Abstract

The role of the liver in fatal intoxication with the binary toxin ricin is undefined. Means to reverse pathological events in the liver and to gain host survival after exposure to this toxin have not been described. We report a robust 7/4+ neutrophil influx into the liver of C57BL/6 mice after parenteral ricin challenge. This influx occurs in peri-portal and centro-lobular hepatic areas within 2 hours, followed by the abrupt disappearance of hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells at 8–12 hours. Microarray, ribonuclease protection assays, Northern blotting, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays showed chemokine mRNA and protein for neutrophils (CXCL1/KC, CXCL2/MIP-2) and macrophages (CCL2/MCP-1) increased in the liver by 2 hours and persisted for more than 40 hours after ricin injection. A specific sequence of intra-hepatic pathophysiological events followed ricin injection, including red blood cell pooling (8–12 h), loss of hepatocyte glycogen (8–48 h) associated with progressive hypoglycemia, and fibrin deposition (24–48 h). Monoclonal antibody to ricin A chain administered intravenously blunted hypoglycemia and abrogated death. This outcome was observed when anti-ricin antibody was present prior to toxin exposure or when administered up to 10 hours post-toxin exposure. Targeting antibody to specific amino acid sequences on the ricin A chain (HAEL and QXXWXXA) was critical to the therapeutic effect. Re-emergence of liver macrophages/Kupffer cells and replenishment of glycogen in previously depleted hepatocytes preceded full recovery of the host. These data define the pathobiology of liver injury in ricin intoxication, as well as a new means and specific targets for post-exposure therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Inflammation, antibodies, monocytes/macrophages, neutrophils, rodent

INTRODUCTION

Liver inflammation with loss of functioning hepatocytes is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in chronic viral and drug-induced hepatitis, and the mechanisms involved leading to tissue injury and cell death have been a major focus of recent investigation (1,2). Processes responsible for hepatic injury associated with inflammation following exposure to binary toxins such as ricin are less well known. Specifically, the nature and source of molecules that direct migration of inflammatory cells into the liver, the sequence of ensuing pathophysiological events, and means to abrogate them are not clear. Knowledge of these areas could suggest therapeutic strategies to diminish morbidity and mortality in the exposed human host.

Ricin has been designated a category B priority agent by NIAID, given its ease of manufacture, transportability, potency (second only to botulism toxin) and physicochemical stability (3). Ricin binds ligands, primarily β1,4-linked galactose, via its B subunit which, in turn, promotes internalization of the A subunit into the cell where it blocks protein synthesis by depurination of 28S rRNA (4,5). Work in mouse models of ricin toxicity reported recently has focused on the kidney, where clinical disease (elevated BUN and creatinine, decreased urinary volume), kidney pathology (glomerular fibrin deposition, tubular epithelial apoptosis) and features of the hemolytic uremic syndrome (thrombocytopenia, albuminuria, renal failure and hemolytic anemia) are reported under special circumstances where a high dose of ricin (120 μg/kg) is given to mice intravenously (6). In these studies, the ribotoxic stress response was well-documented. Although the ‘inflammatory prodrome’ period between toxin exposure and clinical signs of hepatic and renal dysfunction is available for therapeutic intervention, there is at present no specific therapy available to retard or prevent organ failure following ricin exposure.

Over the last decade, biomedical investigation has identified specific molecules such as TNF-α as central to the pathogenesis of certain diseases, mediating inflammation, injury and subsequent dysfunction of target organs (7–9). Monoclonal antibodies that bind these molecules are attractive as therapeutic agents for several reasons. They allow a particular sequence of tissue-injurous events to be moderated or halted in a time-limited manner, yet avoiding the permanent loss of the targeted antigens needed by the host for normal physiological processes. In the case of toxin exposure, optimal application of such monoclonal antibody therapy should target molecules involved early in the pathogenic process, with a therapeutic effect that extends into the post-exposure period, allowing time for regeneration of cells and recovery of function. We have recently shown that monoclonal antibodies directed to two cytokines responsible for neutrophil invasion of kidney following exposure to the binary toxin Shiga toxin 2 with lipopolysaccharide, limit subsequent inflammation in a mouse model (10). In the present study, we sought to elucidate pathophysiological events in the liver triggered by exposure to a related toxin, ricin, and to determine whether the intra-vascular presence of monoclonal antibodies directed to the A subunit of the toxin itself would abrogate critical tissue injurous processes sufficiently early to reduce host morbidity and mortality. We report that immunoglobulin binding to two peptide motifs in the ricin A chain diminishes hypoglycemia, a marker of hepatic dysfunction, as well as lethality of the host after exposure to lethal quantities of ricin. The emergence of hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells and accumulation of glycogen in carbohydrate-depleted hepatocytes were strongly associated with host recovery, pointing to their pivotal role in binary toxin injury.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

The immunoglobulin reagents utilized in this study were: rat anti-mouse neutrophil-specific monoclonal antibody, clone 7/4, used at 1:20 (Caltag, Burlingame, CA); and a rat anti-mouse monocyte/macrophage-specific monoclonal antibody, clone F4/80, used at 1:10,000 and produced by the Hybridoma Core Laboratory, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Va. All biotin-labeled secondary antibodies were obtained from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA), and used according to the manufacturer’s directions. Monoclonal immunoglobulins to ricin A chain, designated RAC 17, 18, and 23, were generated from cloned hybridomas provided by Dr. Seth Pincus (Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center) who has characterized them previously (11). Each preparation was dialyzed against PBS and stored in aliquots at 1.2 mg/ml at −80° C until used. Control monoclonal immunoglobulins, matched for isotype (IgG1, IgG2a) were purchased from Chemicon International (Temecula, CA).

Ricin was purchased from Vector Laboratories as RCA II, isolated from Ricinus communis (castor bean) seeds, and consisting of two disulfide-linked chains of 32,000 and 34,000 Daltons. Residual sodium azide was removed by dialysis against PBS (ratio > 100:1, three changes over 48 hours), and samples were stored at 5 mg/ml in 10–20 μl aliquots. Biological function of the ricin was determined in dose-response experiments with Vero cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA), where 50% cytotoxicity was observed at 10 nM.

