Abstract

Objective:

There is conflicting evidence regarding the impact of neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES) on adolescent alcohol use. The current study tested whether the prospective effects of neighborhood SES on adolescent alcohol outcomes varied across parental alcoholism subgroups.

Method:

Data from a group of adolescents (N = 361) from an ongoing longitudinal study of children of alcoholics (COAs) and matched controls were collected at three initial annual assessments. Latent growth models were estimated with a range of related time-invariant and time-varying predictors.

Results:

Among non-COAs, higher neighborhood SES predicted increased rates in alcohol use and consequences, whereas among COAs, lower neighborhood SES was predictive of increased rates in alcohol use and marginally predicted rates of consequences. There were also time-specific effects of family mobility on alcohol outcomes.

Conclusions:

The current study provides evidence for differential effects of neighborhood SES on adolescent alcohol use and consequences for non-COAs and COAs. The group differences found in this study may help explain the equivocal findings from previous neighborhood studies, which may use samples with an unmeasured mix of high and low-risk adolescents. Future research should identify pathways to alcohol use and problems for high- and low-risk adolescents living in neighborhoods that span the range of the socioeconomic spec trum.

For several decades, social scientists have examined the impact of physical and social characteristics of neighborhoods on its residents (e.g., Jencks and Meyer, 1990; Shaw and McKay, 1942; Wilson, 1987). The findings from this growing body of research provide evidence that residential context, particularly neighborhood socioeconomic status (SES), appears to influence adolescent outcomes beyond the effects of risk factors at both the family and individual levels. In their seminal review on this topic, Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn (2000) found that indicators of neighborhood poverty were associated with higher levels of externalizing and internalizing behaviors in children (Brooks-Gunn et al., 1993; Chase-Lansdale et al., 1997). Among adolescents, indicators of neighborhood poverty have been shown to be associated with increases in juvenile delinquency (Ingoldsby and Shaw, 2002; Loeber et al., 2002), childhood violence (Stewart et al., 2002), peer-reported aggression (Kupersmidt et al., 1995), externalizing behaviors (Plybon and Kliewer, 2001), and internalizing behaviors (Simons et al., 1996).

Based on this evidence, one would expect low neighbor hood SES to be associated with increased adolescent alcohol use, which is another indicator of problem behavior during this developmental period. However, there is confl icting evidence as to the direction of neighborhood effects on adolescent alcohol use. Several cross-sectional studies have found associations between indicators of neighborhood affluence and increased adolescent substance use (e.g., Ennett et al., 1997) whereas others have shown that indicators of neighborhood poverty were associated with increased adolescent substance use (e.g., Smart et al., 1994). Additional studies reported null effects of neighborhood structural characteristics on adolescent substance use (Allison et al., 1999; Karvonen and Rimpela, 1996; Lee and Cubbin, 2002; Simons et al., 1996; Williams et al., 1997). There appears to be no consistent pattern from these investigations regarding the direction of neighborhood effects on adolescent substance use.

It is possible that moderating variables could help explain the inconsistencies across previous neighborhood studies by demonstrating differential effects across subgroups. Previous evaluations reported that age and gender can condition the effect of neighborhood-level risk factors on adolescent substance use (Karvonen and Rimpela, 1996; Seidman et al., 1998). However, it is possible that other risk factors for adolescent substance use might also moderate the effects of neighborhood SES on adolescent substance use. For example, parental alcoholism—a robust risk factor for adolescent substance use and misuse (Chassin et al., 2004; Harter, 2000; Sher, 1991)—may interact with neighborhood-level SES such that the stress and obstacles associated with living in a high-risk neighborhood could exacerbate the pre-existing risk for substance use among children of alcoholics (COAs), leading to higher levels of substance use and misuse in this subgroup as compared with non-COAs living in similar neighborhoods. However, this hypothesis has never been empirically tested.

The assessment of neighborhood effects on adolescent substance use is difficult, and the majority of studies have been cross-sectional, with a few noteworthy exceptions: Results from the Moving to Opportunity program and Yonkers Projects, both quasi-experimental designs in which families from poorer neighborhoods were selected to move into middle-class neighborhoods, found that moving into a low-poverty neighborhood predicted less access to illegal substances (Fauth et al., 2005) and lower rates of risky behavior (including alcohol and marijuana use) for females but higher rates for males (Kling et al., 2007), respectively. Findings from observational prospective studies of neighborhood effects mirror the lack of consensus found in cross-sectional designs: Hoffman (2002) found that neighborhood poverty indicators predicted adolescent drug use, whereas Luthar and Cushing (1999) found that indicators of neighborhood affluence predicted adolescent drug use in a sample of children of cocaine and opioid addicts. Compounding this issue of lack of consensus findings, additional methodological weaknesses in this literature include confounds attributable to family mobility and a failure to include relevant family-level variables associated with neighborhood residence into their models, making it diffi cult to identify the most relevant neighborhood-level influences. Although a recent investigation found that residency in economically disadvantaged neighborhoods positively predicted alcohol problems 12 years later in a sample of adult males (Buu et al., 2007), no known study has examined the relation between neighborhood SES and problematic forms of alcohol use (e.g., alcohol-related consequences) using a longitudinal design in adolescence.

