseases (i.e., the cholangiopathies), and abnormalities in ciliary structure and functions are responsible for cholangiopathies such as polycystic liver disease that occurs in combination with Autosomal Dominant and Autosomal Recessive Polycystic Kidney Disease (i.e., ADPKD and ARPKD) (Masyuk and LaRusso, 2006). Thus, it is evident that cholangiocyte primary cilia play important roles in liver health and disease.

CHOLANGIOCYTE CILIA IN LIVER HEALTH

In rat liver, primary cilia are heterogeneous in length along the biliary tree axis (Huang et al., 2006). In the large bile ducts (i.e., those with an inner diameter of 100 μm or more), the ciliary axonemes are 7.35±1.32 μm in length, approximately two times longer than in the small bile ducts (i.e., 3.58±1.12 μm in length) with an inner diameter of 50 μm or smaller (Figure 1). The basal bodies of cholangiocyte cilia are heterogeneous as well and range in diameter from 0.14 μm to 0.26 μm and in length from 0.26 μm to 0.48 μm in the small and large bile ducts, respectively (Huang et al., 2006). Since the intrahepatic biliary tree is heterogeneous along its axis with regard to bile duct diameter, cholangiocyte size, expression of proteins, and functional responses to exogenous stimuli (Masyuk et al., 2006a), primary cilia in small and large bile ducts may also be functionally heterogeneous.

In normal rat and mouse cholangiocyte cell lines (NRCs and NMCs, respectively), primary cilia appear at day 3 of post-confluence and grow progressively to the maximal length of ∼7−10 μm up to day 10 when the majority of cells possess cilia (Figure 1) (Huang et al., 2006).

Several lines of evidence suggest that the major physiologic role of primary cilia is to function as sensory organelles. The concept of sensory functions of primary cilia has been developed in the latter part of the 20th century and proposed that primary cilia may sense and transduce multiple stimuli, such as fluid flow, signals initiated by hormones, morphogens, growth factors and other physiologically active substances present in the environment surrounding the cell, and changes in osmolality of the extracellular milieu, i.e., that they function as mechano-, chemo-, and osmo-sensory organelles [for early references see (Poole et al., 1985; Praetorius and Spring, 2005; Wheatley, 2005; Christensen et al., 2007; Satir and Christensen, 2007)]. As a result, a primary cilium is often referred to as “a cellular cybernetic probe” (Poole et al., 1985), “a cellular global positioning device” (Benzing and Walz, 2006), “ an antenna” (Pazour and Witman, 2003; Marshall and Nonaka, 2006; Singla and Reiter, 2006) to emphasize the unique sensory properties of this organelle.

Cholangiocyte cilia are mechanosensors

The first evidence that primary cilia function as mechanosensors was observed in experiments on renal epithelial cells. In MDCK cells, a cell line derived from the collecting duct of canine kidney, bending of a single cilium by a micropipette or by alterations in perfusate flow rates increased intracellular Ca2+ ([Ca2+]i) while pharmacological removal of cilia abolished the flow-induced [Ca2+]i increase (Praetorius and Spring, 2001; Praetorius and Spring, 2002). This mechanosensory capacity of primary cilia is provided by the ciliary-associated proteins, polycystin-1 (PC-1), a cell surface receptor, and polycystin-2 (PC-2), a Ca2+ channel, which are thought to form a functional mechanosensory complex (Nauli et al., 2003).

Bending of cholangiocyte cilia by luminal fluid flow in microperfused intrahepatic bile ducts also induces an increase in [Ca2+]i, which depends on PC-1, PC-2 and both extracellular and intracellular Ca2+ sources. Moreover, the mechanosensory functions of cholangiocyte cilia are not limited to transmitting luminal mechanical fluid flow stimuli into [Ca2+]i signaling response but also occur through cAMP signaling with the involvement of Ca2+-inhibitable adenylyl cyclase 6 (AC6), which is expressed in ciliary axoneme (Masyuk et al., 2006b).

