Abstract

Although x-ray crystallography is the most widely used method for macromolecular structure determination, it does not provide dynamical information, and either experimental tricks or complementary experiments must be used to overcome the inherently static nature of crystallographic structures. Here we used specific x-ray damage during temperature-controlled crystallographic experiments at a third-generation synchrotron source to trigger and monitor (Shoot-and-Trap) structural changes putatively involved in an enzymatic reaction. In particular, a nonhydrolyzable substrate analogue of acetylcholinesterase, the “off-switch” at cholinergic synapses, was radiocleaved within the buried enzymatic active site. Subsequent product clearance, observed at 150 K but not at 100 K, indicated exit from the active site possibly via a “backdoor.” The simple strategy described here is, in principle, applicable to any enzyme whose structure in complex with a substrate analogue is available and, therefore, could serve as a standard procedure in kinetic crystallography studies.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, kinetic crystallography, structure–dynamics–function relationships, energy landscape, synchrotron radiation

Protein function depends critically on the synergy of structure and dynamics. Structural dynamics, stemming from the interconversion of conformational states in the complex energy landscape of a protein (1, 2), are not readily accessible to conventional x-ray crystallography. The advent of third-generation synchrotron sources, producing highly brilliant x-ray beams, has opened up exciting possibilities for studying macromolecular structural dynamics by using an ensemble of techniques known as kinetic crystallography (3). Although specific radiation damage in the course of data collection is often an issue at highly intense insertion-device synchrotron beamlines (4–7), it has been used for certain aspects of macromolecular x-ray structure determination, such as for phasing purposes (8), to structurally follow the catalytic pathway of redox enzymes (9), and for monitoring the dynamical behavior of crystalline proteins at cryogenic temperatures (10, 11). Amino acid residues directly involved in protein function, including those at the active sites of enzymes, are among the most radiation-sensitive entities (4–6, 10, 12–16). This observation has been linked to the strain of residue conformations within active sites that is released upon specific radiation damage (17). In this study, temperature-controlled x-ray cryo-crystallography was shown to result in radiolytic cleavage of a substrate analogue bound at the active site of the enzyme Torpedo californica acetylcholinesterase (TcAChE), and permitted monitoring of subsequent clearance of a radiolysis product from the active site.

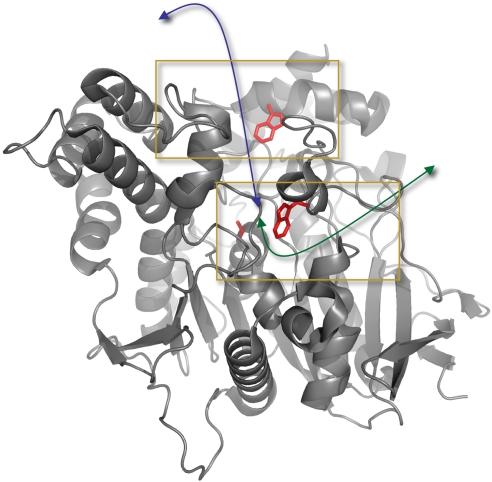

AChE terminates transmission at cholinergic synapses by rapid hydrolysis of the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (ACh) (Fig. 1) to choline (Ch) and acetate (18). The reaction proceeds in two steps. First, the enzyme is acetylated and the Ch-product expelled. Then, a water molecule regenerates the free enzyme with concomitant release of acetic acid. AChE is one of fastest enzymes in nature, with a turnover of 103–104 s−1, and is the target of most currently approved anti-Alzheimer drugs (19), of insecticides (20), and of chemical warfare agents (21). The crystal structure of TcAChE revealed that its active site is buried at the bottom of a deep and narrow gorge (Fig. 2) (22), an unexpected architecture in view of its high catalytic efficiency. Significant molecular breathing motions are essential for traffic of substrate and products to occur along this gorge, and it has been suggested that products may exit the active site via a putative, transiently opened backdoor (23, 24). Structural snapshots of substrate and products bound within the gorge have been obtained recently (25, 26). Binding of a nonhydrolyzable substrate analogue [4-oxo-N,N,N-trimethylpentanaminium iodide (OTMA)] (Fig. 1) in the active site uncovered the structural features of the tetrahedral intermediate state, while the structure of the enzyme in the action of expelling a product analogue at room temperature provided evidence for a transient opening of the backdoor (27). Here, we report the radiolytic breakdown of OTMA in the OTMA/TcAChE complex during collection of a series of crystallographic data sets at 100 and 150 K. Structural changes at 150 K indicate that the enzyme is flexible enough at that temperature to allow the exit of an analogue of the natural hydrolysis product, Ch, from the deeply buried active site. Radiolytic breakdown of substrate analogues, combined with temperature-controlled cryo-crystallography, is suggested as a methodology for studying product traffic and related structural dynamics in other crystalline enzymes.

