Abstract

Background. Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) has seen a dramatic rise in the USA over the last 30 years. Unresectable disease is present in 80–90% of patients, for which radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is an option. The aim of this study is to report the long-term survival after laparoscopic RFA. Methods. This is a prospective analysis of 104 patients who underwent 122 ablations for unresectable HCC from April 1997 to December 2006 at a tertiary care center. Overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS) were calculated using Kaplan–Meier curves, excluding 11 patients who subsequently underwent liver transplantation. Patients were analyzed using Child-Pugh classification, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging and various clinical parameters. Results. Median (range) data: age 63 years (41–81), lesion size 3.5 cm (1–10), number of lesions 1 (1–5), AFP 26.5 ng/ml (3.7–43588.5) and time from diagnosis to RFA 2 months (mos) (1–42). The median Kaplan–Meier survival for all patients was 26 mos (OS) while DFS was 14 mos. Univariate analysis demonstrated improved OS for the absence vs. presence of ascites (31 vs. 15 mos, p=0.003), Bilirubin <2 mg/dl vs. ≥2 mg/dl (27 vs. 19 mos, p=0.01), AFP <400 vs. ≥400 (29 vs. 13 mos, p<0.0001) and Child-Pugh Grade (A = 28, B = 15, C = 5 mos, p=0.01). Significant factors for improved DFS: absence vs. presence of ascites (16 vs. 5 mos, p=0.02), Bilirubin <2 vs. ≥2 (14 vs. 5 mos, p=0.0278), AFP <400 vs. ≥400 (15 vs. 4 mos, p=0.0025), Child-Pugh Grade (A = 16, B = 10, C = 3 mos, p=0.03). Patient age, largest tumor size, number of lesions, INR and albumin did not reach clinical significance. Three and five-year actual survival rates are 21% and 8.3%, respectively. Conclusions. Our study suggests that RFA may have a positive impact on survival for unresectable HCC. It also determines which patients fare best after RFA, by determining predictive factors that improve their survival.

Keywords: radiofrequency ablation, hepatocellular cancer, long-term outcomes

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common malignancies worldwide and is among the three most common causes of cancer death 1,2,3,4. Although traditionally HCC was more prevalent in eastern societies, it has witnessed an expontenial growth in the USA. The most common etiology remains viral hepatitis B or C and alcoholic liver disease 5. Current estimates of the prevalence of hepatitis C virus (HCV) in the USA are 2.7 million, with approximately 6000 new cases of HCC diagnosed per year 6. Proven treatment modalities with good long-term survival and low recurrence rates are liver transplantation and surgical resection. However, only a small percentage of patients are candidates for these therapies (10–25%) 7,8.

Management of patients with HCC is complex and is a therapeutic challenge for the transplant team, medical oncologists, and surgeons. Although liver transplant and surgical resection remain the gold standard, very few patients are amenable to this approach. More than 75% of patients have extensive disease or severe medical comorbidities, such as late stage cirrhosis, that exclude them from surgical transplantation or resection. Traditionally, this subset of patients is offered locopalliative vs. systemic chemotherapy or ablative therapies.

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is gaining increased acceptance for the local control of both primary and metastatic liver tumors. The overall morbidity and mortality associated with laparoscopic RFA for HCC remains exceedingly low. We previously reported on the short-term results of laparoscopic RFA for unresectable HCC 6. The aim of this study is to report our long-term outcomes of RFA for unresectable HCC, as well as to determine factors that may predict survival.

Patients and methods

This is a prospective study of patients undergoing RFA for unresectable HCC. Patients were accrued at the University of California–San Francisco and the Cleveland Clinic, between April 1997 and October 2006. This study was approved by the institutional review board, and informed consent was obtained from all patients before enrollment.

