Abstract

Primary and metastatic cancers that effect bone are frequently associated with pain. Sensitization of primary afferent C nociceptors innervating tissue near the tumor likely contributes to the chronic pain and hyperalgesia accompanying this condition. This study focused on the role of the endogenous peptide endothelin-1 (ET-1) as a potential peripheral algogen implicated in the process of cancer pain. Electrophysiological response properties, including ongoing activity and responses evoked by heat stimuli, of C nociceptors were recorded in vivo from the tibial nerve in anesthetized control mice and mice exhibiting mechanical hyperalgesia following implantation of fibrosarcoma cells into and around the calcaneus bone. ET-1 (100 μM) injected into the receptive fields of C nociceptors innervating the plantar surface of the hind paw evoked an increase in ongoing activity in both control and tumor-bearing mice. Moreover, the selective ETA receptor antagonist, BQ-123 (3 mM), attenuated tumor-evoked ongoing activity in tumor-bearing mice. Whereas ET-1 produced sensitization of C nociceptors to heat stimuli in control mice, C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice were sensitized to heat, and their responses were not further increased by ET-1. Importantly, administration of BQ-123 attenuated tumor-evoked sensitization of C nociceptors to heat. We conclude that ET-1 at the tumor site contributes to tumor-evoked excitation and sensitization of C nociceptors through an ETA receptor mediated mechanism.

INTRODUCTION

Primary bone cancers and cancers that metastasize to bone often cause severe pain in humans (Mercadante 1997; Portenoy et al. 1999). Although the mechanisms that contribute to pain associated with cancer in bone are not well understood, significant progress has been made following the development of rodent models of cancer pain (Medhurst et al. 2002; Menendez et al. 2003a; Schwei et al. 1999; Wacnik et al. 2003).

We used a murine model of cancer pain in which fibrosarcoma cells were implanted into and around the calcaneus bone (Wacnik et al. 2001). This model permits direct quantification of tumor-related changes in response properties and morphology of primary afferent fibers (Cain et al. 2001; Gilchrist et al. 2005). Tumor growth in this model concurrently evokes mechanical and thermal hyperalgesia (Hamamoto et al. 2007; Khasabov et al. 2007; Wacnik et al. 2001), sensitization of nociceptive dorsal horn neurons (Khasabov et al. 2007), sensitization of C nociceptors that innervate skin overlying the tumor (Cain et al. 2001), and development of peripheral neuropathy as indicated by decreased innervation of the epidermis (Cain et al. 2001; Gilchrist et al. 2005).

Studies using rodent models of cancer pain have revealed a number of mediators that contribute to tumor-evoked nocifensive behaviors and hyperalgesia (Peters et al. 2004; Sevcik et al. 2005a,b; Wacnik et al. 2001). One such mediator is endothelin-1 (ET-1), a 21 amino acid peptide that was first isolated from endothelial cells and defined functionally as a vasoconstrictor (Yanagisawa et al. 1988). ET-1 is a member of the endothelin family, which also includes ET-2, ET-3, and the sarafotoxins, and is synthesized by a variety of cells including neurons and glial cells in the central and peripheral nervous systems (Giaid et al. 1989; MacCumber et al. 1990), macrophages (Ehrenreich et al. 1990), endothelial cells (Yanagisawa et al. 1988), and keratinocytes (Yohn et al. 1993). Members of the endothelin family bind to two distinct G-protein-coupled receptors, ETA and ETB (Vane 1990). The ETA receptor preferentially binds ET-1 whereas the ETB has similar affinities for ET-1, ET-2, and ET-3 (Arai et al. 1990; Sakurai et al. 1990).

ET-1 is expressed in several human cancer types, including prostate, lung, breast, and colorectal, that have a high incidence of metastasis to bone (Kusuhara et al. 1990; Nelson 2005; Nelson and Carducci 2000). Increased expression of the ETA receptor has been associated with progression of some cancers in humans (Gohji et al. 2001), and ET-1 stimulates proliferation of some cancer cell lines (Shichiri et al. 1991) through a ETA receptor-mediated mechanism (Nelson et al. 1996). Furthermore, ET-1 is involved in tumor mitogenesis, apoptosis, invasion, and metastasis (Grant et al. 2003). Thus ET-1 appears to play a major role in the tumorgenesis of some cancers.

In addition to a potential role in tumorogenesis, ET-1 may also serve as an algogen to produce nociception. Numerous studies have demonstrated that injection of ET-1 into the knee or hind paw evokes nocifensive behaviors (Baamonde et al. 2004; Balonov et al. 2006; De-Melo et al. 1998a; Ferreira et al. 1989; Gokin et al. 2001; McKelvy et al. 2007; Menendez et al. 2003b; Piovezan et al. 1998, 2004; Verri et al. 2004, 2005), tactile allodynia (Balonov et al. 2006; McKelvy et al. 2007), and mechanical (da Cunha et al. 2004; Ferreira et al. 1989) and heat (Menendez et al. 2003b) hyperalgesia through a mechanism involving the ETA receptors located in peripheral tissues (Baamonde et al. 2004; Davar et al. 1998; De-Melo et al. 1998a; Fareed et al. 2000; Gokin et al. 2001; Menendez et al. 2003b; Piovezan et al. 2000). Injection of ET-1 into the skin excites C nociceptors (Gokin et al. 2001; Khodorova et al. 2002; Namer et al. 2007) and likely contributes to ET-1-evoked nocifensive behaviors.

Because administration of ET-1 into peripheral tissues produces nocifensive behaviors in animals and pain in humans (Ferreira et al. 1989; Hans et al. 2007; Namer et al. 2007), it is possible that ET-1 released by tumor cells may contribute to tumor-evoked pain and hyperalgesia (Davar 2001). In support of this idea, systemic administration of an ETA receptor selective antagonist attenuated cancer-related pain in humans (Carducci et al. 2002). Furthermore, intraplantar injection of ET-1 into the tumor-bearing hind paws of mice potentiated tumor-evoked nocifensive behaviors, and this effect was attenuated by systemic administration of ETA receptor-selective antagonists (Yuyama et al. 2004a,b). Expression of ET-1 is upregulated in animal models of tumor-evoked hyperalgesia (Peters et al. 2004; Schmidt et al. 2007), including the model used in the present study (Wacnik et al. 2001), and administration of ETA receptor-selective antagonists either systemically (Peters et al. 2004) or injected into the tumor-bearing tissues attenuated tumor-evoked hyperalgesia (Pickering et al. 2007; Schmidt et al. 2007; Wacnik et al. 2001). Finally, a tumor that did not exhibit increased levels of ET-1 also did not produce tumor-evoked hyperalgesia (Wacnik et al. 2001). Thus release of ET-1 from tumor cells could contribute to tumor-evoked hyperalgesia.

Ongoing activity of nociceptors may contribute to spontaneous pain (Djouhri et al. 2006). Therefore persistent release of ET-1 from tumor cells could produce ongoing excitation of C nociceptors and contribute to spontaneous pain in cancer patients. Indeed we have shown that C nociceptors in mice with tumor-evoked hyperalgesia exhibited ongoing activity and sensitization to heat (Cain et al. 2001). Therefore the aim of this study was to examine the role of ET-1 in sensitization of C nociceptors in mice with tumor-evoked hyperalgesia.

METHODS

Subjects

A total of 76 adult, male C3H mice (36 control and 40 tumor-bearing mice) weighing 20–30 g obtained from the National Institutes of Health were used in the current study. Animals were housed on a 12-h light/dark schedule and given ad libitum access to food and water. All procedures were approved by the Animal Care Committee of the University of Minnesota. Experiments were conducted according to the guidelines set forth by the International Association for the Study of Pain (Zimmermann 1983).

Implantation of fibrosarcoma cells

NCTC clone 2472 fibrosarcoma cells were obtained from American Type Cell Culture (Manassas, VA) and maintained as described previously (Cain et al. 2001). These cells were initially derived from a spontaneous connective tissue tumor in C3H mice. Briefly, fibrosarcoma cells were grown to confluence in 75 cm2 flasks in NCTC 135 medium (Sigma, St Louis, MO) with 10% horse serum at pH 7.35 and passaged weekly (1:4–6 split ratio). Fibrosarcoma cells were trypsinized to create a cell suspension then counted with a hemacytometer, pelleted, and resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for implantation in a concentration of 2 ×104 cell/μl.

Mice were anesthetized with 1–2% halothane then fibrosarcoma cells (2 ×105 cell in 10 μl) were injected unilaterally into and around the calcaneus bone using a 0.3-ml insulin syringe with a 29.5-gauge needle as describe previously (Cain et al. 2001). None of the mice showed signs of permanent motor dysfunction after implantation. Mice without implantation of fibrosarcoma cells served as the control group because a previous study has shown that a sham implantation of PBS into and around the calcaneus bone did not produce significant hyperalgesia (Wacnik et al. 2001).

Behavioral measures of nociception

Mice were placed on a wire mesh platform, covered with a hand-sized container, and allowed to acclimate to their surroundings for a minimum of 30 min before testing. A von Frey filament (bending force of 3.4 mN) was applied 10 times for 1–2 s each time at 5-s intervals to random locations of the plantar surface of the hind paw. Vigorous paw withdrawals were counted, and a withdrawal response frequency was calculated for each hind paw. Withdrawal response frequencies were obtained for 3 days preceding implantation of fibrosarcoma cells and on every second day thereafter until day 16. Only tumor-bearing mice exhibiting a paw withdrawal frequency of ≥70% for two consecutive days were used in the electrophysiological experiments. Approximately 90% of mice implanted with fibrosarcoma cells exhibited sufficient mechanical hyperalgesia and were used in the electrophysiological studies. Electrophysiology studies of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice were performed 9–16 days after implantation as mechanical hyperalgesia is maximal during this period (Hamamoto et al. 2007; Wacnik et al. 2001).