Accordingly, the goal of the current study was to examine prospective neighborhood SES effects on adolescent alcohol-use outcomes (use and consequences). We capitalized on the longitudinal design by estimating change over time in alcohol outcomes using latent growth models (LGMs) and determining the effects of neighborhood SES on both initial level of alcohol outcomes and growth during the course of adolescence. SES-related family-level variables (e.g., ethnicity and education) were controlled for in order to provide a more accurate estimate of neighborhood-level effects. In addition, confounds attributable to family-level mobility were minimized by using a sample of adolescents who remained either within the same house or within the same type of neighborhood during the assessment period and by treating family mobility as a time-varying covariate. Theprimary goal was to test whether the effects of neighborhood SES on adolescent alcohol outcomes varied for COAs and non-COAs. We hypothesized that there would be a negative relation between neighborhood SES and adolescent alcohol outcomes, such that living in more disadvantaged, low SES neighborhoods would increase risk for adolescent alcohol outcomes, and this relation would be stronger for COAs than for non-COAs.

Method

Participants

Participants were from an ongoing longitudinal study of familial alcoholism (Chassin et al., 1991, 1993, 1999, 2004). At Time 1 (1988), there were 454 adolescents (either Hispanic or non-Hispanic white in ethnicity; mean age = 13.2 years, range: 10.5-15.5 years), 246 of whom were COAs, defined as having at least one biological alcoholic parent who was also a custodial parent, and 208 were demographically matched adolescents who were recruited for the control sample, with no biological or custodial alcoholic parents.

COA families were recruited using court records of arrests for driving under the influence, health maintenance organization wellness questionnaires, and community telephone screening within the Phoenix, AZ, metro area. Direct interview data from the computerized Diagnostic Interview Schedule-Version Three (DIS-III; Robins et al., 1981) confi rmed that a biological and custodial parent met diagnostic criteria for lifetime alcohol abuse or dependence per criteria listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III; American Psychiatric Association, 1980). Demographically matched control families were recruited using telephone interviews through reverse directories to locate families living in the same neighborhood as the COAs, with matching on ethnicity, family structure, and age. Structured interviews were used to confirm that neither parent met lifetime DSM-III criteria for alcohol abuse or dependence. As described elsewhere (Chassin et al., 1991, 1992), the sample was unbiased with respect to alcoholism indicators (i.e., the blood alcohol concentration at time of the arrest was similar to what is expected in the literature), and rates of other psychopathology were similar to those reported for a community-dwelling alcoholic sample (Helzer and Pryzbeck, 1988). However, those who refused participation were more likely to be Hispanic, which suggests that some caution should be taken in generalizing the results. For the current analyses, data were examined from the first three annual adolescent assessments (referred to as Times 1, 2, and 3).

Participants for the current analyses were required to have lived at the same physical residence for each of the three initial annual assessments or, if they moved, to have remained within the same type of neighborhood as characterized by a prior latent class analysis (n = 361). As noted earlier, the rationale for examining only adolescents who remained with a similar neighborhood context across time was to allow for stronger inferences about the relation between neighborhood SES (which remains constant for these adolescents across the three assessments) and the alcohol outcomes at Time 3. At Time 1, the mean (SD) age of this sample was 13.3 (1.4) years old, and increased to a mean age of 15.2 (1.4) years old at Time 3; 47% were girls, 51% had at least one alcoholic parent, and 26% came from families with at least one Hispanic parent. Between Time 1 and Time 3, prevalence rates for any lifetime alcohol use increased from 43% to 58%. There were 93 participants who were dropped from the analyses (because of missing data or having moved into different class of neighborhood); this group was compared with the 361 who were retained in terms of their Time 1 data. The two groups did not differ significantly on gender, family ethnicity, family education, or past-year alcohol and drug use. However, those dropped were younger (12.9 vs 13.3 years old, p < .05), were more likely to have an alcoholic parent (67% vs 51%, p < .01), and came from families with lower self-reported household income ($30,367 vs $40,753; p < .001).

Procedure

Interviews, taking between 1 and 2 hours, were conducted in person by trained personnel using laptop computers; families were paid up to $65 for their participation. To encourage honesty, we reinforced confi dentiality with a Department of Health and Human Services Certificate of Confidentiality.

Measures

Neighborhood socioeconomic status

Neighborhood membership was determined by geo-coding the home addresses of all adolescents in the sample across waves and then matching each home address to a census-defined block group (typically between 600 and 3,000 residents), revealing a total of 357 unique block groups across assessments. The average median household income for this sample was $33,800 in 1990, higher than the Arizona metropolitan average income at that time ($29,000). Census variables from 1990 were obtained for each block group in the subsample, and a total of eight SES variables were identifi ed as meaningful neighborhood predictors of adolescent alcohol use (see Table 1 for descriptive data). A principal components analysis of these variables was used to create a continuous measure of neighborhood SES, which was the main predictor of interest for the subsequent models (see Results).

TABLE 1.

