Summary

Heterochromatic gene silencing at the pericentromeric DNA repeats in fission yeast requires the RNA interference (RNAi) machinery. The RNA-Induced Transcriptional Silencing (RITS) complex mediates histone H3 lysine 9 (H3K9) methylation and recruits the RNA-Dependent RNA Polymerase Complex (RDRC) to promote double-strand RNA (dsRNA) synthesis and siRNA generation. Here we show that ectopic expression of a long hairpin RNA bypasses the requirement for chromatin-dependent steps in siRNA generation. The ability of hairpin-produced siRNAs to silence homologous sequences in trans is subject to local chromatin structure, requires HP1, and correlates with antisense transcription at the target locus. Furthermore, although hairpin siRNAs can be produced in the absence of RDRC, trans-silencing of reporter genes by hairpin-produced siRNAs is completely dependent on the dsRNA synthesis activity of RDRC. These results provide new insights into the regulation of siRNA action and reveal roles for cis-dsRNA synthesis and HP1 in siRNA-mediated heterochromatin assembly.

Introduction

RNAi is a conserved and widespread silencing mechanism, which is mediated by small interfering RNA (siRNA) molecules and regulates gene expression at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels (Fire et al., 1998; Grewal and Moazed, 2003; Hannon, 2002; Martienssen et al., 2005; Meister and Tuschl, 2004). In posttranscriptional gene silencing, siRNAs (or microRNAs) are generated from double-stranded RNA (dsRNA) by Dicer, a ribonuclease III enzyme, and load onto Argonaute proteins in the RNA-Induced Silencing Complex (RISC) to guide messenger RNA degradation or translational repression (Bernstein et al., 2001; Gregory et al., 2005; Hammond et al., 2001; Hutvagner and Zamore, 2002; Liu et al., 2004; Song et al., 2003). In the fission yeast, Schizosaccharomyces pombe, centromere-associated DNA repeats are transcribed and give rise to siRNAs (Reinhart and Bartel, 2002), and heterochromatin formation at these repeats requires components of the RNAi pathway (Volpe et al., 2002).

Heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast involves the methylation of H3K9 by the conserved histone methyltransferase Clr4 (orthologous to Su(var)3-9), which creates a binding site for HP1 proteins, Swi6 and Chp2 (Nakayama et al., 2000; Nakayama et al., 2001; Sadaie et al., 2004; Thon and Verhein-Hansen, 2000). HP1/Swi6 and H3K9 methylation are required for transcriptional silencing of reporter genes placed in heterochromatic regions (Allshire et al., 1994; Grewal and Klar, 1996). Current models for RNAi-mediated heterochromatin assembly propose that siRNAs guide the RITS complex to nascent centromeric transcripts (Bühler et al., 2006; Motamedi et al., 2004; Verdel et al., 2004). The RITS complex containing Ago1, the GW-repeat protein Tas3, and the chromodomain protein Chp1, then tethers centromeric RNAs to the chromosome by siRNA-dependent base pairing with the nascent transcript and the association of its Chp1 subunit with H3K9-methylated nucleosomes (Bühler et al., 2006; Motamedi et al., 2004). This leads to recruitment of RDRC, which contains the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase Rdp1, the Hrr1 helicase, and the Cid12 polyA polymerase family protein, and the synthesis of dsRNA (Motamedi et al., 2004; Sugiyama et al., 2005). The dsRNA is processed by Dicer (Dcr1) into siRNAs, which initially load onto the ARC complex, containing Ago1 and two conserved protein Arb1 and Arb2 (Buker et al., 2007; Colmenares et al., 2007). Subsequently , the siRNA is transported to RITS to complete the siRNA amplification cycle. Chromatin- and RNA-associated RITS also recruits the Clr4-Rik1-Cul4 (CLRC) complex (Hong et al., 2005; Horn et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2008), which mediates H3K9 methylation, stabilizing RITS on chromatin. Finally, full silencing of centromeric reporter genes is mediated by a combination of transcriptional gene silencing and co-transcriptional degradation of nascent transcripts (Bühler et al., 2007; Bühler et al., 2006; Murakami et al., 2007).

In metazoan RNAi systems, hairpin RNAs are preferentially processed by the Dicer ribonuclease into siRNAs, which mediate gene silencing (Meister and Tuschl, 2004). In addition, endogenous RNAi-related systems use hairpin RNA structures to generate small RNAs, such as microRNAs (Bartel, 2004). Hairpin RNAs, which form precursors for siRNA generation without the requirement for enzymatic dsRNA synthesis, have provided valuable tools for studies of the RNAi mechanism in vivo. In fission yeast, a previous study showed that expression of a long GFP hairpin RNA results in siRNA generation and silencing of a GFP target gene at the post-transcriptional level, but this silencing was not accompanied by changes in chromatin structure of the target GFP locus and occurred in a RITS-independent manner (Sigova et al., 2004).

We have previously shown that siRNAs generated by tethering of the RITS complex to the ura4+ transcript act primarily in cis and could only rarely silence a second allele of ura4+ in trans (Bühler et al., 2006). In this study, we explored the potential of hairpin RNAs to induce RNAi-dependent gene silencing and heterochromatin formation in fission yeast. We found that long ura4+ hairpin RNAs generated siRNAs independently of RDRC or heterochromatin components, which are required for conversion of the native noncoding centromeric RNAs into siRNA. The ability of hairpin RNAs to induce heterochromatin formation in trans depended on the chromosomal location of the target ura4+ gene, correlated with the presence of antisense transcription at the target ura4+ locus, and required Swi6/HP1 in a step downstream of H3K9 methylation. Moreover, even though hairpin-siRNAs were produced in the absence of RDRC, hairpin-induced silencing required RDRC and the dsRNA synthesis activity of RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. These results uncover a previously unforeseen role for Swi6/HP1 in initiation of siRNA-mediated heterochromatin assembly and suggest that RDRC-mediated dsRNA synthesis at target loci is a key step in heterochromatin assembly with role(s) beyond siRNA amplification.

