Abstract

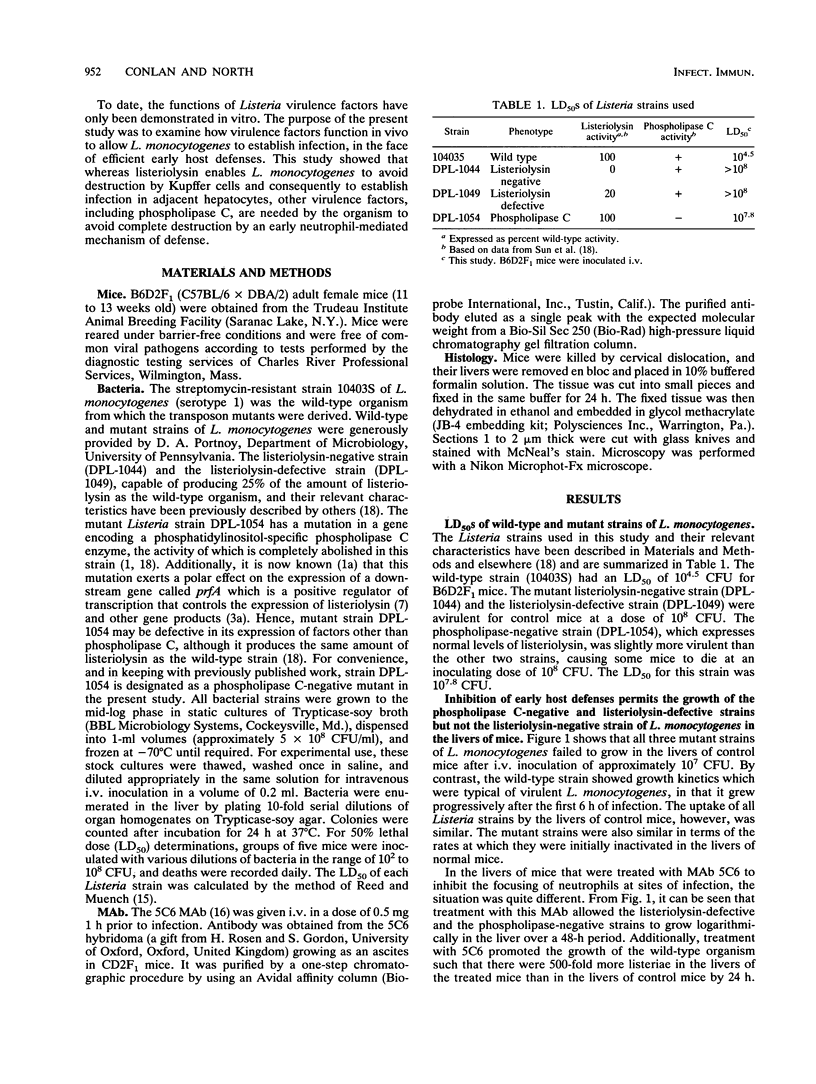

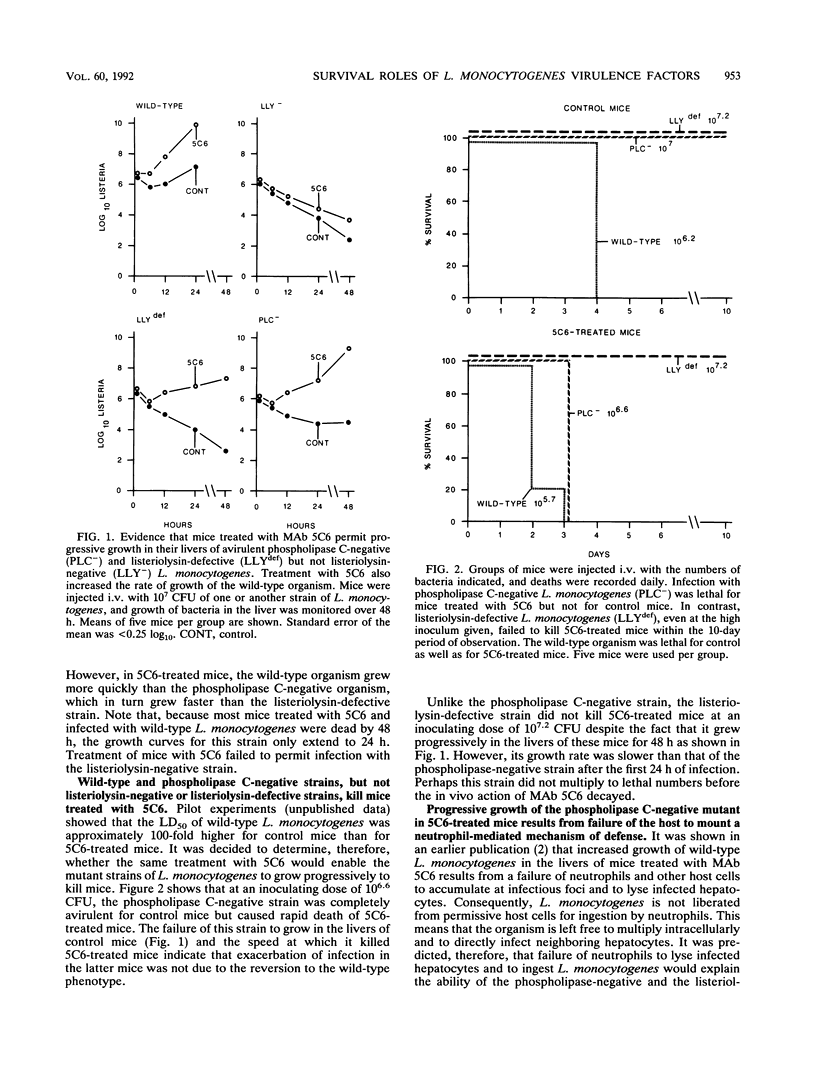

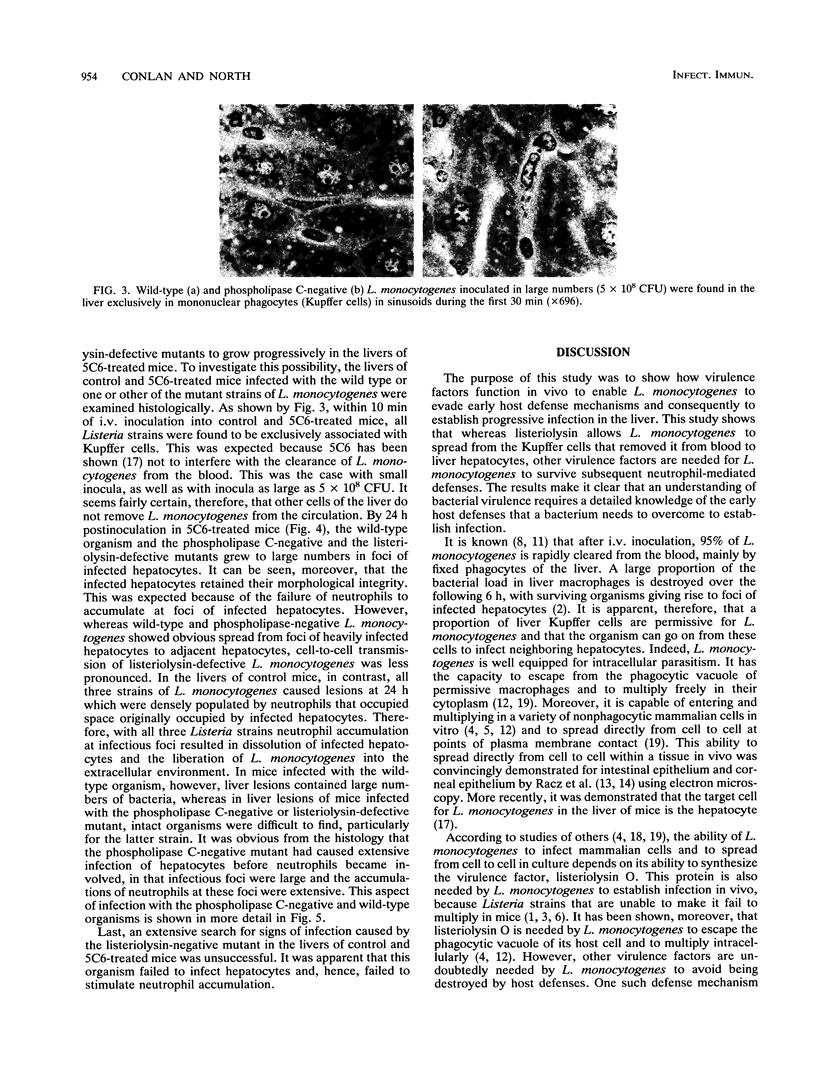

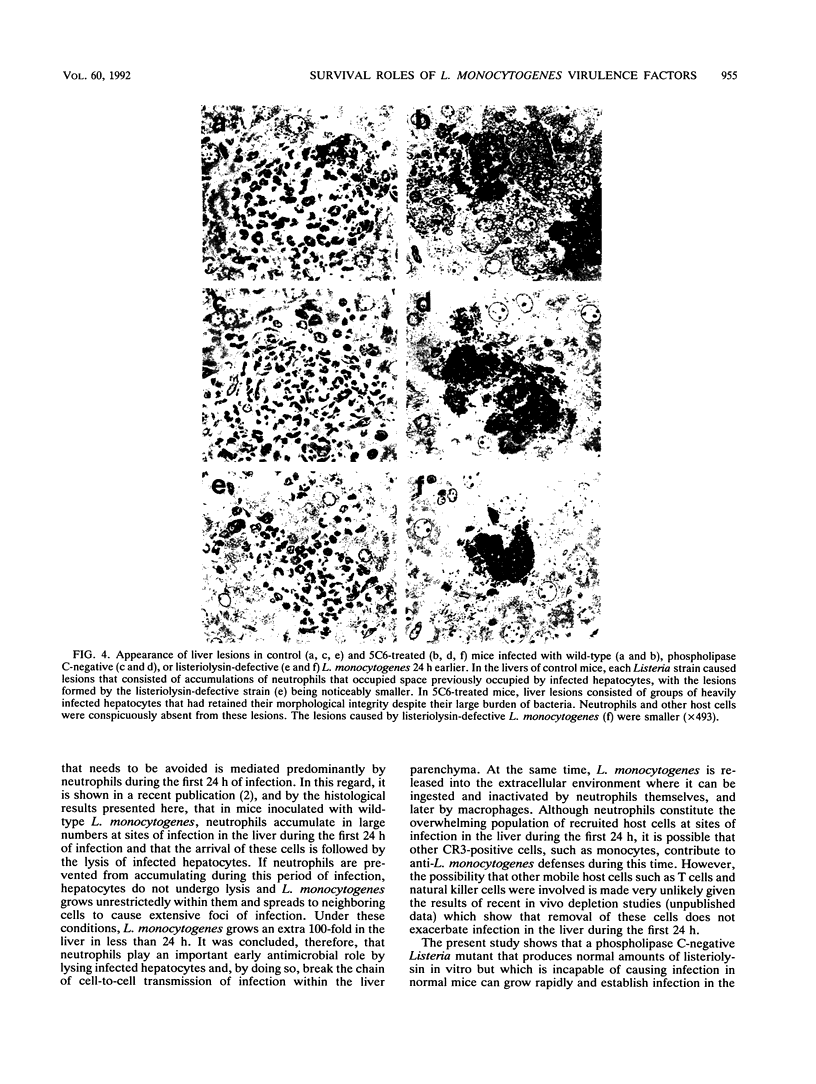

Avirulent mutant strains of Listeria monocytogenes which fail to produce phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C, or which produce reduced amounts of hemolytic listeriolysin O, are incapable of causing progressive infection in normal mice. However, both strains can grow progressively in mice that have been rendered incapable of focusing neutrophils at sites of infection as a result of being treated with monoclonal antibody 5C6, specific for the type 3 complement receptor of myelomonocytic cells. In 5C6-treated mice, phospholipase C-negative and listeriolysin-defective mutant strains of L. monocytogenes, like the wild-type strain, give rise in the liver to large numbers of discrete foci of infected hepatocytes that retain their morphological integrity during the first 24 h, despite their large bacterial burden. In normal mice, in contrast, sites of infection in the liver are indicated by discrete focal accumulations of neutrophils that occupy the space originally occupied by infected hepatocytes. It is apparent that in normal mice neutrophils function to lyse infected hepatocytes and thereby to release L. monocytogenes for ingestion and killing by neutrophils themselves and by macrophages. However, whereas a proportion of wild-type organisms survive this early mechanism of defense to give rise to progressive infection, the phospholipase C-negative organisms are totally eliminated. On the basis of these and other results, it is suggested that virulence factors other than listeriolysin are needed by L. monocytogenes to counteract the early neutrophil-mediated mechanism of defense. Listeriolysin, itself, is an intrinsic virulence factor that allows