Abstract

Mounting evidence points to soluble peptide oligomers as the primary agents in various amyloid and prion diseases. Multiple mechanisms appear to contribute to the cytotoxic effects of these oligomers. Here, an additional, general mechanism is proposed. Hypothesis: soluble amyloid peptide oligomers serve as “all-purpose” beta strands that can interact with transiently unfolded or nascent proteins where interior beta sheet edges are exposed. The proteins, trapped in misfolded states through this interaction, become substrates for ubiquitination, targeting them for proteasomal degradation. The increased load of ubiquitinated proteins could contribute to the impairment of the ubiquitin/proteasome system (UPS) seen in many amyloid-related diseases. This “misfolding trap” mechanism could be especially stressful in the ER, where the amyloid oligomers would compete with chaperones for nascent beta sheet proteins. If the bound amyloid oligomer dissociates at some point after the misfolded protein is committed to the UPS pathway, the oligomer could then repeat the process, adding a catalytic aspect to the misfolding mechanism. Direct proof of this proposed mechanism requires detection of amyloid oligomer/beta-sheet protein complexes, and a co-immunoprecipitation experiment is proposed. This hypothesis supports therapies that increase amyloid oligomer degradation or sequestration, as well as therapies that upregulate chaperone activity, for combating amyloid-related diseases.

Keywords: misfolding diseases, soluble amyloid, prion, oligomer, complex, neurotoxicity, cytotoxicity, protein degradation, catalytic mechanism, beta sheet, therapies

INTRODUCTION

Amyloid and prion diseases, neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob diseases, and non-neural diseases such as type 2 diabetes and desmin-related cardiomyopathy, all involve insoluble aggregations of peptides consisting of fibrils with cross-beta sheet structure [1,2]. The aggregations can be manifested as “classic” extra-cellular amyloid plaques or intra-cellular aggresomes or inclusion bodies. While these aggregations can have deleterious effects [3,4], the severity of many amyloid-related diseases correlates only modestly with the amount of insoluble peptide aggregation; instead, disease severity correlates more closely with the levels of the corresponding soluble peptide oligomers [1,5].

