Abstract

Heightened sensitivity of the diabetic proximal tubule to dietary salt leads to a paradoxical effect of salt on glomerular filtration rate (GFR) via tubuloglomerular feedback. Diabetic hyperfiltration is a feedback response to growth and hyperreabsorption by the proximal tubule. The present studies were performed to determine whether growth and hyperfunction of the proximal tubule are essential for its hyperresponsiveness to dietary salt and, hence, to the paradoxical effect of dietary salt on GFR. Micropuncture was performed in four groups of inactin-anesthetized Wistar rats after 10 days of streptozotocin diabetes drinking tap water or 1% NaCl. Kidney growth was suppressed with ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) inhibitor, DFMO (200 mg·kg−1·day−1), or placebo. Single nephron GFR (SNGFR) was manipulated by perfusing Henle's loop so that proximal reabsorption (Jprox) could be expressed as a function of SNGFR in each nephron, dissociating primary effects on the tubule from the effects of glomerulotubular balance. Alone, DFMO or high salt reduced SNGFR and suppressed Jprox independent of SNGFR. Suppression of Jprox was eliminated and SNGFR increased when high salt was given to rats receiving DFMO. ODC is necessary for hyperresponsiveness of the proximal tubule to dietary salt and for the paradoxical effect of dietary salt on GFR in early diabetes. This coupling of effects adds to the body of evidence that feedback from the proximal tubule is the principal governor of glomerular filtration in early diabetes.

Keywords: diabetic hyperfiltration, proximal tubular reabsorption, tubuloglomerular feedback, glomerulotubular balance

glomerular hyperfiltration is a cardinal feature of early diabetes mellitus (5). Several lines of evidence support a tubular hypothesis to explain how glomerular filtration rate (GFR) comes to be elevated in early diabetes (reviewed in Ref. 17). According to this hypothesis, hyperfiltration is rooted in a prior increase in proximal reabsorption with GFR rising secondarily via negative feedback through the macula densa. In the course of trying to determine how the initial increase in proximal reabsorption comes about, we previously discovered that it could be prevented by suppressing growth of the kidney (15), which is normally rapid in early diabetes (10). We also discovered that proximal reabsorption in early diabetes is overly sensitive to dietary salt, to the extent that, when placed on a high salt diet, a diabetic rat drops its proximal reabsorption sufficiently to activate tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF), thereby reducing single nephron GFR (SNGFR) (20, 21). Since a reciprocal effect of dietary salt on GFR is contrary to usual expectation, we refer to this phenomenon as the salt paradox. So far, the salt paradox has not been reported outside of diabetes. Presently, we examined rats with early diabetes to determine whether kidney enlargement is essential for heightened effect of dietary salt on proximal reabsorption and the ensuing salt paradox.

METHODS

Overview

The effect of dietary salt on proximal reabsorption was determined by micropuncture in early streptozotocin diabetic rats and in diabetic rats administered the ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) inhibitor, difluromethyl ornithine (DFMO), which is known to mitigate kidney enlargement in early streptozotocin diabetes (7, 8, 15). A micropuncture protocol was employed in which the TGF signal is artificially manipulated as a means for changing SNGFR so that proximal tubular reabsorption can be characterized over a range of SNGFR in individual nephrons. The effects of dietary salt and DFMO on this relationship between kidney size, proximal reabsorption, and SNGFR were analyzed as a direct test for primary differences in proximal reabsorption. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals with an IACUC-registered protocol.

Diabetes

Adult male Wistar rats (Simonson Labs, Gilroy, CA) were made diabetic with streptozotocin (Sigma, 65 mg/kg ip × 1 dose). Thereafter, blood glucose was measured daily in late morning by glucometer and titrated in the range of 19–25 mM with daily subcutaneous injection of long-acting insulin (PZI, Blue Ridge Pharmaceuticals, Memphis, TN). Rats were housed in pairs with one rat in each cage also receiving daily subcutaneous injection of DFMO (200 mg·kg−1·day−1) and the other receiving saline placebo. Half the cages were free-fed standard rat chow (NaCl content 0.4% wt/wt) and given ad libitum access to tap water. The other half were fed standard rat chow and 1% saline was added to the drinking water. DFMO and saltwater were begun on the same day that streptozotocin was given.

Surgical Preparation for Micropuncture

Micropuncture experiments were performed after 10–11 days of diabetes and ∼24 h after the final doses of DFMO and insulin. Rats that were housed together were studied on consecutive days with the order (DFMO vs. placebo) alternated. Animals were surgically prepared according to previously established protocols (15). Briefly, animals were anesthetized with inactin (100 mg/kg ip; Research Biochemicals, Natick, MA) and body temperature was maintained on servo-controlled heating table. Airway was maintained with tracheostomy. Catheters were placed in jugular vein, femoral artery, and urinary bladder. The left kidney was exposed through a flank incision, immobilized in a lucite cup, and bathed with warm Ringer saline. The left ureter was cannulated for separate urine collection. Ringer saline containing 40 μCi/ml 3H-inulin was infused at 3.5 ml/h as a marker of GFR. Blood pressure was monitored throughout. Blood glucose was measured at the beginning and end of micropuncture. Plasma was sampled at the beginning and end of micropuncture and counted for radioactivity. One hour was allowed for equilibration between the end of surgery and the start of micropuncture. All micropuncture data for an individual animal were obtained within a period of 2 h. After micropuncture the kidneys were harvested and weighed.

Micropuncture Protocol

Micropuncture experiments were performed to assess the impact of dietary salt ± DFMO on overall reabsorption and glomerulotubular balance (GTB) in the proximal tubule. Due to GTB, reabsorption will vary with SNGFR and differences in SNGFR will confound other effects on proximal reabsorption. To correct for this, we manipulated the TGF signal to determine the relationship of proximal reabsorption to SNGFR in individual nephrons, and then tested for the effects of dietary salt ± DFMO on this relationship.

