Abstract

The hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) regulates the posttranslational modification of nuclear and cytoplasmic protein by O-linked N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc). Numerous studies have demonstrated that, in hyperglycemic conditions, excessive glucose flux through this pathway contributes to the development of insulin resistance. The role of the HBP in euglycemia, however, remains largely unknown. Here we investigated the effect of O-GlcNAc on hepatic Akt signaling at physiological concentrations of glucose. In HepG2 cells cultured in 5 mM glucose, removal of O-GlcNAc by adenoviral-mediated overexpression of O-GlcNAcase increased Akt activity and phosphorylation. We also observed that Akt was recognized by succinylated wheat germ agglutinin (sWGA), which specifically binds O-GlcNAc. Overexpression of O-GlcNAcase in HepG2 cells reduced the levels of Akt in sWGA precipitates. The increased Akt activity was accompanied by increased phosphorylation of Akt substrates and reduced mRNA for glucose-6-phosphatase and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK). The increased Akt activity was not a result of activation of its upstream activator phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase). Further demonstrating Akt regulation by O-GlcNAc, we found that overexpression of O-GlcNAcase in the livers of euglycemic mice also significantly increased Akt activity, resulting in increased phosphorylation of downstream targets and decreased mRNA for glucose-6-phosphatase. Together, these data suggest that O-GlcNAc regulates Akt signaling in hepatic models under euglycemic conditions.

Keywords: hexosamine, hepatic, gluconeogenic enzymes

insulin resistance is a central feature of type 2 diabetes wherein there is a defect in the ability of insulin to stimulate glucose uptake in muscle and fat and to suppress hepatic glucose production. Insulin resistance may result from a combination of hereditary factors, chronic hyperinsulinemia, and so-called “glucose toxicity,” which refers to effects of chronically excessive glucose flux on cellular function and regulation (29, 36). One major mediator of the regulatory effects of glucose is the hexosamine biosynthesis pathway (HBP) (4, 18, 28). A relatively small fraction of cellular fructose 6-phosphate enters the HBP and is converted to glucosamine 6-phosphate by the rate-limiting enzyme glutamine:fructose-6-phosphate amidotransferase (GFA). Glucosamine 6-phosphate is converted to uridine 5′-diphospho N-acetylglucosamine, which can be used as a substrate by the enzyme O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine transferase (OGT) to catalyze covalent attachment of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) to serine and threonine residues of nuclear and cytosolic proteins. The O-GlcNAc modification is removed by the enzyme O-linked β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (O-GlcNAcase). Sites of O-GlcNAc modification have been identified for numerous proteins and are often the same as or near phosphorylation sites, suggesting a regulatory function of O-GlcNAc modification. In fact, O-GlcNAc modification is known to modulate transcription, translation, nuclear transport, and other critical cellular processes (12, 38).

The involvement of the HBP in the development of glucose-induced insulin resistance was first suggested by Marshall et al. (18), who demonstrated a requirement for the HBP in desensitizing insulin-stimulated glucose transport in cultured adipocytes. Subsequent studies have confirmed the importance of the HBP in mediating insulin resistance. For example, transgenic mice overexpressing OGT in muscle and fat have elevated insulin levels and diminished glucose disposal rates (22), GFA transgene expression in mouse adipose tissue also results in defective insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (21), and adenoviral overexpression of OGT in mouse liver results in higher glucose and insulin levels, with a concomitant increase in hepatic glucose production (37). Conversely, it has been demonstrated recently that adenoviral expression of O-GlcNAcase in the livers of db/db mice improves glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity (7). All of the data strongly support the importance of O-GlcNAc modification in regulating insulin signaling in pathological situations of hyperglycemia and nutrient excess. The question remains whether O-GlcNAc modifications also play a role in metabolic regulation in states wherein glucose concentrations are normal. Therefore, we sought to characterize the significance of O-GlcNAc modifications under euglycemic condition. Particularly, we overexpressed O-GlcNAcase in HepG2 cells cultured in normal glucose and the livers of euglycemic C57BL/6J mice and investigated the effect of removal of protein O-GlcNAc modifications on Akt signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies.

Antibodies to Akt, phospho-Akt (Ser473), phospho-forkhead box O1 (FOXO1; Ser256), phospho-GSK-3β (Ser9), and phospho-murine double minute-2 (MDM2; Ser166) were from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-O-GlcNAc monoclonal IgM antibody [carboxy terminal domain (CTD) 110.6] was a gift from Dr. Gerald Hart. GAPDH antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Insulin receptor substrate (IRS)-1 antibody was purchased from Upstate (Lake Placid, NY).

