Abstract

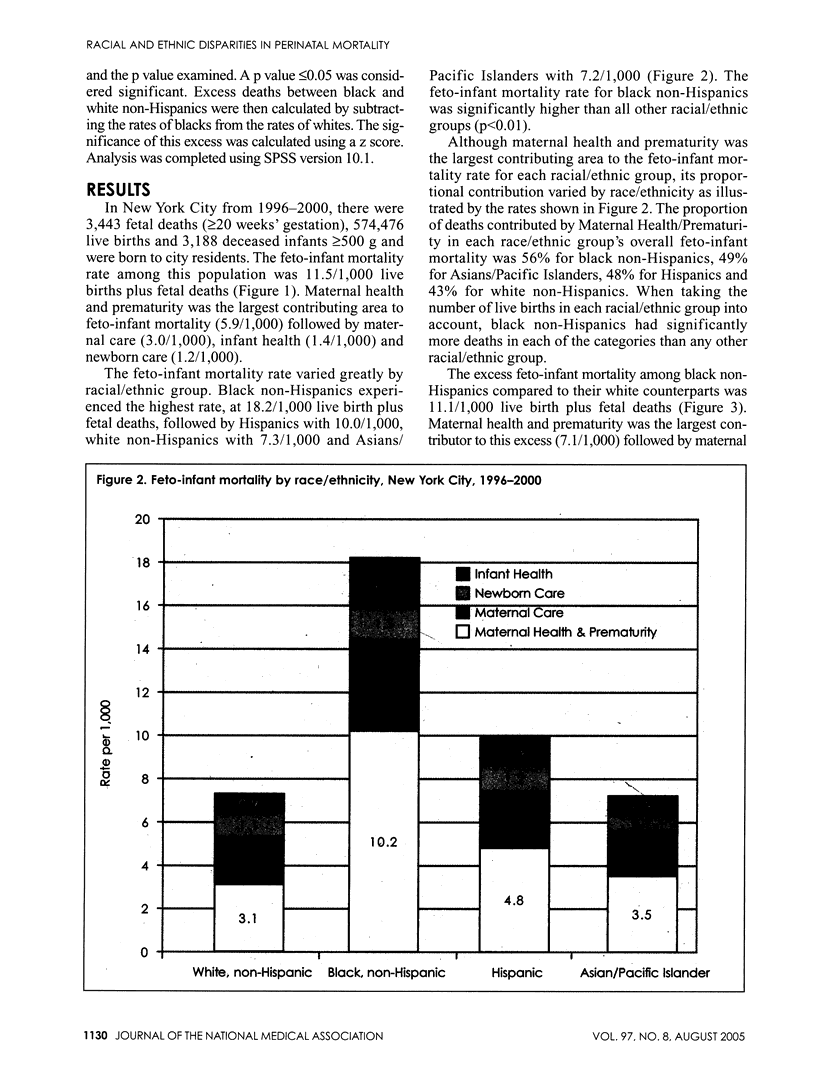

OBJECTIVES: To determine the feto-infant mortality rate for New York City, assess racial/ethnic variations and identify areas for intervention using the Perinatal Periods of Risk (PPOR) approach. METHODS: The PPOR model examines fetal and infant deaths by age at death (fetal, neonatal, postneonatal) and birthweight (500-1499, > or =1500 g). It groups age at death and birthweight into four categories to identify problems hypothesized to lead to the death: factors related to Maternal Health and Prematurity, Maternal Care, Newborn Care and Infant Health. The model was applied to fetal and infant deaths occurring in New York City using Vital Records data from 1996-2000. Analysis was completed for the entire city and by race/ethnicity (white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, Asians/Pacific Islander). RESULTS: The overall feto-infant mortality rate was 11.5/1,000 live births plus fetal deaths. This rate varied by race/ethnicity; black non-Hispanics had a higher rate than other racial/ethnic groups. Conditions related to maternal health and prematurity were the largest contributing factors to feto-infant mortality (5.9/1000) in New York City. Among blacks and Hispanics, problems related to maternal health and prematurity contributed a larger share than among whites and Asians/Pacific Islanders. CONCLUSION: The use of the PPOR approach shows that the racial/ethnic disparities in feto-infant mortality that exist in New York City are largely related to maternal health and prematurity. Interventions to reduce the feto-infant mortality rate should include preconception care and improvements in women's health.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson Robert N. Deaths: leading causes for 2000. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2002 Sep 16;50(16):1–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A. D. Perinatal substance abuse and the drug-exposed neonate. Adv Nurse Pract. 1999 May;7(5):32–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Besculides Melanie, Laraque Fabienne. Unintended pregnancy among the urban poor. J Urban Health. 2004 Sep;81(3):340–348. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair P., Fleming P. Epidemiological investigation of sudden infant death syndrome infants--recommendations for future studies. Child Care Health Dev. 2002 Sep;28 (Suppl 1):49–54. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2214.2002.00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brocklehurst P., French R. The association between maternal HIV infection and perinatal outcome: a systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1998 Aug;105(8):836–848. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1998.tb10227.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns Paulette G. Reducing infant mortality rates using the perinatal periods of risk model. Public Health Nurs. 2005 Jan-Feb;22(1):2–7. doi: 10.1111/j.0737-1209.2005.22102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin Robert E., Robbins Wendie A., Schieve Laura A., Sweeney Anne M., Tabacova Sonia A., Tomashek Kay M. Off to a good start: the influence of pre- and periconceptional exposures, parental fertility, and nutrition on children's health. Environ Health Perspect. 2004 Jan;112(1):69–78. doi: 10.1289/ehp.6261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnattingius S., Haglund B. Socio-economic factors and feto-infant mortality. Scand J Soc Med. 1992 Mar;20(1):11–13. doi: 10.1177/140349489202000103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cnattingius S., Nordström M. L. Maternal smoking and feto-infant mortality: biological pathways and public health significance. Acta Paediatr. 1996 Dec;85(12):1400–1402. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1996.tb13943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietz P. M., Adams M. M., Spitz A. M., Morris L., Johnson C. H. Live births resulting from unintended pregnancies: is there variation among states? The PRAMS Working Group. Fam Plann Perspect. 