Abstract

The RNA-binding protein (RBP) HuR plays a vital role in the mammalian stress response, effecting changes in the proliferation and survival of damaged cells. HuR prominently influences the stress response by regulating the stability and translation of mRNAs encoding stress-response proteins. Recently, HuR was found to affect mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling, at least in part by post-transcriptionally promoting the expression of MAPK phosphatase-1 (MKP-1). As anticipated for a pivotal regulator of the MAPKs c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and p38, MKP-1 expression is tightly regulated transcriptionally, post-transcriptionally and post-translationally. HuR’s influence on MKP-1 expression helps to ensure the appropriate abundance of MKP-1 and consequently the appropriate cellular response to stress stimuli.

Keywords: mRNA-binding protein, ribonucleoprotein complex, mRNA turnover, translational control, ELAV, MAP kinase, ERK, JNK, p38

HuR and the Mammalian Stress Response

In mammalian cells, HuR has been implicated in the response to many different types of damage. Initial evidence that HuR might be involved in the stress response came from correlative observations that exposure to toxic agents led HuR, a predominantly nuclear RBP, to accumulate in the cytoplasm. This cytoplasmic mobilization was observed in response to harmful stimuli such as oxidants [e.g., hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), arsenite], chemotherapeutic agents (e.g., prostaglandin A2), irradiation with short-wavelength ultraviolet light (UVC), nutrient depletion (e.g., polyamines), and inhibitors of transcription (e.g., actinomycin D).1–3 Given that specific machineries to degrade and translate mRNAs reside in the cytoplasm, the enhanced presence of HuR in this compartment was proposed as a mechanism whereby HuR could stabilize and translate specific subsets of target mRNAs under conditions of stress.4–9 Further evidence linking HuR to the stress response came from studies in which HuR levels were altered in cultured cells by either ectopic HuR overexpression or reduction of HuR levels. These perturbations revealed that elevating HuR abundance generally enhanced the cell’s ability to survive the damaging insult, while its reduction was often detrimental for the cell’s outcome.8,10–12 More recently, HuR’s role in the stress response was further tied to its post-translational modification. Phosphorylation of HuR at a region spanning RNA recognition motifs (RRMs) 1 and 2 by the checkpoint kinase Chk2 affected HuR’s ability to bind to target mRNAs, in turn affecting its post-transcriptional fate.10 In light of the influence of Chk2 on HuR binding to target mRNAs, the Chk2-mediated phosphorylation of HuR was proposed to modulate cell survival in response to stress conditions; however, this hypothesis is awaiting experimental testing.

HuR Influences the Expression of Stress-Response Proteins

HuR levels, cytoplasmic abundance and ability to bind target mRNAs together impact on the composition and concentration of HuR-mRNA ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes. As mentioned above, HuR’s stabilizing influence on target mRNAs, many of which encode stress-response proteins, has been extensively documented.3,4,13 Additionally, HuR can increase the translation of several target mRNAs under conditions of stress,7,8,12,14–17 although under non-stressed conditions, HuR can also function as a translational repressor.18–20.

Through its influence on gene expression patterns, HuR RNP complexes have been shown to modulate two major components of the stress response: cell proliferation and apoptosis. HuR can modify cell proliferation rates following damage by changing the levels of proteins that control the cell division cycle, including cyclins D1, A2 and B1, cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors p21 and p27, and transcription factors c-Fos, c-Jun, HIF-1α, ATF-2 and c-Myc.2,18,21–25 Similarly, HuR can modulate apoptosis through its influence on the expression of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins such as prothymosin-α, p53, nucleophosmin, Bcl-2, Mcl-1, SIRT1, cyclooxygenase-2, cytochrome c and VEGF.8,10,11,14,26,27 Collections of HuR-regulated proteins which alter cell proliferation and survival in response to stress, as well as the regulatory mechanisms involved are reported elsewhere.11,13,28,29 In addition to influencing cell proliferation and apoptosis, new evidence suggests that HuR could directly influence a third major aspect of the stress response: signaling through mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), as discussed next.

