Abstract

Taste stimuli are detected by taste receptor cells present in the oral cavity using diverse signaling pathways. Some taste stimuli are detected by G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) that cause calcium release from intracellular stores, whereas other stimuli depolarize taste cells to cause calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs). Although taste cells use two distinct mechanisms to transmit taste signals, increases in cytosolic calcium are critical for normal responses in both pathways. This creates a need to tightly control intracellular calcium levels in all transducing taste cells. To date, however, the mechanisms used by taste cells to regulate cytosolic calcium levels have not been identified. Studies in other cell types have shown that mitochondria can be important calcium buffers, even during small changes in calcium loads. In this study, we used calcium imaging to characterize the role of mitochondria in buffering calcium levels in taste cells. We discovered that mitochondria make important contributions to the maintenance of resting calcium levels in taste cells by routinely buffering a constitutive calcium influx across the plasma membrane. This is unusual because in other cell types, mitochondrial calcium buffering primarily affects large evoked calcium responses. We also found that the amount of calcium that is buffered by mitochondria varies with the signaling pathways used by the taste cells. A transient receptor potential (TRP) channel, likely TRPV1 or a taste variant of TRPV1, contributes to the constitutive calcium influx.

INTRODUCTION

The detection of gustatory stimuli depends on the activation of taste receptor cells located in taste buds within the oral cavity. Activated taste receptors on the apical membrane of taste cells initiate transduction pathways that ultimately transmit signals to afferent gustatory neurons. Taste cells use two distinct signaling pathways to mediate their communication to the nervous system: 1) calcium influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs), which causes vesicular neurotransmitter release or 2) G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR)-dependent second messenger pathways that activate a calcium-dependent nonvesicular mechanism to release the neurotransmitter, ATP (Clapp et al. 2004, 2006; DeFazio et al. 2006; Finger et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2007; Romanov et al. 2007; Tomchik et al. 2007). Both signaling mechanisms depend on increasing cytosolic calcium to produce normal synaptic signals. Hence all transducing taste cells must tightly regulate intracellular calcium levels. Currently, the role of buffering mechanisms to control cytosolic calcium levels in taste cells has not been described.

In addition to its role in ATP production, mitochondria make significant contributions to the regulation cytosolic calcium in many cells (Babcock and Hille 1998; Babcock et al. 1997; Budd and Nicholls 1998; Duchen 2000a,b) and has important roles in the regulation of synaptic activity in neurons (Medler and Gleason 2002; Peng 1998; Sen et al. 2007; Tang and Zucker 1997). Mitochondrial calcium buffering is important during continuous calcium-induced calcium release in submandibular acinar cells (Kopach et al. 2008), directly modulates agonist-induced calcium signals (Johnson et al. 2002; White and Reynolds 1995), and can functionally interact with calcium stores to regulate cytosolic calcium signals (Landolfi et al. 1998; Malli et al. 2005).

To assess the physiological effects of mitochondrial calcium transport in taste cells, we isolated mouse taste receptor cells and recorded cytosolic calcium changes with fura 2-AM. We used the protonophore p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP) to dispel the large negative membrane potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane and greatly reduce the driving force for calcium to enter the mitochondria through the calcium uniporter (Boitier et al. 1999; Ricken et al. 1998). We found that in unstimulated taste cells, disabling the mitochondrial calcium transport caused an increase in cytosolic calcium levels. These results were surprising because many cell types primarily use mitochondrial calcium buffering to regulate stimulus-induced calcium loads, and its impact on calcium levels in unstimulated cells is typically minimal (Babcock et al. 1997; Budd and Nicholls 1996; Kim et al. 2005; Montero et al. 2000; Rizzuto et al. 2000; Rutter et al. 1993; Svichar et al. 1997; White and Reynolds 1995). Our results show that, in taste cells, mitochondria routinely contribute to the maintenance of low cytosolic calcium levels even in the absence of a stimulus.

METHODS

Taste receptor cell isolation

Adult C57/Bl6 mice were used in the experiments. Animals were cared for in compliance with the University at Buffalo Animal Care and Use Committee. Mouse taste receptor cells were isolated from lingual epithelium as previously described (Medler et al. 2003). Briefly, animals were killed with CO2 and cervical dislocation. Tongues were removed from animals followed by injection under the lingual epithelium with 100 μl of an enzymatic solution containing 0.6 mg of collagenase B (Roche, Indianapolis, IN), 3 mg of dispase II (Roche), and 1 mg of trypsin inhibitor (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) per milliliter of Tyrode's solution (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 3 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, and 1 mM pyruvic acid, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 1 mM NaOH or 1 mM HCl). Tongues were incubated in oxygenated Tyrode's solution for 20 min before the epithelium was peeled from the connective and muscular tissue. The peeled epithelium was incubated for 30 min in Ca2+-free Tyrode's solution (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 2 mM BAPTA, 10 mM glucose, and 1 mM pyruvic acid, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 1 mM NaOH or 1 mM HCl) before foliate and circumvallate taste cells were removed with a capillary pipette using gentle suction.

Calcium imaging

Isolated taste receptor cells were loaded for 40 min with 2 μM fura 2-AM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) containing the nonionic dispersing agent Pluronic F-127 (Invitrogen) as previously described (Hacker et al. 2008). Loaded cells were visualized using an Olympus IX71 microscope with a 40× oil immersion lens, and images were captured using a Sensicam QE camera (Cooke, Romulus, MI). Excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm were used with an emission wavelength of 510 nm.

During experiments, cells were kept under constant perfusion, and images were collected every 4 s using Imaging Workbench 5.2 (Indec Biosystems, Santa Clara, CA). Faster capture rates resulted in damage to the cells as shown by a loss in the stability of the baseline calcium values. Because our sampling rate was relatively slow, a faster sampling (0.5 s) was done on a subset of cells to determine whether we were accurately measuring the peak fluorescence increases. There was no difference in the peak amplitude of the response to stimulus in taste cells when images were captured every 4 s and when the images were captured every 0.5 s (n = 18, P = 0.12), indicating that peak fluorescence responses could accurately be measured at the slower sampling rate.

Taste cells were plated into a laminar flow chamber and stimuli were rapidly perfused across the cells using a gravity flow perfusion system. Control experiments determined that there is an ∼3-s delay between the onset of stimulus application and the stimulus contact with the target cell in our experimental setup. Stimulus application time is reported in the figures with no compensation for the delay caused by stimulus delivery. Experiments were plotted and analyzed using OriginPro 7.5 software. Calcium increases were calculated as [(peak − baseline)/baseline] × 100 and were reported as percent increases over baseline.

Calcium concentration conversions

Calcium levels were collected as a ratio of fluorescence intensities. Fluorescence values were calibrated using the Fura-2 Calcium Imaging Calibration kit (Invitrogen). The effective dissociation constant, Kd, was calculated to be 253 nM, and calcium concentrations were determined using the formula outlined by Grynkiewicz et al. (1985)

|

|

with R as the ratio of fluorescence collected after exciting the cells at 340 and 380 nm. These reported values are considered to be approximate as some variability may occur between preparations. Most taste cells had baseline calcium values ranging from 50 to 150 nM. Taste cells with baseline values >200 nM were deemed to be unhealthy and were not included in analysis.

Most statistical comparisons were made using either an independent or paired Student's t-test with a limit of significance at P < 0.05. A one-way ANOVA with the Bonferroni's post hoc analysis was performed when comparing multiple samples.

Solutions

All solutions were bath applied using a gravity flow perfusion system (Automate Scientific, San Francisco, CA) and laminar flow perfusion chambers (RC-25F, Warner Scientific, Hamden, CT). Mitochondrial calcium transport in taste cells was disabled using the protonophore p-trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP, Tocris, Ellisville, MO). In addition to FCCP, MRS1845, SKF96365, and thapsigargin were all purchased from Tocris. All other drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma. Calcium-free Tyrode's (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, and 1 mM pyruvic acid, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 1 mM NaOH or 1 mM HCl), 8 mM CaCl2 Tyrode's (140 mM NaCl, 5 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 8 mM CaCl2, 10 mM HEPES, 10 mM glucose, and 1 mM pyruvic acid, adjusted to pH 7.4 with 1 mM NaOH or 1 mM HCl), hi KCl solution (Tyrode's with 50 mM NaCl replaced by 50 mM KCl), and a bitter mixture (10 mM denatonium benzoate and 500 μM cycloheximide) were used in some experiments.

