Abstract

Purpose

To identify and mathematically model molecular predictors of response to the enediyne chemotherapeutic agent, neocarzinostatin, in nervous system cancer cell lines.

Methods

Human neuroblastoma, breast cancer, glioma, and medulloblastoma cell lines were maintained in culture. Content of caspase-3 and Bcl-2, respectively, was determined relative to actin content for each cell line by Western blotting and optical densitometry. For each cell line, sensitivity to neocarzinostatin was determined. Brain tumor cell lines were stably transfected with human Bcl-2 cDNA cloned into the pcDNA3 plasmid vector.

Results

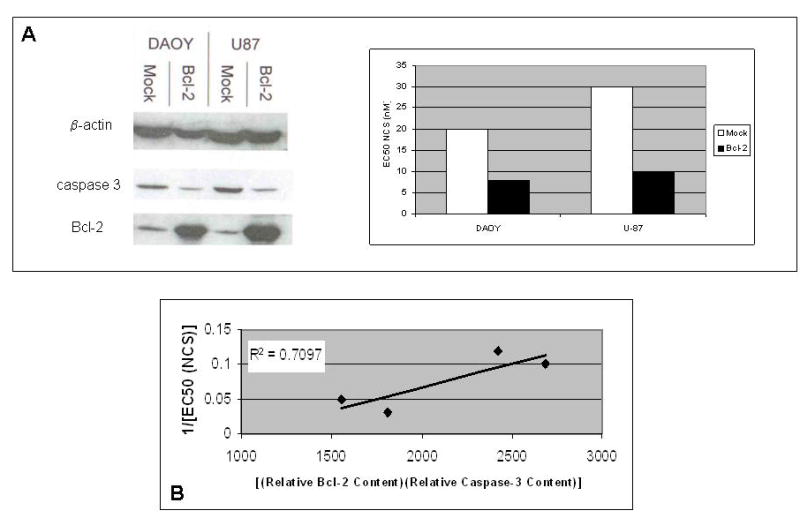

In human tumor cell lines of different tissue origins, sensitivity to neocarzinostatin is proportional to the product of the relative contents of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 (r2 = 0.9; p < 0.01). Neuroblastoma and brain tumor cell lines are particularly sensitive to neocarzinostatin; the sensitivity of brain tumor lines to neocarzinostatin is enhanced by transfection with an expression construct for Bcl-2 and is proportional in transfected cells to the product of the relative contents of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 (r2 = 0.7).

Conclusion

These studies underscore the potential of molecular profiling in identifying effective chemotherapeutic paradigms for cancer in general and tumors of the nervous system in particular.

Keywords: Enediyne, Caspase-3, Bcl-2, Brain Tumors, Targeted Therapy

Overproduction of Bcl-2 and other antiapoptotic gene products is a common mechanism of chemotherapeutic resistance.[1–7] We have previously reported the paradoxical potentiation by Bcl-2 of apoptosis induction by the disulfide reduction-dependent enediyne, neocarzinostatin (NCS). [8–11] As overproduction of Bcl-2 in PC12 pheochromocytoma cells is associated with increased cellular reducing potential,[12] it was hypothesized that this condition resulted in enhanced activation of NCS and consequent potentiation of apoptosis.[8] However, Bcl-2 acts downstream of NCS activation and should block apoptosis even in the face of enhanced enediyne activation. Further mechanistic studies revealed that, in PC12 neural crest tumor cells, NCS treatment results in caspase-3-dependent cleavage of Bcl-2 to its proapoptotic counterpart,[13] and that this cleavage is critical for potentiation of apoptosis by Bcl-2.[9, 13] This suggests that NCS could be an effective and relatively non-toxic chemotherapeutic agent for those tumors that overproduce Bcl-2 and express caspase-3. Potentiation of efficacy would be predicted to occur only in those cells for which both conditions obtained. If this is indeed the case, it would serve as proof-of-principle for the notion of identification of molecular markers for responsiveness of particular human cancers to particular chemotherapeutic strategies.