After 1 h for equilibration, late proximal nephrons were localized on the kidney surface and an obstructing wax block was inserted immediately upstream from the most downstream accessible segment. A microperfusion pipette containing artificial tubular fluid (ATF) was inserted downstream from the wax block to perfuse the loop of Henle. ATF contained (in mM) 130 NaCl, 10 NaHCO3, 4 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 45 mg% urea, 10 glucose, 0.1% FD&C, pH 7.4. Controlled perfusion of the loop of Henle was performed to activate TGF and thereby cause SNGFR to change. During perfusion, timed collections of tubular fluid were made upstream from the wax block to measure SNGFR and late proximal flow (VLP). Collections were made from each nephron during minimal TGF activation (loop of Henle microperfusion at 8 nl/min) and maximal TGF activation (loop of Henle microperfusion at 40 nl/min). Several nephrons were studied in each animal and the two perfusions per nephron were done in alternating order. Nephrons were vented upstream from the wax block before each collection to prevent pressure from building up in the proximal tubule. Two minutes were allowed for equilibration before each collection and each collection was for 3 min. Tubular fluid samples were assayed for volume by transfer to a constant-bore glass capillary and then counted for radioactivity to determine SNGFR. Data from these paired collections were exploited to characterize proximal reabsorption as a function of SNGFR by linear interpolation. Primary effects of dietary salt and DFMO were defined by differences in these functions. A justification for this method to test for effects on proximal reabsorption has been previously published (15, 16, 20).

Statistics

Statistical analysis of micropuncture data was by two-way ANOVA with design for repeated measures, analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), or Student's t-test. Analyses were done with commercial software (Systat, Evanston, IL), except for certain Student's t-tests, which were done by hand. Outliers were identified by Studentized residual >2.5 from the AN(C)OVA and analyses were repeated. Adjustment for multiple group comparisons was by Tukey or Bonferroni tests as appropriate.

RESULTS

General Data Leading up to Micropuncture

Animals lost weight during the first 2–3 days of diabetes and then begun to gain weight. Rats on high salt experienced less initial weight loss (7 ± 1 vs. 12 ± 2 g, P = 0.05). There was no significant effect of DFMO on initial weight loss (11 ± 2 vs. 8 ± 2 g) and the effect of dietary salt was independent of DFMO. Beyond day 3 of diabetes, animals gained weight and there were no significant differences in weight gain between groups.

Hyperglycemia was moderated by daily injection of long-acting insulin, which was dose adjusted each day based on glycemic history. By design, there were no differences between groups in the course of blood glucose concentrations. Animals receiving DFMO wound up receiving 50% more insulin per day than those receiving placebo (1.07 ± 0.06 vs. 0.72 ± 0.06 U/day, P < 0.01). Insulin requirement was not significantly influenced by dietary salt.

Animals were polydipsic and poluric as is typical of diabetic rats. It was not possible to determine the effect of DFMO on water drinking, since DFMO- and placebo-treated animals were housed together in pairs. Based on per-cage water consumption, rats on tap water drunk 140 ± 17 ml/day and those on high salt drunk 160 ± 22 ml/day.

General Data During Micropuncture

Blood pressure.

Mean arterial pressure ranged from 88 to 139 mmHg with a minor, nonsignificant tendency to be higher in those fed high salt (120 ± 4 vs. 114 ± 4 mmHg; Table 1). DFMO did not appear to alter the influence of dietary salt on blood pressure. The combined blood pressure and body weight data suggest that the efficiency of salt balance is not grossly affected by DFMO, notwithstanding major effects of DFMO on how the responsibility for salt balance is parsed along the nephron (vide infra).

Table 1.

Systemic data obtained during micropuncture

| Arterial BP, mmHg | Blood Glucose, mM | Urine Fiow, μ1/min | Glucose Reabsorption, μmol/min | FEglu, % | GFR, ml/min | Kidney Wt, g | GTB Efficiency | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (n = 7) | 118±5 | 18±2 | 11±6 | 43±6 | 4±2 | 2.5±0.2 | 3.4±0.1 | 0.78±0.08 | ||||||||

| Placebo+HS (n = 7) | 122±5 | 17±2 | 13±5 | 27±7 | 0.8±0.5 | 2.0±0.2 | 3.1±0.1 | 0.54±0.07 | ||||||||

| DFMO (n = 6) | 111±5 | 24±2 | 18±7 | 43±6 | 6±3 | 1.9±0.2 | 3.2±0.1 | 0.62±0.08 | ||||||||

| DFMO+HS (n = 5) | 118±6 | 20±2 | 23±8 | 46±7 | 3±1 | 2.5±0.2 | 3.6±0.1 | 0.74±0.09 | ||||||||

| ANOVA, P values | ||||||||||||||||

| DFMO | 0.07 | |||||||||||||||

| Salt | 0.11 | 0.05* | 0.02 | |||||||||||||

| Salt*DFMO | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.03† | |||||||||||||

Values ± SE from least squares AN(C)OVA. BP, arterial blood pressure; FE, fractional excretion; GTB, glomerulotubular balance; GFR, glomerular filtration rate; HS, high salt.

With blood glucose as covariate.

With single nephron GFR (SNGFR) as covariate. Statistics for FEglu based on log-transformed data. Cells left blank for P > 0.15.

GFR.

In placebo-treated diabetic rats, adding NaCl to the drinking water reduced two-kidney GFR by 20%, consistent with past observations on the diabetic salt paradox (20, 21, 23). DFMO lessened GFR by 25% in diabetic rats on standard diet, which also reproduced a prior finding (15). In contrast, adding NaCl to the drinking water of DFMO-treated rats caused GFR to increase by 26%. In other words, DFMO reversed the paradoxical effect of dietary salt on GFR (P = 0.03). GFR and total kidney weight tended to correlate (r = 0.46, P = 0.1). GFR data are not normalized for kidney weight because absolute differences in GFR are of bottom-line interest, with kidney weight afforded status as a potential determinant in our paradigm.