Results

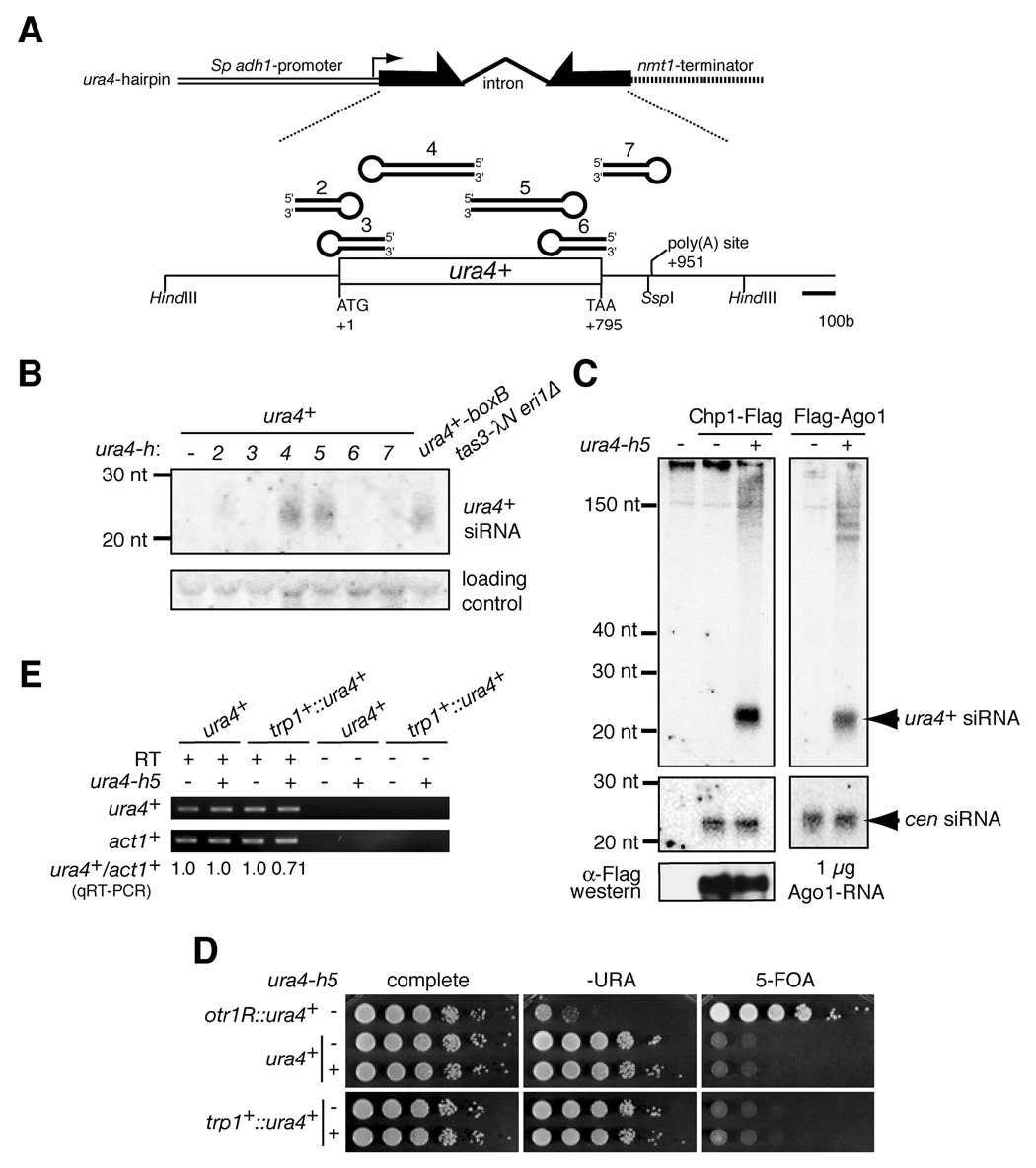

Generation of siRNAs from a long hairpin

To gain further insight into the central role of siRNAs in heterochromatic gene silencing, we designed constructs to express long hairpin RNAs complementary to the transcribed region of the endogenous ura4+ gene (ura4-h2 to -h7) from the strong S. pombe adh1 promoter and integrated each construct into the chromosomal nmt1+ locus (Figure 1A). Two of the longer hairpin constructs, ura4-h4 and -h5, generated detectable siRNAs at levels comparable to ura4+ siRNAs generated by tethering RITS to the ura4+ transcript in eri1Δ cells (Figure 1B)(Bühler et al., 2006), which we have previously shown could act in trans to weakly induce heterochromatin formation and silencing of a ura4+ copy inserted at the leu1+ locus (Bühler et al., 2006). We focused on the ura4-h5 construct, since the shorter hairpins did not produce detectable siRNA, and ura4-h4 was unable to induce silencing (described later). To determine whether ura4-h5 siRNAs were loaded onto the RITS complex, we immunopurified the Chp1 and Ago1 subunits of RITS and probed them for the presence of ura4+ and centromeric siRNAs by northern blotting. As shown in Figure 1C, ura4-h5 siRNAs were present in both Chp1-FLAG and FLAG-Ago1 immunoprecipitates as were cen siRNAs. It has been proposed that the siRNAs guide RITS to specific chromosome regions to initiate heterochromatin formation and silencing (Motamedi et al., 2004; Verdel et al., 2004). To determine whether ura4-h5 siRNAs could mediate ura4+ silencing, we performed growth-silencing assays in which reduced ura4+ expression allows growth on medium containing 5-FOA. We observed no effect on the growth of two different ura4+ strains, containing ura4+ at its endogenous chromosomal location or inserted at the trp1+ locus, in the presence or absence of the ura4-h5 hairpin (Figure 1D, locations 6 and 7 in Figure S1). Moreover, ura4-h5 had no effect on the levels of ura4+ RNA in cells carrying ura4+ at its endogenous location but consistently caused a small reduction (<1.5-fold) in the levels of ura4+ RNA in trp1+::ura4+ cells (Figure 1D and Figure S2). Consistent with these observations, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay of ura4+ showed no significant enrichment of Swi6 and H3K9 methylation by ura4-h5 introduction (data not shown and Figure 2C middle panel). These results indicated that ura4+ hairpin siRNAs, although loaded onto the RITS complex, were not sufficient to induce heterochromatin formation and trans-silencing at the ura4+ loci tested above.

Figure 1. Hairpin constructs generate siRNAs but do not mediate silencing.

A, Schematic diagram of hairpin constructs, ura4-h2, -h3, -h4, -h5, -h6 and -h7, of the ura4+ gene. B, siRNAs from each hairpin construct were detected by northern analysis. As a control, siRNAs in RITS-tethered strain (ura4+-boxB tas3-λN eir1Δ) are also shown. C, Hairpin-induced siRNAs associate with RITS and Ago1. RNAs associated with Flag-tagged Chp1 or Ago1 in ura4+ cells with or without ura4-h5 were analyzed by northern blotting. D, 10-fold serial dilutions of cells with a ura4+ gene inserted at centromeric outer-repeat (otr1R::ura4+), wild-type locus (ura4+) or trp1+ promoter region (trp1+::ura4+) were spotted on non-selective synthetic complete medium, -URA, or 5-FOA medium to monitor growth and silencing. E, ura4+ and act1+ transcripts were analyzed by reverse-transcription (RT) PCR. Relative amounts of ura4+/ act1+ in ura4+ or trp1+::ura4+ strains were also determined by quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) and indicated below the panels.

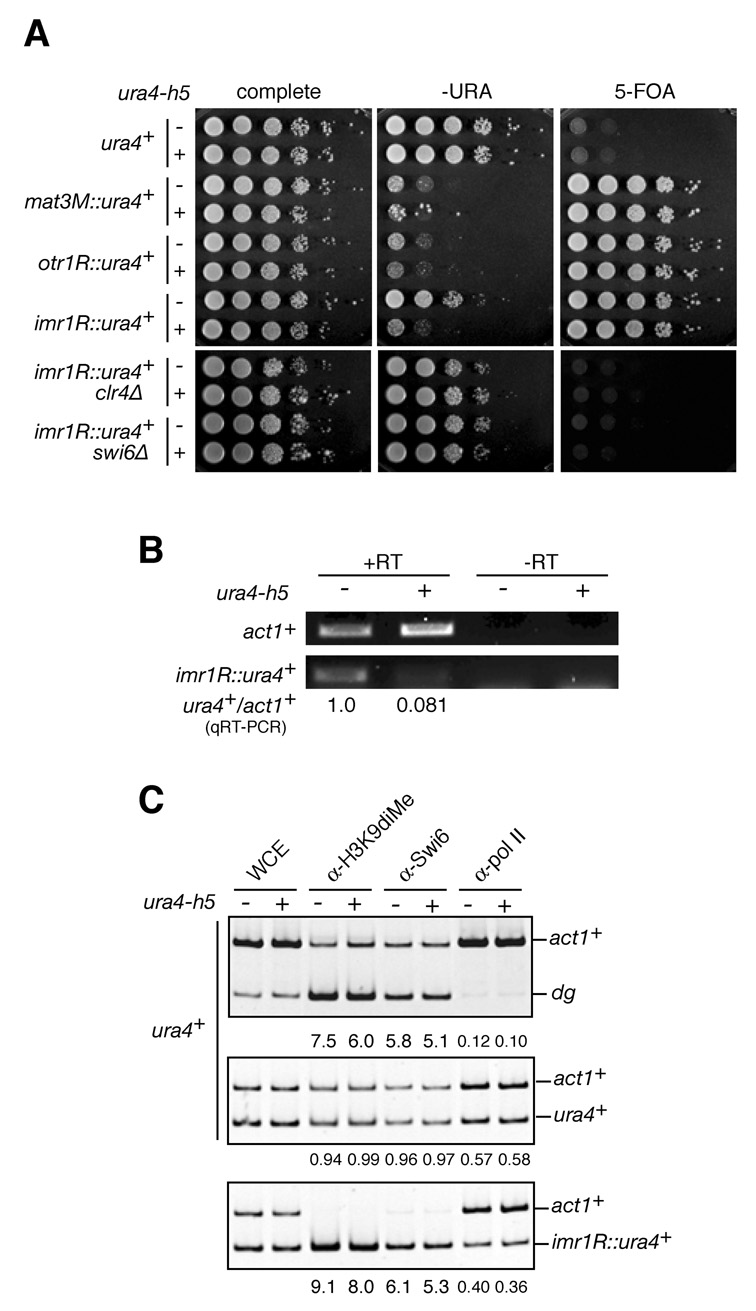

Figure 2. Hairpin siRNAs can act in trans to enhance the silencing of centromeric ura4+ transgenes.

A, ura4-h5 enhanced silencing at heterochromatic regions. 10-fold serial dilutions of cells with a ura4+ gene at wild-type locus, or inserted at the silent mating-type locus (mat3M::ura4+), centromeric outer-repeat (otr1R::ura4+), or innermost-repeat (imr1R::ura4+) were spotted on the indicated medium to monitor silencing as in Figure 1E. B, imr1R::ura4+ and act1+ transcripts were analyzed by RT-PCR and qRT-PCR as in Figure 1D. C, ura4-h5 did not cause a detectable change in H3K9 methylation, Swi6 localization, or RNA pol II occupancy at ura4+ target loci. ChIP assay of ura4+ or imr1R::ura4+ strains were performed with histone H3K9dime, Swi6, or pol II antibodies. Relative fold-enrichment for the heterochromatic dg repeat or target ura4+ genes versus the act1+ internal control is indicated below each panel.

Hairpin siRNAs act in trans to enhance heterochromatic gene silencing

The ability of siRNAs to target nascent transcripts is likely to be linked to association of RITS with nucleosomes that contain H3K9 methylation. In fact, Chp1, the chromo-domain protein subunit of RITS, binds to methylated H3K9 and its binding is required for RITS-dependent heterochromatin assembly (Noma et al., 2004; Partridge et al., 2002; Sadaie et al., 2004). Furthermore, RITS-mediated RDRC recruitment and dsRNA synthesis require Clr4 and H3K9-mediated tethering to the chromosome (Motamedi et al., 2004). In order to determine whether the ability of hairpin siRNAs to execute gene silencing requires the presence of H3K9 methylation, we took advantage of the observation that ura4+ insertions into heterochromatin regions, such as the silent mating-type loci and pericentromeric repeats, result in heterochromatin dependent transcriptional gene silencing (TGS) and RNA degradation known as co-transcriptional gene silencing (CTGS)(Allshire et al., 1994; Bühler et al., 2007; Grewal and Klar, 1996). We tested whether the ura4-h5 siRNAs could act in trans to increase the silencing of heterochromatic ura4+ transgenes, which are usually silenced with varying efficiencies. We introduced ura4-h5 into cells with the ura4+ gene at the silent mating-type locus (mat3M::ura4+)(Grewal and Klar, 1996), centromeric outer repeat (otr1R::ura4+), or innermost repeat (imr1R::ura4+)(Allshire et al., 1994). Epigenetic silencing of the ura4+ gene inserted in heterochromatic loci allows cells to grow on medium containing 5-FOA, which is toxic to Ura4 expressing cells. However, cells carrying ura4+ in heterochromatin can also grow on medium lacking uracil (-URA), depending on the strength of silencing at the particular locus. For example, strong silencing at the matM3 and out1R loci is associated with poor growth of cells carrying ura4+ at these loci, whereas weaker silencing at imr1R allows cells carrying ura4+ at this locus to grow on –URA medium (Figure 2A). We found that ura4-h5 increased the efficiency of the weaker silencing at imr1R::ura4+, as evidenced by reduced growth on – URA medium (Figure 2A). Much smaller increases in ura4-h5-dependent silencing were also evident for the mat3M::ura4+ and otr1R::ura4+ loci, which were already strongly silenced in the absence of the hairpin (Figure 2A). Using quantitative RT-PCR, we found that the ura4-h5 hairpin caused a 12-fold reduction in the levels of the ura4+ transcript in imr1R::ura4+ cells (Figure 2B). However, despite this dramatic decrease in ura4+ transcript levels, ura4-h5 did not promote a detectable increase in either H3K9 methylation or Swi6 recruitment at the imr1R::ura4+ locus (Figure 2C, bottom panel). Furthermore, increased silencing of imr1R::ura4+ was not accompanied by a decrease in RNA polymerase II (pol II) occupancy (Figure 2C, bottom panel). As controls for the ChIP experiments, we observed high levels of H3K9 methylation and Swi6 binding, and diminished pol II occupancy at the centromeric dg repeats and the imr1R::ura4+ transgene (Figure 2C, upper and lower panels, respectively), but not at the endogenous ura4+ locus (Figure 2C, middle panel). Thus, the ability of siRNAs to silence is sensitive to the chromatin environment of the target gene. Moreover, increased silencing does not result from changes in chromatin structure that would exclude pol II from the imr1R::ura4+ locus and is probably due to RNAi-mediated co-transcriptional degradation of the ura4+ transcript.