HuR Regulates MKP-1 Levels, MAPK Activity

Recently, HuR was also found to increase the levels of the stress-response protein MKP-1 [MAPK phosphatase-1, also named DUSP1, dual-specificity phosphatase 1], a critical regulator of MAPKs. MKP-1 specifically dephosphorylates and thereby inactivates MAPKs ERK (extracellular signal regulated kinase), JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) and p38. Through its phosphatase action, MKP-1 regulates the magnitude and duration of MAPK signaling. As other immediate-early genes, the short-lived MKP-1 mRNA is rapidly induced by different stresses. Treatment with the oxidant increased HuR levels in the cytoplasm and its association H2O2 with MKP-1 mRNA, in turn elevating the MKP-1 mRNA half-life and promoting its recruitment to the translation machinery. Conversely, HuR silencing diminished the H2O2-stimulated MKP-1 mRNA stability and lowered MKP-1 translation, while ectopic reintroduction of HuR rescued these effects.12 The decreased levels of MKP-1 in HuR-silenced cultures significantly enhanced the phos- porylation of JNK and p38 after H2O2 treatment.

These findings are particularly significant as they reveal an additional layer of influence by HuR during the stress response. Besides its direct post-transcriptional effect on stress mRNAs, HuR directly affects MKP-1 expression, thereby controlling the strength and timing of MAPK signaling cascades. Moreover, many stress-response genes are transcriptionally induced via MAPK-activated transcription factors. Together, a regulatory paradigm can be proposed in which stress signals activate both MAPKs and HuR; MAPKs carry out stress response functions, including the activation of transcription factors (TFs) which transcriptionally induce stress-response genes, while HuR post-transcriptionally increases the stability and/or translation of mRNAs encoding stress-response proteins. The synergistic action of MAPK/TFs and HuR is eventually shut-off with the rising levels of MKP-1, a consequence of the action of both MAPK/TFs and HuR (Fig. 1 and below). As MKP-1 dephosphorylates MAPKs (predominantly JNK and p38), it provides an effective mechanism of negative feedback regulation.

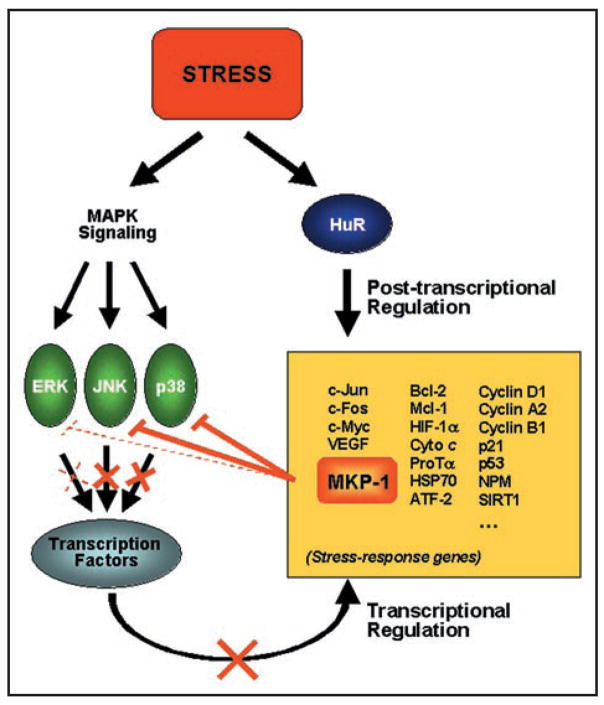

Figure 1.

Feedback Regulation Elicited by MKP-1. Stress agents broadly trigger signal transduction pathways that culminate in the activation of MAPKs (ERK, JNK, p38, green ovals). In turn, MAPKs phosphorylate numerous substrates including several transcription factors driving expression of stress-response genes (yellow box). Stress stimuli also act upon HuR, typically enhancing its cytoplasmic abundance and its association with mRNAs encoding stress-response proteins. Accordingly, stress-response genes are effectively induced via two synergistic processes: transcriptionally through the action of MAPKs and post-transcriptionally through the action of HuR. However, the expression of stress response proteins must be shut off with comparable efficiency. We propose that one of HuR post-transcriptional targets, MKP-1 (orange box), provides negative feedback control. MKP-1 dephosphorylates and thereby inactivates MAPKs (primarily JNK and p38), thereby blocking their ability to activate the transcription factors which induce stress-response genes (orange lines). These dynamic interactions permit the rapid induction and the effective repression of stress-response genes, through joint transcriptional and post-transcriptional processes.