Urine flow rate.

Urine flow rate ranged from 4 to 63 μl/min. Although rats on high salt or DFMO produced more urine on average, these effects were not significant by straightforward ANOVA. A multivariate analysis showed no effect of blood pressure or GFR on urine flow rate, but urine flow rate did vary directly with blood glucose (P = 0.001). Using ANCOVA to adjust for blood glucose lessened the variability in urine flow by nearly half, which rendered a 67% greater urine flow rate among high-salt rats nearly significant (P = 0.09). Controlling for glucose excluded DFMO as a determinant of urine flow rate in the same analysis.

Blood glucose and glucose transport.

Although there was no effect of dietary salt or DFMO on the course of blood glucose leading up to micropuncture (vide supra), DFMO-treated animals wound up with higher blood glucose concentrations during micropuncture (22 ± 2 vs. 17 ± 2 mM, P < 0.03). Fractional excretion of glucose (FEglu) was measured in 21 animals and ranged 150-fold from 0.002 to 0.298. FEglu appeared log normal by inspection of normal probability plots (Systat) so AN(C)OVA for FEglu was done on log-transformed data after exclusion of a single outlier (Studentized residual 2.75). FEglu correlated with the filtered load of glucose (r = 0.64, P = 0.001). By two-way ANOVA, high salt diet appeared to lower FEglu by about half (P = 0.02) and this effect of dietary salt persisted when the test was repeated with filtered glucose as a covariate. DFMO tended to increase FEglu (Table 1), but the effect was nonsignificant and disappeared altogether after controlling for filtered glucose. Therefore, the present data are best viewed as underpowered and inconclusive regarding the role of ODC-mediated kidney growth in glucose reabsorption by the early diabetic kidney.

Kidney weight.

Kidneys were removed and weighed after microupuncture. There was one heavy outlier in the high salt group excluded from the analysis (Studentized residual = 4). Kidneys from placebo-treated rats on standard diet averaged ∼10% smaller than what we typically observe at this stage of diabetes in male Wistar rats of this size (15, 20). Consistent with past experience in early streptozotocin diabetes (15, 20), DFMO tended to reduce kidney size in rats fed standard diet, and high salt tended to reduce kidney size in placebo-treated rats. The ANOVA confirmed opposite effects of dietary salt on kidney weight in DFMO- vs. placebo-treated rats (P < 0.01).

Micropuncture Results

SNGFR.

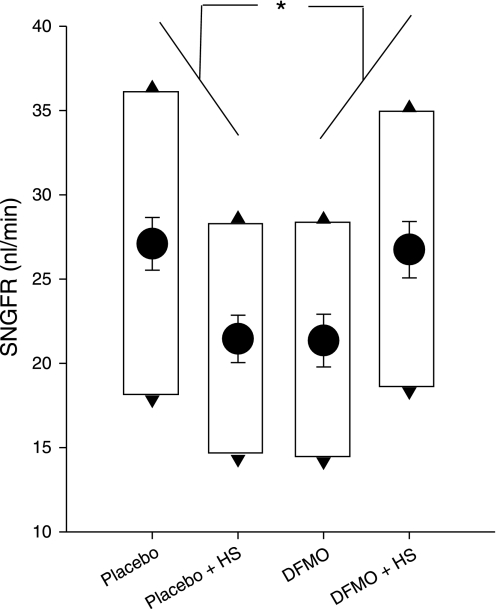

SNGFR was measured twice from the late proximal tubule in each nephron, once during maximal TGF activation (SNGFRmin), and once with no TGF activation (SNGFRmax). In all, this included 272 individual micropuncture collections from 136 nephrons. By two-way ANOVA applied to SNGFRmax, there was no independent effect of dietary salt or DFMO. However, the cross term (dietary salt × DFMO) was highly significant (P < 0.001), which reflects the following: in diabetic rats on a standard salt intake, DFMO reduced SNGFRmax (P < 0.04 by ANOVA with Tukey adjustment for multiple comparisons), reproducing a prior result (15). Meanwhile, increasing dietary salt reduced SNGFRmax (P < 0.03 by ANOVA with Tukey), reproducing the diabetic salt paradox (20). But in DFMO-treated diabetic rats, dietary salt had an effect normally seen in nondiabetic rats (16), which was to increase SNGFRmax. In other words, the diabetic salt paradox was reversed by DFMO (Fig. 1). This interaction between dietary salt and DFMO was also noted for SNGFRmin (P < 0.02 for Salt * DFMO cross-term in ANOVA).

Fig. 1.

Effects of dietary salt (DS) and difluromethyl ornithine (DFMO) on single nephron glomerular filtration rate (SNGFR) in early diabetic rats. HS, high-salt diet. Circles, least squares means ± SE for SNGFRmid from ANOVA. Top and bottom of boxes indicate group mean SNGFR during zero (SNGFRmax) and full (SNGFRmin) stimulation of tubuloglomerular feedback (TGF), respectively. *P < 0.001 for the cross term from 2-way ANOVA applied to SNGFRmid. Data represent 272 tubular fluid collections from 136 nephrons.

The same result for SNGFR was obtained when ANOVA was performed with repeated measures to incorporate both SNGFRmax and SNGFRmin into the model; the cross-term (dietary salt × DFMO) was significant (P < 0.001) while the opposing influence of dietary salt in placebo- vs. DFMO-treated animals ensured no primary effect of either salt or DFMO. The within-subjects portion of the repeated-measures ANOVA tests for the effect of salt and DFMO on the range of the TGF response. The means ± SD for the range of the TGF response in 136 nephrons were 16 ± 11 nl/min and there was no significant effect of dietary salt or DFMO. In the occasional nephron the recorded range of the TGF response was an underestimate of the true range because the effect of full-activation was so strong that flow ceased altogether. To produce data from those nephrons for studying proximal reabsorption, the LOH perfusion rate was reduced to allow measurable flow in the proximal tubule. So what can be legitimately claimed about TGF responsiveness is that it remained robust in all four groups.