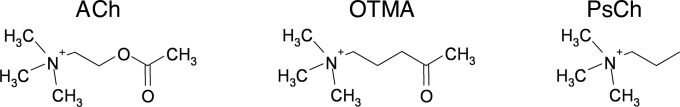

Fig. 1.

Structures of ACh, OTMA, and PsCh.

Fig. 2.

Ribbon diagram of the three-dimensional structure of TcAChE. The two main contributors to the stabilization of the substrate within the active-site (CAS), W84, and at the peripheral site (PAS), W279, are highlighted. The catalytic Ser-200 is shown at the bottom of the gorge. The blue arrow indicates the active-site gorge, and the green arrow highlights the putative backdoor. Lower and Upper Insets. indicate the parts that are expanded in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively.

Results

The substrate analogue OTMA differs from the natural substrate, ACh, only in the replacement of the ester oxygen by a carbon, thus being composed of acetyl (Ac) and pseudo-Ch (PsCh) moieties (Fig. 1); PsCh (n-propyltrimethylammonium) is an analogue of the enzymatic product Ch. OTMA binds, in orthorhombic crystals of TcAChE, at the catalytic anionic subsite (CAS) of the active site and at the peripheral anionic site (PAS), in exactly the same manner as reported for trigonal TcAChE crystals (25) (PDB ID code 2C5F). In the active site, its quaternary nitrogen makes cation-π interactions with Trp-84 and Phe-330, and an electrostatic interaction with the acidic side chain of Glu-199 (Fig. 3A). Its carbonyl oxygen hydrogen bonds to Gly-118N, Gly-119N, and Ala-201N in the oxyanion hole, and its carbonyl carbon is modeled at a covalent-bonding distance from the catalytic Ser-200 Oγ. At the PAS, a second OTMA molecule is bound, with its CH3CO moiety pointing toward the active site. Its quaternary group makes cation-π interactions with the aromatic rings of Trp-279 (see Fig. 4a) and Tyr-70, whereas its carbonyl oxygen is weakly H-bonded to Tyr-121 Oζ.

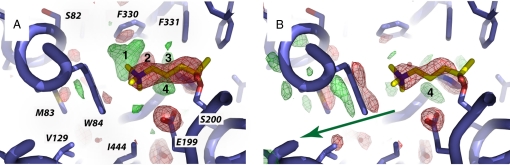

Fig. 3.

OTMA in the CAS of TcAChE at 100 K (A) and 150 K (B). Protein residues are shown in blue, and the OTMA molecule is shown in yellow. The Fourier difference maps (contour level 4σ) computed for data sets IV − I at 100 K (A) and for data sets III − I at 150 K (B), are shown superimposed on the model. Positive and negative peaks are shown in green and red, respectively. Peaks 1–4 are referred to in the text. The arrow in B indicates a putative backdoor exit of PsCh that is also indicated by a green arrow in Fig. 2. The orientation in Fig. 3 is the same as in Fig. S1 but slightly zoomed out. A version for the colorblind is given in Fig. S2.

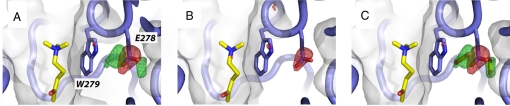

Fig. 4.

OTMA at the PAS of TcAChE. (A and B) The Fourier difference maps (contour level 4σ) computed for data sets IV − I at 100 K (A) and for data sets III − I at 150 K (B) are shown superimposed on the model. Positive and negative peaks are shown in green and red, respectively. (C) Two partially occupied CO2 molecules are fitted in the positive peaks shown in the Fourier difference map at 100 K in A. A version for the colorblind is given in Fig. S3.

Four consecutive data sets (I–IV) were collected from the same volume of a single crystal of an OTMA/TcAChE complex at 100 K. The crystal was then translated, and a second series of four data sets was collected at another spot on the crystal at 150 K [see supporting information (SI) Table S1]. Thus, the two series reveal the x-ray dose-dependent evolution of the OTMA/TcAChE complex at these two temperatures. From the first to the last data set, the resolution deteriorated from 2.3 to 2.4 Å at both temperatures. The cumulative doses absorbed after collection of data sets IV at 100 K and III at 150 K are nearly identical, 0.92 and 0.95 × 107 Gy, respectively. They correspond to approximately one-third of the experimentally determined Garman limit (3 × 107 Gy), above which the biological information extracted from a macromolecular structure is likely to be compromised (28).

Radiolytic Breakdown of OTMA in the Active Site of TcAChE at 100 K.