L. monocytogenes to survive and multiply in a proportion of the fixed phagocytes of the liver (permissive phagocytes) and which enables the organism to go on to infect and replicate in adjacent hepatocytes. It was found that a mutant strain of L. monocytogenes incapable of producing any listeriolysin was incapable of establishing progressive infection, even in 5C6-treated mice.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Camilli A., Goldfine H., Portnoy D. A. Listeria monocytogenes mutants lacking phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C are avirulent. J Exp Med. 1991 Mar 1;173(3):751–754. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.3.751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conlan J. W., North R. J. Neutrophil-mediated dissolution of infected host cells as a defense strategy against a facultative intracellular bacterium. J Exp Med. 1991 Sep 1;174(3):741–744. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cossart P., Vicente M. F., Mengaud J., Baquero F., Perez-Diaz J. C., Berche P. Listeriolysin O is essential for virulence of Listeria monocytogenes: direct evidence obtained by gene complementation. Infect Immun. 1989 Nov;57(11):3629–3636. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.11.3629-3636.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaillard J. L., Berche P., Mounier J., Richard S., Sansonetti P. In vitro model of penetration and intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the human enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1987 Nov;55(11):2822–2829. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2822-2829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havell E. A. Synthesis and secretion of interferon by murine fibroblasts in response to intracellular Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1986 Dec;54(3):787–792. doi: 10.1128/iai.54.3.787-792.