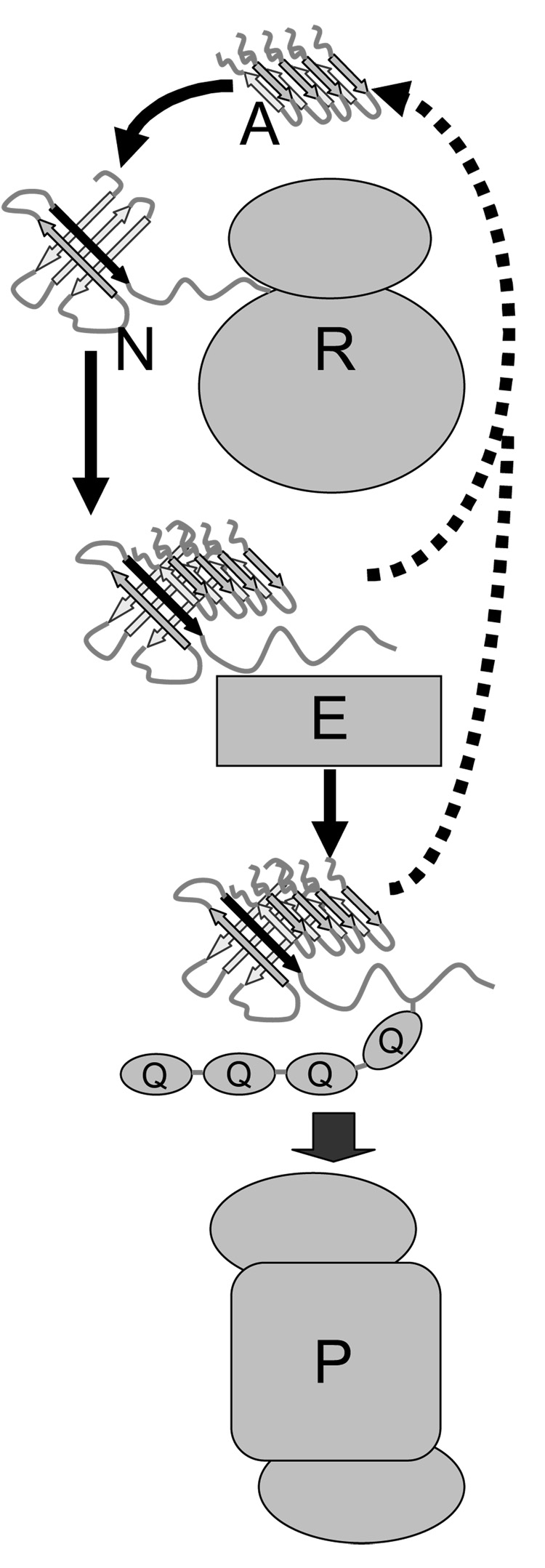

Considerable research on amyloid-related diseases now focuses on understanding how soluble oligomers of amyloid and prion peptides, hereafter called amyloid oligomers, bring about the observed cellular dysfunction and cytotoxicity [6–8]. For instance, in Alzheimer’s disease amyloid oligomers can disrupt ion homeostasis inside and outside the cell [9,10] and can interfere with the UPS [11–13]. Here a hypothesis for an additional general mechanism by which amyloid oligomers could contribute to cytotoxicity is proposed. The soluble oligomers might serve as “all-purpose” beta strands that can interact with transiently unfolded or nascent proteins where interior beta sheet edges are exposed. The proteins, trapped in misfolded states through this interaction, become substrates for ubiquitination, targeting them for proteasomal degradation (see figure). This “misfolding trap” mechanism could potentially act in concert with other deleterious amyloid and prion interactions, with proteasomes and chaperone proteins for example, ultimately overloading the UPS.

Figure. The misfolding trap hypothesis.

An amyloid oligomer, labeled ‘A’ at the top of the diagram, and shown here as a tetramer, though other multimeric states are possible, binds to an exposed interior beta sheet edge of a transiently misfolded protein, in this case a nascent protein ‘N’ emerging from a ribosome ‘R’, with the exposed interior beta strand shown in black. The nascent protein, unable to completely fold due to the bound amyloid oligomer, is recognized by an ubiquitin ligase ‘E’ as a misfolded protein and is poly-ubiquitinated, represented by the ovals labeled ‘Q’, here shown as a string of four, though longer poly-ubiquitin chains are possible. The poly-ubiquitinated protein is translocated to a proteasome ‘P’ for degradation. If the amyloid oligomer dissociates from the protein at some point after being committed to the UPS pathway, indicated by the dotted pathways, it could then encounter another misfolded protein and repeat the process.

Amyloid Oligomers and Protein Misfolding

Soluble amyloid oligomers are challenging to study due to their transient and often inhomogeneous nature. For example Aβ has been detected in dimer, trimer and higher multimeric forms [14,15]. Soluble monomers might also adopt cytotoxic forms, in poly-Q expansion diseases like Huntington’s, for example [16]. CD and fluorescence experiments suggest some amyloid oligomers adopt a secondary structure that is neither predominantly alpha helical nor beta strand [17,18]. Simulations of Aβ oligomers below the critical number needed to nucleate fibril formation show considerable amorphousness, though they still maintain a significant portion of the beta-sheet core [19]. Antibodies have been isolated that have cross-reactivity to multiple types of amyloid oligomers, “regardless of sequence,” suggesting they share a common structural motif [20]. Ultimately, the amyloid and prion peptides adopt beta strand structure as they bind to growing amyloid fibrils [2]. Because amyloid oligomers appear to undergo the same conformational change to beta strand despite their widely differing sequences, backbone interactions likely play a major role in the conformational transition.

If beta strand backbone interactions dominate the transition leading to amyloid fibril formation, perhaps amyloid oligomers might also be able to make similar interactions and bind to exposed beta sheets edges of non-amyloid proteins. Though it is not proven that the antibody interaction with amyloid oligomers occurs via backbone, beta-strand-like contacts, the observation of antibody cross-reactivity, in spite of the lack of sequence homology between the amyloid peptides, is consistent with this notion [20]. Exposure of normally buried interior beta sheet edges likely plays a major role in protein aggregation [21]. Indeed, exterior beta sheet edges appear to have undergone evolutionary pressure to prevent such aggregation [22]. Protecting exposed interior beta sheet edges is presumably an important function of chaperones; thus, the misfolding trap hypothesis implies chaperones and amyloid oligomers might compete in the cell for misfolded proteins.