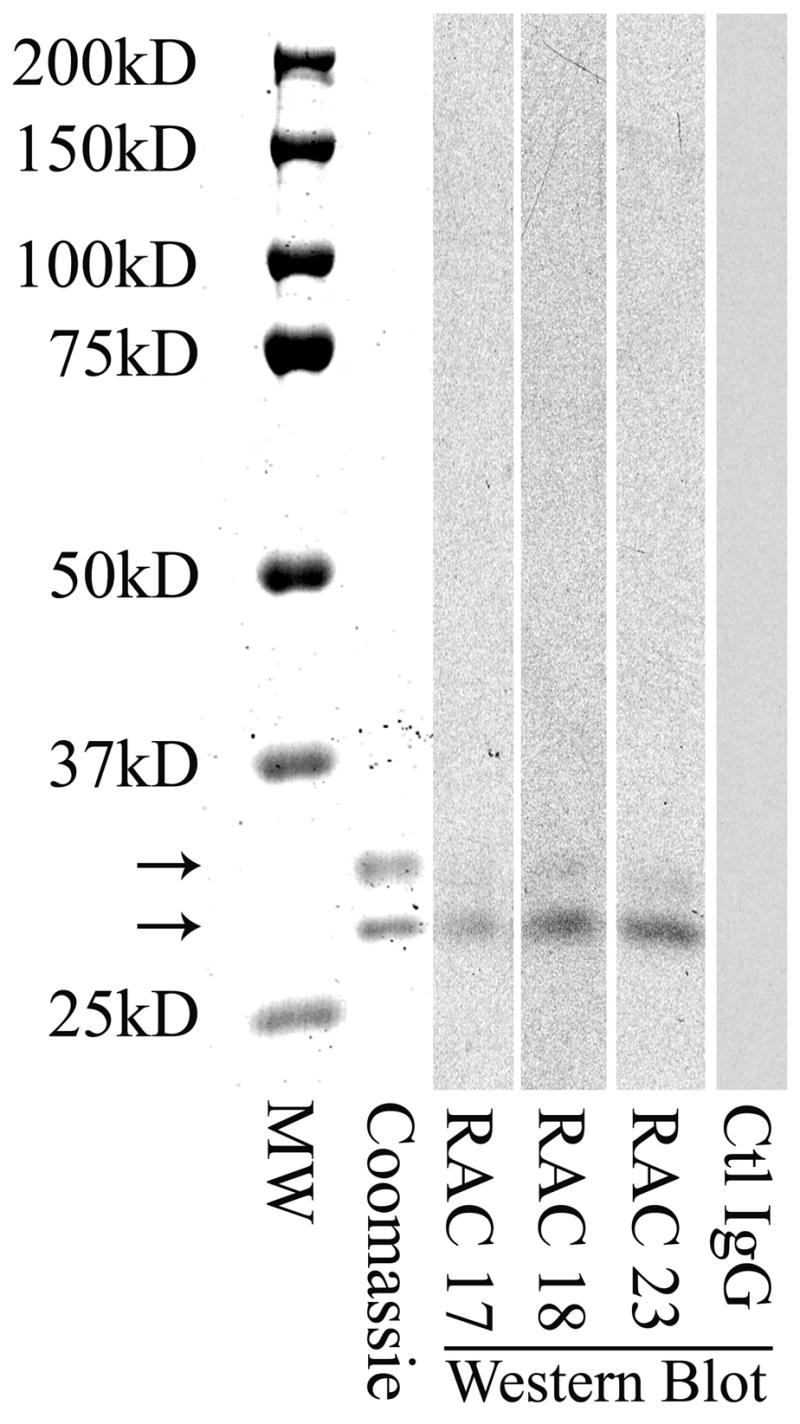

Purity of the ricin holotoxin was assessed by electrophoresis using 10% polyacrylamide gels (Invitrogen, Carlisbad, CA) with SDS Laemmli buffer followed by Commassie staining (Simply Blue SafeStain, Invitrogen). Two bands (32 and 34 kD) were identified, comprising 98.8% of total protein. An additional band at 64,000 daltons, comprising < 1.3 % of total protein, was identified as holotoxin by its molecular weight and by its reactivity with ricin-specific monoclonal antibody (data not shown). Western blotting was accomplished by transfer of proteins following PAGE to nitrocellulose using a Bio-Rad MiniPROTEIN 3 Cell system (Hercules, CA), and exposure of the membrane to monoclonal immunoglobulin (described above) at 1:10,000 dilution overnight at 4° C. After washing and addition of secondary antibody, sheep anti-mouse IgG conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (GE healthcare, Rankinghamshire, U.K.) at 1:40,000 dilution, the blot was developed using ECL (Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus, PerkinElmer LAS, Boston, MA) and autoradiography, incorporating two molecular weight standards, Biotinylated Protein Ladder Detection Pack (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and Precision Plus Kaleidoscope, (Bio-Rad). Using these techniques, immunoglobulin G, secreted by each of three study hybridoma clones, bound ricin A chain, in contrast to that of an irrelevant clone of the same immunoglobulin class used at the same concentration (Fig. 1). Weak binding by study clone immunoglobulin to ricin B chain may be attributable to lectin binding activity of B chain to the carbohydrate moiety of IgG, as suggested by previous ELISA data (11).

Figure 1.

Specific binding of monoclonal antibodies RAC 17, 18, and 23 to ricin A chain. Ricin holotoxin (1.25 μg/lane) was electrophoresed on a 10% SDS polyacrylamide gel, then stained for protein with a Commassie stain (column 2) or blotted onto nitrocellulose for subsequent exposure to a 1:10,000 dilution of the indicated hybridoma immunoglobulin. Each immunoglobulin bound the 32,000 Dalton A subunit of ricin, but was minimally reactive with the 34,000 Dalton B subunit (columns 3–5). Ctl IgG is a control mouse monoclonal IgG also used at 1:10,000 dilution (column 6). MW standards are shown in column 1. Lower arrow, 32,000 Dalton subunit; upper arrow, 34,000 Dalton subunit.

Animal experiments

Male C57BL/6 mice (male, 22–24 g) were purchased from Charles River laboratories (Wilmington, MA). For initial lethality studies, the ricin challenge regimen ranged from 20 to 35 μg/kg of mouse weight. In subsequent experiments, mice were injected intraperitoneally with 40 μg of ricin per kg, then euthanized at 0, 2, 4, 6, 12, 24, or 48 hours post-injection. In some experiments, mice were administered immunoglobulin in the tail vein before or after ricin exposure (see below). Liver, removed from a PBS-treated mouse, served as the control. Protocols were approved by The Animal Care and Use Committee, University of Virginia.

Microarray analysis

One lobe of liver from each mouse was placed into 2 ml of stabilization buffer, RNA Later (Ambion, Austin TX), for up to 2 weeks at 4° C until RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Midi Kit (Qiagen, Santa Clarita, CA) following the manufacturer’s protocol, and was quantified by absorbance at 260 nm. Total RNA from control and ricin-challenged mice was compared using GeneChip® Expression analysis probe arrays 430A 2.0 (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Briefly, the RNA was transcribed into cDNA via Superscript RT (reverse transcriptase from Invitrogen), then used to make biotinylated cRNA using T7 RNA polymerase. The biotinylated cRNA was precipitated, fragmented and analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. A hybridization solution was prepared which contained the fragmented cRNA, herring sperm DNA, acetylated BSA, and MES hybridization buffer. After pre-wetting the array with hybridization buffer, the array was hybridized for 16 hours. The hybridization solution was then removed and the array washed and stained. Results were analyzed using GeneX VA Software (original version at the National Center for Genome Resources, hhttp://www.ncgr.org/). Normalization was achieved by calculating the 50th percentile of all measurements for each sample; and each measurement for each gene was divided by this number. Normalized values below 0 were set to 0. In the case of PAF and LTB4, genes required for their synthesis were monitored because these molecules are lipids. Biological duplicate experiments were performed.

Northern blotting

The pBC-KC plasmid in E. coli HB101 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA (Item #35791, Accession #J04596). The plasmid was grown, harvested, and digested with PstI to isolate the 0.8 kb probe fragment. The digest was separated first on a 0.8% agarose gel followed by a 0.6% low melting point agrarose gel and the band was cut out. The probe was isolated and concentrated using an Elutip-d column (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, NH) and ethanol precipitation. The purified insert was labeled with 32P-dATP (Perkin Elmer, Boston, MA) using the Random Primers DNA Labeling System (Invitrogen). Total RNA was isolated from liver tissue and quantified at 260 nm using an Eppendorf Biophotometer (Brinkmann Instruments, Westbury, NY). Ten micrograms of RNA was separated on a 1% agarose, 2.2M formaldehyde gel and transferred by capillary action to a nylon membrane (Hybond-N, Amersham). RNA was crosslinked to a membrane using a UV Stratalinker (Stratagene, LaJolla, CA). Blots were prehybridized overnight at 42°C in ULTRAhyp buffer solution (Ambion). Blots were then hybridized overnight at 42°C in the same solution containing the labeled probe. After hybridization, the blots were washed in increasingly stringent SSC/SDS buffer solutions (2 × 5 min in 2X SSC, 0.1% SDS; 2 × 15 min in .01X SSC, 0.1% SDS) at 42°C to remove background, and then subjected to autoradiography using X-OMAT film (Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY). The blot was stripped between probes by boiling in 0.1% SDS.

Ribonuclease protection assay (RPA)

Standard and custom probe template sets (BD PharMingen, San Diego, CA) for mouse MIP-2 and MCP-1 were transcribed by T7 RNA polymerase and labeled with a-32P-UTP (New England Nuclear Corp., Boston, MA). Using the RiboQuant ™ or the RPA III (Ambion) kits and methods, 10μg of each sample was hybridized with an excess of probe overnight at 56°C. Free probe and other single-stranded RNAs were digested with RNase, and the RNase-protected RNA was purified and resolved on a 5% denaturing acrylamide gel. Gels were developed by exposure to Kodak XAR film at 70°C overnight. Results were normalized to 18S RNA (for CXCL1/KC) or to L32 RNA (for CXCL2/MIP-2 and CCL2/MCP-1) with a protected size of 112 nucleotides.

Immunohistochemistry

One liver lobule from each mouse was placed in a plastic cassette, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 hours prior to processing and paraffin embedding. Sections were cut at 3 microns, and placed on charged slides. Staining for immunolocalization of specific antigens was accomplished with incubations at 25 °C for 1 hour using the following immunoglobulins: 1) a monoclonal rat anti-mouse neutrophil IgG (clone 7/4); 2) a monoclonal rat anti-mouse monocyte/macrophage-specific IgG (clone F4/80). An avidin/biotin horseradish peroxidase system (Vector Laboratories) was used with DAB to localize the site of immunoreactive antigen. Finally, sections were counterstained in hematoxylin, mounted and photographed. The scoring of samples for quantification of neutrophils and monocytes/macrophages is described below (see Data Management).

In addition, special stains were used to study the liver. To determine the number of hepatocytes containing glycogen, sections were Periodic Acid Schiff stained and the number of positive cells per field (400x) was counted in ≥ 10 peri-portal areas and in a similar number of centro-lobular areas in each mouse liver. To determine injury to the liver, sections were stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin or by the Martius yellow-Brilliant Crystal Scarlet-Aniline Blue technique (MSB) as described (12). The number of 400x microscopic fields (centro-lobular or peri-portal) showing fibrin deposition (indicated by bright red staining) or red blood cell congestion (defined as aggregates of yellow-stained red blood cells two or more times larger than present in normal liver sinusoids) were counted over the whole section.