Descriptives of census variables (n = 357 unique block groups)

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean (SD) |

| Male unemployement, % | 0.00 | 12.27 | 2.56 (2.09) |

| Receiving public assistance, % | 0.00 | 39.46 | 5.70 (6.15) |

| Below poverty, % | 0.00 | 83.93 | 12.68 (12.31) |

| Single-parent households, % | 0.00 | 67.71 | 15.38 (8.96) |

| Hispanic, % | 0.00 | 95.89 | 19.02 (20.29) |

| Without high school education, % | 0.49 | 78.60 | 21.59 (15.89) |

| With college degree or higher, % | 0.45 | 69.73 | 24.04 (13.74) |

| Employed in managerial/professional jobs, % | 0.00 | 64.72 | 24.32 (12.11) |

Family education.

At Time 1, parents self-reported their highest level of education, and the higher level reported by either parent was used for the indicator of family-level education. Family education was defi ned by having at least one parent with a college degree or higher (32%). Families with at least one college-educated parent (coded “1”) had a higher mean self-reported family income than did families with no college-educated parents (coded “0”) at Time 1 ($48,140 vs $37,271, p < .001).

Family ethnicity

At Time 1, parents self-reported their ethnicity. If either parent reported being Hispanic (26%), then that family was considered Hispanic (coded “1”) for these analyses. Otherwise, the family-level ethnicity was considered non-Hispanic white (coded “0”).

Family mobility

At Times 1, 2, and 3, family residences were used to identify neighborhoods. For these analyses, the family mobility at Time 2 and Time 3 was coded positive (“1”) if the address reported differed from that given at the assessment from the previous year. Within the current sub-sample of residentially stable families, the majority (89%) reported no moves (coded “0”) across these assessments (n = 321), 9% reported one move (n = 32), and 2% reported two moves (n = 8).

Parental alcoholism.

At Time 1, lifetime DSM-III diagnosis of parent alcoholism (abuse or dependence) was assessed with the DIS-III (Robins et al., 1981). For parents who were not interviewed (24% of fathers, 13% of mothers), lifetime alcoholism diagnosis was established with the Family History-Research Diagnostic Criteria (FH-RDC) criteria on the basis of spouses' reports. Using the FH-RDC may underestimate the prevalence of alcoholism in the parents who were not interviewed (13.5%) because the RDC has higher specificity (>90%) than sensitivity (50%; Cuijpers and Smit, 2001). Parental alcoholism diagnoses were dichotomous: either present (at least one biological parent met lifetime criteria, coded “1”) or absent (neither biological parent met lifetime criteria, coded “0”).

Alcohol use

At Times 1, 2, and 3, adolescents reported their frequency of past-year consumption of beer/wine with responses that ranged from 0 (never) to 7 (every day).

Quantity of consumption ranged from 1 to 9 or more drinks per occasion. A cross-product of these variables (Quantity × Frequency) was computed to index alcohol consumption. The means for alcohol use at the three time points were 1.74 (5.6), 2.68 (6.9), and 4.08 (8.6), respectively. The prevalence for any past-year drinking also increased from 27% to 38% to 46% from Time 1 to Time 2 to Time 3, respectively.

Alcohol consequences

At Times 1, 2, and 3, problem use was measured by adolescent self-report of alcohol-related negative consequences (social, health, academic, and legal consequences), with the sum of these items as the measure of alcohol problems. The means for alcohol consequences at the three time points were 0.19 (1.0), 0.35 (1.1), and 0.47 (1.2), respectively. The prevalence for any past-year drinking consequences increased from 6% to 15% to 18% from Time 1 to Time 2 to Time 3, respectively, with 11% of adolescents endorsing multiple alcohol consequences at Time 3.

Data analytic plan

Alcohol-related behaviors have been shown to increase with age during adolescence (i.e., Johnston et al., 2006). LGMs can be used to capture this change in alcohol outcomes as a function of time by estimating an underlying growth trajectory for each subject in the sample, which is characterized by a starting point (intercept factor) and the rate of change over time (slope or growth factor). Initial evaluations of unconditional LGMs (without covariates)yield the fixed effects of growth (mean value of the intercept and slope factors) and the random effects (variance of the intercept and slope factors) that refl ect individual variability in the starting point and rate of change over time (for an overview, see Bollen and Curran, 2006; Curran and Hus-song, 2003). For the current study, all growth models were estimated using Mplus, Version 5 (Muthén and Muthén, 1998-2007), and the multiple linear regression (MLR) estimator setting (maximum likelihood parameter estimates with standard errors that are robust to nonnormality and nonindependence of observations).

