Abstract

A huge amount of cDNA and EST resources have been developed for cultivated rice species Oryza sativa; however, only few cDNA resources are available for wild rice species. In this study, we isolated and completely sequenced 1888 putative full-length cDNA (FLcDNA) clones from wild rice Oryza rufipogon Griff. W1943 for comparative analysis between wild and cultivated rice species. Two cDNA libraries were constructed from 3-week-old leaf samples under either normal or cold-treated conditions. Homology searching of these cDNA sequences revealed that >96.8% of the wild rice cDNAs were matched to the cultivated rice O. sativa ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare genome sequence. However, <22% of them were fully matched to the cv. Nipponbare genome sequence. The comparative analysis showed that O. rufipogon W1943 had greater similarity to O. sativa ssp. japonica than to ssp. indica cultivars. In addition, 17 novel rice cDNAs were identified, and 41 putative tissue-specific expression genes were defined through searching the rice massively parallel signature-sequencing database. In conclusion, these FLcDNA clones are a resource for further function verification and could be broadly utilized in rice biological studies.

Key words: wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, full-length cDNA, transcriptome comparison, tissue-specific expression

1. Introduction

The wild rice species Oryza rufipogon Griff. (AA genome) is the most closely related ancestral species to Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa L.).1,2 It contains various valuable traits with regard to tolerance to cold, drought and salinity. It also contains many quantitative trait loci with agronomic important traits.3,4 However, cultivated rice, which feeds more than half of the world's population, is often threatened by multifarious environmental factors including drought, salinity, cold and other factors. The O. sativa ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare genome has been completely sequenced through a map-based sequencing strategy.5 The draft genome sequence of the O. sativa ssp. indica cv. 93-11 was also generated through a whole-genome shotgun sequencing approach.6 The Rice Full-Length cDNA Consortium collected over 28 000 full-length complementary DNA (FLcDNA) clones from cv. Nipponbare.7 Now, there are >47 000 cultivated rice FLcDNA sequences publicly available (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/). There is also a collection of 10 096 FLcDNAs of O. sativa ssp. indica cv. Guangluai 4.8 Moreover, comparative genome analysis has been developed to decipher the similarity and diversity among rice varieties, using single nucleotide polymorphisms data in 21 rice genomes.9 Comparative analysis with cultivated rice cDNA sequences has also been developed using the microarray method.10 In contrast, for wild rice, there are few batches of mRNAs and FLcDNAs in public databases, with the exception of 5211 leaf ESTs from the O. minuta (BBCC genome).11

Oryza rufipogon has been classified into perennial and annual ecotypes.12 W1943 is a perennial O. rufipogon. For the first time, a total of 1888 FLcDNAs of O. rufipogon W1943 were generated in the present study; most (>96.8%) were highly homologous with cultivated rice genome sequences. Furthermore, W1943 had greater similarity to ssp. japonica than to ssp. indica. Additionally, 1% of W1943 FLcDNAs was verified as novel rice genes not previously reported. We also discovered 41 putative tissue-specific expressed genes by applying the rice massively parallel signature-sequencing (MPSS) database.13

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant materials and cDNA library construction

Two enriched FLcDNA libraries were constructed from wild rice O. rufipogon Griff. W1943. Seeds were germinated and seedlings were grown in a greenhouse with day/night of 13/11 h and 25/30°C. Three weeks after germination, some seedlings were exposed to 5°C and leaves were separately harvested after 0, 1, 12, 24, 48, 72 and 120 h of cold treatment. We constructed two cDNA libraries from 3-week-old rice leaves grown under normal and cold conditions, respectively. All samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C.

We constructed two FLcDNA libraries according to the Cap-Tagging8 and Cap-trapper methods.14 The 5′ cap-tagging method utilizes the 5′ cap-capture technique through the combined treatments of calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) and tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP) so that only the FLcDNA was targeted for library construction. The cap-trapper method is based on chemical introduction of a biotin group into the diol residue of the cap structure of mRNA, which is followed by RNase I treatment to select FLcDNA. Total RNA was isolated using the TRIZOL reagents, and mRNAs were purified with the Oligotex mRNA kit (Qiagen). Double-stranded cDNA was digested with EcoRI (1 U) and XhoI (10 U) for 1 h at 37°C, and cDNA fraction of 0.6–2 kb was collected and pooled, with which ligated to the sites of EcoRI and XhoI of vector pBluescript SK+ (Strategene) at 16°C overnight. Then, cDNA was transformed into competent E. coli DH10B cells (Invitrogen) by electroporation. We assessed the library quality by assaying ligations and carrying out 5′-end sequencing; the former procedure determined library titer, and the latter used to evaluate cDNA full-length percentage as well as the proportion of empty vectors.

2.2. DNA sequencing and assembling

DNA sequencing was carried out on ABI3730 sequencers. The clones were sequenced from both ends by the dideoxy chain termination method using BigDye Terminator Cycle sequencing V2.0 Ready Reaction (Applied Biosystems). The Phred base-calling software was used to analyze sequence trace files and generate raw sequences.15 Peaks with Phred quality values of <20 were taken as ambiguous sequences and were presented by a universal placeholder ‘N’. Vector sequences were filtered automatically. Then, all 5′-tagged sequences were selected by a Perl script for clustering, which used the TGICL program.16 These singletons and every representative clone from each contig were selected to be completely sequenced by bidirectional sequencing strategy. All processed sequences were assembled by Phrap software.