Electrophysiological recording from primary afferent fibers

The method of recording electrophysiological responses of single primary afferent fibers from the tibia nerve has been described previously (Cain et al. 2001). Mice were anesthetized with acepromazine maleate (20 mg/kg ip) and sodium pentobarbital (Nembutal, 48 mg/kg ip). Supplemental doses of sodium pentobarbital (15 mg/kg) were given as needed to maintain areflexia. Hair was removed from one hind limb, and an incision was made through the skin of the dorsal aspect of the lower leg. The gastrocnemius muscle was surgically removed to expose the tibial nerve. The skin was sutured to a metal ring (1.3 cm ID) to form a basin, a rubber-based polysulfide impression material (Co-Flex, Sullivan Schein, Melville, NY) was applied to the skin around the ring to prevent leakage, and the basin was filled with warm mineral oil. The tibial nerve was dissected from connective tissue and placed on a small, mirrored platform. The epineurium of the nerve was opened using a miniature scalpel, and small fascicles were cut to allow the proximal ends to be spread out on the platform for separation with fine jeweler's forceps. Nerve fascicles were teased apart, and fine filaments were placed on a silver-wire recording electrode to obtain an extracellular recording from a single fiber that could be easily discriminated according to amplitude. Action potentials were amplified, audio-monitored, displayed on an oscilloscope, discriminated and stored in a PC computer for off-line data analysis using a customized program (LabVIEW, version 5.1, National Instruments, Austin, TX).

Electrophysiological characteristics and response properties of primary afferent fibers

IDENTIFICATION OF PRIMARY AFFERENT FIBERS.

Only fibers in control and cancer mice that had mechanical receptive fields (RFs) on the plantar surface of the hind paw were studied. Once a fiber was isolated, the location of its RF was identified using a small glass probe (1 mm diam tip), and the location was then marked on the skin with a felt-tip pen. The mechanical threshold of the fiber was obtained by using a series of von Frey filaments with increasing bending forces and was expressed as the minimum force needed to evoke a response in ≥50% of the trials. To ensure that recordings were obtained exclusively from fibers innervating the skin rather than from fibers innervating deep tissues, the skin surrounding the RF was gently grasped with dull forceps and lifted. Only fibers that discharged primarily while the skin containing the RF was lifted and lightly squeezed were considered to be cutaneous units. In addition, toes and joints were manipulated to identify proprioceptive units, which were not studied further.

CONDUCTION VELOCITY.

Once the location of the RF on the plantar surface of the hind paw was identified, two fine needle electrodes (30 gauge) were inserted into the skin on opposite sides adjacent to the RF. Square-wave pulses (duration: 0.2 ms, 0.5 Hz) were delivered at a stimulating intensity of 1.5 times the minimal voltage required to evoke an action potential. The conduction latency of action potentials and distance between the RF and the recording electrode were determined for calculation of conduction velocity (CV). Primary afferent fibers were classed as Aβ (CV > 13.6 m/s), Aδ (13.6 ≥ CV ≥ 1.3 m/s) or C (CV < 1.3 m/s) fibers (Cain et al. 2001).

THERMAL STIMULATION.

Heat stimuli were delivered by a Peltier-type thermode controlled by the LabVIEW software program. Stimuli (35 to 51°C) were applied to the plantar surface of the paw for a duration of 5 s. Stimuli were delivered in ascending steps of 2°C from a base temperature of 32°C with a ramp rate of 20°C/s and an interstimulus interval of 60 s.

Pharmacological studies

ET-1 (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Mountain View, CA) and an ETA receptor selective antagonist, BQ-123 (American Peptide, Sunnyvale, CA), were dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 100 μM and 3 mM, respectively. ET-1, BQ-123, or vehicle (10 μl PBS) was injected subcutaneously into the RF using a 0.3-ml syringe with 30-gauge needle.

For each C nociceptor, the baseline level of ongoing activity was recorded over a 2-min period, and then responses to the series of heat stimuli were obtained. ET-1, BQ-123, or vehicle was injected into the RF, and ongoing activity and responses to heat were again determined. Ongoing activity and responses to heat stimuli were determined at 5 and 20 min after injection of ET-1 and at 10 and 20 min after injection for BQ-123. Most nociceptors were exposed to only one injection. When both vehicle and ET-1 (or BQ-123) were injected into the RF of a nociceptor, vehicle was injected first and ET-1 (or BQ-123) was injected ≥60 min after injection of vehicle.

Data analyses

Conduction velocity (m/s) of single C nociceptors, mechanical response thresholds (mN), levels of ongoing activity (imp/s), heat-response thresholds (°C), and responses (number of impulses) to the series of heat stimuli are presented as means ± SE. For the responses to the heat stimuli, the level of ongoing activity over the 10 s prior to delivery of the heat stimulus was subtracted from the response. Conduction velocities, mechanical thresholds, intra-burst frequencies, burst durations, and intervals between bursts for C nociceptors were compared between control and tumor-bearing mice using t-tests. Levels of ongoing activity, heat-response thresholds, and responses to heat before (baseline) and after injection of vehicle, ET-1, or BQ-123 were compared by ANOVAs. Pairwise comparisons between groups were made using Newman-Kuels post hoc analyses or t-test with the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. For all comparisons, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General characteristics of C nociceptors

Electrophysiological recordings were made from 46 C nociceptors in control mice (n = 36) and 58 C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice (n = 40). The mean conduction velocity of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice (0.38 ± 0.02 m/s) was slightly slower than that in control mice (0.51 ± 0.03 m/s; P < 0.001). Only 2 of 46 (4%) C nociceptors in control mice exhibited ongoing activity, and the discharge frequencies for these two fibers were 1.5 and 1.6 imp/s. In contrast, 49 of 58 (84%) C nociceptors studied in tumor-bearing mice exhibited ongoing activity that ranged in discharge rates from 0.1 to 4.5 imp/s (1.0 ± 0.2 imp/s). Mean mechanical thresholds for C nociceptors were determined using von Frey filaments and did not differ between tumor-bearing (29.1 ± 3.6 mN) and control (25.7 ± 5.3 mN) mice.

Effect of ET-1 on ongoing activity of C nociceptors

Figure 1A shows an example of the electrophysiological responses of a typical C nociceptor in a control mouse. This C nociceptor did not exhibit ongoing activity either at baseline or 5 min after injection of vehicle (10 μl of PBS) into its RF. Sixty minutes later, 100 μM of ET-1 (in 10 μl) was injected into the RF. Five minutes after injection of ET-1, this C nociceptor exhibited ongoing activity.

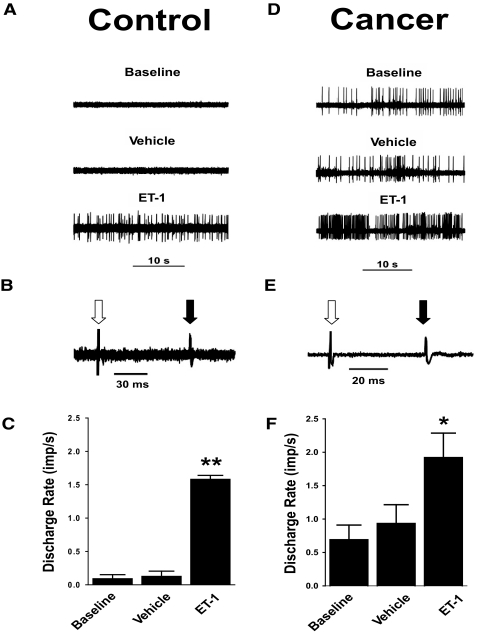

FIG. 1.

Responses of C nociceptors to injection of endothelin-1 (ET-1) in nontumor-bearing (control) and tumor-bearing (cancer) mice. A and D: ongoing activities of C nociceptors in a control mouse and in a tumor-bearing mouse before (baseline) and after injections of vehicle [10 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] and ET-1 (100 μM in 10 μl) into its receptive field (RF). B and E: 5 overlapping traces of the constant latency of electrically evoked excitation are illustrated for each C nociceptor. Open arrow, stimulus artifact; solid arrow, action potentials of each C nociceptor. C and F: mean ± SE discharge rate (imp/s) of ongoing activity for C nociceptors in control and tumor-bearing mice at baseline, after injection of vehicle, and after injection of ET-1 into their RFs. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.001 for the ongoing activity after injection of ET-1 compared with baseline levels and after injection of vehicle.

The mean discharge rate of ongoing activity for C nociceptors (n = 35) recorded in 28 control mice was 0.1 ± 0.1 imp/s at baseline. Thirty C nociceptors (in 25 mice) were injected with vehicle (10 μl PBS) into their RFs. Five minutes after the injection, the level of ongoing activity was unchanged (0.1 ± 0.1 imp/s). Ten C nociceptors (in 10 mice) were injected with vehicle and then 60 min later received 100 μM of ET-1 (in 10 μl) into their RFs. Another five nociceptors (in 5 mice) only received 100 μM of ET-1. Because no differences were observed in responses to ET-1 between the C nociceptors that had been previously injected with vehicle and those that had not, the data were pooled. Injection of ET-1 rapidly evoked responses of C nociceptors. The mean discharge rate of ongoing activity of C nociceptors (n = 15) increased from 0.1 ± 0.1 to 1.6 ± 0.6 imp/s by 5 min after injection of ET-1 (Fig. 1C). This mean discharge rate was greater than that of C nociceptors at baseline and than the rate produced by injection of vehicle (P < 0.001).

