Abstract

The objective was to evaluate the pulmonary disposition of the ubiquinone homolog coenzyme Q1 (CoQ1) on passage through lungs of normoxic (exposed to room air) and hyperoxic (exposed to 85% O2 for 48 h) rats. CoQ1 or its hydroquinone (CoQ1H2) was infused into the arterial inflow of isolated, perfused lungs, and the venous efflux rates of CoQ1H2 and CoQ1 were measured. CoQ1H2 appeared in the venous effluent when CoQ1 was infused, and CoQ1 appeared when CoQ1H2 was infused. In normoxic lungs, CoQ1H2 efflux rates when CoQ1 was infused decreased by 58 and 33% in the presence of rotenone (mitochondrial complex I inhibitor) and dicumarol [NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) inhibitor], respectively. Inhibitor studies also revealed that lung CoQ1H2 oxidation was via mitochondrial complex III. In hyperoxic lungs, CoQ1H2 efflux rates when CoQ1 was infused decreased by 23% compared with normoxic lungs. Based on inhibitor effects and a kinetic model, the effect of hyperoxia could be attributed predominantly to 47% decrease in the capacity of complex I-mediated CoQ1 reduction, with no change in the other redox processes. Complex I activity in lung homogenates was also lower for hyperoxic than for normoxic lungs. These studies reveal that lung complexes I and III and NQO1 play a dominant role in determining the vascular concentration and redox status of CoQ1 during passage through the pulmonary circulation, and that exposure to hyperoxia decreases the overall capacity of the lung to reduce CoQ1 to CoQ1H2 due to a depression in complex I activity.

Keywords: mathematical modeling, NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase, NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1, ubiquinol-cytochrome-c oxidoreductase

the lung is well suited for influencing the chemical composition of the blood as it passes from the venous to the systemic arterial circulation. The nonrespiratory or metabolic functions of the lung are affected by various lung cell surface and intracellular enzymes and transporters that act on blood-borne compounds and are furthered by the large pulmonary endothelial surface area and the fact that the lung receives the entire venous return (28). Among the classes of compounds affected are blood-borne redox active pharmacological, physiological, and toxic compounds (e.g., quinones), whose redox status and concentrations in the blood may be influenced by lung cell surface or intracellular oxidoreductases (2–5, 9, 10, 16, 17, 27, 28, 47, 49–51). Thus the lung has the potential to influence the bioavailability and bioactivity of such compounds in lung tissue, blood vessels, and downstream organs.

Indicator dilution methods have been important research tools for studying metabolic functions of various intact organs, including the lung (2, 5, 12, 28, 55, 63). These methods involve the bolus injection or finite pulse infusion of two or more indicators into the arterial inlet to an organ, followed by measurement of concentrations of these indicators in the venous effluent as a function of time. The injected indicators usually include an intravascular indicator (also known as vascular reference indicator) plus a test indicator that is a substrate or ligand for the organ's metabolic function(s) of interest. The interactions of the test indicator with these metabolic function(s) on passage though the organ result in characteristic differences between the vascular and test indicator venous effluent concentration vs. time curves. The information in these curves is deciphered using mathematical models representing the dominant physical and chemical processes hypothesized to be involved in the disposition of the test indicator within the organ (2, 5, 12, 28, 55, 63).

We have used indicator dilution methods and mathematical modeling to probe the activities of redox enzymes in the isolated, perfused lung and to evaluate the impact of these enzymes on the redox status and disposition of blood-borne redox active compounds on passage through the lung (2–5, 9, 27). For instance, we have observed that the redox active quinone compound duroquinone (DQ) is reduced to durohydroquinone (DQH2) on passage through the pulmonary circulation of the isolated, perfused rat lung, wherein DQH2 appears in the venous effluent. Based on inhibitor studies, NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) was implicated as the dominant reductase involved, and the capacity of the lung to reduce DQ to DQH2 was shown to be a measure of lung NQO1 activity (2). NQO1, which is predominantly a cytoplasmic enzyme, is of interest because it is a phase II antioxidant enzyme involved in the detoxification of reactive electrophilic metabolites (e.g., quinones, lipid peroxides, organic peroxides) via two-electron reduction (2, 20, 50). As such, NQO1 competes with one-electron quinone reductases (e.g., P-450 reductases, cytochrome c, b5) for reactive electrophilic metabolites and other redox active compounds, thereby limiting redox cycling of these compounds and generation of prooxidant reactive oxygen species (ROS) (14, 20, 25, 31, 40, 56).

As a phase II antioxidant enzyme, NQO1 is induced via the antioxidant response element in response to oxidative or electrophilic stress (3, 14, 20, 25, 31, 40, 47, 56). Accordingly, when rats were exposed to hyperoxia (85% O2 for 21 days) as a model of oxidative stress, lung tissue NQO1 activity and protein levels increased, as did the capacity to reduce DQ to DQH2 in the pulmonary circulation (3). Since this hyperoxic exposure is well known to confer adaptation to the otherwise lethal effects of 100% O2 in rats, the impact on NQO1 is consistent with an adaptive response to oxidative stress (3, 26).

In the present study, we directed our attention to the question of whether homologs of the endogenous quinone, ubiquinone, are reduced on passage through the rat pulmonary circulation and, if so, to evaluate the role of NQO1 and other redox enzymes. Ubiquinone is the quinone electron carrier in the mitochondrial electron transport chain located at the inner mitochondrial membrane and also participates in other redox functions, including as an anti- and prooxidant substance (23). To address this question, we selected the quinone compound 2,3-dimethoxy-5-methyl-6-[3-methyl-2-butenyl]-1,4-benzoquinone (coenzyme Q1; CoQ1) because it is an amphipathic homolog of ubiquinone (30, 35, 48, 53). The relatively high octanol-water partition coefficient (log10 octanol-water partition coefficients >3) and significant water solubility (1.3 mM) of CoQ1 are advantageous for evaluating its redox metabolism during passage through the pulmonary circulation using indicator dilution methods (30, 35, 53). Moreover, CoQ1 has been used as an electron acceptor to study not only NQO1, but also other oxidoreductases, including NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (mitochondrial electron transport complex I), succinate-ubiquinone reductase (mitochondrial electron transport complex II), and transplasma membrane electron transport, in isolated enzymes, subcellular fractions, and intact cells in culture (30, 34, 46, 48, 57, 62).

The objective of the present study was to utilize indicator dilution methods to determine whether CoQ1 is reduced on passage through the isolated, perfused rat lung and, if so, to identify and quantify the dominant redox processes that contribute to lung CoQ1 redox metabolism. The potential contribution of multiple redox enzymes to the redox metabolism of CoQ1 on passage through the pulmonary circulation was addressed using inhibitors and kinetic modeling, the latter of which allowed us to quantify the contributions of these enzymes. A further objective was to evaluate the impact of oxidative stress (in vivo exposure to 85% O2 for 48 h) on lung CoQ1 redox metabolism.

Glossary

- BSA

Bovine serum albumin

- CoQ1

Coenzyme Q1

- CoQ1H2

CoQ1 hydroquinone

- [CoQ1](x, t), and [CoQ1H2](x, t)

Vascular concentrations of free CoQ1 and CoQ1H2, respectively, at distance x from the capillary inlet and time t (μM)

- [

]

] Total (free + BSA bound) vascular concentration of CoQ1 (μM)

- [

]

] Total (free + BSA bound) vascular concentration of CoQ1H2 (μM)

- CV

Asymptotic coefficient of variation (%)

- DQ

Duroquinone

- DQH2

Durohydroquinone

- hc(t)

Capillary transit time distribution

- FAPGG

N-[3-(2-Furyl) acryloyl]-Phe-Gly-Gly

- FITC-dex

Fluorescein isothiocyanate dextran

- [FITC-dex](x, t)

Vascular concentration of FITC-dex at distance x from the capillary inlet and time t (μM)

- Km1a

Apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for complex I-mediated CoQ1 reduction (μM)

- Km2a

Apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for NQO1-mediated CoQ1 reduction (μM)

- Km3a

Apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s)-mediated CoQ1 reduction (μM)

- Km4a

Apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for CoQ1H2 oxidation via complex III (μM)

- NQO1

NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1

- PAEC

Bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells

- PS

Permeability-surface area product (ml/min), which is a measure of plasmatic clearance of FAPGG and an index of perfused capillary surface area

- Vc

Volume of the vascular region of the single capillary element model (ml)

- Ve

Volume of the tissue or extravascular region of the single capillary element model (ml)

- Vmax1

Maximum rate for CoQ1 reduction via complex I (μmol/min)

- Vmax2

Maximum rate for CoQ1 reduction via NQO1 (μmol/min)

- Vmax3

Maximum rate for CoQ1 reduction via rotenone-dicumarol insensitive reductase(s) (μmol/min)

- Vmax4

Maximum rate for CoQ1H2 oxidation via complex III (μmol/min)

- VF1/α1

Virtual volume of distribution for CoQ1 (ml)

- VF2/α2

Virtual volume of distribution for CoQ1H2 (ml)

- W

Convective transport velocity (cm/min)

Greek Letters

- α1 and α2

Constants that account for the rapidly equilibrating interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 with the 5% BSA (i.e., Pc) perfusate

- α3 and α4

Constants that account for the rapidly equilibrating interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 with lung tissue sites (Pe) of association, respectively

METHODS

Materials.

CoQ1 and other chemicals, unless noted, were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). CoQ1H2 was prepared by reduction of CoQ1 with potassium borohydride (KBH4), as previously described (3). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was purchased from Serologicals (Gaithersburg, MD).

Animals.

