Abstract

The present study considered the intergenerational consequences of experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage within the family of origin. Specifically, the influence of socioeconomic disadvantage experienced during adolescence on the timing of parenthood as well as the association between early parenthood and risk for harsh parenting and emerging child problem behavior was evaluated. Participants included 154 3-generation families, followed prospectively over a 12-year period. Results indicated that exposure to poverty during adolescence and not parents' (G1) education predicted an earlier age of parenthood in the second generation (G2). Younger G2 parents were observed to be harsher during interactions with their own 2-year old child (G3) and harsh parenting predicted increases in G3 children's externalizing problems from age 2 to age 3. Finally, G3 children's externalizing behavior measured at age 3 predicted increases in harsh parenting from age 3 to 4, suggesting that G3 children's behavior may exacerbate the longitudinal effects of socioeconomic disadvantage.

Although children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds are over identified in terms of rates of antisocial behaviors and emotional problems (e.g., McLoyd, 1998), little research has considered the consequences of economic disadvantage across multiple generations. Despite the lack of empirical research, the consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage likely extend beyond the immediate family to affect subsequent generations of family members (e.g., Brooks-Gunn & Duncan, 1997). For instance, adolescents residing in socioeconomically disadvantaged homes seem to be at increased risk for dropping out of school, engaging in risk-taking behavior, and entering parenthood at an early age (Hardy, et al., 1998; Pears, et al., 2005). The relationship between socioeconomic disadvantage in the family of origin and early parenthood is especially noteworthy inasmuch as an earlier age at first birth is associated with more hostile and less nurturing behavior by parents (Conger, et al., 1984).

Adding to the complexity of understanding the intergenerational consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage is actually defining the concept. Three different domains have been suggested to characterize socioeconomic status: income, education, and occupational status (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002; Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Hoff, Laursen, & Tardif, 2002; Oakes & Rossi, 2003). Socioeconomic disadvantage may consist of fewer years of formal education, low income, and low occupational status. Drawing on earlier findings, Conger and Donnellan (2007) argue that each dimension of socioeconomic status demonstrates different patterns of stability and differentially predicts family and child adjustment. Consequently, the selection of socioeconomic indicators depends on the research question under study. We focused on two components of socioeconomic disadvantage: education and poverty (i.e., dramatically low income). Education was defined by the number of years of formal education among the parent generation (G1) and poverty was defined as G1's average level of poverty during the second generation's adolescence (G2). Poverty status was selected as a marker of economic deprivation because families close to or below the poverty level are formally defined by government standards as being unable to meet their basic material, nutritional and medical needs (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). Families in this group clearly meet criteria to be classified as economically disadvantaged. This categorical measure serves the purposes of the present study more adequately than a continuous measure of income which has no clear breaking point for determining families with significant financial distress or disadvantage.

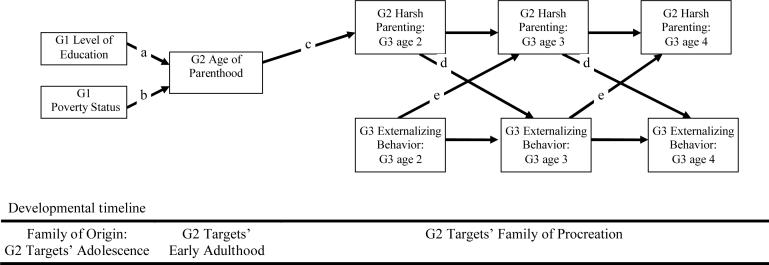

Using a cohort of adolescents (G2), we examined the association between socioeconomic disadvantage within families of origin and their developing relationships with their children (G3) during their early adult years (see Figure 1). Socioeconomic disadvantage, defined as less well educated and more impoverished G1 parents, was expected to predict an earlier G2 transition to parenthood. Early entry into parenthood was expected to be associated with greater reliance on harsh parenting because young parents may be less prepared to manage the demands of parenthood. Harsh parenting likely increases G3 children's risk for externalizing problems during the early childhood period, externalizing problems that further intensify harsh parenting.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized link in the conceptual model.

The Theoretical Model

Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Early Parenthood

Pregnancy and childbearing during the teenage years has been linked repeatedly to family difficulties including socioeconomic disadvantage, marital discord and divorce, harsh and inconsistent parenting, family conflict, and a history of mental health problems (Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Ellis, et al., 2007; Miller-Johnson, et al., 1999; Russell, 2002, Scaramella, Conger, Simons, & Whitbeck, 1998; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2001). While an abundance of research has examined causes and consequences of childbearing during the teenage years, individuals becoming parents during their early 20's are less often the focus of study. Interestingly, the average age of first birth for women has increased from 21.4 years of age in 1970 to 24.9 by 2000 (Sutton & Matthews, 2004). This increase in the national average for age at first birth also has given new meaning to the term “early parenthood.”

