Abstract

AIDS [Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome] Drug Assistance Programs, operating within the larger Ryan White Program, are state-based, discretionary programs that provide a drug “safety net” for low-income and uninsured individuals infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Although the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs and the primary care system that provides care for patients with HIV infection are already financially stressed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently issued guidelines recommending universal HIV testing to help identify the estimated 300,000 individuals in the United States who are unaware that they are infected with HIV. As the number of people living with HIV/AIDS who are coinfected with hepatitis C virus has grown and the cost and complexity of care have increased, the sustainability of the current HIV care system requires a reevaluation in light of the new testing guidelines. We examine the current state of the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, discuss the implications of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines for the already overstretched Ryan White Program, and consider a federally supported national program to ensure high-quality, efficient HIV care for low-income HIV-infected Americans.

People living with HIV infection in the United States rely on poorly coordinated private and public mechanisms to pay for care. Less than one-third of HIV-infected individuals receiving care in the United States are covered by private insurance (compared with 73% of adults in the United States overall) [1]. Therefore, most are uninsured or rely on public sector insurance programs. The high cost of HIV care and services, coupled with a lack of insurance coverage, is a significant barrier to care for people with HIV infection and is a strain on the systems that serve them [1]. An estimated 42%–59% of these patients are not receiving regular care for their HIV infection [2]; only 55% of those who are treatment eligible are receiving antiretroviral therapy [3].

Congress enacted the 1990 Ryan White Comprehensive Resources Emergency Act to improve health care and support services for HIV-infected individuals. The national AIDS Drug Assistance Program, operating within the Ryan White Program, serves as the drug “safety net” for primarily low-income, underinsured, or uninsured HIV-infected individuals. This program reaches approximately one-quarter of all people with HIV/AIDS who are receiving care. Since 1990, the Ryan White Program and the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs have been pivotal in reducing the burden of HIV-care delivery and providing drugs for the most vulnerable HIV-infected populations.

Many HIV-infected people in the United States do not learn of their diagnosis until the disease has progressed to advanced AIDS [4, 5]. Of the ~1 million US citizens living with HIV infection, 25% are unaware of their status [6]. To improve rates of HIV testing and detection, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently recommended a change to opt-out HIV testing in all health care settings for patients aged 13–64 years [7]. Ensuring that these patients benefit from treatment is critical to the acceptance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines by the medical and legal communities.

As the number of people living with HIV/AIDS in the United States has grown and the cost and complexity of care have increased [8], AIDS Drug Assistance Programs are increasingly stretched. Additional case finding through routine testing will progressively threaten the sustainability of AIDS Drug Assistance Programs and other Ryan White Program initiatives that provide early intervention and primary care services. We examine the current state of the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, the implications of the new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines in light of challenges faced by the Ryan White Program and the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, and strategies for resolution.

ROLE OF THE RYAN WHITE PROGRAM IN US HIV CARE

Approximately one-half of patients with HIV infection depend on Medicaid (~34%) and Medicare (~16%) programs for coverage [9]. Most states limit Medicaid eligibility to persons with low incomes and who meet Medicaid disability standards—often once they have advanced AIDS [10]. The Ryan White Program, the largest federal program designed to offer care and support services to people with HIV/AIDS and their families, serves to fill these gaps in insurance coverage [11]. The program consists of 4 main parts (table 1).

Table 1.

Structure of the Ryan White Program.

| Funding | Purpose | Fiscal year 2007 appropriation |

|---|---|---|

| Part A/Title I | Provides funding for medical and support services to >50 metropolitan areas with disproportionately large HIV/AIDS populations | $604 million |

| Part B/Title II | Provides grants to states and territories for programs designed to improve HIV/AIDS health care delivery and support services; Title II also provides access to medications through the AIDS Drug Assistance Program | $1.19 billion (including $789 million to AIDS Drug Assistance Programs) |

| Part C/Title III | Allocates funding to individual organizations and service providers for HIV testing and for early intervention services in the outpatient setting, such as case management, for those who recently received a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS | $193.6 million |

| Part D/Title IV | Provides services to children, women, and families affected by HIV/AIDS, including medical care, psychosocial services, and access to clinical research trials | $71.8 million |

NOTE. Adapted from information from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation [11].

