Abstract

This study examined the effects of deafness and intracochlear electrical stimulation on the anatomy of the cochlear nucleus (CN) after a brief period of normal auditory development early in life. Kittens were deafened by systemic ototoxic drug injections either as neonates or starting at postnatal day 30. Total CN volume, individual CN subdivision volumes, and cross-sectional areas of spherical cell somata in the anteroventral CN (AVCN) were compared in neonatally deafened and 30-day deafened groups at 8 weeks of age and in young adults after ~6 months of electrical stimulation initiated at 8 weeks of age.

Both neonatal and early acquired hearing loss resulted in a reduction in CN volume as compared to normal-hearing cats. Comparison of 8- and 32-week old groups indicated that the CN continued to grow in both deafened groups despite the absence of auditory input. Preserving normal auditory input for 30 days resulted in a significant increase in both total CN volume and cross-sectional areas of spherical cell somata, as compared to neonatally deafened animals. Restoring auditory input in these developing animals by unilateral intracochlear electrical stimulation did not elicit any difference in CN volume between the two sides, but resulted in 7% larger spherical cell size on the stimulated side. Overall, the brief period of normal auditory development and subsequent electrical stimulation maintained CN volume at 80% of normal and spherical cell size at 86% of normal ipsilateral to the implant as compared to 67% and 74%, respectively, in the neonatally deafened group.

Keywords: onset of deafness, deafening models, cochlear nucleus development, chronic electrical stimulation

1. INTRODUCTION

A wide variety of animal studies have focused on morphological and functional consequences of neonatal cochlear ablation as a model of peripheral deafness. These studies have shown losses of 25–60% of cochlear nucleus (CN) neurons and reductions in CN volume from 76% to 33%, with the extent of changes depending on the age at which the animals were deafened (Trune, 1982; Born and Rubel, 1985; Hashisaki et al., 1989; Moore et al., 1990; Tierney et al., 1997; Mostafapour et al., 2000; see Rubel and Fritzsch, 2002 for review). Together, these studies have provided evidence for a critical period in auditory development that occurs around the onset of hearing, during which the survival of the CN neurons depends on the presence of afferent input (see Harris and Rubel, 2006 for review). However, complete cochlear removal is an extreme experimental manipulation. In addition to inducing a profound hearing loss, cochlear ablation produces a loss of potential trophic influences of the primary afferent spiral ganglion neurons on the CN. Most forms of acquired human deafness do not involve direct destruction of the spiral ganglion neurons and instead affect primarily the sensory hair cells. These forms of deafness do not show evidence of significant CN cell loss, a finding that has been attributed to the fact that hair cells become susceptible to the damage only after the onset of hearing (Moore et al., 1998; Hardie and Shepherd, 1999). However, significant degeneration of the spiral ganglion neurons and degenerative changes in the CN still occur. A reduction of 25–50% in total volume of the CN and a decrease of 20–40% in spherical cell body size in the AVCN has been reported in cats deafened by ototoxic drugs as neonates (Hultcrantz et al., 1991; Lustig et al., 1994; Hardie and Shepherd, 1999; Osofsky et al., 2001; Leake et al., 2006) and in congenitally deaf animals (Saada et al., 1996; Niparko and Finger, 1997).

Because the degenerative alterations that occur in the CN in these less severe models of congenital deafness are still quite extensive, factors that can influence the extent of pathology in the developing brain are of great interest. Clinical studies suggest that after early deafness, introduction of a CI (cochlear implant) before complete maturation of the auditory system results in better CI performance and quicker adaptation to the device. The precise timing of this assumed critical period of increased auditory system plasticity is unknown, although many studies suggest that the first 5–6 years are critical for speech and language development with a CI device (Tye-Murray et al., 1995; Fryauf-Bertschy et al., 1997; Manrique et al., 1999; Connor et al., 2000; Harrison et al., 2005; Tomblin et al., 2005). Within this age group, children implanted during the first 2–3 years of life often perform significantly better than those implanted later (Kirk et al., 2002; Svirsky et al., 2004; Connor et al., 2006; Nicholas et al., 2006).

To evaluate the potential benefits of a short period of normal auditory experience, and subsequent chronic electrical stimulation delivered by a cochlear implant during development, we compared two deaf animal models. In the main study groups, ototoxic drug administration was initiated at 30 days postnatal and continued for 2–3 weeks until hearing losses were profound. Thus, these animals had normal auditory experience throughout an initial postnatal period of auditory maturation immediately before and after hearing onset. These 30-day deafened animals model early acquired deafness and correspond to post-natal, but pre-lingual hearing loss in humans.

The data were compared to a group of neonatally deafened animals, in which ototoxic drugs were administered immediately after birth, as reported in previous studies (e.g., Leake et al, 1997; Leake et al., 1999: Osofsky et al., 2001). Because the feline auditory system is very immature and non-functional at birth (kittens begin to hear at about 10 days of age), these animals become deaf before any normal auditory experience. Thus, these neonatally deafened cats model congenital deafness and are likely to correspond to a hearing loss occurring during the perinatal period in humans, in whom behavioral responses can be recorded in utero from the seventh month of pregnancy (Birnholz et al., 1983; Werner et al., 1998; see Gerhardt et al., 2000 for review).

2. METHODS

2.1. Animal Groups and Deafening Protocols

The ototoxic drug administration protocol for deafening was similar to that used previously (Leake et al., 1997; 1999) with the only difference being the time when treatment was initiated. Twelve cats were deafened starting at 30 days of age (30-day deafened groups) by daily subcutaneous injections of neomycin sulfate (60 mg/kg). Click-evoked auditory brainstem responses were used to monitor hearing loss beginning after 16 days of treatment, and repeated at 2–3 day intervals. Neomycin administration was continued until no response was observed at 110 dB SPL. Treatment periods of approximately 18–26 days were required to produce profound hearing loss and on average 30-day deafened animals required 2 days longer neomycin administration than in neonatally deafened animals.

One group of 30-day deafened animals (n=6) was studied at 8–10 weeks of age (Table 1), the other 6 animals were implanted at this age (8–9 weeks) and chronic stimulation was initiated as soon as possible (Table 2). The data from the two 30-day deafened groups with different durations of deafness were compared with data from animals that were neonatally deafened by the same ototoxic drug protocol and that were selected from prior studies to match the age at study, time of implantation, and duration of stimulation of the 30-day deafened experimental subjects. Tables 1 and 2 present a summary of the individual deafening and stimulation histories for the animals included in this study. In both age groups data were compared to age-matched normal animals (n=5 for the 8 week old group and n=6 for the 8 month old group), also acquired from previous studies.

Table 1.