Jaffee (2002) argues that the timing of parenthood is not a random event. Compared to women who delayed childbearing until after the age of 26, both teenage mothers and women who became parents in their early 20's had significantly lower IQs, completed fewer years of school and were more likely to meet the criteria for conduct disorder and to reside in socioeconomically disadvantaged homes during childhood and adolescence (Jaffee, 2002; see also Hardy et. al, 1998). In other words, the same factors associated with increased risk of pregnancy during the teenage years also increased risk of pregnancy during the early adult years (i.e., ages 20−25). Thus, socioeconomic disadvantage within the family of origin was expected to be associated with an earlier age of parenthood for G2 participants (see Figure 1, paths a and b).

Childbearing Age and Child Externalizing Problems: The Role of Harsh Parenting

Theoretically, the age at which individuals become parents may indirectly affect children's risk for developing externalizing behavior problems by influencing the quality of parent-child relations (see Figure 1). Younger parents may be ill prepared to meet the demands of parenthood and may be more likely to use harsh parenting strategies when parenting demands exceed their abilities (see Figure 1, path c; e.g., Granic & Patterson, 2006; Scaramella & Conger, 2003). Parents' over-reliance on harsh parenting during the toddler years may socialize children to use angry, aggressive, externalizing behaviors during conflict situations with their parents and with others within and outside the family (e.g., Granic & Patterson, 2006; Patterson, Reid, & Dishion, 1992). Developmentally, the toddler period is noted for particularly high rates of externalizing behaviors; behaviors that typically decline from age 2 to 6 (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004). However, harsh parenting may interfere with normative declines in externalizing behaviors because such parenting teaches children that aggressive and demanding actions are largely effective in controlling the behaviors of other family members (Gilliom & Shaw, 2004).

In theory, the effect of parenting on children's behavior does not operate in one direction. Instead, a mutually influencing pattern may exist whereby high rates of externalizing problems also intensify harsh parenting over time as parents attempt to control the children's difficult behaviors by escalating aversive responses to these actions. As shown in Figure 1, this hypothesized mutually reinforcing relationship is expected to lead to an ongoing pattern of harsh and coercive parent-child interactions across time (Granic & Patterson, 2006; Scaramella & Leve, 2004). Consequently, harsh parenting is expected to predict increases in children's externalizing behaviors over time (see Figure 1, path d), which in turn are hypothesized to lead to increases in harsh parenting (see Figure 1, path e).

Empirical research generally supports these expectations. That is, younger compared to older mothers (e.g., Berlin, Brady-Smith, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002) and fathers (e.g., Fagot, et al., 1998) seem to be at greater risk for using harsh parenting during disciplinary situations with their children. Harsh parenting during early childhood also has been linked to higher levels of externalizing problems during childhood (e.g., Gilliom & Shaw, 2004; Keenan & Shaw, 1995; Marchand, Hock, & Widaman, 2002; Rubin, Burgess, Dwyer, & Hastings, 2003; Shaw & Bell, 1993). Fewer studies have evaluated the expectation that child externalizing behavior predicts harsh parenting during the early childhood period. Indeed, we found only one study that considered the effects of externalizing problems during early childhood on change in harsh parenting. Using a small sample of 4 to 6 year old children, Marchand, Hock, and Widaman (2002) found that children's externalizing behaviors at age 4 and 6 predicted increases in mothers' hostile parenting. Interestingly, child externalizing problems was a better predictor of harsh parenting than the reverse. Other research during adolescence indicates the expected reciprocal process between harsh parenting and children's problem behaviors (Stewart, Simons, & Conger, 2000); however, this work has yet to be replicated with younger children.

Summary of Study Hypotheses

The present study considers the intergenerational consequences of socioeconomic disadvantage during the adolescent years on the quality of emerging parent-child relations during the toddler and preschool years. G1 parents with fewer years of formal education (see Figure 1, path a) and who experienced more poverty during G2's adolescence (see Figure 1, path b) were expected to place G2 target adolescents at increased risk for becoming parents at an earlier age. Early entry into parenthood was expected to be associated with higher levels of observed G2 harsh parenting when G3 children are 2 years of age (see Figure 1, path c). Finally, harsh parenting and child externalizing problems were expected to be mutually influential during early childhood (see Figure 1, paths d and e).

Method

Sample

Data used in the present study come from the Family Transitions Project (FTP), an ongoing, longitudinal study of 558 target adolescents, their parents, and selected close relationships. Interviews were first conducted with adolescents (G2), their parents (G1) and a close aged sibling as early as 1989, when the target youth were in the 7th grade. Data were collected annually thereafter with an average retention rate of 92% through 2003. Of these youth, 451 came from two-parent families and 107 came from single, mother-headed families. In 1991, all 558 target participants were in the 9th grade and completed the same assessment battery.

Originally, families were recruited to study the family and developmental consequences of the farm crisis of the 1980s. Participants originally resided in rural Iowa and were primarily lower-middle or middle income. To reflect the changing focus on family transitions, G3 children of the G2 target participants were recruited into the study beginning in 1997, when G2 targets averaged 21 years of age. Biological G3 children of G2 target participants who were at least 18 months old and who resided with the G2 target at least 2 weekends a month were eligible to participate. Although noncustodial parents could be recruited, all G2 targets were custodial parents of the G3 children included in this study.