Accession numbers for submitted data in the EMBL database CT841557–CT841684; CT841686–CT841707; CT841710–CT841954; CT841956–CT842008; CU405560–CU405627; CU405629–CU405654; CU405656–CU405706; CU405708–CU405710; CU405712–CU405714; CU405716–CU405717; CU405719–CU405720; CU405722–CU405729; CU405731–CU405880; CU405882–CU405928; CU405930–CU406064; CU406066–CU406249; CU406251–CU406335; CU406337–CU406954 and CU861673–CU861883.

These W1943 sequences are available from our website (http://202.127.18.228/ricd/dym/ftp.php).

2.3. Comparative analysis of FLcDNA sequences

Similarity searches were performed with BLAST (version 2.2.14) program17 against sequence data as follows: NCBI GenBank nt DB (2007-12), nr DB (2007-12), est-other DB (2007-07), rice japonica genomic sequence (http://rgp.dna.affrc.go.jp/IRGSP/), the Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) rice cDNA data (release 4.0), TIGR_Oryza_Repeats_v3.1, Knowledge-based Oryza Molecular Biological Encyclopedia japonica cDNA collection (http://cdna01.dna.affrc.go.jp/cDNA, 2006-10-11) and National Center for Gene Research (NCGR, http://www.ncgr.ac.cn/ricd) Rice Indica cDNA Database (RICD). We downloaded all above sequence data and used our 1888 clones as query sequences. The similarity threshold of E-value was lower than 1E−10. We searched InterPro database18 to compare the profiles of proteins encoded in W1943 FLcDNAs. Functional classification of cDNAs was referred to PFAM profiles.19

A similarity-based tool sim420 was used to align W1943 FLcDNA sequence with rice genomic sequence. It was also used to identify and discard redundant gene sequences. Open reading frames (ORFs) of cDNA sequences were determined by using getorf program of EMBOSS package.21 The rice MPSS database13 was used for quantitative expression analysis of these W1943 cDNAs in rice. The expression levels were calculated for rice different tissues or same tissues at different developmental stages by summing all expressed tags in the sense strand. To calculate synonymous divergence (Ks), program ClustalX 1.822 and PAL2NAL (version: V11)23 were applied.

Rfam database24 (http://www.sanger.ac.uk/Software/Rfam/) and miRBase25 (http://microrna.sanger.ac.uk/) data were downloaded for non-protein-coding transcripts analysis. Software mFOLD was applied to predict pre-miRNAs' secondary structure (http://mfold.bioinfo.rpi.e.du/).26

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall description of W1943 FLcDNA sequences

Two full-length enriched cDNA libraries of O. rufipogon W1943 were constructed following the cap-tagging method.8 Each cDNA library was composed of 1 × 106 independent clones. The average cDNA sizes were 0.5–1.5 kb. In total, we randomly selected 8352 clones (6432 were from the normal rice leaf cDNA library and 1920 were from the cold-stressed rice leaf cDNA library) for 5′-end sequencing. In total, there were 4876 tagged potential FLcDNA clones of at least 100 continuous nucleotides with a Phred score of >20, after removal of vector sequences and low quality reads. The TGICL program16 was used to cluster these 4876 cDNA clones. Thus, there were 2350 cDNAs, consisting of 454 representative unique clone contigs and 1896 singletons, generated for completely sequencing and assembling. Overlapping 5′ and 3′ reads were assembled to consensus sequences through the bidirectional sequencing strategy.

Up to now, we have successfully obtained 1888 non-redundant W1943 cDNA sequences. Of 1888 cDNA sequences, 1360 sequences matched to NCBI GenBank non-redundant database of proteins (nrDB) (E < 1e−10; >70% identity). Of 1360 sequences, 997 cDNAs could fully cover the protein N-terminal first amino acid sequence. Therefore, we estimated that >70% of the 1832 cDNA sequences were FLcDNAs. It should be pointed out that the efficiency of CIP and TAP treatments played a key role in constructing the FLcDNA library. On the other hand, it was also possible that some of the remaining 30% putative truncated cDNA sequences might be genuine FLcDNAs transcribed from alternative start sites. There are lots of alternative transcription start sites known in mammals.27,28

3.2. Mapping of the 1888 W1943 FLcDNAs onto cultivated rice O. sativa genomic sequences

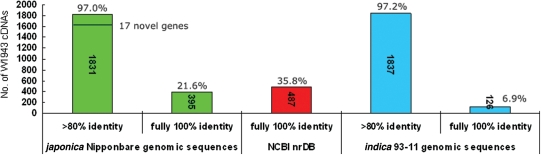

The 1888 FLcDNAs from O. rufipogon W1943 were mapped to O. sativa ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare genomic sequence pseudomolecules (version 4.0) and compared with GenBank nrDB based on BLASTn (E < 1e−10) and BLASTx (E < 1e−10), respectively.5 Of the 1888 FLcDNA sequences, 1831 (97.0%) could be aligned to the japonica genomic sequences at >80% sequence identity over the entire length (Fig. 1). The remaining 57 cDNAs that did not match the ssp. japonica genomic sequences are discussed in the following analysis. Among 1831 W1943 cDNAs, 395 (21.6%) fully matched the ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare genomic sequences with 100% identity at nucleotide level. However, among 1831 cDNAs, 487 fully matched to corresponding proteins in nrDB with 100% identity. Therefore, 35.8% of W1943 cDNAs had full identity to proteins from nrDB at amino acid level. In spite of relatively low full identity at nucleotide acid level (only 21.6%), it was more conservative at amino acid level (>35.8%) between wild and cultivated rice. It was propitious to protect some key proteins from losing their conserved and vital functions.