Identification of taste cells and their calcium signaling pathways

Taste receptor cells were easily identified by their characteristic morphology (Hacker et al. 2008). The calcium signaling mechanisms expressed by taste cells were identified using two different stimuli. The presence of VGCCs was shown by the cell's responsiveness to a 10-s application of 50 mM KCl (see Solutions). Dependence on calcium release was determined by the cell's responsiveness to a 20-s application of a bitter mixture (see Solutions). We have previously shown that responsiveness to these two types of stimuli are caused by calcium influx for VGCCs and calcium release from internal stores for the bitter mixture (Hacker et al. 2008). Since we are discussing these taste cells in terms of how they handle their calcium loads, i.e., taste cells that have a very large calcium load because of calcium influx through VGCCs versus taste cells that rely on calcium release from internal stores in response to taste stimuli, we will refer to these taste cells as taste cells with calcium release or with calcium influx/VGCC.

Specificity of FCCP

We chose to use a protonophore to disrupt mitochondrial calcium transport because they have been shown to be very effective in inhibiting mitochondrial calcium elevations in intact cells (Boitier et al. 1999; David and Barrett 2000; Herrington et al. 1996; Kim et al. 2005; Kopach et al. 2008; Landolfi et al. 1998). We used FCCP to dissipate the membrane potential across the inner mitochondrial membrane because it is fast-acting and readily reversible. In numerous other studies, low concentrations (1–5 μM) of FCCP have been shown to exclusively inhibit mitochondrial calcium uptake (Babcock et al. 1997; David and Barrett 2000; Friel and Tsien 1994; Malli et al. 2003, 2005; Werth and Thayer 1994; White and Reynolds 1995, 1997). In addition, we independently inhibited mitochondrial calcium transport with antimycin A and oligomycin to test for the specificity of FCCP (Colegrove et al. 2000b) (see results).

RESULTS

Responses to disabling mitochondrial calcium transport are variable

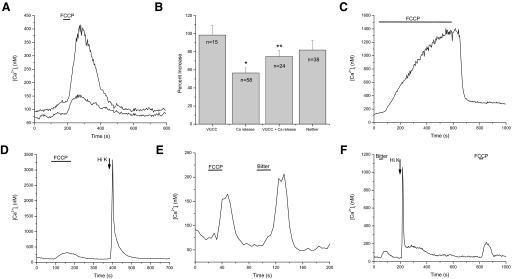

Isolated taste receptor cells were loaded with fura 2-AM and changes to calcium levels were measured when 1 μM FCCP was applied. Baseline calcium levels varied between 39 and 197 nM, with an average value of 104 nM (SD = 48 nM, n = 163), which agrees with other studies in taste cells (Baryshnikov et al. 2003; Ogura et al. 1997). We found that applying FCCP in the absence of any other stimulus caused cytosolic calcium elevations in 94% of the taste cells tested (n = 536 cells, 79 mice); however, the response amplitude was highly variable between taste cells. Figure 1A shows the intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) increases of two different taste receptor cells in response to a 30-s application of FCCP. One cell increased its [Ca2+]i levels 80% over baseline levels, whereas the second taste cell had a 307% increase over baseline. These differences are reflective of what was seen across all taste cells tested; exposure to FCCP caused calcium increases that ranged from 32 to 826% of resting calcium levels (maximum peak value = 1,463 nM), with an overall average FCCP-dependent calcium increase that was 215% of baseline values (mean = 328 nM, SD = 248 nM, n = 163).

FIG. 1.

p-Trifluoromethoxy-phenylhydrazone (FCCP) application causes a variable change in cytosolic calcium levels in taste cells. A: application of the protonophore, FCCP (black bar), reversibly eliminated the mitochondria's ability to buffer calcium. Application of FCCP caused increases in cytosolic calcium levels in 94% of previously unstimulated taste cells (n = 536). The amplitude of the response varied among different cells as shown here. Two taste cells simultaneously stimulated by FCCP evoked very different amplitudes in their calcium responses. B: amplitudes of the FCCP-induced calcium responses varied significantly across different populations of taste cells. Taste cells that release calcium from internal stores in response to bitter stimuli but lack voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) had significantly smaller FCCP-dependent calcium responses compared with taste cells with VGCCs (P = 0.0009) or taste cells that were not responsive to taste stimuli and did not express VGCCs (labeled “neither,” P = 0.02). Taste cells that responded to bitter stimuli (via calcium release from internal stores) and have VGCCs generated significantly smaller calcium elevations in response to FCCP compared with taste cells that only have VGCCs (P = 0.046). No other significant differences in the FCCP-dependent calcium responses were found. C: prolonged FCCP application (9 min) caused a sustained increase in cytosolic calcium that was maintained until FCCP was washed out and the mitochondria were able to buffer [Ca2+]i. D: an example FCCP-induced calcium elevation in a taste cell that expresses VGCCs as measured by its sensitivity to high KCl (50 mM). E: an example FCCP-induced calcium elevation in a taste cell that releases calcium from internal stores in response to bitter stimuli. F: an example FCCP-induced calcium elevation in a taste cell that releases calcium from internal stores in response to bitter stimuli and expresses VGCCs.

The variation in the amplitude of the FCCP-induced calcium increase was not dependent on the length of time cells were exposed to FCCP. We calculated the average percent increase of calcium over baseline in response to a range of FCCP exposure times (20–150 s). Analysis with a one-way ANOVA and a post hoc Bonferroni's test found no significant differences between any of these exposure times (data not shown, P = 0.101). Therefore a maximal peak amplitude response could be achieved by a 20-s FCCP exposure, and the amplitude of the response was not related to the length of time the mitochondria were disabled. Similar analysis of different concentrations of FCCP (1–10 μM) also found no significant differences in the amplitude of the responses (data not shown, P = 0.17). We also compared the amplitude of the FCCP response in taste cells isolated from the circumvallate papillae to taste cells from the foliate papillae but found no significant differences between the papillae types (data not shown, P = 0.337).

Amplitude of the FCCP-dependent calcium increase varies significantly across taste cell type

We next determined whether any of the variability in the amplitude of the FCCP-induced calcium elevations correlated with the calcium signaling mechanisms used by the taste cells. We have recently shown that activating different calcium signaling mechanisms in taste cells generates significantly different calcium responses (Hacker et al. 2008). To correlate FCCP responses with calcium signaling mechanisms expressed in taste cells, we identified the presence of these signaling mechanisms as previously described (Hacker et al. 2008). The presence of VGCCs was determined by the taste cell's responsiveness to 50 mM KCl (example in Fig. 1D), whereas taste cells that depend on calcium release from internal stores were identified by their responsiveness to a mixture of two bitter compounds (example in Fig. 1E). Since we did not test cells for their responsiveness to all tastants that depend on calcium release from internal stores (Zhang et al. 2003) and only used bitter compounds, the reported values may not be reflective of the FCCP-induced calcium responses in all taste cells that use the phospholipase C (PLC)β signaling pathway. However, the goal of these experiments was to determine whether there were any differences in the amplitude of the FCCP-dependent calcium elevations that correlated with the calcium influx mechanisms or calcium release mechanisms expressed in taste cells.

We compared the effects of FCCP on cytosolic calcium levels in taste cells that express VGCCs and taste cells that depend on calcium release from internal stores to elicit a taste response. We found that the amplitude of the FCCP-induced calcium elevation was significantly smaller in taste cells that use calcium release from internal stores and lack VGCCs compared with taste cells that express VGCCs (Fig. 1B; P = 0.0009). We have also recently identified a population of taste cells that have stimulus-evoked calcium release from internal stores through a PLC signaling pathway but also express VGCCs (Hacker et al. 2008), and we included these cell types in our analysis as well (see example in Fig. 1F). The average amplitude of the FCCP-dependent calcium elevation in taste cells with VGCCs was significantly greater than the FCCP-induced calcium increase in taste cells that had both VGCCs and calcium release from internal stores (Fig. 1B; P = 0.046), but this difference was much less pronounced. The average amplitude of the FCCP-induced calcium response in taste cells that did not express VGCCs and were not responsive to bitter taste stimuli (labeled “neither” in Fig. 1B) was not significantly different from taste cells with VGCCs or taste cells with both VGCCs and calcium release from stores. However, these taste cells did generate significantly larger FCCP-dependent calcium responses compared with taste cells that depended solely on calcium release from internal stores (Fig. 1B; P = 0.02). These data indicate that, although most taste cells depend on mitochondria to maintain low basal calcium levels, some of the variability in the amplitude of the calcium response to FCCP correlates with the presence of specific calcium signaling pathways in the taste cells.

We reasoned that the FCCP-induced calcium elevation might be caused by a small amount of calcium being stored in the mitochondria because this has been reported in other cell types (Babcock et al. 1997; Montero et al. 2001; Werth and Thayer 1994; White and Reynolds 1997). The variability in the response peak amplitude could be caused by the number of mitochondria per taste cell and/or the amount of calcium stored per mitochondria. If these FCCP-dependent calcium elevations were caused by depletion of mitochondrial calcium stores, a prolonged FCCP application should exhaust the calcium stored in the mitochondria, and cytosolic calcium elevations would return to baseline levels after this depletion, even if FCCP were still present. We found that when FCCP was applied to taste cells for a long time (+120 s), elevated calcium levels were sustained until FCCP was washed out, and mitochondria were once again able to buffer calcium (Fig. 1C; n = 59). This continuous elevation of calcium suggested one of two possibilities: FCCP causes elevated cytosolic calcium levels within the taste cell that are not caused by the release of mitochondrial calcium stores or if mitochondria are a calcium source, they are not the sole source of calcium causing these cytosolic calcium elevations.

