Abstract

Insomnia is the most prevalent sleep disorder in the general population, and is commonly encountered in medical practices. Insomnia is defined as the subjective perception of difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep, and that results in some form of daytime impairment.1 Insomnia may present with a variety of specific complaints and etiologies, making the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia demanding on a clinician's time. The purpose of this clinical guideline is to provide clinicians with a practical framework for the assessment and disease management of chronic adult insomnia, using existing evidence-based insomnia practice parameters where available, and consensus-based recommendations to bridge areas where such parameters do not exist. Unless otherwise stated, “insomnia” refers to chronic insomnia, which is present for at least a month, as opposed to acute or transient insomnia, which may last days to weeks.

Citation:

Schutte-Rodin S; Broch L; Buysse D; Dorsey C; Sateia M. Clinical guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults. J Clin Sleep Med 2008;4(5):487–504.

SUMMARY RECOMMENDATIONS

General:

Insomnia is an important public health problem that requires accurate diagnosis and effective treatment. (Standard)

An insomnia diagnosis requires associated daytime dysfunction in addition to appropriate insomnia symptomatology. (ICSD-2 definition)

Evaluation:

- Insomnia is primarily diagnosed by clinical evaluation through a thorough sleep history and detailed medical, substance, and psychiatric history. (Standard)

- The sleep history should cover specific insomnia complaints, pre-sleep conditions, sleep-wake patterns, other sleep-related symptoms, and daytime consequences. (Consensus)

- The history helps to establish the type and evolution of insomnia, perpetuating factors, and identification of comorbid medical, substance, and/or psychiatric conditions. (Consensus)

- Instruments which are helpful in the evaluation and differential diagnosis of insomnia include self-administered questionnaires, at-home sleep logs, symptom checklists, psychological screening tests, and bed partner interviews. (Guideline)

- At minimum, the patient should complete: (1) A general medical/psychiatric questionnaire to identify comorbid disorders (2) The Epworth Sleepiness Scale or other sleepiness assessment to identify sleepy patients and comorbid disorders of sleepiness (3) A two-week sleep log to identify general patterns of sleep-wake times and day-to-day variability. (Consensus)

- Sleep diary data should be collected prior to and during the course of active treatment and in the case of relapse or reevaluation in the long-term. (Consensus)

- Additional assessment instruments that may aid in the baseline evaluation and outcomes follow-up of patients with chronic insomnia include measures of subjective sleep quality, psychological assessment scales, daytime function, quality of life, and dysfunctional beliefs and attitudes. (Consensus)

Physical and mental status examination may provide important information regarding comorbid conditions and differential diagnosis. (Standard)

- Polysomnography and daytime multiple sleep latency testing (MSLT) are not indicated in the routine evaluation of chronic insomnia, including insomnia due to psychiatric or neuropsychiatric disorders. (Standard)

- Polysomnography is indicated when there is reasonable clinical suspicion of breathing (sleep apnea) or movement disorders, when initial diagnosis is uncertain, treatment fails (behavioral or pharmacologic), or precipitous arousals occur with violent or injurious behavior. (Guideline)

Actigraphy is indicated as a method to characterize circadian rhythm patterns or sleep disturbances in individuals with insomnia, including insomnia associated with depression. (Option)

Other laboratory testing (e.g., blood, radiographic) is not indicated for the routine evaluation of chronic insomnia unless there is suspicion for comorbid disorders. (Consensus)

Differential Diagnosis:

The presence of one insomnia disorder does not exclude other disorders, as multiple primary and comorbid insomnia disorders may coexist. (Consensus)

Treatment Goals/Treatment Outcomes:

Regardless of the therapy type, primary treatment goals are: (1) to improve sleep quality and quantity and (2) to improve insomnia related daytime impairments. (Consensus)

Other specific outcome indicators for sleep generally include measures of wake time after sleep onset (WASO), sleep onset latency (SOL), number of awakenings, sleep time or sleep efficiency, formation of a positive and clear association between the bed and sleeping, and improvement of sleep related psychological distress. (Consensus)

Sleep diary data should be collected prior to and during the course of active treatment and in the case of relapse or reevaluation in the long term (every 6 months). (Consensus)

In addition to clinical reassessment, repeated administration of questionnaires and survey instruments may be useful in assessing outcome and guiding further treatment efforts. (Consensus)

Ideally, regardless of the therapy type, clinical reassessment should occur every few weeks and/or monthly until the insomnia appears stable or resolved, and then every 6 months, as the relapse rate for insomnia is high. (Consensus)

When a single treatment or combination of treatments has been ineffective, other behavioral therapies, pharmacological therapies, combined therapies, or reevaluation for occult comorbid disorders should be considered. (Consensus)

Psychological and Behavioral Therapies:

- Psychological and behavioral interventions are effective and recommended in the treatment of chronic primary and comorbid (secondary) insomnia. (Standard)

- These treatments are effective for adults of all ages, including older adults, and chronic hypnotic users. (Standard)

- These treatments should be utilized as an initial intervention when appropriate and when conditions permit. (Consensus)

Initial approaches to treatment should include at least one behavioral intervention such as stimulus control therapy or relaxation therapy, or the combination of cognitive therapy, stimulus control therapy, sleep restriction therapy with or without relaxation therapy—otherwise known as cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I). (Standard)

Multicomponent therapy (without cognitive therapy) is effective and recommended therapy in the treatment of chronic insomnia. (Guideline)

Other common therapies include sleep restriction, paradoxical intention, and biofeedback therapy. (Guideline)

Although all patients with chronic insomnia should adhere to rules of good sleep hygiene, there is insufficient evidence to indicate that sleep hygiene alone is effective in the treatment of chronic insomnia. It should be used in combination with other therapies. (Consensus)

When an initial psychological/ behavioral treatment has been ineffective, other psychological/ behavioral therapies, combination CBT-I therapies, combined treatments (see below), or occult comorbid disorders may next be considered. (Consensus)

Pharmacological Treatment:

Short-term hypnotic treatment should be supplemented with behavioral and cognitive therapies when possible. (Consensus)

When pharmacotherapy is utilized, the choice of a specific pharmacological agent within a class, should be directed by: (1) symptom pattern; (2) treatment goals; (3) past treatment responses; (4) patient preference; (5) cost; (6) availability of other treatments; (7) comorbid conditions; (8) contraindications; (9) concurrent medication interactions; and (10) side effects. (Consensus)

- For patients with primary insomnia (psychophysiologic, idiopathic or paradoxical ICSD-2 subtypes), when pharmacologic treatment is utilized alone or in combination therapy, the recommended general sequence of medication trials is: (Consensus)

- Short-intermediate acting benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BZD or newer BzRAs) or ramelteon: examples of these medications include zolpidem, eszopiclone, zaleplon, and temazepam

- Alternate short-intermediate acting BzRAs or ramelteon if the initial agent has been unsuccessful

- Sedating antidepressants, especially when used in conjunction with treating comorbid depression/anxiety: examples of these include trazodone, amitriptyline, doxepin, and mirtazapine

- Combined BzRA or ramelteon and sedating antidepressant

- Other sedating agents: examples include anti-epilepsy medications (gabapentin, tiagabine) and atypical antipsychotics (quetiapine and olanzapine)

- These medications may only be suitable for patients with comorbid insomnia who may benefit from the primary action of these drugs as well as from the sedating effect.

Over-the-counter antihistamine or antihistamine/analgesic type drugs (OTC “sleep aids”) as well as herbal and nutritional substances (e.g., valerian and melatonin) are not recommended in the treatment of chronic insomnia due to the relative lack of efficacy and safety data. (Consensus)

Older approved drugs for insomnia including barbiturates, barbiturate-type drugs and chloral hydrate are not recommended for the treatment of insomnia. (Consensus)

- The following guidelines apply to prescription of all medications for management of chronic insomnia: (Consensus)

- Pharmacological treatment should be accompanied by patient education regarding: (1) treatment goals and expectations; (2) safety concerns; (3) potential side effects and drug interactions; (4) other treatment modalities (cognitive and behavioral treatments); (5) potential for dosage escalation; (6) rebound insomnia.