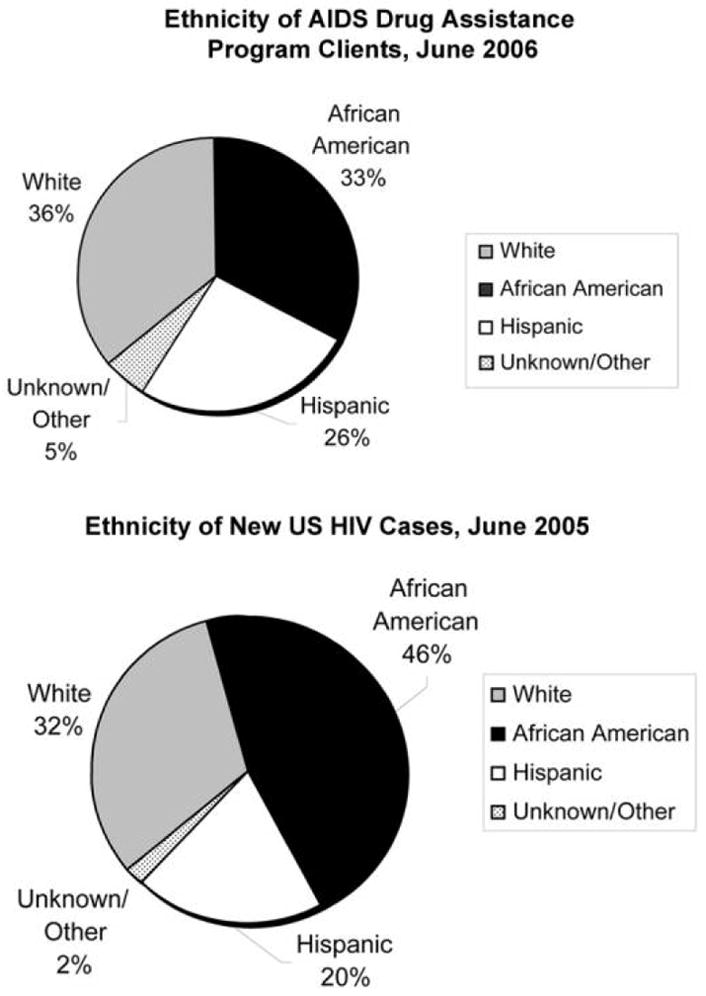

AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, funded through Part B/Title II of the program, were created to help states provide prescription drug access to HIV-infected people who lack adequate drug coverage from Medicaid or other forms of private insurance [12]; the program provides medications, but program funding can also be used by patients to purchase private insurance that includes drug coverage. More than 500,000 people with HIV/AIDS benefit each year from services funded by the Ryan White Program [13], with >141,000 AIDS Drug Assistance Program enrollees [14]. Most AIDS Drug Assistance Program clients are male, are uninsured, are from racial or ethnic minority groups, have incomes at or below the federal poverty level [14], and are representative of recent new diagnoses of HIV cases in the United States [15] (figure 1). Since 1996, spending for drugs by AIDS Drug Assistance Programs has increased >6-fold, more than twice the rate of client growth [14]. By fiscal year 2007, federal funding for Title II programs had reached >$1 billion, with >$750 million going to AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, paralleling the increasingly widespread use of potent antiretroviral therapy [13] (table 1). Yet, despite the growing number of HIV-infected people and the increases in costs of care for those living with HIV/AIDS, federal funding for the Ryan White Program has stayed the same since 2003 [11]. The impact of this plateau has been felt particularly among public and nonprofit organizations that provide community-based comprehensive primary care services for HIV-infected patients. Although patient volume has increased 30%–70%, these programs, which often provide case management and risk-reduction counseling, have seen no increase in support through Title III/Part C funding for 7 years [17, 18].