Virus purification and titer.

Human embryonic kidney-293 cells were infected with adenovirus for 48 h. Infected cells were harvested and then frozen/thawed for three cycles to release the adenovirus. Cell debris was then pelleted by spinning at 3,000 rpm for 10 min. Virus was purified and titered using kits from Cell Biolabs (San Diego, CA). The purified virus was used for study in the HepG2 cells only.

Overexpression of proteins in HepG2 cells.

The HepG2 cell line was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). HepG2 cells were maintained in 5 mM glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin, at 37°C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. HepG2 cells were seeded on 6-cm plates and cultured to 70% confluence. Cells were then infected with 5 × 107 plaque-forming units of adenovirus encoding either green fluorescent protein (GFP) or O-GlcNAcase (a generous gift from Dr. Wolfgang Dillmann, University of California, San Diego, CA). On the following day, medium was replaced with fresh medium containing 1% FBS. Cells were harvested 48 h after infection.

Overexpression of proteins in C57BL/6J mouse livers.

Eight- to ten-week-old mice were injected through the tail vein with a suspension of 200 μl of 1 × 1011 virus particles of GFP or O-GlcNAcase adenovirus. We infected the mice for 3, 5, 7, or 9 days and determined that O-GlcNAcase mRNA level is highest after 3 days of infection. Mice were killed, and harvested organs were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen. The GFP and O-GlcNAcase virus were amplified, purified, and titered by Vector Biolabs (Philadelphia, PA).

Western blot.

HepG2 cells were collected and briefly sonicated in lysis buffer [50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO)]. Frozen livers from C57BL/6J mice were homogenized in lysis buffer using a Dounce homogenizer. Twenty to sixty micrograms of denatured protein was resolved on a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and transferred onto immobilon nitrocellulose membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA). Blots were then blocked with TBS-T (20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mM sodium chloride, and 0.5% Tween 20) containing 5% (wt/vol) nonfat dried milk for 1 h at room temperature. For detection with the CTD 110.6 antibody, blots were blocked with TBS-T containing 5% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin. Blots were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4°C and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 1 h at room temperature.

Succinylated wheat germ agglutinin.

The assay was carried out as described previously (27). Briefly, 400 μg of protein was incubated with 30 μl of succinylated wheat germ agglutinin (sWGA; Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) beads overnight at 4°C. Beads were collected by centrifugation (14,000 rpm, 4°C, 1 min) and washed three times with lysis buffer. Beads were collected again with centrifugation and resuspended in 30 μl of Laemmli sample buffer, boiled, and loaded onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel.

Akt kinase assay.

Five hundred micrograms of protein was incubated overnight at 4°C with immobilized Akt antibody cross-linked to agarose beads (Cell Signaling). GSK-3 fusion protein was later added per the manufacturer's protocol. The reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS sample buffer. Samples were boiled, loaded onto a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel, and immunoblotted with phospho-GSK-3β antibody.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase assay.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI 3-kinase) was immunoprecipitated by incubating 200 μg of protein with IRS-1 antibody for 3 h, followed by incubation with protein A agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 h. All incubations were performed at 4°C. Beads were washed twice with each of the following three buffers [buffer 1: PBS, 1% Igepal, 100 μM Na3VO4; buffer 2: 100 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 500 mM LiCl, 100 μM Na3VO4; buffer 3: 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, 100 μM Na3VO4] and then resuspended in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 100 mM NaCl, and 1 mM EDTA. Prior to phosphatidylinositol (Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) being added to the resuspended beads, the lipid was dried under a stream of nitrogen gas, resuspended in buffer [10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 1 mM EGTA], and then sonicated for 2 min. The reaction was started by adding 5 μCi of [32P]ATP and incubating for 10 min at room temperature. The reaction was stopped with 8 M HCl, and phospholipids were extracted with CHCl3-MeOH (1:1). The phospholipids were resolved by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and visualized by autoradiography. Samples were then scraped from the TLC plate and counted for 32P incorporation using a liquid scintillation counter.

RT-PCR.

