Abstract

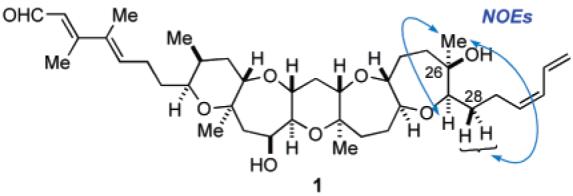

Total synthesis of structure 1 originally proposed for brevenal, a nontoxic polycyclic ether natural product isolated from the Florida red tide dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis, was accomplished. The key features of the synthesis involved (i) convergent assembly of the pentacyclic polyether skeleton based on our developed Suzuki–Miyaura coupling chemistry and (ii) stereoselective construction of the multi-substituted (E,E)-dienal side chain by using copper(I) thiophen-2-carboxylate (CuTC)-promoted modified Stille coupling. The disparity of NMR spectra between the synthetic material and the natural product required a revision of the proposed structure. Detailed spectroscopic comparison of synthetic 1 with natural brevenal, coupled with the postulated biosynthetic pathway for marine polyether natural products, suggested that the natural product was most likely represented by 2, the C26 epimer of the proposed structure 1. The revised structure was finally validated by completing the first total synthesis of (−)-2, which also unambiguously established the absolute configuration of the natural product.

Introduction

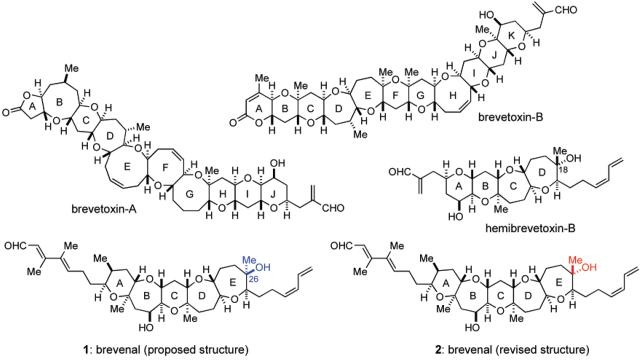

Marine polycyclic ether natural products continue to fascinate chemists and biologists because of their unique and highly complex molecular architecture coupled with diverse and extremely potent biological activities.1,2 Among these, brevetoxin-B, produced by the Florida red tide dinoflagellate, Karenia brevis (formerly known as Gymnodinium breve and Ptychodiscus brevis), is the first member of this class of natural products to be structurally elucidated by spectroscopic and X-ray crystallographic analysis by Nakanishi and co-workers in 1981 (Figure 1).3 Ever since, a number of congeners, including brevetoxin-A,4 have been isolated and structurally characterized. These toxic metabolites are known to exhibit their potent neurotoxicity by binding with a receptor site 5 on voltage-sensitive sodium channels (VSSC) in excitable membranes, thereby causing the channels to open at normal resting potentials with an increase in mean channel open time and inhibiting channel inactivation.5 Blooms of K. brevis have been associated with massive fish kills and marine mammal poisoning, and they are thought to be responsible for adverse human health effects, such as respiratory irritation and airway constriction observed in beach-goers during a red tide. In addition, the consumption of shellfish contaminated with brevetoxins results in neurotoxic shellfish poisoning (NSP) in humans, which is characterized by sensory abnormalities, cranial nerve dysfunction, gastrointestinal symptoms, and sometimes respiratory failure.6 Hemibrevetoxin-B, another polycyclic ether compound, was isolated by Prasad and Shimizu from the same organism, and the molecular size is about one-half of that of brevetoxins.7 Hemibrevetoxin-B was reported to cause the same characteristic rounding of cultured mouse neuroblastoma cells as brevetoxins and show cytotoxicity at a concentration of 5 μM.

Figure 1.

Structures of brevetoxin-A, brevetoxin-B, hemibrevetoxin-B, and brevenal (proposed structure 1 and revised structure 2).

Brevenal, isolated recently by Baden, Bourdelais, and co-workers from the laboratory cultures of K. brevis along with brevetoxins, represents the newest member of polycyclic ethers.8 The gross structure of brevenal, including the relative stereochemistry, was disclosed in 2004 as structure 1 on the basis of extensive 2D NMR studies; however, the absolute stereochemistry remained to be established. Although the size of the molecule is relatively compact compared with brevetoxins, the pentacyclic polyether core arranged with four methyl and two hydroxy groups and, especially, the characteristic heavily substituted left-hand (E,E)-dienal side chain make it a synthetically challenging target molecule. In addition, the biological profile of brevenal is particularly unique and intriguing in that it competitively displaces tritiated dihydrobrevetoxin-B ([3H]-PbTx-3) from VSSC in rat brain synaptosomes in a dose-dependent manner and antagonizes the toxic effects of brevetoxins in vivo.8,9 More importantly, picomolar concentrations of brevenal increased tracheal mucus velocity to the same degree as that observed with millimolar concentrations of a sodium channel blocker, amiloride, which is used in the treatment of cystic fibrosis.10 Thus, brevenal represents a potential lead for the development of novel therapeutic agents for the treatment of mucociliary dysfunction associated with cystic fibrosis and other lung disorders.

The remarkable structural and biological aspects of this natural product led us to embark on its total synthesis. We have recently reported the first total synthesis of structure 1 originally proposed for brevenal by means of our developed Suzuki–Miyaura coupling-based convergent strategy.11 However, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra for the synthetic material were not identical to those reported for the natural product, suggesting that it is necessary to revise the initial structural assignment. Herein, we describe the details of our total synthesis of the proposed brevenal structure 1 and non-identity to the natural product. On the basis of the NMR distinctions, a revised structure 2, the C26-epimer of 1, was proposed and finally confirmed by the total synthesis of (−)-2, which has also led to unambiguous determination of the absolute configuration of the natural product.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis Plan

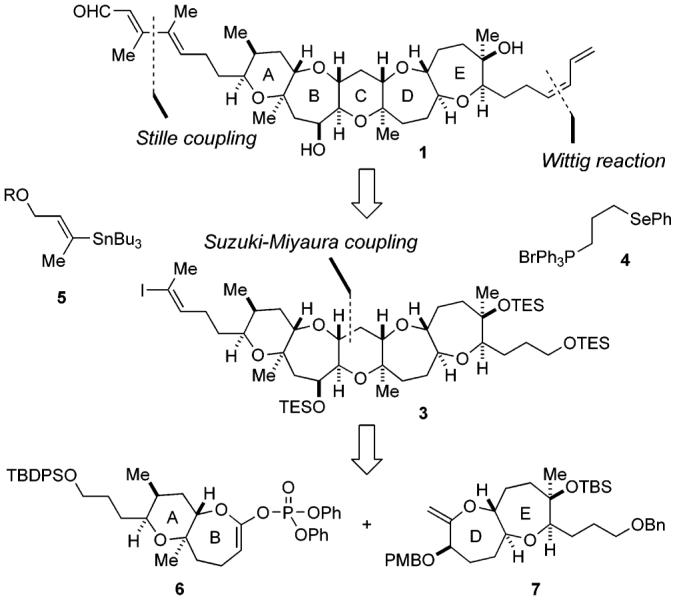

Our total synthesis of structure 1 originally proposed for brevenal was based on a retrosynthetic analysis as depicted in Scheme 1. The characteristic unsaturated side chains at both ends of the molecule were to be constructed at a late stage of the total synthesis. The right-hand (Z)-diene is the same as that found in the hemibrevetoxin-B structure, and thus this could be prepared by the precedented procedure, namely, selenyl–Wittig reaction using the ylide generated from phosphonium salt 4 followed by syn elimination of the selenoxide.12 On the other hand, the left-hand side chain that contains a multi-substituted (E,E)-dienal moiety was planned to be constructed in a stereoselective manner by the Stille coupling of (E)-vinyl iodide 3 and (E)-vinyl stannane 5.13 In turn, the pentacyclic polyether core in 3 was envisaged to be available from the AB ring enol phosphate 6 and the DE ring exocyclic enol ether 7 by means of our Suzuki–Miyaura coupling-based chemistry.14-16