A total of 701 RFAs were performed during this period. Of these 701 ablations, 122 (17.4%) were for unresectable HCC. This study is comprised of 104 consecutive patients who underwent 122 ablations. Employing a multidisciplinary approach, patients were evaluated by medical oncology, hepatobiliary and transplant surgery, radiology, and the RFA team. Patients that were ultimately referred for RFA were not candidates for transplantation and deemed unresectable due to the extent or location of disease or coexistent comorbidities, such as cirrhosis, that limited their ability to undergo an extensive resection. Eleven patients post ablation were deemed candidates for liver transplantation and underwent transplantation. As such these 11 patients were excluded from long-term survival analysis.

Although patients with up to 10 lesions with a maximum diameter of 10 cm, as well as those with limited or no extrahepatic diseases were treated in the beginning of this study, subsequently we developed the following inclusion criteria: tumor size <7 cm, number of lesion <7, less than 20% of liver volume involved with tumor, absence of biliary dilatation and no or limited extrahepatic disease. Pre- and postoperative data were collected for analyses. Preoperative CT scans and bloodwork (complete blood count, liver function tests, basic chemistry, PT/PTT/INR and AFP) were performed within 1 week of the ablations. RFA was performed laparoscopically under ultrasound guidance. Technical considerations have previously been published by Siperstein et al. and will not be reiterated within this paper 25. Patients were typically monitored overnight and discharged home the next day after surgery. Tri-phasic liver CT scans and labs were repeated at 1 week and every 3 months thereafter in follow-up.

Data was analyzed using JMP statistical software 5.1.2. To identify prognostic factors, the following variables were analyzed: age, sex, stage of initial presentation, number of liver lesions, size of dominant lesion, presence and location of extrahepatic disease, initial vs. redo ablation, degree of ascites, encephalopathy, hepatitis, cirrhosis, AFP, bilirubin, Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer Group Stage (BCLC), and Child-Pugh Classification. Analyses were performed with the data as continuous variables and divided into defined categories (ordinal data) as supported by current literature standards. Univariate Kaplan–Meier analyses were performed, and if p≤0.15, these factors were analyzed using multivariate Cox proportional hazards model. Actual and actuarial survival analyses were also performed using Kaplan–Meier for overall survival (OS) and disease-free survival (DFS).

Results

One hundred and four patients underwent 122 RFA sessions between April 1997 and December 2006 for unresectable HCC. The mean age was 62±1.0 (mean±standard error of the mean with a 95% confidence interval), (range = 41–81). Patients presented with an average of 1.6±0.1 lesions (1–5) measuring 3.8±0.15 cm (1–10 cm).

The median time frame from diagnosis of HCC to RFA was 5.9 months (1–42). The underlying etiology of hepatitis was as follows: 53% of the patients were infected with HCV, 12% with hepatitis B virus (HBV), 22% alcoholic-induced hepatitis, 11% idiopathic hepatitis, 2% other causes (which include autoimmune hepatitis, hemochromatosis, etc).

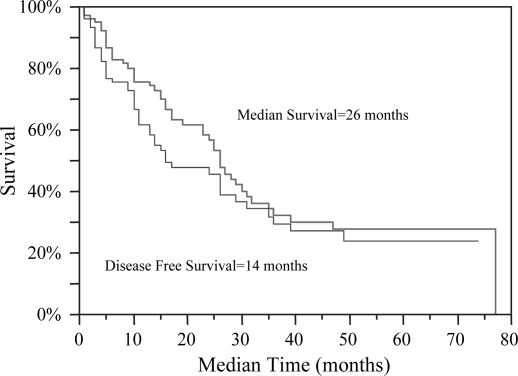

Patients were followed from enrollment in the study until December 2006. The following endpoints were noted: progression of ablated disease, evidence of new hepatic or extrahepatic disease, and death. The median follow-up was 23 months ranging from 1 to 83 months, calculated from time of ablation to death or analysis of the data in December 2006. Actual and actuarial analyses were compared. Three and five-year actual survival rates are 21 and 8.3% respectively. Kaplan–Meier analyses demonstrate a median survival of 26 months post RFA with an overall median DFS of 14 months (Figure 1). When extrapolating recurrence data, the median time to recurrence of a previously ablated lesion was 10.5 months, while median time to evidence of new liver lesions was 11 months (p=ns). Survival data was further analyzed according to preoperative BCLC staging: A1 (median survival data unreached), A2 (31 months), A3 (26 months), A4 (23 months), B (25 months), C (−). Disease-free data was also further analyzed by BCLC staging: A1 (24 months), A2 (31 months), A3 (11 months), A4 (9 months), B (11 months), C (−), p=0.43 (Table I).