Individual deafening histories for the 30-day deafened and neonatally deafened animals studied at 8–10 weeks of age.

| Cat No. | Neomycin (days) | Age at study, wks | Cat No. | Neomycin (days) | Age at study, wks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 day deafened | Neonatally deafened | ||||

|

| |||||

| K186 | 20 | 8 | K176 | 20 | 8 |

| K187 | 22 | 9 | K177 | 18 | 7 |

| K188 | 23 | 8 | K189 | 18 | 9 |

| K456 | 19 | 9 | K193 | 22 | 8 |

| K463* | 33 | 10 | K196 | 18 | 7 |

| K203 | 19 | 8 | |||

| Mean | 22.7 | 8.7 | Mean | 19.2 | 7.8 |

The dose of neomycin for K463 was increased to 70 mg/kg for the last 6 days.

Table 2.

Duration of deafness and stimulation histories1 for the 30-day deafened animals studied at 8 months of age and for the comparison group of neonatally deafened cats, matched by age at study and duration of stimulation.

| Cat No. | Neomycin (days) | Age at stimulation, weeks | Stimulation period, weeks | Stimulus | Age at study, wks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30 day deafened | |||||

|

| |||||

| K146 | 18 | 8 | 30 | 39 | |

| K149 | 19 | 8 | 29 | 37 | |

| K198 | 19 | 8 | 15 | 1,2: 325pps/30Hz | 23 |

| K446 | 24 | 9 | 18 | 3,4: 325pps/60Hz | 27 |

| K455 | 19 | 8 | 28 | 36 | |

| K200 | 22 | 9 | 30 | 39 | |

| Mean | 20.2 | 8.3 | 25 | 34 | |

|

| |||||

| Neonatally deafened | |||||

| K76 | 20 | 7 | 13 | 1,2: 300 pps/30 Hz | 20 |

| K84 | 19 | 10 | 28 | 1,2: SP | 44 |

| K98 | 20 | 7.5 | 32.5 | 1,2: SP | 40 |

| K105 | 20 | 9 | 29 | 1,2&3,4: 800pps/20Hz | 38 |

| K107 | 18 | 9 | 22 | 1,2&3,4: 800pps/60Hz | 31 |

| K130 | 21 | 7 | 30 | 1,2&3,4:100–800pps/50Hz | 37 |

| Mean | 19.7 | 8.25 | 25.8 | 35 | |

Three animals received bipolar stimulation with amplitude modulated (AM) signals on both apical and basal electrode pairs. Stimuli for K130 were presented on the apical channel for 2 hours each day followed by 2 hours on the basal channel and stepped through four temporally challenging signals (100 pps unmodulated, 300 pps/30 Hz, 500 pps/40 Hz and 800 pps/50 Hz) each presented on 5 consecutive days. This sequence was repeated throughout the chronic stimulation period. K105 and K107 were stimulated on both channels using a carrier rate of 800 pps, sinusoidally amplitude modulated at 20 Hz (K105) or 60 Hz (K107). K84 and K98 received stimulation on a single bipolar channel of the implant from an operational analog CI speech processor (SP in table 2), set at maximum stimulus amplitude of 6 dB above EABR threshold. K76 received monopolar stimulation via a ball electrode positioned on the round window and activated against a distant ground.

2.2. Chronic electrical stimulation

Six 30-day deafened animals were implanted unilaterally in the left cochlea at about 8 weeks of age with a scala tympani electrode containing four wires and activated as two bipolar pairs, comprising two stimulation channels. All the animals received chronic electrical stimulation for 4 hours per day, for an average of 25–26 weeks, using signals considered to be temporally challenging to the central auditory system, as described in previous studies from this laboratory (Vollmer et al., 1999). Specifically, the electrical stimuli were continuous trains of charge-balanced biphasic pulses (200 μsec/phase) delivered at a carrier rate of 325 pps. The pulse trains were amplitude modulated with a sinusoidal envelope of 30 Hz (100% modulation depth) for the apical bipolar pair and 60 Hz (100% modulation depth) for the basal bipolar pair. Stimulation levels were set at 2 dB above electrically evoked ABR thresholds that were assessed every two weeks for each bipolar channel. This protocol of stimulation has been shown to effectively excite central auditory neurons across a broad range of frequencies, with minimum thresholds in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus being systematically lower than final stimulation levels (Leake at al., 2007). Four animals received 28–30 weeks of electrical stimulation; two animals were euthanized after 15–18 weeks of electrical stimulation due to device failure. For evaluation of the effect of electrical stimulation on the cochlear nucleus, data from the implanted side were compared to the non-implanted side in within-subject paired comparisons.

The comparison group consisted of 6 neonatally deafened subjects that were selected from previous studies to have durations of stimulation and age at study matched as closely as possible to the 30-day deafened subjects (Table 2). Several different signals were used for chronic stimulation in this group. Stimulation histories for these neonatally deafened animals have been described in previous publications (Leake et al., 1995; Leake et al., 1999; Osofsky et al., 2001; Leake et al., 2007), and all animals included were considered to have received stimulation that excited the auditory nerve and central auditory system across a broad range of frequencies, equivalent to the 30-day deafened subjects.

2.3. Cochlear Nucleus Histology

At the end of the experiment, the animals were administered an overdose of sodium pentobarbital and transcardiac perfusion was performed with normal saline solution followed by a mixed aldehyde fixative (1.5% glutaraldehyde and 2.5% paraformaldehyde in 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4). The brain was removed from the skull, placed in the same fixative overnight, then transferred into a 40% sucrose solution in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) for at least 72 hours. The caudal midbrain, pons and rostral medulla were separated from the rest of the brain and the right side was marked. Specimens were rapidly frozen with dry ice and sectioned serially on a sliding microtome in the coronal plane at a thickness of 50 μm. The individual sections were mounted on 2% gelatin-coated glass slides, and stained with 0.25% toluidine blue for histological analysis. One animal in the 30-day deafened-stimulated group had been injected with the neuronal tracer Neurobiotin in the basal cochlea for another study, and the brain sections were processed for neurobiotin labeling of projections (Leake et al., 2006) before staining with toluidine-blue for the present analyses.

2.4. Evaluation of CN Volume

Digital images of every third section with a random start were captured using a Zeiss Axioskop 2, a 2.5x objective and a Zeiss AxioCam MRc5 digital camera. The total CN perimeter in every imaged section (excluding cochlear nerve root) was outlined and measured using NIH ImageJ (ver. 1.34N, Bethesda, MD) as illustrated in Figure 1. The total CN volume was calculated by multiplying the total area of the sections measured (ΣA) by section thickness (T=0.05 μm) and sampling step (s=3):

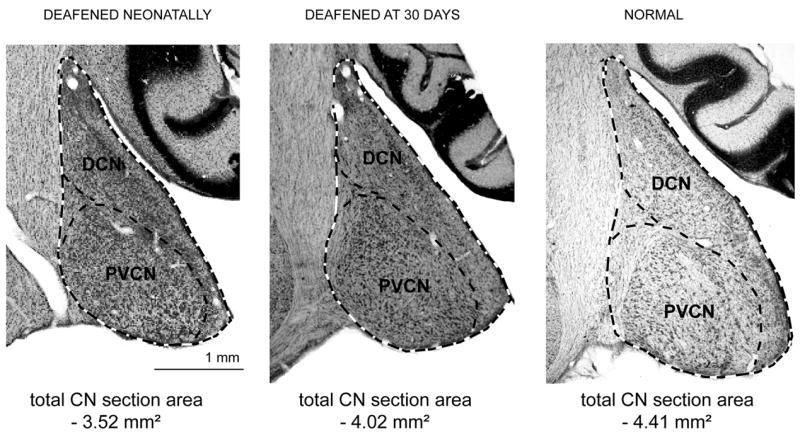

Figure 1.