Proximal Reabsorption

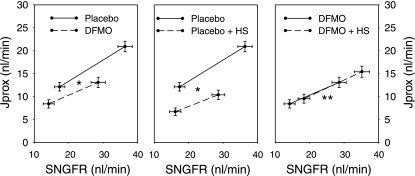

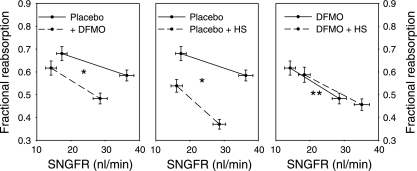

The effects of dietary salt and DFMO on proximal reabsorption are displayed in Figs. 2 and 3. Figure 2 makes pairwise comparisons among the experimental groups of net proximal reabsorption by plotting net reabsorption (Jprox) against SNGFR. After controlling for differences in SNGFR, either DFMO or dietary salt significantly reduced proximal reabsorption. However, dietary salt had no effect on Jprox if rats were also receiving DFMO. The significance of these findings was confirmed by several independent statistical methods. Multiple methods were used to mitigate the consequences should the data violate a core assumption of one or another of them. It turned out that all of the methods unambiguously supported the same conclusions: first, ANCOVA was performed for Jprox with dietary salt and DFMO as factors and SNGFR as covariate. This test confirmed an inhibitory effect of dietary salt on Jprox (P < 0.001) that was prevented by DFMO (P < 0.001). As expected, the covariate, SNGFR, was also an important predictor of Jprox (P < 0.001). The ANCOVA method assumes that the slope of the relationship between Jprox and SNGFR is the same in all groups. Since this assumption may not be valid (15), a second method was applied that does not require this assumption. This second method, as previously published (15, 20), uses linear interpolation between SNGFRmin and SNGFRmax to calculate means ± SE for Jprox as a continuous function of SNGFR and then applies Student's t-test at the point of maximum overlapping SNGFR. This point of maximum overlap occurred at SNGFR ≈24 nl/min both for control vs. DFMO and control vs. high salt. At SNGFR =24 nl/min, DFMO (P < 0.01) or high salt (P < 0.001) individually suppressed Jprox, whereas dietary salt had no effect on Jprox in DFMO-treated animals. Finally, we performed ANCOVA for fractional reabsorption with dietary salt and DFMO as factors and SNGFR as covariate. This test also confirmed that the inhibitory effect of dietary salt on proximal reabsorption was reduced by DFMO (P < 0.001; Fig. 3). The point of using SNGFR as a covariate for fractional reabsorption is to accommodate inherent imperfections in GTB that cause fractional reabsorption to decline as SNGFR increases (vide infra).

Fig. 2.

Effects of DS and DFMO on SNGFR and net proximal reabsorption (Jprox) in early diabetic rats. SNGFR was manipulated by perfusing Henle's loop to activate TGF. Values with minimum or maximum TGF activation shown connected by interpolation. DFMO or HS alone significantly reduced Jprox after adusting for SNGFR. Feeding HS to DFMO-treated rat caused Jprox to increase along its original line of glomerulotubular balance. In other words, DFMO abolished the primary effect of DS on Jprox. *P < 0.001 for the downward shift in Jprox in response to either HS or DFMO as determined by 1-way ANCOVA with repeated measures for the state of TGF activation, SNGFR as covariate, and Bonferroni adjustment for multiple group comparisons. **P < 0.001 for abolition of the downward effect of HS on Jprox (middle) by coadministration of DFMO as determined by 2-way ANCOVA applied to the pooled micropuncture data with SNGFR as covariate.

Fig. 3.

Effects of DS and DFMO on fractional reabsorption up to the late proximal tubule in early diabetic rats. SNGFR was manipulated by perfusing Henle's loop to activate TGF. Values with minimum or maximum TGF activation shown connected by interpolation. DFMO or HS alone significantly reduced fractional reabsorption at any given SNGFR. Feeding HS to DFMO-treated rats had no effect on fractional reabsorption. *P < 0.001 for difference in fractional reabsorption as determined by 1-way ANCOVA with repeated measures for the state of TGF activation, SNGFR as covariate, and Bonferroni adjustment for multiple group comparisons. **P < 0.001 for abolition of the downward effect of HS on fractional reabsorption (middle) by coadministration of DFMO as determined by 2-way ANCOVA applied to the pooled micropuncture data with SNGFR as covariate.

GTB

GTB refers to changes in tubular reabsorption that result from changes in SNGFR. The following index was used to evaluate the efficiency of GTB, which reflects the ability of the proximal tubule to buffer changes in filtered load through changes in proximal reabsorption:equation 1