The OTMA in the CAS of the structure corresponding to data set I at 100 K (PDB ID code 2VJA) is well defined, as judged from 2Fo − Fc composite-omit electron density maps (Fig. S1a), reproducing the structural features reported previously (25). Electron density observed around OTMA is still continuous in data set IV at 100 K (PDB ID code 2VJB) while noticeably thinner (Fig. S1b). A strong negative peak is observed on OTMA in the Fourier difference map (Fig. 3A) computed with observed structure factor amplitudes of data sets I and IV and with calculated phases from model I [(Fo100K-IV − Fo100K-I)·e−iϕ100K-I]. Inspection of B factors revealed a higher loss of definition of the PsCh moiety of OTMA, but not of the Ac group on Ser-200, compared with the loss of definition averaged over all protein and solvent atoms (see Materials and Methods). Radiation-induced cleavage of OTMA into PsCh and an Ac group is thus the most likely scenario. The strong positive peak (1 in Fig. 3A) below Phe-330 indicates that repositioning of the radio-released PsCh occurs within the active site. As a consequence, a water molecule interacting with the PsCh moiety of OTMA changes its position concomitantly, as suggested by a pair of positive and negative peaks (2 and 3 in Fig. 3A). The repositioning of the PsCh moiety occurs just below Phe-330, which, together with Tyr-121 (residue not shown in Fig. 3), forms a bottleneck in the middle of the gorge (22). A negative peak is seen on the Phe-330 phenyl ring in the Fourier difference map (Fig. 3A), as well as on the adjacent Tyr-334 (not shown), suggesting that both residues become partially disordered upon repositioning of the radiation-freed PsCh. The binding locus indicated for PsCh by the positive peak in the Fourier difference map is different from that reported earlier for the steady-state complex of TcAChE with thiocholine (TCh) (25). The positive peak (4 in Fig. 3A) observed behind the acetate moiety of the OTMA molecule in the Fourier difference map had been attributed earlier to a radiation-induced movement of the catalytic His-440 (10).

Negative and positive peaks indicative of well documented damage to acidic residues and disulfide bonds (4–7) are also seen in the difference Fourier map (data not shown).

Radiolytic Breakdown of OTMA in the Active Site of TcAChE at 150 K.

The 2Fo − Fc composite-omit electron density for the OTMA in the CAS of the structure corresponding to data set I at 150 K (PDB ID code 2VJC) is as well defined (Fig. S1c) as the one corresponding to data set I at 100 K (Fig. S1a). However, as the x-ray dose increases, much greater structural changes occur in the active site at 150 K than at 100 K. At a cumulative absorbed dose similar to that for data set IV at 100 K, the 2Fo − Fc composite-omit map of data set III at 150 K (PDB ID code 2VJD) shows poorly defined and discontinuous electron density for the OTMA molecule bound at the CAS (Fig. S1d); only residual density is observed for the PsCh moiety next to Trp-84. The absence of electron-density around the Phe-330 phenyl group in the 2Fo − Fc composite-omit maps (Fig. S1 c and d) indicates that it is more disordered in data sets I and III at 150 K than at 100 K. Analogously, the water molecule interacting with the PsCh moiety of the OTMA molecule in the CAS at 100 K (Fig. S1a) has no discernable electron density in the 2Fo − Fc composite-omit maps calculated for data sets I and III at 150 K (Fig. S1 c and d). Thus, the crystalline enzyme is more flexible at 150 K than at 100 K. The Fourier difference map, calculated with the structure factor amplitudes of data sets I and III at 150 K, and with the calculated phases from model I [(Fo150K-III − Fo150K-I)·e−iϕ150K-I], reveals an elongated negative peak on OTMA in the CAS (Fig. 3B), indicating radiolysis of the substrate analogue. No strong positive peak is seen adjacent to this negative peak, suggesting that the radiolytically generated PsCh does not reposition below Phe-330 at 150 K, as it does at 100 K. In the putative backdoor region, strong positive and negative peaks are observed on the side chains of Met-83, Trp-84, Val-129 (Fig. 3B), and on both the main and side chains of Tyr-442, Ser-79, and Gly-81 (data not shown). Again, the positive peak attributed earlier to a radiation-induced movement of the catalytic His-440 (10) is visible in the CAS (4 in Fig. 3B).

To address the effect of x-ray irradiation on native orthorhombic TcAChE crystals at 150 K, a control experiment was performed, in which a similar cumulative x-ray dose was administered (i.e., 0.94 × 107 Gy, distributed over five consecutive data sets; see SI Materials and Methods). A Fourier difference map was then calculated between the first (control-I) and last (control-V) data set (Fig. S4 and Table S2). Peaks on Trp-84, Met-83, Glu-199 and His-440 are observed (Fig. S4) that are qualitatively similar to those in Fig. 3B.

Radiation-Induced Changes at the Peripheral Substrate-Binding Site (PAS).