1999 May-Jun;31(3):132–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunne F., Brydon P., Smith K., Gee H. Pregnancy in women with Type 2 diabetes: 12 years outcome data 1990-2002. Diabet Med. 2003 Sep;20(9):734–738. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2003.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evers Inge M., de Valk Harold W., Visser Gerard H. A. Risk of complications of pregnancy in women with type 1 diabetes: nationwide prospective study in the Netherlands. BMJ. 2004 Apr 5;328(7445):915–915. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38043.583160.EE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch Brian Karl. Early origins of the gradient: the relationship between socioeconomic status and infant mortality in the United States. Demography. 2003 Nov;40(4):675–699. doi: 10.1353/dem.2003.0033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch Brian Karl. Socioeconomic gradients and low birth-weight: empirical and policy considerations. Health Serv Res. 2003 Dec;38(6 Pt 2):1819–1841. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2003.00204.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebo Kelly A., Fleishman John A., Conviser Richard, Reilly Erin D., Korthuis P. Todd, Moore Richard D., Hellinger James, Keiser Philip, Rubin Haya R., Crane Lawrence. Racial and gender disparities in receipt of highly active antiretroviral therapy persist in a multistate sample of HIV patients in 2001. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005 Jan 1;38(1):96–103. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200501010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huestis Marilyn A., Choo Robin E. Drug abuse's smallest victims: in utero drug exposure. Forensic Sci Int. 2002 Aug 14;128(1-2):20–30. doi: 10.1016/s0379-0738(02)00160-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman J. C., Pierre M. B., Jr, Madans J. H., Land G. H., Schramm W. F. The effects of maternal smoking on fetal and infant mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 1988 Feb;127(2):274–282. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korenbrot Carol C., Steinberg Alycia, Bender Catherine, Newberry Sydne. Preconception care: a systematic review. Matern Child Health J. 2002 Jun;6(2):75–88. doi: 10.1023/a:1015460106832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDorman Marian F., Minino Arialdi M., Strobino Donna M., Guyer Bernard. Annual summary of vital statistics--2001. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6):1037–1052. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.6.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews T. J., Menacker Fay, MacDorman Marian F. Infant mortality statistics from the 2001 period linked birth/infant death data set. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2003 Sep 15;52(2):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry L. E. Preconception care: a health promotion opportunity. Nurse Pract. 1996 Nov;21(11):24-6, 32, 34 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg Kenneth D., Gelow Jill M., Sandoval Alfredo P. Pregnancy intendedness and the use of periconceptional folic acid. Pediatrics. 2003 May;111(5 Pt 2):1142–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers L., Price R. A. Preconception care. An opportunity to maximize health in pregnancy. J Nurse Midwifery. 1993 Jul-Aug;38(4):188–198. doi: 10.1016/0091-2182(93)90002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlahov David, Ahern Jennifer, Vazquez Tara, Johnson Stephen, Philips Laura A., Nash Denis, Mitchell Maria K., Freeman Harold. Racial/ethnic differences in screening for colon cancer: report from the New York Cancer Project. Ethn Dis. 2005 Winter;15(1):76–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]