Abstract

Because of mechanisms of self-tolerance, many tumor-specific CD8 T cells exhibit low avidity for tumor antigens and would benefit from strategies that enhance their numbers and effector function. Here we demonstrate that the combined use of two different types of immune adjuvants, one that directly targets the CD8 cell, IL-2/anti-IL-2 mAb complexes, and one that targets the innate immune system, poly(I:C), can achieve this goal. Provision of IL-2/mAb complexes was found to enhance the activation and effector function of low-avidity tumor-specific T cells, yet this was insufficient to achieve tumor eradication. The addition of poly(I:C) further increased the accumulation of granzyme B-expressing effectors within the tumor and resulted in tumor eradication. This strategy presents many of the benefits of whole-body irradiation, including the provision of high levels of homeostatic cytokines, enhanced expansion of effector cells relative to regulatory T cells, and provision of inflammatory cytokines, and is therefore likely to serve as a strategy for both tumor vaccines and adoptive immunotherapy of cancer.

Keywords: CD8 T cells, cytokine complexes, interleukin-2, TLR, tumor immunity

Activation of T cells by chronically expressed tumor antigens results in tolerance through deletion, anergy, and immunoregulation (1–3). As a result, residual tumor-specific T cells are generally of low avidity or anergic (4, 5). A goal of cancer immunotherapy is to identify immune adjuvants that can activate and amplify these residual low-avidity tumor-reactive T cells. Recent studies have revealed that cytokines of the common γ chain receptor family, including IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, and IL-15, promote expansion and survival of CD8 T cells (6). Their receptor is composed of the common γ chain (CD132), the β chain (CD122) for IL-2 and IL-15, and a cytokine-specific receptor subunit, IL-2Rα (CD25), IL-4Rα (CD124), and IL-7Rα (CD127). Regulated expression of the specific receptor subunits by different T cell subsets determines which cytokines are used for survival and proliferation.

IL-2 is commonly used as an adjuvant in immunotherapy protocols (7). In addition to playing a critical role in survival of CD8 T cells, when presented at high levels to antigen-activated CD8 cells, IL-2 can also promote the induction of effector functions, such as granzyme B (gzmB) via STAT5 signaling, thereby functioning as a costimulatory molecule (8). However, controversy about the dual role of IL-2 in enhancing proliferation of both CD8 effector cells and CD4 regulatory T cells (Tregs), both of which express high levels of CD25, has raised some questions about the use of this cytokine in vivo (9). Recent studies have shown that the effect of the cytokine can be amplified and directed more specifically to CD8 cells rather than Tregs if IL-2 is complexed with the mAB S4B6 (10, 11). IL-15 bound to IL-15Rα, its natural “presenting” receptors, has been shown to have a similar effect on CD8 memory cells and tumor-infiltrated cells (12–14), and IL-7/anti-IL-7 mAb complexes have been found to induce expansion of both naïve and memory CD8 and CD4 T cells (15). In this study we assess the potential of cytokine complexes formed with mAb (IL-2c, IL-4c, and IL-7c) or cytokine receptor (IL-15c) to serve as adjuvants during activation of tumor-specific CD8 T cells in a spontaneous model of tumor formation.

Results

IL-2 and IL-15 Complexes Enhance Activation of Naïve CD8 T Cells by Cross-presented Tumor Antigen.

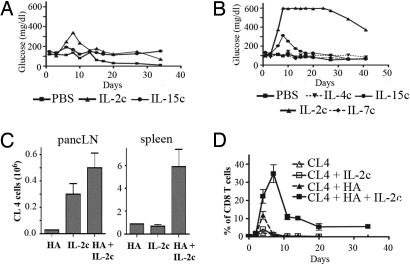

The various γc-cytokine complexes influence proliferation of different immune cell types. IL-2c and IL-15c preferentially affect memory CD8 T cells, natural killer cells, and CD11c+ cells (11, 12, 16), whereas IL-7c demonstrates its greatest effect on the numbers of B cells and macrophages [supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. To assess more specifically the influence of these cytokine complexes on differentiation of tumor-specific CD8 T cells, carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled Clone 4 (CL4) CD8 T cells that are specific for an H-2Kd restricted epitope of the influenza HA were transferred to 8–10-week-old RIP-Tag2-HA mice that spontaneously develop insulinomas expressing HA as a surrogate tumor antigen (17). By this age, many islets are either hyperplastic or transformed, and large quantities of tumor antigens are cross-presented in the pancreatic lymph nodes as evidenced by greatly increased levels of activation of HA-specific T cells in the lymph nodes draining the pancreas (17). The mice also received daily injections of γc-cytokine complexes on 3 consecutive days. HA antigen cross-presented in the draining pancreatic lymph nodes is sufficient to induce vigorous proliferation of CL4 cells (72% of divided cells at day 4; Fig. 1D) but poor differentiation into effectors (13% of IFNγ; Fig. 1D). The presence of IL-2c, IL-4c, and IL-15c increased the number of CL4 cells in pancreatic lymph nodes (Fig. 1A) as well as IFNγ production (Fig. 1B). However, only IL-2c and IL-15c induced production of gzmB, an important indicator of cytolytic effector function (Fig. 1B). In each case, the complexed forms of the cytokines were much more efficient than either cytokine or antibody alone in increasing proliferation (Fig. 1C) and effector function. In wild-type B10.D2 mice, the presence of IL-2c slightly increased IFNγ production (15.4% vs. 28.4%) and proliferation (8.1% vs. 33.3%) of the CL4 cells, but this effect was much more pronounced in RIP-Tag2-HA mice (Fig. 1D), indicating a requirement for antigen recognition.