- Patients should be followed on a regular basis, every few weeks in the initial period of treatment when possible, to assess for effectiveness, possible side effects, and the need for ongoing medication.

- Efforts should be made to employ the lowest effective maintenance dosage of medication and to taper medication when conditions allow.

- Medication tapering and discontinuation are facilitated by CBT-I.

- Chronic hypnotic medication may be indicated for long-term use in those with severe or refractory insomnia or chronic comorbid illness. Whenever possible, patients should receive an adequate trial of cognitive behavioral treatment during long-term pharmacotherapy.

- Long-term prescribing should be accompanied by consistent follow-up, ongoing assessment of effectiveness, monitoring for adverse effects, and evaluation for new onset or exacerbation of existing comorbid disorders

- Long-term administration may be nightly, intermittent (e.g., three nights per week), or as needed.

Combined Treatments:

The use of combined therapy (CBT-I plus medication) should be directed by (1) symptom pattern; (2) treatment goals; (3) past treatment responses; (4) patient preference; (5) cost; (6) availability of other treatments; (7) comorbid conditions; (8) contraindications; (9) concurrent medication interactions; and (10) side effects. (Consensus)

Combined therapy shows no consistent advantage or disadvantage over CBT-I alone. Comparisons to long-term pharmacotherapy alone are not available. (Consensus)

INTRODUCTION

Insomnia symptoms occur in approximately 33% to 50% of the adult population; insomnia symptoms with distress or impairment (general insomnia disorder) in 10% to 15%. Consistent risk factors for insomnia include increasing age, female sex, comorbid (medical, psychiatric, sleep, and substance use) disorders, shift work, and possibly unemployment and lower socioeconomic status. “Insomnia” has been used in different contexts to refer to either a symptom or a specific disorder. In this guideline, an insomnia disorder is defined as a subjective report of difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep, and that results in some form of daytime impairment. Because insomnia may present with a variety of specific complaints and contributing factors, the time required for evaluation and management of chronic insomnia can be demanding for clinicians. The purpose of this clinical guideline is to provide clinicians with a framework for the assessment and management of chronic adult insomnia, using existing evidence-based insomnia practice parameters where available, and consensus-based recommendations to bridge areas where such parameters do not exist.

METHODS

This clinical guideline includes both evidence-based and consensus-based recommendations. In the guideline summary recommendation section, each recommendation is accompanied by its level of evidence: standard, guideline, option, or consensus based. “Standard,” “guideline,” and “option” recommendations were incorporated from evidence-based American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) practice parameter papers. “Consensus” recommendations were developed using a modified nominal group technique. The development of these recommendations and their appropriate use are described below.

Evidence-Based Practice Parameters

In the development of this guideline, existing AASM practice parameter papers relevant to the evaluation and management of chronic insomnia in adults were incorporated.2–6 These practice parameter papers, many of which addressed specific insomnia-related topics rather than providing a comprehensive clinical chronic insomnia practice guideline for clinicians, were previously developed via a computerized, systematic search of the scientific literature (for specific search terms and further details, see referenced practice parameter) and subsequent critical review, evaluation, and evidence-grading of all pertinent studies.7

On the basis of this review the AASM Standards of Practice Committee developed practice parameters. Practice parameters were designated as “Standard,” “Guideline,” or “Option” based on the quality and amount of scientific evidence available (Table 1).

Table 1.

AASM Levels of Recommendations

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Standard | This is a generally accepted patient-care strategy that reflects a high degree of clinical certainty. The term standard generally implies the use of Level 1 Evidence, which directly addresses the clinical issue, or overwhelming Level 2 Evidence. |

| Guideline | This is a patient-care strategy that reflects a moderate degree of clinical certainty. The term guideline implies the use of Level 2 Evidence or a consensus of Level 3 Evidence. |

| Option | This is a patient-care strategy that reflects uncertain clinical use. The term option implies insufficient, inconclusive, or conflicting evidence or conflicting expert opinion. |

Consensus-Based Recommendations

Consensus-based recommendations were developed for this clinical guideline to address important areas of clinical practice that had not been the subject of a previous AASM practice parameter, or where the available empirical data was limited or inconclusive. Consensus-based recommendations reflect the shared judgment of the committee members and reviewers, based on the literature and common clinical practice of topic experts, and were developed using a modified nominal group technique. An expert insomnia panel was assembled by the AASM to author this clinical guideline. In addition to using all AASM practice parameters and AASM Sleep publications through July 2007, the expert panel reviewed other relevant source articles from a Medline search (1999 to October 2006; all adult ages including seniors; “insomnia and” key words relating to evaluation, testing, and treatments. Using a face-to-face meeting, voting surveys, and frequent teleconference discussions, the expert panel identified consensus areas and recommendations for those areas not covered by AASM practice parameters. Recommendations were generated by panel members and discussed by all. To minimize individual expert bias, the group anonymously voted and rated consensus recommendations from 1: strongly disagree to 9: strongly agree. Consensus was defined when all experts rated a recommendation 8 or 9. If consensus was not evident after the first vote, the consensus recommendations were discussed again, amended as appropriate, and a second anonymous vote was conducted. If consensus was not evident after the second vote, the process was repeated until consensus was attained to include or exclude a recommendation.

Use of Practice Parameters and Clinical Guidelines

AASM practice parameter papers are based on evidence-based review and grading of literature, often addressing a specific issue or topic. Clinical guidelines provide clinicians with a working overview for disease or disorder evaluation and management. These guidelines include practice parameter papersx and also include areas with limited evidence in order to provide a comprehensive practice guideline. Both practice parameters and clinical guidelines define principles of practice that should meet the needs of most patients. They should not, however, be considered exhaustive, inclusive of all available methods of care, or exclusive of other methods of care reasonably expected to obtain the same results. The ultimate judgment regarding appropriateness of any specific therapy must be made by the clinician and patient in light of the individual circumstances presented by the patient, available diagnostic tools, accessible treatment options, resources available, and other relevant factors. The AASM expects this clinical guideline to have an impact on professional behavior and patient outcomes. It reflects the state of knowledge at the time of publication and will be reviewed, updated, and revised as new information becomes available.

INSOMNIA DEFINITIONS AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

Insomnia Definitions

“Insomnia” has been used in different contexts to refer to either a symptom or a specific disorder. In this guideline, an insomnia disorder is defined as a subjective report of difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality that occurs despite adequate opportunity for sleep, and that result in some form of daytime impairment (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic Criteria for Insomnia (ICSD-2)

|

Except where otherwise noted, the word “insomnia” refers to an insomnia disorder in this guideline.

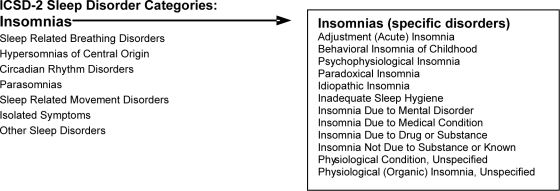

Insomnia disorders have been categorized in various ways in different sleep disorder classification systems. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders, 2nd Edition (ICSD-2) is used as the basis for insomnia classification in this guideline. The ICSD-2 identifies insomnia as one of eight major categories of sleep disorders and, within this group, lists twelve specific insomnia disorders (Table 3).

Table 3.

ICSD-2 Insomnia Diagnoses

ICSD-2 delineates both general diagnostic criteria that apply to all insomnia disorders, as well as more specific criteria for each diagnosis. Insomnia complaints may also occur in association with comorbid disorders or other sleep disorder categories, such as sleep related breathing disorders, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, and sleep related movement disorders.