To test this hypothesis and the generalizability of the prediction it suggests, we examined the correlations between the EC50 of NCS for cell culture growth rate depression (i.e., the concentration of NCS at which cell culture growth rate is half of that seen in vehicle-treated cultures) and Bcl-2 expression, caspase-3 expression, and the product of Bcl-2 expression and caspase-3 expression, respectively, in each of seven different tumor cell lines. We used the product of Bcl-2 expression and caspase-3 expression in this model as we had predicted that, if either fell to zero, potentiation of the effects of NCS on culture cell growth would not take place; that is, as the product of Bcl-2 expression and caspase-3 expression go to zero, the EC50 of NCS for cell culture growth rate depression goes to infinity. To model this inverse relationship, we plotted [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] versus 1/[EC50 (NCS)]. As tumors of the central and peripheral nervous system represent some of the greatest chemotherapeutic challenges and present some of the most robust drug targeting opportunities, and given our success with this strategy in neural crest-derived PC12 cells, we initiated these studies using human nervous system (neuroblastoma, glioma, medulloblastoma) tumor cell lines and compared these results to those obtained using human breast cancer cell lines. We herein demonstrate the prediction of sensitivity of tumor cell lines to NCS from the protein content of Bcl-2 and caspase-3.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

SK-N-MC, SK-N-SH, and IMR-32 human neuroblastoma, MCF-7 and BT474 human breast cancer, U87 human glioma, and DAOY human medulloblastoma cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD) and maintained in culture as previously described.[14, 15] Note that all of these cell lines express only wild-type p53 [16–18].

Western Blotting

Cells of each line were lysed in RIPA buffer [1% lgepal-CA-630 (Sigma), 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS in 1X PBS] and centrifuged, and the resulting supernatants were assayed for protein content. One hundred μg of protein was loaded per lane on a 12.5% polyacrylamide gel and Western blotting was performed as we have previously described.[13] The same blot was stained for Bcl-2 (anti-Bcl-2 C-2 mouse monoclonal antibody SC-7382; Santa Cruz), stripped, and then stained for caspase-3 (anti-caspase-3 H-277 rabbit polyclonal IgG SC7148; Santa Cruz) and β-actin in sequence. Relative quantitation of Bcl-2 and caspase-3 was performed by Scion imaging measurement of the optical densities of bands for Bcl-2 and caspase-3, respectively, and normalizing these values to the optical density of the corresponding band for β-actin.

Determination of Sensitivity to NCS

Each cell line was plated on 6-well tissue culture plates and allowed to adhere overnight at 37°C in 5% CO2. Each line was treated with NCS [0 (i.e., vehicle-treated), 5, 15, and 20 nM] for 1 h, then washed free of the drug. For each cell line, cell counts, performed as we have previously described[8–11, 14, 15] 48 h after treatment at each concentration of NCS were plotted and the concentration at which the 48 h cell count was 50% of the 48 h cell count of vehicle-treated cells (EC50) was determined.

Transfection of Cells with a bcl-2 Expression Construct

Human Bcl-2 cDNA was cloned into the pcDNA3 plasmid vector (Invitrogen). DAOY, and U87 cells were transfected using a Nucleofector electroporator (Amaxa). Stably-transfected cells were selected using 500 μg/ml G418 (Cellgro). After selection, cultures were maintained in standard medium supplemented with 250 μg/ml G418. Bcl-2 expression was confirmed by Western blot. Transfection efficiency, as determined by green fluorescent protein transfection and fluorescence, was as follows: DAOY: 41%; U87: 89%.

Results

Bcl-2 and caspase-3 content of neuroblastoma, breast cancer, and brain tumor cell lines