Fig. 1.

Immune complexes enhance activation of naïve CD8 T cells by cross-presented tumor antigen. (A–C) 3 × 106 purified CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL4 cells were transferred i.v. into RIP-Tag2-HA B10D2 mice. On 3 consecutive days after cell transfer, mice received either PBS, immune complexes, antibody, or IL-15Rα-Fc alone, or cytokine alone. On day 4 after cell transfer mice were killed, and cells in the pancreatic lymph node cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Results in A and B represent the mean of two to three experiments with two to three mice per group. (A) The numbers of Thy1.1+ CD8+ cells in pancreatic lymph node are indicated. (B) Cells from the pancreatic lymph nodes were labeled with anti-gzmB antibody or incubated for 6 h with KdHA peptide and labeled with anti-IFNγ antibody. (C) Data represent the CFSE division profile of the CL4 cells. (D) RIP-Tag2-HA B10D2 mice or wild-type B10D2 mice (two to three mice per group) received 3 × 106 purified CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL4 cells. On 3 consecutive days after transfer mice received PBS or IL-2 complexes. Four days after cell transfer, cells from the pancreatic lymph nodes were isolated, stimulated with KdHA peptide for 6 h, and labeled with anti-IFNγ antibody.

IL-2c Treatment Induces Tumor Elimination by CL4 CD8 T Cells.

Effective immunotherapy in RIP-Tag2-HA mice through recognition of HA results in the destruction of transformed and normal β cells and is accompanied by the onset of hyperglycemia. Mice given CL4 and treated with IL-2c showed evidence of a slight and transient increase in blood glucose, corresponding to a weak response against the tumors (Fig. 2A). Because tumor antigen in these mice is available only in pancreatic lymph nodes, it was possible the antigen was limiting for optimal T cell activation. Soluble KdHA peptide was provided as a systemic source of antigen. In the presence of IL-2c, KdHA peptide only slightly increased the number of CL4 cells in pancreatic lymph nodes (Fig. 2C), but it greatly increased the number of cells activated in the spleen or in peripheral blood where antigen was not previously available (Fig. 2 C and D). The numbers of highly divided CL4 cells with an effector phenotype (IFNγ+, CD25+, and CD62Llo) were also increased (Fig. 2C and Fig. S2A), which resulted in sustained hyperglycemia (Fig. 2B). In contrast, treatment with IL-2c, IL-4c, and IL-7c had no effect on tumor elimination, and IL-15c produced a transient response.

Fig. 2.

Vaccination with HA peptide and IL-2c results in the elimination of HA-expressing tumors by CL4 cells. Purified CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL4 cells (3 × 106) were transferred i.v. into 9-week-old RIP-Tag2-HA mice. In B, and where indicated (HA), mice received 10 μg of KdHA peptide the next day. Cytokine complexes were delivered as described in Materials and Methods. (A and B) Data represent the mean of the blood glucose levels of the treated mice (two to three mice per group) and is representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Mice were killed on day 4 after cell transfer. Numbers of Thy1.1+ cells in the pancreatic lymph nodes or spleen are shown. (D) Percentage of CL4 cells among blood CD8 T cells was determined one to two times per week. This represents the mean of two independent experiments with four mice per condition.

Peptide Vaccination, IL-2c, and Poly(I:C) Induce Tumor Elimination by Low-Affinity CL1 Cells.

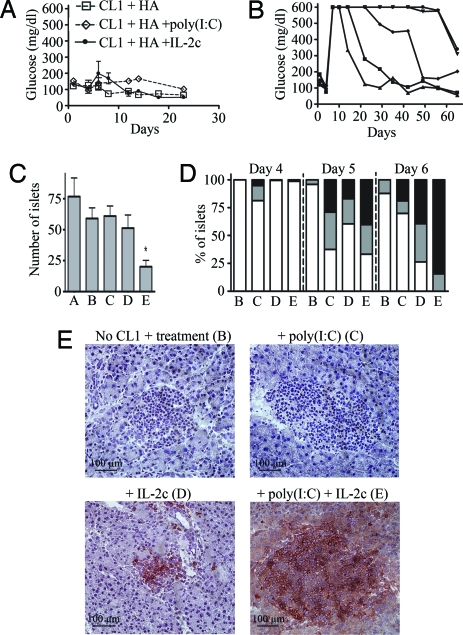

Clone 1 (CL1) CD8 T cells are also HA specific, but the T cell receptor (TCR) expressed by these cells was originally isolated from a mouse expressing HA in the pancreas and exhibits low affinity for HA (3). It would be expected that such low-avidity CD8 cells would more closely reflect what is available for tumor eradication in the endogenous repertoire. To monitor the effect of IL-2c on low-avidity CD8 T cells, purified CL1 CD8 T cells were transferred into RIP-Tag2-HA mice along with KdHA peptide and either IL-2c or PBS. In contrast to the successful tumor eradication obtained when CL4 was provided with peptide and IL-2c, CL1 cells caused much less tumor destruction and no elevation in blood glucose (Fig. 3A). Examination of the pancreas revealed that although a high percentage of both the transformed and normal islets were infiltrated by CL1 cells at 6 days after transfer (74%; Fig. 3D and data not shown), this resulted in only a slight decrease in the numbers of surviving islets as compared with untreated mice (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 3.

