Abstract

Substantial evidence exists for spontaneous oscillations of hair cell stereociliary bundles in the lower vertebrate inner ear. Since the oscillations are larger than expected from Brownian motion, they must result from an active process in the stereociliary bundle suggested to underlie amplification of the sensory input as well as spontaneous otoacoustic emissions. However, their low frequency (<100 Hz) makes them unsuitable for amplification in birds and mammals that hear up to 5 kHz or higher. To examine the possibility of high-frequency oscillations, we used a finite-element model of the outer hair cell bundle incorporating previously measured mechanical parameters. Bundle motion was assumed to activate mechanotransducer channels according to the gating spring hypothesis, and the channels were regulated adaptively by Ca2+ binding. The model generated oscillations of freestanding bundles at 4 kHz whose sharpness of tuning depended on the mechanotransducer channel number and location, and the Ca2+ concentration. Entrainment of the oscillations by external stimuli was used to demonstrate nonlinear amplification. The oscillation frequency depended on channel parameters and was increased to 23 kHz principally by accelerating Ca2+ binding kinetics. Spontaneous oscillations persisted, becoming very narrow-band, when the hair bundle was loaded with a tectorial membrane mass.

INTRODUCTION

Sound stimuli are transmitted to the inner ear, where they vibrate the stereociliary (hair) bundles of the hair cells, thus activating mechanically sensitive transducer (MT) channels located near the tips of the stereocilia. The hair bundle is primarily a sensory organelle that responds to deflections along its excitatory-inhibitory (E-I) axis, toward and away from the tallest stereociliary rank (1). An excitatory stimulus is thought to convey force to the MT channel by tensioning tip links that connect the apex of each stereocilium with the side wall of its taller neighbor (2,3). Besides being a sensory structure, the hair bundle can also exhibit motile activity exemplified by the spontaneous periodic motion in its position, with the tip of the bundle oscillating also along the E-I axis. Spontaneous bundle oscillations have been reported at frequencies from 5 to 100 Hz in hair cell epithelia of lower vertebrates such as the turtle (4) and frog (5–7). In such preparations, the oscillations occur with a peak-to-peak amplitude up to 80 nm, much larger than expected for Brownian motion of the bundle, which has been taken as evidence for an active process used by hair cells to amplify the mechanical input (4,8). It is thought that the oscillatory motion of the bundle might sum with the external stimulus, providing amplification to enhance the signal/noise ratio of transduction, especially near threshold.

Independent evidence of a mechanical output from auditory hair cells comes from otoacoustic emissions in which the external ear radiates sound energy (9). Such emissions have been recorded in nonmammalian vertebrates (frogs, lizards, and birds) as well as in mammals (10). The narrow-band nature of spontaneous otoacoustic emissions is reminiscent of the spontaneous periodic motion of hair bundles, but there is a significant discrepancy in the frequency ranges of the two phenomena. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions occur at frequencies within the audible range of the animal (from a minimum of ∼600 Hz in frogs (11) to ∼60 kHz in certain mammals (12)), but the highest frequency reported for spontaneous bundle motion is no more than 100 Hz. A causal link between the two processes would be greatly strengthened by an experimental or theoretical demonstration of spontaneous bundle motion in the kilohertz range of a mammalian preparation.

The origin of spontaneous oscillations in lower-vertebrate hair cells has been proposed as the interplay of a negative-stiffness region in the force-displacement relationship of the hair bundle and an adaptation motor that maintains the bundle in its most sensitive range (7,8). Adaptation is triggered by influx of Ca2+ through open MT channels and occurs on two disparate timescales. In fast adaptation, Ca2+ has been suggested to bind to the MT channel, making it more difficult to open, whereas for slow adaptation, Ca2+ is thought to act on myosin molecules at the upper insertion point of the tip link, causing the insertion point to slip down the stereociliary wall and relieve force on the channel (13,14). In modeling the spontaneous oscillations, the latter mechanism involving the myosin motor is normally invoked, with substantial experimental support (7). However, as a consequence of the slow kinetics of the myosin ATPase cycle (<10 s−1), the oscillations occur at low frequency. High-frequency oscillations, if present, will require the fast process mediated by Ca2+ binding to the MT channels. This is a negative feedback system whereby Ca2+ entering through open transducer channels closes them, thus generating a force that opposes the initial bundle deflection (15). Such feedback control of the channels, which also underlies fast adaptation, could in theory provide both underdamped resonance and amplification. A channel mechanism was previously modeled to show the feasibility of high-frequency resonance and oscillations at 5 kHz (16), but there is as yet little experimental support for the phenomenon. The aim of this work was to investigate this same process using a finite-element (FE) analysis incorporating realistic geometry of mammalian hair bundles, stochastic gating of multiple MT channels, and mass loading by the tectorial membrane. The approach enabled us to examine explicitly the factors that can be varied to extend the upper frequency limit of the phenomenon. It also allowed us to observe the behavior of individual channels and their interactions.

THEORY

Structural model of the outer hair cell bundle

A three-dimensional FE model of an outer hair cell (OHC) bundle was constructed as described previously (17,18) using the geometry of rat cochlear OHC bundles (19,20). Two different-sized hair bundles were employed. For most simulations, we used a hair bundle from the apical turn of the rat cochlea with three rows of 29 stereocilia in pseudo-hexagonal array of heights 4.2, 2.2, and 1.1 μm. In a second simulation, we used a hair cell bundle from the basal turn comprising a larger number of shorter stereocilia with three rows, each consisting of 37 stereocilia with heights of 2.4, 2.0, and 1.0 μm. The low-frequency bundle came from a location 0.8 of the distance along the rat cochlea from the base with a characteristic (acoustic) frequency of 4 kHz, and the high-frequency bundle came from a location 0.3 of the distance along the cochlea with a characteristic frequency of 23 kHz (21).

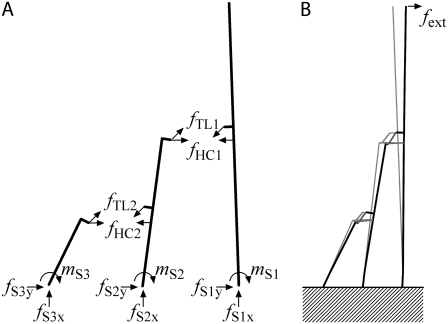

The number of nodes in the FE model was 1160 for the low-frequency bundle and 1258 for the high-frequency bundle. In the model, the stereocilia were interconnected by horizontal links and tip links (Fig. 1 A) (22,23) represented by link elements allowing axial deformation only. Stereociliary deformation was described by Timoshenko beam theory (24). In addition to these structures, new to this study, a beam was added along the tips of tallest stereocilia, and link elements connected the beam to the stereociliary tips (Fig. 1 B). The beam was introduced to represent the in vivo arrangement in which the tips of the tallest stereocilia are embedded in the amorphous (Hardesty's) layer of the tectorial membrane (25). The consequences of this tip constraint will be discussed in the Results. The values for the mechanical and other parameters are given in Table 1 and are similar to those used in our previous simulations that were based on experimental measurements of rat OHC bundle mechanics (18). The material properties of the bundle tip constraint were assumed to be sufficiently high to ensure that the bundle tips would move as one, but the constraint would contribute minimally to the bundle compliance. The density of the bundle structures was assumed to be that of water, 1000 kg·m−3.

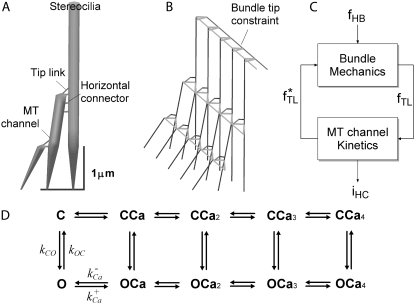

FIGURE 1.

Basic features of the model. (A) Cross section of a hair bundle depicting the three rows of stereocilia interconnected by tip links and the horizontal connectors. The tallest stereocilia are nearly upright, whereas the shorter stereocilia are tilted toward the taller stereocilia. (B) In some simulations the tips of the tallest stereocilia were constrained by a crossing bar. (C) Feedback description of model. A force fHB is delivered to the hair bundle, which activates the MT channel via tension fTL in the tip links. Channel gating then develops force f*TL, which then feeds back to modify the motion of the hair bundle. Channel opening generates a transducer current iHC. (D) The kinetic scheme used in the model for the MT channel has five closed (C) and five open (O) states, with the rate constants between C and O depending on the mechanical stimulus and the transitions between each of the C (or O) states depending on binding of one to four calcium ions. As Ca2+ binds to the channel, an additional force fCa is required to open a channel.

TABLE 1.