For normoxic lung studies, adult Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River) were exposed to room air with free access to food and water. For the hyperoxic lung studies, weight-matched rats were housed in a sealed Plexiglas chamber (13 in. width × 23 in. length × 12 in. height) maintained at ∼85% O2-balance N2 for 48 h with free access to food and water, as previously described (3). The total gas flow was ∼3.5 l/min, and the chamber CO2 was <0.5%. The protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and Marquette University (Milwaukee, WI). A total of 43 normoxic rats and 40 hyperoxic rats were studied.

Isolated, perfused lung experiments.

As previously described, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital sodium (40 mg/kg body wt ip), the trachea was clamped, the chest opened, and heparin (0.7 IU/g body wt) injected into the right ventricle. The pulmonary artery and the trachea were cannulated, and the pulmonary venous outflow was accessed via a cannula in the left atrium. The lung was removed from the chest and attached to a ventilation and perfusion system. The control perfusate contained (in mM) 4.7 KCl, 2.51 CaCl2, 1.19 MgSO4, 2.5 KH2PO4, 118 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 5.5 glucose, and 5% BSA (2). The single-pass perfusion system was primed (Masterflex roller pump) with the control perfusate maintained at 37°C and equilibrated with 15% O2-6% CO2-balance N2, resulting in perfusate Po2, Pco2, and pH of ∼105 Torr, 40 Torr, and 7.4, respectively. Initially, control perfusate was pumped (Masterflex roller pump) through the lung until the lung was evenly blanched, and venous effluent was clear of blood by visual inspection. The lung was ventilated (40 breaths/min) with end-inspiratory and end-expiratory pressures of ∼6 and 3 mmHg, respectively, with the above gas mixture. The pulmonary arterial pressure was referenced to atmospheric pressure at the level of the left atrium and monitored continuously during the course of the experiments. The venous effluent pressure was atmospheric pressure. At the end of each experiment, the lung was weighed and then dried (60°C) to a constant weight for the determination of lung dry weight.

Experimental protocols.

To evaluate the disposition of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 during passage through the lung, pulse infusion and bolus injection indicator dilution experiments were carried out. Pulse infusion experiments were carried out to provide data about the capacity of the lung to reduce CoQ1 and to oxidize CoQ1H2 and the contributions of various oxidoreductases. The bolus injection experiments were carried out to provide data in which transient information about CoQ1H2 disposition on passage through the lung is emphasized, thus providing insights into the tissue permeation of CoQ1H2. What follows is a description of the main pulse infusion and bolus injection experimental protocols.

To determine the infusion time needed for CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 in the venous effluent to reach steady state during CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 arterial infusion, 30-s pulse infusions containing either 100 μM CoQ1, 100 μM CoQ1H2, or 4.6 μM of the vascular indicator fluorescein isothiocyanate dextran (FITC-dex; average molecular wt ∼43,200) were carried out in one normoxic lung at a flow of 30 ml/min. Venous effluent samples (∼0.5 ml) were collected at 5-s intervals over the 30-s infusion period.

To determine the capacity of the lung to reduce CoQ1, each lung received four successive 30-s CoQ1 pulse infusions at concentrations of 50, 100, 200, and 400 μM at a flow of 30 ml/min. Two venous effluent samples (∼0.5 ml) were collected between 25 and 30 s after the initiation of each pulse infusion. This protocol was carried out in six normoxic and seven hyperoxic lungs.

To determine the redox processes that contribute to CoQ1 reduction on passage through the pulmonary circulation, each lung was perfused for 5 min with perfusate containing the complex I inhibitor rotenone (20 μM) or the NQO1 inhibitor dicumarol (400 μM) (3), or a combination of the two (rotenone plus dicumarol). This was followed by four successive CoQ1 pulse infusions, as above, where the inhibitors were also present throughout the infusion protocol. Two venous effluent samples (∼0.5 ml) were collected between 25 and 30 s after the initiation of each pulse infusion. The number of normoxic lungs perfused with perfusate containing rotenone, or dicumarol, or both were 4, 5, and 5, respectively, for a total of 13 lungs. For the same sequence of inhibitors, the number of hyperoxic lungs studied were 4, 5, and 4, respectively, for a total of 13 lungs.

To evaluate the capacity of the lung to oxidize CoQ1H2, each lung was perfused for 5 min with perfusate containing rotenone (20 μM) and dicumarol (400 μM) to minimize CoQ1 reduction, followed by four successive CoQ1H2 pulse infusions at concentrations of 50, 100, 200, and 400 μM at a flow of 30 ml/min. The inhibitors were present throughout this infusion protocol. Four normoxic and four hyperoxic lungs were studied using this protocol. In four of these lungs (two normoxic and two hyperoxic), an additional 200 μM CoQ1H2 pulse infusion was carried out in the presence of cyanide (KCN) (2 mM, complex IV inhibitor) in addition to dicumarol and rotenone. This pulse infusion was carried out to evaluate the contribution of mitochondrial electron transport complex III to CoQ1H2 oxidation on passage through the lung. Two venous effluent samples (∼0.5 ml) were collected between 25 and 30 s after the initiation of each pulse infusion.

To evaluate the accessibility of CoQ1H2 to lung tissue on passage through the pulmonary circulation, bolus injection experiments were carried out in one normoxic and one hyperoxic lung. Each lung was first perfused with cyanide (2 mM) containing perfusate for 5 min, after which the respirator was stopped at end expiration, and a 0.1 ml bolus of perfusate containing cyanide and either 400 μM CoQ1H2 or 35 μM FITC-dex was injected into the pulmonary arterial inflow tubing. At the same time that the bolus was injected, the venous effluent was diverted into a fraction collector for continuous collection of the lung effluent at a rate and duration depending on the perfusate flow (2). The FITC-dex and CoQ1H2 bolus injections were repeated with the flow set to 10 and 30 ml/min.

To determine the tubing transit time of the perfusion system, at the end of the above bolus injection protocol the lung was removed from the perfusion system, the arterial and venous cannulas were connected, and two FITC-dex (35 μM) bolus injections were carried out at 10 and 30 ml/min.

To determine the perfused lung surface area, a 150 μM 20-s pulse infusion of the angiotensin-converting enzyme substrate N-[3-(2-furyl) acryloyl]-Phe-Gly-Gly (FAPGG) was introduced into the lung with the flow set at 30 ml/min (3). Two venous effluent samples (∼1.0 ml each) were collected between 15 and 20 s after the start of the infusion (3). This FAPGG pulse infusion was carried out at the beginning of each of the above experimental protocols in normoxic and hyperoxic lungs.

Determination of CoQ1, CoQ1H2, and FITC-dex in venous effluent samples.

Venous effluent samples were first centrifuged (1 min at 5,600 g). For each sample, 100 μl of supernatant were then added to each of two centrifuge tubes: one containing 10 μl potassium ferricyanide (12.1 mM in deionized H2O) to oxidize any CoQ1H2 to CoQ1, and the other containing 10 μl EDTA (1 mM in deionized H2O) to minimize autooxidation of CoQ1H2. Ice-cold absolute ethanol (0.4–0.8 ml) was added, and the tubes were mixed on a vortex mixer followed by centrifugation at 9,300 g for 5 min at 4°C. A perfusate sample that had passed through the lungs but contained no CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 was treated in the same manner to be used as the blank for absorbance measurements. The absorbances were measured at 275 nm using a Beckman DU 7400 spectrophotometer. Sample concentrations of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 (in μM) were calculated from the absorbance values of the fully oxidized (following the addition of ferricyanide) (Abs1) and the EDTA-treated (Abs2) supernatant in the tubes using extinction coefficients at 275 nm of 14.30 mM−1·cm−1 for CoQ1 and 2.29 mM−1·cm−1 for CoQ1H2 (41, 57) as follows

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

where [CoQ1] and [CoQ1H2] are the concentrations of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 sample concentrations, respectively.

For a given venous sample, [CoQ1] and [CoQ1H2] are given by Eq. 3, which is the solution of Eqs. 1 and 2:

|

(3) |

FITC-dex concentrations were determined from the absorbance at 495 nm using a molar extinction coefficient of 93.5 mM−·cm−1 (2, 3).

Determination of perfused capillary surface area.

The permeability-surface area product (PS, ml/min) for FAPGG was determined from the FAPGG concentrations measured in the venous effluent samples, as previously described (3):

|

(4) |

where E = steady state extraction ratio = 1 − [FAPGG]o/[FAPGG]i; [FAPGG]i is the infused arterial FAPGG concentration; [FAPGG]o is the steady-state venous effluent FAPGG concentration calculated as the average [FAPGG] in the collected venous effluent samples, and F is the perfusate flow (3). The PS product is a measure of plasmatic clearance of FAPGG and is considered here as an index of perfused capillary surface area (3).

Lung oxygen consumption.

Rats were anesthetized as described above and allowed to breathe 100% O2 for 5 min (2). The trachea was then clamped before the chest was opened. This resulted in the absorption of all alveolar gas and the collapse of the lung (i.e., atelectatic lung). The atelectatic lung was then removed from the chest and connected to the perfusion system supported by the tracheal, arterial, and venous cannulas, but was otherwise not ventilated. Thus the only source of oxygen for the lung was the perfusate, which was Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) containing 10 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.4), 5.5 mM glucose, and 5% BSA (HBSS/HEPES) equilibrated with room air (2). After the lung was cleared of blood, the perfusate Po2 was raised to slightly higher than atmospheric O2 (∼160 Torr) by bubbling the reservoir perfusate with O2. The venous cannula was connected to a stirred reservoir, thereby forming a recirculating perfusion system containing a total of ∼30 ml of perfusate, including the lung vascular volume. The reservoir Po2 was monitored (YSI 5300 Biological Oxygen Monitor) until it had fallen to ∼60 Torr. The resulting reservoir Po2 vs. time data was used to calculate lung O2 consumption rate (μmol·min−1·g dry lung wt−1) (2).

