Abstract

This study assesses whether the stresses associated with parenting a child are indirectly related to adolescent self-concept through parenting behaviors. We examined longitudinal associations among mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress at age 10, children’s perceptions of parenting at age 10, and adolescents’ self-concept at age 14 in 120 European American families. Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress was related to children’s perceptions of acceptance and psychologically controlling behavior, and psychologically controlling behavior (and lax control for fathers) was related to adolescent self-concept. We further examined which domains of parenting stress and perceived parenting behaviors were associated with adolescents’ scholastic competence, social acceptance, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct. Parenting stress was related to specific parenting behaviors, which were, in turn, related to specific domains of self-concept in adolescence. Parenting stress appears to exert its effects on early adolescent self-concept indirectly through perceived parenting behavior.

Keywords: Parenting Stress, Parenting Behavior, Self-concept, Adolescence

Although parenting is rewarding for most parents (Rogers & White, 1998), parenting a child provides ever-changing challenges as the child grows and develops. Parenting stress (also called childrearing stress) can be attributed to the behavior of the child, to parental difficulty in managing parenting tasks, or to dysfunctional interaction between child and parent (Abidin, 1995). Parenting stress is experienced across all sociodemographic groups and many contexts (Crnic & Low, 2002). In this article, we explore processes by which parenting stress plays a role in children’s perceptions of parenting behaviors and how those perceived parenting behaviors then influence children’s self-concept during the psychologically vulnerable period of the transition into adolescence.

Self-concept (broadly defined as encompassing self-esteem and self-perceptions) is a major component of well-being that has been linked to overall life satisfaction (Diener, 1984; Myers & Diener, 1995), positive emotions (Mahon & Yarcheski, 2002), and protection against anxiety and depression (Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & von Eye, 1994). We chose adolescent self-concept as our outcome for two specific reasons beyond these global relations between self-concept and well-being. First, self-concept appears to decline across late childhood and early adolescence (Baldwin & Hoffmann, 2002). Second, in adolescence, self-concept becomes increasingly differentiated (Harter, 2006), and adolescents’ self-concepts in different domains are conceptually and statistically independent (Harter, 1988). Measuring only global self-concept ignores important variations in emotional, academic, social, and behavioral domains of self-concept (see DuBois & Tevendale, 1999). The ability to assess self-concept across multiple domains is especially significant for adolescents who are transitioning into high school. In this transition, many adolescents experience dips in academic performance, changes in their social circles, reduced satisfaction with physical appearance, and increased behavioral problems (Steinberg, 2005). Therefore, we chose to study self-concept about scholastic competence, social acceptance, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct.

Parents contribute substantially to children’s self-evaluations and feelings of self-worth. For example, parental acceptance and psychological control are related to general, social, home, and school domains of self-concept in 7th to 9th graders (Litovsky & Dusek, 1985). Moreover, perceived maternal acceptance predicts global self-worth, academic competence, physical appearance, and social competence for girls, and paternal acceptance predicts global self-worth, academic competence, and physical appearance for boys (Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & Von Eye, 1998). Parental relationships thus remain influential to adolescent self-concept and well-being, even as adolescents gain autonomy.

Research findings point to several possible processes by which parenting stress may influence adolescents’ self-evaluations and feelings of self-worth. Parenting stress may be directly related to child outcomes (Anthony et al., 2005; Crnic, Gaze, & Hoffman, 2005), or related indirectly through parenting behaviors (Deater-Deckard & Scarr, 1996). Abidin’s (1995) Parenting Stress Model, for example, hypothesizes relations between parenting stress and parenting behaviors, which are in turn related to child outcomes, and no direct relations between parenting stress and child outcomes are hypothesized. The Family Stress Model (Conger, Rueter, & Conger, 2000) similarly suggests that economic stress influences parental emotional distress, marital instability, and disrupted parenting, which, in turn, lead to adolescent maladjustment. Research findings have generally supported the mediating role of parental behavior between parental (economic or work) stress and child adjustment (e.g., Conger et al., 2000; Galambos, Sears, Almeida, & Kolaric, 1995). Furthermore, three studies on stress associated with parenting preschool-aged children lend limited support for the indirect effects of parenting stress on child behavior through parenting (Anthony et al., 2005; Crnic et al., 2005; Deater-Deckard & Scarr, 1996), but much less is known about the impact of parenting stress on adolescent outcomes.

Relationships between parents and adolescents differ from parent-child relationships in that parents and adolescents interact less frequently and their interactions are marked by lower perceived acceptance from parents, power shifts, and increased conflict (Collins & Russell, 1991). These changes in family dynamics could affect relations among parenting stress, perceptions of parenting behaviors, and adolescent self-concept. In examining this possibility, Seginer, Vermulst, and Gerris (2002) found that childrearing stress was indirectly related to adolescents’ positive outlook through parent-adolescent relationships for girls and boys, but childrearing stress was only related to adolescent emotional stability through parent-adolescent relationships for boys. This single study suggests that indirect effects of parenting stresses on adolescent self-concept are plausible and may be likely, but this possibility awaits further research designed to test specific indirect pathways (as we do here).

The main goal of our investigation was to determine whether parenting stress affected perceived parenting behavior, which, in turn, affected adolescent self-concept(s). We expected that parenting stress would exert only indirect effects on adolescent self-concept(s) through perceived parenting behaviors, but we also tested direct effects. Secondary goals were to investigate which domains of parenting stress and perceived parenting behavior are associated with different specific domains of adolescent self-concept and to determine whether daughters and sons, and mothers and fathers, showed similar patterns of relations among parenting stress, perceived parenting behaviors, and adolescent self-concepts.

In the current longitudinal study, we sampled families with early adolescents at two time points – 10 and 14 years. We gathered data from mothers and fathers of girls and boys in samples that were sizable enough to estimate possible moderation by gender. Fathers have been underresearched in the area of parenting stress, and mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress may exert differential influences on their parenting behaviors and on adolescent outcomes.