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic Analysis

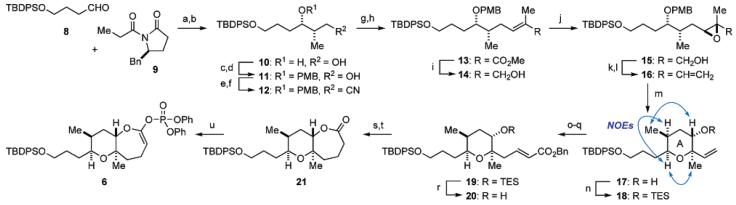

Synthesis of the AB Ring Fragment 6

The synthesis of the AB ring fragment 6 started with Evans aldol reaction of aldehyde 8 and oxazolidinone 9, which provided the desired syn-aldol adduct (Scheme 2).17 The chiral auxiliary was reductively removed with NaBH418 to provide 1,3-diol 10 as a single stereoisomer in 90% overall yield. The resultant diol 10 was protected as the p-methoxybenzylidene acetal, which was then reduced with DIBALH in a regioselective manner to afford primary alcohol 11 in 94% yield for the two steps.19 Mesylation of 11 followed by displacement with sodium cyanide gave nitrile 12 in 96% yield (two steps). DIBALH reduction of the nitrile and subsequent Wittig reaction of the resulting aldehyde provided α,β-unsaturated ester 13 in 87% yield for the two steps. After reduction with DIBALH, Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation of the resultant allylic alcohol 14 under the stoichiometric conditions gave epoxy alcohol 15 in 88% yield. In contrast, under the catalytic conditions, the yield of 15 was moderate (ca. 50%) and several unidentified byproducts were formed. Oxidation of 15 followed by Wittig olefination provided vinyl epoxide 16 in 90% yield for the two steps. Upon exposure of 16 to DDQ (CH2Cl2/H2O (20:1), room temperature), deprotection of the PMB group with concomitant 6-endo cyclization took place20 to furnish the A ring pyran 17, which was then protected as the TES ether 18 (89% yield for the two steps). The relative stereochemistry of 17 was established by NOE experiments as shown. Hydroboration of 18 with disiamylborane gave an alcohol (92% yield), which was then subjected to oxidation and Wittig reaction to afford α,β-unsaturated ester 19 in 86% yield for the two steps. Removal of the TES group under mild acidic conditions provided alcohol 20. Hydrogenation of 20 with concomitant hydrogenolysis of the benzyl ester, followed by Yamaguchi lactonization,21 generated seven-membered lactone 21 (88% overall yield), which was then transformed to the requisite AB ring enol phosphate 6 by the usual method.22

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of the AB Ring Fragmenta

a Reagents and conditions: (a)n-Bu2BOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, −78 → 0 °C; (b) NaBH4, THF/H2O, rt, 90% (two steps); (c) p-MeOC6H4CH(OMe)2, PPTS, CH2Cl2, rt; (d) DIBALH, CH2Cl2, −78 → −40 °C, 94% (two steps); (e) MsCl, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (f) NaCN, DMSO, 60 °C, 96% (two steps); (g) DIBALH, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, 90%; (h) Ph3P=C(Me)CO2Et, toluene, 100 °C, 97%; (i) DIBALH, CH2Cl2, −78 °C, quant.; (j) (+)-DET, Ti(Oi-Pr)4, t-BuOOH, CH2Cl2, −40 °C, 88%; (k) SO3•pyridine, Et3N, DMSO/CH2Cl2 (1:1), 0 °C; (l) Ph3P+CH3Br−, NaHMDS, THF, 0 °C, 90% (two steps); (m) DDQ, CH2Cl2/H2O (20:1), rt; (n) TESOTf, 2,6-lutidine, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 89% (two steps); (o) (Sia)2BH, THF, 0 °C; then aq NaHCO3, 30% H2O2, rt, 92%; (p) SO3•pyridine, Et3N, DMSO/CH2Cl2 (1:1), 0 °C; (q) Ph3P=CHCO2Bn, toluene, 60 °C, 86% (two steps); (r) 1 M HCl, THF, rt, 95%; (s) H2, 20% Pd(OH)2/C, THF/MeOH (2:1), rt, 90%; (t) 2,4,6-Cl3C6H2COCl, Et3N, THF, 0 °C → rt; then DMAP, toluene, 110 °C, 98%; (u) KHMDS, (PhO)2P(O)Cl, HMPA, THF, −78 °C, 96%.

Synthesis of the DE Ring Fragment 7

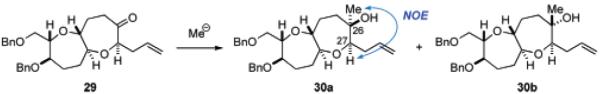

For the synthesis of the DE ring fragment 7, the known seven-membered ether 22,23 corresponding to the D ring, was selected as a starting material (Scheme 3). Benzylation of 22 followed by ozonolysis and reductive workup with NaBH4 gave alcohol 23 in 96% yield for the two steps. The primary alcohol of 23 was protected as the benzyl ether and the benzylidene acetal was removed under acidic conditions to afford diol 24 in a quantitative yield for the two steps. Selective triflation of the primary alcohol followed by TBS protection of the residual secondary alcohol was carried out in one-pot following the method of Mori.24 The resulting primary triflate was immediately subjected to nucleophilic displacement with allylmagnesium bromide in the presence of CuBr25 to afford elongated olefin 25 in 85% overall yield. The terminal olefin of 25 was oxidatively cleaved (OsO4, 4-methylmorpholine N-oxide (NMO); then NaIO4) to give the corresponding aldehyde, which was treated with 1,3-propanedithiol in the presence of boron trifluoride etherate to provide alcohol 26 after deprotection of the silyl group (88% yield for the four steps). Hetero-Michael reaction of 26 with methyl propiolate and 4-methylmorpholine (NMM) followed by hydrolysis of the dithioacetal (MeI, NaHCO3, aq MeCN) afforded β-alkoxyacrylate 27 in 99% yield for the two steps. Exposure of 27 to SmI2 in the presence of methanol (THF, room temperature) effected reductive cyclization to form the seven-membered ether,26 and after acidic treatment, tricyclic lactone 28 was obtained in 84% yield for the two steps as a single stereoisomer. DIBALH reduction of the γ-lactone and Wittig reaction of the resulting hemiacetal, followed by oxidation of the derived secondary alcohol with tetra-n-propylammonium perruthenate (TPAP)/NMO,27 led to ketone 29 in 91% yield for the three steps. At this stage, the stereochemistry at the C27 position28 was confirmed by NOE experiment as shown.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of Ketone 29a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) KOt-Bu, BnBr, n-Bu4NI, THF, rt; (b) O3, CH2Cl2/MeOH (1:1), −78 °C; then NaBH4, 0 °C, 96% (two steps); (c) NaH, BnBr, THF/DMF (1:1), rt; (d) CSA, MeOH/CH2Cl2 (10:1), rt, quant. (two steps); (e) Tf2O, 2,6-lutidine, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; then TBSOTf, 0 °C; (f) allylMgBr, CuBr, Et2O, 0 °C, 85% (two steps); (g) OsO4, NMO, THF/H2O (7:1), rt; then NaIO4, rt; (h) HS(CH2)3SH, BF3·OEt2, CH2Cl2, −78 → 0 °C; (i) TBAF, THF, rt, 88% (three steps); (j) methyl propiolate, NMM, CH2Cl2, rt; (k) MeI, NaHCO3, MeCN/H2O (4:1), rt, 99% (two steps); (l) SmI2, MeOH, THF, rt; then p-TsOH·H2O, toluene, 80 °C, 84% (two steps); (m) DIBALH, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; (n) Ph3P+CH3Br−, NaHMDS, THF, 0 °C → rt, 94% (two steps); (o) TPAP, NMO, 4 Å molecular sieves, CH2Cl2, rt, 97%.

We next investigated stereoselective methylation of ketone 29 using several nucleophiles under various conditions, and the results are summarized in Table 1. Treatment of 29 with excess trimethylaluminum in CH2Cl2 produced an approximately 1.3:1 mixture of tertiary alcohols 30a and 30b along with recovered starting material 29 (entry 1). Exposure of 29 to excess methylmagnesium bromide in THF at −78 °C gave a mixture of 30a and 30b with slightly improved diastereoselectivity (ca. 2.5:1 dr), but a significant amount of ketone 29 was recovered (entry 2). Increasing the reaction temperature dramatically improved the conversion yield without affecting the diastereoselectivity. Thus, treatment of 29 with 1.5 equiv of methylmagnesium bromide in THF at −78 °C to room temperature provided 30a,b in 99% combined yield (ca. 2.3:1 dr, entry 3). The use of toluene as the solvent led to less favorable ratio (ca. 1:1.3 dr) of products (entry 4). Finally, it was found that addition of methyllithium (1.2 equiv) to 29 in THF at −78 °C followed by gradual warming to room temperature furnished a 10:1 mixture of 30a and 30b in 97% yield (entry 5). The undesired minor isomer 30b could be easily separated by flash chromatography. Stereochemistry at the C26 tertiary stereocenter of 30a was unequivocally established by NOE between 26-Me and 27-H. The corresponding NOE was not observed for the isomer 30b.

