Abstract

One of the major conceptual advances in our understanding of the pathogenesis of age-associated cardiovascular diseases has been the insight that age-related oxidative stress may promote vascular inflammation even in the absence of traditional risk factors associated with atherogenesis (e.g., hypertension or metabolic diseases). In the present review we summarize recent experimental data suggesting that mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species, innate immunity, the local TNF-α-converting enzyme (TACE)-TNF-α, and the renin-angiotensin system may underlie NF-κB induction and endothelial activation in aged arteries. The theme that emerges from this review is that multiple proinflammatory pathways converge on NF-κB in the aged arterial wall, and that the transcriptional activity of NF-κB is regulated by multiple nuclear factors during aging, including nuclear enzymes poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) and SIRT-1. We also discuss the possibility that nucleophosmin (NPM or nuclear phosphoprotein B23), a known modulator of the cellular oxidative stress response, may also regulate NF-κB activity in endothelial cells.

Keywords: senescence, resveratrol, caloric restriction, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase, renin-angiotensin system, coronary artery disease, stroke, myocardial infarction

there are over 35 million Americans 65 yr of age or older, and the majority of them will suffer from age-associated cardiovascular disease (53–55). Understanding the critical mechanisms underlying cardiovascular aging and age-related arterial pathophysiological alterations may hold promise in developing novel interventional treatments for promotion of cardiovascular health in older persons.

There is increasing evidence that in the absence of other risk factors, aging per se promotes development of atherosclerosis and increases the morbidity and mortality of myocardial infarction and stroke. The mechanisms by which endothelial oxidative stress and arterial inflammatory processes act as potent proatherogenic stimuli have been the subject of intense study. This review focuses on emerging evidence that reactive oxygen species (ROS) and activation of inflammatory pathways each play a central role in cardiovascular aging (52–55, 95), and discusses the role of NF-κB in the endothelial oxidative stress response during aging.

OXIDATIVE STRESS AND ARTERIAL INFLAMMATION IN AGED ARTERIES: ROLE OF NF-κB INDUCTION

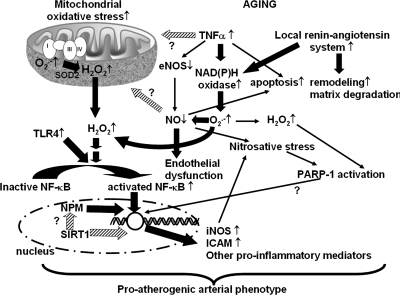

Since Harman originally proposed the free radical theory of aging (40), considerable evidence has been published that increased production of ROS underlies cellular dysfunction in various organ systems of aged humans and laboratory animals (19, 22, 32, 38, 88, 101). The oxidative stress theory of aging postulates that ROS induce a variety of macromolecular oxidative modifications, and accumulation of such oxidative damage is a primary causal factor in the aging process. There is also strong evidence that oxidative stress develops with age in the arterial system, both in humans (28, 30, 31, 33, 48) and laboratory animals (22, 32, 38, 88, 101). One of the consequences of increased oxidative stress in aging is a functional inactivation of NO by high concentrations of O2•−, resulting in enhanced ONOO− formation (1, 22, 28, 32, 48, 88). It is generally accepted that severe impairment of NO bioavailability during aging will decrease vasodilator capacity, thereby limiting tissue blood supply (19, 98). There is an emerging view that ROS, in addition to scavenging NO and causing oxidative damage, play important signaling roles during aging (Fig. 1), increasing production of ROS in arterial inflammation [reviewed recently elsewhere (15, 19, 52, 95, 96, 98)].

Fig. 1.

Proposed scheme for pathways contributing to cellular oxidative stress and NF-κB activation in aged endothelial cells. In aged endothelial cells, increased levels of O2•− generated by the electron transport chain and NAD(P)H oxidases [stimulated by elevated TNF-α levels and/or by the activated local renin-angiotensin system (RAS) in the vascular wall] are dismutated to H2O2. Increased cytoplasmic H2O2 levels and activation of toll-like receptors (TLRs) each contribute to the activation and nuclear translocation of NF-κB, which results in a proinflammatory shift in the endothelial gene expression profile, endothelial activation, and increased monocyte adhesiveness to the endothelium. The transcriptional activity of NF-κB is regulated by nucleophosmin (NPM) and SIRT-1 (hatched arrows represent inhibition), and both pathways exhibit age-related alterations. In addition, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP-1) activation also modulates transcriptional activity of NF-κB. Increased O2•− production and/or downregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) are mutually responsible for impaired bioavailability of NO and endothelial vasodilator dysfunction in aged arteries. The model predicts that upregulation of TNF-α and/or impaired NO bioavailability may also contribute to development of mitochondrial oxidative stress during aging. Increased TNF-α levels also promote endothelial apoptotic cell death, which, along with increased oxidative stress and vascular inflammation, increases the risk for coronary artery disease. iNOS, inducible nitric oxide synthase; SOD2, superoxide dismutase 2.

Inflammation is considered to be a critical initial step in the development of atherosclerosis during aging. Our recent studies demonstrate that arterial aging, even in the absence of traditional risk factors for atherosclerosis (hypertension, diabetes, smoking, etc.), is associated with a proinflammatory shift in gene expression profile (19, 22–24, 95). Proinflammatory changes in endothelial phenotype, known as “endothelial activation,” involve upregulation of cellular adhesion molecules, an increase in endothelial-leukocyte interactions and permeability, as well as alterations in the secretion of autocrine/paracrine factors, which are pivotal to inflammatory responses. There is increasing evidence that NF-κB activation plays a key role in endothelial activation in aging (13, 28, 89, 100). NF-κB is a redox-sensitive transcription factor that plays an important role in inflammatory phenotypic change in endothelial and smooth muscle cells in various pathophysiological conditions. Of note, recent studies have demonstrated that NF-κB binding increases during aging (28, 43, 100) and is likely responsible for the increased expression of adhesion molecules and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) found in aged coronary vessels (22), carotid arteries, and aortas (11, 100). NF-κB activation can induce the transcription of a large number of genes implicated in vascular inflammation, including adhesion molecules, cytokines, and chemokines, and it is generally believed that chronic activation of NF-κB predisposes arteries to atherosclerosis (37). Our study demonstrates that oxidative stress-mediated NF-κB activation increases monocyte adhesiveness to endothelial cells of aged arteries via induction of adhesion molecules (100). Accordingly, chronic pharmacological inhibition of NF-κB attenuates endothelial activation in aged rats (13, 89, 100). NF-κB activation and chronic inflammation seem to be a generalized phenomenon during aging, since increases in NF-κB activity have been observed in aged rat skeletal muscle, liver, brain, and cardiac muscle (43, 50, 79, 114). Numerous studies demonstrated that increased levels of ROS activate NF-κB in arterial cells. Here we present an overview of the possible pathways that may induce redox-dependent vascular NF-κB activation of aging.