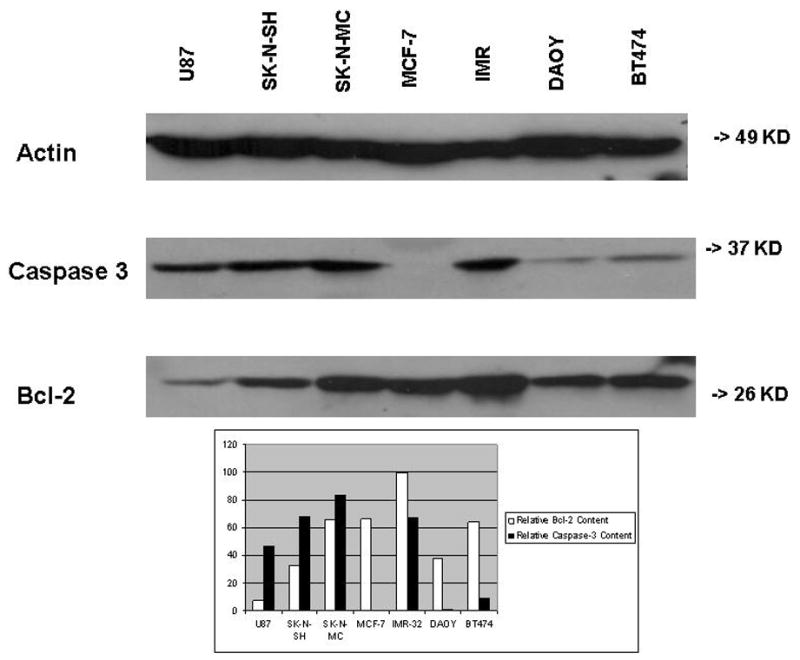

Western blotting was performed on homogenates of 3 neuroblastoma, 2 breast cancer, and 2 brain tumor (glioma and medulloblastoma, respectively) cell lines. (See Fig. 1 for a representative blot.) The optical density of the bands obtained for each was normalized to that of the band for β-actin on the same blot. The average normalized optical density from two independent experiments was computed for each protein in each cell line.

Fig. 1.

Representative Western Blot. Lysates of cultured SK-N-SH, SK-N-MC, and IMR-32 neuroblastoma cells, BT474 and MCF-7 breast cancer cells, U87 glioma cells, and DAOY medulloblastoma cells were applied to an SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred to a membrane for Western blotting as described in Materials and Methods. The same blot was stained with antibodies to Bcl-2, caspase-3, and β-actin, respectively. Western blot bands obtained for each cell lysate were subjected to optical densitometry and the values for Bcl-2 and caspase-3, respectively, were normalized to the value for β-actin on the same blot. Results are expressed as relative optical densities.

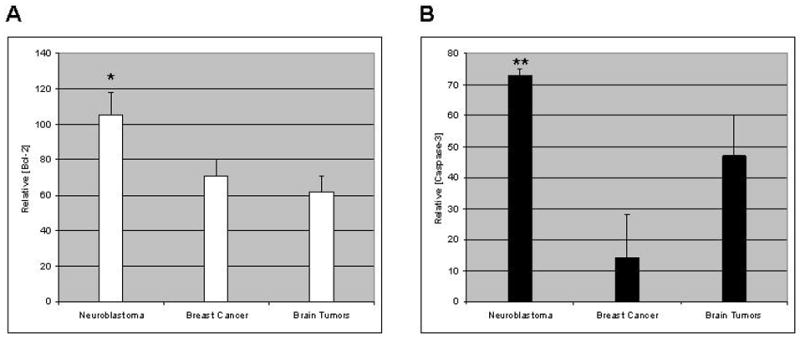

As is shown in Table 1, relative Bcl-2 content among the group of tumor lines as a whole spanned a 2.4-fold range (53–126). Neuroblastoma lines as a group exhibited higher Bcl-2 content than breast or brain tumors, and the latter two tissue types were similar to one another in Bcl-2 content (Fig. 2A).

TABLE 1.

Western Blot-determined Relative Content of Bcl-2 and Caspase-3 and Tissue Culture-determined EC50 (NCS) for Seven Tumor Cell Lines

| Cell Line | Relative Bcl-2 Content Average (Experiment 1, Experiment 2) | Relative Caspase-3 Content Average (Experiment 1, Experiment 2) | EC50 (NCS) (nM) (n = 3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| SK-N-SH | 82 (33, 132) | 69 (69, 69) | 19 ± 1 |

| U87 | 53 (7, 99) | 60 (47, 74) | 29 ± 6 |

| IMR-32 | 126 (99, 152) | 75 (67, 82) | 14 ± 1 |

| SK-N-MC | 106 (66, 147) | 75 (83, 67) | 11 ± 1 |

| DAOY | 71 (38, 105) | 34 (1, 66) | 53 ± 26 |

| MCF-7 | 80 (66, 93) | 0.1 (0.2, 0) | 97 ± 28 |

| BT474 | 62 (64, 60) | 28 (9, 46) | 83 ± 3 |

Fig. 2.

Western blot bands obtained for each cell lysate in each of two independent experiments were subjected to optical densitometry and the values for Bcl-2 and caspase-3, respectively, were normalized to the value for β-actin on the same blot. Averages of the results of two independent blots for each cell line were then averaged within tumor type. Results are expressed as relative optical densities (± SEM) for each tumor type. (a) Bcl-2; (b) caspase-3. *Greater than values for breast cancer with p<0.05; **greater than values for breast cancer with p<0.01 (Student’s t-test). Neither Bcl-2 nor caspase-3 content differs significantly between brain and breast cancer.