Cytokines in tissue homogenates

A lobule of liver was placed into 1ml of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 1% Triton X-100, 100 μl/ml protease inhibitor solution (#P8340, Sigma Chemical Co.), and immediately homogenized by hand, using a glass tissue grinder followed by sonification (Branson Sonifier, Danbury, CT; model 250; output setting, 4; 10 sec). After 30 min on ice, samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The resultant supernatant was aliquoted and stored at −70°C until analyzed. For measurement of cytokines, samples were diluted as needed and were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using a matched mouse cytokine antibody pair (Duo Set, R & D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). A standard curve was generated from each set of samples assayed, and calibrated against purified E. coli-expressed recombinant mouse cytokine per the manufacturer’s directions.

Neutralization Studies

Mice were injected with immunoglobulin via the lateral tail vein, one hour before to 14 hours after exposure to ricin. In most experiments, each mouse in the experimental group (N=5 or 10, as specified) was administered equal (20 μg) quantities of monoclonal antibodies RAC 17, RAC 18, and RAC 23 previously described (11). Amino acid specificities for the antigenic determinant (epitope) of each immunoglobulin were derived by sequencing bound peptides expressed in a random page library and are as follows: RAC 17—amino acid sequence HAEL, corresponding to residues 66–69 of RAC; RAC 18—QXXWXXA, corresponding to Q173, A178, and W213 of RAC; and RAC 23—GTXS, which could correspond to one of two sites on RAC: G213, T217, S222 and G159, T160, S156. Mice in the control group (N=5 or10, as specified) were administered intravenously an equal quantity of irrelevant mouse monoclonal immunoglobulin of the same isotypes (20μg or 60 μg/mouse, as indicated). All mice received intraperitoneal ricin at 40μg/kg, or 800 ng/20 g mouse. Blood samples were obtained every 12 hours via the tail vein for glucose determination using a hand-held glucometer (One touch Ultra, Lifescan, Inc., Milpilas, CA); and were monitored for activity, behavior, posture, and survival. In a subsequent experiment, each individual anti-ricin monoclonal antibody (RAC 17, 18 or 23, at 20 μg each) was administered intravenously six hours following ricin exposure, and the mice were followed for blood glucose and survival. Finally, to assess the effect of ricin neutralization on hepatic biology, all three monoclonal antibodies to ricin A chain (20 μg each per mouse) were administered intravenously 10 hours following ricin exposure, and the mice were euthanized 24, 48, and 72 hours later. A lobule of liver was harvested for staining and for immunohistochemical studies of neutrophil and monocyte infiltration, glycogen content and markers of hepatocyte injury by techniques described above.

Data Management

Data were expressed as the mean ±1 SD. The Students t test was used to determine statistical significance, with p <0.05 taken as significant. For quantification of immunoreactive neutrophils and macrophages in the liver, a minimum of six non-overlapping microscope fields, comprising the entire section, were counted and results reported as “number per field”, e.g., total number of neutrophils or macrophages counted divided by the number of fields. Glycogen-positive hepatocytes, fibrin deposition and RBC congestion were scored, as described above under Immunohistochemistry

RESULTS

Hepatic injury and lethality following ricin administration

Because findings may be mouse strain-specific, we first sought to define a range of lethal doses of ricin usable in the C57BL/6 mouse, a strain which our laboratory has utilized in prior published work with A-B toxins (10, 13). In dose-response studies, intraperitoneal challenge with ricin at 20 μg/kg (400 ng/20g mouse) or more was associated with profound lethargy by 48 hours and lethality within 4 days (Fig. 2B). In subsequent studies, we chose to use a dose of ricin (40 μg/kg) which was clearly at or exceeded the LD100.

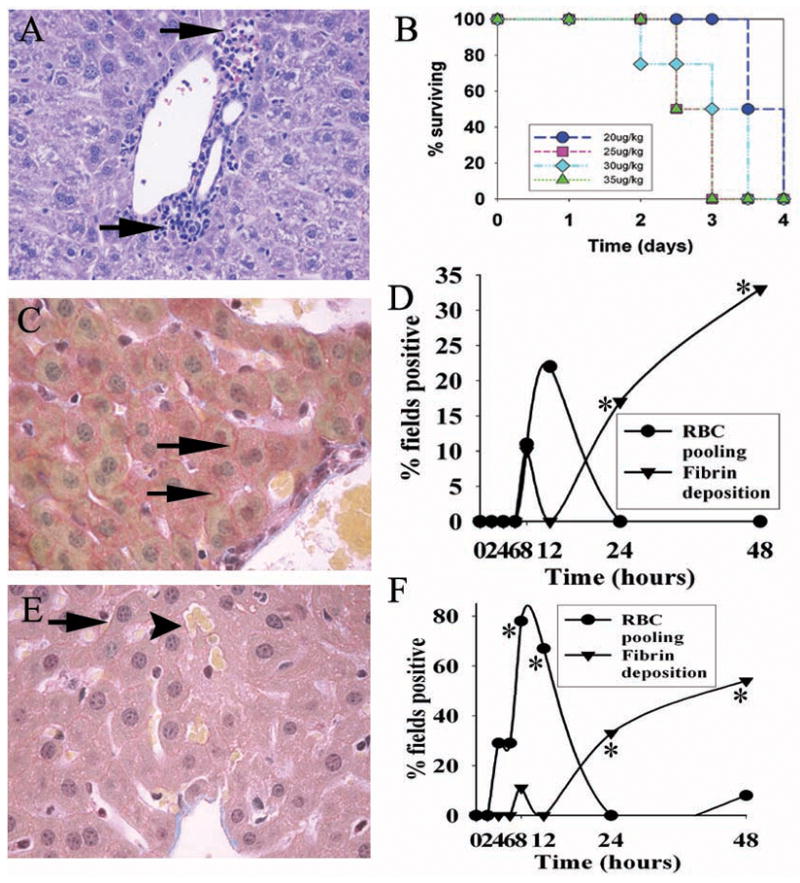

Figure 2.

Hepatic injury and lethality in a mouse model of ricin intoxication. A. H&E stain of peri-portal liver 48 hours following ricin challenge, showing nests of leukocytes (arrows) adjacent to portal tracts. B. Lethality dose-response after ricin administration i.p. at the doses indicated, with 10 mice per group. C. Fibrin in the peri-portal area of liver 48 hours after ricin challenge (40 μg/kg). Deposition of fibrin (arrows) occurred between hepatocytes and was detectable by MSB staining (see Materials and Methods). D. Time course of fibrin deposition in the peri-portal liver after ricin challenge. This is shown as the percent of high-powered (400×) microscopic fields showing fibrin deposits around hepatocytes. E&F, same as C&D, except that the centro-lobular liver was studied. RBC pooling (arrowhead in panel E) refers to aggregates of red blood cells two or more times larger than present in normal liver sinusoids, and scored as the percent of high-powered fields positive for the finding. For D & F, findings are representative of two independent studies, with a total of 4 mice per time point. *, p< 0.04, comparing number of fields showing fibrin deposition in centro-lobular and peri-portal areas at 24 and 48 hours with that at 0–4 hours. **, p<0.05, comparing number of fields showing RBC congestion at 0 and at 8 hours. Magnification: A, C, and E, 400×.

The presence of lethargy in our model as well as hypoglycemia reported after exposure to the ricin holotoxin (11) suggested the liver may be a target organ for this toxin, given that hepatic glycogen is the principal site for carbohydrate storage in the host, and is integral to maintaining glucose homeostasis. Therefore, we examined whether inflammation and/or injury were present in the liver that might contribute to dysfunction of glycogen-containing hepatocytes. Histological assessment of the liver in these mice showed generalized hypercellularity, as well as focal areas of mixed inflammatory cells, particularly near the peri-portal zones (Fig. 2A). Further, specialized staining (MSB) revealed progressive fibrin deposition in the liver. Fibrin was simultaneously detected in the peri-portal and centro-lobular areas (Fig. 2C & D; 2E & F, respectively) at 24 hours after challenge with ricin, and by 48 hours involved greater than 30% of microscopic fields studied (p < 0.04) (Fig. 2D & F). In addition, red blood cell congestion of the hepatic parenchyma was observed at 4–6 hours, but was transient, diminishing by 24 hours (Fig. 2D–F). Together, these findings suggest that inflammation and subsequent injury, as indicated by fibrin deposition, is present in the liver after ricin exposure, and may be an important antecedent of lethargy and death in the model.