Complex I and IV assays.

The lungs were washed free of blood with perfusate containing 2.5% Ficoll instead of 5% BSA. The lungs were then weighed, minced, and homogenized on ice in five volumes (wt/vol) of ice-cold buffer (pH 7.2) containing 225 mM mannitol, 75 mM sucrose, 5 mM 3-[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid, 20 mM ethylene glycol-bis(B-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid, 2% fatty acid free BSA, and 0.02 ml/ml protease inhibitor cocktail set III (Calbiochem, La Jolla, CA), utilizing a Polytron tissue homogenizer (Kinematica, Luzern, Switzerland). Lung homogenates were centrifuged at 1,500 g for 5 min at 4°C, and the resulting supernatants were centrifuged again at 13,000 g for 30 min at 4°C to obtain a crude mitochondrial fraction (P2). The P2 fractions were washed twice by resuspension in 8-ml ice-cold homogenization buffer without BSA and then centrifuged (13,000 g for 20 min at 4°C). The final P2 fractions were resuspended in 1-ml BSA-free homogenization buffer and stored at −80°C. The protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), using BSA as the standard.

Complex I activity was measured using the method of Lenaz et al. (46). The assay buffer (pH 7.4) contained 10 mM tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane hydrochloride (Tris·HCl), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM KCN, 2 μM antimycin A, 50 μM CoQ1, and 100 μM NADH without and with 2 μM rotenone. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 0.05 ml thawed P2 fraction, containing ∼0.2 mg protein, to 2-ml assay buffer in a spectrophotometric cuvette at 27°C. NADH oxidation was monitored as the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm, and NADH concentrations were calculated from the recorded absorbance values using an extinction coefficient of 6.22 mM−1·cm−1. Complex I activity (nmol NADH oxidized·min−1·mg protein−1) was determined as the difference between the rates of NADH oxidation in the presence and absence of rotenone over the linear portion of the reaction progress curve. Mitochondrial complex IV (cytochrome-c oxidase) activity was measured as described by Storrie and Madden using ferrocytochrome c as the substrate (58).

Additional studies.

CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 (50–400 μM) binding to BSA was determined as previously described (2). At 5% BSA, 93.1 ± 0.3% (SE, n = 4) of the CoQ1 and 93.9 ± 0.5% of the CoQ1H2 were BSA bound, and the bound fractions were independent of the CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 concentrations over the concentration range studied.

Statistical evaluation of data.

Statistical comparisons were carried out using unpaired t-test or ANOVA followed by Tukey's test, with P < 0.05 as the criterion for statistical significance. The likelihood ratio test (39) was used to determine the significance of differences in estimated values of model parameters between normoxic and hyperoxic lungs.

RESULTS

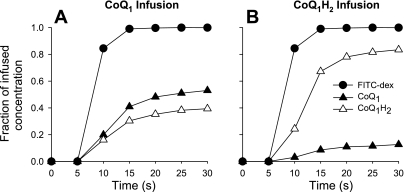

Figure 1 shows the venous effluent concentrations of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2, represented as fractions of the infused concentration of CoQ1 (Fig. 1A) or CoQ1H2 (Fig. 1B) in a normoxic lung. Also shown are the venous effluent FITC-dex concentrations as fractions of the infused FITC-dex concentration. Since FITC-dex is an intravascular indicator that is not otherwise metabolized or taken up by the lung, the FITC-dex fractional concentration vs. time curves represents what the CoQ1 (Fig. 1A) and CoQ1H2 (Fig. 1B) curves would have looked like, if the only effect of passage through the lung were convection (2, 3). The fact that the CoQ1 (Fig. 1A) and CoQ1H2 (Fig. 1B) curves deviate from that for FITC-dex suggests that processes in addition to convection, e.g., CoQ1 reduction and CoQ1H2 oxidation, are taking place on passage through the lung.

Fig. 1.

Venous effluent FITC-dex, CoQ1, and CoQ1H2 concentrations as fractions of the infused FITC-dex (A and B) CoQ1 (A), and CoQ1H2 (B), respectively, during a pulse infusion of 4.6 μM FITC-dex (A and B), 100 μM CoQ1 (A), or 100 μM CoQ1H2 (B) into the pulmonary arterial inflow of one normoxic lung at a flow of 30 ml/min. See Glossary for definition of acronyms.

Regardless of whether CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 was infused, the fractional concentrations of CoQ1, CoQ1H2, and FITC-dex all approached steady state by ∼25 s (Fig. 1). At steady state, ∼93 and 96% of the infused CoQ1 (Fig. 1A) and CoQ1H2 (Fig. 1B), respectively, were recovered in the venous effluent as CoQ1 + CoQ1H2, with the loss attributable primarily to binding of both forms to the experimental tubing (data not shown). At steady state, ∼40% of the infused CoQ1 appeared as CoQ1H2, in the venous effluent (Fig. 1A), and ∼13% of the infused CoQ1H2 appeared as CoQ1 (Fig. 1B). In subsequent pulse infusion studies, the steady-state data were used to calculate steady-state CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 efflux rates, calculated as the product of the perfusate flow and the steady-state CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 concentrations, respectively, in venous samples collected between 25 and 30 s.

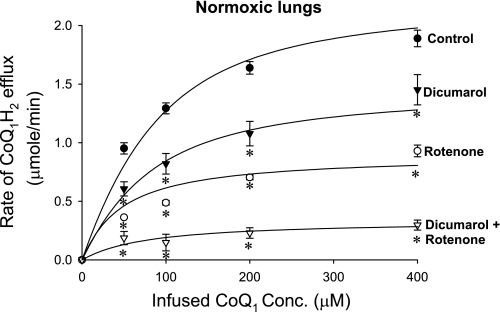

To evaluate the processes contributing to CoQ1 reduction in the lung, the steady-state CoQ1H2 efflux rates were measured over a range of infused CoQ1 concentrations in normoxic lungs in the absence (control) and presence of the complex I inhibitor rotenone, the NQO1 inhibitor dicumarol, and the combination of the two (Fig. 2). The steady-state CoQ1H2 efflux rates increased over the concentration range studied and approached saturation at the highest CoQ1 concentration. Figure 2 also shows that the steady-state CoQ1H2 efflux rates decreased by ∼58 and 33% in the presence of rotenone and dicumarol, respectively, and by ∼85% in the presence of both inhibitors, suggesting a dominant role for complex I and NQO1 in CoQ1 reduction on passage through the lung. The data also reveal the contribution of a rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s) to CoQ1 reduction on passage through the lung.

Fig. 2.

The relationship between the steady-state rate of CoQ1H2 efflux and the infused CoQ1 concentrations for normoxic lungs in the absence (control) or presence of rotenone, dicumarol, or dicumarol plus rotenone. Values are means ± SE; n = 6, 5, 4, and 4 for control, dicumarol, rotenone, and dicumarol plus rotenone, respectively, for a total of 19 normoxic lungs. The solid lines are model fits to the mean values of the data. *Significantly different from the control rates at the same infused CoQ1 concentrations, P < 0.05.

The rotenone concentration (20 μM) used to inhibit complex I-mediated CoQ1 reduction is a saturating concentration based on the results of a rotenone dose-response experiment (data not shown), which showed no additional inhibition of the steady-state rate of CoQ1H2 efflux during CoQ1 (200 μM) infusion in a normoxic lung for rotenone concentrations >20 μM. The concentrations of dicumarol (400 μM) and cyanide (2 mM) used were also saturating based on the results of previous studies (2, 3).

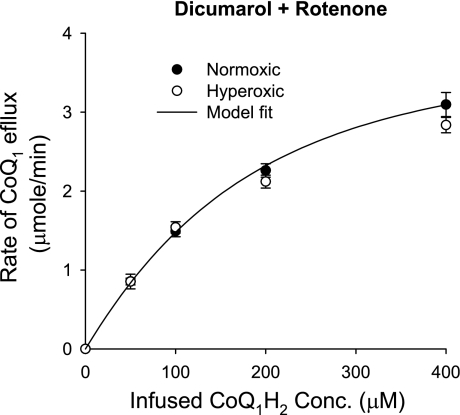

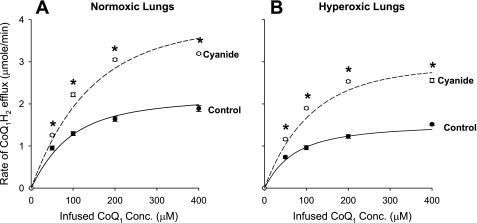

To evaluate the capacity of the lung to oxidize CoQ1H2, the steady-state CoQ1 efflux rates were measured during the infusion of CoQ1H2 over a range of concentrations. For these studies, CoQ1 reduction was minimized by including dicumarol and rotenone in the perfusate. The steady-state CoQ1 efflux rates increased over the range of CoQ1H2 concentrations studied, with no detectable difference between normoxic and hyperoxic lungs (Fig. 3). In the presence of cyanide, the steady-state CoQ1 efflux rate dropped to nearly zero (data not shown), suggesting that CoQ1H2 oxidation on passage through normoxic and hyperoxic lungs occurs predominantly via the hydroquinone oxidase-cytochrome c reductase activity of complex III.

Fig. 3.

The relationship between the steady-state rate of CoQ1 efflux and the infused CoQ1H2 concentration for normoxic (n = 4) and hyperoxic (n = 4) lungs in the presence of dicmuarol plus rotenone. Values are means ± SE. The solid line is the model fit to the mean values of the normoxic data.