Epidemiology

Insomnia occurs in individuals of all ages and races, and has been observed across all cultures and countries.8,9 The actual prevalence of insomnia varies according to the stringency of the definition used. Insomnia symptoms occur in approximately 33% to 50% of the adult population; insomnia symptoms with distress or impairment (i.e., general insomnia disorder) in 10% to 15%; and specific insomnia disorders in 5% to 10%.10 Consistent risk factors for insomnia include increasing age, female sex, comorbid (medical, psychiatric, sleep, and substance use) disorders, shift work, and possibly unemployment and lower socioeconomic status. Patients with comorbid medical and psychiatric conditions are at particularly increased risk, with psychiatric and chronic pain disorders having insomnia rates as high as 50% to 75%.11–13 The risk relationship between insomnia and psychiatric disorders appears to be bidirectional; several studies have also demonstrated an increased risk of psychiatric disorders among individuals with prior insomnia.13 The course of insomnia is often chronic, with studies showing persistence in 50% to 85% of individuals over follow-up intervals of one to several years.14

DIAGNOSIS OF CHRONIC INSOMNIA

Evaluation

The evaluation of chronic insomnia is enhanced by understanding models for the evolution of chronic insomnia.15–18 Numerous models may be reasonable from neurobiological, neurophysiological, cognitive, behavioral (and other) perspectives. Although details of current models are beyond the scope of this practice guideline, general model concepts are critical for identifying biopsychosocial predisposing factors (such as hyperarousal, increased sleep-reactivity, or increased stress response), precipitating factors, and perpetuating factors such as (1) conditioned physical and mental arousal and (2) learned negative sleep behaviors and cognitive distortions. In particular, identification of perpetuating negative behaviors and cognitive processes often provides the clinician with invaluable information for diagnosis as well as for treatment strategies. In contrast to evolving models and diagnostic classifications for insomnia, procedures for clinical evaluation have remained relatively stable over time. Evaluation continues to rest on a careful patient history and examination that addresses sleep and waking function (Table 4), as well as common medical, psychiatric, and medication/substance-related comorbidities (Tables 5, 6, and 7). The insomnia history includes evaluation of:

The Primary Complaint: Patients with insomnia may complain of difficulty falling asleep, frequent awakenings, difficulty returning to sleep, awakening too early in the morning, or sleep that does not feel restful, refreshing, or restorative. Although patients may complain of only one type of symptom, it is common for multiple types of symptoms to co-occur, and for the specific presentation to vary over time. Key components include characterization of the complaint type, duration (months, years, lifetime), frequency (nights per week or number of times per night), severity of nighttime distress and associated daytime symptomatology, course (progressive, intermittent, relentless), factors which increase or decrease symptoms, and identification of past and current precipitants, perpetuating factors, treatments, and responses.

Pre-Sleep Conditions: Patients with insomnia may develop behaviors that have the unintended consequence of perpetuating their sleep problem. These behaviors may begin as strategies to combat the sleep problem, such as spending more time in bed in an effort to “catch up” on sleep. Other behaviors in bed or in the bedroom that are incompatible with sleep may include talking on the telephone, watching television, computer use, exercising, eating, smoking, or “clock watching.” Insomnia patients may report sensations of being more aware of the environment than are other individuals and may report anticipating a poor sleep hours before bedtime, and become more alert and anxious as bedtime approaches. Characterization of the sleeping environment (couch/bed, light/dark, quiet/noisy, room temperature, alone/bed partner, TV on/off) as well as the patient's state of mind (sleepy vs. wide awake, relaxed vs. anxious) is helpful in understanding which factors might facilitate or prolong sleep onset or awakenings after sleep.

Sleep-Wake Schedule: In evaluating sleep-related symptoms, the clinician must consider not only the patient's “usual” symptoms, but also their range, day-to-day variability, and evolution over time. Specific sleep-wake variables such as time to fall asleep (sleep latency), number of awakenings, wake time after sleep onset (WASO), sleep duration, and napping can be quantified retrospectively during the clinical assessment and prospectively with sleep-wake logs. Although no specific quantitative sleep parameters define insomnia disorder, common complaints for insomnia patients are an average sleep latency >30 minutes, wake after sleep onset >30 minutes, sleep efficiency <85%, and/or total sleep time <6.5 hours.19,20 Day-to-day variability should be considered, as well as variability during longer periodicities such as those that may occur with the menstrual cycle or seasons. Patterns of sleep at unusual times may assist in identifying Circadian Rhythm Disorders such as Advanced Sleep Phase Type or Delayed Sleep Phase Type. Assessing whether the final awakening occurs spontaneously or with an alarm adds insight into the patient's sleep needs and natural sleep and wake rhythm. Finally, the clinician must ascertain whether the individual's sleep and daytime complaints occur despite adequate time available for sleep, in order to distinguish insomnia from behaviorally induced insufficient sleep.

Nocturnal Symptoms: Patient and bed partner reports may also help to identify nocturnal signs, symptoms and behaviors associated with breathing-related sleep disorders (snoring, gasping, coughing), sleep related movement disorders (kicking, restlessness), parasomnias (behaviors or vocalization), and comorbid medical/neurological disorders (reflux, palpitations, seizures, headaches). Other physical sensations and emotions associated with wakefulness (such as pain, restlessness, anxiety, frustration, sadness) may contribute to insomnia and should also be evaluated.

- Daytime Activities and Daytime Function: Daytime activities and behaviors may provide clues to potential causes and consequences of insomnia. Napping (frequency/day, times, voluntary/involuntary), work (work times, work type such as driving or with dangerous consequences, disabled, caretaker responsibilities), lifestyle (sedentary/active, homebound, light exposure, exercise), travel (especially across time zones), daytime dysfunction (quality of life, mood, cognitive dysfunction), and exacerbation of comorbid disorders should be evaluated in depth. Common daytime consequences include:

- Fatigue and sleepiness. Feelings of fatigue (low energy, physical tiredness, weariness) are more common than symptoms of sleepiness (actual tendency to fall asleep) in patients with chronic insomnia. The presence of significant sleepiness should prompt a search for other potential sleep disorders. The number, duration, and timing of naps should be thoroughly investigated, as both a consequence of insomnia and a potential contributing factor.

- Mood disturbances and cognitive difficulties. Complaints of irritability, loss of interest, mild depression and anxiety are common among insomnia patients. Patients with chronic insomnia often complain of mental inefficiency, difficulty remembering, difficulty focusing attention, and difficulty with complex mental tasks.

- Quality of life: The irritability and fatigue associated with insomnia may cause interpersonal difficulties for insomnia patients, or avoidance of such activities. Conversely, interpersonal difficulties may be an important contributor to insomnia problems for some individuals. Sleep and waking problems may lead to restriction of daytime activities, including social events, exercise, or work. Lack of regular daytime activities and exercise may in turn contribute to insomnia.

- Exacerbation of comorbid conditions. Comorbid conditions may cause or increase sleep difficulties. Likewise, poor sleep may exacerbate symptomatology of comorbid conditions. Sleep complaints may herald the onset of mood disorders or exacerbation of comorbid conditions.

Other History: A complete insomnia history also includes medical, psychiatric, medication/substance, and family/social/occupational histories. A wide range of medical (Table 5) and psychiatric (Table 6) conditions can be comorbid with insomnia. Likewise, the direct effects of over-the-counter and prescription medications and substances (Table 7), and their effects upon withdrawal, may impact both sleep and daytime symptoms. Conditions often comorbid with insomnia, such as mood and anxiety disorders, may also have familial or genetic components. Social and occupational histories may indicate not only the effects of insomnia on the individual, but also possible contributing factors. Occupational assessment should specifically include work around dangerous machinery, driving duties, regular or irregular shift-work and transmeridian travel.

Table 4.

Sleep History

|

Table 5.

Common Comorbid Medical Disorders, Conditions, and Symptoms

| System | Examples of disorders, conditions, and symptoms |

|---|---|

| Neurological | Stroke, dementia, Parkinson disease, seizure disorders, headache disorders, traumatic brain injury, peripheral neuropathy, chronic pain disorders, neuromuscular disorders |

| Cardiovascular | Angina, congestive heart failure, dyspnea, dysrhythmias |

| Pulmonary | COPD, emphysema, asthma, laryngospasm |

| Digestive | Reflux, peptic ulcer disease, cholelithiasis, colitis, irritable bowel syndrome |

| Genitourinary | Incontinence, benign prostatic hypertrophy, nocturia, enuresis, interstitial cystitis |

| Endocrine | Hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, diabetes mellitus |

| Musculoskeletal | Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, fibromyalgia, Sjögren syndrome, kyphosis |

| Reproductive | Pregnancy, menopause, menstrual cycle variations |

| Sleep disorders | Obstructive sleep apnea, central sleep apnea, restless legs syndrome, periodic limb movement disorder, circadian rhythm sleep disorders, parasomnias |

| Other | Allergies, rhinitis, sinusitis, bruxism, alcohol and other substance use/dependence/withdrawal |

Table 6.