HepG2 cells were infected with adenovirus as described above. Forty-eight hours after infection, RNA was isolated from HepG2 cells using TRI reagent (Molecular Research Center, Cincinnati, OH), purified using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), and reverse transcribed into cDNA. cDNA was purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen) prior to RT-PCR studies. mRNA levels from HepG2 cells were normalized to non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein (16, 33), 5′-CAAGTGGACCGCAACATCA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CGCCGCATCTCTTCTTCAC-3′ (reverse). Other primers used for HepG2 studies were as follows: human phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK), 5′-GAGCTGACGGATTCACCCTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCACTGCCAAAGGAGATGAT-3′ (reverse); human glucose-6-phosphatase, 5′-TACGTCCTCTTCCCCATCTG-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCTGGTCCAGTCTCACAGGT-3′ (reverse). For animal studies, mice were killed 3 days postinjection and liver slices stored in RNAlater. Tissues were weighed and homogenized with a Tissue Tearor in buffer RLT (Qiagen). RNA was purified and reverse transcribed as mentioned above. mRNA levels from C57BL/6J mice were normalized to ribosomal protein L13a (Rpl13a), 5′-GGAGAAACGGAAGGAAAAGG-3′ (forward) and 5′-ACAGGAGCAGTGCCTAAGGA-3′ (reverse). Other primers used for C57BL/6J studies were as follows: mouse and human O-GlcNAcase, 5′-CCCTCAGCCTGGATTACTGCT-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGACAGGAGGCAAGCCATCA-3′ (reverse); mouse PEPCK, 5′-GTCAACACCGACCTCCCTTA-3′ (forward) and 5′-CCCTAGCCTGTTCTCTGTGC-3′ (reverse); mouse glucose-6-phosphatase, 5′-AGGAAGGATGGAGGAAGGAA-3′ (forward) and 5′-TGGAACCAGATGGGAAAGAG-3′ (reverse).

Statistical analysis.

Results are presented as means ± SE. The unpaired Student's t-test (2-tailed) was used to assess differences between experimental groups and controls. Probability values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

O-GlcNAcase overexpression increased Akt activity in HepG2 cells.

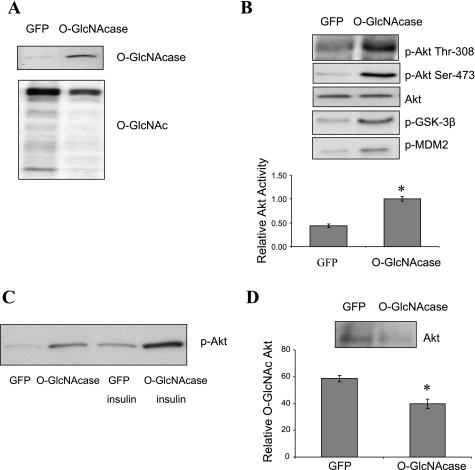

Studies involving O-GlcNAc modification have shown that increased protein O-glycosylation can lead to the development of insulin resistance, and one mechanism is through reduction of Akt activity (26, 35). To determine whether reduced O-GlcNAc modification would also affect insulin signaling in normal glucose concentrations, we used adenovirus to overexpress O-GlcNAcase in HepG2 cells cultured in medium containing 5 mM glucose. Adenoviral-mediated overexpression of O-GlcNAcase in HepG2 cells increased O-GlcNAcase protein levels, resulting in a decrease in global O-GlcNAc modification of proteins as detected by O-GlcNAc-specific CTD 110.6 antibody (Fig. 1A). We then examined the effect of O-GlcNAcase overexpression on Akt signaling and observed an increase in Akt phosphorylation at Thr308 and Ser473 (Fig. 1B) with a concomitant 2.3-fold increase in Akt activity (P < 0.05; Fig. 1B), measured in vitro from extracts of HepG2 cells. The increased activity of Akt was reflected in increased phosphorylation of the Akt substrates GSK-3β (at Ser9) and MDM2 (at Ser166) (Fig. 1B) (19). We next examined the effect of insulin on Akt phosphorylation and found that insulin further induced Akt phosphorylation in O-GlcNAcase overexpressing cells compared with control cells (Fig. 1C). Previous reports have demonstrated O-GlcNAc modification of Akt in cells cultured under hyperglycemic conditions (17, 26). To test whether Akt is also O-GlcNAc modified under normal glucose conditions, we used sWGA, a modified lectin that binds O-GlcNAc, to precipitate the O-GlcNAc-modified proteins from HepG2 cell lysates. Akt was detected in sWGA precipitates, and overexpression of O-GlcNAcase decreased Akt levels in sWGA precipitates by 32% (P < 0.05; Fig. 1D). These results indicate that removal of O-GlcNAc modifications increases Akt activity in HepG2 cells grown in normal (5 mM) glucose.

Fig. 1.