Model parameters

| Parameter | Value | Description of parameter |

|---|---|---|

| kP (N.m.rad−1) | 3.0 × 10−16 | Rotational stiffness of stereociliary rootlet |

| kGS (mN·m−1) | 8 (6)† | Stiffness of tip link complex (gating spring) |

| kSA (mN·m−1) | 1.0 | Stiffness of horizontal connectors |

| f0 (pN) | 15 (−15)* | Intrinsic force difference between open and closed states |

|

1 | Ca2+ binding coefficient |

|

20 (100)* | Ca2+ dissociation constant |

|

10 | MT channel C→O rate constant |

|

10 | MT channel O→C rate constant |

| b (nm) | 3 (2.5)† | Gating swing |

| fCa (pN) | 3.5 (8)* | Change in force to open channel on binding Ca2+ |

| CFA (μM) | 0.1 (20) | [Ca2+] near MT channel when channel was closed (open) |

| 0.1 (100)* |

Values for 5-fold increase in spontaneous oscillation frequency.

Alternate values that also generated low-frequency oscillations.

In all simulations except those in the last section of the Results, the tectorial membrane mass was neglected. To assess the importance of the tectorial membrane mass, its mass was lumped in with the bundle tip constraint. Because the volume of the tip constraint is smaller than the tectorial membrane dimensions, a scaled mass density was applied to the constraint to represent the effective tectorial membrane mass carried by an OHC bundle. This mass was estimated as follows: The cross-sectional area of the tectorial membrane of rat cochlea was assumed to be 7000 μm2 at the 4 kHz location (26). If the width of the OHC bundle is 8 μm, the volume of a strip of tectorial membrane carried by three OHC bundles is 5.6 × 104 μm3 and its mass is 5.6 × 10−11 kg assuming a density of 1000 kg/m3. If the mass is evenly distributed and the stiffness is constant along the radial direction, the effective mass carried by three OHC bundles is about one-third of the total mass of the tectorial membrane strip. We therefore used 6.2 × 10−12 kg as the mass carried by one OHC bundle in the 4 kHz region. For the high-frequency bundle at the 23 kHz region, the cross-sectional area of the tectorial membrane was reduced to one-fourth of that at the 4 kHz region (26).

In adding the tectorial membrane, it is important to consider extra viscous drag. There are three possible sources of fluid drag associated with OHC bundle motion: 1), viscous friction within the bundle; 2), viscous drag between the endolymph fluid and the hair bundle; and 3), viscous drag between the tectorial membrane and the surface of the hair cell epithelium. Under circumstances where the tectorial membrane has been removed, only sources 1 and 2 contribute. In contrast, when the tectorial membrane is present, only sources 1 and 3 contribute, and source 2 can be ignored for the following reason: the gap between the tectorial membrane and the epithelial surface, equivalent to the height of the hair bundle, is less than the thickness of the fluid boundary layer (27). For example, at 4 kHz, the boundary layer is >10 μm, whereas the bundle height is 4.2 μm. Therefore, the fluid flow due to the relative motion between the two surfaces is viscous. The Newtonian fluid flow develops linearly from the bottom to the top across the gap. In such a case, there is little relative velocity between the hair bundle and the surrounding fluid, making the second source of fluid drag ignorable. The magnitudes of the viscous drag can be estimated in the two cases—when the bundle is free standing and when it is constrained by the tectorial membrane—as follows: When the bundle is freestanding, the fluid drag, r, can be approximated by the Stokes' drag of a solid sphere: r = 3πηd. Assuming a fluid viscosity η = 0.72 × 10−3 N·s/m2 and a sphere diameter d = 8 μm (equivalent to the maximum dimension of the bundle), the damping coefficient r is 43 nN·s·m−1. When the bundle is attached to the tectorial membrane, the fluid drag can be approximated by r = ηbL/z. Taking the width of a row of three OHC bundles, b = 8μm, the radial length of the tectorial membrane strip, L = 100 μm, and the gap between the two surfaces, h = 4.2 μm, then the viscous coefficient, r, of one hair bundle is 47 nN·s·m−1. Surprisingly, in this analysis the external viscous forces experienced by the hair bundle are very similar in the presence or absence of the tectorial membrane. Assuming that the viscous friction within the bundle is minor compared to the external viscous drag, we used r = 50 nN·s·m−1 for both freestanding and tectorial membrane-attached cases.

Bundle mechanics

The equation of motion at time t is

|

(1) |

where M, C, and K are the mass, damping, and stiffness matrices, respectively, and U, R, and F are the displacement, applied force, and internal force vectors, respectively. Dotted variables denote differentiation with respect to time. Superscripts to the left of the variable, t, denote time, and those to the right, k, denote the iterative step within each time step.

A proportional damping is used that is defined as

|

(2) |

where c is a scalar constant with a value of 0.01 ms. This value for c is equivalent to a damping coefficient of 50 nN·s·m−1 in the simple second-order Kevin-Voigt mechanical model and is about one-third of the value measured in bullfrog saccule bundles (28). At each time step, an incremental displacement vector at the k-th iterative step,  was computed and the displacement updated by

was computed and the displacement updated by

|

(3) |

Iterations for that time step continued until the internal force distribution converged. For dynamic structural analysis, a direct integration scheme, the Newmark method, was used (29). This is a single-step implicit method that is unconditionally stable. The velocity and displacement vectors at time step ( ) were calculated by solving the equations below using two coefficients β and γ:

) were calculated by solving the equations below using two coefficients β and γ:

|

(4) |

|

(5) |

Newmark's coefficients β = 0.3333 and γ = 0.5005 were chosen to meet the stability conditions (γ ≥ 0.5, β ≤ 0.5). For most simulations, a time step of 1 μs was selected as a compromise between computational resources and temporal resolution.

Mechanotransduction channel kinetics

The basic feature of the model (Fig. 1 C) consists of two components in feedback configuration: the passive hair bundle mechanics and the mechanotransducer (MT) channel. Hair bundle motion activates the MT channels according to the gating spring hypothesis (30), and channel gating influences the hair bundle mechanics. A channel kinetic scheme identical to that of our previous work (18) was used with the parameter values given in Table 1. The gating of each MT channel was treated as stochastic according to a kinetic scheme with four calcium-bound states and one calcium-free state for both open and closed configurations (Fig. 1 D). Each of the Ca2+ binding sites was assumed to have the same affinity. Rate coefficients between the states were defined as follows. Two coefficients describe the calcium binding and unbinding rate:

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

where kb is the calcium binding coefficient, CFA is the calcium concentration at the binding site, and KD is the calcium dissociation constant (KD = 20 μM). The channel opened or closed according to another two rate coefficients as follows:

|

(8) |

|

(9) |

where kB is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, and  and

and  are constants. ΔE is defined by the tension, f, in the tip link assembly, gating swing b and fCa, the change in force to open the channel on binding calcium multiplied by nCa, the number of bound Ca2+ ions

are constants. ΔE is defined by the tension, f, in the tip link assembly, gating swing b and fCa, the change in force to open the channel on binding calcium multiplied by nCa, the number of bound Ca2+ ions

|

(10) |

where f0 is a constant that contributes to setting the resting-open probability. When fCa > 0, Ca2+ binding to the channel facilitates channel closure and stabilizes the closed state (31,32).

One change from the previous model (18) was the absence of a fast release mechanism—a release of the MT channel within milliseconds caused by increased stereociliary Ca2+. Two slightly different mechanisms, summarized in Cheung and Corey (32), have been proposed to explain the fast adaptation of the MT channels, which has a time constant of ∼0.1 ms in mammals (33). These have been referred to as the fast release mechanism (7) and the fast reclosure mechanism (30,31). Both theories predict that Ca2+ influx closes the MT channel but their mechanical consequences differ. During adaptation, the fast release causes the bundle tip to move further in the excitatory direction, whereas in the fast reclosure mechanism the bundle tip recoils in the inhibitory direction. These two fast adaptation mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, and both were included previously (18) to provide a better description of the experimental results. In this study, however, the two fast adaptation mechanisms, if they had similar kinetics, canceled each other out because they had opposing mechanical effects. The magnitude and quality factor of the oscillations decreased as the time constant of fast release became <0.5 ms, approaching that of the fast reclosure, so only the fast reclosure mechanism was included in the simulations.

In the model, the unstrained length of the tip link assembly changes according to the channel state and the slow adaptation:

|

(11) |

where n is the channel state (0 when closed, 1 when open) and xA describes the movement of the attachment point of the tip link caused by myosin-driven adaptation. Δx is positive when the channel complex elongates. The MT channels are modeled as connected in series with the tip links, and interactions between the MT channel and hair bundle occur via the tip links (30). Thus mechanotransduction is reversible: force delivered via the tip links evokes a conformational change in the channel culminating in opening; conversely, changes in channel conformation or location, such as occur during adaptation, are in turn transmitted via the tip links to elicit bundle motion. The elongation of the channel, Δx, deforms the bundle through a decrease in tension in the tip link and vice versa. Likewise, bundle deformation affects the tension experienced by the channel. Available evidence indicates that there are between one and two channels per tip link (34,20). For most simulations, a single MT channel at the upper end of the tip link was assumed, but we also tested the effects of two MT channels per tip link in two different arrangements. In one arrangement, the channels were at either end of the tip link and in the other, two channels in parallel were attached at the upper end of tip link.