Figure 1.

Ethnicity profile of AIDS Drug Assistance Program clients, June 2006 (top), and new US HIV cases, 2005 (bottom). Top, Ethnicity data do not include Delaware, Guam, and New Mexico. Figure created by the authors with use of data from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation [14]. Bottom, Adapted from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [16].

Why have the costs of care increased disproportionately to the number of new AIDS Drug Assistance Program enrollees? Morbidity and mortality due to HIV infection have decreased since the advent of potent antiretroviral therapy [19]. Because people infected with HIV live longer than they did before such therapy, the number of patients eligible for HIV care continues to increase [15]. The cost of outpatient care has risen along with the advent of multiple HIV drug classes, resistance testing, and long-term complications of therapy and other comorbidities [8, 20]. For example, an optimized background regimen for heavily treatment-experienced patients can cost >$18,300 per year [21]; the fusion-inhibitor enfuvirtide alone costs ~$24,000 per year [22], and 48-week treatment of HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection costs ~$29,000 [23].

SUSTAINABILITY CHALLENGES FOR THE CURRENT SYSTEM

Variability in state contributions and policies

Under the Ryan White Program, federal funding is allocated to local and state governments and directly to organizations and providers [11]. However, this state-based, locally controlled discretionary program relies on annual appropriations by Congress and cannot ensure that eligible HIV-infected individuals will receive a minimum set of basic services across all states [10]. Differences in state funding and policy have led to demands on the system that outstrip program capacity and contribute to significant geographic variability in care that affects health outcomes [24]. For example, clinics that serve a rural population that are funded through Title III/Part C struggle to meet care demands for an increasing patient load, even after receiving support for antiretroviral therapy [17, 18].

This variability has been particularly well documented for availability of antiretroviral therapy; support by the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs has been termed an “accident of geographic residence” [25, p. 6]. State contributions to AIDS Drug Assistance Programs increased more than any other funding sources from fiscal year 2005 to 2006, driving 60% of the overall national AIDS Drug Assistance Programs budget growth [14]. State contributions vary substantially, however, and depend on state budgets and policy. Eleven states provide no additional support, whereas 1 state contributes 52% of the overall state AIDS Drug Assistance Program budget [14]. States with ≥1% of reported AIDS cases during the prior 2 years are now required to match their overall Ryan White Title II award on a sliding scale based on the number of years that the state has met this 1% threshold; however, states are not required to use the matching funds for AIDS Drug Assistance Programs [14]. Because AIDS Drug Assistance Programs are not entitlements like Medicaid or Medicare, the breadth of care provided by these programs is determined by both variable annual federal allowances and availability of state revenue.

Cost-containment measures used by some states result in wide-ranging income eligibility thresholds for the program, ranging from 500% of the federal poverty level in Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Ohio to 200% in North Carolina [14]. Eight states in the past year have introduced cost-containment measures other than waiting lists, including a tightening of eligibility restrictions for program entry, capped enrollment for specific drugs, and cost sharing. Although new provisions require AIDS Drug Assistance Programs to cover at least 1 medication from each of the 4 major antiretroviral classes, 2 states reduced their formulary in the past year [14]. Although states with restrictive AIDS Drug Assistance Programs incur lower drug and total costs compared with more-comprehensive AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, these restrictions correlate with shorter life expectancy [24].

One common strategy for cost containment is the waiting list; in March 2007, a total of 4 AIDS Drug Assistance Programs had waiting lists, totaling 571 people who were unable to access HIV treatment through their state AIDS Drug Assistance Program, despite meeting antiretroviral therapy eligibility criteria [14]. This unpopular policy decision was highlighted in December 2006 when 4 individuals in South Carolina died while on the waiting list for AIDS Drug Assistance Program drug coverage [26]. In the past 5 years, 20 AIDS Drug Assistance Programs have reported a waiting list for clients at some point [14].