Coronal sections through the cochlear nucleus taken just posterior to the auditory nerve root are shown from a neonatally deafened animal (left), a 30-day deafened animal (center) and a normal hearing animal (right) examined at 8 weeks of age. Dashed lines illustrate tracings of the perimeter of the CN and its individual subdivisions used to determine cross-sectional areas and volume. (DCN, dorsal cochlear nucleus; PVCN, posteroventral cochlear nucleus.)

Individual CN subdivisions were outlined in each section using the criteria of Kiang et al. (1975). Only the three major CN subdivisions were measured: anteroventral cochlear nucleus (AVCN), dorsal cochlear nucleus (DCN), and posteroventral cochlear nucleus (PVCN). The boundary between the DCN and the PVCN was defined by the intermediate acoustic stria in caudal sections, using the granule cell layer as a landmark in more rostral sections. The interstitial nucleus (IN), where the auditory nerve bifurcates into the AVCN and PVCN, was used to define the boundary between these CN subdivisions. The area ventral to the interstitial nucleus was considered to be part of AVCN and the area dorsal to the interstitial nucleus was considered to be part of PVCN. Caudally, where the IN was not present, the boundary between the AVCN and PVCN was established by cytoarchitectonic criteria (Kiang et al., 1975). All total CN measurements and measurements of individual subdivisions were done with the observer blinded to the experimental manipulations. Images of the right CN were digitally reversed so that the observer was also blinded to side. Measurements were made in both CN, ipsilateral and contralateral to the cochlear implant, of chronically stimulated cats. For deafened groups studied at 8 weeks and normal hearing animals, measurements were made unilaterally.

2.5. Spherical cell cross sectional area measurements

Spherical cells of the rostral AVCN were selected for evaluation of changes in cross-sectional area because they are the primary targets of the cochlear spiral ganglion cells. Moreover, the AVCN demonstrated the greatest deafness-induced changes, and the rostral part of the AVCN contains a relatively homogeneous population of neurons (Osen, 1969; Larsen, 1984). Cells were sampled from the 5th–20th serial sections starting from the rostral pole of the CN. A Zeiss Axioskop 2 and a Zeiss 40x Plan-Apochromat lens with a numerical aperture of 0.95 (optical resolution <1 μm) were used for capturing 1–3 randomly located fields in each section with a final resolution of 11 pixels/μm. The cross-sectional areas of all spherical cells containing a clear nucleus and nucleolus were traced in the images and measured using NIH ImageJ (ver. 1.34N, Bethesda, MD). The areas were calculated directly in the software application after calibration, and measurements were made for a minimum of 100 spherical cells in each CN. Cross-sectional areas of spherical cells from each CN were averaged, and the mean values obtained were then used for comparisons among groups.

2.6. Statistics

Statistical comparisons between the experimental groups were made using analysis of variance (two-way ANOVA, followed by multiple comparisons, Tukey test). In the analysis of CN subdivision volume data, a logarithmic transformation was used to adjust for heterogeneous variances in the data before performing the statistical analysis. Statistical comparisons between the CN ipsilateral (left side) and contralateral (right side) to the implant in a given experimental group were made using two-way repeated measures ANOVA followed by pairwise multiple comparisons (Tukey test). SigmaStat for Windows (version 2.03, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all analyses, and p values below 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

All procedures involving live animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California San Francisco and fully conformed to all NIH guidelines.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Cochlear nucleus volume

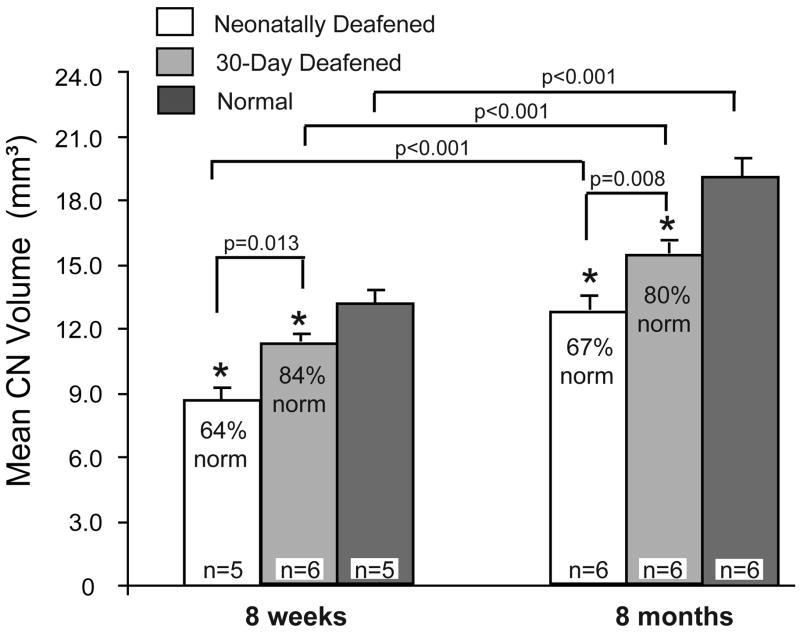

Animals studied at 8 weeks of age (time of implantation)

Figure 1 shows representative coronal histological sections from a neonatally deafened animal, a 30-day deafened animal and a normal hearing animal studied at 8 weeks of age, the age at which other animals received a cochlear implant. Perimeter tracings of the individual CN subdivisions and the total CN area are shown, illustrating the method for estimating volumes. Volume measurements of the total CN (Fig. 2) and of the individual subdivisions (Table 3, 8 weeks of age) were compared for the neonatally deafened, 30-day deafened and normal animals using two-way ANOVA, with onset of deafness and individual subdivision as factors. The data indicated a significant group effect of the brief period of normal auditory development on CN subdivision volumes (p<0.001, no significant interaction). Post-hoc multiple comparisons within each subdivision (Tukey test) showed a significant difference between the neonatally deafened and 30-day deafened groups for the AVCN (p=0.009) and PVCN (p=0.007) volumes, but not for the DCN. Both VCN subdivisions (AVCN and PVCN) exhibited differences of about 20% of normal between the two deafened groups. The DCN volume was about 68% of normal in neonatally deafened animals and 82% of normal in 30-day deafened animals, thus showing a somewhat smaller difference of 14% of normal between the groups. Measurements of the overall CN size in all three groups at this age also showed a significant effect (p=0.004, one-way ANOVA) of the brief period of normal development, with a difference of about 20% between the neonatally and 30-day deafened groups, and with each of deafened groups being significantly smaller than the normal CN (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Mean total CN volumes are shown for all experimental groups. Significant group effects of both the onset (p<0.001) and duration of deafness (p<0.001) on CN development were observed in young animals (two-way ANOVA). The 30-day deafened groups exhibited significantly larger CN volumes than the neonatally deafened groups, both at 8 weeks and 8 months of age (post-hoc comparisons, Tukey test). In turn, normal CN volume was significantly larger than the 30-day deafened and neonatally deafened groups at both ages (asterisks). There was a significant difference in total CN volume (p<0.001) between the 8 week and 8 month old animals in both of the deafened groups, as well as in the normal group. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Table 3.