Similar responses to ET-1 were observed in tumor-bearing mice (Fig. 1D). This C nociceptor exhibited ongoing activity at a discharge rate of 1.4 imps/s at baseline, and 5 min after injection of vehicle (10 μl of PBS) into its RF, the discharge rate was 1.3 imp/s. Sixty minutes later, 100 μM of ET-1 (in 10 μl) was injected into the RF, and 5 min after the injection the discharge rate increased to 4.2 imps/s. The response of this C nociceptor to ET-1 was one of the most robust responses of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice.

When considering all C nociceptors studied, the mean discharge rate of ongoing activity of C nociceptors (n = 58) in tumor-bearing mice (1.0 ± 0.2 imp/s) was higher than that of C nociceptors (n = 46) in control mice (0.1 ± 0.1 imp/s; P < 0.001). Nineteen C nociceptors in 19 tumor-bearing mice were examined for the effect of injection of ET-1 on ongoing activity. At baseline, these C nociceptors exhibited a mean discharge rate of 0.7 ± 0.2 imp/s (Fig. 1F). Injection of vehicle did not alter the mean discharge rate (0.9 ± 0.3 imp/s) of C nociceptors (n = 11). However, as in control mice, injection of ET-1 into the RF of C nociceptors (n = 11) increased the mean discharge rate to 1.9 ± 0.4 imp/s (P < 0.05). Three C nociceptors received both vehicle and ET-1, but their responses did not differ from C nociceptors that had received either vehicle or ET-1 alone. Thus the data were pooled. The mean discharge rates of C nociceptors after injection of ET-1 were similar in control and tumor-bearing mice.

Previous studies have reported that injection of ET-1 into the receptive field of C nociceptors evoked impulses in bursting patterns (Gokin et al. 2001; Khordova et al. 2002). In control mice, neither of the two C nociceptors that exhibited ongoing activity displayed a bursting pattern. Of the 15 C nociceptors in control mice that received injection of ET-1 into their receptive fields, only 3 (20%) exhibited a bursting pattern to the ongoing activity after injection of ET-1. Mean intra-burst frequency was 2.6 ± 1.5 imp/s (range: 1.1 ± 0.3 to 5.6 ± 1.3 imp/s) and bursting periods lasted 5.1 ± 2.0 s (range: 3.1 ± 0.2 to 7.1 ± 2.2 s). Mean time between bursts was 8.8 ± 2.5 s (range: 5.9 ± 0.6 to 13.8 ± 5.6 s).

Eight of 58 (14%) C-nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice exhibited ongoing activity with periods of bursting. Mean intra-burst frequency was 1.1 ± 0.4 imp/s (range: 0.5 ± 0.1 to 1.5 ± 0.5 imp/s), and bursting periods lasted 11.5 ± 3.1 s (range: 2.3 ± 0.7 to 21.7 ± 1.3 s). Mean time between bursts was 19.7 ± 5.5 s (range: 3.8 ± 0.1 to 38.2 ± 11.1 s). There were no differences in the proportion of C nociceptors exhibiting bursting ongoing activity, mean intraburst frequencies, duration of bursting periods, or time between bursts between tumor-bearing mice and control mice following injection of ET-1 into the RFs.

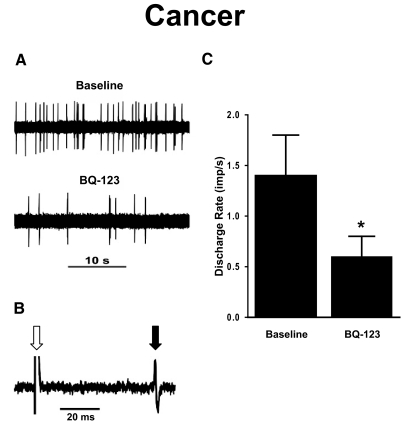

The effect of the ETA receptor antagonist, BQ-123, on ongoing activity was examined for 15 spontaneously active C nociceptors in 13 tumor-bearing mice. At baseline, their mean discharge rate was 1.4 ± 0.4 imp/s. Ten minutes after injection of BQ-123 (3 mM in 10 μl), mean discharge rate decreased to 0.6 ± 0.2 imp/s (P < 0.01, Fig. 2). Ongoing activity did not change further at 20 min after injection of BQ-123 (data not shown). In contrast, ongoing activity did not change following injection of vehicle. Thus injection of an ETA receptor selective antagonist into the RF reduced but did not completely abolish ongoing activity of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice.

FIG. 2.

The effect of the ETA receptor antagonist BQ-123 on ongoing activity of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing (cancer) mice. A: ongoing activity of a single C nociceptor before (baseline) and after injection of BQ-123 (3 mM in 10 μl). B: 5 overlapping traces of the constant latency of electrically evoked excitation of this C nociceptor are illustrated. Open arrow, stimulus artifact; solid arrow, action potential of this single C nociceptor. C: mean ± SE discharge rate of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice before and after injection of BQ-123. *, significant difference from baseline (P < 0.001).

Effect of ET-1 on responses of C nociceptors to heat

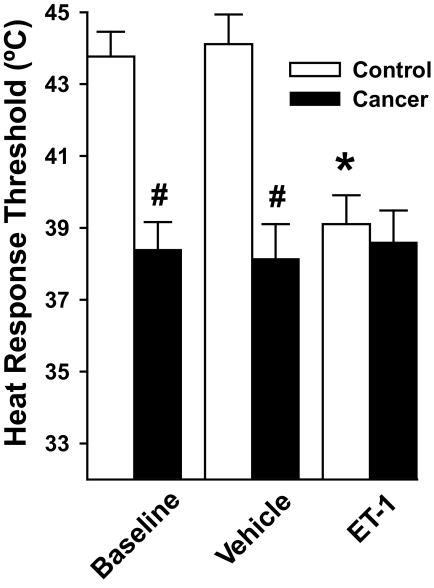

In control mice (n = 32), 34 of 41 (83%) C nociceptors were excited by heat stimuli (35 to 51°C) at baseline with a mean heat-response threshold of 43.8 ± 0.7°C (Fig. 3). Injection of vehicle into the RFs of 18 C nociceptors in 14 control mice did not significantly change their heat-response thresholds (44.1 ± 0.8°C). In contrast, injection of ET-1 (100 μM) into the RFs of 19 C nociceptors in 16 control mice reduced their heat-response threshold to 39.1 ± 0.8°C (P < 0.001).

FIG. 3.

Mean ± SE heat-response thresholds of C nociceptors in nontumor-bearing (control) and in tumor-bearing (cancer) mice before (baseline) and after injection of vehicle (10 μl of PBS) or ET-1 (100 μM in 10 μl). C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice exhibited lower heat-response thresholds than those in control mice at baseline and after injection of vehicle. Injection of ET-1 decreased the heat-response thresholds of C nociceptors in control mice to a level that was similar to heat-response thresholds of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice. *, significant difference from baseline (P < 0.001); #, significant differences from control mice (P < 0.001).

In 34 tumor-bearing mice, 24 of 34 (71%) C nociceptors were sensitive to heat at baseline, and their heat-response threshold (38.4 ± 0.8°C) was lower than that of C nociceptors in control mice (P < 0.001, Fig. 3). Injection of vehicle into the RFs of C nociceptors (n = 8) in eight tumor-bearing mice did not alter their heat-response threshold (38.1 ± 1.0°C). In contrast to its effect in control mice, injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors (n = 8) in eight tumor-bearing mice did not further reduce their heat-response threshold (38.6 ± 0.9°C) compared with baseline levels. Furthermore, the heat-response thresholds of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice at baseline were similar to the heat-response thresholds of C nociceptors in control mice after injection of ET-1 suggesting that ET-1 at the tumor site may contribute to the reduction in heat-response threshold of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice.

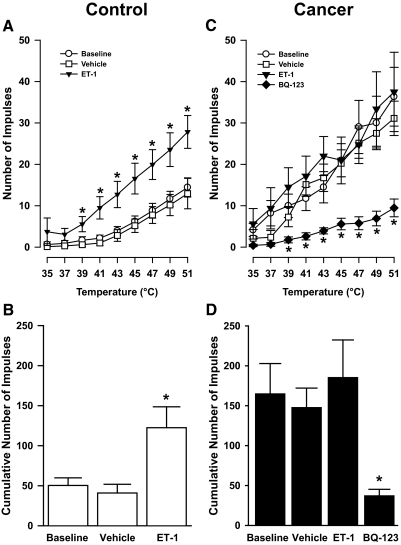

For C nociceptors (n = 34) in 32 control mice, the number of impulses evoked by heat increased as stimulus temperatures increased (P < 0.01, Fig. 4A). The mean cumulative number of impulses evoked by all heat stimuli at baseline was 50.3 ± 9.5 impulses (Fig. 4B). Injection of vehicle into the RF of 18 C nociceptors in 14 control mice did not alter the cumulative number of impulses evoked by the heat stimuli (40.9 ± 11.0). In contrast, injection of ET-1 into the RFs of 19 C nociceptors in 16 control mice increased the number of impulses evoked by heat stimuli at ≥39°C (P < 0.05). The mean cumulative number of impulses after injection of ET-1 (122.4 ± 26.1) was greater than that at baseline or after injection of vehicle (P < 0.01, Fig. 4B). Thus injection of ET-1 into the RF increased responses of C nociceptors in control mice to heat stimuli.

FIG. 4.

