Abstract

Dimethandrolone undecanoate (DMAU: 7α,11β-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone 17β-undecanoate) is a potent orally active androgen in development for hormonal therapy in men. Cleavage of the 17β-ester bond by esterases in vivo leads to liberation of the biologically active androgen, dimethandrolone (DMA), a 19-norandrogen. For hormone replacement in men, administration of C19 androgens such as testosterone (T) may lead to elevations in circulating levels of estrogens due to aromatization. As several reports have suggested that certain 19-norandrogens may serve as substrates for the aromatase enzyme and are converted to the corresponding aromatic A-ring products, it was important to investigate whether DMA, the related compound, 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone (11β-MNT), also being tested for hormonal therapy in men, and other 19-norandrogens can be converted to aromatic A-ring products by human aromatase. The hypothetical aromatic A-ring product corresponding to each substrate was obtained by chemical synthesis. These estrogens bound with high affinity to purified recombinant human estrogen receptors (ER) α and β in competitive binding assays (IC50's: 5−12 × 10−9 M) and stimulated transcription of 3XERE-luciferase in T47Dco human breast cancer cells with a potency equal to or greater than that of estradiol (E2) (EC50's: 10−12 to 10−11 M). C19 androgens (T, 17α-methyltestosterone (17α-MT), androstenedione (AD), and 16α-hydroxyandrostenedione (16α-OHAD)), 19-norandrogens (DMA, 11β-MNT, 19-nortestosterone (19-NT), and 7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone (MENT)) or the structurally similar 19-norprogestin, norethindrone (NET) were incubated at 50 μM with recombinant human aromatase for 10−180 min at 37 °C. The reactions were terminated by extraction with acetonitrile and centrifugation, and substrate and potential product were separated by HPLC. Retention times were monitored by UV absorption, and UV peaks were quantified using standard curves. Aromatization of the positive controls, T, AD, and 16α-OHAD was linear for 40−60 min, and conversion of T or AD was complete by 120 min. The nonsteroidal aromatase inhibitor, letrozole, demonstrated concentration-dependent suppression of T aromatization. Under the same conditions, there was no detectable conversion of DMA, 11β-MNT, or NET to their respective hypothetical aromatic A-ring products during incubation times up to 180 min. Aromatization of MENT and 19-NT proceeded slowly and was limited. Collectively, these data support the notion that in the absence of the C19-methyl group, which is the site of attack by oxygen, aromatization of androgenic substrates proceeds slowly or not at all and that this reaction is impeded by the presence of a methyl group at the 11β position.

Keywords: Human aromatase, C19 androgens, 19-Norandrogens, Estrogen receptors, Transcription, Hormonal therapy for men

1. Introduction

Current androgen replacement therapies for hypogonadal or aging men involve the use of the natural hormone, testosterone (T). When pure T is administered orally, however, only a small amount reaches the circulation due to absorption from the gastrointestinal tract into the portal blood and degradation by the liver (first-pass effect) [1]. Thus, for oral administration, T has been esterified with fatty acids (e.g. T undecanoate), alkylated at the 17α-position (e.g. 17α-methyltestosterone (17α-MT)), or applied buccally or sublingually. Alternatively, T can be implanted as a subdermal pellet, administered transdermally as a patch or gel, or injected intramuscularly as a fatty acid ester [2].

Dimethandrolone (DMA: 7α,11β-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone) is a potent orally active synthetic 19-norandrogen. We are currently assessing the 17β-undecanoic acid ester of DMA as a potential agent for androgen therapy [3]. Cleavage of the ester bond in the body liberates the biologically active unesterified DMA. As a result of its potency and oral bioavailability, DMA undecanoate has the potential advantage that it could be used at relatively low doses. Various esters of the 11β-monomethylated analogue of DMA are also under development for hormonal therapy in men.

It is likely that some of the biological effects of T are a result of its aromatization to estradiol (E2) by the aromatase enzyme which is present in various tissues of humans and higher primates including gonads, brain, placenta, and adipose tissue [4]. Thus, it was important to investigate the potential for DMA, 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone (11β-MNT), and related 19-norsteroids to undergo aromatization. The aromatase enzyme, a member of the cytochrome P450 superfamily, is encoded by the CYP19 gene. The enzyme complex, which is composed of 2 subunits, aromatase P450 and an NADPH cytochrome C reductase, is localized to the microsomal fraction of estrogen-producing cells. Aromatization of C19 androgens such as T and androstenedione (AD) to their C18 aromatic A-ring products, estradiol and estrone (E1), respectively, takes place in three sequential steps [4–6]: (1) hydroxylation of the C19-methyl group; (2) a second hydroxylation of the C19-methyl group to form a 19-oxo-compound; (3) cleavage of the bond between C10 and C19 to yield formic acid and the aromatized A-ring product with loss of the hydrogen atoms at the 1β and 2β positions. Although the mechanism of action of human aromatase involves the C19-methyl group, published findings concerning the potential aromatization of 19-norandrogens in vitro and in vivo have been contradictory [7–14]. Most of these studies have employed human placental microsomes or Leydig or granulosa cells which contain other enzymatic activities, and detection methods involving thin layer or gas chromatography, HPLC, or radioimmunoassays.

In the current study, we attempted to detect aromatization of DMA, 11β-MNT, and related 19-norsteroids by recombinant human aromatase (GENTEST Human CYP19 + P450 Reductase SUPERSOMES™). C19 androgens served as positive controls. Substrates and authentic aromatic A-ring (estrogenic) products, obtained by chemical synthesis, were separated by isocratic elution on HPLC employing appropriate solvent systems (Table 1). We also investigated the functional activity of the authentic estrogenic products, obtained by chemical synthesis, both binding to recombinant human estrogen receptors (ER) α and β and potency in transactivation of an estrogen-responsive reporter plasmid, 3XERE-luciferase, in T47Dco human breast cancer cells. Under conditions which allowed complete aromatization of the C19 androgens T and AD, we found no evidence for aromatization of DMA, 11β-MNT, or the 19-norsteroid, norethindrone (NET). Conversion of the other 19-norandrogens tested, 7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone (MENT) and 19-nortestosterone (19-NT) proceeded slowly and inefficiently. Thus, aromatization of androgenic substrates by recombinant human aromatase is partially impeded by the lack of a C19-methyl group and completely impeded by a methyl group at the 11β position.

Table 1.

