Abstract

The rare genetic disorder Fanconi anemia, caused by a deficiency in any of at least thirteen identified genes, is characterized by cellular sensitivity to DNA interstrand crosslinks and genome instability. The excision repair cross complementing protein, ERCC1, first identified as a participant in nucleotide excision repair, appears to also act in crosslink repair, possibly in incision and at a later stage. We have investigated the relationship of ERCC1 to the Fanconi anemia pathway, using depletion of ERCC1 by siRNA in transformed normal human fibroblasts and fibroblasts from Fanconi anemia patients. We find that depletion of ERCC1 does not hinder formation of double strand breaks in crosslink repair as indexed by γH2AX. However, the monoubiquitination of FANCD2 protein in response to MMC treatment is decreased and the localization of FANCD2 to nuclear foci is eliminated. Arrest of DNA replication by hydroxyurea, producing double strand breaks without crosslinks, also requires ERRC1 for FANCD2 localization to nuclear foci. Our results support a role for ERCC1 after creation of a double strand break for full activation of the Fanconi anemia pathway.

Keywords: Fanconi anemia, interstrand crosslink, ERCC1, double-strand break

INTRODUCTION

Interstrand cross-linking (ICL) agents are widely used in chemotherapy due to their potent toxicity to cycling cells. Cell death is thought to be due to the covalent linkage formed between the strands of DNA, preventing separation required for normal DNA processing and thereby stalling replication [1]. In E. coli the ICL repair response utilizes nucleotide excision repair (NER) and homologous recombination (HR) [2]. In the absence of a homologous sequence, it appears DNA polymerase II may perform translesion synthesis across the gap created by the initial incision by UvrABC [3]. Genetic evidence indicates there are three separate non-overlapping, non-epistatic ICL repair pathways in S. cerevisiae: NER, post-replication repair, and HR represented prototypically by SNM1, REV3, and RAD51 for each of the sets of multiple genes involved [4]. That is, a defect in any one of the pathways is additive to a defect in another regarding ICL repair. SNM1 is taken to represent the NER pathway although mutants are not sensitive to ultraviolet radiation (UV); it is non-epistatic to RAD51 or REV3.

Evidence suggests that in yeast, early in ICL repair, a double strand break (DSB) is formed as an intermediate, and it is repair of this DSB that is the function of later steps in the ICL repair pathway [4,5]. The mammalian ICL repair response also may utilize NER, post-replication repair, and HR pathways [3,6-9]. Additionally, the Fanconi anemia (FA) pathway has been implicated in the repair of ICLs, based on the sensitivity of FA patients' cells to ICLs [7,10]. Model organisms from C. elegans to mice share a portion to the entirety of this pathway with humans [11-14].

Fanconi anemia is a rare genetic disorder presenting with a phenotype that is quite variable; patients exhibit short stature and other skeletal abnormalities, skin pigmentation abnormalities, bone marrow failure leading to anemia and leukemia, increased risk of solid tumors, and exquisite cellular sensitivity to ICL-inducing agents [15,16]. There are at least thirteen genes acting in the pathway [17,18]. Central to the FA pathway are FANCD2 and its recently characterized partner, FANCI, acting as the ID complex [19]. Both are monoubiquitinated in a core complex-dependent manner, and their monoubiquitination and deubiquitination seem to be coordinately regulated [19].

Among mammalian NER proteins, loss of either ERCC1 or XPF (which form a heterodimer) leads to markedly increased ICL sensitivity [3,9,20,21]. In addition to their function in excision of bulky adducts in NER, ERCC1/XPF are also thought to trim overhanging non-homologous single-stranded DNA from homologous recombination intermediates to facilitate extension of the recombination intermediate [22-24]. The ERCC1/XPF dimer possesses endonucleolytic activity which can incise at an ICL, as determined by using model substrates and mutant lines [25-27]. The Mus81-Eme1 dyad also can cleave at the site of ICL formation [28]. Thus there is evidence, based on enzyme activity and cell lines, that several mammalian enzymes might be involved in converting an ICL to a DSB in the process of repair.

Conclusions differ as to the role of ERCC1 in ICL repair. ERCC1 was implicated in the initial incision of ICLs, based on comet assay following treatment with psoralen-UVA. In addition, reduced formation of γH2AX foci, as a marker of DSBs, was observed in S-phase in ERCC1−/− Chinese hamster ovary cells (CHO) as compared to controls [29]. However, no significant difference in γH2AX foci (an index of DSBs) between ERCC1−/− murine mutant and control cells was found by others [24]. The observed persistence of γH2AX foci in the mutant cells suggested that ERCC1 might be required for the resolution of DSBs in response to ICLs. That would indicate actions of ERCC1 are required after an initial incision event and ‘downstream’ from DSB formation. Thus there are several possible interpretations of the different outcomes reported [30] The precise function of ERCC1 in ICL repair remains uncertain, leaving open the possibility of action at more than one step in the process.

In order to evaluate the role of ERCC1 in ICL repair and determine the relation of ERCC1 to FA, we chose the system of depletion of ERCC1 by siRNA in transformed human fibroblasts and examined a time-course of γH2AX phosphorylation and focus formation after ICL formation. Additionally, we examined FANCD2 monoubiquitination (FANCD2-Ub) and FANCD2 focus formation in parallel, to clarify the roles of γH2AX phosphorylation, ERCC1/XPF and FANCD2-Ub in the repair of ICLs. We also used hydroxyurea (HU) to arrest DNA replication to determine whether ERCC1 acts in the response to DSBs arising from stalled replication forks without ICLs.