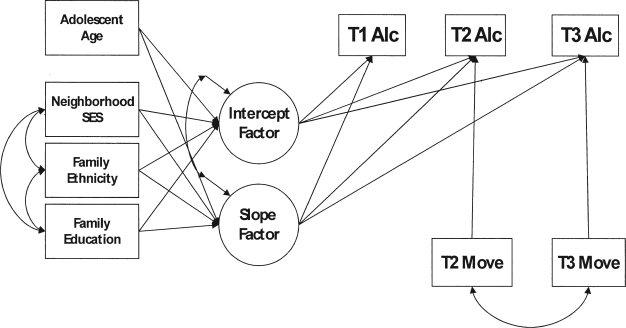

We first estimated separate unconditional LGMs for alcohol use and alcohol consequences. Consistent with previous research (King et al., 2006; Trim et al., 2007), we hypothesized that the mean value for the intercept andslope factors would be significant, indicating a greater than zero value for both use and consequences at Time 1 and a positive increase in both outcomes across these three annual adolescent assessments. Next, we estimated growth models with several time-varying and time-invariant covariates. The predictor variable of interest, neighborhood-level SES, was considered time-invariant and was used to directly predict the intercept and slope factors in the models. To control for possible confounds with family-level processes, both family ethnicity and family education were also considered as time-invariant covariates for these analyses. Adolescent age was also included as a time-invariant covariate because of significant associations with the outcome. Gender was examined in preliminary analyses and was trimmed out of subsequent analyses because of a lack of an association with the outcome within the context of the full LGMs. Family mobility was used as a time-varying covariate, with Time 2 mobility (i.e., family move between Time 1 and Time 2) predicting Time 2 alcohol outcome and Time 3 mobility (i.e., family move between Time 2 and Time 3) predicting Time 3 alcohol outcome. It should be noted that the time-varying mobility covariates were estimated to have a direct effect on the same-time alcohol indicator and not the latent growth factors (see Figure 1 for hypothesized model). Multiple group analyses comparing COA (n = 184) and non-COA subgroups (n = 177) were then conducted on the previously described LGMs separately for alcohol use and consequences to assess the main hypothesis of interest, which was that parental alcoholism would moderate the effects of neighborhood SES on adolescent alcohol outcomes. Specifically, we hypothesized that the relation between neighborhood SES and adolescent alcohol outcomes would be stronger for COAs than for controls, above the effects of family-level risk factors.

FIGURE 1.

Hypothesized full latent growth model–based model with time-invariant and time-varying covariates. Alc = the alcohol outcome (either use or consequences); Move = whether the family changed residences since the previous assessment; SES = socioeconomic status; T = time.

The nested structure of these data (adolescents within block groups) presents a potential analytic challenge as there is potential for interdependence among observations that is not controlled for in traditional regression-based models. However, the design effects in this study, which take into account the intraclass correlations and the average cluster size (1.39 adolescents/block group), are quite small for all outcomes because there is only one adolescent residing within the majority of block groups (186 of 259 Time 1 block groups, 72%). The design effects are approximately 1.1 for both outcomes (a design effect of 2.0 is considered to be a meaningful threshold; Muthén and Satorra, 1995), which suggests that clustering does not pose a problem for a single-level analysis.

Results

Construction of neighborhood socioeconomic status predictor variable

Principal components analysis was conducted on the eight census variables shown to reflect neighborhood-level SES. The number of components retained was based on both the graphical scree test and the Kaiser criterion, which suggests retaining components with eigenvalues greater than 1. Before the principal components analysis, the low SES/poverty variables were recoded such that high scores on the eight SES variables reflected higher levels of SES. In addition, each variable was standardized within the sample of 357 block groups. The rotated solution found that all eight census variables loaded highly on Component 1 (rotated loadings range from .63 to .93), which accounted for 66% of the variance (eigenvalue = 5.31). These loadings were used as a guide to create a continuous neighborhood variable as outlined in previous studies (Allison et al., 1999; Duncan and Aber, 1997). The eight standardized census variables were added together to create a continuous neighborhood SES summary score used as the primary predictor in the analyses. At Time 1, the range for the SES summary score was -20.20 to 12.38 (mean = -.078 [6.19]; block groups could be represented by multiple cases at Time 1, thus the mean of the summaryscores is not equal to zero). The neighborhood SES score did not significantly differ across parent alcoholism groups (F = 2.46, p = .12; COA mean = -0.58, non-COA mean = 0.44). The lack of signifi cant group differences is expected given the original sampling strategy, which made efforts to match COA families with non-COA families in the same neighborhoods.

Unconditional latent growth models

The unconditional LGMs for both alcohol use (χ2 = 1.05, 1 df, p = .31, n = 361; Root Mean Square Error of Approximation [RMSEA] = 0.01; Comparative Fit Index [CFI] = 1.00; Tucker-Lewis Index [TLI] = 1.00; Standardized Root Mean Residual [SRMR] = 0.01) and alcohol consequences (χ2 = 0.36, 1 df, p = .55, n = 361; RMSEA = 0.00; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.01) fi t the data well. Signifi cant variation existed in the intercept factors for alcohol use (b = 29.57, p < .001) and consequences (b = 0.89, p < .001), and both were significantly different from zero. Similarly, there was signifi cant variation in the slope factors for both alcohol use (b = 9.66, p < .001) and consequences (b = 0.21, p < .001), which were also significant, indicating positive increases in time for both alcohol use and consequences. The intercept of alcohol consequences, but not alcohol use, negatively covaried with the slope (b = -0.15, p < .01) such that higher levels of Time 1 alcohol consequences predicted less growth in consequences over time.