We chose to study European American two-parent families for several reasons. First, more than 72% of 10- to 14-year-olds in the United States are European American (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). Parenting also has different effects on children and adolescents of different races/ethnicities (Lau, Litrownik, Newton, Black, & Everson, 2006; Park & Bauer, 2002), and self-esteem differs in children and adults of different races (Twenge & Crocker, 2002). For example, parental warmth is a protective factor against externalizing behavior for European American families, but a risk factor for African American families (Lau et al., 2006). These differences would cloud the effects of this study if racial groups were combined. Furthermore, race and socioeconomic status are often confounded, and educated European American families are not at “low-risk” compared to other groups; they are at similar or even greater risk of low self-esteem, academic failure, and externalizing problems than poor or minority groups (Luthar & Ansary, 2005; Luthar & D’Avanzo, 1999; Twenge & Crocker, 2002).

We expected that all forms of parenting stress could affect perceived parenting behaviors. Being a dyadic process, parenting could be equally affected by parental distress, adolescent behavior, or dysfunctional parent-adolescent interaction. We also expected that parental acceptance, psychological control, and lax control would be related to adolescent self-concept. Parental acceptance would likely lead to a stronger self-concept, whereas psychological control and lax control could erode feelings of self-confidence and competence. Parental acceptance is likely to affect all domains of self-concept because of the pervasive nature and fundamental importance of feeling loved, accepted, and approved of by one’s parents. Psychological control and lax control may be more strongly related to self-concept regarding school and behavior than appearance and social acceptance because parental control seems more closely linked to behavioral than social domains. Parenting stress and adolescent self-concept are both cognitive processes that are unlikely to affect one another without some connecting behavior.

Method

Participants

A total of 120 European American families participated: 120 adolescents, 120 mothers, and 106 fathers (total N = 346; data were not received from 14 fathers). All family members provided data when the adolescent (51 girls, 69 boys) was 10 years old (M = 10.25 years, SD =.17, range = 9.99–10.87), and the adolescent provided additional data when s/he was 14 years old (M = 13.85 years, SD =.24, range = 13.48–14.74). Families were originally recruited through mass mailings and newspaper advertisements from an east coast metropolitan area as part of an ongoing longitudinal study. At 10 years, 169 mothers and adolescents (71% retention rate from 10 to 14 years) and 146 fathers (73% retention rate) provided data. Parenting stress and parenting behavior did not differ for families that remained in the study versus families that did not participate at 14 years, ts(144–167) = −1.12 – 1.79, ns.

At the first assessment, mothers averaged 41.55 years of age (SD = 4.82), and fathers averaged 43.16 years of age (SD = 5.30). The highest level of maternal education was high school or partial college for 17.65%, a standard 4-year college degree for 39.25%, and a graduate or professional degree for 47.06%. Fathers’ education was similar: 19.05%, 27.62%, and 53.33%, respectively. At the time of the first assessment, 71.67% of mothers were working outside the home, and those who were employed (n = 86) worked an average of 32.58 hours/week (SD = 12.20). All fathers worked outside the home. Families were mostly intact (92.5%) and middle to upper-middle socioeconomic status (SES; Hollingshead, 1975) with a mean of 56.47 (SD = 8.59, range = 25–66). All adolescents were firstborn in their families; 18% were only children, 60% had 1 sibling, 18% had 2 siblings, and 4% had 3 or more siblings.

Procedures

When their children were 10 years old, mothers and fathers individually rated their parenting stress. Adolescents also rated their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors. When children were 14 years old, adolescents rated their self-concept. The 10-year-olds filled out the questionnaires about parenting behavior in the presence of a researcher. All other questionnaires were filled out at home in advance and returned at a visit. Informed consent/assent was obtained from parents and adolescents, participants were compensated for their time, and the study was approved and monitored by our institutional review board.

Measures

Internal consistency (α) estimates on the current sample for all scales are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of mother and father parenting stress and parenting behaviors, and adolescent self-concept

| Mother (N = 120) | Father (N = 106) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | αMa | αFa | M | SD | M | SD |

| Parenting Stress | ||||||

| Parental Distress | .79 | .80 | 25.67 | 6.02 | 26.13 | 6.31 |

| Dysfunctional Interaction | .87 | .84 | 20.25 | 6.37 | 19.72 | 5.54 |

| Difficult Child | .89 | .86 | 27.81 | 8.45 | 26.92 | 7.07 |

| Child Report of Parenting Behavior | ||||||

| Acceptance/Rejection | .84 | .83 | .00 | .93 | .00 | .92 |

| Psychological | .83 | .78 | .00 | .93 | .00 | .90 |

| Autonomy/Control | ||||||

| Firm/Lax Control | .62 | .73 | .00 | .85 | .00 | .89 |

| Adolescent Self-Concept | Adolescent (N = 120) | |||||

| Scholastic Competence | .77 | -- | 3.30 | .60 | -- | -- |

| Social Acceptance | .67 | -- | 3.11 | .66 | -- | -- |

| Physical Appearance | .74 | -- | 2.75 | .67 | -- | -- |

| Behavioral Conduct | .72 | -- | 3.15 | .61 | -- | -- |

Note. αMa = Internal consistency estimate for mothers/reports of mothers, αFa = Internal consistency estimate for fathers/reports of fathers.

The Parenting Stress Index, Short Form (PSI-SF; Abidin, 1995) is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that assesses stressors originating in the parent, child, and parent-child interaction – parental distress (e.g., “I feel trapped by my responsibilities as a parent.”), parent-child dysfunctional interaction (e.g., “Sometimes my child does things that bother me just to be mean.”), and difficult child (e.g., “My child generally wakes up in a bad mood.”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale from strongly disagree (0) to strongly agree (4), and scales are computed as the sum of the 12 items comprising the scale. These scales have adequate internal consistency, ɑs=.80 –.87, 6-month test-retest reliability, rs =.68 –.85, and are highly correlated with the scales from the full-length PSI (Abidin, 1995).