Figure 1. .

Kaplan–Meier analyses demonstrate a median survival of 26 months post RFA, for patients that were not candidates for transplantation and deemed unresectable. The overall disease-free survival was 14 months.

Table I. Preoperative laboratory data and Barcelona-Clinic Liver Cancer Staging was analyzed to determine survival data and disease-free survival data.

| Overall survival | p-Value | Disease-free survival | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cohort | 26 | 14 | ||

| BCLC A1 | a | a | ||

| BCLC A2 | 31 | 31 | ||

| BCLC A3 | 26 | ns | 11 | ns |

| BCLC A4 | 23 | 9 | ||

| BCLC B | 25 | 14 | ||

| BCLC C | b | b | ||

| Size <3 cm | 26 | 12 | ||

| Size 3–5 cm | 26 | ns | 16 | ns |

| Size >5 cm | 25 | 14 | ||

| Number of Lesions <3 | 26 | ns | 17 | ns |

| Number of Lesions ≥3 | 27 | 11 | ||

| Child-Pugh Grade A | 28 | 16 | ||

| Child-Pugh Grade B | 15 | 0.01 | 10 | 0.03 |

| Child-Pugh Grade C | 5 | 3 | ||

| AFP<400 | 29 | 0.002 | 15 | 0.0001 |

| AFP≥400 | 13 | 4 | ||

| No Ascites | 31 | 0.003 | 38 | 0.02 |

| Ascites | 15 | 16 | ||

| Bilirubin <2 (mg/dl) | 27 | 0.01 | 14 | 0.03 |

| Bilirubin ≥2 (mg/dl) | 19 | 5 |

Note: Child-Pugh Grade, AFP, ascites, and bilirubin levels all proved to be statistically significant indicators of survival.

aMedian survival was not reached among this cohort.

bNo patients with BCLC Grade C underwent RFA in this study.