Effect of O-linked β-N-acetylglucosaminidase (O-GlcNAcase) overexpression on Akt activity in HepG2 cells. A: HepG2 cells were infected with adenovirus encoding either green fluorescent protein (GFP) or O-GlcNAcase for 2 days. Cell extracts were immunoblotted with O-GlcNAcase and CTD 110.6 antibodies. B: cell extracts were also immunoblotted with phospho (p)-Akt (Thr308 or Ser473), total Akt, p-GSK-3β (Ser9), and phospho-murine double minute-2 (p-MDM2; Ser166) antibodies. To correlate Akt phosphorylation with its activity, Akt activity was assessed in cell lysates immunoprecipitated with Akt antibody, incubated with GSK-3 fusion protein substrate, and immunoblotted with phospho-GSK-3-specific antibody. C: to determine the effect of insulin on Akt signaling, infected HepG2 cells were treated with or without 10 nM insulin for 30 min prior to harvesting. D: To determine whether Akt was O-linked β-N-acetylglucosamine (O-GlcNAc) modified, HepG2 cell lysates were precipitated with succinylated wheat germ agglutin agarose followed by immunoblotting with Akt antibody. The result shown represents the mean ± SE of at least 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

O-GlcNAcase-mediated Akt activation in HepG2 cells was not a result of upstream activation of PI 3-kinase.

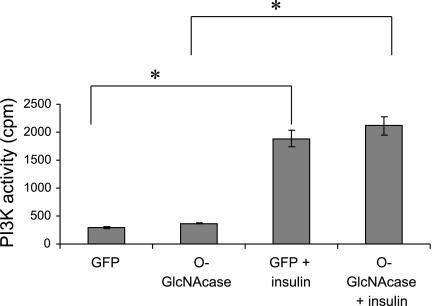

After insulin stimulation, IRSs interact with the p85 subunit of PI 3-kinase, leading to activation of the p110 subunit of PI 3-kinase. This in turn phosphorylates phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. Phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate then stimulates the translocation of Akt to the plasma membrane, where Akt can be phosphorylated by phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 and the mTOR-rictor complex (1, 30, 32). To determine whether increased Akt activity with O-GlcNAcase overexpression was due to increased PI 3-kinase activity, we measured PI 3-kinase activity in HepG2 cells and found that there was no significant difference in PI 3-kinase activity between O-GlcNAcase-overexpressing cells and control cells. Insulin treatment increased PI 3-kinase activity equally (∼6-fold) in control and O-GlcNAcase-overexpressing cells (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) activity in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were infected with adenovirus encoding either GFP or O-GlcNAcase for 2 days. The cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with IRS-1 antibody, and immunocomplexes were then incubated with phosphatidylinositol along with [32P]ATP in assay buffer. Samples were assayed for 32P incorporation into phosphatidylinositol using a liquid scintillation counter. The result shown represents the mean ± SE of 3 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

O-GlcNAcase overexpression reduced glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK mRNA transcript levels in HepG2 cells.

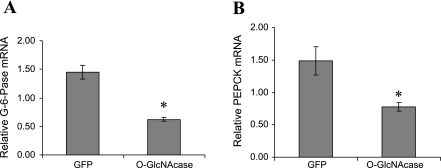

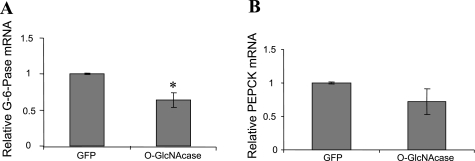

After insulin stimulation, phosphorylated Akt enters the nucleus, where it can phosphorylate FOXO1. Phosphorylation by Akt disrupts the ability of FOXO1 to bind DNA (40) and thereby prevents upregulation of transcription of the gluconeogenic genes glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK (11, 23, 31), resulting in decreased hepatic glucose production (25). To confirm that activation of Akt by O-GlcNAcase in HepG2 cells also resulted in transcriptional regulation of glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK, we examined their mRNA transcript levels by RT-PCR. Although we were unable to conclusively demonstrate changes in FOXO1 phosphorylation by Akt in HepG2 cells overexpressing O-GlcNAcase (data not shown), we did observe a 57 (P < 0.05) and 48% (P < 0.05) decrease in glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK transcript levels, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Effect of O-GlcNAcase overexpression on gluconeogenic enzymes in HepG2 cells. HepG2 cells were infected with adenovirus encoding either GFP or O-GlcNAcase for 2 days. Glucose-6-phosphatase (G-6-Pase; A) and phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK; B) mRNA transcript levels were measured as described in materials and methods. Both were normalized to mRNA levels of non-POU domain-containing octamer-binding protein message. The results shown represent the mean ± SE of 7 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

O-GlcNAcase overexpression increased Akt activity in livers of C57BL/6J mice.

