Abstract

The effect of state legislation and federal policies supporting living donors on living kidney donation rates in the United States is unknown. We studied living kidney donation rates from 1988 to 2006, and we assessed changes in donation before and after the enactment of state legislation and the launch of federal initiatives supporting donors. During the study, 27 states enacted legislation. Among states enacting legislation, there was no statistically significant difference in the average rate of increase in overall living kidney donations after compared to before state legislation enactment (annual increase in donations per 1 000 000 population [95% confidence interval] 2.39 [1.94–2.84] compared to 1.68 [0.89–2.47] respectively, p > 0.05). Among states not enacting legislation, there was a statistically significantly greater annual increase in overall donation rates from 1997 to 2002 compared to before 1997 when federal initiatives commenced, but there was no growth in annual rates after 2002. State and federal legislation were associated with increases in living-unrelated donation. These findings suggest that although existing public policies were not associated with improvements in the majority of donations from living-related donors, they may have had a selective effect on barriers to living-unrelated kidney donation.

Keywords: End-stage renal disease, legislation, living kidney donation, willingness to donate

Introduction

The need for kidney transplantation in the United States has risen rapidly over the past decade, outpacing slow growth in numbers of available donors. Although efforts to recover greater numbers of deceased donor organs through the Organ Donation Collaboration Initiative (1,2) (in which known best practices for improving deceased donor organs have been spread among the largest hospitals in the United States) have had moderate success, living donors have consistently comprised a very large proportion (40–50%) of donated organs in recent years (3). However, living-related and unrelated kidney transplantation, which yield comparable-to-superior clinical outcomes compared to deceased kidney transplantation (3,4), remain underutilized.

The great need for donated organs has prompted a variety of broad-scale efforts to enhance donation rates (5), including the implementation of limited compensation for living organ donors. In addition to the National Organ Donor Leave Act of 1999 (6), which provides additional paid leave for federal employees who are living organ donors, several states have implemented legislation to support living donors. In 1998, Colorado became the first state to enact legislation mandating the use of paid leave for living organ donors for up to 2 days for government employees (7). Since that time, legislation has sprouted in other states offering varying types of support for living donors, including paid or unpaid leave for extended time periods as well as tax benefits (8–42).

Potential living organ donors in the general public are concerned about both medical (such as the potential for complications) and financial (such as the length of uncompensated time spent away from work) aspects of donation (43,44). In addition, potential transplant recipients who are concerned about the financial implications of donation are hesitant to approach potential donors (45,46). The intent of currently enacted legislation and federal initiatives is to overcome such disincentives to living donation by providing government and/or employer support for donors’ physical recovery and by minimizing financial losses as a result of donation. However, it is unclear if well-meaning public policy has had an effect on living kidney donation rates. Therefore, we performed a national study to assess differences in living organ donation rates among persons residing in states with and without legislation to support living organ donors.

Methods

Study design and population

Our study design was a series of cross-sectional analyses of living kidney donation rates from 1988 to 2006 in the continental U.S. We used publicly available data from state legislatures, the United Network for Organ Sharing, the U.S. Census Bureau, the Area Resource File, and the U.S. Renal Data System (USRDS). We estimated annual rates of living kidney donation for each state, and we assessed differences in overall, related and unrelated rates of donation between states that enacted legislation and states that did not enact legislation. We also examined the background association of (i.e. secular trends) federal initiatives begun in 1997 pertaining to living organ donation with donation rates.

Data collection

For our independent variable, we identified states that enacted legislation for living organ donors by searching information published by the United Network for Organ Sharing, the National Conference of State Legislatures, and LexisNexis using keywords ‘organ donation’, ‘organ donor’, and ‘bone marrow donor’ (47–49). We included only legislation that was active from May 18, 1998, the earliest date of relevant legislation, until December 31, 2005 (7,8–42). We did not include legislation enacted in 2006 because we sought to have at least 1 year follow-up for states enacting legislation in 2005. We categorized legislation authorizing employers to provide donors with paid leave from work as ‘paid leave’, legislation offering donors tax deductions or credits for donation as ‘tax benefit’, and legislation providing donors with unpaid leave from work as ‘unpaid leave’. We categorized other forms of legislation (e.g. recommendations or encouragement of paid leave) as ‘other’.

For our dependent variable, we obtained the total number of living kidney donations from donors residing in each continental U.S. state during 1988–2006 from the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN) (administered by the United Network for Organ Sharing under contract with the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration), which performs administrative functions related to organ allocation including collecting and managing scientific data about organ donation and transplantation (50). Data on all U.S. organ donations and transplants are collected directly from hospitals, histocompatibility (tissue typing) laboratories and organ procurement organizations (51). We used population statistics for adults age 18–75 in each continental U.S. state from 1988 to 2006 from the U.S. Census Bureau (52,53).

A variety of factors, including patient demand for living donation, availability of deceased donor kidneys and provider supply could potentially confound any observed relation between legislation and donation rates in each state. For example, states with more physicians able to perform transplant surgery could have greater living transplant rates. We, therefore, ascertained whether rates of physicians and surgeons, the rate of deceased kidney donation or the demand for donation were different among states with versus without donation. We obtained data on the prevalence of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) during 1988–2005 for each state from the USRDS Annual Data Report (54). Because ESRD incidence and prevalence data were not available for 2006, we extrapolated data based on rates of increase in incidence and prevalence of ESRD prior to 2006. We obtained data from the 2006 Area Resource File (a compilation of publicly available data from over 50 sources, including the American Medical Association, the American Hospital Association and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services on health care professions, facilities and utilization) to obtain information on prevalence of all physicians and specialist surgeons in 1988 and 2005 as well as transplant surgeons in 2005 (data available for 2001–2005 only) for each state (a measure of provider supply) (55). We used data from the U.S. OPTN to ascertain rates of deceased donation in each state during 1998–2006 (56). To assess the need for kidney donation in each state during each year, we calculated the ratio of kidney donations-to-ESRD prevalence in each state for each year. Because many of the types of legislation applied only to state or federal employees, we also ascertained whether the number of potential beneficiaries of enacted legislation varied among the states. We obtained data on the prevalence of state and federal employees in each state from the Compendium of Public Employment: 2002, a compendium of local, state and federal government employees produced by the U.S. Census Bureau (57).

Statistical analysis

We compared characteristics of states enacting versus not enacting legislation in bivariate analyses. To estimate donation rates for each study year, we divided the number of adult living kidney donations in each state by the number of adults age 18–75 in each state for each year during 1988–2006. We assumed the proportion of eligible donors relative to the donation rate would be similar in all states. We report living kidney donation rates as the number of living kidney donations per 1 000 000 persons in each year.

We performed a series of cross-sectional analyses over time by calculating aggregate mean living kidney donation rates for all states from January 1, 1988, to December 31, 2006. For all individual states, we calculated mean donation rates and mean annual change in donation rates during the entire study period. For states enacting legislation during the study period, we calculated mean donation rates and mean annual change in donation rates before and after the year of legislation enactment. We used linear spline functions to estimate the relation between time (in years) of legislation enactment and change in living kidney donation rates in a piecemeal linear function, with straight lines representing the discrete periods for all states (individually and collectively) with legislation. To provide a graphical representation of differences in donation rates in the presence versus absence of state legislation, we projected hypothetical donation rates for the hypothetical scenario in which states would not have enacted legislation, basing projections on the rate of increase in donations before legislation was enacted. To assess the potential for secular trends, particularly the association of federal initiatives with state donation rates, we used linear spline functions assessing the rate of change in donation in states with legislation and in states with and without legislation before or after 1997, when the first relevant federal initiatives commenced. Because overall donation rates plateaued after 2002, we also assessed differences in donation rates after 2002 compared to before 2002 for states with and without legislation. We assessed whether donors not emotionally or biologically related to recipients might be more likely to respond to legislation supporting donors when compared to emotionally or biologically related donors (who might donate regardless of support available at state or federal levels) by performing a separate analysis to assess the potential association of legislation among related (defined as parents, children, siblings, spouses and significant others designated as ‘life partners’ in UNOS data) compared to unrelated (all others) donors. In addition, we assessed whether changes in living kidney donation rates associated with state legislation or temporal changes in living kidney donation rates could be related to deceased kidney donation rates during the study (e.g. increases in deceased donation might be associated with declines in living kidney donation rates) by performing a sensitivity analysis in which models used in main analyses additionally adjusted for the annual deceased kidney donation rate in each state. We performed all descriptive and comparative analyses using STATA Statistical Software (Release 9.0, Stata Corporation, TX).