Impact of Medicare Part D

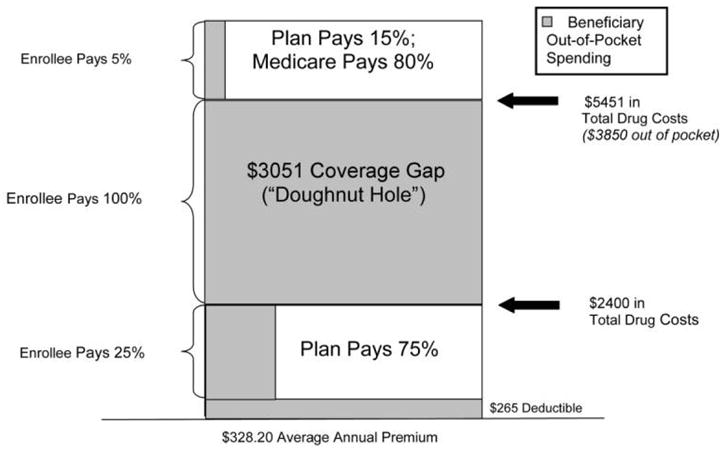

An added complexity is the relationship between AIDS Drug Assistance Programs and other possible sources of patient coverage. The Medicare Part D Program, first implemented in January 2006, provides drug benefits to Medicare beneficiaries [27]. Unlike benefits provided under the traditional Medicare program, beneficiaries must enroll with a private company and pay a monthly premium to receive Part D coverage. Soon after implementation of Medicare Part D, AIDS Drug Assistance Programs began transferring the ~12% of dually eligible clients to Part D, resulting in stabilization in the number of AIDS Drug Assistance Program enrollees served in the past year [28]. For qualified patients with HIV infection, this transition poses the “doughnut hole” challenge. The doughnut hole is the $3051 out-of-pocket expense for drugs that must be paid after the $2400 annual drug cost has been reached and before catastrophic coverage takes effect (figure 2). AIDS Drug Assistance Programs will soon be confronted with the burden of patients returning to AIDS Drug Assistance Program rosters after surpassing the coverage limit of Part D because of the high cost of HIV-related medications [14]. The ability of the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs to cope with such a challenge will have economic, policy, and clinical implications.

Figure 2.

Standard Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit, 2007. Figure depicts the doughnut hole or out-of-pocket expense incurred by a patient under the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit once the total annual drug costs exceed $2400 and before the costs exceed $5451. This information was reprinted with permission from the Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The Kaiser Family Foundation, based in Menlo Park, California, is a nonprofit, private operating foundation focusing on the major health care issues facing the nation and is not associated with Kaiser Permanente or Kaiser Industries [27].

Hepatitis C virus

Hepatitis C virus is a major HIV comorbidity in the United States, with an estimated coinfection prevalence of 16%–30% [29, 30]. Because HIV-infected individuals commonly acquire hepatitis C virus via injection drug use, a behavior correlated with lack of insurance, coinfection with hepatitis C virus is common among AIDS Drug Assistance Program clientele. Advances in HIV therapy have resulted in an increased rate of non–AIDS-related deaths, with hepatic disease the only reported cause of death for which absolute rates have increased for the HIV-infected population [31]. Patients with HIV and hepatitis C virus coinfection require 48 weeks of a costly and complex regimen of pegylated interferon and ribavirin (~$29,000) [23] and frequent clinical monitoring. Despite the high prevalence of coinfection and its associated morbidity and mortality, hepatitis C virus treatment is covered by only 25 of the 54 AIDS Drug Assistance Programs [14, 32].

CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION HIV TESTING GUIDELINES AND THE MOTIVATION FOR CHANGE

Strain on the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs and on the Ryan White Program as a whole was evident before the 2006 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendation for opt-out HIV testing in all health care settings [7]. The objective of this recommendation is to make HIV testing routine in emergency departments, inpatient services, primary clinics, and substance abuse programs, to help detect unrecognized HIV infection at an earlier stage of disease, with linkage to clinical and prevention services [7]. These guidelines should be lauded as a critical step toward improving HIV case identification, which potentially allows patients to benefit from earlier treatment that can decrease morbidity and mortality [33].

If, during the next 5 years, one-half of the estimated 300,000 HIV-infected individuals who are unaware of their status [6] are identified through increased HIV testing and if one-quarter of these individuals are eligible for drug assistance from AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, 37,500 new patients would enter the system, an increase of >25%. With a conservative estimate of 16% prevalence of hepatitis C virus in this group, 6000 of those 37,500 may require hepatitis C virus treatment in addition to eventually needing antiretroviral therapy. Accommodating this influx of patients into the current “patchwork” system of AIDS Drug Assistance Programs will pose a major challenge. HIV-screening programs must include sufficient funding for case management, primary and preventive care, and accessible treatment for those who are found to be infected [34, 35]. Because HIV testing is largely as beneficial as medical care and antiretroviral therapy [36], case management, primary and preventive care, and accessible treatment should be available in conjunction with the commitment to screening.

Disincentives for adopting routine HIV testing

In the current system, multiple forces act as disincentives to implementing routine HIV testing. With waiting lists and other caps to enrollment, many of the AIDS Drug Assistance Programs are already experiencing significant strain [14]. Physicians and clinics are reimbursed at very low rates for the delivery of HIV care, regardless of patient insurance status, even as delivery of HIV care becomes more complex and patient volume increases [17, 18, 37]. Routine testing and expedient entry into HIV care decrease inpatient costs [8, 38], which benefits hospitals, Medicare, and Medicaid, which incur those costs. However, identification of more HIV-infected patients increases outpatient drug expenditures, which are often borne by the individual AIDS Drug Assistance Programs. This lack of coordination and unification of the payment system means that the savings incurred by one system are not realized by the other.

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS: MOVING TOWARD A NATIONAL CARE PLAN

Given the imbalance in available AIDS Drug Assistance Program funds among states and the complexity of long-term care for HIV-infected patients with multiple comorbidities, the current AIDS Drug Assistance Programs are outdated and economically inefficient [12]. Because target patients are not evenly distributed among states, a standardized, nationally administered HIV entitlement program might serve to level treatment inequalities in an economically efficient manner. A national care plan would also provide incentives for diagnosing HIV infection earlier, through routine testing, because the savings from a decrease in inpatient expenditures would benefit the system as a whole. In addition, a national plan could set coverage standards to address some of the comorbidities, such as hepatitis C virus, that affect HIV-infected individuals [31].

Medicaid offers 1 model for a joint federal-state program providing medical assistance that would adhere to general guidelines specified by the federal government. The system of federal matching funds administered on a sliding scale on the basis of a state’s poverty level and HIV-infection rates may work toward reducing AIDS Drug Assistance Program inequality among the states. Despite its limitations, it is logical to consider extending Medicaid, because it is already the largest source of federal spending on health care for HIV-infected individuals. In addition, it would provide a conduit to offer more-comprehensive services, because it already lends substantial support to safety net providers, such as community and migrant health centers [39]. However, the system would need to address Medicaid’s current biggest limitation in serving HIV-infected patients by ensuring eligibility for low-income individuals when they enter care and not just when they become disabled with AIDS. In addition, a structure based on the Medicaid model would be subject to states’ abilities to fund programs that, although eligible for federal matching funds, would strain already inadequate resources [39]. One approach would be to administer the Ryan White Program as an expansion of the Medicaid program, as some states do with the State Children’s Health Insurance Program. This system would allow states the discretion to design their own benefits package on the basis of a fixed block grant derived from the number of HIV cases, with capped federal matching funds [40]. The major disadvantages would be that states could again set their own eligibility thresholds and enrollment caps, which might perpetuate state-to-state variation in coverage. Furthermore, states would have even more discretion to establish provider reimbursement rates than they currently do within Medicaid [10].