Cholangiocyte cilia are osmosensors

Our initial knowledge on osmosensory functions of primary cilia is based on studies on the nematode, C. elegans, showing that a putative TRP (Transient Receptor Potential)-like channel protein, OSM-9, is expressed in primary cilia in worm sensory neurons where it functions as an osmosensor (Tobin et al., 2002). A mammalian homolog of OSM-9 is a Transient Receptor Potential Vaniloid 4 (TRPV4) channel exquisitely sensitive to minute changes in osmolality of extracellular milieu, being activated by extracellular hypotonicity and inhibited by extracellular hypertonicity (Liedtke, 2006). Activation of TRPV4 results in an increase in [Ca2+]i through influx of extracellular Ca2+ into the cell (Plant and Strotmann, 2007). In epithelial cells lining the oviduct, TRPV4 is localized to motile cilia, where it may perform multiple roles linked to osmosensory, chemosensory and mechanosensory ciliary functions (Andrade et al., 2005; Teilmann et al., 2005).

Recently, we demonstrated that TRPV4 is localized to cholangiocyte primary cilia and is involved in functional responses of cholangiocytes to changes in bile osmolality. Exposure of cholangiocytes to hypotonicity results in an increase in intracellular Ca2+, which depends on extracellular Ca2+ sources. Changes in luminal tonicity also induce TRPV4- and ciliary-dependent cholangiocyte ATP release and bicarbonate secretion, suggesting an important role of osmosensory function of cholangiocyte cilia in ductal bile formation. Indeed, a retrograde infusion of 4αPDD, an agonist to TRPV4, into rat intrahepatic bile ducts in vivo resulted in stimulated ductal bile secretion; this effect of 4αPDD was abolished by Gd3+, a TRP channel inhibitor (Gradilone et al., 2007).

Cholangiocyte cilia are chemosensors

In general, to function as chemosensory organelles, primary cilia must express proteins that will recognize appropriate ligands, and be able to transduce signals induced by ligands into the cell. For example, in C. elegans, primary cilia in sensory neurons possess specific G-protein-coupled receptors that detect molecular stimuli, such as attractants, repellents, or pheromones (Bargmann, 2006). Activation of these ciliary chemoreceptors induces an increase in cGMP, which in turn triggers the opening of cGMP-gated channels, thus, transducing signals into neuronal activity via the cGMP-signaling pathway. In mammals, chemosensory functions of neuronal primary cilia likely occur via receptors, such as somatostatin receptor 3 (sst3) and 5-HT6 serotonin receptor (Handel et al., 1999; Brailov et al., 2000; Whitfield, 2004) not uniquely expressed in cilia. The ubiquitous receptors are also localized to primary cilia in other cell types, including chondrocytes, fibroblasts, epithelial cells in oviduct and kidney (Praetorius et al., 2004; McGlashan et al., 2006; Christensen et al., 2007). Moreover, in fibroblasts, primary cilia possess proteins involved in the PI3-kinase/Akt and Mek1/2-Erk1/2 signaling cascades, and thus have all the necessary components to account for a chemosensory capacity (Schneider et al., 2005; Christensen et al., 2007).

Chemosensation by cholangiocyte cilia occurs with the involvement of P2Y12, a receptor that is activated by biliary nucleotides (i.e., ATP and ADP) causing changes in intracellular cAMP levels. (Masyuk et al., 2007b). Cholangiocyte cilia also contain the components of the AKAP (A-kinase anchoring protein) signaling complex, which include three isoforms of adenylyl cyclase (i.e., AC4, AC6, and AC8), AKAP150, two isoforms of protein kinase A (i.e., PKAII alpha, PKAI beta) and one isoform of EPAC, an exchange protein directly activated by cAMP (i.e., EPAC2), suggesting the importance of the cAMP signaling cascade in ciliary chemosensory function (Masyuk et al., 2007a).

A working model depicted in Figure 2 summarizes mechano-, osmo-, and chemosensory functions of cholangiocyte cilia. In response to mechanical stimuli (i.e., bile flow), ciliary-associated PC-1 and PC-2 form a functional complex providing entry of extracellular Ca2+, which in turn suppresses cAMP levels in cholangiocytes via ciliary-associated AC6 (Masyuk et al., 2006b).In response to osmo-stimuli (i.e., changes in bile tonicity), ciliary-associated TRPV-4 is activated when bile tonicity decreases or inhibited when bile tonicity increases, causing changes in [Ca2+]i which in turn affects cholangiocyte ATP release via an as yet obscure mechanism (Gradilone et al., 2007). Both biliary ATP, released by hepatocytes and/or cholangiocytes, and a product of ATP degradation, ADP, represent potential chemo-stimuli in bile that activate ciliary P2Y12 linked to the cAMP signaling cascade (Masyuk et al., 2007b). Under specific conditions, ciliary-associated fibrocystin is cleaved and its C-terminal tail (FCCT) is translocated into the nucleus, where it may regulate expression of genes crucial for cholangiocyte functions (Hiesberger et al., 2006).