Effects of ET-1 and the ETA receptor antagonist BQ-123 on responses of C nociceptors to heat in control and in tumor-bearing (cancer) mice. A: mean ± SE stimulus-response functions for C nociceptors in control mice. B: mean ± SE cumulative number of impulses evoked by all heat stimuli before (baseline) and after injection of vehicle (10 μl of PBS) or ET-1 (100 μM in 10 μl) into the RFs of C nociceptors in control mice. C: mean ± SE stimulus-response functions for C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice. D: mean ± SE cumulative number of impulse before (baseline) and after injection of vehicle, ET-1, or BQ-123 (3 mM in 10 μl) into the RFs of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice. For A–C, *, significant difference from baseline and vehicle (P < 0.05). For D, *, significant difference from baseline, vehicle, and ET-1 (P < 0.005).

For C nociceptors (n = 24) in 24 tumor-bearing mice, the number of impulses evoked by heat also increased as stimulus temperatures increased (Fig. 4C). At baseline, each heat stimulus evoked a greater number of impulses from C nociceptors in tumor-bearing compared with those in control mice (P < 0.05). Interestingly, the number of impulses evoked by the heat stimuli in tumor-bearing mice were similar to the enhanced responses to heat stimuli in control mice after injection of ET-1. Furthermore, the cumulative number of impulses (164.8 ± 38.1) evoked by the heat stimuli in tumor-bearing mice at baseline was similar to that of C nociceptors in control mice (122.4 ± 26.1) following injection of ET-1. These findings suggest that injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors in control mice produced a level of sensitization to heat that was similar to that exhibited by C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice.

Injection of vehicle into the RFs of 8 C nociceptors in eight tumor-bearing mice did not change responses evoked by each heat stimulus (Fig. 4C) or by the series of heat stimuli (Fig. 4D). The cumulative number of impulses (147.6 ± 24.4) after injection of vehicle remained similar to baseline values (164.8 ± 38.1). In contrast to its effects on C nociceptors in control mice, injection of ET-1 into the RFs of eight C nociceptors in eight tumor-bearing mice did not increase their responses to the heat stimuli (Fig. 4, B and D). The cumulative number of impulses evoked by the series of heat stimuli after injection of ET-1 (185.3 ± 47.2) was not different from that at baseline or after injection of vehicle.

Thus C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice exhibited lower heat-response thresholds and increased responses to suprathreshold heat stimuli as compared with C nociceptors in control mice. Interestingly, the level of sensitization of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice was similar to that of C nociceptors in control mice after injection of ET-1 into the RF. These data suggest that release of ET-1 from the tumor or surrounding tissues could contribute to tumor-evoked sensitization of C nociceptors.

To investigate whether ETA receptors contributed to tumor-evoked sensitization of C nociceptors to heat, responses of 10 C nociceptors in 10 tumor-bearing mice to the heat stimuli were determined before and at 10 min following injection of BQ-123 into the RF. In 8 of the 10 C nociceptors, BQ-123 reduced the mean number of impulses evoked by heat stimuli of ≥39°C compared with baseline values (P < 0.05; Fig. 4C). The cumulative number of impulses evoked by the series of heat stimuli decreased from 158.9 ± 44.3 to 33.3 ± 8.0 impulses following injection of BQ-123 and was lower than baseline values (Fig. 4D, P < 0.005). These results suggest that ET-1 may contribute to tumor-evoked sensitization of nociceptors to heat through ETA receptors in the periphery.

DISCUSSION

As we have shown previously, C nociceptors in mice with tumor-evoked hyperalgesia exhibited ongoing activity, decreased heat-response thresholds, and increased responses to heat stimuli compared with C nociceptors in control mice (Cain et al. 2001). Injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors in control mice evoked ongoing activity, decreased heat-response thresholds, and increased responses to the heat stimuli to levels similar to those exhibited by C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice. In tumor-bearing mice, injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors increased the level of ongoing activity but did not further reduce heat-response thresholds or further increase responses to heat stimuli. Injection of an ETA receptor selective antagonist, BQ-123, into the RFs of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice attenuated the ongoing activity and returned their responses to heat stimuli to levels similar to those of C nociceptors in control mice. These results suggest that tumor-evoked hyperalgesia to heat is mediated, at least in part, by endothelin-evoked sensitization of C nociceptors that terminate in the skin overlying the tumor in this murine model of cancer pain. Furthermore, this sensitizing effect of endothelin appears to be mediated through the ETA receptor subtype.

In the present study, tumor-bearing mice were monitored for the development of mechanical but not heat hyperalgesia even though sensitization of C nociceptors occurred to heat but not mechanical stimuli. As we have shown previously, mechanical response thresholds of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice were not reduced compared with those in non-tumor-bearing mice (Cain et al. 2001). Indeed tumor-evoked mechanical hyperalgesia was mediated by sensitization of nociceptive dorsal horn neurons (Khasabov et al. 2007). However, C nociceptors were studied 9–16 days after implantation of fibrosarcoma cells, and during this period, both mechanical and heat hyperalgesia are present in this murine model of cancer pain (Khasabov et al. 2007). Thus although the mice in the present study were not examined for their behavioral responses to heat stimuli, they likely would have exhibited heat hyperalgesia as both tumor-evoked mechanical and heat hyperalgesia develop simultaneously.

BQ-123 was used to determine if the sensitization of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice was due to ET-1 acting on ETA receptors. BQ-123 was one of the first ET-1 receptor antagonists discovered and is highly selective for the ETA receptor subtype (Ihara et al. 1992a,b). Newer ETA-selective antagonists that have greater bioavailability when given orally have been developed and some (e.g., ABT-627 or Atrasentan and BMS-207940) are more potent and more selective than BQ-123 (Murugesan et al. 2003; Opgenorth et al. 1996; Verhaar et al. 2000). However, BQ-123 has been shown to effectively attenuate nocifensive behaviors and hyperalgesia when applied locally to the sciatic nerve (Davar et al. 1998), injected intra-articularly into the knee (Daher et al. 2004; De-Melo et al. 1998a), injected subcutaneously into the plantar surface of the hind paw, (Baamonde et al. 2004; Balonov et al. 2006; Gokin et al. 2001; Houck et al. 2004; Menendez et al. 2003b; Piovezan et al. 1998, 2004; Verri et al. 2004, 2005) or skin of the back (Mujenda et al. 2007), and injected into tumor-bearing tissues (Pickering et al. 2007; Schmidt et al. 2007; Wacnik et al. 2001). In contrast, the newer ETA receptor-selective antagonists have been administered systemically (Chichorro et al. 2006a; Klass et al. 2005; Matwyshyn et al. 2006; Piovezan et al. 2000; Trentin et al. 2006). Because we were interested in the role of ETA receptors near the tumor, presumably on the terminals of C nociceptors, we chose BQ-123 as the ETA receptor-selective antagonist as it has been shown to be effective when injected into peripheral tissues.

ET-1-evoked nocifensive behaviors and hyperalgesia

Injection of ET-1 into the knee or hind paw evokes nocifensive behaviors in animals (Baamonde et al. 2004; Balonov et al. 2006; De-Melo et al. 1998a; Ferreira et al. 1989; McKelvy et al. 2007; Piovezan et al. 1998, 2004; Verri et al. 2004, 2005). For example, injection of ET-1 into the plantar surface of the hind paw evoked dose-dependent hind paw licking (Gokin et al. 2001; Menendez et al. 2003b; Piovezan et al. 2000), and application of ET-1 directly to the sciatic nerve evoked robust hind paw flinching (Davar et al. 1998; Fareed et al. 2000). Injection of ET-1 into the hind paw also produced tactile allodynia (Balonov et al. 2006; McKelvy et al. 2007), and mechanical (da Cunha et al. 2004; Ferreira et al. 1989) and heat (Menendez et al. 2003b) hyperalgesia. Furthermore, local administration of ET-1 potentiated nocifensive behaviors evoked by intraplantar injection of capsaicin (Piovezan et al. 1998) or formalin (Piovezan et al. 1997; Yuyama et al. 2004a) and intra-articular injection of an inflammatory evoking substance, carrageenan (Daher et al. 2004; De-Melo et al. 1998b), or prostaglandin E2 (Ferreira et al. 1989).

In humans, early studies reported that intradermal injection of ET-1 evoked mechanical hyperalgesia (Ferreira et al. 1989), whereas intra-arterial injection of ET-1 evoked deep muscular pain that was intensified by touch (Dahlof et al. 1990). More recently, it has been reported that intradermal injection of ET-1 produced a short-lasting spontaneous pain and longer-lasting mechanical and cold hyperalgesia (Hans et al. 2007; Namer et al. 2007).

The mechanisms by which injection of ET-1 into peripheral tissues evokes nocifensive behaviors and hyperalgesia to heat appears to be mediated through the ETA receptor as pretreatment with systemic (i.e., atrasentan or A-127722-5) or local (i.e., BQ-123) ETA receptor-selective antagonists or co-application of BQ-123 with ET-1, attenuated these effects (Baamonde et al. 2004; Davar et al. 1998; De-Melo et al. 1998a; Fareed et al. 2000; Gokin et al. 2001; Menendez et al. 2003b; Piovezan et al. 2000). In contrast, pretreatment with or co-application of ETB receptor-selective antagonists (e.g., BQ-788) did not attenuate the ET-1-evoked nocifensive behaviors or heat hyperalgesia (Baamonde et al. 2004; Davar et al. 1998; De-Melo et al. 1998a; Fareed et al. 2000; Menendez et al. 2003b; Piovezan et al. 2000). The potentiating effect of ET-1 on nocifensive behaviors evoked by capsaicin, formalin, or inflammation was also mediated through the ETA, but not ETB, receptor subtype (Daher et al. 2004; Piovezan et al. 1998; Yuyama et al. 2004a).

