Abstract

Metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) resulting from sustained hyperglycemia are considered as risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD) but the mechanism for their contribution to cardiopathogenesis is not well understood. Hyperglycemia induces nonenzymatic glycation of protein-yielding advanced glycation end products (AGE), which are postulated to stimulate interleukin-6 (IL-6) expression, triggering the liver to secrete tissue necrosis factor α (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (CRP) that contribute to CVD pathogenesis. Although the high prevalence of periodontitis among individuals with diabetes is well known by dental researchers, it is relatively unrecognized in the medical community. The expression of the same proinflammatory mediators implicated in hyperglycemia (i.e., IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP) have been reported to be associated with periodontal disease and increased risk for CVD. We will review published evidence related to these 2 pathways and offer a consensus.

Approximately 20.8 million Americans have been diagnosed with diabetes, and this number is increasing.1 Nearly three quarters of the diabetic population develop cardiovascular disease (CVD) and die of cardiovascular complications.1 Metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes (T2DM) resulting from sustained hyperglycemia are considered as risk factors for CVD, but the mechanism for their contribution to cardiopathogenesis is not well understood.2 It is presumed that hyperglycemia induces nonenzymatic glycation of proteins, and resultant advanced glycation end products (AGEs) are known to stimulate macrophages to express cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α [TNF-α], and C-reactive protein [CRP]).3 These cytokines induce the liver to secrete acute phase reactants that are implicated in the inflammatory process related to CVD pathogenesis, such as CRP, fibrinogen, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1, and serum amyloid A.

Although the high prevalence of periodontitis among individuals with diabetes is widely known among dental researchers, it is not well recognized in the medical community. The expression of the same proinflammatory mediators implicated in hyperglycemia (i.e., IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP) has been reported to be associated with oral infection4 and increased risk for CVD among persons who have periodontal disease.5

Our group has recognized the dual pathways leading to CVD from the oral cavity and estimated the combined effects of these inflammatory burdens.6 We will further review the evidence linking oral health to endothelial dysfunction, the initial step in diabetes and CVD, through carbohydrate metabolism and/or oral infection.

CARBOHYDRATE METABOLISM PATHWAY

Glycemic index

The United States Department of Agriculture recommendation for a low fat/high carbohydrate diet appears to coincide with burgeoning weight gain, obesity, and T2DM among the US population,7 prompting the scientific community to hypothesize that there might be a causal association between these 2 phenomena.

One measure of carbohydrate quality in this perspective is by monitoring how fast the carbohydrate is absorbed, raises blood sugar level, and induces insulin secretion. The relative blood glucose-raising ability of a food expressed by the percentage of the same achieved by reference foods (glucose or white bread) is called the glycemic index (GI).8 It is presumed that the higher the GI of a food, the more likely it will contribute to insulin resistance, endothelial dysfunction, and subsequent CVD.

Glycemic load is the weighted sum of GI by the amount of carbohydrate. The concepts of GI and glycemic load are an extension of the fiber hypothesis,9 suggesting that the fiber content of food slows the rate of absorption of nutrients from the intestine. The old classification of complex and simple carbohydrates, based on the chain length of saccharides, has proven to be less predictive of postprandial serum glucose level and future disease risk.

Many foods that require concentrated mastication tend to have low GIs and render greater health benefits.10 Clearly, fiber is an integral part of slow absorbing carbohydrates yielding lower GI. The benefits of high fiber in the diet for the prevention of CVD have been reported numerous times,9,11-14 and healthy teeth are a fundamental requirement for fiber intake. The intake of fiber by edentulous persons was significantly lower than that of dentate subjects.15

Several studies reported a decrease in plasma glucose levels or triglyceride levels that are beneficial in preventing CVD16 with low GI diets. And yet, the controversy surrounding the benefit of GI on CVD risk profile is continuing—some in disapproval17 and some in support.18 Clearly, more research is needed to establish the role of GI in CVD prevention.