Another possible approach is a nationally run HIV-care program modeled on Medicare. Ideally, this would be a federal entitlement program that, instead of depending on annual appropriations, would allow each state to be funded on the basis of the number of eligible residents with HIV/AIDS and would be adjusted for prevalence of relevant comorbidities. This program could have parallels with Medicare’s prospective payment scheme for patients undergoing dialysis who would not otherwise qualify for Medicare benefits. Ideally, Medicare would pay for HIV care through a single bundled-payment approach for a defined set of services. This bundled-payment system would avoid the impediment and cost of separately billable medications. Such issues are well-described challenges in the dialysis program—for example, in the use of injectable medications such as epoetin alfa [41–43]. A national HIV-care program would provide a single standard of care with a consistent, defined benefit package, uniform enrollment criteria, and the option for access to services at the time of diagnosis. Because successful HIV-screening programs are intended to lead to earlier infection detection, they will lead to an increased duration of patient care service needs for a longer period before antiretroviral therapy initiation. A national HIV-care program would provide an incentive for increased testing and early diagnosis of HIV by ensuring that money saved through the prevention of hospitalization of patients with late-stage AIDS could be used to support severely burdened outpatient services.

An important attendant benefit of a federally administered national AIDS Drug Assistance Program is the federal government’s ability to negotiate pharmaceutical prices, which is particularly important, because drug costs dominate current AIDS Drug Assistance Program expenditures. All Ryan White Program grantees, including AIDS Drug Assistance Programs, may purchase their drugs through a federal drug-pricing program (Section 340B of the Public Health Service Act). However, a government accountability study found that nearly all AIDS Drug Assistance Programs reported paying higher prices than the 340B price for at least 1 of the top 10 drugs [44]. In addition, 340B prices are higher than the federal ceiling price paid by the Department of Veteran Affairs, suggesting that AIDS Drug Assistance Programs may still have more leverage in successful drug-price negotiations.

The Institute of Medicine has proposed a model for a new, federally funded, state-administered program for low-income individuals with HIV infection, The HIV Comprehensive Care Program, that would replace the Medicaid AIDS program and enroll patients at the time of HIV diagnosis for individuals with incomes ≤250% of the federal poverty level [10]. The federal government would specify patient benefits and standards for provider reimbursement for monitoring visits [10]. This plan would allow patients who do not meet financial eligibility criteria to enroll on a sliding scale, an option that could provide an enormous service, particularly to the underinsured, who are not immediately eligible for AIDS Drug Assistance Programs [10, 45].

CONCLUSION

The most vulnerable HIV-infected individuals in the United States receive care in a system plagued by inequalities and shortfalls. The potential influx of patients created by implementation of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for routine HIV testing lend new urgency to reevaluating the structure of AIDS Drug Assistance Programs and the HIV-care system as a whole [7]. The Ryan White Program and AIDS Drug Assistance Programs currently serve as a plan of “last resort” for patients in need of HIV primary care and antiretroviral therapy, with significant geographic variation in eligibility requirements, formularies, and benefits. By making a federal HIV program the “payer of first resort” as envisioned by the Institute of Medicine, a national plan should aim for prompt delivery of standardized treatment, appropriate provider reimbursement for HIV-related primary care and preventive services, and improved access to antiretroviral therapy and therapy for hepatitis C virus infection [10]. The envisioned imperative to routinely test for HIV infection will be realized only if accompanied by an imperative to provide access to treatment for HIV infection for those who are identified.