FCCP responses are not caused by ATP depletion or cytosolic acidification in taste cells

Since FCCP dispels the negative membrane potential on the inner mitochondrial membrane, it affects ATP synthesis in addition to mitochondrial calcium transport. Therefore it was possible that the FCCP-induced calcium elevation that we were measuring was a result of inhibiting ATP synthesis. Control experiments were performed to determine whether the increase in [Ca2+]i was caused by FCCP inhibiting other mitochondrial functions. We found that neither antimycin A (Fig. 2A, applied for 2 min, n = 15), an electron transport chain inhibitor, nor oligomycin (Fig. 2B, applied for 2.5 min, n = 20), an ATPsynthase inhibitor, mimicked the effects of FCCP. If inhibiting mitochondrial function for 20–30 s caused a rapid loss of ATP in taste cells that generated a subsequent rise in cytosolic calcium, inhibiting the electron transport chain or ATPsynthase for ≥2 min should have comparable effects on cytosolic calcium (Colegrove et al. 2000a; Medler and Gleason 2002). However, antimycin A and oligomycin did not individually affect baseline calcium values in taste cells. This is not surprising because it has been shown in sympathetic ganglia that protonophores do not significantly affect ATP/ADP ratios for ≥23 min (Peng 1998). This is in contrast to the rapid depletion of the ATP/ADP ratios caused by protonophores in cultured cerebellar granule cells (Budd and Nicholls 1996). The effect of ATP depletion on the cytosolic calcium levels in granule cells was very small compared with the effect of FCCP on the cytosolic calcium levels in taste cells, suggesting that ATP depletion does not cause large changes in cytosolic calcium, even in cells that lose ATP quickly when FCCP is applied.

FIG. 2.

FCCP-dependent calcium responses are not caused by ATP depletion or disabling electron transport. A: antimycin A (1 μM, AM-A) did not affect cytosolic calcium levels, whereas FCCP application caused an increase in calcium levels that returned to baseline levels when FCCP was washed out. B: oligomycin (1 μM, OG) did not change cytosolic calcium levels, whereas FCCP application increased cytosolic calcium that returned to baseline levels when FCCP was washed out. C: FCCP-induced calcium elevations could be mimicked with a co-application of antimycin A (1 μM) and oligomycin (1 μM). However, it took much longer to wash out the inhibitors and for calcium levels to return to baseline. D: sodium orthovanadate (1 mM, VAN) did not affect baseline calcium levels in taste cells and did not significantly impact FCCP-dependent calcium increases (E, n = 17, P = 0.22). F: co-application of oligomycin with FCCP did not significantly affect the FCCP-induced calcium increase (n = 10, P = 0.15).

To test for the specificity of FCCP, mitochondrial calcium transport was independently inhibited by treating cells with antimycin A and oligomycin. Co-application of antimycin A and oligomycin generated a cytosolic calcium increase that was comparable to the FCCP-induced calcium elevation, but the inhibitors did not wash out very quickly, and the cell was slow to recover (Fig. 2C). These data signify that the FCCP-evoked response is caused by its effect on the mitochondria since it can be mimicked by inhibiting mitochondrial enzymes that normally contribute to the generation of the negative mitochondrial membrane potential (Colegrove et al. 2000a; Malli et al. 2003, 2005; Nicholls and Budd 2000).

If FCCP causes a rapid ATP depletion in taste cells, it could affect the activity of calcium ATPases present at the plasma membrane and on internal stores, which could potentially increase cytosolic calcium. To determine whether inhibition of ATPase activity was responsible for the FCCP-dependent calcium elevations being measured, we applied a high concentration of the P-type ATPase inhibitor, sodium orthovanadate (1 mM), to taste cells. At this concentration, there should be complete inhibition of any calcium ATPases present (Bowman 1983; Bowman et al. 1981; Koyama 1999; Ueno et al. 2000). If inhibiting ATPase activity was the cause of the FCCP-induced elevation in cytosolic calcium, sodium orthovanadate should cause an increase in cytosolic calcium when applied to taste cells. If the measured FCCP response was due to ATP depletion that caused inhibition of calcium ATPases, orthovanadate should inhibit the FCCP response because the ATPases would already be nonfunctional. Application of sodium orthovanadate did not affect baseline calcium levels and did not significantly impact FCCP-dependent calcium elevations (Fig. 2, D and E; paired Student's t-test, n = 17, P = 0.22). Based on these results, we concluded that the FCCP-dependent calcium elevations in taste cells were not caused by inhibiting ATP production.

It has also been reported that the collapse of the inner mitochondrial membrane potential can result in active ATP consumption by the F0-F1 ATP synthase. Therefore FCCP could increase the rate of ATP depletion beyond what normally occurs when ATP is not being actively produced by the mitochondria (Budd and Nicholls 1996; Duchen 2000b). To ensure that we were not measuring a cytosolic calcium change caused by active ATP consumption by the F0-F1 ATP synthase, we inhibited the F0-F1 ATP synthase with oligomycin while we applied FCCP. If FCCP caused the F0-F1 ATP synthase to actively consume ATP and cause an elevation of cytosolic calcium, FCCP and oligomycin together should not cause any increases in calcium. However, there was no difference in the magnitude of the FCCP-induced calcium increase when the F0-F1 ATP synthase was disabled (Fig. 2F; n = 10, P = 0.15), confirming that ATP depletion is not causing the FCCP-dependent cytosolic calcium elevations.

Since FCCP is a protonophore, it can acidify the cytosol, which could potentially affect cytosolic calcium levels (Tretter et al. 1998; Wang et al. 1995). To determine whether cytosolic acidification mimicked the calcium responses that we were measuring, we applied nigericin to taste cells. Nigericin permits the electroneutral exchange of K+ for H+ ions across the plasma membrane and causes cytosolic acidification (Bulychev and Vredenberg 1976; Nicholls 2006). We found that nigericin alone did not alter baseline calcium values or the FCCP-induced calcium increase even though it does cause some acidification of the cytosol (Supplemental Fig. S1; n = 13, P = 0.59).1

From these experiments, we concluded that the FCCP-induced calcium increases were not caused by ATP depletion or cytosolic acidification. Instead, FCCP is disrupting calcium transport by the mitochondria, which results in cytosolic calcium elevations within taste cells. Given the minimal role for mitochondrial calcium, we began testing the hypothesis that the FCCP-induced calcium elevations depend on additional sources of calcium besides the mitochondria.

Mitochondria can compensate for calcium buffering by sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase pumps

Since elevated cytosolic calcium is maintained as long as the mitochondria are not functional (Fig. 1C), we predicted that nonmitochondrial calcium sources are contributing to this calcium increase. There are two potential sources for this calcium: calcium flux across the plasma membrane or a constitutive efflux from internal calcium stores. We initially hypothesized that the mitochondria were buffering a calcium leak from internal stores because many studies have shown an active relationship between the mitochondria and calcium stores in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Arnaudeau et al. 2001; Csordas and Hajnoczky 2001; Csordas et al. 2001 1999; Hajnoczky et al. 1999, 2000a,b; Jackson and Thayer 2006; Landolfi et al. 1998; Malli et al. 2005; Sen et al. 2007). If mitochondria constitutively buffer a calcium leak from internal stores, when the mitochondria are disabled, this “unbuffered” calcium would result in the elevated cytosolic calcium levels that we were detecting. Depletion of the internal calcium stores would remove the calcium source that was contributing to the FCCP-induced calcium response. This should result in either a significantly smaller cytosolic calcium elevation or no calcium elevation when FCCP was added. To test our hypothesis, we disabled the sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) pumps with 2 μM thapsigargin and measured the impact on mitochondrial calcium buffering (Fig. 3). We found that the amplitude of the FCCP-induced calcium response did not significantly change (n = 24, P = 0.38; Fig. 3B) after the addition of thapsigargin (TG), whereas the duration of the FCCP-induced calcium response significantly increased (n = 23, P = 0.00003; Fig. 3C). We drew two conclusions based on these data: 1) the FCCP-evoked calcium response is not solely caused by calcium leak from internal stores and 2) that SERCA pumps normally contribute to the buffering of cytosolic calcium but if the SERCA pumps are not functional, then the mitochondria can compensate for the loss of ER calcium buffering and still maintain appropriately low cytosolic calcium levels.