Results

Description of legislation supporting living organ donation and state characteristics

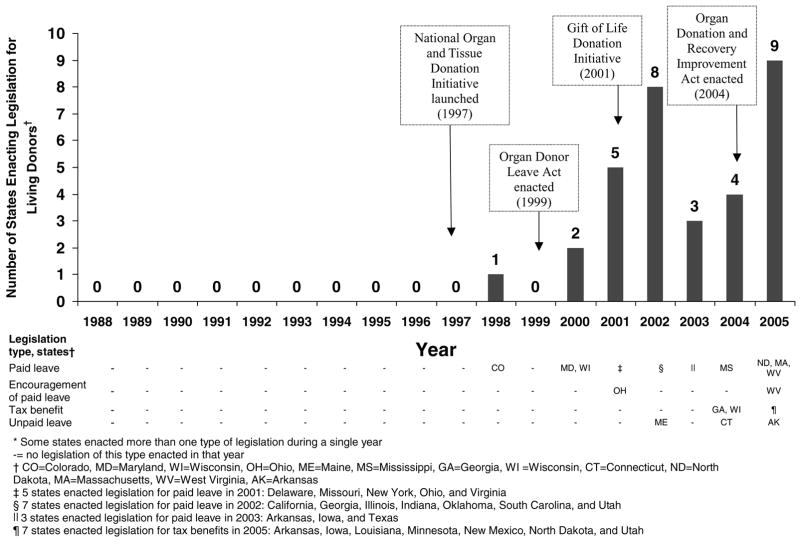

From May 18, 1998 to December 31, 2005, 27 states enacted legislation to provide support for living organ donors. A majority of states (22) enacted legislation mandating paid leave for donors, while fewer enacted legislation mandating tax benefits (9), and unpaid leave (3). Two states enacted legislation encouraging paid leave (Figure 1). Only one state enacted legislation prior to 1999. After 1999, there was a dramatic increase in the number of states enacting legislation, with a majority of legislation enacted after or during the launch of major federal initiatives (including the National Organ and Tissue Donation Initiative (1997) (58), enactment of the Organ Donor Leave Act (1999) (6), Gift of Life Donation Initiative (2001) (59) and enactment of the Organ Donation and Recovery Improvement Act (2004) (60) to enhance organ and tissue donation.

Figure 1.

Number of (continental U.S.) states* enacting legislation providing support for living organ donors and other federal initiatives from 1988–2005.

A detailed description of states’ legislation and federal initiatives is contained in the Appendix. Among the 22 states mandating paid leave, most mandated paid leave for state government employees, while a minority (3) mandated paid leave for both state and local government employees. Most states (19 of 22) mandated paid leave for up to 30 days. Nearly half (12) of these states mandated leave for donation be used as a supplement to donors’ existing paid leave for illnesses. Of the three states mandating unpaid leave, two of three mandated leave be afforded by private employers as well as the state government. The length of mandated unpaid leave was longer than paid leave mandated by states, and ranged from 70 to 168 days. Of the nine states mandating tax benefits for donors, two provided for $10 000 tax credits, while the remainder mandated $10 000 tax deductions (Table 1).

Appendix 1.

State Legislation and Federal Initiatives Supporting Living Organ Donation

| State Legislation

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Type of legislation | Description | Date enacted |

| Arkansas | Paid leave | • Arkansas Code Archive § 21–4–215: ‘In any calendar year, a state employee or public school employee is entitled to the following leave in order to serve as an organ donor or a bone marrow donor: (1) No more than seven (7) days of leave to serve as a bone marrow donor; and (2) No more than thirty (30) days of leave to serve as an organ donor’. | Mar. 20, 2003 |

| Tax deduction | • Arkansas Code Archive § 26–51–2103: ‘In computing net income, a taxpayer may deduct up to ten thousand dollars ($10 000) if, while living, the taxpayer or the taxpayer’s dependent who is claimed under § 26–51–501, donates one (1) or more of his or her human organs to another human for human organ transplantation A deduction that is claimed under subsection (b) of this section may only be claimed in the taxable year in which the human organ transplantation occurs. A taxpayer may claim the deduction under subsection (b) of this section only one (1) time in his or her lifetime. The deduction may be claimed for only the following unreimbursed expenses that are incurred by the taxpayer and are related to the human organ donation of the taxpayer or the taxpayer’s dependent: travel expenses; lodging expenses; lost wages; and medical expenses’. | Mar. 9, 2005 | |

| Unpaid leave | • Arkansas Code Archive § 11–3–205: ‘In addition to any medical, personal, or other paid leave provided by the employer, a private employer shall grant an employee an unpaid leave of absence to allow the employee to serve as an organ donor or a bone marrow donor if the employee requests a leave of absence in writing. The length of the leave of absence shall be equal to the time requested by the employee or ninety (90) days, whichever is less. A private employer may grant a paid or unpaid leave of absence for a length of time greater than ninety (90) days. If the private employer agrees to pay the employee’s regular salary or wages during the leave of absence required under subsection (b) of this section, then the private employer is entitled to a credit against the private employer’s Arkansas withholding tax liability’. | Apr. 13, 2005 | |

| California | Paid leave | • California Gov Code §19991.11: ‘(a) Subject to subdivision (b), an appointing power shall grant to an employee, who has exhausted all available sick leave, the following leaves of absence with pay: (1) A leave of absence not exceeding 30 days to any employee who is an organ donor in any one-year period, for the purpose of donating his or her organ to another person. (2) A leave of absence not exceeding five days to any employee who is a bone marrow donor in any one-year period, for the purpose of donating his or her bone marrow to another person. (b) In order to receive a leave of absence pursuant to subdivision (a), an employee shall provide written verification to the appointing power that he or she is an organ or bone marrow donor and that there is a medical necessity for the donation of the organ or bone marrow. (c) Any period of time during which an employee is required to be absent from his or her position by reason of being an organ or bone marrow donor is not a break in his or her continuous service for the purpose of his or her right to salary adjustments, sick leave, vacation, annual leave, or seniority. (d) If an employee is unable to return to work beyond the time or period that he or she is granted leave pursuant to this section, he or she shall be paid any vacation balance, annual leave balance, or accumulated compensable overtime. The payment shall be computed by projecting the accumulated time on a calendar basis as though the employee was taking time off. If, during the period of projection, the employee is able to return to work, he or she shall be returned to his or her former position as defined in Section 18522.(e) If the provisions of this section are in conflict with the provisions of a memorandum of understanding reached pursuant to Section 3517.5, the memorandum of understanding shall be controlling without further legislative action, except that, if those provisions of a memorandum of understanding require the expenditure of funds, the provisions shall not become effective unless approved by the Legislature in the annual Budget Act’. | Sep. 25, 2002 |

| Colorado | Paid leave | • Colorado Revised Statutes 24–50–104: ‘The procedures of the state personnel director shall provide that no more than two days of paid leave per fiscal year shall be granted for organ, tissue, or bone marrow donation for transplants. Such leave may not be accumulated’. | May 18, 1998 |

| Connecticut | Unpaid leave | • Connecticut General Statutes § 5–248a: ‘Each permanent employee, as defined in subdivision (21) of section 5–196, shall be entitled to the following: A maximum of twenty-four weeks of medical leave of absence within any two-year period upon the serious illness of such employee or in order for such employee to serve as an organ or bone marrow donor. Any such leave of absence shall be without pay’. | May 10, 2004 |

| Delaware | Paid leave | • 29 Delaware Code § 5122 and 14 Delaware Code § 1318B: ‘In any calendar year, a state employee [or a teacher or a school employee] is entitled to the following leave in order to serve as a bone-marrow donor or organ donor: (1) No more than 7 days of leave to serve as a bone marrow donor; (2) No more than 30 days of leave to serve as an organ donor. A state employee [or a teacher or school employee] may use the leave provided by this section without loss or reduction of pay, leave to which the employee is otherwise entitled, credit for time or service, or performance or efficiency rating’. | Jul. 9, 2001 |

| Georgia | Paid leave | • Official Code of Georgia Annotated § 45–20–31: ‘Each employee of the State of Georgia or of any branch, department, board, bureau, or commission of the State of Georgia who serves as an organ donor for the purpose of transplantation shall receive a leave of absence, with pay, of 30 days and such leave shall not be charged again or deducted from any annual or sick leave and shall be included as service in computing any retirement or pension benefits. Each employee of the State of Georgia or of any branch, department, board, bureau, or commission of the State of Georgia who serves as a bone marrow donor for the purpose of transplantation shall receive a leave of absence, with pay, of seven days and such leave shall not be charged again or deducted from any annual or sick leave and shall be included as service in computing any retirement or pension benefits’. | Apr. 24, 2002 |

| Tax deduction | • Official Code of Georgia Annotated § 48–7–27: ‘Georgia taxable net income of an individual shall be the taxpayer’s federal adjusted gross income, as defined in the United States Internal Revenue Code of 1986, less: An amount equal to the actual amount expended for organ donation expenses not to exceed the amount of $10 000 incurred in accordance with the “National Organ Procurement Act”’. | Apr. 29, 2004 | |

| Illinois | Paid leave | • 5 Illinois Compiled Statutes Annotated 327–20: ‘On request, a participating employee [employees of units of local governments or boards of election commissioners] subject to this Act may be entitled to organ donation leave with pay. An employee may use (i) up to 30 days leave in any 12-month period to serve as a bone marrow donor, (ii) up to 30 days of organ donation leave in any 12-month period to serve as an organ donor’. | Aug. 2, 2002 |

| Indiana | Paid leave | • Burns Indiana Code Annotated § 4–15–16–8: ‘The state agency shall grant the employee a leave of absence of not more than thirty (30) work days, as determined by the attending physician, during which the employee may serve as a human organ donor’. | Mar. 28, 2002 |