Table 1.

Stereoselective Methylation of Ketone 29

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | reagents and conditions | 30a:30b | % yielda |

| 1 | Me3Al (10 equiv), CH2Cl2, −78 °C → rt | 1.3:1 | 78 (20)b |

| 2 | MeMgBr (10 equiv), THF, −78 °C | 2.5:1 | 36 (52)b |

| 3 | MeMgBr (1.5 equiv), THF, −78 °C → rt | 2.3:1 | 99 |

| 4 | MeMgBr (1.5 equiv), toluene, −78 °C → rt | 1:1.3 | quant. |

| 5 | MeLi (1.2 equiv), THF, −78 °C → rt | 10:1 | 97 |

Isolated yields.

Yields in parentheses are recovered 29.

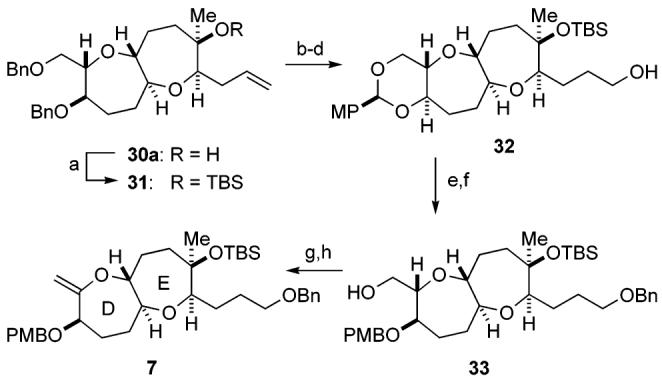

Conversion of tertiary alcohol 30a to the DE ring fragment 7 was carried out as illustrated in Scheme 4. Thus, 30a was protected with TBSOTf and triethylamine to give the TBS ether 31. Hydroboration of the terminal olefin and removal of the benzyl groups under hydrogenolysis, followed by p-methoxy-benzylidene acetal formation, led to primary alcohol 32 in 80% yield for the three steps. Benzylation followed by reductive cleavage of the acetal with DIBALH provided alcohol 33 (85% yield, two steps). Finally, iodination and subsequent base treatment furnished the DE ring exo-olefin fragment 7 in 99% yield for the two steps.

Scheme 4.

Synthesis of the DE Ring Fragment 7a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) TBSOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt, quant.; (b) 9-BBN, THF, rt; then aq NaHCO3, 30% H2O2, rt; (c) H2, 20% Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH, rt; (d) p-MeOC6H4CH(OMe)2, PPTS, CH2Cl2, rt, 70% (three steps); (e) KOt-Bu, BnBr, n-Bu4NI, THF, rt; (f) DIBALH, CH2Cl2, −78 → 0 °C, 87% (two steps); (g) I2, PPh3, imidazole, benzene, rt; (h) KOt-Bu, THF, 0 °C, 92% (two steps).

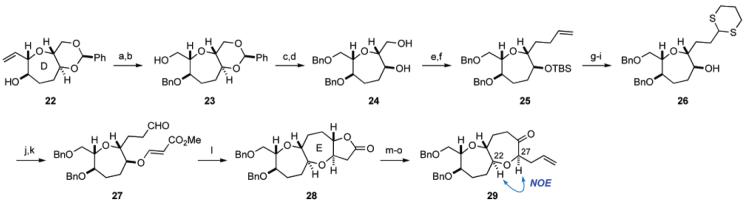

Construction of the Pentacyclic Polyether Core

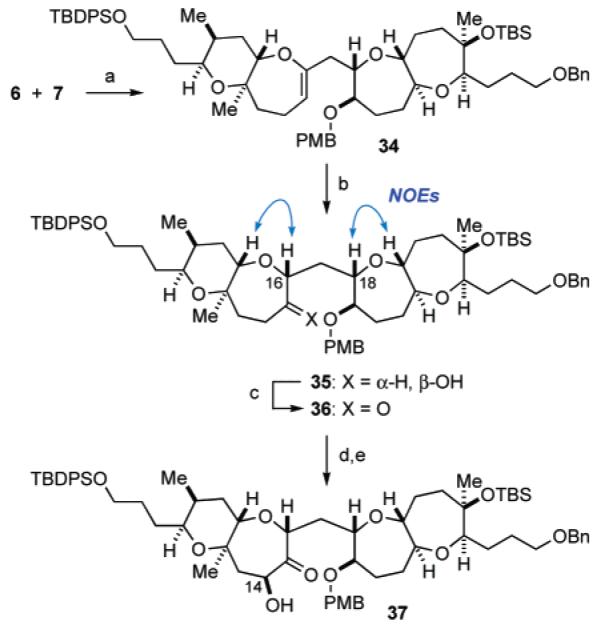

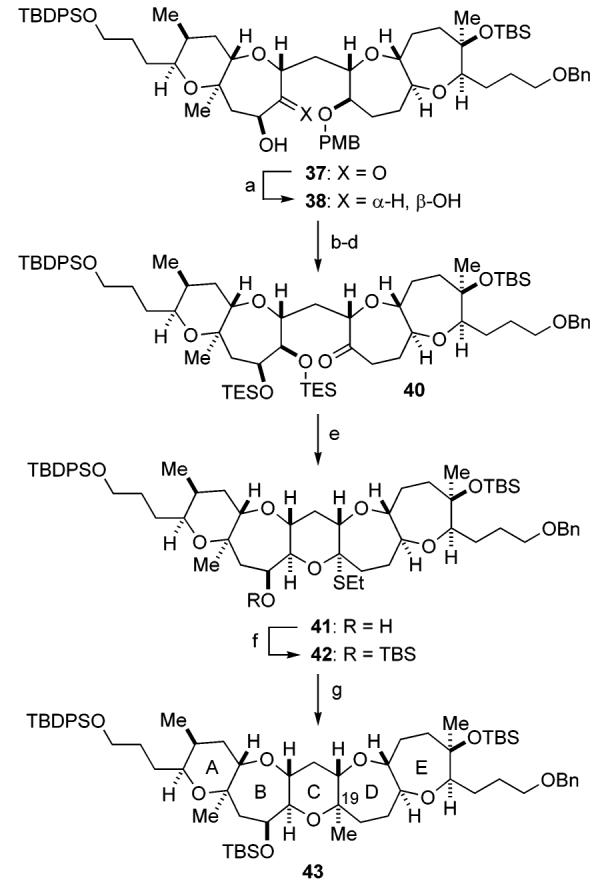

With the requisite fragments in hand, we set out to assemble the pentacyclic polyether core as summarized in Schemes 5 and 6. Hydroboration of the DE ring exocyclic enol ether 7 with 9-BBN produced the corresponding alkylborane, which was in situ reacted with the AB ring enol phosphate 6 in the presence of aqueous Cs2CO3 and Pd(PPh3)4 in DMF at 50 °C to furnish the desired coupling product 34 as a single stereoisomer (Scheme 5). The endocyclic enol ether within 34 was then hydroborated with BH3·SMe2 to give alcohol 35 (84% overall yield from 7), which was oxidized with TPAP/NMO to afford ketone 36 in 98% yield. At this stage, the newly generated stereocenters at C16 and C18 were unambiguously confirmed by NOE experiments as shown. Subsequent stereoselective introduction of the C14 hydroxy group was successfully achieved by the previously described method.16c,d,29 Thus, treatment of ketone 36 with LiHMDS in the presence of TMSCl and triethylamine gave the corresponding silyl enol ether, which was then treated with OsO4/NMO to provide α-hydroxy ketone 37 as the sole product (87% for the two steps).

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of α-Hydroxy Ketone 37a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) 7, 9-BBN, THF, rt; aq Cs2CO3, 6, Pd(PPh3)4, DMF, 50 °C; (b) BH3·SMe2, THF, rt; then aq NaHCO3, 30% H2O2, rt, 84% (two steps); (c) TPAP, NMO, 4 Å molecular sieves, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 98%; (d) LiHMDS, TMSCl, Et3N, THF, −78 °C; (e) OsO4, NMO, THF/H2O (4:1), rt, 87% (two steps).