FIG. 3.

FCCP-dependent calcium elevations increase when sarco-endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA) pumps are disabled. A: FCCP-dependent calcium increases were larger after 2 μM thapsigargin (TG) application (3 min). B: measures of the peak amplitude of the FCCP-dependent calcium increase did not significantly change (n = 24, P = 0.38) after SERCA pumps were disabled with thapsigargin. C: the duration of the FCCP-induced calcium response significantly increased after SERCA pumps were disabled (n = 23, P = 0.00003).

We also found that the applying TG to taste cells did not always evoke a transient elevation in cytosolic calcium as has been reported previously in taste cells (Ogura et al. 2002). Of the taste cells we tested, one half of the cells (n = 12 of 24) responded to TG with an elevation in cytosolic calcium (see Fig. 7A), whereas TG had a very small or no effect on the baseline calcium levels of the other taste cells (Fig. 3A). Ogura et al. (2002) measured the effect of TG on gustducin expressing taste cells that do not express VGCCs (Medler et al. 2003), and there may be some cell-specific signaling mechanisms that result in different cellular responses to TG. We did not find any significant differences in the amplitudes of the FCCP-induced calcium elevations in either taste cells that had a transient calcium increase to TG (n = 12, P = 0.61) or in taste cells that did not display a transient calcium elevation in response to TG (n = 12, P = 0.47). In addition, there were no significant differences between the amplitude of the FCCP responses in these two groups of taste cells (n = 12, P = 0.198). In the context of our experiments, we did not determine whether the TG responses correlated with the presence of a particular calcium signaling pathway such as VGCCs or calcium release from stores. Future studies are needed to quantify those differences.

FIG. 7.

Mitochondria buffer calcium leaks across the plasma membrane and from internal stores. A: FCCP-induced calcium elevations were greatly attenuated in calcium-free external solution. Thapsigargin greatly reduced the FCCP-induced calcium elevations in calcium-free external solution. B: enlarged portions of the graph in A that correspond to FCCP applications in calcium-free external solution. The amplitude of the peak response in calcium free (see arrows) was reduced after the taste cell had been exposed to thapsigargin and most of the calcium stores had been depleted, showing that the calcium elevation measured in calcium-free external solution depends on internal calcium stores.

VGCCs are not contributing to FCCP-induced responses

We next looked at external calcium to see if it was acting as the source for the sustained FCCP-induced calcium elevation we were measuring. It has been reported that FCCP alone induces small cytosolic calcium elevations in some cell types (Kubota et al. 2003; White and Reynolds 1995). Since FCCP is a protonophore, it allows H+ ions to cross the plasma membrane toward their Nernst electrochemical equilibrium potential. In some cells, this H+ ion influx depolarizes the plasma membrane sufficiently to activate VGCCs and increase intracellular calcium. In these studies, blocking VGCCs inhibited the FCCP-induced calcium elevation (Kubota et al. 2003; White and Reynolds 1995). To determine whether VGCCs are directly responsible for the FCCP-induced calcium elevations in taste cells, we compared FCCP-dependent calcium responses in the presence and absence of cadmium, a VGCC blocker (Beam and Knudson 1988; Hacker et al. 2008). Cadmium (200 μM) did not significantly affect the FCCP-dependent calcium elevation (Fig. 4, A and B; n = 24, P = 0.07), and we concluded that the FCCP-dependent increases in cytosolic calcium were not caused by VGCC activity. In addition, only a subset of taste receptor cells express VGCCs, but FCCP caused a rise in intracellular calcium in most taste cells, further substantiating that the FCCP-dependent calcium increases are not caused by activated VGCCs. To determine whether VGCCs were contributing to the FCCP-dependent calcium increases in the subset of taste cells that express VGCCs, we compared the amplitude of the FCCP response in cells that express these channels (as measured by a calcium response to 50 mM KCl) to the amplitude of the FCCP response in taste cells that were not sensitive to 50 mM KCl. This analysis consisted of combining the data in Fig. 1C into two groups: taste cells with VGCCs and taste cells without VGCCs. We used a Student's t-test to determine whether any significant difference in the amplitude of the FCCP response was present between these two groups. Figure 4C shows that no significant differences in the amplitude of the FCCP responses existed (P = 0.103) between the two populations of taste cells, which confirms that VGCCs are not responsible for the FCCP-induced calcium response. The significant differences seen in Fig. 1B seem to correlate with the cell's dependence on calcium release from internal stores in response to stimuli. These data suggest that interactions between the mitochondria and ER calcium stores may differ depending on the calcium signaling pathway used.

FIG. 4.

VGCCs do not contribute to the FCCP-induced calcium elevation. A: applying the VGCC channel blocker cadmium chloride (200 μM) did not significantly affect the FCCP-induced calcium response. B: measurements of the FCCP-induced peak values found no significant differences in the presence of Cd+ compared with FCCP alone (n = 24, P = 0.07). C: comparisons of the FCCP-dependent calcium elevations in taste cells that respond to high KCl and taste cells that were not responsive to 50 mM KCl found no significant differences in the amplitudes of the FCCP-induced calcium elevations between these 2 groups (n = 39, P = 0.103).

Mitochondria buffer a constitutive calcium influx across the plasma membrane

Since internal calcium stores and VGCCs did not seem to be making significant contributions to the FCCP-induced calcium elevation, we studied the possibility that the mitochondria routinely buffer an influx of external calcium across the plasma membrane. To determine whether external calcium contributes to the FCCP-induced calcium increase, FCCP was applied to taste cells with no external calcium present (Fig. 5). In 49% of taste cells tested (n = 84), FCCP responses were reduced in calcium-free external (Fig. 5A), whereas 36% of the FCCP-dependent responses were completely abolished (Fig. 5B). To ensure that the reduction/abolition of the FCCP-induced calcium response seen in Fig. 5, A and B, was not simply caused by a history of elevated calcium having an effect on subsequent responses, we also applied FCCP in calcium-free external solution first and obtained similar results (Fig. 5C; n = 18). Average FCCP-dependent peak calcium values were 165 nM in calcium-free external solution compared with the average peak value of 355 nM in normal Tyrode's. This was a 54% decrease in the amplitude of the FCCP-induced peak in cytosolic calcium when external calcium was removed. Since the absence of external calcium either abolished or significantly reduced the FCCP-dependent response (Fig. 5D; n = 12, P = 0.025), we concluded that external calcium contributes to the elevated cytosolic calcium levels that occur when mitochondrial calcium buffering is disabled.

FIG. 5.

Mitochondria buffer a calcium influx across the plasma membrane. A: FCCP application caused a large increase in [Ca2+]i levels that returned to baseline when FCCP was washed out. The amplitude of the [Ca2+]i elevation decreased when no external calcium was present, although some increase in calcium levels was still evident. B: in other taste cells, FCCP effects were abolished when no external calcium was present. C: when FCCP was initially applied in calcium-free external solution, the amplitude of the response was smaller compared with a subsequent FCCP-induced calcium elevation that was elicited in normal external solution. D: the amplitude of the FCCP-evoked calcium response was significantly reduced when no external calcium was present (n = 12, P = 0.025).

In most, but not all, of the taste cells we tested (77%, n = 107), removing external calcium caused a significant reduction in baseline calcium levels of ∼54% (n = 48, average baseline calcium was 120 nM in normal Tyrode's and 55 nM in calcium-free Tyrode's, P < 0.00001; cf. Fig. 5, B and C, to Fig. 5A). This percent reduction is comparable to the percent reduction in the amplitude of the FCCP-induced peak response. These data suggest that maintenance of normal cytosolic calcium levels in taste cells depends on the presence of external calcium. There seems to be a constitutive calcium influx across the plasma membrane that is regulated at least in part by mitochondrial calcium buffering. To begin defining the relationship of external calcium and mitochondrial calcium influx, we applied FCCP to taste cells for ∼7 min beginning in normal external solution with 3 mM CaCl2. During this prolonged FCCP application, the external solution was exchanged for a calcium-free external solution, and the effect on the FCCP-induced response was recorded (Fig. 6A). In Fig. 6A, the FCCP-induced calcium elevation is abolished when calcium-free external solution is added, but returns with the replacement of normal external solution. In Fig. 6, B and C, normal external solution was replaced with an external solution containing 8 mM CaCl2. When FCCP was applied to taste cells under these conditions, there was a significant increase in the magnitude of the calcium response in the external solution with 8 mM CaCl2 compared with the FCCP-induced response in external solution with 3 mM CaCl2 (average percent increase in 3 mM CaCl2 Tyrode's external = 23%; average percent increase in 8 mM CaCl2 Tyrode's external = 41%; n = 21, P = 0.002). In addition, in Fig. 6B (see arrow), the baseline calcium levels began increasing in the presence of 8 mM CaCl2, even before the mitochondria were disabled. From these data, we conclude that calcium is continually crossing the plasma membrane and is routinely buffered by the mitochondria to keep cytosolic calcium levels low.