HPLC conditions for separation of substrates and potential aromatic A-ring (estrogenic) products of the SUPERSOMES™ reaction mixtures

| Substrate | Retention time (min) | Potential product | Retention time (min) | Column | Solvent system |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C19 Androgens | |||||

| Testosterone | ∼34.7 | 17β-Estradiol | ∼31.3 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | dH2O:ACN:MeOHa 60:30:10 |

| Androstenedione | ∼13.2 | Estrone | ∼14.8 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | MeOH:dH2O, 65:35 |

| 16α-Hydroxyandrostenedione | ∼13.3 | 16α-Hydroxyestrone | ∼10.7 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | dH2O:ACN:MeOH, 45:10:45 |

| 17α-Methyltestosterone | ∼15.7 | 17α-Methylestradiol | ∼11.6 | Luna 5 μm Phenyl-Hexyl | MeOH:10 mM KPO4, pH 3.0, 70:30 |

| 19-Norsteroids | |||||

| 19-Nortestosterone | ∼25.5 | 17β-Estradiol | ∼31.8 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | dH2O:ACN:MeOH, 60:30:10 |

| 7α-Methyl-19-nortestosterone (MENT) | ∼27.5 | 7α-Methylestradiol | ∼33.5 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | dH2O:ACN:MeOH, 55:30:15 pH 3.0 |

| 11β-Methyl-19-nortestosterone | ∼27.9 | 11β-Methylestradiol | ∼30.7 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | dH2O:ACN:MeOH, 55:30:15 pH 3.0 |

| 7α,11β-Dimethyl-19-nortestosterone (DMA) | ∼26.6 | 7α,11β-Dimethylestradiol | ∼31.4 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | dH2O:ACN:MeOH, 55:35:10 |

| 17α-Ethinyl-19-nortestosterone (norethindrone) | ∼23.8 | 17α-Ethinylestradiol | ∼27.5 | Luna 5 μm C18(2) | MeOH:dH2O, 60:40 |

Abbreviations: dH2O, deionized water; ACN, acetonitrile; MeOH, methanol.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Chemicals

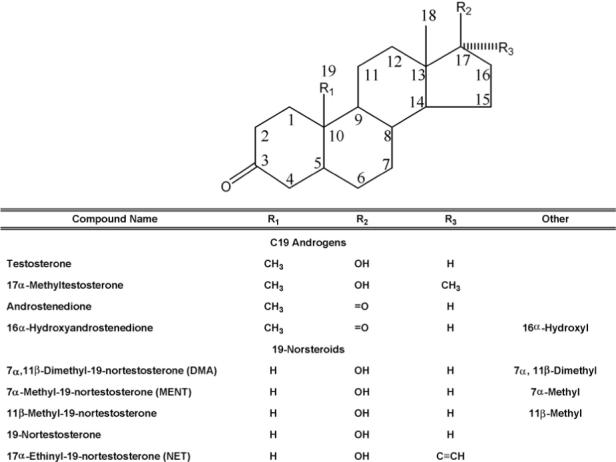

Testosterone, 17β-estradiol, estrone, ethinylestradiol (EE), androstenedione, 19-nortestosterone, 16α-hydroxyandrostenedione (16α-OHAD), and 16α-hydroxyestrone (16α-OHE1) were purchased from Steraloids (Newport, RI), and 17α-methyltestosterone (17α-MT), from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Norethindrone was obtained from Syntex Corp., and 11β-methylestradiol (11β-ME), from G.D. Searle & Co. (Chicago, IL). Dimethandrolone (CDB-1321: 7α,11β-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone), 7α,11β-dimethylestradiol (7α,11β-DME), 7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone, 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone (11β-MNT), 17α-methylestradiol (17α-ME), and 7α-methylestradiol (7α-ME) were synthesized by the Southwest Foundation for Biomedical Research, San Antonio, TX, under contract NO1-HD-6−3255, Dr. P.N. Rao, PI, and were 98−100% pure by HPLC and NMR. Fig. 1 depicts the structure of the C19 androgens and 19-norsteroids used in these experiments. Letrozole (Femara™, CGS 20267) was a gift of Novartis Pharma (Summit, NJ). Solvents were HPLC grade. Methanol was obtained from Sigma or Burdick and Jackson (Honeywell Int. Inc., Muskegon, MI) and acetonitrile (ACN), from Burdick and Jackson.

Fig. 1.

Structures of the C19 androgens and 19-norsteroids used in this study.

2.2. SUPERSOMES™ incubation mixtures

C19 androgens or 19-norsteroids (50 μM) were incubated with GENTEST Human CYP19 + P450 Reductase SUPERSOMES™ (0.1 μM) following the manufacturer's protocol (BD Biosciences, Woburn, MA) unless otherwise specified. All steroids appeared to be soluble at this concentration in the incubation mixtures. Reaction mixtures contained an NADPH regenerating system consisting of 1.3 mM NADP+, 3.3 mM glucose-6-phosphate, and 0.4 U/ml glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (or 5 mM NADPH), and 3.3 mM MgCl2 in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4. After incubation for various times at 37 °C, reactions were stopped by the addition of one-half volume ACN and centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 3 min. The supernatant was removed, and 50 μl was injected into the HPLC column.

2.3. Detection by HPLC

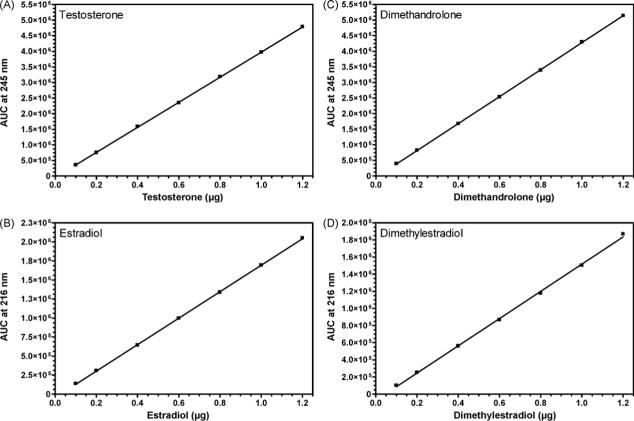

For each substrate/hypothetical aromatic A-ring product pair, a suitable solvent system was developed to provide a clear separation of retention times for authentic standards using a Waters Corp. (Milford, MA) HPLC system (composed of a Waters 600E system controller, a Waters 2487 dual wavelength absorbance detector, a Waters 717 plus autosampler, and a Waters in-line degasser). For method development, authentic substrate/product pairs were chromatographed on a Phenomenex Luna® 5 μm C-18 column (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) with the exception of 17α-MT/17α-ME which were separated on a Phenomenex Luna® 5 μm phenyl-hexyl column. Table 1 summarizes the solvent systems utilized for each substrate/product pair. Peaks of C19 androgens or 19-norsteroids were monitored by UV absorbance at 245 nm, and their putative aromatic A-ring products, by UV absorbance at 216 nm. UV peaks at a specified retention time were integrated and expressed as absorbance units (AU) using Waters Empower™ software. For quantification of the amount of substrate converted or the amount of product formed, standard curves were constructed according to the manufacturer's instructions. Representative standard curves for T/E2 and DMA/7α,11β-DME are illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Standard curves for quantification of (A) testosterone, (B) estradiol, (C) dimethandrolone, and (D) 7α,11β-dimethylestradiol by HPLC. Various volumes (10−50 μl) of solutions containing a mixture of T and E2 standards (A and B) or DMA and 7α,11β-DME standards (C and D), each at 2 or 20 μg/ml, were injected (final amount injected 0.02−0.80 μg) into a Luna 5 μm C18(2) column and eluted isocratically (Table 1). AU's at 245 nm for the peaks of T at ∼35 min or DMA at ∼27 min (Table 1) and at 216 nm for the peaks of E2 and 7α,11β-DME at 31−32 min were determined by the Waters Empower™ software and plotted vs. the amount of steroid applied to the column. Amounts (μg) of substrate and product present following incubation of T or DMA with SUPERSOMES™ for various times were calculated from the standard curves. Similar methodology was used to prepare standard curves for all other substrates and hypothetical aromatic A-ring products.