At 100 K, two positive peaks are observed in the Fourier difference map next to a negative one on the carboxyl group of Glu-278, the residue adjacent to Trp279 at the PAS (Fig. 4A). No significant negative peak is observed on the OTMA molecule bound at the PAS (Fig. 4 A and B), indicating that it is not affected by x-ray irradiation at 100 and 150 K, and that it does not move from its original position. Unlike at 100 K, no positive peaks are observed at 150 K next to the negative peak on the carboxyl group of Glu-278 (Fig. 4B).

Discussion

Build-Up of an Intermediate at 100 K and Exit of PsCh from the Active Site at 150 K.

Two series of structures were collected, at 100 K and at 150 K, on two separate regions of a single crystal of a complex of TcAChE with the nonhydrolyzable substrate analogue OTMA. At both temperatures, difference Fourier maps indicate loss of definition of the PsCh moiety of OTMA at increased absorbed x-ray doses, which we ascribe to radiolytic cleavage of the substrate analogue into an Ac group on the catalytic Ser-200 and PsCh, an analogue of the enzymatic product, Ch. The series of structures determined at 100 K is interpreted as illustrating the cleavage of the tetrahedral intermediate that forms subsequent to binding of ACh in the CAS (Fig. 3A). PsCh repositions below Phe-330, a residue that is part of a bottleneck at midway down the active-site gorge. Phe-330 is a very mobile residue, and it has been suggested that it is involved in gating of traffic of substrate and products within the gorge (18, 25). The repositioning of PsCh, evidenced by the strong positive peak observed in the Fourier difference map calculated at 100 K, does not overlap with the position of TCh in complex with TcAChE (PDB ID code 2C5G) (25), nor with that observed for TCh or Ch in complex with mouse AChE (PDB ID codes 2HA2 and 2HA3, respectively) (26). This difference might be ascribed either to the more hydrophobic character of PsCh, relative to TCh or Ch, leading to a different binding mode, or to the fact that the structures presented in refs. 25 and 26, although collected at cryo-temperatures, reflect equilibrium states obtained by soaking at room temperature that were trapped upon cryo-cooling.

At 150 K, no signs of reorientation of PsCh are observed after OTMA radiolysis. However, strong negative and positive features in the Fourier difference map (Fig. 3B) indicate a small shift in the equilibrium position of the indole ring of Trp-84 that suggests an exit trajectory (indicated by green arrows in Figs. 2 and 3B) for PsCh and, by analogy, for the natural enzymatic hydrolysis product, Ch, via the putative backdoor (23, 24, 27). A similar, but less pronounced displacement of the indole ring of Trp-84 was observed in a radiation-damage control on native orthorhombic TcAChE crystals at 150 K (Fig. S4 and SI Materials and Methods). Thus, the Trp-84 movement shown in Fig. 3B is partially due to a relaxation at 150 K that might be a local response to radiation-induced changes elsewhere in the enzyme. In any case, the backdoor region is intrinsically more flexible at 150 than at 100 K. Together with the fact that the Fourier difference map is almost featureless at the top of the gorge (Fig. 4B), the observed Trp-84 movement argues that at 150 K PsCh exits predominantly via the backdoor. In a second control experiment, the absence of peaks on Trp-84 in a difference Fourier map computed between data set I100 K and a data set of the native enzyme collected at 100 K (Rmerge of structure factor amplitudes, 18%; data not shown) excluded the possibility that the movement of Trp-84 observed at 150 K (Fig. 3B) is due to unbinding of PsCh from Trp-84.

Our experiments do not allow to determine conclusively the radiochemical mechanism responsible for the cleavage of OTMA (Fig. 1). Secondary electrons or electron holes (7), mobile at both 100 and 150 K, most likely trigger the event by targeting the C–C bond between the Ac group and the PsCh moiety. In the natural substrate, ACh, the equivalent C–O bond between the Ac group and the Ch moiety is weakened by partial electron withdrawal in the tetrahedral intermediate and subsequently cleaved during substrate hydrolysis. OTMA binding in the active site mimics the tetrahedral intermediate that forms during enzymatic hydrolysis of ACh. Consequently, electrons might also be partially withdrawn from the C–C bond between the Ac group and the PsCh moiety in OTMA when it binds to the catalytic Ser-200, thus rendering the Ac carbon electrophilic. An increased radiation-sensitivity of the C–C bond might be the consequence, resulting in the observed OTMA cleavage. Indeed, x-ray irradiation has no significant effect on OTMA bound at the PAS, where ACh binds only transiently en route to the active site, and does not adopt a conformation resembling the transition state. This observation is in agreement with the early proposed “rack-and-strain” theory for enzymatic action, in which strain on the reactive bond is a consequence of the binding of the substrate within the active site of the enzyme (29).