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of the Pentacyclic Polyether Corea

a Reagents and conditions: (a) DIBALH, THF, −78 °C, 76% (+diastereomer, 7%; recovered 37, 12%); (b) TESOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (c) DDQ, CH2Cl2/pH 7 phosphate buffer, rt; (d) TPAP, NMO, 4 Å molecular sieves, CH2Cl2, rt, 88% (three steps); (e) EtSH, Zn(OTf)2, THF, rt, 79%; (f) TBSOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 97%; (g) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; then Me3Al (excess), −78 → 0 °C, 92%.

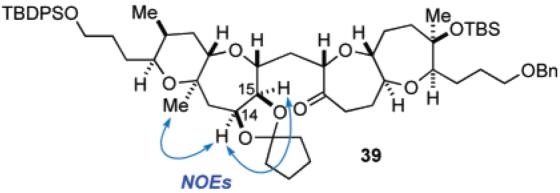

Subsequent reduction of hydroxy ketone 37 with DIBALH in THF at −78 °C provided an approximately 10:1 mixture of cis-diol 38 and its trans-isomer in 83% combined yield, along with a 12% yield of recovered 37 (Scheme 6). The desired isomer 38 could be easily separated by flash chromatography. The newly generated stereocenters at the C14 and C15 positions were established by derivatization to the cyclopentylidene acetal 39 and NOE experiments (Figure 2). It is noteworthy that DIBALH reduction of the TES-protected derivative of 37 led exclusively to the corresponding α-alcohol, suggesting the importance of the free hydroxy group. The outcome of this stereoselective reduction of 37 can be explained as follows. Initially, the C14 hydroxy group reacts with DIBALH to form the corresponding aluminum alkoxide, which coordinates to the adjacent C15 carbonyl group to form a five-membered chelate structure, thereby blocking the β-side of the molecule and forcing the second equivalent of the reductant to approach from the less hindered α-side.

Figure 2.

Stereochemical confirmation of cis-diol 38.

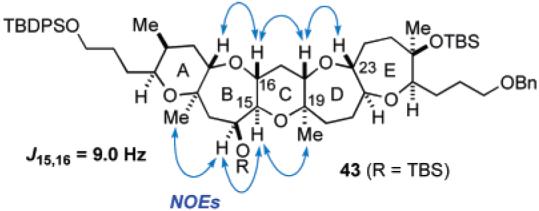

After protection of 38 as the bis-TES ether, oxidative removal of the PMB group with DDQ, followed by oxidation of the resulting secondary alcohol with TPAP/NMO, led to ketone 40 in 88% yield for the three steps. To complete the C ring with an angular methyl group at C19, ketone 40 was treated with ethanethiol in the presence of zinc triflate in THF at room temperature to effect deprotection of the TES groups with concomitant formation of a mixed thioacetal to generate 41 in 79% yield.30 After protection of the secondary hydroxy group as the TBS ether (97%), introduction of the C19 axial methyl group was next investigated. Although we initially attempted oxidation of the sulfur within 42 with mCPBA to the corresponding sulfone under various conditions, it became evident that the mixed sulfonyl acetal derived from 42 was so prone to undergo hydrolysis that we could only obtain the corresponding hemiacetal derivative. Therefore, we decided to avoid isolation of the unstable intermediate and carry out the oxidation–methylation in a one-pot manner.30a Thus, after oxidation of 42 with mCPBA at −78 °C, excess amount of trimethylaluminum (3 × 4 equiv + 2 equiv) was added and the resulting mixture was allowed to warm to 0 °C. Gratifyingly, this one-pot procedure ensured the desired pentacyclic polyether core 43 in 92% yield as a single isomer. The addition of trimethylaluminum in several portions was crucial for the success of the present process. The newly generated stereocenters were unambiguously established on the basis of NOE studies and 3JH,H data (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Stereochemical confirmation of pentacyclic polyether 43.

Model Experiments for the Synthesis of the Multi-Substituted (E,E)-Diene Side Chain

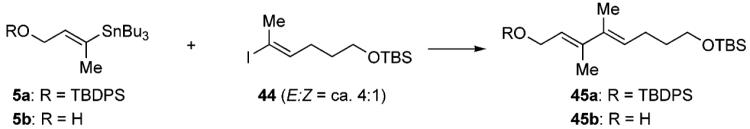

Having constructed the pentacyclic polyether skeleton, we next turned our attention to construction of the left-hand side chain. The multi-substituted (E,E)-dienal side chain is one of the characteristic structural features of brevenal. Although a survey of the literature suggested the difficulty of constructing such a heavily substituted diene system by means of palladium(0)-catalyzed cross-coupling reactions,13 we planned to utilize Stille coupling for connecting the C3–C4 bond. We first set out on model experiments in order to explore optimal conditions. (E)-Vinyl stannane 5 and (E)-vinyl iodide 44 (E:Z = ca. 4:1) were chosen as model substrates (Table 2). Stille coupling of 5a and 44 under the conventional conditions led to only a trace amount of the desired diene 45a, and significant amounts of the starting materials were recovered (entry 1). We assumed that this disappointing result was attributable to the low reactivity of 5a and 44 arising from steric hindrance. We reasoned that use of a soft ligand such as (2-furyl)3P or Ph3As, which accelerates the transmetallation step of the catalytic cycle of Stille coupling,31 and copper(I) salt as a co-catalyst, which promotes transmetallation of vinyl stannane 5 to a more reactive copper species,32 would be favorable in the present case. In the event, under the influence of the Pd2(dba)3/(2-furyl)3P/CuI or Pd2(dba)3/Ph3As/CuI catalyst system, Stille coupling of a sterically less encumbered vinyl stannane 5b and 44 proved to be very effective, giving diene 45b in acceptable yields (entries 2 and 3). However, increasing the reaction temperature to 60 °C caused significant isomerization of the diene configuration (entries 4 and 5). The structure of the isomerized byproduct, (E,Z)-diene 46, was confirmed by NOE experiments. Gratifyingly, it was found that the use of copper(I) thiophene-2-carboxylate (CuTC)33 instead of CuI realized further improvement of the yield of 45b (84% yield, entry 6). When the TBDPS-protected 5a was again used as a coupling partner, homocoupling product 47 was formed as a byproduct and hence the yield of the desired 45a was sligtly lowered (entries 7 and 8).

Table 2.

Stille Coupling of Vinyl Stannane 5 and Vinyl Iodide 44

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | vinyl stannane | reagents and conditions | % yield | (E,E):(E,Z) |

| 1 | 5a | PdCl2(MeCN)2, DMF, rt → 45 °C | trace | nda |

| 2b | 5b | Pd2(dba)3, (2-furyl)3P, CuI, DMSO/THF, rt | 57 | ca. 3.5:1 |

| 3b | 5b | Pd2(dba)3, Ph3As, CuI, DMSO/THF, rt | 54 | ca. 5:1 |

| 4b | 5b | Pd2(dba)3, (2-furyl)3P, CuI, DMSO/THF, 60 °C | 48 | 1:1 |

| 5b | 5b | Pd2(dba)3, Ph3As, CuI, DMSO/THF, 60 °C | 66 | 1:1 |

| 6b | 5b | Pd2(dba)3, Ph3As, CuTC, DMSO/THF, rt | 84 | ca. 10:1 |

| 7c | 5a | Pd2(dba)3, Ph3As, CuI, DMSO/THF, rt | 40 | 1:0 |

| 8c | 5a | Pd2(dba)3, Ph3As, CuTC, DMSO/THF, rt | 69 | 1:0 |

nd = not determined.

Isolated as a mixture of (E,E)- and (E,Z)-isomers. Ratio was estimated by 1H NMR (600 MHz).

Isolated as an inseparable mixture of 45a and homocoupling product 47. Yield was estimated based on 1H NMR analysis (600 MHz) of a purified mixture of 45a and 47.