Myosin motors are assumed to provide force to maintain the resting tension in the gating spring, thus setting the resting-open probability of the MT channel. The equations governing the myosin motors were identical to those used previously (18). The parameter values, particularly the maximal stalling force per channel by the adaptation motor (30 pN), were chosen to set the resting-open probability at 0.5. Although this resting-open probability is larger than that determined in OHCs in isolated cochleas (∼0.12 (35,36)), it is comparable to values measured in vivo (37,38) and corresponds to the point of maximum sensitivity. The Ca2+ near the intracellular face of the MT channel (CFA) was assumed to cycle within 10 μs between resting and elevated values in synchrony with the stochastic closing and opening of each of the channels. No calcium buffering or extrusion mechanisms were explicitly assumed. When the channel was closed, the calcium concentration, CFA, was 0.1 μM, and (unless otherwise stated) when the channel was open, CFA was 20 μM or 100 μM depending on whether low-frequency or high-frequency oscillations was being simulated. Because the myosin-based slow adaptation site (SA) may be farther from the pore than the channel-based fast adaptation site (FA), we assumed that CFA/CSA = 3 (39).

Simulations and postprocessing

The programs were written with MATLAB v7.3 (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) and run on IBM PCs (Pentium 4, 3.8 GHz). It took ∼1 min to simulate 1 ms of bundle motion, more than half of the CPU time being used to solve the equations of motion with the MATLAB-embedded LAPACK sparse matrix solver. The MATLAB Signal Processing toolbox was used for power spectral analysis. The power spectrum of the oscillations was generated with the MATLAB PWELCH function by windowing and Fourier transforming 200 ms of simulation.

RESULTS

Factors affecting the occurrence of oscillations

Parameter values were optimized to generate spontaneous hair bundle oscillations at 4 kHz (Fig. 2), similar to the characteristic acoustic frequency of the rat cochlear location previously studied (18,20). Several manipulations of the geometric configuration had little effect on the frequency of the oscillations (FO) but did affect the extent to which they were narrow-band. When freestanding bundles were modeled, the oscillations were moderately narrow-band with a quality factor, Q, of 2.7 for the power spectrum (Q is defined as the ratio of the oscillation frequency to the bandwidth at half power, BW3db: Q = FO/BW3db). However, the power spectrum became much sharper (Q = 15) when all the stereocilia of the tallest rank were constrained to move together (Fig. 1 B), enforcing coherent displacement of all columns (Fig. 2). Under these conditions, but not with freestanding unconstrained bundles, motion of the two extreme edges of the bundle was identical. Such coherent motion has been observed for isolated frog vestibular hair bundles (40) but not for mammalian cochlear hair bundles when they were not attached to the tectorial membrane. Our experimental observations on hair bundles of both inner hair cells and OHCs indicate that if a stimulus is administered to only one wing of the bundle, it elicits smaller motion in the other wing, indicating reduced coherence in motion of freestanding bundles. A similar property was reported for mammalian cochlear hair bundles in another study (41). This addition may be regarded as a first approximation to the in vivo condition, where the stereocilia are constrained by insertion into the overlying tectorial membrane. Imprints of each of the tallest rank of OHC stereocilia are visible on the underside of the tectorial membrane (25). In the model, the tips of the tallest stereocilia were constrained by a crossing bar having a flexural rigidity of 5 × 10−18 N·m2. This value was determined by considering the dimensions (5 × 8 × 50 μm) and Young's modulus (15 kPa (42)) of a block of tectorial membrane overlying the hair bundle. The bundle coherence persisted when the flexural rigidity was reduced and the correlation coefficient of motion of two edges of the bundle fell below 0.5 only when the flexural rigidity of the bar was less than 1 × 10−23 N·m2, which is much smaller than the value used. The constraint is artificial in that it is rigid but massless, whereas in practice the bundles will be loaded by a block of tectorial membrane having significant mass. The effects of tectorial membrane mass will be considered later.

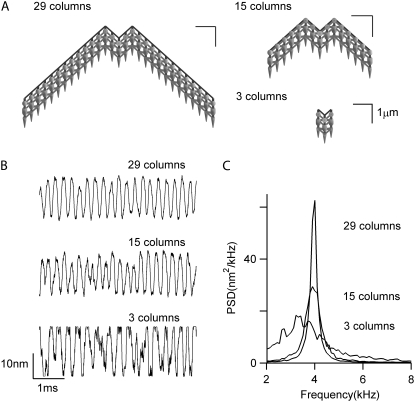

FIGURE 2.

Effect of bundle attachment to the overlying structure. (A) Spontaneous movement of the bundle when the tip of the bundle is constrained by the crossing bar. (B) Spontaneous movement of the bundle when it is freestanding without tip constraint. In A and B, the top three plots show the bundle tip displacement of a resting hair cell bundle: average bundle tip displacement (Xmean), and displacement of the right tip (Xright) and left tip (Xleft) of each bundle. Below is the PSD plot showing that the oscillations peaked at 4.0 kHz (A) and 3.8 kHz (B). The constrained bundle oscillated with a higher Q factor (Q = 15) than that for the nonconstrained (Q = 2.7).

Surprisingly, the oscillation frequency was also not grossly affected by altering the stereociliary number from a central block of 3 columns to a full complement of 29 columns (Fig. 3). With bundle enlargement, there was a small upward shift in FO, but the major effect was an increase in the Q of the power spectral density (PSD). The Q values were 1.8, 5.7, and 15 for bundles with 3, 15, and 29 columns, respectively. The invariance of FO with bundle size may be partly explained by the fact that the mechanical parameters—mass and stiffness—scale in proportion to the number of columns. One consequence of the parameter values required to generate bundle oscillations, in particular those for the gating swing (b = 3 nm) and the stiffness of the tip link complex (kGS = 8 mN·m−1), was a large single-channel gating force, z (z = γkGSb) of 2.6 pN, where γ is the geometric gain (0.11), and a narrow operating range for the channel of only ∼25 nm. When the two critical parameters were reduced, oscillations at a similar frequency persisted with b = 2.5 nm and kGS = 6 mN·m−1, yielding a single-channel gating force of 1.7 pN. Oscillations could not be obtained with further reduction in these parameters. To match the experimental results of rat OHC bundle stiffness in controls and after treatment with agents that block the MT channels or sever the tip links (18), kGS could not be reduced below 4 mN·m−1, which provided a constraint on the parameter values. A necessary condition for oscillations is the presence of a region of negative stiffness in the force-displacement relationship. According to the gating theory (30), hair bundle stiffness (kHB) is given by:

|

(12) |

where N is the number of MT channels, p is their probability of opening, and kS is the passive bundle stiffness, which includes the rootlets and interciliary connections. The condition for hair bundle negative stiffness is

|

(13) |

where a = kS/kGS. For the low-frequency OHC bundle, a = 1.9/8 = 0.24, N = 58, and p = 0.5, so the gating energy kGSb2 must be larger than 21 zJ. In this model, the minimum value for the gating energy kGSb2 required to cause the bundle to oscillate spontaneously, with kGS = 6 pN/nm and b = 2.5 nm, was 38 zJ. The force-displacement relationship of the active hair bundle exhibited a negative stiffness over the region of channel gating (not shown), and at the extremes of the relationship, the passive hair bundle stiffness with the channel fully closed or open was 6 mN·m−1, similar to that found experimentally (18).

FIGURE 3.

Effects of bundle size. Three hair cell bundles with different sizes, each with three ranks but different numbers of columns, were simulated. (A) Top view of three bundles. (B) Bundle tip displacements without external stimulus. (C) PSD plots for the three bundle sizes. As the number of stereocilia increased, the bundle movement became less noisy and the power spectrum became narrower. Q factors are 1.8, 5.7, and 15 for the bundle with 3, 15, and 29 columns, respectively.

MT channel number and arrangement

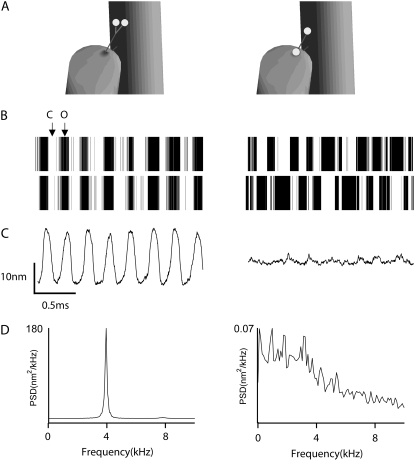

For each of the manipulations considered so far, a single MT channel was sited at the upper end of each tip link, but there is some evidence for the presence of two MT channels per tip link in both nonmammals (34) and mammals (20). The imaging of Ca2+ entry through the MT channels using fluorescent dyes has shown fluorescence increases in both the shortest and tallest ranks of stereocilia, which has been taken to indicate MT channels at both ends of tip links (34). We therefore considered two possible channel arrangements: both channels at the upper end of the tip link compared to one channel at the upper end of the tip link and the other channel at the lower end. The two arrangements are functionally different because in the former case the channels are in parallel and will therefore open and close in synchrony, whereas in the latter case they are in series and their gating will be out of phase (Fig. 4). Only the parallel arrangement (both channels at the upper end of the tip link) produced oscillations, with FO remaining at 4 kHz but Q increasing to 30, twice that for the single-channel case. It might be argued that the difference in behavior between the parallel and series channel configurations stems solely from a difference in the total gating stiffness. For the case where the channels are at either end of the tip link, the effective gating stiffness is half the value of the individual ones: kGS,tot = 4 mN·m−1. However, no oscillations were present for the series case even when the gating stiffness for each channel was doubled, making the effective stiffness equal to 8 mN·m−1, identical to that of a single channel. Similarly for both channels at one end of the tip link, the effective gating stiffness is twice that of the of the individual values (kGS,tot = 16 mN·m−1), but oscillations persisted when the gating stiffness for each channel was halved. The oscillations stem from the cooperative interaction between the two channels, a property previously examined as a means of generating negative stiffness (43). To examine other properties of the oscillations, only one channel per tip link was used in the simulations.