MULTIPLE PATHWAYS CAN REGULATE NF-κB ACTIVATION PROMOTING ARTERIAL INFLAMMATION DURING AGING

In arterial cells, NF-κB is present as an inactive, IκB-bound complex in the cytoplasm. On stimulation NF-κB enters the nucleus and activates gene expression, a key step for controlling NF-κB activity via regulation of the interaction between IκB and NF-κB. Many signals that lead to activation of NF-κB converge on the ROS-dependent activation of a high-molecular-weight complex that contains an IκB kinase (IKK). Activation of IKK complex leads to the phosphorylation and degradation of IκB, consequently unmasking NF-κB. Pathways that converge on NF-κB may contribute to endothelial activation during aging, and include TNF-α signaling, mitochondrial ROS-induced pathways, the local renin-angiotensin system (RAS), and pathways associated with innate immunity (Fig. 1). NF-κB is also regulated by ubiquitination, acetylation, and prolyl isomerization, and the transactivation activity of NF-κB can be affected by phosphorylation and poly(ADP)-ribosylation. In the present review, we discuss the potential role of three nuclear factors, PARP-1, SIRT-1, and nucleophosmin, in regulation of NF-κB activity during aging.

Role of TNF-α in arterial inflammation in aging.

TNF-α is the prototypic proinflammatory cytokine and master regulator of endothelial activation via the NF-κB pathway. It has been repeatedly shown that circulating TNF-α levels are increased in aged animals and older humans (7, 84, 85, 111). We have demonstrated that in aged rodent coronary arteries, there is an upregulation of TNF-α (23, 24) associated with a gene expression profile suggestive of an inflammatory response (22–24, 32, 85, 95). Increased TNF-α production has been also demonstrated in the carotid arteries, aortic wall (6), and heart (58) of aged rodents. We have previously demonstrated that arterial endothelial and smooth muscle express the TNF-α-converting enzyme (TACE/ADAM17) (24), suggesting the presence of an autocrine/paracrine TNF-α-dependent regulatory pathway in the arterial wall. Because TNF-α can be secreted by arterial cells (due to the activity of TACE), it is likely that arterial TNF-α production contributes to elevated plasma concentrations of TNF-α in older organisms. It is also likely that, in addition to arterial cells and immunocytes, adipocytes are another significant source of circulating TNF-α (106). In this regard, it is significant that serum conditioned by adipocytes from aged mice can induce an inflammatory response in detector cells (106). Because an NF-κB binding site is present on the promoter region of the TNF-α gene (78), the possibility that increased circulating levels of TNF-α promote TNF-α expression in the arterial wall cannot be ruled out.

Importantly, our recent studies, as well as those conducted by other laboratories, have linked TNF-α to endothelial impairment during aging (4, 18). These studies have demonstrated that administration of exogenous TNF-α can induce oxidative stress by upregulating/activating NAD(P)H oxidase (18, 94), endothelial dysfunction (18), and endothelial apoptosis (18, 24). Importantly with respect to the present review, TNF-α is a potent activator of NF-κB in endothelial cells (18, 20).There is solid evidence that TNF-α activates NAD(P)H oxidase-dependent ROS generation, which then activates NF-κB. Accordingly, in endothelial cells (20), TNF-α treatment results in NF-κB-dependent upregulation of proatherogenic inflammatory mediators, such as iNOS and adhesion molecules, which can, in turn, be attenuated by NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitors. The effects induced by TNF-α closely mimic aging-induced functional and phenotypic alterations of the arterial endothelium (18, 22–24, 88, 101). Indeed, there are strong data suggesting that neutralization of TNF-α by chronic etanercept treatment improves endothelial function, attenuates oxidative stress, reduces arterial NADPH oxidase activity and expression, and attenuates expression of adhesion molecules (18). Etanercept (Enbrel) is an FDA-approved drug (composed of the extracellular ligand-binding portion of human TNF receptor 2) that binds and inactivates circulating TNF-α. Previous studies also suggest that increased endothelial apoptosis is a feature of advanced aging (16, 18, 22, 24). The results of both chronic etanercept treatment (16) and in vitro neutralization of TNF-α (24) decreased apoptotic cell death in aged vessels. This provides strong evidence that increased TNF-α levels during aging, in addition to promoting arterial inflammation, also initiate programmed endothelial cell death, which may likely contribute to age-related cardiovascular pathophysiology (95).

Role of mitochondrial oxidative stress in arterial inflammation during aging.

The mitochondrial theory of aging (41) postulates that mitochondria-derived H2O2 diffuses readily through cellular membranes, thereby contributing to a variety of macromolecular oxidative modifications. Several lines of evidence suggest that mitochondria are a major source of H2O2 in aged blood vessels (99, 100), which, in addition to causing oxidative damage, play important signaling roles. The findings that inhibition of mitochondrial ROS production or scavenging of H2O2 attenuates NF-κB activation and NF-κB-dependent gene expression in aged vessels (100) suggest that mitochondrial H2O2 production is involved in regulation of endothelial NF-κB activity. In contrast, it is likely that mitochondria-derived O2•− plays a lesser signaling role. First, O2•− is membrane impermeable (except in the protonated perhydroxyl radical form, which represents only a small fraction of total O2•− produced), whereas H2O2 easily penetrates the mitochondrial membranes. Second, because of efficient scavenging of O2•− by high levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in mitochondria, it is likely that mitochondria-derived H2O2 is a major factor in initiating inflammatory signaling processes in endothelial cells. This view is in line with the finding that exogenous H2O2 substantially increases NF-κB activation in vessels of young rats, mimicking the aging phenotype (100). It is interesting to note that mitochondrial oxidative stress in the cardiovascular system during aging is also associated with increased lipid peroxidation (49), and end products of lipid peroxidation were shown to induce NF-κB activation in endothelial cells in vitro (59). In addition, mitochondrial ROS-induced NF-κB is likely to upregulate the expression of inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α), which may further increase oxidative stress (e.g., by activating NADPH oxidases) and thereby NF-κB activation during aging. Collectively, these observations suggest that an associated decline in mitochondrial function is at least partially responsible for arterial inflammation in aging (100). Indeed, in aging mice that overexpress human catalase in the mitochondria (MCAT), cardiac pathology is delayed, oxidative damage is reduced, H2O2 production and H2O2-induced aconitase inactivation are attenuated, and the development of mitochondrial deletions is reduced (83). It would be of interest to elucidate whether inflammatory gene expression is also attenuated in the cardiovascular system of MCAT mice. Interestingly, mitochondria-derived H2O2 has been proposed as a vasodilator in coronary arteries in previous studies (67, 69). Yet, endothelial function in coronary arteries is significantly impaired during aging (22), suggesting that mitochondrial oxidative stress does not compensate for the loss of NO-mediated vasodilation.