Putative Trapping of Radio-Generated CO2 Molecules at 100 K.

Apart from the structural changes described above that are directly related to the radiolytic breakdown of the substrate analogue OTMA within the active site, most of the radiation damage features observed in the Fourier difference maps have already been reported for the native protein, namely the breakage of disulfide bridges and loss of definition of the carboxyl groups of acidic residues (4, 5, 10). The latter has been interpreted as resulting from the release of a CO2 molecule by decarboxylation (5, 30). However, a previously undescribed feature was observed here for Glu-278, the residue adjacent to Trp-279 whose indole ring is the principal component of the PAS. For Glu-278 at 100 K, not only is a negative peak seen, but also two strong positive peaks on either side of it (Fig. 4A). A partially occupied CO2 molecule could be fitted by real space refinement into each of the two positive peaks (Fig. 4C), and occupancies were estimated to be 5% and 13% (see Materials and Methods for details). Likewise, the occupancy of the Glu-278 carboxyl group was estimated to have been reduced to 79%. We thus suggest that either one or both of these positive peaks might reflect partial occupancy by a CO2 molecule generated by decarboxylation. We conjecture that the Trp-279 indole ring, which blocks access to the active-site gorge, allows trapping of CO2 at 100 K. Indeed, none of the other decarboxylated residues of the enzyme displays such clear and strong positive peaks next to the negative one. The fact that these peaks are absent from the Fourier map at 150 K (Fig. 4B) suggests that, at this temperature, the active-site gorge residues as a whole display sufficient flexibility for the CO2 molecule to escape. Based on IR spectroscopic experiments, it has been reported that migration of photogenerated CO2 in GFP occurs in a similar temperature range (31).

Conclusion and Perspectives

A close interdependency exists between the dynamics of a protein and of its immediate environment (32). Therefore, it is likely that dynamical changes in the hydration-water at the protein surface are involved in the observed change in protein flexibility with temperature (11, 33). Similar results were observed (at both 100 and 150 K) when analogous experimental protocols were conducted on a complex of TcAChE (crystallized in the same space group under the same conditions) with a photolabile precursor of the enzymatic product analogue, arsenocholine, namely “caged arsenocholine” (27) (data not shown), and on a “pro-aged” complex of human butyrylcholinesterase (34) with the organophosphate nerve agent soman (J.-P.C., F. Nachon, B.S., P. Masson, and M.W., unpublished results). These findings indicate that the results described here are neither protein- nor ligand-dependent, and that the Shoot-and-Trap strategy is applicable to other crystalline protein systems. Synchrotron-radiation-induced cleavage at 100 K of a N–S bond in an inhibitor complexed with a liver X receptor has indeed been reported (35).

The use of specific radiation damage, in combination with temperature-controlled cryo-crystallography, is a simple experimental approach capable of providing valuable insight into functional aspects of the structural dynamics of enzymes. Whereas most kinetic crystallography techniques are highly time consuming, and require the use of dedicated equipment and materials (3, 27), the Shoot-and-Trap strategy has the advantages of being fast and accessible, in principle, to any synchrotron user. The experiments described here were indeed performed in less than 2 h, including the temperature ramping from 100 to 150 K, at a typical third-generation insertion-device beamline. Moreover, using only a single crystal throughout the experiment permitted conservation of very high isomorphism between the data sets, which is critical for the calculation of accurate Fourier difference maps (3, 27, 36). Although this method obviously requires predetermination of the radiation damage characteristics of a given native enzyme, it is, nevertheless, theoretically applicable to any crystalline enzyme for which a substrate analogue is available. We propose the Shoot-and-Trap strategy as a simple technique that could allow the standardization of kinetic crystallography studies.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals.

The nonhydrolyzable substrate analogue, OTMA (Fig. 1B), was synthesized according to Thanei-Wyss and Waser (37).

Crystallization of TcAChE and Soaking Procedure.

TcAChE was purified and crystallized as described (22, 38). To obtain the TcAChE/OTMA complex, a large orthorhombic (P212121) crystal (300 × 300 × 50 μm3) was soaked for 2 h at 4°C in a mother liquor solution [30% polyethylene glycol (PEG)200/150 μM morpholinoethanesulfonic acid (Mes), pH 6.0] containing 500 μM OTMA.

Data Collection.