Physiology of carbohydrate metabolism

The hypothesized mechanism subsequent to ingestion of the carbohydrates with high glycemic indices is as follows: blood glucose rises quickly, as does the secretion of insulin. Even after the high glucose level has been brought under control, the secretion of insulin continues and brings the blood sugar level even lower than the initial glucose level.

This hypoglycemic state stimulates secretion of counterregulatory hormones such as corticosteroids, glucagon, and epinephrine in an attempt to maintain euglycemia.19 Further attempts to recover from the hypoglycemia induce glycogenolysis, lipolysis, and thus results in elevated free fatty acids. Elevated free fatty acids, in turn, may contribute to insulin resistance as well as lipotoxicity.19,20 Repeating these processes may eventually cause beta cell failure and T2DM. In addition, the secretion of counterregulatory hormones causes vasoconstriction and increased sympathetic tone, which in itself may be detrimental to vascular health by causing hypertension.21

Conversely, intake of foods with low GI will avoid this abrupt surge on blood glucose level and subsequent hypoglycemic period and therefore may attenuate some of the untoward effects of counterregulatory hormones, such as lipolysis, glycogenolysis, and elevated free fatty acids.

Carbohydrate metabolism, endothelial dysfunction, and T2DM

Type 2 diabetes is postulated as a disruption in homeostasis of glucose metabolism.20 As described in the previous section, repeated cycles of hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia may induce lipemia, insulin resistance, and β-cell exhaustion, all of which underscore the etiology of T2DM. Several prospective follow-up studies reported that GI and glycemic loads are associated with future metabolic syndrome and T2DM.22-24

Metabolic syndrome, also know as syndrome X, is a cluster of several signs and symptoms preceding clinically determinable diabetes. In as early a stage as metabolic syndrome, impaired glucose metabolism was reported to be associated with elevated CRP, suggesting a role of glucose metabolism in the inflammatory processes associated with cardiopathogenesis.22

It has been reported that edentulous patients favor a carbohydrate-rich diet,25 and fiber intake among the edentulous population was lower than that of dentate patients.15 It is plausible that the elevated CRP among edentulous subjects might be attributable to the increased level of AGEs, in addition to the possibility of previous oral infection.26 Furthermore, edentulism was associated with lower intake of fruits and vegetables that are beneficial for cardiac health.27 Taken together, this evidence suggests that oral health may impact on the development of diabetes and CVD via 2 pathways—through diet and oral infection.6

Diabetes, endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerosis

Abnormal glucose metabolism has been recognized as a major risk factor for future CVD.18 However, this assumption did not consider the fact that extremely high prevalence of periodontitis among diabetic patients and the observed risk increase might be partially attributable to oral infection. We found only 1 reference stating this possibility in the medical literature,28 whereas extensive evidence has been compiled in dental literature.4,29,30