Tumor eradication by low-avidity CL1 cells after vaccination with IL-2c and poly(I:C). Purified Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL1 cells (3 × 106) were transferred i.v. into 9-week-old mice. One day after transfer, three mice per condition received 10 μg of KdHA (HA) peptide and the indicated treatment (A: untreated RIP-Tag2-HA mice; B: no CL1 cells, HA + IL-2c + poly(IC); C: HA + poly(I:C); D: HA + IL-2c; E: HA + poly(I:C) + IL-2c). (A) Mean of the blood glucose level from three mice per condition. (B) Blood glucose level of five individual RIP-Tag2HA mice that received HA peptide, IL-2 complexes, and poly(I:C). Results are representative of at least three independent experiments with similar results. On days 4, 5, and 6 after cell transfer, pancreata were harvested and frozen. (C) Average numbers of islets per section of pancreas at day 6 after transfer. P values of E vs. all other treatment were calculated using a paired Student's t test, and P < 0.05 is indicated with an asterisk (*). (D) Sections were stained with anti-Thy1.1 and anti-CD8 antibodies. Comparable results were obtained when cells were stained with either anti-CD8 or anti-Thy1.1. Percentage of islets that are noninfiltrated (white), mildly infiltrated (gray), or strongly infiltrated (black) by CD8 T cells is indicated. (E) Representative islets labeled with anti-CD8 are shown. (C and D) Data represent the mean from two independent experiments with four to nine mice per condition.

Poly(I:C) is a Toll-like receptor 3 agonist commonly used as an adjuvant in vaccination protocols (18). It induces the secretion of type 1 IFNs and proinflammatory cytokines and the maturation of dendritic cells, all of which promotes CD8 T cell activation and survival (19, 20). To determine whether provision of poly(I:C) could promote tumor eradication by CL1 cells, mice received poly(I:C) along with HA peptide. No significant tumor elimination was detected (Fig. 3 A and C), although more than 50% of the islets were infiltrated by CL1 cells at day 5 (Fig. 3D). In contrast, the combination of IL-2c and poly(I:C) resulted in effective tumor eradication, as indicated by the elevation in blood glucose (Fig. 3B), a significant decrease in the numbers of pancreatic islets (Fig. 3C), and the massive infiltration of essentially 100% of islets at day 6 (Fig. 3 D and E). This same treatment had little effect in the absence of CL1 cells (Fig. 3 C-E and data not shown).

Treatment with Poly(I:C) and IL-2c Results in Increased Numbers of CL1 Cells.

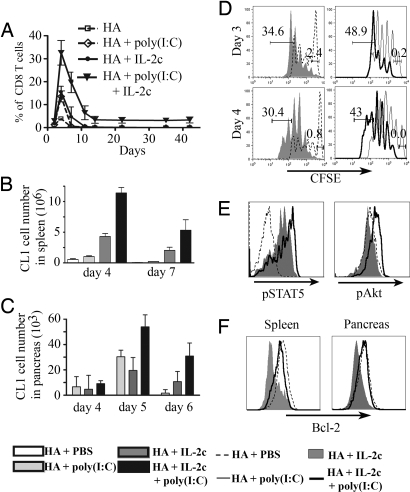

To understand how the combination of poly(I:C) and IL-2c resulted in tumor eradication, we first assessed the numbers of CL1 cells present in different compartments. Treatment with IL-2c or poly(I:C) resulted in similar numbers of CL1 cells in the blood, where they reached a maximum of 15% of CD8 T cells at day 4, followed by a rapid decrease in number, and were undetectable by day 10 (Fig. 4A). This was less than CL4, which under similar conditions accumulated to 35.5% of total CD8 cells (Fig. 2D). By combining poly(I:C) and IL-2c, CL1 cells reached a maximum of 32% of the total CD8 cells at day 4 and were still present 6 weeks after transfer (Fig. 4A). A similar increase of CL1 cell numbers was observed in the spleen, where 12.3 × 106 cells were recovered on day 4 from mice treated with both IL-2c and poly(I:C), as compared with 4.8 × 106 and 1.2 × 106 cells after injection of IL-2c or poly(I:C), respectively (Fig. 4B). A similar pattern was also observed for CL1 cells recovered from the pancreas (Fig. 4C). Of interest, despite an increase in the percentage of islets that were infiltrated between days 5 and 6 (Fig. 3D), the numbers of CL1 cells recovered from the pancreas at day 6 were reduced relative to day 5 (Fig. 4C). Presumably this is because most islets in mice treated with IL-2c and poly(I:C) were fully destroyed by day 6 (Fig. 3C).

Fig. 4.