| Iowa | Paid leave | • Iowa Code § 70A.39: ‘A leave of absence of up to five workdays for an [state] employee who requests a leave of absence to serve as a bone marrow donor if the employee provides written verification from the employee’s physician or the hospital involved with the bone marrow donation that the employee will serve as a bone marrow donor. A leave of absence of up to thirty workdays for an employee who requests a leave of absence to serve as a vascular organ donor if the employee provides written verification from the employee’s physician or the hospital involved with the vascular organ donation that the employee will serve as a vascular organ donor. An employee who is granted a leave of absence under this section shall receive leave without a loss of seniority, pay, vacation time, personal days, sick leave, insurance and health coverage benefits, or earned overtime accumulation. The employee shall be compensated at the employee’s regular rate of pay for those regular work hours during which the employee is absent from work’. | Apr. 14, 2003 |

| Tax deduction | • Iowa Code § 422.7: ‘If the taxpayer, while living, donates one or more of the taxpayer’s human organs to another human being for immediate human organ transplantation during the tax year, subtract, to the extent not otherwise excluded, the following unreimbursed expenses incurred by the taxpayer and related to the taxpayer’s organ donation: travel expenses, lodging expenses, lost wages. The maximum amount that may be deducted under paragraph “a” is ten thousand dollars. A taxpayer shall only take the deduction under this subsection once’. | May 12, 2005 | |

| Louisiana | Tax deduction | • Louisiana Revised Statutes 47:297: ’(1) There shall be allowed a credit against individual income tax due in a taxable year equal to the following amounts incurred by a taxpayer during his tax year if related to the taxpayer’s travel or absence from work because of a living organ donation by the taxpayer or the taxpayer’s spouse: a) The unreimbursed cost of travel paid by the taxpayer to and from the place where the donation operation occurred. B) Unreimbursed lodging expenses paid by the taxpayer. C) Wages or other compensation lost because of the taxpayer’s absence during the donation procedure and convalescence. (2) The credit provided for by this Section shall not exceed ten thousand dollars per organ donation. It shall be allowed against the income tax for the taxable period in which the credit is earned. If the tax credit exceeds the amount of such taxes due, then any unused credit may be carried forward as a credit against subsequent tax liability for a period not to exceed ten years’. | Jun. 29, 2005 |

| Maine | Unpaid leave | • 26 Maine Revised Statutes § 843: ‘As used in this subchapter, unless the context otherwise indicates, the following terms have the following meanings. “Employee” means any person who may be permitted, required or directed by an employer in consideration of direct or indirect gain or profit to engage in any employment but does not include an independent contractor. ‘Employer’ means: Any persons, sole proprietorship, partnership, corporation, association or other business entity that employs 15 or more employees at one location in this State; The State, including the executive, legislation and judicial branches, and any state department or agency that employs any employees; Any city, town or municipal agency that employs 25 or more employees; and Any agent of an employer, the State or a political subdivisions of the State. ‘Family medical leave’ means leave requested by an employee for: the donation of an organ of that employee for a human organ transplant’. | Apr. 11, 2002 |

| Maryland | Paid leave | • Maryland State Personnel and Pensions Code Annotated § 9–1106: ‘This section applies to all employees, including temporary employees, of all units in the Executive, Judicial, and Legislative branches of State government, including any unit with an independent personnel system. On request, an employee subject to this section may be entitled to organ donation leave with pay. An employee may use: up to 7 days of organ donation leave in any 12-month period to serve as a bone marrow donor; and up to 30 days of organ donation leave in any 12-month period to serve as an organ donor’. | May 11, 2000 |

| Massachusetts | Paid leave | • Annotated Laws of Massachusetts GL ch. 149, § 33E: ‘An employee of the commonwealth or of a county, or of a city or town that accepts this section, may take a leave of absence of not more than 30 days in a calendar year to serve as an organ donor, without loss of or reduction in pay, without loss of leave to which he is otherwise entitled and without loss of credit for time or service’. | Sep. 29, 2005 |

| Minnesota | Tax deduction | • Minnesota Statutes § 290.01: ‘For individuals, estates, and trusts, there shall be subtracted from federal taxable income: an amount, not to exceed $10 000 equal to a qualified expenses related to a qualified donor’s donation, while living, of one or more of the qualified donor’s organs to another person for human organ transplantation. An individual may claim the subtraction in this clause for each instance of organ donation for transplantation during the taxable year in which the qualified expenses occur’. | Jul. 14, 2005 |

| Mississippi | Paid leave | • Mississippi Code Annotated § 25–3–103: ‘As used in this section: ‘Participating employee’ means a permanent full-time or part-time employee who has been employed by an agency for a period of six (6) months or more and who donates an organ, bone marrow, blood, or blood platelets. An employee may use (i) up to thirty (30) days of organ donation leave in any twelve-month period to serve as a bone marrow donor, (ii) up to thirty (30) days of organ donation leave in any twelve-month period to serve as an organ donor. An employee shall not be required to use accumulated sick or vacation leave time before being eligible for donor leave’. | Jul. 1, 2004 |

| Missouri | Paid leave | § 105.266 Revised Statues Missouri: ‘Any employee of the state of Missouri, its departments or agencies shall be granted a leave of absence for the time specified for the following purposes: (1) Five workdays to serve as a bone marrow donor if the employee provides his or her employer with written verification that he or she is to serve as a bone marrow donor; (2) Thirty workdays to serve as a human organ donor if the employee provides his or her employer with written verification that he or she is to serve as a human organ donor. An employee who is granted a leave of absence pursuant to this section shall receive his or her bas state pay without interruption during the leave of absence. For purposes of determining seniority, pay or pay advancement and performance awards and for the receipt of any benefit that may be affected by a leave of absence, the service of the employee shall be considered uninterrupted by the leave of absence. The employer shall not penalize an employee for requesting or obtaining a leave of absence according to this section’. | Jul. 6, 2001 |

| New Mexico | Tax deduction | • New Mexico Statutes Annotated § 7–2-36: ‘A taxpayer may claim a deduction from net income in an amount not to exceed ten thousand dollars ($10 000) of organ donation-related expenses, including lost wages, lodging expenses and travel expenses, incurred during the taxable year by the taxpayer or the taxpayer’s dependent as a result of the taxpayer’s or dependent’s donation of a human organ to another person for transfer of that human organ to the body of another person’. | Apr. 5, 2005 |

| New York | Paid leave | • New York Consolidated Law Service Labor § 202-b: ‘Any employee of the state of New York shall be allowed up to seven days paid leave to undergo a medical procedure to donate bone marrow and up to thirty days paid leave to serve as an organ donor, provided, however, that an employee of the state of New York shall provide his or her employer with not less than fourteen days prior written notice of an intention to utilize such leave, unless there exists a medical emergency, attested to by a physician, which would require the employee to participate in the medical procedure or organ donation for which the leave is sought within the fourteen day notification period. Such leave shall be in addition to any other sick or annual leave allowed. An employer shall not retaliate against an employee for requesting or obtaining a leave of absence as provided by this section for the purpose of undergoing a medical procedure to donate bone marrow or serve as an organ donor. The provisions of this section shall not affect an employee’s rights with respect to any other employee benefit otherwise provided by law’. | Aug. 29, 2001 |

| North Dakota | Tax deduction | • North Dakota Century Code § 57–38-01.2: ‘The taxable income of an individual, estate, or trust as computer pursuant to the provisions of the United States Internal Revenue Code of 1954, as amended shall be: Reduced by up to ten thousand dollars of qualified expenses that are related to a donation by a taxpayer or a taxpayer’s dependent, while living, of one or more human organs to another human being for human organ transplantation. A taxpayer may claim the reduction in this subdivision only once for each instance of organ donation during the taxable year in which the human organ donation and the human organ transplantation occurs but if qualified expenses are incurred in more than one taxable year, the reduction for those expenses must me claimed in the year in which the expenses are incurred’. | Mar. 14, 2005 |

| Paid leave | • North Dakota Century Code § 54–06-14.4: ‘The executive officer in charge of a state agency may grant a leave of absence, not to exceed twenty workdays, to an employee for the purpose of donating an organ or bone marrow. If an employee requests donation of sick leave or annual leave, but does not receive the full amount needed for the donation of an organ or bone marrow, the executive officer of the state agency may grant a paid leave of absence for the remainder of the leave up to the maximum total of twenty workdays. Any paid leave of absence granted under this section may not result in a loss of compensation, seniority, annual leave, sick leave, or accrued overtime for which the employee is otherwise eligible’. | Apr. 20, 2005 | |

| Ohio | Paid leave | • Ohio Revised Code Annotated 124.139: ‘A full-time state employee shall receive up to two hundred forty hours of leave with pay during each calendar year to use during those hours when the employee is absent from work because of the employee’s donation of any portion of an adult liver or because of the employee’s donation of an adult kidney. A full-time state employee shall receive up to fifty-six hours of leave with pay during each calendar year to use during those hours when the employee is absent from work because of the employee’s donation of any portion of an adult liver or because of the employee’s donation of adult bone marrow’. | Jul. 10, 2001 |

| Encouragement of paid leave | • Ohio Revised Code Annotated 124.139: ‘The General Assembly hereby encourages political subdivisions and private employers in this state to grant to their full-time employees paid leave similar to the paid leave granted to full-time state employees under section 124.139 of the Revised Code, as enacted by this act’. | Jul. 10, 2001 | |