![]()

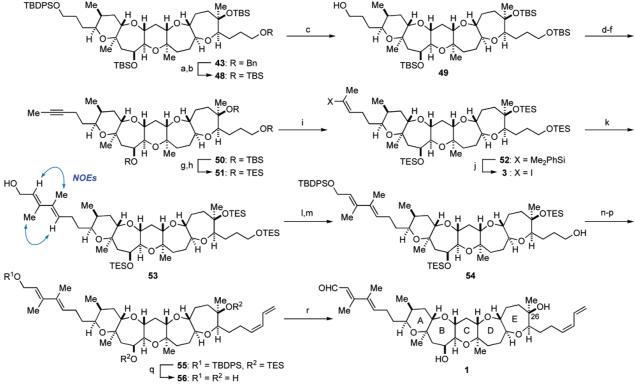

Total Synthesis of the Proposed Structure of Brevenal

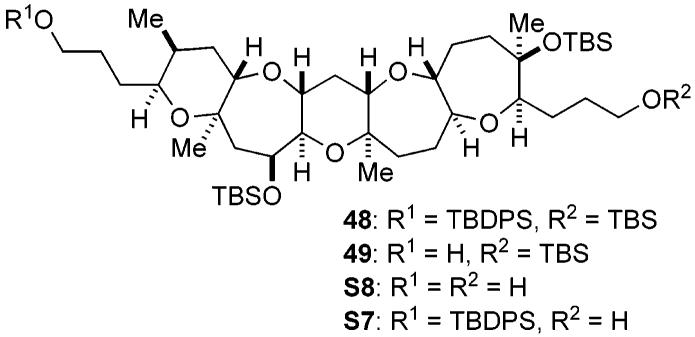

Having secured the reliable reaction conditions for constructing the left-hand side chain, the final stage of the total synthesis of 1 was executed as shown in Scheme 7. Reductive removal of the benzyl group from 43 with LiDBB34 was followed by reprotection as the TBS group to give silyl ether 48. Selective removal of the primary TBDPS group from 48 in the presence of the three TBS groups was successfully carried out according to the procedure of Nakata and co-workers,35 leading to primary alcohol 49 in 73% yield after three recycles.36 Oxidation of 49 with Dess–Martin periodinane37 followed by treatment of the resulting aldehyde with the Ohira–Bestmann reagent (K2CO3, MeOH)38 produced an alkyne, which was then methylated with n-butyllithium/methyl iodide to provide alkyne 50 in excellent overall yield. At this stage, the robust TBS protecting groups were replaced with the easily removable TES ethers. Thus, alkyne 50 was treated with HF•pyridine, and the resulting triol was reprotected with TESOTf and triethylamine to give tris-TES ether 51. Regioselective silylcupration of 51 with (Me2PhSi)2Cu(CN)Li239 delivered the desired vinylsilane 52 in an approximately 9:1 regioselectivity. The regiochemistry of 52 was confirmed by the characteristic pattern of the olefinic proton (dd, J = 7.0, 7.0 Hz). Conversion of 52 to vinyl iodide 3, required for the projected Stille coupling, was performed on exposure to N-iodosuccinimide (NIS) in MeCN/THF (4:1) at room temperature.40 Under these reaction conditions, isomerization of the olefin stereochemistry partially occurred and ca. 6:1 mixture of (E)-vinyl iodide 3 and its (Z)-isomer, along with small amounts of regioisomers, were produced in 99% combined yield from 51. The (E)-geometry of 3 was tentatively assigned because it is well-known that the iododesilylation generally proceeds with retention of configuration,40 and this was later confirmed by characterization of the cross-coupled product 53 (vide infra). Without separation of these isomers, the crucial Stille coupling was carried out under the established conditions. Thus, cross-coupling of 3 with vinyl stannane 5b in the presence of the Pd2(dba)3/Ph3As/CuTC catalyst system in THF/DMSO (1:1) at room temperature proceeded smoothly to furnish (E,E)-diene 53 in 63% yield as a single stereoisomer, after purification by flash chromatography.41 The stereochemistry of the diene system was unequivocally established by NOE experiments as shown.

Scheme 7.

Total Synthesis of the Proposed Structure 1 for Brevenala

a Reagents and conditions: (a) LiDBB, THF, −78 °C, 99%; (b) TBSOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 98%; (c) TBAF, AcOH, THF, rt, 78% after three recycles; (d) Dess-Martin periodinane, CH2Cl2, rt; (e) Bestmann reagent, K2CO3, MeOH, rt; (f) n-BuLi, THF/HMPA (10:1), −78 °C; then MeI, rt, 99% (three steps); (g) HF•pyridine, THF, rt, 96%; (h) TESOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 99%; (i) (Me2PhSi)2Cu(CN)Li2, THF, −78 → 0 °C, regioselectivity = ca. 9:1; (j) NIS, MeCN/THF (3:1), rt, 99% (two steps), E:Z = 6:1; (k) 5b, Pd2(dba)3, Ph3As, CuTC, DMSO/THF (1:1), rt, 63%; (l) TBDPSCl, imidazole, DMF, 0 °C, 99%; (m) PPTS, CH2Cl2/MeOH (4:1), 0 °C, 75%; (n) SO3•pyridine, Et3N, CH2Cl2/DMSO (3:1), 0 °C; (o) 4, n-BuLi, HMPA, THF, −78 °C → rt, 97% (two steps); (p) 30% H2O2, NaHCO3, THF, rt, 77%; (q) TAS-F, THF/DMF (1:1), rt, 79%; (r) MnO2, CH2Cl2, rt, quant.

After protection of the allylic alcohol of 53 as the TBDPS ether, the primary TES ether was selectively removed with PPTS to give alcohol 54 in 74% yield for the two steps. Introduction of the right-hand (Z)-diene side chain was performed without incident according to the procedure of Nicolaou et al.12 Thus, oxidation of 54 with SO3•pyridine/DMSO followed by Wittig olefination using the ylide, derived from phosphonium salt 4, and subsequent hydrogen peroxide treatment led to conjugated (Z)-diene 55 in 75% overall yield from 54. Global deprotection of the silyl protecting groups from 55 by the action of TAS-F42 provided triol 56 in 79% yield. Finally, chemoselective oxidation of the C1 alcohol by MnO2 completed the synthesis of the proposed structure 1 for brevenal in a quantitative yield.

Revised Structure of Brevenal

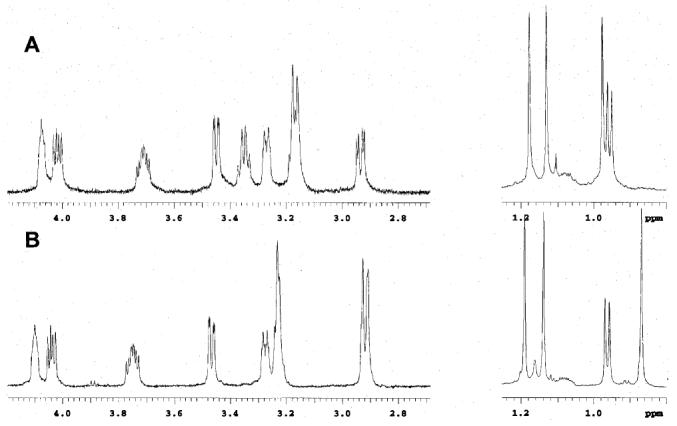

Unfortunately, however, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra of synthetic 1 were not identical with those of the authentic sample, suggesting that revision of the originally proposed structure of brevenal is necessary (Figure 4). For detailed comparison with the natural product, the 1H and 13C NMR data of synthetic 1 were carefully assigned on the basis of extensive 2D NMR experiments, and the results are summarized in Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 5. The 1H and 13C NMR chemical shifts in the left-hand region of synthetic 1 matched very closely those reported for the natural brevenal. In contrast, there were subtly distinct discrepancies of the chemical shifts in the DE ring region. Particularly, the observed chemical shifts around the C26 tertiary alcohol of 1 significantly deviated from those for the natural product, suggesting that an error(s) may exist somewhere around the E ring. COSY, HSQC, and HMBC correlations of the synthetic sample completely reproduced those of the authentic sample. However, a series of intense cross-peaks were observed between 26-Me/27-H and 26-Me/28-H2 in the NOESY spectrum of synthetic 1 (Figure 5), whereas no such NOESY correlations have been reported for naturally occurring brevenal.8b These NMR variations prompted us to propose the stereochemical inversion of the C26 tertiary alcohol within 1, giving the revised structure 2 for brevenal.

Figure 4.

Partial 1H NMR spectra (600 MHz, C6D6) of the natural brevenal (panel A) and synthetic 1 (panel B).

Table 3.