The oxidative stress theory of aging predicts that longer-lived species should 1) produce less ROS and/or 2) exhibit superior resistance to the adverse effects of oxidative stress. In support of this theory, we have recently reported that successfully aging species, including the naked mole-rat (Heterocephalus glaber; maximum lifespan >28 yr), the white-footed mouse (Peromyscus leucopus; maximum lifespan >8 yr), and the little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus; maximum lifespan >30 yr), exhibit significantly lower arterial ROS production and/or superior cellular resistance to oxidative stress than the house mouse (Mus musculus; maximum lifespan ∼3.5 yr) (16, 51, 92, 97). Presently, it is unknown whether lower cellular and mitochondrial ROS production (57) in longer-lived species is associated with an attenuated arterial inflammatory response during aging compared with that in shorter-lived species.

We have recently demonstrated that aging is associated with impaired mitochondrial biogenesis in the arterial system (99). There is also increasing evidence that alterations in mitochondrial biogenesis are associated with mitochondrial dysfunction in various organs during aging [reviewed recently elsewhere (5, 15)]. It is thought that mitochondrial proliferation reduces the flow of electrons per unit mitochondria (if cellular energy demand is unchanged), which, per se, attenuates mitochondrial ROS production. Thus it is likely that impaired mitochondrial biogenesis during aging may contribute to increased mitochondrial oxidative stress, thereby increasing H2O2-mediated NF-κB activation, as well as induction of inflammatory gene expression. In this regard, it should be noted that TNF-α has been linked to mitochondrial dysregulation in vitro. Whether upregulated TNF-α plays a role in mitochondrial dysregulation and mitochondrial oxidative stress in aged arteries, however, is yet to be determined.

Role of the local RAS in arterial inflammation during aging.

Previous studies called attention to the association of an upregulated tissue RAS with intimal thickening and remodeling in large arteries of aged animals and humans (86, 102–104). The aforementioned studies demonstrated that angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), ANG II, ANG II receptor type 1, matrix metalloproteinases 2/9 (which can degrade the major components of the arterial extracellular matrix, contributing to intimal growth and vessel wall remodeling), and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (which can promote leukocyte infiltration) increase within the arterial wall during aging (56, 65, 86, 92, 102–104). The data so far suggest that upregulation of RAS contributes to chronic arterial inflammation during aging, enhancing arterial response to injury while rendering the arterial wall susceptible to the development of arterial diseases (including atherosclerosis and hypertension). ANG II is known to regulate NF-κB activity (44, 91), likely via a redox-sensitive pathway involving NAD(P)H oxidases (34). It is thus possible that activation of local RAS contributes to NF-κB induction and endothelial activation during aging. Indeed, some studies suggest that older patients with overt atherosclerotic plaques may benefit from pharmacological disruption of the local RAS (81).

Does innate immunity play a role in arterial inflammation during aging?

During the aging process, adaptive immunity significantly declines (“immunosenescence”). In contrast, recent data suggest that mechanisms related to innate immunity are upregulated/activated during aging (80). In their signaling, toll-like receptors (TLR) play a significant role in innate immune defense. TLR4 is activated by bacterial lipopolysaccharide and various endogenous ligands, including those produced in response to tissue injury. TLR4 activates NF-κB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades, which leads to a proinflammatory shift in cellular gene expression profile (39). TLRs are expressed in the arterial system, and there is increasing evidence linking upregulation/activation of TLRs to atherogenesis (2, 9, 45, 61, 70, 71, 82). Interestingly, recent studies demonstrated that multiple TLRs (including TLR1, TLR2, TLR4, TLR5, and TLR7) are upregulated in the mouse brain during aging (62). Our recent data suggest that TLR4 can be upregulated in the cardiovascular system of aged rodents, as well (Ungvari and Csiszar, unpublished observations). Thus the possibility that activation of innate immunity may contribute to arterial NF-κB activation and inflammatory gene expression during aging warrants further investigation.

Does PARP-1 play a role in arterial inflammation during aging?

One of the consequences of increased oxidative stress during aging is a functional inactivation of NO by high concentrations of O2•−, resulting in an enhanced peroxynitrite formation (1, 22, 32, 88). The possible downstream targets of peroxynitrite are multiple (for an excellent review, see Ref. 73). Both peroxynitrite and H2O2 in large concentrations can induce DNA single strand breaks, which may contribute to the endothelial damage during aging (35, 73, 76). DNA damage induced by oxidative/nitrosative stress may lead to the activation of the nuclear enzyme PARP-1 and its homologs (8, 76). PARP-1 belongs to the DNA damage surveillance network, and its catalytic activity is markedly stimulated on binding to DNA strand interruptions (8). There is increasing evidence that PARP-1 activity increases during aging (74, 75, 77). We have recently reviewed the role of nitrosative stress and the potential contribution of PARP-1 activation to cardiovascular aging (19). In brief, on its activation PARP-1 transfers 50–200 molecules of ADP-ribose to various nuclear proteins, including transcription factors and histones. As a result, PARP-1 activation has been shown to modulate the transcriptional regulation of various inflammatory genes (10, 36). Important for the present review are the findings that PARP-1 can regulate NF-κB activation (3, 42, 115). Future studies are definitely needed to elucidate the role of PARP activation during age-induced cardiovascular dysfunction and inflammation.

Role of SIRT1 in regulation of arterial inflammation during aging.

Studies from the past few years have revealed that the SIR2/SIRT1 (silent mating type information regulation 2 homolog 1) gene promotes a longer lifespan in evolutionarily distant organisms and may underlie the effects of dietary restriction to extend healthy lifespan (14, 46, 105). Recently, we found that resveratrol, the most potent naturally occurring SIRT1 activator compound (STAC) (46, 105), effectively attenuates TNF-α- and H2O2-induced endothelial activation by inhibiting NF-κB (17, 20). SIRT1, a nicotinamide adenosine dinucleotide-dependent protein deacetylase, is likely to directly regulate the transcriptional activity of NF-κB (112). Indeed, SIRT1 was reported to physically interact with the RelA/p65 subunit of NF-κB and to inhibit transcription by deacetylating RelA/p65 (112). Whether age-associated alterations of SIRT1 activity play a role in arterial inflammation during aging has yet to be determined. SIRT1 is thought to mediate, at least in part, the effects of caloric restriction (98). In this regard it is important to note that caloric restriction abrogates arterial NF-κB activation during aging (98). Resveratrol was shown to extend longevity in lower organisms while mimicking the effects of caloric restriction (46, 105), and there is good reason to believe that it also exerts antiaging activity (including attenuation of arterial inflammation) in mammals (recently reviewed in Ref. 52). In this regard, it should be noted that there are also studies showing that higher concentrations of resveratrol exhibit direct antioxidant properties (47, 60, 87), which may further enhance the cytoprotective effects of SIRT1 induction.