|

where ΔJprox and ΔSNGFR are corresponding differences between the two levels of TGF activation in a nephron and Jproxmid/SNGFRmid is the fractional reabsorption at the midpoint of this range. This index of GTB efficiency will equal unity if fractional reabsorption is constant over the physiologic range of SNGFR and will be zero if Jprox is independent of SNGFR. As flow in the proximal tubule approaches zero, the residence time of a sodium ion in the proximal tubule becomes infinite and its probability of being reabsorbed approaches unity. Conversely, as flow in the tubule approaches infinity, the residence time of a sodium ion in the proximal tubule approaches zero and so must its probability of being reabsorbed. Hence, GTB efficiency is expected to reside somewhere between zero and unity. Measurement error for GTB efficiency in a given nephron is amplified when ΔSNGFR is small, thus contributing outliers that may unduly influence the statistics. As a demonstration of this, kurtosis (a measure of the degree to which outliers cause a distribution to be nonGaussian) for the overall distribution of GTB efficiency was reduced by 90% when 10 out of 136 nephrons were dropped from the analysis based on squared-Studentized residual exceeding unity. The median range of the TGF response for those nephrons was only 4 nl/min, whereas the median range of the TGF response for the remaining nephrons was 17 nl/min. Results are shown in Table 1. Overall, GTB was ∼70% efficient at sustaining the fractional reabsorption over the physiologic range of SNGFR, as represented by the extremes of TGF activity. Commensurate with prior observations in diabetic rats, high salt diet (20) or DFMO (15) tended to lessen GTB efficiency, although no pairwise difference was statistically significant after adjustment for multiple comparisons. DFMO reversed the normal effect of dietary salt on GTB efficiency (P = 0.06 for the ANOVA cross term). Differences in GTB efficiency were not explained by differences in SNGFR. In fact, the strength of the DFMO*Salt interaction was augmented (P < 0.03) when SNGFRmid was made a covariate. This implies that GTB efficiency was not merely improved by raising SNGFR.

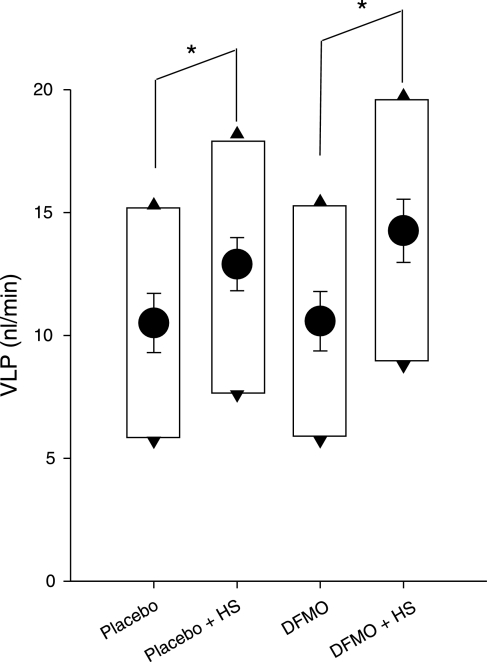

VLP

In open-loop micropuncture, the natural VLP cannot be known precisely because normal TGF is interrupted in the course of collecting the proximal tubular fluid. The dual collection method presently employed provides a broad range of possible VLP in each nephron as depicted by the boxes in Fig. 4. But it has been shown that an average diabetic nephron operates near its TGF midpoint (19). In previous studies, we used a noninvasive optical technique to localize VLP relative to the TGF midpoint under various conditions (13). Even in conditions as radical as acute 3% BW isoncotic plasma volume expansion (13), acute 50% increase imposed on early proximal flow (14), and acute suppression of proximal reabsorption by 50% (18), TGF reset within 60 min so that ambient VLP returned to within 1–2 nl/min of the TGF midpoint. Hence, changes in VLPmid likely reflect similar changes in natural VLP, where we define VLPmid as the average of the late proximal collections during minimal and maximal TGF activation. In placebo- or DFMO-treated rats, high salt diet caused VLPmid to increase by 2–3 nl/min (P = 0.02). A 1 nl/min average increase due to DFMO was not significant.

Fig. 4.

Effects of DS and DFMO on late proximal flow (VLP). Circles, least squares means ± SE for VLPmid. Top and bottom of boxes indicate VLP during zero and full TGF activation, respectively. Micropuncture interrupts TGF, which makes natural VLP indeterminate by the method. Other methods have shown that ambient VLP is generally found within 1–2 nl/min of the VLPmid. *P = 0.02 for 2 nl/min increase in VLPmid with HS. There was no significant effect of DFMO and DFMO did not alter the response to HS.

In DFMO-treated diabetic rats, high salt caused SNGFRmid and VLPmid to increase in parallel in a ratio of 0.68, which is almost exactly the ratio (0.65) predicted for 70% GTB efficiency and quite close to the ratio (0.60) calculated from data recently published to describe effects of high salt diet in nondiabetic Wistar rats (16). Hence, the impact of dietary salt on VLP in the DFMO-treated diabetic rat appears to be commensurate with the impact of dietary salt on VLP in normal rats without diabetes. In contrast, a similar increase in VLP among placebo-treated rats on high salt occurred as SNGFR declined, reflecting a primary decrease in proximal reabsorption.

DISCUSSION

The current study reveals that blocking the ODC-polyamine pathway prevents those previously described strange effects of dietary salt on kidney function in early diabetes referred to as the salt paradox. This is the main new finding. In the following paragraphs, we will delve into the history and the logic of this.

A reciprocal, or paradoxical, relationship between salt intake and GFR has been repeatedly demonstrated in both humans (1, 3) and rats (20, 21, 23) with early diabetes. In seeking to identify the mechanism for this, we used a theoretical construct for the control of GFR. The construct parses all inputs to GFR into two categories: tubular or vascular. By deduction, we then isolated the source of the salt paradox to the tubule segments upstream from the macula densa and confirmed this experimentally (reviewed in Ref. 17). The construct accommodates all known (or yet-to-be-described) feedback mechanisms for connecting GFR to the total body salt and its only assumptions are that there are no hormonal or biochemical pathways unique to diabetes and that diabetes does not alter the fundamental action of any nerve or hormone (for example, diabetes does not convert angiotensin II to a vasodilator). A version of the construct is included in the appendix, wherein is derived a single equation for GFR as a function of dietary salt. This expression defines the conditions that are necessary and sufficient for a salt paradox to occur. The model also explains how GFR, proximal reabsorption, and total body salt become conspicuous nondeterminants of VLP in early diabetes, if distal GTB is constrained by osmotic diuresis.