Common Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders and Symptoms

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Mood disorders | Major depressive disorder, bipolar mood disorder, dysthymia |

| Anxiety disorders | Generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder |

| Psychotic disorders | Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder |

| Amnestic disorders | Alzheimer disease, other dementias |

| Disorders usually seen in childhood and adolescence | Attention deficit disorder |

| Other disorders and symptoms | Adjustment disorders, personality disorders, bereavement, stress |

Table 7.

Common Contributing Medications and Substances

| Category | Examples |

|---|---|

| Antidepressants | SSRIs (fluoxetine, paroxetine, sertraline, citalopram, escitalopram, fluvoxamine), venlafaxine, duloxetine, monoamine oxidase inhibitors |

| Stimulants | Caffeine, methylphenidate, amphetamine derivatives, ephedrine and derivatives, cocaine |

| Decongestants | Pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine, phenylpropanolamine |

| Narcotic analgesics | Oxycodone, codeine, propoxyphene |

| Cardiovascular | β-Blockers, α-receptor agonists and antagonists, diuretics, lipid-lowering agents |

| Pulmonary Alcohol | Theophylline, albuterol |

Physical and Mental Status Examination: Chronic insomnia is not associated with any specific features on physical or mental status examination. However, these exams may provide important information regarding comorbid conditions and differential diagnosis. A physical exam should specifically evaluate risk factors for sleep apnea (obesity, increased neck circumference, upper airway restrictions) and comorbid medical conditions that include but are not limited to disorders of pulmonary, cardiac, rheumatologic, neurological, endocrine (such as thyroid), and gastrointestinal systems. The mental status exam should focus on mood, anxiety, memory, concentration, and degree of alertness or sleepiness.

Supporting Information: While a thorough clinical history and exam form the core of the evaluation, differential diagnosis is further aided by the use of sleep logs, questionnaires for sleep quality, sleepiness, psychological assessment and quality of life (Table 8), and in some cases, actigraphy.21–23 For specific insomnias, psychological testing, quality of life questionnaires, and other comorbid questionnaires and testing are useful. The choice of assessment tools should be based on the patient's presentation and the clinician's expertise. At minimum, the patient should complete:

A general medical/psychiatric/medication questionnaire (to identify comorbid disorders and medication use)

The Epworth Sleepiness Scale or other sleepiness assessment (to identify sleepy patients)24

A two-week sleep log to identify sleep-wake times, general patterns, and day-to-day variability.

Table 8.

Examples of Insomnia Questionnaires Used in Baseline and Treatment Outcome Assessment

| Questionnaire | Description |

|---|---|

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale | ESS is an 8-item self report questionnaire used to assess subjective sleepiness (score range: 0–24; normal <10). |

| Insomnia Severity Index | ISI is a 7-item rating used to assess the patient's perception of insomnia. |

| Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index | PSQI is a 24-item self report measure of sleep quality (poor sleep: global score >5). |

| Beck Depression Inventory | BDI (or BDI-II) is a 21-item self report inventory used to measure depression (minimal or no depression: BDI <10; moderate to severe: BDI >18). |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory-Form Y Trait Scale | STAI is a 20-item self report inventory used to measure anxiety (score range: 20–80; minimum anxiety: T-score <50; significant anxiety: T score >70). |

| Fatigue Severity Scale | FSS is a 9-item patient rating of daytime fatigue. |

| Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) | SF-36 is a 36-item self report inventory that generically measures quality of life for any disorder (range from 0 (poorest) to 100 (well-being). |

| Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes about Sleep Questionnaire | DBAS is a self-rating of 28 statements that is used to assess negative cognitions about sleep. |

When possible, questionnaires and a two-week sleep log should be completed prior to the first visit to begin the process of the patient viewing global sleep patterns, in contrast with one specific night, and to enlist the patient in taking an active role in treatment. Primary baseline measures obtained from a sleep log include:

Bedtime

Sleep latency (SL: time to fall asleep following bedtime)

Number of awakenings and duration of each awakening

Wake after sleep onset (WASO: the sum of wake times from sleep onset to the final awakening)

Time in bed (TIB: time from bedtime to getting out of bed)

Total sleep time (TST: time in bed minus SL and minus WASO)

Sleep efficiency percent (SE equals TST divided by TIB times 100)

Nap times (frequency, times, durations)

Sleep logs may also include reports of sleep quality, daytime impairment, medications, caffeine, and alcohol consumption for each 24-hour period.

Objective Assessment Tools: Laboratory testing, polysomnography and actigraphy are not routinely indicated in the evaluation of insomnia, but may be appropriate in individuals who present with specific symptoms or signs of comorbid medical or sleep disorders.

Differential Diagnosis

The insomnia and insomnia-related disorders listed in ICSD-2 can be considered conceptually in three major groupings:

Insomnia associated with other sleep disorders most commonly includes sleep related breathing disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea), movement disorders (e.g., restless legs or periodic limb movements during sleep) or circadian rhythm sleep disorders;

Insomnia due to medical or psychiatric disorders or to drug/substance (comorbid insomnia); and

Primary insomnias including psychophysiological, idiopathic, and paradoxical insomnias.

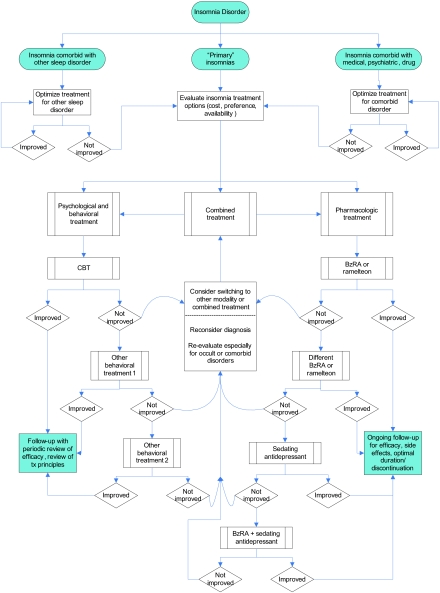

Table 9 describes the key features of ICSD-2 insomnia disorders. Figure 1 presents a diagnostic algorithm for chronic insomnia based on the features described in Table 9. It should be noted that comorbid insomnias and multiple insomnia diagnoses may coexist and require separate identification and treatment.

Table 9.

ICSD-2 Insomnias

| Disorder | Description |

|---|---|

| Adjustment (Acute) Insomnia | The essential feature of this disorder is the presence of insomnia in association with an identifiable stressor, such as psychosocial, physical, or environmental disturbances. The sleep disturbance has a relatively short duration (days-weeks) and is expected to resolve when the stressor resolves. |

| Psychophysiological Insomnia | The essential features of this disorder are heightened arousal and learned sleep-preventing associations. Arousal may be physiological, cognitive, or emotional, and characterized by muscle tension, “racing thoughts,” or heightened awareness of the environment. Individuals typically have increased concern about sleep difficulties and their consequences, leading to a “vicious cycle” of arousal, poor sleep, and frustration. |

| Paradoxical Insomnia | The essential feature of this disorder is a complaint of severe or nearly “total” insomnia that greatly exceeds objective evidence of sleep disturbance and is not commensurate with the reported degree of daytime deficit. Although paradoxical insomnia is best diagnosed with concurrent PSG and self-reports, it can be presumptively diagnosed on clinical grounds alone. To some extent, “misperception” of the severity of sleep disturbance may characterize all insomnia disorders. |

| Idiopathic Insomnia | The essential feature of this disorder is a persistent complaint of insomnia with insidious onset during infancy or early childhood and no or few extended periods of sustained remission. Idiopathic insomnia is not associated with specific precipitating or perpetuating factors. |