Table 1 also demonstrates the broad range of relative caspase-3 content (0.1–75) among the cell lines examined. Neuroblastoma and brain tumor lines exhibited similarly high caspase-3 content, while breast cancer lines exhibited low caspase-3 content (Fig. 2B).

Relationship of sensitivity to NCS-induced cell death to Bcl-2 content, caspase-3 content, and the product of the two, respectively

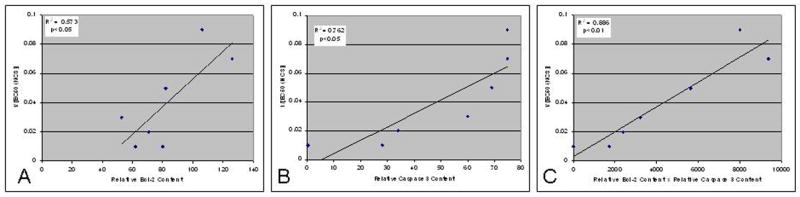

Our prior studies[8–11, 13] suggested that, if either caspase-3 or Bcl-2 levels fell to zero, potentiation of NCS-induced cell death would not occur. We therefore predicted that EC50 (NCS) would vary inversely with the product of the relative contents of Bcl-2 and caspase-3. That is, we predicted that 1/[EC50 (NCS)] would be directly related to [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)].

Fig. 3 shows the relationship between 1/[EC50 (NCS)] and the optical density of the caspase-3 band (A), the Bcl-2 band (B), and the product of the optical densities of the caspase-3 and Bcl-2 bands (C), respectively. The product of the optical densities of the caspase-3 and Bcl-2 bands demonstrates the best correlation with 1/[EC50 (NCS)].

Fig. 3.

Plots of (a) average relative Bcl-2 content; (b) average relative caspase-3 content; and (c) the product of average relative caspase-3 content and average relative Bcl-2 content versus 1/[EC50 (NCS)] for cell death induced by neocarzinostatin for cell lines described in Table 1. Relative protein content was determined for caspase-3 and Bcl-2, respectively, by optical densitometry of Western blot bands, as described in Materials and Methods, in two independent experiments. In each panel, plots are shown for the average of the two values obtained for each cell line. R2 was determined by linear regression; p was determined by two-way ANOVA.

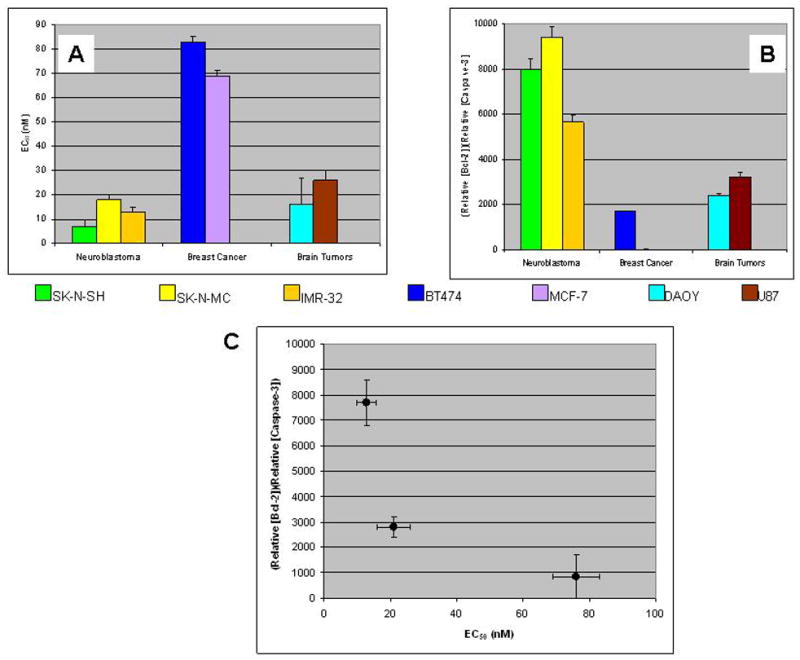

Given the differences observed between the tumor types origin of the cell lines tested and their contents of Bcl-2 and caspase-3, we then sought to determine whether the rank order and mean of the product, [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)], for each tumor type predicts the EC50 for NCS of that tumor type. Fig. 4A demonstrates the rank order of EC50 for NCS of the tumors to be breast cancer > brain tumors > neuroblastoma. Conversely, the rank order of [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] is neuroblastoma > brain tumors > breast cancer (Fig. 4B). Fig. 4C plots the mean (± SEM) of [EC50 (NCS)] versus the mean (± SEM) of [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] for each of the three tumor types and demonstrates that, albeit with small numbers of each type of tumor, the data for each respective tumor type cluster tightly and uniquely from the others. Note that the EC50 for neuroblastomas is less than that for breast cancer with p<0.001 and the EC50 for brain tumors is less than that for breast cancer with p<0.005 (Student’s t-test). Similarly, [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] for neuroblastomas is greater than that for breast cancer with p<0.005 and [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] for brain tumors is greater than that for breast cancer with p=0.05.