In order to further examine whether the ability of ura4-h5 siRNAs to act in trans was sensitive to specific structural features of centromeric heterochromatin, rather than unknown differences in the structures of the cen::ura4+ inserts, we tested whether ura4-h5 could induce silencing of the imr1R::ura4+ transgene in clr4Δ or swi6Δ cells. In contrast to wild-type cells (Figure 2A, upper panels), ura4-h5 did not induce silencing in either clr4Δ or swi6Δ cells (Figure 2A, bottom panels). For clr4Δ cells, we attributed this to the absence of H3K9 methylation, which is required for stable RITS binding. However, swi6+ deletion has little or no effect on centromeric H3K9 methylation (Nakayama et al., 2001; Sadaie et al., 2004). Therefore, together these results demonstrate a role for H3K9 methylation, and an additional role for Swi6 subsequent to H3K9 methylation, in siRNA-mediated trans-silencing.

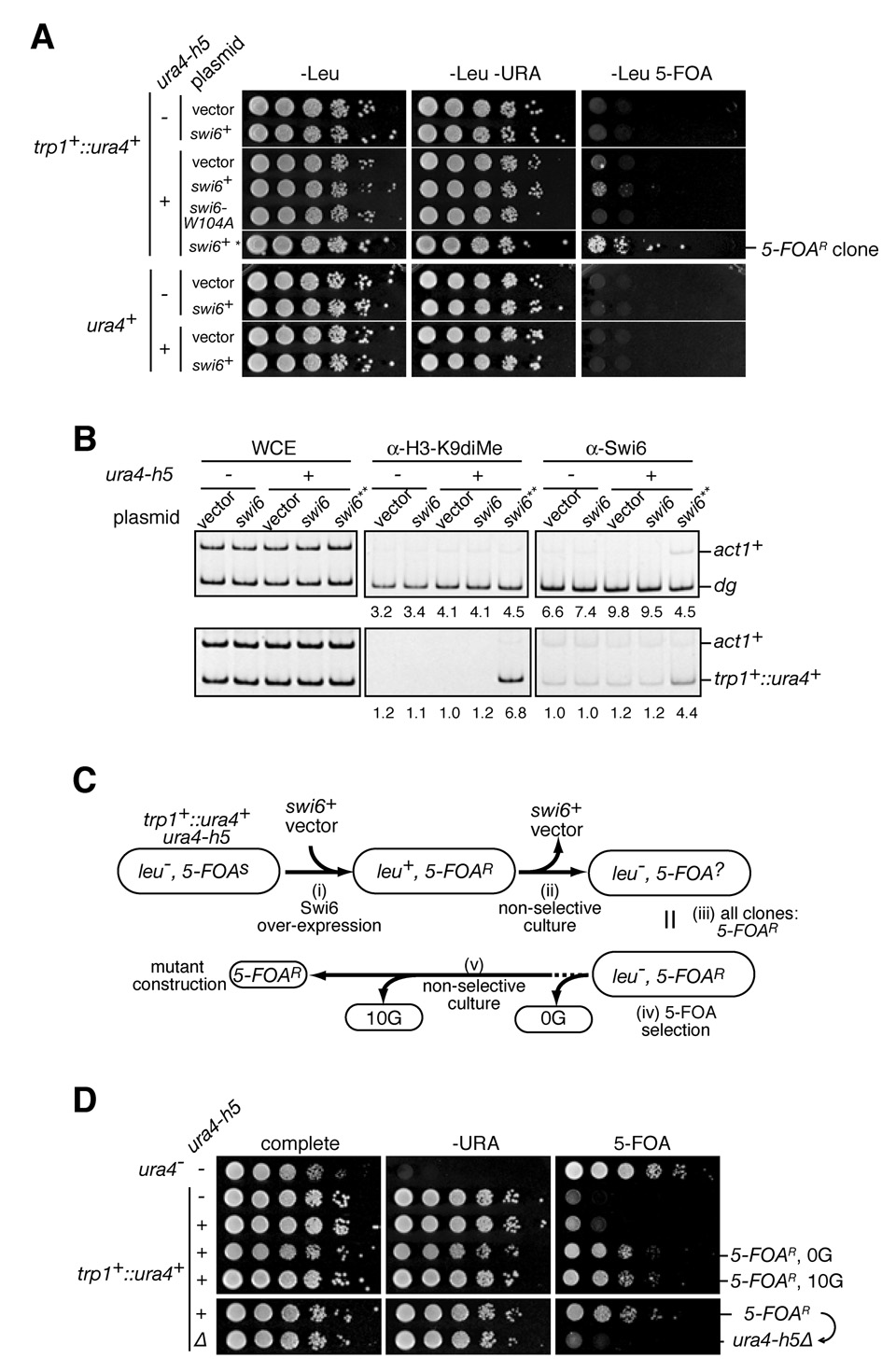

Swi6 overexpression allows hairpin-dependent ectopic establishment of silent chromatin

The requirement for Swi6 in ura4-h5-mediated enhancement of silencing at the centromeric imr1R::ura4+ gene prompted us to further investigate the role of Swi6 in siRNA-mediated gene silencing. It has recently been shown that although H3K9 methylation is present at high levels only at heterochromatic DNA regions (Cam et al., 2005), lower levels of H3K9 methylation occur throughout the genome to various degrees (Cam et al., 2005; Gordon et al., 2007; Lan et al., 2007). Since H3K9 methylation in the absence of Swi6 did not support ura4-h5-mediated silencing of the centromeric imr1R::ura4+ reporter (Figure 2A), we reasoned that limiting levels of Swi6 may restrict the ability of siRNAs to act in trans at chromosomal regions that reside outside of heterochromatic nuclear domains. If true, Swi6 overexpression may allow hairpin siRNAs to act in trans more readily to establish de novo H3K9 methylation. Consistent with this idea, we found that Swi6 overexpression from the nmt1 promoter gave rise to 5-FOA-resistant colonies in trp1+::ura4+ cells in a ura4-h5-dependent manner (Figure 3A). This silencing was not mediated by an increase in ura4-h5 hairpin siRNA levels as siRNA levels did not increase in Swi6 overexpressing cells (Figure S3). The 5-FOA resistant clones (5-FOAR) isolated from Swi6 overexpressing cells subsequently gave rise to robust growth on 5-FOA medium, which suggests that once established silencing at trp1+::ura4+ locus is stably inherited (Figure 3A, top). We next used ChIP to determine whether this silencing was accompanied by changes in the chromatin structure of trp1+::ura4+ locus. As shown in Figure 3B, silencing associated with ura4-h5 and Swi6 overexpression resulted in H3K9 methylation and Swi6 recruitment to the trp1+::ura4+ locus, suggesting that hairpin siRNAs established heterochromatin formation at the target locus in collaboration with Swi6. Swi6 binds to H3K9me through its chromo-domain, which is required for efficient heterochromatic gene silencing (Nakayama et al., 2001; Sadaie et al., 2004; Bannister et al, 2001). We found that overexpression of a chromo-domain mutant, Swi6-W104A, which impairs the ability of the human homolog of Swi6 (HP1) to bind to H3K9me (Jacobs and Khorasanizadeh, 2002), did not support hairpin-mediated silencing establishment (Figure 3A). We did not observe ura4-h5-dependent silencing of the endogenous ura4+ locus even in combination with Swi6 overexpression (Figure 3A, bottom), indicating that this locus was refractory to hairpin-induced heterochromatin formation (Figure S1, location 7). These results suggest that the binding of Swi6 to an H3K9 methylated nucleosome, either transiently induced by hairpin siRNAs or present at low levels prior to hairpin introduction, is required for siRNA-mediated silencing and the amplification of H3K9 methylation.

Figure 3. Swi6 overexpression allows siRNAs to establish de novo H3K9 methylation and silencing in trans in a locus-specific manner, but is only transiently required for hairpin-induced silencing.

A, Swi6 overexpression allows ura4h-5 to silence trp1+::ura4+ but not endogenous ura4+. Cells harboring empty vector or the Swi6 overexpression plasmid were plated on the indicated medium to assess growth and silencing. swi6-W104A contains a point mutation in the chromodomain and does not support ura4-h5-mediated silencing. Asterisk (*) indicates a 5-FOA-resistant clone isolated from trp1+::ura4+ ura4h-5 cells with Swi6 overexpressing plasmid. B, ChIP assays showing ura4-h5-dependent histone H3K9 methylation and Swi6 recruitment at trp1+::ura4+ locus (bottom). The centromeric dg repeat is shown as a positive control (top). Double asterisk (**) shows 5-FOA-resistant clone grown in 5-FOA containing medium as in A followed by growth on rich medium lacking 5-FOA. C, Schematic diagrams of isolation and characterization of the trp1+::ura4+ ura4h-5 epiallele. 5-FOA-resistant clones generated by Swi6 overexpression (i) were cultured in non-selective medium to wean the Swi6-expressing plasmid (ii). All the clones without plasmids could generate 5-FOA resistant cells (iii) and were grown on 5-FOA medium (iv). 5-FOA resistant cells were grown for ten or more generations under non-selective conditions (v). D, Silencing assays showing that hairpin induced silencing was stably inherited in the absence of Swi6 overexpression but required the continuous expression of hairpin RNA. 5-FOA resistant cells (0G) and non-selectively cultured cells (10G) were used for silencing assays. The hairpin deleted derivatives from 5-FOA resistant clone are shown in the lower panel.