Nature of hepatic inflammation after ricin challenge

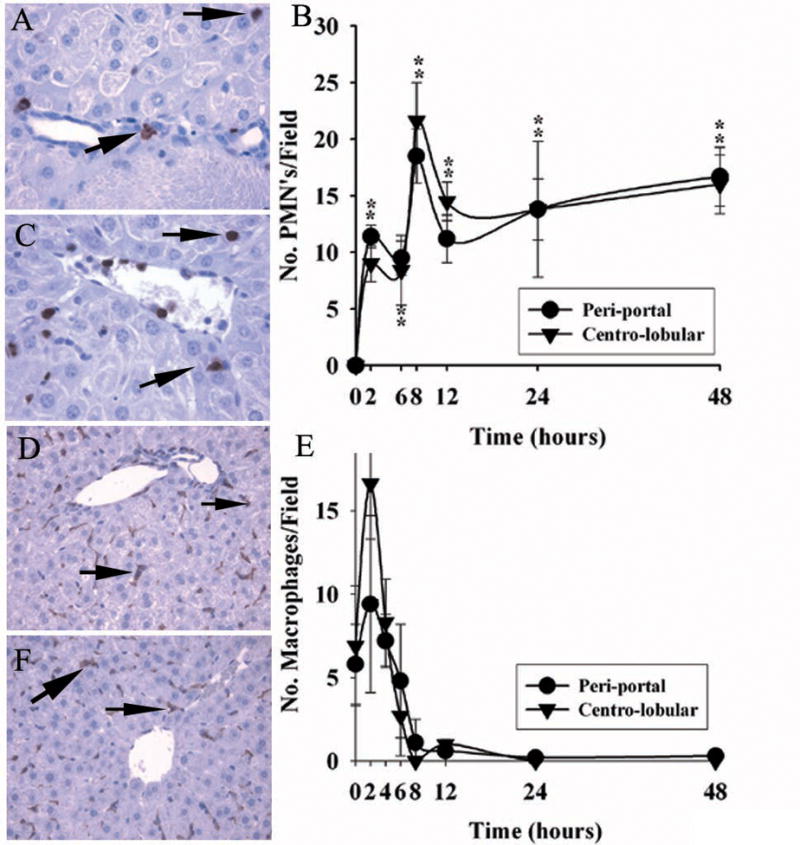

To define the nature of the inflammatory infiltrate in the liver associated with lethal ricin intoxication (Fig. 2A), mice were exposed to ricin, euthanized at pre-established times, then examined for the number, distribution and time course of two inflammatory cell types, neutrophils and macrophages, associated with parenchymal injury in other mouse models using binary toxins (10,13). Initially, the number of both cell types rose rapidly above baseline after ricin challenge (Fig 3B & E), with a distribution that was diffuse throughout the liver, involving both the peri-portal and centro-lobular hepatic zones (Fig 3A,C,D & F). However, quantification of each cell type at later time points revealed marked differences. That is, the number of neutrophils present in hepatic parenchyma remained robust (>10/HPF; Fig 3B), while hepatic macrophage/Kupffer cell numbers peaked at 2–4 hours, then rapidly became nearly undetectable by 8–12 hours and beyond (Fig. 3E). These results suggest that powerful and sustained chemotactic stimuli for neutrophil and macrophage invasion of liver arise quickly following systemic exposure to ricin. Nevertheless, hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells, while numerous at two hours (e.g., 9–17 cells/HPF), receded over the next 10 hours and did not re-accumulate.

Figure 3.

Migration of leukocytes to liver after ricin challenge in vivo. A & C. Immuno-reactive neutrophils in peri-portal ( panel A) and centro-lobular ( panel C) areas of liver 48 hours after toxin administration. B. Quantification of neutrophils as number of 7/4+ immuno-reactive cells per high-powered field 0–48 hours after toxin was given. D & F. Immuno-reactive macrophages in peri-portal (panel D) and centro-lobular (panel F) hepatic areas 2 hours after toxin challenge. E. Number of F4/80+ immuno-reactive cells per HPF of liver 0–48 hours after administration of toxin. Repeat studies showed loss of stained cells occurred over 8–12 hours. Findings are representative of two independent studies with a total of 4 mice per time point. Magnification: 400× (A, C); 200× (D, E). *, p < 0.01, number of leukocytes per HPF at the designated hours compared with that at 0 hours. **, p < 0.02, number of macrophages per HPF at 0 hours compared with that at 2 hours in the peri-portal area.

Chemokine gene activation in the liver after challenge with ricin

To determine the chemotactic and adhesion molecules likely responsible for neutrophil and macrophage entry into the liver, mRNA isolated from hepatic tissue was analyzed by microarray at 0, 2 and 24 hours following lethal challenge with ricin. Biotinylated cRNA made with T7 RNA polymerase was hybridized with oligonucleotides on Affymetrix Gene Chips, and the results analyzed by GeneX VA software (Table 1). Among chemotaxins for neutrophils, CXCL1/KC and CXCL2/MIP-2 mRNA demonstrated a 16-and 3-fold increase, respectively, over control values at 2 hours following ricin challenge, and continued to be increased at 24 hours (>40-fold over baseline). Genes for other chemokines able to initiate neutrophil migration (C5a, PAF, LTB4, NAP2, NCFA) were not induced (≤2-fold increased; Table 1 and data not shown). For chemokines with selectivity for macrophages, four were modestly elevated (>2.9-fold) at 2 hours, but only two of these [CCL2/MCP-1(JE), CCL3/MIP-1α] showed sustained and progressive increases over time (Table 1). Among molecules expressed on endothelium and important for adhesion of circulating inflammatory cells before diapedesis, gene products for two ( ICAM-1 and VCAM) were expressed in the liver at two hours after ricin exposure, but only ICAM showed a sustained increase (>21-fold at 24 hours; Table 1).

Table 1.

Microarray Analysis of Liver mRNA: Identification of Genes Up-regulated after in vivo Challenge with Ricin