Currently, 191 G3 children have participated in the FTP. The present study included G2 participants with a G3 child, with G1 SES data from G2's adolescence, and with 2 years of G2 parenting and G3 child data available. Twenty-seven of the G3 children were excluded from the present analysis because they first participated in 2004 and their data are not yet available. Excluding the 27 children left a pool of 164 families; 10 additional families were excluded because they were missing G2 observational parenting data (n = 7) or G1 SES data (n = 3). Analyses are based on a total of 154 3-generation families. Of the included G2 target parents, 38% are male and 55% of the G3 children are male. G2 target participants identified themselves as White (97.2%) and non-White (3.8% Native American, Hawaiian, or other). G2 target parents identified 96.5% of the G3 children as White and 3.5% of the G3 children as non-White (i.e., African-American, Native American, Hawaiian, or other).

Demographic characteristics of the G2 parents and G3 children were computed from data obtained at G3 children's first assessment, or when G3 children were approximately 2 years of age. At the time of the G3 children's first assessment, most G2 parents were married to (46.5%) or living in a married like relationship with (14.8%) the G3 children's other biological parent. The remaining G2 target parents were either dating (11.9%) or had no contact with the G3 children's biological parent (26.8%). G2 participants reported an average household size of 3.57 members (SD = 1.20). Most G2 parents were not currently enrolled in school (83.2%) and averaged 13.19 years of education (SD = 1.59). Approximately 5% of G2 target parents did not graduate from high school, 39% reported completing high school, 44.7% had some college, and 12% reported graduating from college. G2 participants reported an average household income of $21,397 (SD = $19,267).

Procedures: 1991 − 1994

Trained interviewers visited all participating families twice each year during the G2 target adolescents' 9th, 10th, and 12th grades. Each visit lasted about two hours and each year's assessment followed the same procedures. During the first visit, family members completed a set of questionnaires, including G1 parents' reports of their current income, assets, and debts as well as their level of education. G2 self report assessments obtained during this time are not used in the present report. During the second visit, family members participated in structured interaction tasks that were videotaped; these data are not used in the present report.

Procedures: 1997 − 2003

After 1994, focus of study shifted from the family of origin to the G2 target participants' emerging families of procreation. During this transition into adulthood, G2 target participants and a romantic partner or close friend completed questionnaires about themselves, their relationships, and their goals. From 1997 onward, trained interviewers visited all G2 target participants on two separate occasions each year on a biennial schedule. G2 target participants with an eligible biological child completed an additional one-hour home visit with their G3 children. G2-G3 home visits occurred annually beginning when G3 children were between 18 and 27 months of age (2 year assessment) and continuing until children reached 7 years of age. After age 7 G3 children are assessed on the same biennial assessment schedule as their G2 parents. Only data from the age 2, 3, and 4 G3 home visits are used in the present report.

The procedures used in the 2, 3, and 4 year assessments are virtually identical. Prior to the in-home assessment, G2 parents completed a packet of questionnaires about their G3 children, including G3 children's externalizing behavior. During the in-home assessment, G2 parents and G3 children participated in a variety of videotaped interactional tasks. Observational ratings derived from a puzzle completion task and clean up task were used to measure parenting.

During the 5-minute puzzle task, G3 children were presented with a puzzle that was too hard to complete alone. G2 parents were instructed to offer any help necessary, but to let G3 children complete the puzzle alone. Different puzzles were used for the 2, 3, and 4 year old assessment and puzzles were selected that just exceeded G3 children's developmental abilities. The clean-up task was positioned at the end of the 1-hour assessment battery. After playing with various age appropriate toys for 6 minutes alone, an interviewer joined G3 children for an additional 5 minutes of play. To standardize the amount of toys G3 children cleaned up, interviewers dumped out all free play toys. After 5-minutes, interviewers instructed parents that G3 children needed to clean up the toys and that while G2 parents could offer any help deemed necessary, G3 children must complete the task alone. The clean up task lasted 5 minutes at the 2-year-old assessment and 10 minutes at the 3- and 4-year-old assessments. Trained observers coded the puzzle and clean-up tasks using the Iowa Family Interaction Rating Scales (Melby & Conger, 2001) and behavioral codes measuring G2 target parents' harsh parenting during both the puzzle and clean up tasks were included in these analyses.

Measures: 1991 − 1994

G1 education

G1 parent education largely remained unchanged throughout the four year interval. To maximize G1 parents' education, we used the average of G1 fathers' and mothers' education measured in 1994, or when G2 targets were in 12th grade. G1 parents reported an average of 13.43 years of education (SD = 1.01; range 11.5 − 17 years).

G1 poverty status

G1 parents provided detailed reports of economic circumstances during each year of the study. Poverty status was computed annually in accordance with national poverty standards. First, G1 parents' reports of all of their sources of income (i.e., money received from jobs, investments, and alimony or child support, if applicable) were summed. Second, a household size score was created by tallying all members of the household. Poverty status was defined as 150% of the federal poverty level for each given year. Near poor families, or families with incomes between 100% and 150% of federal poverty levels, may be poorer than families whose income falls below federal poverty levels because the near poor qualify for less financial assistance than impoverished families. Consequently, a number of empirical studies include near poor and categorize impoverished families as those with incomes at or below 150% (De Civita, Pagani, Vitaro, & Tremblay, 2007) or 200% (Lynch, Kaplan, & Shema, 1997) of federal poverty guidelines. We used the more conservative 150% of federal poverty levels to classify families as impoverished.