| Oklahoma | Paid leave | • 74 Oklahoma Statutes § 840–2.20B: ‘Any employee of this state, its departments or agencies shall be granted a leave of absence, subject to approval of the scheduling of such leave by the employee’s Appointing Authority, with medical necessity being the primary determinant for such approval, for the time specified for the following purposes: 1) Five (5) workdays to serve as a bone marrow donor if the employee provides the employer written verification that the employee is to serve as a bone marrow donor; and 2) Thirty (30) workdays to serve as a human organ donor if the employee provides the employer written verification that the employee is to serve as a human organ donor. An employee who is granted a leave of absence pursuant to the provisions of this section shall receive the base state pay without interruption during the leave of absence. For purposes of determining seniority, pay or pay advancements, and performance awards, and for the receipt of any benefit that may be affected by a leave of absence, the service of the employee shall be considered uninterrupted by the leave of absence’. | May 8, 2002 |

| South Carolina | Paid leave | • South Carolina Code of Laws Annotated § 8–11–65: ‘All officers and employees of this State or a political subdivision of this State who wish to be an organ donor and who accrue annual or sick leave as part of their employment are entitled to leaves of absence for their respective duties without loss of pay, time, leave, or efficiency rating for one or more periods not exceeding an aggregate of thirty regularly scheduled workdays in any one fiscal year during which they may engage in the donation of their organs’. | Aug. 6, 2002 |

| Texas | Paid leave | • Texas Government Code § 661.916: ‘A state employee is entitled to a leave of absence without a deduction in salary for the time necessary to permit the employee to serve as a bone marrow or organ donor. The leave of absence provided by this section may not exceed: 1) five working days in a fiscal year to serve as a bone marrow donor; 2) 30 working days in a fiscal year to serve as an organ donor’. | May 29, 2003 |

| Utah | Paid leave | • Utah Code Annotated § 67–19-14.5: ‘An employee who serves as a bone marrow donor shall be granted a paid leave of absence of up to seven days that are necessary for the donation and recovery from the donation. An employee who serves as a donor of a human organ shall be granted a paid leave of absence of up to 30 days that are necessary for the donation and recovery from the donation’. | Apr. 8, 2002 |

| Tax deduction | • Utah Code Annotated § 59–10–134.2: ‘For taxable years beginning on or after January 1, 2005, a taxpayer may claim a nonrefundable tax credit: A) As provided in this section; B) Against taxes otherwise due under this chapter; c) For live organ donation expenses incurred during the taxable year for which the live organ donation occurs; and D) In an amount equal to the lesser of : 1) The actual amount of the live organ donation expenses; or 2) $10 000’. | Mar. 21, 2005 | |

| Virginia | Paid leave | • Virginia Code Annotated § 2.2–2821.1: ‘State employees shall be allowed up to thirty days of paid leave in any calendar year, in addition to other paid leave, to serve as bone marrow or organ donors. The Department shall develop personnel policies providing for the use of such leave. For the purposes of this section, “state employee” means any person who is regularly employed full time on a salaried basis, whose tenure is not restricted as to temporary or provisional appointment, in the service of, and whose compensation is payable, no more often than biweekly, in whole or in part, by the commonwealth or any department, institution, or agency thereof’. | Mar. 26, 2001 |

| West Virginia | Paid leave | • West Virginia Code § 29–6–28: ‘A full-time state employee shall receive up to one hundred twenty hours of leave with pay during each calendar year to use during those hours when the employee is absent from work because of the employee’s donation of any portion of an adult liver or because of the employee’s donation of an adult kidney. A full-time state employee shall receive up to fifty-six hours of leave with pay during each calendar year to use during those hours when the employee is absent from work because of the employee’s donation of adult bone marrow. An appointing authority shall compensate a full-time state employee who uses leave granted under this section at the employee’s regular rate of pay for those regular work hours during which the employee is absent from work. The Director of Personnel shall provide information about this section to full-time employees. | May 11, 2005 |

| Encouragement of paid leave | • West Virginia Code § 29–6–28:The Legislation hereby encourages political subdivisions and private employers in this state to grant their full-time employees paid leave similar to the paid leave granted to full-time state employees under this section’. | May 11, 2005 | |

| Wisconsin | Paid leave | • Wisconsin Statutes § 230.35: ‘An appointing authority shall grant a leave of absence of 5 workdays to any employee who requests a leave of absence to serve as a bone marrow donor if the employee provides the appointing authority written verification that he or she is to serve as a bone marrow donor. An appointing authority shall grant a leave of absence of 30 workdays to any employee who requests a leave of absence to serve as a human organ donor if the employee provides the appointing authority written verification that he or she is to serve as a human organ donor. An employee who is granted a leave of absence under this subsection shall receive his or her base state pay without interruption during the leave of absence. For purposes of determining seniority, pay or pay advancement and performance awards and for the receipt of any benefit that may be affected by a leave of absence, their service of the employee shall be considered uninterrupted by the leave of absence’. | May 9, 2000 |

| Tax deduction | • Wisconsin Statutes § 71.05: ‘Subject to the conditions in this paragraph, an individual may subtract up to $10 000 from federal adjusted gross income if he or she, or his or her dependent who is claimed under section 151 (c) of the Internal Revenue Code, while living, donates one or more of his or her human organs to another human being for human organ transplantation, as define in s.146.345 (1), except that in this paragraph, “human organ” means all or part of a liver, pancreas, kidney, intestine, lung, or bone marrow. A subtract modification that is claimed under this paragraph may be claimed in the taxable year in which the human organ transplantation occurs. An individual may claim the subtract modification under subd. 1. only once, and the subtract modification may be claimed for only the following unreimbursed expenses that are incurred by the claimant and related to the claimants organ donation: travel expenses, lodging expenses, lost wages’. | Jan. 30, 2004 | |

| Federal Initiatives | |||

| National Organ and Tissue Donation Initiative | • Initiative launched by Secretary of Health and Human Services to: (1) Create a broad national partnership of public, private and volunteer organizations to encourage Americans to agree to organ and tissue donation. The partnership will emphasize the need to share personal decisions on organ donation with one’s family. (2) Work with health care providers, consumers and physicians to ensure that deaths are reported to organ procurement organizations (OPOs) whenever there is potential for donation. (3) Learn more about what works to bring about donation, through research and evaluation, including an HHS conference on best practices. | 1997 | |

| Organ Donor Leave Act | • ‘To amend title 5, United States Code, to increase the amount of leave time available to a Federal employee in any year in connection with serving as an organ donor, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, [*1] SECTION 1. INCREASED LEAVE TIME TO SERVE AS AN ORGAN DONOR. (a) Short Title. <5 USC 9601 note> –This Act may be cited as the “Organ Donor Leave Act”. (b) In General.–Subsection (b) of the first section 6327 of title 5, United States Code (relating to absence in connection with serving as a bone-marrow or organ donor) is amended to read as follows:

(b) An employee may, in any calendar year, use– (1) not to exceed 7 days of leave under this section to serve as a bone-marrow donor; and (2) not to exceed 30 days of leave under this section to serve as an organ donor’. |

Sept. 24, 1999 | |

| Gift of Life Donation Initiative | • A five-part national program launched by the Secretary of Health and Human Services to increase awareness and promote donation of organs, marrow and tissue for transplantation, as well as blood donation. Under this initiative, Secretary s mobilized the resources and expertise of the federal government, the private sector, and local communities in the Workplace Partnership for Life. | 2001 | |

| Organ Donation and Recovery Improvement Act | • [selected excerpts pertaining to living organ donation] REIMBURSEMENT OF TRAVEL AND SUBSISTENCE EXPENSES INCURRED TOWARD LIVING ORGAN DONATION. Sec. 377. REIMBURSEMENT OF TRAVEL AND SUBSISTENCE EXPENSES INCURRED TOWARD LIVING ORGAN DONATION. | Apr. 5, 2004 | |

| (a) In General.–The Secretary may award grants to States, transplant centers, qualified organ procurement organizations under section 371, or other public or private entities for the purpose of–(1) providing for the reimbursement of travel and subsistence expenses incurred by individuals toward making living donations of their organs (in this section referred to as ‘donating individuals’); and (2) providing for the reimbursement of such incidental nonmedical expenses that are so incurred as the Secretary determines by regulation to be appropriate. [**585] (b) Preference.–The Secretary shall, in carrying out subsection (a), give preference to those individuals that the Secretary determines are more likely to be otherwise unable to meet such expenses’.(c) Certain Circumstances.–The Secretary may, in carrying out subsection (a), consider–(1) the term ‘donating individuals’ as including individuals who in good faith incur qualifying expenses toward the intended donation of an organ but with respect to whom, for such reasons as the Secretary determines to be appropriate, no donation of the organ occurs; and (2) the term ‘qualifying expenses’ as including the expenses of having relatives or other individuals, not to exceed 2, accompany or assist the donating individual for purposes of subsection (a) (subject to making payment for only those types of expenses that are paid for a donating individual). (d) Relationship to Payments Under Other Programs.–An award may be made under subsection (a) only if the applicant involved agrees that the award will not be expended to pay the qualifying expenses of a donating individual to the extent that payment has been made, or can reasonably be expected to be made, with respect to such expenses–(1) under any State compensation program, under an insurance policy, or under any Federal or State health benefits program;(2) by an entity that provides health services on a prepaid basis; or (3) by the recipient of the organ. (e) Definitions.–For purposes of this section: (1) The term ‘donating individuals’ has the meaning indicated for such term in subsection (a)(1), subject to subsection (c)(1). (2) The term ‘qualifying expenses’ means the expenses authorized for purposes of subsection (a), subject to subsection (c)(2) (f) Authorization of Appropriations.–For the purpose of carrying out this section, there is authorized to be appropriated $ 5 000 000 for each of the fiscal years 2005 through 2009’. [*4] SEC. 4. PUBLIC AWARENESS; STUDIES AND DEMONSTRATIONS. Part H of title III of the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 273 et seq.) is amended by inserting after section 377 the following: Sec. 377A. <42 USC 274f-1> PUBLIC AWARENESS; STUDIES AND DEMONSTRATIONS. (a) Organ Donation Public Awareness Program.–The Secretary shall, directly or through grants or contracts, establish a public education program in cooperation with existing national public awareness campaigns to increase awareness about organ donation and the need to provide for an adequate rate of such donations. | |||

Table 1.