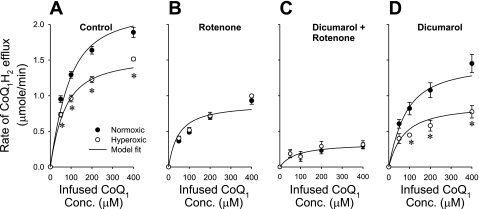

Exposure to hyperoxia had a significant effect on the capacity of the lung to reduce CoQ1. The steady-state CoQ1H2 efflux rates over the range of CoQ1 concentrations studied were ∼23% lower in hyperoxic than in normoxic lungs (Fig. 4A). This decrease can be almost completely eliminated with rotenone (Fig. 4B) or rotenone plus dicumarol (Fig. 4C), but not with dicumarol alone (Fig. 4D), suggesting a decreased contribution of the complex I-mediated component of CoQ1 reduction in hyperoxic lungs. On the other hand, the contributions of the dicumarol (NQO1)-sensitive component (Fig. 4, B and C) and the rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive component (Fig. 4C) appeared to be unaffected by hyperoxia. Figure 4 also indicates that complex I and NQO1 are the dominant CoQ1 reductases on passage through hyperoxic as well as normoxic lungs.

Fig. 4.

The relationship between the steady-state rate of CoQ1H2 efflux and the CoQ1 infusion concentration for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs in the absence (control) (A), or in the presence of the complex I inhibitor rotenone (B), rotenone plus the NQO1 inhibitor dicumarol (C), or dicumarol alone (D). The normoxic lung data are the same as those in Fig. 2. Values are means ± SE. For normoxic lungs, n = 6 (A), 4 (B), 4 (C), and 5 (D) for a total of 19 lungs. For hyperoxic lungs, n = 7 (A), 4 (B), 5 (C), and 4 (D) for a total of 20 lungs. *Significantly different from the values for the normoxic lungs at the same infused CoQ1 concentrations, P < 0.05. The solid lines are model fits to the mean values of the data.

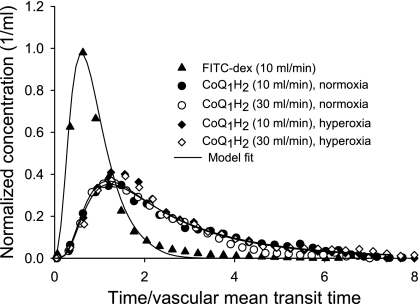

Bolus injection experiments were used to evaluate the accessibility of CoQ1H2 to lung tissue from the vasculature. Figure 5 shows concentration vs. time outflow curves for CoQ1H2 and FITC-dex following arterial bolus injections of CoQ1H2 and FITC-dex in one normoxic lung and one hyperoxic lung at flows of 10 and 30 ml/min. The studies were carried out in the presence of cyanide to block CoQ1H2 oxidation. Virtually all of the injected CoQ1H2 was recovered as CoQ1H2 in the venous effluent in normoxic and hyperoxic lungs at both flows. The observation that the CoQ1H2 outflow curves at two different flows (10 and 30 ml/min) were virtually superimposable when the time axis for each curve was normalized to vascular mean transit time is a hallmark of a substance that freely permeates tissues (i.e., “flow limited”) (2, 3, 6, 8). Figure 5 also shows that the normalized outflow curves for CoQ1H2 for the normoxic and hyperoxic lung were similar, implying that CoQ1H2 accesses equivalent tissue volumes from the vascular region of normoxic and hyperoxic lungs. We were unable to carry out such bolus injection studies for CoQ1 because of the high dicumarol concentration (400 μM) required to inhibit NQO1 in the presence of an albumin-containing medium (3). This dicumarol concentration would interfere with spectrophotometric measurements of CoQ1 at the low CoQ1 concentrations (<5 μM) that are present in effluent samples in the early rising portion and the tail of the CoQ1 concentration vs. time outflow curve following CoQ1 bolus injection. Additionally, we were unable to inhibit the unidentified rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s) contributing to CoQ1 reduction.

Fig. 5.

Venous effluent FITC-dex or CoQ1H2 as a fraction of the total injected amounts of each per milliliter of effluent perfusate vs. time following bolus injections of FITC-dex (35 μM) or CoQ1H2 (400 μM), respectively, in one normoxic lung and one hyperoxic lung. Cyanide was present in the perfusate to block CoQ1H2 oxidation, and the perfusate flow was set at either 10 or 30 ml/min. Only one FITC-dex curve (10 ml/min, normoxic lung) is shown, since they were virtually superimposable for the normoxic and hyperoxic lung at both flows. The time scale was obtained by subtracting tubing mean transit time from each sample time and then normalizing the values to the FITC-dex lung mean transit time (vascular mean transit time). Solid lines are model fits to data.

Because the data in Fig. 4 suggested that the hyperoxic exposure decreased the complex I-mediated CoQ1 reduction, complex I activity was measured in the P2 fractions obtained from lung homogenates. Table 1 shows that complex I activity normalized to protein was ∼48% lower in P2 fractions derived from hyperoxic than normoxic lungs. There was no significant difference between normoxic and hyperoxic lungs with respect to mitochondrial electron-transport complex IV activity or whole lung O2 consumption rate (Table 1). The latter is an approximation of the total steady-state consumption rate of reducing equivalent by the entire lung (2).

Table 1.

Mitochondrial complex I and IV activities measured in P2 fractions of lung homogenates and whole lung oxygen consumption rate

| Complex I Activity, nmol·min−1·mg protein−1 | Complex IV Activity, nmol·min−1·mg protein−1 | Lung O2 Consumption, μmol·min−1·g dry lung wt−1 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxic | 11.89±1.05 | 121.29±22.34 | 3.44±0.11 |

| Hyperoxic | 6.25±1.01* | 135.02±24.99 | 2.80±0.48 |

Values are means ± SE. For complexes I and IV activities, n = 9 and 7 for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs, respectively. For lung O2 consumption rate, n = 4 and 4 for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs, respectively.

Significantly different from the corresponding normoxic value, P < 0.05.

Table 2 shows that lung perfusion pressure, wet weight, wet-to-dry weight ratio, and perfused capillary surface area were not significantly different between normoxic and hyperoxic lungs, consistent with previous studies (2, 3, 15, 26).

Table 2.

Rat body weights, lung perfusion pressures, lung weights, lung wet-to-dry ratio, and angiotensin-converting enzyme activity

| Body Weight, g | Pa, Torr | Wet Weight, g | Wet-to-Dry Ratio | PS, ml/min | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normoxic | 316±5 | 9.8±0.2 | 1.28±0.03 | 5.6±0.1 | 23.1±0.8 |

| Hyperoxic | 311±3 | 9.4±0.3 | 1.34±0.04 | 5.8±0.1 | 24.5±0.7 |

Values are mean ± SE. For normoxic lungs, n = 43, 34, 43, 30, and 28 for body weight, Pa, lung wet weight, wet-to-dry ratio, and PS, respectively, where 43 is the total number of normoxic lungs studied. For hyperoxic lungs, n = 40, 34, 39, 31, and 30, respectively, where 40 is the total number of hyperoxic lung studied. Pa, lung perfusion pressure with perfusate flow set at 30 ml/min; PS (permeability surface area product), measure of plasmatic clearance of N-[3-(2-furyl) acryloyl]-Phe-Gly-Gly and an index of perfused capillary surface area.

Data analysis.

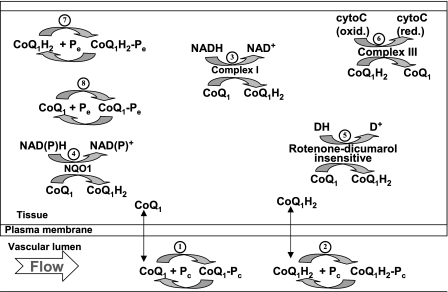

The data in Figs. 1–5 are the net result of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 interactions with competing nonlinear tissue redox processes, CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 interactions with BSA in the vascular space, and capillary perfusion kinematics [i.e., capillary transit time distribution, hc(t)]. The latter affects the efficiency of the lung in reducing CoQ1 and oxidizing CoQ1H2 on passage through the pulmonary circulation. For instance, the longer the capillary mean transit time, the more time available for CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 interactions with lung tissue redox processes. Furthermore, the overall rate of such interactions is inversely related to the heterogeneity of hc(t) (2, 7). Thus proper quantitative interpretation of the data in Figs. 1–5 requires a means for accounting for CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 tissue and vascular interactions, as well as perfusion kinematics. To this end, we developed a kinetic model that expresses our hypotheses regarding the dominant processes that determine the fates of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 on passage through the pulmonary circulation. Figure 6 presents a schematic of a single capillary element of the kinetic model, consisting of a capillary vascular volume and its surrounding tissue volume. The free concentrations of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 (i.e., not BSA bound) are allowed to have freely permeating (i.e., “flow-limited”) access to tissue volume from the vascular region. For CoQ1H2, this assumption is based on the bolus injection data in Fig. 5. For CoQ1, it is based on its amphipathic nature. Like CoQ1H2 and DQ, which is also a flow-limited quinone compound, CoQ1 has a high octanol-water partition coefficient (log10 octanol-water partition coefficients >3 for both CoQ1 and CoQ1H2, and log10 cyclohexane-water partition coefficient of 2.45 for DQ), along with a significant water solubility (1.3 and 1.5 mM for CoQ1 and DQ) (30, 35, 53).

Fig. 6.