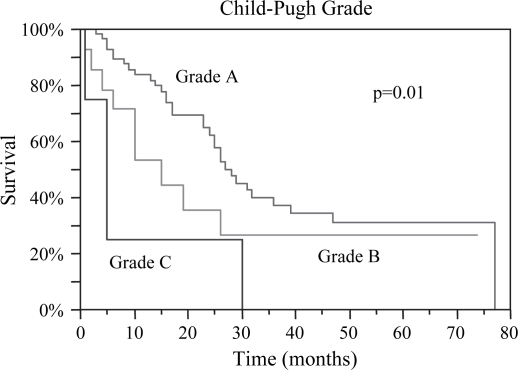

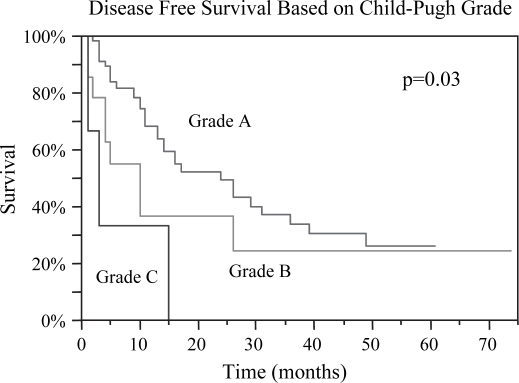

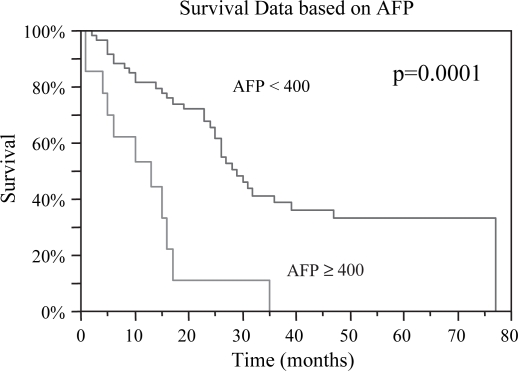

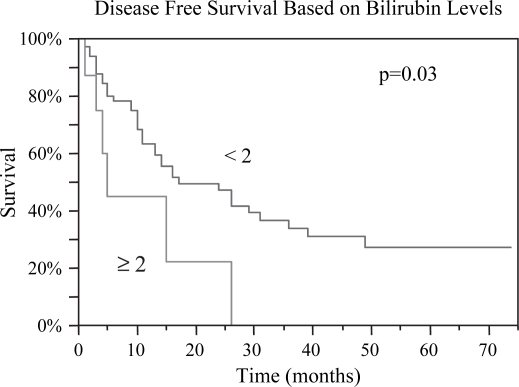

Preoperative data deemed to be predictive of prognosis were evaluated. Median OS was 26, 26, and 25 months for lesions <3, 3–5, and >5 cm, respectively, p=0.93. DFS based on lesion size was 12, 16, and 14 months respectively, p=0.71 (Table I). There was no difference in OS or DFS between patients with < or ≥3 lesions; OS 26 vs. 27 months (p=ns) and DFS 17 vs. 11 months (p=ns). Child-Pugh Grade A patients had the best OS of 28 months with a DFS of 16 months, while Grade C patients had the worst OS of 5 months and DFS of 3 months, p=0.01 and p=0.03, respectively (Figures 2 and 3). Patients with AFP levels <400 fared significantly better than those with levels ≥400, OS 29 months vs. 13 months (p=0.002) and DFS 15 months vs. 4 months (p=0.0001) (Figures 4 and 5). The presence of ascites also had a significantly negative impact on OS 15 months vs. 31 months (p=0.003), and DFS 5 months vs. 16 months (p=0.02) (Figures 6 and 7). Patients with bilirubin levels <2 had significantly improved OS of 27 months vs. 19 months (p=0.01) and DFS 14 months vs. 5 months (p=0.02) (Figures 8 and 9).

Figure 2. .

Overall survival was statistically different based on preoperative Child-Pugh Grade. Grade A patients demonstrated the best median survival of 28 months; Grade B, 15 months; and Grade C, 5 months, p=0.01.

Figure 3. .

Disease-free survival was also noted to be statistically different among the Child-Pugh grades: Grade A, 16 months; Grade B, 10 months; Grade C, 3 months, p=0.03.

Figure 4. .

Patients with preoperative AFP < 400 had significantly improved median overall survival compared to those with levels ≥400, 29 vs. 13 months, respectively, p=0.0001.

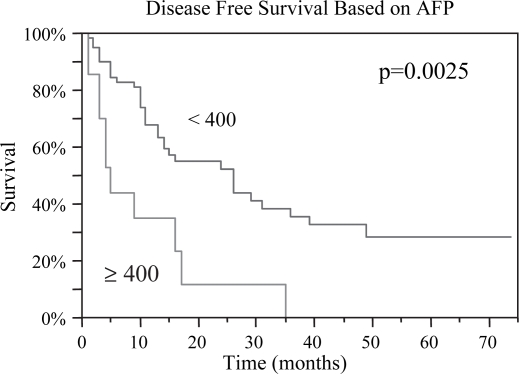

Figure 5. .

Similar to overall survival, disease-free survival was significantly improved for patients with AFP < 400 preoperatively, 15 vs. 4 months, p=0.0025.

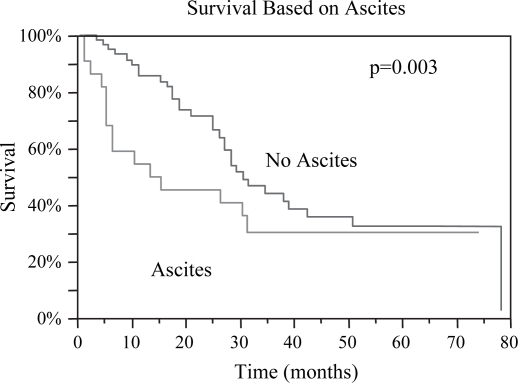

Figure 6. .