Fig. 4.

EC50 (NCS) (a) and the product of relative caspase-3 content and relative Bcl-2 content (b) displayed by tumor type. (c) Mean (n = 3 for each cell line) EC50 (NCS) versus product of relative caspase-3 content and relative Bcl-2 content (n = 2 for each cell line) for each of three tissues of tumor origin. Error bars denote the SEM. Statistical analysis (Student’s t-test): EC50 (NCS) neuroblastomas < breast cancer, p<0.001; EC50 (NCS) brain tumors < breast cancer, p<0.005; [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] neuroblastomas > breast cancer, p<0.005; [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] brain tumors > breast cancer, p=0.05.

Effect of transfection with a bcl-2 expression construct on sensitivity to NCS of human brain tumor cell lines

We transfected the two brain tumor cell lines with bcl-2 to verify that increasing Bcl-2 would in fact lead to potentiation of apoptosis in central nervous system cancer. As is shown by the Western blot in Fig. 5A. transfection of the medulloblastoma (DAOY) and glioma (U87) cell lines with a bcl-2 expression construct resulted in overexpression of bcl-2 and consequent overproduction of its protein product, Bcl-2. Interestingly, overexpression of bcl-2 in DAOY and U87 cells was associated with a decrease in production of caspase 3. Although the mechanism for this coordinate, complementary regulation of expression is not known, it has recently been reported in Dalton’s lymphoma ascites cells treated with the chemotherapeutic natural product, abrin [19]. Nonetheless, in bcl-2-transfected DAOY and U87 cells, increased [(relative Bcl-2 content)(relative caspase-3 content)] is associated with increased sensitivity to NCS (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

(a) Relationship between the product of relative caspase-3 content and relative Bcl-2 content and EC50 (NCS) for native central nervous system cancer cell lines and bcl-2 transfectants of the same cell lines. The Western blot on the left demonstrates the enhanced Bcl-2 content of transfectants relative to their native counterparts. (b) Product of relative Bcl-2 content and relative caspase-3 content versus 1/[EC50 (NCS)] for paired native and bcl-2-transfected central nervous system cancer cell lines. Results of a representative experiment of four performed are shown. R2 was determined by linear regression.

Discussion

Chemoresistant tumors of the nervous system exact a significant toll among patients with cancer. The American Cancer Society estimates that 20,500 malignant tumors of the brain or spinal cord will be diagnosed during 2007 in the U.S. Approximately 12,740 people will die from these malignant tumors. CNS cancer accounts for approximately 1.3% of all cancers and 2.2% of all cancer-related deaths.[20] Brain is the most common site for solid tumors of childhood; the long-term survival rate for children who received radiation therapy for brain tumors of any type is, at best, in the neighborhood of 40%.[21] Neuroblastoma is the single most common solid tumor of childhood; 65% of children with neuroblastoma have metastatic disease at the time of initial diagnosis, and these children have only a 5–20% 5-year survival rate.[22, 23] These statistics do not even include the enormous morbidity associated with these diseases.

Therapeutic failures in this arena are at least in part the result of altered expression of proteins that function to regulate apoptosis induction and/or enactment, including those in the Bcl-2 protein family. For example, altered levels of Bcl-2 and the related protein Bcl-XL contribute to the resistance of neuroblastomas to chemotherapy.[24, 25] Similarly, medulloblastomas and glioblastomas have all been shown to overexpress the bcl-2 and or bcl-XL gene, contributing to resistance to chemotherapeutic agent-induced apoptosis.[24, 26–34] The discovery and development of strategies that overcome such drug resistance and that enhance the ability to predict responsiveness of particular tumors to particular chemotherapeutic agents would contribute greatly to the conquest of these common and deadly diseases.