The Revised Children’s Report of Parental Behavior Inventory (CRPBI; Margolies & Weintraub, 1977) is a 56-item questionnaire that measures three domains of parenting behavior from the adolescent’s perspective. The acceptance/rejection domain (high score = greater acceptance) was computed as the mean of two standardized subscales: a 16-item acceptance scale (e.g., “makes me feel better when I am upset”) and an 8-item child centeredness scale (e.g., “gives me a lot of care and attention”). The psychological autonomy/control domain (high score = greater psychological control) was computed as the mean of two standardized 8-item subscales: control through guilt (e.g., “feels hurt by the bad things I do”) and instilling persistent anxiety (e.g., “says that sooner or later we always pay for bad behavior”). The firm/lax control domain (high score = greater lax control) was computed as the mean of two standardized 8-item subscales: lax discipline (e.g., “lets me get away with a lot of things”) and non-enforcement of rules (e.g., “is easy with me”). Items are rated as very true (2), sometimes true (1), or not at all true (0). Five-week test-retest reliability for a group of 4th- to 6th-grade children ranged from.79 to.93 for reports of mother and.77 to.81 for reports of father (Margolies & Weintraub, 1977).

The Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents (SPPA; Harter, 1988) is a 45-item questionnaire designed to assess self-concept in 9 domains. In the current study, we used the scholastic competence (academic ability, intelligence), social acceptance (acceptance by peers, popularity, likeability), physical appearance (satisfaction with looks, body image), and behavioral conduct (acts appropriately, avoids trouble) scales because they cover 4 important areas of self-image for young adolescents. Responses are scored from 1–4, with a high score indicating positive self-perceptions. All scales are computed as the mean of 5 items. For the scales used in this study, Harter (1988) reported internal consistency reliabilities above .75 in 4 samples of 8th to 11th graders.

Analytic Plan

We computed 2 general structural equation models (SEMs; one each for mothers and fathers) and 8 domain-specific path analyses (4 self-concept outcomes for mothers and fathers separately). The models were designed to assess whether (1) parenting stress was related to the child’s perceptions of parental acceptance, psychological control, and lax control from that parent, (2) parental acceptance, psychological control, and lax control were related to adolescent self-concept, and (3) the addition of a direct path from parenting stress to adolescent self-concept would significantly improve model fit. We computed both SEMs and path analyses because they provide different information. The SEMs inform whether parenting stress as a whole is related to parenting behaviors and general self concept. The path analyses allow investigatation of which sources of parenting stress are most related to parenting behaviors and individual domains of the adolescent self-concept.

After testing the initial structural equation and path models, we reduced each model by sequentially removing nonsignificant paths from the model. The path with the smallest critical value was identified, the path was removed, the model was refit, and this procedure was repeated until no nonsignificant paths remained. We chose to sequentially drop nonsignificant paths because removal of a single nonsignificant path or variable has an impact on the parameter estimates of the other paths in the model. After dropping all nonsignificant paths, we then added a direct path from parenting stress to self-concept as a means of testing whether the direct path explained a significant amount of additional variance in the model (as indexed by the change in χ2 for the final model and the model with the additional path). Finally, we checked whether the structural paths were invariant for boys and girls by evaluating two multiple-group models for each final model tested. The first multiple-group model allowed all structural paths to vary for girls and boys; the second model constrained the structural paths to be equal for girls and boys. If the difference in model fit (as indexed by the change in χ2 for the two models) was nonsignificant, then the model structure fit equally well for girls and boys (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 1993).

Results

Preliminary Analyses, Descriptive Statistics, and Correlations

Prior to data analysis, univariate and multivariate distributions of all variables were examined for normalcy, outliers, and influential cases, and transformations were applied to resolve problems of non-normality (Tabachnick & Fidell, 1996). For ease of interpretation, descriptive statistics are presented in the variables’ original metrics, and standardized path coefficients are reported in figures.

Table 1 displays the descriptive statistics of maternal and paternal parenting stress, child report of maternal and paternal parenting, and adolescent self-concept. Mothers and fathers did not differ in their average parenting stress, ts(105) = −.41 – 1.51, ns, and parents were rated as equally accepting, t(105) = 1.00, ns, but adolescents rated their fathers as more psychologically controlling and more lax than their mothers, ts(105) = −2.03 and −2.29, ps ≤.05, respectively. Mothers and fathers of girls and boys reported similar levels of parenting stress, ts(105) = −.17 –.26, ns, and girls and boys reported that their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors were similar, ts(104–118) = −1.37 –.29, ns, except that girls reported greater acceptance from their fathers than boys, t(104) = 2.06, p ≤.05. Girls and boys were similar in their average levels of self-concept in all domains, ts(118) = −.19 – 1.92, ns.

Table 2 displays intercorrelations among maternal and paternal parenting stress, child report of maternal and paternal parenting, and adolescent self-concept. The three PSI-SF scales shared 24–50% of their variance for mothers and 26–40% for fathers. Among the CRPBI factors, only autonomy/control and firm/lax control were correlated, sharing 7% of their variance for reports of mothers and 4% for reports of fathers. The adolescents’ self-concept scales shared 4–27% of their variance. Harter (1988) reported a similar range of shared variance (3–25%) in her 9th-grade sample. Although there is some overlap among the four self-concept domains, two-thirds or more of the variance in the scales is not shared, and self-concept in each domain could be constructed differently (e.g., based on different information or input from the environment). Therefore, we examined general self-concept, as measured by a latent variable of the four domains, as well as each of the four domains separately. We used a latent variable of the four domains of self-concept instead of the SPPA global self-worth scale because we were interested in first fitting a general model of relations between parenting stress, perceived parenting behaviors, and self-concept across domains, and then exploring unique relations for each domain of self-concept.

Table 2.

Correlations among maternal and paternal parenting stress, child perception of maternal and paternal parenting, and adolescent self-concept