With this approach we find that γH2AX phosphorylation and focus formation in response to MMC- or DEB-induced ICL or HU treatment are not significantly reduced when ERCC1 is depleted. However, following ERCC1 depletion, FANCD2-Ub formation is reduced and FANCD2 foci are eliminated. The same findings occur with HU treatment. We conclude that ERCC1 is not required for DSB formation in response to ICLs, but is required after DSB formation in order to optimally activate the FA pathway. Such a role for ERCC1 is not limited to the repair of ICLs, but is also required to process DSBs resulting from HU treatment, where no crosslink is present. This provides evidence that the basis for sensitivity of ERCC1/XPF-deficient cells to ICLs is in a processing step after incision.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell Culture

GM639, an SV-40 transformed normal human fibroblast cell line (NIGMS Human Genetic Mutant Human Cell Repository, Camden, NJ), was cultured in αMEM (Mediatech, Herndon, VA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Hyclone, Logan, UT) at 37°C with 5% CO2. GM6914, an immortalized FANCA patient fibroblast line, and PD20, an immortalized FANCD2 patient fibroblast line were similarly maintained. Cultures were serially passaged two to three times weekly with frozen stocks freshly thawed at least monthly to keep passage numbers low.

ERCC1 or FANCA was depleted using an siGENOME siRNA smartpool (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO). CypB siCONTROL siRNA (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) was used as a control. T-25 flasks (Falcon/Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were seeded with 5×104 cells 12−16 hours prior to siRNA transfection. 7.5μL 20μM siRNA was mixed with 166.5μL OptiMEM (Invotroen-GIBCO Carlsbad, CA) and 3μL oligofectamine (Invotrogen, Carlsbad, CA) was mixed with 12μl OptiMEM for each flask to be transfected. These mixes were incubated at room temperature for 5 minutes, combined, and incubated for an additional 10 minutes. The medium from each T-25 flask was aspirated and washed with OptiMEM. 0.8mL of OptiMEM was added to each flask, followed by the addition, drop-wise, of the transfection mixture. Following a 4hr incubation at 37° with 5% CO2, 0.5mL αMEM containing 30% FBS was added. Approximately 16hr later, the medium was replaced with αMEM containing 10% FBS.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Following depletion, cells were harvested, washed with PBS, then re-suspended in 0.5ml PBS. Cells were fixed by adding 4.5ml 70% ethanol drop-wise while vortexing, then stored at 4°C overnight. Cells were washed with PBS, then re-suspended in propidium iodide (PI) solution (50μg/mL PI (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 0.5mg/ml RNase A (Invitrogen-Gibco, Carlsbad, CA)) and stained for at least 1hr at room temperature. Fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis was then performed on a FACSCalibur (BD Bioscience, San Jose, CA).

Immunoblotting

48hr after transfection, flasks were treated with a one hour pulse of 500ng/mL MMC (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), 300ng/mL DEB (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or 3mM HU (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or harvested by trypsinization (Invitrogen-Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) as untreated controls. Treated cells were washed once with PBS and αMEM with 10% FBS was added. Flasks were harvested by trypsinization at 1, 2, 4, 6, and 8hr, and these cell pellets were stored at −80°C until used.

Lysates were prepared by re-suspending the cell pellets with cold RIPA lysis buffer. Samples were then disrupted on ice for 10sec using a sonicator (Heat Systems-Ultrasonics, now known as Misonix, Inc., Farmingdale, NY) set at the microprobe maximum. Protein levels were quantitated and equalized for loading using the RIPA lysis buffer. 4X LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) were added to 1X and 5%, respectively. Samples were then placed in boiling water for 5min and quickly centrifuged.

Samples for FANCD2 immunoblotting were loaded on a 10 well Novex 3−8% Tris-acetate gel (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) that had been pre-run for 7min at 100V. These gels were run for 8−9hr at 110V in Tris-acetate running buffer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Transfer to a 0.2μm pore supported nitrocellulose Optitran membrane (Whatman, Brentford, □Middlesex, UK) was performed in Towbin buffer [50mM Tris (Fisher Bioreagents, Fair Lawn NJ), 380mM glycine (MP Biomedicals, Solon, OH)] at 25V overnight at 4°C. All subsequent steps were performed on an orbital shaker at 100rpm. Membranes were blocked for 1hr with TBS with 0.2% tween-20 and 5% powdered, non-fat milk (block), probed with mouse anti-FANCD2 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:1000 in block for 1hr, washed three times for 5min with TBST containing 0.2% tween-20, probed with goat anti-mouse HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:1000 in block, and the washes were repeated. Blots were then immersed in Imobilon Western HRP Substrate (Millipore, Billerica, MA) for 5min and placed against film.

Samples for γH2AX immunoblotting were loaded onto a 15% acrylamide:bis 29:1 (BioRad, Hercules, CA) with a 4% stacking gel and run at 110V for approximately 2hr in Towbin buffer containing 0.5% SDS. Transfer to a 0.2μm pore supported nitrocellulose Optitran membrane was performed in Towbin buffer at 70V for 1hr at 4°C. All subsequent steps were performed on an orbital shaker at 100rpm. Membranes were blocked for 1hr in TBST with 0.2% tween-20 and 5% BSA, probed with rabbit anti-γH2AX antibody (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) at 1:1000 in block for 1hr, washed 3×5min in block, probed with goat anti-rabbit HRP conjugated secondary antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:1000 in block for 1hr, and the washes were then repeated. Blots were then immersed in Imobilon Western HRP Substrate for 5min and placed against film.

Samples for ERCC1 or FANCA immunoblotting were loaded onto a 10% acrylamide:bis with a 4% stacking gel and run at 110V for approximately 2hr in Towbin buffer containing 0.5% SDS. Transfer to a 0.2μm pore supported nitrocellulose Optitran membrane was performed in Towbin buffer at 70V for 1hr at 4°C. All subsequent steps were performed as with the FANCD2 immunoblots, using mouse anti-ERCC1 monoclonal antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 1:1000 and goat anti-mouse HRP conjugated secondary antibody at 1:1000.