Studies in our laboratory and those of others demonstrate that Bcl-2 exerts its effects at least in part by a mechanism that includes a shift in the cellular capacity for glutathione turnover.[9, 11–13, 35–39] Not surprisingly, other studies link both the initiating and subsequent steps involved in the apoptotic process to exposure of the cell to reactive oxygen species [39, 40] and demonstrate release of cytochrome c from the mitochondrion with a resultant breakdown in electron transport and increased formation of endogenous reactive oxygen species.[ 39, 41, 42] The caspases, enzymes critical for the enactment of apoptosis, are accordingly cysteine-rich and redox-active.[43]

We have pursued a strategy for overcoming Bcl-2-mediated chemoresistance that takes advantage of the increase in cellular free sulfhydryl content by using chemotherapeutic agents that require reduction by glutathione for their activity. Our initial studies focused on the efficacy of a member of one such class of agents, the enediynes, in tumor cells that were genetically engineered to overexpress bcl-2.[8]

NCS is an enediyne DNA-cleaving natural product that induces apoptosis in neural crest tumor cells in culture.[14, 44] Like many other naturally-occurring enediynes, NCS is actually a prodrug that requires sulfhydryl activation for efficacy. As such, the cytotoxicity of NCS has been demonstrated, within the range of physiological manipulations performed, to vary directly with the glutathione content of the cell.[45–47] This information led to our prediction that, contrary to the case for other chemotherapeutic agents studied, overexpression of bcl-2 and the resulting shift in glutathione handling in the cell would potentiate the induction of apoptosis by NCS.

We initially showed that, in PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells that have been bcl-2-or mock-transfected, bcl-2 overexpression does indeed potentiate the apoptosis-inducing activity of NCS.[8, 15] In this same system, bcl-2 overexpression decreases apoptosis induction by the non-enediyne, cisplatin, and synthetic and natural enediynes that do not require reductive activation by glutathione, indicating that glutathione is important in the potentiation of NCS-induced apoptosis by Bcl-2. In addition, inhibition of glutathione synthesis completely abolishes the difference in NCS sensitivity between cells that do and do not overexpress bcl-2. The glutathione-dependent enediyne prodrugs are therefore the only class of drug that has been demonstrated to work best in those tumor cells that have become resistant to other known chemotherapeutic agents.

Potentiation of NCS-induced apoptosis by Bcl-2 overproduction is dependent, not only on altered metabolism of glutathione, but also on caspase-3-mediated cleavage of Bcl-2.[9, 13] The resulting cleavage product of this anti-apoptotic protein is, in fact, pro-apoptotic. Caspase-3 activation, like NCS activation, has been demonstrated to be sulfhydryl reduction-dependent. [43, 48]

NCS and related enediynes have previously been proposed for clinical use in a variety of human cancers. Initial clinical trials of NCS were hampered by anaphylactic responses to its non-covalently bound protein component, ironically a portion of the NCS structure with no relationship to its efficacy. Our studies have taken specific advantage of the need for sulfhydryl activation of these compounds or have proposed identification of particular subgroups of patients and/or tumors for which these compounds might present an improved therapeutic index. We have found that potentiation of NCS-induced apoptosis by bcl-2 overexpression depends critically upon cellular expression of caspase-3, Bcl-2-induced enhancement of glutathione recycling capacity, and cleavability of Bcl-2 by caspase-3,[9, 13, 49] potentially allowing us to predict for which tumors NCS might be most efficacious.

The present study presents proof of principle for the prediction of efficacy of NCS by determination of the product of caspase-3 content and Bcl-2 content. It further suggests that, as a function of their relatively high Bcl-2 and caspase-3 content, cancers of the nervous system are particularly sensitive to NCS and perhaps other sulfhydryl-dependent enediynes. Verification of these results with larger numbers of cell lines and extension of these conclusions to primary tumors will require additional studies.

Acknowledgments

The studies described were funded by grants to NFS from the National Cancer Institute (R01-CA074289) and the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (R01-NS038569).