Poly(I:C) synergizes with IL-2c to increase expansion of CL1 cells. Purified CFSE-labeled Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL1 cells (3 × 106) were transferred i.v. into 8- to 9-week-old RIP-Tag2-HA mice. Starting 1 day after transfer, mice received 10 μg of KdHA peptide and either PBS, poly(I:C), IL-2c, or poly(I:C) plus IL-2c, for 3 consecutive days. (A) Percentage of CL1 cells among blood CD8 T cells was determined one to two times per week. (B and C) At the indicated day after cell transfer spleen cells (B) and cells from the pancreata (C) were isolated and labeled with anti-CD8 and Thy1.1 antibodies. The mean numbers of CL1 cells from three independent experiments are indicated. (D) Histograms represent dilution of CFSE in CL1 cells at day 4 after transfer. Numbers represent the percentage of cells divided five times or more. (E) Twenty minutes after the third injection with poly(I:C) and IL-2c (day 3 after transfer), mice were killed and spleen cells were labeled with anti-CD8, anti-Thy1.1, and anti-phospho antibodies specific for either STAT5 or AKT. (F) At day 7 after cell transfer, the level of Bcl-2 in CL1 cells from the spleen or from the pancreas was assessed by flow cytometry. Each figure is representative of at least two independent experiments with similar results.

Increased Proliferation and Survival of CL1 Cells After Treatment with Poly(I:C) and IL-2c.

Increased proliferation and/or survival could explain the higher number of CL1 cells. To assess the rate of division, CFSE-labeled CL1 cells were compared after stimulation with peptide and either IL-2c or both IL-2c and poly(I:C) (Fig. 4D). Although we saw no difference in the numbers of divisions, the combined treatment resulted in fewer undivided cells at day 3 (Fig. 4D) and a slight but consistent increase in the accumulation of highly divided cells at day 4 (43% compared with 30.4% with IL-2c alone; Fig. 4D). In agreement with the relatively smaller increase in numbers of CL1 cells in the spleen after treatment with poly(I:C) (Fig. 4B), only 9.4% of the cells reached the fifth division at day 4 after poly(I:C) treatment alone (data not shown).

In the experiments described above, IL-2c was provided for 3 days, after which CD8 cells become susceptible to death induced by cytokine withdrawal (21). To evaluate effects of the various treatments on CL1 survival, we first checked activation of the AKT signaling pathway (also known as PKB) that is directly associated with enhanced T cell survival after exposure to inflammatory adjuvants (22) and is reduced as a consequence of cytokine withdrawal (21). Phosphorylation of AKT was not detectable in CL1 cells taken from the spleen 3 days after exposure to peptide and IL-2c (Fig. 4E). However, provision of both poly(I:C) and IL-2c resulted in a clear shift in AKT phosphorylation.

Because AKT signaling is involved in regulating the expression of Bcl-2 family members through NF-κB activation (23–26), we next assessed the impact of the different treatments on the amount of Bcl-2 in CL1 cells retrieved from spleen and tumor infiltrate at day 7. Compared with the level of Bcl-2 expressed in naïve endogenous cells, Bcl-2 was clearly reduced in CL1 cells taken from the spleen and inside the tumors of mice that received IL-2c (Fig. 4F). The level of Bcl-2 remained high after activation of CL1 cells in mice receiving both poly(I:C) and IL-2c.

Collectively, these results suggest that both increased activation and better survival of highly divided cells account for the increased accumulation of CL1 cells obtained after combined treatment with peptide, IL-2c, and poly(I:C).

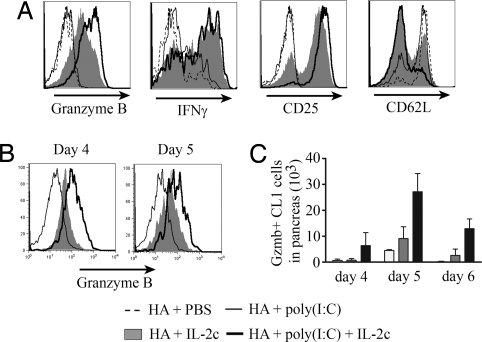

The Combination of Poly(I:C) and IL-2c Increases the Number of gzmB-Expressing CL1 Cells.

Increased tumor eradication associated with provision of IL-2c and poly(I:C) may also be associated with changes in the differentiation status of the CL1 cells. To explore this possibility, we assessed the development of effector function in CL1 cells stimulated with the various reagents. In the spleen, the production of IFNγ by CL1 cells was greatly increased by IL-2c but not by poly(I:C), and no further increase occurred with the combination of IL-2c and poly(I:C) (Fig. 5A). The combination did result in a further increase in the levels of gzmB and CD25, and a higher percentage of cells downregulated CD62L (Fig. 5A). This correlated with a higher phosphorylation of STAT5 (Fig. 4E and Fig. S2B), which regulates gzmB expression (8).

Fig. 5.

Poly(I:C) synergizes with IL-2c to increase gzmB expression in CL1 cells. Purified Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL1 cells (3 × 106) were transferred i.v. into 8- to 9-week-old RIP-Tag2-HA mice. One day after transfer, mice received 10 μg of KdHA peptide and were given either PBS, poly(I:C), IL-2c, or poly(I:C) and IL-2c on 3 consecutive days. (A) At day 4 after cell transfer, Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL1 cells from the spleen were directly labeled with anti-gzmB, CD25, and CD62L antibodies or reactivated for 6 h with KdHA peptide for 6 h and labeled with anti-IFNγ antibodies. At day 4, 5, and 6 Thy1.1+ CD8+ CL1 cells from pancreas were isolated and directly labeled with anti-gzmB. Level of expression at day 4 and 5 (B) and total number of gzmB+ CL1 cells (C) are represented.