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin Linas and A. David Paltiel, for their critical review of an earlier version of the manuscript, and Lauren Uhler, for her technical assistance.

Financial support. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (K23AI068458), National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH073445 and R01 MH65869), and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation Clinical Scientist Development Award.

Footnotes

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: no conflicts.

References

- 1.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed 28 April 2008];Financing HIV/AIDS care: a quilt with many holes, May 2004. Available at: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/1607-02.cfm.

- 2.Fleming PL, Byers RH, Sweeney PA, Daniels D, Karon JM, Janssen RS. Program and abstracts of the 9th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (Seattle, WA) Alexandria, VA: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 2002. HIV prevalence in the United States, 2000 [abstract 11] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teshale E, Kamimoto L, Harris N, Li J, Wang H, McKenna M. Program and abstracts of the 12th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (Boston, MA) Alexandria, VA: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health; 2005. Estimated number of HIV-infected persons eligible for and receiving HIV antiretroviral therapy [abstract 167] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liddicoat RV, Horton NJ, Urban R, Maier E, Christiansen D, Samet JH. Assessing missed opportunities for HIV testing in medical settings. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:349–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.21251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samet JH, Freedberg KA, Savetsky JB, Sullivan LM, Stein MD. Understanding delay to medical care for HIV infection: the long-term non-presenter. AIDS. 2001;15:77–85. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200101050-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glynn M, Rhodes P. Program and abstracts of the National HIV Prevention Conference (Atlanta, GA) Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005. Estimated HIV prevalence in the United States at the end of 2003 [abstract T1-B1101] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schackman BR, Gebo KA, Walensky RP, et al. The lifetime cost of current human immunodeficiency virus care in the United States. Med Care. 2006;44:990–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000228021.89490.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleishman JA, Gebo KA, Reilly ED, et al. Hospital and outpatient health services utilization among HIV-infected adults in care 2000–2002. Med Care. 2005;43:III40–52. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000175621.65005.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Institute of Medicine. [Accessed 28 April 2008];Public HIV care: securing the legacy of Ryan White. 2005 Available at: http://www.nap.edu/execsumm_pdf/10995.pdf.

- 11.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed 28 April 2008];HIV/AIDS policy fact sheet: Ryan White Program. March; Available at: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7582_03.pdf.

- 12.Walensky RP, Paltiel AD, Freedberg KA. AIDS Drug Assistance Programs: highlighting inequities in human immunodeficiency virus–infection health care in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35:606–10. doi: 10.1086/341903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed 28 April 2008];Ryan White Care Act: care act overview. Available at: ftp://ftp.hrsa.gov/hab/CareActOverview_v8.pdf.

- 14.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed 28 April 2008];National ADAP Monitoring Project annual report. 2007 April; Available at: http://www.kff.org/hivaids/upload/7619.pdf.

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Epidemiology of HIV/AIDS—United States, 1981–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55:589–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed 28 April 2008];HIV/AIDS surveillance report, 2005. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/

- 17.Chen RY, Accortt NA, Westfall AO, et al. Distribution of health care expenditures for HIV-infected patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1003–10. doi: 10.1086/500453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saag MS. Opt-out testing: who can afford to take care of patients with newly diagnosed HIV infection? Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(Suppl 4):S261–5. doi: 10.1086/522548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palella FJ, Jr, Deloria-Knoll M, Chmiel JS, et al. Survival benefit of initiating antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected persons in different CD4+ cell strata. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:620–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-8-200304150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keiser P, Nassar N, Kvanli MB, Turner D, Smith JW, Skiest D. Long-term impact of highly active antiretroviral therapy on HIV-related health care costs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:14–9. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200105010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sax PE, Losina E, Weinstein MC, et al. Cost-effectiveness of enfuvirtide in treatment-experienced patients with advanced HIV disease. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005;39:69–77. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000160406.08924.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Drugs for HIV infection. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2006;4:67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Drugs for non-HIV viral infections. Treat Guidel Med Lett. 2007;5:59–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johri M, David Paltiel A, Goldie SJ, Freedberg KA. State AIDS Drug Assistance Programs: equity and efficiency in an era of rapidly changing treatment standards. Med Care. 2002;40:429–41. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Montgomery M. The promise of ADAP. Focus. 2007;22:4–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dewan S. Waiting list for AIDS drugs causes dismay in South Carolina. [Accessed 28 April 2008];New York Times. 2006 December 29; Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/29/us/29drugs.html?ex=1187928000&en=8f3db42eecc8187a&ei=5070.