Mean volume of individual CN subdivisions in neonatally deafened, 30-day deafened and normal animals studied at the ages of 8 weeks and 8 months (ipsilateral and contralateral to the electrically stimulated cochlea).

| Group | AVCN, mm3 mean ±SD |

% of normal |

p-value1 neonatally vs. 30-day deafened |

PVCN, mm3 mean ±SD |

% of normal |

p-value1 neonatally vs. 30-day deafened |

DCN, mm3 mean ±SD |

% of normal |

p-value1 neonatally vs. 30-day deafened |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 weeks of age | |||||||||

| Neonatally deafened (n=5) | 3.79±0.70** | 65% | } 0.009 | 1.86±0.34** | 63% | } 0.007 | 2.96±0.52** | 68% | ns |

| 30-day deafened (n=6) | 4.94±0.51 | 85% | 2.45±0.39 | 83% | 3.54±0.19 | 82% | |||

| Normal, 8 weeks (n=5) | 5.84±0.83 | -- | 2.96±0.24 | -- | 4.34±0.71 | -- | |||

|

| |||||||||

| 8 months of age: Contralateral to the CI | |||||||||

| Neonatally deafened (n=6) | 5.26±0.67** | 57% | } 0.048 | 2.65±0.35** | 67% | } 0.013 | 4.15±0.63** | 74% | ns |

| 30-day deafened (n=6) | 6.36±0.32** | 69% | 3.45±0.38 | 88% | 5.01±0.45 | 89% | |||

|

| |||||||||

| 8 months of age: Ipsilateral to the CI | |||||||||

| Neonatally deafened (n=6) | 5.52±0.93** | 60% | } 0.04 | 2.75±0.38** | 70% | ns (0.06) | 4.47±0.62* | 80% | ns |

| 30-day deafened (n=6) | 6.77±0.91** | 74% | 3.32±0.44 | 84% | 4.98±0.60 | 89% | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Adult normal | |||||||||

| Normal | 9.18±1.61 | -- | 3.93±0.65 | 5.60±0.52 | -- | ||||

P<0.001 for comparisons with age-matched normal animals;

P<0.05 vs. age-matched normal animals; ns – “not significant”, P>0.05

Logarithmic transformation of the data was performed before ANOVA to adjust for heterogeneous variances

A significant group effect of the age at onset of deafness on the volumes of the CN subdivisions was observed in both age groups (two-way ANOVA, p<0.001, no significant interaction). Post-hoc multiple comparisons between 30-day deafened and neonatally deafened groups showed a significant difference in the AVCN and PVCN volumes, but not in the DCN. There was no significant effect of electrical stimulation (CN ipsilateral vs. CN contralateral to the electrically stimulated cochlea, two-repeated measures ANOVA, stimulation and onset of deafness as factors) either in the neonatally deafened (p=0.06 for the group effect of stimulation) or in the 30-day deafened group (p=0.49 for the group effect of stimulation).

Animals studied at 8 months of age (CN ipsilateral to non-implanted ears)

Figure 2 also presents total CN volume data from the older neonatally deafened and 30-day deafened groups (CN ipsilateral to the non-implanted cochlea only) and for the normal hearing group studied at 8 months of age. Two-way ANOVA with onset of deafness and age at study as factors again showed a highly significant effect of onset of deafness (p<0.001), with the CN in the neonatally deafened group being smaller than the CN in the 30-day deafened group, which in turn was significantly smaller than normal.

A significant effect of age at study on the postnatal al growth developmental growth of the CN in the deafened kittens was also shown by statistical comparisons of the 8-week and 8-month old groups (p<0.001). Specifically, CN volume was significantly larger in the 8-month old animals in all three groups, and there was no significant interaction with onset of deafness. Thus, despite the absence of any auditory or direct electrically-evoked input, an increase in total CN volume on the non-implanted side was observed in both deafened groups after an additional 6 months of survival, as compared to the 8 week old animals. Moreover, the effect of 30 days of normal auditory development on CN maturation observed at 8 weeks of age was fairly well maintained after an additional 6 months of survival. That is, CN volumes in the neonatally deafened and 30-day deafened groups maintained similar proportionate values relative to normal at the two ages, indicating that the rate of growth in overall CN volume was similar in the 3 groups.

Data for individual subdivision volumes in the older deafened groups are presented in Table 3. Statistical analysis (two-way ANOVA with onset of deafness and CN subdivisions as factors), indicated a highly significant group effect of the 30 day delay in the onset of deafness on the development of the CN subdivisions (p<0.001, no significant interaction between the factors). Note that the greatest degenerative effects of early deafening clearly occurred in the AVCN. The mean AVCN volume was only 57% of normal in neonatally deafened animals and 69% of normal in 30-day deafened animals at 8 months of age. In contrast, although both PVCN and DCN were also smaller in size than normal, they were less severely affected than AVCN. Comparison of the individual CN subdivision data in normal animals at 8 weeks and 8 months of age showed that AVCN matures later in normal animals (63% of adult size at 8 weeks of age) as compared to PVCN and DCN (75% and 78% of adult size). This may account for the finding that AVCN development was most markedly affected during this period in both deafened groups. Post-hoc multiple comparisons between the neonatally and 30-day deafened groups showed a significant difference in the AVCN and PVCN volumes, but not in the DCN.

3.2. Spherical cell size

Summary data for measurements of cross-sectional areas of spherical cell somata in the AVCN in both deafened and normal groups examined at 8 weeks and 8 months of age (CN contralateral to the implanted cochleae) are presented in Figure 3. Statistical analysis of the differences in mean cell size among the 6 groups (two-way ANOVA with onset of deafness and age at study as factors) showed a significant group effect of onset of deafness (p<0.001) and age at study (p=0.013) with a significant interaction between two factors (p=0.027). Post-hoc comparisons showed that age at study had a significant effect on cell size only in the group of normal animals that exhibited growth of spherical cells equivalent to an increase in area of about 17% of the normal adult value over this period of post-natal development. The lack of a significant effect of age at study in the deafened groups indicates that, unlike the overall CN volume, neither of the deafened groups showed a significant increase in spherical cell size In the CN contralateral to the cochlear implant.