FIG. 6.

Mitochondria buffer a calcium influx across the plasma membrane. A: a prolonged application of FCCP (7 min) caused a sustained elevated calcium level unless external calcium was removed. When external calcium was replaced, the FCCP-dependent calcium increase was restored. B: application of FCCP in 8 mM calcium external resulted in a larger calcium elevation compared with FCCP-induced calcium response that was elicited in 3 mM external calcium. In the absence of any stimulus, basal calcium levels increased when the external calcium concentration was increased from 3 to 8 mM calcium (see arrow). C: if 8 mM external calcium was initially presented, application of FCCP caused a larger increase in cytosolic calcium compared with FCCP application in 3 mM external calcium.

Mitochondria buffer a constitutive calcium influx across the plasma membrane and a calcium leak from internal stores

Although most of the calcium that is buffered by the mitochondria comes from outside the taste cells, in some cells, we measured a small FCCP-dependent calcium increase in calcium-free external solution (Fig. 5A). This small FCCP-induced calcium elevation may be caused by a small amount of calcium that was stored in the mitochondria or the result of mitochondrial buffering of a calcium leak from internal stores. To determine the source of this calcium, we measured the FCCP-evoked calcium response in calcium free external solution before and after SERCA pumps were disabled (Fig. 7). In the cells tested, we found that the FCCP-induced calcium increase in calcium-free Tyrode's was much smaller after the SERCA pumps were disabled (cf. insets in Fig. 7B). These data indicate that the mitochondria buffer a calcium influx across the plasma membrane and a calcium efflux from internal calcium stores.

What channels contribute to this constitutive calcium influx across the plasma membrane?

Since earlier experiments (Fig. 4) had already shown that VGCCs are not contributing to the FCCP-induced calcium increases, further experiments were conducted to identify the channel or channels responsible for the calcium influx across the plasma membrane in taste cells. Application of the store operated channel blockers, SKF96365 (20 μM; Supplemental Fig. 2, A and B; n = 17, P = 0.59) and MRS1845 (25 μM; Supplemental Fig. 2, C and D; n = 12, P = 0.38) did not significantly impact the FCCP-induced calcium elevations, signifying that a store-operated channel is not responsible for the calcium influx across the plasma membrane in taste cells.

We next tested the effect of lanthanum chloride (100 μM), a nonselective cation and TRP channel blocker (Halaszovich et al. 2000; Jung et al. 2003; Zhu et al. 1996), on the constitutive calcium influx. In taste cells, La3+ significantly reduced the FCCP-dependent calcium elevation compared with control (Fig. 8, A and B; n = 15, P = 0.015). In addition, La3+ alone (see arrow in Fig. 8A) could sometimes cause a decrease in basal calcium levels. Experiments using 50 μM gadolinium, another trivalent cation that blocks nonselective cation and TRP channels, also significantly reduced the amplitude of the FCCP-dependent change in cytosolic calcium (Fig. 8, C and D; n = 17, P = 0.002).

FIG. 8.

The calcium influx across the plasma membrane is significantly blocked by lanthanides. A: FCCP induced a large increase in cytosolic calcium that was significantly reduced when 100 μM LaCl3 was added. Basal cytosolic calcium levels were reduced in the presence of La3+ alone (arrow). B: the amplitude of the calcium response to FCCP in the presence of 100 μM LaCl3 was significantly reduced compared with FCCP-induced calcium increases (n = 15, P = 0.015). C: FCCP caused an increase in cytosolic calcium levels that was inhibited in the presence of 50 μM gadolinium chloride. D: application of Ga3+ caused a significant reduction in the amplitude of the FCCP-dependent increase in cytosolic calcium (n = 17, P = 0.002). E: removing external calcium caused a transient decrease in cytosolic calcium levels that “rebounded” when external calcium was replaced. Addition of La3+ to the external solution also caused a reduction in basal calcium levels. F: measurements of the percent reduction in baseline calcium levels that occurred in the presence of calcium-free external solution and 100 μM LaCl3 in normal external were not significantly different.

We wished to characterize the La3+-dependent reduction in basal calcium levels seen in Fig. 8A, so further experiments compared the effects of La3+ and calcium-free external solution. Application of La3+ and calcium-free external solution caused a comparable decrease in basal calcium levels (Fig. 8E) with no significant differences between the magnitude of the decrease in the baseline calcium levels caused by LaCl3 and calcium-free external solution (n = 6, P = 0.08; Fig. 8F). Since lanthanum can block Na+-Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) activity (Herrington et al. 1996; Kimura et al. 1986), we measured the effect of the reverse mode NCX activity on the constitutive calcium influx. Application (100 s) of two inhibitors (5 μM KB-R7943 and 5 μM SN-6) that selectively block the reverse mode of the NCX did not change cytosolic calcium levels (data not shown), indicating that the NCX functioning in the reverse mode does not contribute to the calcium influx across the plasma membrane. From these data, we concluded that the calcium influx across the plasma membrane is through a lanthanum sensitive, constitutively active channel, possibly a TRP channel.

Currently, three different TRP channels have been identified in taste cells. These channels include the calcium-sensitive TRPM5 (Perez et al. 2002, 2003; Prawitt et al. 2003), a taste variant of TRPV1 (Lyall et al. 2004, 2005), and a heteromer of Pkd1l3/Pkd2l1 (Huang et al. 2006; Ishimaru et al. 2006; LopezJimenez et al. 2006). All three of these channels have been implicated in taste transduction, but their physiological roles have not been clearly defined. We wished to determine whether any of these channels contribute to the constitutive calcium influx in taste cells. We ruled out TRPM5 because it is a monovalent selective channel and could not contribute to cytosolic calcium changes (Hofmann et al. 2003; Liu and Liman 2003). We also ruled out Pkd1l3/Pkd2l1 since this heteromer is only expressed in a subset of taste cells (Ishimaru et al. 2006; LopezJimenez et al. 2006) and we measured FCCP-dependent calcium elevations in most taste cells tested. The taste variant of TRPV1 has been proposed to be involved in salt detection (Lyall et al. 2004), but later experiments (Ruiz et al. 2006; Treesukosol et al. 2007) reported that TRPV1 is not necessary for salt detection. We tested to see whether TRPV1 contributes to the constitutive calcium influx that is routinely buffered by the mitochondria.

We initially applied FCCP in the presence of the widely used TRPV1 antagonist, capsazepine (10 μM) (Li et al. 2008), and found that the FCCP-dependent calcium increase was either abolished (Fig. 9A) or significantly reduced (average reduction = 52%; Fig. 9, B and C) in the presence of capsazepine (FCCP alone = 47.6% increase over baseline, FCCP + capsazepine = 22.9% increase over baseline, n = 17, P = 0.019). However, capsazepine has been shown to affect other voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels (Docherty et al. 1997; Liu and Simon 1997), so follow-up studies with SB-366791 (1 μM) were also performed. SB-366791 is very selective for TRPV1 and has been shown to have no effect on either TRPV4 activity, a close homolog of TRPV1, or on more distantly related TRP channels. It also does not inhibit the activity of the voltage- and ligand-gated channels that capsazepine can affect (Gunthorpe et al. 2004). SB-366791 (1 μM) also significantly reduced the FCCP-dependent calcium elevation by an average of 34% (FCCP alone = 32% increase over baseline, FCCP + 1 μM SB-633791 = 21% increase over baseline, n = 14, P = 0.03; Fig. 9D). This concentration of SB-366791 also inhibited capsaicin-induced calcium elevations in taste cells (Supplemental Fig. 3), which confirms that this antagonist inhibits a TRPV1 channel. Higher concentrations of SB-633791 (10 μM) reduced the FCCP-induced calcium increase by 32% (FCCP alone = 38% increase over baseline, FCCP + 10 μM SB-633791 = 26% increase over baseline, n = 23, P = 0.0002). From these data, we concluded that TRPV1 or a taste variant of TRPV1 in taste cells contributes to the constitutive calcium influx across the plasma membrane.

FIG. 9.

TRPV1 antagonists inhibit FCCP-induced calcium increases. A: application of 10 μM capsazepine (CAPZ) abolished the FCCP-dependent cytosolic calcium increases in some mouse taste cells. B: in other taste cells, capsazepine inhibited the rise in intracellular calcium when mitochondria were disabled with FCCP but did not completely block the response. C: capsazepine significantly inhibited the peak of the FCCP-induced calcium response in taste cells (n = 17, P = 0.019). D: application of 1 μM SB366791, another TRPV1 antagonist, significantly reduced the amplitude of the FCCP-induced calcium elevation compared with control (n = 14, P = 0.03).