Because of the cryoprotective capacity of PEG200, the crystal was directly flash-cooled in the cryostream of a cooling device (700 series, Oxford Cryosystems) at 100 K. X-ray diffraction data were collected on beamline ID14-EH4 at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility (ESRF) by using the unattenuated beam at a wavelength of 0.932 Å. A first series of four data sets (I–IV) was collected at 100 K on one area of the crystal by using an x-ray beam of dimensions 100 × 100 μm2. Subsequently, the crystal was translated by 200 μm along the spindle axis, and the temperature of the cooling device was increased to 150 K at 360 K/h. A second series of four data sets (I–IV) was then collected at 150 K without changing the beam size. For each of the eight data sets, 180 frames were collected, with an oscillation range of 1° and an exposure time of 1 s per frame. The collection time of each series of four data sets was ≈45 min. The ramping time between 100 and 150 K was ≈10 min. Data sets were indexed, merged, and scaled by using XDS/XSCALE, and structure factor amplitudes were generated by using XDSCONV (39). The resolution limits were 2.3, 2.3, 2.3, and 2.4 Å for the four data sets I100K–IV100K, respectively, and 2.3, 2.3, 2.4, and 2.4 Å for the four data sets I150K–IV150K, respectively. The absorbed x-ray doses after collection of each data set, calculated by using the program RADDOSE (40), were 0.24, 0.23, 0.23, and 0.22 × 107 Gy for I100K–IV100K, respectively, and 0.33, 0.32, 0.30, and 0.30 × 107 Gy for I150K–IV150K, respectively. A refill of the synchrotron storage ring (operating in 16-bunch mode) between data sets IV100K and I150K, resulting in a 35% increase of the ring current, was at the origin of the differences in absorbed doses of the two series. The cumulative x-ray doses after collection of data sets IV100K and III150K were nearly identical (i.e., 0.92 × 107 and 0.95 × 107 Gy, respectively), each corresponding to approximately one-third of the experimentally determined Garman limit of 3 × 107 Gy (28). Statistics and other information concerning data collection are shown in Table S1.

Structure Determination and Refinement.

The native structure of TcAChE in the orthorhombic space group (PDB ID code 1W75) (41) served as the starting model for the rigid body refinement of data set I100K in the resolution range 50–4 Å. Subsequently, the structure underwent simulated annealing to 2,000 K, with slow-cooling steps of 10 K, followed by 250 steps of conjugate-gradient minimization and 20 steps of individual B-factor refinement. The two monomers in the asymmetric unit (A and B) were manually rebuilt and refined independently. Here, all results and figures refer to monomer B; the results for monomer A are very similar and, thus, are not presented. Diffraction data from 50 Å to the resolution limits were used for refinement and electron-density map calculations. The final model for structure I100K (with waters, sugars, OTMA, and ions) served as the starting model for the refinement of the three other structures (IV100K, I150K, and III150K). They underwent rigid-body refinement, simulated annealing to 2,000 K with cooling steps of 10 K, and then 250 steps of conjugate-gradient minimization, followed by 20 steps of individual B-factor refinement. At the end of the refinements, the Fo − Fc maps were virtually featureless at ±3σ. Unbiased initial electron density maps (Fig. S1) were obtained by calculation of composite-omit 2Fo − Fc maps after the rigid-body refinement step. Graphic operations and model building were performed with COOT (42). Refinement and map calculations were performed by using CNS, version 1.1 (43). Fourier difference maps were computed with observed structure factor amplitudes of data sets I100K and IV100K and calculated phases from model I100K [(Fo100K-IV − Fo100K-I)·e−iϕ100K-I], and with observed structure factor amplitudes of data sets I150K and III150K and calculated phases from model I150K [(Fo150K-III − Fo150K-I)·e−iϕ150K-I]. Structure factor amplitude differences were Q weighted to improve the signal-to-noise ratios of the Fourier difference maps (27, 36). Rmerge values of structure factor amplitudes between data sets I100K and IV100K, and between data sets I150K and III150K were 8.2% and 10.7%, respectively. The figures were produced by using PyMOL (44). Molecular topologies and parameters of OTMA were created by using the PRODRG server at the University of Dundee (Dundee, Scotland) (45). Qualities of the structures were checked and validated by using PROCHECK (46). Refinement statistics are shown in Table S1.

Occupancies of OTMA atoms were set to 1 and not refined. Inspection of B factors in IV100K (III150K) with respect to I100K (I150K) revealed mean increases of 11% (24%) and 27% (44%), respectively, for the Ac and PsCh atoms in the CAS. At the PAS, the increases in B factors for the Ac and PsCh atoms were nearly identical, namely 4% (5%). The average B factor for all protein and solvent atoms increased by 8% (17%) between I100K (I150K) and IV100K (III150K) (Table S1).