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parenting Stress | ||||||||||||||||

| 1. Parental Distress | -- | .49*** | .47*** | −.16 | −.15 | −.16 | .11 | .13 | .06 | .05 | .09 | −.01 | −.08 | −.11 | −.09 | −.05 |

| 2 Dysfunctional Interaction | .63*** | -- | .71*** | −.16 | −.18 | −.14 | .15 | .18* | .10 | −.04 | .01 | −.08 | −.20* | −.09 | −.16 | −.09 |

| 3. Difficult Child | .51*** | .63*** | -- | −.24** | −.23* | −.23* | .21 | .17 | .21* | −.17 | −.08 | −.21* | −.25** | −.13 | −.12 | −.18* |

| Child Report of Parenting Behavior | ||||||||||||||||

| 4. Acceptance/ Rejection | −.21* | −.20* | −.16 | -- | .91*** | .95*** | −.04 | .04 | −.10 | .02 | −.15 | .19* | .14 | .19* | .11 | .16 |

| 5. Acceptance | −.17 | −.19 | −.15 | .87*** | -- | .75*** | −.14 | −.06 | −.19* | .07 | −.06 | .19* | .23* | .21* | .13 | .20* |

| 6. Child Centeredness | −.14 | −.15 | −.12 | .92*** | .67*** | -- | .06 | .11 | −.01 | −.03 | −.22* | .16 | .07 | .16 | .10 | .12 |

| 7. Autonomy/ Control | .13 | .29** | .23* | −.01 | −.12 | .02 | -- | .91*** | .92*** | −.27** | −.38*** | −.08 | −.49*** | −.11 | −.08 | −.20* |

| 8. Control Through Guilt | .08 | .22* | .14 | .04 | −.07 | .07 | .90*** | -- | .69*** | −.17 | −.29*** | −.00 | −.36*** | −.04 | −.02 | −.11 |

| 9. Instills Anxiety | .16 | .29** | .26** | −.08 | −.18 | −.05 | .90*** | .63*** | -- | −.31*** | −.38*** | −.15 | −.53*** | −.17 | −.12 | −.26** |

| 10. Firm/ Lax Control | .04 | −.04 | −.07 | .14 | .16 | .17 | −.21* | −.07 | −.31*** | -- | .85*** | .85*** | .19* | −.04 | −.07 | −.02 |

| 11. Lax Discipline | .08 | −.05 | −.09 | .01 | .08 | .02 | −.32*** | −.21* | −.37*** | .89*** | -- | .45*** | .21* | −.05 | −.10 | .04 |

| 12. Non- Enforcement Of Rules | −.01 | −.03 | −.03 | .24* | .21* | .28** | −.05 | .08 | −.18 | .89*** | .57*** | -- | .12 | −.03 | −.03 | −.08 |

| Self-concept | ||||||||||||||||

| 13. Scholastic Competence | −.04 | −.07 | −.12 | .03 | .09 | .00 | −.37*** | −.35*** | −.31*** | −.07 | −.01 | −.10 | -- | .33*** | .38*** | .46*** |

| 14. Social Acceptance | .08 | .05 | .01 | .28** | .26** | .28** | −.07 | −.03 | −.10 | .10 | .02 | .16 | .32*** | -- | .49*** | .21* |

| 15. Physical Appearance | −.03 | −.05 | −.04 | .10 | .11 | .10 | −.02 | −.04 | .00 | −.10 | −.12 | −.05 | .41*** | .52*** | -- | .19* |

| 16. Behavioral Conduct | .01 | −.06 | −.12 | .07 | .07 | .08 | −.26** | −.20* | −.26** | −.22* | −.16 | −.23* | .48*** | .23* | .20* | -- |

Note. Correlations for mothers (N = 120) are above the diagonal, and correlations for fathers (N = 106) are below the diagonal.

p≤.05.

p ≤.01.

p ≤.001.

Direct vs. Indirect Effects of General Parenting Stress on Adolescent Self-Concept

General model design

In both the mother and father models, the three PSI-SF scales were loaded on a latent variable for parenting stress. Latent variables for acceptance/rejection, autonomy/control, and firm/lax control each had two observed indicators (the scales that composed them), and the four SPPA variables were loaded on a self-concept latent variable. In addition to latent variable indicator loadings, paths were estimated from parenting stress to acceptance/rejection, autonomy/control, and firm/lax control, and from acceptance/rejection, autonomy/control, and firm/lax control to self-concept.

Because autonomy/control and firm/lax control were somewhat correlated (see Table 2), we allowed their disturbance terms to covary in the model. We also specified an error covariance between SPPA social and appearance scales because, after fitting an initial model, we found that they shared additional variance that was not accounted for by their latent factor. Finally, in the initial models for both mother and father, one of the two indicator loadings of firm/lax control produced a Heywood case (i.e., a standardized path coefficient above 1.0; see Dillon, Kumar, & Mulani, 1987). Because we were not primarily interested in the indicator loadings, we fixed the loadings of both indicators to 1.0 to give them equal weight. All model fit statistics are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Initial and reduced model fit statistics

| Initial Model

|

Reduced Model

|

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | χ2 | df | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA | 90% CI | χ2 | df | CFI | SRMR | RMSEA | 90% CI | |

| 1. General | Mother | 77.53* | 58 | .96 | .08 | .05 | .01–.08 | 41.21 | 41 | 1.00 | .08 | .01 | .00–.06 |

| Model | Father | 77.17* | 58 | .96 | .08 | .06 | .01–.09 | 77.46 | 60 | .96 | .08 | .05 | .00–.08 |

| 2. Scholastic | Mother | 3.02 | 5 | 1.00 | .03 | .00 | .00–.10 | 4.77 | 3 | .96 | .06 | .07 | .00–.18 |

| Competence | Father | 3.98 | 5 | 1.00 | .03 | .00 | .00–.12 | 1.79 | 6 | 1.00 | .03 | .00 | .00–.03 |

| 3. Social | Mother | .93 | 5 | 1.00 | .02 | .00 | .00–.00 | 1.95 | 3 | 1.00 | .04 | .00 | .00–.13 |

| Acceptance | Father | 5.70 | 5 | .99 | .05 | .04 | .00–.15 | 5.02 | 6 | 1.00 | .05 | .00 | .00–.12 |

| 4. Physical | Mother | 2.29 | 5 | 1.00 | .03 | .00 | .00–.08 | .03 | 1 | 1.00 | .01 | .00 | .00–.13 |

| Appearance | Father | 3.03 | 5 | 1.00 | .03 | .00 | .00–.10 | 1.49 | 3 | 1.00 | .03 | .00 | .00–.13 |

| 5. Behavioral | Mother | 2.69 | 5 | 1.00 | .02 | .00 | .00–.09 | 4.30 | 3 | .92 | .06 | .06 | .00–.18 |

| Conduct | Father | 5.30 | 5 | 1.00 | .04 | .02 | .00–.14 | 6.36 | 7 | 1.00 | .04 | .00 | .00–.11 |

Note. The Chi-squares reported are weighted least squares χ2.

p ≤.05.