Figure 2. A working model of sensory functions of cholangiocyte cilia.

See text for details. Dashed lines indicate unknown mechanisms.

The physiological implications of mechano-, osmo-, and chemo- sensory functions of cholangiocyte cilia are being elucidated. It is likely that primary cilia in biliary epithelia provide a previously obscure apically-located, regulatory mechanism affecting ductal bile formation. Physiologically, bile flow in intrahepatic bile ducts is thought to be pulsatile and, thus, the minute-to-minute changes in bile flow may alter the mechanical forces to which cholangiocyte cilia are exposed, and, as a result, affect cholangiocyte secretory and absorptive functions. Changes in bile osmolality may also have regulatory significance. Bile is considered isotonic; however, given that cholangiocytes are both secretory and absorptive cells, it seems plausible that their secretory and absorptive functions can generate transient changes in ductal bile tonicity that could affect (i.e., activate or inhibit) ciliary osmosensory protein (i.e., TRPV4). The activation or inhibition of ciliary TRPV4, in turn, would induce or inhibit ion and water transport by cholangiocytes, restoring the isotonicity of ductal bile. In addition, changes in bile flow and tonicity may induce ATP release by cholangiocytes, which in turn will activate ciliary P2Y12 and coordinate ductal bile formation via the intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling pathways (Masyuk et al., 2006b; Gradilone et al., 2007; Masyuk et al., 2007a).

CHOLANGIOCYTE PRIMARY CILIA IN LIVER DISEASE

Mutations in genes encoding ciliary-associated proteins cause a broad spectrum of clinically and genetically heterogeneous human disorders, referred to as ciliopathies (Badano et al., 2006; Fliegauf et al., 2007). Ciliopathies affecting liver may more appropriately be called “cholangiociliopathies” since cholangiocytes are the only epithelial cells in the liver that contain primary cilia (i.e., hepatocytes do not express cilia). Cholangiociliopathies include cystic and/or fibrotic liver diseases such as Autosomal Dominant Polycystic Kidney Disease [(ADPKD) caused by mutations in either PKD1 or PKD2, genes that encode PC-1 and PC-2, respectively], Autosomal Recessive PKD [(ARPKD), caused by mutations in a single gene, PKHD1, that encodes fibrocystin], Nephronophthisis [(NPHP) caused by mutations in six genes NPHP1−6 that encode nephrocystins 1−6], Bardet-Biedl Syndrome [(BBS) caused by mutations in 12 BBS genes that encode BBS1−12] and Meckel-Gruber Syndrome [(MKS), caused by mutations in three MKS1−3 genes that encode MKS1 and meckelin] (Fliegauf et al., 2007; Adams et al., 2008). ADPKD is characterized by massive progressive cyst development in liver while major features of ARPKD and MKS are biliary dysgenesis, hepatic fibrosis and cystogenesis (Figure 3). In contrast, NPHP and BBS are mainly associated with congenital hepatic fibrosis (Masyuk et al., 2003; Masyuk et al., 2004) (Masyuk and LaRusso, 2006).

Figure 3. Liver manifestation of ARPKD-an example of cholangiociliopathies.

Light microscopy images of normal (A) and PCK (B) rat liver tissues stained with hematoxylin and eosin show healthy liver (A) and liver with large numerous cysts (B). Light microscopy image of PCK rat liver tissue stained with picrosirius red shows the presence of hepatic fibrosis around hepatic cysts (C). Scanning electron microscopy images of normal (D) and PCK (E and F) rat liver tissues show healthy liver with a conventional biliary triad (BT) consisting of the portal vein, hepatic artery and intrahepatic bile duct (D), and unhealthy liver in which cysts replace most of the liver parenchyma (E and F). A higher magnification of a portion of the liver cyst (E, the white box) is shown in F. Epithelial cells lining cysts are cholangiocytes in origin; they contain primary cilia, which are functionally abnormal due to mutation in Pkhd1encoding fibrocystin.