Figure 1.

Mapping of the 1888 FLcDNAs onto Oryza sativa genomic sequences.

We also mapped the 1888 W1943 FLcDNAs to the O. sativa ssp. indica cv. 93-11 whole-genome shotgun sequences using BLASTn (E < 1e−10). A total of 1837 (97.2%) W1943 cDNAs could be aligned to the cv. 93-11 genome sequences at >80% sequence identity over the entire length (Fig. 1). Of these, 126 (6.9%) identically matched the cv. 93-11 genome sequences. These results indicated that the sequence of wild rice W1943 had a very high similarity with those of cultivated ssp. japonica (97.0%) and ssp. indica (97.2%) rice; and W1943 had greater similarity to japonica than to indica at nucleotide acid level. Monna et al.29 surmised that W1943 was closer to japonica than to indica. It has been reported that japonica cultivars are closely related to the O. rufipogon perennial strains, and indica cultivars closely related to the O. rufipogon annual strains.30 Our results confirmed this conclusion at transcriptional level.

In the case of 395 W1943 FLcDNAs that were 100% matched to the genomic sequences, we checked the splicing patterns by comparing with all rice ESTs or mRNAs in public databases. The results revealed that 15 W1943 cDNAs had alternative splicing patterns when compared with cultivated rice ESTs or mRNAs (Table 1). These alternative splicing patterns might be specific for W1943. Furthermore, the first introns of two genes (CT841942 and CU406810) had a distinct splice site with GC-AG and GT-TG. We concluded that cultivated rice had experienced some mutations including the intron region, and thus some genes were lost over the long evolutionary period. There were four typical alternative splicing patterns of these sequences (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

List of 15 Oryza rufipogon W1943 genes with specific alternative splicing patterns

| Accession Number | Length (bp) | Chromosome | Number of exon | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT841942 | 978 | 07 | 6 (1st intron: GC-AG) | |

| CU406810 | 958 | 06 | 6 (1st intron: GT-TG) | Dual-specificity phosphatase protein |

| CT841893 | 1011 | 01 | 6 | Drought-induced protein |

| CT841874 | 1369 | 01 | 4 | Vesicle transport protein |

| CU405853 | 1377 | 05 | 1 | Dehydration-responsive protein |

| CU405923 | 639 | 07 | 1 | IAA amidohydrolase |

| CU406279 | 648 | 05 | 1 | |

| CU406025 | 839 | 02 | 1 | |

| CT841561 | 740 | 06 | 2 | |

| CU406579 | 468 | 09 | 2 | |

| CU406935 | 1345 | 01 | 2 | |

| CU406600 | 1107 | 01 | 2 | |

| CU405570 | 952 | 01 | 2 | |

| CU406091 | 893 | 01 | 3 | |

| CU406134 | 665 | 10 | 3 |

Figure 2.

Total 17 W1943 cDNAs had alternative splicing patterns different from previous ESTs or mRNAs in public database. It revealed four typical splicing patterns in wild rice species.

It should be pointed out that 10 of 1831 W1943 cDNAs had no hits to previously reported rice ESTs or mRNAs in GenBank database (Table 2). Another seven cDNAs had hits to rice ESTs or mRNAs at the sense–antisense pattern (Table 3). So these cDNA sequences offered novel rice transcripts to public database. As for the 17 W1943 cDNA sequences, they were either wild-rice-specific genes or cultivated rice co-owner genes. If the latter was the case, it may indicate that these genes are expressed at much lower levels in cultivated than in wild rice. Hence, it would be difficult to clone these cDNAs from cultivated rice in spite of a total of ∼47 000 ssp. japonica and ssp. indica cDNAs available in the current public database (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/). We used the rice MPSS database (http://mpss.udel.edu/rice/) to detect the expression level of these 17 putative novel W1943 cDNAs under different conditions.13 The results showed that 15 of 17 cDNAs were not detected having expressed tags with sense strand orientation in different tissues. Gene ‘CU861721’ was found only 18 times per million (tpm) in young leaves and gene ‘CU406355’ was found >100 tpm in young roots and germinating seedlings.

Table 2.

List of 10 novel cDNA transcripts of Oryza rufipogon W1943

Table 3.