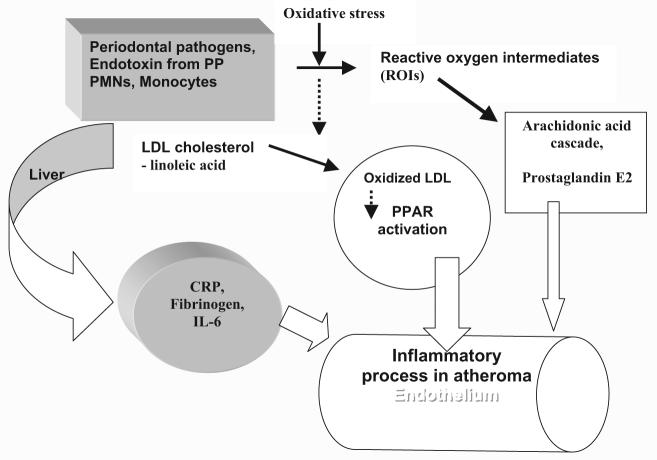

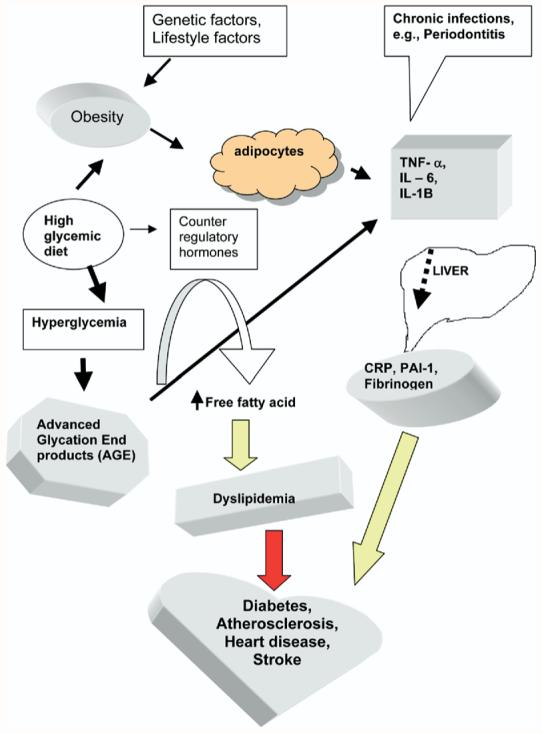

Hyperglycemia induces nonenzymatic glycation of proteins, and resultant AGEs are known to stimulate macrophages to express cytokines (e.g., IL-6 and TNF-α). These cytokines induce the liver to secrete acute phase reactants that are implicated in the inflammatory process related to atherogenesis. The mechanism of this process viewed by nutrition researchers is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Dietary factors and endothelial dysfunction and cardiovascular disease.

ORAL INFECTION PATHWAY

Oral infection, endothelial dysfunction, and atherosclerosis

The controversy surrounding oral infection and its role in CVD has been subdued by several randomized trials which successfully demonstrated that periodontal treatment decreased proinflammatory mediators associated with cardiopathogenesis and/or endothelial dysfunction.31-34

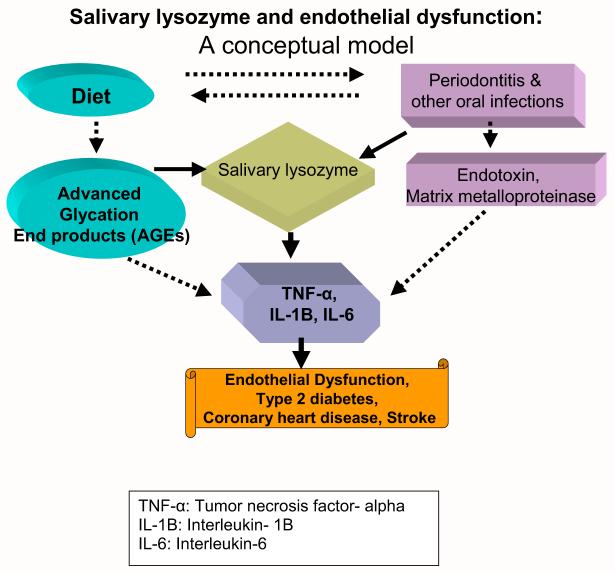

The postulated mechanism where periodontal pathogens may contribute to atherosclerosis has been offered by several researchers and may be summarized as follows35: periodontal pathogens may summon polymorph nuclear leukocytes and monocytes. This process may generate oxidative stress as well as periodontal tissue destruction. Reactive oxygen intermediates produced by this stress may oxidize low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, which is a risk factor for CVD. Concurrently, the by-products of these leukocytes may stimulate the liver to express CRP, IL-6, fibrinogen, and other proinflammatory mediators. These molecules in turn initiate the inflammatory process leading to atheroma formation in the endothelium.36 We present a simplified version of the suggested mechanisms in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Oral infection and cardiovascular disease. PP, periodontal pathogens; LDL, low density lipoprotein; CRP, C-reactive protein; PMN, polymorph nuclear leukocytes; IL-6, interleukin 6; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Modified from Offenbacher et al.35

Grossi and Genco37 described a similar process, reporting that AGE is a causative initiator of atherosclerosis in addition to periodontal pathogens. In this model, they proposed that the combination of these 2 pathways, infection and AGE-mediated cytokine up-regulation, explain the increased tissue destruction seen in diabetic periodontitis.37 This can be viewed as the AGE-related inflammatory process, and oral infection may share a common pathway via TNF-α, and CRP.