Even though backbone interactions might dominate the binding of amyloid oligomers to exposed beta sheet edges of misfolded, non-amyloid proteins, side chain interactions could modulate the affinity [23]. For example, complementary hydrophobic contacts could enhance binding while side chain steric clashes could inhibit binding. For Aβ hydrophobic side chain interactions are proposed to play a major role in fibril nucleation, whereas for poly-Q peptides hydrophilic side chain interactions appear to dominate [19,24]. So while the misfolding trap hypothesis proposes that backbone beta strand interactions play a major role, different amyloid peptide sequences might preferentially bind exposed beta strands of different misfolded proteins, which, in turn, could lead to varying pathologies in the cell [25].

Protein Misfolding in the ER

According to the misfolding trap hypothesis, wherever amyloid oligomers encounter transiently misfolded proteins with exposed beta sheet edges, the oligomers can potentially bind and trap the proteins in their misfolded form. Nascent proteins in the process of emerging from ribosomes might be particularly vulnerable to being trapped, so the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) could be a major site of amyloid and prion induced stress in the cell [26–28]. Amyloid oligomers have been detected in the ER, and how they get there is under investigation; they might be made in the ER itself [29] or reach the ER through diffusion or translocation after post-translational processing [30]. Despite cytosolic chaperones and numerous chaperones in the ER, as much as 30% of nascent proteins become tagged for destruction in the UPS [31]. Any increase in unfolded protein due to small amounts of amyloid oligomers competing with chaperones might be insignificant, at least initially. More direct mechanisms of ‘gumming’ up the UPS by amyloid and prion peptides have been proposed, either directly with proteolysis in the proteasome or with delivery of ubiquitinated proteins to the proteasome [11–13,32–34].

As cells age, the level of ubiquitinated protein increases, and amyloid levels also increase, in part due to reduced activity of endogenous proteases for which amyloid peptides are substrates [35–38]. Rising levels of soluble amyloid oligomers might lead to more effective competition with chaperones and help drive the increase in load of misfolded proteins in the UPS. Association of amyloid oligomers with misfolded, ubiquitinated protein targeted for proteasomal degradation could facilitate delivery of amyloid to proteasomes. However, if the amyloid oligomer is bound relatively weakly and dissociates at some point after the misfolded protein has become committed to the UPS pathway, the oligomer could then bind a new misfolded protein and repeat the process, adding a “catalytic” aspect to the misfolding mechanism (see figure).

In amyloid-induced proteasomal dysfunction the oligomer/proteasome association is stoichiometric [34], and how long-term exposure to low levels of amyloid oligomer would lead to disease via this mechanism is unclear. The catalytic aspect of the misfolding trap mechanism could help explain the long-term cumulative damage incurred by soluble amyloid oligomers. Ultimately, the increased load of misfolded proteins targeted for proteasomal degradation could act in concert with any direct interference with the UPS, increasing stress to the cell and contributing to apoptosis [28].

In Alzheimer’s disease soluble amyloid oligomers are associated with dysregulation of calcium homeostasis, both with the extracellular medium and within the cell. This effect might be caused by interaction with calcium channel proteins or directly through permeabilization of the membrane by the amyloid oligomers [15]. Short-circuiting the ER/cytosol calcium gradient could reduce chaperone activity since several calcium-dependent chaperone proteins in the ER only function at high calcium concentrations [26]. However, calcium dysregulation alone cannot fully account for Aβ toxicity [39]. Perhaps Aβ oligomers increase the load of misfolded proteins by the two mechanisms acting in synergy, by trapping nascent proteins in misfolded states, and by reducing the activity of competing chaperone proteins.