A schematic representation of the hypothesized vascular and lung tissue interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 in a single capillary element consisting of a vascular region and its surrounding tissue region. Within the vascular region, CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 participate in nonspecific and rapidly equilibrating interactions with the perfusate BSA, Pc (processes 1 and 2). Within the tissue region, CoQ1 is reduced via complex I (process 3), NQO1 (process 4), and otherwise unidentified rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s) (process 5), and CoQ1H2 is oxidized via complex III (process 6). Also, within the tissue volume, CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 undergo nonspecific rapidly equilibrating interactions with lung tissue sites (Pe) of association (processes 7 and 8). CytoC (oxid.) and cytoC (red.) are the oxidized and reduced forms of cytochrome c, respectively. DH and D+ represent the reduced and oxidized forms of electron donors for the unknown rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive CoQ1 reductase(s), respectively.

Within the vascular volume of the kinetic model, CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 participate in nonspecific and rapidly equilibrating interactions with the perfusate albumin, Pc (processes 1 and 2). Within the tissue volume, CoQ1 is reduced via complex I (process 3), NQO1 (process 4), and otherwise unidentified rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s) (process 5), and CoQ1H2 is oxidized via complex III (process 6). Also, within the tissue volume, CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 undergo nonspecific, rapidly equilibrating interactions with lung tissue sites (Pe) of association (processes 7 and 8). CoQ1 reduction and CoQ1H2 oxidation are assumed to follow Michaelis-Menten kinetics, with Vmax and Km representing the maximum reduction or oxidation rate and Michaelis-Menten constant, respectively. All nonspecific CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 interactions are assumed to follow the law of mass action.

The governing differential equations of the single capillary element model (see appendix) are the basis of the whole organ model, which accounts for the distribution of pulmonary capillary transit times, hc(t), as described in the appendix. The hc(t) was previously determined for the normoxic rat lung (2) and is assumed to be unaffected by exposure to 85% O2 for 48 h. This is based on the results in Table 1, which show that exposure to hyperoxia had no significant effect on perfused lung capillary surface area (PS), and on results from a previous study in which our laboratory demonstrated that lung vascular volume and vascular transit time distribution were not significantly different between normoxic and hyperoxic (85% O2 for 48 h) rat lungs (3). Additionally, Block and Fisher (15) showed that rat exposure to hyperoxia (100% O2 for 48 h) had no significant effect on lung vascular flow distribution.

The kinetic model parameters are Vmax1, Vmax2, and Vmax3, which are the maximum rates (μmol/min) for CoQ1 reduction via complex I, NQO1, and rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s), respectively; Km1a, Km2a, and Km3a (μM), the apparent Michaelis-Menten constants (μM) for complex I, NQO1, and rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s) mediated CoQ1 reduction, respectively (3); Vmax4 (μmol/min) and Km4a (μM), the maximum rate and apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for CoQ1H2 oxidation via complex III, respectively; VF1/α1 (ml) and VF2/α2 (ml), the respective virtual tissue volumes of distribution accessible to CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 from the vascular region (see Glossary). The constants α1 = 14.6 and α2 = 16.5 account for the rapidly equilibrating interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 with the 5% BSA (i.e., Pc) perfusate calculated from the fractions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 bound to BSA obtained by ultrafiltration.

The governing differential equations (see appendix) show that the steady-state concentrations of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 during CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 infusion are independent of the values of VF1/α1 and VF2/α2. Hence, the relevant kinetic model parameters under steady-state conditions during pulse infusion of CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 are Vmax1, Vmax2, Vmax3, Vmax4, Km1a, Km2a, Km3a, and Km4a.

Estimation of kinetic model parameters descriptive of the various oxidoreductases.

As described below, model parameters descriptive of the various oxidoreductases were estimated by fitting the model solution simultaneously to averaged pulse infusion data from multiple lungs (Figs. 2–4). This approach was chosen since data from multiple experimental protocols are needed to estimate these model parameters, and since it is not practical to carry out multiple protocols in the same lung. We have used this approach previously, and it is similar to the simultaneous nonlinear regression approach used by others (2, 50, 61).

For the data in Figs. 3 and 4C, complex I and NQO1 were inhibited by rotenone and dicumarol, respectively. Thus parameters descriptive of CoQ1 reduction via rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reducatase(s) (Vmax3 and Km3a) and CoQ1H2 oxidation via complex III (Vmax4 and Km4a) were estimated by fitting the steady-state solution of the organ model (appendix) simultaneously to the mean values of the normoxic data in Figs. 3 and 4C. Inhibition of complex I and NQO1-mediated components of CoQ1 reduction were simulated by setting the values of Vmax1 and Vmax2 to zero. The estimated values of Vmax3, Km3a, Vmax4, and Km4a are shown in Table 3. Also shown inTable 3 are the asymptotic coefficients of variation (CVs) of these estimates and correlation coefficients between these parameters, which were determined as previously described (5, 44). Since Figs. 3 and 4C show no significant differences between normoxic and hyperoxic data in the presence of dicumarol plus rotenone, the values of Vmax3, Km3a, Vmax4, and Km4a for hyperoxic lungs were set to those estimated for normoxic lungs (Table 3).

Table 3.

Estimated values of the kinetic parameters descriptive of rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive CoQ1 reduction and CoQ1H2 oxidation on passage through normoxic lungs, a measure of the relative precision of estimates of these parameters, and correlation coefficients between these parameters

| Parameters | Estimated Values | CV, % | Correlation Matrix | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax3, μmol/min | 0.86 | 20.1 | 1 | 0.76 | −0.06 | 0.16 |

| Km3a, μM | 65.6 | 77.4 | 1 | −0.08 | 0.56 | |

| Vmax4, μmol/min | 4.6 | 3.2 | 1 | 0.60 | ||

| Km4a, μM | 75.9 | 14.5 | 1 | |||

Vmax3 and Km3a are the respective maximum rate and apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for coenzyme Q1 (CoQ1) reduction via rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s); Vmax4 and Km4a are the respective maximum rate and apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for CoQ1 hydroquinone (CoQ1H2) oxidation via complex III. Parameter values were estimated from the mean values of the normoxic data in Figs. 3 and 4C. The values of Vmax3, Km3a, Vmax4, and Km3a for hyperoxic lungs are assumed to be the same as those estimated for normoxic lungs. CV, asymptotic coefficient of variation.

Knowing Vmax3, Km3a, Vmax4, and Km4a, the model parameters descriptive of complex I-mediated CoQ1 reduction (Vmax1 and Km1a) and NQO1-mediated CoQ1 reduction (Vmax2 and Km2a) in normoxic and hyperoxic lungs were then estimated. This was achieved by fitting the steady-state solution of the organ model (CoQ1H2 efflux rates when CoQ1 was infused) simultaneously to the mean values of the normoxic and hyperoxic data in Fig. 4, A, B, and D, in the absence (control) and presence of rotenone or dicumarol. For this parameter estimation step, Vmax1 was assumed to be the only parameter affected by exposure to hyperoxia. The other parameters, namely Km1a, Vmax2, and Km2a, were assumed to have the same values for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs. The estimated values of Vmax1, Km1a, Vmax2, and Km2a for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs, CVs of these estimates, and correlation coefficients between these parameters are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Estimated values of the kinetic parameters descriptive of rotenone and dicumarol-sensitive CoQ1 reduction on passage through normoxic and hyperoxic lungs, a measure of the relative precision of the estimates of these parameters, and correlation coefficients between these parameters

| Parameters | Estimated Values | CV, % | Correlation Matrix | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vmax1 (normoxic), μmol/min | 2.17 | 8.6 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.83 | −0.53 | −0.50 |

| Vmax1 (hyperoxic), μmol/min | 1.15 * | 12.0 | 1 | 0.61 | 0.52 | −0.38 | |

| Km1a, μM | 33.7 | 42.3 | 1 | −0.40 | −0.56 | ||

| Vmax2, μmol/min | 1.17 | 11.5 | 1 | 0.77 | |||

| Km2a, μM | 13.4 | 93.6 | 1 | ||||

Vmax1 and Km1a are the respective maximum rate and apparent Michaelis-Menten constant for CoQ1 reduction via complex I; Vmax2 and Km2a are the respective maximum rate and apparent Michaelis-Menten constants for NAD(P)H-quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NOQ1)-mediated CoQ1 reduction. Parameter values were estimated from the mean values of the normoxic and hyperoxic data shown in Figure 4, A, B, and D, with Vmax1 as the only parameter affected by exposure to hyperoxia.

Significantly (likelihood ratio test; P < 0.005) different from the corresponding normoxic value.

The asymptotic CV is a measure of the relative precision of the estimate of a given parameter. The CVs for the estimated values of Vmax1 for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs (Table 4) are relatively small, consistent with a significant difference (likelihood ratio test; P < 0.005) between the estimated values of Vmax1 for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs. On the other hand, the CVs for the estimated values of Km2a and Km3a (Tables 3 and 4) are relatively high. One possible reason is that the actual values of these parameters are low relative to the range of CoQ1 concentrations achieved in this study.

Tables 3 and 4 show that the absolute values of the correlation coefficients between the model parameters descriptive of the various oxidoreductases were < 0.85. This suggests that the pulse infusion data (Figs. 2–4) have enough discriminating information about these parameters.

Estimation of the virtual tissue volume (VF2/α2) accessible to CoQ1H2 on passage through normoxic and hyperoxic lungs.