The level of gzmB expression was also assessed in CL1 cells recovered from tumor infiltrates. Individually, poly(I:C) and IL-2c promoted low and intermediate expression of gzmB, respectively (Fig. 5B). When provided with both reagents, the level of gzmB expression was enhanced, and the number of CL1 cells inside the pancreas expressing gzmB was increased by threefold at day 5 and by fivefold at day 6, above that seen with either reagent alone (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

Although cytokines of the common γ chain family are generally associated with regulating homeostasis and survival of CD8 T cells (27, 28), recent studies have demonstrated that the presence of high levels of IL-2 also costimulates CD8 effector functions (29, 30). This result is particularly dramatic when CD8 cells are of low avidity for antigen, because the presence of constitutively activated STAT5 can complement weak TCR signaling in transcriptional regulation of numerous effector functions, including expression of gzmB (29). As described previously (10, 12), effects on CD8 T cells are greatly augmented when cytokine is complexed with mAb. Provision of comparable amounts of IL-2 in complexed form results in greatly enhanced activation of STAT5, enhanced proliferation, and effector function. Cytokines alone did not increase proliferation (Fig. 1C) or effector functions (data not shown). Interleukins have a very short half-life in vivo, and therefore one explanation for the higher efficiency of the immune complexes is that antibodies stabilize and increase the half-life of the cytokines (31), although additional mechanisms have not been ruled out.

Consistent with the results reported by Boyman et al. in their studies of polyclonal CD8 T cells (10), we found only low levels of proliferation and differentiation of naïve CD8 cells when IL-2c was provided in the absence of cognate antigen (Fig. 1D). They found that IL-2c only slightly increased proliferation of naïve CD8 T cells, but greatly enhanced proliferation of CD44hi CD8 T cells that express a high level of CD122. In contrast, using ovalbumin-specific OT-1 CD8 T cells, Kamimura et al. (32) reported that IL-2c is sufficient to drive proliferation of naïve cells and to promote their differentiation into memory-like cells. Therefore, CL4 and CL1 cells behave more like endogenous naïve cells that require cognate antigen to proliferate extensively in the presence of IL-2c (Fig. 1D and data not shown). These discrepancies could be explained by a difference in TCR affinity for endogenous self-peptide, which was found previously to regulate the extent of homeostatic proliferation (33).

It is of interest to contrast the effects that the different cytokine complexes had on newly activated CD8 cells. IL-2c, and to a lesser extend IL-15c, induced proliferation and IFNγ and gzmB production. IL-7c showed little effect, which may be explained by the fact that upon stimulation with cognate antigen IL-7Rα expression decreases dramatically (34). IL-4c increased both proliferation and IFNγ production but did not increase the level of gzmB in CL4 cells. Given that IL-4 predominantly activates STAT6 (35, 36), this suggests that STAT5 but not STAT6 regulates gzmB expression. Importantly, tumor elimination in the RIP-Tag2HA model correlated with the capacity of the complexes to induce production of gzmB. After peptide vaccination, IL-2c and IL-15c, but not IL-7c or IL-4c, were able to induce tumor elimination. However, when delivered in vivo at similar concentrations, the response induced by IL-15c was transient.

Although provision of IL-2c was able to enhance the numbers of highly activated CL4 effectors in the tumor-draining lymph nodes, this was found to be insufficient for tumor eradication. Both the numbers of effector cells and tumor destruction were enhanced by increasing antigen availability through provision of peptide antigen. Thus, when supplemented with IL-2c, the major limitation on tumor eradication by high-affinity CL4 cells is the availability of antigen. Still a greater challenge was faced when we attempted to use low-affinity CL1 cells for tumor eradication. Although provision of peptide and IL-2c proved successful in promoting large numbers of highly activated CL1 effectors, this was not sufficient to achieve a measurable antitumor response (Fig. 4A). A comparison of the numbers of CL4 and CL1 cells in the blood after treatment with peptide and IL-2c revealed that although there were only twofold fewer CL1 cells at the peak of the response (Figs. 2D and 4A), the CL1 cells disappeared very rapidly. In an attempt to increase the antitumor response by CL1 cells, mice were treated with poly(I:C) in addition to IL-2c (37, 38). This successfully induced the eradication of the tumors (Fig. 4 B and C) and was associated with increased accumulation of CL1 cells in blood, spleen, and tumor infiltrates (Fig. 4). The addition of poly(I:C) did not seem to have a strong impact on CL1 proliferation beyond that observed with IL-2c alone, and therefore proliferation alone is unlikely to explain the very large difference in numbers of CL1 cells. Further examination suggested that in combination with IL-2c, poly(I:C) also enhanced CL1 survival. Although neither IL-2c nor poly(I:C) alone increased phosphorylation of AKT, synergy between IL-2c and poly(I:C) induced AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 4E and data not shown) and resulted in higher expression of Bcl-2 in CL1 cells recovered from the spleen and the pancreas 7 days after stimulation (Fig. 4 E and F). These data are consistent with studies showing that survival of activated T cells can be increased by exposure to inflammatory adjuvants (22). AKT activation also prevents Bim upregulation and inhibits the proapoptotic BH3-only protein BAD (39, 40). It should be noted that attempts to detect differences in apoptosis of CL1 cells under the different treatment regimens by annexin V staining were unsuccessful. However, this may be due to the rapid clearance of apoptotic cells by monocytes that normally occurs in vivo (41).