ETB receptors appear to contribute to ET-1-evoked mechanical hyperalgesia (Baamonde et al. 2004; da Cunha et al. 2004). However, the contribution of ETA receptors to ET-1-evoked mechanical hyperalgesia is unclear as pretreatment with BQ-123 has been reported to either block (Baamonde et al. 2004) or fail to block (da Cunha et al. 2004) ET-1-evoked mechanical hyperalgesia.

Thus injection of ET-1 into peripheral tissues evokes nocifensive behaviors and mechanical and heat hyperalgesia in animals and evokes pain, mechanical, and cold hyperalgesia in humans. ET-1 also potentiates subsequent nocifensive behaviors evoked by capsaicin, formalin, or inflammation. These effects are for the most part mediated by ETA, but not ETB, receptors in the peripheral tissues. However, ETB receptors appear to contribute to ET-1 evoked mechanical hyperalgesia. These effects of ET-1 could contribute to tumor-evoked spontaneous pain and mechanical, heat, and cold hyperalgesia observed in the murine model of cancer pain used in the present study (Hamamoto et al. 2007; Khasabov et al. 2007; Wacnik et al. 2001).

Role of ET-1 in inflammatory, neuropathic, and tumor-evoked hyperalgesia

Activation of endothelin receptors contributes to inflammatory, neuropathic, and tumor-evoked hyperalgesia. For example, intraplantar injection of BQ-123 attenuated mechanical and heat hyperalgesia evoked by inflammatory agents, such as carrageenan or complete Freund's adjuvant (Baamonde et al. 2004). In contrast, an ETB receptor-selective antagonist, BQ-788, attenuated inflammation-evoked mechanical but not heat hyperalgesia. Similarly BQ-788, but not BQ-123, blocked mechanical hyperalgesia produced by intraplantar injection of the proinflammatory cytokines interleukin 12 (Verri et al. 2005) and interleukin 18 (Verri et al. 2004). Postincisional pain may be due, at least in part, to inflammation and pretreatment of the skin with BQ-123 prior to the incision attenuates mechanical allodynia (Mujenda et al. 2007). Thus ETA receptors contribute to mechanical allodynia and mechanical and heat hyperalgesia, whereas ETB receptors contribute only to mechanical hyperalgesia in these models of inflammation.

In models of neuropathic pain, the endothelin receptor subtype that is involved depends on the model and the type of hyperalgesia (i.e., mechanical or thermal). For example, systemic administration of an ETA receptor-selective antagonist attenuated mechanical allodynia in the streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat model of neuropathic pain (Jarvis et al. 2000) and heat and mechanical hyperalgesia produced by chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve (Klass et al. 2005). However, a similar constriction injury to the infraorbital nerve produced mechanical allodynia that was attenuated by systemic administration of an ETB receptor-selective antagonist (Chichorro et al. 2006a). Interestingly, this same model of neuropathic pain produced cold hyperalgesia that was attenuated by administration of either ETA or ETB receptor-selective antagonists into the lip (Chichorro et al. 2006b).

Release of ET-1 from tumor cells may contribute to tumor-evoked pain and hyperalgesia (Davar 2001). In animal models of tumor-evoked hyperalgesia, including the model used in the present study, expression of ET-1 was increased in tumor-bearing tissues (Peters et al. 2004; Schmidt et al. 2007; Wacnik et al. 2001) and administration ETA receptor selective antagonists into tumor-bearing tissues attenuated tumor-evoked hyperalgesia (Pickering et al. 2007; Schmidt et al. 2007; Wacnik et al. 2001). Administration of ET-1 into tumor-bearing hind paws of mice potentiated tumor-evoked nocifensive behaviors, and this potentiation was attenuated by blockade of ETA receptors (Yuyama et al. 2004a,b). In humans, systemic administration of ETA receptor-selective antagonists attenuated pain associated with prostate cancer (Carducci et al. 2002). Thus release of ET-1 from tumor cells could contribute to tumor-evoked hyperalgesia perhaps via excitation and sensitization of C nociceptors.

ET-1-evoked excitation of C nociceptors

We confirmed our previous findings demonstrating that a subpopulation of C nociceptors exhibit ongoing activity, decreased response thresholds to heat, and increased responses to suprathreshold heat stimuli (Cain et al. 2001). In the present study, a greater proportion (84%) of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice exhibited ongoing activity compared with our previous report (34%). This difference arose because in the present study we searched primarily for sensitized C nociceptors as indicated by ongoing activity. However, the discharge rate of ongoing activity, mechanical and heat-response thresholds, and responses to the heat stimuli were similar in the two studies, suggesting that the C nociceptors in the present study were from the same subpopulation of C nociceptors that we originally described.

Injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors in nontumor-bearing mice evoked ongoing activity. This finding is consistent with previous studies in which C nociceptors in rats were excited by injection of ET-1 (Gokin et al. 2001; Khodorova et al. 2002) and likely contributes to ET-1-evoked nocifensive behaviors. The latency from the time of injection of ET-1 to excitation of C nociceptors in rats ranged from 1.2 to 5.6 min with a mean of 3.16 ± 0.31 (SE) min (Gokin et al. 2001; Khodorova et al. 2002). We also observed that the latency to excitation varied between C nociceptors. Thus we determined the level of ongoing activity 5 min after injection of ET-1 to allow sufficient time for the majority of C nociceptors to respond. Recording ongoing activity of C nociceptors at 5 min after injection of ET-1 coincides well with a recent report that pain evoked by ET-1 in humans was maximal between 4 and 5 min after intracutaneous injection (Namer et al. 2007). Because the duration of responses to ET-1 of C nociceptors ranged from 15 to 40 min (Gokin et al. 2001; Khodorova et al. 2002), it is unlikely that many C nociceptors responded to the ET-1 earlier but did not exhibit ongoing activity at 5 min.

A subpopulation (14%) of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice exhibited bursting patterns of ongoing activity. A similar proportion (20%) of C nociceptors in nontumor-bearing mice exhibited bursting patterns of ongoing activity after injection of ET-1 into their RFs. The patterns of bursting were similar in mean intra-burst frequencies, durations, and intervals between bursting periods in C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice and in nontumor- bearing mice after injection of ET-1. Administration of bradykinin or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) to the RF produces bursts of impulses in a proportion of C nociceptors in rats (Banik et al. 2001; Sorkin et al. 1997). Injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors in rats evoked ongoing activity that exhibited bursting patterns with peak intra-burst frequencies of ∼3 imp/s, periods of bursting that lasted 10–15 s, and intervals between bursts of ∼50 s following injection of ET-1 (Gokin et al. 2001; Khodorova et al. 2002). In the present study, nontumor-bearing mice exhibited bursting periods (5.1 ± 2.0 s) and time between bursts (8.8 ± 2.5 s) that were shorter than those reported for rats. However, the dose of ET-1 (16–20 nmol) administered to the rats was higher that the dose (100 μM in 10 μl = 1 nmol) administered to the nontumor-bearing mice in the present study. Thus ET-1 released at the tumor site may contribute to excitation of C nociceptors, some of which exhibit a bursting pattern of ongoing activity.

In healthy human volunteers, electrophysiological responses of mechanosensitive and -insensitive C nociceptors to intracutaneous injection of ET-1 into hairy skin were examined using microneurography (Namer et al. 2007). Injection of ET-1 into their RFs excited 65% of mechanosensitive C nociceptors but none of the mechanoinsensitive C nociceptors. Interestingly, the latency to excitation [31.4 ± 4.8 (SE) s] and duration of the excitation (8.3 ± 1.5 min) were shorter for C nociceptors in humans than for C nociceptors in rats (3.16 ± 0.31 and 30 ± 3 min, respectively) (Gokin et al. 2001; Khodorova et al. 2002) even though the dose of ET-1 was lower (10 μl of 1 μM) for humans than for the rats (50 μl of 400 μM). This may represent differences in sensitivity to or activation by ET-1 between nociceptors in humans and in rats or differences between nociceptors located in hairy and glabrous skin.

In the present study, the level of ongoing activity evoked by ET-1 in nontumor-bearing mice was similar to that of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice. Because ongoing activity of nociceptors may contribute to persistent pain (Djouhri et al. 2006), and persistent pain often occurs with bone cancer in humans (Banning et al. 1991; Mercadante 1997; Sarlak et al. 2000), ongoing activity in C nociceptors evoked by ET-1 may contribute to the tumor-evoked nocifensive behaviors reported previously (Wacnik et al. 2001). In support of this idea, injection of BQ-123 into the RF of C nociceptors attenuated ongoing activity and nocifensive behaviors in tumor-bearing mice (Wacnik et al. 2001).

Intraplantar injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice further increased their ongoing activity indicating that sensitivity of C nociceptors to ET-1 is maintained in tumor-bearing tissues. This ET-1 evoked increase in ongoing activity of C nociceptors could contribute the increase in nocifensive behaviors produced by ET-1 in this murine model of cancer pain (Wacnik et al. 2001). The ET-1 evoked increase in ongoing activity of C nociceptors was attenuated by injection of BQ-123 (Gokin et al. 2001). Thus the ongoing activity of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice could be due to the effects of ET-1 on ETA receptors in the tumor-bearing tissues and contribute to tumor-evoked nocifensive behaviors in this model and other models of cancer pain (Honore et al. 2000; Schwei et al. 1999; Wacnik et al. 2001).