| Insomnia Due to Mental Disorder | The essential feature of this disorder is the occurrence of insomnia that occurs exclusively during the course of a mental disorder, and is judged to be caused by that disorder. The insomnia is of sufficient severity to cause distress or to require separate treatment. This diagnosis is not used to explain insomnia that has a course independent of the associated mental disorder, as is not routinely made in individuals with the “usual” severity of sleep symptoms for an associated mental disorder. |

| Inadequate Sleep Hygiene | The essential feature of this disorder is insomnia associated with voluntary sleep practices or activities that are inconsistent with good sleep quality and daytime alertness. These practices and activities typically produce increased arousal or directly interfere with sleep, and may include irregular sleep scheduling, use of alcohol, caffeine, or nicotine, or engaging in non-sleep behaviors in the sleep environment. Some element of poor sleep hygiene may characterize individuals with other insomnia disorders. |

| Insomnia Due to a Drug or Substance | The essential feature of this disorder is sleep disruption due to use of a prescription medication, recreational drug, caffeine, alcohol, food, or environmental toxin. Insomnia may occur during periods of use/exposure, or during discontinuation. When the identified substance is stopped, and after discontinuation effects subside, the insomnia is expected to resolve or substantially improve. |

| Insomnia Due to Medical Condition | The essential feature of this disorder is insomnia caused by a coexisting medical disorder or other physiological factor. Although insomnia is commonly associated with many medical conditions, this diagnosis should be used when the insomnia causes marked distress or warrants separate clinical attention. This diagnosis is not used to explain insomnia that has a course independent of the associated medical disorder, and is not routinely made in individuals with the “usual” severity of sleep symptoms for an associated medical disorder. |

| Insomnia Not Due to Substance or Known Physiologic Condition, Unspecified; Physiologic (Organic) Insomnia, Unspecified | These two diagnoses are used for insomnia disorders that cannot be classified elsewhere but are suspected to be related to underlying mental disorders, psychological factors, behaviors, medical disorders, physiological states, or substance use or exposure. These diagnoses are typically used when further evaluation is required to identify specific associated conditions, or when the patient fails to meet criteria for a more specific disorder. |

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the Evaluation of Chronic Insomnia. When using this diagram, the clinician should be aware that the presence of one diagnosis does not exclude other diagnoses in the same or another tier, as multiple diagnoses may coexist. Acute Adjustment Insomnia, not a chronic insomnia, is included in the chronic insomnia algorithm in order to highlight that the clinician should be aware that extrinsic stressors may trigger, perpetuate, or exacerbate the chronic insomnia.

TREATMENT OF CHRONIC INSOMNIA

Indications for Treatment

Treatment is recommended when the chronic insomnia has a significant negative impact on the patient's sleep quality, health, comorbid conditions, or daytime function. It is essential to recognize and treat comorbid conditions that commonly occur with insomnia, and to identify and modify behaviors and medications or substances that impair sleep.

Risk Counseling

Public Health Burden and Public Safety:Insomnia causes both individual and societal burdens. By definition, patients with chronic insomnia have daytime impairment of cognition, mood, or performance that impacts on the patient and potentially on family, friends, coworkers and caretakers. Chronic insomnia patients are more likely to use health care resources, visit physicians, be absent or late for work, make errors or have accidents at work, and have more serious road accidents.25,26 Increased risk for suicide, substance use relapse, and possible immune dysfunction have been reported.27 Comorbid conditions, particularly depression, anxiety, and substance use, are common. There is a bidirectional increased risk between insomnia and depression. Other medical conditions, unhealthy lifestyles, smoking, alcoholism, and caffeine dependence are also risks for insomnia. Self medication with alcohol, over-the-counter medications, prescription medications, and melatonin account for millions of dollars annually.28 Clinicians should be alert to these possible individual and societal risks during the evaluation.

Genetics:With the exception of fatal familial insomnia, a rare disorder, no specific genetic associations have been identified for insomnia. A familial tendency for insomnia has been observed, but the relative contributions of genetic trait vulnerability and learned maladaptive behaviors are unknown.

General Considerations and Treatment Goals

It is essential to recognize and treat comorbid conditions (e.g., major depression or medical disorder such as chronic pain) that commonly occur with insomnia.29 Likewise, identification and modification of inappropriate caffeine, alcohol, and self-medication are necessary. Timing or adjustments of current medications require consideration and may provide symptom relief. For example, changing to a less stimulating antidepressant or changing the timing of a medication may improve sleep or daytime symptoms.

Goals of insomnia treatment (Table 10) include reduction of sleep and waking symptoms, improvement of daytime function, and reduction of distress. Treatment outcome can be monitored longitudinally with clinical evaluation, questionnaires, and sleep logs.

Table 10.

Treatment Goals

|

Before consideration of treatment choices, the patient and physician should discuss primary and secondary treatment goals based on the primary complaint and baseline measures such as sleep latency, number of awakenings, WASO, frequency and severity of the complaint(s), nighttime distress, and related daytime symptoms (Table 10). After discussing treatment options tailored to address the primary complaint, a specific follow-up plan and time frame should be outlined with the patient, regardless of the treatment choice.

Quantifying sleep quality, daytime function, and improvement in comorbid conditions requires more involved assessment, often using specific questionnaires for specific insomnia problems (Table 8). If the clinician is unfamiliar with these tests, administration and monitoring of these measures may require referral to a behavioral sleep medicine specialist, psychologist, or other testing professional, as clinically appropriate.

Psychological and behavioral interventions and benzodiazepine receptor agonists (BzRAs) have demonstrated short-term efficacy for the treatment of chronic insomnia. Psychological and behavioral interventions show short and long term efficacy and can be used for treatment of both primary and comorbid insomnias. Psychological and behavioral interventions and pharmacological interventions may be used alone or in combination (Figure 2). Regardless of treatment choice, frequent outcome assessment and patient feedback is an important component of treatment. In addition, periodic clinical reassessment following completion of treatment is recommended as the relapse rate for chronic insomnia is high.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for the Treatment of Chronic Insomnia

Psychological and Behavioral Therapies

Current models suggest that physiological and cognitive hyperarousal contribute to the evolution and chronicity of insomnia. In addition, patients typically develop problematic behaviors such as remaining in bed awake for long periods of time, often resulting in increased efforts to sleep, heightened frustration and anxiety about not sleeping, further wakefulness and negative expectations, and distorted beliefs and attitudes concerning the disorder and its consequences. Negative learned responses may develop and become key perpetuating factors that can be targeted with psychological and behavioral therapies. Treatments which address these core components play an important role in the management of both primary and comorbid insomnias.29 These treatments are effective for adults of all ages, including older adults. While most efficacy studies have focused on primary insomnia patients, more recent data demonstrate comparable outcomes in patients with comorbid psychiatric or medical insomnia.

The etiology of insomnia is typically multifactorial. In comorbid insomnias, treatment begins by addressing the comorbid condition. This may include treatment of major depressive disorder, optimal management of pain or other medical conditions, elimination of activating medications or dopaminergic therapy for movement disorder. In the past, it was widely assumed that treatment of these comorbid disorders would eliminate the insomnia. However, it has become increasingly apparent that over the course of these disorders, numerous psychological and behavioral factors develop which perpetuate the insomnia problem. These perpetuating factors commonly include worry about inability to sleep and the daytime consequences of poor sleep, distorted beliefs and attitudes about the origins and meaning of the insomnia, maladaptive efforts to accommodate to the condition (e.g., schedule or lifestyle changes), and excessive time spent awake in bed. The latter behavior is of particular significance in that it often is associated with “trying hard” to fall asleep and growing frustration and tension in the face of wakefulness. Thus, the bed becomes associated with a state of waking arousal as this conditioning paradigm repeats itself night after night.