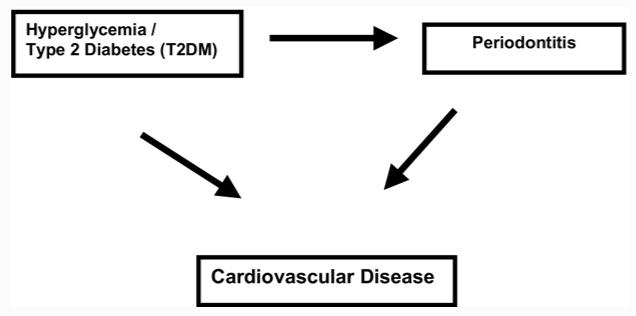

A confounding situation occurs when 2 factors are causally associated with the same outcome and the 2 factors themselves are related. Thus, in this triangular relationship (Fig. 3), to evaluate the independent relationship of periodontal treatment as the sole cause for the decreased risk of CVD, the source of AGE should be held constant.

Fig. 3.

The relationship of periodontitis, hyperglycemia, and cardiovascular disease.

Similarly, to evaluate the independent contribution of hyperglycemia to inflammatory processes in CVD pathogenesis, oral infection must be controlled as a confounder. Unless oral infection is controlled, it is possible that the significant risk increases for CVD associated with diabetes/hyperglycemia may be due to periodontal infection.

An alternative way to bypass this confounding situation is to find a biomarker that may measure the combined contribution of oral health in this relationship, as we have done previously.6 The details of our approach will be discussed in the next section.

COMBINED CONTRIBUTION OF ORAL HEALTH TO CVD

Merging the 2 pathways and future directions

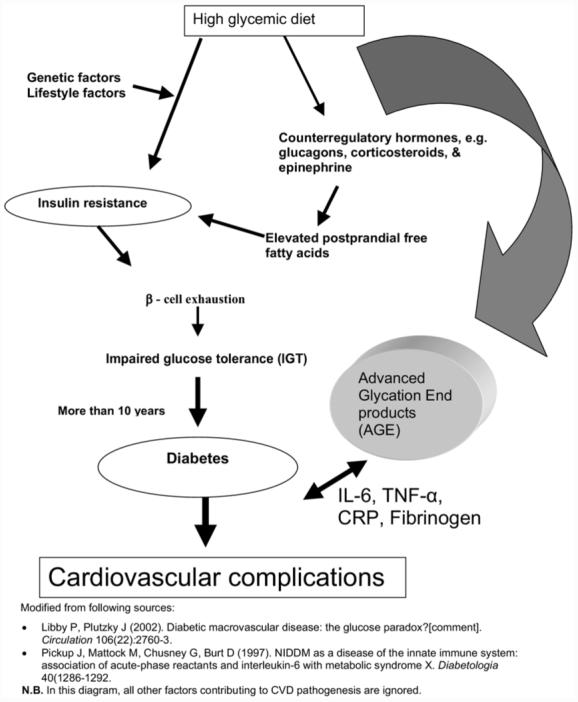

Infection is an important trigger for activation of sentinel cells such as macrophage in the innate immune system. Periodontal pathogens have been proven to invade atheromas38 as well as endothelium.39 Diet and psychological stress also triggers the immune system40 and complicates the determination of the source for cytokine expression. We have compiled these relationships in Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Combined effects of dietary factors and oral infection on cardiovascular disease. TNF-α, Tumor necrosis factor-α; IL-6, interleukin 6; IL-1B, interleukin 1B; PAI-1, plasminogen activator inhibitor 1.