Complexity of the Regulation of MKP-1 Levels

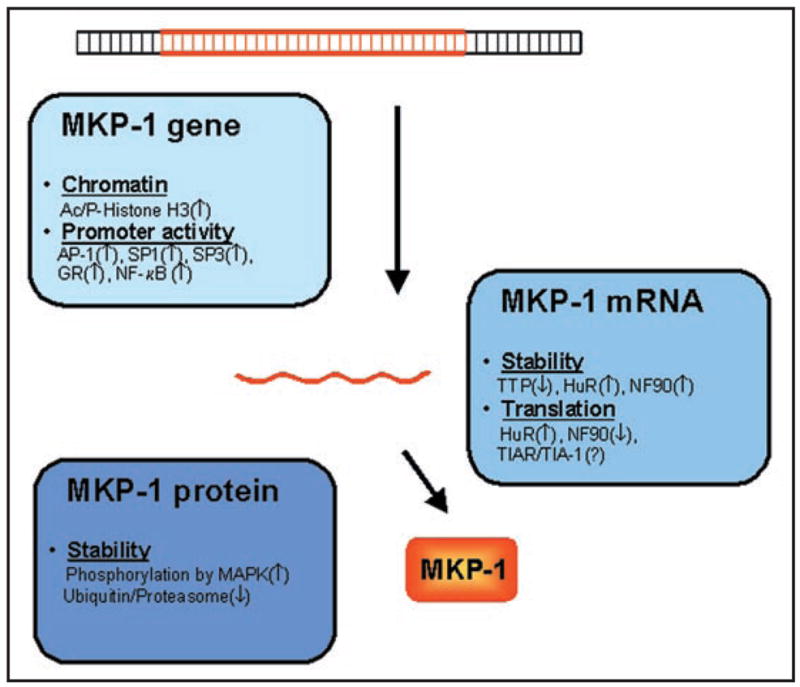

In addition to being regulated by HuR, MKP-1 expression is controlled at multiple steps, broadly divided into three levels: transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Multiple Levels of MKP-1 Regulation. In response to stress, MKP-1 gene expression increases through the action of numerous regulatory factors acting on the MKP-1 DNA, mRNA and protein. Transcription increases through local chromatin modification, accompanied by increased association of transcription factors to the MKP-1 promoter (light blue box). Post-transcriptionally, the stability and translation rate of the MKP-1 mRNA are regulated by various RNA-binding proteins (medium blue box). After translation, the MKP-1 protein half-life is further regulated through phosphorylation that affects its ubiquitinylation and hence its proteolysis (dark blue box).

MKP-1 transcription

The transcriptional component of MKP-1 induction by stress and mitogens has been have studied extensively. In response to various stimuli, transcription factors such as AP-1 (c-Fos, c-Jun, ATF2), SP1, SP3, glucocorticoid receptor and NF-κB were shown to associate with the MKP-1 promoter and induced MKP-1 transcription.30–34 In addition, phosphorylation and acetylation of histone H3 altered the chromatin at the MKP-1 gene locus, increasing the association of RNA polymerase II to the MKP-1 gene promoter and its transcription.35

MKP-1 mRNA metabolism

Following transcription, several RBPs besides HuR have been found to bind the MKP-1 mRNA and modulate its post-transcriptional fate. Two RBPs associating with the MKP-1 mRNA were shown to affect its stability: tristetraprolin (TTP), which promoted MKP-1 mRNA degradation,36 and NF90, which increased its stability.12 The translation of MKP-1 mRNA was promoted by HuR and repressed by NF90.12 Although other translation-repressing RBPs were also found to bind to the MKP-1 mRNA, including TIAR [T-cell intracellular antigen-1 (TIA-1)-related] and TIA-1,12 their influence on MKP-1 expression remains to be studied.

MKP-1 protein stability

Additionally, MKP-1 protein levels can fluctuate through changes in protein stability. MKP-1 is stabilized after phosphorylation by MAPKs and degraded by ubiquitinylation.37–39

Perspective: MKP-1 Regulation and the Stress Response

The multi-leveled, seemingly redundant regulation of MKP-1 underscores the importance of expressing this key phosphatase in response to the appropriate stimuli, at the correct time, and in right abundance. We propose that HuR’s ability to induce MKP-1 expression by associating with the MKP-1 mRNA is advantageous for the cell: it allows the timely production of MKP-1 in response to stress 12 that can damage DNA (causing potentially agents such as H2O2, inactivating mutations) or can temporarily repress transcription. In this manner, the cell ensures that an essential regulator of MAPKs is in place to shut off MAPK signaling as needed, thus avoiding the harmful consequences of unscheduled proliferation or apoptosis. This paradigm highlights the increasingly recognized role for HuR in the maintenance of homeostasis following cellular injury.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations

- Bcl-2

B-cell lymphoma 2

- Chk2

checkpoint kinase 2

- COX-2

cyclooxygenase-2

- ELAV-like 1

embryonic lethal, abnormal vision, drosophila-like

- ERK

extracellular regulated kinase

- HIF

hypoxia-inducible factor

- JNK

c-Jun N-terminal Kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- Mcl-1

myeloid cell leukemia sequence 1

- NPM

nucleophosmin

- ProTα

prothymosin-α

- SIRT1

mammalian SIR2 (silent information regulator 2) protein ortholog

- UVC

short-wavelength ultraviolet light

- VEGF

vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Keene JD. Why is Hu where? Shuttling of early-response-gene messenger RNA subsets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:5–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.1.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang W, Furneaux H, Cheng H, Caldwell MC, Hutter D, Liu Y, Holbrook N, Gorospe M. HuR regulates p21 mRNA stabilization by UV light. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:760–9. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.760-769.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hinman MN, Lou H. Diverse molecular functions of Hu proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8252-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brennan CM, Steitz JA. HuR and mRNA stability. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:266–77. doi: 10.1007/PL00000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Peng SS, Chen CY, Xu N, Shyu AB. RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:3461–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fan XC, Steitz JA. Overexpression of HuR, a nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling protein, increases the in vivo stability of ARE-containing mRNAs. EMBO J. 1998;17:3448–60. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazan-Mamczarz K, Galban S, Lopez de Silanes I, Martindale JL, Atasoy U, Keene JD, Gorospe M. RNA-binding protein HuR enhances p53 translation in response to ultraviolet light irradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8354–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1432104100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lal A, Kawai T, Yang X, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Gorospe M. Antiapoptotic function of RNA-binding protein HuR effected through prothymosin alpha. EMBO J. 2005;24:1852–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gorospe M. HuR in the mammalian genotoxic response: post-transcriptional multitasking. Cell Cycle. 2003;2:412–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abdelmohsen K, Pullmann R, Jr, Lal A, Kim HH, Galban S, Yang X, Blethrow JD, Walker M, Shubert J, Gillespie DA, Furneaux H, Gorospe M. Phosphorylation of HuR by Chk2 regulates SIRT1 expression. Mol Cell. 2007;25:543–57. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abdelmohsen K, Lal A, Kim HH, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional orchestration of an anti-apoptotic program by HuR. Cell Cycle. 2007;6:1288–92. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.11.4299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuwano Y, Kim HH, Abdelmohsen K, Pullmann R, Jr, Martindale JL, Yang X, Gorospe M. MKP-1 mRNA Stabilization and Translational Control by RNA-Binding Proteins HuR and NF90. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4562–75. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00165-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abdelmohsen K, Kuwano Y, Kim HH, Gorospe M. Posttranscriptional gene regulation by RNA-binding proteins during oxidative stress: implications for cellular senescence. Biol Chem. 2008;389:243–55. doi: 10.1515/BC.2008.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawai T, Lal A, Yang X, Galban S, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Gorospe M. Translational control of cytochrome c by RNA-binding proteins TIA-1 and HuR. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:3295–307. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.8.3295-3307.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhattacharyya SN, Habermacher R, Martine U, Closs EI, Filipowicz W. Relief of microRNA-mediated translational repression in human cells subjected to stress. Cell. 2006;125:1111–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Galbán S, Kuwano Y, Pullmann R, Jr, Martindale JL, Kim HH, Lal A, Abdelmohsen K, Yang X, Dang Y, Liu JO, Lewis SM, Holcik M, Gorospe M. RNA-binding proteins HuR and PTB promote the translation of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:93–107. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00973-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dixon DA, Tolley ND, King PH, Nabors LB, McIntyre TM, Zimmerman GA, Prescott SM. Altered expression of the mRNA stability factor HuR promotes cyclooxygenase-2 expression in colon cancer cells. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1657–65. doi: 10.1172/JCI12973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kullmann M, Gopfert U, Siewe B, Hengst L. ELAV/Hu proteins inhibit p27 translation via an IRES element in the p27 5’UTR. Genes Dev. 2002;16:3087–99. doi: 10.1101/gad.248902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng Z, King PH, Nabors LB, Jackson NL, Chen CY, Emanuel PD, Blume SW. The ELAV RNA-stability factor HuR binds the 5’-untranslated region of the human IGF-IR transcript and differentially represses cap-dependent and IRES-mediated translation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2962–79. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leandersson K, Riesbeck K, Andersson T. Wnt-5a mRNA translation is suppressed by the Elav-like protein HuR in human breast epithelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:398–9. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang W, Caldwell MC, Lin S, Furneaux H, Gorospe M. HuR regulates cyclin A and cyclin B1 mRNA stability during cell proliferation. EMBO J. 2000;19:2340–50. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.10.2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lal A, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Kawai T, Yang X, Martindale JL, Gorospe M. Concurrent versus individual binding of HuR and AUF1 to common labile target mRNAs. EMBO J. 2004;23:3092–102. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng SS, Chen CY, Xu N, Shyu AB. RNA stabilization by the AU-rich element binding protein, HuR, an ELAV protein. EMBO J. 1998;17:3461–70. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.12.3461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lafon I, Carballès F, Brewer G, Poiret M, Morello D. Developmental expression of AUF1 and HuR, two c-myc mRNA binding proteins. Oncogene. 1998;16:3413–21. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xiao L, Rao JN, Zou T, Liu L, Marasa BS, Chen J, Turner DJ, Zhou H, Gorospe M, Wang JY. Polyamines regulate the stability of activating transcription factor-2 mRNA through RNA-binding protein HuR in intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4579–90. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-07-0675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zou T, Mazan-Mamczarz K, Rao JN, Liu L, Marasa BS, Zhang AH, Xiao L, Pullmann R, Gorospe M, Wang JY. Polyamine depletion increases cytoplasmic levels of RNA-binding protein HuR leading to stabilization of nucleophosmin and p53 mRNAs. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:19387–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602344200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levy NS, Chung S, Furneaux H, Levy AP. Hypoxic stabilization of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by the RNA-binding protein HuR. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:6417–23. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.11.6417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lopez de Silanes I, Lal A, Gorospe M. HuR: post-transcriptional paths to malignancy. RNA Biol. 2005;2:11–3. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.1.1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lopez de Silanes I, Zhan M, Lal A, Yang X, Gorospe M. Identification of a target RNA motif for RNA-binding protein HuR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:2987–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0306453101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ryser S, Massiha A, Piuz I, Schlegel W. Stimulated initiation of mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) gene transcription involves the synergistic action of multiple cis-acting elements in the proximal promoter. Biochem J. 2004;378:473–84. doi: 10.1042/BJ20031022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kwak SP, Hakes DJ, Martell KJ, Dixon JE. Isolation and characterization of a human dual specificity protein-tyrosine phosphatase gene. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:3596–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laderoute KR, Mendonca HL, Calaoagan JM, Knapp AM, Giaccia AJ, Stork PJ. Mitogen-activated protein kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1) expression is induced by low oxygen conditions found in solid tumor microenvironments. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:12890–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.18.12890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu Q, Konta T, Nakayama K, Furusu A, Moreno-Manzano V, Lucio-Cazana J, Ishikawa Y, Fine LG, Yao J, Kitamura M. Cellular defense against H2O2-induced apoptosis via MAP kinase-MKP-1 pathway. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:985–93. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Issa R, Xie S, Khorasani N, Sukkar M, Adcock IM, Lee KY, Chung KF. Corticosteroid inhibition of growth-related oncogene protein-alpha via mitogen-activated kinase phosphatase-1 in airway smooth muscle cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:7366–75. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li J, Gorospe M, Hutter D, Barnes J, Keyse SM, Liu Y. Transcriptional induction of MKP-1 in response to stress is associated with histone H3 phosphorylation-acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8213–24. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8213-8224.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin NY, Lin CT, Chang CJ. Modulation of immediate early gene expression by tristetraprolin in the differentiation of 3T3-L1 cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:69–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brondello JM, Pouyssegur J, McKenzie FR. Reduced MAP kinase phosphatase-1 degradation after p42/p44MAPK-dependent phosphorylation. Science. 1999;286:2514–7. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5449.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kassel O, Sancono A, Krätzschmar J, Kreft B, Stassen M, Cato AC. Glucocorticoids inhibit MAP kinase via increased expression and decreased degradation of MKP-1. EMBO J. 2001;20:7108–16. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Choi BH, Hur EM, Lee JH, Jun DJ, Kim KT. Protein kinase Cdelta-mediated proteasomal degradation of MAP kinase phosphatase-1 contributes to glutamate-induced neuronal cell death. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1329–40. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]