Figure 3.

Mean cross-sectional areas of AVCN spherical cell somata in neonatally deafened, 30-day deafened and normal animals studied at 8 weeks and 8 months of age. Data for the deafened groups at 8 months of age are from the CN on the non-implanted side only. Significant group effects of the onset of deafness (p<0.001) and duration of deafness (p=0.013) on spherical cell size were observed (two-way ANOVA, significant interaction, p=0.027). In the animals studied at 8 weeks of age, cell area in the 30-day deafened group had a tendency to be larger than in the neonatally deafened group, but did not achieve a statistically significant difference from either the neonatally deafened or normal groups in post-hoc multiple comparisons (Tukey test). At 8 months of age, a significant difference in spherical cell size between the 30-day deafened and neonatally deafened groups (data from CN on non-implanted side) was observed (p=0.028), and cells in both groups were significantly smaller than normal (p<0.001). Neither of the deafened groups of animals studied at 8 months of age showed a significant increase in the spherical cell size as compared to the younger (8 week old) animals. In contrast, normal animals exhibited significant growth during this same period, with an increase in mean soma area of about 17% of normal. Asterisks indicate groups that were significantly different from normal animals. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Multiple comparisons (Tukey test) among the 8 week old groups showed that the mean spherical cell size measured in the 30-day deafened group was not significantly different from either the neonatally deafened or normal groups, although the neonatally deafened group was significantly smaller than normal. Comparisons among the 8 month old groups demonstrated a significant effect of the brief period of normal development on the size of the AVCN spherical cell somata, with the 30-day deafened group (data from CN contralatereal to the implanted ear) showing a mean increase in cross-sectional cell area of 17% (363±40 μm2, mean±SD) above cells measured in the neonatally deafened group (CN contralateral to the implant; 311±13 μm2, p=0.028). Spherical cell cross-sectional areas in normal animals averaged 454 μm2 (±40 μm2, SD), and both deafened groups at this age showed significantly smaller spherical cell areas as compared to normal hearing animals (80% of normal for the 30-day deafened and 68% for neonatally deafened animals, p<0.001).

3.3. Effect of electrical stimulation

To evaluate the effect of chronic electrical stimulation delivered by a cochlear implant on CN development, measurements of CN volume and spherical cell size were compared for the left (ipsilateral to the CI) and right (contralateral to the CI) sides in both groups of deafened and chronically stimulated animals. There was no significant difference between the total CN volumes on the implanted and non-implanted sides in either the neonatally deafened group (implanted side, 12.97±0.88 mm3, mean±SD; contralateral CN, 12.67±1.65 mm3; p=0.38), or the 30-day deafened group (implanted side, 15.6±1.50 mm3; contralateral CN, 15.32±0.99 mm3; p=0.35). Similarly, no significant difference between sides was observed in any of the individual subdivision volumes (Table 3), in either deafened group (two-way repeated measures ANOVA with stimulation and CN subdivision as factors). Although absolute values for AVCN showed a 3–4% of normal larger mean volume on the stimulated side in both deafened groups, these differences did not achieve statistical significance, given the large individual variability in the data, and the lack of consistent differences between sides in the other subdivisions.

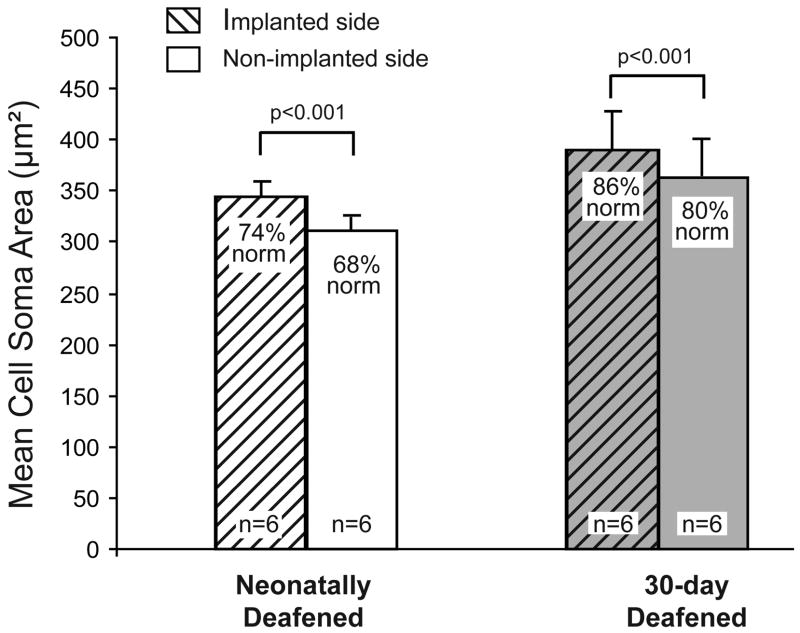

In contrast to the CN volume data, cell measurements in the AVCN ipsilateral to the cochlear implant demonstrated that the cross-sectional areas of the AVCN spherical cell somata were consistently larger after several months of electrical stimulation as compared to the non-implanted side in each individual animal. As summarized in Figure 4, the mean cell soma area ipsilateral to the cochlear implant in the 30-day deafened group was 389 μm2 (±17, SD), a value that was about 7% larger than cells on the contralateral, non-implanted side (363±40 μm2; p<0.001). A similar increase of 8% in spherical cell size was also seen following electrical stimulation in the age-matched neonatally deafened group (337±14 μm2 vs. 311±13 μm2). Two-way repeated measures ANOVA with stimulation and onset of deafness as factors followed by pairwise multiple comparisons (Tukey test) was used for the statistical comparisons in Figure 4; no significant interaction was observed.

Figure 4.

Mean cross-sectional areas of the AVCN spherical cells were significantly larger in the CN ipsilateral to the cochlear implant in both neonatally and 30-day deafened groups (p<0.001, two-way repeated measures ANOVA with stimulation and onset of deafness as factors, no significant interaction). Error bars represent standard deviations.