In the oral infection pathway, mucosa is a portal for many biologic molecules, as evidenced by the fact that some vaccines are given via nasal or bronchial mucosa. Therefore, all oral mucosal lesions (i.e., periodontitis, pericoronitis, gingivitis, and miscellaneous other mucositis) should be considered as potential trigger sources of cytokines and other inflammatory mediators. Our group has reported that a mathematically summed score from several types of oral mucositis was significantly associated with coronary artery disease.41

Some researchers postulated that the number of teeth might represent the effects of previous oral infection and additional diet-related proinflammatory process associated with cardiovascular pathogenesis.42 However, the number of teeth appears to be a proxy for oral infection in cardiopathogenesis, because we found that our asymptotic dental score41 was inversely correlated to the number of remaining teeth (γ = -0.8; P = .001). The asymptotic dental score is a mathematically summed score derived from 5 oral infection sources: pericoronitis, gingivitis, dental caries, root tips, and edentulism.

Moreover, accountings for only infection or only diet will underestimate the role of oral health in cardiovascular health. Alternatively, if we measure a biomarker that correlates to cytokines and acute phase reactants through both of these 2 pathways (e.g., diet and infection), it may estimate the total contribution of oral health to vascular health. We postulated that salivary lysozyme (SLZ) might be an appropriate biomarker representing these 2 pathways.

Lysozyme has a domain that shows strong affinity for AGEs and has been used to filter AGEs in diabetic nephropathy.43 In addition, lysozyme is derived from leukocytes and is a part of the innate immune system mobilized by infection.44 Thus, we postulate that SLZ may well quantify the combined attribution of oral health in CVD pathogenesis. We illustrated this combined input of oral health to endothelial dysfunction as a simplified conceptual model in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Salivary lysozyme and endothelial dysfunction leading to cardiovascular disease.

The dotted arrows are only one arm of this equation, and solid arrows illustrate combined input from the oral cavity measured by SLZ. We observed a much stronger association between SLZ and coronary artery disease6 than either periodontal disease and coronary artery disease45 or nutrition intake and CHD.27 The top quartile of SLZ, compared with the lowest, was associated with an odds ratio of 3.62 for coronary artery disease, controlling for other established systemic risk factors such as age, sex, smoking, cholesterol, hypertension, diabetes, education as a proxy for socioeconomic status, and systemic CRP.6 Future prospective studies and/or randomized trials are needed to confirm our findings.

Lysozyme, discovered by Sir Alexander Fleming, has the potential to be a coronary artery disease risk assessment marker.6 Currently, we are investigating whether SLZ can predict cardiovascular mortality in a 10-year follow-up study. Subsequently, we plan to examine whether reducing SLZ will lower the risk of developing coronary artery disease or cardiovascular mortality.

In conclusion, both diet and oral infection should be considered in the estimation of total ascription of oral health in CVD pathogenesis. Salivary lysozyme may be a marker for the total inflammatory output from the oral cavity that contributes to cardiopathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

This review was supported by The National Scientist Development Grant from the American Heart Association (S.-J.J.), the Intramural Program of the National Institutes of Health (A.E.B.), the Helsinki University Central Hospital (grant TYH 3245 to J.H.M.), the Ulf Nilsonne Foundation, SalusAnsvar Prize (J.H.M.), the Paivikki and Sakari Sohlberg Foundation (J.H.M.), Boston University (J.A.J.), and the National Institutes of Health (T.E.V.D., grant DE13191).

We thank Simin Liu, MD, ScD, for instruction that made this review possible. We also thank Susan Schur for her editorial service.

Footnotes

The opinions expressed in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent official policy of the funding agencies. All authors declare no conflict of interest. The funding sources had no influence in this review.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Diabetes Association Diabetes facts and figures. Available at: http://www.diabetes.org.