Features of legislation enacted in 48 continental U.S. states from 1988 to 2005

| Paid leave

|

Unpaid leave

|

Tax benefit

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | Year | Type of employee | Amount (days) | Use sick pay first? | Year | Type of employee | Amount (days) | Year | Type | Amount |

| Arkansas | 2003 | State and local government | 30 | NS** | 2005 | Private | 90 | 2005 | Deduction | $10 000 |

| California | 2002 | State government | 30 | Yes | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Colorado | 1998 | State government | 2 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Connecticut | ~* | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2004 | State | 168† | ~ | ~ | |

| Delaware | 2001 | State and local government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Georgia | 2002 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2004 | Deduction | $10 000 |

| Illinois | 2002 | State and local government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Indiana | 2002 | State government | 30 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Iowa | 2003 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2005 | Deduction | $10 000 |

| Louisiana | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2005 | Credit | $10 000 |

| Maine | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2002 | Private and State | 70‡ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Maryland | 2000 | State government | 30 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Massachusetts | 2005 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Minnesota | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2005 | Deduction | $10 000 |

| Mississippi | 2004 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | |||

| Missouri | 2001 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | |||

| New Mexico | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2005 | Deduction | $10 000 |

| New York | 2001 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| North Dakota | 2005 | State government | 20 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2005 | Deduction | $10 000 |

| Ohio | 2001 | State government | 30 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Oklahoma | 2002 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| South Carolina | 2002 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Texas | 2003 | State government | 30 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Utah | 2002 | State government | 30 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2005 | Credit | $10 000 |

| Virginia | 2001 | State government | 30 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| West Virginia | 2005 | State government | 15 | NS | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ | ~ |

| Wisconsin | 2000 | State government | 30 | No | ~ | ~ | ~ | 2004 | Deduction | $10 000 |

~ = no legislation.

NS = not specified.

Specified as 24 weeks in legislation.

Specified as 10 weeks in legislation.

The median time states’ legislation had been enacted prior to the end of the study period (December 31, 2006) was 2.5 (inter-quartile range: 2–5) years. States enacting legislation had statistically significantly greater increases in prevalence of ESRD from 1988 to 2005 when compared to states not enacting legislation. However, there were no differences in states enacting legislation versus those not enacting legislation according to state population size, incidence or prevalence of ESRD in 1988 or 2005, prevalence of physicians or surgeons with specialty training in 1988 or 2005, number of state or federal employees in 2002, rate of deceased kidney donation in 1988 or 2006 or Census regions (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of states enacting and not enacting state legislation providing support for living organ donation

| Enactment of legislation during study period

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| State characteristic | No enactment (n = 21) | Enactment (n = 27) | p-Value |

| Population size, mean (SD) | |||

| Year 1988 | 2 723 889 (2 606 554) | 4 122 882 (4 400 260) | 0.2 |

| Year 2006 | 3 418 462 (3 206 894) | 4 969 819 (5 445 848) | 0.3 |

| Change from 1990 to 2006 | 694 573 (864 108) | 846938 (1 234 892) | 0.6 |

| ESRD* Incidence (per 1 000 000 population), mean (SD)† | |||

| Year 1988 | 207.6 (49.9) | 233.6 (50.8) | 0.1 |

| Year 2005 | 447.4 (106.6) | 498.9 (115.3) | 0.1 |

| Change from 1988 to 2005 | 239.9 (68.8) | 265.3 (80.4) | 0.3 |

| ESRD prevalence (per 1 000 000 population), mean (SD)† | |||

| Year 1988 | 790.6 (140.6) | 866.2 (143.7) | 0.07 |

| Year 2005 | 2011.8 (414.3) | 2305.4 (448.3) | 0.02 |

| Change from 1988 to 2005 | 1221.2 (299.2) | 1439.2 (314.9) | 0.02 |

| Prevalence of all physicians (per 1 000 000 population), mean (SD) | |||

| All physicians 1988‡ | 2601.1 (443.5) | 2829.2 (683.1) | 0.2 |

| All physicians 2005‡ | 3470.0 (693.6) | 3647.1 (943.3) | 0.5 |

| Change from 1988 to 2005 | 868.9 (310.2) | 817.9 (358.2) | 0.6 |

| Prevalence of specialist surgeons (per 1 000 000 population), mean (SD) | |||

| All specialist surgeons 1988‡ | 537.9 (57.2) | 539.2 (74.8) | 0.9 |

| All specialist surgeons 2005‡ | 627.0 (70.2) | 604.6 (94.1) | 0.4 |

| Change from 1988 to 2005 | 89.1 (55.8) | 65.3 (49.9) | 0.1 |

| Prevalence of transplant surgeons (per 100 000 population), mean (SD) | |||

| All transplant surgeons 2005§ | 0.6 (0.7) | 0.6 (0.5) | 0.9 |

| Prevalence of government employees (per 1 000 000 population), mean (SD) | |||

| State employees 2002 | 24 078 (4 555) | 25 147 (6 752) | 0.5 |

| Federal employees 2002 | 12 992 (3 070) | 13 903 (6 358) | 0.6 |

| Deceased kidney donation rate (per 1 000 000 population), mean (SD) | |||

| Year 1988 | 42.3 (16.7) | 44.6 (44.7) | 0.6 |

| Year 2006 | 53.6 (3.2) | 54.0 (15.2) | 0.9 |

| Census region, n (%) | |||

| Midwest | 4 (19) | 8 (29) | 0.3 |

| Northeast | 5 (24) | 4 (15) | |

| South | 5 (24) | 11 (41) | |

| West | 7 (33) | 4 (15) | |

ESRD = end-stage renal disease.

Data from United States Renal Data System Annual Report available only through 2005.

Data from Area Resource File on physician workforce available for select years through 2005.

Only surgeons designating themselves as ‘transplant surgeons’ in 2005. This designation was newly instituted in 2000.

Pattern of donation over time and association of legislation with change in donation rates

The mean living kidney donation rate in the continental U.S increased during the study period (11.3 (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 9.9 to 12.8) donations per 1 000 000 population in 1988 to 33.5 (95% CI: 30.1 to 36.9) donations per 1 000 000 population in 2006). The mean proportion of donations from unrelated donors among all states rose dramatically during the study period (ranging from 1.5% of all donations in 1988 to 26% of all donations in 2006). Prior to 2002, the mean (95% CI) annual increase in all living kidney donations was 1.6 (1.5 to 1.8) per 1 000 000 population per year. After 2002, however, annual increases in donation plateaued (mean annual increase in donations 0.6 (−0.5 to 0.6) donations per 1 000 000 population per year. Annual changes in donation varied among the individual 48 states, with all states demonstrating an average annual increase in living kidney donations during the study. Minnesota, Maine and North Dakota experienced the greatest average annual increases in living kidney donations (mean (SD) increases of 2.9 (0.8), 2.8 (2.2) and 2.8 (2.5) donations per 1 000 000 population, respectively), while Oklahoma, Arkansas and South Carolina experienced the smallest average annual increases in living kidney donations (mean (SD) increases of 0.3 (0.6), 0.5 (0.7) and 0.6 (0.7) donations per 1 000 000 population, respectively).

Over the entire study period, the unadjusted mean overall living kidney donation rate for states with enacted legislation was not statistically significantly greater than the mean donation rate for states with no legislation enacted (average difference (95% CI) in donation rate 2.4 (−2.0 to 6.8) donations per 1 000 000 population greater in states with legislation enacted versus states with no legislation enacted, p > 0.05). The rate of change in overall donations during the entire study period was also not statistically significantly greater in states enacting legislation compared to states not enacting legislation (difference in average annual increase (95% CI): 0.06 (−0.44 to 0.33) donations per 1 000 000 greater in states enacting (versus not enacting) legislation, p > 0.05). There was no difference in the need for kidney donation in states with legislation enacted versus states without legislation enacted at baseline (mean (SD) donations per prevalent case of ESRD: 0.015 (0.009) versus 0.014 (0.006), respectively, p > 0.05) or during the entire study period (mean (SD) donations per prevalent case of ESRD: 0.015 (0.001) versus 0.015 (0.001), respectively, p > 0.05).