4. DISCUSSION

4.1. Effect of onset of deafness on the maturation of the cochlear nucleus

Sensorineural hearing loss has been shown to elicit much more profound effects in neonatal animals (Lustig et al., 1994; Saada et al., 1996; Hardie and Shepherd, 1999; Osofsky et al., 2001) than in adults (Born and Rubel, 1985; Hashisaki and Rubel, 1989; Moore et al., 1990; Fleckeisen et al., 1991; Willott et al., 1994; Willott and Bross, 1996; Mostafapour et al., 2000). The reductions in CN volume and neuronal size in animals deafened as adults are solely degenerative processes, because these animals had a mature auditory system at the onset of deafness. In contrast, when ototoxic drug treatment is initiated in neonatal kittens, the CN is only about 20–30% of normal adult size. Thus, the volumes of 60–75% of normal reported in adulthood in these animals reflect a considerable gain in CN volume during this period of maturation, despite the absence of auditory input. In our study, an increase in CN volume of about 20% of normal was observed in both neonatally and 30-day deafened animals studied at 8 months of age as compared to the corresponding younger groups of animals studied at 8 weeks. These data indicate that the CN continued to grow during the subsequent 6 months, suggesting that this period of CN growth, and therefore perhaps the opportunity for reducing pathology with intervention, is fairly prolonged in both animal groups modeling congenital and early acquired profound hearing loss. On the other hand, no significant increase in AVCN spherical cell size was seen in the CN ipsilateral to the non-implanted ears during this time, indicating that the observed growth of the CN is accounted for by growth of the neuropil and not by an increase in soma size of the CN neurons. The growth of the neuropil may be supported by the presence of a substantial population (more than 50%) of spiral ganglion cells in the cochlea that are still present in these animals at 8 weeks of age (Leake et al., 2007). Thus, the CN growth may reflect the development of the remaining spiral ganglion axons projecting via the auditory nerve to the neurons in the CN, whereas at the same time the ongoing degeneration of a portion of the spiral ganglion neural population during this period of maturation results in degeneration of their central connections and the consequent lack of full development of the CN neuropil. The available data do not define precisely when the CN completes this retarded growth in cats, although a previous study showed no significant difference in CN size between groups of neonatally deafened cats at 4 months and 8 months of age (Leake et al., 2006), suggesting that growth is complete by 4 months of age. Delaying neomycin administration by 30 days significantly enhanced growth of the CN in these immature animals and resulted in an overall CN volume of 80% of normal, as compared to a reduction to 67% of normal in age-matched neonatally deafened animals. Further, this brief initial period of normal hearing resulted in spherical cell somatic areas in the AVCN that were 80% of normal (contralateral to the implant) in the 30-day deafened group as compared to 68% of normal for cell areas in neonatally deafened animals. The observed relationship between the extent of CN pathology and onset of deafness suggests that auditory experience is essential for the normal postnatal maturation of the CN and that there is an important sensitive period of development, during which deafness causes irreversible changes in the CN. Deafness, even after postnatal day 30, still prevented full development of the CN and resulted in significant reductions in CN volume and spherical cell size as compared to normal, indicating that this sensitive period extends well beyond the onset of hearing (at least 30 days postnatal in cats).

4.2. Effect of chronic electrical stimulation

Although the maintenance of intact hearing over the first postnatal month in the 30-day deafened group resulted in an increase in the size of the CN in adulthood as compared to neonatally deafened cats, no significant additional benefit was demonstrated in these developing animals when auditory input was replaced by unilateral electrical stimulation delivered by a cochlear implant. Based on the overall CN growth of almost 20% from 8 weeks to 8 months of age in deafened animals, the lack of differences between the 2 sides raises the question of whether unilateral electrical stimulation elicited a bilateral effect on the CN. Electrical stimulation of one cochlea could influence the contralateral CN either through direct commissural connections or via descending inputs from higher auditory centers, and we cannot rule out the possibility that stimulation provided trophic support that contributed to the continued growth of both CN. On the other hand, the central axons of the cochlear spiral ganglion neurons, which form the auditory nerve, directly target cells in the ipsitateral CN and do not project beyond this level. Thus, we initially hypothesized that unilateral intracochlear electrical stimulation would elicit more pronounced effects in the CN ipsilateral to the cochlear implant, especially given the extent of degenerative alterations seen in both CN of neonatally deafened animals in earlier studies.

Another potentially important factor is the efficacy of electrical stimulation in activating the entire CN. Previous electrophysiological recording experiments in neonatally deafened animals have consistently shown that stimulation using identical intracochlear electrodes and stimulation paradigms as applied in this study activate the central auditory system very broadly (Leake et al, 2000; 2007). However, it is still possible that if we were able to accurately determine the CN region(s) receiving strongest activation by the cochlear implant, CN volume (and/or cell size) in that region might exhibit more substantial effects, which are averaged out in our measurements of total volume of the CN and its subdivisions (and of randomly selected cells).

Although stimulation elicited no significant effect on CN volume, spherical cells in the AVCN showed a modest, but significant increase (7–8%) in soma size on the stimulated side, with similar effects observed in both 30-day deafened and neonatally deafened animals. These data are consistent with previous studies showing that electrical stimulation can ameliorate the degenerative effects of profound deafness on cells in the AVCN (Matsushima et al., 1991; Lustig et al., 1994; Osofsky et al., 2001; Ryugo et al., 2005). Moreover, delaying the onset of deafness for 30 days, coupled with subsequent electrical stimulation from the cochlear implant resulted in spherical cell cross-sectional areas that were 86% of normal (ipsilateral to the implant) as compared to 74% of normal for cell areas in neonatally deafened animals. In normal development, Larsen (1984) noted that large spherical cells in the cat AVCN increase rapidly in cross-sectional area during the first month of life, achieving 70% of their normal adult size at about 4–5 weeks of age. Changes in cell ultrastructure, including maturation of postsynaptic densities, intermembranous cisternae and cellular membranes, also occur during the first 30 days postnatal (Ryugo et al., 2006). This period of rapid cell growth is followed by a second, longer period during which cells slowly increase to adult size and synaptic maturation is completed (Larsen, 1984; Ryugo et al., 2006). Thus, electrical stimulation in our study probably was effective in increasing the size of the spherical cells in both neonatally and 30-day deafened cats, because maturation of the spherical cells was incomplete at the time stimulation was introduced. Ryugo et al. (2005) showed that after 3 months of electrical stimulation in congenitally deaf cats, deafness-induced ultrastructural changes in synapses on AVCN spherical cells were reversed, although no data on the size of the spherical cell somata were reported. Their findings suggest that electrical stimulation was able to restore more normal properties of the endbulb synapses, and thus, could also account for the increase in cell size we observed in the present study.

In the limited data available on the CN of human subjects who have undergone cochlear implantation following profound deafness, no significant difference was found in CN volume, maximal cross-sectional area or density of neuronal cell bodies in the AVCN, or in synaptic densities on the cell bodies in the AVCN in comparisons between the CN ipsilateral and contralateral to the cochlear implant (Chao et al., 2002). However, all the subjects in that study suffered adult onset, bilateral deafness and received a unilateral CI within varying times from the onset of hearing loss. We would expect that the pathology in the central auditory pathways (and any effect of electrical stimulation) would be less pronounced than after deafness occurring in infancy. The importance of initial auditory experience has been emphasized in one morphological study of human subjects, in which greater reduction in VCN cell size was observed in individuals with genetic deafness as compared to acquired hearing loss (Moore et al., 1994).