In addition to increasing accumulation of CL1 cells, the combination of IL-2c and poly(I:C) also increased expression of gzmB. This is likely due to enhanced activation of STAT5 (Fig. 4E). The combined result of increased accumulation and increased expression of gzmB resulted in a fivefold increase in the number of gzmB+ CL1 cells within the tumor at day 6, as compared with either reagent alone, and result in eradication of the majority of both transformed and normal islets (Fig. 3C)

It should be noted that combined adjuvant treatment in the absence of transferred tumor-specific CD8 cells was not sufficient to induce significant tumor infiltration (Fig. 3 C and D). This suggests that endogenous HA-specific CD8+ T cells have little impact on the tumor under these conditions. This may be due to their low numbers. Future studies will attempt to optimize accumulation and effector function by endogenous C8 T cells.

In summary, we have identified a powerful combination of adjuvants, cytokine complexes and poly(I:C), which synergize to promote proliferation, differentiation, and survival of low-avidity tumor-specific CD8 T cells. We hypothesize that this combination of adjuvants may safely mimic the benefits to adoptive immunotherapy that are achieved by whole-body irradiation, whereby endogenous cytokines, removal of Tregs, and the release of TLR ligands from the gut play an important role in augmenting the activity of transferred CD8 T cells (42). Further studies are still necessary to fully understand the basis for the synergistic effects of IL-2c and poly(I:C), but once optimized, this type of combination of adjuvants may prove beneficial in both therapeutic vaccination protocols and adoptive immunotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

CL4 (43) and CL1 (3) TCR transgenic mice express a TCR specific for the HA518–526 epitope restricted by MHC class I H-2Kd. The RIP-Tag2-HA line was generated by crossing RIP-Tag2 mice with InsHA mice, as previously described (17). C57BL/6 Bim-/- mice were kindly provided by Dr. Douglas Green (La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology). Bim-/-, CL1 TCR, CL4 TCR, and RIP-Tag2-HA mice were each back-crossed with B10.D2 mice for more than eight generations. All RIP-Tag2-HA animals used in experiments were Tag2+/- and HA+/-. All animals were housed at The Scripps Research Institute animal facility, and all procedures were performed according to the National Institutes of Health's Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Preparation and Adoptive Transfer of Naive TCR Transgenic T Cells.

CD8+ T cells were isolated from the lymph nodes of CL1 or CL4 TCR mice (ages 6–8 weeks) by negative selection using the MACS CD8+ T cell isolation kit (Miltenyi Biotec). T cell purity was >85% with no contaminating CD4+ cells. Where indicated, purified CL1 or CL4 CD8+ T cells were labeled with CFSE (Molecular Probes) by incubation in 5 μM CFSE in HBSS for 10 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed and resuspended in cold HBSS before adoptive transfer. For adoptive transfer experiments, the indicated number of cells was injected i.v. in a volume of 100 μl of HBSS.

Preparation and Administration of Cytokine Complexes and Poly(I:C).

Recombinant mouse (rm)IL-2, rmIL-4, rmIL-7, and rmIL-15 were purchased from eBioscience and stored according to manufacturer's recommendations. Anti-IL-4 antibody (11B11) was obtained from the National Cancer Institute Biological Resources Branch Preclinical Repository. The S4B6.1 hybridoma (rat IgG2a antimouse IL-2) and M25 hybridoma (mouse IgG2b antihuman IL-7) were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and cultured in vitro under standard conditions, as described previously (10). RmIL-15Rα/Fc Chimera was obtained from R&D Systems. Daily i.p. injections of the various complexes contained 2 μg IL-2 + 10 μg S4B6, 2 μg IL-4 + 10 μg 11B11, 1.5 μg IL-7 + 7.5 μg M25, or 1.5 μg IL-15 + 7.5 μg IL-15R-Fc in 400 μl of HBSS. The same indicated amounts of cytokine or antibody alone were used as controls. When indicated, mice were injected i.p. with 200 μg of poly(I:C) (Amersham Biosciences).

Preparation of Islets Cells from the Pancreas.

Islets were isolated as previously described (44). Briefly, pancreata were cut into small pieces using fine scissors and digested in 2 mg/ml collagenase P (Roche Diagnostics) and 2 μg/ml DNase I (Roche Diagnostics) at 37°C for 20 min. The islets were then purified by centrifugation on Ficoll gradient (Histopaque-1077; Sigma–Aldrich). To obtain single cells, islets were dissociated using a nonenzymatic dissociation solution (Sigma–Aldrich).

Flow Cytometry.

Suspensions of spleen or pancreatic lymph node cells were stained for FACS analysis in HBSS containing 1% FCS and 2 mM EDTA with the following mAbs (from BD Biosciences unless otherwise stated): conjugated CD8α (53–6.7), allophycocyanin (APC)-conjugated CD25 (PC61.5), APC-conjugated CD62L (MEL-14), conjugated Thy1.1 (OX-7), and phycoerythrin (PE)-conjugated CD122 (5H4; eBioscience).