Immunofluorescence

24hr after transfection, flasks were trypsinized and the cells were transferred to 4-well CultureSlides (BD Falcon, San Jose, CA) adding 5,000 cells, counted by Neubauer hemocytometer, per well in 500μL αMEM 10% FBS. 24hr later the chambers were treated as the flasks were for immunoblotting. 4hr post-treatment, the cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS for 15min on a laboratory tipper as with all subsequent steps. Cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton-X 100 (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in PBS for 15 minutes, followed by blocking with 15%FBS in PBS for 1hr. Primary antibody was then added for 1hr at room temperature. For γH2AX foci, rabbit anti-γH2AX was added at 1:2500 in block, and for the FANCD2 foci, rabbit anti-FANCD2 (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO) was added at 1:400 in block. Slides were then washed 3×5 minutes with 0.2% tween-20 in PBS. Alexa fluor 594 donkey anti-rabbit (Invitrogen-Molecular Probes Eugene, OR) was then added 1:750 in block for 1hr at room temperature. Washes were repeated, followed by addition of ProLong Gold antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and application of a coverslip. The following day after curing, the coverslips were fixed to the slide and the samples were examined by fluorescent microscopy.

Densitometry

Immunoblot films were scanned on a Canon Pixmatm MP170 (Canon USA, Lake Success, NY) into TIFF format. Files were cropped, inverted and edited for levels to lower background using Pixelmator (version 1.1.3, Pixelmator Team, Ltd.). Images were exported to PGM format and imported into ImageJ (version 1.38, NIH). Lanes were defined using the rectangle selector tool and then plotted. The area under the curve was integrated and then ratios determined as needed.

Cell Survival after Clastogen Treatment

48hr post-transfection, cells were trypsinized and 300 cells were transferred to each 100mm dish (Falcon/Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) containing αMEM with 10% FBS. MMC and DEB were added at doses of 0, 5, 10, 20 and 40 ng/mL and 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 μM respectively. Each concentration was tested in triplicate. After 10 days, plates were stained with new methylene blue (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) in 70% ethanol. Colonies were counted and percentages of untreated colonies were calculated, correcting for plating efficiency.

Chromosome Stability

24 hours after siRNA transfection, flasks were left as untreated controls or treated with the appropriate dose of MMC or DEB. The dose was 30−40 ng/ml MMC for GM639, 5−10 ng/ml for FANC cell lines PD20 (FANCD2) or GM6914 (FANCA), or for cells depleted in either of those proteins, and 30ng/ml for GM639 cells depleted for ERCC1. After 24−28 hours, colcemid (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to a final concentration of 150ng/mL. Approximately 3hr later, cells were trypsinized, suspended in 75mM KCl, and fixed with 3:1 methanol:acetic acid and 75mM KCl. Slides were stained with Wright's stain (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA). Nuclei and metaphases were assessed qualitatively for mitotic index to confirm there was no significant difference between the variously treated samples. 50 metaphase spreads or more per sample were routinely assessed for radial formation using a Nikon Eclipse E800tm microphotoscope and captured using CytoVision software (Applied Imaging, San Jose, CA). Percent radials refers to the percent of cells with one or more radial form.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Prism 4.0 for Macintosh (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). For comparison of nuclei considered positive or negative for foci and cytogenetic analysis of radial data under different experimental conditions, a Mann-Whitney test was utilized with a confidence interval of 95% and a two-tailed P value which was considered to be of significance if P >0.05. Western blot densitometry is plotted with bars showing the mean value and error bars representing the standard deviation.

RESULTS

ERCC1 Depletion Produces MMC Sensitivity in Human Fibroblasts

To study the role of ERCC1 in the FA pathway, we adopted the strategy of siRNA depletion in human cells. Immunoblotting of depleted and control lysates was routinely done in order to demonstrate depletion of ERCC1 protein. The immunoblots typically demonstrated a depletion measuring approximately 90% (see, for example, Figure 3).

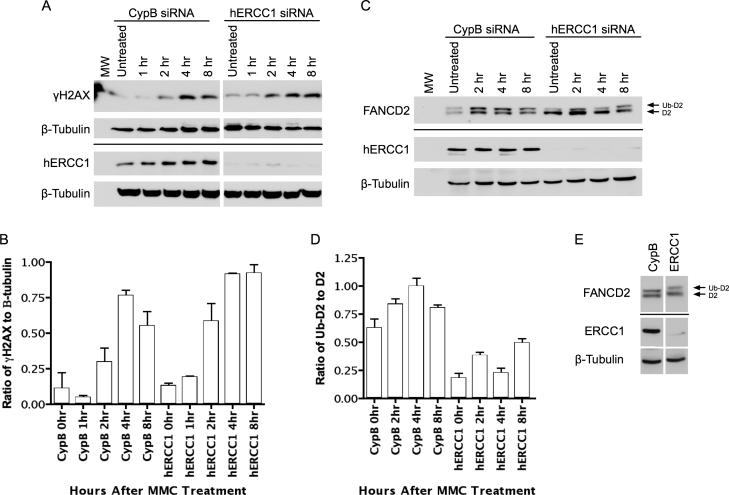

Figure 3. FANCD2-Ub and γH2AX formation with time after MMC.

