Abstract

Murine models of starvation-induced muscle atrophy demonstrate that reduced protein kinase B (AKT) function upregulates the atrophy-related gene atrogin-1/MAFbx (atrogin). The mechanism involves release of inhibition of Forkhead transcription factors, namely Foxo1 and Foxo3. Elevated atrogin mRNA also corresponds with elevated TNF in inflammatory catabolic states, including cancer and chronic heart failure. Exogenous tumor necrosis factor (TNF) increases atrogin mRNA in vivo and in vitro. We used TNF-treated C2C12 myotubes to test the hypothesis that AKT-Foxo1/3 signaling mediates TNF regulation of atrogin mRNA. Here we confirm that exposure to TNF increases atrogin mRNA (+125%). We also confirm that canonical AKT-mediated regulation of atrogin is active in C2C12 myotubes. Inhibition of phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)/AKT signaling with wortmannin reduces AKT phosphorylation (−87%) and increases atrogin mRNA (+340%). Activation with insulin-like growth factor (IGF) increases AKT phosphorylation (+126%) and reduces atrogin mRNA (−15%). Although AKT regulation is intact, our data suggest it does not mediate TNF effects on atrogin. TNF increases AKT phosphorylation (+50%) and stimulation of AKT with IGF does not prevent TNF induction of atrogin mRNA. Nor does TNF appear to signal through Foxo1/3 proteins. TNF has no effect on Foxo1/3 mRNA or Foxo1/3 nuclear localization. Instead, TNF increases nuclear Foxo4 protein (+55%). Small interfering RNA oligos targeted to two distinct regions of Foxo4 mRNA reduce the TNF-induced increase in atrogin mRNA (−34% and −32%). We conclude that TNF increases atrogin mRNA independent of AKT via Foxo4. These results suggest a mechanism by which inflammatory catabolic states may persist in the presence of adequate growth factors and nutrition.

Keywords: skeletal muscle, cachexia, atrophy, ubiquitin, cytokines

the bulk of muscle protein lost during muscle atrophy is degraded by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (19, 25, 35). The specificity of this system is regulated by ubiquitin ligases (E3 proteins). Atrogin-1/MAFbx (atrogin) is a muscle-specific E3 protein that is upregulated in catabolic states that include humans under voluntary bed rest (37), or with spinal cord injury (46), amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (27), or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (9); and in animal models of cancer (4), sepsis (12, 49), aging (3), chronic heart failure (29), chronic kidney disease (10), diabetes (7, 24), starvation (20, 24), denervation (39), and unloading (17). The role of atrogin as a mediator of muscle atrophy is supported by studies that show overexpression in cell culture myotubes results in a fivefold reduction in myotube diameter (2). In addition, the absence of atrogin results in a 56% reduction in muscle atrophy after denervation in knockout mice (2).

Atrogin gene expression is under the transcriptional control of Forkhead box O transcription factors (Foxo). Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4 are related Foxo proteins thought to regulate atrogin under a variety of conditions. Foxo1 and Foxo3 mRNA are upregulated with starvation (21, 24), diabetes (26), cachexia, and aging (13, 22, 24). Foxo4 is less well studied but is modulated in heart failure models of atrophy (42).

Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4 activity is regulated by phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K)-protein kinase B (AKT) signaling (41, 42, 45). Basal AKT function maintains Foxo in a phosphorylated state that favors cytoplasmic retention and repression of transcriptional activity. Overexpression of IGF can further suppress Foxo activity through stimulation of AKT (15, 16, 42). Wortmannin, a PI3K inhibitor, depresses AKT activity and Foxo phosphorylation (28, 40, 44). With starvation or dexamethasone treatment, AKT activity and Foxo1 and Foxo3 phosphorylation are decreased. Foxo1/3 subsequently translocate to the nucleus to drive atrogin expression (41, 45). The activity of Foxo4 under these conditions has not been established.

Atrogin mRNA has been shown to increase with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) exposure in muscles of rats (12) and mice (31) and in primary and C2C12 myotubes (30, 31). The goal of our current study was to define components of the signaling pathway that mediate TNF-induced atrogin expression. We postulated that a similar AKT-Foxo1/3-dependent mechanism mediates TNF effects on atrogin expression in differentiated muscle cells. This model (Fig. 1A) was evaluated by using mature C2C12 myotubes to test two hypotheses: 1) TNF induces atrogin expression through inhibition of AKT. To assess the role of AKT, we measured changes in atrogin expression and AKT phosphorylation after a time course of TNF exposure. We also measured the inhibitory potential of AKT activation on TNF-induced atrogin expression. 2) TNF induces atrogin expression through activation of Foxo1/3 transcription factors. To assess the roles of Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4, we measured changes in Foxo mRNA, protein, and nuclear translocation after TNF exposure.

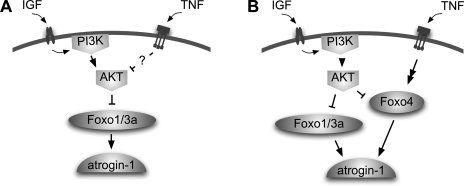

Fig. 1.