References

- 1.Bartholomeusz C, Itamochi H, Yuan LX, et al. Bcl-2 antisense oligonucleotide overcomes resistance to E1A gene therapy in a low HER2-expressing ovarian cancer xenograft model. Cancer Res. 2005;65:8406–8413. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bush JA, Li G. The role of Bcl-2 family members in the progression of cutaneous melanoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2003;20:531–539. doi: 10.1023/a:1025874502181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Del Principe MI, Del Poeta G, Maurillo L, et al. P-glycoprotein and BCL-2 levels predict outcome in adult acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:730–738. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fennell DA. Bcl-2 as a target for overcoming chemoresistance in small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2003;4:307–313. doi: 10.3816/clc.2003.n.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hopkins-Donaldson S, Cathomas R, Simoes-Wust AP, et al. Induction of apoptosis and chemosensitization of mesothelioma cells by Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL antisense treatment. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:160–166. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Real PJ, Sierra A, De Juan A, et al. Resistance to chemotherapy via Stat3-dependent overexpression of Bcl-2 in metastatic breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2002;21:7611–7618. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu CJ, Li YB, Wong MC. Expression of antisense bcl-2 cDNA abolishes tumorigenicity and enhances chemosensitivity of human malignant glioma cells. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:60–66. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cortazzo M, Schor NF. Potentiation of enediyne-induced apoptosis and differentiation by Bcl-2. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1199–1203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mi Z, Hong B, Mirnics ZK, et al. Bcl-2-mediated potentiation of neocarzinostatin-induced apoptosis: requirement for caspase-3, sulfhydryl groups, and cleavable Bcl-2. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2006;57:357–367. doi: 10.1007/s00280-005-0054-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schor NF, Tyurina YY, Fabisiak JP, et al. Selective oxidation and externalization of membrane phosphatidylserine: Bcl-2-induced potentiation of the final common pathway for apoptosis. Brain Res. 1999;831:125–130. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(99)01414-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schor NF, Rudin CM, Hartman AR, et al. Cell line dependence of Bcl-2-induced alteration of glutathione handling. Oncogene. 2000;19:472–476. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane DJ, Sarafian TA, Anton R, et al. Bcl-2 inhibition of neural death: decreased generation of reactive oxygen species. Science. 1993;262:1274–1277. doi: 10.1126/science.8235659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liang Y, Nylander KD, Yan C, et al. Role of caspase 3-dependent Bcl-2 cleavage in potentiation of apoptosis by Bcl-2. Mol Pharmacol. 2002;61:142–149. doi: 10.1124/mol.61.1.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hartsell TL, Yalowich JC, Ritke MK, et al. Induction of apoptosis in murine and human neuroblastoma cell lines by the enediyne natural product neocarzinostatin. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;275:479–485. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schor NF, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, et al. Differential membrane antioxidant effects of immediate and long-term estradiol treatment of MCF-7 breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999;260:410–415. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tweddle DA, Malcolm AJ, Cole M, Pearson ADJ, Lunec J. p53 cellular localization and function in neuroblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:2087–2077. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64678-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cerrato JA, Yung WK, Liu TJ. Introduction of mutant p53 into a wild-type p53-expressing glioma cell line confers sensitivity to Ad-p53-induced apoptosis. Neuro Oncol. 2001;3:113–122. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/3.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castellino RC, De Bortoli M, Lu X, et al. Medulloblastomas overexpress the p53-inactivating oncogene WIP1/PPM1D. J Neuro-oncol. 2007;86:245–256. doi: 10.1007/s11060-007-9470-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramnath V, Rekha PS, Kuttan G, Kuttan R. Regulation of caspase-3 and Bcl-2 expression in Dalton’s lymphoma ascites cells by abrin. Evid-based Complement Alter Med. 2007 doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Cancer Society. What are the key statistics for brain and spinal cord tumors? 2007. 2007 http://www.cancer.org/docroot/CRI/content/CRI_2_4_1X_What_are_the_key_statistics_for_brain_and_spinal_cord_tumors_3.asp?sitearea=