A. γH2AX immunoblot with time after MMC, as in Methods, and either control siRNA or ERCC1-depleted, with β-tubulin as a loading control. Cells were treated with MMC for one hour, then washed free. B. Densitometry of the immunoblot in Figure 3A. The ratio of intensity of the γH2AX bands relative to the loading control β-tubulin bands is shown. Densitometry measurements were performed in triplicate and the error bars represent the standard deviation of these measurements. C. FANCD2 immunoblot with time after MMC treatment. D. Densitometry of the immunoblot in Figure 3C. Densitometry measurements were performed in triplicate and the error bars represent the standard deviation of these measurements. E. FANCD2 immunoblot at 4 hours after HU, as in Methods. In panels A C, and E, space between blots denotes different sections of the same membrane, a line between blots indicates different membranes blotted from the same gel.

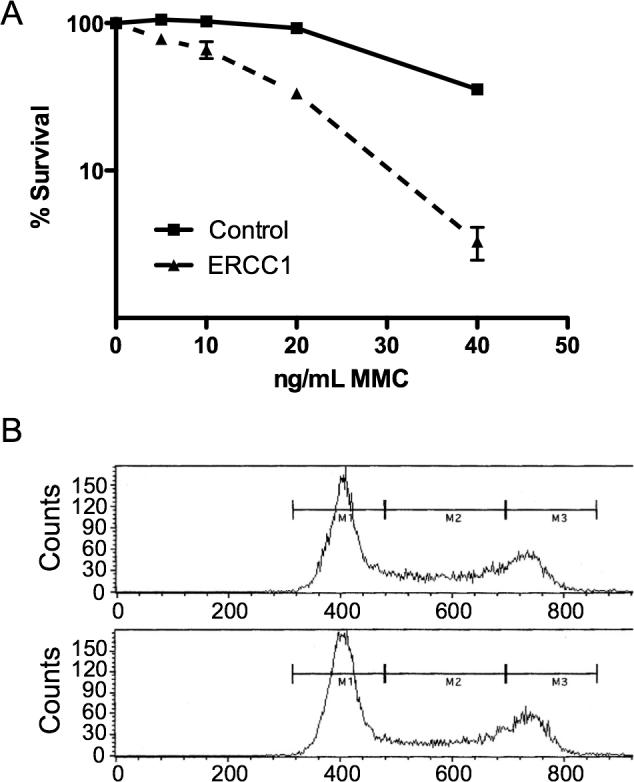

Sensitivity to ICLs has been reported with lack of ERCC1 function [23,24,29]. Sensitivity of cells depleted for ERCC1 was determined using a colony-forming assay with increasing doses of MMC or DEB. The MMC LD50 of the control depletion was approximately 4-fold greater than with ERCC1 depletion (Figure 1A). DEB sensitivity was similarly increased with ERCC1 depletion (data not shown). The increased sensitivity indicated that the ERCC1 depletion was effective and affected survival in response to ICL formation.

Figure 1. ERCC1 Depletion.

A. Survival curve with MMC treatment in transformed normal human fibroblasts, with or without ERCC1 depletion. B. Representative cell cycle analysis of ERCC1-depleted (top panel) and control cells (bottom panel).

It appears that DSBs cause a prolonged G2/M checkpoint arrest and that the DSB resulting from an ICL occurs in S-phase [24,29]. A change in the percentage of cells in S-phase, resulting from ERCC1 depletion, therefore might affect survival or exaggerate or mask changes in γH2AX phosphorylation and FANCD2 monoubiquitination levels. We evaluated whether the cell cycle was altered with ERCC1 depletion using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). The ERCC1-depleted cell culture (Figure 1B, top panel) contained approximately 24% of cells in the M2 fraction and the control culture (Figure 1B, bottom panel) contained approximately 27% cells in the M2 fraction, demonstrating there was no significant change in the proportion of cells in S-phase.

FANCD2 Foci Are Eliminated with ERCC1 Depletion

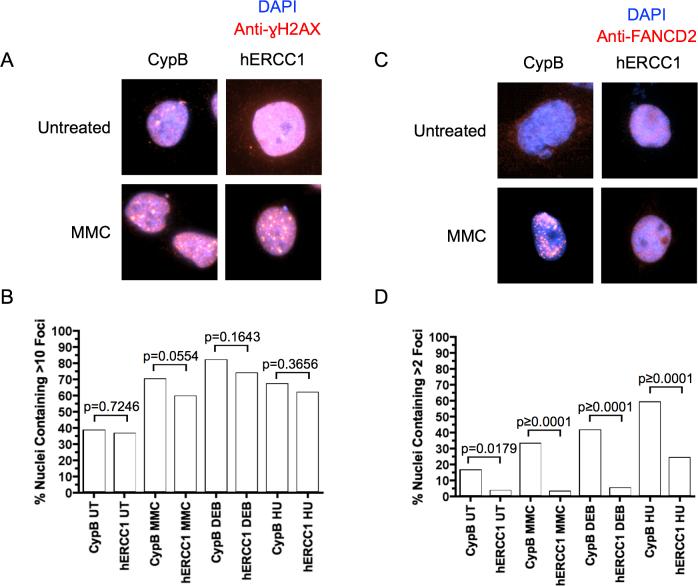

γH2AX foci are used as a marker for DSBs [31,32], while FANCD2 nuclear foci are markers of activation of the FA pathway, dependent on formation of FANCD2-Ub which is required for localization to chromatin [10,33]. γH2AX localizes to the region of a double strand break and perhaps acts to recruit other DNA repair proteins. Evidence functionally links γH2AX with BRCA1-dependent recruitment of FANCD2 to foci [34]. To monitor focus formation, cells were cultured in chamber slides and then either treated, or not, with MMC, DEB, or HU. Slides were then processed for immunofluorescence of γH2AX or FANCD2.