ET-1-evoked sensitization of C nociceptors

In nontumor-bearing mice, injection of ET-1 into the RFs of C nociceptors decreased heat-response thresholds and increased responses to suprathreshold heat stimuli. This is a novel finding because although hyperalgesia to heat produced by ET-1 has been reported (Menendez et al. 2003b), previous studies in rats did not examine the effect of ET-1 on the electrophysiological responses of C nociceptors to heat (Gokin et al. 2001; Khodorova et al. 2002). In humans, injection of ET-1 into the RF sensitized 60% of mechanosensitive C nociceptors to heat as response thresholds decreased from 40.1 to 38.7°C (Namer et al. 2007). In the present study, heat-response thresholds in nontumor-bearing mice decreased from 43.8 ± 0.7 to 39.1 ± 0.8°C. Thus although heat-response thresholds were higher for C nociceptors in mice than in humans, injection of ET-1 in the RFs decreased heat-response thresholds to a similar level. Thus sensitization of C nociceptors to heat may be the neurophysiological mechanism by which ET-1 induces heat hyperalgesia. Interestingly, the decrease in heat-response thresholds and increase in responses to suprathreshold heat stimuli produced by ET-1 in nontumor-bearing mice was similar to that observed for C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice in the present study and to those that we reported previously (Cain et al. 2001), suggesting that ET-1 in tumor-bearing tissue contributes to sensitization of C nociceptors to heat in tumor-bearing mice.

Injection of BQ-123 into the RF of sensitized C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice returned their responses to suprathreshold heat stimuli back to levels exhibited by C nociceptors in nontumor-bearing mice. Peripheral administration of ET-1 into the tumor-bearing hind paw did not further sensitize C nociceptors to heat as heat-response thresholds, and responses to suprathreshold heat stimuli did not change. This finding suggests that the tumor-evoked sensitization of C nociceptors to heat may have been maximal. Whether injection of ET-1 into tumor-bearing tissues increases the level of heat hyperalgesia has not been reported. Thus tonic release of ET-1 in tumor-bearing tissues may act via ETA receptors to induce sensitization of C nociceptors to heat stimuli and contribute to the heat hyperalgesia observed in this model of cancer pain (Khasabov et al. 2007). BQ-123 returned the responses of C nociceptors to heat stimuli in tumor-bearing mice back to levels exhibited by nontumor-bearing mice but only partially attenuated tumor-evoked ongoing activity. It is possible that tumor-evoked heat hyperalgesia is mainly due to ET-1 induced sensitization of C nociceptors to heat but that tumor-evoked ongoing nocifensive behaviors are only partially mediated by ET-1 evoked excitation of C nociceptors. However, higher doses of BQ-123 were not evaluated in the present study leaving open the possibility that our dose of BQ-123 was not high enough to fully block ET-A receptors.

Mechanisms of ET-1-evoked excitation and sensitization of C nociceptors

Excitation of C nociceptors in tumor-bearing mice may be due to a direct effect of ET-1 as application of ET-1 to the sciatic nerve produced nocifensive behaviors in an ETA receptor-dependent manner (Davar et al. 1998). ETA, but not ETB, receptors are expressed on small-diameter CGRP-immunoreactive dorsal root ganglion neurons and axons (Peters et al. 2004; Pomonis et al. 2001) that likely detect nociceptive stimuli (Lawson et al. 2002). Further evidence for direct excitation of C nociceptors by ET-1 is that ET-1 induced dose and ETA receptor-dependent release of intracellular Ca2+ in nociceptor-like neurons (Zhou et al. 2001). Also ET-1 produced an ETA receptor-dependent hyperpolarizing shift in the voltage-dependent activation of tetrodotoxin-resistant (TTX-R) sodium channels in isolated dorsal root ganglion neurons (Zhou et al. 2002). Such a shift could increase membrane excitability and render the neuron more susceptible to generating action potentials. TTX-R sodium channels are found exclusively in small-diameter dorsal root ganglion neurons associated with nociceptive properties (Amaya et al. 2000; Elliott and Elliott 1993; Fjell et al. 2000), and hyperpolarizing shifts in TTX-R sodium channel activation are associated with treatments that sensitize nociceptors and produce hyperalgesia (Gold et al. 1996; Kral et al. 1999). Application of TTX to the sciatic nerve before application of ET-1 at a more distal site of the nerve did not attenuate ET-1-evoked nocifensive behaviors, suggesting that ET-1-evoked nociception is transmitted to the CNS via primary afferent fibers using TTX-R sodium channels (Houck et al. 2004).

The mechanisms by which ET-1 produces sensitization of C nociceptors to heat are unclear. One possibility is that ET-1 modulates function of the capsaicin receptor, TRPV1, which is a transducer for noxious heat (Caterina and Julius 1999; Caterina et al. 1997; Tominaga et al. 1998). ET-1 enhanced capsaicin-evoked release of intracellular Ca2+ (Yamamoto et al. 2006) and neuropeptides [calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and substance P] (Dymshitz and Vasko 1994) in cultured dorsal root ganglion neurons and potentiated capsaicin-evoked hyperalgesia (Piovezan et al. 2000), suggesting that ET-1 might enhance activity at TRPV1 receptors.

Conclusions

The present study confirms our earlier findings that a subset of C nociceptors that innervate the skin overlying a tumor develop ongoing activity and sensitization to heat (Cain et al. 2001). We now provide electrophysiological evidence suggesting that ET-1 contributes to tumor-evoked ongoing activity and sensitization of C nociceptors to heat and that these effects of ET-1 occur through ETA receptors. Because ET-1 is expressed by several human cancer cell lines and stimulates proliferation of some cancer cell lines via an ETA receptor-mediated mechanism and because blockade of ETA receptors attenuates tumor-evoked nocifensive behaviors and sensitization of C nociceptors in animals, targeting of ETA receptors may be a beneficial therapeutic approach for the management of pain associated with certain cancers in humans.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants CA-91007 and DA-011471 to D. A. Simone and Civilian Research and Development Foundation Grant UKB1-2615-KV-04 to D. A. Simone.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Harding-Rose and C. Biorn for technical assistance in culturing and implanting the fibrosarcoma cells.