Families received a score of 1 if their income was at or below 150% of the federal poverty level or a 0 if their household income exceeded 150% of the poverty level for their household size in a given year. Poverty was estimated from data collected during the 1991, 1992, and 1994 assessments because parents did not provide detailed income reports in 1993. Twenty-three percent of families had income levels below the 150% federal poverty level criteria in 1991, 27.2% in 1992, and 14.1% in 1994. In total, 36.8% of the families fell below 150% of the poverty line during at least one of the assessment years. An overall poverty score was created by averaging scores across the three years. As argued by Rodgers (1995), taking an average poverty score across multiple years provides a more accurate estimate of poverty level by minimizing variability in poverty level due to yearly fluctuations in income or to measurement error. The average poverty score was 0.62 (SD = 0.94).

Measures: 1997 − 2003

G2 age at first parenthood

G2 parents' reports of their age at their G3 child's birth were used to measure G2 age at parenthood. Since only G2 parents who had a G3 child by 2002 were eligible to participate, G2 parent age could not exceed 25 years of age. G2 parents' average age at G3's birth was 21.62 years (SD = 1.90; range: 18 − 25 years; median = 22 years).

G2 harsh parenting: Observer ratings

Trained observers rated G2 target parents' harsh behaviors towards their G3 children during the puzzle task and clean-up task. Observers rated 6 parenting behaviors: hostility (i.e., harsh, angry, and rejecting behaviors), escalate hostile (i.e., parents' intensification of their own hostile behavior towards the child), reciprocate hostile (i.e., parents' responses to child's anger with hostility), angry-coercion (i.e., attempts to control child's behavior in an angry or threatening manner), antisocial (i.e., disruptive, age-inappropriate behavior), and physical attack (i.e., hitting, pushing, slapping) behaviors towards child. Codes were rated on a 9-point continuum ranging from no evidence of the behavior (1) to the behavior is highly characteristic of the parent (9). Scores were created by averaging across the 12 items at each assessment wave. As shown in Table 1, G2 harsh parenting scores indicated generally low levels of harsh parenting during the two tasks. Both the mean and standard deviation of harsh parenting declined from age 2 to 4 (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of bivariate correlations, means, standard deviations, and internal consistency estimates for study constructs.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Mean (SD) | α | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. G1 years of education | 1.0 | 13.43 (1.01) | --- | |||||||||

| 2. G1 years in poverty | −.10 | 1.0 | 0.62 (.94) | --- | ||||||||

| 3. G2 age at parenthood | .05 | −.18* | 1.0 | 21.62 (1.90) | --- | |||||||

| 4. G2 harsh parenting: Age 2 | −.04 | .03 | −.25** | 1.0 | 2.40 (1.19) | .90 | ||||||

| 5. G2 harsh parenting: Age 3 | −.07 | .10 | −.32** | .60** | 1.0 | 2.37 (1.25) | .90 | |||||

| 6. G2 harsh parenting: Age 4 | −.16 | −.04 | −.10 | .14 | .46** | 1.0 | 2.03 (0.95) | .87 | ||||

| 7. G3 externalizing behavior: Age 2 | −.02 | −.12 | −.06 | .20* | .02 | .22* | 1.0 | 12.55 (5.82) | .82 | |||

| 8. G3 externalizing behavior: Age 3 | .01 | −.09 | −.05 | .22* | .32** | .33** | .59** | 1.0 | 11.46 (6.52) | .86 | ||

| 9. G3 externalizing behavior: Age 4 | −.18+ | −.11 | −.07 | .28** | .22* | .27** | .55** | .70* | 1.0 | 11.52 (6.86) | .88 | |

| 10. G2 target sex | .01 | .06 | −.17+ | −.06 | .01 | .07 | −.05 | .05 | −.07 | 1.0 | 1.61 (.49) | --- |

| 11. G3 child sex | .03 | −.15+ | −.10 | .13 | .11 | .23* | .16+ | .20* | .07 | −.02 | 1.44 (.50) | --- |

Note:

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01.

Two independent observers rated 25% of the puzzle and clean-up tasks. The intra-class correlation (ICC) coefficient for the summed total of the 6 behaviors coded in the puzzle task was .78 and .75 for the clean up task. As shown in Table 1, the Cronbach alpha coefficients were very good during each of the three years ranging from .87 to .90.

G3 externalizing behavior

G2 parents completed the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1994) about the G3 child at each assessment. The 25-item externalizing subscale was used to measure G3 children's externalizing behavior. G2 parents rated each statement on a 3 point scale, ranging from not true to very true, regarding their G3 child's behavior during the past 2 months. Cronbach alpha coefficients indicated very good internal consistency at each point in time (α range: .82 to .88; see Table 1). Items were summed to create a total score. As shown in Table 1, externalizing behaviors scores declined from age 2 to 4, but the amount of variation remained fairly consistent over that time.