Full latent growth model of alcohol use across parental alcoholism groups

The full LGM with time-varying and time-invariant covariates examining alcohol use fit the data well (χ2 = 49.85, 40 df, p = .13, n = 361; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.98; TLI = 0.98; SRMR = 0.04); significant paths for the COA and non-COA subgroups are shown on Figure 2. For the non-COA group, neighborhood SES positively predicted the slope factor for alcohol use (b = .19, p < .05), such that living in a higher SES neighborhood predicted higher rates of increase in alcohol use over time. Neighborhood SES did not predict the intercept factor, suggesting that neighborhood SES was unrelated to alcohol use at Time 1. Family education and ethnicity failed to predict either intercept or slope factor for alcohol use, and there were no effects of mobility on alcohol use at Time 2 or Time 3. Age predicted both the intercept (b = .32, p < .001) and slope (b = .28, p < .001), indicating that older age was associated with higher levels of Time 1 alcohol use and higher rates of increase in alcohol use over time.

FIGURE 2.

Full latent growth model–based model of alcohol use for non-children of alcoholics (non-COAs) (top) and COAs (bottom). Only significant paths are included; refer to the text for the additional model details. Move = whether the family changed residences since the previous assessment; SES = socioeconomic status; T = time.

For the COA group, neighborhood SES negatively predicted the slope factor of alcohol use (b = -.20, p < .05), such that living in a lower SES neighborhood predicted higher rates of increase in alcohol use over time. Neighborhood SES did not predict the intercept factor, and family education and ethnicity did not redict either intercept or slope factor. There was a time-specifi c effect of mobility on alcohol use at Time 3 (b = .19, p = .001), such that moving between Time 2 and Time 3 increased the levels of alcohol use above and beyond the increasing trajectories captured by the growth factors. Age predicted the intercept (b = .42, p < .001), indicating that older age was associated with higher levels of Time 1 alcohol use. COAs and non-COAs differed significantly on the path between neighborhood SES and the slope factor of alcohol use using a chi-square test of model fit (χ2 = 6.86, 1 df, p < .01).

Full latent growth model of alcohol consequences across parental alcoholism groups

The full LGM with time-varying and time-invariant covariates examining alcohol consequences fit the data well (χ2 = 45.81, 40 df, p = .24, n = 361; RMSEA = 0.03; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.05); significant paths for the COA and non-COA subgroups are shown on Figure 3. For the non-COA group, neighborhood SES positively predicted the slope factor for alcohol consequences (b = .23, p < .01), such that living in a higher SES neighborhood predicted higher rates of increase in alcohol consequences over time. Neighborhood SES did not predict the intercept factor, suggesting that neighborhood SES was unrelated to alcohol consequences at Time 1. Family education and ethnicity failed to predict either intercept or slope factor for alcohol consequences. There was a time-specifi c effect of mobility on alcohol consequences at Time 2 (b = .15, p < .05), such that moving between Time 1 and Time 2 increased the levels of alcohol consequences above and beyond the increasing trajectories captured by the growth factors. Age predicted both the intercept (b = .35, p < .01) and slope (b = .36, p < .01), indicating that older age was associated with higher levels of Time 1 alcohol consequences and higher rates of increase in alcohol consequences over time.

FIGURE 3.

Full latent growth model–based model of alcohol consequences for non-children of alcoholics (non-COAs) (top) and COAs (bottom). Only significant paths are included, please refer to the text for the additional model details. Dashed lines indicate marginal effects (p < .10). SES = socioeconomic status; T = time.

For the COA group, neighborhood SES negatively, but marginally, predicted the slope factor of alcohol consequences (b = -.14, p = .10), such that living in a lower SES neighborhood was somewhat predictive of higher rates of increase in alcohol consequences over time. Neighborhood SES did not predict the intercept factor, and family education and ethnicity did not predict either intercept or slope factor. The time-specific effects of mobility were a trend at both Time 2 (b = .08, p = .08) and Time 3 (b = .11, p = .07), such that moving at either time marginally increased the levels of alcohol consequences above and beyond the increasing trajectories captured by the growth factors. Age predicted the intercept (b = .27, p < .001), indicating that older age was associated with higher levels of Time 1 alcohol consequences. COAs and non-COAs differed significantly on the path between neighborhood SES and the slope factor of alcohol consequences using a chi-square test of model fit (χ2 = 6.03, 1 df, p < .05).

Discussion

This study examined the prospective relations of neighborhood SES to adolescent alcohol-use outcomes using a high-risk sample of COAs and demographically matched controls. The work had several methodological advantages over previous studies, including using a true longitudinaldesign, estimating trajectories of alcohol use and consequences as outcomes, examining adolescents who remained either within the same house or type of neighborhood across assessments, treating mobility as a time-varying covariate, and controlling for potentially confounding family-level variables. Previous findings from mostly cross-sectional neighborhood studies had been mixed regarding the strength and direction of neighborhood effects on adolescent substance use, and no study had yet determined the extent to which neighborhood effects could be generalized to a high-risk COA population.