4.3. Clinical implications for pediatric cochlear implants

The finding that even a short period of normal auditory experience provided a significant advantage for enhanced development of the CN may argue for the earliest possible restoration of auditory input in the deafened, developing auditory system. This would presumably provide the best chance for preventing the observed lack of normal development in the cochlear nucleus observed in this study. At the same time, chronic electrical stimulation initiated one to two weeks after deafening in our study was not an adequate substitute for normal auditory input. Stimulation from a unilateral cochlear implant elicited no apparent effect on the overall CN volume, and promoted only a 7–8% increase in spherical cell soma size in the AVCN, which was significantly less than the growth observed in normal age-matched animals (20% increase). The observed increase in size of the AVCN spherical cells also was comparable to the neonatally deafened group despite the fact that 30-day deafened animals had the advantage of normal auditory experience and started electrical stimulation much sooner after the onset of deafness as compared to the neonatally deafened group.

The significant effect of a short period of normal auditory experience on the development of the CN also indicates that the population of CI recipients traditionally called pre-lingually deafened actually may be quite heterogeneous with respect to the maturity of the auditory pathways at the onset of deafness. The human cochlea reaches nearly complete morphological development at about 25 weeks of gestation, when the inner ear attains its maximum size and resembles that of the adult (Anson and Donaldson, 1981). However, the brain stem auditory pathway continues to grow and lengthen postnatally, with portions of the pathway not reaching adult dimensions until the third year of life (Salamy and McKean, 1976; Eggermont, 1983; Fria and Doyle, 1985; Moore et al., 1996). Various pathologies may affect the auditory system at varying times during development and at different stages of maturation in individual children. Because even a short period of normal auditory development significantly reduces deafness-induced degeneration of the auditory system, we can expect different extents of pathology following pre-natal vs. post-natal pre-lingual hearing losses. This difference can contribute, at least in part, to the high degree of variability in language outcomes in CI users. In fact, close to normal speech and language skills were observed in 80% of children who had even a brief period of normal hearing after birth, and received an implant within a year after the onset of deafness (Geers, 2004). Further, lower gap-detection thresholds were observed in children who became deaf at an older age as compared to congenitally deaf children (Busby et al., 1999). The question remains whether the better performance in these studies is related to the brief period of normal hearing or is a result of the shorter duration of deafness before the CI was introduced. Data from our study suggest that the differences we observed between congenitally deafened animals and animals with early-acquired hearing loss cannot be explained by the difference in duration of deafness only. Rather, our findings argue that the brief period of normal postnatal auditory development was primarily responsible for the significantly less severe CN pathology seen in the 30-day deafened group.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant 5R01-DC00160 and Contracts N01-DC-3-1006 and #HHS-N-263-2007-000540C from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders of the National Institutes of Health, and Hearing Research, Inc. The authors gratefully acknowledge the expert technical assistance of Steve Rebscher, who designed and fabricated the custom feline cochlear implants used in this study, and Beth Dwan who assisted in animal surgery, daily stimulation, and care of chronically implanted animals.

- CI

cochlear implant

- CN

cochlear nucleus

- AVCN

anteroventral cochlear nucleus

- DCN

dorsal cochlear nucleus

- PVCN

posteroventral cochlear nucleus

- VCN

ventral cochlear nucleus

- IN

interstitial nucleus

- pps

pulses per second

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Anson BJ, Donaldson JA. Surgical anatomy of the temporal bone. W.B. Saunders Company; 1981. The ear: developmental anatomy; pp. 23–57. [Google Scholar]