Results

Data analyses proceeded in several steps. First, selective attrition analyses were computed to determine the extent to which G2–G3 parent-child dyads that were excluded from the study differed from those included in the present analysis. Next, constructs were correlated to evaluate consistency with hypothesized expectations. Since G2 target participants and G3 children varied by sex, G2 and G3 sex were correlated with study constructs to evaluate the extent to which constructs varied by parent or child gender (1 = male; 2 = female). Gender differences were not expected. Finally, the structural model depicted in Figure 1 was estimated.

Selective attrition analysis

To evaluate the extent to which G3 children excluded from the study differed reliably from the G3 children included in the analysis, means of all study constructs were compared. Scores for the 154 included children were compared with the scores for the 10 excluded families using Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) procedures. No statistically significant differences or trends towards statistical significance emerged.

Correlation analyses

The correlations provided some supported the proposed hypotheses (see Table 1). G1 education was not significantly correlated with G1 poverty (e.g., r = −.10). Perhaps this non-significant correlation is not unexpected as Conger and Donnellan (2007) argue that indicators of socioeconomic status often demonstrate weak to modest associations with each other and family adjustment. Similarly, G1 education was not significantly correlated with G2 age of parenthood, but G1 poverty was. G2 age of parenthood was significantly and negatively correlated with observed harsh parenting when children were 2 and 3, but not 4 years, of age, indicating that younger parents were harsher during parenting situations, particularly during the toddler years. G2 age of parenthood was unrelated to G3 externalizing behavior at any age.

Finally, some support for the mutual influences hypothesis emerged (see Table 1). First, concurrent correlations between harsh parenting and child externalizing behaviors were statistically significant; higher levels of harsh parenting were associated with more child externalizing problems within time. Second, age 2 and age 3 harsh parenting scores were significantly correlated with age 3 and age 4 child externalizing scores. Although G3 age 3 externalizing behaviors were significantly correlated with G2 harsh parenting at age 4, age 2 externalizing scores were not significantly correlated with age 3 harsh parenting.

The correlational analysis also revealed significant associations with G2 and G3 sex (see Table 1). First, G2 parent sex was significantly correlated with age of parenthood (r = −.17; p < .05), indicating a younger age of parenthood for G2 females. Second, as compared to girls, G3 boys had somewhat higher externalizing scores at age 2 and significantly higher scores at age 3. G2 parents were significantly harsher with their G3 boys at age 4 than with G3 girls. Since the focus of this report was not on the role of gender in social interactional processes, the effects of G2 and G3 sex on study constructs were statistically controlled. Including the controls did not change the pattern of results. Multi-group models also indicated no G2 or G3 sex differences in the magnitude of the reported path coefficients.

Test of the structural model

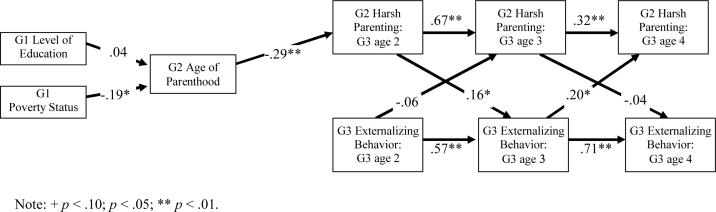

Due to sample size restrictions, path analysis was used to evaluate the study hypotheses rather than structural equation modeling with latent variables. Sample size to estimated parameter ratio of 5:1 (e.g., Falk & Miller, 1992) or 10:1 (e.g., Bollen, 1989) with a minimum sample of 100 (Bollen, 1989) is recommended when estimating structural models with latent constructs. By using path analysis the sample size to parameter ratio was within acceptable levels (i.e., 5.7:1 with the statistical controls). The model was estimated using AMOS 5.0 FIML procedures and results are presented in Figure 2. Although not depicted in Figure 2, G1 education and G1 poverty were correlated and the G2 harsh parenting and G3 externalizing problem residuals were correlated within each age. Harsh parenting and child externalizing residuals were significantly associated when G3 children were age 2 (r = .19; p < .05) and age 3 (r = .32; p < .01), but not when G3 children were age 4 (r = .15).

Figure 2.

The structural equation model testing intergenerational consequences of socioeconomic circumstances for age at first birth, harsh parenting, and child externalizing behavior.

Consistent with the results of the correlational analysis, G1 education was not linked to G2 age of parenthood (β = .04) while G1 poverty was significantly and negatively related to G2 age of parenthood (β = −.19). Second, as expected, G2 age of parenthood was significantly and negatively associated with G2 harsh parenting when G3 children were 2 years of age. In other words, becoming a parent at a younger age was associated with harsher parenting when G3 children were 2 years old. Next, G2 harsh parenting observed when G3 children were 2 years of age predicted increases in G3 externalizing problems from age 2 to age 3, but G2 harsh parenting observed at age 3 did not predict change in externalizing problems from age 3 to age 4. In contrast, G3 children's age 2 externalizing problems did not predict change in harsh parenting from age 2 to age 3, but externalizing problems measured at age 3 did predict significant increases in harsh parenting from age 3 to age 4.