Model of regulation of atrogin by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF). A: inhibition of protein kinase B (AKT) leads to activation of Forkhead box O transcription factor (Foxo) and an increase in atrogin mRNA. We hypothesized that TNF might increase atrogin expression by inhibiting AKT. B: we propose TNF increases atrogin expression by overriding the inhibitory effects of AKT and activating Foxo4 by an unknown mechanism. atrogin, atrogin-1/MAFbx muscle atrophy F-box; IGF, insulin-like growth factor; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase.

Here we confirm that elements of the canonical AKT-Foxo1/3-atrogin pathway are active in C2C12 myotubes. Inhibition of AKT or overexpression of Foxo1 causes an increase in atrogin mRNA. Paradoxically, we demonstrate that TNF increases atrogin mRNA despite simultaneous activation of AKT. In addition, TNF has no apparent effect on endogenous Foxo1 or Foxo3 activity. Instead, it induces nuclear translocation of Foxo4 protein. Finally, myotubes treated with Foxo4 small interfering RNA (siRNA) have a diminished atrogin response to TNF. Thus we propose a revised model where TNF bypasses AKT inhibitory signaling to activate Foxo4-mediated atrogin expression (Fig. 1B).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture.

C2C12 myoblasts (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) were seeded at a density of 8,000–10,000 cells/cm2 and allowed to proliferate in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 25 mg/ml gentamicin (GIBCO-Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in 5% CO2 at 37°C. After 2 days the myoblasts were shifted to differentiation medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium-2% horse serum-25 mg/ml gentamicin). After 4–6 days of differentiation, myotubes were treated with the following reagents: 6 ng/ml recombinant mouse TNF (Pierce, Rockford, IL), 10 ng/ml recombinant human IGF-1 (Invitrogen), 100 nM wortmannin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), or 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich).

Stable Foxo1/TSS-ER C2C12 cell lines were generated according to Bastie et al. (1). Briefly, the AKT phosphorylation sites in Foxo1 (Thr24, Ser256, and Ser319) were mutated to alanine. The COOH-terminus was fused to a modified ligand-binding domain of the estrogen receptor. This ligand-binding domain is transcriptionally inactive and has been mutated such that it specifically responds to tamoxifen but not to endogenous estrogens (33). The construct was cloned into the pBABE retroviral vector containing the puromycin selection marker and stably transfected cells were isolated.

Relative quantification real time PCR (rqPCR).

Reverse transcription was performed with Murine-Maloney leukemia virus reverse transcriptase and random hexamers (Promega, Madison, WI) plus 2 μg total RNA isolated with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). The mouse cDNA sequences for atrogin-1/MAFbx (NM-026346), Foxo1 (NM-019739.2), Foxo3 (NM-019740.2), Foxo4 (Mllt7, NM-018789.1), and β-actin (NM-007393.1) were obtained from GenBank. PCR primers were designed from the cDNA sequences using Primer Express 1.5 software (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Primer sequences are as follows: atrogin forward 5′-ATGCACACTGGTGCAGAGAG-3′; reverse; 5′-TGTAAGCACACAGGCAGGTC-3′ Foxo1 forward 5′-GTGAACACCAATGCCTCACAC-3′, reverse 5′-CACAGTCCAAGCGCTCAATA-3′; Foxo3 forward 5′-AGCCGTGTACTGTGGAGCTT-3′, reverse 5′- TCTTGGCGGTATATGGGAAG-3′; Foxo4 forward 5′-CAAGAAGAAGCCGTCTGTCC-3′, reverse 5′-CTGACGGTGCTAGCATTTGA-3′; b-actin forward 5′-AGGCCCAGAGCAAGAGAGGTA-3′, reverse 5′-CCATGTCGTCCCAGTTGGTAA-3′. Synthesized primers were purchased from Invitrogen. PCR was performed using Applied Biosystems 7500 Real Time PCR system. Targets were amplified from 50 ng of cDNA using SYBR Green Master Mix reagent (stage 1, 1 cycle, 50°C, 2 min; stage 2, 1 cycle, 95°C, 10 min; stage 3, 40 cycles, 95°C, 15 s, 60°C, 1 min; Applied Biosystems). Reactions were performed in duplicate or triplicate for each cDNA sample. The abundance of target mRNA relative to β-actin mRNA was determined using the comparative cycle threshold method (14, 34).

Western blot analysis.

Cells were washed once with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) then resuspended and briefly sonicated in 2× sample loading buffer (120 mM Tris, pH 7.5, 200 mM DTT, 20% glycerol, 4% SDS, and 0.002% bromphenol blue). Proteins were fractionated on 4–15% SDS-polyacrylaminde gels (Criterion precast gels, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Fractionated proteins were transferred to reduced-fluorescence polyvinyldifluoride membrane (Immobilon-FL, Millipore, Bedford, MA). Membranes with transferred proteins were blocked for 1 h at room temperature in Odyssey Blocking Buffer (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). Primary antibodies were incubated overnight at room temperature in Odyssey Blocking Buffer mixed 1:1 with PBS plus 0.2% Tween. Secondary antibodies were incubated for 30 min in Odyssey-PBS-0.2% Tween plus 0.01% SDS. Total AKT antibody and atrogin antibody were purchased from ECM Biosciences (Versailles, KY). Foxo1, Foxo4, and phospho-specific AKT (S473) antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Danvers, MA). Foxo3 antibody was purchased from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY). Myosin antibody was from Sigma. Fluorescent secondary antibodies were used for detection (goat anti-mouse Alexa-680, Molecular Probes-Invitrogen; goat anti-rabbit IRD800, Rockland Immunochemicals, Gilbertsville, PA). Fluorescence was imaged and results were quantified using the Odyssey Infrared Imaging System (LI-COR).