A distinguishing feature of the salt paradox is that it implies a positive feedback relationship between GFR and the total body salt; to wit, more salt begets lower GFR which begets more salt. But positive feedback is inherently destabilizing and uncommon in body fluid physiology. While there are many parallel and interconnected feedback loops that include both GFR and the total body salt, there is only one of these that can provide the positive feedback necessary to drive the salt paradox. That particular feedback loop combines the inhibitory effect of total body salt on proximal reabsorption with the ensuing TGF response to increased distal delivery.

A further requirement for the salt paradox to occur is that the positive gain of this particular feedback loop must outweigh the sum of all those negative feedback loops with which it competes for control of GFR. In other words, salt signaling through the macula densa must become the overriding influence on GFR. There are only two ways this could occur: 1) the TGF response to a given change in macula densa salt must become more vigorous relative to the sum of all other controlling inputs to GFR or 2) a given change in salt intake must have a greater impact on NaCl reabsorption upstream from the macula densa. In previous studies, we quantified the incremental gain of the TGF response to a unit disturbance in tubular flow and found it to be dampened, rather than increased, by diabetes (19). This doesn't fully eliminate the first option, since TGF could become dominant if all other mechanisms for constricting the afferent arteriole were paralyzed while TGF is spared, but this seems unlikely. We subsequently discovered that diabetes confers a strong inverse dependence of proximal reabsorption on the dietary salt intake. This leads to a large error signal in the macula densa delivery consistent with the second option, which is that the salt paradox results from heightened sensitivity of the proximal tubule to changes in salt intake (20).

The current task is to explain something of the mechanism whereby diabetes causes the proximal tubule to become more sensitive to dietary salt. The present data reveal that ODC is essential for this. Should one have suspected this in the first place? One basis for suspicion is that early diabetic kidney growth, hyperfiltration, and hyperreabsorption all happen to depend on ODC (2, 8, 15), so perhaps the salt paradox does too? A stronger argument for tying ODC to the salt paradox begins by considering the salt balance. Under all conditions, a given increment in salt intake will eventually lead to an equivalent increase in salt excretion, which can only come about through increased GFR, decreased reabsorption upstream from the macula densa, and/or decreased reabsorption downstream from the macula densa. If the GFR fails to increase (or actually decreases as in the salt paradox), then it is left to the nephron segments to generate the exact decrease in overall reabsorption required for the inevitable salt balance. All else remaining equal, the net contribution of a given nephron segment to achieving the salt balance will vary along with the fraction of the overall reabsorptive machinery allocated to that segment. In early diabetes, there is disproportionately high reabsorption upstream from the macula densa (9, 15, 22) and reabsorption upstream from the macula densa assumes a disproportionate role in salt balance (20). Hence, it was reasonable to suspect that the salt paradox, which arises due to the disproportionate role of the diabetic proximal tubule in salt balance, would disappear if the proximal tubule were prevented from assuming that role, and it was previously shown that blocking ODC slows growth of the diabetic tubule and diminishes its influence (15). The alternative explanation, that DFMO might impact the proximal tubule independent of diabetes, is discounted based on prior experiments in nondiabetic rats in which DFMO had no discernable effect (15).

Since hyperglycemia promotes diabetic kidney hypertrophy by an unknown mechanism (12) and stimulates proximal reabsorption via sodium-glucose cotransport (22, 24), efforts were made to equalize blood glucose concentrations among the four experimental groups from the onset of diabetes. To accomplish this, DFMO-treated animals wound up receiving more insulin along the way, in spite of which they had higher blood glucose levels at the time of micropuncture. This raises concern that the salt paradox could have been eliminated in these studies due to confounding effects of insulin and glucose. It is clear that DFMO did not cause the diabetes to be milder, so DFMO could not have eliminated the salt paradox by causing milder diabetes. Furthermore, there was no correlation between dietary salt and insulin dosing, which reduces potential for a confounding influence of insulin on the response to dietary salt. Finally, confounding by blood glucose proved not to account for the apparent effects of DFMO on glomerular filtration or proximal tubular function according to ANCOVA.

The tubular hypothesis of early diabetes invokes negative feedback to make SNGFR subservient to proximal reabsorption. Hence, when proximal reabsorption is high, as it is on a standard diet, there is hyperfiltration; when proximal reabsorption plummets, as it does on a high salt diet, SNGFR declines; and when DFMO prevents the tubule from growing, hyperfiltration fails to emerge. It is assumed, without proof, that this negative feedback from tubule to glomerulus is routed through the macula densa. However, this cannot be explained by the same TGF process that operates from minute-to-minute. For example, a minute-to-minute TGF-mediated increase in SNGFR will shift the TGF operating point leftward toward the shoulder of the TGF curve, whereas TGF actually operates near its inflection point in diabetes (19). Furthermore, the TGF signal is disrupted whenever SNGFR is measured from the proximal tubule, yet proximal tubular micropuncture has been used many times to demonstrate diabetic hyperfiltration. Finally, diabetic hyperfiltration was reported in the adenosine A1 receptor knockout mouse, which lacks a normal TGF system (11). Still, the present data add to a remarkable list of documented situations in which spontaneous or manipulated changes in proximal reabsorption are too great to be caused by associated changes in SNGFR, but could cause those changes in SNGFR.

All else remaining equal, the heightened sensitivity of diabetic proximal tubule to changes in salt intake will shorten the lag time required to restore salt balance, thereby conferring more efficient salt homeostasis. But to leverage this opportunity, the diabetic kidney must reset its TGF response rightward to accommodate increases in distal delivery in response to a greater salt intake. In fact, rightward resetting of TGF is the normal response to a sustained increase in late proximal flow (14, 18). In addition, the high salt- and placebo-treated diabetic kidney transduces a major reduction in proximal reabsorption into a TGF-mediated decline in SNGFR. In the end, this kidney manifests roughly the same increase in VLP when placed on a high salt diet as does the DFMO-treated kidney, or the nondiabetic kidney (16) in which the proximal tubule is insensitive to dietary salt.