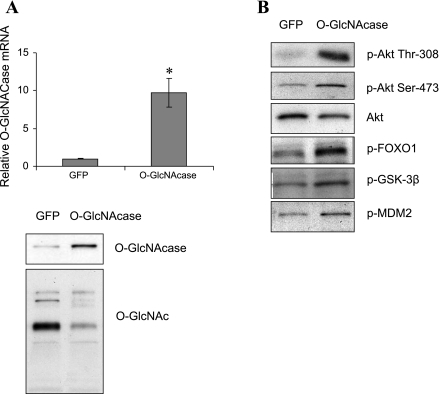

To determine whether results observed in the HepG2 cells were physiologically relevant in the intact animal, livers of C57BL/6J mice were infected by tail vein injection with adenovirus expressing either GFP or O-GlcNAcase. These mice exhibited normal fasting blood glucose levels (GFP, 133 mg/dl vs. O-GlcNAcase, 140 mg/dl, n = 3–4, P = 0.32; Supplemental Fig. S1A; Supplemental Material for this article is available at the AJP-Endocrinology and Metabolism web site). O-GlcNAcase mRNA levels in the livers of O-GlcNAcase-infected mice increased 9.7-fold (P < 0.05) compared with GFP controls (Fig. 4A). No changes in O-GlcNAcase mRNA level were observed in either muscle or fat (data not shown). O-GlcNAcase overexpression resulted in decreased global protein O-GlcNAc modification in liver (Fig. 4A). Consistent with results from HepG2 cells, O-GlcNAcase overexpression in liver led to increased hepatic Akt phosphorylation on Thr308 and Ser473 (Fig. 4B), which was accompanied by increased phosphorylation of Akt substrates GSK-3β (Ser9), MDM2 (Ser166), and FOXO1 (Ser256) (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, we observed a 36% (P < 0.05) reduction in glucose-6-phosphatase mRNA compared with control mice. PEPCK mRNA decreased by 24%; however, the result was not statistically significant (Fig. 5). Together, these results indicate that removal of the O-GlcNAc modification also increases Akt signaling in livers of euglycemic mice.

Fig. 4.

Effect of O-GlcNAcase overexpression on Akt activity in livers of C57BL/6J mice. O-GlcNAcase protein was overexpressed in the liver of C57BL/6J mice through tail vein injection of adenovirus encoding the protein. Adenovirus encoding GFP was used as control. A: mRNA and protein level of O-GlcNAcase were determined by RT-PCR and Western blotting. The RT-PCR result represents the mean ± SE of 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05. B: liver extracts were immunoblotted with specific antibodies as indicated. FOXO1, forkhead box O1.

Fig. 5.

Effect of O-GlcNAcase overexpression on gluconeogenic enzymes in livers of C57BL/6J mice. O-GlcNAcase protein was overexpressed in the liver of C57BL/6J mice through tail vein injection of adenovirus encoding the protein. Adenovirus encoding GFP was used as control. G-6-Pase (A) and PEPCK (B) mRNA level were measured as described in materials and methods. Both were normalized to ribosomal protein L13a message. The results shown represent the mean ± SE of 5 independent experiments. *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

Sustained hyperglycemia has been shown to induce insulin resistance, and this has been suggested to be an adaptive mechanism in protecting cells from oxidative stress that results from excess nutrients (4). The HBP has been shown to be one of the cellular nutrient sensors that plays an important role in the development of insulin resistance (3, 20, 28).

The protein kinase Akt is an important mediator of insulin signaling in the regulation of cell survival and metabolism (5, 9, 39). Akt has previously been shown to be O-GlcNAc modified by OGT (10, 26), and several studies have demonstrated linkage between the HBP, the development of insulin resistance, and altered Akt signaling. For example, treatment of 3T3-L1 adipocytes with O-(2-acetamido-2-deoxy-d-glucopyranosylidene)-amino-N-phenylcarbamate (PUGNAc; an inhibitor of O-GlcNAcase) reduces Akt phosphorylation, resulting in a reduction of insulin-stimulated 2-deoxyglucose uptake (35). In primary adipocytes isolated from rat epididymal fat pads, PUGNAc treatment results in increased Akt O-GlcNAc modification with a concomitant decrease in Akt phosphorylation, resulting in impaired insulin-stimulated glucose transporter 4 translocation to the plasma membrane (26). O-GlcNAcase overexpression in db/db mice increases Akt phosphorylation and improves glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity (7). In a recent report, Yang et al. (37) demonstrated that upon insulin stimulation OGT can be translocated to the plasma membrane through interaction with phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate, demonstrating a potential mechanism by which Akt can be O-GlcNAcylated. Most studies, including those above, have linked hyperglycemia and/or chronically high glucose flux through the hexosamine pathway with the development of insulin resistance (6, 13, 21, 24, 26, 27, 35). The role of the HBP in euglycemia, however, remains largely unknown. In this study, we have examined the role of O-GlcNAc regulation in HepG2 cells that were cultured in 5 mM glucose and livers of euglycemic C57BL/6J mice fed with normal chow. We showed that overexpression of O-GlcNAcase in the two models reduced O-GlcNAc modification of proteins. We observed a decrease in O-GlcNAc modification of Akt in HepG2 cells and an increase in Akt phosphorylation in both tissue culture and in vivo experiments. These data are consistent with the reciprocal relationship that has been established between phosphorylation and O-GlcNAc modification in many other proteins (8, 27). The results are congruent with previous findings where the opposite approach was used, where PUGNAc treatment of primary rat adipocytes increased O-GlcNAc modification of Akt while reducing its phosphorylation level (26).