Stable inheritance of hairpin-mediated silencing

We next determined whether continuous Swi6 overexpression was required to maintain hairpin-induced silencing. We propagated the 5-FOAR clone on non-selective medium and isolated clones that had lost the swi6+ plasmid (Figure 3C). All such isolated clones (>10) generated 5-FOA resistant colonies (Figure 3C, data not shown). To test whether 5-FOAR clones stably maintained the silent state, 5-FOAR clones after 10 generations of growth (10G) in non-selective medium, or without growth under non-selective conditions (0G), were subjected to silencing assays. Silencing of ura4+ was maintained at a similar efficiency 10 generations after loss of the Swi6 overexpressing plasmid (Figure 3D, compare 5-FOAR, 0G with 5-FOAR, 10G). Moreover, 5-FOAR derivative clones growing on medium lacking uracil still were able to generate 5-FOA resistant colonies, indicating that the trp1+::ura4+ allele could switch between the expressed and silent states (data not shown). In contrast, deletion of ura4-h5 from cells carrying the 5-FOAR silent epi-allele resulted in loss of silencing (Figure 3C; Figure 3D, bottom). These results indicate that the inheritance of hairpin-induced silencing does not require continuous Swi6 overexpression but is dependent on continuous generation of hairpin siRNAs.

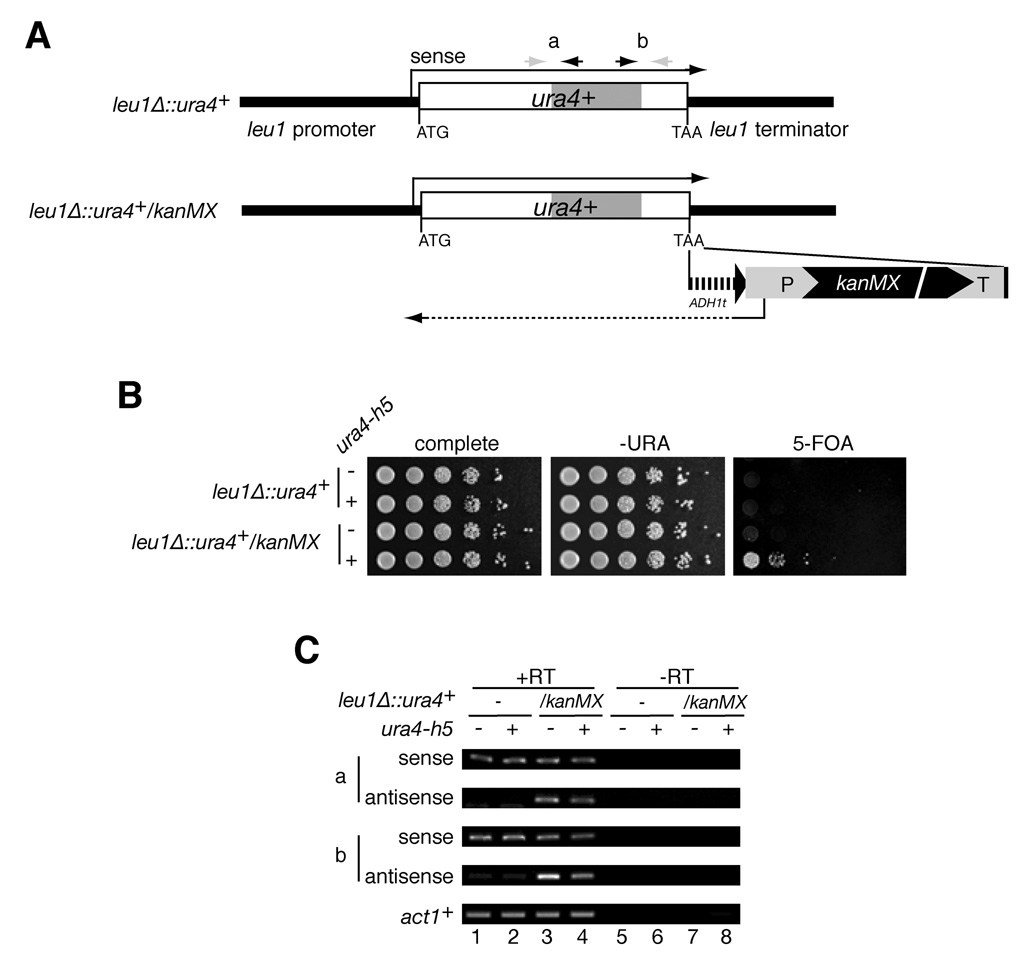

The ability of hairpin siRNAs to induce silencing correlates with antisense transcription at the target locus

The results described above indicate that the ability of hairpin siRNAs to induce chromatin-dependent silencing in trans is sensitive to H3K9 methylation at the target locus (Figure 2) or the availability of Swi6 (Figure 3 A, B). However, these observations do not provide an obvious explanation for the difference in sensitivity of the endogenous ura4+ and trp1::ura4+ toward hairpin-induced silencing, and suggest the existence of other difference between these loci that make the former refractory to hairpin-induced silencing. Apart from H3K9 methylation and Swi6 binding, centromeric repeats are characterized by transcription from convergent promoters that give rise to sense and antisense transcripts. These transcripts serve as templates for dsRNA synthesis and RNAi-mediated H3K9 methylation. Consistent with the idea that convergent transcription may play an important role in siRNA-mediated silencing, we observed strong ura4 antisense transcription at the trp1::ura4+ locus but not at the endogenous ura4+ locus (Figure S4A and B). Moreover, the imr1R::ura4+ locus, which was a strong target for ura4-h5 siRNAs (Figure 2), also displayed strong antisense transcription, particularly in dcr1Δ cells, in which RNAi-mediated processing of transgene RNAs is abolished (Figure S4C). We further examined this correlation between hairpin-induced silencing and antisense transcription for two copies of the ura4+ gene inserted at the leu1+ locus. The first copy, leu1Δ::ura4+, was constructed using a gene replacement strategy that resulted in replacement of the leu1+ gene with the ura4+ gene (Figure 4A). The second copy, leu1Δ::ura4+/kanMX, was constructed by replacement of the leu1+ gene with a ura4+ kanamycin resistance cassette (Figure 4A). We had previously observed weak trans-silencing of the leu1Δ::ura4+/kanMX locus in eri1Δ cells by ura4+ siRNAs that were generated by tethering of the Tas3 subunit of the RITS complex to the RNA of the endogenous ura4+ gene (Bühler et al., 2006). Surprisingly, ura4-h5 siRNAs, which were present at levels similar to those of ura4+ siRNA in tethered Tas3-λN cells (see Figure 1B), failed to induce any silencing at the leu1Δ::ura4+ locus (Figure 4B, upper 2 rows). However, ura4-h5 hairpin induced efficient silencing at the leu1Δ::ura4+/kanMX locus (Figure 4B, bottom 2 rows). Consistent with a possible role for antisense transcription, we observed antisense transcription at the leu1Δ::ura4+/kanMX but not at the leu1Δ::ura4+ locus (Figure 4C, compare lanes 1 and 2 with 3 and 4). These results suggest that antisense transcription or other structural changes that are mediated by the insertion of the kanMX antibiotic resistance marker downstream of the ura4+ gene can change its susceptibility to silencing by ectopically produced hairpin siRNAs.

Figure 4. Antisense transcription at the target locus correlates with the ability of ura4-h5 hairpin to induce silencing.

A, Schematic diagram of two different ura4+ replacements of leu1+, leu1Δ::ura4+ and leu1Δ::ura4+/kanMX. The two loci are identical, except that the latter contains an ADH1 terminator and kanMX antibiotic resistance marker downstream of the inserted ura4+ sequences. a and b denote pairs of primers used for RT-PCR assays in B. B, RT-PCR assays showing antisense transcription at the leu2Δ::ura4+/kanMX but not the leu2Δ::ura4+ locus. C, Growth silencing assays showing that the ura4-h5 hairpin induced silencing at the leu2Δ:: ura4+/kanMX but not the leu2Δ:: ura4+ locus.