2.4. Binding assay for ERα and ERβ

Purified recombinant human ERα and ERβ1-long form were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). ER (0.45 pmol/well) were incubated with 10 nM 6,7- or 2,4,6,7-[3H]E2 (40−100 Ci/mmol; Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) in 10 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 10% glycerol, 1 mg/ml ovalbumin, and 2 mM DTT in the absence or presence of 2 μM E2 to measure total or nonspecific binding, respectively. Unlabeled competitors were added at concentrations from 0.5 to 10,000 nM and the mixtures incubated at 4 °C overnight. [3H]E2-ER complexes were separated from unbound radioligand by addition of 50% hydroxylapatite, filtration, and washing. Receptor-bound cpm were determined in a scintillation counter and entered into Packard's RIASmart™ (Perkin-Elmer) for calculation of IC50's using a 4-parameter logistic curve fit.

2.5. Transcription assays

Cell culture reagents were obtained from GIBCO Invitrogen Corp. The T47Dco cell line which possesses endogenous ER as well as progestin receptors was generously provided by Dr. Kathryn Horwitz (UCHSC, Denver, CO). For transient transfection experiments, cells were plated in 6-well dishes in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented with 10% dextran-coated charcoal-stripped (DCC-stripped) fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone Laboratories, Inc., Logan, UT), 10 U/ml penicillin G, and 10 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. Cells were transfected with 3XERE-LUC, a reporter plasmid containing three copies of an estrogen response element (ERE) upstream of the firefly luciferase (LUC) gene (a gift of Dr. Donald McDonnell, Duke University, Durham, NC) using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) as described previously [3,15]. Data were expressed as relative light units (RLU) normalized for differences in protein content per well.

3. Results

3.1. Estrogenic activity of the hypothetical aromatic A-ring products of the aromatase reaction

In order to have an indication of the estrogenic potency of the hypothetical aromatic A-ring products of the reaction of various C19 androgens or 19-norandrogens with SUPERSOMES™, we assessed the activity of chemically synthesized standards in in vitro assays: competition of the unlabeled standards with [3H]E2 for binding to human recombinant ERα and ERβ and determination of the EC50's for transactivation of 3XERE-LUC in T47Dco cells. As shown in Table 2, the potential aromatic A-ring products, with the exception of E1, bound with high affinity to both ERα and ERβ under the conditions of this assay. The relative binding affinities (RBA's) of 17α-ME, 7α,11β-DME, 7α-ME,11β-ME, and EE for ERα were 70−100% that of the E2 standard (arbitrarily set at 100%) with slight differences observed in the RBA's for the two types of ER for EE and 17α-ME. E1 bound to ERα and ERβ1-long form with much lower affinity (RBA's of 8% and 5% compared to E2, respectively). The RBA's of the androgens (T, 17α-MT, DMA, and MENT) for ERα or ERβ1-long form were <1% that of E2 (IC50's > 1000 nM; data not shown). The potential aromatic A-ring products were very potent in transactivation of 3XERELUC in T47Dco cells (EC50's ≈ 4.4−17.6 pM) with E1 again showing the weakest activity (EC50 = 40.5 pM). The order of potency was 7α-ME ≈ 11β-ME > 17α-ME ≈ 7α,11β-DME > EE ≈ E2 > E1 (Table 3). Some of the androgenic substrates (e.g. T, AD, DMA, MENT) employed in the reaction with human aromatase showed transactivation of 3XERE-LUC in T47Dco cells at concentrations of 10−8 M or greater (data not shown). Whether this low level of transactivation is inherent to the androgens or due to their conversion to metabolites with estrogenic activity in T47Dco cells is currently under investigation.

Table 2.

Binding of the hypothetical aromatic A-ring productsa to recombinant human ERα and ERβ

| Substrate/product pair | ERα |

ERβ |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 (nM) | RBAb (%) | IC50 (nM) | RBAb (%) | |

| Testosterone/estradiol; 19-Nortestosterone/estradiol | 5.2 ± 0.4 | 100c | 5.2 ± 0.3 | 100c |

| Androstenedione/estrone | 69.2 ± 34.5 | 8 | 105.3 ± 33.0 | 5 |

| 17α-Methyltestosterone/17α-methylestradiol | 7.4 ± 0.9 | 70 | 11.9 ± 0.4 | 44 |

| 7α,11β-Dimethyl-19-nortestosterone/7α,11β-dimethylestradiol | 5.7 ± 0.9 | 91 | 5.8 ± 0.9 | 90 |

| 7α-Methyl-19-nortestosterone/7α-methylestradiol | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 102 | 5.1 ± 1.0 | 102 |

| 11β-Methyl-19-nortestosterone/11β-methylestradiol | 4.9 ± 0.9 | 106 | 5.6 ± 0.8 | 93 |

| Norethindrone/17α-ethinylestradiol | 5.3 ± 1.3 | 98 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 51 |

Values represent the mean ± S.E. of 3−19 determinations.

Standards synthesized chemically.

RBA: Relative binding affinity: IC50 estradiol/IC50 test compound × 100.

Defined.

Table 3.

Transactivation of 3XERE-LUC in T47Dco cells by the hypothetical aromatic A-ring productsa

| Substrate/product pair | EC50 (pM) |

|---|---|

| Testosterone/estradiol; 19-Nortestosterone/estradiol | 17.6 ± 7.6 |

| Androstenedione/estrone | 40.5 ± 26.2 |

| 17α-Methyltestosterone/17α-methylestradiol | 12.9 ± 3.1 |

| 7α,11β-Dimethyl-19-nortestosterone/7α,11β-dimethylestradiol | 13.3 ± 6.6 |

| 7α-Methyl-19-nortestosterone/7α-methylestradiol | 4.4 ± 1.7 |

| 11β-Methyl-19-nortestosterone/11β-methylestradiol | 4.8 ± 1.5 |

| Norethindrone/17α-ethinylestradiol | 17.2 ± 9.4 |

Values represent the mean ±S.E. of 3−5 determinations or the mean ±S.D. of 2 determinations (estrone).

Standards synthesized chemically.