- 21.Jenkin D, Greenberg M, Hoffman H, et al. Brain tumors in children: long-term survival after radiation treatment. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;31:445–451. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)00393-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haase GM, Perez C, Atkinson JB. Current aspects of biology, risk assessment, and treatment of neuroblastoma. Semin Surg Oncol. 1999;16:91–104. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2388(199903)16:2<91::aid-ssu3>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotterill SJ, Pearson AD, Pritchard J, et al. Clinical prognostic factors in 1277 patients with neuroblastoma: results of The European Neuroblastoma Study Group ‘Survey’ 1982–1992. Eur J Cancer. 2000;36:901–908. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(00)00058-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dole M, Nunez G, Merchant AK, et al. Bcl-2 inhibits chemotherapy-induced apoptosis in neuroblastoma. Cancer Res. 1994;54:3253–3259. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dole MG, Jasty R, Cooper MJ, et al. Bcl-xL is expressed in neuroblastoma cells and modulates chemotherapy-induced apoptosis. Cancer Res. 1995;55:2576–2582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Campos L, Rouault JP, Sabido O, et al. High expression of bcl-2 protein in acute myeloid leukemia cells is associated with poor response to chemotherapy. Blood. 1993;81:3091–3096. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakasu S, Nakasu Y, Nioka H, et al. Bcl-2 Protein Expression in Tumors of the Central Nervous System. Acta Neuropathol. 1994;88:520–526. doi: 10.1007/BF00296488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teixeira C, Reed JC, Pratt MA. Estrogen promotes chemotherapeutic drug resistance by a mechanism involving Bcl-2 proto-oncogene expression in human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:3902–3907. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonetti A, Zaninelli M, Pavanel F, et al. Bcl-2 expression is associated with resistance to chemotherapy in advanced breast cancer. Proc Amer Assoc Cancer Research. 1996;37:192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beham AW, McDonnell TJ. Bcl-2 confers resistance to androgen deprivation in prostate carcinoma cells. Proc Amer Assoc Cancer Research. 1996;37:224. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tu Y, Renner S, Xu F, et al. BCL-X expression in multiple myeloma: possible indicator of chemoresistance. Cancer Res. 1998;58:256–262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van de Donk NW, de Weerdt O, Veth G, et al. G3139, a Bcl-2 antisense oligodeoxynucleotide, induces clinical responses in VAD refractory myeloma. Leukemia. 2004;18:1078–1084. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams J, Lucas PC, Griffith KA, et al. Expression of Bcl-xL in ovarian carcinoma is associated with chemoresistance and recurrent disease. Gynec Oncol. 2005;96:287–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganigi PM, Santosh V, Anandh B, et al. Expression of p53, EGFR, pRb and bcl-2 proteins in pediatric glioblastoma multiforme: a study of 54 patients. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2005;41:292–299. doi: 10.1159/000088731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albrecht H, Tschopp J, Jongeneel CV. Bcl-2 protects from oxidative damage and apoptotic cell death without interfering with activation of NF-kappa B by TNF. FEBS Lett. 1994;351:45–48. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00817-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Carta G, et al. Direct evidence for antioxidant effect of Bcl-2 in PC12 rat pheochromocytoma cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;344:413–423. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1997.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liang Y, Mirnics ZK, Yan C, et al. Bcl-2 mediates induction of neural differentiation. Oncogene. 2003;22:5515–5518. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friesen C, Kiess Y, Debatin KM. A critical role of glutathione in determining apoptosis sensitivity and resistance in leukemia cells. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(Suppl 1):S73–85. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen Q, Chai YC, Mazumder S, et al. The late increase in intracellular free radical oxygen species during apoptosis is associated with cytochrome c release, caspase activation, and mitochondrial dysfunction. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:323–334. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tyurina YY, Nylander KD, Mirnics ZK, et al. The intracellular domain of p75NTR as a determinant of cellular reducing potential and response to oxidant stress. Aging Cell. 2005;4:187–196. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2005.00160.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang J, Liu X, Bhalla K, et al. Prevention of apoptosis by Bcl-2: release of cytochrome c from mitochondria blocked. Science. 1997;275:1129–1132. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kluck RM, Bossy-Wetzel E, Green DR, et al. The release of cytochrome c from mitochondria: a primary site for Bcl-2 regulation of apoptosis. Science. 1997;275:1132–1136. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5303.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Baker A, Santos BD, Powis G. Redox control of caspase-3 activity by thioredoxin and other reduced proteins. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;268:78–81. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hartsell TL, Hinman LM, Hamann PR, et al. Determinants of the response of neuroblastoma cells to DNA damage: the roles of pre-treatment cell morphology and chemical nature of the damage. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1996;277:1158–1166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Beerman TA, Poon R, Goldberg IH. Single-strand nicking of DNA in vitro by neocarzinostatin and its possible relationship to the mechanism of drug action. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1977;475:294–306. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(77)90020-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeGraff WG, Mitchell JB. Glutathione dependence of neocarzinostatin cytotoxicity and mutagenicity in Chinese hamster V-79 cells. Cancer Res. 1985;45:4760–4762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schor NF. Targeted enhancement of the biological activity of the antineoplastic agent, neocarzinostatin. Studies in murine neuroblastoma cells. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:774–781. doi: 10.1172/JCI115655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Samali A, Zhivotovsky B, Jones DP, et al. Detection of pro-caspase-3 in cytosol and mitochondria of various tissues. FEBS Lett. 1998;431:167–169. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00740-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liang Y, Yan C, Schor NF. Apoptosis in the absence of caspase 3. Oncogene. 2001;20:6570–6578. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]