Among the 27 states enacting legislation during the study period, mean overall donation rates and mean annual changes in overall donation rates before and after enactment of legislation varied. While 25 of the 27 states experienced statistically significant average annual increases in donation rates before legislation was enacted, only three of the states experienced statistically significant average annual increases in donation rates after legislation was enacted. A majority (n = 22) of the states enacting legislation experienced no growth in donation rates after legislation was enacted, and two states experienced statistically significant average annual declines in donation rates after legislation was enacted (Table 3). Among states not enacting legislation, mean donation rates before and after 1997, when federal initiatives to enhance living organ donation commenced, varied. While 11 of the 21 states not enacting their own legislation experienced statistically significant annual increases in donation after 1997, 10 of these states experienced no statistically significant average annual increase in donation rates after 1997 (Table 4).

Table 3.

Mean overall donation rate* and mean annual change in donation rates before and after legislation enacted

| Time period before or after legislation enacted

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before legislation enacted

|

After legislation enacted

|

|||||||||

| Donation rate

|

Donation rate

|

|||||||||

| State† | Years, n | Mean (SD)‡ | Earliest year§ | Last year§ | Change per year** | Years, n | Mean (SD) | Earliest year | Last year | Change per year |

| Indiana | 14 | 15.4 (4.3) | 9.3 | 23.1 | 0.9** | 5 | 28.2 (5.8) | 22.5 | 37.9 | 3.1** |

| Illinois | 14 | 18.9 (6.9) | 11.4 | 31.3 | 1.6** | 5 | 39.9 (3.7) | 36.8 | 45.1 | 2.2** |

| Louisiana | 4 | 10.1 (3.1) | 9.1 | 13.7 | 0.9 | 15 | 19.8 (4.8) | 11.2 | 21.6 | 0.8** |

| North Dakota | 17 | 35.9 (21.3) | 9.2 | 43.3 | 3.4** | 2 | 47.6 (6.2) | 43.2 | 52.0 | 8.8 |

| New Mexico | 17 | 17.6 (9.1) | 12.1 | 29.5 | 1.5** | 2 | 25.7 (2.9) | 23.7 | 27.8 | 4.1 |

| West Virginia | 17 | 16.8 (5.3) | 13.5 | 23.9 | 0.9** | 2 | 34.1 (1.6) | 33.0 | 35.2 | 2.2 |

| South Carolina | 14 | 17.8 (5.1) | 9.7 | 19.7 | 1.0** | 5 | 19.9 (3.8) | 16.7 | 21.9 | 1.8 |

| Wisconsin | 12 | 23.4 (5.6) | 20.3 | 27.6 | 1.2** | 7 | 42.5 (67) | 32.5 | 39.9 | 1.4 |

| Virginia | 13 | 17.6 (8.4) | 8.1 | 34.0 | 2.0** | 6 | 43.5 (3.1) | 40.4 | 44.9 | 1.4 |

| Ohio | 13 | 16.5 (5.7) | 12.4 | 31.8 | 1.2** | 6 | 40.7 (3.2) | 37.2 | 42.3 | 1.0 |

| Missouri | 13 | 17.4 (3.6) | 13.8 | 22.8 | 0.8** | 6 | 24.0 (2.5) | 23.6 | 24.4 | 0.7 |

| Colorado | 10 | 12.1 (4.7) | 8.8 | 20.3 | 1.4** | 9 | 29.1 (4.2) | 25.4 | 31.0 | 0.4 |

| Connecticut | 16 | 20.9 (10.8) | 5.9 | 26.9 | 2.1** | 3 | 24.1 (0.5) | 23.5 | 24.0 | 0.3 |

| New York | 13 | 15.3 (6.4) | 10.1 | 28.6 | 1.6** | 6 | 31.5 (1.4) | 31.6 | 31.9 | 0.3 |

| Mississippi | 16 | 14.8 (5.9) | 6.5 | 22.7 | 1.1** | 3 | 22.8 (0.5) | 22.9 | 23.2 | 0.1 |

| Maine | 14 | 53.3 (17.7) | 31.1 | 76.7 | 3.7** | 5 | 74.8 (17.2) | 60.6 | 67.3 | −0.3 |

| Utah | 14 | 30.9 (5.6) | 27.6 | 42.7 | 1.5** | 5 | 44.8 (6..9) | 41.0 | 47.1 | −0.3 |

| Delaware | 13 | 20.1 (13.9) | 6.5 | 30.8 | 3.2** | 6 | 34.6 (7.5) | 32.0 | 41.8 | −0.4 |

| Minnesota | 17 | 39.3 (15.6) | 13.3 | 61.3 | 3.0** | 2 | 64.7 (0.3) | 64.9 | 64.4 | −0.5 |

| California | 14 | 16.6 (5.9) | 8.0 | 24.3 | 1.4** | 5 | 26.1 (1.6) | 25.5 | 23.9 | −0.6 |

| Georgia | 14 | 16.1 (3.2) | 13.0 | 22.5 | 0.5** | 5 | 24.3 (2.9) | 24.7 | 20.9 | −0.6 |

| Texas | 15 | 15.8 (4.4) | 8.3 | 23.9 | 0.9** | 4 | 22.7 (1.2) | 24.0 | 21.2 | −0.8 |

| Iowa | 15 | 24.0 (11.5) | 8.1 | 39.1 | 2.5** | 4 | 37.9 (3.8) | 38.2 | 36.9 | −1.3 |

| Massachusetts | 17 | 23.7 (8.3) | 11.8 | 38.5 | 1.6** | 2 | 34.8 (1.0) | 35.6 | 34.1 | −1.4 |

| Arkansas | 15 | 20.6 (5.0) | 15.2 | 23.6 | 0.8** | 4 | 24.0 (2.7) | 26.5 | 20.6 | −2.1 |

| Oklahoma | 14 | 13.9 (3.1) | 13.1 | 20.1 | 0.3 | 5 | 18.0 (4.5) | 22.4 | 14.3 | −2.4** |

| Maryland | 12 | 25.5 (15.0) | 9.6 | 56.1 | 4.0** | 7 | 43.8 (6.7) | 56.2 | 39.1 | −2.7** |

Number of living kidney donations per 1 000 000 population.

Includes only states with legislation enacted to reward or incentivize living kidney donation during the study; listed in descending order according to mean change in donation rate after legislation enacted.

SD = standard deviation.

Donation rate during earliest year before (or after) legislation enactment.

Donation rate during last year before (or after) legislation enactment.

= Change is statistically significantly positive or negative in direction.

Table 4.

Mean overall donation rate* and mean annual increase in donations before and after 1997, when relevant federal initiatives to provide support for living donors commenced

| Years before or after 1997

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before 1997

|

After 1997

|

|||||||

| Donation rate

|

Donation rate

|

|||||||

| Year

|

Year

|

|||||||

| State† | Mean (SD)‡ | 1988 | 1996 | Change per year | Mean (SD) | 1997 | 2006 | Change per year |

| South Dakota | 17.0 (4.9) | 11.0 | 16.6 | 0.5 | 41.1(18.7) | 24.9 | 60.4 | 5.5§ |

| Nebraska | 11.9 (7.9) | 2.9 | 20.8 | 2.7§ | 31.9 (10.6) | 19.8 | 44.0 | 3.3§ |

| Pennsylvania | 12.1 (3.0) | 9.4 | 16.8 | 1.0§ | 27.8 (6.3) | 18.6 | 32.6 | 1.8§ |

| Arizona | 12.0 (3.7) | 7.0 | 13.4 | 0.8 | 29.7 (7.4) | 17.6 | 30.3 | 1.8§ |

| New Hampshire | 14.2 (2.8) | 10.5 | 14.8 | 0.5 | 32.4 (8.6) | 28.1 | 40.3 | 1.8§ |

| New Jersey | 10.0 (3.0) | 6.3 | 15.6 | 1.0 | 32.3 (6.5) | 20.8 | 31.1 | 1.5§ |

| Michigan | 18.6 (5.9) | 9.3 | 28.7 | 2.1§ | 37.4 (5.7) | 31.9 | 37.6 | 1.5§ |

| Alabama | 19.7 (3.6) | 18.5 | 20.1 | 0.7 | 29.6 (4.6) | 25.9 | 37.0 | 1.2§ |

| Tennessee | 15.4 (2.8) | 9.2 | 20.1 | 0.7 | 26.3 (4.7) | 22.2 | 27.3 | 1.1§ |

| Florida | 10.2 (2.1) | 6.9 | 10.7 | 0.6§ | 17.7 (2.8) | 13.9 | 18.8 | 0.7§ |

| North Carolina | 13.5 (2.5) | 9.1 | 14.5 | 0.6 | 25.3 (2.9) | 19.3 | 25.2 | 0.6§ |

| Vermont | 17.5 (8.6) | 10.4 | 17.0 | 1.9 | 29.2 (7.6) | 19.3 | 33.1 | 1.6 |

| Oregon | 13.3 (2.1) | 12.1 | 14.9 | 0.5§ | 28.2 (7.3) | 18.3 | 24.8 | 1.2 |

| Rhode Island | 18.0 (9.7) | 8.4 | 39.4 | 2.9§ | 38.7 (7.9) | 32.3 | 43.8 | 1.1 |

| Montana | 20.1 (6.9) | 9.4 | 23.5 | 2.0§ | 32.6 (5.1) | 21.6 | 36.1 | 0.6 |

| Idaho | 16.8 (6.7) | 15.7 | 28.1 | 1.5§ | 30.6 (2.9) | 27.5 | 35.2 | 0.6 |

| Kentucky | 14.6 (1.9) | 13.0 | 16.2 | 0.4 | 22.1 (4.1) | 18.7 | 19.6 | 0.6 |

| Nevada | 13.0 (6.2) | 11.6 | 23.3 | 1.7§ | 26.9 (5.0) | 19.7 | 29.2 | 0.2 |

| Kansas | 11.8 (3.8) | 7.2 | 16.2 | 1.0§ | 20.6 (2.1) | 18.1 | 19.7 | 0.2 |

| Washington | 14.1 (3.6) | 13.9 | 18.6 | 0.9 | 25.9 (3.6) | 20.6 | 22.3 | 0.1 |

| Wyoming | 13.9 (6.2) | 18.4 | 9.2 | 0.2 | 26.7 (10.4) | 27.5 | 24.8 | −0.1 |

Number of living kidney donations per 1 000 000 population.