List of seven sense–antisense cDNA transcripts of Oryza rufipogon W1943

| Accession Number | Length (bp) | Protein | Location (chr) | Identity (%) | Antisense gene | Location (chr) | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CU405785 | 727 | — | 05 | 99 | CA764081 | 01 | DNA-directed RNA polymerase 3 |

| CU861795 | 475 | — | 09 | 79 | CT858901 | unsure | Unknown |

| CU406355 | 837 | — | 12 | 97 | AK107125 | 12 | AP2 domain, putative |

| CU406396 | 520 | — | 02 | 99 | AK103485 | 02 | Hypothetical |

| CT841800 | 941 | — | 11 | 99 | AK121962 | 11 | Patatin, putative |

| CU861688 | 693 | — | 08 | 99 | AK109182 | 08 | Hypothetical |

| CT841937 | 1552 | — | 08 | 98 | AK106713 | 08 | Unknown |

In addition, 57 W1943 cDNAs that could not be aligned to the ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare genomic sequence were further analyzed. After comparing with other public databases, 14 of them matched the ssp. indica cv. 93-11 genomic sequences, 6 matched to rice ESTs in NCBI est-other database, 4 had similarity to Sorghum bicolor, Triticum aestivum, Manihot esculenta and Spartina alterniflora ESTs, 15 were homologs to Gibberella moniliformis, Gibberella zeae and Magnaporthe grisea, and the remaining 18 had no hits. Table 4 listed 24 W1943 cDNAs' information after excluding 15 possible contamination clones and 18 no any hits clones. Several W1943 cDNAs that did not match to the cv. Nipponbare genomic sequence might be located in the gap of genomic sequence or might be related to wild rice W1943-specific genes.

Table 4.

List of 24 no-hit Oryza sativa ssp. japonica genome sequences

| Number | Accession Number | japonica chromosome | 93–11 location | ESTs or mRNA hits | Protein |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | CT842002 | — | Contig005912 | AK241925.1 | — |

| 2 | CT842007 | — | Contig008507 | CT856206 | — |

| 3 | CU405940 | — | Contig001402 | AK103326 | Unknown protein |

| 4 | CU406172 | — | Contig014596 | AK242967.1 | — |

| 5 | CT842006 | — | Contig000383 | AK111647 | GTP-binding protein |

| 6 | CU861753 | — | Contig000750 | AK099287 | Ring-box protein |

| 7 | CU406308 | — | Contig000444 | AK070131 | Unknown protein |

| 8 | CT841996 | — | Contig002576 | CT834800 | Unknown protein |

| 9 | CU406568 | — | Contig003848 | AK064050 | Bowman Birk trypsin inhibitor |

| 10 | CU406582 | — | Contig000444 | AK107776 | Unknown protein |

| 11 | CU406596 | — | Contig001277 | AK242711.1 | Hypothetical protein |

| 12 | CT842008 | — | Contig008507 | CT856206 | Unknown protein |

| 13 | CU406895 | — | Contig003011 | CT859459 | Hypothetical protein |

| 14 | CU861744 | — | Contig000750 | AK099287 | Ring-box protein |

| 15 | CU405657 | — | — | CT856885 | — |

| 16 | CT841712 | — | — | CA766528 | — |

| 17 | CU405768 | — | — | CT836656 | 60S ribosomal protein L7A |

| 18 | CU405675 | — | — | CA756235 | 60S ribosomal protein L17 |

| 19 | CU406202 | — | — | NM_001063334 | Unknown |

| 20 | CU406924 | — | — | AC145809 | — |

| 21 | CU405898 | — | — | CN130755.1 (Sorghum bicolor) | Ribulose-bisphosphate carboxylase |

| 22 | CU406778 | — | — | BE429292.1 (Triticum turgidum) | Hydrophobin |

| 23 | CU861677 | — | — | FF534517.1 (Manihot esculenta) | Hypothetical protein |

| 24 | CT841912 | — | — | EH277383.1 (Spartina alterniflora) | Unknown protein |

3.3. Comparative analysis with cultivated rice cDNA sequences in public databases

The 1888 W1943 cDNAs were compared with cultivated rice cDNA sequences. The large-scale rice ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare cDNA sequences have been released to public databases.7 Recently, another batch of rice ssp. indica cv. Guangluai 4 cDNA sequences was released to public databases (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/; http://www.ncgr.ac.cn/RICD).8 We compared these two major cultivated rice varieties' cDNAs with 1888 W1943 cDNA sequences. For convenience, here we named cv. Nipponbare cDNA sequences as KOME (knowledge-based oryza molecular biological encyclopedia) and cv. Guangluai 4 cDNA sequences as NCGR (National Center for Gene Research, CAS). At present, there are 35 187 ssp. japonica FLcDNA sequences in KOME, and 10 096 ssp. indica FLcDNA sequences in NCGR.

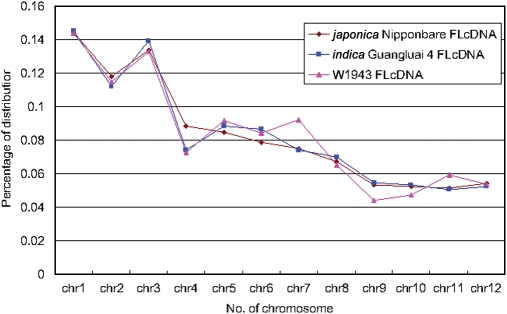

Initially, we identified chromosomal distributions of the three different rice cDNAs along the cv. Nipponbare chromosomal pseudomolecules (Fig. 3). Though there were relatively small quantities of W1943 cDNAs, there were similar trace trends and no visible large bias comparing KOME and NCGR cDNAs. So the 1888 W1943 cDNAs can give clues to the entire W1943 genome.

Figure 3.

Chromosomal distributions of the three different rice cDNAs (W1943, KOME, NCGR) along the ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare chromosomal pseudomolecule sequences. Though relative small quantities of W1943 cDNAs, it had about similar trace trends and no visible large bias comparing with KOME and NCGR (KOME, Oryza sativa ssp. japonica Nipponbare cDNAs; NCGR, Oryza sativa ssp. indica Guangluai 4 cDNAs.).