Does nucleophosmin regulate NF-κB activity in endothelial cells during aging?

Nucleophosmin (NPM or nuclear phosphoprotein B23) is a ubiquitously expressed multifunctional nuclear phosphoprotein that constantly shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm (109, 113). Although the role of NPM in arterial pathophysiology is almost completely unknown, it is important to note that many of the known functions of NPM are related to oxidative stress response, the maintenance of genomic stability, transcriptional gene regulation, and control of cellular senescence and apoptosis, all of which are of interest to arterial biologists and researchers of aging. NPM takes part in various cellular processes by shuttling between cellular compartments, orchestrating cellular repair pathways and modulating cellular stress responses [including the responses to UV irradiation (68, 107, 108, 110) and hypoxia (64)]. NPM participates in DNA repair processes (68), and it also seems to control pathways regulating cellular senescence and apoptotic cell death (12, 63). There is also evidence that NPM is overexpressed in cancer cells, and it has been shown to be involved in both positive and negative regulation of transcription (116). It is thought that, by regulating histone acetylation (116), NPM plays an important role in the regulation of transcription through modulation of chromatin condensation and decondensation events (90). Indeed, NPM enhances the acetylation-dependent chromatin transcription and becomes acetylated both in vitro and in vivo (90).

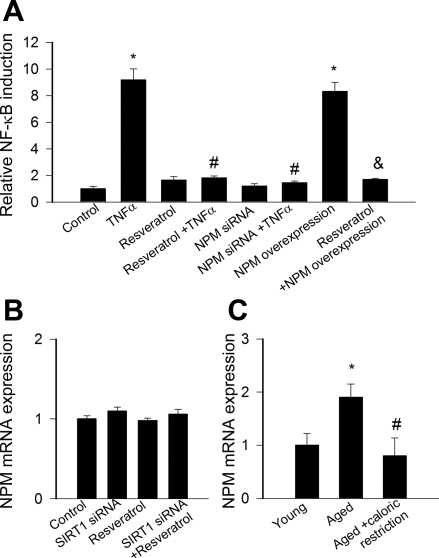

Our recent findings indicate that NPM can regulate NF-κB activity in endothelial cells (Fig. 2). Specifically, TNF-α-induced NF-κB activation is significantly reduced in cultured human coronary arterial endothelial cells following knockdown of NPM (Fig. 2A). In contrast, overexpression of NPM per se increased endothelial NF-κB activity (Fig. 2A). In accordance with our findings, a recent study demonstrated physical interaction between NPM and NF-κB and provided evidence that overexpression of NPM leads to increased MnSOD gene transcription in a dose-dependent manner (25). MnSOD, a mitochondrial antioxidant enzyme regulated by NF-κB, is essential for protecting the functional integrity of mitochondria during aging. Consistent with this, expression of small interfering RNA (siRNA) for NPM leads to inhibition of MnSOD gene transcription (25). Based on immunoprecipitation experiments, NPM was also found to be associated with NF-κB in U1 bladder cancer cells (66). Interestingly, on siRNA-mediated knockdown of intracellular NPM, inhibition of NF-κB with concomitant target gene inactivation has been observed in this model as well (66). Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis, Dhar et al. (26) have recently demonstrated that Sp1 and NPM interact in vivo to enhance NF-κB-mediated gene induction. Interaction between NPM and NF-κB at the promoter and enhancer of the MnSOD gene in vivo was verified by the presence of PCR products from the promoter and enhancer elements in the ChIP assay (26). Interestingly, the transcription factor p53 also appears to be a component of the NPM-containing complex (26). Our studies also demonstrate that the SIRT1 activator resveratrol effectively inhibits NF-κB activation in endothelial cells induced by NPM overexpression (Fig. 2A). It seems that neither resveratrol nor SIRT1 regulates NPM at the transcriptional level (Fig. 2B), but we hypothesize that SIRT1 may prevent NPM-induced NF-κB activation by directly deacetylating NF-κB. A possible SIRT1-NPM interaction, however, cannot be ruled out. Importantly, expression of NPM seems to increase in carotid arteries of aged F344 rats (Fig. 2C). Accordingly, recent studies also suggest that expression of NPM tends to be upregulated during aging in skeletal muscle (29) and during heart aging (27). It is tempting to speculate that these age-related alterations in NPM expression/activity would promote NF-κB activation in older cells. This idea is further supported by the finding that caloric restriction, which inhibits arterial NF-κB activation during aging (98), reduces NPM expression in aged vessels (Fig. 2C). Additional studies are needed to elucidate the role of NPM in regulation of gene expression in cardiovascular aging and pathophysiological conditions associated with accelerated arterial aging.

Fig. 2.

A: reporter gene assay demonstrates the knockdown effects of NPM [by small interfering RNA (siRNA)] on TNF-α (10 ng/ml)-induced NF-κB reporter activity in cultured primary human coronary arterial endothelial cells (HCAECs). The resulting overexpression of NPM with respect to endothelial NF-κB activation is also shown, as well as effects of resveratrol (10 μmol/l) on TNF-α (10 ng/ml)-induced NF-κB reporter activity. Cells were transiently cotransfected with NF-κB-driven firefly luciferase and CMV-driven Renilla luciferase constructs, followed by NPM knockdown, NPM overexpression, or TNF-α stimulation. Cells were then lysed and subjected to luciferase activity assay. Following normalization, relative luciferase activity was obtained from 6 independent transfections. Data are means ± SE. *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. TNF-α only; &P < 0.05 vs. NPM overexpression. B: effect of knockdown of SIRT-1 (siRNA) and/or resveratrol (10 μmol/l) treatment on mRNA expression of NPM in cultured HCAECs. Analysis of mRNA expression was performed by real-time QRT-PCR. β-Actin was used for normalization. Data are means ± SE (n = 5 for each group). C: NPM mRNA expression in carotid arteries of ad libitum-fed young (3 mo old), ad libitum fed aged (28 mo old), and caloric-restricted aged (28 mo old) F344 rats. Analysis of mRNA expression was performed by real-time QRT-PCR. β-Actin was used for normalization. Data are means ± SE (n = 5 for each group). *P < 0.05. vs. young; #P < 0.05 vs. ad libitum-fed aged. All animal use protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the New York Medical College, Valhalla, NY.