3.2. Aromatization of T and other C19 androgens

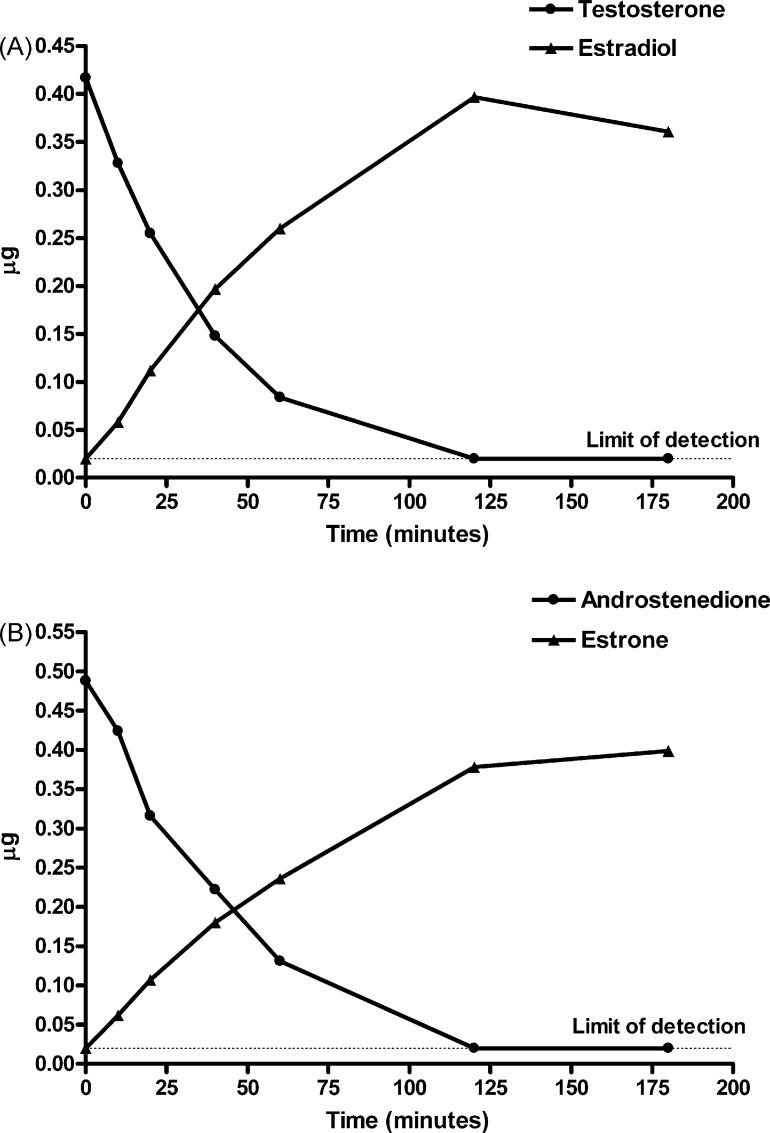

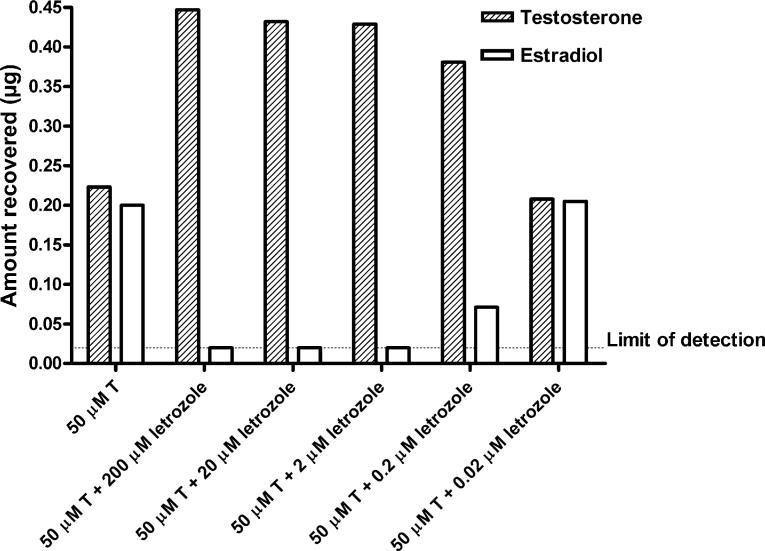

It was necessary to have a chemically synthesized aromatic A-ring standard corresponding to each androgen tested to develop suitable separation conditions for each substrate/hypothetical product on HPLC as indicated in Table 1. Standard curves relating AU and quantity of the various compounds in μg were obtained for all substrates and hypothetical aromatic A-ring product pairs and were linear over the concentration range employed (0.02−0.8 or 1.2 μg). Thus, the limit of detection of this system was 20 ng. Representative standard curves constructed for T, E2, DMA, and 7α,11β-DME following injection of various amounts of 2 or 20 μg/ml solutions of the authentic standards into a Luna® 5 μm C18(2) HPLC column are shown in Fig. 2. Following incubation of the C19 androgens, T or AD, at 50 μM, with recombinant human aromatase according to the manufacturer's specifications, formation of product (E2 or E1, respectively) was approximately linear for 40−60 min (Fig. 3). About 65−70% of T or AD was converted to estrogenic product by 60 min, and by 120 min, the reaction was complete as the substrate was no longer detectable (<20 ng). Letrozole blocked aromatization of T by SUPERSOMES™ in a concentration-dependent manner after a 60 min incubation (Fig. 4). At concentrations of 200, 20, or 2 μM letrozole, there was no detectable E2 formed from 50 μM T as substrate, whereas conversion was 16% at 0.2 μM letrozole and 50% at 0.02 μM. The latter was comparable to the 47% conversion of T observed at 60 min in the absence of letrozole in this experiment (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

Time course of conversion of testosterone to estradiol (A) or androstenedione to estrone (B) after incubation with GENTEST Human CYP19 + P450 SUPERSOMES™ and analysis by HPLC under the conditions specified in Table 1. The limit of detection was 20 ng.

Fig. 4.

Effect of various concentrations of letrozole on conversion of testosterone to estradiol following incubation with SUPERSOMES™ for 60 min. The limit of detection was 20 ng.

Aromatization of two other C19 androgens, 16α-OHAD and 17α-MT, was also investigated. Conversion of 16α-OHAD to 16α-E1 was linear with time of incubation for at least 60 min and then leveled off between 120 and 180 min (data not shown). The percent conversion of the substrate was about 30% at 60 min, 52% at 120 min, and 63% at 180 min. Separation of 17α-MT and 17α-ME could not be achieved using the Luna® 5 μm C18(2) HPLC column and various concentrations of deionized water, ACN, and methanol which had been successful for all other substrate/product pairs. Therefore, for this separation we employed a Phenomenex Luna® 5 μm phenylhexyl column and isocratic elution with 70% methanol:30% 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 3.0 (Table 1). Formation of the product was not detectable until 40 min, and it proceeded linearly thereafter to 150 min (data not shown). At this time, approximately 35% of the substrate was converted to 17α-ME. It is possible that steric hindrance by the 17α-methyl group reduced the rate of aromatization of 17α-MT. Initially, we followed the manufacturer's suggested protocol for preparation of the reaction mixtures which involved using 50 μM substrate, 100 pmol/ml human CYP19 + P450 Reductase SUPERSOMES™, and an NADP+ regenerating system. In subsequent experiments, we substituted crystalline NADPH as cofactor (final concentration, 5 mM, an excess of 100-fold compared to the substrate concentration) instead of the NADP+ regenerating system following the suggestion of Dr. de Gooyer (personal communication). The fractional conversion of T to E2 or 17α-MT to 17α-ME was very similar with either cofactor.