| Cell Type | Gene | 2 hours | 24 hours |

|---|---|---|---|

| CXCL1/KC | 16.6 | 41.2 | |

| CXCL2/MIP-2 | 3.1 | 150.9 | |

| PMN’s | ICAM | 3.6 | 21.3 |

| VCAM | 2.6 | 0.9 | |

| VLA4 | 5.1 | 0.4 | |

| MΦ | CCL2/MCP-1/Je | 3.3 | 27.4 |

| CCL5/RANTES | 2.9 | 1.2 | |

| CCL3/MIP-1α | 3.5 | 40.1 | |

| CCL4/MIP-1β | 8.3 | 5.3 | |

| CXCL10/IP-10 | 0.9 | 2.2 | |

| CCL1/TCA | 1.5 | 10.2 | |

| VCAM | 2.6 | 0.9 |

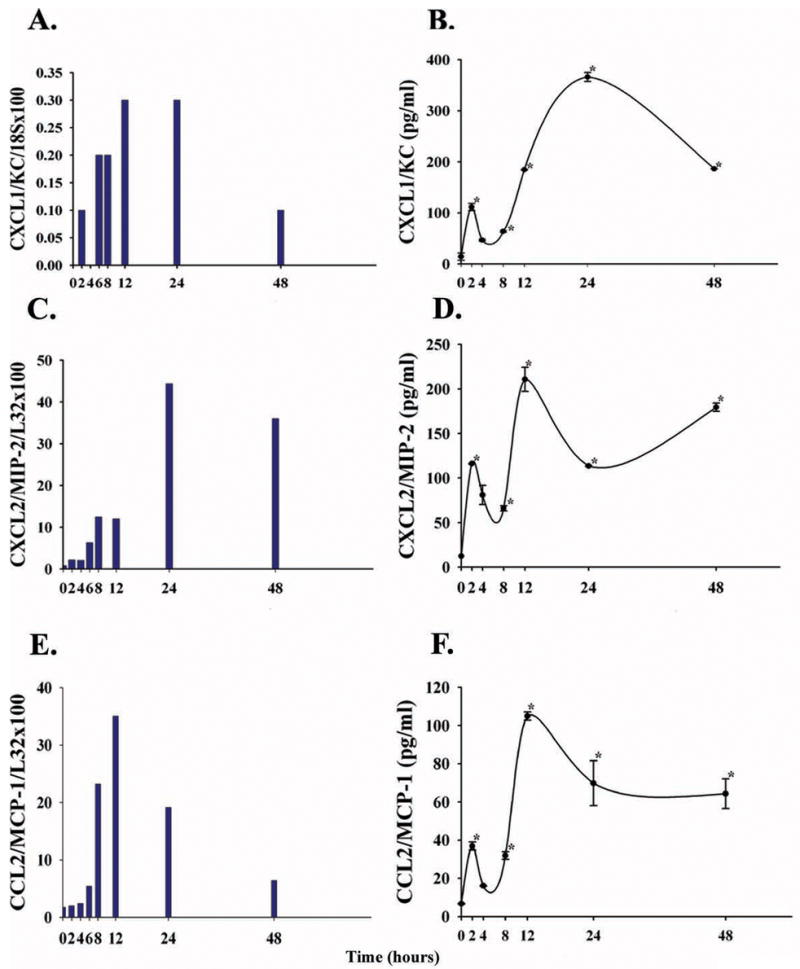

To independently confirm the microarray findings and to acquire a more complete time course for transcription and translation of specific chemokines, total hepatic RNA and protein homogenates were temporally collected and analyzed by additional techniques (see below) following in vivo challenge with a lethal dose of ricin. Messenger RNA and protein belonging to chemokines relevant to neutrophil migration (CXCL1/KC and CXCL2/MIP-2) were detectible at 2 hours, rose further over 6–12 hours after ricin exposure, and were sustained (Fig. 4). Similarly, mRNA and protein for the macrophage chemokine CCL2/MCP-1 was evident at 2 hours and remained sustained, as did that for MIP-1α (Fig. 4 and data not shown). Together, as determined by RPA, Northern blotting and dual antibody ELISA, these studies suggest that potent chemotactic stimuli for inflammatory cell migration into the liver persist for days in the host after a single parenteral lethal challenge with ricin. Thus, the disappearance of hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells over 8–12 hours following ricin exposure was not due to the absence of a locally generated relevant chemokine.

Figure 4.

Chemokine mRNA and protein in the liver over 0–48 hours after a single injection of ricin (40 μg/kg) in C57BL/6 mice. A,C,E. Messenger RNA for CXCL1/KC, CXCL2/MIP-2, and CCL2/MCP-1(JE) is shown as a ratio of specific message/value of a house-keeping gene (18S or L32), determined by Northern blotting (CXCL1/KC) or by ribonuclease protection assay (CXCL2/MIP-2, CCL2/MCP-1). Specific mRNA for these chemokines was not detected at 0 hours. Two mice were analyzed per time point. B,D,E. Chemokine protein in liver homogenates after ricin challenge, quantified by paired antibody enzyme-linked immuno-absorbent assay, described in Materials and Methods. Shown is the mean +/− 1 SD. Homogenates were analyzed in duplicate from each of two mice per time point (14 mice total per cytokine). *, p< 0.05, comparing values at the indicted hours with that at 0 hours.

Glycogen in the liver after ricin challenge

Given the prolonged presence of hepatic inflammation following ricin challenge in vivo, we postulated that important hepatic functions such as synthesis and storage of carbohydrate as glycogen would be disrupted. Therefore, we serially assessed the presence and distribution of liver glycogen as determined by PAS staining of individual hepatocytes in tissue sections following ricin administration (Fig. 5). The number of PAS+ hepatocytes remained at the baseline value of 12–18 cells/field over the first 4–6 hours before it decreased markedly at 8–12 hours, both in peri-portal areas containing the bile ducts, hepatic artery and portal vein ((Fig. 5 A & B), and in the centro-lobular areas surrounding the central vein (Fig. 5C & D). Subsequently, hepatocytes did not re-accumulate glycogen over the following 40 hours, and this corresponded with progressive and, ultimately, profound hypoglycemia in the mice (Fig. 5E & F). In contrast, control mice, receiving vehicle (normal saline) without ricin, demonstrated stable blood glucose levels (> 100 mg/dl), and maintained substantial hepatic carbohydrate stores at 24 and 48 hours (> 23 +/− 4 PAS+ cells/field). Taken together with experiments described in Figures 2 & 3, these studies suggest that lethal challenge with ricin leads to a chemokine-driven mixed inflammatory infiltration of liver by 2 hours, persistent loss of liver glycogen by 8–12 hours, progressive severe hypoglycemia by 12–24 hours, and death by day 4.

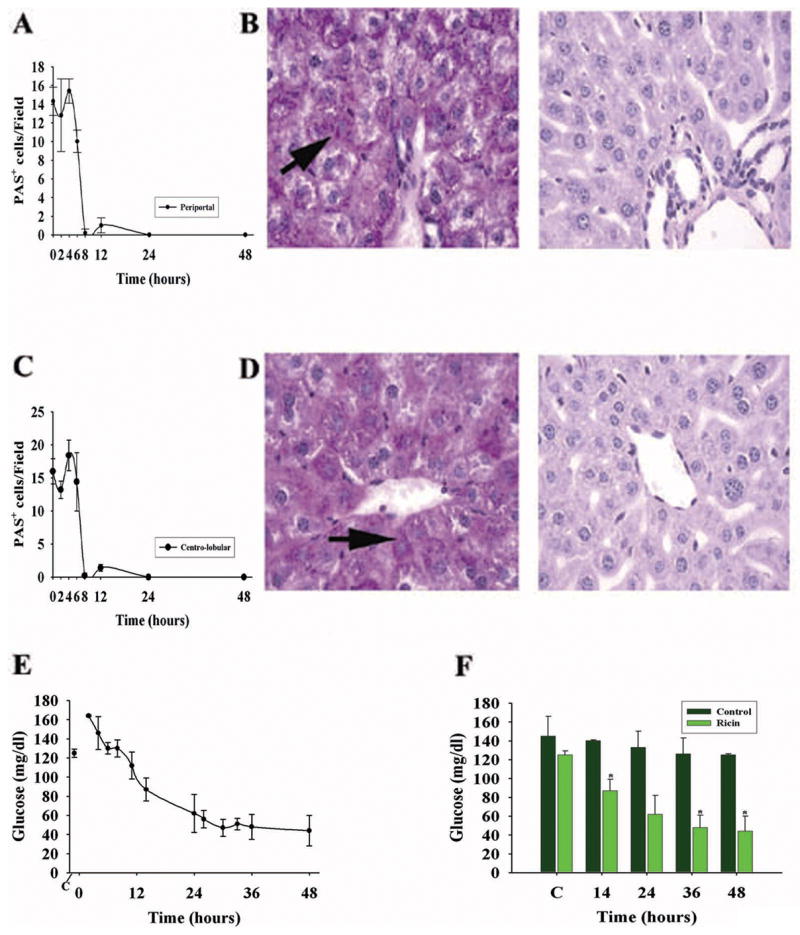

Figure 5.

Hepatic glycogen and hypoglycemia following ricin challenge (40 μg/kg) in the C57BL/6 mouse. A. Time course for the presence of peri-portal glycogen-containing hepatocytes, displayed as the number per high power field, detected as periodic acid Schiff (PAS+) -positive cells. B. PAS staining of peri-portal hepatic parenchyma at 0 and 8 hours (B, left and right panels, respectively) after ricin exposure. Arrows, individual PAS+ hepatocytes. C. Number of PAS+ cells per HPF in the centro-lobular liver from 0 to 48 hours following ricin. D. Examples of PAS+ hepatocytes at 0 and 8 hours (D, left and right panels, respectively) following toxin. For A & C, results are representative of two independent studies, each with 2 mice per time point (total of 4 mice per time point, or 32 mice total). Complete disappearance of glycogen took up to 12 hours in repeat studies. PAS+ cell number at 8–48 hours was significantly different from that at 0 hours (p <0.001). E. Blood glucose in mice following ricin challenge, as determined by glucometer on tail vein blood. F. Comparison of blood glucose levels in saline (control)- and ricin-challenged mice at selected times before and after ricin challenge. *, p < 0.02, comparing ricin-treated versus vehicle-treated mice at the indicated time points (14, 36, and 48 hours). C, blood glucose prior to challenge with ricin or vehicle. Magnification: B, D (400×).

Monoclonal anti-ricin A chain immunoglobulin diminishes hypoglycemia and prevents lethality

One mechanism to account for events in the liver described above is to postulate that holotoxin in the intra-peritoneal space disseminates intravascularly to reach vital organs including the liver and kidney. This would suggest that hypoglycemia and death in ricin challenged mice could be ameliorated or prevented by the presence in the intravascular space of anti-ricin immunoglobulin capable of immuno-neutralizing toxin. We studied this by administering ricin A chain-specific monoclonal immunoglobulin -- 20 μg each of RAC 17, 18, 23 -- to mice one hour prior to a lethal challenge with ricin (Fig. 6). At 20, 27, and 36 hours following ricin exposure, mice pre-treated with anti-ricin immunoglobulin maintained their blood glucose levels (mean > 100 mg/dl) when, at the same time, controls given irrelevant isotype-matched immunoglobulin in the same amount became progressively hypoglycemic (Fig 6A; p<0.05). Further, when these mice were followed over four days, all (10/10) anti-ricin immunoglobulin-treated mice survived, while 9 of 10 mice receiving irrelevant immunoglobulin died (Fig 6B).