1H NMR Chemical Shifts of Natural Product and Synthetic 1a

| no. | natural brevenalb |

synthetic 1 | Δδ | no. | natural brevenalb |

synthetic 1 | Δδ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 10.09 | 10.09 | 0.00 | 21 | 1.77 | 1.74 | 0.03 |

| 2 | 6.14 | 6.15 | −0.01 | 2.16 | 2.13 | 0.03 | |

| 3 | – | – | – | 22 | 3.35 | 3.23 | 0.12 |

| 4 | – | – | – | 23 | 3.17 | 3.22 | −0.05 |

| 5 | 5.81 | 5.81 | 0.00 | 24 | 1.77 | 1.50 | 0.27 |

| 6 | 2.01 | 2.01 | 0.00 | 1.90 | 1.92 | −0.02 | |

| 2.13 | 2.14 | −0.01 | 25 | 1.52 | 1.52 | 0.00 | |

| 7 | 1.09 | 1.08 | 0.01 | 1.54 | 1.69 | −0.15 | |

| 1.47 | 1.49 | −0.02 | 26 | – | – | – | |

| 8 | 3.28 | 3.28 | 0.00 | 27 | 3.16 | 2.92 | 0.24 |

| 9 | 1.46 | 1.44 | 0.02 | 28 | 1.44 | 1.39 | 0.05 |

| 10 | 1.75 | 1.75 | 0.00 | 1.57 | 1.71 | −0.14 | |

| 1.75 | 1.75 | 0.00 | 29 | 2.35 | 2.31 | 0.04 | |

| 11 | 4.00 | 4.04 | −0.04 | 2.35 | 2.31 | 0.04 | |

| 12 | – | – | – | 30 | 5.45 | 5.39 | 0.06 |

| 13 | 2.23 | 2.23 | 0.00 | 31 | 6.07 | 6.10 | −0.03 |

| 2.32 | 2.35 | −0.03 | 32 | 6.77 | 6.78 | −0.01 | |

| 14 | 4.08 | 4.10 | −0.02 | 33 | 5.05 | 5.08 | −0.03 |

| 15 | 3.45 | 3.47 | −0.02 | 5.16 | 5.18 | −0.02 | |

| 16 | 3.71 | 3.75 | −0.04 | 3-Me | 1.80 | 1.78 | 0.02 |

| 17 | 1.85 | 1.86 | −0.01 | 4-Me | 1.55 | 1.55 | 0.00 |

| 2.24 | 2.27 | −0.03 | 9-Me | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.01 | |

| 18 | 2.94 | 2.92 | 0.02 | 12-Me | 1.18 | 1.19 | −0.01 |

| 19 | – | – | – | 19-Me | 1.13 | 1.14 | −0.01 |

| 20 | 1.68 | 1.69 | −0.01 | 26-Me | 0.98 | 0.87 | 0.11 |

| 1.77 | 1.69 | 0.08 |

C6HD5 was adjusted to 7.15 ppm.

Chemical shift values were adjusted because in the original report (ref 8b) internal residual benzene was referenced to 7.16 ppm.

Table 4.

13C NMR Chemical Shifts of Natural Product and Synthetic 1a

| no. | natural brevenalb |

synthetic 1 | Δδ | no. | natural brevenalb |

synthetic 1 | Δδ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 191.0 | 190.7 | 0.3 | 21 | 29.8 | 29.6 | 0.2 |

| 2 | 126.0 | 126.0 | 0.0 | 22 | 86.3 | 85.6 | 0.7 |

| 3 | 156.7 | 156.1 | 0.6 | 23 | 84.8 | 83.9 | 0.9 |

| 4 | 135.8 | 135.8 | 0.0 | 24 | 29.4 | 29.4 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 134.6 | 134.6 | 0.0 | 25 | 38.8 | 37.4 | 1.4 |

| 6 | 26.4 | 26.4 | 0.0 | 26 | 73.9 | 74.3 | −0.4 |

| 7 | 32.7 | 32.6 | 0.1 | 27 | 87.4 | 88.5 | −1.1 |

| 8 | 70.9 | 70.7 | 0.2 | 28 | 30.6 | 29.9 | 0.7 |

| 9 | 33.4 | 33.4 | 0.0 | 29 | 25.3 | 24.8 | 0.5 |

| 10 | 35.3 | 35.2 | 0.1 | 30 | 133.0 | 132.9 | 0.1 |

| 11 | 76.5 | 76.4 | 0.1 | 31 | 130.1 | 130.2 | −0.1 |

| 12 | 77.2 | 77.2 | 0.0 | 32 | 132.7 | 132.6 | 0.1 |

| 13 | 48.0 | 47.8 | 0.2 | 33 | 117.0 | 117.3 | −0.3 |

| 14 | 69.9 | 69.9 | 0.0 | 3-Me | 14.0 | 13.8 | 0.2 |

| 15 | 75.0 | 75.0 | 0.0 | 4-Me | 13.7 | 13.7 | 0.0 |

| 16 | 73.7 | 73.6 | 0.1 | 9-Me | 12.9 | 12.8 | 0.1 |

| 17 | 34.5 | 34.4 | 0.1 | 12-Me | 19.5 | 19.3 | 0.2 |

| 18 | 82.0 | 82.1 | −0.1 | 19-Me | 16.2 | 15.8 | 0.4 |

| 19 | 76.7 | 76.7 | 0.0 | 26-Me | 23.5 | 25.7 | −2.2 |

| 20 | 37.8 | 37.5 | 0.3 |

13C6D6 was adjusted to 128.0 ppm.

Chemical shift values were adjusted because in the original report (ref 8b) internal residual benzene was referenced to 128.4 ppm.

Figure 5.

Selected key NOE data for synthetic 1.

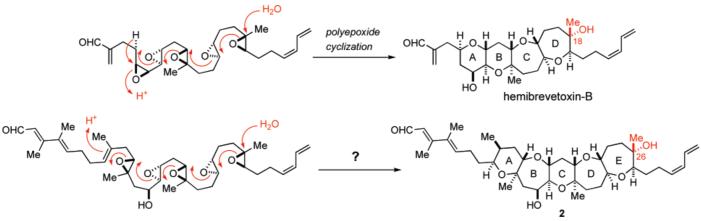

The revised structure 2 is also supported by the postulated biosynthetic pathway for ladder-shaped polycyclic ether marine natural products (i.e., a cascade of polyepoxide cyclization) proposed by Shimizu and Nakanishi, independently (Figure 6).7,43,44 The stereochemistry at C26 of brevenal would be epimeric to the proposed structure 1, provided that a similar biosynthetic route is applicable to brevenal (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed biosynthetic pathway for marine polycyclic ether natural products.

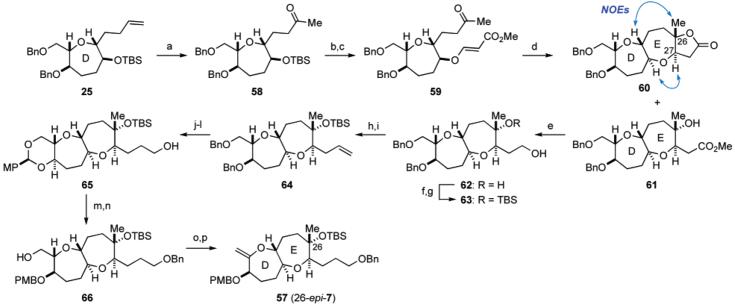

Total Synthesis of Revised Structure and the Absolute Configuration of Brevenal

To confirm our postulated idea, we turned to the synthesis of the C26 epimer 2 of the originally proposed structure 1. Starting with an intermediate 25 in the synthesis of 7 (see Scheme 3), the requisite DE ring fragment 57 (26-epi-7) was prepared as summarized in Scheme 8. Wacker–Tsuji reaction45 of the terminal olefin within 25 using the PdCl2/Cu(OAc)2 system46 provided methyl ketone 58 in 92% yield. Removal of the TBS group from 58 followed by incorporation of a β-alkoxyacrylate unit to the resulting secondary alcohol produced 59 in high overall yield. Reductive cyclization of 59 with SmI2 (MeOH/THF, room temperature) proceeded smoothly to form the seven-membered ether ring with the desired stereochemistry at C26, providing a mixture of γ-lactone 60 and hydroxy ester 61 in 57% and 37% yield, respectively.26 The C26 and C27 stereochemistries of 60 were confirmed by NOE experiments as shown. Each of these compounds was cleanly reduced with lithium aluminum hydride (THF, 0 °C) to yield the same diol 62 in high yield. After protection as the bis-TBS ether, selective cleavage of the primary TBS ether under acidic conditions provided alcohol 63 in 90% yield for the two steps. Oxidation with SO3•pyridine/DMSO followed by Wittig methylenation of the resulting aldehyde led to 64 (94% yield, two steps), which was subsequently transformed to the DE ring fragment 57 following a similar sequence described for the conversion of 31 to 7 (see, Scheme 4).