FIGURE 4.

Effects of arrangement of two MT channels on spontaneous oscillations. (A) Two channels were arranged in parallel, both at the upper end of the tip link (left); two channels in series, one channel attached at the upper end and the other channel at the lower end of the tip link (right). (B) The barcode-like plots show the states of two channels: solid bars denote the time when the channel was open, and blanks indicate the closed channel. When the two channels were in parallel they opened and closed in phase (left), but when they were serially connected (right) the two channels opened and closed alternatively or in opposite phase. (C) Two-millisecond stretches of bundle motion showing spontaneous oscillation when the MT channels were arranged in parallel (left) but absence of oscillations when connected in series. Bundle tip displacement and channel open probability differ dramatically according to the channel arrangement. (D) PSD plots indicating sharply tuned oscillations for parallel channel connection (left, peak value 180 nm2·kHz−1) but low-pass filter with series connection (right, peak value 0.07 nm2·kHz−1). The bundle oscillation was not seen when the channels were arranged in series. The Q factor of the two-channel parallel case is 30, which is twice that of the single-channel case, but the frequency remained the same at 4 kHz.

Entrainment and amplification

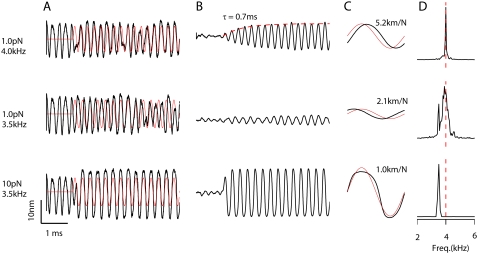

The spontaneous oscillations could be entrained by extrinsic sinusoidal stimulation of the bundle, the system being most sensitive for stimuli at the oscillation frequency, FO (Fig. 5). To dissect out the response from spontaneous activity not locked to the stimulus, multiple (80–160) simulations were averaged. For stimulation at FO, the amplitude of the averaged response grew with a time constant of 0.7 ms (Fig. 5 B). Such behavior is typical of a narrow-band filter stimulated at its resonant frequency and has been seen in the receptor potentials of turtle auditory hair cells (44). For a resonance, the time constant, τR, of the response buildup is related to the Q of the filter, (Q ≈ π FOτR); thus the larger the Q, the slower the time constant. The estimated Q based on the value for τR of 0.7 ms is 9. When the bundle was stimulated with the same force amplitude of 1 pN at 3.5 kHz, slightly lower than FO, bundle motion was poorly entrained to the stimulus, and the PSD function contained the frequencies of both the stimulus and the spontaneous activity. However, when the force was increased, making it sufficient to suppress the spontaneous oscillations, the bundle movement was entrained to the external stimulus and the PSD function was dominated by the stimulation frequency.

FIGURE 5.

Entrainment of spontaneous oscillation by an external stimulus. (A) Sinusoidal forces were applied to a spontaneously oscillating hair cell bundle for three different stimulation conditions: one at the frequency of the spontaneous oscillations (FO = 4 kHz) and two for slightly lower frequency (3.5 kHz). Thick lines are bundle tip displacements and thin red lines are external stimuli. Initial states of the bundle for the three simulations were the same and selected to have the opposite phase to the stimulus. (B) Bundle displacement in response to the three different stimuli in (A) averaged over 160 presentations (top two records) and 80 presentations (bottom record). Note that the response at FO (4 kHz, top) builds up with a time constant of 0.7 ms, indicative of a sharply tuned resonator. The bundle entrained poorly to the 3.5 kHz stimulus at low level (middle), but at the higher level the force was sufficient to suppress the spontaneous movement and the bundle movement was entrained to the external stimulus. (C) A single cycle of bundle displacement (red line) averaged over 200 ms of response compared to the force stimulus (black line), which was scaled for comparison with displacements. The bundle compliance obtained by dividing the displacement amplitude by the force amplitude is given beside each trace. (D) PSD plots for each response showing a sharply tuned response at FO (top). At 3.5 kHz, the spectral density contains frequency components (both the spontaneous oscillation and the stimulus; middle). For the larger stimulus level at 3.5 kHz, the spectral density is now dominated by the stimulus frequency.

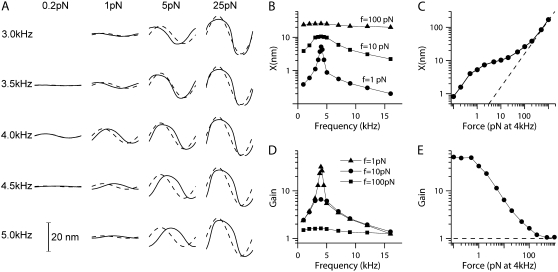

Entrainment to an external stimulus can be used to demonstrate both the amplification and nonlinearity of the process underlying hair bundle oscillations (Fig. 6). For a range of frequencies and amplitudes of the external force stimulus, the bundle displacement response was deduced by averaging cycle by cycle over 200 ms of response. The ratio of the amplitudes of the average displacement to the sinusoidal force stimulus provides a measure of the compliance for the specific stimulation conditions. Sharp tuning of the response was visible at the lowest stimulation level of 1 pN, but the tuning broadened with larger stimuli (Fig. 6 B). The compressive nonlinearity is evident in the displacement-force plot for stimuli at FO (Fig. 6 C). The form of the nonlinearity closely resembles that observed in measurements of basilar membrane vibrations as a function of sound pressure (45,46). The nonlinearity is also evident when the results of the simulations are expressed in terms of the gain. Here the gain is defined as the compliance for the active bundle movement (see above) divided by the passive compliance with the channels blocked. The gain was greatest at the frequency of the bundle oscillations (FO = 4 kHz) and decreased as the stimulus level increased (Fig. 6 D). For stimulation at FO the gain decreased from a maximum of ∼50 and approached its passive limit of unity for stimuli above 200 pN (Fig. 6 E).

FIGURE 6.

Compressive nonlinearity demonstrated by entrainment to an external stimulus. The hair cell bundle was stimulated with sinusoidal forces with different frequencies (1–16 kHz) and magnitudes (0.1–1000 pN). (A) Representative examples of average bundle tip displacements (solid lines) and force stimuli (broken lines) scaled for comparison with displacements for one stimulus cycle. Displacements were averaged cycle by cycle over 200 ms of response. (B) Bundle displacement plotted against stimulation frequency for three different force magnitudes. Note the sharp tuning for small 1 pN stimuli and the broad tuning for the largest 100 pN stimuli. (C) Bundle displacement plotted against force magnitude at the frequency of the spontaneous oscillations, FO = 4 kHz. Note that the relationship displays a compressive nonlinearity for intermediate stimulus levels, is linear at low stimulus levels, and again approaches linearity (denoted by dashed line) at the highest levels. (D) Gain plotted against stimulation frequency for three different force magnitudes. Gain is defined as the ratio of the compliance under the stimulus conditions to the passive compliance with the MT channel blocked. (E) Gain plotted against force magnitude at the frequency of the spontaneous oscillations, FO = 4 kHz. The gain declines from a maximum of 50 at the lowest levels, approaching 1 (passive) at the highest levels.

Determinants of the oscillation frequency

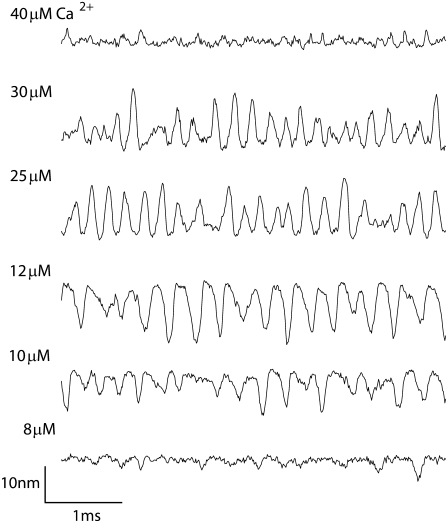

The principal determinants of the oscillation frequency for freestanding bundles were the channel kinetic parameters, especially those pertaining to the binding and action of Ca2+. Changing the Ca2+ concentration alone, however, was insufficient to produce large shifts in FO (Fig. 7). When the intracellular Ca2+ at the fast adaptation site, CFA, was varied fivefold, bundle oscillations were obvious in only a restricted Ca2+ range between 12 and 30 μM; in this range the oscillation frequency increased slightly from 3 kHz to 4.5 kHz. The oscillations were most sharply tuned to 4 kHz with a CFA of 20 μM, which was the condition used in the other simulations. At extreme Ca2+ concentrations, the oscillations degenerated into a series of brief flicks or twitches from the resting position, which were especially prominent at 10 μM Ca2+. Such twitches have been observed in frog saccular hair cells (47).

