Abstract

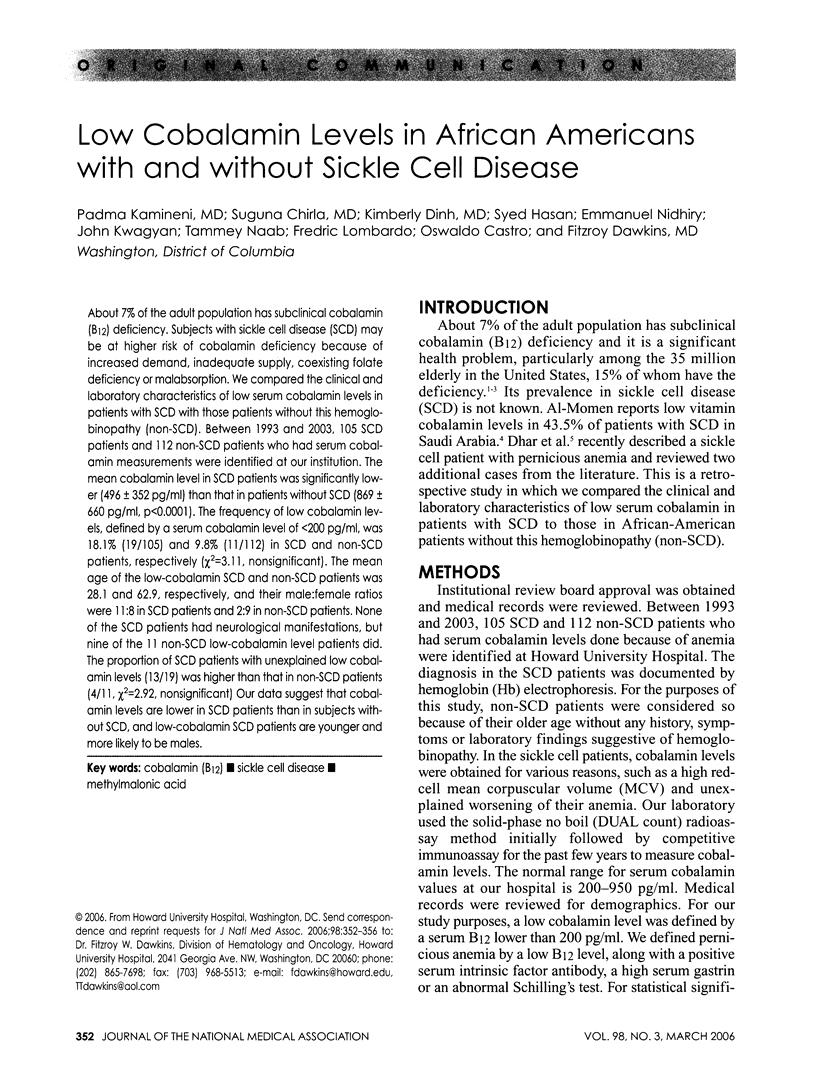

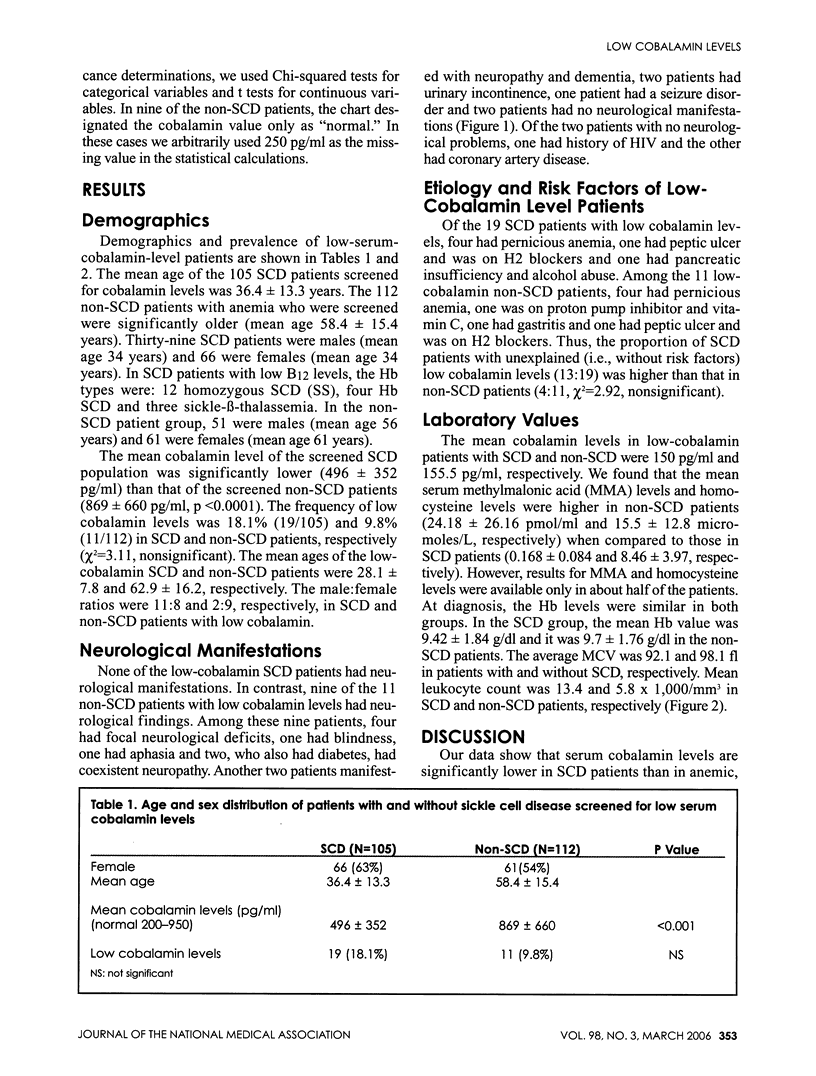

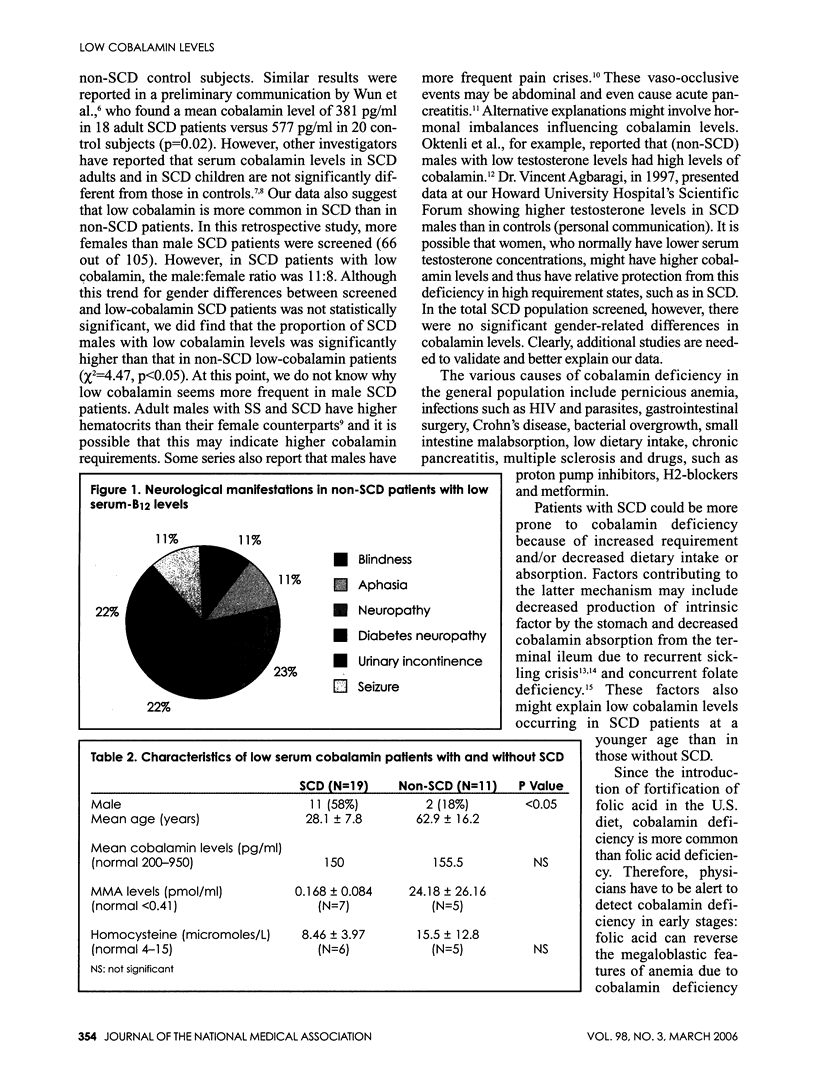

About 7% of the adult population has subclinical cobalamin (B12) deficiency. Subjects with sickle cell disease (SCD) may be at higher risk of cobalamin deficiency because of increased demand, inadequate supply, coexisting folate deficiency or malabsorption. We compared the clinical and laboratory characteristics of low serum cobalamin levels in patients with SCD with those patients without this hemoglobinopathy (non-SCD). Between 1993 and 2003, 105 SCD patients and 112 non-SCD patients who had serum cobalamin measurements were identified at our institution. The mean cobalamin level in SCD patients was significantly lower (496 +/- 352 pg/ml) than that in patients without SCD (869 +/- 660 pg/ml, p<0.0001). The frequency of low cobalamin levels, defined by a serum cobalamin level of <200 pg/ml, was 18.1% (19/105) and 9.8% (11/112) in SCD and non-SCD patients, respectively (chi2=3.11, nonsignificant). The mean age of the low-cobalamin SCD and non-SCD patients was 28.1 and 62.9, respectively, and their male:female ratios were 11:8 in SCD patients and 2:9 in non-SCD patients. None of the SCD patients had neurological manifestations, but nine of the 11 non-SCD low-cobalamin level patients did. The proportion of SCD patients with unexplained low cobalamin levels (13/19) was higher than that in non-SCD patients (4/11, chi2=2.92, nonsignificant) Our data suggest that cobalamin levels are lower in SCD patients than in subjects without SCD, and low-cobalamin SCD patients are younger and more likely to be males.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Carmel R. Cobalamin, the stomach, and aging. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997 Oct;66(4):750–759. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.4.750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel Ralph, Green Ralph, Rosenblatt David S., Watkins David. Update on cobalamin, folate, and homocysteine. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2003:62–81. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2003.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmel Ralph, Melnyk Stepan, James S. Jill. Cobalamin deficiency with and without neurologic abnormalities: differences in homocysteine and methionine metabolism. Blood. 2002 Dec 19;101(8):3302–3308. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-09-2746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhar Meekoo, Bellevue Rita, Carmel Ralph. Pernicious anemia with neuropsychiatric dysfunction in a patient with sickle cell anemia treated with folate supplementation. N Engl J Med. 2003 May 29;348(22):2204–2207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhiman Rk, Yusif Ra, Nabar Uj, Albaqali A. Images of interest. Gastrointestinal: ischemic enteritis and sickle cell disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004 Nov;19(11):1318–1318. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donaldson M. S. Metabolic vitamin B12 status on a mostly raw vegan diet with follow-up using tablets, nutritional yeast, or probiotic supplements. Ann Nutr Metab. 2000;44(5-6):229–234. doi: 10.1159/000046689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engelhardt T., Pulitzer D. R., Etheredge E. E. Ischemic intestinal necrosis as a cause of atypical abdominal pain in a sickle cell patient. J Natl Med Assoc. 1989 Oct;81(10):1077, 1080-4, 1087-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Mary Ann, Hawthorne Nicole A., Brackett Wimberly R., Fischer Joan G., Gunter Elaine W., Allen Robert H., Stabler Sally P. Hyperhomocysteinemia and vitamin B-12 deficiency in elderly using Title IIIc nutrition services. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003 Jan;77(1):211–220. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liaugaudas G., Jacques P. F., Selhub J., Rosenberg I. H., Bostom A. G. Renal insufficiency, vitamin B(12) status, and population attributable risk for mild hyperhomocysteinemia among coronary artery disease patients in the era of folic acid-fortified cereal grain flour. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001 May;21(5):849–851. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.21.5.849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus E. M. Whole blood folate values in pernicious anaemia: relation to treatment. Eur J Haematol. 1987 Jul;39(1):39–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1987.tb00161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinow R. M., Johnson C. S., Karnaze D. S., Siegel M. E., Carmel R. Unsuspected pernicious anemia in a patient with sickle cell disease receiving routine folate supplementation. Arch Intern Med. 1987 Oct;147(10):1828–1829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler S. P., Lindenbaum J., Allen R. H. Vitamin B-12 deficiency in the elderly: current dilemmas. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997 Oct;66(4):741–749. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stabler S. P. Vitamin B12 deficiency in older people: improving diagnosis and preventing disability. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998 Oct;46(10):1317–1319. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb04554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WATERS A. H., MOLLIN D. L. Observations on the metabolism of folic acid in pernicious anaemia. Br J Haematol. 1963 Jul;9:319–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1963.tb06556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- al-Momen A. K. Diminished vitamin B12 levels in patients with severe sickle cell disease. J Intern Med. 1995 Jun;237(6):551–555. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1995.tb00884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]