Defects in ciliary structure and/or their integrated sensory/transducing functions appear to result in decreased [Ca2+]i and increased cAMP causing cholangiocyte hyperproliferation, abnormal cell-matrix interactions, and altered fluid secretion/absorption, clearly distinguishable cellular events, capable of resulting in cystogenesis. Understanding the key mechanisms regulating sensory/transducing functions of cholangiocyte cilia or the phenotypic manifestations of these functions (i.e., the concentrations of intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP), should facilitate the development of targeted therapy to prevent or halt cystogenesis. Indeed, we recently showed that treatment of PCK rats (an animal model of ARPKD) with octreotide, the synthetic analog of somatostatin, decreases cAMP levels in cholangiocytes, suppressing hepatic cyst growth and reducing hepatic fibrosis (Masyuk et al., 2007c), a clinical trail is underway to assess this therapeutic approach in humans.

PERSPECTIVES

Our brief overview on cholangiocyte primary cilia suggests that these organelles are important in liver health and disease. Cholangiocyte cilia function as mechano-, osmo-, and chemosensors in intrahepatic bile ducts; when their structure and/or functions are affected by mutations in genes encoding ciliary-associated proteins, the cholangiociliopathies result. Further studies on cholangiocyte cilia should address the molecular mechanisms by which cilia sense biliary stimuli and transduce them into intracellular signaling and should clarify functional responses that result.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant DK24031 to Dr. N. F. LaRusso) and by the Mayo Foundation