The effects of neighborhood SES on rates of growth in alcohol use and consequences were signifi cant for non-COAs, for whom residing in neighborhoods with higher economic advantages was predictive of greater increases in adolescent alcohol use and consequences compared with peers living in lower SES neighborhoods. Although not consistent with our original hypothesis, this replicates previous work comparing substance use in affluent suburban and poor inner-city adolescents (i.e., Luthar and D'Avanzo, 1999). At the neighborhood level, affluence may be associated with a large proportion of homes with less parental supervision (because of permissive or absent parents), increasing the opportunity for adolescent drinking across the neighborhood. These high SES areas may also contain more drinking peers who provide opportunities and positive drinking norms for adolescents residing within the neighborhood.

Among COAs, there was a significant effect of neighborhood SES on increases in alcohol use and a marginal effect on increases in consequences that was in the opposite direction. These findings suggest that COAs residing in lower SES neighborhoods may be at higher risk for increasing alcohol use and consequences compared with their counterparts in higher SES neighborhoods, which is consistent with our original hypothesis. Neighborhood disadvantage may “unmask” vulnerability to adolescent substance use through interaction with pre-existing risk factors (i.e., parental alcoholism), leading to higher levels of substance use and problems for COAs as compared with non-COAs in similar neighborhoods (Brown and Harris, 1978; Cutrona et al., 2005). This finding is consistent with the concept of “nestedness” that was developed by Zucker et al. (1995), which suggests that in alcoholic families at the highest risk level, multiple co-occurring risk factors result in an elevated risk for substance-use problems among the children. COAs in these high-risk families have an aggregation of risk factors (could include residing in lower SES neighborhoods) that increases the risk for adolescent alcohol use. The mechanisms through which low neighborhood SES can influence adolescent alcohol use include lack of community resources and activities, poor social control, lack of adult role models and supervision, and environmental stress. Interestingly, the opposite directions of the effect of neighborhood SES for COA and non-COA adolescents may help to explain the equivocal findings from previous neighborhood studies. That is, samples that contain an unidentifi ed mix of high- and low-risk adolescents would aggregate effects that occur in opposite directions. Depending on the mix of high- and low-risk adolescents in the sample, the effects of neighborhood SES might appear as positive, negative, or nonsignificant.

Although it was not the focus of the current study, there were significant effects of family mobility on adolescent substance use. For COAs, mobility predicted use at Time 3 and marginally predicted consequences at both times, whereas mobility predicted consequences at Time 2 for non-COAs only. The effect of time-varying covariates on indicators within the LGM framework has been described as “shocks” to the overall trajectories of interest (Hussong et al., 2004). In other words, the process of moving residences in adolescence was a proximal risk factor that produced time-specific elevations in alcohol outcomes above and beyond their overall increasing trajectories. The effect of mobility in increasing risk for alcohol outcomes may reflect a causal process (i.e., moving as a risk factor for alcohol use attributable to stress, separation from peers) or it may instead be a marker for more global familial risk factors (i.e., adolescents moving because of divorce/separation of parents). Another intriguing finding was the lack of association between neighborhood SES and Time 1 alcohol use and consequences as represented by the intercept factor. This could be because of low baseline rates of alcohol use at these early ages (73% abstinent) and/or the possibility that neighborhood-level mechanisms that would influence alcohol-related behaviors are not present in early adolescence when parental supervision and structured activities are likely to be higher.

Several studies have examined the implications of neighborhood-level prevention and intervention efforts (Aneshensel and Sucoff-McNeely, 2003; Caughy et al., 1999; Roosa et al., 2005). Most research of this type has focused on the role of poverty as a risk factor for negative outcomes, and many neighborhood-informed intervention efforts have focused on relieving the negative effects of poverty (e.g., fostering community and social ties, attempts to reduce crime through watch programs). Findings from the current study suggest that continued efforts to prevent or intervene with adolescent alcohol use may be particularly helpful for COA adolescents living in low SES neighborhoods. In addition, the findings suggest that non-COA adolescents living in high SES neighborhoods are also at risk for alcohol-use problems. There are unique risk factors associated with high SES neighborhoods (i.e., isolation, social norms that include high achievement pressures, and easier access to alcohol) that seem to put non-COA adolescents at increased risk for alcohol use and problems. Children of affluence have received little attention in the substance-use literature, and no known substance-prevention efforts have specifically targeted adolescents living in high SES neighborhoods (Luthar, 2003). Further research is needed to assess the degree to which prevention programs previously designed for high-risk adolescents are appropriate for adolescents living in affluent neighborhoods.