An implicit objective of psychological and behavioral therapy is a change in belief system that results in an enhancement of the patient's sense of self-efficacy with respect to management of insomnia. These objectives are accomplished by:

Identifying the maladaptive behaviors and cognitions that perpetuate chronic insomnia;

Bringing the cognitive distortions inherent in this condition to the patient's attention and working with the patient to restructure these cognitions into more sleep-compatible thoughts and attitudes;

Utilizing specific behavioral approaches that extinguish the association between efforts to sleep and increased arousal by minimizing the amount of time spent in bed awake, while simultaneously promoting the desired association of bed with relaxation and sleep;

Establishing a regular sleep-wake schedule, healthy sleep habits and an environment conducive to good sleep; and

Employing other psychological and behavioral techniques that diminish general psychophysiological arousal and anxiety about sleep.

Psychological and behavioral therapies for insomnia include a number of different specific modalities (Table 11). Current data support the efficacy of stimulus control, relaxation training, and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-1) (i.e., multimodal approaches that include both cognitive and behavioral elements) with or without relaxation therapy. These treatments are recommended as a standard of care for the treatment of chronic insomnia. Although other modalities are common and useful with proven effectiveness, the level of evidence is not as strong for psychological and behavioral treatments including sleep restriction, paradoxical intention, or biofeedback. Simple education regarding sleep hygiene alone does not have proven efficacy for the treatment of chronic insomnia. In practice, specific psychological and behavioral therapies are most often combined as a multi-modal treatment package referred to as CBT-I. CBT-I may also include the use of light and dark exposure, temperature, and bedroom modifications. Other nonpharmacological therapies such as light therapy may help to establish or reinforce a regular sleep-wake schedule with improvement of sleep quality and timing. A growing data base also suggests longer-term efficacy of psychological and behavioral treatments.

Table 11.

Common Cognitive and Behavioral Therapies for Chronic Insomnia

| Stimulus control (Standard) is designed to extinguish the negative association between the bed and undesirable outcomes such as wakefulness, frustration, and worry. These negative states are frequently conditioned in response to efforts to sleep as a result of prolonged periods of time in bed awake. The objectives of stimulus control therapy are for the patient to form a positive and clear association between the bed and sleep and to establish a stable sleep-wake schedule. |

| Instructions: Go to bed only when sleepy; maintain a regular schedule; avoid naps; use the bed only for sleep; if unable to fall asleep (or back to sleep) within 20 minutes, remove yourself from bed—engage in relaxing activity until drowsy then return to bed—repeat this as necessary. Patients should be advised to leave the bed after they have perceived not to sleep within approximately 20 minutes, rather than actual clock-watching which should be avoided. |

| Relaxation training (Standard) such as progressive muscle relaxation, guided imagery, or abdominal breathing, is designed to lower somatic and cognitive arousal states which interfere with sleep. Relaxation training can be useful in patients displaying elevated levels of arousal and is often utilized with CBT. |

| Instructions: Progressive muscle relaxation training involves methodical tensing and relaxing different muscle groups throughout the body. Specific techniques are widely available in written and audio form. |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia or CBT-I (Standard) is a combination of cognitive therapy coupled with behavioral treatments (e.g., stimulus control, sleep restriction) with or without relaxation therapy. Cognitive therapy seeks to change the patient's overvalued beliefs and unrealistic expectations about sleep. Cognitive therapy uses a psychotherapeutic method to reconstruct cognitive pathways with positive and appropriate concepts about sleep and its effects. Common cognitive distortions that are identified and addressed in the course of treatment include: “I can't sleep without medication,” “I have a chemical imbalance,” “If I can't sleep I should stay in bed and rest,” “My life will be ruined if I can't sleep.” |

| Multicomponent therapy [without cognitive therapy] (Guideline) utilizes various combinations of behavioral (stimulus control, relaxation, sleep restriction) therapies, and sleep hygiene education. Many therapists use some form of multimodal approach in treating chronic insomnia. |

| Sleep restriction (Guideline) initially limits the time in bed to the total sleep time, as derived from baseline sleep logs. This approach is intended to improve sleep continuity by using sleep restriction to enhance sleep drive. As sleep drive increases and the window of opportunity for sleep remains restricted with daytime napping prohibited, sleep becomes more consolidated. When sleep continuity substantially improves, time in bed is gradually increased, to provide sufficient sleep time for the patient to feel rested during the day, while preserving the newly acquired sleep consolidation. In addition, the approach is consistent with stimulus control goals in that it minimizes the amount of time spent in bed awake helping to restore the association between bed and sleeping. |

Instructions (Note, when using sleep restriction, patients should be monitored for and cautioned about possible sleepiness):

|

| Paradoxical intention (Guideline) is a specific cognitive therapy in which the patient is trained to confront the fear of staying awake and its potential effects. The objective is to eliminate a patient's anxiety about sleep performance. |

| Biofeedback therapy (Guideline) trains the patient to control some physiologic variable through visual or auditory feedback. The objective is to reduce somatic arousal. |

| Sleep hygiene therapy (No recommendation) involves teaching patients about healthy lifestyle practices that improve sleep. It should be used in conjunction with stimulus control, relaxation training, sleep restriction or cognitive therapy. |

| Instructions include, but are not limited to, keeping a regular schedule, having a healthy diet and regular daytime exercise, having a quiet sleep environment, and avoiding napping, caffeine, other stimulants, nicotine, alcohol, excessive fluids, or stimulating activities before bedtime. |

When an initial psychological/ behavioral treatment has been ineffective, other psychological/ behavioral therapies, combination CBT-I therapies, or combined treatment with pharmacological therapy (see below) may be applied. Additionally, the presence of occult comorbid disorders should be considered.

Psychologists and other clinicians with more general cognitive-behavioral training may have varying degrees of experience in behavioral sleep treatment. Such treatment is ideally delivered by a clinician who is specifically trained in this area such as a behavioral sleep medicine specialist. The American Academy of Sleep Medicine has established a standardized process for Certification in Behavioral Sleep Medicine.30,31 However, this level of care may not be available to all patients. Also of note, the type of administration (individual versus group) and treatment schedule (such as every one to two weeks for several sessions) may vary between providers. Given the current shortage of trained sleep therapists, on-site staff training and alternative methods of treatment and follow-up (such as telephone review of electronically-transferred sleep logs or questionnaires), although unvalidated, may offer temporary options for access to treatment for this common and chronic disorder.

Pharmacological Therapies

The goals of pharmacologic treatment are similar to those of behavioral therapies: to improve sleep quality and quantity, to enhance associated daytime function, to reduce sleep latency and wakefulness after sleep onset, and to increase total sleep time. Factors in selecting a pharmacological agent should be directed by: (1) symptom pattern; (2) treatment goals; (3) past treatment responses; (4) patient preference; (5) cost; (6) availability of other treatments; (7) comorbid conditions; (8) contraindications; (9) concurrent medication interactions; and (10) side effects. An additional goal of pharmacologic treatment is to achieve a favorable balance between therapeutic effects and potential side effects.

Current FDA-approved pharmacologic treatments for insomnia include several BzRAs and a melatonin receptor agonist (Table 12). Specific BzRAs differ from each other primarily in terms of pharmacokinetic properties, although some agents are relatively more selective than others for specific gamma amino-butyric acid (GABA) receptor subtypes. The short-term efficacy of BzRAs have been demonstrated in a large number of randomized controlled trials. A smaller number of controlled trials demonstrate continued efficacy over longer periods of time. Potential adverse effects of BzRAs include residual sedation, memory and performance impairment, falls, undesired behaviors during sleep, somatic symptoms, and drug interactions. A large number of other prescription medications are used off-label to treat insomnia, including antidepressant and anti-epileptic drugs. The efficacy and safety for the exclusive use of these drugs for the treatment of chronic insomnia is not well documented. Many non-prescription drugs and naturopathic agents are also used to treat insomnia, including antihistamines, melatonin, and valerian. Evidence regarding the efficacy and safety of these agents is limited.

Table 12.