Fit indices suggested that the model fit the data well. Three indices were used to evaluate model fit. First, the chi-square statistic indicates the extent to which the data differs from the estimated model. The chi-square was not statistically significant (χ2 [21] = 20.37), indicating little difference between the estimated model and the data. Second, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) statistic is based on the noncentrality parameter and makes adjustments for sample size (Kline, 2005). A well fitting model has a RMSEA of less than .05, as in the present analysis (RMSEA = .000). The Comparative Fit Index (CFI) rewards parsimonious models and a value greater than .95 indicates a well fitting model (Kline, 2005). The CFI generated from the present analysis was 1.00, providing another indicator of a well fitting model.

Discussion

Children of poverty are often found to lag behind their more affluent peers in terms of academic, social, and behavioral outcomes (e.g., McLoyd, 1998). While studies frequently link economic hardship with children's maladjustment within the family of origin, few studies have considered the intergenerational consequences of experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage in one generation on the quality of parent-child relationships in the next generation. We addressed this gap by evaluating the extent to which socioeconomic disadvantage affects the behavioral adjustment of the next generation of children. The consequences of economic hardship were expected to extend beyond simply the timing of parenthood to affect the quality of parenting and child adjustment in the next generation of children. That is, experiencing socioeconomic disadvantage during adolescence may set into motion a sequence of events that place the next generation at increased risk for developing behavior problems.

In general, the results of the current investigation supported our expectations. Socioeconomic disadvantage in the form of average level of poverty during G2 target participants' adolescence, predicted an earlier age of G2 parenthood. Younger G2 parents were observed to be harsher during disciplinary situations with their 2-year old children. Support for mutual influences in harsh parenting and child externalizing problems also emerged; however, these processes appeared to vary by child age. That is, harsh parenting at age 2 was associated with a relative increase in externalizing problems from age 2 to 3 and age 3 externalizing problems predicted relative increases in harsh parenting from age 3 to 4. No gender differences emerged. The following discussion considers the implications and limitations of these findings.

Intergenerational Consequences of Socioeconomic Risk: Implications for Timing of Parenthood

With secular trends of increasing maternal age at first birth, the meaning of early parenthood is changing. Over the past 30 years the average age of women's first birth has increased 3 years from 22 years of age in 1970 to 25 years of age in 2000 (Sutton & Matthew, 2004). The same risk factors associated with teenage pregnancy and parenthood seems to be associated with earlier childbearing or childbearing during the early 20's (e.g., Hardy, et al., 1998; Jaffee, 2002). Repeatedly, more socioeconomic disadvantage within the family of origin predicts earlier childbearing relative to one's peers (Hardy, et al., 1998; Jaffee, 2002; Russell, 2002). Consistent with previous research, average level of poverty during adolescence was associated with an earlier age of childbearing for both G2 boys and girls. Moreover, G2 girls were more likely to be younger than the G2 boys at the birth of their G3 child (Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2006). These findings are particularly important since boys rarely are included in studies predicting the timing of parenthood.

In contrast to expectations and previously published work (e.g., Russell, 2002), G1 education was unrelated to the timing of G2 childbearing. Surprisingly, G1 education and G1 poverty were not correlated. Although both of these findings are counterintuitive, it is important to consider the context in which the Family Transitions Project began. The FTP was initially developed to study the effects of the economic downturn in farming during the late 1980's for families. Many participating families were severely impacted by the farm crisis and may not have fully recovered during G2's adolescence. For instance, although 27% of participating families met the 150% poverty cutoff in 1992, by 1994 only 14% of families met this criterion. In all likelihood, G1 parents' income was more closely tied to residual effects of the farm crisis rather than their years of education.

The Timing of Parenthood and Harsh Parenting – Child Problem Behavior Reciprocities

As predicted, age of parenthood emerged as a critical link between socioeconomic disadvantage and harsh parenting. G1 poverty predicted G2 harsh parenting through its association with an earlier age at first birth. Consistent with previous research, younger parents were observed to be harsher during disciplinary situations with their 2-year-old children than the older G2 parents in the sample (e.g., Berlin, Brady-Smith, & Brooks-Gunn, 2002). Given the high rates of externalizing problems typical of the toddler period (e.g., Gilliom & Shaw, 2004), over-reliance on harsh parenting strategies is troublesome in that such parenting may create an environment that increases risk for reciprocities in harsh parenting and child externalizing behavior. Although the reciprocity between harsh parenting and child externalizing problems did not occur within the same one-year time lags, harsh parenting did lead to an intensification of externalizing behavior from ages 2 to 3 years. These child behaviors then led to increases in harsh parenting by age 4. Replication studies will be needed to determine if this extended pattern of mutual influence generalizes to other families.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Clinical Implications

These results have several important limitations. First, the sample is unique. Intergenerational studies are expensive in that they require contact with a sample over an extended period of time. G2 participants participated in annual and biennial assessments for almost 20 years; these assessments typically involved one or two 2-hour home visits per year. Adding the G3 participant to the study increased the total assessment time by an additional 1-hour home visit each year. Thus, the G2 participants may be a unique group in that they agreed to such a rigorous interview schedule for such an extended period of time.