It is notable that the high salt diet increased VLP to a nearly identical extent in placebo- and DFMO-treated diabetic animals, but by entirely different mechanisms. This suggests an efficient internal control over VLP that succeeds to the same degree regardless of how the proximal tubule performs. But one can prove, by syllogism, that no special “design” or cybernetic arrangement among the parameters governing SNGFR and proximal reabsorption is necessary to stabilize the effect of dietary salt on VLP. Instead, the regularity with which dietary salt influences steady-state VLP is impervious to events in the glomerulus and proximal tubule because the effect of dietary salt on VLP is completely determined by GTB downstream from the late proximal tubule. The logical proof of this assumes only long-term sodium balance and the existence of GTB in the distal nephron. Notably absent are any assumptions about the glomerulus and proximal tubule. Details are provided in the appendix.

The present data don't provide much detail as to how lessening growth of the diabetic proximal tubule eliminates its hyperresponsiveness to dietary salt. Growth of the diabetic proximal tubule involves hyperplasia, then hypertrophy (10). ODC is mainly elevated during the hyperplastic phase (2, 7), so it may be that DFMO eliminates salt sensitivity because the salt sensitivity resides in new cells. But it is hard to imagine how the nerves and hormones that communicate changes in total body salt to the proximal tubule could be more tightly connected to a newly divided cell than to one that is established and merely hypertrophic. Moreover, we previously showed that the salt paradox cannot be explained by differences in renal nerve activity (1) and we observed that the tonic influence of angiotensin II over proximal reabsorption is already diminished in early diabetes (S. C. Thomson, unpublished studies), such that further suppression by high salt diet is not a viable explanation for the tubular sensitivity to salt. The present findings indicate that kidney hypertrophy is necessary for the salt paradox, but they don't address whether kidney hypertrophy is sufficient to cause a salt paradox. In fact, we recently confirmed that the salt paradox does not occur in compensatory hypertrophy, where changes in proximal reabsorption were fully explained by GTB (4).

In summary, we showed that ODC-mediated growth is necessary for hyperresponsiveness of the proximal tubule to dietary salt and for the paradoxical effect of dietary salt on GFR in early diabetes. This coupling of ODC to tubular salt sensitivity and to the salt paradox adds to the body of evidence that feedback from the proximal tubule is the principal governor of glomerular filtration in early diabetes.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant RO1-DK-56248 and the VA Research Service. H. Mansoury is sponsored by NIH Grant 5T32-DK-007671. C. M. Miracle is supported by NIH Grant K08-DK-078580. T. Rieg was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (TR 1535/3-1).

Acknowledgments

Technical assistance was provided by S. Khang.

APPENDIX

Figure 5 contains a linear systems model for salt balance. The model implies a linear first-order differential equation for changes in total body salt (TBS)

|

|

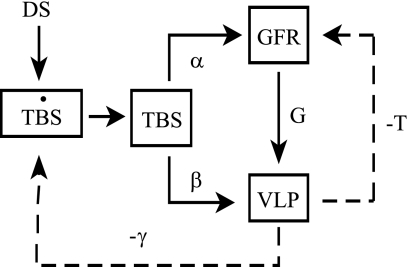

Fig. 5.

System model for response to a change in DS. DS initiates a change in total body salt (TBS), which affects GFR (α) and Jprox (β). Change in VLP is sum of inputs from proximal glomerulotubular balance (G) and β. GFR is stabilized by TGF (−T). VLP affects salt excretion via glomerulotubular balance downstream from the late proximal tubule (γ). The overdot signifies a time derivative. The model parameters α, β, γ, G, and T are all positive. The variables TBS, GFR, and VLP represent changes from the prior equilibrium state.

DS is a change in dietary salt, α and β are direct effects of TBS on GFR and proximal reabsorption, G is GTB in the proximal tubule, T is the TGF response, and γ is GTB downstream from the late proximal nephron.

The solution for TBS is a decaying exponential with time constant, k, that approaches a new steady state where

|

|

|

There are several features of this that are noteworthy. First, the salt paradox will occur if and only if βT > α. In diabetes, the salt paradox occurs due to large β, which corresponds to the 6 nl/min downward shift in the high salt curve (Fig. 2, middle). When β is reduced to zero by DFMO, as indicated by near superposition of GTB curves in Fig. 2, right, the salt paradox disappears.

Second, TGF is “anti-homeostatic” for TBS, which becomes more sensitive to DS as the strength of the TGF response (T) increases. It is the function of TGF to stabilize GFR and VLP and to the degree that VLP is stabilized by TGF, it is prevented from facilitating the salt balance.

Finally, the new steady-state VLP following a given change in DS depends solely on γ. In other words, VLP is independent of GFR and TBS. It is this relationship that allows us to explain why DFMO does not alter the effect of DS on VLP despite disparate effects on SNGFR and proximal reabsorption. At first, it seems counterintuitive that a deterministic expression for VLP would not contain α, β, G, and T since these parameters, along with the variables GFR and TBS, are the physical determinants of VLP. But there is only one value for VLP, VLP = DS/γ, at which the salt excretion matches the salt intake. This makes DS and γ the sole determinants of steady-state VLP. Therefore, without knowing anything about the physiological parameters α, β, G, or T, one can predict that a given DS will cause TBS and GFR to change in some combination that yields the identical VLP, which is determined by γ. Conversely, if a given DS yields the same VLP in two animals, one may conclude that γ is the same in those animals. Hence, it is not an unlikely coincidence that DFMO markedly alters β without changing the ultimate effect of DS on VLP. In fact, the conserved effect of salt on VLP is the only possible outcome if DFMO does not alter GTB in the distal nephron. Furthermore, the fact that DFMO did not alter the effect of DS on VLP implies that it does not affect GTB in the distal nephron.