Pharmaceutical Therapy Options

| Drug | Dosage Form | Recommended Dosage | Indications/Specific Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benzodiazepine Receptor Agonistic Modulators (Schedule IV Controlled Substances) | |||

| Non-benzodiazepines | |||

| cyclopyrrolones eszopiclone |

1, 2, 3 mg tablets | 2–3 mg hs 1 mg hs in elderly or debilitated; max 2 mg 1 mg hs in severe hepatic impairment; max 2 mg |

|

| imidazopyridines | |||

| zolpidem | 5, 10 mg tablets | 10 mg hs; max 10 mg 5 mg hs in elderly, debilitated, or hepatic impairment |

|

| zolpidem (controlled release) | 6.25, 12.5 mg tablets | 12.5 mg hs 6.25 mg hs in elderly, debilitated, or hepatic impairment |

|

| pyrazolopyrimidines | |||

| zaleplon | 5, 10 mg capsules | 10 mg hs; max 20 mg 5 mg hs in elderly, debilitated, mild to moderate hepatic impairment, or concomitant cimetidine |

|

| Benzodiazepines | |||

| estazolam | 1, 2 mg tablets | 1–2 mg hs 0.5 mg hs in elderly or debilitated |

|

| temazepam | 7.5, 15, 30 mg capsules | 15–30 mg hs 7.5 mg hs in elderly or debilitated |

|

| triazolam | 0.125, 0.25 mg tablets | 0.25 mg hs; max 0.5 mg 0.125 mg hs in elderly or debilitated; max 0.25 mg |

|

| flurazepam | 15, 30 mg capsules | 15–30 mg hs 15 mg hs in elderly or debilitated |

|

| Melatonin Receptor Agonists (Non-Scheduled) | |||

| ramelteon | 8 mg tablet | 8 mg hs |

|

Table partially constructed from individual drug prescribing information labeling.

See product labeling for complete prescribing information.

The FDA recently recommended that a warning be issued regarding adverse effects associated with BzRA hypnotics. These medications have been associated with reports of disruptive sleep related behaviors including sleepwalking, eating, driving, and sexual behavior. Patients should be cautioned about the potential for these adverse effects, and about the importance of allowing appropriate sleep time, using only prescribed doses and avoiding the combination of BzRA hypnotics with alcohol, other sedatives, and sleep restriction.

- Administration on an empty stomach is advised to maximize effectiveness.

- Not recommended during pregnancy or nursing.

- Caution is advised if signs/symptoms of depression, compromised respiratory function (e.g., asthma, COPD, sleep apnea), or hepatic heart failure are present.

- Caution and downward dosage adjustment is advised in the elderly.

- Safety/effectiveness in patients <18 years not established

- Additive effect on psychomotor performance with concomitant CNS depressants and/or alcohol use.

- Rapid dose decrease or abrupt discontinuance of benzodiazepines can produce withdrawal symptoms, including rebound insomnia, similar to that of barbiturates and alcohol.

Certain antidepressants (amitriptyline, doxepin, mirtazapine, paroxetine, trazodone) are employed in lower than antidepressant therapeutic dosages for the treatment of insomnia. These medications are not FDA approved for insomnia and their efficacy for this indication is not well established.

OTC sleep medications contain antihistamines as the primary agent; efficacy for treatment of insomnia is not well established, especially its long-term use.

The following recommendations primarily pertain to patients with diagnoses of Psychophysiological, Idiopathic, and Paradoxical Insomnia in ICSD-2, or the diagnosis of Primary Insomnia in DSM-IV. When pharmacotherapy is utilized, treatment recommendations are presented in sequential order.

Short/intermediate-acting BzRAs or ramelteon:* Examples of short/intermediate-acting BzRAs include zaleplon, zolpidem, eszopiclone, triazolam, and temazepam. No specific agent within this group is recommended as preferable to the others in a general sense; each has been shown to have positive effects on sleep latency, TST, and/or WASO in placebo-controlled trials.32–37 However, individual patients may respond differentially to different medications within this class. Factors including symptom pattern, past response, cost, and patient preference should be considered in selecting a specific agent. For example, zaleplon and ramelteon have very short half-lives and consequently are likely to reduce sleep latency but have little effect on waking after sleep onset (WASO); they are also unlikely to result in residual sedation. Eszopiclone and temazepam have relatively longer half-lives, are more likely to improve sleep maintenance, and are more likely to produce residual sedation, although such residual activity is still limited to a minority of patients. Triazolam has been associated with rebound anxiety and as a result, is not considered a first line hypnotic. Patients who prefer not to use a DEA-scheduled drug, and patients with a history of substance use disorders may be appropriate candidates for ramelteon, particularly if the complaint is that of sleep initiation difficulty.

Alternative BzRAs or ramelteon: In the event that a patient does not respond well to the initial agent, a different agent within the same class is appropriate. Selection of the alternative drug should be based on the patient's response to the first. For instance, a patient who continues to complain of WASO might be prescribed a drug with a longer half-life; a patient who complains of residual sedation might be prescribed a shorter-acting drug. The choice of a specific BzRA may include longer-acting hypnotics, such as estazolam. Flurazepam is rarely prescribed because of its extended half life. Benzodiazepines not specifically approved for insomnia (e.g., lorazepam, clonazepam) might also be considered if the duration of action is appropriate for the patient's presentation or if the patient has a comorbid condition that might benefit from these drugs.

Sedating low-dose antidepressant (AD): When accompanied with comorbid depression or in the case of other treatment failures, sedating low-dose antidepressants may next be considered. Examples of these drugs include trazodone, mirtazapine, doxepin, amitriptyline, and trimipramine. Evidence for their efficacy when used alone is relatively weak38–42 and no specific agent within this group is recommended as preferable to the others in this group. Factors such as treatment history, coexisting conditions (e.g. major depressive disorder), specific side effect profile, cost, and pharmacokinetic profile may guide the selection of a specific agent. For example, trazodone has little or no anticholinergic activity relative to doxepin and amitriptyline, and mirtazapine is associated with weight gain. Note that low-dose sedating antidepressants do not constitute adequate treatment of major depression for individuals with comorbid insomnia. However, the efficacy of low-dose trazodone as a sleep aid in conjunction with another full-dose antidepressant medication has been assessed in a number of studies of patients with depressive disorders. These studies, of varying quality and design, suggest moderate efficacy for trazodone in improving sleep quality and/or duration. It is unclear to what extent these findings can be generalized to other presentations of insomnia.

Combination of BzRA + AD: No research studies have been conducted to specifically examine such combinations, but a wealth of clinical experience with the co-administration of these drugs suggests the general safety and efficacy of this combination. A combination of medications from two different classes may improve efficacy by targeting multiple sleep-wake mechanisms while minimizing the toxicity that could occur with higher doses of a single agent. Side effects are likely to be minimized further by using the low doses of AD typical in the treatment of insomnia, but potential daytime sedation should be carefully monitored.

Other prescription drugs: Examples include gabapentin, tiagabine, quetiapine, and olanzapine. Evidence of efficacy for these drugs for the treatment of chronic primary insomnia is insufficient. Avoidance of off-label administration of these drugs is warranted given the weak level of evidence supporting their efficacy for insomnia when used alone and the potential for significant side effects (e.g., seizures with tiagabine; neurological side effects, weight gain, and dysmetabolism with quetiapine and olanzapine).

Prescription drugs- Not recommended: Although chloral hydrate, barbiturates, and “non-barbiturate non-benzodiazepine” drugs (such as meprobamate) are FDA-approved for insomnia, they are not recommended for the treatment of insomnia, given their significant adverse effects, low therapeutic index, and likelihood of tolerance and dependence.

Over-the-counter agents: Antihistamines and antihistamine-analgesic combinations are widely used self-remedies for insomnia. Evidence for their efficacy and safety is very limited, with very few available studies from the past 10 years using contemporary study designs and outcomes.43 Antihistamines have the potential for serious side effects arising from their concurrent anticholinergic properties. Alcohol, likely the most common insomnia self-treatment, is not recommended because of its short duration of action, adverse effects on sleep, exacerbation of obstructive sleep apnea, and potential for abuse and dependence. Very few herbal or alternative treatments have been systematically evaluated for the treatment of insomnia. Of these, the greatest amount of evidence is available regarding valerian extracts and melatonin.44–47 Available evidence suggests that valerian has small but consistent effects on sleep latency, with inconsistent effects on sleep continuity, sleep duration, and sleep architecture. Melatonin has been tested in a large number of clinical trials. Meta-analyses have demonstrated that melatonin has small effects on sleep latency, with little effect on WASO or TST. It should be noted that some of the published trials of melatonin have evaluated its efficacy as a chronobiotic (phase-shifting agent) rather than as a hypnotic.