Second, the selective nature of the sample may limit the generalizability of the findings. Only G2 participants with a G3 child were included in this report. The impact of G1 poverty and education on the timing of parenthood may be conservative given the restriction of range in G2 parental age at first birth. That is, the oldest a G2 participant could be was 25 years of age, resulting in a sample of G2 participants who had a child earlier than the national average. These results may not generalize to individuals who delay childbearing beyond age 25. Fully understanding the causes and consequences of age of parenthood requires a prospectively collected sample of individuals followed as they become parents. The FTP is ongoing and G2 parents, their spouses/partners, and their children are continuing to be added to the study. Future analyses will be able to consider both risk and protective factors that affect the timing of parenthood and quality of G2 parenting as well as subsequent risk for G3 externalizing problems.

Third, the sample is representative of rural Iowa; results may not extend to more urban settings. Interestingly, the G2 parents now reside all over the country and may be more nationally representative than their G1 parents. Fourth, given the intergenerational focus of the present report, only one of the G3 children's parents were included in the study, the G2 target parent. All participating G2 targets were the custodial parent of G3 children, but only about 60% of the G3 children resided with both of their biological parents. Given the small sample size, considering the impact of single parent status on the processes described in this report is not possible. A benefit of the present study is that G2 fathers and mothers were included, however future studies may benefit from including both parents and considering the unique or additive effects of mothers' and fathers' parenting on G3 children's emerging problem behaviors. Finally, the reliance on unidimensional measures, rather than latent constructs, is a limitation.

Despite these limitations, the results add to the growing body of work documenting the negative impact of poverty on adjustment (e.g., Duncan, Brooks-Gunn, & Klebavo, 1994; McLoyd, 1998) and indicate that the effects of poverty extend beyond the family of origin to influence the quality of family relationships in future generations. Future studies may wish to consider personal characteristics of the G2 offspring that protect against: a) the influence of poverty on the age of parenthood and b) the effect of age of parenthood on parenting quality. For instance, the effect of poverty on the timing of parenthood may be minimized by having parents who encourage additional education despite family hardships. In line with this idea, educational scholarships may provide less affluent G2 adolescents with opportunities to invest in their future and incentives to delay childbearing (e.g., Jaffee, 2002). Alternatively, personality characteristics of the G2 parent may moderate the influence of timing of parenthood on observed levels of harsh parenting. That is, G2 parents with higher levels of constraint and positive emotionality may be less likely to rely on harsh parenting strategies during interactions with young children. Characteristics of the family of origin home environment and the G2 (e.g., intelligence, personality) may offer some protection by disrupting the intergenerational transmission of risk.

Finally, the results have important clinical implications. In particular, early entry into parenthood does not appear to be a random event, but rather is associated with a host of disadvantages within the family of origin including, economic, marital conflict, harsh and inconsistent parenting, family conflict, and mental health problems (e.g., Coley & Chase-Lansdale, 1998; Ellis, et al., 2007; Miller-Johnson, et al., 1999; Russell, 2002, Scaramella, et al., 1998; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2001). Prevention efforts aimed at mitigating financial hardship while also targeting the quality of family relationships may be most effective in delaying childbearing among the second generation children. By strengthening family relationships, potential protective mechanisms may be enhanced. For instance, parenting that is high in warmth, low in hostility, and high in involvement has been found to protect adolescents from experiencing increases in internalizing and externalizing problems (Scaramella, Conger & Simons, 1999). Strengthening the quality of parent-child relationships during adolescence has the added benefit of modeling the very parenting strategies that predict lower levels of externalizing behaviors in the next generation. Taken together, these results suggest that the full effects of poverty extend beyond the family of origin to affect the timing of parenthood and the quality of parent-child relationships within the family of procreation. Studies evaluating the consequences of intervention efforts to reduce economic disadvantage may fall short without considering the potential consequences of such interventions on future generations.

Acknowledgments

This research is currently supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the National Institute of Mental Health (HD047573, HD051746, and MH051361). Support for earlier years of the study also came from multiple sources, including the National Institute of Mental Health (MH00567, MH19734, MH43270, MH59355, MH62989, and MH48165), the National Institute on Drug Abuse (DA05347), the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD027724), the Bureau of Maternal and Child Health (MCJ-109572), and the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Adolescent Development Among Youth in High-Risk Settings. We wish to thank Sarah Spilman for her data management assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: The following manuscript is the final accepted manuscript. It has not been subjected to the final copyediting, fact-checking, and proofreading required for formal publication. It is not the definitive, publisher-authenticated version. The American Psychological Association and its Council of Editors disclaim any responsibility or liabilities for errors or omissions of this manuscript version, any version derived from this manuscript by NIH, or other third parties. The published version is available at http://www.apa.org/journals/fam/