It is likely that γ is fixed at a high value in diabetes due to osmotic effects of glucose in the collecting duct. A typical hyperphagic diabetic rat on standard rat chow will eat (and excrete) 5 mmol Na and 150 ml water per day (S. C. Thomson, unpublished studies). The same diabetic rat drinking 150 ml of 1% NaCl must excrete 30 mmol Na per day to remain in balance. The rat has ∼60,000 nephrons. If the late proximal flow increases from 10 to 12 nl/min per nephron (as it presently did with high salt diet, irrespective of DFMO), then the total amount of Na delivered beyond the proximal tubule will increase from 130 to 156 mmol/day. This increase of 26 mmol/day delivered out of the proximal tubule is nearly identical to the 25 mmol increase in Na excretion required for sodium balance. In other words, there appears to be no net effect of DS or DFMO on sodium reabsorption downstream from the late proximal tubule in diabetes. It is likely that the high flux of water and glucose osmoles renders the distal nephron unable to compensate for changes in DS, thus relegating inevitable salt balance to the glomerulus and proximal tubule.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Birk C, Richter K, Huang DY, Piesch C, Luippold G, Vallon V. The salt paradox of the early diabetic kidney is independent of renal innervation. Kidney Blood Press Res 26: 344–350, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng A, Munger KA, Valdivielso JM, Satriano J, Lortie M, Blantz RC, Thomson SC. Increased expression of ornithine decarboxylase in distal tubules of early diabetic rat kidneys: are polyamines paracrine hypertrophic factors? Diabetes 52: 1235–1239, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luik PT, Hoogenberg K, Van Der Kleij FG, Beusekamp BJ, Kerstens MN, De Jong PE, Dullaart RP, Navis GJ. Short-term moderate sodium restriction induces relative hyperfiltration in normotensive normoalbuminuric Type I diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 45: 535–541, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mansoury H, Blantz RC, Thomson SC. Compensatory hypertrophy, unlike diabetic hypertrophy, does not manifest a “salt paradox”. J Am Soc Nephrol 18: 171A, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller JA Renal responses to sodium restriction in patients with early diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol 8: 749–755, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mogensen CE Glomerular filtration rate and renal plasma flow in short-term and long-term juvenile diabetes mellitus. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 28: 91–100, 1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen SB, Flyvbjerg A, Gronbaek H, Richelsen B. Increased ornithine decarboxylase activity in kidneys undergoing hypertrophy in experimental diabetes. Mol Cell Endocrinol 86: 67–72, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pedersen SB, Flyvbjerg A, Richelsen B. Inhibition of renal ornithine decarboxylase activity prevents kidney hypertrophy in experimental diabetes. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 264: C453–C456, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollock CA, Lawrence JR, Field MJ. Tubular sodium handling and tubuloglomerular feedback in experimental diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 260: F946–F952, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasch R, Norgaard JO. Renal enlargement: comparative autoradiographic studies of 3H-thymidine uptake in diabetic and uninephrectomized rats. Diabetologia 25: 280–287, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sallstrom J, Carlsson PO, Fredholm BB, Larsson E, Persson AE, Palm F. Diabetes-induced hyperfiltration in adenosine A(1)-receptor deficient mice lacking the tubuloglomerular feedback mechanism. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 190: 253–259, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stackhouse S, Miller PL, Park SK, Meyer TW. Reversal of glomerular hyperfiltration and renal hypertrophy by blood glucose normalization in diabetic rats. Diabetes 39: 989–995, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomson SC, Blantz RC. Homeostatic efficiency of tubuloglomerular feedback in hydropenia, euvolemia, and acute volume expansion. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 264: F930–F936, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson SC, Blantz RC, Vallon V. Increased tubular flow induces resetting of tubuloglomerular feedback in euvolemic rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 270: F461–F468, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomson SC, Deng A, Bao D, Satriano J, Blantz RC, Vallon V. Ornithine decarboxylase, kidney size, and the tubular hypothesis of glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes. J Clin Invest 107: 217–224, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thomson SC, Deng A, Wead L, Richter K, Blantz RC, Vallon V. An unexpected role for angiotensin II in the link between dietary salt and proximal reabsorption. J Clin Invest 116: 1110–1116, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomson SC, Vallon V, Blantz RC. Kidney function in early diabetes: the tubular hypothesis of glomerular filtration. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 286: F8–F15, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson SC, Vallon V, Blantz RC. Reduced proximal reabsorption resets tubuloglomerular feedback in euvolemic rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R1414–R1420, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vallon V, Blantz RC, Thomson S. Homeostatic efficiency of tubuloglomerular feedback is reduced in established diabetes mellitus in rats. Am J Physiol Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 269: F876–F883, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vallon V, Huang DY, Deng A, Richter K, Blantz RC, Thomson S. Salt sensitivity of proximal reabsorption alters macula densa salt and explains the paradoxical effect of dietary salt on glomerular filtration rate in diabetes mellitus. J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 1865–1871, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vallon V, Kirschenmann D, Wead LM, Lortie MJ, Satriano J, Blantz RC, Thomson SC. Effect of chronic salt loading on kidney function in early and established diabetes mellitus in rats. J Lab Clin Med 130: 76–82, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vallon V, Richter K, Blantz RC, Thomson S, Osswald H. Glomerular hyperfiltration in experimental diabetes mellitus: potential role of tubular reabsorption. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 2569–2576, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vallon V, Wead LM, Blantz RC. Renal hemodynamics and plasma and kidney angiotensin II in established diabetes mellitus in rats: effect of sodium and salt restriction. J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1761–1767, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Weinstein AM, Weinbaum S, Duan Y, Du Z, Yan Q, Wang T. Flow-dependent transport in a mathematical model of rat proximal tubule. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 292: F1164–F1181, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]