Although the present study makes several meaningful contributions to the neighborhood literature and improves on previous methodology, several limitations should be noted. First, this data set was not originally designed to study the neighborhood effects on adolescent outcomes, and, as such, there was inadequate clustering within block groups to warrant hierarchical analyses that provide more reliable estimates of effects within and between neighborhoods. Ideally, neighborhood-based studies should use a sampling strategy to ensure that certain types of neighborhoods are included and that there are enough individuals per neighborhood unit to conduct hierarchical analyses (Leventhal and Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Second, caution is required in generalizing these findings to larger populations as the sample likely does not contain many families living in the societal extremes of neighborhood SES (e.g., utterly impoverished and highly affl uent areas). Furthermore, the adolescents were assessed in the Phoenix area in the late 1980s and may not be representative of the general population today. Finally, the current neighborhood measures were limited to indicators of structural features (i.e., census-based SES variables), and there were no available data on the more informative aspects of neighborhood social process such as social capitol (“the value of the social networks embodied in various communities, and the trust and reciprocity that flows from these networks”; Putnam, 2000, p.1), collective efficacy (“the linkage of mutual trust and the shared willingness to intervene for public good”; Sampson et al., 2002, p. 457), and the presence of institutional resources such as neighborhood clubs, organizations, and facilities. Future research should examine these forms of social processes to determine pathways to alcohol use and problems for adolescents living across a range of neighborhood SES classes, possibly as a function of pre-existing risk status.

Footnotes

This research was supported by National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism grant 016213 to Laurie Chassin. Portions of these data were presented at the annual meeting of the Research Society on Alcoholism, July 2007, Chicago, IL.

References:

- Allison KW, Crawford I, Leone PE, Trickett E, Perez-Febles A, Burton LM, LeBlanc R. Adolescent substance use: Preliminary examinations of school and neighborhood context. Amer. J. Commun. Psychol. 1999;27:111–141. doi: 10.1023/A:1022879500217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III), Washington, DC, 1980.

- Aneshensel, C.S and Sucoff McNeely, C.A. Neighborhood and adolescent mental health: Structure and experience. In: Socioeconomic Conditions, Stress and Mental Disorders: Toward a New Synthesis of Research and Public Policy Washington, DC: Mental Health Statistics Improvement Program, Center for Mental Health Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2003(available at: www.mhsip.org).

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent Curve Models: A Structural Equation Perspective. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Klebanov PK, Sealand N. Do neighborhoods influence child and adolescent development? Amer. J. Sociol. 1993;99:353–395. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris T. Social Origins of Depression: A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. New York: Free Press; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Buu A, Mansour M, Wang J, Refior SK, Fitzgerald HE, Zucker RA. Alcoholism effects on social migration and neighborhood effects on alcoholism over the course of 12 years. Alcsm Clin. Exp. Res. 2007;31:1545–1551. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00449.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caughy MOB, O'Campo P, Brodsky AE. Neighborhoods, families, and children: Implications for policy and practice. J. Commun. Psychol. 1999;27:615–633. [Google Scholar]

- Chase-Landale PL, Gordon RA, Brooks-Gunn J, Klebanov PK. Neighborhood and family infl uences on the intellectual and behavioral competence of preschool and early school-age children. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol. 1: Context and Consequences for Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 79–118. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Barrera M, Bech K, Kossak-Fuller J. Recruiting a community sample of adolescent children of alcoholics: A comparison of three subject sources. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1992;53:316–319. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Flora DB, King KM. Trajectories of alcohol and drug use and dependence from adolescence to adulthood: The effects of familial alcoholism and personality. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2004;113:483–498. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.4.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pillow DR, Curran PJ, Molina BSG, Barrera M., Jr Relation of parental alcoholism to early adolescent substance use: A test of three mediating mechanisms. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1993;102:3–19. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Pitts SC, Delucia C, Todd M. A longitudinal study of children of alcoholics: Predicting young adult substance use disorders, anxiety, and depression. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1999;108:106–119. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.1.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Rogosch F, Barrera M. Substance use and symptom-atology among adolescent children of alcoholics. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991;100:449–463. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Smit F. Assessing parental alcoholism: A comparison of the Family History Research Diagnostic Criteria versus a single-question method. Addict. Behav. 2001;26:741–748. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00155-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM. The use of latent trajectory models in psychopathology research. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2003;112:526–544. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrona CE, Russell DW, Brown PA, Clark LA, Hessling RM, Gardner KA. Neighborhood context, personality, and stressful life events as predictors of depression among African American women. J.Abnorm. Psychol. 2005;114:3–15. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Aber JL. Neighborhood models and measures. In: Brooks-Gunn J, Duncan GJ, Aber JL, editors. Neighborhood Poverty, Vol. 1: Context and Consequences for Children. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1997. pp. 62–78. [Google Scholar]

- Ennett ST, Flewelling RL, Lindrooth RC, Norton EC. School and neighborhood characteristics associated with school rates of alcohol, cigarette, and marijuana use. J. Hlth Social Behav. 1997;38:55–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauth RC, Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. Early impacts of moving from poor to middle-class neighborhoods on low-income youth. Appl. Devel. Psychol. 2005;26:415–439. [Google Scholar]

- Harter SL. Psychosocial adjustment of adult children of alcoholics: A review of the recent empirical literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2000;20:311–337. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(98)00084-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helzer JE, Pryzbeck TR. The co-occurrence of alcoholism with other psychiatric disorders in the general population and its impact on treatment. J. Stud. Alcohol. 1988;49:219–224. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1988.49.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman JP. The community context of family structure and adolescent drug use. J. Marr. Fam. 2002;64:314–330. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Curran PJ, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Carrig MM. Substance abuse hinders desistance in young adults' antisocial behavior. Devel. Psychopathol. 2004;16:1029–1046. doi: 10.1017/s095457940404012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS. Neighborhood contextual factors and early-starting antisocial pathways. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2002;5:21–55. doi: 10.1023/a:1014521724498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Meyer SE. Lynn LE Jr, Mcgeary MGH, editors. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; Inner City Poverty in the United States. 1990:111–186.