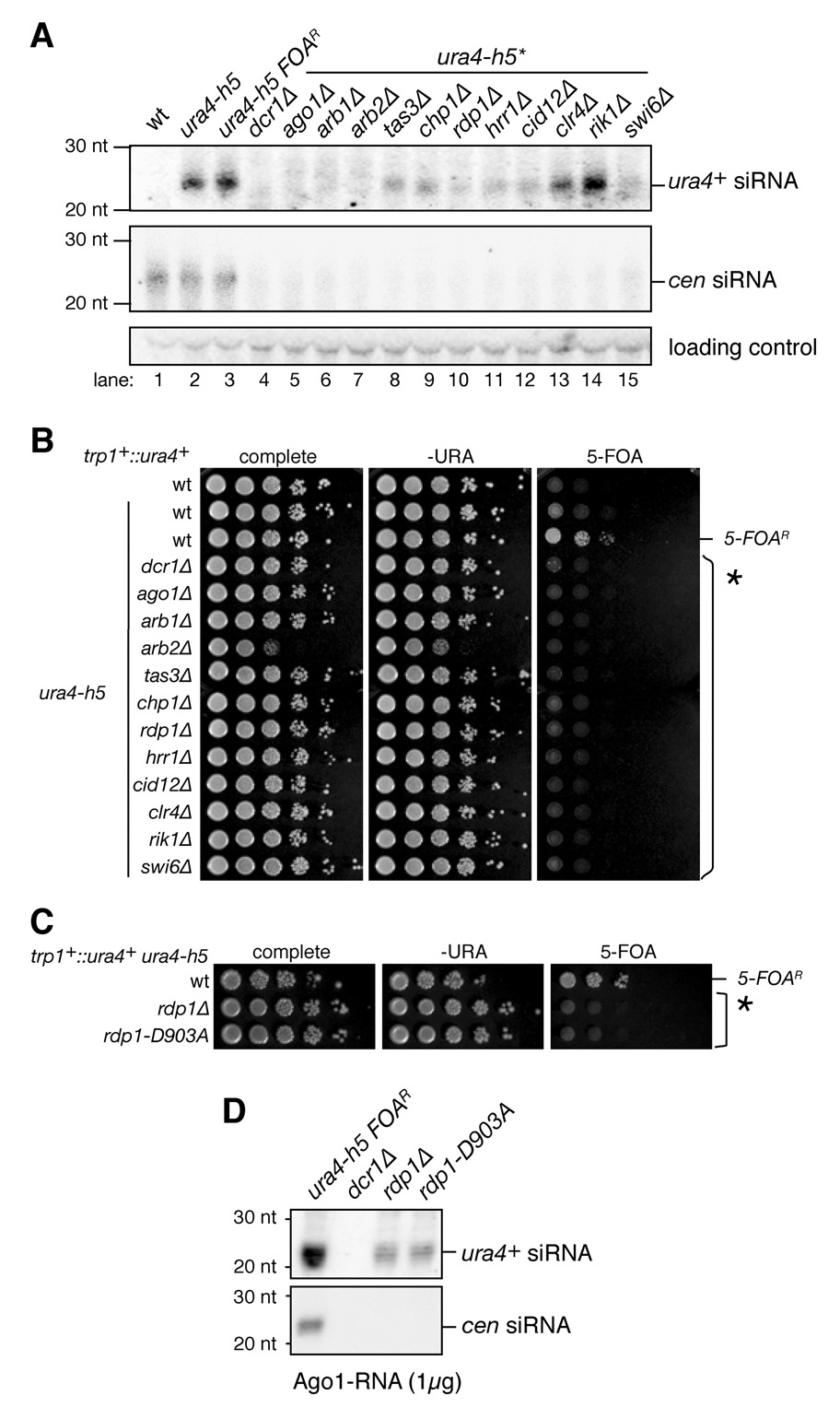

Hairpin siRNA generation does not require RDRC function

The generation of centromeric siRNAs in fission yeast requires components of the RNAi machinery as well as several heterochromatin proteins, including the CLRC H3K9 methyltransferase complex (Bühler et al., 2006; Hong et al., 2005; Motamedi et al., 2004; Noma et al., 2004). The hairpin-dependent silencing system described above provided the opportunity to ask whether the requirements for either siRNA generation or hairpin-mediated silencing were distinct from those previously described for the endogenous system at centromeres. We were particularly interested in testing whether siRNA generation from the long hairpin required RDRC or chromatin components. Northern blot analysis of ura4+ siRNAs, generated by the ura4-h5 hairpin, indicated that ura4-h5 siRNA generation required Dcr1, Ago1, Arb1, and Arb2 (Figure 5A, lanes 1–7). In contrast to centromeric siRNAs, hairpin siRNAs were generated largely independently of H3K9 methylation, as hairpin siRNA levels were present at wild-type levels in cells lacking either the Clr4 methyltransferase or the Rik1 subunit of the CLRC complex (Figure 5A, lanes 13–14). In cells lacking the Chp1 and Tas3 subunits of the RITS complex, or any of the RDRC subunits (Rdp1, Hrr1, and Cid12), we observed intermediate levels of hairpin siRNAs (Figure 5A, lanes 8–12). Surprisingly, siRNA levels were also dramatically reduced in swi6Δ cells (Figure 5A, lane 15). Together, these results indicate that siRNA generation from a long dsRNA hairpin is mediated by Dcr1 and requires the ARC chaperone complex, but occurs independently of H3K9 methylation. The partial requirement for RITS and RDRC subunits is likely due to the role of these complexes in generation of secondary siRNAs. The previously described H3K9me- and RITS-dependent recruitment of RDRC to chromatin is therefore likely to be the rate limiting step in dsRNA generation that is bypassed by the hairpin (Motamedi et al., 2004; Noma et al., 2004). Moreover, the presence of hairpin siRNAs in rik1Δ and clr4Δ cells but their absent in swi6Δ cells reveals a role for Swi6/HP1 in RNAi and siRNA generation that is independent of H3K9 methylation.

Figure 5. Requirements for ura4-h5-induced siRNA generation and silencing.

A, Size-fractionated small RNAs isolated from dcr1Δ, RITS mutants (tas3Δ and chp1Δ), RDRC mutant (rdp1Δ, hrr1Δ, and cid12Δ), CLRC mutants (clr4Δ and rik1Δ), and swi6Δ were analyzed by northern blotting. B, C, Silencing assay using a cell carrying a ura4-h5 and Swi6-induced silent copy of trp1+::ura4+ and its indicated mutant derivatives. RNAi and heterochromatin complexes are indicated on the left in panel B. D, Pull-downs assays showing that hairpin siRNAs were associated with Ago1 in rdp1Δ and rdp1-D903A mutant cells. The rdp1-D903A mutant is a catalytic point mutant of rdp1+.

Hairpin-induced silencing requires RDRC as well as heterochromatin factors

Since siRNA generation from ura4-h5 was partially RDRC-independent, we predicted that ura4-h5-induced silencing of the trp1+::ura4+ locus may occur independently of RDRC, but would still require the remaining components of the pathway. As expected, silencing required Dcr1, ARC (Ago1, Arb1, and Arb2), RITS (ago1, Tas3, and Chp1), and CLRC (Clr4, Rik1) complex components (Figure 5B), which mediate siRNA generation from the hairpin and would be required for heterochromatin assembly (Figure 5A and B)(Bühler et al., 2006; Buker et al., 2007; Hong et al., 2005; Verdel et al., 2004; Volpe et al., 2002). We found that hairpin-induced silencing was also abolished when genes encoding any subunit of RDRC were deleted (rdp1Δ, hrr1Δ, and cid12Δ)(Figure 5B). To determine whether the requirement for RDRC reflected a requirement for dsRNA synthesis, we tested the effect of a catalytically inactive Rdp1 mutation (rdp1-D903A) on hairpin-induced silencing. As shown in Figure 5C, hairpin-induced silencing was abolished in rdp1-D903A mutant cells. The absolute requirement for RDRC in hairpin-mediated silencing was surprising, because hairpin siRNAs were still produced in RDRC mutant cells, albeit to lower levels (Figure 5A). To further characterize the requirement for Rdp1 hairpin siRNA generation, we used a more sensitive FLAG-Ago1 pull-down assay to examine the levels of hairpin-produced siRNAs in wild type, dcr1Δ, rdp1Δ, and rdp1-D903A mutant cells. As shown in Figure 5D, hairpin siRNA levels, bound to FLAG-Ago1, were reduced by approximately 2-fold in rdp1Δ and rdp1-D903A mutant cells relative to wild-type cells. In contrast, no centromeric siRNAs were present in Ago1 pull-downs in either rdp1 mutant (Figure 5D). As expected, no hairpin or centromeric siRNAs were observed in dcr1Δ cells (Figure 5D). The requirement for RDRC components and Rdp1 activity in hairpin-induced silencing suggests that dsRNA synthesis or siRNA amplification at the target locus may play a key role in silencing.