A cutoff of 10 foci per cell was used to differentiate γH2AX focus-positive versus focus-negative nuclei, as the GM639 cells normally had several foci per nucleus under control conditions. γH2AX focus-positive nuclei were observed in an increased number of cells with all clastogen treatments (Figure 2A and B), but there was no significant difference between control and ERCC1-depleted lines with or without MMC treatment (Figure 2B). This indicates ERCC1 is not essential for formation of DSBs in response to MMC, DEB, or HU, as indexed by γH2AX, nor necessary for γH2AX focus formation. The increase in γH2AX foci after treatment was mirrored in the HU sample, which did not have crosslinks, since HU causes double strand breaks by replication arrest.

Figure 2. γH2AX and FANCD2 foci.

A. γH2AX foci with or without MMC treatment in GM639 cells. B. Quantification of γH2AX foci formation observed in untreated (UT), MMC-, DEB- or HU-treated GM639 cells, with control versus ERCC1 depletion (n=200 nuclei observed). C. FANCD2 foci with or without MMC treatment in GM639 cells. D. Quantification of FANCD2 foci formation in untreated, MMC-, DEB- or HU-treated GM639 cells, with control versus ERCC1 depletion with CypB siRNA as the control (n=200 nuclei).

We also investigated FANCD2 focus formation, using a cutoff for the FANCD2 immunofluorescence of 2 foci per nucleus to be considered FANCD2 focus-positive. As expected, the control cells demonstrated an increase in FANCD2 foci in response to MMC, DEB or HU treatment (Figure 2C and D). In contrast, the ERCC1-depleted cells showed essentially background level FANCD2-foci after DNA damage or in controls (Figure 2D). This demonstrates a requirement for ERCC1 in the formation of FANCD2 foci in response to MMC, DEB or HU, in contrast to formation of γH2AX foci. With ERCC1 depletion there is less than a two-fold increase in FANCD2 focus formation in response to HU, compared to an untreated control (Figure 2D), whereas there is a fourfold increase in the control. While HU does not form ICLs, it does form DSBs secondary to replication arrest, and is an efficient inducer of FANCD2-Ub. The findings raise the possibility that ERCC1 is required for processing of the DSB to a structure required for FANCD2-Ub to localize to foci, but that the DSB resulting from HU is a conformation permitting only a slight recruitment of FANCD2 to foci. These results place ERCC1 action after γH2AX focus formation, but before FANCD2 focus formation, both in response to ICL- and HU-induced DSBs.

FANCD2 Monoubiquitination is Reduced with ERCC1 Depletion

Immunoblotting against γH2AX and FANCD2 were done to quantify the immunofluorescence data by a second technique and determine if the failure to form FANCD2 foci was the result of a failure of FANCD2-Ub formation over time. To confirm the depletion of ERCC1, immunoblots were performed on all samples. In all ERCC1 siRNA-treated samples, the depletion of ERCC1 was satisfactory (Figure 3A and C), indicating a functional knockdown throughout the time-points examined.

A time-course following MMC treatment of cells was done to evaluate the formation of γH2AX and FANCD2-Ub in the absence of ERCC1. γH2AX immunoblotting confirmed the results of the γH2AX focus formation. Control and ERCC1-depleted cells had similar levels of γH2AX at 1, 2, and 4hr in response to MMC (Figure 3A and B). At 8 hours it appeared that the ERCC1-depleted sample retained a higher level of γH2AX. This may be indicative of delayed ICL repair and is consistent with previous observations of a prolonged increase in γH2AX in ERCC1 defective cells [24,29].

Parallel FANCD2 immunoblots were done with the same lysates. The ratio of FANCD2-Ub to the unmodified form reflects a molecular signal of activation of the FA pathway [10]. Freely cycling cells manifest some FANCD2-Ub at all times, increasing in S-phase. FANCD2 immunoblots of ERCC1-depleted cells harvested after treatment with MMC showed a small increase in FANCD2-Ub with time, compared to controls (Figure 3C and D). In separate trials this was confirmed; ERCC1-depleted cells had significantly lower values for FANCD2-Ub relative to total FANCD2. At zero time after MMC treatment it was 20% compared to 31% in non-depleted cells, as seen in Figure 3. The lower relative amount of FANCD2-Ub in depleted cells compared to non-depleted cells persisted throughout the time course after MMC exposure, with 25% versus 35% at four hours and 31% versus 41% at eight hours for depleted versus non-depleted respectively (from a best-fit regression line, averaging three separate trials). Thus at all the times after MMC treatment ERCC1-depleted cells had significantly lower FANCD2-Ub. These results confirm ERCC1 is utilized in activation of the FA pathway.

Interestingly, the results were mirrored with HU treatment (FANCD2-Ub 28% in depleted versus 38% in control at four hours, Figure 3E) and DEB (data not shown). This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that monoubiquitination is required for localization of FANCD2 to chromatin. However, the lack of FANCD2 focus formation is considerably greater with ERCC1 depletion than the lack of FANCD2-Ub formation, suggesting ERCC1 may play a direct role in enabling focus formation.

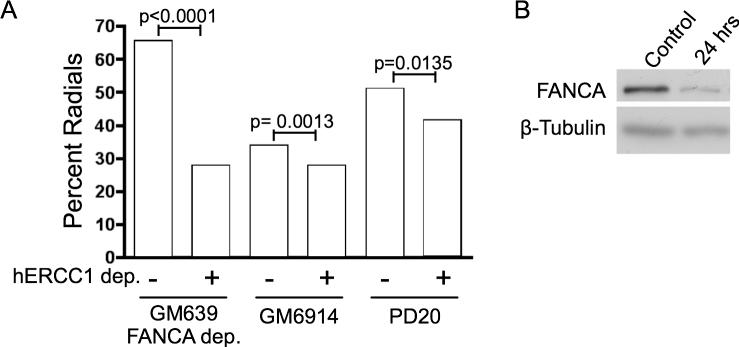

Radial Formation in Fanconi Cells is Reduced with ERCC1 Depletion

Radial formation after treatment of cells with ICL agents is a hallmark of FA [16,35]. Deficiencies or depletions for several other genes related to DNA repair have also been shown to increase radial formation after ICLs, including BRCA1 and BRCA2 [36], so it is a non-specific response. Lack of ERCC1 also has been reported to cause radial formation [24]. To examine the role of ERCC1 in the FA pathway, as it relates to radial formation, we depleted ERCC1 in FANCA-depleted GM639, and in FANCA and FANCD2 cell lines.