DISCUSSION

This study is the first to describe a role for mitochondrial calcium transport in taste cells. Quite unexpectedly, we found that mitochondria are key contributors to the maintenance of resting calcium levels in these cells. These experiments were performed on isolated taste receptor cells that are enzymatically isolated from their native environment. This isolation procedure could be influencing the normal function of these cells, and as a result, may have an unknown impact on the observed results. The variability in the amplitude of this cytosolic calcium response to disabling mitochondrial calcium buffering correlated with the expression of different calcium signaling mechanisms in taste cells (Fig. 1) and may reflect differences in the number of mitochondria present in the taste cells, the physical placement of the mitochondria within the cytosol, or may be correlated with the expression of the channels that regulate the calcium influx. Further studies are needed to directly address these possibilities.

Most of the FCCP-dependent calcium elevations were caused by a calcium influx across the plasma membrane. Our data strongly indicate that calcium constitutively crosses the plasma membrane and is routinely buffered by the mitochondria. In the absence of external calcium, we often recorded a drop in cytosolic calcium levels that rebounded when external calcium was replaced, which also supports the conclusion that external calcium has a direct impact on internal calcium levels in taste cells. This baseline fluctuation of calcium in calcium-free external solution has been seen in other studies of taste cells (Ogura et al. 2002) but was attributed to a store-operated influx in response to cell stimulation. Although stimulus-induced store-operated calcium influx is likely occurring, in the earlier study (Ogura et al. 2002), baseline calcium levels had dropped before the taste cells were stimulated, which parallels the results from our study.

It is possible that the reduction in baseline cytosolic calcium levels in calcium-free external solution is caused by changing the calcium concentration on the outside of the cell and reversing the driving force for calcium across the plasma membrane. A reversal in the driving force for calcium could cause calcium to be extruded from taste cells via sodium-calcium exchangers functioning in the reverse mode. We do not believe this is occurring for two reasons. First, studies in other cell types do not report a similar drop in baseline calcium when calcium-free external is added (Lawrie et al. 1996; Mironov et al. 2005; White and Reynolds 1995), which suggests that most cells have mechanisms to prevent an uncontrolled loss of cytosolic calcium if external calcium levels are reduced. In addition, our experiments were performed in nominal calcium-free external in which we did not add any chelators to the external solution. As a result, the external calcium level was much lower than normal physiological levels, but it is unlikely that the external solution was completely calcium free. It is improbable that there would be a strong driving force for calcium to leave the cytosol under these conditions. However, the activity of the channel or channels that are responsible for the constitutively calcium influx could be affected. If the activity of the calcium influx channels was reduced without a concurrent reduction in the activity of the calcium extrusion mechanisms (i.e., sodium-calcium exchangers or plasma membrane calcium ATPases), cytosolic calcium levels would be expected to drop as seen in many taste cells that are exposed to calcium-free external solution.

Our pharmacological data indicated that at least one of the channels that contributes to this constitutive calcium influx is TRPV1. A taste variant of TRPV1 has been identified in taste cells (Lyall et al. 2004, 2005; Treesukosol et al. 2007) but the physiological role of this channel in taste cells has not been characterized. There are also conflicting reports within the field as to whether TRPV1 is expressed in taste cells (Lyall et al. 2004, 2005; Treesukosol et al. 2007) or if its expression is restricted to the nerve fibers that innervate taste buds (Ishida et al. 2002). Our data support the expression of TRPV1 in the taste receptor cells, because all of our experiments were performed on acutely isolated taste receptor cells, including the capsaicin-induced calcium responses.

Since low cytosolic calcium levels are maintained in taste cells, we believe that calcium efflux mechanisms must also routinely be functioning to extrude the calcium that is buffered by the mitochondria. We have identified the existence of plasma membrane calcium ATPases and multiple sodium-calcium exchangers in taste cells and have found that blocking sodium-calcium exchangers significantly affects the FCCP-induced calcium elevations (P = 0.012; A. Laskowski and K. Medler, unpublished observations). Multiple calcium extrusion mechanisms seem to remove the calcium that is initially being buffered by the mitochondria in much the same way these extrusion mechanisms function in other cell types to remove calcium that is buffered by the mitochondria. Future studies will elucidate the relative role of these calcium extrusion mechanisms in the regulation of cytosolic calcium levels in taste cells.

Based on our data, we propose that mitochondria interact with a calcium flux at the plasma membrane in a similar manner that mitochondria have been shown to interact with the calcium flux from internal calcium stores in other cell types (Arnaudeau et al. 2001; Csordas and Hajnoczky 2001; Csordas et al. 1999, 2001; Hajnoczky et al. 1999, 2000a,b; Jackson and Thayer 2006; Johnson et al. 2002; Kopach et al. 2008; Landolfi et al. 1998; Pacher et al. 2000; Szalai et al. 2000). In acinar cells, calcium release from internal stores is immediately buffered by mitochondria, thus preventing a global cytosolic calcium increase in response to ryanodine receptor (RyR) activation and prolonging the calcium-induced calcium release signal in these cells (Kopach et al. 2008). Our data indicate that in taste cells, there is a constitutive calcium influx across the plasma membrane through TRPV1 and possibly other channels. This calcium influx is initially buffered by the mitochondria and subsequently extruded by calcium efflux mechanisms at the plasma membrane. When external calcium is reduced or absent (see Figs. 5–7), cytosolic calcium levels drop below normal basal values because the amount of calcium influx has been reduced. This disrupts the normal balance between calcium influx, mitochondrial calcium buffering, and calcium efflux and results in an overall decrease in cytosolic calcium levels.

The findings from this study raise interesting questions about calcium regulation in taste cells. Why is there a constitutive calcium influx in taste cells that is continually buffered by the mitochondria, even in the absence of cell stimulation? Although the answer to this question is beyond the scope of this study, there are some unique characteristics of taste cells that may provide insight as to why these cells have unique calcium buffering requirements. Taste cells share characteristics with both epithelial cells and neurons. They are located in the epithelia, produce cytokeratins, and are continuously replaced (Farbman 1980; Finger and Simon 2000) but are neuronal in nature because they form synapses with gustatory neurons (Kinnamon et al. 1985, 1988; Royer and Kinnamon 1988), express voltage-gated ion channels, and fire action potentials (Roper 1983). Unlike most neurons, however, taste cells are routinely replaced throughout the lifetime of the organism (Farbman 1980; Finger and Simon 2000). Although the trigger for apoptosis of mature taste cells has not yet been identified, we speculate that the constitutive calcium buffering by the mitochondria may contribute in some way to the generation of the apoptotic signal needed to cause cell turnover. Multiple studies have shown that acutely elevated calcium levels initiate apoptosis in other cells through toxic calcium loads place on the mitochondria (Chakraborti et al. 1999; Duchen 2000b; Ghribi et al. 2001; Hajnoczky et al. 2006). Since taste cells are “programmed” to survive 10–14 days and then be replaced, this unusual level of calcium buffering in unstimulated taste cells may contribute to determining the life span of these cells.

Another interesting characteristic of taste cells has been the recent identification of ATP as a neurotransmitter (Finger et al. 2005). ATP does not seem to be packaged in vesicles like most neurotransmitters, but instead is directly released through a hemichannel (Huang et al. 2007; Romanov et al. 2007). How this neurotransmitter mechanism is controlled has not been characterized but mechanically induced ATP release has been tightly correlated with cytosolic calcium elevations in other cell types (Boudreault and Grygorczyk 2004). ATP could be acutely upregulated in response to a stimulus signal, so it is available for its subsequent release as a neurotransmitter, or it may be that excess ATP is continually present in the cytosol of taste cells. This mechanism could cause a higher demand for “resting” ATP levels in taste cells compared with other cell types that would be accomplished by higher mitochondrial functioning. Indeed, studies in other cell types (Jouaville et al. 1999; McCormack and Denton 1993; Tsuboi et al. 2003) have shown that calcium buffering by the mitochondria is closely tied to the metabolic needs of the cells and the production of ATP. Some enzymes in the mitochondrial matrix are calcium sensitive and increase their activity as mitochondrial calcium levels increase, which results in increased ATP production (Denton and McCormack 1985; Denton et al. 1972, 1978; McCormack and Denton 1979, 1993; McCormack et al. 1990).

Since the neurotransmitter ATP is being released in a nonvesicular mechanism through a hemichannel (Huang et al. 2007; Romanov et al. 2007), it is possible that continual calcium uptake by the mitochondria is necessary for the sufficient production of ATP as a neurotransmitter in these taste cells. Although almost all taste cells have a constitutive calcium influx that is buffered by the mitochondria, we found significant differences in the amplitude of the FCCP-dependent calcium elevation that correlated with the calcium signaling mechanisms used by the taste cells. The taste cells that rely on calcium release from stores to activate the hemichannel and release ATP had significantly smaller FCCP-induced calcium elevations compared with other taste cells. We do not yet know why this dichotomy exists, but future studies will determine whether these differences are caused by characteristics of the calcium influx at the plasma membrane or caused by some properties of the mitochondrial calcium buffering in these taste cells.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disorders Grant DC-006358 to K. Medler.