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of the 26-epi-DE Ring Fragment 57a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) Cu(OAc)2, PdCl2, O2, DMA/H2O (7:1), rt, 92%; (b) TBAF, THF, rt; (c) methyl propiolate, NMM, CH2Cl2, rt, 96% (two steps); (d) SmI2, MeOH, THF, rt, 57% for 60, 37% for 61; (e) LiAlH4, THF, 0 °C, quant. from 60, quant. from 61; (f) TBSOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, rt; (g) CSA, MeOH/CH2Cl2 (1:1), 0 °C, 90% (two steps); (h) SO3•pyridine, Et3N, DMSO/CH2Cl2 (1:1), 0 °C; (i) Ph3P+CH3Br−, NaHMDS, THF, 0 °C, 94% (two steps); (j) 9-BBN, THF, rt; then aq NaHCO3, 30% H2O2, rt; (k) H2, 20% Pd(OH)2/C, MeOH, rt; (l) p-MeOC6H4CH(OMe)2, PPTS, CH2Cl2, rt, 80% (three steps); (m) BnBr, KOt-Bu, n-Bu4NI, THF, rt; (n) DIBALH, CH2Cl2, −78 → 0 °C, 85% (two steps); (o) I2, PPh3, imidazole, benzene, rt; (p) KOt-Bu, THF, 0 °C, 98% (two steps).

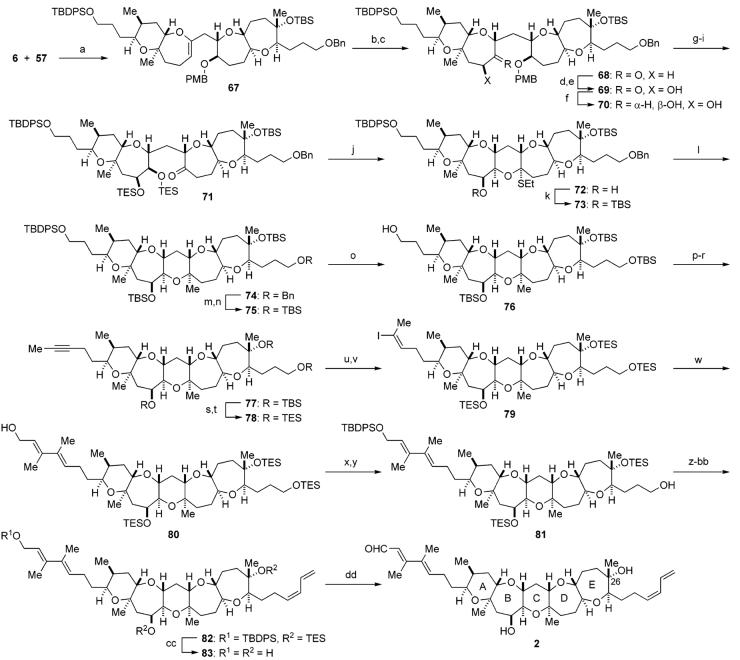

Convergent union of the DE ring fragment 57 and the AB ring enol phosphate 6 and subsequent elaboration of the resulting cross-coupled product 67 could be performed in much the same way as that used to reach 1 and proceeded in similar yields, thus completing the total synthesis of the revised structure 2 for brevenal (Scheme 9). To our delight, the 1H and 13C NMR spectra and high-resolution mass spectrum of synthetic 2 were completely identical with those of the natural product, culminating in a conclusion that the C26 epimer of the originally proposed structure is the correct structure of brevenal. In addition, synthetic brevenal 2 exhibited specific rotation, [α]D27 −33.5 (c 0.27, benzene), which matched the value [α]D27 −32.3 (c 0.27, benzene) for the natural product; thus, the absolute configuration of brevenal was unequivocally determined to be shown as structure 2.

Scheme 9.

Total Synthesis of the Revised Structure 2 for Brevenala

a Reagents and conditions: (a) 57, 9-BBN, THF, rt; then 3 M aq Cs2CO3, 6, Pd(PPh3)4, DMF, 50 °C; (b) BH3•SMe2, THF, rt; then aq NaHCO3, 30% H2O2, rt, 81% (two steps); (c) TPAP, NMO, 4 Å molecular sieves, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 98%; (d) LiHMDS, TMSCl, Et3N, THF, −78 °C; (e) OsO4, NMO, THF/H2O (4:1), rt, 83% (two steps); (f) DIBALH, THF, −78 °C, 85% (+ diastereomer, 8%; recovered 69, 3%); (g) TESOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C; (h) DDQ, CH2Cl2/pH 7 phosphate buffer (10:1), rt; (i) TPAP, NMO, 4 Å molecular sieves, CH2Cl2, rt, 88% (three steps); (j) EtSH, Zn(OTf)2, CH2Cl2, rt, 51%; (k) TBSOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C → rt, 86%; (l) mCPBA, CH2Cl2, −78 °C; then Me3Al (excess), −78 f 0 °C, 94%; (m) LiDBB, THF, −78 °C, 95%; (n) TBSOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 99%; (o) TBAF, AcOH, THF, rt, 79% after two recycles; (p) SO3•pyridine, Et3N, CH2Cl2/DMSO (3:1), 0 °C; (q) Bestmann reagent, K2CO3, MeOH, rt; (r) n-BuLi, THF/HMPA (10:1), −78 °C; then MeI, rt, 78% (three steps); (s) HF•pyridine, THF, rt, 97%; (t) TESOTf, Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 89%; (u) (Me2PhSi)2Cu(CN)Li2, THF, −78 → 0 °C, regioselectivity = ca. 8.5:1; (v) NIS, MeCN/THF (3:1), rt, 88% (two steps), E:Z = ca. 6:1; (w) 5b, Pd2(dba)3, Ph3As, CuTC, DMSO/THF (1:1), rt, 60%; (x) TBDPSCl, imidazole, DMF, 0 °C, 87%; (y) PPTS, CH2Cl2/MeOH (4:1), 0 °C, 70%; (z) SO3•pyridine, Et3N, CH2Cl2/DMSO (4:1), 0 °C; (aa) 4, n-BuLi, HMPA, THF, −78 °C → rt, 99% (two steps); (bb) 30% H2O2, NaHCO3, THF, rt, 78%; (cc) TAS-F, THF/DMF (1:1), rt, quant.; (dd) MnO2, CH2Cl2, rt, 76%.

Conclusion

We accomplished the first total synthesis of the proposed structure 1 of brevenal. The key features of our synthesis include a convergent assembly of the pentacyclic polyether skeleton by using the Suzuki–Miyaura coupling-based strategy and a stereoselective construction of the left-hand multi-substituted (E,E)-diene system by the CuTC-promoted modified Stille coupling. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of synthetic 1 did not match those for the natural product. Detailed NMR comparison of the synthetic material with the natural substance and the proposed biosynthesis of ladder-shaped polycyclic ether natural products led us to propose a revised structure 2, the C26-epimer of 1. In the event, the revised structure was validated through total synthesis, which also led to determination of the absolute configuration. This study demonstrates the important role of stereoselective total synthesis in structure determination of complex natural products.47 Moreover, the highly convergent nature of the present synthesis will allow divergent total synthesis of structural analogues for more detailed structure–activity relationship studies of this intriguing natural product. Further studies along this line are currently underway and will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Mr. Ryuichi Watanabe (Tohoku University) for NMR measurements, and Dr. Thomas Schuster and Dr. Sophie Michelliza (UNCW) for their technical expertise. This work was financially supported in part by the Naito Foundation and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan (MEXT) and the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). A postdoctoral fellowship for H.F. and a research fellowship for M.E. from JSPS are acknowledged.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Full experimental details and spectroscopic data for all new compounds, comparison of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for natural brevenal and synthetic 2, and copies of 1H and 13C NMR spectra for all new compounds (pdf). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.For reviews on marine polycyclic ethers, see:Yasumoto T, Murata M. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:1897–1909.Murata M, Yasumoto T. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2000:293–314. doi: 10.1039/a901979k.Yasumoto T. Chem. Rec. 2001;3:228–242. doi: 10.1002/tcr.1010.

- 2.For recent comprehensive reviews on total synthesis of polycyclic ethers, see: Nakata T. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4314–4347. doi: 10.1021/cr040627q.Inoue M. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:4379–4405. doi: 10.1021/cr0406108.

- 3.Lin Y-Y, Risk M, Ray SM, Van Engen D, Clardy J, Golik J, James JC, Nakanishi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:6773–6775. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shimizu Y, Chou H-N, Bando H, Van Duyne G, Clardy JC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:514–515. doi: 10.1021/ja00263a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Poli MA, Mende TJ, Baden DG. Mol. Pharmacol. 1986;30:129–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For recent reviews, see: Baden DG, Bourdelais AJ, Jacocks H, Michelliza S, Naar J. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005;113:621–625. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7499.Kirkpatrick B, Fleming LE, Squicciarini D, Backer LC, Clark R, Abraham W, Bentson J, Cheng YS, Johnson D, Pierce R, Zais J, Bossart GD, Baden DG. Harmful Algae. 2004;3:99–115. doi: 10.1016/j.hal.2003.08.005.