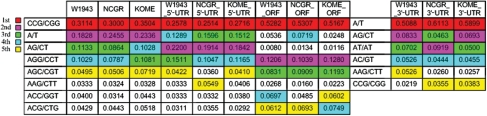

A Perl script known as MISA (http://pgrc.ipk-gatersleben.de/misa/) was used to identify simple sequence repeats (SSRs) in these cDNA sequences. We described all SSR motifs of 1–6 nucleotides in size. The minimum repeat unit was prescribed as follows: 10 repeats for mononucleotides, 6 for di-nucleotides and 5 for all the other motifs such as tri-, tetra-, penta- and hexa-nucleotides. We detected the five highest frequencies of SSR motifs of the overall cDNA sequences, 5′-UTR sequences, ORF sequences and 3′-UTR sequences, respectively (Fig. 4). The highest frequencies of the SSR motifs in the three different rice cDNAs were identical in 5′-UTR, ORF or 3′-UTR regions. First, the motif CCG/CGG has the highest frequencies in 5′-UTR and ORF regions, but the SSR motif A/T has the highest frequency in 3′-UTR region. Second, all kinds of motif types were unevenly distributed in the FLcDNA sequences. The motifs CCG/CGG and A/T were more frequent in the ORF and 3′-UTR regions, respectively, with frequencies >50%. However, in 5′-UTR regions, the most frequent SSR motifs were ≤28%. In addition, scanning showed that the three most frequent SSR motif-types in ORF regions were all triplets that differed from those in UTR regions. This difference was very important for coding sequence because tri-nucleotide SSR motif-types could effectively prevent amino acid from frame shifting. Furthermore, the five most frequent SSR motifs were all triplets; the only exception was the fourth most frequent SSR type of NCGR, which was A/T (7.19%). In the process of evolution, relative higher frequency of mononucleotide SSR motifs of NCGR ORF was likely to be one key factor that led to divergence of ssp. indica and ssp. japonica. This could partly explain why W1943 was closer to japonica than to indica.

Figure 4.

The first five highest frequency SSR motifs in the overall cDNA sequences, 5′-UTR sequences, ORF sequences and 3′-UTR sequences, respectively.

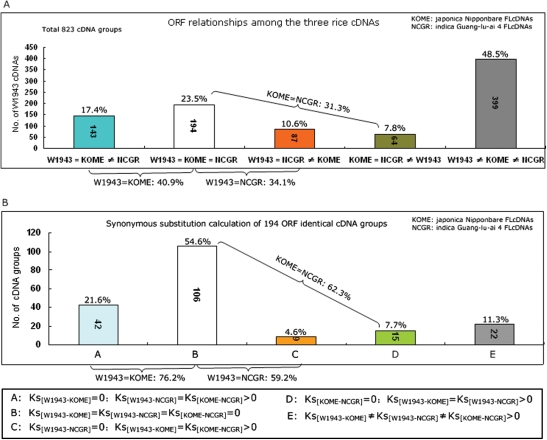

We carried out transcripts comparisons between W1943 and the other two cultivated rice subspecies (Fig. 5). A total of 823 W1943 cDNAs were detected according to their homology with both KOME and NCGR (≥95% identity and non-redundant hit to KOME and NCGR). We extracted the ORF of each cDNA sequence using the getorf program.21 The amino acid levels in a total of 194 ORF groups were all identical (Fig. 5A), 143 ORF groups were specifically identical between W1943 and KOME, 87 ORF groups were specifically identical between W1943 and NCGR, and 64 ORF groups were specifically identical between KOME and NCGR. Consequently, 40.9% of transcripts were conserved in wild rice W1943 and cultivated rice ssp. japonica cv. Nipponbare; 34.1% were conserved in W1943 and cultivated rice ssp. indica cv. Guangluai 4 and 31.3% were conserved in cvs. Nipponbare and Guangluai 4.

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis with Oryza sativa cDNA sequences in public databases. (A) The relationships of ORFs among 823 W1943, KOME and NCGR co-cDNA groups at amino acid level. (B) The synonymous divergent (Ks) relationships of 194 ORF identical cDNA groups.

The nucleotides of 194 identical ORF groups were extracted for further calculation of synonymous substitution rates. The results showed that 106 of 194 (54.6%) groups were also completely identical at nucleotide level. So the remaining 88 groups were used to calculate synonymous divergence (Ks) (Fig. 5B). Of 88 groups, 42 groups had no synonymous substitution between W1943 and KOME; 9 groups had no synonymous substitution between W1943 and NCGR; 15 groups had no synonymous substitution between KOME and NCGR and another 22 groups had synonymous substitutions among the three species and subspecies. That is, at nucleotide level, 76.2% of 194 identical ORF groups had no changes in W1943 and cv. Nipponbare, and 59.2% for W1943 and cv. Guangluai 4.

It was reported29 that the rates of polymorphisms in predicted intergenic regions of rice were 0.302 (W1943/Nipponbare), 0.653 (W1943/Guangluai 4) and 0.630 (Nipponbare/Guangluai 4), respectively. These were similar to results in coding sequence regions in the present study. Thus, the hypothesis that O. rufipogon W1943 was closer to ssp. japonica than to ssp. indica was further validated.