Immunocytochemistry.

Foxo1/TSS overexpressing C2C12 skeletal myotubes were grown on glass coverslips coated in ECL cell attachment matrix (Upstate, Charlottesville, VA) for 4 days in DMEM supplemented with 2% horse serum (Invitrogen). Foxo1/TSS myotubes were treated with either vehicle (0.1% vol/vol EtOH final concentration) or 1 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-HT) for 2 h. Myotubes were then washed in PBS, fixed in 4% formaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized (0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS), blocked (1 M Tris·HCl, pH 7.6, supplemented with 3% BSA, 0.2% gelatin, 0.05% Tween-20), and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibody directed against the Foxo1 protein (Cell Signaling). Myotubes were then washed in PBS, incubated with a TRITC-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson Immuno Research, West Grove, PA), and mounted in Vectashield mounting medium supplemented with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Myotubes were assessed for Foxo1 localization using a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging, Thornwood, NY).

siRNA.

Two Silencer predesigned siRNAs for Foxo4 (siRNA IDs: no. 184930 and no. 184932) and Negative Control no. 2 siRNA were purchased from Ambion (Austin, TX). siRNA (100 μM) was transfected into day 4 myotubes using oligofectamine diluted 1:5 with DMEM according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Changes in atrogin mRNA and protein were assayed 72 h posttransfection.

Statistical analysis.

Data were normally distributed and are expressed as means ± SE. Student's t-test was used for the statistical comparison of two means; ANOVA was used for the comparison of multiple means. When ANOVA revealed significant differences, Tukey's post hoc test for multiple comparisons was performed. *P values <0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

TNF modulation of atrogin.

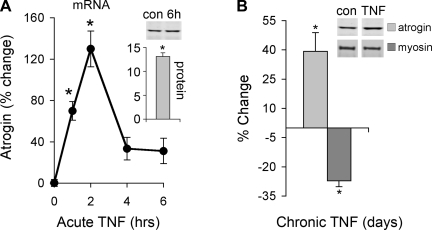

TNF regulation of atrogin mRNA and the effect on myosin levels was measured by real time PCR and Western blot analysis. Atrogin mRNA increases early and peaks at 2 h. A decrease in myosin protein is detected after 72 h of daily TNF treatments (Fig. 2A). These data confirm earlier reports that show TNF induces atrogin expression (30) and myosin loss (8, 32). In addition, our data are the first to show that TNF causes an elevation in atrogin protein that begins to accumulate by 6 h (Fig. 2A) and remains elevated with chronic, repeated exposure to TNF (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

TNF regulation of atrogin. A: C2C12 myotubes were treated with 6 ng/ml TNF for 1, 2, 4, and 6 h. Atrogin mRNA was measured by real-time PCR, and protein was measured by Western blot analysis (insets). mRNA increased by 1 h and peaked at 2 h, protein peaked by 6 h (*P < 0.05 vs. untreated control, n = 3). B: C2C12 myotubes were treated chronically with 6 ng/ml TNF added at 24, 48, and 72 h. Atrogin protein remained elevated and myosin levels dropped (*P < 0.05 vs. untreated control, n = 3).

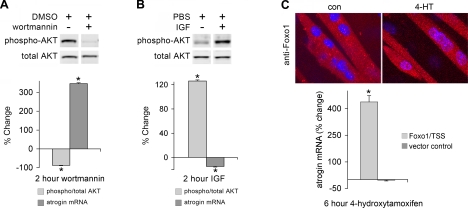

AKT/Foxo pathway regulation of atrogin.

The contribution of AKT/Foxo signaling to control of atrogin expression was confirmed by exposing myotubes to wortmannin, an inhibitor of PI3K that reduces AKT activity (28, 40, 44), IGF, a stimulator of PI3K/AKT signaling that increases AKT activity (15, 16, 42), or overexpression of a Foxo1 mutant (Foxo1/TSS) resistant to inhibition by AKT and activated by 4-HT (1, 33). Inhibition or activation of AKT was evaluated by Western blot analysis with phospho-specific and total AKT antibodies. Treatment of myotubes with wortmannin for 2 h produced the expected decrease in AKT phosphorylation and increase in atrogin mRNA (Fig. 3A). IGF effects were reversed; as phospho-AKT increased, atrogin mRNA decreased (Fig. 3B). Foxo1/TSS nuclear translocation, as assessed by immunofluorescent staining, caused a corresponding rise in atrogin mRNA (Fig. 3C). These data suggest that basal atrogin mRNA levels are held in check by AKT. This suppression is augmented by IGF, whereas AKT inhibition or Foxo1/TSS nuclear translocation allows atrogin mRNA to accumulate.

Fig. 3.