The increased Akt phosphorylation resulted in increased phosphorylation of its downstream targets, including FOXO1. Previous studies have shown that increased phosphorylation of FOXO1 protein by Akt causes FOXO1 to be exported to the cytoplasm, through interaction with the 14-3-3 protein, where it is targeted for proteosomal degradation (34). Removal of FOXO1 from the nucleus prevents it from upregulating the transcription of gluconeogenic enzymes, including glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK (11, 23, 31). Consistent with these observations, we found that overexpression of O-GlcNAcase increased Akt-FOXO1 signaling that significantly reduced mRNA expression of glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK in HepG2 cells, although only glucose-6-phosphatase mRNA was significantly reduced in the animal study. Of note, increased FOXO1 phosphorylation was observed in the animal model only. This may be due to technical limitations; however, O-GlcNAc modification of FOXO1 may also be an independent signal in stimulating transcription of gluconeogenic enzymes in HepG2 cells (15). A separate mechanism by which O-GlcNAc modification could affect gluconeogenesis is through cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein 2 (CRTC2 or TORC2). CRTC2 is a critical switch that regulates hepatic gluconeogenesis in part by upregulating glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK gene expression under condition of starvation (14). It has been shown that CRTC2 is O-GlcNAc modified, and this modification prevents phosphorylation of CRTC2, thereby allowing CRTC2 to be retained in the nucleus, where it plays a role in upregulating expression of gluconeogenic enzymes. Although the reverse is true, removing O-GlcNAc modification from CRTC2 increases phosphorylation of CRTC2 and results in downregulation of glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK mRNA transcript (7). These data show diverse mechanisms in regulating the hepatic glucose production while highlighting the importance of O-GlcNAc modification for its role in modulating proteins that are involved in hepatic gluconeogenesis.

A previous study has shown that HBP flux can impair insulin-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of IRS-1, PI 3-kinase activity, and subsequent Akt activation in rat insulinoma β-cells (2), demonstrating that impaired upstream signaling may lead to impaired Akt activation. In this study, we observed an increase in Akt signaling through overexpression of O-GlcNAcase; however, contrary to the above study, we did not observe an increase in PI 3-kinase activity associated with decreased O-glycosylation. A similar lack of an effect of O-GlcNAc on signaling upstream of Akt has been observed in adipocytes treated with PUGNAc (35) or in observations made by Yang et al. (37) that suggest that O-GlcNAc does not affect PI 3-kinase activity. These data suggest that HBP-induced changes in Akt activity do not necessarily require changes in insulin signaling upstream from Akt, although upstream effects may be noted in certain cell or tissue types or with hyperglycemia.

We performed physiological assays 3 days postinfection, when O-GlcNAcase mRNA levels were maximal, and observed increased Akt signaling in livers of C57BL/6J mice, although we were not able to detect any changes in fasting glucose and insulin levels, glucose tolerance, or glycogen content (Supplemental Figs. S1–S3). Another study of wild-type C57BL/6J mice overexpressing O-GlcNAcase also failed to demonstrate a significant difference in glucose tolerance compared with controls (7). The lack of an effect of O-GlcNAcase on overall glucose homeostasis may be due to compensatory effects in the liver or other tissues, and the functional significance of increased Akt signaling through decreased O-GlcNAc modification in euglycemia therefore requires further examination. We did note, however, a small but significant decrease in fasting blood glucose after 5 days of infection, consistent with the lower mRNA level of the gluconeogenic enzymes (Supplemental Fig. S4).