Long-term use of non-prescription (over-the-counter) treatments is not recommended. Efficacy and safety data for most over-the-counter insomnia medications is limited to short-term studies; their safety and efficacy in long-term treatment is unknown.48 Patients should be educated regarding the risks and limited efficacy of these substances and possible interactions with their comorbid conditions and concurrent medications.

Pharmacological Treatment Failure

Although medications can play a valuable role in the management of insomnia, a subset of chronic insomnia patients may have limited or only transient improvement with medication. As recommended, alternative trials or combinations may be useful; however, clinicians should note that if multiple medication trials have proven ultimately ineffective, cognitive behavioral approaches should be pursued in lieu of or as an adjunct to further pharmacological trials. Additionally, the diagnosis of comorbid or other insomnias should be reconsidered. Caution is advised regarding polypharmacy, particularly in patients who have not or will not pursue psychological and behavioral treatments.

Mode of Administration/Treatment

Frequency of administration of hypnotics depends on the specific clinical presentation; empirical data support both nightly and intermittent (2–5 times per week) administration.49–51 Many clinicians recommend scheduled non-nightly dosing at bedtime as a means of preventing tolerance, dependence, and abuse, although these complications may be less likely with newer BzRA agents. A final strategy sometimes employed in clinical practice is true “as needed” dosing when the patients awakens from sleep. This strategy has not been carefully investigated, and is not generally recommended due to the potential for carry-over sedation the next morning and the theoretical potential for inducing conditioned arousals in anticipation of a medication dose.

Duration of treatment also depends on specific clinical characteristics and patient preferences. FDA class labeling for hypnotics prior to 2005 implicitly recommended short treatment duration; since 2005, hypnotic labeling does not address duration of treatment. Antidepressants and other drugs commonly used off-label for treatment of insomnia also carry no specific restrictions with regard to duration of use. In clinical practice, hypnotic medications are often used over durations of one to twelve months without dosage escalation,52–55 but the empirical data base for long-term treatment remains small. Recent randomized, controlled studies of non-BZD-BzRAs (such as eszopiclone or zolpidem) have demonstrated continued efficacy without significant complications for 6 months, and in open-label extension studies for 12 months or longer.

For many patients, an initial treatment period of 2–4 weeks may be appropriate, followed by re-evaluation of the continued need for treatment. A subset of patients with severe chronic insomnia may be appropriate candidates for longer-term or chronic maintenance treatment, but, as stated, the specific defining characteristics of these patients are unknown. There is little empirical evidence available to guide decisions regarding which drugs to use long-term, either alone or in combination with behavioral treatments. Thus, guidelines for long-term pharmacological treatment need to be based primarily on common clinical practice and consensus. If hypnotic medications are used long-term, regular follow-up visits should be scheduled at least every six months in order to monitor efficacy, side effects, tolerance, and abuse/misuse of medications. Periodic attempts to reduce the frequency and dose in order to minimize side effects and determine the lowest effective dose may be indicated.

On discontinuation of hypnotic medication after more than a few days' use, rebound insomnia (worsening of symptoms with dose reduction, typically lasting 1–3 days), potential physical as well as psychological withdrawal effects, and recurrence of insomnia may all occur.56 Rebound insomnia and withdrawal can be minimized by gradually tapering both the dose and frequency of administration.57 In general, the dose should be lowered by the smallest increment possible in successive steps of at least several days' duration. Tapering the frequency of administration (such as every other or every third night) has also been shown to minimize rebound effects. Successful tapering may require several weeks to months. As noted elsewhere, tapering and discontinuation of hypnotic medication is facilitated by concurrent application of cognitive-behavioral therapies, which increase rates of successful discontinuation and duration of abstinence.58,59

Pharmacotherapy for Specific Populations

The guidelines presented are generally appropriate for older adults as well as younger adults. However, lower doses of all agents (with the exception of ramelteon) may be required in older adults, and the potential for side-effects and drug-drug interactions should be carefully considered.60–62 The above guidelines are likely to be appropriate for older adolescents as well, but very little empirical data is available to support any exclusive treatment approach in this age group. The treatment of insomnia comorbid with depression or anxiety disorders should follow the same general outline presented above. However, concurrent treatment with an antidepressant medication at recommended doses, or an efficacious psychotherapy for the comorbid condition, is required. Both BzRAs and low-dose sedating ADs have been evaluated as adjunctive agents to other full-dose antidepressants for treatment of comorbid insomnia in patients with depression.63,64 If a sedating antidepressant drug is used as monotherapy for a patient with comorbid depression and insomnia, the dose should be that recommended for treatment of depression. In many cases, this dose will be higher than the typical dose used to treat insomnia alone. Quetiapine or olanzapine may be specifically useful in individuals with bipolar disorder or severe anxiety disorders. In a similar fashion, treatment of insomnia comorbid with a chronic pain disorder should follow the general treatment outline presented above. In some cases, medications such as gabapentin or pregabalin may be appropriately used at an earlier stage. Concurrent treatment with a longer-acting analgesic medication near bedtime may also be useful, although narcotic analgesics may disrupt sleep continuity in some patients. Furthermore, patients with comorbid insomnia may benefit from behavioral and psychological treatments or combined therapies, in addition to treatment of the associated condition.

Combined Therapy for Insomnia

Hypnotic medications are efficacious as short-term treatment for insomnia, and more recent evidence suggests that benzodiazepine and BzRA hypnotics may maintain effectiveness over the longer term without significant complications. These facts, however, do not provide the clinician with a clear set of practice standards, particularly when it comes to sequencing or combination of therapies. The literature that has examined the issue of individual pharmacotherapy or cognitive behavioral treatment versus a combination of these approaches demonstrates that short-term pharmacological treatments alone are effective during the course of treatment for chronic insomnia but do not provide sustained improvement following discontinuation,65,66 whereas cognitive behavioral treatments produce significant improvement of chronic insomnia in the short-term, and these improvements appear sustained at follow-up for up to two years.67 Studies of combined treatment show mixed and inconclusive results. Taken as a whole, these investigations do not demonstrate a clear advantage for combined treatment over cognitive behavioral treatment alone.65,66,68–70

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Buysse has consulted to and/or been on the advisory board of Actelion, Arena, Cephalon, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Neurocrine, Neurogen, Pfizer, Respironics, Sanofi-Aventis, Sepracor, Servier, Somnus Therapeutics, Stress Eraser, Takeda, and Transcept Pharmaceuticals. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International classification of sleep disorders, 2nd ed.: diagnostic and coding manual. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Littner M Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for using polysomnography to evaluate insomnia: an update for 2002. Sleep. 2003;26:754–60. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.6.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Littner M, et al. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for clinical use of the multiple sleep latency test and the maintenance of wakefulness test. Sleep. 2005;28:113–21. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chesson AL, Jr, et al. Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Practice parameters for the nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 1999;22:1128–33. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.8.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgenthaler T, et al. Practice parameters for the psychological and behavioral treatment of insomnia: an update. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2006;29:1415–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morgenthaler T, et al. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders: an update for 2007. Sleep. 2007;30:519–29. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sackett DL. Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations for the management of patients. Can J Cardiol. 1993;9:487–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnson E. Epidemiology of insomnia: from adolescence to old age. Sleep Med Clin. 2006;1:305–17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kryger M. The burden of chronic insomnia on society: awakening insomnia management. 20th Anniversary Meeting of APSS; 2006; Salt Lake City, UT. Presented at: [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ancoli-Israel S. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. Sleep. 1999;22:S347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taylor D, et al. Comorbidity of chronic insomnia with medical problems. Sleep. 2007;30:213–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.2.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benca R. Special considerations in insomnia diagnosis and management: depressed, elderly, and chronic pain populations. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:S26–S35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]