3.4. miRNAs identification

After searching against NCBI nrDB using BLASTx, 432 sequences of 1888 W1943 cDNAs found no hits in the database. Of 432 sequences, 71 were predicted as ORFs > 100 amino acid in length, so the remaining 361 were assumed to be putative non-protein-coding transcripts. Searching against Rfam database and miRBase, four cDNAs matched to four miRNA families; the osa-MIR159a, osa-MIR156j, osa-MIR818e and osa-miR446 families, respectively (Table 5). Using the mFOLD program, all four sequences could be predicted to pre-miRNA secondary structure and identified as miRNAs according to folding results.

Table 5.

List of 4 miRNAs

| Accession Number | Gene length (bp) | Pre-miRNA length (bp) | Hit-miRNA | miRNA seq | Chromosome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CU406292 | 1416 | 262 (220–490) | osa-MIR159a | uuuggauugaagggagcucug | 01 |

| CU405943 | 1511 | 101 (160–280) | osa-MIR156j | ugacagaagagagugagcac | 06 |

| CU861819 | 561 | 80 (390–470) | osa-miR818e | aaucccuuauauuuugggacgg | 04 |

| CU861752 | 727 | 150 (325–475) | osa-miR446 | aucaauaugaaugugggaaau | 10 |

3.5. Expression analysis by searching against the rice MPSS database

We used the rice MPSS database (http://mpss.udel.edu/rice/) to detect the expression level of W1943 cDNAs under different conditions.13 To define tissue-specific genes, we demarcated the qualifications as follows: (i) the expression level of every gene should >100 tpm of at least one tissue; (ii) if the gene expressed in several diverse tissues, then the highest expression level should be >75% among all tissues and (iii) the ratio of the first two highest expression levels should be >10. Thus, we identified 41 putative tissue-specific genes (Table 6). There were 16 W1943 cDNAs expressed remarkably highly in leaves, 11 cDNAs specifically in roots, 1 in germinating seed, 3 in callus, 7 in germinating seedlings, 1 in meristematic tissue and 2 in mature pollen. Searching against the PFAM protein database, we found that gene ‘CU406902’ was predicted as ‘Lir1, light regulated protein Lir1’. Lir1 mRNA can accumulate in the light, reaching maximum and minimum steady-state levels at the end of the light and dark periods.31 Another gene ‘CT841733’ was predicted as ‘RuBisCO_small’ (ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase small subunit). Although the RuBisCO large subunit is coded for by a single gene, the small subunit is coded for by several different genes, which are distributed in a tissue-specific manner. They are transcriptionally regulated by light receptor phytochrome, which results in RuBisCO being more abundant during the day when it is required.32

Table 6.

List of Oryza rufipogon W1943 tissue-specific genes (unit: tpm)

| Clone Acc. | Leaf | Root | NGS | NCA | NGD | NME | NPO | PFAM Acc. | Description | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CU406902 | 44 199 | 0 | 101 | 0 | 19 | 0 | 0 | PF07207 | Lir1 | 4.8e–85 |

| CU405979 | 36 785 | 0 | 894 | 0 | 256 | 9 | 0 | |||

| CT841733 | 25 112 | 41 | 120 | 0 | 241 | 0 | 0 | PF00101 | RuBisCO_small | 2.5e–45 |

| CU405975 | 15 421 | 1278 | 0 | 0 | 650 | 223 | 0 | |||

| CT841994 | 9140 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU406521 | 3504 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PF01070 | FMN_dh | 2.8e–31 |

| CU405996 | 3069 | 0 | 27 | 0 | 28 | 15 | 0 | PF00430 | ATP-synt_B | 3.4e–28 |

| CU405670 | 2653 | 0 | 11 | 5 | 21 | 4 | 23 | PF00085 | Thioredoxin | 7.8e–43 |

| CU406006 | 2337 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | |||

| CU406668 | 2126 | 3 | 17 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CT841650 | 1997 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PF00112 | Peptidase_C1 | 6e–109 |

| CT841731 | 1942 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | PF02507 | PSI_PsaF | 0 |

| CT841902 | 1486 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 31 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU405952 | 1253 | 7 | 110 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 0 | |||

| CU406199 | 1235 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU406624 | 1012 | 0 | 60 | 58 | 0 | 3 | 5 | PF05899 | DUF861 | 2.1e–37 |

| CU406431 | 0 | 189 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 17 | |||

| CU405706 | 1456 | 15 907 | 0 | 183 | 803 | 0 | 0 | PF01439 | Metallothio_2 | 2.7e–32 |

| CU406330 | 0 | 358 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 31 | |||

| CT841629 | 217 | 2721 | 157 | 36 | 80 | 25 | 86 | PF01124 | MAPEG | 3.1e–63 |

| CU406513 | 18 | 230 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PF01439 | Metallothio_2 | 1.6e–34 |

| CU406576 | 0 | 231 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU406281 | 29 | 449 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | |||

| CT841966 | 15 | 520 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PF00188 | SCP | 5.7e–55 |

| CU405942 | 0 | 185 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PF00967 | Barwin | 3e–84 |

| CU406520 | 5 | 1209 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU406670 | 0 | 189 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | PF00280 | Potato_inhibit | 1.4e–20 |