Patients without any preoperative evidence of ascites had improved median overall survival post RFA compared to those with ascites: 31 months vs. 15 months, p=0.003.

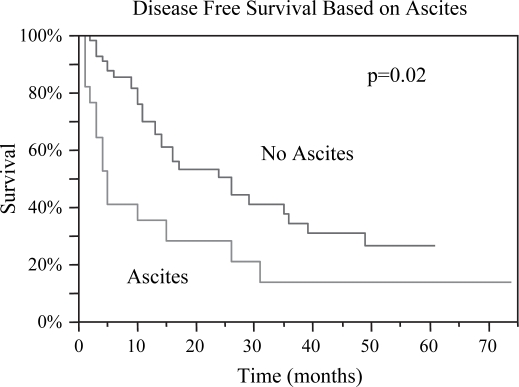

Figure 7. .

Disease-free survival was markedly greater for those without ascites, 16 vs. 5 months, p=0.02.

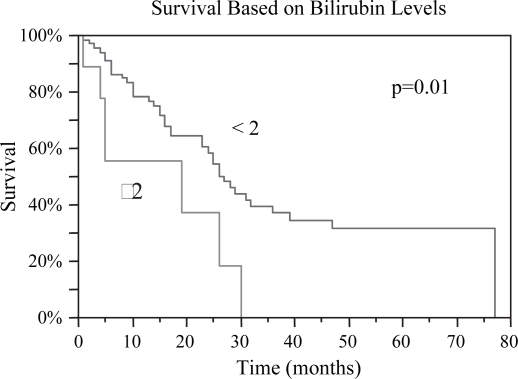

Figure 8. .

Patients with preoperative bilirubin levels <2 had a statistically greater median survival post RFA, 27 vs. 19 months, p=0.01.

Figure 9. .

Patients with bilirubin level <2 pre RFA demonstrated both improved overall and disease-free survival. The disease-free survival for those with bilirubin <2 was 14 months vs. 5 months for those ≥2, p=0.03.

When recurrence data was analyzed based on site of first recurrence, it was seen that the time to recurrence of new liver disease was 14.6 months, progression of ablated disease 14 months, and overall DFS 14 months (Table I and Figure 1).

The exact cause of death was available for 47 patients. Of the patients 38.3% died of liver failure, 25.5% of extrahepatic progression of disease, and 38.3% of other unrelated causes.

Discussion

Although current literature suggests a survival benefit of RFA for selected cases of HCC, long-term data remains scant 9,10,11,12. The present study examines both long-term overall and DFS of HCC patients post ablation. Predictors of OS and DFS were also identified. In this series, patients offered ablation were not candidates for transplantation and deemed unresectable.

The natural progression of HCC is short, with a 3-year survival rate of only 12% 13. The median survival of all patients with HCC in the SEER database between 1992 and 1996 was equally poor, 0.6 years 14. Although transplantation remains the most effective and potentially curative option, most patients are not candidates. Of those patients amenable to transplantation, limited availability of donor organs makes liver transplantation difficult and resection a viable alternative 15,16,17,18,19. Despite significant improvements in liver resection technique, the prognosis remains poor with 5-year OS rates of 33–44% and 5-year cumulative recurrence rates of 80–100% 15.

When patients are not candidates for transplantation and not amenable to undergo resection, alternatives include local ablation and or local vs. systemic chemotherapy. The standard regimen of systemic doxorubicin has been well studied and infers a median survival of 6 months 20. The overall median survival post ablation was 26 months, and the DFS 14 months. A direct comparison of survival rates across treatment modalities is not possible, as the exclusion criteria varies. This cohort of patients undergoing RFA is encouraging.