FIGURE 7.

Effects of Ca2+ on the spontaneous oscillation. Different levels of the calcium concentration at the fast adaptation site were simulated. The bundle oscillated when the Ca2+ concentration at the fast adaptation site was between 12 and 30 μM. Other parameters were identical to those given in Table 1. The hair bundle oscillated most strongly at 4 kHz with Ca2+ of 20 μM. The oscillation frequency increased from 3 kHz to 4.5 kHz as the Ca2+ concentration increased from 12 to 30 μM. Note the “twitch-like” behavior at low Ca2+.

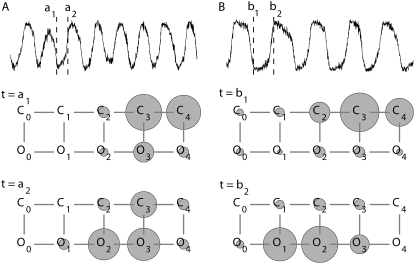

Three main parameters significantly affected FO:fCa, the change in force to open the channel on binding Ca2+,  the dissociation constant for the Ca2+ binding site and

the dissociation constant for the Ca2+ binding site and  the Ca2+ binding rate. The effects of changing fCa alone are shown in Fig. 8. When fCa was reduced from 3.5 pN to 1.5 pN, keeping all other parameters the same, the frequency of spontaneous oscillations was reduced from 4.0 kHz to 2.4 kHz. An explanation for this difference can be found by examining the distribution of channel states during the oscillation cycle. This was done by comparing the proportion of channels in each state when the open probability was near a maximum at the peak of the oscillation cycle and near a minimum at the dip. At the higher oscillation frequency with fCa = 3.5 pN, the state diagram cycled approximately between the states C4 and O2 (Fig. 8 A). When fCa was reduced to 1.5 pN, the state diagram cycled approximately between states C4 and O1, thus taking longer to complete the cycle and hence lowering the oscillation frequency (Fig. 8 B). The oscillation frequency could also be changed by altering

the Ca2+ binding rate. The effects of changing fCa alone are shown in Fig. 8. When fCa was reduced from 3.5 pN to 1.5 pN, keeping all other parameters the same, the frequency of spontaneous oscillations was reduced from 4.0 kHz to 2.4 kHz. An explanation for this difference can be found by examining the distribution of channel states during the oscillation cycle. This was done by comparing the proportion of channels in each state when the open probability was near a maximum at the peak of the oscillation cycle and near a minimum at the dip. At the higher oscillation frequency with fCa = 3.5 pN, the state diagram cycled approximately between the states C4 and O2 (Fig. 8 A). When fCa was reduced to 1.5 pN, the state diagram cycled approximately between states C4 and O1, thus taking longer to complete the cycle and hence lowering the oscillation frequency (Fig. 8 B). The oscillation frequency could also be changed by altering  the Ca2+ binding rate, while keeping

the Ca2+ binding rate, while keeping  the dissociation constant for the calcium-binding site, fixed. Reducing

the dissociation constant for the calcium-binding site, fixed. Reducing  fivefold to 0.2 ms−1μM−1 lowered the oscillation frequency from 4 to 1.1 kHz. Finally, the oscillation frequency could be changed by altering

fivefold to 0.2 ms−1μM−1 lowered the oscillation frequency from 4 to 1.1 kHz. Finally, the oscillation frequency could be changed by altering  the dissociation constant for the calcium binding site. However, here it was necessary also to adjust the range of Ca2+ concentrations at the adaptation site to optimize the sharpness of tuning as in Fig. 7.

the dissociation constant for the calcium binding site. However, here it was necessary also to adjust the range of Ca2+ concentrations at the adaptation site to optimize the sharpness of tuning as in Fig. 7.

FIGURE 8.

Determinant of frequency: a shift in fCa, the change in force to open the channel on binding Ca2+, changes the oscillation. (A) A 2-ms section of bundle tip displacement showing spontaneous oscillations at 4.0 kHz; fCa = 3.5 pN. Below is the channel state diagram when open probability was near a minimum (t = a1) and maximum (t = a2). C and O indicate the closed and open channel configurations, respectively, with the subscripts denoting the number of Ca2+ ions bound to the channel. The areas of the solid circles represent the proportion of the channels that stays in each channel state at that point in time. (B) A 2-ms simulation showing spontaneous oscillations at 2.4 kHz. fCa = 1.5 pN; all other parameters as in Table 1. Below is the channel state diagram when the open probability was near minimum (t = b1) and maximum (t = b2). Note that the state diagram cycled approximately between states C4 and O2 in A, but between states C4 and O1 in B. This explains why the cycle time was longer in B.

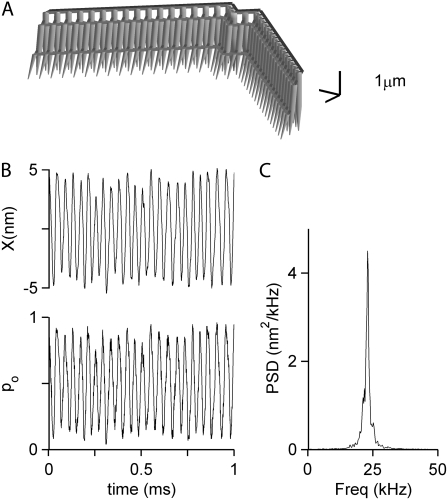

To extend the results on the factors determining the oscillation frequency, a new hair bundle FE model was created to reflect the bundle shape of a high-frequency hair cell, which increased the number of stereocilia and decreasing their height in accordance with hair bundle morphology in the basal turn of the rat cochlea (see Materials and Methods). The change in morphology on its own was insufficient to increase FO, and so fCa and  were also increased. In addition, it was necessary to alter one other channel property, the intrinsic force difference between the open and closed states, to maintain the same resting-open probability. With changes in these channel parameters, the oscillation frequency was increased over fivefold to 23 kHz, identical to the characteristic frequency of the second location in the rat cochlea (Fig. 9). The oscillation frequency is proportional to the change in

were also increased. In addition, it was necessary to alter one other channel property, the intrinsic force difference between the open and closed states, to maintain the same resting-open probability. With changes in these channel parameters, the oscillation frequency was increased over fivefold to 23 kHz, identical to the characteristic frequency of the second location in the rat cochlea (Fig. 9). The oscillation frequency is proportional to the change in  and thus an additional fivefold elevations in

and thus an additional fivefold elevations in  and in the Ca2+ concentration at the fast adaptation site to 500 μM can in theory increase the oscillation frequency to 100 kHz provided the passive mechanics of the hair bundles do not become limiting.

and in the Ca2+ concentration at the fast adaptation site to 500 μM can in theory increase the oscillation frequency to 100 kHz provided the passive mechanics of the hair bundles do not become limiting.

FIGURE 9.

Determinant of frequency: KD, Ca2+ dissociation constant. (A) The hair bundle morphology of a rat high-frequency hair cell was used to create a new FE model. The hair bundle had more stereocilia of smaller maximum height, (2.4 μm compared to 4.2 μm) than the low-frequency bundle. (B) Spontaneous oscillations of bundle position and open probability. (C) PSD plots indicating sharply tuned oscillations at 23 kHz. For these simulations, KD and CFA, the Ca2+ concentration near the open channel, were elevated five times. Other values as in Table 1 except: fCa = 8 pN and f0, the intrinsic force difference between open and closed states = −15 pN.

It should be noted that the change in bundle morphology, although realistic for the appropriate characteristic frequency, was not required to increase the oscillation frequency. If the low-frequency (4 kHz) bundle geometry was combined with the high-frequency channel parameters, the bundle still oscillated at high frequency (23 kHz). The fact that the passive bundle properties did not limit performance is surprising given that there were several differences between the two hair bundle types: the high-frequency bundle had more stereocilia, was approximately half as high (2.4 μm compared to 4.2 μm), and had twice the geometric gain of the low-frequency bundle (0.25 compared to 0.11).