- 2.Playford D, Watts GF. Endothelial dysfunction, insulin resistance and diabetes: exploring the web of causality. Aust N Z J Med. 1999;29:523–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1999.tb00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Libby P, Plutzky J. Diabetic macrovascular disease: the glucose paradox [comment]? Circulation. 2002;106:2760–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000037282.92395.ae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kurtis B, Develioglu H, Taner IL, Balos K, Tekin IO. IL-6 levels in gingival crevicular fluid (GCF) from patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM), adult periodontitis and healthy subjects. J Oral Sci. 1999;41:163–7. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.41.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amar S, Gokce N, Morgan S, Loukideli M, Van Dyke TE, Vita JA. Periodontal disease is associated with brachial artery endothelial dysfunction and systemic inflammation [comment] Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1245–9. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000078603.90302.4A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Janket SJ, Meurman JH, Nuutinen P, Qvarnstrom M, Nunn ME, Baird AE, et al. Salivary lysozyme and prevalent coronary heart disease: possible effects of oral health on endothelial dysfunction. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:433–4. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000198249.67996.e0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reaven G. Do high carbohydrate diets prevent the development or attenuate the manifestation (or both) of syndrome X? A viewpoint strongly against. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1997;8:23–7. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199702000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, Barker H, Fielden H, Baldwin JM, et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange [comment] Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:362–6. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.3.362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenkins DJ, Kendall CW, Vuksan V, Vidgen E, Parker T, Faulkner D, et al. Soluble fiber intake at a dose approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for a claim of health benefits: serum lipid risk factors for cardiovascular disease assessed in a randomized controlled crossover trial. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:834–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/75.5.834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Granfeldt Y, Bjorck I, Drews A, Tovar J. An in vitro procedure based on chewing to predict metabolic response to starch in cereal and legume products. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992;46:649–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bazzano LA, He J, Ogden LG, Loria CM, Whelton PK, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiological Follow-up Study Dietary fiber intake and reduced risk of coronary heart disease in US men and women: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1897–904. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.16.1897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown L, Rosner B, Willett WW, Sacks FM. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis [comment] Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69:30–42. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Held C, Bjorkander I, Forslund L, Rehnqvist N, Hjemdahl P. The impact of diabetes or elevated fasting blood glucose on cardiovascular prognosis in patients with stable angina pectoris. Diabetic Med. 2005;22:1326–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2005.01643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins DJ, Jenkins AL. The glycemic index, fiber, and the dietary treatment of hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr. 1987;6:11–7. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1987.10720160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nowjack-Raymer RE, Sheiham A. Association of edentulism and diet and nutrition in US adults. J Dent Res. 2003;82:123–6. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jenkins DJ, Jenkins AL. The glycemic index, fiber, and the dietary treatment of hypertriglyceridemia and diabetes. J Am Coll Nutr. 1987;6:11–7. doi: 10.1080/07315724.1987.10720160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pi-Sunyer FX. Glycemic index and disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:290S–8S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.264S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu S, Willett WC. Dietary glycemic load and atherothrombotic risk. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2002;4:454–61. doi: 10.1007/s11883-002-0050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease [comment] JAMA. 2002;287:2414–23. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.18.2414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willett W, Manson J, Liu S. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and risk of type 2 diabetes. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:274S–80S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76/1.274S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brotman DJ. Effects of counterregulatory hormones in a high-glycemic index diet [comment] JAMA. 2002;288:695. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.6.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu S, Manson JE. Dietary carbohydrates, physical inactivity, obesity, and the ‘metabolic syndrome’ as predictors of coronary heart disease. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2001;12:395–404. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200108000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salmeron J, Ascherio A, Rimm EB, Colditz GA, Spiegelman D, Jenkins DJ, et al. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of NIDDM in men. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:545–50. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salmeron J, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Wing AL, Willett WC. Dietary fiber, glycemic load, and risk of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women [comment] JAMA. 1997;277:472–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.1997.03540300040031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johansson I, Tidehag P, Lundberg V, Hallmans G. Dental status, diet and cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged people in northern Sweden. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:431–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb00792.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slade GD, Ghezzi EM, Heiss G, Beck JD, Riche E, Offenbacher S. Relationship between periodontal disease and C-reactive protein among adults in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1172–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.10.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joshipura KJ, Hu FB, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Rimm EB, Speizer FE, et al. The effect of fruit and vegetable intake on risk for coronary heart disease [comment] Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1106–14. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-134-12-200106190-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colwell JA. Inflammation and diabetic vascular complications. Diabetes Care. 1999;22:1927–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.12.1927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Curtis JW., Jr. Infections associated with diabetes mellitus [comment] N Engl J Med. 2000;342:895–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Collin HL, Uusitupa M, Niskanen L, Kontturinarhi V, Mark-kanen H, Koivisto AM, et al. Periodontal findings in elderly patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. J Periodontol. 1998;69:962–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1998.69.9.962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.D Aiuto F, Parkar M, Nibali L, Suvan J, Lessem J, Tonetti MS. Periodontal infections cause changes in traditional and novel cardiovascular risk factors: results from a randomized controlled clinical trial. Am Heart J. 2006;151:977–84. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elter JR, Hinderliter AL, Offenbacher S, Beck JD, Caughey M, Brodala N, et al. The effects of periodontal therapy on vascular endothelial function: a pilot trial. Am Heart J. 2006;151:47.e41–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwamoto Y, Nishimura F, Soga Y, Takeuchi K, Kurihara M, Takashiba S, et al. Antimicrobial periodontal treatment decreases serum C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, but not adiponectin levels in patients with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1231–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tonetti MS, D Aiuto F, Nibali L, Donald A, Storry C, Parkar M, et al. Treatment of periodontitis and endothelial function. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:911–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Offenbacher S, Madianos PN, Champagne CM, Southerland JH, Paquette DW, Williams RC, et al. Periodontitis-atherosclerosis syndrome: an expanded model of pathogenesis. J Periodont Res. 1999;34:346–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Libby P, Ridker P, Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–43. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossi SG, Genco RJ. Periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus: a two-way relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:51–61. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Choi J, Chung S, Kang H, Rhim B, Kim S, Kim S. Establishment of Porhyromonas gingivalis heat-shock-protein-specific T-cell line from atherosclerosis patients. J Dent Res. 2002;81:344–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gibson FC, 3rd, Hong C, Chou HH, Yumoto H, Chen J, Lien E, et al. Innate immune recognition of invasive bacteria accelerates atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 2004;109:2801–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000129769.17895.F0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pickup J, Mattock M, Chusney G, Burt D. NIDDM as a disease of the innate immune system: association of acute-phase reactants and interleukin-6 with metabolic syndrome X. Diabetologia. 1997;40:1286–92. doi: 10.1007/s001250050822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Janket SJ, Qvarnstrom M, Meurman JH, Baird AE, Nuutinen P, Jones JA. Asymptotic dental score and prevalent coronary heart disease [comment] Circulation. 2004;109:1095–100. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118497.44961.1E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joshipura KJ, Douglass CW, Willett WC. Possible explanations for the tooth loss and cardiovascular disease relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:175–183. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng F, Cai W, Mitsuhashi T, Vlassara H. Lysozyme enhances renal excretion of advanced glycation endproducts in vivo and suppresses adverse age-mediated cellular effects in vitro: a potential AGE sequestration therapy for diabetic nephropathy? Mol Med. 2001;7:737–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Klempner MS, Malech HL. Phagocytes: normal and abnormal neutrophil host defenses. In: Gorbach SL, Bartlett JG, Blacklow NR, editors. Infectious diseases. 2nd ed. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1998. pp. 41–7. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Janket SJ, Baird AE, Chuang SK, Jones JA. Meta-analysis of periodontal disease and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke [comment] Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2003;95:559–69. doi: 10.1067/moe.2003.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]