Experimental Evidence for Amyloid Complexes with Misfolded Proteins

Direct evidence of soluble amyloid oligomers acting as traps for misfolded proteins requires detection of complexes of the oligomers with misfolded proteins. Currently, no such experimental evidence exists. Most amyloid and prion aggregations consist primarily of the corresponding peptide, though in desmin-related cardiomyopathy the aggresomes consist of two proteins, desmin and αB crystallin [40]. The amyloid peptides in the fibrils can have undergone considerable modification, including ubiquitination, and the aggregations can be co-localized with chaperone proteins of the Hsp-16 and Hsp70 families, as well as proteasome components [41–43]. Poly-Q peptide aggresomes appear to have the largest number of associated proteins [44]. Perhaps for many amyloid oligomers, the binding of a misfolded protein precludes binding to amyloid fibrils or blocks additional fibril growth until the misfolded protein is released. The fact that amyloid peptides form stable fibrils in vivo suggests that amyloid peptides interact more strongly with themselves than with other proteins, that is, their self-interaction is expected to be stronger than any non-self interaction. This weaker, non-self interaction is consistent with the proposed catalytic aspect of the misfolding trap mechanism.

The strongest, though still indirect, evidence for the misfolding trap hypothesis comes from a study of poly-Q proteins expressed in C. elegans containing various temperature-sensitive mutant proteins [45]. Expression of poly-Q proteins in these mutants led to increased abnormal development related to the particular mutant protein at normally permissive temperatures. The implication is that since temperature sensitive proteins are less stable and more likely to experience transient unfolding, the poly-Q proteins have a better chance of trapping them. However, other mechanisms are possible, such as poly-Q proteins binding and interfering with, or somehow downregulating, chaperone proteins essential to the temperature sensitive mutant proteins. In summary, this important study demonstrates how poly-Q proteins can compromise “cellular folding homeostasis;” [45] the misfolding trap mechanism provides a possible physical explanation that might explain their findings.

A co-immunoprecipitation experiment could be designed to directly detect complexes of amyloid oligomers with misfolded proteins. First lysate from soluble oligomer transfected cells could be run through a column with immobilized antibody for the particular oligomer [20]. Alternatively, amyloid or prion peptides engineered to contain a peptide affinity tag sequence could be used, as long as the tag is confirmed to not affect oligomer behavior [46]. By using a tag including a cleavage site, the immobilized complexes could be cleaved and eluted, and run through a second column, one with immobilized ubiquitin antibody for instance. The resulting column eluates could then be examined by standard chromatographic and mass spectroscopic techniques.

Performing the experiment on cell lines with temperature sensitive mutations might be especially instructive. In the example outlined above, eluate from the first column could be compared chromatographically with that from the second column; a large difference might indicate the amyloid oligomers interact significantly with non-ubiquitinated protein components, chaperones for instance. Of course many complications are likely. The majority of proteins “trapped” by the amyloid oligomers could be at such low concentrations in the eluate that their chromatographic detection might be problematic. Also, the amyloid epitope might be blocked in the putative complexes, the amyloid oligomers could themselves be ubiquitinated [41,42], and preparation of the lysate could bring about complexes not normally present in the cell.

Implications for Amyloid Disease Therapy

Reducing amyloid oligomer levels as a therapeutic goal obviously follows from the misfolding trap hypothesis. Promoting oligomer sequestration in amyloid aggregations and upregulating proteases that degrade the peptides both could reduce soluble oligomer levels; however, most therapeutic strategies, especially for Alzheimer’s disease, focus on preventing their post-translational creation [47–49] and mitigating calcium dysregulation [50,51].

Upregulating chaperone activity, particularly in the ER, is another therapeutic goal that follows from the misfolding trap hypothesis [52–56]. If experiments, such as described above, show evidence of interaction between particular chaperone proteins and the soluble oligomers, then boosting the amounts of the chaperone proteins in the cell could lead to more oligomers being bound. This could help reduce other deleterious amyloid or prion interactions in the cell, while at the same time the boosted levels should make the chaperone proteins more available to their normal substrates. If, instead, experiments show the amyloid oligomers acting primarily as misfolding traps, boosting levels of chaperone proteins could help them compete with the oligomers for transiently unfolded proteins. Even if the misfolding trap mechanism proves true, it might only contribute to cytotoxicity in a subset of amyloid-related diseases. Still, the experiments described here should clarify the importance of chaperone proteins in developing amyloid-related disease therapies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author thanks P. Boon Chock, Ann Ginsburg, Lois E. Greene, and Evan Eisenberg for their helpful suggestions. This work was supported intramurally by the National Heart, Lung & Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health