The effects of tectorial membrane loading

The simulations so far have dealt exclusively with freestanding hair bundles without inertial loading, similar to those used in vitro preparations. In contrast, the bundles of mammalian cochlear OHCs in situ are tightly attached to an overlying tectorial membrane. Although the contribution of the tectorial membrane stiffness to the organ of Corti mechanics is still controversial, recent observations (48) have been used to support the previous theoretical proposal for a radial resonance of the tectorial membrane (49,50). We investigated whether the inertia of the tectorial membrane can affect the mechanics of the hair bundle-tectorial membrane complex. This was implemented by loading the hair bundle with an effective mass calculated as described in Materials and Methods. In the first instance, we simulated the passive behavior of the system with the MT channels blocked, and a series of sinusoidal forces with the amplitude of 100 pN and different frequencies were applied to the tips of the bundle. When the tectorial membrane mass was neglected, the bundle behaved as an overdamped system and the roll-off (half-power) frequency was dominated by the damping of the bundle (Fig. 10 A). The roll-off frequencies of the two bundles tested (low-frequency and high-frequency) were 23 kHz and 88 kHz, much higher than the characteristic acoustic frequencies of the OHCs: 4 kHz and 23 kHz, respectively. These values agree with the first-order approximation. Under circumstances where viscous forces dominate the mechanics, the passive bundle behaves as a low-pass filter with a half-power frequency given by kHB /2πr, where r is viscous damping. When the low-frequency bundle was loaded with a tectorial membrane mass, the passive bundle resonated to the external stimulus (Fig. 10 B) at a frequency of 5.1 kHz. This is consistent with the second-order approximation in which the resonant frequency of the hair bundle/tectorial membrane (FHB-TM) mechanical complex is determined by the hair bundle stiffness, kHB, and the tectorial membrane mass, m, according to:

|

(14) |

When the active contribution of the MT channel was incorporated, the bundle displayed spontaneous oscillations in the absence of an external stimulus. With the addition of the tectorial membrane mass, two differences emerged (Fig. 10 C). First, the spontaneous oscillations became more narrow-band and the Q of the PSD function increased to 40 compared to 15 without the tectorial membrane mass. Second, the spontaneously oscillating frequency (2.9 kHz) was lower than that for either the active bundle without tectorial membrane mass (4 kHz) or the passive bundle with tectorial membrane mass (5.1 kHz). The lower oscillations frequency probably arises because the effective bundle stiffness in the active case is lower than that with the passive case. When active, the bundle stiffness varies depending on the bundle deformation. At zero displacement the bundle has negative stiffness (−0.8 mN/m) and as it deforms further either in the negative or positive directions, the bundle stiffness approaches the passive stiffness (6 mN/m). The relevance of the tectorial membrane mass to the spontaneous oscillation frequency was confirmed by altering the mass. As the mass was decreased, the oscillation frequency increased and asymptotically approached to 4 kHz, the oscillation frequency for the freestanding bundle.

FIGURE 10.

Effects of loading the hair bundle with a tectorial membrane mass. (A) Passive resonance of a low-frequency (solid circles) and a high-frequency (open circles) hair bundle in the absence of the tectorial membrane mass with MT channels blocked. The system behaves as a low-pass filter with corner frequency of 23 kHz (solid circles) and 88 kHz (open circles). The hair bundle was driven with a sinusoidal force stimulus of 100 pN amplitude at different frequencies. (B) Passive behavior of the same two hair bundles surmounted by a block of tectorial membrane. The block of tectorial membrane had a mass of 6.2 × 10−12 kg for the low-frequency location, which was decreased fourfold for the high-frequency location. The MT channels were blocked, so the system was not spontaneously active. Resonant frequencies: 5.1 kHz (solid circles) and 21 kHz (open circles). (C). The active hair bundles, incorporating MT channel gating, combined with the tectorial membrane mass generated narrow-band spontaneous oscillations. PSD function is plotted against frequency, giving FO = 2.9 kHz, Q = 40 for the low-frequency location, and FO = 14 kHz, Q =110 for the high-frequency location.

To simulate the high-frequency system, the tectorial membrane mass was decreased fourfold based on histological observation in the adult rat cochlea (26). At the same time, the passive hair bundle stiffness increased about fourfold from 6 mN/m at 4 kHz location to 25 mN/m at high-frequency location. In the absence of the channel, the passive resonant frequency (FHB-TM) of the hair bundle/tectorial membrane increased from 5.1 to 21 kHz as expected according to Eq. 14 (Fig. 10 B). Simulations using the high-frequency hair bundle structure that incorporated channel gating now produced spontaneous bundle oscillations at 14 kHz with a very large Q of 110 (Fig. 10 C). These results show that the dependence of the oscillation frequency on model parameters is complex and depends on both the hair bundle/tectorial membrane mechanics (the feed-forward pathway) and the MT channel kinetics (the feed-back pathway). The oscillation frequency is limited by whichever of the two is slower.

DISCUSSION

The mechanical filter and the channel filter

The basic feature of the hair cell transduction model consists of two components in feedback configuration (Fig. 1 C): the passive hair bundle mechanics and the MT channel in the feedback loop. Hair bundle motion activates the MT channels, and channel gating modifies hair bundle mechanics via the tip links. In our simulations of freestanding hair bundles, the properties of the MT channels in the feedback loop largely determine both the frequency of oscillations (due to the kinetics of Ca2+ binding and action; Figs. 8 and 9) and their sharpness of tuning (by channel number and location; Fig. 4), oscillation frequencies of at least 23 kHz being produced. Different bundle sizes affected the sharpness of tuning but had no significant effect on the resonant frequency. This contrasts with the conclusions of Choe et al. (16), who also simulated high-frequency resonance of freestanding hair bundles using an MT channel scheme. They obtained resonant frequencies up to 20 kHz, but argued for a central role of the number and height of the stereocilia in dictating frequency. A possible explanation for the difference is that in the model presented here, the mechanics of freestanding bundles have a wider frequency range than the MT channels in the feedback loop and hence do not limit the performance of the system.

In theory, the hair bundle can behave as a mechanical resonator with resonant frequency set by the stiffness of the bundle and the mass it carries. If the bundle is freestanding and the mass is contributed only by the bundle itself, the passive resonant frequency will be very high and the response is likely to be overdamped (4,28). Under these circumstances, viscous forces dominate the passive bundle mechanics and the bundle behaves as a low-pass filter with half-power (roll off) frequency of 23 kHz, well above the 4 kHz spontaneous oscillations. Thus, passive bundle mechanics will not attenuate frequencies around those of the spontaneous oscillations. This line of argument applies only if the hair bundle is freestanding. In both avian and mammalian cochleas, the bundles are attached to an overlying tectorial membrane, which will contribute mass. If inertial force dominates over viscous force, the hair bundle/tectorial membrane mechanical complex itself becomes resonant. Clearly, the system would function most efficiently if the resonant frequency of the bundle/tectorial membrane complex, the transfer function in the forward direction, were matched to the performance of MT channel gating in the feedback loop. Our simulations (Fig. 10) suggest that this could be the case. However, it is also conceivable that the MT channel (the channel filter) has much faster kinetics than the hair bundles/tectorial membrane complex (the mechanical filter). In this case, the frequency performance of the system is determined solely by the mechanical components in the feed-forward pathway.

The model presented here shares several features with that of Choe et al. (16), who also proposed an explanation for high-frequency amplification by the hair bundle. First, both models utilize fast adaptation due to the channel reclosure as a driving mechanism for the amplification, unlike other analyses (7,51) that adopt myosin-driven adaptation as part of the hair bundle's oscillatory mechanism. Second, to optimize the effects of fast adaptation, both models assume multiple Ca2+ binding sites on the MT channel. However, the studies differ in their representation of the hair bundles. As in most other analytical studies of the hair bundle, Choe et al. (16) used a simple mechanical model (30) that represents the complex bundle shape by two linear springs and a damper. They concluded that the oscillation frequency depends on the bundle morphology, after lumping the bundle variations (including total stiffness due to the rootlets and horizontal connectors, geometrical gain, and bundle height) into a single parameter: the stereociliary number. In contrast, the hair bundle structure is explicitly defined in our treatment. This allowed us to simulate two hair bundles from high- and low-frequency regions, but we found little effect of the differences in bundle structure itself on the oscillation frequency. Another theory regarding hair bundle oscillations (52), again employing a simple mechanical model, also infers a dependence of oscillation frequency on bundle structure. However, this theory relies on a motor role for the kinocilium, which is absent in mature mammalian OHCs.

The role of the tectorial membrane

Experimental measurements of hair bundle mechanics are usually performed in isolated preparations in which the tectorial membrane has been removed. However, in vivo the bundles are loaded with the tectorial membrane, which is crucial for stimulus delivery and will modify the mechanical performance of the hair bundles. The traditional view of the role of the tectorial membrane is that it behaves as a solid plate, extending about its attachment at the spiral limbus and acting as mass loading for the hair bundles (53,54). We used this simple notion in analyzing its contribution, its mass combined with the hair bundle stiffness acting as a second-order resonance. In the active system, with the MT channel-hair bundle interaction included, the tectorial membrane may affect frequency selectivity in two ways. First, the tectorial membrane may behave as a constraint that enables coherent motion of all the stereocilia. Unlike the bullfrog saccular hair bundle (40), freestanding isolated OHC bundles did not deform coherently. As the bundle was constrained, the quality factor Q of the oscillations increased from 2.7 to 15 (Fig. 2). This implies that even if there were spontaneous oscillations of the OHC bundle in vivo, these might be difficult to observe after removal of the tectorial membrane. It also suggests that spontaneous oscillations of inner hair cell bundles, which are not firmly constrained by the tectorial membrane, may be poor or absent. Second, the hair bundle-tectorial membrane complex can behave as a passive resonator. Our results predict that this passive resonance enhances the frequency selectivity still further over that in the absence of the tectorial membrane (Fig. 10). Some experimental support is available for the existence of a secondary resonance in the vibration pattern of the tectorial membrane (55), though this conclusion has been disputed (56). It should be noted that there is a substantial (∼30-fold) reduction in tectorial membrane mass along the cochlea (57,26,58), which along with an increase in OHC bundle stiffness (∼100-fold, attributable to a decrease in (hair bundle height)2 and an increase in number of stereocilia (59)) will increase the passive resonant frequency 50-fold.