| CU406238 | 41 | 0 | 987 | 33 | 31 | 0 | 0 | PF04398 | DUF538 | 4.9e–41 |

| CT841875 | 16 | 0 | 0 | 162 | 3 | 3 | 15 | |||

| CT841950 | 119 | 135 | 76 | 3079 | 107 | 19 | 0 | |||

| CT841815 | 107 | 135 | 76 | 3087 | 107 | 19 | 0 | |||

| CU406940 | 59 | 68 | 19 | 31 | 1393 | 4 | 0 | PF02065 | Melibiase | 3.5e–13 |

| CU406598 | 565 | 0 | 606 | 757 | 16 965 | 0 | 0 | PF00234 | Tryp_alpha_amyl | 1.6e–31 |

| CU406533 | 7 | 0 | 14 | 30 | 4662 | 119 | 0 | PF00234 | Tryp_alpha_amyl | 5.5e–33 |

| CU406609 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 143 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU406264 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 237 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU405759 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 779 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU406038 | 14 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 247 | 0 | 0 | |||

| CU405951 | 0 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 1347 | 0 | PF01439 | Metallothio_2 | 6.5e–22 |

| CU406698 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 289 | PF00481 | PP2C | 2.4e–14 |

| CU406351 | 103 | 4 | 36 | 66 | 48 | 42 | 3228 |

NGS, 3 days—Germinating seed; NCA, 35 days—Callus; NGD, 10 days—Germinating seedlings grown in dark; NME, 60 days—Crown vegetative meristematic tissue; NPO, mature pollen.

In the similar restricted conditions as above, there were seven W1943 cDNAs with distinct expression level in leaves exposed to cold, drought or salinity stresses (Table 7). Of the seven cDNAs, four genes were up-regulated by cold stress, two genes were up-regulated by drought and one gene was up-regulated by salinity. It should be pointed out that gene ‘CU405946’ matched to PFAM protein annotated as ‘Dehydrin’. This protein is produced by plants that experience water-stress.33

Table 7.

List of seven cDNAs preferentially expressed under cold-stress, drought-stress and salinity in leaf (unit: tpm)

| Clone Acc. | Normal leaf | NCL | NDL | NSL | PFAM Acc. | Description | E-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CU406310 | 96 | 2872 | 3 | 255 | Null | Null | Null |

| CT841781 | 96 | 3089 | 3 | 257 | Null | Null | Null |

| CT841558 | 102 | 2404 | 2 | 365 | Null | Null | Null |

| CU406554 | 11 | 568 | 0 | 83 | Null | Null | Null |

| CT841576 | 303 | 0 | 3435 | 68 | PF00234 | Tryp_alpha_amyl | 4.6e–33 |

| CU406485 | 0 | 0 | 1477 | 0 | Null | Null | Null |

| CU405946 | 0 | 113 | 0 | 591 | PF00257 | Dehydrin | 2.2e–54 |

NCL, 14 days—Young leaves stressed in 4°C cold for 24 h; NDL, 14 days—Young leaves stressed in drought for 5 days; NSL, 14 days—Young leaves stressed in 250 mM NaCl for 24 h.

3.6. Conclusions

In this research, we collected and completely sequenced 1888 putative FLcDNAs of wild rice O. rufipogon Griff. W1943. A total of 17 novel rice cDNAs and 41 putative tissue-specific expression genes were identified. The comparative analysis between wild rice and two cultivated rice subspecies indicated that O. rufipogon W1943 had greater similarity to O. sativa ssp. japonica than to ssp. indica cultivars. It is reported that W1943 is primarily distributed in Dongxiang (26°14'N, 116°36'E) of Jiangxi Province in China.34 It is found to be the northern most distribution of O. rufipogon at present time.35 Both cultivated rice O. sativa ssp. japonica and indica have distributions in this area. The geological distribution of W1943 can also provide some clues for further analysis between wild and cultivated rices.

Funding

This research was supported by the grants from the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (the China Rice Functional Genomics Programs, 2005CB120805 and 2006AA10A102), the Chinese Academy of Sciences (038019315 and KSCX2-YW-N-024) and the Shanghai Municipal Commission of Science and Technology.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Plant Genome Center (Tsukuba, Japan) for kindly providing seeds of W1943.