Until recently, no consensus existed for patients with unresectable HCC. The North American Hepatobiliary Task Force, consisting of medical oncologists, radiologists, and surgeons was recently formed to approach this complex issue with a multidisciplinary approach 20. Options for this subset of patients include transarterial embolization vs. transarterial chemoembolization. A meta-analyses of embolization studies conferred a significant survival advantage 26,27. For those patients that have contraindications to chemoembolization or progress despite treatment, may consider arterial administration of yttrium-90-impregnated glass or resin microspheres 20. A well-accepted alternative treatment option for HCC is percutaneous injection of ethanol. Despite improved survival, the high rate of recurrence (50% in 2 years) has led investigators to examine alternative treatments 23.

A number of studies have attempted to identify predictors of survival post ablation. These include both tumor and patient characteristics. Guglielmi et al. outlined and directly compared seven different staging systems for cirrhotic patients with HCC who underwent RFA. They identified the BCLC staging system to offer greater validity and prognostic power 21. In this series, no statistical difference in survival was noted when comparing BCLC stages A, B, and C. Similarly, DFS decreased with a higher stage, but statistical significance was not achieved. However, when utilizing the Child-Pugh Grade, patients with Grade A had significantly better survival and DFS compared to Grade B and C patients. Several authors have identified Child-Pugh classification to be a significant predictor of survival on both univariate and multivariate analysis 9,14,22. Our long-term results are in accordance with our initial results that we have reported in the literature 6.

Individual criteria were analyzed to identify determinants of OS and DFS. The presence of moderate to severe ascites, bilirubin ≥2 (mg/dl), and AFP ≥ 400 were all found to be predictors of poor outcome. Finding predictive value of these individual factors is consistent with our findings of Child-Pugh Grade. Although current literature identifies tumor size and number to be predictive of survival, this was not found in this cohort 1,4,9,21. Similarly, no statistical difference was noted in DFS based on size or number of lesions. Size and number of tumors plays a critical role in determining the choice of therapeutic modalities. Chen et al. in a prospective randomized trial found no difference in OS or DFS between resection and ablation for solitary lesions <5 cm 23. Wakai et al. also identified that larger tumors have improved survival with surgical resection, while smaller tumors <4 cm have no difference in survival approached with ablation or resection 24. This data emphasizes the efficacy of RFA regardless of size and number of lesions. Although the largest tumor in this series measured 10 cm, our exclusion criteria evolved over the study period with a defined ablation limit of 7 cm. These criteria continue to expand as survival benefits are noted and the next generation of laparoscopic ablation equipment is made available.

Conclusion

Laparoscopic RFA is a promising safe and effective treatment modality for patients with primary and metastatic liver malignancies. RFA suggests a survival benefit for patients that are not candidates or await liver transplantation, or are deemed unresectable. Previous to local therapies this select subgroup of patients suffered poor outcomes. The results of this study comparing OS and DFS are encouraging.