Intracellular Cytokine Staining.

To assess the ex vivo production of IFN-γ in response to antigen, cells from pancreatic lymph nodes or spleens were incubated in complete media with 1 μg/ml of the Kd-HA peptide (IYSTVASSL) and 1 μl/ml GolgiPlug solution (BD Biosciences) for 5 h at 37°C. PerCP-conjugated anti-CD8 and PE- or APC-conjugated anti-Thy1.1 were added, and cells were incubated for an additional 30 min at 4°C. Intracellular Bcl-2, IFN-γ (BD Biosciences), and gzmB (Caltag Laboratories) staining were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions using the Cytofix/Cytoperm Plus kit (BD Biosciences). Cells were analyzed on a BD Biosciences FACSCalibur flow cytometer, and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Inc.).

Phospho-Specific Intracellular Staining.

Cells were stained directly ex vivo to assess STAT3, STAT5, or AKT. Twenty to thirty minutes after injection of cytokine complexes or HBSS, mice were killed and spleen were disrupted and fixed in ice-cold 1.6% paraformaldehyde for 15 min. Cells were permeabilized with 90% methanol and stored at −20°C. Cells were labeled with anti-CD8, anti-Thy1.1, and anti-phospho antibodies specific for STAT3, STAT5 (BD Biosciences), or AKT (Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h in FACS buffer (HBSS, 1% FCS, 0.1 mM EDTA).

Assessment of Tumor Growth/Eradication by Blood Glucose Monitoring.

Mice were assessed for tumor growth (hypoglycemia) or tumor destruction (hyperglycemia) by weekly/biweekly monitoring of blood glucose using AccuCheck test strips (Roche). Reading range is between 10 and 600 mg/dl.

Histology.