Acknowledgments

We thank S. Prajapati for technical assistance and Drs. Evanna Gleason and Scott Medler for insightful comments.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains supplemental data.

REFERENCES

- Arnaudeau et al. 2001.Arnaudeau S, Kelley WL, Walsh JV Jr, Demaurex N. Mitochondria recycle Ca(2+) to the endoplasmic reticulum and prevent the depletion of neighboring endoplasmic reticulum regions. J Biol Chem 276: 29430–29439, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock et al. 1997.Babcock DF, Herrington J, Goodwin PC, Park YB, Hille B. Mitochondrial participation in the intracellular Ca2+ network. J Cell Biol 136: 833–844, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babcock and Hille 1998.Babcock DF, Hille B. Mitochondrial oversight of cellular Ca2+ signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol 8: 398–404, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baryshnikov et al. 2003.Baryshnikov SG, Rogachevskaja OA, Kolesnikov SS. Calcium signaling mediated by P2Y receptors in mouse taste cells. J Neurophysiol 90: 3283–3294, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beam and Knudson 1988.Beam KG, Knudson CM. Calcium currents in embryonic and neonatal mammalian skeletal muscle. J Gen Physiol 91: 781–798, 1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitier et al. 1999.Boitier E, Rea R, Duchen MR. Mitochondria exert a negative feedback on the propagation of intracellular Ca2+ waves in rat cortical astrocytes. J Cell Biol 145: 795–808, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreault and Grygorczyk 2004.Boudreault F, Grygorczyk R. Cell swelling-induced ATP release is tightly dependent on intracellular calcium elevations. J Physiol 561: 499–513, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman 1983.Bowman EJ Comparison of the vacuolar membrane ATPase of Neurospora crassa with the mitochondrial and plasma membrane ATPases. J Biol Chem 258: 15238–15244, 1983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowman et al. 1981.Bowman EJ, Bowman BJ, Slayman CW. Isolation and characterization of plasma membranes from wild type Neurospora crassa. J Biol Chem 256: 12336–12342, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd and Nicholls 1996.Budd SL, Nicholls DG. A reevaluation of the role of mitochondria in neuronal Ca2+ homeostasis. J Neurochem 66: 403–411, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budd and Nicholls 1998.Budd SL, Nicholls DG. Mitochondria in the life and death of neurons. Essays Biochem 33: 43–52, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulychev and Vredenberg 1976.Bulychev AA, Vredenberg WJ. Effect of ionophores A23187 and nigericin on the light-induced redistribution of Mg2+, K+ and H+ across the thylakoid membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta 449: 48–58, 1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborti et al. 1999.Chakraborti T, Das S, Mondal M, Roychoudhury S, Chakraborti S. Oxidant, mitochondria and calcium: an overview. Cell Signal 11: 77–85, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp et al. 2006.Clapp TR, Medler KF, Damak S, Margolskee RF, Kinnamon SC. Mouse taste cells with G protein-coupled taste receptors lack voltage-gated calcium channels and SNAP-25. BMC Biol 4: 7, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clapp et al. 2004.Clapp TR, Yang R, Stoick CL, Kinnamon SC, Kinnamon JC. Morphologic characterization of rat taste receptor cells that express components of the phospholipase C signaling pathway. J Comp Neurol 468: 311–321, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegrove et al. 2000a.Colegrove SL, Albrecht MA, Friel DD. Dissection of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and release fluxes in situ after depolarization-evoked [Ca2+](i) elevations in sympathetic neurons. J Gen Physiol 115: 351–370, 2000a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colegrove et al. 2000b.Colegrove SL, Albrecht MA, Friel DD. Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake and release pathways in sympathetic neurons. Reconstruction of the recovery after depolarization-evoked [Ca2+]i elevations. J Gen Physiol 115: 371–388, 2000b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas and Hajnoczky 2001.Csordas G, Hajnoczky G. Sorting of calcium signals at the junctions of endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Cell Calcium 29: 249–262, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas et al. 1999.Csordas G, Thomas AP, Hajnoczky G. Quasi-synaptic calcium signal transmission between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. EMBO J 18: 96–108, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Csordas et al. 2001.Csordas G, Thomas AP, Hajnoczky G. Calcium signal transmission between ryanodine receptors and mitochondria in cardiac muscle. Trends Cardiovasc Med 11: 269–275, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David and Barrett 2000.David G, Barrett EF. Stimulation-evoked increases in cytosolic [Ca(2+)] in mouse motor nerve terminals are limited by mitochondrial uptake and are temperature-dependent. J Neurosci 20: 7290–7296, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFazio et al. 2006.DeFazio RA, Dvoryanchikov G, Maruyama Y, Kim JW, Pereira E, Roper SD, Chaudhari N. Separate populations of receptor cells and presynaptic cells in mouse taste buds. J Neurosci 26: 3971–3980, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton and McCormack 1985.Denton RM, McCormack JG. Ca2+ transport by mammalian mitochondria and its role in hormone action. Am J Physiol 249: E543–E554, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton et al. 1972.Denton RM, Randle PJ, Martin BR. Stimulation by calcium ions of pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphate phosphatase. Biochem J 128: 161–163, 1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton et al. 1978.Denton RM, Richards DA, Chin JG. Calcium ions and the regulation of NAD+-linked isocitrate dehydrogenase from the mitochondria of rat heart and other tissues. Biochem J 176: 899–906, 1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Docherty et al. 1997.Docherty RJ, Yeats JC, Piper AS. Capsazepine block of voltage-activated calcium channels in adult rat dorsal root ganglion neurones in culture. Br J Pharmacol 121: 1461–1467, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen 2000a.Duchen MR Mitochondria and Ca(2+)in cell physiology and pathophysiology. Cell Calcium 28: 339–348, 2000a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchen 2000b.Duchen MR Mitochondria and calcium: from cell signalling to cell death. J Physiol 529: 57–68, 2000b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farbman 1980.Farbman AI Renewal of taste bud cells in rat circumvallate papillae. Cell Tissue Kinet 13: 349–357, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger et al. 2005.Finger TE, Danilova V, Barrows J, Bartel DL, Vigers AJ, Stone L, Hellekant G, Kinnamon SC. ATP signaling is crucial for communication from taste buds to gustatory nerves. Science 310: 1495–1499, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger and Simon 2000.Finger TE, Simon SA. Cell biology of taste epithelium. In: The Neurobiology of Taste and Smell, edited by Finger TE, Silver WL, Restrepo D. New York: Wiley-Liss, 2000, p. 287–314.