The virtual tissue volume VF2/α2 accessible to CoQ1H2 from the vascular region was calculated as the product of perfusate flow and the difference between the mean transit times of the venous effluent curves of FITC-dex and CoQ1H2 (Fig. 5), estimated as previously described (3). The estimated values of VF2/α2 for the one normoxic lung studied are ∼1.68 and 1.78 ml at 10 and 30 ml/min, respectively. For the one hyperoxic lung studied, the estimated values of VF2/α2 are ∼1.70 and 1.85 ml at 10 and 30 ml/min, respectively. For normoxic and hyperoxic lungs, the value of the tissue volume accessible to CoQ1 from the vascular region, VF1/α1, was set to that estimated for VF2/α2 from the data in Fig. 5. Table 5 provides a summary of the values of all of the kinetic model parameters for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs.

Table 5.

Summary of the values of kinetic model parameters for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs

| Model Processes and Parameters | Normoxic Lungs | Hyperoxic Lungs |

|---|---|---|

| Complex I | ||

| Vmax1, μmol/min | 2.17 | 1.15* |

| Km1a, μM | 33.7 | 33.7 |

| NQO1 | ||

| Vmax2, μmol/min | 1.17 | 1.17 |

| Km2a, μM | 13.4 | 13.4 |

| Rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s) | ||

| Vmax3, μmol/min | 0.86 | 0.86 |

| Km3a, μM | 65.6 | 65.6 |

| Complex III | ||

| Vmax4, μmol/min | 4.6 | 4.6 |

| Km4a, μM | 75.9 | 75.9 |

| Apparent tissue volumes accessible to CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 | ||

| VF1/α1, ml | 1.73 | 1.78 |

| VF2/α2, ml | 1.73 | 1.78 |

The values of Vmax1, Km1a, Vmax2, and Km2a were estimated from the mean values of the normoxic and hyperoxic data shown in Figure 4, A, B, and D, with Vmax1 as the only parameter affected by exposure to hyperoxia. The values of Vmax3, Km3a, Vmax4, and Km4a were estimated from the mean values of the normoxic data in Figure 3 and Figure 4C. For hyperoxic lungs, the values of Vmax4, Km3a, Vmax4, and Km4a were set to those estimated for normoxic lungs. The values of VF2/α2 (virtual volume of distribution for CoQ1H2) for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs were estimated from the data in Figure 5. The values of VF1/α1 (virtual volume of distribution for CoQ1) for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs were set to those estimated for VF2/α2. Values in normal font, estimated values; values in italic font, fixed values.

Significantly (likelihood ratio test; P < 0.005) different from the corresponding normoxic value.

Model predictions.

One approach for evaluating the above kinetic model is to test its ability to predict CoQ1 and/or CoQ1H2 indicator dilution data not used for estimating the kinetic model parameters (2, 13). To this end, we carried out the following experiments and tested the ability of the model to predict their results.

The first experiment was to evaluate the effect of inhibiting CoQ1H2 oxidation using cyanide (2 mM) on the steady-state rate of CoQ1H2 efflux during CoQ1 infusion in normoxic (n = 4) and hyperoxic (n = 4) lungs. Figure 7 shows that, in the presence of cyanide, which closes complex III for CoQ1H2 oxidation, the steady-state rates of CoQ1H2 efflux were ∼30–100% higher than in the absence of cyanide (control) over the range of CoQ1 concentrations studied in normoxic (Fig. 7A) and hyperoxic (Fig. 7B) lungs.

Fig. 7.

The relationship between the steady-state rate of CoQ1H2 efflux and the infused CoQ1 concentrations for normoxic (A) and hyperoxic (B) lungs in the absence (control) or presence of cyanide. Each lung was first perfused with cyanide (2 mM) for 5 min to inhibit complex III-mediated CoQ1H2 oxidation. This was followed by four successive 30-s arterial pulse infusions at concentrations of 50, 100, 200, and 400 μM CoQ1 at a flow of 30 ml/min, where cyanide was present throughout the infusion protocol. The normoxic (A) and hyperoxic (B) steady-state CoQ1H2 efflux rates in the absence of cyanide are the same as those shown in Fig. 4 (control). Values are means ± SE. For normoxic lungs, n = 6 and 4 for control and cyanide, respectively, for a total of 10 lungs. For hyperoxic lungs, n = 7 and 4 for control and cyanide, respectively, for a total of 11 lungs. *Significantly different from the rates in the absence of cyanide (control) at the same infused CoQ1 concentrations, P < 0.05. The solid lines are model fits to the mean values of the data in the absence of cyanide. The dashed lines are model prediction for the data in the presence of cyanide.

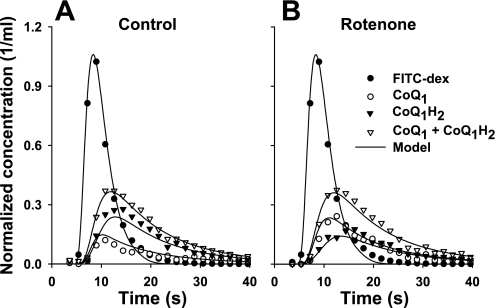

The second experiment was to evaluate the effect of inhibiting complex I-mediated CoQ1 reduction on the venous effluent concentration vs. time outflow curves for CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 following CoQ1 arterial bolus injection in one normoxic lung. Again, the FITC-dex venous effluent curve in Fig. 8 represents what the CoQ1 venous effluent curve would have been had CoQ1 not interacted with the lung as it passed through the pulmonary vessels. Figure 8 shows that ∼71% of the injected CoQ1 was recovered as CoQ1H2 in the venous effluent in the absence of the complex I inhibitor rotenone (Fig. 8A) compared with ∼49% in the presence of rotenone (Fig. 8B). Furthermore, despite the differences in the venous effluent curves of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 in the absence (Fig. 8A) and presence (Fig. 8B) of rotenone, the venous effluent curves of (CoQ1 + CoQ1H2) are virtually superimposable, suggesting that CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 have similar tissue volumes of distribution accessible from the vascular region.

Fig. 8.

Venous effluent concentration (as a fraction of injected amount of FITC-dex or CoQ1 per milliliter of effluent perfusate) vs. time curves for FITC-dex, CoQ1, CoQ1H2, and CoQ1 + CoQ1H2 following bolus injections containing either FITC-dex (35 μM) or CoQ1 (400 μM) into the pulmonary arterial inflow of one normoxic lung in the absence (A) and presence (B) of rotenone (20 μM) at a perfusate flow of 10 ml/min. The solid lines are model predictions.

The solid lines superimposed over this data in Figs. 7 and 8 are the predicted organ model solutions. For these predictions, the values of the model parameters for normoxic and hyperoxic lungs were set to those in Table 5, estimated from the data in Figs. 2–5. The ability to predict the dominant features of the data in Figs. 7 and 8 is further evidence that the model in Fig. 6 provides a reasonable explanation of the dominant vascular and tissue processes that determine the pulmonary disposition of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 on passage through the lungs of normoxic and hyperoxic rats.

DISCUSSION

The results demonstrate the capacity of the rat lung to reduce CoQ1 to CoQ1H2 and to oxidize CoQ1H2 to CoQ1 on passage through the rat pulmonary circulation. The dominant CoQ1 reductases are mitochondrial electron transport complex I and NQO1, as revealed by the inhibitory effects of rotenone and dicumarol, respectively (11, 23, 30, 32, 35, 45, 46). The data also shows that additional rotenone and dicumarol-insensitive reductase(s) contribute to CoQ1 reduction on passage though the pulmonary circulation. This was revealed by the observation that dicumarol plus rotenone did not completely eliminate CoQ1H2 efflux during CoQ1 infusion over the range of CoQ1 concentrations studied (Fig. 4C). Potential rotenone-dicumarol-insensitive CoQ1 reductases include mitochondrial electron transport complex II, transplasma membrane electron transport, and glycerol-3-phosphate-CoQ reductase (34, 52, 57, 62). There is also the possibility of CoQ1 reduction at a rotenone-insensitive site on complex I (30, 46).

The oxidation of CoQ1H2 on passage through the pulmonary circulation was inhibited by cyanide, suggesting that the predominant pulmonary CoQ1H2 oxidase is mitochondrial electron transport complex III. Cyanide promotes a reduced state for complex III, thereby eliminating complex III as a pathway for oxidation of quinones, including CoQ1H2 in pulmonary endothelial cells (23, 48). The ability of CoQ1H2 to serve as an electron donor for complex III has also been previously observed in purified yeast complex III and hepatocytes (23, 42).

The utility of the proposed kinetic model is in its ability to account for and evaluate potential changes in one or more of the dominant processes that determine the disposition of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 on passage through the pulmonary circulation. This is important, especially if rotenone-sensitive CoQ1 reduction is to be used as an index of complex I activity in other models of lung injury or oxidative stress, where the activities of multiple redox processes might be altered (60).

The kinetic model analysis revealed that the ∼23% decrease in CoQ1 reduction capacity in hyperoxic lungs could be accounted for by ∼47% decrease in the maximum rate or capacity (Vmax1) of complex I-mediated CoQ1 reduction, with no effect on any of the other tissue or vascular processes hypothesized in the kinetic model. This is in contrast to longer exposure to 85% O2 (21 days), which, in addition to increasing the capacity of NQO1-mediated DQ reduction, decreased vascular volume and perfused capillary surface area (PS) and increased the heterogeneity of the vascular transit time distribution (3).

The observations of a lack of an effect of rat exposure to 85% O2 for 48 h on NQO1-mediated CoQ1 reduction and mitochondrial complex III-mediated CoQ1H2 oxidation are consistent with the results of our laboratory's previous study of DQ and DQH2 redox metabolism in the rat lung (3). Our previous study revealed that rat exposure to 85% O2 for 48 h had no significant effect on NOQ1-mediated DQ reduction or complex III-mediated DQH2 oxidation during passage through the lung (3). Moreover, exposure to 85% O2 for 48 h had no significant effect on NQO1 activity or protein measured in cytosolic fractions of lung homogenates (3).