- 7.Prasad AVK, Shimizu Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6476–6477. [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Bourdelais AJ, Campbell S, Jacocks H, Naar J, Wright JLC, Carsi J, Baden DG. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2004;24:553–563. doi: 10.1023/B:CEMN.0000023629.81595.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bourdelais AJ, Jacocks HM, Wright JLC, Bigwarfe PM, Jr., Baden DG. J. Nat. Prod. 2005;68:2–6. doi: 10.1021/np049797o. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sayer A, Hu Q, Bourdelais AJ, Baden DG, Gilson JE. Arch. Toxicol. 2005;79:683–688. doi: 10.1007/s00204-005-0676-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Abraham WM, Bourdelais AJ, Sabater JR, Ahmed A, Lee TA, Serebriakov I, Baden DG. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2005;171:26–34. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200406-735OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For a preliminary communication, see: Fuwa H, Ebine M, Sasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:9648–9650. doi: 10.1021/ja062524q.

- 12.(a) Nicolaou KC, Reddy KR, Skokotas G, Sato F, Xiao X-Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:7935–7936. [Google Scholar]; (b) Nicolaou KC, Reddy KR, Skokotas G, Sato F, Xiao X-Y, Hwang C-K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993;115:3558–3575. [Google Scholar]

- 13.For recent reviews, see: Nicolaou KC, Bulger PG, Sarlah D. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:4442–4489. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500368.Espinet P, Echavarren AE. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2004;43:4704–4734. doi: 10.1002/anie.200300638.Mitchell TC. In: Metal-catalyzed Cross-coupling Reactions. 2nd ed. de Meijere A, Diederich F, editors. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim: 2004. pp. 125–162.Farina V, Krishnamurthy V, Scott WJ. Org. React. 1997;50:1–652.

- 14.For reviews on Suzuki-Miyaura coupling, see: Suzuki A, Miyaura N. Chem. Rev. 1995;95:2457–2483.Chemler SR, Trauner D, Danishefsky SJ. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2001;40:4544–4568. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20011217)40:24<4544::aid-anie4544>3.0.co;2-n.

- 15.(a) Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Inoue M, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:9027–9030. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sasaki M, Fuwa H, Ishikawa M, Tachibana K. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1075–1077. [Google Scholar]; (c) Sasaki M, Ishikawa M, Fuwa H, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1889–1911. [Google Scholar]; (d) Sasaki M, Fuwa H. Synlett. 2004:1851–1874. [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Fuwa H, Sasaki M, Satake M, Tachibana K. Org. Lett. 2002;4:2981–2984. doi: 10.1021/ol026394b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Fuwa H, Kainuma N, Tachibana K, Sasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:14983–14992. doi: 10.1021/ja028167a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Tsukano C, Sasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:14294–14295. doi: 10.1021/ja038547b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Tsukano C, Ebine M, Sasaki M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:4326–4335. doi: 10.1021/ja042686r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evans DA, Bartroli J, Shih TL. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1981;103:2127–2129. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prashad M, Har P, Kim H-Y, Repic O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:7067–7070. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Johansson R, Samuelsson B. J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. 1984:201–202. [Google Scholar]; (b) Johansson R, Samuelsson B. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1. 1984:2371–2374. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Uehara H, Oishi T, Inoue M, Shoji M, Nagumo Y, Kosaka M, Le Brazidec J-M, Hirama M. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:6493–6512. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yamaguchi M, Inanaga J, Hirata K, Sasaki H, Katsuki T. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 1979;52:1989–1993. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolaou KC, Shi G-Q, Gunzner JL, Gärtner P, Yang Z. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997;119:5467–5468. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kadota I, Ohno A, Matsukawa Y, Yamamoto Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:6373–6776. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mori Y, Yaegashi K, Furukawa H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:8158–8159. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotsuki H, Kadota I, Masamitsu O. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990;31:4609–4612. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Hori N, Matsukura H, Matsuo G, Nakata T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:2811–2814. [Google Scholar]; (b) Hori N, Matsukura H, Nakata T. Org. Lett. 1999;1:1099–1101. [Google Scholar]; (c) Matsuo G, Hori N, Nakata T. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:8859–8862. [Google Scholar]; (d) Hori N, Matsukura H, Matsuo G, Nakata T. Tetrahedron. 2002;58:1853–1864. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ley SV, Normann J, Griffith WP, Marsden SP. Synthesis. 1994:639–666. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The carbon numbering of all compounds in this paper corresponds to that of brevenal.

- 29.Sasaki M, Ebine M, Takagi H, Takakura H, Shida T, Satake M, Oshima Y, Igarashi T, Yasumoto T. Org. Lett. 2004;6:1501–1504. doi: 10.1021/ol049569l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Nicolaou KC, Prasad CVC, Hwang C-K, Duggan ME, Veale CA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:5321–5330. [Google Scholar]; (b) Fuwa H, Sasaki M, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000;41:8371–8375. [Google Scholar]; (c) Fuwa H, Sasaki M, Tachibana K. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:3019–3033. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Farina V, Krishnan B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991;113:9585–9595. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farina V, Kapadia S, Krishnan B, Wang C, Liebeskind LS. J. Org. Chem. 1994;59:5905–5911. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Allred GD, Liebeskind LS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996;118:2748–2749. [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Freeman PK, Hutchinson LL. J. Org. Chem. 1980;45:1924–1930. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ireland RE, Smith MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1988;110:854–860. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Higashibayashi S, Shinko K, Ishizu T, Hashimoto K, Shirahama H, Nakata M. Synlett. 2000:1306–1308. [Google Scholar]

-

36.The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature overnight (ca. 13 h). Since, at this point, ca. 50% of the starting material 48 remained unreacted and a small amount of diol S8 was observed by TLC analysis, the reaction was quenched. After separation of 48, 49, S8, and S7 by flash chromatography, recycling of the recovered 48 (three times) provided 49 (78%), S8 (8%) and S7 (12%).

- 37.Dess DB, Martin JC. J. Org. Chem. 1983;48:4155–4156. [Google Scholar]

- 38.(a) Ohira S. Synth. Commun. 1989;19:561–564. [Google Scholar]; (b) Müller S, Liepold B, Roth GJ, Bestmann HJ. Synlett. 1996:521–522. [Google Scholar]

- 39.(a) Fleming I, Newton TW, Roessler F. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans 1. 1981:2527–2532. [Google Scholar]; (b) Zakarian A, Batch A, Holton RA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:7822–7824. doi: 10.1021/ja029225v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stamos DP, Taylor AG, Kishi Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1996;37:8647–8650. [Google Scholar]

- 41.We initially attempted the Stille coupling of TBDPS-protected vinyl stannane 5a with vinyl iodide 3; however, the desired cross-coupled product was obtained in only poor yield (22%).

- 42.(a) Noyori R, Nishida I, Sakata J, Nishizawa M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:1223–1225. [Google Scholar]; (b) Sheidt KA, Chen H, Follows BC, Chemler SR, Coffey DS, Roush WR. J. Org. Chem. 1998;63:6436–6437. [Google Scholar]

- 43.(a) Nakanishi K. Toxicon. 1985;23:473–479. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(85)90031-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Shimizu Y. In: Natural Toxins: Animal, Plant and Microbial. Harris JB, editor. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1986. pp. 115–125. [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee MS, Repeta DJ, Nakanishi K. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:7855–7856. doi: 10.1021/ja00284a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Chou H-N, Shimizu Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:2184–2185. [Google Scholar]; Lee MS, Qin G, Nakanishi K, Zagorski MG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:6234–6241. [Google Scholar]; (e) Townsend CA, Basak A. Tetrahedron. 1991;47:2591–2602. [Google Scholar]; (f) Gallimore AR, Spencer JB. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2006;45:4406–4413. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.For recent reviews on biomimetic synthesis of polycyclic ethers, see: Fujiwara K, Murai A. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2004;77:2129–2146.Valentine JC, McDonald FE. Synlett. 2006:1816–1828.

- 45.For a review, see: Tsuji J. Synthesis. 1984:369–384.

- 46.Smith AB, III, Cho YS, Friestad GK. Tetrahedron Lett. 1998;39:8765–8768. [Google Scholar]

- 47.For recent reviews, see: Weinreb SM. Acc. Chem. Res. 2003;36:59–65. doi: 10.1021/ar0200403.Nicolaou KC, Snyder SA. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005;44:1012–1044. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460864.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.