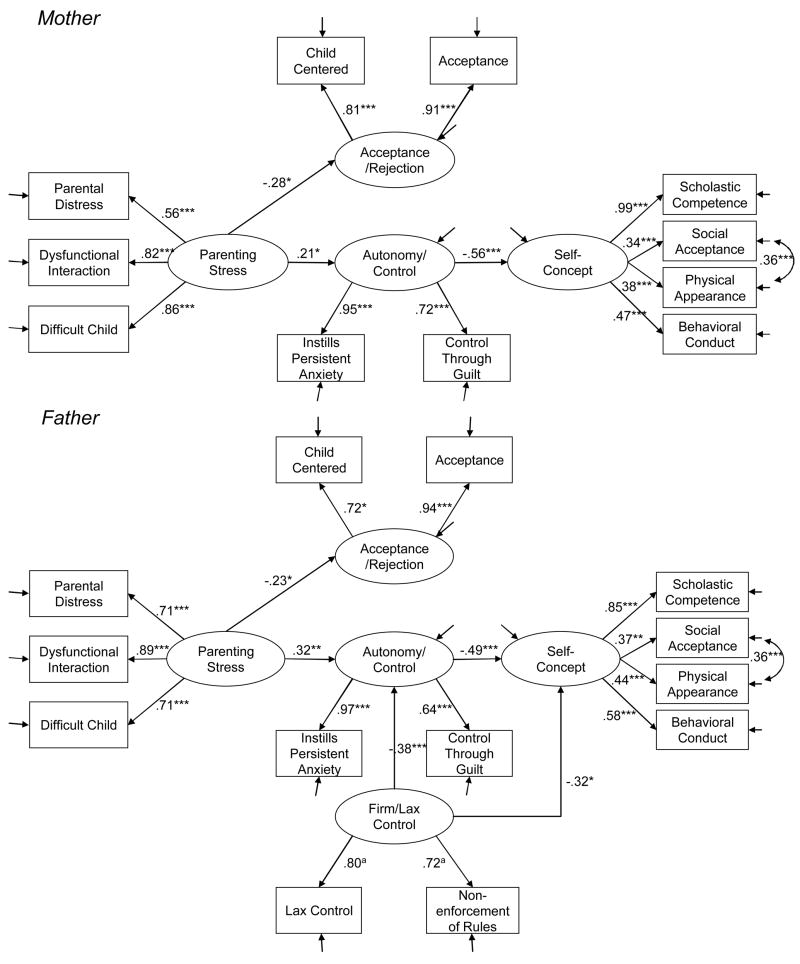

Results for mothers

The initial model was a reasonable fit to the data. After reducing the model by sequentially dropping nonsignficant paths, the final reduced model (see Figure 1, top) was a better fit to the data (see Table 3, Row 1). In this reduced model, parenting stress was associated with lower perceived acceptance and higher perceived psychological control, and lower perceived psychological control was associated with a more positive self-concept in early adolescence. The indirect effect of parenting stress on self-concept through maternal behaviors was nonsignificant (standardized coefficient = −.12, ns).

Figure 1.

Final models of maternal and paternal parenting stress, perceived parenting behavior,and adolescent self-concept.

a Path was fixed.

The added path from the parenting stress latent variable to the self-concept latent variable was not statistically significant (standardized coefficient = −.17), nor was the difference in the chi-squares for the 2 models, Δχ2(1) = 3.35, ns, indicating that there was no direct effect of parenting stress on adolescent self-concept.

Results for fathers

The initial model also fit the data. After reducing the model by sequentially dropping nonsignficant paths, the final reduced model (see Figure 1, bottom) was a good fit to the data. In this reduced model, parenting stress was associated with perceptions of lower acceptance and greater psychological control, and perceptions of greater psychological control and more lax control were associated with a less positive self-concept in early adolescence. The indirect effect of parenting stress on self-concept through psychological control was also significant (standardized coefficient = −.16, p≤.05).

The added path from the parenting stress latent variable to the self-concept latent variable was not statistically significant (standardized coefficient =.06), nor was the difference in the chi-squares for the 2 models, Δχ2(1) = 0.23, ns, indicating that there was no direct effect of parenting stress on adolescent self-concept.

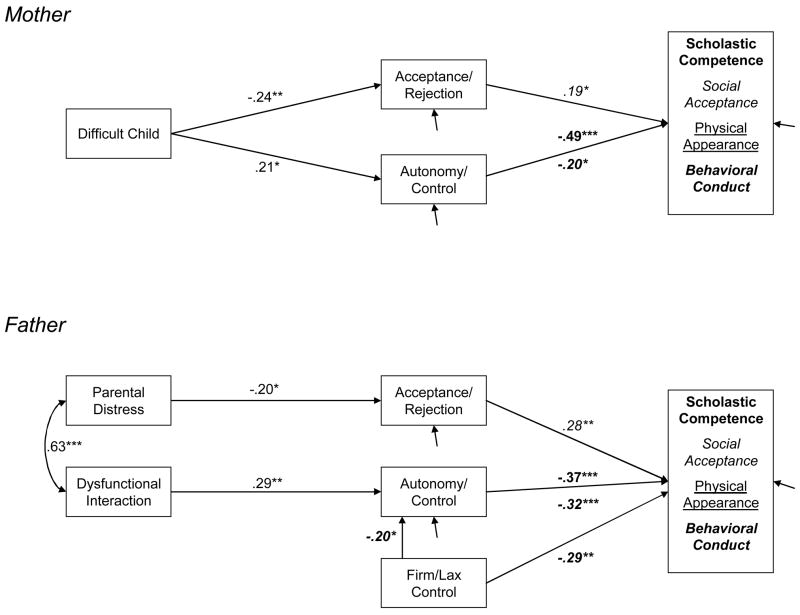

Indirect Effects of Parenting Stressors on Individual Domains of Adolescent Self-Concept

We next investigated the differential relations of parenting stress with each of the 4 self-concept scales in separate path analyses. The 3 PSI-SF scales were included in each model and allowed to covary to account for correlations among the scales. Paths were estimated from each of the three PSI-SF scales to each of the three CRPBI domains, and from each of the CRPBI domains to the self-concept outcome variable. Because autonomy/control and firm/lax control were correlated, we allowed their error terms to covary in the model. Relations between parenting stress and perceived parenting behavior were the same for all models (Figure 2), but relations between perceived parenting behaviors and adolescent self-concept, as well as indirect relations between parenting stress and adolescent self-concept, varied by the outcome variable. The initial models for mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress, perceived parenting behavior, and adolescent scholastic competence, social acceptance, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct fit the data but also contained several nonsignificant paths. The reduced models are presented in Figure 2 and detailed below. All model fit statistics are presented in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Final models of maternal and paternal parenting stress, perceived parenting behavior, and adolescent self-concept about scholastic competence, social acceptance, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct.