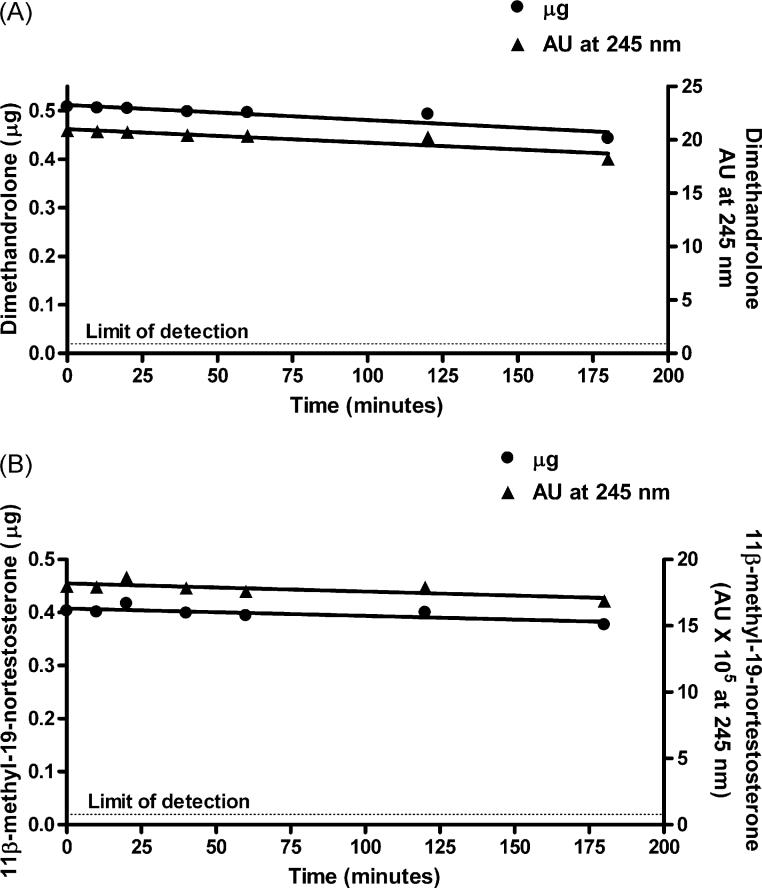

3.3. Possible aromatization of DMA, 11β-MNT, and other 19-norsteroids

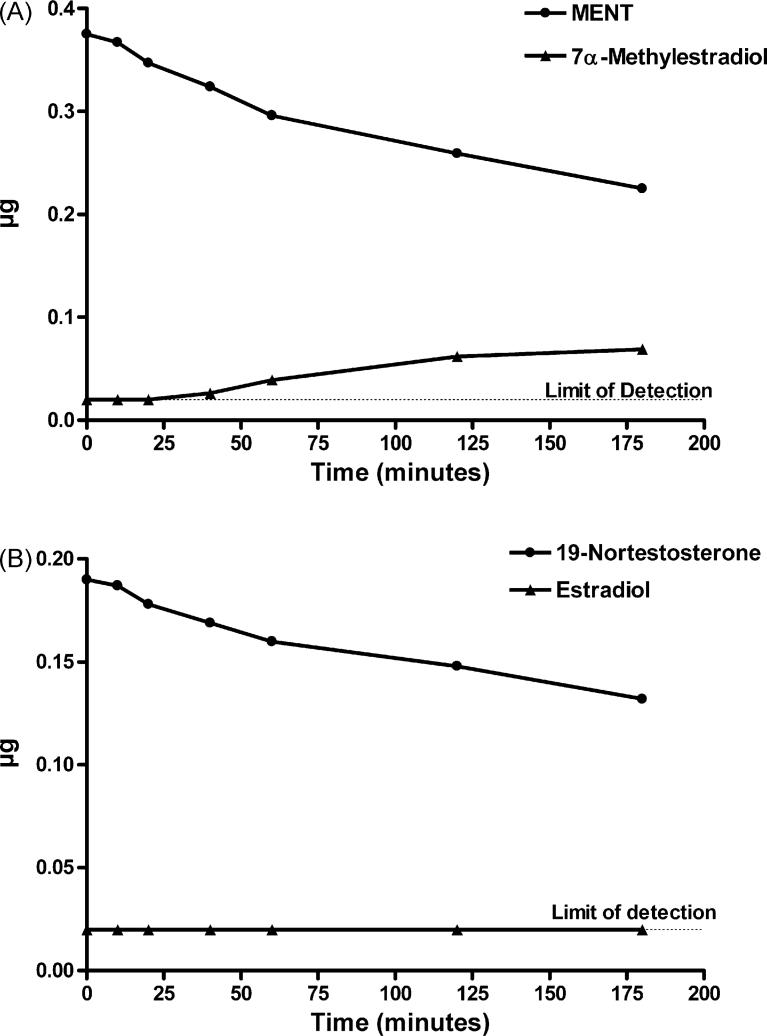

As shown in Fig. 5, under the same incubation conditions spec-ified above for demonstration of aromatization of C19 androgens, there was no detectable change in the amount of DMA or 11β-MNT after incubation with SUPERSOMES for up to 180 min (expressed either as AU at 245 nm or μg), and the hypothetical aromatic A-ring products were not detected. Each of these steroids was incubated with different batches of SUPERSOMES using an NADP+ regeneration system or crystalline NADPH and analyzed by HPLC in 2−4 independent experiments with the same result. In the case of MENT and 19-NT, the amount of substrate decreased slightly with increasing incubation times, and small peaks corresponding to the hypothetical aromatic A-ring products, 7α-ME and E2, respectively, were first detected at 40 min (7α-ME) or 120 min (E2)(Fig. 6). At 180 min, about 23% of MENT was converted to 7α-ME and about 13% of 19-NT to E2. In agreement with de Gooyer et al. [5], we found no evidence for the aromatization of the 19-norprogestin NET to 17α-EE (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Amount of substrate (μg) in reaction mixtures after various times of incubation of dimethandrolone (A) or 11β-methyl-19-nortestosterone (B) with SUPERSOMES™ and analysis by HPLC under the conditions specified in Table 1. The limit of detection was 20 ng.

Fig. 6.

Time course of conversion of MENT to 7α-methylestradiol (A) and of 19-nortestosterone to estradiol (B) after incubation with SUPERSOMES™ and analysis by HPLC under the conditions specified in Table 1. In (B) estradiol was undetectable (<20 ng) at 0, 10, 20, 40, and 60 min and equivalent to 20 ng at 120 and 180 min.

4. Discussion

In these experiments, we demonstrated substantial conversion, by recombinant human aromatase, of the C19 androgens, T, AD, 16α-OHAD, and 17α-MT at 50 μM, to their respective aromatic A-ring products, E2, E1, 16α-OH E1, and 17α-ME. Aromatization of T to E2 or AD to E1 was linear for 40−60 min, and complete conversion was observed by 120 min. Letrozole blocked aromatization of T to E2 in a concentration-dependent manner. There was a small reduction, with increasing incubation times, in the amount of material in the peaks of MENT and 19-NT on HPLC when these 19-norandrogens were used as substrates for aromatase, and small peaks corresponding to the hypothetical products, 7α-ME and E2, appeared after incubation times of 40 min or 120 min, respectively. Thus, the reaction of MENT and 19-NT with recombinant human aromatase in vitro was slow and inefficient, due presumably to the lack of the C19-methyl group which is the site of attack by oxygen [4]. Under the same incubation conditions, there was no detectable aromatization of DMA and 11β-MNT, two synthetic androgens which are being developed for hormonal therapy in men, to their hypothetical aromatic A-ring products, 7α,11β-DME and 11β-ME, respectively, for up to 180 min, suggesting that the presence of a methyl group at the 11β-position inhibited the aromatization reaction. Likewise, de Gooyer and his colleagues (M. de Gooyer, personal communication) concluded that 11β-substituted 19-norandrogens could not be aromatized. The 19-norsteroid NET was also not aromatized under our conditions, confirming the findings of de Gooyer et al. [5].