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; Monitoring the Future: National Results on Adolescent Drug Use: Overview of Key Findings, 2005, NIH Publication No. 06–5882. 2006

- Karvonen S, Rimpela A. Socio-regional context as a determinant of adolescents' health behaviour in Finland. Social Sci. Med. 1996;43:1467–1474. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(96)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Meehan BT, Trim RS, Chassin L. Marker or mediator? The effects of adolescent substance use on young adult educational attainment. Addiction. 2006;101:1730–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01507.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kling JR, Liebman JB, Katz LF. Experimental analysis of neighborhood effects. Econometrica. 2007;75:83–119. [Google Scholar]

- Kupersmidt JB, Griesler PC, Derosier ME, Patterson CJ, Anddavis PW. Childhood aggression and peer relations in the context of family and neighborhood factors. Child Devel. 1995;66:360–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00876.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RE, Cubbin C. Neighborhood context and youth cardiovascular health behaviors. Amer. J. Publ. Hlth. 2002;92:428–436. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: The effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychol. Bull. 2000;126:309–337. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS. The culture of affluence: Psychological costs of material wealth. Child Devel. 2003;74:1581–1593. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-8624.2003.00625.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cushing G. Neighborhood influences and child development: A prospective study of substance abusers' offspring. Devel. Psychopathol. 1999;11:763–784. doi: 10.1017/s095457949900231x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, D'Avanzo K. Contextual factors in substance use: A study of suburban and inner-city adolescents. Devel. Psychopathol. 1999;11:845–867. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User's Guide, Version 5. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998-2007. [Google Scholar]

- Muthén B, Satorra A. Complex sample data in structural equation modeling. In: Marsden PV, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington, DC: American Sociological Assn; 1995. pp. 267–316. [Google Scholar]

- Plybon LE, Kliewer W. Neighborhood types and externalizing behavior in urban school-age children: Tests of direct, mediated, and moderated effects. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2001;10:419–437. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam RD. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Helzer JE, Crougan J, Ratcliff KS. National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule: Its history, characteristics, and validity. Arch. Gen. Psychiat. 1981;38:381–389. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1981.01780290015001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Deng S, Ryu E, Burrell GL, Tein JY, Jones S, Lopez V, Crowder S. Family and child characteristics linking neighborhood context and child externalizing behavior. J. Marr. Fam. 2005;67:515–529. [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Rev. Sociol. 2002;28:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Seidman E, Yoshikawa H, Roberts A, Chesir-Teran D, Allen L, Friedman JL, Abar JL. Structural and experiential neighborhood contexts, developmental stage, and antisocial behavior among urban adolescents in poverty. Devel. Psychopathol. 1998;10:259–281. doi: 10.1017/s0954579498001606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw CR, Mckay HD. Juvenile Delinquency and Urban Areas. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press; 1942. [Google Scholar]

- Sher KJ. Children of Alcoholics: A Critical Appraisal of Theory and Research. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Simons RL, Johnson C, Beaman J, Conger RD, Whitbeck LB. Parents and peer group as mediators of the effect of community structure on adolescent problem behavior. Amer. J. Commun. Psychol. 1996;24:145–171. doi: 10.1007/BF02511885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart RG, Adlaf EM, Walsh GW. Neighbourhood socio-economic factors in relation to student drug use and programs. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse. 1994;3(1):37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart EA, Simons RL, Conger RD. Assessing neighborhood and social psychological influences on childhood violence in an African American sample. Criminology. 2002;40:801–829. [Google Scholar]

- Stouthamer-Loeber M, Loeber R, Wei E, Farrington DP, Wikstrom P-OH. Risk and promotive effects in the explanation of persistent serious delinquency in boys. J. Cons. Clin. Psychol. 2002;70:111–123. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trim RS, Meehan BT, King KM, Chassin L. The relation between adolescent substance use and young adult internalizing symptoms: Findings from a high-risk longitudinal sample. Psychol. Addict. Behav. 2007;21:97–107. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.1.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Scheier LM, Botvin GJ, Baker E, Miller N. Risk factors for alcohol use among inner-city youth: A comparative analysis of youth living in public and conventional housing. J. Child Adolesc. Subst. Abuse. 1997;6(1):69–90. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy. Chicago, IL: Univ. of Chicago Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Fitzgerald HE, Moses HD. Emergence of alcohol problems and the several alcoholisms: A developmental perspective on etiologic theory and life course trajectory. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Manual of Developmental Psychopathology, Vol. 2: Risk,Disorder, and Adaption. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1995. pp. 677–711. [Google Scholar]