Note. Path coefficients in regular font apply to all models, bolded path coefficients apply to the scholastic competence models, italicized coefficients apply to the social acceptance models, and bolded and italicized coefficients apply to the behavioral conduct models. No path coefficients were significant between perceived parenting behaviors and physical appearance. * p ≤.05. ** p ≤.01. *** p ≤.001.

Scholastic competence

Mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult were related to lower perceived acceptance, β = −.24, p ≤.01, and higher perceived psychological control, β =.21, p ≤.05, and lower perceived psychological control was associated with greater scholastic competence, β = −.49, p ≤.001. The indirect effect of mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult on scholastic competence was significant (β = −.10, p ≤.05); however, adding a direct path from mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult to scholastic competence did not significantly improve model fit, Δχ2(1) = 3.39, ns. Fathers’ parental distress was related to lower perceived acceptance, β = −.20, p ≤.05, perceptions of dysfunctional interaction with their adolescents were related to higher perceived psychological control, β =.29, p ≤.01, and lower psychological control was associated with greater adolescent scholastic competence, β = −.37, p ≤.001. The indirect effect of fathers’ perceptions of dysfunctional interaction on scholastic competence was significant (β = −.11, p ≤.05); however, adding a direct path from dysfunctional interaction to scholastic competence did not significantly improve model fit, Δχ2(1) =.14, ns.

Social acceptance

Mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult were related to lower perceived maternal acceptance, β = −.24, p ≤.01, and greater psychological control, β =.21, p ≤.05, and higher perceived maternal acceptance was associated with a more positive self-concept regarding social acceptance, β =.19, p ≤.05. The indirect effect of mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult on social acceptance was not significant (β = −.04, ns), and adding a direct path from difficult child to social acceptance did not significantly improve model fit, Δχ2(1) =.92, ns. Fathers’ distress was related to lower perceived paternal acceptance, β = −.20, p ≤.05, dysfunctional parent-adolescent interaction was associated with greater psychological control, β =.29, p ≤.01, and higher perceived acceptance was associated with a more positive adolescent self-concept regarding social acceptance, β =.28, p ≤.01. The indirect effect of fathers’ distress on social acceptance was not significant (β = −.06, ns), and adding a direct path from difficult child to social acceptance did not significantly improve model fit, Δχ2(1) = 1.16, ns.

Physical appearance

Mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult were related to lower perceived acceptance, β = −.24, p ≤.01, and higher perceived psychological control, β =.21, p ≤.05. However, acceptance and psychological control were unrelated to adolescent self-concept about physical appearance. For fathers, parental distress was associated with lower perceived acceptance, β = −.20, p ≤.05, and dysfunctional interaction was related to higher perceived psychological control, β =.29, p ≤.01, but neither acceptance nor psychological control was associated with adolescent self-concept regarding physical appearance.

Behavioral conduct

Mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult was related to lower perceived acceptance, β = −.24, p ≤.01, and higher perceived psychological control, β =.21, p ≤.05, and lower perceived psychological control was associated with more positive adolescent self-concept about behavioral conduct, β = −.20, p ≤.05. The indirect effect of mothers’ perceptions of their adolescents as difficult on self-concept regarding behavioral conduct was nonsignificant (β = −.04, ns), and adding a direct path from difficult child to behavioral conduct did not significantly improve model fit, Δχ2(1) = 2.42, ns. Fathers’ parental distress was associated with lower perceived acceptance, β = −.20, p ≤.05, perceptions of dysfunctional interaction with their adolescents were related to higher perceived psychological control, β =.29, p ≤.01, and lower perceived psychological control, β = −.32, p ≤.001, and less lax control, β = −.29, p ≤.01, were associated with a more positive adolescent self-concept regarding behavioral conduct. The indirect effect of fathers’ perceptions of dysfunctional interaction on adolescent self-concept regarding behavioral conduct was significant (β = −.09, p ≤.05); however, adding a direct path from dysfunctional interaction to adolescent behavioral conduct did not significantly improve model fit, Δχ2(1) =.01, ns.

Gender Differences in Model Fit

In all reduced mother and father models, the structures held for girls and boys. For the general models, when the structural paths were constrained to be equal, no significant reduction in mother or father model fit emerged, Δχ2(3) = 3.01, ns, and Δχ2(4) = 2.43, ns, respectively, indicating that the model structure was similar for girls and boys. The same was true for mother and father models for all 4 domains of self-concept, Δχ2s(2–4) = 3.99–7.32, ns.

Discussion

In a sample of 120 European American families, stress associated with parenting a 10-year-old child was related to adolescents’ perceptions of their parents’ behaviors, which were in turn related to adolescents’ own self-concept 4 years later. Direct relations from parenting stress to adolescent self-concept were not supported in any of our models. Our study provides support for further research on the indirect effects of parenting stress on self-concept in early adolescence via perceived parenting behaviors.

Our European American parents experienced parenting stress, and this stress was sometimes associated with the way their adolescents perceived their parenting and felt about themselves. Researchers often incorrectly assume that educated European American families are at lower risk for problems than families of lower socioeconomic status or minority families. In fact, at least some conditions that lead to parenting stress and low self-esteem (academic failure, drug use, interruption of parent-adolescent closeness) may be as common (if not more so) in educated, European American families as in low income or minority families (Luthar & Ansary, 2005; Luthar & D’Avanzo, 1999; Luthar & Latendresse, 2005; Twenge & Crocker, 2002). Our study explored family dynamics in this populous and homogenous subgroup. We expect that the pattern of relations we found could differ in other populations.