We have ignored the overall radial stiffness of the tectorial membrane, which is justifiable provided it is much lower than the OHC bundle stiffness. There are two main components to the radial stiffness of a slice of tectorial membrane: the stiffness of the middle zone overlying the hair bundles, and the stiffness of the attachment site on the spiral limbus (Fig. 1) (60). The stiffness of the middle zone is assumed to be greater than that of the hair bundles based on measurements in isolated pieces of tectorial membrane (61–63). If the stiffness of the limbal attachment is small, it will dominate the radial motion. Evidence on this is controversial but it can only be assayed by in situ measurements. There are two in situ measurements of the radial stiffness of the tectorial membrane. Zwislocki and Cefaratti (53) concluded that the tectorial membrane radial stiffness is an order of magnitude smaller than the bundle stiffness. Richter et al. (64) reported that the tectorial membrane radial stiffness is about the same order as the hair bundle. However, in making the comparison, they did not directly measure hair bundle stiffness; instead they used bundle stiffness values obtained for large, visually-detected motion in a guinea pig cochlea preparation for which there was no evidence of transduction (65). More recent measurements for small deflections of OHC bundles during simultaneous recording of MT currents yielded values for bundle stiffness that were seven times larger (18,66), suggesting that the bundle stiffness dominates the stiffness of the bundle/tectorial membrane complex. If the effective radial stiffness of the tectorial membrane is much greater than the OHC bundle stiffness, the bundles are deformed as if they were displacement-clamped. In such a situation, spontaneous oscillations of the OHC bundle are suppressed and frequency selectivity attributable to channel kinetics disappears.

Applicability to the mammalian cochlea

Although spontaneous oscillations of hair bundles have been reported for both turtles (4) and frogs (7), no equivalent data are available for mammalian cochlear hair bundles. This experimental lacuna is at least partly attributable to the greater technical difficulty of obtaining mechanical measurements in isolated preparations of hair cells with much higher characteristic frequencies and faster MT channel kinetics. In addition, mammalian hair bundles in isolated cochleas in which the tectorial membrane has been removed may show less coherence of motion between the stereocilia (Fig. 2), which would lower the Q of the spontaneous oscillations. Nevertheless, our simulations demonstrate the feasibility of high-frequency bundle oscillations and provide motivation for further experimental investigation in mammals. However, there are some caveats to our results. First, it was necessary to assume large values for the gating swing and the stiffness of the tip link complex, with the consequence that the single-channel gating force was large (>1.6 pN compared with experimental values of <1 pN (30)) and the operating range of the channel narrow (only ∼25 nm). The values of the two model parameters are not necessarily unrealistic, and the gating energy (kGSb2 > 38 zJ) is comparable to values assumed in other models of bundle oscillations (range of 24–57 zJ (7,16, 51)). However, the predicted operating range is smaller than observed experimentally for mammalian hair bundles, where it is >100 nm (66,67,18). Second, the proposed model of channel kinetics is incomplete in that it does not fully reproduce the time-dependent nonlinearity observed experimentally (18,68), due to omission of the fast release mechanism from the model (see Materials and Methods). Nevertheless, any uncertainty or incompleteness in the channel kinetics model does not invalidate our major conclusions, such as the effect of channel arrangement or the consequences of tectorial membrane loading. Third, the hair bundle alone may be unable to generate sufficient force to drive the motion of the basilar membrane. The maximum force produced by channel gating (here no more than 100 pN per OHC) is considerably smaller than the maximum force attributable to the somatic motor (69,70), underpinned by prestin (71), which is able to create forces >1 nN (72). Furthermore, the force produced by the bundle is largely radial, whereas a transverse component of force is needed to move the basilar membrane. Despite these caveats, observations of hair bundle motion in the isolated gerbil cochlea have revealed a component of cochlear amplification that, based on ionic manipulations, was attributed to active bundle motion (73).

A possible solution to this conundrum is to postulate that both active hair bundle motion and somatic contractility contribute to cochlear amplification but the hair bundle/tectorial membrane complex endows frequency selectivity with a modicum of gain, and prestin largely provides the force amplification. A second filter in the OHC force feedback is often postulated in cochlear modeling (74) even though there is no evidence that somatic prestin-based OHC motility itself is frequency selective. Further work, both experimental and theoretical, on the micromechanics of the cochlear partition will be needed to answer this question. Although our simulations have been directed at the OHCs of the mammalian cochlea, they may also apply to the short hair cells of the avian basilar papilla to provide a mechanism for achieving hair bundle frequency selectivity in cells lacking prestin-based electromotility (75).

Acknowledgments

We thank Carole Hackney for helpful comments.

This work was funded by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communicative Disorders (RO1 DC 01362 to R.F.).

APPENDIX: INTERNAL FORCES IN THE HAIR BUNDLE

Externally applied force deforms the bundle to result in a variation of the element forces. At rest, due to the work of myosin motors, the tip links are tensed and the force is equilibrated by the deformation of other structures, such as the stereocilia and horizontal connectors. As the bundle deforms, the internal forces of the hair bundle structures vary to counteract the external force. In Fig. 11 A, the internal forces in the tip links (fTL), horizontal connectors (fHC), and the reaction forces of stereociliary rootlets (mS, fS) are illustrated. To find these internal forces, a static FE analysis was implemented. To observe the mechanical response only, the MT channels were closed. Under such a passive condition, if the external force is evenly applied to the bundle tips, there is little interaction between the columns of stereocilia. Therefore, for simplicity we illustrate only one column of the bundle, which is comprised of three ranks of stereocilia. First, the internal forces of the hair bundle were computed when the bundle was at rest. Then the bundle was deformed by an externally applied force of fext = 1 pN. When the bundle was at rest, the internal forces were: fTL1 = fTL2 = 25 (giving resting tension), mS1 = 43.3, mS2 = −7.8, mS3 = −8.4, fS1x = 19.8, fS2x = −0.5, fS3x= −19.3, fS1y= 16.9, fS2y = 2.4, fS3y = −19.3, fHC1 = 1.6, and fHC2 = 3.2. The units are pN for the forces and pN·μm for the moments, with negative values indicating that the force or moment is opposite to the direction shown in the figure. Here, the tip links have angles of 52.4° (upper tip link) and 50.0° (lower tip link) with respect to the epithelial surface. When a force of 1 pN was applied at the bundle tip in the excitatory direction, the bundle tip was displaced by 4.3 nm. Fig. 11 B shows deformed (thick line) and resting (thin line) bundle configurations, the difference being exaggerated 50 times for illustrative purposes. At this deformation, the internal forces were changed to: fTL1 = 28.1, fTL2 = 28.3, mS1 = 41.1, mS2 = −8.0, mS3 = −8.7, fS1x = 26.9, fS2x = −1.6, fS3x = −25.6, fS1y = 17.6, fS2y= 2.6, fS3y = −22.7, fHC1 = 1.3, and fHC2 = 2.9. There are two notable features in the results. First, the applied external force affects the tip link tension rather than that of the horizontal connectors. At 4.3 nm bundle tip displacement the tension in the tip links was increased by 3 pN, whereas the tension of horizontal connectors was decreased by 0.3 pN. Second, the root of the tallest stereocilium is subjected to a compressive force caused by the tension in the tip link while the shortest stereocilium experiences a pulling force. This remains true as long as the tip links are tensed. There is little axial force in the middle stereocilium because it is contacted by two tip links pulling in opposite directions. With a larger excitatory stimulus (25 pN) that displaces the tallest stereocilium by 100 nm, there are substantial axial forces (fS1x, fS3x ∼200 pN) at the ankle region, suggesting that the stereocilia must be firmly anchored by the rootlets into the top of the cell (76).

FIGURE 11.

Distribution of static forces in the hair bundle. (A) Forces (f) and moments (m) acting on a single column of three stereocilia; subscript TL refers to tip links, and HC stands for horizontal connectors. (B) Changes in the bundle configuration when a positive force (fext) is applied to the tallest rank, resting bundle (thin line) and displaced bundle (thick line). The difference has been exaggerated 50 times to show the change for a force of 1 pN.

Editor: Alexander Mogilner.