Canonical AKT pathway regulation of atrogin. C2C12 myotubes were treated with wortmannin 100 nm (A), IGF 10 ng/ml (B) for 2 h, or subjected to overexpression of a Foxo1/TSS mutant resistant to inhibition by AKT (C). This mutant is fused to the ligand-binding domain of the estrogen receptor and was induced to translocate to the nucleus with 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4-HT, 1 μM). AKT was measured by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for total and phospho-AKT. AKT phosphorylation decreased with wortmannin and increased with IGF (*P < 0.001, n = 3). Atrogin mRNA was measured by real time PCR. Atrogin increased with wortmannin and 4-HT induced Foxo1/TSS nuclear translocation (*P < 0.001, n = 3) and decreased with IGF (*P < 0.05, n = 3). 4-HT had no effect on atrogin mRNA in vector control cells.

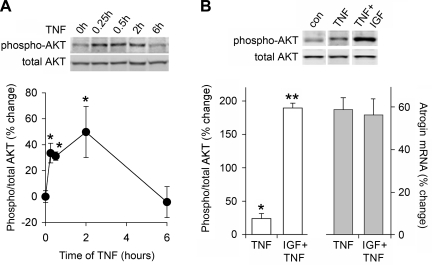

TNF modulation of AKT.

The control AKT signaling exerts on atrogin is demonstrated by experiments described in Fig. 3, thus is seemed likely that TNF would modulate this pathway to promote atrogin expression. Paradoxically, TNF acted opposite of our expectations and induced an increase AKT phosphorylation (Fig. 4A). Phosphorylation of AKT begins early and peaks at 2 h, following a time course similar to atrogin induction (Fig. 2A). Thus TNF promotes atrogin expression not because of suppression of AKT signaling, but despite an increase in AKT signaling. Further evidence to support this conclusion is shown in Fig. 4B. IGF, through activation of AKT, is known to suppress glucocorticoid-induced atrogin expression (45). Therefore, we treated myotubes with IGF 30 min before the addition of TNF. Two hours post-TNF we measured AKT phosphorylation and atrogin expression. IGF pretreatment increased AKT phosphorylation eightfold over TNF alone, but TNF-induced atrogin expression was unaffected. Thus the mechanism of TNF activation of atrogin appears to be independent of the canonical AKT pathway.

Fig. 4.

TNF-induced atrogin expression and AKT activation. A: C2C12 myotubes were treated with 6 ng/ml TNF for 15 and 30 min and 2 and 6 h. AKT was measured by immunoblotting with antibodies specific for total and phospho-AKT. AKT phosphorylation is evident by 15 min and persists for up to 2 h (*P < 0.05, n = 3). B: myotubes were pretreated for 30 min with 10 ng/ml IGF followed by 2 h TNF 6 ng/ml. As measured by Western blot analysis and real time PCR, pretreatment with IGF elevates phospho-AKT levels eightfold relative to TNF alone (**P < 0.0001, n = 3) but does not prevent the TNF-induced rise atrogin mRNA.

Foxo isoforms in C2C12 myotubes.

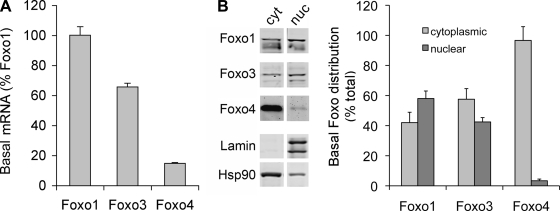

Foxo proteins are also a component of our model (Fig. 1). But before evaluating TNF effects on Foxo proteins, we wanted to know more about basal expression of the different isoforms in C2C12 myotubes. Figure 5A shows the relative abundance of Foxo isoform mRNAs. Foxo1 is most abundant and is expressed as 100%. Foxo3 and Foxo4 are 65% and 15% of Foxo1 levels, respectively. Since Foxo proteins are in part regulated by control of nuclear localization, we measured the nuclear and cytoplasmic distribution of Foxo isoforms (Fig. 5B). Both Foxo1 and Foxo3 have a greater presence in the nuclear fraction with nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratios of 1.4 and 0.74, respectively. In contrast, Foxo4 is predominantly cytoplasmic with a nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio of 0.05.

Fig. 5.

Basal Foxo isoform levels and localization. A: total RNA from untreated C2C12 myotubes was extracted and assayed by real time PCR for Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4 mRNA. B: nuclear (nuc) and cytoplasmic (cyt) extracts were prepared from untreated C2C12 myotubes, and Foxo localization was measured by Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4. Basal Foxo1 and Foxo3 protein are approximately evenly distributed between cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments. Foxo4 is predominantly cytoplasmic (P < 0.01 nuclear vs. cytoplasmic Foxo4, n = 3).

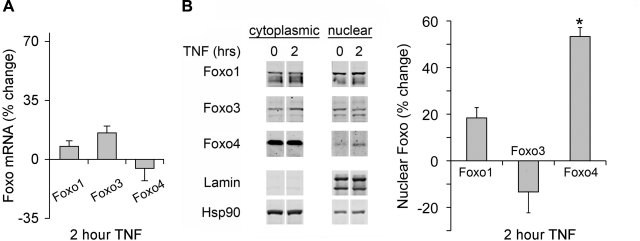

Foxo isoform responses to TNF.

To assess whether TNF modulates Foxo isoform activity, we treated myotubes with TNF and measured changes in mRNA. We also assessed changes in nuclear localization by cell fractionation and Western blot analysis. TNF has no affect on Foxo isoform mRNA (Fig. 6A) nor does it affect Foxo1 or Foxo3 nuclear localization. TNF does increase Foxo4 nuclear localization (Fig. 6B). These data suggest that TNF modulates Foxo, and the response is isoform specific with Foxo4 being most sensitive.