Pancreatic tissue was embedded and frozen in Tissue-Tek OCT Compound (Sakura Finetek), and samples were stored at −70°C. Frozen sections (5 μM) were cut with a microtome and allowed to dry at room temperature. Sections were then fixed in cold 1% paraformaldehyde and washed with PBS. Blocking was performed with the avidin-biotin blocking kit (Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Sections were then incubated at room temperature with purified primary mAb to mouse CD8 (clone 53.6.7; BD Biosciences) or Thy1.1 (COX-7; BD Biosciences). After washing in PBS, biotin-SP-Affinipure F(ab′)2 mouse antirat IgG secondary Ab (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) was added. After washing in PBS, sections were incubated with peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) and then developed with a 3-amino-9-ethylcarbazole peroxidase substrate kit (Vector Laboratories).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank J. Biggs and D. Kim for technical assistance. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 CA057855 (to L.S).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0805054105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Bogen B. Peripheral T cell tolerance as a tumor escape mechanism: Deletion of CD4+ T cells specific for a monoclonal immunoglobulin idiotype secreted by a plasmacytoma. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:2671–2679. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830261119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Staveley-O'Carroll K, et al. Induction of antigen-specific T cell anergy: An early event in the course of tumor progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1178–1183. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyman MA, et al. The fate of low affinity tumor-specific CD8+ T cells in tumor-bearing mice. J Immunol. 2005;174:2563–2572. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guilloux Y, et al. Defective lymphokine production by most CD8+ and CD4+ tumor-specific T cell clones derived from human melanoma-infiltrating lymphocytes in response to autologous tumor cells in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:1966–1973. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez J, Lee PP, Davis MM, Sherman LA. The use of HLA A2.1/p53 peptide tetramers to visualize the impact of self tolerance on the TCR repertoire. J Immunol. 2000;164:596–602. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gattinoni L, et al. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rosenberg SA, et al. Impact of cytokine administration on the generation of antitumor reactivity in patients with metastatic melanoma receiving a peptide vaccine. J Immunol. 1999;163:1690–1695. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Verdeil G, Puthier D, Nguyen C, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Auphan-Anezin N. STAT5-mediated signals sustain a TCR-initiated gene expression program toward differentiation of CD8 T cell effectors. J Immunol. 2006;176:4834–4842. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Malek TR, Bayer AL. Tolerance, not immunity, crucially depends on IL-2. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:665–674. doi: 10.1038/nri1435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boyman O, Kovar M, Rubinstein MP, Surh CD, Sprent J. Selective stimulation of T cell subsets with antibody-cytokine immune complexes. Science. 2006;311:1924–1927. doi: 10.1126/science.1122927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamimura D, et al. IL-2 in vivo activities and antitumor efficacy enhanced by an anti-IL-2 mAb. J Immunol. 2006;177:306–314. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.1.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rubinstein MP, et al. Converting IL-15 to a superagonist by binding to soluble IL-15R{alpha} Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:9166–9171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600240103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stoklasek TA, Schluns KS, Lefrancois L. Combined IL-15/IL-15Ralpha immunotherapy maximizes IL-15 activity in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:6072–6080. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epardaud M, et al. Interleukin-15/interleukin-15R alpha complexes promote destruction of established tumors by reviving tumor-resident CD8+ T cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2972–2983. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyman O, Ramsey C, Kim DM, Sprent J, Surh CD. IL-7/anti-IL7 mAb complexes restore T cell development and induce homeostatic T cell expansion without lymphopenia. J Immunol. 2008;180:7265–7275. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.11.7265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin GH, Hirano T, Murakami M. Combination treatment with IL-2 and anti-IL-2 mAbs reduces tumor metastasis via NK cell activation. Int Immunol. 2008;20:783–789. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lyman MA, Aung S, Biggs JA, Sherman LA. A spontaneously arising pancreatic tumor does not promote the differentiation of naive CD8+ T lymphocytes into effector CTL. J Immunol. 2004;172:6558–6567. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Salem ML, Kadima AN, Cole DJ, Gillanders WE. Defining the antigen-specific T-cell response to vaccination and poly(I:C)/TLR3 signaling: Evidence of enhanced primary and memory CD8 T-cell responses and antitumor immunity. J Immunother. 2005;28:220–228. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000156828.75196.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kumar H, Koyama S, Ishii KJ, Kawai T, Akira S. Cutting edge: Cooperation of IPS-1- and TRIF-dependent pathways in poly IC-enhanced antibody production and cytotoxic T cell responses. J Immunol. 2008;180:683–687. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Durand V, Wong SY, Tough DF, Le Bon A. Shaping of adaptive immune responses to soluble proteins by TLR agonists: a role for IFN-alpha/beta. Immunol Cell Biol. 2004;82:596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.0818-9641.2004.01285.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hacker G, Bauer A, Villunger A. Apoptosis in activated T cells: What are the triggers, and what the signal transducers? Cell Cycle. 2006;5:2421–2424. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.21.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sengupta S, Chilton PM, Mitchell TC. Adjuvant-induced survival signaling in clonally expanded T cells is associated with transient increases in pAkt levels and sustained uptake of glucose. Immunobiology. 2005;210:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ozes ON, et al. NF-kappaB activation by tumour necrosis factor requires the Akt serine-threonine kinase. Nature. 1999;401:82–85. doi: 10.1038/43466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones RG, et al. Protein kinase B regulates T lymphocyte survival, nuclear factor kappaB activation, and Bcl-X(L) levels in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1721–1734. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.10.1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khoshnan A, et al. The NF-kappa B cascade is important in Bcl-xL expression and for the anti-apoptotic effects of the CD28 receptor in primary human CD4+ lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2000;165:1743–1754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoo JK, Cho JH, Lee SW, Sung YC. IL-12 provides proliferation and survival signals to murine CD4+ T cells through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2002;169:3637–3643. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boyman O, Purton JF, Surh CD, Sprent J. Cytokines and T-cell homeostasis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2007;19:320–326. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2007.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marrack P, et al. Homeostasis of alpha beta TCR+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:107–111. doi: 10.1038/77778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verdeil G, Chaix J, Schmitt-Verhulst AM, Auphan-Anezin N. Temporal cross-talk between TCR and STAT signals for CD8 T cell effector differentiation. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36:3090–3100. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janas ML, Groves P, Kienzle N, Kelso A. IL-2 regulates perforin and granzyme gene expression in CD8+ T cells independently of its effects on survival and proliferation. J Immunol. 2005;175:8003–8010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.12.8003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phelan JD, Orekov T, Finkelman FD. Cutting edge: Mechanism of enhancement of in vivo cytokine effects by anti-cytokine monoclonal antibodies. J Immunol. 2008;180:44–48. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamimura D, Bevan MJ. Naive CD8+ T cells differentiate into protective memory-like cells after IL-2 anti IL-2 complex treatment in vivo. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1803–1812. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kieper WC, Burghardt JT, Surh CD. A role for TCR affinity in regulating naive T cell homeostasis. J Immunol. 2004;172:40–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou J, et al. An interleukin-4-induced transcription factor: IL-4 Stat. Science. 1994;265:1701–1706. doi: 10.1126/science.8085155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaplan MH, Schindler U, Smiley ST, Grusby MJ. Stat6 is required for mediating responses to IL-4 and for development of Th2 cells. Immunity. 1996;4:313–319. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahonen CL, et al. Combined TLR and CD40 triggering induces potent CD8+ T cell expansion with variable dependence on type I IFN. J Exp Med. 2004;199:775–784. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang L, et al. Noncoding RNA danger motifs bridge innate and adaptive immunity and are potent adjuvants for vaccination. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1175–1184. doi: 10.1172/JCI15536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Datta SR, et al. Akt phosphorylation of BAD couples survival signals to the cell-intrinsic death machinery. Cell. 1997;91:231–241. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80405-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.del Peso L, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Page C, Herrera R, Nunez G. Interleukin-3-induced phosphorylation of BAD through the protein kinase Akt. Science. 1997;278:687–689. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C. A blast from the past: Clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:965–975. doi: 10.1038/nri957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paulos CM, et al. Microbial translocation augments the function of adoptively transferred self/tumor-specific CD8 T cells via TLR4 signaling. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2197–2204. doi: 10.1172/JCI32205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Morgan DJ, et al. CD8(+) T cell-mediated spontaneous diabetes in neonatal mice. J Immunol. 1996;157:978–983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Martinez X, et al. CD8+ T cell tolerance in nonobese diabetic mice is restored by insulin-dependent diabetes resistance alleles. J Immunol. 2005;175:1677–1685. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.3.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.