REFERENCES

- Adams M, Smith UM, Logan CV, Johnson CA. Recent advances in the molecular pathology, cell biology and genetics of ciliopathies. J Med Genet. 2008 doi: 10.1136/jmg.2007.054999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade YN, Fernandes J, Vazquez E, Fernandez-Fernandez JM, Arniges M, Sanchez TM, Villalon M, Valverde MA. TRPV4 channel is involved in the coupling of fluid viscosity changes to epithelial ciliary activity. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:869–874. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badano JL, Mitsuma N, Beales PL, Katsanis N. The Ciliopathies: An Emerging Class of Human Genetic Disorders. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2006;7:125–148. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.7.080505.115610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benzing T, Walz G. Cilium-generated signaling: a cellular GPS? Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2006;15:245–249. doi: 10.1097/01.mnh.0000222690.53970.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brailov I, Bancila M, Brisorgueil MJ, Miquel MC, Hamon M, Verge D. Localization of 5-HT(6) receptors at the plasma membrane of neuronal cilia in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2000;872:271–275. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen ST, Pedersen LB, Schneider L, Satir P. Sensory cilia and integration of signal transduction in human health and disease. Traffic. 2007;8:97–109. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2006.00516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fliegauf M, Benzing T, Omran H. When cilia go bad: cilia defects and ciliopathies. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:880–893. doi: 10.1038/nrm2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gradilone SA, Masyuk AI, Splinter PL, Banales JM, Huang BQ, Tietz PS, Masyuk TV, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia express TRPV4 and detect changes in luminal tonicity inducing bicarbonate secretion. PNAS. 2007;104:19138–19143. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705964104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handel M, Schulz S, Stanarius A, Schreff M, Erdtmann-Vourliotis M, Schmidt H, Wolf G, Hollt V. Selective targeting of somatostatin receptor 3 to neuronal cilia. Neuroscience. 1999;89:909–926. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(98)00354-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiesberger T, Gourley E, Erickson A, Koulen P, Ward CJ, Masyuk TV, Larusso NF, Harris PC, Igarashi P. Proteolytic cleavage and nuclear translocation of fibrocystin is regulated by intracellular Ca2+ and activation of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34357–34364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606740200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang BQ, Masyuk TV, Muff MA, Tietz PS, Masyuk AI, Larusso NF. Isolation and characterization of cholangiocyte primary cilia. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G500–509. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00064.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liedtke W. Transient receptor potential vanilloid channels functioning in transduction of osmotic stimuli. J Endocrinol. 2006;191:515–523. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.07000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WF, Nonaka S. Cilia: tuning in to the cell's antenna. Curr Biol. 2006;16:R604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk AI, Banales JM, Gradilone SA, Masyuk TV, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte primary cilia express the elements of the cAMP signaling cascade necessary for ciliary sensory functions. Molecular Biology of the cell. 2007a in press. [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk AI, Gradilone SA, Banales JM, Lee S-O, Masyuk TV, Huang BQ, Harris PC, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte primary cilia function as chemosensory organelles. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007b;18:132A. [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, LaRusso NF. Physiology of cholangiocytes. In: Johnson Leonard R., editor. Physiology of the gastrointestinal tract. Fourth Edition 2006a. pp. 1505–1533. [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk AI, Masyuk TV, Splinter PL, Huang BQ, Stroope AJ, LaRusso NF. Cholangiocyte cilia detect changes in luminal fluid flow and transmit them into intracellular Ca2+ and cAMP signaling. Gastroenterology. 2006b;131:911–920. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk T, LaRusso N. Polycystic liver disease: new insights into disease pathogenesis. Hepatology. 2006;43:906–908. doi: 10.1002/hep.21199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk TV, Huang BQ, Masyuk AI, Ritman EL, Torres VE, Wang X, Harris PC, Larusso NF. Biliary dysgenesis in the PCK rat, an orthologous model of autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1719–1730. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63427-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk TV, Huang BQ, Ward CJ, Masyuk AI, Yuan D, Splinter PL, Punyashthiti R, Ritman EL, Torres VE, Harris PC, LaRusso NF. Defects in cholangiocyte fibrocystin expression and ciliary structure in the PCK rat. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1303–1310. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masyuk TV, Masyuk AI, Torres VE, Harris PC, Larusso NF. Octreotide inhibits hepatic cystogenesis in a rodent model of polycystic liver disease by reducing cholangiocyte adenosine 3',5'-cyclic monophosphate. Gastroenterology. 2007c;132:1104–1116. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGlashan SR, Jensen CG, Poole CA. Localization of extracellular matrix receptors on the chondrocyte primary cilium. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1005–1014. doi: 10.1369/jhc.5A6866.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, Elia AE, Lu W, Brown EM, Quinn SJ, Ingber DE, Zhou J. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nat Genet. 2003;33:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazour GJ, Witman GB. The vertebrate primary cilium is a sensory organelle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2003;15:105–110. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00012-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plant TD, Strotmann R. Trpv4. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2007:189–205. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-34891-7_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poole CA, Flint MH, Beaumont BW. Analysis of the morphology and function of primary cilia in connective tissues: a cellular cybernetic probe? Cell Motil. 1985;5:175–193. doi: 10.1002/cm.970050302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius HA, Praetorius J, Nielsen S, Frokiaer J, Spring KR. Beta1-integrins in the primary cilium of MDCK cells potentiate fibronectin-induced Ca2+ signaling. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F969–978. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00096.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Bending the MDCK cell primary cilium increases intracellular calcium. J Membr Biol. 2001;184:71–79. doi: 10.1007/s00232-001-0075-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius HA, Spring KR. A physiological view of the primary cilium. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:515–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.101353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praetorius J, Spring KR. Specific lectins map the distribution of fibronectin and beta 1-integrin on living MDCK cells. Exp Cell Res. 2002;276:52–62. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satir P, Christensen ST. Overview of structure and function of mammalian cilia. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:377–400. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.040705.141236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider L, Clement CA, Teilmann SC, Pazour GJ, Hoffmann EK, Satir P, Christensen ST. PDGFRalphaalpha signaling is regulated through the primary cilium in fibroblasts. Curr Biol. 2005;15:1861–1866. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singla V, Reiter JF. The primary cilium as the cell's antenna: signaling at a sensory organelle. Science. 2006;313:629–633. doi: 10.1126/science.1124534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teilmann SC, Byskov AG, Pedersen PA, Wheatley DN, Pazour GJ, Christensen ST. Localization of transient receptor potential ion channels in primary and motile cilia of the female murine reproductive organs. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;71:444–452. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin D, Madsen D, Kahn-Kirby A, Peckol E, Moulder G, Barstead R, Maricq A, Bargmann C. Combinatorial expression of TRPV channel proteins defines their sensory functions and subcellular localization in C. elegans neurons. Neuron. 2002;35:307–318. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00757-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheatley DN. Landmarks in the first hundred years of primary (9+0) cilium research. Cell Biol Int. 2005;29:333–339. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2005.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield JF. The neuronal primary cilium--an extrasynaptic signaling device. Cell Signal. 2004;16:763–767. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]