Fig. 6.

Foxo isoform response to TNF. A: C2C12 myotubes were treated with 6 ng/ml TNF for 2 h; total RNA was isolated and assayed by real time PCR for changes in Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4 mRNA. Foxo isoform mRNAs did not change with TNF. B: nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts were prepared from TNF-treated C2C12 myotubes, and Foxo isoform localization was measured by Western blot analysis with antibodies specific for Foxo1, Foxo3, and Foxo4. Only Foxo4 translocates to the nucleus in response to TNF (*P < 0.05).

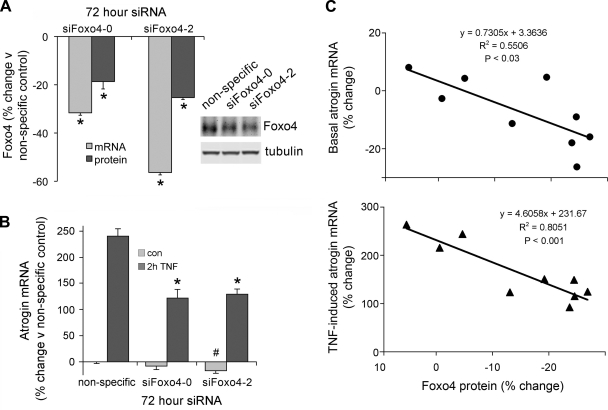

Foxo4 knockdown and reduction of the atrogin response to TNF.

To further evaluate Foxo4 as a TNF-sensitive factor, we used siRNA to selectively depress Foxo4 mRNA and protein. Figure 7A shows that siRNAs targeted to two different regions of Foxo4 reduced Foxo4 mRNA by 32% and 56%, and Foxo4 protein by 19% and 25%, relative to a nonspecific siRNA control. Foxo4 siRNA had a modest effect on basal atrogin levels (reduced 8%, P < 0.2 and 17%, P < 0.05) and diminished the response to TNF by an average of 34% relative to the nonspecific control (Fig. 7B). Figure 7C shows that basal and TNF-induced atrogin mRNA levels were proportional to Foxo4 protein content; as siRNA depressed Foxo4, atrogin mRNA fell. Thus Foxo4 appears to modulate atrogin mRNA.

Fig. 7.

Downregulation of Foxo4 diminishes the induction of atrogin mRNA in response to TNF. Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) 100 μM specific to 2 regions of the Foxo4 mRNA and a nonspecific siRNA control (siFoxo4-0, siFoxo4-2, and NS) were transfected into myotubes 96 h postdifferentiation. Seventy-two hours posttransfection, myotubes were treated for 2 h with 6 ng/ml TNF. A: Foxo4 mRNA, as assayed by real time PCR, and protein, as assayed by Western blot analysis, were reduced by both siFoxo4-0 and siFoxo4-2 relative to the nonspecific siRNA control (*P < 0.05, n = 3). B: TNF-induced increase in atrogin mRNA, as measured by real time PCR, was reduced by siFoxo4-0 and siFoxo4-2 relative to the nonspecific siRNA control (34% average reduction, *P < 0.05, n = 3). C: linear regression showing the relationship between changes in Foxo4 protein and changes in atrogin mRNA.

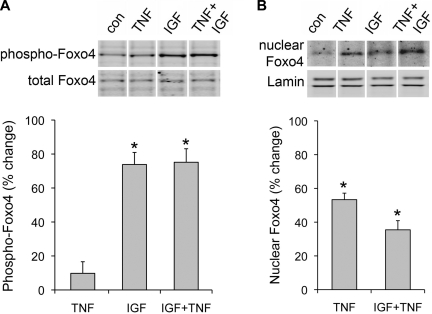

IGF regulation of Foxo4.

Since Foxo4 appears to mediate TNF-induced atrogin mRNA, and IGF fails to inhibit this response, we hypothesized Foxo4 might resist IGF action. We measured phosphorylation of the AKT inhibitory sites on Foxo4 after IGF or IGF+TNF treatment. Figure 8A shows that phospho-Foxo4 levels increase with IGF and this is not affected by posttreatment with TNF. We also measured Foxo4 nuclear translocation (Fig. 8B). In contrast to phosphorylation, 2 h of IGF exposure did not drive Foxo4 from the nucleus nor did pretreatment prevent TNF-induced nuclear translocation. These data suggest an alternate activation mechanism overcomes inhibitory phosphorylation to promote nuclear translocation of Foxo4.

Fig. 8.

IGF effects on Foxo4. Myotubes were pretreated for 30 min with 10 ng/ml IGF followed by 2 h 6 ng/ml TNF. A: as measured by Western blot, pretreatment with IGF elevates phospho-Foxo4 (*P < 0.01, n = 3), and TNF does not reverse IGF-induced phosphorylation. B: nuclear extracts were prepared from myotubes treated as in A. TNF induced Foxo4 nuclear translocation (*P < 0.05, n = 3) that was not prevented by pretreatment with IGF.