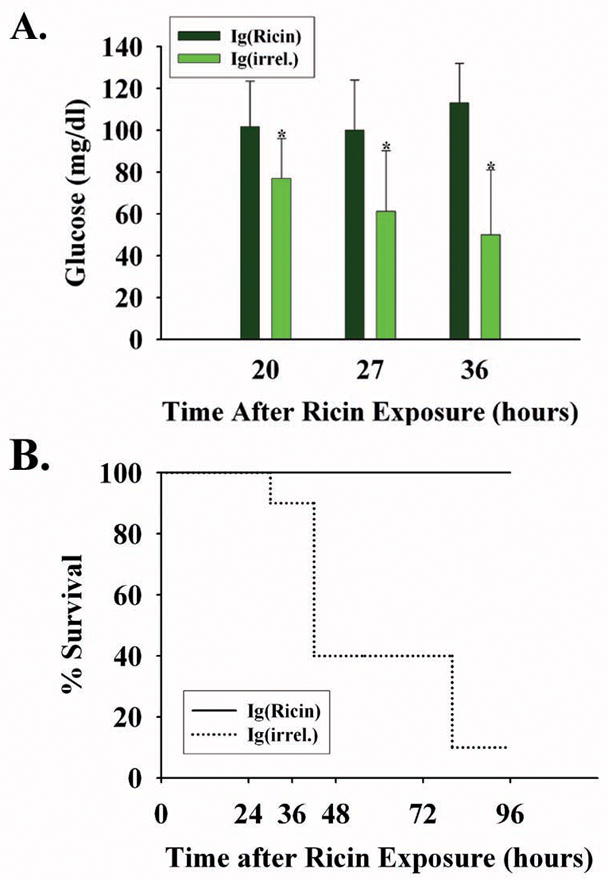

Figure 6.

Blood glucose and lethality after pre-treatment with monoclonal immunoglobulin to ricin A chain. Mice were injected intravenously with monoclonal immunoglobulin to ricin A chain (RAC 17, 18 and 23; 20 μg/mouse each; N=10) or with irrelevant immunoglobulin matched for isotype and quantity (N=10) one hour prior to challenge with the ricin holotoxin (40μg/kg). A. Blood glucose levels (mean +/− 1 SD) at three intervals after ricin injection. *, p < 0.02, comparing RAC- versus irrelevant antibody-injected mice at 20, 27 and 36 hours following ricin challenge. B. Percentage of mice pre-treated with immunoglobulin which survived lethal ricin exposure. Ig(ricin) mice received 20 μg each of RAC 17, 18, and 23; Ig(irrel) mice were administered monoclonal IgG1 and IgG2A in the same quantity and in the same proportion as was received by the experimental group.

Interestingly, the single surviving mouse in the latter group maintained a blood glucose of > 105mg/dl over the first 72 hours. In mice treated with ricin-specific monoclonal immunoglobulin, behavior (activity level, posture) and appearance (hair) remained unaltered, while these parameters progressively deteriorated in 9 of the 10 controls that succumbed (data not shown). In this group, mice that experienced marked hypoglycemia early (mean glucose, 42+/− 7 mg/dl at 27 hours; N=6) were the first to expire, all by 48 hours. The remaining mice had more moderate hypoglycemia (mean glucose, 90+/− 27 mg/dl at 27 hours; N = 4) and lived longer, succumbing at 72–96 hours following ricin challenge. A subsequent experiment confirmed these findings, with survival of all anti-ricin immunoglobulin-treated mice (10 of 10). These data suggest that ricin in the peritoneal cavity first traverses the intravascular space, where it is bound by 160,000 dalton IgG before reaching vital organs, thereby abrogating hypoglycemia and death in the model.

Benefit of post-exposure ricin-specific monoclonal antibody

To determine whether immunoglobulin to ricin A chain would benefit the host after challenge with a lethal dose of ricin, the same regimen of monoclonal antibodies (RAC 17, 18, and 23, at 20 μg/mouse each) was administered intravenously once to mice, at 1, 3, 6, 8, 10 or 14 hours after toxin. Blood sugar levels were determined daily, and mice were monitored for signs of illness. Delay of immunoglobulin administration for 1, 3, or 6 hours after ricin was associated with 100% survival (10/10 animals in each group), while a similar delay in receiving irrelevant immunoglobulin matched for isotype and amount was associated with death of all mice by day 5 (Fig. 7B). Compared to saline-injected, ricin-free control mice, mild hypoglycemia was detected on days 1 & 2 when ricin-specific monoclonal antibody was delayed up to three hours after toxin exposure (control and 3 hour delay data shown in Fig. 7A), but blood glucose recovered by day 3. On the other hand, delay in administration of ricin-specific monoclonal antibody for 8 or 10 hours after ricin challenge was associated with minimal mortality (10% by day 5) and more marked hypoglycemia, with full recovery of glucose homeostasis requiring four days (Fig 7A & B). However, when the same monoclonal antibody regimen was delayed for 14 hours after ricin challenge, profound hypoglycemia was seen on days 1 & 2 where blood glucose decreased to < 50% (e.g., <72 mg/dl) of its pre-toxin level, and this was associated with 70% mortality by day 5 (Fig. 7 A & B). Surviving mice regained a blood glucose level to near that of controls on days 4–8, and demonstrated a clear survival advantage over mice receiving irrelevant immunoglobulin (Fig. 7A & B). Overall, these data suggest that 20 μg quantities of each of three monoclonal antibodies to ricin A chain protect 90% of mice when administered up to 10 hours after a lethal challenge with ricin, and that protection is associated with an early (day 1 & 2) blunting of ricin-induced hypoglycemia.

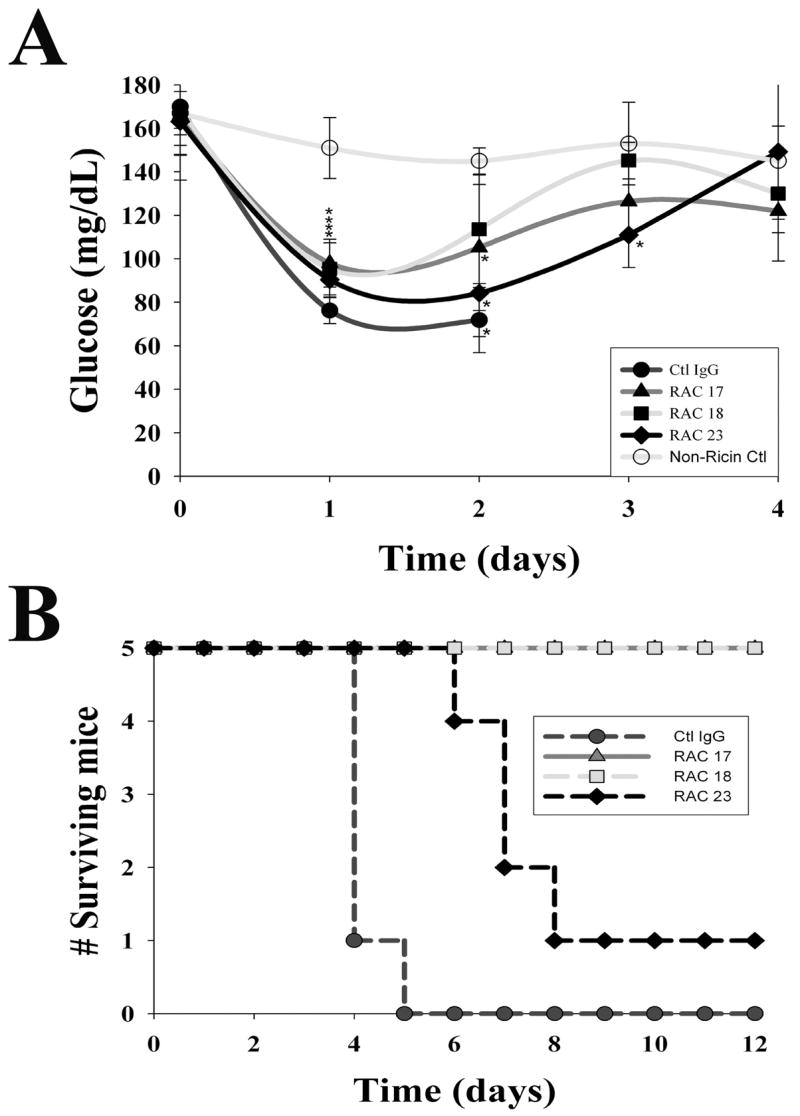

Figure 7.