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathariou S., Metz P., Hof H., Goebel W. Tn916-induced mutations in the hemolysin determinant affecting virulence of Listeria monocytogenes. J Bacteriol. 1987 Mar;169(3):1291–1297. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.3.1291-1297.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leimeister-Wächter M., Haffner C., Domann E., Goebel W., Chakraborty T. Identification of a gene that positively regulates expression of listeriolysin, the major virulence factor of listeria monocytogenes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Nov;87(21):8336–8340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.21.8336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MACKANESS G. B. Cellular resistance to infection. J Exp Med. 1962 Sep 1;116:381–406. doi: 10.1084/jem.116.3.381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackaness G. B. The influence of immunologically committed lymphoid cells on macrophage activity in vivo. J Exp Med. 1969 May 1;129(5):973–992. doi: 10.1084/jem.129.5.973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North R. J. T cell dependence of macrophage activation and mobilization during infection with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 1974 Jul;10(1):66–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.10.1.66-71.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North R. J. The relative importance of blood monocytes and fixed macrophages to the expression of cell-mediated immunity to infection. J Exp Med. 1970 Sep 1;132(3):521–534. doi: 10.1084/jem.132.3.521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy D. A., Jacks P. S., Hinrichs D. J. Role of hemolysin for the intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes. J Exp Med. 1988 Apr 1;167(4):1459–1471. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.4.1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H., Gordon S. Monoclonal antibody to the murine type 3 complement receptor inhibits adhesion of myelomonocytic cells in vitro and inflammatory cell recruitment in vivo. J Exp Med. 1987 Dec 1;166(6):1685–1701. doi: 10.1084/jem.166.6.1685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen H., Gordon S., North R. J. Exacerbation of murine listeriosis by a monoclonal antibody specific for the type 3 complement receptor of myelomonocytic cells. Absence of monocytes at infective foci allows Listeria to multiply in nonphagocytic cells. J Exp Med. 1989 Jul 1;170(1):27–37. doi: 10.1084/jem.170.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rácz P., Tenner K., Mérö E. Experimental Listeria enteritis. I. An electron microscopic study of the epithelial phase in experimental listeria infection. Lab Invest. 1972 Jun;26(6):694–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rácz P., Tenner K., Szivessy K. Electron microscopic studies in experimental keratoconjunctivitis listeriosa. I. Penetration of Listeria monocytogenes into corneal epithelial cells. Acta Microbiol Acad Sci Hung. 1970;17(3):221–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun A. N., Camilli A., Portnoy D. A. Isolation of Listeria monocytogenes small-plaque mutants defective for intracellular growth and cell-to-cell spread. Infect Immun. 1990 Nov;58(11):3770–3778. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.11.3770-3778.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilney L. G., Portnoy D. A. Actin filaments and the growth, movement, and spread of the intracellular bacterial parasite, Listeria monocytogenes. J Cell Biol. 1989 Oct;109(4 Pt 1):1597–1608. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.4.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]