DISCUSSION

The goal of our current study was to define components of the signaling pathway that mediate TNF-induced atrogin expression. We proposed that TNF would function similar to starvation where atrogin mRNA is elevated through AKT inhibition and Foxo1 and/or Foxo3 activation. Instead, our results suggest that induction of atrogin by TNF bypasses AKT-Foxo1/3 signaling and triggers an alternate pathway. Whereas starvation or glucocorticoids reduce AKT phosphorylation, TNF increases it. IGF inhibits starvation- and glucocorticoid-induced atrogin expression but has no influence on TNF regulation. These observations contribute to a gathering body of literature that suggest inflammation-related atrophy is not controlled by AKT-Foxo1/3 signaling. For example, COPD patients with limb muscle atrophy have elevated atrogin and MuRF1 mRNA; however, phosphorylated AKT is also increased (9). In addition, patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) exhibit skeletal muscle atrophy and increased atrogin mRNA and protein. However, neither Foxo1 nor Foxo3 protein levels differ from healthy control individuals (27). Finally, Dehoux et al. (6) show IGF does not reverse C2C12 myotube atrophy caused by an inflammatory cocktail of TNF and IFN-γ. In contrast to our data, however, they show IGF reverses the cytokine-induced increase in atrogin mRNA. The apparent discrepancy may be due to differences in experimental design and cytokine stimuli. Our experiments measured early responses 2 h after treatment with TNF. We tested the effects of IGF pretreatment on these early responses and found atrogin expression was unaffected. Dehoux et al. (6) measured a longer-term response 24 h after treatment with both TNF and IFNγ. They tested the effects of IGF posttreatment on the longer-term response and found atrogin mRNA levels were blunted. Combined, these data suggest there may be two phases to cytokine regulation of atrogin: an early phase that is independent of AKT and a prolonged phase that is sensitive to AKT regulation. This second phase could involve IFNγ, an idea consistent with a report by Smith et al. (43) that shows IFNγ depresses AKT phosphorylation. Both studies measured the effects of IGF on atrogin mRNA. IGF-cytokine combination studies that also measure atrogin protein would further clarify these issues.

Our results suggest that neither Foxo1 nor Foxo3 respond to TNF. Instead, Foxo4 appears to be the TNF-responsive isoform. Under basal conditions Foxo4 protein is mostly restricted to the cytoplasm and TNF rapidly stimulates nuclear translocation. Knockdown of Foxo4 protein by siRNA represses TNF regulation of atrogin. These data prompted us to refine our model and propose that Foxo4 mediates TNF-induced atrogin expression. Our results are reinforced by data from mouse models of heart failure, a pathophysiological process accompanied by chronic inflammation. Twelve weeks after induction of heart failure, animals exhibit skeletal muscle atrophy with increased active Foxo4 protein and elevated atrogin mRNA (42). Further experiments with Foxo4-null mice or cells stably transfected with Foxo4 shRNA will be important to better define the role Foxo4 plays in atrophy associated with chronic inflammation.

There are several potential mechanisms by which TNF might activate Foxo4. Among these, response to changes in intracellular oxidant activity is a common regulatory theme. Skeletal muscle oxidant activity is elevated in chronic inflammatory states or with exposure to TNF (18, 36). These increases in cellular oxidant activity are thought to be pro-catabolic (38, 36) and can activate Foxo4 by at least four mechanisms. First, Foxo factors are subject to regulation by redox-sensitive reversible acetylation (23). Acetylation, which inhibits Foxo transcriptional activity, is catalyzed by histone acetyltransferase cAMP-response element-binding protein-binding protein (5). Oxidative stress releases this inhibition by deacetylation via NAD-dependent deacetylase hSir2 (SIRT1) (23, 48). Second, oxidative stress can stimulate rapid monoubiquitination of Foxo4, causing nuclear translocation and increased transcriptional activity in human embryonic kidney cells (47). Third, H2O2 or TNF treatment of fibroblasts increases activation of Foxo4 via jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK)-dependent phosphorylation of threonines 447 and 451 (11). JNK is also activated by H2O2 or TNF in cultured myotubes (30), suggesting JNK could mediate TNF/Foxo4 signaling in muscle. Finally, Li et al. (30) demonstrated that TNF-induced atrogin expression is dependent on p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK). Like JNK, p38 MAPK activity is increased by H2O2 or TNF in skeletal muscle myotubes, and suppression of this activity prevents the induction of atrogin (30).