References

- 1.Wang Z. Y., Second G., Tanksley S. D. Polymorphism and phylogenetic relationships among species in the genus Oryza as determined by analysis of nuclear RFLPs. Theor. Appl. Genet. 1992;83:565–581. doi: 10.1007/BF00226900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Londo J. P., Chiang Y. C., Hung K. H., Chiang T. Y., Schaal B. A. Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestications of cultivated rice, Oryza sativa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:9578–9583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603152103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang X., Zhou S., Fu Y., Su Z., Wang X., Sun C. Identification of a drought tolerant introgression line derived from Dongxiang common wild rice (O. rufipogon Griff.) Plant Mol. Biol. 2006;62:247–259. doi: 10.1007/s11103-006-9018-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian F., Zhu Z., Zhang B.,, et al. Fine mapping of a quantitative trait locus for grain number per panicle from wild rice (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) Theor. Appl. Genet. 2006;113:619–629. doi: 10.1007/s00122-006-0326-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Rice Genome Sequencing Project, The map-based sequence of the rice genome. Nature. 2005;436:793–800. doi: 10.1038/nature03895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yu J., Hu S., Wang J.,, et al. A draft sequence of the rice genome Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica. Science. 2002;296:92–100. doi: 10.1126/science.1068037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Rice Full-Length cDNA Consortium, Collection, mapping, and annotation of over 28,000 cDNA clones from japonica rice. Science. 2003;301:376–379. doi: 10.1126/science.1081288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu X., Lu T., Yu S.,, et al. A collection of 10,096 indica rice full-length cDNAs reveals highly expressed sequence divergence between Oryza sativa indica and japonica subspecies. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;65:403–415. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McNally K. L., Bruskiewich R., Mackill D., Buell C. R., Leach J. E., Leung H. Sequencing multiple and diverse rice varieties. Connecting whole-genome variation with phenotypes. Plant Physiol. 2006;141:26–31. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.077313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satoh K., Doi K., Nagata T.,, et al. Gene organization in rice revealed by full-length cDNA mapping and gene expression analysis through microarray. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho S. K., Ok S. H., Jeung J. U.,, et al. Comparative analysis of 5,211 leaf ESTs of wild rice (Oryza minuta) Plant Cell Rep. 2004;22:839–847. doi: 10.1007/s00299-004-0764-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Morishima H., Sano Y., Oka H. I. Evolutionary studies in cultivated rice and its wild relatives. Oxford Surv. Evol. Biol. 1992;8:135–184. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakano M., Nobuta K., Vemaraju K., Tej S. S., Skogen J. W., Meyers B. C. Plant MPSS databases: signature-based transcriptional resources for analyses of mRNA and small RNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:731–735. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carninci P., Kvam C., Kitamura A.,, et al. High-efficiency full-length cDNA cloning by biotinylated CAP trapper. Genomics. 1996;37:327–336. doi: 10.1006/geno.1996.0567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ewing B., Green P. Base-calling of automated sequencer traces using phred. II. Error probabilities. Genome Res. 1998;8:186–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pertea G., Huang X., Liang F.,, et al. TIGR gene Indices clustering tools (TGICL): a software system for fast clustering of large EST datasets. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:651–652. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altschul S. F., Madden T. L., Schaffer A. A.,, et al. Gapped BLAST and PSI-BLAST: a new generation of protein database search Programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:3389–3402. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.17.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apweiler R., Attwood T. K., Bairoch A.,, et al. The InterPro database, an integrated documentation resource for protein families, domains and functional sites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:37–41. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bateman A., Coin L., Durbin R.,, et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:138–141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Florea L., Hartzell G., Zhang Z., Rubin G. M., Webb M. A computer program for aligning a cDNA sequence with a genomic DNA sequence. Genome Res. 1998;8:967–974. doi: 10.1101/gr.8.9.967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rice P., Longden I., Bleasby A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends Genet. 2000;16:276–277. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(00)02024-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Plewniak F., Jeanmougin F., Higgins D. G. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;24:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Suyama M., Torrents D., Bork P. PAL2NAL: robust conversion of protein sequence alignments into the corresponding codon alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:W609–W612. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths-Jones S., Moxon S., Marshall M., Khanna A., Eddy S. R., Bateman A. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D121–D124. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Griffiths-Jones S., Saini H. K., van Dongen S., Enright A. J. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D154–D158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsuritani K., Irie T., Yamashita R.,, et al. Distinct class of putative “non-conserved” promoters in humans: comparative studies of alternative promoters of human and mouse genes. Genome Res. 2005;17:1005–1014. doi: 10.1101/gr.6030107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carninci P., Sandelin A., Lenhard B.,, et al. Genome-wide analysis of mammalian promoter architecture and evolution. Nat Genet. 2006;38:626–635. doi: 10.1038/ng1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Monna L., Ohta R., Masuda H., Koike A., Minobe Y. Genome-wide searching of single-nucleotide polymorphisms among eight distantly and closely related rice cultivars (Oryza sativa L.) and a wild accession (Oryza rufipogon Griff.) DNA Res. 2006;13:43–51. doi: 10.1093/dnares/dsi030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng C., Motohashi R., Tsuchimoto S., Fukuta Y., Ohtsubo H., Ohtsubo E. Polyphyletic origin of cultivated rice: based on the interspersion pattern of SINEs. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2003;20:67–75. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reimmann C., Dudler R. Circadian rhythmicity in the expression of a novel light-regulated rice gene. Plant Mol. Biol. 1993;22:165–170. doi: 10.1007/BF00039006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tumer N. E., Clark W. G., Tabor G. J., Hironaka C. M., Fraley R. T., Shah D. M. The genes encoding the small subunit of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase are expressed differentially in petunia leaves. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986;14:3325–3342. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.8.3325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Close T. J., Kortt A. A., Chandler P. M. A cDNA-based comparison of dehydration-induced proteins (dehydrins) in barley and corn. Plant Mol. Biol. 1989;13:95–108. doi: 10.1007/BF00027338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gao L. Z., Hong D. Y., Ge S. Allozyme variation and population genetic structure of common wild rice Oryza rufipogon Griff. in China. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2000;101:494–502. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang Z. S., Zhu L. H., Liu Z. Y., Wang X. K. Genetic diversity of natural wild rice populations detected by RFLP markers (in Chinese) Agric Biotechnol. 1996;4:111–117. [Google Scholar]