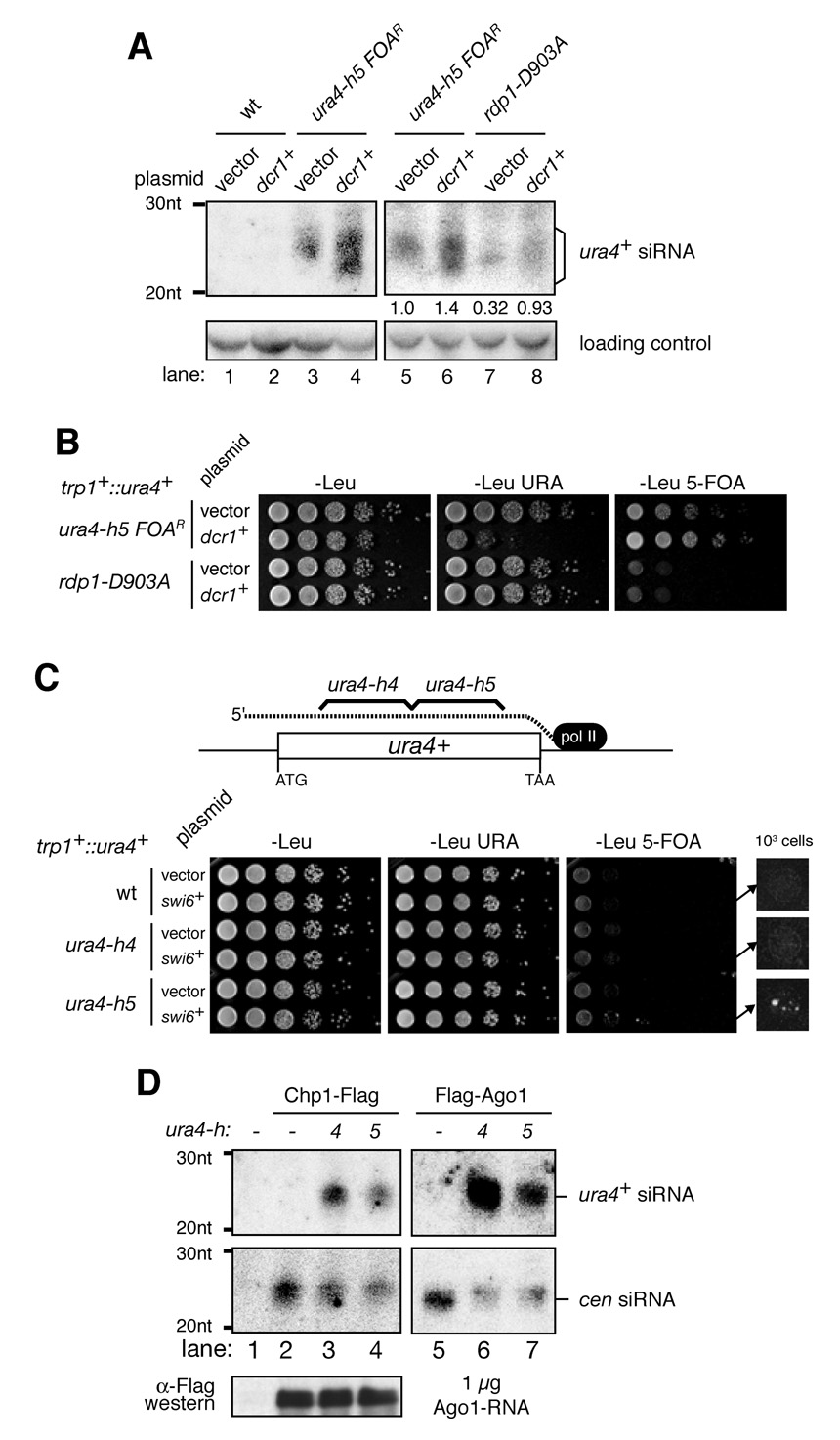

The requirement for Rdp1 and its activity in maintenance of hairpin-induced silencing may reflect a requirement for dsRNA synthesis or siRNA amplification at the target ura4+ locus. Alternatively, in rdp1 mutant cells the levels of hairpin siRNAs may be below a threshold level required for silencing. To help distinguish between these possibilities, we sought to increase hairpin siRNA levels in rdp1 mutant cells. We have previously shown that in fission yeast Dicer is physically and functionally linked to RDRC (Colmenares et al., 2007). We therefore reasoned that over-expression of Dcr1 in rdp1 mutant cells may promote an increase in siRNA levels. Consistent with this reasoning, we found that overexpression of Dcr1 resulted in a 1.4- to 2-fold increase in hairpin siRNA levels in wild-type cells, although the size range of the resulting siRNAs under conditions of Dcr1 overexpression was broader (Figure 6A, compare lanes 3 and 5 with lanes 4 and 6). Moreover, Dcr1 overexpression in rdp1-D903A mutant cells resulted in an increase in hairpin siRNAs to levels that were comparable to rdp1+ cells (Figure 6A, compare lanes 5 and 8). We used the above strains to determine whether Dcr1 overexpression circumvented the requirement for Rdp1 catalytic activity. As shown in Figure 6B, rdp1-D903A cells did not support hairpin-mediated silencing of trp1+::ura4+ even when Dcr1 was overexpressed. Importantly, we observed that Dcr1 overexpression resulted in an increase in hairpin-mediated silencing in rdp1+ cells, as evidenced by increased growth on 5-FOA and decreased growth on -URA medium, to levels that are comparable to the strongest heterochromatin-dependent silencing of this ura4+ reporter gene at the centromeric otr1R region (Figure 6B, see Figure 2A for comparison). These results provide further support for the idea that dsRNA synthesis at the target ura4+ locus plays an important role in RNAi-mediated heterochromatic silencing.

Figure 6. Rdp1 catalytic activity and location of siRNA target sequences control hairpin-induced silencing.

A, Overexpression of Dcr1 boosted hairpin siRNA levels in both rdp1+ and rdp1-D903A cells. B, Dcr1 overexpression did not circumvent the requirement for Rdp1 catalytic activity but increased the efficiency of hairpin-induced silencing of trp1+::ura4+ in rdp1+ cells. C, In contrast to the ura4-h5 hairpin, a ura4-h4 hairpin, which targets the 5’ half of the ura4+ transcript did not promote trp1+::ura4+ silencing. trp1+::ura4+ cells with ura4-h4 or -h5 were tested by Swi6 overexpression as described in Figure 3A. Diagram indicates the regions of ura4+ targeted by each hairpin. D, Northern blots of pull-down assays showing that siRNAs produced by both ura4-h4 and ura4-h5 were loaded onto Ago1 and the RITS complex. Centromeric (cen) siRNAs served as controls.

If dsRNA synthesis at the target locus were in fact required for heterochromatin assembly, we would expect that siRNAs that target the 3’ end of the ura4+ transcript would be more effective in inducing silencing than siRNAs targeting the 5’ end of the transcript. This is because siRNAs that target the 5’ end of the gene would only produce short dsRNA (Figure 6C, top). The ura4-h4 and -h5 constructs, which target the 5’ and 3’ halves of the ura4+, respectively (Figure 6C), generated similar levels of ura4+ siRNA as detected on total RNA northern blots (Figure 1 B). However, unlike ura4-h5 siRNAs, the equally abundant siRNAs produced by ura4-h4, which target the 5’ half of ura4+, did not mediate trp1+::ura4+ silencing in any of our experiments, even in combination with Swi6 overexpression (Figure 6C, data not shown). To rule out the possibility that ura4-h4 siRNAs may not load onto Ago1 and the RITS complex, we compared the levels of ura4-h4 and -h5 siRNAs in Chp1-FLAG and Flag-Ago1 pull-downs. We found that comparable levels of siRNAs from each hairpin were present in Chp1-FLAG and FLAG-Ago1 pull-downs (Figure 6D, compare lanes 3 with 4 and 6 with 7). It is possible that differences in RNA secondary structure at the 5’ and 3’ halves of the ura4+ target gene, or proximity to 3’-end processing signals, affect the ability of siRNAs to target the locus for silencing. However, together with the results on the requirement for Rdp1 catalytic activity (Figure 5, Figure 6A, and B), these observations support a specific role for RDRC-dependent dsRNA synthesis in RNAi-mediated chromatin silencing. In this model, siRNAs that target the 5’-end of ura4+ (Figure 6C) would mediate the RDRC-dependent synthesis of shorter chromatin-bound dsRNA fragments, which may be less efficient in recruitment of H3K9 methylation.

Discussion

The hairpin-induced silencing system presented here has provided insight into the interdependent relationship between siRNA biosynthesis and heterochromatin assembly mechanisms. First, expression of a long hairpin dsRNA bypasses the requirement for the coupling of siRNA generation to heterochromatin assembly, indicating that chromatin-dependent dsRNA synthesis may be the rate-limiting step in nuclear RNAi. Second, histone H3K9 methylation, antisense transcription at the target locus, and Swi6/HP1 availability greatly influence the ability of siRNAs to act in trans, restricting siRNA action to specific chromosome regions. Third, the requirement for RNA-dependent RNA polymerase dsRNA synthesis activity in hairpin-induced heterochromatin formation, but not hairpin-induced siRNA generation, suggests a role for cis-dsRNA synthesis or cis-siRNA amplification at target loci in heterochromatin assembly. Finally, the requirement for Swi6/HP1 in siRNA generation independently of H3K9 methylation indicates a more direct role for Swi6/HP1 in dsRNA/siRNA processing than previously suspected. Below, we discuss the implications of these finding for the mechanism of RNAi-mediated heterochromatin formation.

Role for antisense transcription and cis-synthesis of dsRNA in heterochromatin assembly

While HP1 overexpression ws required for hairpin-induced silencing of trp1+::ura4+ locus, the endogenous ura4+ locus was refractory to ura4-h5 hairpin silencing even when Swi6/HP1 was overexpressed. The ability of hairpin siRNAs to induce silencing at these ura4+ copies, which reside on different chromosomes, and at ura4+ copies inserted at the same location, the leu1+ locus, correlates with the occurrence of antisense transcription (Figure 4 and Figure S4). A recent study showed that readthrough transcription from some fission yeast convergent gene pairs produces antisense transcripts and results in transient heterochromatin formation in G1 phase of the cell cycle (Gullerova and Proudfoot, 2008). Such convergent transcription, which is also observed at centromeric DNA repeats, may induce chromatin changes that poise the trp1+::ura4+ and leu1Δ::ura4+/kanMX loci for hairpin-induced heterochromatin assembly. One possibility is that antisense transcription generates low levels of dsRNA that mediate H3K9 methylation. This may involve the processing of the dsRNA into siRNAs to trigger RNAi-dependent chromatin changes. Alternatively, the dsRNA may directly recruit the CLRC H3K9 methyltransferase complex and H3K9 methylation.