Contributor Information

Laura V. Scaramella, University of New Orleans

Tricia K. Neppl, Iowa State University

References

- Achenbach T. Child Behavior Checklist. University of Vermont; VT: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Brady-Smith C, Brooks-Gunn J. Links between childbearing age and observed maternal behaviors with 14-month-olds in the early Head Start research and evaluation project. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2002;23:104–129. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley; Oxford, England:: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, Corwyn RF. Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ. The effects of poverty on children. The future of children. 1997;7:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coley RL, Chase-Lansdale PL. Adolescent pregnancy and parenthood: Recent evidence and future directions. American Psychologist. 1998;53:152–166. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Donnellan MB. An interactionalist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Reiview of Psychology. 2007;58:175–199. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, McCarty JA, Yang RK, Lahey BB, Burgess RL. Mother's age as a predictor of observed maternal behavior in three independent samples of families. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1984:411–424. [Google Scholar]

- De Civita M, Pagani LS, Vitaro F, Tremblay RE. Does maternal supervision mediate the impact of income source on behavioral adjustment in children from persistently poor families? Journal of Early Adolescence. 2007;27:40–66. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Economic deprivation and early childhood development. Child Development. 1994;65:296–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, Bates JE, Dodge KA, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Pettit GS, Woodward L. Does father absence place daughters at special risk for early sexual activity and teenage pregnancy? Child Development. 2003;74:801–821. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot BI, Pears KC, Capaldi DM, Crosby L, Leve CS. Becoming an adolescent father: Precursors and parenting. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1209–1219. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falk RF, Miller NB. A primer for soft modeling. University of Akron Press; Akron, OH: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Gilliom M, Shaw DS. Codevelopment of externalizing and internalizing problems in early childhood. Development and Psychopathology. 2004;16:313–333. doi: 10.1017/s0954579404044530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granic I, Patterson GR. Toward a comprehensive model of antisocial development: A dynamic systems approach. Psychological Review. 2006;113:101–131. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.113.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy JB, Astone NM, Brooks-Gunn J, Shapiro S, Miller TL. Like mother, like child: Intergenerational patterns of age at first birth and associations with childhood and adolescent characteristics and adult outcomes in the second generation. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1222–1232. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoff E, Laursen B, Tardif T. Socioeconomic status and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 2: Biology and ecology of parenting. 2nd edition Erlbaum; Mahawah, NJ: 2002. pp. 213–252. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR. Pathways to adversity in young adulthood among early childbearers. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:38–49. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw DS. The development of coercive family processes: The interaction between aversive toddler behavior and parenting factors. In: McCord Joan., editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. Cambridge University Press; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2nd edition Guilford Press; NY, NY: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Shema SJ. Cumulative impact of sustained economic hardship on physical, cognitive, psychological, and social functioning. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:1889–1895. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712253372606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchland JF, Hock E, Widaman K. Mutual relations between mothers' depressive symptoms and hostile-controlling behavior and young children's externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2002;2:335–353. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. American Psychologist. 1998;53:185–204. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.2.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melby JN, Conger RD. The Iowa family rating scales: Instrument summary. In: Kerig PK, Lindahl KM, editors. Family observational coding systems: Resources for systemic research. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2001. pp. 33–58. [Google Scholar]

- Miller-Johnson S, Winn D, Coie J, Maumary-Gremaud A, Hyman C, Terry R, Lochman J. Motherhood during the teen years: A developmental perspective on risk factors for childbearing. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:85–100. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oakes JM, Rossi PH. The measurement of SES in health research: current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:769–784. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Reid JR, Dishion TJ. Antisocial boys. Castalia; Eugene, OR: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Pears K, Pierce SL, Kim HK, Capaldi DM, Owen LD. The timing of entry into fatherhood in young, at-risk men. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:429–447. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers JR. An empirical study of intergenerational transmission of poverty in the United States. Social Science Quarterly. 1995;76:178–194. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin KH, Burgess KB, Dwyer KM, Hastings PD. Predicting preschoolers' externalizing behaviors from toddler temperament, conflict, and maternal negativity. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39:164–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST. Childhood developmental risk for teen childbearing in Britain. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2002;12:305–324. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD. Intergenerational continuity of hostile parenting and its consequences: The moderating influence of children's negative emotional reactivity. Social Development. 2003;12:420–439. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Simons RL. Parental protective influences and gender-specific increases in adolescent internalizing and externalizing problems. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1999;9:111–141. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Conger RD, Simons RL, Whitbeck LB. Predicting risk for pregnancy by late adolescence: A social contextual perspective. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1233–1245. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaramella LV, Leve LD. Clarifying parent-child reciprocities during early childhood: The early childhood coercion model. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2004;7:89–107. doi: 10.1023/b:ccfp.0000030287.13160.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart E, Simons RL, Conger RD. The effects of delinquency and legal sanctions on parenting behaviors. In: Fox GL, Benson ML, editors. Families, crime, and criminal justice. 1st Edition Vol. 2. JAI Press; NY, NY: 2000. pp. 257–279. [Google Scholar]

- Sutton PD, Matthews TJ. National Vital Statistics Report. Vol. 52. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services: Center for Disease Control and Prevention; May 10, 2004. Trends in the characteristics of births by state: United States, 1990, 1995, and 2000−2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Risk factors and life processes associated with teenage pregnancy: Results of a prospective study from birth to 20 years. Journal of Marriage & the Family. 2001;63:1170–1184. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Gender differences in the transition to early parenthood. Development and Psychopathology. 2006;18:275–294. doi: 10.1017/S0954579406060159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]