To estimate the occupancies of the carboxyl group of Glu-278 and nearby putative CO2 molecules in structure IV100K, CO2 molecules were included in the model and fitted by real-space refinement into the two positive difference-density features shown in Fig. 4A. B factors of CO2 molecules were set to the average B factor of Trp-279 side and main chain atoms in structure IV100K (38 Å2), and their occupancies were refined. The occupancies of the two putative CO2 molecules and of the Glu-278 carboxyl group were refined to 0.13, 0.05, and 0.78, respectively. Because of their low occupancies, CO2 molecules were not included in the final model of IV100K (PDB ID code 2VJB), and the occupancy of the Glu-278 carboxyl group was set to 1.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Lilly Toker and Michal Cohen for purification of TcAChE; Raimond Ravelli, Joanne McCarthy, and Elspeth Garman for continuous discussions and help during data collection; Ian Carmichael, Chantal Houée-Levin, and David Milstein for fruitful discussions; David Eisenberg, Richard Dickerson, Duilio Cascio, Michael Sawaya, and Arthur Laganowsky for critically reading the manuscript; and the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility for beamtime under long-term projects MX551 and MX666 (radiation-damage BAG) and MX498 (IBS BAG). This work was supported by the Commissariat à l'Énergie Atomique, the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the Université Joseph Fourier, Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grant JC05_45685 (to M.W.); the National Institutes of Health CounterACT Program; the U.S. Army Defense Threat Reduction Agency; the Nalvyco Foundation, the Kimmelman Center for Biomolecular Structure and Assembly (Rehovot, Israel); the Minerva Foundation (J.L.S.); the Benoziyo Center for Neuroscience (I.S.); the Israel Ministry of Science, Culture, and Sport (the Israel Structural Proteomics Center); the Divadol Foundation; and the European Commission VIth Framework “SPINE2-COMPLEXES” Project (LSHG-CT-2006-031220). J.-P.C. was supported by a Université Joseph Fourier grant and European Molecular Biology Organization Short-Term Fellowship ASTF230-2006. J.L.S. is the Pickman Professor of Structural Biology.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID codes 2vja, 2vjb, 2vjc, 2vjd, 2vt6, and 2vt7).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0804828105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Frauenfelder H, Sligar SG, Wolynes PG. The energy landscapes and motions of proteins. Science. 1991;254:1598–1603. doi: 10.1126/science.1749933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Henzler-Wildman KA, et al. A hierarchy of timescales in protein dynamics is linked to enzyme catalysis. Nature. 2007;450:913–916. doi: 10.1038/nature06407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourgeois D, Royant A. Advances in kinetic protein crystallography. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2005;15:538–547. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weik M, et al. Specific chemical and structural damage to proteins produced by synchrotron radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:623–628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ravelli RB, McSweeney SM. The ‘fingerprint’ that x-rays can leave on structures. Structure Fold Des. 2000;8:315–328. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burmeister WP. Structural changes in a cryo-cooled protein crystal owing to radiation damage. Acta Crystallogr D. 2000;56:328–341. doi: 10.1107/s0907444999016261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ravelli RB, Garman EF. Radiation damage in macromolecular cryocrystallography. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;16:624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ravelli RB, Leiros HK, Pan B, Caffrey M, McSweeney S. Specific radiation damage can be used to solve macromolecular crystal structures. Structure. 2003;11:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schlichting I, et al. The catalytic pathway of cytochrome p450cam at atomic resolution. Science. 2000;287:1615–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5458.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weik M, et al. Specific protein dynamics near the solvent glass transition assayed by radiation-induced structural changes. Protein Sci. 2001;10:1953–1961. doi: 10.1110/ps.09801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weik M, et al. Supercooled liquid-like solvent in trypsin crystals: Implications for crystal annealing and temperature-controlled X-ray radiation damage studies. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2005;12:310–317. doi: 10.1107/S0909049505003316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fioravanti E, Vellieux FM, Amara P, Madern D, Weik M. Specific radiation damage to acidic residues and its relation to their chemical and structural environment. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2007;14:84–91. doi: 10.1107/S0909049506038623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matsui Y, et al. Specific damage induced by X-ray radiatioin and structural changes in the primary photoreaction of bacteriorhodopsin. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:469–481. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter RH, Seagle BL, Ponomarenko N, Norris JR. Specific radiation damage illustrates light-induced structural changes in the photosynthetic reaction center. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:16728–16729. doi: 10.1021/ja0448115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts BR, Wood ZA, Jonsson TJ, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Oxidized and synchrotron cleaved structures of the disulfide redox center in the N-terminal domain of Salmonella typhimurium AhpF. Protein Sci. 2005;14:2414–2420. doi: 10.1110/ps.051459705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leiros HK, Timmins J, Ravelli RB, McSweeney SM. Is radiation damage dependent on the dose rate used during macromolecular crystallography data collection? Acta Crystallogr D. 2006;62:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905033627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dubnovitsky AP, Ravelli RB, Popov AN, Papageorgiou AC. Strain relief at the active site of phosphoserine aminotransferase induced by radiation damage. Protein Sci. 2005;14:1498–1507. doi: 10.1110/ps.051397905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Silman I, Sussman JL. Acetylcholinesterase: ‘Classical’ and ‘non-classical’ functions and pharmacology. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2005;5:293–302. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2005.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greenblatt HM, Dvir H, Silman I, Sussman JL. Acetylcholinesterase: a multifaceted target for structure-based drug design of anticholinesterase agents for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. J Mol Neurosci. 