The decrease in complex I activity in the present study represents a relatively early in situ metabolic consequence of hyperoxia in that it precedes effects on lung histology, morphometry, and hemodynamic and perfusion kinematics observed with rat exposure to 85% O2 for >72 h, but not for 24 or 48 h (3, 26). Of the few studies evaluating the metabolic consequences of hyperoxia in the 18- to 48-h period, a decrease in serotonin clearance and an increase in lactate production have been observed in lungs from rats exposed to 100% O2 for 18 and 36 h, respectively (15, 36, 43). Additionally, Klein et al. demonstrated a decrease in the metabolism of prostaglandin E2 metabolism in intact lungs of rats exposed to >97% O2 for 36 h (43).

The 48% decrease in mitochondrial complex I activity measured in P2 fractions from hyperoxic compared with normoxic lung homogenates was not associated with a detectable change in whole lung O2 consumption rate (Table 1), which is an approximation of the total steady-state consumption rate of reducing equivalents by the entire lung (2). One possible explanation is that complex I activity is normally in excess compared with the rate of electron flow through the respiratory chain. This is consistent with the results of a study by Barrientos and Moraes (11), in which the effects of complex I impairment on cell respiration were evaluated in a rotenone-treated human osteosarcoma-derived cell line. They showed that complex I activity was inhibited by as much as ∼35%, with little effect (∼5%) on cell respiration. Another possible explanation is activation of compensatory mechanisms (e.g., mitochondrial electron transport complex II, glycerol phosphate dehydrogenase) to sustain respiration in the complex I-impaired hyperoxic lung.

There is ample evidence that increased production of ROS is a major factor in hyperoxic lung injury (19, 22, 37, 38). Thus one strategy that cells may follow to protect against hyperoxic lung injury is to mitigate the activities of ROS sources (18, 22, 59). Mitochondrial electron transport complex I is a major source of ROS (18, 59). Moreover, studies have shown that the rate of ROS formation at complex I in endothelial cells increased with an increase in O2 tension and that complex I inactivation using rotenone decreased ROS generation in sheep pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells exposed to hyperoxia (100% O2 for 30 min) (18, 54). Additional studies would be needed to evaluate the effect of the depression in complex I activity observed in hyperoxic lungs on ROS production at complex I and to determine whether this depression is an injury resulting from the increase in mitochondrial ROS production (24) or an early manifestation of an adaptive response to the hyperoxic environment (26).

Previous studies have addressed the quinone specificity of mitochondrial complex I and NQO1 (1, 29, 30, 33, 45, 48). Complex I, which catalyzes the transfer of electrons from NADH to ubiquinone, appears to be specific in terms of the structural and steric requirements for quinones to act as good electron acceptors (29, 30, 45). For instance, complex I has relatively high catalytic efficiencies for ubiquinone homologs with short isoprenoid side chains (e.g., CoQ1), and ubiquinone analogs having straight saturated chains (e.g., decyl-ubiquinone) (29, 30, 45). On the other hand, the benzoquinone DQ is considered a poor electron acceptor from complex I due to steric factors (30, 45). This is consistent with our laboratory's results from a previous study in which we showed that DQ reduction during passage through the rat lung was predominantly (>98%) via NQO1 (2).

Quantitative structure-function studies have suggested that quinones with van der Waals volumes of <200 Å are better electron acceptors from NQO1 than quinones with van der Waals volumes of >200 Å (1, 33). Based on the van der Waals volumes of DQ (162.9 Å) and CoQ1 (243.96 Å), one would expect DQ to be a better NQO1 substrate than CoQ1. This might explain the lower capacity of NQO1-mediated CoQ1 reduction (1.17 μmol/min) compared with NQO1-mediated DQ reduction (1.95 μmol/min) during passage through the rat lung (3).

Our laboratory's previous study of CoQ1 reduction in bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells (PAEC) provides insight into the results of the present study, and vice versa (48). Like the lung, the cells mediated reduction of CoQ1 to CoQ1H2, the latter of which appeared in the extracellular medium. The reduction rate (∼0.7 nmol·min−1·cm−2 of endothelial cell surface area) was sufficient to account for most of CoQ1 reduction on passage through the rat pulmonary circulation (∼0.9 nmol·min−1·cm−2, assuming a rat lung endothelial surface area of ∼4,500 cm2) (3). Also, as in the lung, exposure of the cells to hyperoxia (albeit 95% O2 for 48 h) decreased CoQ1 reduction capacity via a depression in complex I activity, although the decrease in CoQ1 reduction capacity and complex I activity in cells (52 and 80%, respectively) was larger than those in the lung (23 and 47%, respectively).

Whereas CoQ1 reduction could be accounted for predominantly by complex I activity in cultured PAEC, CoQ1 reduction in the lung is shared by complex I and NQO1. Whether the difference between lungs and cultured PAEC is attributable to cell culture conditions, contribution of other lung cell types to CoQ1 reduction on passage through the pulmonary circulation, species difference in NQO1 electron acceptor preference (33), or the fact that cultured PAEC were derived from a large vessel, wherein the reduction in the intact lung presumably takes place largely in the capillaries, or other factors, is not known.

For blood-borne electron acceptors that are permeable to the lung tissue from the vasculature and are complex I substrates, the concept is that the lung would play a role in determining their redox status and concentrations in plasma and hence in their bioactivity and bioavailability upon entry into the systemic circulation. This might include a range of pharmacological, physiological, and toxic redox active compounds (e.g., quinones) (2, 7, 21, 45, 50). The further implication is that, when complex I activity is depressed, such as in the hyperoxic exposure we described, and perhaps other models of oxidative stress, the impact of the lung on such substances would be altered. Previously, our laboratory demonstrated the utility of various other redox active compounds as probes in indicator dilution methods for evaluating the activities of pulmonary endothelial transplasma membrane electron transport systems, NQO1, and monoamine oxidases in the intact lung (2–5, 9, 16, 27). The present study demonstrates the addition of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 to this series of nondestructive probes for evaluating lung redox functions, including mitochondrial complexes I and III, in experimental models of lung injury and disease.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-24349, HL-65537, and the Department of Veterans Affairs.

APPENDIX

Based on the model depicted in Fig. 6, the species balance equations descriptive of spatial and temporal variations in the concentrations of CoQ1, CoQ1H2 in vascular volume (Vc), and tissue or extravascular volume (Ve) of a single capillary element, and in the concentration of FITC-dex in the vascular volume are:

|

(A1) |

|

(A2) |

|

(A3) |

where W is convective transport velocity = L/t̄c; x = 0 and x = L are the capillary inlet and outlet, respectively; t̄c is the capillary mean transit time; [FITC-dex](x, t), [CoQ1](x, t), and [CoQ1H2](x, t) are vascular concentrations of FITC-dex and free CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 forms, respectively, at distance x from the capillary inlet and time t; [ ] = α1[CoQ1] and [

] = α1[CoQ1] and [ ] = α2[CoQ1H2] are the total (free + BSA bound) vascular concentrations of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2, respectively; α1 = 1 + (CoQ1 bound fraction/CoQ1 free fraction) = 14.6 and α2 = 1 + (CoQ1H2 bound fraction/CoQ1H2 free fraction) = 16.5 are constants that account for the rapidly equilibrating interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 with the 5% BSA (i.e., Pc) perfusate calculated from the fractions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 bound to BSA obtained by ultrafiltration; VF1/α1 = (α3/α1) Ve and VF2/α2 = (α4/α2) Ve (ml) are the respective virtual volumes of distribution for CoQ1 and CoQ1H2, where α3 and α4 are constants that account for the rapidly equilibrating interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 with lung tissue sites (Pe) of association, respectively.

] = α2[CoQ1H2] are the total (free + BSA bound) vascular concentrations of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2, respectively; α1 = 1 + (CoQ1 bound fraction/CoQ1 free fraction) = 14.6 and α2 = 1 + (CoQ1H2 bound fraction/CoQ1H2 free fraction) = 16.5 are constants that account for the rapidly equilibrating interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 with the 5% BSA (i.e., Pc) perfusate calculated from the fractions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 bound to BSA obtained by ultrafiltration; VF1/α1 = (α3/α1) Ve and VF2/α2 = (α4/α2) Ve (ml) are the respective virtual volumes of distribution for CoQ1 and CoQ1H2, where α3 and α4 are constants that account for the rapidly equilibrating interactions of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 with lung tissue sites (Pe) of association, respectively.

For the steady state during pulse infusion of CoQ1, CoQ1H2, or FITC-dex, Eqs. A1–A3 reduce to:

|

(A4) |

|

(A5) |

|

(A6) |

Equations A1–A6 are for a single capillary element. To account for the effect of capillary perfusion kinematics on the plasma concentrations and redox status of CoQ1 and CoQ1H2 on passage through the pulmonary circulation, an organ model was constructed that accounts for the distribution of pulmonary capillary transit times, hc(t), which was previously determined for the normoxic rat lung (2), and was represented in the model using a random walk function (2, 3).

To model CoQ1 or CoQ1H2 pulse infusions or bolus injections, given hc(t), Eqs. A1–A3 are solved numerically with appropriate initial (t = 0) and boundary (x = 0) conditions (2, 5, 7). To provide the whole organ output [ ] and [

] and [ ], the outputs for all transit times are summed, each weighted according to hc(t), as previously described (2, 5, 7, 28).

], the outputs for all transit times are summed, each weighted according to hc(t), as previously described (2, 5, 7, 28).