Includes only states not enacting legislation to reward or incentivize living kidney donation during the study; listed in descending order according to mean change in donation rate after 1997, when federal initiatives commenced.

SD = standard deviation.

= Change is statistically significantly positive or negative in direction.

Association of state legislation with rates of donation

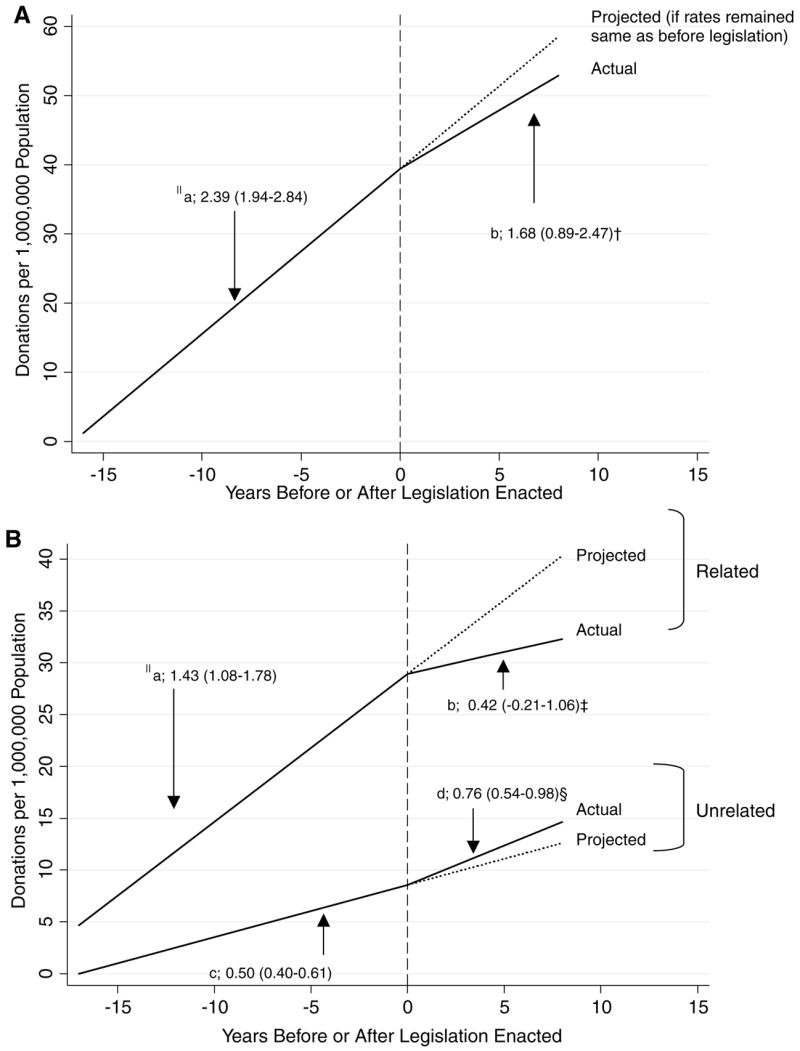

In analyses accounting for length of time state legislation had been enacted, the types of legislation present and the incidence and prevalence of ESRD in each state, there was no statistically significant difference in the average rate of increase in overall living kidney donations after states enacted their first legislation when compared to the rate of increase in donations prior to states’ enactment of their first legislation (average annual increase of 1.68 (95% CI: 0.89–2.47) donations per 1 000 000 after enactment of first legislation compared to average annual increase of 2.39 (95% CI: 1.94–2.84) donations per 1 000 000 prior to enactment of first legislation, p = 0.06) (Figure 2A). The association of state legislation with living-related and unrelated donors differed. There was statistically significantly less growth in living-related kidney donations after states enacted their first legislation when compared to the rate of increase in donations prior to states’ enactment of their first legislation. In contrast, there was a statistically significantly greater average rate of increase in living-unrelated donations after states enacted their first legislation compared to the rate of increase in donations prior to states’ enactment of their first legislation (Figure 2B). Results of main analyses did not change when accounting for states’ deceased kidney donation rates during the study.

Figure 2. Adjusted mean overall living kidney donation rate* (A) and living-related and unrelated rate (B) for states with legislation enacted according to number of years rate was measured before or after legislation.

*Adjusted mean donation rates estimated using linear spine function assessing differences in rates of donation before and after legislation enactment. Year ‘0’ represents the year legislation was enacted for each state. Negative years represent years before legislation was enacted for each state; positive numbers represent years after legislation was enacted for each state. Solid lines represent adjusted (for annual incidence and prevalence of end-stage renal disease in each state and type of legislation enacted) mean donation rate among states. Dotted lines represent projected mean rate of donation in legislation had not been enacted in states. (A) §Slopes of regression lines represent mean increase in overall living kidney donation rate per year during years before legislation was enacted in states (a) and mean increase in overall living kidney donation rate per year during years after legislation was enacted in states (b) presented as mean slope (95% CI). †Mean increase in rate per year after legislation was enacted not statistically significantly greater than before legislation was enacted (change (95% CI): −0.71 (−1.43 to 0.02), p = 0.06. (B) §Slopes of regression lines represent mean increase in donation rate per year during years before legislation was enacted in states (a) and mean increase in living-related kidney donation rate per year during years after legislation was enacted in states (b) or mean increased in living-unrelated kidney donation rate per year during years before legislation was enacted (c) and mean increase in living-unrelated kidney donation rate per year during years after legislation was enacted (d) presented as mean slope (95% CI). ‡Mean increase in rate per year after legislation was enacted statistically significantly less than rate of increase before legislation was enacted (change in mean increase (95% CI): −1.00 (−1.59 to −0.42), p < 0.01). §Mean increase in rate per year after legislation was enacted statistically significantly greater than rate of increase before legislation was enacted (change in mean increase (95% CI): 0.26 (0.04 to 0.47), p = 0.02).

Association of federal initiatives with rates of donation

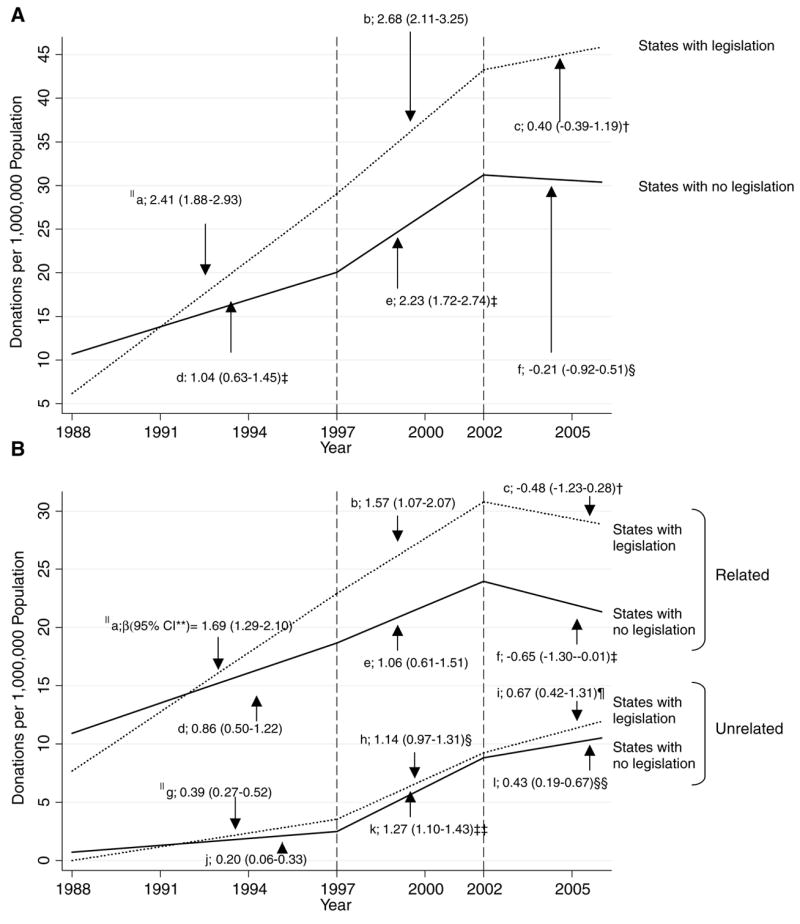

Analyses assessing secular trends due to national initiatives (which commenced in 1997) to enhance living donation revealed that states with legislation experienced similar annual increases in overall living kidney donation rates before 1997 and from 1998 to 2002, but they experienced no statistically significant annual increase in donation rates after 2002. States without legislation experienced a greater mean annual increase in donation rates from 1997 to 2002 compared to before 1997 but experienced no statistically significant annual increase in donation rates after 2002 (Figure 3A). Changes in the annual increase in donation rates after 2002 compared to the annual increase from 1998 to 2002 were no different between states with legislation and states without legislation (change in annual increase in donation among states with legislation −2.28 (95% CI: −3.29 to −1.27) donations per 1 000 000, and change in annual increase in donation among states without legislation −2.44 (95% CI: −3.43 to −1.46) per 1 000 000, p > 0.05). Secular trends in donation differed among living-related and unrelated donations. Both states enacting legislation and states not enacting legislation experienced no statistically significant change in the average annual rate of increase in living-related donations from 1997 to 2002 compared to before 1997. After 2002, both states enacting legislation and states not enacting legislation experienced statistically significantly different changes in living-related donation rates (states enacting legislation experienced a plateau in annual growth while states not enacting legislation experienced a decline in annual growth). In contrast, both states enacting their own legislation and states not enacting legislation experienced a statistically significantly greater annual increase in the rate of living-unrelated donations from 1997 to 2002 compared to before 1997, but states also experienced statistically significantly less growth in living-unrelated donations after 2002 compared the period from 1997 to 2002 (Figure 3B). Results of main analyses did not change when accounting for states’ deceased kidney donation rates during the study.