Effect of anti-ricin monoclonal immunoglobulin administered after ricin challenge. At designated time intervals after injection of ricin (40 μg/kg), C57BL/6 mice were administered 20 μg each of RAC 17, 18, and 23 i.v., or the same quantity of isotype-matched monoclonal immunoglobulin; assessed every 24 hours for blood glucose,; and monitored for survival. A. Blood glucose of surviving mice by treatment group (N=10/group). One group did not receive ricin (non-ricin ctl) and one group was administered ricin then irrelevant immunoglobulin (ctl IgG). B. Survival shown as the percentage of mice alive in each treatment group (N=10/group). Note that 100 % of mice receiving irrelevant immunoglobulin succumbed by day 4, while 30% of mice administered specific immunoglobulin 14 hours after ricin exposure survived. Survival curves overlap for mice receiving anti-ricin antibody 8 and 10 hours after ricin challenge.

Individual monoclonal antibodies to ricin A chain are protective

The studies above were conducted using three well-characterized monoclonal antibodies used in 20 μg amounts each, and compared to equal quantities of isotope-matched immunoglobulins. Because each monoclonal antibody is directed to a known but unique epitope on the A subunit of ricin A chain (data in reference 11), we sought to define the possible benefit of each individually for post-exposure survival and for normalizing blood glucose. To study this, groups of mice were challenged with ricin, then administered six hours later a 20 μg quantity of RAC 17, 18, 23, or irrelevant IgG. Compared with saline-injected (non-ricin) control mice, all groups experienced marked hypoglycemia with those receiving RAC 23 needing the longest time to regain glucose levels similar to those of controls (Fig. 8A). Nevertheless, all groups demonstrated normalization of blood glucose by day 4 except those receiving irrelevant immunoglobulin, all of whom died by day 5 (Fig. 8B). Despite recovery of serum glucose to > 100 mg/dl by day 3, mice receiving RAC 23 died on days 6–9 after challenge with ricin (Fig. 8B). Together with prior data (11), we conclude that RAC 17 & 18 monoclonal antibodies binding to specific amino acid sequences on ricin A chain (HAEL and QXXWXXA) promoted long term survival. In contrast, RAC 23 binding to GTXS on ricin A chain allowed short term survival with recovery from hypoglycemia, but was insufficient to retard long-term mortality by itself.

Figure 8.

Maintenance of glucose homeostasis and host survival after administration of individual monoclonal antibodies to ricin A chain. Six hours following ricin challenge (40 μg/kg), mice were intravenously given 20 μg of a single immunoglobulin (RAC 17, 18, 23, or irrelevant IgG), then monitored for blood glucose every 24 hours and followed for survival. The data are representative of two independent studies. A. Blood glucose by treatment group (N=5/group) and shown as the mean +/− 1 SD. Glucose values in all groups of ricin-challenged mice diminished on day 1 before normalizing by day 3–4. * indicates p < 0.05, comparing ricin and antibody treated mice with non-ricin controls. Mortality in the irrelevant IgG group after day 2 was large, and the group mean blood glucose was not calculated. B. Survival among mice administered a single monoclonal immunoglobulin. Groups of mice were followed, with early deaths occurring among mice receiving control IgG, and a later loss of mice in those administered RAC 23. Mice not challenged with ricin are shown as ‘non-ricin controls.’

Regression of intra-hepatic pathobiology when antibody administration is delayed after toxin exposure

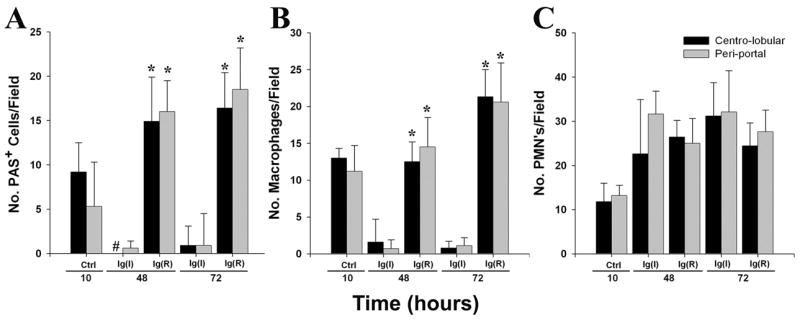

The studies above demonstrated that a standard regimen of monoclonal antibodies (RAC 17, 18, and 23, at 20 μg/mouse each) reduced mortality in 90% of mice, even when administered 10 hours following a lethal ricin challenge. Benefit included not only long-term survival but normalization of blood glucose. To discern the mechanism underlying host recovery, we examined the effect of post-exposure ricin A chain-specific monoclonal antibody on major intra-hepatic events observed during the studies described above in ricin challenged mice (Figs 3 & 5). By 48 hours after ricin exposure, administration of anti-ricin monoclonal antibodies was associated with restoration of carbohydrate stores in hepatocytes (Fig. 9A, p<0.001), a return of F4/80+ immuno-reactive macrophages (Fig. 9B, p<0.001), but little change in the number of neutrophils migrating to the liver in either the centro-lobular or peri-portal regions (Fig 9C). In contrast, mice receiving irrelevant monoclonal immunoglobulin matched for isotype and quantity demonstrated progressive and persistent loss of hepatic glycogen as well as disappearance of macrophges/Kupffer cells (Figs 9A & B) at 48 and 72 hours after ricin challenge. These data indicate the capacity of post-exposure antibody to abrogate critical elements of ricin-induced intra-hepatic pathobiology associated with host death. While anti-ricin antibody in the intravascular space may limit toxin accumulation in several organs, its ability to reverse profound and prolonged hypoglycemia, considered the cause of death in the model (11), points to the centrality of hepatic events in the pathogenensis of ricin intoxication.

Figure 9.

Intra-hepatic findings following 10 hour delay in immunoglobulin administration. Mice were administered i.v. 60 μg of immunoglobulin 10 hours following a lethal ricin challenge (40μg/kg), then euthanized at 48 or 72 hours subsequent to toxin exposure. Control mice were studied just before immunoglobulin administration; peri-portal and centro-lobular regions were studied. A. Number of PAS+ (carbohydrate-containing) cells per field. *, p<0.001, comparing mice receiving anti-ricin monoclonal antibody (equal quantities of RAC 17, 18, and 23), designated Ig(R), with those administered irrelevant antibody matched for quantity and isotype, denoted as Ig(I). #, no centro-lobular PAS+ hepatocytes observed at 48 hours in mice receiving Ig(I). B. Number of F4/80+ immuno-reactive macrophages per field. *, p<0.001, comparing the same groups as in A. C. Number of 7/4+ immuno-reactive neutrophils per field. No significant differences were found when mice receiving anti-ricin monoclonal immunoglobulin were compared to those receiving irrelevant immunoglobulin. For A, B, and C, results are representative of two independent studies, each with 2 mice per time point (total of 4 mice per time point).

DISCUSSION

Ricin is a potent plant toxin of 65 kDa molecular mass whose A subunit exhibits an RNA N-glycosidase activity upon entering cell cytosol, resulting in inactivation of ribosomes and loss of protein synthesis with subsequent cell death (4,5). While cells in most tissues of the toxin-exposed host would be subject to these actions of ricin, identification of organs that are particularly vulnerable to the toxin, and mechanisms underlying that vulnerability, are not clear. The current investigation identifies the liver as an important site of inflammation and injury that is associated with hypoglycemia in the ricin-exposed host. We have defined the source, timing, and identity of local chemokines and adhesion factors relevant to the infiltrating cells at the initiation of hepatic inflammation. In addition, we have elucidated the capacity of antibody directed at specific epitopes on the A subunit of ricin to ameliorate toxin-induced hypoglycemia, intra-hepatic events, and lethality after exposure to ricin in a murine model.

The observation that monoclonal antibody directed at ricin A chain, injected into the intravascular space as late as 10 hours following lethal ricin challenge, averted and/or diminished hypoglycemia and prevented death in the model suggests the importance of several pathophysiological processes occurring in the liver following ricin exposure. First, our data indicate that delivery of toxin to target organs takes place via the intravascular space and occurs over many hours, perhaps days following parenteral ricin exposure. Second, the ongoing injury resulting from the quantity of toxin initially reaching the liver and the associated inflammation is limited and can be compensated for by residual healthy hepatocytes up to 10 hours post-exposure. Continued arrival and accumulation of toxin over time, however, likely increases the number of cells in the liver to which toxin is bound, resulting in RBC pooling, loss of glycogen stores in hepatocytes, disappearance of hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells (8–12 hours), and fibrin deposition (24–48 hours). Thus we suggest that there is an interval of about 10 hours following ricin challenge during which the dose of toxin that has reached the liver is not sufficient to irreversibly damage some or all of the hepatic parenchymal and non-parenchymal cells, allowing intervention at this stage to be possible and beneficial. Indeed, immunohistochemical staining of the liver in mice administered ricin A-chain-specific immunoglobulin 10 hours following ricin challenge showed a return of hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells by 48 hours that persisted, and a simultaneous re-accumulation of glycogen in hepatocytes, while neutrophil infiltration was not significantly altered. Thus, in terms of inflammatory events, host survival was associated with the presence of a normal or an increased number of hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells and was independent of infiltrating neutrophils. That is, the presence of neutrophils in the liver is not sufficient for host survival from a lethal exposure to ricin. Nevertheless, neutrophils, when present with macrophages, may play an important role in response to binary toxins such as ricin.