We have observed a modest increase in radial formation in normal human transformed fibroblasts depleted for ERCC1 after MMC treatment [37]. This is in agreement with observations in Chinese hamster cells and rodent ES cells [24]. We investigated whether FA cells or cells depleted for FANCA protein show a similar response to MMC when ERCC1-depleted. The data presented are from samples treated with MMC, since untreated cells had very low numbers of radials (Figure 4). As expected, the FANCA-depleted line showed a marked increase in radials after MMC, such that over 65% of the cells had at least one radial, authenticating the depletion. When both ERCC1 and FANCA were depleted, the percentage of cells with radials was reduced to about 25% (P<0.0001) (Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Radial formation.

A.Percent radials observed in FANCA-depleted GM639, GM6914 (FANCA), or PD20 (FANCD2) cells with or without ERCC1 depletion. Samples were treated with MMC as in Methods. ‘Percent radials’ indicates the percent of cells with one or more radials. B. Immunoblot showing FANCA depletion.

ERCC1 was also depleted in two FA patient transformed fibroblast cell lines. Depletion of ERCC1 in FANCA cells resulted in a decrease in radials (34% to 28% of cells) (Figure 4). Depletion of ERCC1 in FANCD2 cells also resulted in a decrease in radials (51% to 42% of cells). In both the FANCA and FANCD2 cells, the reduction of radials was significant (p=0.0013 and p=0.0135 respectively). These results suggest that ERCC1 acts in the FA pathway for ICL response, since depletion of ERCC1 does not increase radial formation with co-depletion of FANCA or in FANCA or FANCD2 cells when treated with MMC, in contrast to normal cells.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have suggested differing roles for ERCC1 in ICL repair. One set of results led to the proposal of a role for ERCC1 in the initial incision of crosslinks, required for the formation of a DSB during S-phase [29]. That study used psoralen as the ICL agent and was based on the comet assay in CHO cells. Another study indicates that ERCC1 is not required for formation of DSBs, but rather is required for the resolution of a DSB formed after ICL formation [24]. That analysis was based on γH2AX as an index of DSBs in murine embryonic fibroblasts or ES cells. The studies reported here, using human fibroblasts with siRNA depletion, a different experimental system than the other studies, indicate ERCC1 is not required for DSB formation, and also demonstrate that the ICL- or HU-induced stalled replication forks do not fully activate the FA pathway without ERCC1, as indexed by FANCD2 focus formation and FANCD2-Ub formation. ERCC1 appears to be essential for FANCD2 focus formation during ICL repair, but not for γH2AX focus formation. The requirement for ERCC1 in order to have normal focus formation following HU treatment, where there is no crosslink to incise, indicates the role of ERCC1 includes action after DSB formation. Our results suggest that there is a common intermediate acted on by ERCC1 and the FA pathway, independent of whether the response is to a DSB from ICL repair or a collapsed fork caused by HU.

We conclude that ERCC1 acts downstream of DSB formation in the FA pathway in the system we used here. This does not exclude ERCC1/XPF from acting in incision at an ICL if the proteins are present; the heterodimer has demonstrated in vitro incision capability at an ICL, as noted. However, it also has been suggested that other NER proteins may be involved in the earliest stages of ICL repair [6,8,9,38]. Additionally, the Mus81-Eme1 complex is capable of incision at an ICL [28]. Therefore, there are multiple potential mechanisms for the initial incision at an ICL, perhaps acting in the absence of ERCC1 or XPF.