We were able to determine which of three sources of parenting stress (parent, adolescent, or dyad) was most strongly related to perceived parenting behaviors and which perceived parenting behaviors were related to adolescent self-concept about scholastic competence, social acceptance, physical appearance, and behavioral conduct. Our results suggest that mothers’ perceived acceptance and psychological control may be most affected by stress attributed to the adolescent behavior, and fathers’ perceived acceptance and psychological control may be more affected by their own distress and stress attributed to difficulty in the parent-adolescent relationship, respectively. This is an important distinction in how different sources of mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress undermine parenting. For example, when mothers perceive stressful problem behaviors in their adolescents, their parenting of that adolescent may be affected; by contrast, as long as fathers continue to cope well as a parent and the father-adolescent relationship remains intact, their parenting of that adolescent may be relatively unaffected.

With regard to which perceived parenting behaviors are related to different domains of adolescent self-concept, perceived maternal and paternal acceptance were associated with adolescent social acceptance. Having strong relationships with parents appears to lead to healthy relationships with peers and others (e.g., Coleman, 2003; Verschueren & Marcoen, 2005). Perceived quality of affect from both parents is associated with adolescents’ feelings of social competence (Paterson, Pryor, & Field, 1995), and parental acceptance is associated with self-perceived social acceptance for 6th- and 7th- grade girls, but not boys (Ohannessian, Lerner, Lerner, & von Eye, 1996; Ohannessian, Lerner, von Eye, & Lerner, 1998). Perhaps parental acceptance shows adolescents that they are likeable and thus leads to feelings of social acceptance from others.

In the models on adolescent self-concept about physical appearance, mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress were related to perceived parenting behaviors, but perceived parenting behaviors were unrelated to adolescent self-concept about physical appearance. Adolescents may derive their self-concept about their appearance more from peers than from parents. Family support is unrelated to body image, and peer influences explain more than twice the variance in body image than family and media influences combined (Paxton, Schutz, Wertheim, & Muir, 1999).

Perceived psychological control from both mothers and fathers was associated with adolescents’ self-concepts about scholastic competence and behavioral conduct. Maternal and paternal psychological control has been linked to global self-concept in adolescents (Gray & Steinberg, 1999), and the link between psychological control and behavior problems is well established (Armentrout, 1971; Barber & Harmon, 2002). Perceived maternal and paternal psychological control are related to lower self-reliance in 9-year-olds (Shulman, Collins, & Dital, 1993). Having low self-reliance could affect adolescent perceptions of their academic and behavioral competencies.

Paternal lax control was associated with adolescent lower self-concept about behavioral conduct. The extant findings on firm/lax control are mixed, and firm/lax control has not previously been examined in relation to self-concept about behavioral conduct specifically. Armentrout (1971) found no relations between mothers’ and fathers’ firm/lax control and child internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. However, parental behavioral control (the opposite end of the continuum from lax control) is associated with fewer adolescent behavioral problems (Gray & Steinberg, 1999). Finally, behavioral control from European American fathers, but not mothers, is related to global self-esteem in adolescence (Bean, Bush, McKenry, & Wilson, 2003). Perhaps in intact families, fathers are more often the primary disciplinarians, and their lax control encourages actual or perceived adolescent misbehavior.

The present findings support the link between parental functioning and behavior with self-concept in early adolescence. In a large-scale review of the effects of parent-adolescent relationships on adolescent functioning, Steinberg (2001) concluded that “adolescents benefit from having parents who are authoritative: warm, firm, and accepting of their needs for psychological autonomy” (p. 1). Gray and Steinberg (1999) explored the three components of authoritative parenting (acceptance-involvement, strictness-supervision, and psychological autonomy granting) in high school students. Parental acceptance-involvement and psychological autonomy granting (the other pole of the continuum of psychological control) were uniquely related to adolescent psychosocial functioning (a composite of self-concept, self-reliance, and work orientation) and academic competence. Similarly, we found that all three dimensions of authoritative parenting – acceptance, lack of psychological control, and firm control – were predictive of one or more domains of a positive adolescent self-concept.

Our study contributes to the literature on the family antecedents of adolescent self-concept in a variety of ways, but is also limited in several respects. The sample was self-selected, and representative only of educated, intact, European American families with young adolescents. Other studies using families who are also dealing with other types of strain (e.g., economic), or families of other ethnicities, may find different patterns of results. There are certainly also other factors not measured here that contribute to adolescents’ self-concepts. The sample size limited our power to detect small effects, and high correlations among the parenting stress scales made it difficult to parse the effects of the individual sources of stress.

Overall, this study demonstrates that educated, European American parents experience parenting stress that their stress is associated with the way their adolescent children perceive their parenting, and perceived parenting is related to the adolescent’s self-concept in several domains. It is important to recognize that even those parents who seem to be low risk in terms of their socioeconomic status are stressed by the transition to adolescence and the stress they experience can adversely affect their parenting (or at least the way their parenting is perceived by their children). Interventions to improve adolescent self-concept might most beneficially concentrate both on adolescent perceptions of parenting behavior and the stress associated with parenting that may lead parents to non-optimal parenting behaviors. Interventions at the family level may also benefit from focusing on the specific behaviors that make adolescents report that their parents are accepting versus controlling. Furthermore, acknowledging the 3 sources of parenting stress and their differential impacts on adolescents’ perceptions of their mothers’ and fathers’ parenting behaviors could be useful in tailoring more efficacious interventions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD. Address correspondence to: Diane L. Putnick, Child and Family Research, NICHD, NIH, Suite 8030, 6705 Rockledge Drive, Bethesda MD 20892-7971, U.S.A. Email: putnickd@mail.nih.gov

References

- Abidin RR. Parenting Stress Index Professional Manual. 3. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Anthony LG, Anthony BJ, Glanville DN, Naiman DQ, Waanders C, Shaffer S. The relationships between parenting stress, parenting behaviour and preschoolers’ social competence and behaviour problems in the classroom. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:133–154. [Google Scholar]

- Armentrout JA. Parental child-rearing attitudes and preadolescents’ problem behaviors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1971;37:278–285. doi: 10.1037/h0031904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin SA, Hoffmann JP. The dynamics of self-esteem: A growth-curve analysis. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2002;31:101–113. [Google Scholar]