Present address of D. M. Cain: Algos Therapeutics, St. Paul, Minnesota, 55104.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- Amaya et al. 2000.Amaya F, Decosterd I, Samad TA, Plumpton C, Tate S, Mannion RJ, Costigan M, Woolf CJ. Diversity of expression of the sensory neuron-specific TTX-resistant voltage-gated sodium ion channels SNS and SNS2. Mol Cell Neurosci 15: 331–342, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai et al. 1990.Arai H, Hori S, Aramori I, Ohkubo H, Nakanishi S. Cloning and expression of a cDNA encoding an endothelin receptor. Nature 348: 730–732, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baamonde et al. 2004.Baamonde A, Lastra A, Villazon M, Bordallo J, Hidalgo A, Menendez L. Involvement of endogenous endothelins in thermal and mechanical inflammatory hyperalgesia in mice. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 369: 245–251, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balonov et al. 2006.Balonov K, Khodorova A, Strichartz GR. Tactile allodynia initiated by local subcutaneous endothelin-1 is prolonged by activation of TRPV-1 receptors. Exp Biol Med 231: 1165–1170, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banik et al. 2001.Banik RK, Kozaki Y, Sato J, Gera L, Mizumura K. B2 receptor-mediated enhanced bradykinin sensitivity of rat cutaneous C-fiber nociceptors during persistent inflammation. J Neurophysiol 86: 2727–2735, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banning et al. 1991.Banning A, Sjogren P, Henriksen H. Pain causes in 200 patients referred to a multidisciplinary cancer pain clinic. Pain 45: 45–48, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain et al. 2001a.Cain DM, Khasabov SG, Simone DA. Response properties of mechanoreceptors and nociceptors in mouse glabrous skin: an in vivo study. J Neurophysiol 85: 1561–1574, 2001a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cain et al. 2001b.Cain DM, Wacnik PW, Turner M, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy WR, Wilcox GL, Simone DA. Functional interactions between tumor and peripheral nerve: changes in excitability and morphology of primary afferent fibers in a murine model of cancer pain. J Neurosci 21: 9367–9376, 2001b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carducci et al. 2002.Carducci MA, Nelson JB, Bowling MK, Rogers T, Eisenberger MA, Sinibaldi V, Donehower R, Leahy TL, Carr RA, Isaacson JD, Janus TJ, Andre A, Hosmane BS, Padley RJ. Atrasentan, an endothelin-receptor antagonist for refractory adenocarcinomas: safety and pharmacokinetics. J Clin Oncol 20: 2171–2180, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina and Julius 1999.Caterina MJ, Julius D. Sense and specificity: a molecular identity for nociceptors. Curr Opin Neurobiol 9: 525–530, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caterina et al. 1997.Caterina MJ, Schumacher MA, Tominaga M, Rosen TA, Levine JD, Julius D. The capsaicin receptor: a heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 389: 816–824, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichorro et al. 2006a.Chichorro JG, Zampronio AR, Rae GA. Endothelin ET(B) receptor antagonist reduces mechanical allodynia in rats with trigeminal neuropathic pain. Exp Biol Med 231: 1136–1140, 2006a. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichorro et al. 2006b.Chichorro JG, Zampronio AR, Souza GE, Rae GA. Orofacial cold hyperalgesia due to infraorbital nerve constriction injury in rats: reversal by endothelin receptor antagonists but not non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Pain 123: 64–74, 2006b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Cunha et al. 2004.da Cunha JM, Rae GA, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ. Endothelins induce ETB receptor-mediated mechanical hypernociception in rat hindpaw: roles of cAMP and protein kinase C. Eur J Pharmacol 501: 87–94, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher et al. 2004.Daher JB, Souza GE, D'Orleans-Juste P, Rae GA. Endothelin ETB receptors inhibit articular nociception and priming induced by carrageenan in the rat knee-joint. Eur J Pharmacol 496: 77–85, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlof et al. 1990.Dahlof B, Gustafsson D, Hedner T, Jern S, Hansson L. Regional haemodynamic effects of endothelin-1 in rat and man: unexpected adverse reaction. J Hypertens 8: 811–817, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davar 2001.Davar G Endothelin-1 and metastatic cancer pain. Pain Med 2: 24–27, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davar et al. 1998.Davar G, Hans G, Fareed MU, Sinnott C, Strichartz G. Behavioral signs of acute pain produced by application of endothelin-1 to rat sciatic nerve. Neuroreport 9: 2279–2283, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De-Melo et al. 1998a.De-Melo JD, Tonussi CR, D'Orleans-Juste P, Rae GA. Articular nociception induced by endothelin-1, carrageenan and LPS in naive and previously inflamed knee-joints in the rat: inhibition by endothelin receptor antagonists. Pain 77: 261–269, 1998a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De-Melo et al. 1998b.De-Melo JD, Tonussi CR, D'Orleans-Juste P, Rae GA. Effects of endothelin-1 on inflammatory incapacitation of the rat knee joint. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 31 Suppl 1: S518–520, 1998b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djouhri et al. 2006.Djouhri L, Koutsikou S, Fang X, McMullan S, Lawson SN. Spontaneous pain, both neuropathic and inflammatory, is related to frequency of spontaneous firing in intact C-fiber nociceptors. J Neurosci 26: 1281–1292, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dymshitz and Vasko 1994.Dymshitz J, Vasko MR. Endothelin-1 enhances capsaicin-induced peptide release and cGMP accumulation in cultures of rat sensory neurons. Neurosci Lett 167: 128–132, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrenreich et al. 1990.Ehrenreich H, Anderson RW, Fox CH, Rieckmann P, Hoffman GS, Travis WD, Coligan JE, Kehrl JH, Fauci AS. Endothelins, peptides with potent vasoactive properties, are produced by human macrophages. J Exp Med 172: 1741–1748, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott and Elliott 1993.Elliott AA, Elliott JR. Characterization of TTX-sensitive and TTX-resistant sodium currents in small cells from adult rat dorsal root ganglia. J Physiol 463: 39–56, 1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fareed et al. 2000.Fareed MU, Hans GH, Atanda A, Strichartz GR, Davar G. Pharmacological characterization of acute pain behavior produced by application of endothelin-1 to rat sciatic nerve. J Pain 1: 46–53, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira et al. 1989.Ferreira SH, Romitelli M, de Nucci G. Endothelin-1 participation in overt and inflammatory pain. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 13 Suppl 5: S220–222, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fjell et al. 2000.Fjell J, Hjelmstrom P, Hormuzdiar W, Milenkovic M, Aglieco F, Tyrrell L, Dib-Hajj S, Waxman SG, Black JA. Localization of the tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium channel NaN in nociceptors. Neuroreport 11: 199–202, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giaid et al. 1989.Giaid A, Gibson SJ, Ibrahim BN, Legon S, Bloom SR, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Varndell IM, Polak JM. Endothelin 1, an endothelium-derived peptide, is expressed in neurons of the human spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86: 7634–7638, 1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilchrist et al. 2005.Gilchrist LS, Cain DM, Harding-Rose C, Kov AN, Wendelschafer-Crabb G, Kennedy WR, Simone DA. Re-organization of P2X3 receptor localization on epidermal nerve fibers in a murine model of cancer pain. Brain Res 1044: 197–205, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohji et al. 2001.Gohji K, Kitazawa S, Tamada H, Katsuoka Y, Nakajima M. Expression of endothelin receptor a associated with prostate cancer progression. J Urol 165: 1033–1036, 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokin et al. 2001.Gokin AP, Fareed MU, Pan HL, Hans G, Strichartz GR, Davar G. Local injection of endothelin-1 produces pain-like behavior and excitation of nociceptors in rats. J Neurosci 21: 5358–5366, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold et al. 1996.Gold MS, Reichling DB, Shuster MJ, Levine JD. Hyperalgesic agents increase a tetrodotoxin-resistant Na+ current in nociceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 1108–1112, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant et al. 2003.Grant K, Loizidou M, Taylor I. Endothelin-1: a multifunctional molecule in cancer. Br J Cancer 88: 163–166, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamamoto et al. 2007.Hamamoto DT, Giridharagopalan S, Simone DA. Acute and chronic administration of the cannabinoid receptor agonist CP 55,940 attenuates tumor-evoked hyperalgesia. Eur J Pharmacol 558: 73–87, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hans et al. 2007.Hans G, Deseure K, Robert D, De Hert S. Neurosensory changes in a human model of endothelin-1 induced pain: a behavioral study. Neurosci Lett 418: 117–121, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honore et al. 2000.Honore P, Luger NM, Sabino MA, Schwei MJ, Rogers SD, Mach DB, O'Keefe PF, Ramnaraine ML, Clohisy DR, Mantyh PW. Osteoprotegerin blocks bone cancer-induced skeletal destruction, skeletal pain and pain-related neurochemical reorganization of the spinal cord. Nat Med 6: 521–528, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck et al. 2004.Houck CS, Khodorova A, Reale AM, Strichartz GR, Davar G. Sensory fibers resistant to the actions of tetrodotoxin mediate nocifensive responses to local administration of endothelin-1 in rats. Pain 110: 719–726, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara et al. 1992a.Ihara M, Ishikawa K, Fukuroda T, Saeki T, Funabashi K, Fukami T, Suda H, Yano M. In vitro biological profile of a highly potent novel endothelin (ET) antagonist BQ-123 selective for the ETA receptor. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 20 Suppl 12: S11–14, 1992a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihara et al. 1992b.Ihara M, Noguchi K, Saeki T, Fukuroda T, Tsuchida S, Kimura S, Fukami T, Ishikawa K, Nishikibe M, Yano M. Biological profiles of highly potent novel endothelin antagonists selective for the ETA receptor. Life Sci 50: 247–255, 1992b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis et al. 2000.Jarvis MF, Wessale JL, Zhu CZ, Lynch JJ, Dayton BD, Calzadilla SV, Padley RJ, Opgenorth TJ, Kowaluk EA. ABT-627, an endothelin ET(A) receptor-selective antagonist, attenuates tactile allodynia in a diabetic rat model of neuropathic pain. Eur J Pharmacol 388: 29–35, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khasabov et al. 2007.Khasabov SG, Hamamoto DT, Harding-Rose C, Simone DA. Tumor-evoked hyperalgesia and sensitization of nociceptive dorsal horn neurons in a murine model of cancer pain. Brain Res 1180: 7–19, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodorova et al. 2002.Khodorova A, Fareed MU, Gokin A, Strichartz GR, Davar G. Local injection of a selective endothelin-B receptor agonist inhibits endothelin-1-induced pain-like behavior and excitation of nociceptors in a naloxone-sensitive manner. J Neurosci 22: 7788–7796, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klass et al. 2005.Klass M, Hord A, Wilcox M, Denson D, Csete M. A role for endothelin in neuropathic pain after chronic constriction injury of the sciatic nerve. Anesth Analg 101: 1757–1762, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral et al. 1999.Kral MG, Xiong Z, Study RE. Alteration of Na+ currents in dorsal root ganglion neurons from rats with a painful neuropathy. Pain 81: 15–24, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuhara et al. 1990.Kusuhara M, Yamaguchi K, Nagasaki K, Hayashi C, Suzaki A, Hori S, Handa S, Nakamura Y, Abe K. Production of endothelin in human cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 50: 3257–3261, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson et al. 2002.Lawson SN, Crepps B, Perl ER. Calcitonin gene-related peptide immunoreactivity and afferent receptive properties of dorsal root ganglion neurones in guinea-pigs. J Physiol 540: 989–1002, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCumber et al. 1990.MacCumber MW, Ross CA, Snyder SH. Endothelin in brain: receptors, mitogenesis, and biosynthesis in glial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 2359–2363, 1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matwyshyn et al. 2006.Matwyshyn GA, Bhalla S, Gulati A. Endothelin ETA receptor blockade potentiates morphine analgesia but does not affect gastrointestinal transit in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 543: 48–53, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKelvy et al. 2007.McKelvy AD, Mark TR, Sweitzer SM. Age- and sex-specific nociceptive response to endothelin-1. J Pain 8: 657–666, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medhurst et al. 2002.Medhurst SJ, Walker K, Bowes M, Kidd BL, Glatt M, Muller M, Hattenberger M, Vaxelaire J, O'Reilly T, Wotherspoon G, Winter J, Green J, Urban L. A rat model of bone cancer pain. Pain 96: 129–140, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez 2003a.Menendez L, Lastra A, Fresno MF, Llames S, Meana A, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A. Initial thermal heat hypoalgesia and delayed hyperalgesia in a murine model of bone cancer pain. Brain Res 969: 102–109, 2003a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menendez 2003b.Menendez L, Lastra A, Hidalgo A, Baamonde A. Nociceptive reaction and thermal hyperalgesia induced by local ET-1 in mice: a behavioral and Fos study. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 367: 28–34, 2003b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercadante 1997.Mercadante S Malignant bone pain: pathophysiology and treatment. Pain 69: 1–18, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mujenda et al. 2007.Mujenda FH, Duarte AM, Reilly EK, Strichartz GR. Cutaneous endothelin-A receptors elevate post-incisional pain. Pain 133: 161–173, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan et al. 2003.Murugesan N, Gu Z, Spergel S, Young M, Chen P, Mathur A, Leith L, Hermsmeier M, Liu EC, Zhang R, Bird E, Waldron T, Marino A, Koplowitz B, Humphreys WG, Chong S, Morrison RA, Webb ML, Moreland S, Trippodo N, Barrish JC. Biphenylsulfonamide endothelin receptor antagonists. IV. Discovery of N-[[2′-[[(4,5-dimethyl-3-isoxazolyl)amino]sulfonyl]-4-(2-oxazolyl)[1,1′-bi phenyl]-2-yl]methyl]-N,3,3-trimethylbutanamide (BMS-207940), a highly potent and orally active ET(A) selective antagonist. J Med Chem 46: 125–137, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Namer et al. 2007.Namer B, Hilliges M, Orstavik K, Schmidt R, Weidner C, Torebjork E, Handwerker H, Schmelz M. Endothelin1 activates and sensitizes human C-nociceptors. Pain doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.08.008, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nelson 2005.Nelson JB Endothelin receptor antagonists. World J Urol 23: 19–27, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson and Carducci 2000.Nelson JB, Carducci MA. The role of endothelin-1 and endothelin receptor antagonists in prostate cancer. BJU Int 85 Suppl 2: 45–48, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson et al. 1996.Nelson JB, Chan-Tack K, Hedican SP, Magnuson SR, Opgenorth TJ, Bova GS, Simons JW. Endothelin-1 production and decreased endothelin B receptor expression in advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res 56: 663–668, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Opgenorth et al. 1996.Opgenorth TJ, Adler AL, Calzadilla SV, Chiou WJ, Dayton BD, Dixon DB, Gehrke LJ, Hernandez L, Magnuson SR, Marsh KC, Novosad EI, Von Geldern TW, Wessale JL, Winn M, Wu-Wong JR. Pharmacological characterization of A-127722: an orally active and highly potent ETA-selective receptor antagonist. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 276: 473–481, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters et al. 2004.Peters CM, Lindsay TH, Pomonis JD, Luger NM, Ghilardi JR, Sevcik MA, Mantyh PW. Endothelin and the tumorigenic component of bone cancer pain. Neuroscience 126: 1043–1052, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickering et al. 2007.Pickering V, Jay Gupta R, Quang P, Jordan RC, Schmidt BL. Effect of peripheral endothelin-1 concentration on carcinoma-induced pain in mice. Eur J Pain 12: 293–300, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovezan et al. 2004.Piovezan AP, D'Orleans-Juste P, Frighetto M, Souza GE, Henriques MG, Rae GA. Endothelins contribute towards nociception induced by antigen in ovalbumin-sensitised mice. Br J Pharmacol 141: 755–763, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovezan et al. 2000.Piovezan AP, D'Orleans-Juste P, Souza GE, Rae GA. Endothelin-1-induced ET(A) receptor-mediated nociception, hyperalgesia and oedema in the mouse hind-paw: modulation by simultaneous ET(B) receptor activation. Br J Pharmacol 129: 961–968, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovezan et al. 1997.Piovezan AP, D'Orleans-Juste P, Tonussi CR, Rae GA. Endothelins potentiate formalin-induced nociception and paw edema in mice. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 75: 596–600, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piovezan et al. 1998.Piovezan AP, D'Orleans-Juste P, Tonussi CR, Rae GA. Effects of endothelin-1 on capsaicin-induced nociception in mice. Eur J Pharmacol 351: 15–22, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomonis et al. 2001.Pomonis JD, Rogers SD, Peters CM, Ghilardi JR, Mantyh PW. Expression and localization of endothelin receptors: implications for the involvement of peripheral glia in nociception. J Neurosci 21: 999–1006, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portenoy et al. 1999.Portenoy RK, Payne D, Jacobsen P. Breakthrough pain: characteristics and impact in patients with cancer pain. Pain 81: 129–134, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai et al. 1990.Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature 348: 732–735, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarlak et al. 2000.Sarlak A, Gundes H, Ozkurkcugil C, Ozkara S, Gokalp A. Solitary calcaneal metastasis in superficial bladder carcinoma. Int J Clin Pract 54: 681–682, 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt et al. 2007.Schmidt BL, Pickering V, Liu S, Quang P, Dolan J, Connelly ST, Jordan RC. Peripheral endothelin A receptor antagonism attenuates carcinoma-induced pain. Eur J Pain 11: 406–414, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwei et al. 1999.Schwei MJ, Honore P, Rogers SD, Salak-Johnson JL, Finke MP, Ramnaraine ML, Clohisy DR, Mantyh PW. Neurochemical and cellular reorganization of the spinal cord in a murine model of bone cancer pain. J Neurosci 19: 10886–10897, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevcik 2005a.Sevcik MA, Ghilardi JR, Halvorson KG, Lindsay TH, Kubota K, Mantyh PW. Analgesic efficacy of bradykinin B1 antagonists in a murine bone cancer pain model. J Pain 6: 771–775, 2005a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevcik 2005b.Sevcik MA, Ghilardi JR, Peters CM, Lindsay TH, Halvorson KG, Jonas BM, Kubota K, Kuskowski MA, Boustany L, Shelton DL, Mantyh PW. Anti-NGF therapy profoundly reduces bone cancer pain and the accompanying increase in markers of peripheral and central sensitization. Pain 115: 128–141, 2005b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shichiri et al. 1991.Shichiri M, Hirata Y, Nakajima T, Ando K, Imai T, Yanagisawa M, Masaki T, Marumo F. Endothelin-1 is an autocrine/paracrine growth factor for human cancer cell lines. J Clin Invest 87: 1867–1871, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorkin et al. 1997.Sorkin LS, Xiao WH, Wagner R, Myers RR. Tumor necrosis factor-α induces ectopic activity in nociceptive primary afferent fibers. Neuroscience 81: 255–262, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga et al. 1998.Tominaga M, Caterina MJ, Malmberg AB, Rosen TA, Gilbert H, Skinner K, Raumann BE, Basbaum AI, Julius D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron 21: 531–543, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentin et al. 2006.Trentin PG, Fernandes MB, D'Orleans-Juste P, Rae GA. Endothelin-1 causes pruritus in mice. Exp Biol Med 231: 1146–1151, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vane 1990.Vane J Endothelins come home to roost. Nature 348: 673, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verhaar et al. 2000.Verhaar MC, Grahn AY, Van Weerdt AW, Honing ML, Morrison PJ, Yang YP, Padley RJ, Rabelink TJ. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamic effects of ABT-627, an oral ETA selective endothelin antagonist, in humans. Br J Clin Pharmacol 49: 562–573, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verri et al. 2005.Verri WA Jr, Molina RO, Schivo IR, Cunha TM, Parada CA, Poole S, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ. Nociceptive effect of subcutaneously injected interleukin-12 is mediated by endothelin (ET) acting on ETB receptors in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 315: 609–615, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verri et al. 2004.Verri WA Jr, Schivo IR, Cunha TM, Liew FY, Ferreira SH, Cunha FQ. Interleukin-18 induces mechanical hypernociception in rats via endothelin acting on ETB receptors in a morphine-sensitive manner. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 310: 710–717, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacnik et al. 2001.Wacnik PW, Eikmeier LJ, Ruggles TR, Ramnaraine ML, Walcheck BK, Beitz AJ, Wilcox GL. Functional interactions between tumor and peripheral nerve: morphology, algogen identification, and behavioral characterization of a new murine model of cancer pain. J Neurosci 21: 9355–9366, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacnik et al. 2003.Wacnik PW, Kehl LJ, Trempe TM, Ramnaraine ML, Beitz AJ, Wilcox GL. Tumor implantation in mouse humerus evokes movement-related hyperalgesia exceeding that evoked by intramuscular carrageenan. Pain 101: 175–186, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto et al. 2006.Yamamoto H, Kawamata T, Ninomiya T, Omote K, Namiki A. Endothelin-1 enhances capsaicin-evoked intracellular Ca2+ response via activation of endothelin a receptor in a protein kinase Cepsilon-dependent manner in dorsal root ganglion neurons. Neuroscience 137: 949–960, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanagisawa et al. 1988.Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. A novel peptide vasoconstrictor, endothelin, is produced by vascular endothelium and modulates smooth muscle Ca2+ channels. J Hypertens Suppl 6: S188–191, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yohn et al. 1993.Yohn JJ, Morelli JG, Walchak SJ, Rundell KB, Norris DA, Zamora MR. Cultured human keratinocytes synthesize and secrete endothelin-1. J Invest Dermatol 100: 23–26, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuyama 2004a.Yuyama H, Koakutsu A, Fujiyasu N, Fujimori A, Sato S, Shibasaki K, Tanaka S, Sudoh K, Sasamata M, Miyata K. Inhibitory effects of a selective endothelin-A receptor antagonist YM598 on endothelin-1-induced potentiation of nociception in formalin-induced and prostate cancer-induced pain models in mice. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 44 Suppl 1: S479–482, 2004a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuyama 2004b.Yuyama H, Koakutsu A, Fujiyasu N, Tanahashi M, Fujimori A, Sato S, Shibasaki K, Tanaka S, Sudoh K, Sasamata M, Miyata K. Effects of selective endothelin ET(A) receptor antagonists on endothelin-1-induced potentiation of cancer pain. Eur J Pharmacol 492: 177–182, 2004b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. 2001.Zhou QL, Strichartz G, Davar G. Endothelin-1 activates ET(A) receptors to increase intracellular calcium in model sensory neurons. Neuroreport 12: 3853–3857, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou et al. 2002.Zhou Z, Davar G, Strichartz G. Endothelin-1 (ET-1) selectively enhances the activation gating of slowly inactivating tetrodotoxin-resistant sodium currents in rat sensory neurons: a mechanism for the pain-inducing actions of ET-1. J Neurosci 22: 6325–6330, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann 1983.Zimmermann M Ethical guidelines for investigations of experimental pain in conscious animals. Pain 16: 109–110, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]