- 27.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed 28 April 2008];The Medicare prescription drug benefit. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicare/upload/7044-06.pdf.

- 28.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed 28 April 2008];Insurance status of AIDS Drug Assistance Program (ADAP) clients. 2007 June; Available at: http://www.statehealthfacts.org/comparetable.jsp?cat=11&ind=542.

- 29.Sulkowski MS, Mast EE, Seeff LB, Thomas DL. Hepatitis C virus infection as an opportunistic disease in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;30(Suppl 1):S77–84. doi: 10.1086/313842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sherman KE, Rouster SD, Chung RT, Rajicic N. Hepatitis C virus prevalence among patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus: a cross-sectional analysis of the US adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:831–7. doi: 10.1086/339042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Palella FJ, Jr, Baker RK, Moorman AC, et al. Mortality in the highly active antiretroviral therapy era: changing causes of death and disease in the HIV outpatient study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:27–34. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000233310.90484.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chung RT, Andersen J, Volberding P, et al. Peginterferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin versus interferon alfa-2a plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C in HIV-coinfected persons. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:451–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents, Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed 28 April 2008];Guidelines for the use of antiretroviral agents in HIV-1–infected adults and adolescents. 2008 January 29;:1–128. Available at http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf.

- 34.Kim JY, Farmer P. AIDS in 2006: moving toward one world, one hope? N Engl J Med. 2006;355:645–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hanssens C. Legal and ethical implications of opt-out HIV testing. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:S232–9. doi: 10.1086/522543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paltiel AD, Walensky RP, Schackman BR, et al. Expanded HIV screening in the United States: effect on clinical outcomes, HIV transmission, and costs. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:797–806. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-11-200612050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mayer KH, Chaguturu S. Penalizing success: is comprehensive HIV care sustainable? Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1011–3. doi: 10.1086/500463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hutchinson AB, Farnham PG, Dean HD, et al. The economic burden of HIV in the United States in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: evidence of continuing racial and ethnic differences. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;43:451–7. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000243090.32866.4e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosenbaum S. Medicaid. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:635–40. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200202213460825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. [Accessed 28 April 2008];SCHIP enrollment in 50 states, 2004. Available at: http://www.kff.org/medicaid/upload/7348.pdf.

- 41.US Government Accountability Office. End-stage renal disease: Medicare should pay a bundled rate for all ESRD items and services (GAO-07-1050T) [Accessed 28 April 2008];Report to Congress. 2007 June; Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d071050t.pdf.

- 42.Leavitt MO. [Accessed 16 April 2008];Report to Congress: a design for a bundled end stage renal disease prospective payment system. 2008 Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/ESRDGeneralInformation/Downloads/ESRDReportToCongress.pdf.

- 43.Steinbrook R. Medicare and erythropoietin. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:4–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.US Government Accountability Office. Ryan White Care Act: improved oversight needed to ensure AIDS Drug Assistance Programs obtain best prices for drugs (GAO-06–646) [Accessed 28 April 2008];Report to Congress. 2006 April; Available at: http://www.gao.gov/new.items/d06646.pdf.

- 45.Vastag B. Thousands fall through HIV treatment gap: IOM wants new federal program. JAMA. 2004;292:161–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]