We also evaluated whether O-GlcNAcase overexpression in liver is sufficient to alter Akt signaling in ob/ob diabetic mice. We found that there was no change in Akt phosphorylation between GFP control and O-GlcNAcase-overexpressing mice, and in addition we also showed no statistically significant difference in their glucose tolerance (data not shown). This is in contrast to published results obtained using db/db mice and suggests that differences in mouse model or strain, levels of viral expression, kinetics of expression, and/or other unknown variables are also affecting the ultimate physiological phenotype that is observed (7).

In summary, we have demonstrated that decreasing the O-GlcNAc modification of proteins under euglycemic conditions increases Akt signaling, resulting in reduced mRNA levels of glucose-6-phosphatase and PEPCK in HepG2 cells and reduced glucose-6-phosphatase mRNA in the liver of intact nondiabetic mice. This adds to the growing body of evidence showing the importance of HBP as a nutrient-sensing pathway not only in pathological states of excess nutrient levels but also in normal physiology.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Research Service of the Veterans Administration and the National Institutes of Health (RO1-DK-43526 and 5-T32-DK-007115).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. William Holland and Scott Summers for generous assistance with the PI 3-kinase assay. We also thank Dr. Wolfgang Dillmann for the O-GlcNAcase adenovirus.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alessi DR, James SR, Downes CP, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, Cohen P. Characterization of a 3-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase which phosphorylates and activates protein kinase Balpha. Curr Biol 7: 261–269, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreozzi F, D'Alessandris C, Federici M, Laratta E, Del Guerra S, Del Prato S, Marchetti P, Lauro R, Perticone F, Sesti G. Activation of the hexosamine pathway leads to phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate-1 on Ser307 and Ser612 and impairs the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt/mammalian target of rapamycin insulin biosynthetic pathway in RIN pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology 145: 2845–2857, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brownlee M Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414: 813–820, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buse MG Hexosamines, insulin resistance, and the complications of diabetes: current status. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E1–E8, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chang L, Chiang SH, Saltiel AR. Insulin signaling and the regulation of glucose transport. Mol Med 10: 65–71, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooksey RC, Pusuluri S, Hazel M, McClain DA. Hexosamines regulate sensitivity of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in β-cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 290: E334–E340, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dentin R, Hedrick S, Xie J, Yates J 3rd, Montminy M. Hepatic glucose sensing via the CREB coactivator CRTC2. Science 319: 1402–1405, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du XL, Edelstein D, Rossetti L, Fantus IG, Goldberg H, Ziyadeh F, Wu J, Brownlee M. Hyperglycemia-induced mitochondrial superoxide overproduction activates the hexosamine pathway and induces plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 expression by increasing Sp1 glycosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12222–12226, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farese RV, Sajan MP, Standaert ML. Insulin-sensitive protein kinases (atypical protein kinase C and protein kinase B/Akt): actions and defects in obesity and type II diabetes. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 230: 593–605, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gandy JC, Rountree AE, Bijur GN. Akt1 is dynamically modified with O-GlcNAc following treatments with PUGNAc and insulin-like growth factor-1. FEBS Lett 580: 3051–3058, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall RK, Yamasaki T, Kucera T, Waltner-Law M, O'Brien R, Granner DK. Regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 gene expression by insulin. The role of winged helix/forkhead proteins. J Biol Chem 275: 30169–30175, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart GW, Housley MP, Slawson C. Cycling of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine on nucleocytoplasmic proteins. Nature 446: 1017–1022, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hazel M, Cooksey RC, Jones D, Parker G, Neidigh JL, Witherbee B, Gulve EA, McClain DA. Activation of the hexosamine signaling pathway in adipose tissue results in decreased serum adiponectin and skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Endocrinology 145: 2118–2128, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koo SH, Flechner L, Qi L, Zhang X, Screaton RA, Jeffries S, Hedrick S, Xu W, Boussouar F, Brindle P, Takemori H, Montminy M. The CREB coactivator TORC2 is a key regulator of fasting glucose metabolism. Nature 437: 1109–1111, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuo M, Zilberfarb V, Gangneux N, Christeff N, Issad T. O-glycosylation of FoxO1 increases its transcriptional activity towards the glucose 6-phosphatase gene. FEBS Lett 582: 829–834, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee PD, Sladek R, Greenwood CM, Hudson TJ. Control genes and variability: absence of ubiquitous reference transcripts in diverse mammalian expression studies. Genome Res 12: 292–297, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo B, Soesanto Y, McClain DA. Protein modification by O-linked GlcNAc reduces angiogenesis by inhibiting Akt activity in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 28: 651–657, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall S, Bacote V, Traxinger RR. Discovery of a metabolic pathway mediating glucose-induced desensitization of the glucose transport system. Role of hexosamine biosynthesis in the induction of insulin resistance. J Biol Chem 266: 4706–4712, 1991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mayo LD, Donner DB. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway promotes translocation of Mdm2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 11598–11603, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McClain DA Hexosamines as mediators of nutrient sensing and regulation in diabetes. J Diabetes Complications 16: 72–80, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClain DA, Hazel M, Parker G, Cooksey RC. Adipocytes with increased hexosamine flux exhibit insulin resistance, increased glucose uptake, and increased synthesis and storage of lipid. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 288: E973–E979, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McClain DA, Lubas WA, Cooksey RC, Hazel M, Parker GJ, Love DC, Hanover JA. Altered glycan-dependent signaling induces insulin resistance and hyperleptinemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 10695–10699, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nakae J, Kitamura T, Silver DL, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 (Fkhr) confers insulin sensitivity onto glucose-6-phosphatase expression. J Clin Invest 108: 1359–1367, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson BA, Robinson KA, Buse MG. High glucose and glucosamine induce insulin resistance via different mechanisms in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes 49: 981–991, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nordlie RC, Foster JD, Lange AJ. Regulation of glucose production by the liver. Annu Rev Nutr 19: 379–406, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Park SY, Ryu J, Lee W. O-GlcNAc modification on IRS-1 and Akt2 by PUGNAc inhibits their phosphorylation and induces insulin resistance in rat primary adipocytes. Exp Mol Med 37: 220–229, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Parker GJ, Lund KC, Taylor RP, McClain DA. Insulin resistance of glycogen synthase mediated by o-linked N-acetylglucosamine. J Biol Chem 278: 10022–10027, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rossetti L Perspective: Hexosamines and nutrient sensing. Endocrinology 141: 1922–1925, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rossetti L, Giaccari A, DeFronzo RA. Glucose toxicity. Diabetes Care 13: 610–630, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Phosphorylation and regulation of Akt/PKB by the rictor-mTOR complex. Science 307: 1098–1101, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmoll D, Walker KS, Alessi DR, Grempler R, Burchell A, Guo S, Walther R, Unterman TG. Regulation of glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression by protein kinase Balpha and the forkhead transcription factor FKHR. Evidence for insulin response unit-dependent and -independent effects of insulin on promoter activity. J Biol Chem 275: 36324–36333, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephens L, Anderson K, Stokoe D, Erdjument-Bromage H, Painter GF, Holmes AB, Gaffney PR, Reese CB, McCormick F, Tempst P, Coadwell J, Hawkins PT. Protein kinase B kinases that mediate phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate-dependent activation of protein kinase B. Science 279: 710–714, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor RP, Parker GJ, Hazel MW, Soesanto Y, Fuller W, Yazzie MJ, McClain DA. Glucose deprivation stimulates O-GlcNAc modification of proteins through up-regulation of O-linked N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase. J Biol Chem 283: 6050–6057, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.van der Heide LP, Smidt MP. Regulation of FoxO activity by CBP/p300-mediated acetylation. Trends Biochem Sci 30: 81–86, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vosseller K, Wells L, Lane MD, Hart GW. Elevated nucleocytoplasmic glycosylation by O-GlcNAc results in insulin resistance associated with defects in Akt activation in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 5313–5318, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warram JH, Martin BC, Krolewski AS, Soeldner JS, Kahn CR. Slow glucose removal rate and hyperinsulinemia precede the development of type II diabetes in the offspring of diabetic parents. Ann Intern Med 113: 909–915, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yang X, Ongusaha PP, Miles PD, Havstad JC, Zhang F, So WV, Kudlow JE, Michell RH, Olefsky JM, Field SJ, Evans RM. Phosphoinositide signalling links O-GlcNAc transferase to insulin resistance. Nature 451: 964–969, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zachara NE, Hart GW. Cell signaling, the essential role of O-GlcNAc! Biochim Biophys Acta 1761: 599–617, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zdychova J, Komers R. Emerging role of Akt kinase/protein kinase B signaling in pathophysiology of diabetes and its complications. Physiol Res 54: 1–16, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang X, Gan L, Pan H, Guo S, He X, Olson ST, Mesecar A, Adam S, Unterman TG. Phosphorylation of serine 256 suppresses transactivation by FKHR (FOXO1) by multiple mechanisms. Direct and indirect effects on nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling and DNA binding. J Biol Chem 277: 45276–45284, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.