Perspectives

In conclusion, aging per se, in the absence of other risk factors [hypertension (21), hypercholesterolemia, hyperhomocysteinemia (93, 94), diabetes mellitus, smoking (72)] is associated with oxidative/nitrosative stress and inflammatory changes in the phenotype of blood vessels. Age-associated induction of NF-κB activation is especially interesting, since it seems to contribute significantly to endothelial activation in aged vessels, which is a critical initial step in the development of atherogenesis. Several proatherogenic pathways converge on NF-κB (Fig. 1), including the local TACE-TNF-α system, the local RAS, and pathways involved in innate immunity. In addition, there is strong evidence suggesting a link between mitochondrial oxidative stress and NF-κB activation during aging. Whether novel treatments targeting the factors that regulate NF-κB activity (e.g., SIRT1 activators, PARP-1 inhibitors) or attenuating mitochondrial oxidative stress are able to reverse or delay the age-induced arterial inflammation and the functional decline of the cardiovascular system remains a subject of current debate. It also remains to be seen whether animals genetically deficient in (or who show an overexpression of) TNF-α, TLRs, SIRT-1, and PARP-1 exhibit arterial phenotypic alterations during aging.

Future studies need to elucidate the link between age-related oxidative stress and arterial inflammation in successfully aging species and explore interspecies differences in NF-κB signaling and action of SIRT-1 and NPM. Finally, studies on humans and nonhuman primates are evidently needed to better understand the generality of age-related arterial phenotypic changes observed in laboratory animals.

Overall, to the benefit of older patients, we can expect recent advances in our understanding of oxidative/nitrosative stress and redox-sensitive inflammatory mechanisms to yield novel therapeutic approaches in the study of cardiovascular aging.

GRANTS

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Aging (M. Wang and E. Lakatta), by grants from the American Heart Association (0430108N, 0435140N to A. Csiszar and Z. Ungvari) and the National Institutes of Health (HL-077256 and HL-43023 to Z. Ungvari), the American Diabetes Association, American Federation for Aging Research (A. Csiszar), and by Philip Morris and Philip Morris International (to Z. Ungvari).