Contradictory reports have appeared in the literature concerning aromatization of 19-norandrogens which lack the C19-methyl group. Thus, published findings have claimed that aromatization of 19-norandrogens is both possible [11–14] or not possible [7–10] using various in vitro systems including placental microsomes and granulosa or Leydig cells. Previous publications describing a variety of aromatase preparations and detection methods suggested that both MENT and 19-NT could be aromatized. LaMorte et al. [13] reported aromatization of MENT in vitro using microsomes from human placenta as the source of aromatase and TLC to separate the reaction products. De Gooyer et al. [5] used a preparation of recombinant human aromatase similar to that used here to examine aromatization of T, 17α-MT, MENT, and 19-NT. Products with estrogenic activity were detected by transactivation assays mediated by ERα and ERβ in Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells, and the formation of phenolic A-ring metabolites was confirmed by LC-MSMS. They claimed complete conversion of these substrates at 1 μM within about 15 min; however, they also reported that the 19-norsteroids, especially 19-NT, were less “susceptible” to aromatization than the C19-methylated steroids, in keeping with our observation that aromatization of MENT and 19-NT proceeded slowly. The difference between the results of de Gooyer et al. [5] and ours for 19-norandrogens did not appear to be due to different substrate concentrations, to the use of an NADPH regenerating system vs. crystalline NADPH, or to the greater sensitivity of their detection systems as we observed complete aromatization of T and AD by 120 min under these conditions. Other 19-norsteroids as well as NET, e.g. tibolone [5] and its 3-keto-4-ene metabolite [16], do not undergo aromatization to estrogenic derivatives. Both of these compounds contain a 7α-methyl group: tibolone is the 7α-methyl derivative of 19-norethynodrel, and its 3-keto-4-ene metabolite is the 7α-methyl derivative of NET which has a similar delta-4-ene A-ring structure to that of AD [16]. DeGooyeretal. [5] concluded that the 17α-ethinyl group completely blocked aromatization of tibolone which may be the case for substituents at the 11β-position. The presence of a methyl group at the 17α-position, as in 17α-MT, may also hinder the aromatization reaction.

Collectively, these data support the notion that the C19-angular methyl group, which is the site of attack for the first and second hydroxylation reactions [4,6], is important for optimal formation of aromatic A-ring products by the human P450 aromatase enzyme system in vitro, and in its absence, the aromatization reaction proceeds slowly or not at all. Recently Hong et al. [6] described the molecular basis for the aromatization reaction by detailed structure–function analysis. Their scheme centered the C19-methyl group over the heme iron. Whereas various C19-steroids such as the aromatase inhibitor exemestane [6] and 17α-MT [17] produced a time-dependent decrease in aromatase activity, Covey and Hood found that compounds lacking the C19-methyl group did not act as aromatase inhibitors [18].

The chemically synthesized phenolic A-ring standards, representing potential products of aromatization of the androgens used in this study, bound to recombinant human ERα and ERβ with high affinity and exhibited potent estrogenic activity in vitro as assessed by transactivation of 3XERE-LUC (EC50's: 10−12 to 10−11 M). Estrone showed the lowest RBA and the highest EC50, and there was reasonable agreement between the EC50's for transactivation by the other estrogenic compounds and the RBA's for ER, especially ERα.Any discrepancies could be due to: (1) metabolism in the T47Dco cells or (2) differential transactivation mediated by ERα and ERβ as the relative amounts of these isoforms in T47Dco cells are unknown. In any case, if formed in vivo, the methylated estrogens would be expected to be at least as potent as E2.

Several of the androgenic substrates (i.e. T, AD, and MENT), as well as the chemically synthesized 5α-reduced derivatives of DMA and 11β-MNT, behave as weak estrogens in transactivation assays with 3XERE-LUC (B. Attardi, unpublished observations). It is not known whether this is due to weak activity intrinsic to the androgens or to their conversion to metabolites with estrogenic activity in T47Dco cells. Both synthetic 19-norandrogen derivatives [19,20] and non-phenolic metabolites formed in human breast cancer cells from androgenic substrates [21] have been shown to exhibit estrogenic activity. These compounds have reduced and hydroxylated A-rings; for example, T is metabolized to 5α-androstane-3α,17β-diol and its 3β-enantiomer in MCF-7 cells [21]. The basis for transactivation of 3XERE-LUC by selected androgens in T47Dco cells is being investigated further.

The major pathway for estrogen biosynthesis in vivo is through aromatization of C19 androgens [4]. Thus, in this study we examined the possible conversion of selected androgens to aromatic A-ring derivatives with estrogenic activity using recombinant human aromatase, a preparation devoid of other contaminating enzymatic activities such as would be found in intact cells or isolated microsomes. Another potential route for obtaining compounds with estrogenic activity from androgens or 19-norsteroids is through formation of non-phenolic androgen metabolites by 5α-reduction followed by hydroxylation of the A-ring [19–21].DMA and 11β-MNT are not likely to be converted to estrogens by this route either as they are not substrates for 5α-reductase [22]. The most decisive method to determine the metabolism of DMA and 11β-MNT in vivo would be to isolate and characterize all possible metabolites. This is beyond the scope of the present study, but would be carried out if these steroids continue in drug development. However, DMA has been tested in vivo for estrogenic activity in standard bioassays in the rat (Hild et al., unpublished observations). DMA administered sc to adult female ovariectomized rats (∼300 g) at a dose of 1 mg/rat/day for 7 days resulted in an increase in uterine weight; however, vaginal cornification, a specific indicator of estrogenic activity [23], was not induced in these same rats. Histological examination of uteri from immature female rats (∼45 g) treated orally with a high dose of DMA (11 mg/rat/day) indicated that the observed increase in uterine weight was due largely to an increase in myometrial tissue. The increase in uterine muscle mass is a typical androgenic response [24]. Taken together, the above results make it very unlikely that DMA and 11β-MNT are converted in vivo to compounds with estrogenic activity.

The desirability that an androgen to be used for hormone replacement therapy be aromatizable is uncertain as the role of E2 in aging men is not clear. Estrogens are produced in men in significant quantities by local tissue aromatization of androgen synthesized by testes and adrenal glands [25]. Administration of aromatizable androgens such as AD, which is used as a performance enhancing food additive, can lead to the development of gynecomastia, especially in face of lowered T production [26]. Furthermore, administration of C19 androgens such as T may be contraindicated in men with a history of breast tumors, polycythemia, or sleep apnea due to increased bioavailability of estrogens upon aromatization. Effects on bone, cognitive function, gonadotropin synthesis and secretion, the cardiovascular system, and prostate have been proposed, and benefits vs. risks must be evaluated. Dissection of the relative roles of androgens and estrogens with respect to these endpoints has been facilitated by various mutations in mice that disrupt the function of one or the other class of steroids. These include mice displaying androgen insensitivity or testicular feminization (Tfm) mutations, androgen receptor (ARKO) or estrogen receptor α or β knock-out (ERKO or BERKO, respectively) mice, and aromatase deficient mice.