The signaling mechanisms that regulate atrogin expression appear to differ depending on catabolic stimulus. AKT regulation of atrogin is modulated by low nutrients, dexamethasone, or pharmacological inhibition. All of these reduce AKT activity, relieving Foxo1, Foxo3 (41, 45), and presumably Foxo4 inhibition. TNF and/or potentially inflammation in general appear to act via a second pathway. Our current findings indicate TNF increases Foxo4 activity through an AKT-independent, growth factor-insensitive process. Thus the TNF/Foxo4 pathway is a mechanism by which inflammation might upregulate atrogin and promote muscle catabolism despite high levels of circulating nutrients or growth factors. The intermediate steps in this pathway and the mechanism by which TNF bypasses AKT regulation of Foxo4 are yet to be defined.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant HL-59878.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bastie CC, Nahle Z, McLoughlin T, Esser K, Zhang W, Unterman T, Abumrad NA. FoxO1 stimulates fatty acid uptake and oxidation in muscle cells through CD36-dependent and -independent mechanisms. J Biol Chem 280: 14222–14229, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bodine SC, Latres E, Baumhueter S, Lai VK, Nunez L, Clarke BA, Poueymirou WT, Panaro FJ, Na E, Dharmarajan K, Pan ZQ, Valenzuela DM, DeChiara TM, Stitt TN, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. Identification of ubiquitin ligases required for skeletal muscle atrophy. Science 294: 1704–1708, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clavel S, Coldefy AS, Kurkdjian E, Salles J, Margaritis I, Derijard B. Atrophy-related ubiquitin ligases, atrogin-1 and MuRF1 are up-regulated in aged rat tibialis anterior muscle. Mech Ageing Dev 127: 794–801, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Costelli P, Muscaritoli M, Bossola M, Penna F, Reffo P, Bonetto A, Busquets S, Bonelli G, Lopez-Soriano FJ, Doglietto GB, Argiles JM, Baccino FM, Fanelli FR. IGF-1 is downregulated in experimental cancer cachexia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 291: R674–R683, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daitoku H, Hatta M, Matsuzaki H, Aratani S, Ohshima T, Miyagishi M, Nakajima T, Fukamizu A. Silent information regulator 2 potentiates Foxo1-mediated transcription through its deacetylase activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 10042–10047, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dehoux M, Gobier C, Lause P, Bertrand L, Ketelslegers JM, Thissen JP. IGF-I does not prevent myotube atrophy caused by proinflammatory cytokines despite activation of Akt/Foxo and GSK-3β pathways and inhibition of atrogin-1 mRNA. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E145–E150, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dehoux M, Van Beneden R, Pasko N, Lause P, Verniers J, Underwood L, Ketelslegers JM, Thissen JP. Role of the insulin-like growth factor I decline in the induction of atrogin-1/MAFbx during fasting and diabetes. Endocrinology 145: 4806–4812, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dogra C, Changotra H, Wedhas N, Qin X, Wergedal JE, Kumar A. TNF-related weak inducer of apoptosis (TWEAK) is a potent skeletal muscle-wasting cytokine. FASEB J 21: 1857–1869, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doucet M, Russell AP, Leger B, Debigare R, Joanisse DR, Caron MA, Leblanc P, Maltais F. Muscle atrophy and hypertrophy signalling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 261–269, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du J, Hu Z, Mitch WE. Cellular signals activating muscle proteolysis in chronic kidney disease: a two-stage process. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 2147–2155, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Essers MA, Weijzen S, de Vries-Smits AM, Saarloos I, de Ruiter ND, Bos JL, Burgering BM. FOXO transcription factor activation by oxidative stress mediated by the small GTPase Ral and JNK. EMBO J 23: 4802–4812, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frost RA, Nystrom GJ, Jefferson LS, Lang CH. Hormone, cytokine, and nutritional regulation of sepsis-induced increases in atrogin-1 and MuRF1 in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E501–E512, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giresi PG, Stevenson EJ, Theilhaber J, Koncarevic A, Parkington J, Fielding RA, Kandarian SC. Identification of a molecular signature of sarcopenia. Physiol Genomics 21: 253–263, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giulietti A, Overbergh L, Valckx D, Decallonne B, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. An overview of real-time quantitative PCR: applications to quantify cytokine gene expression. Methods 25: 386–401, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Glass DJ Signalling pathways that mediate skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy. Nat Cell Biol 5: 87–90, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glass DJ Skeletal muscle hypertrophy and atrophy signaling pathways. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 37: 1974–1984, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haddad F, Adams GR, Bodell PW, Baldwin KM. Isometric resistance exercise fails to counteract skeletal muscle atrophy processes during the initial stages of unloading. J Appl Physiol 100: 433–441, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hardin BJ, Campbell KS, Smith JD, Arbogast S, Smith JL, Moylan JS, Reid MB. TNF-α ACTS VIA TNFR1 and muscle-derived oxidants to depress myofibrillar force in murine skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 104: 694–699, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hasselgren PO, Fischer JE. Muscle cachexia: current concepts of intracellular mechanisms and molecular regulation. Ann Surg 233: 9–17, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jagoe RT, Lecker SH, Gomes M, Goldberg AL. Patterns of gene expression in atrophying skeletal muscles: response to food deprivation. FASEB J 16: 1697–1712, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kamei Y, Mizukami J, Miura S, Suzuki M, Takahashi N, Kawada T, Taniguchi T, Ezaki O. A forkhead transcription factor FKHR up-regulates lipoprotein lipase expression in skeletal muscle. FEBS Lett 536: 232–236, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kandarian SC, Jackman RW. Intracellular signaling during skeletal muscle atrophy. Muscle Nerve 33: 155–165, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi Y, Furukawa-Hibi Y, Chen C, Horio Y, Isobe K, Ikeda K, Motoyama N. SIRT1 is