Figure 3. Adjusted mean overall living kidney donation rate* (A) and living-related and unrelated donation rate (B) for states with and without legislation enacted before 1997 when federal initiatives commenced, from 1997 to 2002, and after 2002.

*Adjusted mean donation rates estimated using linear spine function assessing differences in rates of donation from before 1997, when federal legislation/initiatives commenced, from 1997 to 2002, and from 2002 to 2006. Dotted lines represent adjusted (for annual incidence and prevalence of end-stage renal disease in each state) mean donation rate among states with legislation. Solid lines represent adjusted (for annual incidence and prevalence of end-stage renal disease in each state) mean donation rate among states without legislation. (A) §Slopes of regression lines represent mean increase in overall living kidney donation rate per year before 1997 (a), from 1997 to 2002 (b), and after 2002 (c) for states with legislation; and mean increase in overall living kidney donation rate per year before 1997 (d), from 1997 to 2002 (e), and after 2002 (f) for states without legislation; presented as mean slope (95% CI). **CI = Confidence Interval. †Mean increase in rate per year after 2002 (c) statistically significantly less than mean increase in rate per year during 1997–2002 (b) for states with legislation (change (95% CI): −2.28 (−3.29 to −1.27), p < 0.01). ‡ Mean increase in rate per year from 1997–2002 (e) statistically significantly greater than mean increase in rate per year before 1997 (d) for states without legislation (change (95% CI): 1.18 (0.57 to 1.81), p < 0.01). §Mean decrease in rate per year after 2002 (f) statistically significantly less than mean increased in rate per year during 1997–2002 (e) for states without legislation (change (95% CI): −2.44 (−3.43 to −1.46), p < 0.01). (B) §Slopes of regression lines represent mean increase in living-related and living-unrelated donation rates (respectively) per year before 1997 (a and g), from 1997 to 2002 (b and h), and after 2002 (c and i) for states with legislation; and mean increase in living-related and unrelated donation rates (respectively) per year before 1997 (d and j), from 1997 to 2002 (e and k), and after 2002 (f and l) for states without legislation; presented as mean slope (95% confidence interval). †Mean increase in rate per year after 2002 statistically significantly less than rate of increase during 1997–2002 (change in mean increase (95% CI): −2.05 (−2.92 to −1.19), p < 0.01). ‡Mean decrease in rate per year after 2002 statistically significantly less than rate of increase during 1997–2002 (change from previous mean increase (95% CI): −1.71 (−2.61 to −0.82), p < 0.01). §Mean increase in rate per year from 1997 to 2002 statistically significantly greater than rate of increase before 1997 (change in mean increase (95% CI):0.75 (0.56 to 0.94), p < 0.01). ¶Mean increase in rate per year after 2002 statistically significantly less than rate of increase during 1997–2002 (change in mean increase (95% CI): −0.47 (−0.77 to −0.17), p < 0.01). ‡‡Mean increase in rate per year from 1997 to 2002 statistically significantly greater than rate of increase before 1997 (change in mean increase (95% CI):1.07 (0.86 to 1.28), p < 0.01). §§Mean increase in rate per year after 2002 statistically significantly less than rate of increase during 1997–2002 (change in mean increase (95% CI): −0.84 (−1.17 to −0.51), p < 0.01).

Discussion

In this 19-year national study of living kidney donation rates, we found, after accounting for the length of time legislation was enacted and the incidence and prevalence of ESRD in each state, that increases in living-related kidney donations (which comprised a majority of all donations) were no greater after the institution of state or federal public policies compared to before policies were instituted. In contrast, rates of living-unrelated donation were associated with state and federal policies, suggesting policies may selectively decrease barriers to living-unrelated kidney donation. These findings inform ongoing efforts at state and federal levels to enhance living donation and may provide insight to avenues for future improvement in living organ donation rates.

A great deal of attention has been devoted to identifying mechanisms through which disincentives to living organ donation can be overcome. Debate regarding which types (if any) and what magnitude of incentive for living donors are most appropriate from legal and ethical standpoints has been a prominent component of this dialog (61–69). Many have rejected arguments for payment to donors (e.g. tax credits or regulated organ sales), citing their potential to exploit persons of less socioeconomic means, the possibility of violating the National Organ Transplant Act (which forbids the transfer of organs for valuable consideration in transplantation) and the possibility of minimizing the value of what many consider an altruistic gift (61,63,69–71). However, proponents have proposed modest rewards that provide reimbursement for expenses of travel, housing and lost wages incurred by donors (which would not necessarily enrich potential donors, and would not leave donors more physically and financially worse-off as before their donation) as potentially acceptable (61,68). The current state legislation we studied has been modeled after this latter approach, providing some protection from financial losses associated with donation (by protecting lost wages and providing arguably minimal financial relief through benefits in state income taxes) and by allowing time for donors’ convalescence. Additional policies at the federal level currently undergoing evaluation provide reimbursement for subsistence expenses incurred by donors (including financial support for travel, lodging and meals) (72). Our study suggests interventions, as currently formulated, are only associated with living-unrelated kidney donation and not associated with sustained improvements in the larger numbers of living-related donations and therefore overall living donation rates.

Although recent studies suggest the U.S. public views paid leave and reimbursed medical expenses for living donors favorably (73), little is known regarding the magnitude of compensation or reimbursement needed to have an effect on donation behaviors. A regional study demonstrated potential living donors are very sensitive to financial risks associated with donation (43). We are aware of no studies assessing the potential effects of offering differing magnitudes of compensation for potential living donors on donation rates and we are aware of no studies assessing the potential effect of varying types of legislation on persons of low financial means. Current legislation addresses only employed persons or persons with enough income to benefit from a $10 000 tax credit or deduction, and therefore offers no provisions to persons who may be unemployed or with minimal incomes (who are likely face greater financial hardship when considering living donation). In addition, most legislation mandating paid leave is limited to state employees who represent a very small proportion (1% to 4%) of the total population in each state, therefore severely limiting the potential impact of legislative efforts. While our findings suggest these current policies are associated with an increase in living-unrelated donation rates, further work is needed to identify whether legislation has had any untoward effect on access to living kidney transplantation and willingness to donate among segments of the population such as those with less financial means.

Public initiatives are intended not only to improve the donation experience for those who have already chosen to donate but also to raise awareness among the general public regarding the need for living donation. Although some initiatives are aimed at a narrow audience (i.e. paid leave mandated for mostly state and local government employees), awareness raising campaigns may have an effect on potential living-unrelated donors who have limited knowledge about the need for kidney donation. The presence of legislation may also more significantly relieve potential unrelated donors’ perceptions of barriers to donation when compared to the majority of donors who are emotionally or biologically related to recipients. Barriers to living-related donation vary and include potential transplant recipient attitudes (including concern regarding risks to donors’ health and finances and their perceptions of ESRD) (74–76), potential donor knowledge (77,78) or attitudes (43,43,79) and family attributes (including poor patient, family and physician communication and family cohesion) (74,80). Interventions performed at the level of individual patients, families and health care providers may prove more effective in enhancing rates of living-related donation than interventions implemented at the population level. Our results do not provide guidance as to whether legislative efforts should be abandoned entirely. Although these policies are not associated with improvements in living-related donation rates, other studies that quantify the value of existing public initiatives (or their accessibility to the public) in addressing potential donors’ concerns are needed (81).

The observed decline in growth of living-related donation rates after states enacted legislation should be interpreted with caution. Both states enacting legislation and states not enacting legislation experienced a statistically significant slowing of growth in donation rates after 2002, suggesting an unrelated temporal phenomenon affecting living-related donation rates in the continental U.S. Further research is needed to understand reasons for slowed growth in donation rates despite a growing need for donations after 2002 (3). It is possible the success of recent efforts to enhance rates of deceased donation, including the Organ Donation Breakthrough Collaborative by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration, has drawn attention away from efforts to improve rates of living donation by lessening perceived pressures regarding need for living kidney donation (1,2). However, sensitivity analyses accounting for deceased kidney donation rates in each state demonstrated no change from main findings, suggesting this was not the case.