Abbreviations

- UPS

ubiquitin/proteasome system

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- poly-Q

polyglutamine

- Aβ

amyloid beta

References

- 1.Stefani M, Dobson CM. Protein aggregation and aggregate toxicity: new insight into protein folding, misfolding diseases and biological evolution. J Mol Med. 2003;81:678–699. doi: 10.1007/s00109-003-0464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sawaya MR, Sambashivan S, Nelson R, Ivanova MI, Sievers SA, Apostol MI, Thompson MJ, Balbirnie M, Wiltzius JJW, McFarlane HT, Madsen AO, Riekel C, Eisenberg D. Atomic structures of amyloid cross-β spines reveal varied steric zippers. Nature. 2007;447:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Knowles RB, Wyart C, Buldyrev SV, Cruz L, Urbanc B, Hasselmo ME, Stanley HE, Hyman BT. Plaque-induced neurite abnormalities: Implications for disruption of neural networks in Alzheimer’s disease. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:5274–5279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.5274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Novitskaya V, Bocharova OV, Bronstein I, Baskarov IV. Amyloid fibrils of prion protein are highly toxic to cultured cells and primary neurons. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:13828–13836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511174200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferreira ST, Vieira MNN, De Felice FG. Soluble protein oligomers as emerging toxins in Alzheimer’s and other amyloid diseases. IUBMB Life. 2007;59:332–345. doi: 10.1080/15216540701283882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh DM, Selkoe DJ. A beta oligomers – a decade of discovery. J Neurochem. 2007;101:1172–1184. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04426.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Agorogiannis EI, Agorogiannis GI, Papadimitriou A, Hadjigeorgiou GM. Protein misfolding in neurodegenerative diseases. Neuropath Appl Neurobiol. 2004;30:215–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2004.00558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meredith SC. Protein denaturation and aggregation – Cellular responses to denatured and aggregated proteins. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2005;1066:181–221. doi: 10.1196/annals.1363.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollard HB, Arispe N, Rojas E. Ion channel hypothesis for Alzheimer amyloid peptide neurotoxicity. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 1995;15:513–526. doi: 10.1007/BF02071314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kagan BL, Hirakura Y, Azimov R, Azimova R, Lin MC. The channel hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: current status. Peptides. 2002;23:1311–1315. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(02)00067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gregori L, Hainfeld JF, Simon MN, Goldgaber D. Binding of amyloid beta protein to the 20 S proteasome. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:58–62. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keller JN, Hanni KB, Markesbery WR. Impaired proteasome function in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem. 2000;75:436–439. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen QH, Liu JB, Horak KM, Zheng HQ, Kumarapeli ARK, Li J, Li FQ, Gerdes AM, Wawrousek EF, Wang XJ. Intrasarcoplasmic amyloidosis impairs proteolytic function of proteasomes in cardiomyocytes by compromising substrate uptake. Circ Res. 2005;97:1018–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000189262.92896.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Deshpande A, Mina E, Glabe C, Busciglio J. Different conformations of amyloid beta induce neurotoxicity by distinct mechanisms in human cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6011–6018. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1189-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Watson D, Castano E, Kokjohn TA, Kuo YM, Lyubchenko Y, Pinsky D, Connolly ES, Jr, Esh C, Luehrs DC, Stine WB, Rowse LM, Emmerling MR, Roher AE. Physicochemical characteristics of soluble oligomeric Aβ and their pathologic role in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurolog Res. 2005;27:869–881. doi: 10.1179/016164105X49436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagai Y, Inui Y, Popiel HA, Fujikake N, Hasegawa K, Urade Y, Goto Y, Naiki H, Toda T. A toxic monomeric conformer of the polyglutamine protein. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:332–340. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang THJ, Yang DS, Plaskos NP, Go S, Yip CM, Fraser PE, Chakrabartty A. Structural studies of soluble oligomers of the Alzheimer beta-amyloid peptide. J Mol Biol. 2000;297:73–87. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.3559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dusa A, Kaylor J, Edridge S, Bodner N, Hong DP, Fink AL. Characterization of oligomers during α-synuclein aggregation using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Biochemistry. 2006;45:2752–2760. doi: 10.1021/bi051426z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fawzi NL, Okabe Y, Yap EH, Head-Gordon T. Determining the critical nucleus and mechanism of fibril elongation of the Alzheimer’s Aβ1–40 peptide. J. Mol. Biol. 2007;365:535–550. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kayed R, Glabe CG. Conformation-dependent anti-amyloid oligomer antibodies. Science. 2003;300:486–489. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jahn TR, Radford SE. Folding versus aggregation: polypeptide conformations on competing pathways. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;469:100–117. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2007.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Richardson JS, Richardson DC. Natural β-sheet proteins use negative design to avoid edge-to-edge aggregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2754–2759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052706099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajan RS, Illing ME, Bence NF, Kopito RR. Specificity in intracellular protein aggregation and inclusion body formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:13060–13065. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181479798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perutz MF, Johnson T, Suzuki M, Finch JT. Glutamine repeats as polar zippers: their possible role in inherited neurodegenerative diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5355–5358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyer-Luehmann M, Coomaraswamy J, Bolmont T, Kaeser S, Schaefer C, Kilger E, Neuenschwander A, Abramowski D, Frey P, Jaton AL, Vigouret JM, Paganetti P, Walsh DM, Matthews PM, Ghiso J, Staufenbiel M, Walker LC, Jucker M. Exogenous induction of cerebral beta-amyloidogenesis is governed by agent and host. Science. 2006;313:1781–1784. doi: 10.1126/science.1131864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghribi O. The role of the endoplasmic reticulum in the accumulation of β-amyloid peptide in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:119–133. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hetz C, Castilla J, Soto C. Perturbation of endoplasmic reticulum homeostasis facilitates prion replication. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:12725–12733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611909200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang X, Robbins J. Heart failure and protein quality control. Circ Res. 2006;99:1315–1328. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000252342.61447.a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cook DG, Forman MS, Sung JC, Leight S, Kolson DL, Iwatsubo T, Lee VMY, Doms RW. Alzheimer’s Aβ(1–42) is generated in the endoplasmic reticulum/intermediate compartment of NT2N cells. Nature Med. 1997;3:1021–1023. doi: 10.1038/nm0997-1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schmitz A, Schneider A, Kummer MP, Herzog V. Endoplasmic reticulum-localized amyloid β-peptide is degraded in the cytosol by two distinct degradation pathways. Traffic. 2004;5:89–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2004.00159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schubert U, Anton LC, Gibbs J, Norbury CC, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Rapid degradation of a large fraction of newly synthesized proteins by proteasomes. Nature. 2000;404:770–774. doi: 10.1038/35008096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gregori L, Fuchs C, Figueiredo-Pereira ME, Van Nostrand WE, Goldgaber D. Amyloid β-protein inhibits ubiquitin-dependent protein degradation in vitro. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19702–19708. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holmberg CI, Staniszewski KE, Mensah KN, Matouschek A, Morimoto RI. Inefficient degradation of truncated polyglutamine proteins by the proteasome. EMBO J. 2004;23:4307–4318. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kristiansen M, Deriziotis P, Dimcheff DE, Jackson GS, Ovaa H, Naumann H, Clarke AR, van Leeuwen FWB, Menendez-Benito V, Dantuma NP, Portis JL, Collinge J, Tabrizi SJ. Disease-associated prion protein oligomers inhibit the 26S proteasome. Mol Cell. 2007;26:175–188. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shang F, Dudek E, Liu Q, Boulton ME, Taylor A. Protein quality control by the ubiquitin proteolytic pathway: roles in resistance to oxidative stress and disease. Israel J. Chem. 2006;46:145–158. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sherman MY, Goldberg AL. Cellular defenses against unfolded proteins. A cell biologist thinks about neurodegenerative diseases. Neuron. 2001;29:15–32. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00177-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Perez A, Morelli L, Cresto JC, Castano EM. Degradation of soluble amyloid beta-peptides 1–40, 1–42, and the Dutch variant 1–40Q by insulin degrading enzyme from Alzheimer disease and control brains. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:247–255. doi: 10.1023/a:1007527721160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yasojima K, Akiyama H, McGeer EG, McGeer PL. Reduced neprilysin in high plaque areas of Alzheimer brain: a possible relationship to deficient degradation of beta-amyloid peptide. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297:97–100. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01675-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suen KC, Lin KF, Elyaman W, So KF, Chang RCC, Hugon J. Reduction of calcium release from the endoplasmic reticulum could only provide partial neuroprotection against beta-amyloid peptide toxicity. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1413–1426. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2003.02259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goldfarb LG, Vicart P, Goebel HH, Dalakas MC. Desmin myopathy. Brain. 2004;127:723–734. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cummings CJ, Mancini MA, Antalffy B, DeFranco DB, Orr HT, Zoghbi HY. Chaperone suppression of aggregation and altered subcellular proteasome localization imply protein misfolding in SCA1. Nature Genet. 1998;19:148–154. doi: 10.1038/502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Perry G, Friedman R, Shaw G, Chau V. Ubiquitin is detected in neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaque neurites of Alzheimer disease brains. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3033–3036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.9.3033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fonte V, Kapulkin V, Taft A, Fluet A, Friedman D, Link CD. Interaction of intracellular β amyloid peptide with chaperone proteins. Proc Nat Adad Sci USA. 2002;99:9439–9444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152313999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suhr ST, Senut MC, Whitelegge JP, Faull KF, Cuizon DB, Gage FH. Identities of sequestered proteins in aggregates from cells with induced polyglutamine expression. J Chem Biol. 2001;153:283–294. doi: 10.1083/jcb.153.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gildalevitz T, Ben-Zvi A, Ho KH, Brignull HR, Morimoto RI. Progressive disruption of cellular protein folding in models of polyglutamine diseases. Science. 2006;311:1471–1474. doi: 10.1126/science.1124514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mukai H, Isagawa T, Goyama E, Tanaka S, Bence NF, Tamura A, Ono Y, Kopito RR. Formation of morphologically similar globular aggregates from diverse aggregation-prone proteins in mammalian cells. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:10887–10892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409283102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussain I, Hawkins J, Harrison D, Hille C, Wayne G, Cutler L, Buck T, Walter D, Demont E, Howes C, Naylor A, Jeffrey P, Gonzalez MI, Dingwall C, Michel A, Reshaw S, Davis JB. Oral administration of a potent and selective non-peptidic BACE-1 inhibitor decreases beta-cleavage of amyloid precursor protein and amyloid-beta production in vivo. J Neurochem. 2007;100:802–809. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.04260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sadowski MJ, Pankiwicz J, Scholtzova H, Mehta PD, Prelli F, Quartermain D, Wisniewski T. Blocking the apolipoprotein E/amyloid-beta interaction as a potential therapeutic approach for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:18787–18792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604011103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evin G, Sernee MF, Masters CL. Inhibition of gamma-secretase as a therapeutic intervention for Alzheimer’s disease – prospects, limitations and strategies. CNS Drugs. 2006;20:351–372. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200620050-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chan CS, Guzman JN, Ilijic E, Mercer JN, Rick C, Tkatch T, Meredith GE, Surmeier DJ. ‘Rejuvenation’ protects neurons in mouse models of Parkinson’s disease. Nature. 2007;447:1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/nature05865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mattson MP. Calcium and neurodegeneration. Aging Cell. 2007;6:337–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2007.00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muchowski PJ, Wacker JL. Modulation of neurodegeneration by molecular chaperones. Nature Rev Neurosci. 2005;6:11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrn1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoshino T, Nakaya T, Araki W, Suzuki K, Suzuki T, Mizushima T. Endoplasmic reticulum chaperones inhibit the production of amyloid-beta peptides. Biochem. J. 2007;402:581–589. doi: 10.1042/BJ20061318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sanbe A, Osinska H, Villa C, Gulick J, Klevitsky R, Glabe CG, Kayed R, Robbins J. Reversal of amyloid-induced heart disease in desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Proc Nat Acad Sci. 2005;102:13592–13597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503324102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barral JM, Broadley SA, Schaffar G, Hartl FU. Roles of molecular chaperones in protein misfolding diseases. Seminars in Cell & Dev Biol. 2004;15:17–29. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2003.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zobel ATC, Loranger A, Marceau N, Theriault JR, Lambert H, Landry J. Distinct chaperone mechanisms can delay the formation of aggresomes by the myopathy-causing R120G alpha B-crystallin mutant. Human Mol Genet. 2003;12:1609–1620. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]