The impact of T on bone results from signaling through both AR and ERα [27]. AR are present in bone cells, and T is critical for skeletal growth and maintenance. Whereas induction of epiphy-seal closure by androgens at the end of puberty clearly depends on aromatization to estrogens and interaction with ERα, androgens may protect men against osteoporosis via a dual mechanism mediated by both AR and ERα [27]. E2 may also have positive effects on bone, reducing the risk of osteoporosis [28] and preventing fractures [29]. However, it has been established, at least in rodents, that androgen action on bone can be directly mediated by activation of AR in the absence of ER [30,31]. In addition, findings from individuals with androgen insensitivity syndrome suggest that androgens play an important role in normal male growth and maintenance of bone density which cannot be filled by estrogens [32,33].On the other hand, a recent clinical review concerning the impact of T therapy on bone health [34] concluded that the available trials do not provide convincing evidence for the efficacy of T in preventing and treating osteoporosis, and that further data on fractures need to be accumulated. As for the impact of 19-norandrogens on bone, MENT prevented the decreases in cortical and trabecular bone mineral density associated with orchidectomy in aged male rats [35], whereas effects of DMA and 11β-MNT on bone mineral density have yet to be assessed.

The role of estrogens in maintaining health of the cardiovascular system in men needs further follow-up. A recent review article concluded that “estrogens may either not influence or may promote the development of coronary artery disease” in men based on the majority of both epidemiological and interventional studies [36].As concerns regulation of hypothalamic GnRH content and LH secretion in male rodents, studies employing ERKO mice showed that androgens play the primary physiological role in the male mouse [37,38]. BERKO mice showed delayed ejaculatory behavior, but ERβ does not appear to play a role in regulation of the HPG axis [39]. On the other hand, levels of the gonadotropin subunit mRNA's are regulated by both androgens and estrogens [37,38].

Another potential target of estrogens in men is the prostate which contains both ERα (stroma) and ERβ (epithelium). Whereas the physiological role of these receptors is not known, they may contribute to mediation of estrogen's role in prostate carcinogen-esis and progression of prostate cancer [40,41]. Thus, prolonged treatment of adult rodents with estrogens together with low-dose T leads to the development of epithelial metaplasia and adenocarcinoma of the prostate [40]. Also on the negative side, estrogens may actually facilitate the development of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: for men ages 70−91, various dementias have been associated with high levels of endogenous estrogen, but not of T [42]. Collectively, the majority of current evidence indicates that many of the beneficial effects of therapeutic androgens are mediated by AR and that formation of estrogens through aromatization may actually be a disadvantage. Thus, whether the benefits of administering an aromatizable androgen for hormonal therapy in men outweigh the risks will have to be assessed on a continuing basis before a final evaluation can be made.

In summary, conditions have been developed to demonstrate complete conversion of C19-methyl androgens to their aromatic A-ring products by incubation with recombinant human aromatase followed by separation by HPLC. Under these conditions, we were unable to detect aromatization of DMA and 11β-MNT, two synthetic 19-norandrogens in development for hormonal therapy in men. Thus, nonaromatizable androgens such as DMA or 11β-MNT may be useful for hormonal therapy in hypogonadal or aging men pending favorable results in safety studies.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Richard Blye of the Contraception and Reproductive Health Branch of NICHD for his input into the design of these studies and for his continued support, Margaret Krol and Emily Hua for excellent technical assistance, and Dr. Sailaja Koduri for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by contract NIH NO1-HD-2-3338 awarded to BIOQUAL, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This article appeared in a journal published by Elsevier. The attached copy is furnished to the author for internal non-commercial research and education use, including for instruction at the authors institution and sharing with colleagues. Other uses, including reproduction and distribution, or selling or licensing copies, or posting to personal, institutional or third party websites are prohibited. In most cases authors are permitted to post their version of the article (e.g. in Word or Tex form) to their personal website or institutional repository. Authors requiring further information regarding Elsevier's archiving and manuscript policies are encouraged to visit: http://www.elsevier.com/copyright

This work was presented in preliminary form at the 87th Annual Meeting of The Endocrine Society, San Diego, CA, June, 2005.