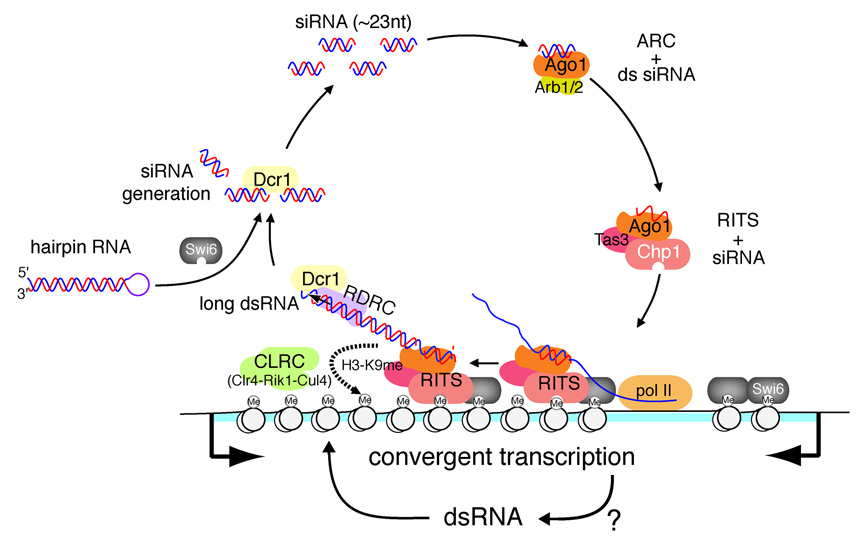

Additional support for a direct role for dsRNA in heterochromatin formation comes from the observation that RNA-dependent RNA polymerase activity is required for heterochromatin formation even when high levels of siRNA are generated in an Rdp1-independent manner (Figure 6). We propose that the synthesis of dsRNA at the target locus is required for heterochromatin assembly and enhancement of the RNAi-heterochromatin cycle (Figure 7). This model also provides a possible explanation for the inability of the ura4-h4 hairpin, which targets the 5’ half of the ura4+ transcript, to induce heterochromatin formation even though it produces siRNAs to the same level as the ura4-h5 hairpin, which targets the 3’ half of the ura4+ transcript (Figure 6C). The synthesis of long dsRNA at the target locus may promote a downstream event such as the recruitment of the CLRC methyltransferase complex (Figure 7). In this regard, we have previously noted that the CLRC complex is architecturally similar to the DDB DNA damage repair complex (Hong et al., 2005), which recognizes damaged DNA through its DDB1/DDB2 beta propeller subunits. The Rik1 subunit of CLRC shares extensive sequence similarity with DDB1 and other nucleic acid binding proteins such as the Cleavage Polyadenylation Selectivity Factor A (CPSF-A) and may directly recognize the dsRNA that is synthesized on chromatin. Additional contributions to CLRC recruitment may come from protein-protein interactions between subunits of the RITS (or RDRC) and the CLRC complex. Subunits of RITS and RDRC do in fact co-immunoprecipitate (Zhang et al., 2008; E. Hong and D.M., unpublished observations), although the possible dependence of this interaction on RNA has not been examined.

Figure 7. The nascent transcript model for the RNAi-heterochromatin cycle.

In fission yeast, heterochromatin assembly involves localization of the siRNA-amplification loop to specific chromosome regions. Nascent noncoding transcripts (blue) serve as platforms for the recruitment of siRNA-programmed RITS, which then recruits RDRC/Dicer and mediates siRNA amplification. RITS/RDRC and the resulting dsRNA recruit the CLRC H3K9 methyltransferase complex, thus coupling RNAi to heterochromatin assembly. Swi6/HP1 is required for RNAi-mediated silencing at a step subsequent to H3K9 methylation. siRNAs generated from long hairpin RNA (such ura4-h5 described here) can initiate de novo heterochromatin establishment at target loci that are associated with antisense transcription. siRNA generation from the hairpin bypasses the chromatin-dependent steps involving RDRC recruitment, but still requires Swi6, Dcr1, and ARC. Convergent transcription at the centromeric DNA repeats or other target loci (indicated by arrows below the diagram) may contribute to RNAi-mediated heterochromatin assembly by providing a susceptible chromatin environment or critical initial trigger such as H3K9 methylation.

Antisense transcription and dsRNA formation may play widespread roles in chromatin-dependent gene silencing. Antisense transcripts have been implicated in chromatin-silencing mechanisms in mammals, including imprinting of multiple genes, X-inactivation, and silencing of the p15 tumor suppressor gene (Yang and Kuroda, 2007; Yu et al., 2007). Moreover, in budding yeast, which lacks the RNAi system, antisense transcription regulates chromatin-dependent silencing of the PHO84 gene during chronological aging (Camblong et al., 2007), and a trans-acting noncoding antisense RNA has been implicated in transcriptional silencing of the Ty1 retrotransposons (Berretta et al., 2008). We propose that the formation of dsRNA on chromatin-associated transcripts may be a common molecular link between diverse RNA-dependent chromatin silencing mechanisms.

Small RNA molecules have been implicated in DNA methylation and chromatin changes in organisms ranging from plants to fission yeast to human (Kim et al., 2006; Janowski et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2007; Matzke and Birchler, 2005; Meister and Tuschl, 2004). While long hairpin RNAs can induce DNA methylation at homologous sequences in some plants (Mette et al., 2000), the ability of siRNAs to induce de novo DNA methylation in Arabidopsis is sensitive to the presence of pre-existing chromatin modifications (Chan et al., 2006). Furthermore, most siRNAs do not appear to induce chromatin modifications in animal cells. The role of chromatin structure and antisense transcription in controlling the ability of siRNAs to mediate chromatin-dependent gene silencing described here suggests that similar processes may be involved in regulation of RNAi-dependent chromatin silencing mechanisms in metazoans.

The role of Swi6 in RNAi-mediated heterochromatin formation

We have previously shown that Swi6 is required for efficient siRNA generation (Bühler et al., 2006; Motamedi et al., 2004), but it has been unclear how Swi6 affects siRNAs levels. Because the Clr4 H3K9 methyltransferase complex is also required for centromeric siRNA generation (Hong et al., 2005; Motamedi et al., 2004; Noma et al., 2004), we had initially proposed that the requirement for Swi6 is linked to its role in spreading and maintaining high levels of H3K9 methylation (Motamedi et al., 2004; Noma et al., 2004). However, more recent studies show that Swi6 is not required for H3K9 methylation within centromeric repeats or the spreading of H3K9 methylation into transgenes that are inserted into the repeats (Sadaie et al., 2004). The results presented in the current study suggest a more direct role for Swi6 in RNAi-mediated heterochromatin formation (Figure 7). First, Swi6 functions together with Dicer and the ARC complex in chromatin-independent processing of hairpin RNA into siRNAs. Second, Swi6 is required for the initial recruitment of the RNAi machinery to heterochromatin at a step following H3K9 methylation (Figure 7). In this regard, the ability of hairpin siRNAs to enhance the silencing of a centromeric ura4+ gene (imr1R::ura4+) is Swi6-dependent, even though Swi6 is not required for H3K9 methylation of this ura4+ insert (Sadaie et al., 2004)(T.I. and M. Motamedi, unpublished observations). The dependence of hairpin-induced heterochromatin formation on transient Swi6 overexpression further supports a role for Swi6 in initiation of RNAi-dependent heterochromatin formation. Finally, the ability of Swi6 to promote hairpin-induced trans-silencing requires its chromodomain, suggesting that Swi6 localizes to chromatin via association with H3K9 methylated nucleosomes and then helps recruit or stabilize the RNAi machinery.

The role of Swi6 in coupling of RNAi or RNA silencing mechanisms to chromosomes appears to be conserved in metazoans. In human cells, heterochromatin localization of HP1α is sensitive to ribonuclease treatment and requires the RNA binding ability of the hinge-domain of HP1α (Muchardt et al., 2002). In Drosophila, HP1 physically associates with Piwi, an Argonaute family protein that binds to repeat-associated small RNAs, and both proteins are required for heterochromatic gene silencing (Klenov et al., 2007; Pal-Bhadra et al., 2004). An attractive possibility is that the RNA-binding activity of HP1 proteins provides a bridge between heterochromatic domains and various RNA silencing pathways.

Experimental Procedures

Plasmids and yeast strains

Plasmid and yeast strain construction is described in the supplemental section. Plasmids and yeast strains are listed in Supplemental Table S3 and Table S1, respectively.

Synthetic oligos

Synthetic DNA oligos used in this study are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Chromatin immuneoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP analyses were performed as described previously (Sadaie et al., 2004) using antibodies against Swi6 (ab14898, Abcam); di-methylated H3K9 (ab1220, Abcam); pol II (8WG16, Covance). For PCR, synthetic oligo sets were used to amplify act1+ (prIT102/103); ura4+ (prIT72/49); ura4h-5 (prIT105/106); dg (prIT107/108). For ChIP analysis of 5-FOAR cells (swi6** in Figure 3b), 5-FOAR cells harboring swi6+ plasmid cells were grown in EMMC 5-FOA (0.05%) lacking leucine and subsequently in rich (YE supplement) media for three hour.