- Birnholz JC, Benacerraf BR. The development of human fetal hearing. Science. 1983;222:516–518. doi: 10.1126/science.6623091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Born DE, Rubel EW. Afferent influences on brain stem auditory nuclei in the chicken: neuron number and size following cochlea removal. J Comp Neurol. 1985;231:435–445. doi: 10.1002/cne.902310403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busby PA, Clark GM. Gap detection by early-deafened cochlear-implant subjects. J Acoust Soc Am. 1999;105(3):1841–52. doi: 10.1121/1.426721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao TK, Burgess BJ, Eddington DK, Nadol JB., Jr Morphometric changes in the cochlear nucleus in patients who had undergone cochlear implantation for bilateral profound deafness. Hear Res. 2002;174:196–205. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00694-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CM, Hieber S, Arts HA, Zwolan TA. The education of children with cochlear implants: total or oral communication? Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2000;43:1185–1204. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4305.1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor CM, Craig HK, Raudenbush SW, Heavner K, Zwolan TA. The age at which young deaf children receive cochlear implants and their vocabulary and speech-production growth: is there an added value for early implantation? Ear & Hearing. 2006;27:628–644. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000240640.59205.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggermont JJ. Physiology of the developing auditory system. In: Trehub S, Schneider B, editors. Auditory Development in Infancy. Plenum Press; New York: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Fleckeisen CE, Harrison RV, Mount RJ. Effects of total cochlear haircell loss on integrity of cochlear nucleus. A quantitative study. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1991;489:23–31. doi: 10.3109/00016489109127704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fria TJ, Doyle WJ. Maturation of the auditory brainstem response: additional perspectives. Ear Hear. 1985;5:361–365. doi: 10.1097/00003446-198411000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryauf-Bertschy H, Tyler RS, Kelsay DM, Gantz BJ, Woodworth G. Cochlear implant use by prelingually deafened children: the influence of age at implant and length of device use. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1997;40:183–199. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4001.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geers AE. Speech, language and relating skills after early cochlear implantation. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:634–638. doi: 10.1001/archotol.130.5.634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt KJ, Abrams RM. Fetal exposures to sound and vibroacoustic stimulation. J Perinatol. 2000;20(8 Pt 2):S21–830. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7200446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie NA, Shepherd RK. Sensorineural hearing loss during development: morphological and physiological response of the cochlea and auditory brainstem. Hear Res. 1999;128:147–165. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(98)00209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Rubel EW. Afferent regulation of neuron number in the cochlear nucleus: cellular and molecular analyses of a critical period. Hear Res. 2006;216–217:127–37. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison RV, Gordon KA, Mount RJ. Is there a critical period for cochlear implantation in congenitally deaf children? Analyses of hearing and speech perception performance after implantation. Dev Psychobiol. 2005 Apr;46(3):252–61. doi: 10.1002/dev.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashisaki GT, Rubel EW. Effects of unilateral cochlea removal on anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons in developing gerbils. J Comp Neurol. 1989;283:465–473. doi: 10.1002/cne.902830402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultcrantz M, Snyder RL, Rebscher SJ, Leake PA. Effects of neonatal deafening and chronic intracochlear electrical stimulation on the cochlear nucleus in cats. Hear Res. 1991;54:272–280. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90121-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang NY, Godfrey DA, Norris BE, Moxon SE. A block model of the cat cochlear nucleus. J Comp Neurol. 1975;162:221–24. doi: 10.1002/cne.901620205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk KI, Miyamoto RT, Ying E, Lento C, O’Neill T, Fears F. Effects of age at implantation in young children. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 2002;189:69–73. doi: 10.1177/00034894021110s515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen SA. Postnatal maturation of the cat cochlear nuclear complex. Acta otolaryngologica. 1984;(Supplement 417):1–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Snyder RL, Hradek GT, Rebscher SJ. Consequences of chronic extracochlear electrical stimulation in neonatally deafened cats. Hear Res. 1995;82(1):65–80. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00167-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Kuntz AL, Moore CM, Chambers PL. Cochlear pathology induced by aminoglycoside ototoxicity during postnatal maturation in cats. Hear Res. 1997;113:117–132. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(97)00133-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Hradek GT, Snyder RL. Chronic electrical stimulation by a cochlear implant promotes survival of spiral ganglion neurons in neonatally deafened cats. J Comp Neurol. 1999;412:543–562. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19991004)412:4<543::aid-cne1>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Snyder RL, Rebscher SJ, Moore CM, Vollmer M. Plasticity in central representations in the inferior colliculus induced by chronic single-vs. two-channel electrical stimulation by a cochlear implant after neonatal deafness. Hear Res. 2000;147(1–2):221–241. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Hradek GT, Chair L, Snyder RL. Neonatal deafness results in degraded topographic specificity of auditory nerve projections to the cochlear nucleus in cats. J Comp Neurol. 2006 2006 Jul 1;497(1):13–31. doi: 10.1002/cne.20968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leake PA, Hradek GT, Vollmer M, Rebscher SJ. Neurotrophic effects of GM1 ganglioside and electrical stimulation on cochlear spiral ganglion neurons in cats deafened as neonates. J Comp Neurol. 2007;501:837–853. doi: 10.1002/cne.21275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lustig LR, Leake PA, Snyder RL, Rebscher SJ. Changes in the cat cochlear nucleus following neonatal deafening and chronic intracochlear electrical stimulation. Hear Res. 1994;74:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90173-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manrique M, Cervera-Paz FJ, Huarte A, Perez N, Molina M, Garcia-Tapia R. Cerebral auditory plasticity and cochlear implants. Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology. 1999;49(Suppl 1):S193–S197. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(99)00159-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima JI, Shepherd RK, Seldon HL, Xu SA, Clark GM. Electrical stimulation of the auditory nerve in deaf kittens: effects on cochlear nucleus morphology. Hear Res. 1991;56:133–142. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90162-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR. Auditory brainstem of the ferret: early cessation of developmental sensitivity of neurons in the cochlear nucleus to removal of the cochlea. J Comp Neurol. 1990;302(4):810–823. doi: 10.1002/cne.903020412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR, Rogers NJ, O’Leary SJ. Loss of cochlear nucleus neurons following aminoglycoside antibiotics or cochlear removal. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1998;107(4):337–343. doi: 10.1177/000348949810700413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK, Niparko JK, Miller M, Linthicum F. Effect of profound deafness on a central auditory nucleus. Am J Otol. 1994;15:588–595. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JK, Ponton CW, Eggermont JJ, Wu BJ, Huang JQ. Perinatal maturation of the auditory brain stem response: changes in path length and conduction velocity. Ear Hear. 1996 1996 Oct;17(5):411–8. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199610000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mostafapour SP, Cochran SL, Del Puerto NM, Rubel EW. Patterns of cell death in mouse anteroventral cochlear nucleus neurons after unilateral cochlea removal. J Comp Neurol. 2000;426:561–571. doi: 10.1002/1096-9861(20001030)426:4<561::aid-cne5>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas JG, Geers AE. Effects of early auditory experience on the spoken language of deaf children at 3 years of age. Ear Hear. 2006;27(3):286–98. doi: 10.1097/01.aud.0000215973.76912.c6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niparko JK, Finger PA. Cochlear nucleus cell size changes in the dalmatian: model of congenital deafness. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(97)70179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osen KK. Cytoarchitecture of the cochlear nuclei in the cat. J Comp Neurol. 1969;136:453–484. doi: 10.1002/cne.901360407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osofsky MR, Moore CM, Leake PA. Does exogenous GM1 ganglioside enhance the effects of electrical stimulation in ameliorating degeneration after neonatal deafness? Hearing Research. 2001;159:23–35. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EW, Fritzsch B. Auditory system development: primary auditory neurons and their targets. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2002;25:51–101. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.25.112701.142849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo DK, Kretzmer EA, Niparko JK. Restoration of auditory nerve synapses in cats by cochlear implants. Science. 2005 Dec 2;310(5753):1490–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1119419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryugo DK, Montey KL, Wright AL, Bennett ML, Pongstaporn T. Postnatal development of a large auditory nerve terminal: the endbulb of Held in cats. Hearing Research. 2006;216–217:100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saada AA, Niparko JK, Ryugo DK. Morphological changes in the cochlear nucleus of congenitally deaf white cats. Brain Res. 1996;736:315–328. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(96)00719-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salamy A, McKean C. Postnatal development of human brainstem potentials during the first year of life. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1976;40:418–26. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(76)90193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svirsky MA, Teoh SW, Neuburger H. Development of language and speech perception in congenitally, profoundly deaf children as a function of age at cochlear implantation. Audiol Neurootol. 2004 Jul–Aug;9(4):224–233. doi: 10.1159/000078392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tierney TS, Russell FA, Moore DR. Susceptibility of developing cochlear nucleus neurons to deafferentation-induced death abruptly ends just before the onset of hearing. J Comp Neurol. 1997;378(2):295–306. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19970210)378:2<295::aid-cne11>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin BJ, Barker BA, Spencer LJ, Zhang X, Gantz BJ. The effect of age at cochlear implant initial stimulation on expressive language growth in infants and toddlers. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 2005;48:853–867. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/059). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trune DR. Influence of neonatal cochlear removal on the development of mouse cochlear nucleus: I. Number, size, and density of its neurons. J Comp Neurol. 1982;209(4):409–24. doi: 10.1002/cne.902090410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tye-Murray N, Spencer L, Woodworth G. Acquisition of speech by children who have prolonged cochlear implant experience. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research. 1995;38:327–337. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3802.327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmer M, Snyder RL, Leake PA, Beitel RE, Moore CM, Rebscher SJ. Temporal properties of chronic electrical stimulation determine temporal resolution of neurons in cat inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2883–2902. doi: 10.1152/jn.1999.82.6.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner LA, Gray L. Hearing Development. In: Rubel EW, Popper AN, Fay RR, editors. Development of the auditory system. Springer; 1998. pp. 12–79. [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF, Bross LS, McFadden SL. Morphology of the cochlear nucleus in CBA/J mice with chronic, severe sensorineural cochlear pathology induced during adulthood. Hear Res. 1994;74(1–2):1–21. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)90171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willott JF, Bross LF. Morphological changes in the anteroventral cochlear nucleus that accompany sensorineural hearing loss in DBA/2J and C57BL/6J mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1996;26; 91(2):218–26. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]