- Barber BK, Harmon EL. Violating the self: Parental psychological control of children and adolescents. In: Barber BK, editor. Intrusive Parenting: How Psychological Control Affects Children and Adolescents. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 15–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bean RA, Bush KR, McKenry PC, Wilson SM. The impact of parental support, behavioral control, and psychological control on the academic achievement and self-esteem of African American and European American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 2003;18:523–541. [Google Scholar]

- Blyth DA, Traeger C. Adolescent self-esteem and perceived relationships with parents and peers. In: Selzinger S, Antrobus J, Hammer M, editors. Social Networks of Children, Adolescents, and College Students. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988. pp. 171–194. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PK. Perceptions of parent-child attachment, social self-efficacy, and peer relationships in middle childhood. Infant and Child Development. 2003;12:351–368. [Google Scholar]

- Collins WA, Russell G. Mother-child and father-child relationships in middle childhood and adolescence: A developmental analysis. Developmental Review. 1991;11:99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Rueter MA, Conger RD. The role of economic pressure in the lives of parents and their adolescents: The family stress model. In: Crockett LJ, Silbereisen RK, editors. Negotiating adolescence in times of social change. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 201–233. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic KA, Gaze C, Hoffman C. Cumulative parenting stress across the preschool period: Relations to maternal parenting and child behaviour at age 5. Infant and Child Development. 2005;14:117–132. [Google Scholar]

- Crnic K, Low C. Everyday stresses and parenting. In: Bornstein MH, editor. Handbook of Parenting: Vol. 5: Practical Issues in Parenting. 2. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2002. pp. 243–267. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Scarr S. Parenting stress among dual-earner mothers and fathers: Are there gender differences? Journal of Family Psychology. 1996;10:45–59. [Google Scholar]

- Diener E. Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;95:542–575. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuBois DL, Tevendale HD. Self-esteem in childhood and adolescence: Vaccine or epiphenomenon? Journal of Preventive Psychology. 1999;8:103–117. [Google Scholar]

- Galambos NJ, Sears HA, Almeida DM, Kolaric GC. Parents’ work overload and problem behavior in young adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1995;5:201–223. [Google Scholar]

- Gray MR, Steinberg L. Unpacking authoritative parenting: Reassessing a multidimensional construct. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61:574–587. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. Manual for the Self-Perception Profile for Adolescents. Denver, CO: University of Denver; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Harter S. The self. In: Damon W, Lerner RM, Eisenberg N, editors. Handbook of Child Psychology. Vol 3: Social, Emotional, and Personality Development. 6. New York: Wiley; 2006. pp. 505–570. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. The four-factor index of social status. Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Jöreskog K, Sörbom D. Lisrel 8: Structural Equation Modeling with the SIMPLIS Command Language. Lincolnwood, IL: Scientific Software International; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lau AS, Litrownik AL, Newton RR, Black MM, Everson MD. Factors affecting the link between physical discipline and child externalizing problems in black and white families. Journal of Community Psychology. 2006;34:89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Litovsky VG, Dusek JB. Perceptions of child rearing and self-concept development during the early adolescent years. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1985;14:373–387. doi: 10.1007/BF02138833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Ansary NS. Dimensions of adolescent rebellion: Risks for academic failure among high- and low-income youth. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:231–250. doi: 10.1017/s0954579405050121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, D’Avanzo K. Contextual factors in substance use: A study of suburban and inner-city adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:843–867. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499002357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Latendresse SJ. Comparable “risks” at the socioeconomic status extremes: Preadolescents’ perceptions of parenting. Development and Psychopathology. 2005;17:207–230. doi: 10.1017/s095457940505011x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahon NE, Yarcheski A. Alternative theories of happiness in early adolescents. Clinical Nursing Research. 2002;11:306–323. doi: 10.1177/10573802011003006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolies PJ, Weintraub S. The revised 56-item CRPBI as a research instrument: Reliability and factor structure. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1977;33:472–476. [Google Scholar]

- Myers DG, Diener E. Who is happy? Psychological Science. 1995;6:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A. A longitudinal study of perceived family adjustment and emotional adjustment in early adolescence. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1994;14:371–390. [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner RM, Lerner JV, von Eye A. Perceived parental acceptance and early adolescent self-competence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1998;68:621–629. doi: 10.1037/h0080370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohannessian CM, Lerner RM, von Eye A, Lerner JV. Direct and indirect relations between perceived parental acceptance, perceptions of the self, and emotional adjustment during early adolescence. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal. 1996;25:159–183. [Google Scholar]

- Park HS, Bauer S. Parenting practices, ethnicity, socioeconomic status and academic achievement in adolescents. School Psychology International. 2002;23:386–396. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson J, Pryor J, Field J. Adolescent attachment to parents and friends in relation to aspects of self-esteem. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 1995;24:365–376. [Google Scholar]

- Paxton SJ, Schutz HK, Wertheim EH, Muir SL. Friendship clique and peer influences on body image concerns, dietary restraint, extreme weight-loss behaviors, and binge eating in adolescent girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1999;108:255–266. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.2.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SJ, White LK. Satisfaction with parenting: The role of marital happiness, family structure, and parents’ gender. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998;60:293–308. [Google Scholar]

- Seginer R, Vermulst A, Gerris J. Bringing up adolescent children: A longitudinal study of parents’ child-rearing stress. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2002;26:410–422. [Google Scholar]

- Shulman S, Collins WA, Dital M. Parent-child relationships and peer-perceived competence during middle childhood and preadolescence in Israel. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1993;13:204–218. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. We know some things: Parent-adolescent relationships in retrospect and prospect. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2001;11:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Adolescence. New York: McGraw Hill; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. New York: Harper Collins College; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Crocker J. Race and self-esteem: Meta-analyses comparing Whites, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, and American Indians and comment on Gray-Little and Hafdahl (2000) Psychological Bulletin. 2002;128:371–408. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.128.3.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. Table 1. Total population by age, race and Hispanic or Latino origin for the United States: 2000. 2001 Retrieved May 29, 2008, from http://www.census.gov/population/cen2000/phc-t9/tab01.pdf.

- Verschueren K, Marcoen A. Perceived security of attachment to mother and father: Developmental differences and relations to self-worth and peer relationships at school. In: Kerns KA, Richardson RA, editors. Attachment in Middle Childhood. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 212–230. [Google Scholar]