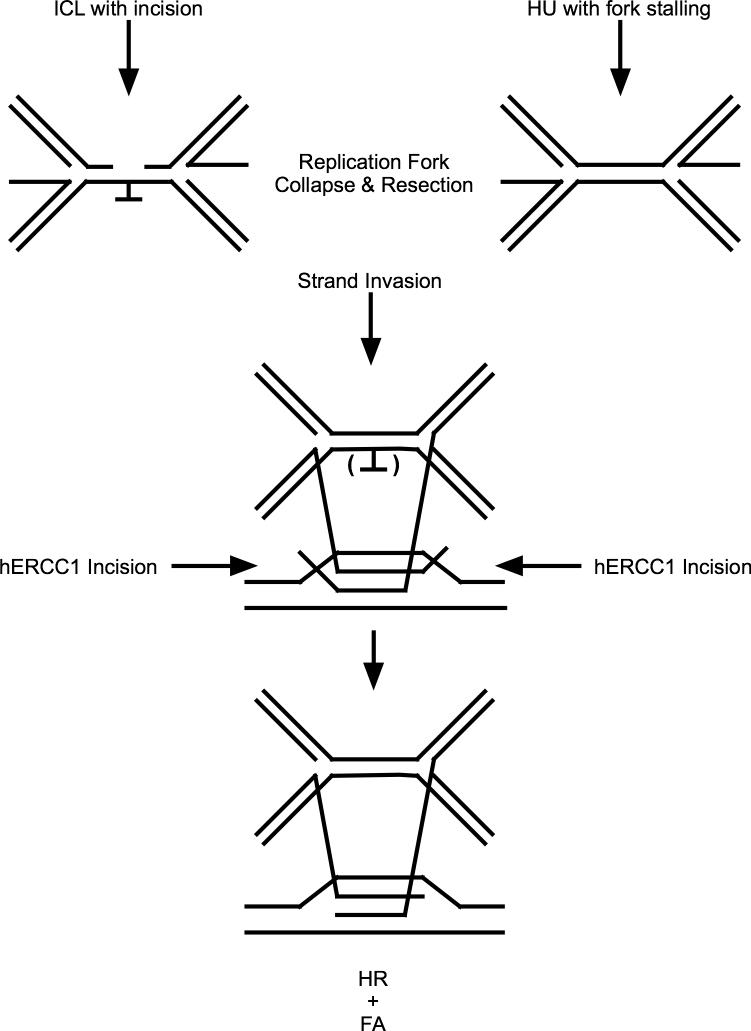

The results presented here indicate that DSBs resulting from stalled replication forks caused by HU also are processed by ERCC1. This result makes it clear that ERCC1 acts in a post-incision step in ICL repair; there is no ICL created by HU treatment. DSBs arising from mating type switching are processed normally in yeast lacking SNM1, but such cells are unable to process DSBs arising from ICLs [4]. Similarly, a RAD51 paralog in C. elegans, RFS-1, active in repair of crosslink-blocked forks, is not needed to process DSBs from stalled forks, while the RAD51 homolog is needed [39]. Thus, DSBs must differ in fine structure, and ERCC1 may act to generate a common intermediate for later HR repair steps and to signal for FANCD2-Ub focus formation. If the intermediate upon which ERCC1 acts is common to the process of ICL repair and resolution of stalled replication forks caused by HU, it would be reasonable that the intermediate is either part of the stalled replication fork, perhaps a region of single stranded DNA, or a recombination intermediate with overhanging single stranded ends (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Model of ICL and stalled replication fork repair with a shared intermediate.

The parenthesis indicates excision site of the ICL, if present.