2003;20:369–383. doi: 10.1385/JMN:20:3:369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Casida JE, Quistad GB. Golden age of insecticide research: Past, present, or future? Annu Rev Entomol. 1998;43:1–16. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.43.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Millard CB, Broomfield CA. Anticholinesterases: Medical applications of neurochemical principles. J Neurochem. 1995;64:1909–1918. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64051909.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sussman JL, et al. Atomic structure of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica: A prototypic acetylcholine-binding protein. Science. 1991;253:872–879. doi: 10.1126/science.1678899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ripoll DR, Faerman CH, Axelsen PH, Silman I, Sussman JL. An electrostatic mechanism for substrate guidance down the aromatic gorge of acetylcholinesterase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:5128–5132. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.11.5128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilson MK, et al. Open “back door” in a molecular dynamics simulation of acethylcholinesterase. Science. 1994;263:1276–1278. doi: 10.1126/science.8122110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colletier JP, et al. Structural insights into substrate traffic and inhibition in acetylcholinesterase. EMBO J. 2006;25:2746–2756. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bourne Y, et al. Substrate and product trafficking through the active center gorge of acetylcholinesterase analyzed by crystallography and equilibrium binding. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:29256–29267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603018200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colletier JP, et al. Use of a ‘caged’ analogue to study the traffic of choline within acetylcholinesterase by kinetic crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D. 2007;63:1115–1128. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907044472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Owen RL, Rudino-Pinera E, Garman EF. Experimental determination of the radiation dose limit for cryocooled protein crystals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:4912–4917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600973103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koshland DE, Jr, Neet KE. The catalytic and regulatory properties of enzymes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1968;37:359–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.37.070168.002043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sevilla MD, D'Arcy JB, Morehouse KM. An electron spin resonance study of .gamma.-irradiated frozen aqueous solutions containing N-acetylamino acids. J Phys Chem. 1979;83:2893–2897. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Thor JJ, Georgiev GY, Towrie M, Sage JT. Ultrafast and low barrier motions in the photoreactions of the green fluorescent protein. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:33652–33659. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M505473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fenimore PW, Frauenfelder H, McMahon BH, Young RD. Bulk-solvent and hydration-shell fluctuations, similar to α- and β-fluctuations in glasses, control protein motions and functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14408–14413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405573101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood K, et al. Coincidence of dynamical transitions in a soluble protein and its hydration water: Direct measurements by neutron scattering and MD simulations. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:4586–4587. doi: 10.1021/ja710526r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicolet Y, Lockridge O, Masson P, Fontecilla-Camps JC, Nachon F. Crystal structure of human butyrylcholinesterase and of its complexes with substrate and products. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:41141–41147. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farnegardh M, et al. The three-dimensional structure of the liver X receptor beta reveals a flexible ligand-binding pocket that can accommodate fundamentally different ligands. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:38821–38828. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304842200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ursby T, Bourgeois D. Improved estimation of structure-factor difference amplitudes from poorly accurate data. Acta Crystallogr A. 1997;53:564–575. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thanei-Wyss P, Waser PG. Interaction of quaternary ammonium compounds with acetylcholinesterase: Characterization of the active site. Eur J Pharmacol. 1989;172:165–173. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(89)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sussman JL, et al. Purification and crystallization of a dimeric form of acetylcholinesterase from Torpedo californica subsequent to solubilization with phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C. J Mol Biol. 1988;203:821–823. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90213-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kabsch W. Automatic processing of rotation diffraction data from crystals of initially unknown symmetry and cell constants. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:795–800. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray JW, Garman EF, Ravelli RBG. X-ray absorption by macromolecular crystals: The effects of wavelength and crystal composition on absorbed dose. J Appl Crystallogr. 2004;37:513–522. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Greenblatt HM, et al. The complex of a bivalent derivative of galanthamine with Torpedo acetylcholinesterase displays drastic deformation of the active-site gorge: Implications for structure-based drug design. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:15405–15411. doi: 10.1021/ja0466154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Emsley P, Cowtan K. COOT: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brunger AT, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. San Carlos, CA: DeLano Scientific; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schuttelkopf AW, van Aalten DM. PRODRG: A tool for high-throughput crystallography of protein-ligand complexes. Acta Crystallogr D. 2004;60:1355–1363. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904011679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Crystallogr. 1993;26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.