References

- 1.Byrne MM, Nieschlag E. Testosterone replacement therapy in male hypogonadism. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2003;26:481–489. doi: 10.1007/BF03345206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oettel M. The endocrine pharmacology of testosterone therapy in men. Naturwissenschaften. 2004;91:66–76. doi: 10.1007/s00114-003-0494-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Attardi BJ, Hild SA, Reel JR. Dimethandrolone undecanoate: a new potent orally active androgen with progestational activity. Endocrinology. 2006;147:3016–3026. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simpson ER, Mahendroo MS, Means GD, Kilgore MW, Hinshelwood MM, Graham-Lorence S, Amarneh B, Ito Y, Fisher CR, Michael MD, Mendelson CR, Bulun SE. Aromatase cytochrome P450, the enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis. Endocrine Rev. 1994;15:342–355. doi: 10.1210/edrv-15-3-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Gooyer ME, Oppers-Tiemissen HM, Leysen D, Verheul HAM, Kloosterboer HJ. Tibolone is not converted by human aromatase to 7α-methyl-17α-ethynylestradiol (7α-MEE): Analyses with sensitive bioassays for estrogens and androgens and with LC-MSMS. Steroids. 2003;68:235–243. doi: 10.1016/s0039-128x(02)00184-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hong Y, Yu B, Sherman M, Yuan Y-C, Zhou D, Chen S. Molecular basis for the aromatization reaction and exemestane-mediated irreversible inhibition of human aromatase. Mol. Endocrinol. 2007;21:401–414. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan L, Muto N. Purification and reconstitution of human placental aromatase A cytochrome P-450-type monooxygenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1986;156:243–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1986.tb09574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Silberzahn P, Gaillard JL, Quincey D, Dintinger T, Al-Timimi I. Aromatization of testosterone and 19-nortestosterone by a single enzyme from equine testicular microsomes: differences from human placental microsomes. J. Steroid Biochem. 1988;29:119–125. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(88)90385-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dintinger T, Gaillard JL, Moslemi S, Zwain I, Silberzahn P. Androgen and 19-norandrogen aromatization by equine and human placental microsomes. J. Steroid Biochem. 1989;33:949–954. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Amri H, Gaillard JL, Al-Timimi I, Zilberzahn P. Equine ovarian aromatase: evidence for a species specificity. Biochem. Cell Biol. 1993;71:296–302. doi: 10.1139/o93-044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khalil MW, Chung N, Morley P, Glasier MA, Armstrong DT. Formation and metabolism of 5(10)-estrene-3 beta, 17 beta-diol, a novel 19-norandrogen produced by porcine granulosa cells from C19 aromatizable androgens. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;155:144–150. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81061-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raeside JL, Renaud RL, Friendship RM. Aromatization of 19-norandrogens by porcine Leydig cells. J. Steroid Biochem. 1989;32:729–735. doi: 10.1016/0022-4731(89)90520-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.LaMorte A, Kumar N, Bardin CW, Sundaram K. Aromatization of 7-alpha-methyl-19-nortestosterone by human placental microsomes in vitro. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1994;48:297–304. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(94)90160-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundaram K, Kumar N, Monder C, Bardin CW. Different patterns of metabolism determine the relative anabolic activity of 19-norandrogens. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1995;53:253–257. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(95)00056-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Attardi BJ, Burgenson J, Hild SA, Reel JR. In vitro antiprogestational/antiglucocorticoid activity and progestin and glucocorticoid receptor binding of the putative metabolites and synthetic derivatives of CDB-2914, CDB-4124, and mifepristone. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;88:277–288. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2003.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raobaikady B, Parsons MFC, Reed MJ, Purohit A. Lack of aromatisation of the 3-keto-4-ene metabolite of tibolone to an estrogenic derivative. Steroids. 2006;71:639–646. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2006.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mor G, Eliza M, Song J, Wiita B, Chen S, Naftolin F. 17α-Methyl testosterone is a competitive inhibitor of aromatase activity in Jar choriocarcinoma cells and macrophage-like THP-1 cells in culture. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2001;79:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(01)00162-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Covey DF, Hood WF. Enzyme-generated intermediates derived from 4-androstene-3,6,17-trione and 1,4,6-androstatriene-3,17-dione cause a time-dependent decrease in human placental aromatase activity. Endocrinology. 1981;108:1597–1599. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-4-1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larrea F, Garcia-Becerra R, Lemus AE, Garcia GA, Perez-Palacios G, Jackson KJ, Coleman KM, Dace R, Smith CL, Cooney AJ. A-ring reduced metabolites of 19-nor synthetic progestins as subtype selective agonists for ER alpha. Endocrinology. 2001;142:3791–3799. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.9.8401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Becerra R, Borja-Cacho E, Cooney AJ, Smith CL, Lemus AE, Perez-Palacios G, Larrea F. Synthetic 19-nortestosterone derivatives as estrogen receptor alpha subtype-selective ligands induce similar receptor conformational changes and steroid receptor coactivator recruitment than natural estrogens. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2006;99:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perez-Palacios G, Santillian R, Garcia-Becerra R, Borja-Cacho E, Larrea F, Damian-Matsumura P, Gonzalez L, Lemus AE. Enhanced formation of non-phenolic androgen metabolites with intrinsic oestrogen-like gene transactivation potency in human breast cancer cells: a distinctive metabolic pattern. J. Endocrinol. 2006;190:805–818. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attardi BJ, Hild SA, Koduri S, Pham T, Pessaint L, Engbring J, Till B, Gropp D, Semon A, Reel JR. Dimethandrolone (DMA: 7α,11β-dimethyl-19-nortestosterone) does not require 5α-reduction to exert its maximal biological effects. Program of the 89th Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society; Toronto, Canada. 2007; (Abstract P3−399) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reel JR, Lamb JC, IV, Neal BH. Survey and assessment of mammalian estrogen biological assays for hazard characterization. Fund. Appl. Toxicol. 1996;34:288–305. doi: 10.1006/faat.1996.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hershberger LG, Shipley EG, Meyer RK. Myotrophic activity of 19-nortestosterone and other steroids determined by modified levator ani muscle method. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1953;83:175–180. doi: 10.3181/00379727-83-20301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sudhir K, Komesaroff PA. Cardiovascular actions of estrogens in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1999;84:3411–3415. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.10.5954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson D, Carter J. Drug-induced gynecomastia. Pharmacotherapy. 1993;13:37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vanderschueren D, Vandenput L, Boonen S, Lindberg MK, Bouillon R, Ohlsson C. Androgens and bone. Endocrine Rev. 2004;25:389–425. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Szulc P, Munoz F, Claustrat B, Garnero P, Marchand F, Duboeuf F, Delmas PD. Bioavailable estradiol may be an important determinant of osteoporosis in men: the MINOS study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2001;86:192–199. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amin S. Low estradiol levels linked to low-trauma hip fractures in men. Am. J. Med. 2006;119:426–433. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawano H, Sato T, Yamada T, Matsumoto T, Sekine K, Watanabe T, Nakamura T, Fukuda T, Yoshimura K, Yoshizawa T, Aihara K, Yamamoto Y, Nakamichi Y, Metzger D, Chambon P, Nakamura K, Kawaguchi H, Kato S. Suppressive function of androgen receptor in bone resorption. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:9416–9421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1533500100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vandenput L, Swinnen JV, Boonen S, Van Herck E, Erben RG, Bouillon R, Vanderschueren D. Role of the androgen receptor in skeletal homeostasis: the androgen-resistant testicular feminized male mouse model. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2004;19:1462–1470. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.040505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Danilovic DL, Correa PH, Costa EM, Melo KF, Mendonca BB, Arnhold IJ. Height and bone mineral density in androgen insensitivity syndrome with mutations in the androgen receptor gene. Osteoporosis Int. 2007;18:369–374. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0243-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sobel V, Schwartz B, Zhu YS, Cordero JJ, Imperato-McGinley J. Bone mineral density in the complete androgen insensitivity and 5alpha-reductase-2 deficiency syndromes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:3017–3023. doi: 10.1210/jc.2005-2809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tracz MJ, Sideras K, Bolona ER, Haddad RM, Kennedy CC, Uraga MV, Caples SM, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Testosterone use in men and its effects on bone health. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2006;91:2011–2016. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venken K, Boonen S, Van Herck E, Vandenput L, Kumar N, Sitruk-Ware R, Sundaram K, Bouillon R, Vanderschueren D. Bone and muscle protective potential of the prostate-sparing synthetic androgen 7α-methyl-19-nortestosterone: evidence from the aged orchidectomized male rat model. Bone. 2005;36:663–670. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wranicz JK, Cygankiewicz I, Kula P, Walczak-Jeedrzejowska R, Sllowikowska-Hilczer J, Kula K. Cardiovascular and metabolic effects of estrogen in men. Archives Med. Sci. 2006;4:221–225. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lindzey J, Wetsel WC, Couse JF, Stoker T, Cooper R, Korach KS. Effects of castration and chronic steroid treatments on hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone content and pituitary gonadotropins in male wild-type and estrogen receptor-alpha knockout mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4092–4101. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wersinger SR, Haisenleder DJ, Lubahn DB, Rissman EF. Steroid feedback on gonadotropin release and pituitary gonadotropin subunit mRNA in mice lacking a functional estrogen receptor alpha. Endocrine. 1999;11:137–143. doi: 10.1385/ENDO:11:2:137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Temple JL, Scordalakes EM, Bodo C, Gustafsson JA, Rissman EF. Lack of functional estrogen receptor beta gene disrupts pubertal male sexual behavior. Horm. Behav. 2003;44:427–434. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harkonen PL, Makela SI. Role of estrogens in development of prostate cancer. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2004;92:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2004.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bosland MC. The role of estrogens in prostate carcinogenesis: a rationale for chemoprevention. Rev. Urol. 2005;7:S4–S10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Geerlings MI. Endogenous sex hormones, cognitive decline, and future dementia in old men. Ann. Neurol. 2006;60:346–355. doi: 10.1002/ana.20918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]