In order to generate a common intermediate substrate from stalled replication forks or ICL repair, a possible mechanism would be incision at the ICL or resection at the stalled fork, generating a single stranded DNA followed by strand invasion into regions of high similarity, but not perfect homology (Figure 5). It is possible ERCC1 serves to trim 3’-ssDNA overhangs adjacent to duplex DNA at the sites of strand exchange, following strand invasion of a non-allelic homologous region. Such overhangs would prevent extension from the site of strand exchange (Figure 5). Once trimmed, the 3’-ssDNA could extend. Such a role for ERCC1 after incision at the ICL is consistent with several previously published reports [9,22,23]. Thus, ERCC1 might act to trim overhanging ends, allowing recombination to proceed, in conjunction with activation of the FA pathway (Figure 5).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (1PO1HL48546). The authors thank J. Hejna and M. Holtorf for their assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lawley P, Phillips D. DNA adducts from chemotherapeutic agents. Mutat Res. 1996;355:13–40. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(96)00020-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole R. Repair of DNA containing interstrand crosslinks in Escherichia coli: sequential excision and recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:1064–1068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.70.4.1064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dronkert M, Kanaar R. Repair of DNA interstrand cross-links. Mutat Res. 2001;486:217–247. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grossmann K, Ward A, Matkovic M, Folias A, Moses R. S. cerevisiae has three pathways for DNA interstrand crosslink repair. Mutat Res. 2001;487:73–83. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8777(01)00106-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jachymczyk W, von Borstel R, Mowat M, Hastings P. Repair of interstrand cross-links in DNA of Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires two systems for DNA repair: the RAD3 system and the RAD51 system. Mol Gen Genet. 1981;182:196–205. doi: 10.1007/BF00269658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahn B, Kang D, Kim H, Wei Q. Repair of mitomycin C cross-linked DNA in mammalian cells measured by a host cell reactivation assay. Mol Cells. 2004;18:249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mirchandani K, D'Andrea A. The Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway: a coordinator of cross-link repair. Exp Cell Res. 2006;312:2647–2653. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thoma B, Wakasugi M, Christensen J, Reddy M, Vasquez K. Human XPC-hHR23B interacts with XPA-RPA in the recognition of triplex-directed psoralen DNA interstrand crosslinks. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:2993–3001. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Silva I, McHugh P, Clingen P, Hartley J. Defining the roles of nucleotide excision repair and recombination in the repair of DNA interstrand cross-links in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7980–7990. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.7980-7990.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kennedy R, D'Andrea A. The Fanconi Anemia/BRCA pathway: new faces in the crowd. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2925–2940. doi: 10.1101/gad.1370505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collis S, Barber L, Ward J, Martin J, Boulton S. C. elegans FANCD2 responds to replication stress and functions in interstrand cross-link repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1398–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houghtaling S, Newell A, Akkari Y, Taniguchi T, Olson S, Grompe M. Fancd2 functions in a double strand break repair pathway that is distinct from non-homologous end joining. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3027–3033. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marek L, Bale A. Drosophila homologs of FANCD2 and FANCL function in DNA repair. DNA Repair (Amst) 2006;5:1317–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2006.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scata K, El-Deiry W. Zebrafish: swimming towards a role for fanconi genes in DNA repair. Cancer Biol Ther. 2004;3:501–502. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tischkowitz M, Hodgson S. Fanconi anaemia. J Med Genet. 2003;40:1–10. doi: 10.1136/jmg.40.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tamary H, Alter B. Current diagnosis of inherited bone marrow failure syndromes. Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2007;24:87–99. doi: 10.1080/08880010601123240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reid S, Schindler D, Hanenberg H, Barker K, Hanks S, Kalb R, Neveling K, Kelly P, Seal S, Freund M, Wurm M, Batish S, Lach F, Yetgin S, Neitzel H, Ariffin H, Tischkowitz M, Mathew C, Auerbach A, Rahman N. Biallelic mutations in PALB2 cause Fanconi anemia subtype FA-N and predispose to childhood cancer. Nat Genet. 2007;39:162–164. doi: 10.1038/ng1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tischkowitz M, Xia B, Sabbaghian N, Reis-Filho J, Hamel N, Li G, van Beers E, Li L, Khalil T, Quenneville L, Omeroglu A, Poll A, Lepage P, Wong N, Nederlof P, Ashworth A, Tonin P, Narod S, Livingston D, Foulkes W. Analysis of PALB2/FANCN-associated breast cancer families. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:6788–6793. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701724104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smogorzewska A, Matsuoka S, Vinciguerra P, McDonald E.r., Hurov K, Luo J, Ballif B, Gygi S, Hofmann K, D'Andrea A, Elledge S. Identification of the FANCI Protein, a Monoubiquitinated FANCD2 Paralog Required for DNA Repair. Cell. 2007;129:289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Collins A. Mutant rodent cell lines sensitive to ultraviolet light, ionizing radiation and cross-linking agents: a comprehensive survey of genetic and biochemical characteristics. Mutat Res. 1993;293:99–118. doi: 10.1016/0921-8777(93)90062-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niedernhofer L, Lalai A, Hoeijmakers J. Fanconi anemia (cross)linked to DNA repair. Cell. 2005;123:1191–1198. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Adair G, Rolig R, Moore-Faver D, Zabelshansky M, Wilson J, Nairn R. Role of ERCC1 in removal of long non-homologous tails during targeted homologous recombination. EMBO J. 2000;19:5552–5561. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.20.5552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Niedernhofer L, Essers J, Weeda G, Beverloo B, de Wit J, Muijtjens M, Odijk H, Hoeijmakers J, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required for targeted gene replacement in embryonic stem cells. EMBO J. 2001;20:6540–6549. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.22.6540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Niedernhofer L, Odijk H, Budzowska M, van Drunen E, Maas A, Theil A, de Wit J, Jaspers N, Beverloo H, Hoeijmakers J, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Ercc1-Xpf is required to resolve DNA interstrand cross-link-induced double-strand breaks. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–5787. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.13.5776-5787.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fisher LA, Bessho M, Bessho T. Processing of a psoralen DNA interstrand cross-link by XPF-ERCC1 complex in vitro. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:1275–1281. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumaresan KR, Hwang M, Thelen MP, Lambert MW. Contribution of XPF functional domains to the 5' and 3' incisions produced at the site of a psoralen interstrand cross-link. Biochemistry. 2002;41:890–896. doi: 10.1021/bi011614z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumaresan KR, Sridharan DM, McMahon LW, Lambert MW. Deficiency in Incisions Produced by XPF at the Site of a DNA Interstrand Cross-Link in Fanconi Anemia Cells. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14359–14368. doi: 10.1021/bi7015958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanada K, Budzowska M, Modesti M, Maas A, Wyman C, Essers J, Kanaar R. The structure-specific endonuclease Mus81-Eme1 promotes conversion of interstrand DNA crosslinks into double-strands breaks. Embo J. 2006;25:4921–4932. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rothfuss A, Grompe M. Repair kinetics of genomic interstrand DNA cross-links: evidence for DNA double-strand break-dependent activation of the Fanconi anemia/BRis required. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:5776–5787. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.1.123-134.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bergstralh DT, Sekelsky J. Interstrand crosslink repair: can XPF-ERCC1 be let off the hook? Trends Genet. 2008;24:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rogakou E, Boon C, Redon C, Bonner W. Megabase chromatin domains involved in DNA double-strand breaks in vivo. J Cell Biol. 1999;146:905–916. doi: 10.1083/jcb.146.5.905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Su TT. Cellular responses to DNA damage: one signal, multiple choices. Annu Rev Genet. 2006;40:187–208. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.40.110405.090428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JM, Kee Y, Gurtan A, D'Andrea AD. Cell cycle dependent chromatin loading of the fanconi anemia core complex by FANCM/FAAP24. Blood. 2008 doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-113092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bogliolo M, Lyakhovich A, Callen E, Castella M, Cappelli E, Ramirez M, Creus A, Marcos R, Kalb R, Neveling K, Schindler D, Surralles J. Histone H2AX and Fanconi anemia FANCD2 function in the same pathway to maintain chromosome stability. EMBO J. 2007;26:1340–1351. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Newell A, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Rosenthal A, Reifsteck C, Cox B, Grompe M, Olson S. Interstrand crosslink-induced radials form between non-homologous chromosomes, but are absent in sex chromosomes. DNA Repair (Amst) 2004;3:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruun D, Folias A, Akkari Y, Cox Y, Olson S, Moses R. siRNA depletion of BRCA1, but not BRCA2, causes increased genome instability in Fanconi anemia cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2003;2:1007–1013. doi: 10.1016/s1568-7864(03)00112-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hemphill AW, Bruun D, Thrun L, Akkari Y, Torimaru Y, Hejna K, Jakobs PM, Hejna J, Jones S, Olson SB, Moses RE. Mammalian SNM1 is required for genome stability. Mol Genet Metab. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volker M, Mone M, Karmakar P, van Hoffen A, Schul W, Vermeulen W, Hoeijmakers J, van Driel R, van Zeeland A, Mullenders L. Sequential assembly of the nucleotide excision repair factors in vivo. Mol Cell. 2001;8:213–224. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00281-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ward JD, Barber LJ, Petalcorin MI, Yanowitz J, Boulton SJ. Replication blocking lesions present a unique substrate for homologous recombination. Embo J. 2007;26:3384–3396. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]