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anusevicius Z, Sarlauskas J, Cenas N. Two-electron reduction of quinones by rat liver NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase: quantitative structure-activity relationships. Arch Biochem Biophys 404: 254–262, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audi SH, Bongard RD, Dawson CA, Siegel D, Roerig DL, Merker MP. Duroquinone reduction during passage through the pulmonary circulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 285: L1116–L1131, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Audi SH, Bongard RD, Krenz GS, Rickaby DA, Haworth ST, Eisenhauer J, Roerig DL, Merker MP. Effect of chronic hyperoxic exposure on duroquinone reduction in adult rat lungs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 289: L788–L797, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Audi SH, Bongard RD, Okamoto Y, Merker MP, Roerig DL, Dawson CA. Pulmonary reduction of an intravascular redox polymer. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L1290–L1299, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Audi SH, Dawson CA, Ahlf SB, Roerig DL. Oxygen dependency of monoamine oxidase activity in the intact lung. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 281: L969–L981, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Audi SH, Dawson CA, Linehan JH, Krenz GS, Ahlf SB, Roerig DL. Pulmonary disposition of lipophilic amine compounds in the isolated perfused rabbit lung. J Appl Physiol 84: 516–530, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Audi SH, Linehan JH, Krenz GS, Dawson CA. Accounting for the heterogeneity of capillary transit times in modeling multiple indicator dilution data. Ann Biomed Eng 26: 914–930, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Audi SH, Linehan JH, Krenz GS, Dawson CA, Ahlf SB, Roerig DL. Estimation of the pulmonary capillary transport function in isolated rabbit lungs. J Appl Physiol 78: 1004–1014, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Audi SH, Olson LE, Bongard RD, Roerig DL, Schulte ML, Dawson CA. Toluidine blue O and methylene blue as endothelial redox probes in the intact lung. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H137–H150, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Audi SH, Zhao H, Bongard RD, Hogg N, Kettenhofen NJ, Kalyanaraman B, Dawson CA, Merker MP. Pulmonary arterial endothelial cells affect the redox status of coenzyme Q0. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 892–907, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barrientos A, Moraes CT. Titrating the effects of mitochondrial complex I impairment in the cell physiology. J Biol Chem 274: 16188–16197, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bassingthwaighte JB, Goresky CA, Linehan JH. (editors). Whole Organ Approaches to Cellular Metabolism: Permeation, Cellular Uptake, and Product Formation. New York: Springer, 1998.

- 13.Beard DA, Bassingthwaighte JB, Greene AS. Computational modeling of physiological systems. Physiol Genomics 23: 1–4, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beyer RE, Segura-Aguilar J, Di Bernardo S, Cavazzoni M, Fato R, Fiorentini D, Galli MC, Setti M, Landi L, Lenaz G. The role of DT-diaphorase in the maintenance of the reduced antioxidant form of coenzyme Q in membrane systems. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 2528–2532, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Block ER, Fisher AB. Depression of serotonin clearance by rat lungs during oxygen exposure. J Appl Physiol 42: 33–38, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bongard RD, Krenz GS, Linehan JH, Roerig DL, Merker MP, Widell JL, Dawson CA. Reduction and accumulation of methylene blue by the lung. J Appl Physiol 77: 1480–1491, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bongard RD, Merker MP, Shundo R, Okamoto Y, Roerig DL, Linehan JH, Dawson CA. Reduction of thiazine dyes by bovine pulmonary arterial endothelial cells in culture. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 269: L78–L84, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brueckl C, Kaestle S, Kerem A, Habazettl H, Krombach F, Kuppe H, Kuebler WM. Hyperoxia-induced reactive oxygen species formation in pulmonary capillary endothelial cells in situ. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 34: 453–463, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budinger GR, Sznajder JI. To live or die: a critical decision for the lung. J Clin Invest 115: 828–830, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cadenas E Antioxidant and prooxidant functions of DT-diaphorase in quinone metabolism. Biochem Pharmacol 49: 127–140, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cadenas E, Boveris A, Ragan CI, Stoppani AO. Production of superoxide radicals and hydrogen peroxide by NADH-ubiquinone reductase and ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase from beef-heart mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys 180: 248–257, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campian JL, Qian M, Gao X, Eaton JW. Oxygen tolerance and coupling of mitochondrial electron transport. J Biol Chem 279: 46580–46587, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan TS, Teng S, Wilson JX, Galati G, Khan S, O'Brien PJ. Coenzyme Q cytoprotective mechanisms for mitochondrial complex I cytopathies involves NAD(P)H: quinone oxidoreductase 1(NQO1). Free Radic Res 36: 421–427, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen YR, Chen CL, Zhang L, Green-Church KB, Zweier JL. Superoxide generation from mitochondrial NADH dehydrogenase induces self-inactivation with specific protein radical formation. J Biol Chem 280: 37339–37348, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho HY, Jedlicka AE, Reddy SP, Kensler TW, Yamamoto M, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Role of NRF2 in protection against hyperoxic lung injury in mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 26: 175–182, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crapo JD, Barry BE, Foscue HA, Shelburne J. Structural and biochemical changes in rat lungs occurring during exposures to lethal and adaptive doses of oxygen. Am Rev Respir Dis 122: 123–143, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawson CA, Audi SH, Bongard RD, Okamoto Y, Olson L, Merker MP. Transport and reaction at endothelial plasmalemma: distinguishing intra- from extracellular events. Ann Biomed Eng 28: 1010–1018, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dawson CA, Audi SH, Krenz GS, Roerig DL. Endothelium and Compound Transfer. In: Molecular Nuclear Medicine: The Challenge of Genomics and Proteomics to Clinical Practice, edited by Feinendegen LE, Eckelman WC, Bahk YW, and Wagner Jr. HN. New York: Springer, 2003, p. 201–216.

- 29.Degli Esposti M, Ngo A, McMullen GL, Ghelli A, Sparla F, Benelli B, Ratta M, Linnane AW. The specificity of mitochondrial complex I for ubiquinones. Biochem J 313: 327–334, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Di Virgilio F, Azzone GF. Activation of site I redox-driven H+ pump by exogenous quinones in intact mitochondria. J Biol Chem 257: 4106–4113, 1982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinkova-Kostova AT, Talalay P. Persuasive evidence that quinone reductase type 1 (DT diaphorase) protects cells against the toxicity of electrophiles and reactive forms of oxygen. Free Radic Biol Med 29: 231–240, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dragan M, Dixon SJ, Jaworski E, Chan TS, O'Brien PJ, Wilson JX. Coenzyme Q(1) depletes NAD(P)H and impairs recycling of ascorbate in astrocytes. Brain Res 1078: 9–18, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Faig M, Bianchet MA, Talalay P, Chen S, Winski S, Ross D, Amzel LM. Structures of recombinant human and mouse NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases: species comparison and structural changes with substrate binding and release. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 3177–3182, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fato R, Bernardo SD, Estornell E, Parentic Castelli G, Lenaz G. Saturation kinetics of coenzyme Q in NADH oxidation: rate enhancement by incorporation of excess quinone. Mol Aspects Med 18, Suppl: S269–S273, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fato R, Estornell E, Di Bernardo S, Pallotti F, Parenti Castelli G, Lenaz G. Steady-state kinetics of the reduction of coenzyme Q analogs by complex I (NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase) in bovine heart mitochondria and submitochondrial particles. Biochemistry 35: 2705–2716, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fisher AB Energy status of the rat lung after exposure to elevated Po2. J Appl Physiol 45: 56–59, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freeman BA, Crapo JD. Hyperoxia increases oxygen radical production in rat lungs and lung mitochondria. J Biol Chem 256: 10986–10992, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Haugaard N Cellular mechanisms of oxygen toxicity. Physiol Rev 48: 311–373, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huet S, Bouvier A, Pourat MA, Jolivet E. Statistical Tools For Nonlinear Regression. New York: Springer, 2004.

- 40.Jaiswal AK Regulation of genes encoding NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductases. Free Radic Biol Med 29: 254–262, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadokura H, Bader M, Tian H, Bardwell JC, Beckwith J. Roles of a conserved arginine residue of DsbB in linking protein disulfide-bond-formation pathway to the respiratory chain of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 10884–10889, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kauten R, Tsai AL, Palmer G. The kinetics of reduction of yeast complex III by a substrate analog. J Biol Chem 262: 8658–8667, 1987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klein LS, Fisher AB, Soltoff S, Coburn RF. Effect of O2 exposure on pulmonary metabolism of prostaglandin E2. Am Rev Respir Dis 118: 622–625, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Landaw EM, DiStefano JJ 3rd. Multiexponential, multicompartmental, and noncompartmental modeling. II. Data analysis and statistical considerations. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 246: R665–R677, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lenaz G Quinone specificity of complex I. Biochim Biophys Acta 1364: 207–221, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lenaz G, Fato R, Baracca A, Genova ML. Mitochondrial quinone reductases: complex I. Methods Enzymol 382: 3–20, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Merker MP, Audi SH, Bongard RD, Lindemer BJ, Krenz GS. Influence of pulmonary arterial endothelial cells on quinone redox status: effect of hyperoxia induced NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1). Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L607–L619, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Merker MP, Audi SH, Lindemer BJ, Krenz GS, Bongard RD. Role of mitochondrial electron transport complex I in coenzyme Q1 reduction by intact pulmonary arterial endothelial cells and the effect of hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 293: L809–L819, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Merker MP, Bongard RD, Kettenhofen NJ, Okamoto Y, Dawson CA. Intracellular redox status affects transplasma membrane electron transport in pulmonary arterial endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L36–L43, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]