References

- 1.Shotwell, S. L., R. Jacobs, and A. J. Hudspeth. 1981. Directional sensitivity of individual vertebrate hair cells to controlled deflection of their hair bundles. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 374:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pickles, J. O., S. D. Comis, and M. P. Osborne. 1984. Cross-links between stereocilia in the guinea pig organ of Corti, and their possible relation to sensory transduction. Hear. Res. 15:103–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Assad, J. A., G. M. Shepherd, and D. P. Corey. 1991. Tip-link integrity and mechanical transduction in vertebrate hair cells. Neuron. 7:985–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crawford, A. C., and R. Fettiplace. 1985. The mechanical properties of ciliary bundles of turtle cochlear hair cells. J. Physiol. 364:359–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Howard, J., and A. J. Hudspeth. 1987. Mechanical relaxation of the hair bundle mediates adaptation in mechanoelectrical transduction by the bullfrog's saccular hair cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 84:3064–3068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denk, W., and W. W. Webb. 1992. Forward and reverse transduction at the limit of sensitivity studied by correlating electrical and mechanical fluctuations in frog saccular hair cells. Hear. Res. 60:89–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin, P., D. Bozovic, Y. Choe, and A. J. Hudspeth. 2003. Spontaneous oscillation by hair bundles of the bullfrog's sacculus. J. Neurosci. 23:4533–4548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Martin, P., A. D. Mehta, and A. J. Hudspeth. 2000. Negative hair-bundle stiffness betrays a mechanism for mechanical amplification by the hair cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:12026–12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kemp, D. T. 1978. Stimulated acoustic emissions from within the human auditory system. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 64:1386–1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manley, G. A. 2001. Evidence for an active process and a cochlear amplifier in nonmammals. J. Neurophysiol. 86:541–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Dijk, P., P. M. Narins, and J. Wang. 1996. Spontaneous otoacoustic emissions in seven frog species. Hear. Res. 101:102–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kössl, M. 1994. Otoacoustic emissions from the cochlea of the ‘constant frequency’ bats, Pteronotus parnellii and Rhinolophus rouxi. Hear. Res. 72:59–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eatock, R. A. 2000. Adaptation in hair cells. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 23:285–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fettiplace, R., and A. J. Ricci. 2003. Adaptation in auditory hair cells. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 13:446–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ricci, A. J., A. C. Crawford, and R. Fettiplace. 2000. Active hair bundle motion linked to fast transducer adaptation in auditory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 20:7131–7142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Choe, Y., M. O. Magnasco, and A. J. Hudspeth. 1998. A model for amplification of hair-bundle motion by cyclical binding of Ca2+ to mechanoelectrical transduction channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 95:15321–15326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cotton, J. R., and J. W. Grant. 2000. A finite element method for mechanical response of hair cell ciliary bundles. J. Biomech. Eng. 122:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beurg, M., J.-H. Nam, A. C. Crawford, and R. Fettiplace. 2008. The actions of calcium on hair bundle mechanics in mammalian cochlear hair cells. Biophys. J. 94:2639–2653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roth, B., and V. Bruns. 1992. Postnatal development of the rat organ of Corti. II. Hair cell receptors and their supporting elements. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.). 185:571–581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beurg, M., M. G. Evans, C. M. Hackney, and R. Fettiplace. 2006. A large-conductance calcium-selective mechanotransducer channel in mammalian cochlear hair cells. J. Neurosci. 26:10992–11000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Müller, M. 1991. Frequency representation in the rat cochlea. Hear. Res. 51:247–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tsuprun, V., and P. Santi. 2002. Structure of outer hair cell stereocilia side and attachment links in the chinchilla cochlea. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 50:493–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goodyear, R. J., W. Marcotti, C. J. Kros, and G. P. Richardson. 2005. Development and properties of stereociliary link types in hair cells of the mouse cochlea. J. Comp. Neurol. 485:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gere, J. M., and S. P. Timoshenko. 1997. Mechanics of Materials. PWS Publishing, Boston, MA.

- 25.Lim, D. J. 1980. Cochlear anatomy related to cochlear micromechanics. A review. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 67:1686–1695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roth, B., and V. Bruns. 1992. Postnatal development of the rat organ of Corti. I. General morphology, basilar membrane, tectorial membrane and border cells. Anat. Embryol. (Berl.). 185:559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Freeman, D. M., and T. F. Weiss. 1988. The role of fluid inertia in mechanical stimulation of hair cells. Hear. Res. 35:201–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Denk, W., W. W. Webb, and A. J. Hudspeth. 1989. Mechanical properties of sensory hair bundles are reflected in their Brownian motion measured with a laser differential interferometer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 86:5371–5375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newmark, N. M. 1959. A method of computation for structural dynamics. ASCE J. Eng. Mech. Div. 85:67–94. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howard, J., and A. J. Hudspeth. 1988. Compliance of the hair bundle associated with gating of mechanoelectrical transduction channels in the bullfrog's saccular hair cell. Neuron. 1:189–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Crawford, A. C., M. G. Evans, and R. Fettiplace. 1989. Activation and adaptation of transducer currents in turtle hair cells. J. Physiol. 419:405–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheung, E. L., and D. P. Corey. 2006. Ca2+ changes the force sensitivity of the hair-cell transduction channel. Biophys. J. 90:124–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ricci, A. J., H. J. Kennedy, A. C. Crawford, and R. Fettiplace. 2005. The transduction channel filter in auditory hair cells. J. Neurosci. 25:7831–7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Denk, W., J. R. Holt, G. M. Shepherd, and D. P. Corey. 1995. Calcium imaging of single stereocilia in hair cells: localization of transduction channels at both ends of tip links. Neuron. 15:1311–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kennedy, H. J., M. G. Evans, A. C. Crawford, and R. Fettiplace. 2003. Fast adaptation of mechanoelectrical transducer channels in mammalian cochlear hair cells. Nat. Neurosci. 6:832–836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He, D. Z., S. Jia, and P. Dallos. 2004. Mechanoelectrical transduction of adult outer hair cells studied in a gerbil hemicochlea. Nature. 429:766–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dallos, P. 1986. Neurobiology of cochlear inner and outer hair cells: intracellular recordings. Hear. Res. 22:185–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Russell, I. J., A. R. Cody, and G. P. Richardson. 1986. The responses of inner and outer hair cells in the basal turn of the guinea-pig cochlea and in the mouse cochlea grown in vitro. Hear. Res. 22:199–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, Y. C., A. J. Ricci, and R. Fettiplace. 1999. Two components of transducer adaptation in auditory hair cells. J. Neurophysiol. 82:2171–2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kozlov, A. S., T. Risler, and A. J. Hudspeth. 2007. Coherent motion of stereocilia assures the concerted gating of hair-cell transduction channels. Nat. Neurosci. 10:87–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stauffer, E. A., and J. R. Holt. 2007. Sensory transduction and adaptation in inner and outer hair cells of the mouse auditory system. J. Neurophysiol. 98:3360–3369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghaffari, R., A. J. Aranyosi, and D. M. Freeman. 2007. Longitudinally propagating traveling waves of the mammalian tectorial membrane. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104:16510–16515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Iwasa, K. H., and G. Ehrenstein. 2002. Cooperative interaction as the physical basis of the negative stiffness in hair cell stereocilia. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 111:2208–2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crawford, A. C., and R. Fettiplace. 1980. The frequency selectivity of auditory nerve fibres and hair cells in the cochlea of the turtle. J. Physiol. 306:79–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Johnstone, B. M., R. Patuzzi, and G. K. Yates. 1986. Basilar membrane measurements and the travelling wave. Hear. Res. 22:147–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Robles, L., and M. A. Ruggero. 2001. Mechanics of the mammalian cochlea. Physiol. Rev. 81:1305–1352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Benser, M. E., R. E. Marquis, and A. J. Hudspeth. 1996. Rapid, active hair bundle movements in hair cells from the bullfrog's sacculus. J. Neurosci. 16:5629–5643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russell, I. J., P. K. Legan, V. A. Lukashkina, A. N. Lukashkin, R. J. Goodyear, and G. P. Richardson. 2005. Sharpened cochlear tuning in a mouse with a genetically modified tectorial membrane. Nat. Neurosci. 10:215–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Allen, J. B. 1980. Cochlear micromechanics—a physical model of transduction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 68:1660–1670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zwislocki, J. J. 1980. Theory of cochlear mechanics. Hear. Res. 2:171–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nadrowski, B., P. Martin, and F. Jülicher. 2004. Active hair-bundle motility harnesses noise to operate near an optimum of mechanosensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:12195–12200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Camalet, S., T. Duke, F. Jülicher, and J. Prost. 2000. Auditory sensitivity provided by self-tuned critical oscillations of hair cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 97:3183–3188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zwislocki, J. J., and L. K. Cefaratti. 1989. Tectorial membrane. II: Stiffness measurements in vivo. Hear. Res. 42:211–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nobili, R., F. Mammano, and J. F. Ashmore. 1998. How well do we understand the cochlea? Trends Neurosci. 21:159–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]