REFERENCES

- 1.Adler A, Messina E, Sherman B, Wang Z, Huang H, Linke A, Hintze TH. NAD(P)H oxidase-generated superoxide anion accounts for reduced control of myocardial O2 consumption by NO in old Fischer 344 rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 285: H1015–H1022, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ameziane N, Beillat T, Verpillat P, Chollet-Martin S, Aumont MC, Seknadji P, Lamotte M, Lebret D, Ollivier V, de Prost D. Association of the Toll-like receptor 4 gene Asp299Gly polymorphism with acute coronary events. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: e61–e64, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreone TL, O'Connor M, Denenberg A, Hake PW, Zingarelli B. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 regulates activation of activator protein-1 in murine fibroblasts. J Immunol 170: 2113–2120, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arenas IA, Xu Y, Davidge ST. Age-associated impairment in vasorelaxation to fluid shear stress in the female vasculature is improved by TNF-α antagonism. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H1259–H1263, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, aging. Cell 120: 483–495, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Belmin J, Bernard C, Corman B, Merval R, Esposito B, Tedgui A. Increased production of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 by arterial wall of aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 268: H2288–H2293, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruunsgaard H, Skinhoj P, Pedersen AN, Schroll M, Pedersen BK. Ageing, tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) and atherosclerosis. Clin Exp Immunol 121: 255–260, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkle A, Beneke S, Muiras ML. Poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation and aging. Exp Gerontol 39: 1599–1601, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Candore G, Aquino A, Balistreri CR, Bulati M, Di Carlo D, Grimaldi MP, Listi F, Orlando V, Vasto S, Caruso M, Colonna-Romano G, Lio D, Caruso C. Inflammation, longevity, and cardiovascular diseases: role of polymorphisms of TLR4. Ann NY Acad Sci 1067: 282–287, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrillo A, Monreal Y, Ramirez P, Marin L, Parrilla P, Oliver FJ, Yelamos J. Transcription regulation of TNF-alpha-early response genes by poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 in murine heart endothelial cells. Nucleic Acids Res 32: 757–766, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cernadas MR, Sanchez de Miguel L, Garcia-Duran M, Gonzalez-Fernandez F, Millas I, Monton M, Rodrigo J, Rico L, Fernandez P, de Frutos T, Rodriguez-Feo JA, Guerra J, Caramelo C, Casado S, Lopez F. Expression of constitutive and inducible nitric oxide synthases in the vascular wall of young and aging rats. Circ Res 83: 279–286, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan PK, Chan FY. A study of correlation between NPM-translocation and apoptosis in cells induced by daunomycin. Biochem Pharmacol 57: 1265–1273, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chung HY, Sung B, Jung KJ, Zou Y, Yu BP. The molecular inflammatory process in aging. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 572–581, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen HY, Miller C, Bitterman KJ, Wall NR, Hekking B, Kessler B, Howitz KT, Gorospe M, de Cabo R, Sinclair DA. Calorie restriction promotes mammalian cell survival by inducing the SIRT1 deacetylase. Science 305: 390–392, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Orosz Z, Ungvari Z. Altered mitochondrial energy metabolism may play a role in vascular aging. Med Hypotheses 67: 904–908, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Orosz Z, Xiangmin Z, Buffenstein R, Ungvari Z. Vascular aging in the longest-living rodent, the naked mole rat. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H919–H927, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Podlutsky A, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Zhang C, Mukhopadhyay P, Pacher P, Hu F, de Cabo R, Ballabh P, Ungvari ZI. Vasoprotective effects of resveratrol and SIRT1: attenuation of cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and proinflammatory phenotypic alterations. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2721–H2735, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Smith K, Rivera A, Orosz Z, Ungvari Z. Vasculoprotective effects of anti-tumor necrosis factor-α treatment in aging. Am J Pathol 170: 388–698, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csiszar A, Pacher P, Kaley G, Ungvari Z. Role of oxidative and nitrosative stress, longevity genes and poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase in cardiovascular dysfunction associated with aging. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 3: 285–291, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Csiszar A, Smith K, Labinskyy N, Orosz Z, Rivera A, Ungvari Z. Resveratrol attenuates TNF-α-induced activation of coronary arterial endothelial cells: role of NF-κB inhibition. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1694–H1699, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Csiszar A, Smith KE, Koller A, Kaley G, Edwards JG, Ungvari Z. Regulation of bone morphogenetic protein-2 expression in endothelial cells: role of nuclear factor-kappaB activation by tumor necrosis factor-alpha, H2O2, and high intravascular pressure. Circulation 111: 2364–2372, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Edwards JG, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Koller A, Kaley G. Aging-induced phenotypic changes and oxidative stress impair coronary arteriolar function. Circ Res 90: 1159–1166, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Koller A, Edwards JG, Kaley G. Aging-induced proinflammatory shift in cytokine expression profile in rat coronary arteries. FASEB J 17: 1183–1185, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Koller A, Edwards JG, Kaley G. Proinflammatory phenotype of coronary arteries promotes endothelial apoptosis in aging. Physiol Genomics 17: 21–30, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhar SK, Lynn BC, Daosukho C, St. Clair DK. Identification of nucleophosmin as an NF-kappaB co-activator for the induction of the human SOD2 gene. J Biol Chem 279: 28209–28219, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dhar SK, Xu Y, Chen Y, St. Clair DK. Specificity protein 1-dependent p53-mediated suppression of human manganese superoxide dismutase gene expression. J Biol Chem 281: 21698–21709, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dobson JG, Fray J, Leonard JL, Pratt RE. Molecular mechanisms of reduced beta-adrenergic signaling in the aged heart as revealed by genomic profiling. Physiol Genomics 15: 142–147, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donato AJ, Eskurza I, Silver AE, Levy AS, Pierce GL, Gates PE, Seals DR. Direct evidence of endothelial oxidative stress with aging in humans: relation to impaired endothelium-dependent dilation and upregulation of nuclear factor-kappaB. Circ Res 100: 1659–1666, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Edwards MG, Anderson RM, Yuan M, Kendziorski CM, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Gene expression profiling of aging reveals activation of a p53-mediated transcriptional program. BMC Genomics 8: 80, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eskurza I, Kahn ZD, Seals DR. Xanthine oxidase does not contribute to impaired peripheral conduit artery endothelium-dependent dilatation with ageing. J Physiol 571: 661–668, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eskurza I, Monahan KD, Robinson JA, Seals DR. Effect of acute and chronic ascorbic acid on flow-mediated dilatation with sedentary and physically active human ageing. J Physiol 556: 315–324, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Francia P, delli Gatti C, Bachschmid M, Martin-Padura I, Savoia C, Migliaccio E, Pelicci PG, Schiavoni M, Luscher TF, Volpe M, Cosentino F. Deletion of p66shc gene protects against age-related endothelial dysfunction. Circulation 110: 2889–2895, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gates PE, Boucher ML, Silver AE, Monahan KD, Seals DR. Impaired flow-mediated dilation with age is not explained by l-arginine bioavailability or endothelial asymmetric dimethylarginine protein expression. J Appl Physiol 102: 63–71, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Griendling KK, Minieri CA, Ollerenshaw JD, Alexander RW. Angiotensin II stimulates NADH and NADPH oxidase activity in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 74: 1141–1148, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guo ZM, Yang H, Hamilton ML, VanRemmen H, Richardson A. Effects of age and food restriction on oxidative DNA damage and antioxidant enzyme activities in the mouse aorta. Mech Ageing Dev 122: 1771–1786, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ha HC, Hester LD, Snyder SH. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 dependence of stress-induced transcription factors and associated gene expression in glia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 3270–3275, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hajra L, Evans AI, Chen M, Hyduk SJ, Collins T, Cybulsky MI. The NF-kappa B signal transduction pathway in aortic endothelial cells is primed for activation in regions predisposed to atherosclerotic lesion formation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 9052–9057, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hamilton CA, Brosnan MJ, McIntyre M, Graham D, Dominiczak AF. Superoxide excess in hypertension and aging: a common cause of endothelial dysfunction. Hypertension 37: 529–534, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harari OA, Alcaide P, Ahl D, Luscinskas FW, Liao JK. Absence of TRAM restricts Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in vascular endothelial cells to the MyD88 pathway. Circ Res 98: 1134–1140, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harman D Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol: 298–300, 1956. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Harman D The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc 20: 145–147, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hassa PO, Hottiger MO. A role of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase in NF-kappaB transcriptional activation. Biol Chem 380: 953–959, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Helenius M, Hanninen M, Lehtinen SK, Salminen A. Aging-induced up-regulation of nuclear binding activities of oxidative stress responsive NF-kB transcription factor in mouse cardiac muscle. J Mol Cell Cardiol 28: 487–498, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hernandez-Presa M, Bustos C, Ortego M, Tunon J, Renedo G, Ruiz-Ortega M, Egido J. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition prevents arterial nuclear factor-kappa B activation, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 expression, and macrophage infiltration in a rabbit model of early accelerated atherosclerosis. Circulation 95: 1532–1541, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hollestelle SC, De Vries MR, Van Keulen JK, Schoneveld AH, Vink A, Strijder CF, Van Middelaar BJ, Pasterkamp G, Quax PH, De Kleijn DP. Toll-like receptor 4 is involved in outward arterial remodeling. Circulation 109: 393–398, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howitz KT, Bitterman KJ, Cohen HY, Lamming DW, Lavu S, Wood JG, Zipkin RE, Chung P, Kisielewski A, Zhang LL, Scherer B, Sinclair DA. Small molecule activators of sirtuins extend Saccharomyces cerevisiae lifespan. Nature 425: 191–196, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hung LM, Chen JK, Huang SS, Lee RS, Su MJ. Cardioprotective effect of resveratrol, a natural antioxidant derived from grapes. Cardiovasc Res 47: 549–555, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jablonski KL, Seals DR, Eskurza I, Monahan KD, Donato AJ. High-dose ascorbic acid infusion abolishes chronic vasoconstriction and restores resting leg blood flow in healthy older men. J Appl Physiol 103: 1715–1721, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Judge S, Jang YM, Smith A, Hagen T, Leeuwenburgh C. Age-associated increases in oxidative stress and antioxidant enzyme activities in cardiac interfibrillar mitochondria: implications for the mitochondrial theory of aging. FASEB J 19: 419–421, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Korhonen P, Helenius M, Salminen A. Age-related changes in the regulation of transcription factor NF-kappa B in rat brain. Neurosci Lett 225: 61–64, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Labinskyy N, Csiszar A, Orosz Z, Smith K, Rivera A, Buffenstein R, Ungvari Z. Comparison of endothelial function, O2•−, and H2O2 production, and vascular oxidative stress resistance between the longest-living rodent, the naked mole rat, and mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H2698–H2704, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Labinskyy N, Csiszar A, Veress G, Stef G, Pacher P, Oroszi G, Wu J, Ungvari Z. Vascular dysfunction in aging: potential effects of resveratrol, an anti-inflammatory phytoestrogen. Curr Med Chem 13: 989–996, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lakatta EG Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises: Part III: cellular and molecular clues to heart and arterial aging. Circulation 107: 490–497, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises. I. Aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation 107: 139–146, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises. II. The aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation 107: 346–354, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lakatta EG, Mitchell JH, Pomerance A, Rowe GG. Human aging: changes in structure and function. J Am Coll Cardiol 10: 42A–47A, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lambert AJ, Boysen HM, Buckingham JA, Yang T, Podlutsky A, Austad SN, Kunz TH, Buffenstein R, Brand MD. Low rates of hydrogen peroxide production by isolated heart mitochondria associate with long maximum lifespan in vertebrate homeotherms. Aging Cell 6: 607–618, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lee CK, Allison DB, Brand J, Weindruch R, Prolla TA. Transcriptional profiles associated with aging and middle age-onset caloric restriction in mouse hearts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 14988–14993, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee JY, Je JH, Jung KJ, Yu BP, Chung HY. Induction of endothelial iNOS by 4-hydroxyhexenal through NF-kappaB activation. Free Radic Biol Med 37: 539–548, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Leiro J, Alvarez E, Arranz JA, Laguna R, Uriarte E, Orallo F. Effects of cis-resveratrol on inflammatory murine macrophages: antioxidant activity and down-regulation of inflammatory genes. J Leukoc Biol 75: 1156–1165, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lepper PM, von Eynatten M, Humpert PM, Triantafilou M, Triantafilou K. Toll-like receptor polymorphisms and carotid artery intima-media thickness. Stroke 38: e50, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Letiembre M, Hao W, Liu Y, Walter S, Mihaljevic I, Rivest S, Hartmann T, Fassbender K. Innate immune receptor expression in normal brain aging. Neuroscience 146: 248–254, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li J, Sejas DP, Burma S, Chen DJ, Pang Q. Nucleophosmin suppresses oncogene-induced apoptosis and senescence and enhances oncogenic cooperation in cells with genomic instability. Carcinogenesis 28: 1163–1170, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li J, Zhang X, Sejas DP, Bagby GC, Pang Q. Hypoxia-induced nucleophosmin protects cell death through inhibition of p53. J Biol Chem 279: 41275–41279, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li Z, Froehlich J, Galis ZS, Lakatta EG. Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in the thickened intima of aged rats. Hypertension 33: 116–123, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lin CY, Liang YC, Yung BY. Nucleophosmin/B23 regulates transcriptional activation of E2F1 via modulating the promoter binding of NF-kappaB, E2F1 and pRB. Cell Signal 18: 2041–2048, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Liu Y, Zhao H, Li H, Kalyanaraman B, Nicolosi AC, Gutterman DD. Mitochondrial sources of H2O2 generation play a key role in flow-mediated dilation in human coronary resistance arteries. Circ Res 93: 573–580, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Meder VS, Boeglin M, de Murcia G, Schreiber V. PARP-1 and PARP-2 interact with nucleophosmin/B23 and accumulate in transcriptionally active nucleoli. J Cell Sci 118: 211–222, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miura H, Bosnjak JJ, Ning G, Saito T, Miura M, Gutterman DD. Role for hydrogen peroxide in flow-induced dilation of human coronary arterioles. Circ Res 92: e31–e40, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Mullick AE, Soldau K, Kiosses WB, Bell TA, 3rd Tobias PS, Curtiss LK. Increased endothelial expression of Toll-like receptor 2 at sites of disturbed blood flow exacerbates early atherogenic events. J Exp Med 205: 373–383, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mullick AE, Tobias PS, Curtiss LK. Modulation of atherosclerosis in mice by Toll-like receptor 2. J Clin Invest 115: 3149–3156, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Orosz Z, Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Smith K, Kaminski PM, Ferdinandy P, Wolin MS, Rivera A, Ungvari Z. Cigarette smoke-induced proinflammatory alterations in the endothelial phenotype: role of NAD(P)H oxidase activation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H130–H139, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Pacher P, Beckman JS, Liaudet L. Nitric oxide and peroxynitrite in health and disease. Physiol Rev 87: 315–424, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pacher P, Mabley JG, Soriano FG, Liaudet L, Komjati K, Szabo C. Endothelial dysfunction in aging animals: the role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase activation. Br J Pharmacol 135: 1347–1350, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pacher P, Mabley JG, Soriano FG, Liaudet L, Szabo C. Activation of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase contributes to the endothelial dysfunction associated with hypertension and aging. Int J Mol Med 9: 659–664, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pacher P, Szabo C. Role of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP-1) in cardiovascular diseases: the therapeutic potential of PARP inhibitors. Cardiovasc Drug Rev 25: 235–260, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pacher P, Vaslin A, Benko R, Mabley JG, Liaudet L, Hasko G, Marton A, Batkai S, Kollai M, Szabo C. A new, potent poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase inhibitor improves cardiac and vascular dysfunction associated with advanced aging. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311: 485–491, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pelletier C, Varin-Blank N, Rivera J, Iannascoli B, Marchand F, David B, Weyer A, Blank U. Fc epsilonRI-mediated induction of TNF-alpha gene expression in the RBL-2H3 mast cell line: regulation by a novel NF-kappaB-like nuclear binding complex. J Immunol 161: 4768–4776, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Radak Z, Chung HY, Naito H, Takahashi R, Jung KJ, Kim HJ, Goto S. Age-associated increase in oxidative stress and nuclear factor kappaB activation are attenuated in rat liver by regular exercise. FASEB J 18: 749–750, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Salminen A, Huuskonen J, Ojala J, Kauppinen A, Kaarniranta K, Suuronen T. Activation of innate immunity system during aging: NF-kB signaling is the molecular culprit of inflamm-aging. Ageing Res Rev 7: 83–105, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sattler KJ, Woodrum JE, Galili O, Olson M, Samee S, Meyer FB, Zhu XY, Lerman LO, Lerman A. Concurrent treatment with renin-angiotensin system blockers and acetylsalicylic acid reduces nuclear factor kappaB activation and C-reactive protein expression in human carotid artery plaques. Stroke 36: 14–20, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schoneveld AH, Hoefer I, Sluijter JP, Laman JD, de Kleijn DP, Pasterkamp G. Atherosclerotic lesion development and Toll like receptor 2 and 4 responsiveness. Atherosclerosis 197: 95–104, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schriner SE, Linford NJ, Martin GM, Treuting P, Ogburn CE, Emond M, Coskun PE, Ladiges W, Wolf N, Van Remmen H, Wallace DC, Rabinovitch PS. Extension of murine life span by overexpression of catalase targeted to mitochondria. Science 308: 1909–1911, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schulz S, Schagdarsurengin U, Suss T, Muller-Werdan U, Werdan K, Glaser C. Relation between the tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) gene and protein expression, and clinical, biochemical, and genetic markers: age, body mass index and uric acid are independent predictors for an elevated TNF-alpha plasma level in a complex risk model. Eur Cytokine Netw 15: 105–111, 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Spaulding CC, Walford RL, Effros RB. Calorie restriction inhibits the age-related dysregulation of the cytokines TNF-alpha and IL-6 in C3B10RF1 mice. Mech Ageing Dev 93: 87–94, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Spinetti G, Wang M, Monticone R, Zhang J, Zhao D, Lakatta EG. Rat aortic MCP-1 and its receptor CCR2 increase with age and alter vascular smooth muscle cell function. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 24: 1397–1402, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stivala LA, Savio M, Carafoli F, Perucca P, Bianchi L, Maga G, Forti L, Pagnoni UM, Albini A, Prosperi E, Vannini V. Specific structural determinants are responsible for the antioxidant activity and the cell cycle effects of resveratrol. J Biol Chem 276: 22586–22594, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sun D, Huang A, Yan EH, Wu Z, Yan C, Kaminski PM, Oury TD, Wolin MS, Kaley G. Reduced release of nitric oxide to shear stress in mesenteric arteries of aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 286: H2249–H2256, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sung B, Park S, Yu BP, Chung HY. Amelioration of age-related inflammation and oxidative stress by PPARgamma activator: suppression of NF-kappaB by 2,4-thiazolidinedione. Exp Gerontol 41: 590–599, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Swaminathan V, Kishore AH, Febitha KK, Kundu TK. Human histone chaperone nucleophosmin enhances acetylation-dependent chromatin transcription. Mol Cell Biol 25: 7534–7545, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tham DM, Martin-McNulty B, Wang YX, Wilson DW, Vergona R, Sullivan ME, Dole W, Rutledge JC. Angiotensin II is associated with activation of NF-kappaB-mediated genes and downregulation of PPARs. Physiol Genomics 11: 21–30, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ungvari Z, Buffenstein R, Austad SN, Podlutsky A, Kaley G, Csiszar A. Oxidative stress in vascular senescence: lessons from successfully aging species. Front Biosci May 1: 5056–5070, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Bagi Z, Koller A. Impaired nitric oxide-mediated flow-induced coronary dilation in hyperhomocysteinemia: morphological and functional evidence for increased peroxynitrite formation. Am J Pathol 161: 145–153, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Edwards JG, Kaminski PM, Wolin MS, Kaley G, Koller A. Increased superoxide production in coronary arteries in hyperhomocysteinemia: role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, NAD(P)H oxidase, and inducible nitric oxide synthase. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 23: 418–424, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ungvari Z, Csiszar A, Kaley G. Vascular Inflammation in Aging. Herz 29: 733–740, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Ungvari Z, Gupte SA, Recchia FA, Batkai S, Pacher P. Role of oxidative-nitrosative stress and downstream pathways in various forms of cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 3: 221–229, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Ungvari Z, Krasnikov BF, Csiszar A, Labinskyy N, Mukhopadhyay P, Pacher P, Cooper AJL, Podlutskaya N, Austad SN, Podlutsky A. Testing hypotheses of aging in long-lived mice of the genus Peromyscus: association between longevity and mitochondrial stress resistance, ROS detoxification pathways and DNA repair efficiency. AGE. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 98.Ungvari Z, Parrado-Fernandez C, Csiszar A, de Cabo R. Mechanisms underlying caloric restriction and lifespan regulation: implications for vascular aging. Circ Res 102: 519–528, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ungvari ZI, Labinskyy N, Gupte SA, Chander PN, Edwards JG, Csiszar A. Dysregulation of mitochondrial biogenesis in vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells of aged rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H2121–H2128, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ungvari ZI, Orosz Z, Labinskyy N, Rivera A, Xiangmin Z, Smith KE, Csiszar A. Increased mitochondrial H2O2 production promotes endothelial NF-kB activation in aged rat arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H37–H47, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.van der Loo B, Labugger R, Skepper JN, Bachschmid M, Kilo J, Powell JM, Palacios-Callender M, Erusalimsky JD, Quaschning T, Malinski T, Gygi D, Ullrich V, Lüscher TF. Enhanced peroxynitrite formation is associated with vascular aging. J Exp Med 192: 1731–1744, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang M, Takagi G, Asai K, Resuello RG, Natividad FF, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Lakatta EG. Aging increases aortic MMP-2 activity and angiotensin II in nonhuman primates. Hypertension 41: 1308–1316, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Wang M, Zhang J, Jiang LQ, Spinetti G, Pintus G, Monticone R, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R, Lakatta EG. Proinflammatory profile within the grossly normal aged human aortic wall. Hypertension 50: 219–227, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang M, Zhang J, Spinetti G, Jiang LQ, Monticone R, Zhao D, Cheng L, Krawczyk M, Talan M, Pintus G, Lakatta EG. Angiotensin II activates matrix metalloproteinase type II and mimics age-associated carotid arterial remodeling in young rats. Am J Pathol 167: 1429–1442, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wood JG, Rogina B, Lavu S, Howitz K, Helfand SL, Tatar M, Sinclair D. Sirtuin activators mimic caloric restriction and delay ageing in metazoans. Nature 430: 686–689, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wu D, Ren Z, Pae M, Guo W, Cui X, Merrill AH, Meydani SN. Aging up-regulates expression of inflammatory mediators in mouse adipose tissue. J Immunol 179: 4829–4839, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wu MH, Chang JH, Chou CC, Yung BY. Involvement of nucleophosmin/B23 in the response of HeLa cells to UV irradiation. Int J Cancer 97: 297–305, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu MH, Chang JH, Yung BY. Resistance to UV-induced cell-killing in nucleophosmin/B23 over-expressed NIH 3T3 fibroblasts: enhancement of DNA repair and up-regulation of PCNA in association with nucleophosmin/B23 over-expression. Carcinogenesis 23: 93–100, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu MH, Lam CY, Yung BY. Translocation of nucleophosmin from nucleoli to nucleoplasm requires ATP. Biochem J 305: 987–992, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu MH, Yung BY. UV stimulation of nucleophosmin/B23 expression is an immediate-early gene response induced by damaged DNA. J Biol Chem 277: 48234–48240, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yamamoto K, Shimokawa T, Yi H, Isobe K, Kojima T, Loskutoff DJ, Saito H. Aging and obesity augment the stress-induced expression of tissue factor gene in the mouse. Blood 100: 4011–4018, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Yeung F, Hoberg JE, Ramsey CS, Keller MD, Jones DR, Frye RA, Mayo MW. Modulation of NF-kappaB-dependent transcription and cell survival by the SIRT1 deacetylase. EMBO J 23: 2369–2380, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yun JP, Chew EC, Liew CT, Chan JY, Jin ML, Ding MX, Fai YH, Li HK, Liang XM, Wu QL. Nucleophosmin/B23 is a proliferate shuttle protein associated with nuclear matrix. J Cell Biochem 90: 1140–1148, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Zhang J, Dai J, Lu Y, Yao Z, O'Brien CA, Murtha JM, Qi W, Hall DE, Manolagas SC, Ershler WB, Keller ET. In vivo visualization of aging-associated gene transcription: evidence for free radical theory of aging. Exp Gerontol 39: 239–247, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zingarelli B, Hake PW, O'Connor M, Denenberg A, Kong S, Aronow BJ. Absence of poly(ADP-ribose)polymerase-1 alters nuclear factor-kappa B activation and gene expression of apoptosis regulators after reperfusion injury. Mol Med 9: 143–153, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zou Y, Wu J, Giannone RJ, Boucher L, Du H, Huang Y, Johnson DK, Liu Y, Wang Y. Nucleophosmin/B23 negatively regulates GCN5-dependent histone acetylation and transactivation. J Biol Chem 283: 5728–5737, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]