RNA analysis

Total RNA preparations were performed as described previously (Sadaie et al., 2004). Subsequent small RNA preparations were done with RNeasy midi kit (Qiagen) (Bühler et al., 2006). Ago1 associating RNAs were obtained by 3Flag-Ago1 purification (Bühler et al., 2007). Chp1-Flag RNAs were purified from Chp1-5FlagHis protein immunoprecipitates. Chp1-5FlagHis immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (Sadaie et al., 2004) using six-grams cells for each strain. Northern analyses were performed as described previously (Iida et al., 2006) using oligo probes for cen siRNA (Bühler et al., 2006), loading control (snoR69 (Bühler et al., 2006)) or ura4+ siRNA (prIT70-76 or prIT57-82 for Figure 1b). Semi-quantitative endpoint RT-PCR (Bühler et al., 2006) and quantitative real-time RT-PCR (Bühler et al., 2007) were performed as described previously. Primer pairs to transcripts were prIT72/49 (ura4+ or DW), prIT205/206 (real-time ura4+ or UP) prIT181/182 (act1+) and prIT207/208 (real-time act1+). For cDNA synthesis by reverse transcription (Figure S4), prIT49 (sense) and prIT205 (antisense) were used.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank M. Bühler for advice and plasmid construction, M. Motamedi and M. Sadaie for sharing unpublished results and advice, and members of our laboratories for discussion and help. T.I. is supported by a TOYOBO Biotechnology Foundation long-term fellowship. This work was supported by grants from the US National Institutes of Health (D.M.) and grants in-Aid from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (J.-I.N.). D.M. is a Scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allshire RC, Javerzat JP, Redhead NJ, Cranston G. Position effect variegation at fission yeast centromeres. Cell. 1994;76:157–169. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90180-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, Zegerman P, Partridge JF, Miska EA, Thomas JO, Allshire RC, Kouzarides T. Selective recognition of methylated lysine 9 on histone H3 by the HP1 chromo domain. Nature. 2001;410:120–124. doi: 10.1038/35065138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein E, Candy AA, Hammond SM, Hannon GJ. Role for a Biden Tate rib nuclease in the initiation step of RNA interference. Nature. 2001;409:363–366. doi: 10.1038/35053110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berretta J, Pinkeye M, Morrilton A. A cryptic unstable transcript mediates transcriptional trans-silencing of the Ty1 retrotransposon in S. cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 2008;22:615–626. doi: 10.1101/gad.458008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühler M, Haas W, Gygi SP, Moazed D. RNAi-dependent and -independent RNA turnover mechanisms contribute to heterochromatic gene silencing. Cell. 2007;129:707–721. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bühler M, Verdel A, Moazed D. Tethering RITS to a nascent transcript initiates RNAi- and heterochromatin-dependent gene silencing. Cell. 2006;125:873–886. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buker SM, Iida T, Bühler M, Villen J, Gygi SP, Nakayama J, Moazed D. Two different Argonaute complexes are required for siRNA generation and heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:200–207. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cam HP, Sugiyama T, Chen ES, Chen X, FitzGerald PC, Grewal SI. Comprehensive analysis of heterochromatin- and RNAi-mediated epigenetic control of the fission yeast genome. Nat Genet. 2005;37:809–819. doi: 10.1038/ng1602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camblong J, Iglesias N, Fickentscher C, Dieppois G, Stutz F. Antisense RNA stabilization induces transcriptional gene silencing via histone deacetylation in S. cerevisiae. Cell. 2007;131:706–717. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan SW, Zhang X, Bernatavichute YV, Jacobsen SE. Two-step recruitment of RNA-directed DNA methylation to tandem repeats. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e363. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colmenares SU, Buker SM, Bühler M, Dlakic M, Moazed D. Coupling of double-stranded RNA synthesis and siRNA generation in fission yeast RNAi. Mol Cell. 2007;27:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fire A, Xu S, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon M, Holt DG, Panigrahi A, Wilhelm BT, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Bahler J, Cairns BR. Genome-wide dynamics of SAPHIRE, an essential complex for gene activation and chromatin boundaries. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;277:4058–4069. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02044-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Chendrimada TP, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. Human RISC couples microRNA biogenesis and posttranscriptional gene silencing. Cell. 2005;123:631–640. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SI, Klar AJ. Chromosomal inheritance of epigenetic states in fission yeast during mitosis and meiosis. Cell. 1996;86:95–101. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80080-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grewal SI, Moazed D. Heterochromatin and epigenetic control of gene expression. Science. 2003;301:798–802. doi: 10.1126/science.1086887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullerova M, Proudfoot NJ. Coheisin Complex Promotes Transcriptional Termination between Convergent Genes in S. pombe. Cell. 2008;132:983–995. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammond SM, Boettcher S, Caudy AA, Kobayashi R, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2, a link between genetic and biochemical analyses of RNAi. Science. 2001;293:1146–1150. doi: 10.1126/science.1064023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannon GJ. RNA interference. Nature. 2002;418:244–251. doi: 10.1038/418244a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong EE, Villén J, Gerace EL, Gygi SP, Moazed D. A Cullin E3 Ubiquitin Ligase Complex Associates with Rik1 and the Clr4 Histone H3-K9 Methyltransferase and is Required for RNAi-Mediated Heterochromatin Formation. RNA Biology. 2005;2:106–111. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.3.2131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn PJ, Bastie JN, Peterson CL. A Rik1-associated, cullin-dependent E3 ubiquitin ligase is essential for heterochromatin formation. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1705–1714. doi: 10.1101/gad.1328005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutvagner G, Zamore PD. A microRNA in a multiple-turnover RNAi enzyme complex. Science. 2002;297:2056–2060. doi: 10.1126/science.1073827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iida T, Kawaguchi R, Nakayama J. Conserved ribonuclease, Eri1, negatively regulates heterochromatin assembly in fission yeast. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1459–1464. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.05.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs SA, Khorasanizadeh S. Structure of HP1 chromodomain bound to a lysine 9-methylated histone H3 tail. Science. 2002;295:2080–2083. doi: 10.1126/science.1069473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowski BA, Huffman KE, Schwartz JC, Ram R, Nordsell R, Shames DS, Minna JD, Corey DR. Involvement of AGO1 and AGO2 in mammalian transcriptional silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:787–792. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DH, Villeneuve LM, Morris KV, Rossi JJ. Argonaute-1 directs siRNA-mediated transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:793–797. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klenov MS, Lavrov SA, Stolyarenko AD, Ryazansky SS, Aravin AA, Tuschl T, Gvozdev VA. Repeat-associated siRNAs cause chromatin silencing of retrotransposons in the Drosophila melanogaster germline. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:5430–5438. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan F, Zaratiegui M, Villen J, Vaughn MW, Verdel A, Huarte M, Shi Y, Gygi SP, Moazed D, Martienssen RA, Shi Y. S. pombe LSD1 homologs regulate heterochromatin propagation and euchromatic gene transcription. Mol Cell. 2007;26:89–101. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song JJ, Hammond SM, Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305:1437–1441. doi: 10.1126/science.1102513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Taverna SD, Muratore TL, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Allis CD. RNAi-dependent H3K27 methylation is required for heterochromatin formation and DNA elimination in Tetrahymena. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1530–1545. doi: 10.1101/gad.1544207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martienssen RA, Zaratiegui M, Goto DB. RNA interference and heterochromatin in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Trends Genet. 2005;21:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzke MA, Birchler JA. RNAi-mediated pathways in the nucleus. Nat Rev Genet. 2005;6:24–35. doi: 10.1038/nrg1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meister G, Tuschl T. Mechanisms of gene silencing by double-stranded RNA. Nature. 2004;431:343–349. doi: 10.1038/nature02873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mette MF, Aufsatz W, van der Winden J, Matzke MA, Matzke AJ. Transcriptional silencing and promoter methylation triggered by double-stranded RNA. EMBO J. 2000;19:5194–5201. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.19.5194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motamedi MR, Verdel A, Colmenares SU, Gerber SA, Gygi SP, Moazed D. Two RNAi complexes, RITS and RDRC, physically interact and localize to noncoding centromeric RNAs. Cell. 2004;119:789–802. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muchardt C, Guilleme M, Seeler JS, Trouche D, Dejean A, Yaniv M. Coordinated methyl and RNA binding is required for heterochromatin localization of mammalian HP1alpha. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:975–981. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murakami H, Goto DB, Toda T, Chen ES, Grewal SI, Martienssen RA, Yanagida M. Ribonuclease activity of Dis3 is required for mitotic progression and provides a possible link between heterochromatin and kinetochore function. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e317. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama J, Klar AJ, Grewal SI. A chromodomain protein, Swi6, performs imprinting functions in fission yeast during mitosis and meiosis. Cell. 2000;101:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80840-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama J, Rice JC, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Grewal SI. Role of histone H3 lysine 9 methylation in epigenetic control of heterochromatin assembly. Science. 2001;292:110–113. doi: 10.1126/science.1060118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noma K, Sugiyama T, Cam H, Verdel A, Zofall M, Jia S, Moazed D, Grewal SI. RITS acts in cis to promote RNA interference-mediated transcriptional and post-transcriptional silencing. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1174–1180. doi: 10.1038/ng1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal-Bhadra M, Leibovitch BA, Gandhi SG, Rao M, Bhadra U, Birchler JA, Elgin SC. Heterochromatic silencing and HP1 localization in Drosophila are dependent on the RNAi machinery. Science. 2004;303:669–672. doi: 10.1126/science.1092653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge JF, Scott KS, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T, Allshire RC. cis-acting DNA from fission yeast centromeres mediates histone H3 methylation and recruitment of silencing factors and cohesin to an ectopic site. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1652–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01177-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Bartel DP. Small RNAs correspond to centromere heterochromatic repeats. Science. 2002;297:1831. doi: 10.1126/science.1077183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadaie M, Iida T, Urano T, Nakayama J. A chromodomain protein, Chp1, is required for the establishment of heterochromatin in fission yeast. EMBO J. 2004;23:3825–3835. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigova A, Rhind N, Zamore PD. A single Argonaute protein mediates both transcriptional and posttranscriptional silencing in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genes Dev. 2004;18:2359–2367. doi: 10.1101/gad.1218004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JJ, Liu J, Tolia NH, Schneiderman J, Smith SK, Martienssen RA, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. The crystal structure of the Argonaute2 PAZ domain reveals an RNA binding motif in RNAi effector complexes. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:1026–1032. doi: 10.1038/nsb1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T, Cam H, Verdel A, Moazed D, Grewal SI. RNA-dependent RNA polymerase is an essential component of a self-enforcing loop coupling heterochromatin assembly to siRNA production. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:152–157. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407641102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thon G, Verhein-Hansen J. Four chromo-domain proteins of Schizosaccharomyces pombe differentially repress transcription at various chromosomal locations. Genetics. 2000;155:551–568. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdel A, Jia S, Gerber S, Sugiyama T, Gygi S, Grewal SI, Moazed D. RNAi-mediated targeting of heterochromatin by the RITS complex. Science. 2004;303:672–676. doi: 10.1126/science.1093686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe TA, Kidner C, Hall IM, Teng G, Grewal SI, Martienssen RA. Regulation of heterochromatic silencing and histone H3 lysine-9 methylation by RNAi. Science. 2002;297:1833–1837. doi: 10.1126/science.1074973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang PK, Kuroda MI. Noncoding RNAs and intranuclear positioning in monoallelic gene expression. Cell. 2007;128:777–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu W, Gius D, Onyango P, Muldoon-Jacobs K, Karp J, Feinberg AP, Cui H. Epigenetic silencing of tumour suppressor gene p15 by its antisense RNA. Nature. 2008;451:202–206. doi: 10.1038/nature06468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Mosch K, Fischle W, Grewal SI. Roles of the Clr4 methyltransferase complex in nucleation, spreading and maintenance of heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15:381–388. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.