Prior studies have shown the Kupffer cells, derived from circulating monocytes, represent 35% of non-parenchymal liver cells in the adult mouse, are an important component of innate immunity, and are the first point of contact for incoming pathogen/toxin-laden portal blood (14,15). Evidence suggests that bacterial pathogens bind to the Kupffer cell surface via carbohydrate-lectin interactions (16), then are internalized and killed by neutrophils which are also adherent to Kupffer cells (17). Further, studies indicate the importance of Kupffer cells in eliminating activated neutrophils, thereby suppressing their production of degradative enzymes (18). Taken together with evidence that activated Kupffer cells are necessary for optimal regeneration of hepatocytes through release of TNF-α and IL-6 (20,21), the loss of Kupffer cells at 8–12 hours from the liver of ricin-challenged mice is a critical effect of ricin intoxication, causing loss by the host of several protective and regenerative pathways that are important for survival. We postulate that this results from ricin B chain lectin binding to galactose or mannose on the surface of Kupffer cells, resulting in death of these cells, unchecked release of degenerative enzymes from neutrophils, and loss of hepatocyte glycogen stores with profound and fatal hypoglycemia. It is likely that the rapid Kupffer cell repletion, observed when immunoglobulin is administered 10 hours after ricin, comes from the circulating monocyte pool, since hematopoetic stem cells present in the adult murine liver may take 14–26 days for local repletion of macrophages (22). Further, in the current study, immunoglobulins directed at amino acid sequences HAEL and QXXWXXA but not GTSX on ricin A chain were associated with long-term survival after lethal challenge with ricin. By localization of the binding sites for each monoclonal antibody on the 3 dimentional structure of ricin A chain (11), it becomes clear that binding to the active site of A chain’s glycosidase may not be necessary to achieve efficacy in vivo.

From prior work (3–6) and from the current studies, a unified pathway for hepatic pathobiology after host exposure to ricin can be suggested. After parenteral exposure to ricin, the toxin gains access to the blood stream and travels to the vascular endothelium of solid organs, perhaps transported on serum proteins or on cells in the blood. Once intra-cellular, ricin rapidly induces expression of chemokines CXCL1/KC, CXCL2/MIP-2 mRNA and protein in the liver as well as ICAM on endothelium of capillaries and arterioles to effect leukocyte migration from the blood stream into hepatic tissue by 2 hours after challenge. Hepatic macrophages/Kupffer cells disappear despite the presence of chemokine CCL3/MCP-1 locally. Subsequently, we suggest that the toxin itself and/or products released by activated leukocytes in the liver at 10 hours or more after initial toxin exposure lead to irreversible damage to hepatocytes, resulting in loss of glycogen stores, persistent and profound hypoglycemia, and death of the host. We suggest that recovery of hepatic macrophage/Kupffer cells and repletion of hepatocyte glycogen occurs when specific antibody limits use of the vascular pathway for toxin delivery to the liver for up to 10 hours after challenge. Alteration in glycogen synthetic and degradative liver enzymes, while beyond the scope of the current work, is of interest and is the subject of current investigation. Furthermore, for considerable segments of the human population, exposure to ricin may not be preventable in a bio-terrorist setting. Our study suggests, however, that the use of anti-ricin antibodies to reduce the quantity of active toxin reaching target organs provides an effective and pragmatic strategy for post-exposure therapeutic intervention.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by USPHS awards R01 AI024431 (to T.G.O.), R01 AI059376 (to S.H.P.), a Development Grant under U54 AI057168 (to J.K.R), and a small project under U54 AI057156 (to S.H.P.).

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper: KC, a CXC chemokine now designated CXCL1/KC; MIP-2, macrophage inhibitory protein 2, now named CXCL2/MIP-2; MSB, Martius yellow-Brilliant Crystal Scarlet-aniline Blue technique; PAS, periodic acid Schiff stain; RAC, ricin A chain-specific monoclonal antibody; Stx2, Shiga toxin 2; RPA, ribonuclease protection assay.

LITURATURE CITED

- 1.Choi J, Au J-HJ. Mechanisms of liver injury. III. Oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of hepatitis C virus. Am J Physiol (Gastro & Liver Physiology) 2006;290:G847–51. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00522.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarro VJ, Senior JR. Drug-related Hepatotoxicity. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:731–739. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook DL, David J, Griffiths GD. Retrospective identification of ricin in animal tissues following administration by pulmonary and oral routes. Toxicology. 2006;223:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Endo Y, Mitsui K, Motizuki M, Tsurugi K. The mechanism of action of ricin and related toxin lectins on eukaryotic ribosomes. The site and the characteristics of the modification in 28S ribosomal RNA caused by the toxins. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:5908–5912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lord MJ, Jolliffe NA, Marsden CA, Pateman CSC, Smith DC, Spooner RA, Watson PD, Roberts LA. Ricin: mechanisms of cytotoxicity. Toxicol Rev. 2003;22:53–65. doi: 10.2165/00139709-200322010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korcheva V, Wong J, Corless C, Lordanov M, Magun B. Administration of ricin induces a severe inflammatory response via non-redundant stimulation of ERK, JNK, and P38 MAPK and provides a mouse model of hemolytic uremic syndrome. Am J Path. 2005;166:323–339. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62256-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen UF, Jobanputra P, Barton P, Jowett S, Bryan S, Clark W, Fry-Smith A, Buris A. A systematic review of the effectiveness of adalimumab, etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in adults and an economic evaluation of their cost-effectiveness. Health Tech Assess. 2006;10:1–22. doi: 10.3310/hta10420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bisikirska B, Herold C, Kevan C. Use of anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody to induce immune regulation in type 1 diabetes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1037:1–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1337.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferrara N, Damico L, Shams N, Lowman H, Kim R. Development of Ranibizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antigen binding fragment as therapy for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26:859–70. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000242842.14624.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roche JK, Keepers TR, Gross LK, Seaner RM, Obrig TG. CXCL1/KC and CXCL2/MIP-2 are critical effectors and potential targets for therapy of Escherichia coli 0157:H7-assoicated renal inflammation. Amer J Path. 2007;170:526–537. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maddaloni M, Cooke C, Wilkinson R, Stout AV, Eng L, Pincus SH. Immunological characteristics associated with the protective efficacy of antibodies to ricin. J Immunol. 2004;172:6221–6228. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.6221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook HC. Theory and practice of histological techniques. In: Bancroft JD, Stevens, editors. Manual of Histological Demonstration Techniques. 2. p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Keepers T, Psotka M, Gross L, Obrig T. A murine model of HUS: Shiga toxin with lipopolysaccharide mimics the renal damage and physiological response of human disease. J Amer Soc Neph. 2007;17:526–37. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006050419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Philips MJ, Poucell S, Patterson J. An atlas and text of ultrastructural pathology. Liver. 1987:1–32. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox ES, Thomas P, Broitman SA. Comparative studies of endotoxin uptake by isolated rat Kupffer and peritoneal cells. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2962–6. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.2962-2966.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker GA, Picut CA. Liver immunobiology. Toxicol Pathol. 2005;33:52–62. doi: 10.1080/01926230590522365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Perry A, Ofek I. Inhibition of blood clearance and hepatic tissue binding of Escherichia coli by liver lectin-specific sugars and glycoproteins. Infect Immun. 1984:257–62. doi: 10.1128/iai.43.1.257-262.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregory SH, Wing EJ. Neutrophil-Kupffer cell interaction: a critical component of host defenses in systemic bacterial infections. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:239–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Konowal A, Westcott PW, Henson PM. Macrophages that have ingested apoptotic cells in vitro inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production through autocrine/paracrine mechanisms involving TGF-β, PGE2, E2 and PAF. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:890–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Akerman P, Cote P, Yang SQ, et al. Antibodies to tumor necrosis factor inhibit liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Am J Physiol. 1992;263:G579–85. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1992.263.4.G579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cressman DE, Greenbaum LE, DeAngelis RA, Ciliberto G, Furth EE, Poli V, Taub R. Liver failure and defective hepatocyte regeneration in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Science. 1996;274:1379–83. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5291.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taniguchi T, Toyoshima T, Fukao K, Nakuchi H. Presence of hematopoietic stem cells in the adult liver. Nat Med. 1996;2:198–203. doi: 10.1038/nm0296-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]