critical regulator of FOXO-mediated transcription in response to oxidative stress. Int J Mol Med 16: 237–243, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lecker SH, Jagoe RT, Gilbert A, Gomes M, Baracos V, Bailey J, Price SR, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Multiple types of skeletal muscle atrophy involve a common program of changes in gene expression. FASEB J 18: 39–51, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lecker SH, Solomon V, Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Muscle protein breakdown and the critical role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in normal and disease states. J Nutr 129: 227S–237S, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee SW, Dai G, Hu Z, Wang X, Du J, Mitch WE. Regulation of muscle protein degradation: coordinated control of apoptotic and ubiquitin-proteasome systems by phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase. J Am Soc Nephrol 15: 1537–1545, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leger B, Vergani L, Soraru G, Hespel P, Derave W, Gobelet C, D'Ascenzio C, Angelini C, Russell AP. Human skeletal muscle atrophy in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis reveals a reduction in Akt and an increase in atrogin-1. FASEB J 20: 583–585, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lengyel F, Vertes Z, Kovacs KA, Kornyei JL, Sumegi B, Vertes M. Effect of estrogen and inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase on Akt and FOXO1 in rat uterus. Steroids 72: 422–428, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li P, Waters RE, Redfern SI, Zhang M, Mao L, Annex BH, Yan Z. Oxidative phenotype protects myofibers from pathological insults induced by chronic heart failure in mice. Am J Pathol 170: 599–608, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li YP, Chen Y, John J, Moylan J, Jin B, Mann DL, Reid MB. TNF-alpha acts via p38 MAPK to stimulate expression of the ubiquitin ligase atrogin1/MAFbx in skeletal muscle. FASEB J 19: 362–370, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li YP, Lecker SH, Chen Y, Waddell ID, Goldberg AL, Reid MB. TNF-alpha increases ubiquitin-conjugating activity in skeletal muscle by up-regulating UbcH2/E220k. FASEB J 17: 1048–1057, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li YP, Reid MB. NF-κB mediates the protein loss induced by TNF-α in differentiated skeletal muscle myotubes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279: R1165–R1170, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Littlewood TD, Hancock DC, Danielian PS, Parker MG, Evan GI. A modified oestrogen receptor ligand-binding domain as an improved switch for the regulation of heterologous proteins. Nucleic Acids Res 23: 1686–1690, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods 25: 402–408, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mitch WE, Goldberg AL. Mechanisms of muscle wasting. The role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. N Engl J Med 335: 1897–1905, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moylan JS, Reid MB. Oxidative stress, chronic disease, and muscle wasting. Muscle Nerve 35: 411–429, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogawa T, Furochi H, Mameoka M, Hirasaka K, Onishi Y, Suzue N, Oarada M, Akamatsu M, Akima H, Fukunaga T, Kishi K, Yasui N, Ishidoh K, Fukuoka H, Nikawa T. Ubiquitin ligase gene expression in healthy volunteers with 20-day bedrest. Muscle Nerve 34: 463–469, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Powers SK, Kavazis AN, McClung JM. Oxidative stress and disuse muscle atrophy. J Appl Physiol 102: 2389–2397, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sacheck JM, Hyatt JP, Raffaello A, Jagoe RT, Roy RR, Edgerton VR, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Rapid disuse and denervation atrophy involve transcriptional changes similar to those of muscle wasting during systemic diseases. FASEB J 21: 140–155, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sakamoto K, Hirshman MF, Aschenbach WG, Goodyear LJ. Contraction regulation of Akt in rat skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem 277: 11910–11917, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandri M, Sandri C, Gilbert A, Skurk C, Calabria E, Picard A, Walsh K, Schiaffino S, Lecker SH, Goldberg AL. Foxo transcription factors induce the atrophy-related ubiquitin ligase atrogin-1 and cause skeletal muscle atrophy. Cell 117: 399–412, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schulze PC, Fang J, Kassik KA, Gannon J, Cupesi M, MacGillivray C, Lee RT, Rosenthal N. Transgenic overexpression of locally acting insulin-like growth factor-1 inhibits ubiquitin-mediated muscle atrophy in chronic left-ventricular dysfunction. Circ Res 97: 418–426, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Smith MA, Moylan JS, Smith JD, Li W, Reid MB. IFN-γ does not mimic the catabolic effects of TNF-α. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1947–C1952, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Somwar R, Sumitani S, Taha C, Sweeney G, Klip A. Temporal activation of p70 S6 kinase and Akt1 by insulin: PI 3-kinase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 275: E618–E625, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stitt TN, Drujan D, Clarke BA, Panaro F, Timofeyva Y, Kline WO, Gonzalez M, Yancopoulos GD, Glass DJ. The IGF-1/PI3K/Akt pathway prevents expression of muscle atrophy-induced ubiquitin ligases by inhibiting FOXO transcription factors. Mol Cell 14: 395–403, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Urso ML, Chen YW, Scrimgeour AG, Lee PC, Lee KF, Clarkson PM. Alterations in mRNA expression and protein products following spinal cord injury in humans. J Physiol 579: 877–892, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Horst A, de Vries-Smits AM, Brenkman AB, van Triest MH, van den Broek N, Colland F, Maurice MM, Burgering BM. FOXO4 transcriptional activity is regulated by monoubiquitination and USP7/HAUSP. Nat Cell Biol 8: 1064–1073, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van der Horst A, Tertoolen LG, de Vries-Smits LM, Frye RA, Medema RH, Burgering BM. FOXO4 is acetylated upon peroxide stress and deacetylated by the longevity protein hSir2(SIRT1). J Biol Chem 279: 28873–28879, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wray CJ, Mammen JM, Hershko DD, Hasselgren PO. Sepsis upregulates the gene expression of multiple ubiquitin ligases in skeletal muscle. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 35: 698–705, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]