References

- 1.Yamashiki N, Yoshida H, Tateishi R, Shiina S, Teratani T, Yoshida H, et al. Recurrent hepatocellular carcinoma has an increased risk of subsequent recurrence after curative treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22(12):2155–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(2):74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shiratori Y, Yoshida H, Omata M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: advances in diagnosis, treatment and prevention. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2001;1(2):277–90. doi: 10.1586/14737140.1.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lam VW, Ng KK, Chok KS, Cheung TT, Yuen J, Tung H, et al. Incomplete ablation after radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: analysis of risk factors and prognostic factors Ann Surg Oncol 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi S, Kudo M, Chung H, Inoue T, Ishikawa E, Kitai S, et al. Initial treatment response is essential to improve survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent curative radiofrequency ablation therapy. Oncology. 2007;72(Suppl. 1):98–103. doi: 10.1159/000111714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berber E, Herceg NL, Casto KJ, Siperstein AE. Laparoscopic radiofrequency ablation of hepatic tumors: prospective clinical evaluation of ablation size comparing two treatment algorithms. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(3):390–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-003-8911-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuehl H, Stattaus J, Hertel S, Hunold P, Kaiser G, Bockisch A, et al. Mid-term outcome of positron emission tomography/computed tomography-assisted radiofrequency ablation in primary and secondary liver tumours-a single-centre experience Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheele J, Stang R, Altendorf-Hofmann A, Paul M. Resection of colorectal liver metastases. World J Surg. 1995;19(1):59–71. doi: 10.1007/BF00316981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan K, Chen MH, Yang W, Wang YB, Gao W, Hao CY, et al. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular carcinoma: long-term outcome and prognostic factors Eur J Radiol 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleicher RJ, Allegra DP, Nora DT, Wood TF, Foshag LJ, Bilchik AJ. Radiofrequency ablation in 447 complex unresectable liver tumors: lessons learned. Ann Surg Oncol. 2003;10(1):52–8. doi: 10.1245/aso.2003.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curley SA, Izzo F, Ellis LM, Nicolas Vauthey J, Vallone P. Radiofrequency ablation of hepatocellular cancer in 110 patients with cirrhosis. Ann Surg. 2000;232(3):381–91. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200009000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teratani T, Yoshida H, Shiina S, Obi S, Sato S, Tateishi R, et al. Radiofrequency ablation for hepatocellular carcinoma in so-called high-risk locations. Hepatology. 2006;43(5):1101–8. doi: 10.1002/hep.21164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagasue N, Kohno H, Tachibana M, Yamanoi A, Ohmori H, El-Assal ON. Prognostic factors after hepatic resection for hepatocellular carcinoma associated with Child-Turcotte class B and C cirrhosis. Ann Surg. 1999;229(1):84–90. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199901000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Serag HB, Mason AC. Rising incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(10):745–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199903113401001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majno P, Castaing D, Adam R, Savier E, Ghemard O, Bismuth H.Liver resection as a bridge to transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis: a reasonable strategy? Ann Surg 2003;238(4):508–18; discussion 518–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yamamoto J, Iwatsuki S, Kosuge T, Dvorchik I, Shimada K, Marsh JW, et al. Should hepatomas be treated with hepatic resection or transplantation? Cancer. 1999;86(7):1151–8. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19991001)86:7<1151::aid-cncr8>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bismuth H, Majno PE, Adam R. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19(3):311–22. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Befeler AS, Di Bisceglie AM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(6):1609–19. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.33411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Predictive factors for long term prognosis after partial hepatectomy for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan . The Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan Cancer 1994;74(10):2772–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Neil BH, Venook AP. Hepatocellular carcinoma: the role of the North American GI steering committee hepatobiliary task force and the advent of effective drug therapy. Oncologist. 2007;12(12):1425–32. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.12-12-1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Guglielmi A, Ruzzenente A, Pachera S, Valdegamberi A, Sandri M, D'Onofrio M, et al. Comparison of seven staging systems in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort of patients who underwent radiofrequency ablation with complete response Am J Gastroenterol 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Colombo M, de Franchis R, Del Ninno E, Sangiovanni A, De Fazio C, Tommasini M, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Italian patients with cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(10):675–80. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199109053251002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen MS, Li JQ, Zheng Y, Guo RP, Liang HH, Zhang YQ, et al. A prospective randomized trial comparing percutaneous local ablative therapy and partial hepatectomy for small hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg. 2006;243(3):321–8. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000201480.65519.b8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wakai T, Shirai Y, Suda T, Yokoyama N, Sakata J, Cruz PV, et al. Long-term outcomes of hepatectomy vs percutaneous ablation for treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma < or =4 cm. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(4):546–52. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i4.546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Siperstein AE, Berber E, Ballem N, Parikh RT. Survival after radiofrequency ablation of colorectal liver metastases: 10-year experience. Annals of Surgery. 2007;246(4):559–65. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318155a7b6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–42. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lopez PM, Villanueva A, Llovet JM. Systematic review: evidence-based management of hepatocellular carcinoma-an updated analysis of randomized controlled trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1535–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02932.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]