- Friel and Tsien 1994.Friel DD, Tsien RW. An FCCP-sensitive Ca2+ store in bullfrog sympathetic neurons and its participation in stimulus-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i. J Neurosci 14: 4007–4024, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghribi et al. 2001.Ghribi O, DeWitt DA, Forbes MS, Herman MM, Savory J. Co-involvement of mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in regulation of apoptosis: changes in cytochrome c, Bcl-2 and Bax in the hippocampus of aluminum-treated rabbits. Brain Res 903: 66–73, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz et al. 1985.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem 260: 3440–3450, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunthorpe et al. 2004.Gunthorpe MJ, Rami HK, Jerman JC, Smart D, Gill CH, Soffin EM, Luis Hannan S, Lappin SC, Egerton J, Smith GD, Worby A, Howett L, Owen D, Nasir S, Davies CH, Thompson M, Wyman PA, Randall AD, Davis JB. Identification and characterisation of SB-366791, a potent and selective vanilloid receptor (VR1/TRPV1) antagonist. Neuropharmacology 46: 133–149, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hacker et al. 2008.Hacker K, Laskowski A, Feng L, Restrepo D, Medler K. Evidence for two populations of bitter responsive taste cells in mice. J Neurophysiol 99: 1503–1514, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky et al. 2006.Hajnoczky G, Csordas G, Das S, Garcia-Perez C, Saotome M, Sinha Roy S, Yi M. Mitochondrial calcium signalling and cell death: approaches for assessing the role of mitochondrial Ca2+ uptake in apoptosis. Cell Calcium 40: 553–560, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky et al. 2000a.Hajnoczky G, Csordas G, Krishnamurthy R, Szalai G. Mitochondrial calcium signaling driven by the IP3 receptor. J Bioenerg Biomembr 32: 15–25, 2000a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky et al. 2000b.Hajnoczky G, Csordas G, Madesh M, Pacher P. The machinery of local Ca2+ signalling between sarco-endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. J Physiol 529: 69–81, 2000b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajnoczky et al. 1999.Hajnoczky G, Hager R, Thomas AP. Mitochondria suppress local feedback activation of inositol 1,4, 5-trisphosphate receptors by Ca2+. J Biol Chem 274: 14157–14162, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaszovich et al. 2000.Halaszovich CR, Zitt C, Jungling E, Luckhoff A. Inhibition of TRP3 channels by lanthanides. Block from the cytosolic side of the plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 275: 37423–37428, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrington et al. 1996.Herrington J, Park YB, Babcock DF, Hille B. Dominant role of mitochondria in clearance of large Ca2+ loads from rat adrenal chromaffin cells. Neuron 16: 219–228, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann et al. 2003.Hofmann T, Chubanov V, Gudermann T, Montell C. TRPM5 is a voltage-modulated and Ca(2+)-activated monovalent selective cation channel. Curr Biol 13: 1153–1158, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. 2006.Huang AL, Chen X, Hoon MA, Chandrashekar J, Guo W, Trankner D, Ryba NJ, Zuker CS. The cells and logic for mammalian sour taste detection. Nature 442: 934–938, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang et al. 2007.Huang YJ, Maruyama Y, Dvoryanchikov G, Pereira E, Chaudhari N, Roper SD. The role of pannexin 1 hemichannels in ATP release and cell-cell communication in mouse taste buds. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 6436–6441, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishida et al. 2002.Ishida Y, Ugawa S, Ueda T, Murakami S, Shimada S. Vanilloid receptor subtype-1 (VR1) is specifically localized to taste papillae. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 107: 17–22, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru et al. 2006.Ishimaru Y, Inada H, Kubota M, Zhuang H, Tominaga M, Matsunami H. Transient receptor potential family members PKD1L3 and PKD2L1 form a candidate sour taste receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 12569–12574, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson and Thayer 2006.Jackson JG, Thayer SA. Mitochondrial modulation of Ca2+ -induced Ca2+- release in rat sensory neurons. J Neurophysiol 96: 1093–1104, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson et al. 2002.Johnson PR, Tepikin AV, Erdemli G. Role of mitochondria in Ca(2+) homeostasis of mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Cell Calcium 32: 59–69, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouaville et al. 1999.Jouaville LS, Pinton P, Bastianutto C, Rutter GA, Rizzuto R. Regulation of mitochondrial ATP synthesis by calcium: evidence for a long-term metabolic priming. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96: 13807–13812, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung et al. 2003.Jung S, Muhle A, Schaefer M, Strotmann R, Schultz G, Plant TD. Lanthanides potentiate TRPC5 currents by an action at extracellular sites close to the pore mouth. J Biol Chem 278: 3562–3571, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim et al. 2005.Kim MH, Korogod N, Schneggenburger R, Ho WK, Lee SH. Interplay between Na+/Ca2+ exchangers and mitochondria in Ca2+ clearance at the calyx of Held. J Neurosci 25: 6057–6065, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimura et al. 1986.Kimura J, Noma A, Irisawa H. Na-Ca exchange current in mammalian heart cells. Nature 319: 596–597, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnamon et al. 1988.Kinnamon JC, Sherman TA, Roper SD. Ultrastructure of mouse vallate taste buds. III. Patterns of synaptic connectivity. J Comp Neurol 270: 1–10: 56–57, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnamon et al. 1985.Kinnamon JC, Taylor BJ, Delay RJ, Roper SD. Ultrastructure of mouse vallate taste buds. I. Taste cells and their associated synapses. J Comp Neurol 235: 48–60, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopach et al. 2008.Kopach O, Kruglikov I, Pivneva T, Voitenko N, Fedirko N. Functional coupling between ryanodine receptors, mitochondria and Ca(2+) ATPases in rat submandibular acinar cells. Cell Calcium 43: 469–481, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koyama 1999.Koyama N Presence of Na+-stimulated P-type ATPase in the membrane of a facultatively anaerobic alkaliphile, Exiguobacterium aurantiacum. Curr Microbiol 39: 27–30, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubota et al. 2003.Kubota Y, Hashitani H, Fukuta H, Kubota H, Kohri K, Suzuki H. Role of mitochondria in the generation of spontaneous activity in detrusor smooth muscles of the Guinea pig bladder. J Urol 170: 628–633, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolfi et al. 1998.Landolfi B, Curci S, Debellis L, Pozzan T, Hofer AM. Ca2+ homeostasis in the agonist-sensitive internal store: functional interactions between mitochondria and the ER measured In situ in intact cells. J Cell Biol 142: 1235–1243, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrie et al. 1996.Lawrie AM, Rizzuto R, Pozzan T, Simpson AWM. A role for calcium influx in the regulation of mitochondrial calcium in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem 271: 10753–10759, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li et al. 2008.Li HB, Mao RR, Zhang JC, Yang Y, Cao J, Xu L. Antistress effect of TRPV1 channel on synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. Biol Psychiatry 64: 286–292, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu and Liman 2003.Liu D, Liman ER. Intracellular Ca2+ and the phospholipid PIP2 regulate the taste transduction ion channel TRPM5. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 15160–15165, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu and Simon 1997.Liu L, Simon SA. Capsazepine, a vanilloid receptor antagonist, inhibits nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in rat trigeminal ganglia. Neurosci Lett 228: 29–32, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LopezJimenez et al. 2006.LopezJimenez ND, Cavenagh MM, Sainz E, Cruz-Ithier MA, Battey JF, Sullivan SL. Two members of the TRPP family of ion channels, Pkd1l3 and Pkd2l1, are co-expressed in a subset of taste receptor cells. J Neurochem 98: 68–77, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyall et al. 2005.Lyall V, Heck GL, Phan TH, Mummalaneni S, Malik SA, Vinnikova AK, Desimone JA. Ethanol modulates the VR-1 variant amiloride-insensitive salt taste receptor. II. Effect on chorda tympani salt responses. J Gen Physiol 125: 587–600, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyall et al. 2004.Lyall V, Heck GL, Vinnikova AK, Ghosh S, Phan TH, Alam RI, Russell OF, Malik SA, Bigbee JW, DeSimone JA. The mammalian amiloride-insensitive non-specific salt taste receptor is a vanilloid receptor-1 variant. J Physiol 558: 147–159, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malli et al. 2003.Malli R, Frieden M, Osibow K, Zoratti C, Mayer M, Demaurex N, Graier WF. Sustained Ca2+ transfer across mitochondria is essential for mitochondrial Ca2+ buffering, sore-operated Ca2+ entry, and Ca2+ store refilling. J Biol Chem 278: 44769–44779, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malli et al. 2005.Malli R, Frieden M, Trenker M, Graier WF. The role of mitochondria for Ca2+ refilling of the endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 280: 12114–12122, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack and Denton 1979.McCormack JG, Denton RM. The effects of calcium ions and adenine nucleotides on the activity of pig heart 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex. Biochem J 180: 533–544, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack and Denton 1993.McCormack JG, Denton RM. Mitochondrial Ca2+ transport and the role of intramitochondrial Ca2+ in the regulation of energy metabolism. Dev Neurosci 15: 165–173, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack et al. 1990.McCormack JG, Halestrap AP, Denton RM. Role of calcium ions in regulation of mammalian intramitochondrial metabolism. Physiol Rev 70: 391–425, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medler and Gleason 2002.Medler K, Gleason EL. Mitochondrial Ca(2+) buffering regulates synaptic transmission between retinal amacrine cells. J Neurophysiol 87: 1426–1439, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medler et al. 2003.Medler KF, Margolskee RF, Kinnamon SC. Electrophysiological characterization of voltage-gated currents in defined taste cell types of mice. J Neurosci 23: 2608–2617, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mironov et al. 2005.Mironov SL, Ivannikov MV, Johansson M. [Ca2+]i signaling between mitochondria and endoplasmic reticulum in neurons is regulated by microtubules. From mitochondrial permeability transition pore to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release. J Biol Chem 280: 715–721, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero et al. 2001.Montero M, Alonso MT, Albillos A, Garcia-Sancho J, Alvarez J. Mitochondrial Ca(2+)-induced Ca(2+) release mediated by the Ca(2+) uniporter. Mol Biol Cell 12: 63–71, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montero et al. 2000.Montero M, Alonso MT, Carnicero E, Cuchillo-Ibanez I, Albillos A, Garcia AG, Garcia-Sancho J, Alvarez J. Chromaffin-cell stimulation triggers fast millimolar mitochondrial Ca2+ transients that modulate secretion. Nat Cell Biol 2: 57–61, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls 2006.Nicholls DG Simultaneous monitoring of ionophore- and inhibitor-mediated plasma and mitochondrial membrane potential changes in cultured neurons. J Biol Chem 281: 14864–14874, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]